Abstract

Mental and substance use disorders are leading contributing factors for the Australian non‐fatal burden of disease. These disorders frequently co‐occur in the mental health population, and mental health nurses are the largest group of professionals treating dual diagnosis. A comprehensive understanding of mental health nurses' attitudes and perceptions is required to inform future implementation of dual diagnosis training programs. A systematic literature review of sources derived from electronic databases including Medline, CINAHL, SCOPUS review, and PsychINFO, along with Connected Papers. Selection criteria included a focus on mental health nurses' attitudes towards dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance use. Extracted data was qualitatively synthesized. Of the 5232 articles retrieved initially, 12 were included in the review. Four themes emerged from the synthesis: drug and alcohol use among mental health consumers (seven studies), caring for dual diagnosis consumers (eight studies), role perception (six studies), and treatment optimism (five studies). Salient beliefs included substance use as a self‐inflicted choice (71%) or a form of ‘self‐medication’ (29%); a lack of willingness to provide care (75%), or a strong commitment to care (25%); greater comfort with screening and acute medical management rather than ongoing management (83%); and pessimism about treatment effectiveness (100%). Mental health nurses' beliefs and attitudes towards dual diagnosis were often negative, which is likely to result in poor quality care and treatment outcomes. However, the lack of recent studies in this research area indicates the need for up‐to‐date knowledge that can inform the development of training programs.

Keywords: attitudes, drug and alcohol, mental health, nursing, perceptions, substance use

INTRODUCTION

Mental and substance use disorders (SUDs) are leading contributing factors for Australian non‐fatal ‘burden of disease’ (measured by years living with disability) according to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 (Ciobanu et al. 2018). There is a high prevalence of dual diagnosis between mental disorders and SUDs. Up to 90% of people accessing substance use treatment also experience comorbid mental health problems (Kingston et al. 2017). Indeed, harmful use of alcohol has been found to cause mental disorders (Alcohol 2018). Conversely, individuals with mental health conditions are more likely to engage in harmful use of alcohol than individuals without mental health conditions (lifetime risky drinking levels of 21% compared to 17.1%) (Alcohol, Tabacco and Other Drugs in Australia 2021). It has been reported that up to 77% of people with major mental illness like schizophrenia spectrum disorders, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and bipolar disorder may also have SUDs or alcohol use disorders (AUDs) in their lifetime (Guy et al. 2018; Hunt et al. 2016, 2018).

Problematic alcohol and other drug use among individuals with mental disorders is also related to poor outcome (Kingston et al. 2017). Dual diagnosis is associated with greater symptom severity, reduced quality of life, and increased reliance on treatment services compared to SUD alone (Curran et al. 2008; Mark 2003). Despite the high prevalence of dual diagnosis, it is underestimated, under‐diagnosed, and treatments are often unsatisfactory (Jane‐Llopis & Matytsina 2006). There is therefore an urgent need to improve integration between mental health and substance use services, which can be achieved through networking, integrated models of service, and a recognition of the varying treatment needs of each individual (Fantuzzi & Mezzina 2020).

Historically, mental health and alcohol and other drug (AOD) services have operated separately with regard to the delivery of care in many jurisdictions, which can present challenges for those intending to access appropriate services (Teesson et al. 2009). This segregated approach to care has limited treatment resource capacity, including clinical skills, practice competencies, and a lack of clinician‐related willingness to manage comorbid conditions. Siloed health services have contributed to a lack of understanding of substance use among mental health clinicians, and a lack of understanding of mental disorders among drug and alcohol clinicians (Sterling et al. 2011). An integrated intervention approach often focuses on screening and assessment of mental health or SUD problems rather than management of both disorders (Alsuhaibani et al. 2021). At the provider level, clinicians can provide integrated care by learning specialized skills to assess and treat both conditions simultaneously. Furthermore, integrated care can also occur at the service level whereby separate services collaborate and consultancy capacity between specialized services is facilitated.

As the largest group in the mental health workforce, nurses provide care service coverage 24/7 across the healthcare settings, and a significant proportion of their duties involve consumer interactions (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021). Mental health nursing is a unique profession that facilitates therapeutic effects via interpersonal nurse–patient relationships. Mental health nurses promote mental health and wellbeing by generating human connection in a trauma‐informed way, espousing kindness, and demonstrating respect for the persons' lived experience of mental health problems (Anandan et al. 2020). When mental health professionals display negative or discriminatory attitudes towards consumers who present with drug and alcohol problems, these attitudes can become barriers to effective care (van Boekel et al. 2013). Social psychologists defined attitