Abstract

Background:

Many smokers report attempting to quit each year, yet most relapse, in part due to exposure to smoking-related cues. It is hypothesized that extinction of the cue-drug association could be facilitated through random nicotine delivery (RND), thus making it easier for smokers to quit. The current study aimed to evaluate the effects of RND on smoking cessation-related outcomes including cigarettes per day (CPD) and exhaled carbon monoxide (CO).

Methods:

Participants were current smokers (>9 CPD) interested in quitting. Novel trans-mucosal, orally dissolving nicotine films, developed by Bionex Pharmaceuticals, were used in the study. The pharmacokinetic profile of these films was assessed in single (Experiment 1) and multiple-dose (Experiment 2) administrations prior to the smoking cessation study (Experiment 3). In Experiment 3, participants were randomized 1:1:1 to recieve 4 nicotine films per day of either: placebo delivery (0 mg), steady-state delivery (2 mg), or random nicotine delivery (RND) (0 mg or 4 mg). After two weeks, participants were advised to quit (target quit date, TQD) and were followed up 4 weeks later to collect CPD and CO and to measure dependence (Penn State Cigarette Dependence Index; PSCDI) and craving (Questionnaire of Smoking Urges; QSU-Brief). Means and frequencies were used to describe the data and repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine differences between groups.

Results:

The pharmacokinetic studies (Experiment 1 and 2) demonstrated that the films designed for this study delivered nicotine as expected, with the 4 mg film delivering a nicotine boost of approximately 12.4 ng/mL across both the single and the multiple dose administration studies. The films reduced craving for a cigarette and were well-tolerated, overall, and caused no changes in blood pressure or heart rate. Using these films in the cessation study (Experiment 3) (n = 45), there was a significant overall reduction in cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) and in exhaled CO, with no significant differences across groups (placebo, steady-state, RND). In addition, there were no group differences in dependence or craving. Adverse events included heartburn, hiccups, nausea, and to a lesser extent, vomiting and anxiety and there were no differences across groups.

Conclusion:

Overall, this pilot study found that RND via orally dissolving films was feasible and well tolerated by participants. However, RND participants did not experience a greater reduction in self-reported CPD and exhaled CO, compared with participants in the steady-state and placebo delivery groups. Future studies to evaluate optimal RND parameters with larger sample sizes are needed to fully understand the effect of RND on smoking cessation-related outcomes.

Keywords: Nicotine film, Nicotine replacement therapy, Pharmacokinetics, Nicotine delivery

1. Introduction

Tobacco use, predominantly cigarette smoking, remains the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the United States (US), accounting for more than 480,000 deaths per year (Wang et al., 2018). While many smokers report wanting and attempting to quit smoking, (Babb et al., 2017) quitting is difficult due to nicotine, the addictive constituent in tobacco that interacts through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in brain (Brunzell et al., 2015). Consequently, most attempts to quit smoking often result in relapse, even when FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) are used (Babb et al., 2017). Most relapse occurs when cravings, induced by cues or triggers associated with smoking, are experienced. These cues elicit craving because of the repeated pairing of the cue with smoking and obtaining the drug, nicotine (Ferguson and Shiffman, 2009).

NRT like the nicotine gum or the nicotine patch is designed to provide the smoker with nicotine without other toxicants to prevent intense withdrawal symptoms or cravings that tend to be associated with a relapse to smoking. One explanation for the limited success of existing NRT is that steady-state nicotine delivery (whether delivered via a patch or repeat self-administration of a shorter-acting NRT) fails to mitigate cravings provoked by environmental cues associated with smoking. These cues greatly contribute to relapse following a quit attempt, (Hogarth, 2012; Etter and Stapleton, 2006) with those who respond most strongly to smoking-related cues being the least likely to quit smoking (Ferguson and Shiffman, 2009).

Because relapse often is caused by exposure to cues, extinguishing the cue-drug association may facilitate smoking cessation and help to reduce relapse to smoking. Cue-induced craving could be reduced by dissociating the drug from the cues typically associated with its delivery. One novel method to potentially extinguish the cue-drug association is through random drug delivery, meaning that the drug is provided at random intervals and not given in relation to the typical drug-paired cues. Support for the possible usefulness of this intervention is based on both pre-clinical and clinical data (Shiffman and Ferguson, 2008; Foulds et al., 1992; Rose, 2011; Donny et al., 2006; Twining et al., 2009). For example, it has been known for some time that pre-cessation NRT treatment with steady-state nicotine via the patch can increase the odds of quitting compared to starting NRT at the quit date (Shiffman and Ferguson, 2008). Pre-cessation treatment with steady-state nicotine reduces not only the number and intensity of smoking urges, but also satisfaction from smoking (Foulds et al., 1992). The reduction in smoking, then, may relate to dissociation of the drug from cues (Rose, 2011) and/or to an increase in aversiveness associated with less predictable levels of blood nicotine. For instance, unpredictable, yoked delivery of cocaine was found to lead to greater peak “bad effects” than self-administered cocaine in cocaine-experienced human subjects (Donny et al., 2006). Similarly, rats that are administered yoked delivery of cocaine avoid the location paired with its delivery and exhibit a reduced willingness to work for the drug compared to self-administering controls (Twining et al., 2009).

Given these findings, the current iterative, 3-part experimental study aimed to test whether random nicotine delivered via an orally dissolving film could facilitate smoking cessation-related outcomes including the number cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) and exhaled carbon monoxide (CO). Experiment 1 evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of single use administrations of the 0 mg, 2 mg, and 4 mg nicotine orally dissolving films developed for this study. Experiment 2 assessed the safety and tolerability of repeat administration of these films in varying delivery regimens. Finally, experiment 3 tested the hypothesis that smoking cessation will be facilitated by random nicotine delivery (RND), rather than steady-state delivery, via the orally dissolving films.

2. Methods

2.1. Film development and management

To execute random nicotine delivery, a nicotine product in varying doses, including 0 mg, was needed. The nicotine product needed to be identical across doses and the product needed to be packaged in a way that concealed the dosage. While commercially available nicotine replacement products like the gum and the lozenge are available, these products are not available without nicotine (0 mg). Thus, we developed novel trans-mucosal, orally dissolving films in doses of 0, 2, or 4 mg of nicotine. These films were developed and manufactured by Bionex Pharmaceuticals, LLC (North Brunswick, NJ, USA), with an active pharmaceutical ingredient of 20 % nicotine polacrilex. The films were designed to dissolve on the roof of the mouth over a 5-minute period.

An Investigational New Drug application was obtained for the completion of this study since these films are not commercially available in the United States. The pharmacokinetic studies (Experiments 1 and 2) were registered on clinicaltrials.gov under NCT02239770 while the cessation study was registered under NCT03674970. In addition, this study was reviewed and approved by the Penn State College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the principles of Good Clinical Practice were followed and the principles of Good Clinical Practice were followed.

The randomization sequence for each experiment and the blinding of the films was maintained and implemented by the Penn State Investigational Drug Pharmacy. Both the researcher and participant remained blinded to the assigned treatment in all experiments.

2.2. Participants

Participants were current smokers between the ages of 18–55 who smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day. Because the study was evaluating a new nicotine delivery product, strict exclusion criteria were set to ensure participant safety. Participants were excluded from the study for the following conditions: unstable or significant medical conditions, sodium-restricted diet, heart disease, recent heart attack, irregular heartbeat, stomach ulcers, diabetes, and uncontrolled mental illness or substance abuse. Participants were also excluded from the study for the following: use of illegal drugs more than weekly in the past month, use of any non-cigarette products in the past 7 days, use of any FDA-approved smoking cessation medications in the past 7 days, or for experiencing any previous adverse reactions to using nicotine replacement therapy. In addition, females who were pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or nursing were excluded (For Experiment 1 and 2, females of child-bearing potential were excluded if not using a FDA-approved contraceptive). Finally, for the cessation study, participants had to report interest in quitting smoking in the next 30 days. These criteria were similar to that of other studies evaluating novel nicotine delivery products (Azzopardi et al., 2022).

All participants were recruited from the community using flyers and Facebook posts. For the pharmacokinetic studies (Experiments 1 and 2), participants were recruited from October 2015 to October 2017. All participants for the cessation study (Experiment 3) were recruited from March 2019 to October 2019.

2.3. Study procedures

2.3.1. Pharmacokinetic studies (Experiments 1 and 2)

These pharmacokinetic studies tested the safety and efficacy of the films manufactured for the study. Participants were screened over the phone and those potentially eligible were scheduled for a one-day visit at the Clinical Research Center of the Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey, PA. All participants were instructed not to smoke or use any nicotine-containing products for at least 16 h prior to the visit. At the visit, additional screening occurred, including collection of medical history and medication information, an assessment of drug use, and a measurement of blood pressure. To confirm no recent smoking had occurred, an exhaled carbon monoxide reading was collected using the Bedfont Pico+ Smokerlyzer. A CO reading of less than 12 parts per million (ppm) was required to remain in the study.

2.3.2. Experiment 1. Single-dose administration

Eligible participants (n = 12) were randomized using a 1:1:1 allocation generated by the study statistician to receive a single dose of the film (0, 2, or 4 mg). Prior to taking the film, an intravenous catheter was inserted into the participant’s arm to facilitate repeated blood draws. Four participants were randomly assigned to each dose (0, 2 or 4 mg). Participants were instructed to place the assigned film on their tongue, close their mouth, and gently press the film to the roof of their mouth. Blood samples were collected at baseline (prior to taking the film) and at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 120, and 180 min after the film was administered. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured at baseline, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min after the film administration. The Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU) Brief (Tiffany and Drobes, 1991) was administered at baseline, 15, 25, 55, 80, 140, and 200 min after the film administration. In addition, at the end of the study, all participants completed a modified version of Cigarette Evaluation Scale (CES), (Hatsukami et al., 2013) tailored to the nicotine film product, asking participants to rate how the nicotine films made them feel on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Extremely). Example questions included, “Was using the study product satisfying?”, “Did using the study product calm you down?”, and “Did the study product relieve the urge to smoke?” Subscales for satisfaction, aversion, relief, and psychological reward were calculated by averaging the items in each subscale.

2.3.3. Experiment 2. Multiple-dose administration

Eligible participants (n = 12) were randomized using a 1:1:1 allocation generated by the study statistician to receive multiple doses (4) of the films in the following allocations; Placebo: 0, 0, 0, 0 mg; Steady-State: 2, 2, 2, 2 mg; or Random: 4, 4, 0, 4 mg (the maximum dose to be given per day in the random condition of the cessation trial). Films were administered every 3 h. Prior to taking the first film, an intravenous catheter was inserted into the participant’s arm to facilitate repeated blood draws. Blood samples were collected at 30, 45, 60, 120, and 180 min after each of the 4 films were administered. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured at baseline, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min after each of the 4 films were administered. The QSU-Brief was administered at baseline and at 30 and 45 min after each film was administered. In addition, at the end of the study, all participants completed the CES.

2.3.4. Experiment 3. Cessation study

This study was a randomized controlled, parallel-group smoking cessation trial with a 4-week post target quit date (TQD) follow-up. Potential participants were screened for eligibility over the phone. Those potentially eligible for the study attended Visit 1 at the Clinical Research Center of the Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey PA. At this visit, further screening was conducted, including the collection of medical history and medication information, an assessment of drug use, and a measurement of blood pressure. Those eligible for the study completed study questionnaires and were instructed to smoke normally for the next week while tracking their cigarette smoking in a paper diary.

Participants returned to the study center one week later (BL1: Visit 2, Day 0) to be randomized. The study statistician generated a 1:1:1 randomization sequence and participants were allocated to the placebo, steady-state delivery, or random nicotine delivery (RND) groups. Participants were instructed to take 4 nicotine films per day, spaced 3–4 h apart, in the order provided to them (numbered packaging by day and film) while continuing to smoke cigarettes as necessary. In the placebo group, all 4 films contained 0 mg nicotine, while all 4 films per day in the steady-state group contained 2 mg nicotine. In the RND group, each film could contain 0 mg or 4 mg of nicotine and the order of the films was random each day. RND dosing was set to maintain an 8 mg/day average over 7 days. All participants were instructed to track the times each film was taken on a paper diary.

At Visit 3 (BL2: Day 14), researchers provided participants with information about the harms of smoking and the benefits of quitting (from “A Report of the Surgeon General: How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease”) and provided tips to help participants quit. The TQD set for all participants was the day following Visit 3 (Day 15). Participants were then followed up over 4-weeks at Visit 4 (Day 28, 2-Week Post-TQD) and Visit 5 (Day 42, 4-Week Post-TQD).

At each of the visits (Visit 2-Visit 5), participants reported their CPD. This data was collected daily on a paper diary and reported to researchers at each visit. CPD at each visit was calculated by taking the average of the cigarettes smoked over the past 7 days. Participants also reported the times that each film was taken and notated any films that were missed (Visit 3 to Visit 5 only). Participants were then asked to provide a CO reading and to complete questionnaires including the Penn State Cigarette Dependence Index (PSCDI), (Foulds et al., 2015) the Fagerstrom ¨ Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), (Fagerstrom and Schneider, 1989) and the QSU-Brief. Participants also completed questionnaires about their experiences with the nicotine films. One questionnaire asked participants to rate potential side effects such as dry cough, sore throat, nausea, etc. Participants ranked each of the 12 items on a scale of on a scale of No: Never (1); Yes: Rarely (2); Yes: Occasionally (3); Yes: At least once per week (4). Items were evaluated individually and overall by summing all the items in the scale (Total score range: 12–48). Participants were also asked to complete the CES. Finally, participants were asked to report any adverse events at each visit.

2.4. Blood sample processing

All blood samples were collected (approximately 5 mL from an antecubital vein) in vacutainers containing K2EDTA anticoagulant and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The plasma was pipetted off into 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes, frozen, and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. Plasma nicotine levels were quantified using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods. The lower limit of detection was 1.3 pg.

2.5. Statistical methods

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Penn State College of Medicine. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies (Harris et al., 2009). Study data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Statistica version 13 (Tibco Software, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA).

For the pharmacokinetic studies (Experiments 1 and 2), frequencies or means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for each participant characteristic by group. Mean maximal plasma nicotine concentrations (Cmax) and times to Cmax (tmax) were calculated. In addition, mean nicotine boost, or increases in plasma nicotine concentration after film administration, (Patterson et al., 2003) were calculated by subtracting the mean baseline concentration from the mean peak concentration. Mean QSU-Brief change scores by dose group were calculated by subtracting the mean baseline total score from the mean total score at each time point it was administered to illustrate craving relief over time. Mean scores for each individual item of the Study Product Evaluation Scale were calculated to describe the subjective effects experienced by each dose group. Due to low sample size in each group, no formal statistical hypothesis tests were performed between groups for outcomes for the pharmacokinetic studies (Experiment 1 and 2).

For the cessation study (Experiment 3), means and frequencies were used to describe the sample. One-way, and mixed factorial ANOVAs were utilized to test for baseline differences between groups for continuous variables. To assess interactive effects on the primary outcome measures overall, change in cigarettes per day (CPD) and change in exhaled CO from baseline to 4-weeks post-TQD were analyzed using a mixed model repeated measures ANOVA varying group (Placebo, Random, Steady) by time (BL1, BL2, 2-week post-TQD, 4-week post-TQD). Partial eta-squared () was calculated as a measure of effect size. We then used follow-up one-way repeated measures ANOVAs by group to verify that main effects from the larger model of within-group differences were exhibited by each group independently. Cohen’s D was calculated to measure effect size. The same analyses were used to evaluate the secondary outcome measures, change in dependence (FTND and PSECI). Finally, one-way ANOVAs were used to evaluate differences in side effects and subjective ratings of the nicotine films at 4-weeks post-TQD between groups.

For outcome measures collected only after randomization (Side effects and the modified CES), only those who attended a visit after being randomized were included in analysis. Some participants contributed only partial data over the 4 time points resulting in list-wise deletion when using ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation employed by repeated measures ANOVA.

3. Results

3.1. Pharmacokinetic studies (Experiments 1 and 2)

3.1.1. Experiment 1. Single-dose administration

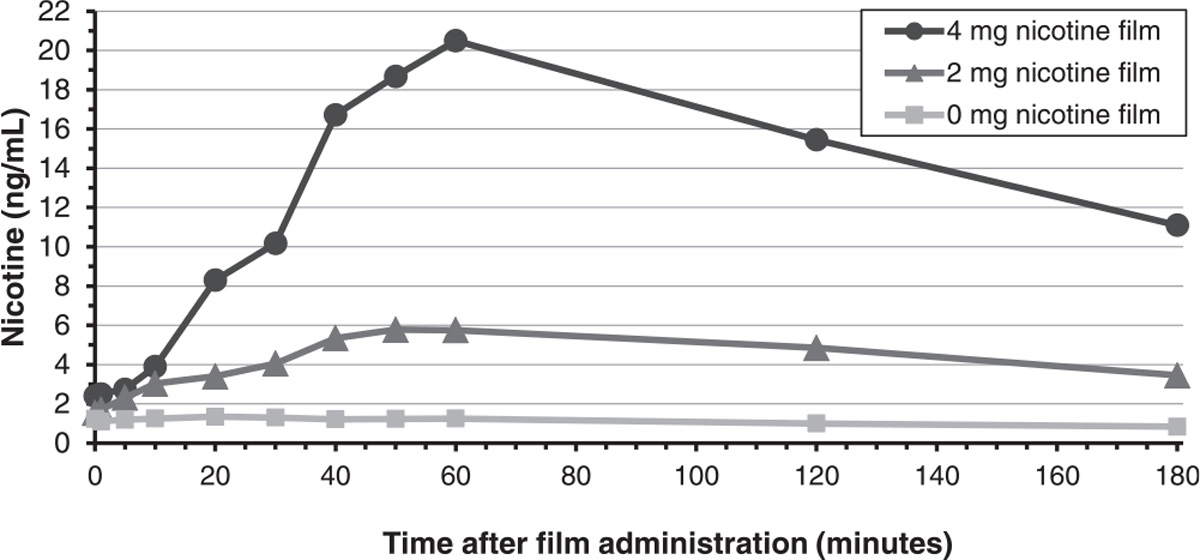

Participants (n = 12) of the single-dose administration study were 58.3 % male, 91.7 % white, and a mean age of 36.6 (SD = 11.7) years (Supplemental Table 1). The 2 mg film yielded a mean Cmax of 5.78 ng/mL (SD = 2.1) observed at 50 min post film administration (nicotine boost of 4.78 ng/mL (SD = 1.8)) while the 4 mg film yielded a mean Cmax of 20.50 ng/mL (SD = 7.1) observed at the 60 min time point (nicotine boost 18.7 ng/mL (SD = 7.7)) (Fig. 1). As expected, the placebo film did not result in any increase in plasma nicotine concentration.

Fig. 1.

Mean plasma nicotine concentrations by nicotine film dose group (Experiment 1: Single Dose Administration).

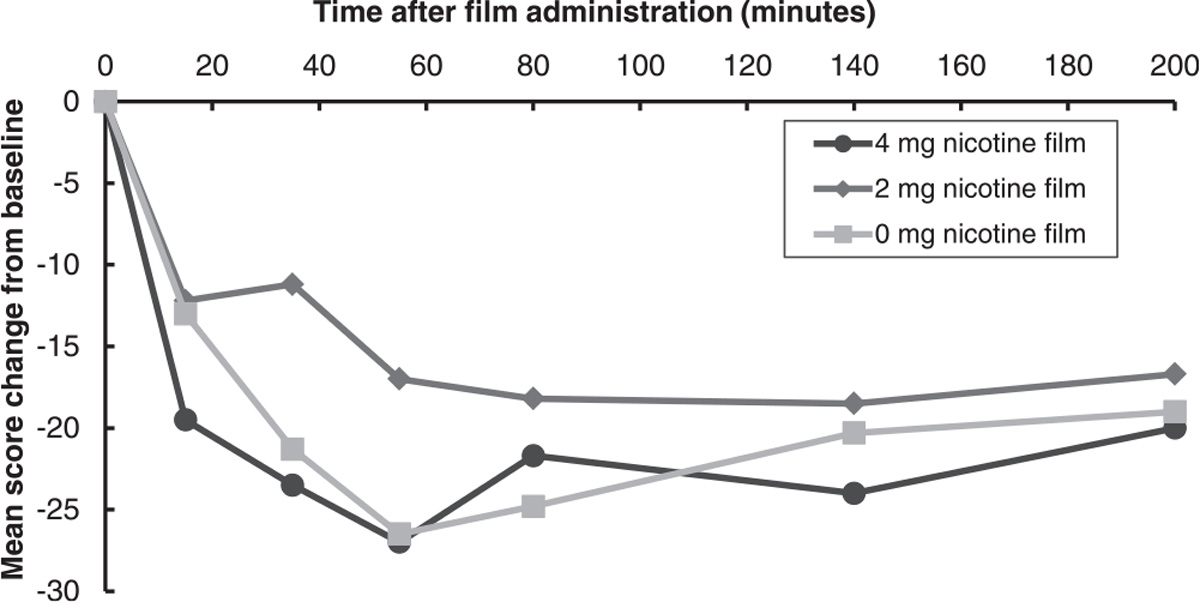

Participants across all dose groups reported craving relief on the QSU-Brief after consuming the film (Fig. 2). Participants rated the positive effects of the films moderately and there were no clear dose-response effects in the subjective ratings of the films (Supplemental Fig. 1). The placebo group preferred the taste of their film which could have influenced their other ratings (e.g., also rating highly for enough nicotine, relieving withdrawal symptoms, and being satisfying).

Fig. 2.

Mean questionnaire of smoking urges-brief change scores from baseline by nicotine film dose group (Experiment 1: Single-Dose Administration).

All three doses of the film were well tolerated and did not meaningfully alter blood pressure (Supplemental Fig. 2) or heart rate (Supplemental Fig. 3). A total of four adverse events (AEs) were reported by four subjects in the study (Supplemental Table 4). Two subjects, one in the 2 mg group and one in the 4 mg group, experienced mild hiccups lasting less than 5 min almost immediately after film administration. A subject in the 4 mg group reported moderate acute nausea, and a subject in the 0 mg group reported mild throat irritation. All documented AEs were considered to be at least possibly related to study treatment. No serious AEs occurred.

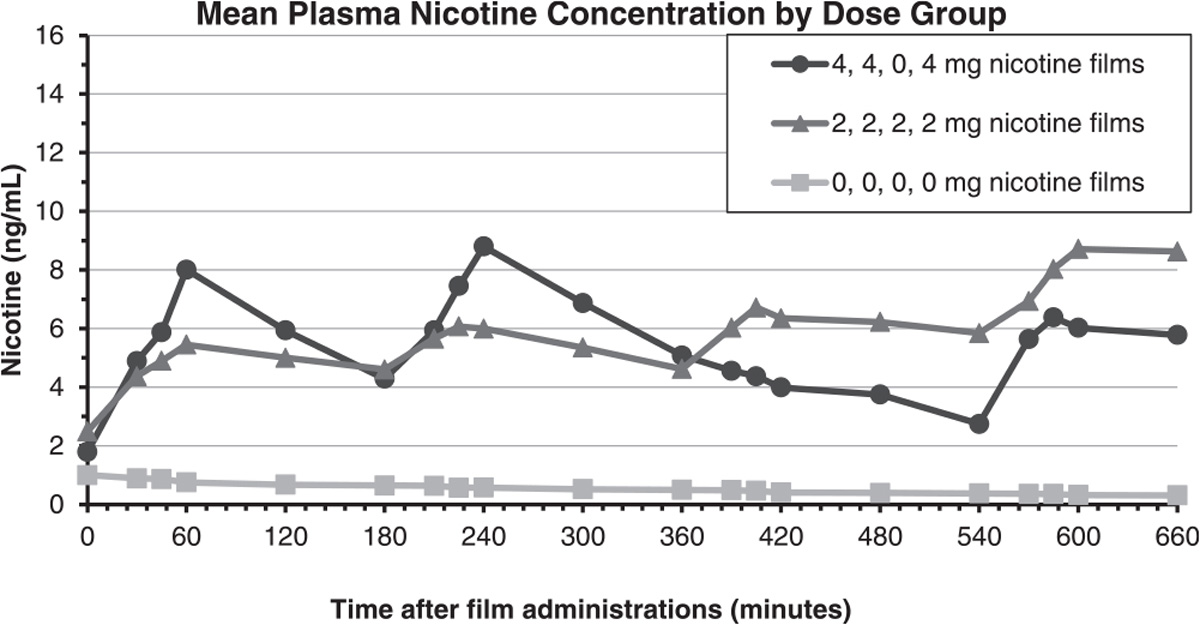

3.1.2. Experiment 2. Multiple-dose administration

Participants (n = 12) in the multiple-dose administration study were 58.3 % male, 50 % white, and a mean age of 39.2 (SD = 11.3) years (Supplemental Table 2). During bout 1, the 2 mg film yielded a mean Cmax of 5.45 ng/mL (SD = 4.6) observed at 60 min post film administration (nicotine boost of 3.23 ng/mL (SD = 1.7)) while the 4 mg film yielded a mean Cmax of 8.01 ng/mL observed at the 60 min time point (nicotine boost 6.22 ng/mL (SD = 4.7)). Again, as expected, the placebo film did not result in any increase in plasma nicotine concentration (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean Plasma Nicotine Concentrations by Nicotine Film Dose Group (Experiment 2: Multiple-Dose Administration).

Participants across all dose groups reported craving relief on the QSU after consuming the film (Supplemental Fig. 4). Participants rated the positive effects of the films moderately and there were no clear dose-response effects in the subjective ratings of the films (Supplemental Fig. 5). Like the single-dose administration, those in the placebo group preferred the taste of their film which could have influenced their other ratings (e.g., also rating highly for enough nicotine, relieving withdrawal symptoms, and being satisfying).

Doses of the films were well tolerated and repeated administration of the nicotine films did not meaningfully alter blood pressure (Supplemental Fig. 6) or heart rate (Supplemental Fig. 7). A total of six adverse events (AEs) were reported by five subjects in the study (Supplemental Table 4). There were two related AEs among those in the random group; nausea and an increase in blood pressure from baseline. Four adverse events were reported in the steady-state group; two were an increase in blood pressure from baseline, one was hiccups, and one was dizziness. All AEs were deemed at least possibly related to the study and no serious AEs occurred.

3.2. Cessation study (Experiment 3)

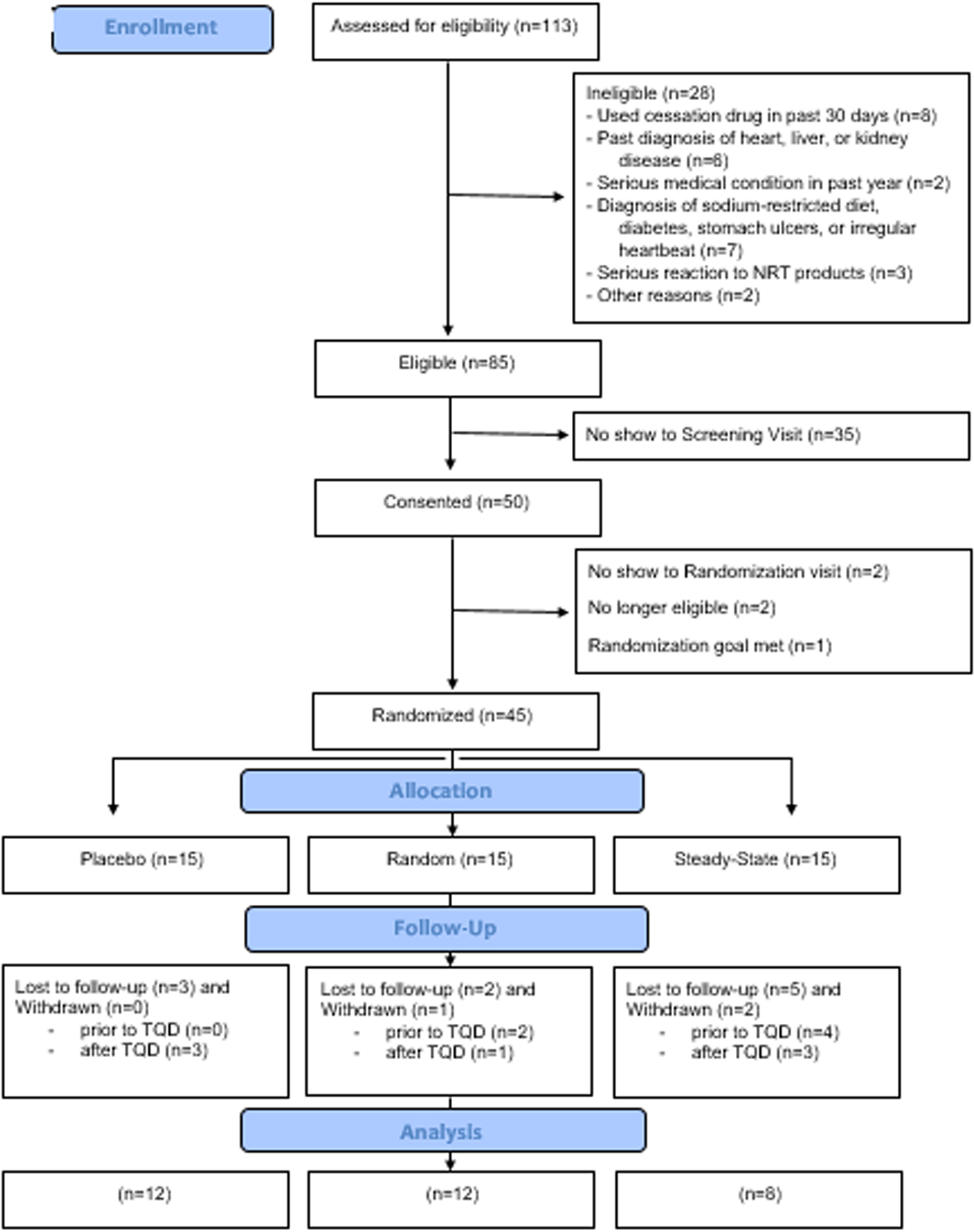

Participants (n = 45) in the cessation study were 24.4 % male, 93.3 % white, and were a mean age of 43.1 years (Supplemental Table 3). There were no differences in baseline demographic characteristics by group.

Overall, 71.1 % (32/45) of participants completed the study, with no significant differences between groups. A diagram displaying screening, enrollment, intervention allocation, and follow-up is displayed in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

CONSORT diagram (Experiment 3: Cessation Study).

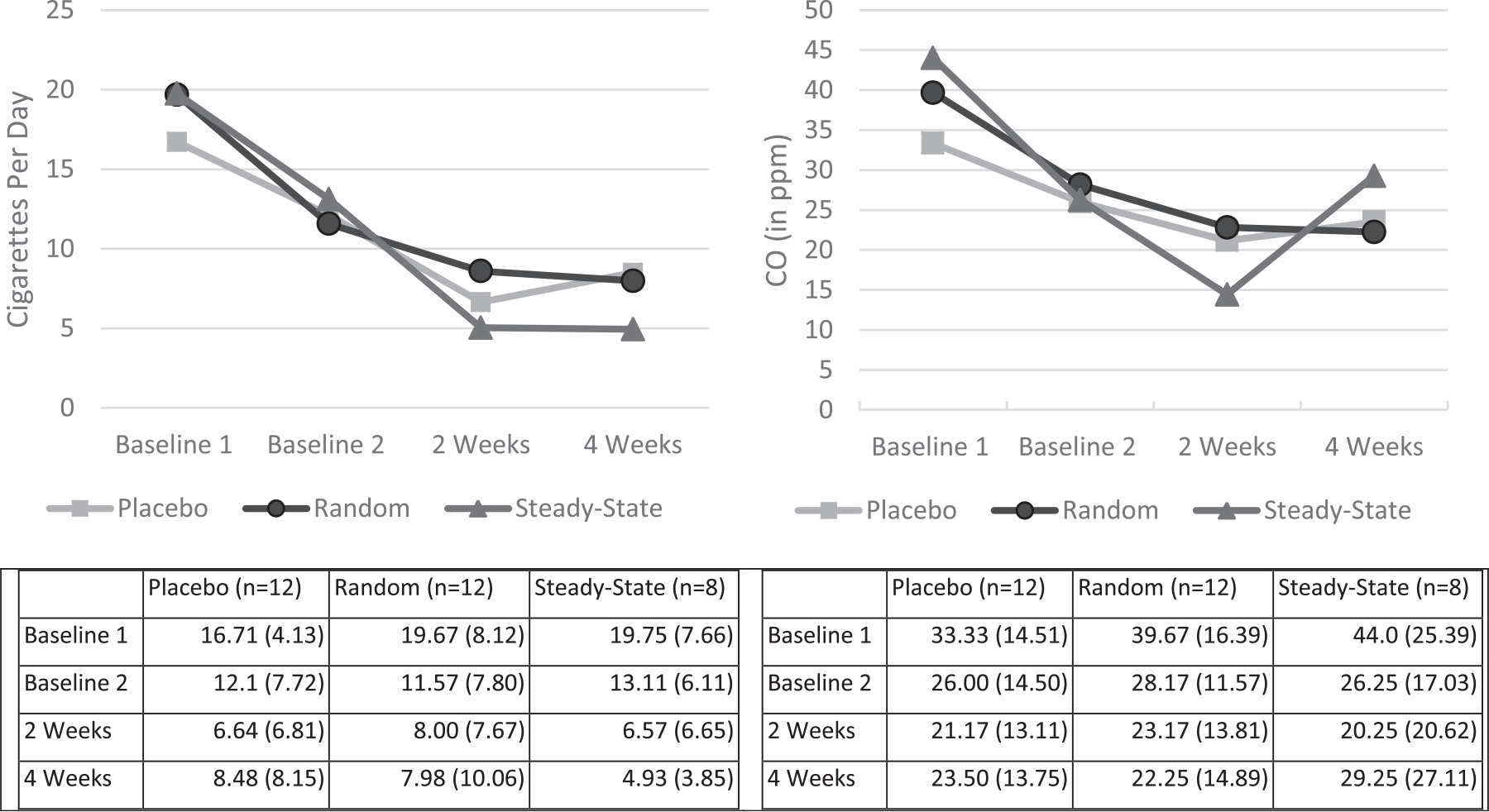

There was a significant reduction in cigarettes smoked per day overall among all participants from baseline to 4-weeks post-TQD (18.71 v. 7.13 CPD) (ME Trial: F(3, 87) = 60.96, p < 0.0001; ) (Fig. 5, left panel). This large effect was exhibited by each group independently and there were no significant differences between groups (ME Group: F<1; Cohen’s d (week 1 vs week 4) = 1.27 placebo, 1.28 random, and 2.44 steady). Four participants reduced their cigarette smoking to 0 CPD at 4-weeks post-TQD. Of those who reported stopping smoking, 1 was in the placebo group, 1 was in the steady-state group, and 2 were in the random group.

Fig. 5.

CPD and CO reduction from baseline to the 4-week Follow-up (Experiment 3: Cessation Study).

There also was a significant reduction in exhaled CO among all participants from baseline to 4-weeks post-TQD (F(3, 87) = 15.09, p < 0.0001, ; 39 ppm v. 25 ppm (Fig. 5, right panel). Again, this effect was exhibited reliably by each group independently (Placebo: F(3,33)= 8.23, p < 0.0003; Random: F(3, 33) = 5.09, p < 0.005; Steady: F(3, 21) = 4.33, p = 0.016) and there were no differences between groups (ME Group: F<1; Cohen’s D (week 1 vs week 4) = 0.70, 1.11, 0.56, respectively). Although there were no reliable differences in exhaled CO reduction by group, there were notable differences in the magnitude of the effect size. The reduction in exhaled CO was twice as large in the random group (d = 1.11) compared with the steady group (d = 0.56). The mean CO of those who reported quitting (n = 4) was 5 ppm (SD = 2.7) (Range 3–9 ppm).

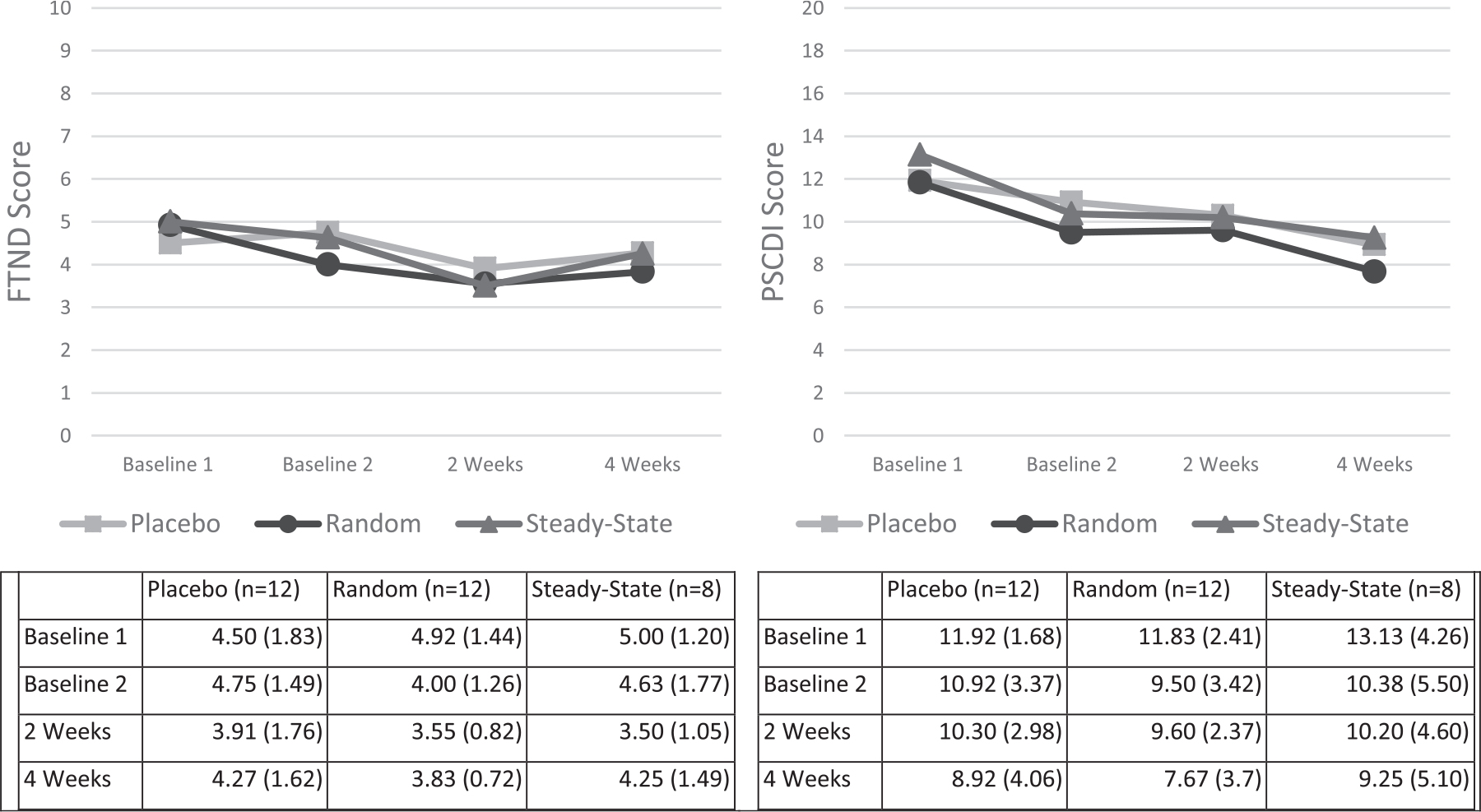

Among all participants, there was a significant decrease in dependence from baseline to 4-weeks post-TQD on both measures of dependence, the FTND (4.8 v. 4.1, ME: Trial, F(3, 81) = 6.67, p < 0.0004) and the PSCDI (12.2 v. 8.5, ME: Trial, F(3, 87) = 15.01, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6). There were no differences in dependence reduction from baseline to the 4-week post-TQD by group for either scale, FTND (Placebo −0.5, Random −0.9, Steady −0.5, Fs<l) or the PSCDI (Placebo −2.7, Random −3.5, Steady −2.7, Fs<l).

Fig. 6.

FTND and PSCDI Score from Baseline to the 4-week Follow-up (Experiment 3: Cessation Study).

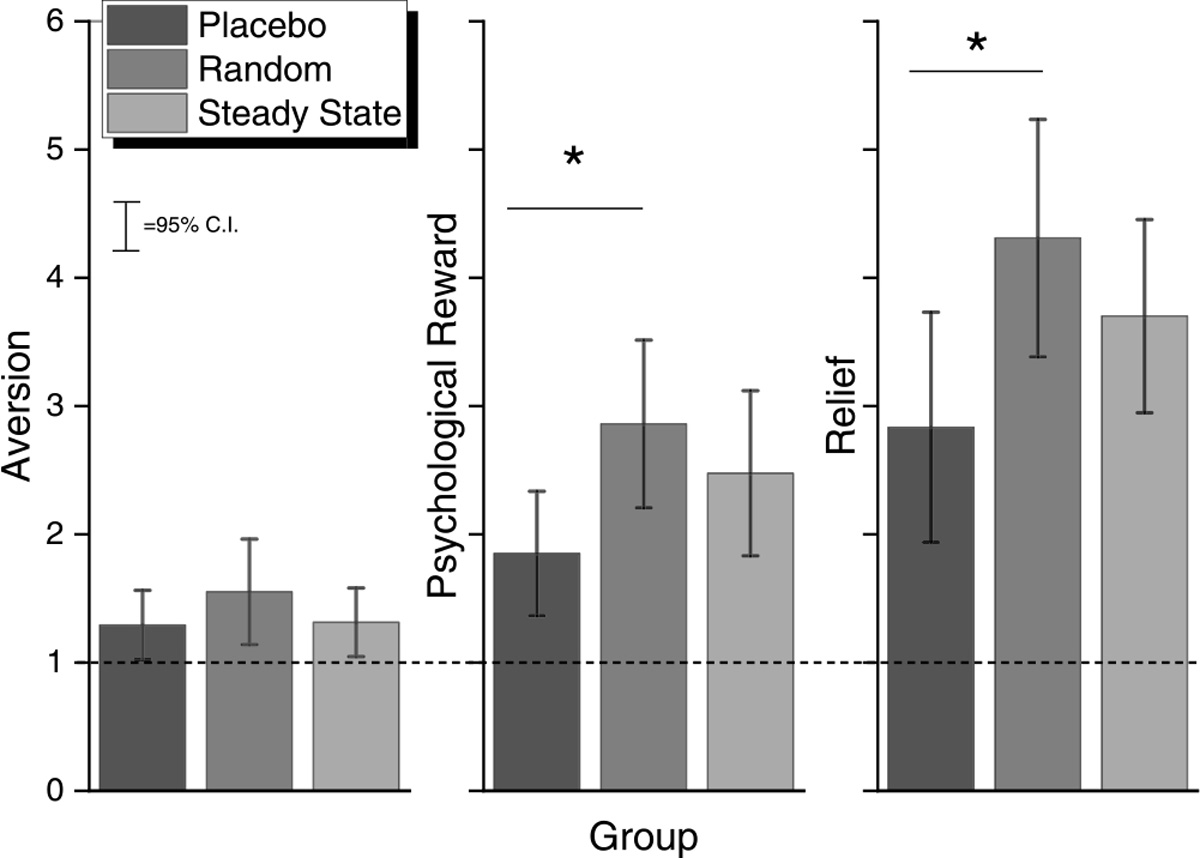

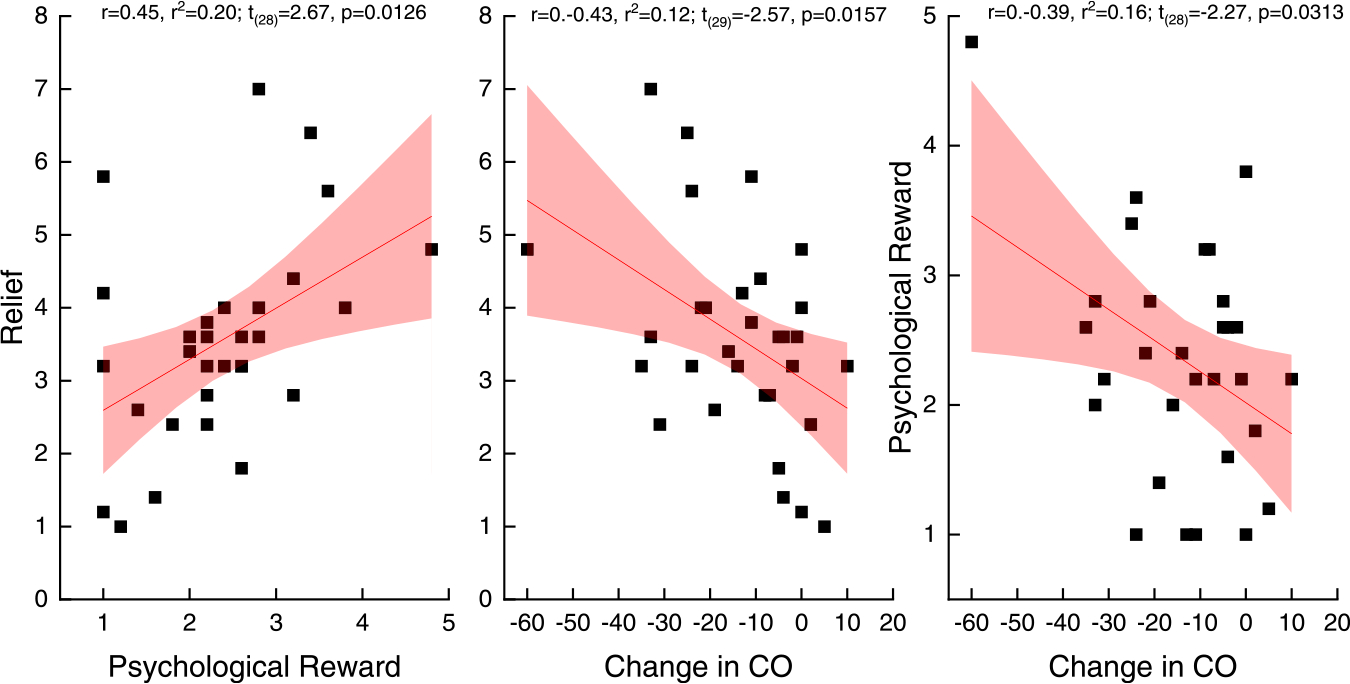

At the 4-week post-TQD, participants in the placebo, RND, and steady-state groups each rated the film aversive as the lower bound 95% confidence intervals did not cross the minimum value indicating “no aversion”. There were no differences among the treatment groups, F (2,36) < 1, p = 0.3823, planned contrasts, all p > 0.19 (see Fig. 7, left panel). RND participants also rated the films as more psychologically rewarding than participants in the placebo group (Fig. 7, middle panel). This conclusion was supported by post hoc LSD and Tukey HSD tests (all p < 0.05) of a significant main effect of group, F (2,27) = 4.27, p < 0.0244. Along with an increase in psychological reward, post hoc LSD and Tukey HSD tests of a significant main effect of group, F (2,28) = 3.80, p = 0.0346, also revealed that participants in the random group reported greater relief compared with participants in the placebo control group, all p < 0.05 (see Fig. 7, right panel). Overall, greater relief was associated with greater psychological reward, r = 0.45, r2 = 0.20; t(28) = 2.67, p = 0.0126, and both greater relief, r = 0.–0.43, r2 = 0.12; t(29) = −2.57, p < 0.0157, and greater psychological reward, r = 0.–0.39, r2 = 0.16; t(28) = −2.27, p < 0.0313, were associated with a greater reduction in exhaled CO, (Fig. 8, left, middle and right panels). Degree of reported aversion was not correlated with exhaled CO, p = 0.34.

Fig. 7.

Aversion, Psychological Reward, and Relief as a function of group at the 4-week Follow-up (Experiment 3: Cessation Study).

Fig. 8.

Correlation of relief and psychological reward (panel A) and relief and CO reduction (panel B) and psychological reward and CO reduction (panel C) from baseline to the 4-week follow-up. (Experiment 3: Cessation Study).

Forty-four adverse events were reported throughout the cessation study by 28 participants. Most commonly reported related adverse events were heartburn (n = 7), hiccups (n = 7), nausea (n = 6), vomiting (n = 2), and anxiety (n = 2) (Supplemental Table 4). There were no significant differences in the total number of adverse events reported by group (p = 0.35). In addition, participants reported few side effects with the mean total side effect score of 17.0 (potential score range of 12–48, with higher scores indicating greater side effects) (SD = 4.5). The most commonly reported side effects were experiencing mucus in throat/sinuses, dry mouth, changes in taste, and dehydration. There were no differences in total side effect score (p = 0.35) or individual side effects experienced by group (all p > 0.1).

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence that random nicotine delivery is feasible in a human population using an orally-dissolving film product manufactured in varying nicotine strengths including 0 mg. The films designed for this study delivered nicotine as expected, with the 4 mg film delivering a nicotine boost of approximately 6–12 ng/mL across both the single and the multiple dose administration studies. Compared with commercially-available FDA-approved nicotine replacement products like the nicotine gum, the films in this study delivered slightly more nicotine in a similar amount of time (Azzopardi et al., 2022; Gupta et al., 1993; Choi et al., 2003). For example, in Azzopardi et al., they found a Cmax of 8.8 ng/mL and a Tmax of 60 min (median) (Range: 10–180 min) after single use of the nicotine lozenge (Azzopardi et al., 2022). In addition, side effects and adverse events experienced by participants, such as hiccups and nausea, occurred infrequently and were similar in nature to side effects reported in studies of oral NRT products (McNabb et al., 1982; Pack et al., 2008). Also, participants did not experience any changes in blood pressure or heart rate across groups. While it is possible that the timing of our measurements missed these differences, it is also possible that the use of the films had no impact on these measures (Pickering, 2001).

Of interest, participants in the single dose administration study appeared to absorb more nicotine across both active doses (2 and 4 mg) compared to participants in the multiple dose administration study. Some of these differences may be due to individual differences compounded by a small sample size (Supplemental Fig. 8). Future studies should measure the nicotine metabolite ratio (3-hydroxycotinine) of each participant to better understand the impact of individual differences. It is also possible that the peak nicotine concentration may have been missed in the multiple dose study since there were less frequent blood draws. While nicotine delivery did vary across groups, the subjective ratings for the films did not differ, suggesting a placebo effect (Perkins et al., 2003). We found that only 25 % (n = 3/12) of those randomized to the placebo group correctly identified that their films did not contain nicotine at the end of the study, providing further evidence of a placebo effect. Future research is needed to better understand the placebo effect and how it impacts smoking cessation.

In the cessation study among smokers interested in quitting, we found that all participants experienced a reduction in self-reported CPD, exhaled CO, and nicotine dependence. RND was not associated with a significantly greater decrease in CPD from baseline to 4-weeks post-TQD compared to the other groups, but of the 4 participants who quit at that follow-up visit, half were from the RND group. RND was associated with similar aversion, greater psychological reward, and greater relief compared to the placebo group, as measured by the modified CES. Greater relief was correlated with greater psychological reward and both of these metrics were associated with a greater reduction in exhaled CO.

There are a number of limitations to the study. First, this pilot study utilized a small sample size. Future research with a larger sample size and powered to detect differences between groups will lead to greater confidence in the findings. In addition, this study did not utilize a crossover design to test differences between conditions, therefore comparisons between conditions may have higher variability due to different populations being studied. Also, participant drop-out was high, although not uncommon in cessation trials (Belita and Sidani, 2015). While the main analysis excluded participants who did not complete the study, we also used the LMER and LME4 packages in R to analyze the data with a linear mixed model (LMM), to account for the missing data. Despite retaining more participants with the LMM, the means and pattern of results were similar and therefore did not alter the conclusions.

In addition, this study was the first test of the dosing schedule for RND. For safety reasons, and based on the variability in nicotine obtained in Experiment 1 and 2, we used a modest dosing schedule. A slight change in parameters, such as an increase in the number of films administered from 4 to 6 per day and possibly the use of a 6 mg film (The FDA would only approve doses of 4 mg or less because the product was novel), may prove more effective. This possibility is supported by past animal work by our team which found that random delivery of higher doses of cocaine was associated with greater aversiveness and with greater protection (Twining et al., 2009). Finally, the present study was short. Greater smoking cessation might be obtained with random nicotine delivery following 8 or 12 weeks of treatment, rather than only 4. Twelve weeks of treatment is standard to many smoking cessation studies (Jackson et al., 2019).

In conclusion, we found that the films developed for this study delivered nicotine as expected and were safe and well tolerated by participants. When these films were used to pilot test the effectiveness of RND for smoking cessation, we did not find any significant differences in CPD or CO when compared to the steady-state and placebo groups. Future research is needed to determine the optimal parameters for the RND treatment regimen and to determine whether RND has an effect on smoking cessation.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R21 DA038775 and by the Penn State Clinical & Translational Research Institute, Pennsylvania State University CTSI, NIH/NCATS Grant Number through grant UL1 TR000127 and UL1 TR002014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA or NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

JF has done paid consulting for pharmaceutical companies involved in producing smoking cessation medications, including GSK, Pfizer, Novartis, J&J, and Cypress Bioscience. HST is the Director of Ventures & Technologies at Bionex Pharmaceuticals LLC. The other authors have no disclosures to report related to this publication.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.07.017.

References

- Azzopardi D, Ebajemito J, McEwan M, et al. , 2022. A randomised study to assess the nicotine pharmacokinetics of an oral nicotine pouch and two nicotine replacement therapy products. Sci. Rep. 12 (1) (6949). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A, 2017. Quitting smoking among adults - United States, 2000–2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65 (52), 1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belita E, Sidani S, 2015. Attrition in smoking cessation intervention studies: a systematic review. Can. J. Nurs. Res. = Rev. Can. De. Rech. En. Sci. Infirm. 47 (4), 21–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Stafford AM, Dixon CI, 2015. Nicotinic receptor contributions to smoking: insights from human studies and animal models. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2 (1), 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Dresler CM, Norton MR, Strahs KR, 2003. Pharmacokinetics of a nicotine polacrilex lozenge. Nicot. Tob. Res. 5 (5), 635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Bigelow GE, Walsh SL, 2006. Comparing the physiological and subjective effects of self-administered vs yoked cocaine in humans. Psychopharmacology 186 (4), 544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Stapleton JA, 2006. Nicotine replacement therapy for long-term smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Tob. Control 15 (4), 280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG, 1989. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J. Behav. Med 12 (2), 159–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, 2009. The relevance and treatment of cue-induced cravings in tobacco dependence. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 36 (3), 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Stapleton J, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Jarvis M, Russell MA, 1992. Effect of transdermal nicotine patches on cigarette smoking: a double blind crossover study. Psychopharmacology 106 (3), 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, et al. , 2015. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking E-cigarette users. Nicot. Tob. Res.: Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicot. Tob. 17 (2), 186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Okerholm RA, Coen P, Prather RD, Gorsline J, 1993. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of nicoderm® (Nicotine Transdermal System). J. Clin. Pharmacol. 33 (2), 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42 (2), 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Zhang Y, O’Connor RJ, Severson HH, 2013. Subjective responses to oral tobacco products: scale validation. Nicot. Tob. Res.: Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicot. Tob. 15 (7), 1259–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth L, 2012. Goal-directed and transfer-cue-elicited drug-seeking are dissociated by pharmacotherapy: evidence for independent additive controllers. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. B 38 (3), 266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, McGowan JA, Ubhi HK, et al. , 2019. Modelling continuous abstinence rates over time from clinical trials of pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation. Addiction 114 (5), 787–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNabb ME, Ebert RV, McCusker K, 1982. Plasma nicotine levels produced by chewing nicotine gum. JAMA 248 (7), 865–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack QR, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, et al. , 2008. A comparison of the nicotine lozenge and nicotine gum: an effectiveness randomized controlled trial. WMJ 107 (5), 237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Benowitz N, Shields P, et al. , 2003. Individual differences in nicotine intake per cigarette. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 12 (5), 468–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins K, Sayette M, Conklin C, Caggiula A, 2003. Placebo effects of tobacco smoking and other nicotine intake. Nicot. Tob. Res.: Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicot. Tob. 5 (5), 695–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering TG, 2001. The effects of smoking and nicotine replacement therapy on blood pressure. J. Clin. Hypertens. 3 (5), 319–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, 2011. Nicotine preloading: the importance of a pre-cessation reduction in smoking behavior. Psychopharmacology 217 (3), 453–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Ferguson SG, 2008. Nicotine patch therapy prior to quitting smoking: a meta-analysis. Addiction 103 (4), 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ, 1991. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br. J. Addict. 86 (11), 1467–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining RC, Bolan M, Grigson PS, 2009. Yoked delivery of cocaine is aversive and protects against the motivation for drug in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 123 (4), 913–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Asman K, Gentzke A, 2018. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67 (44), 1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.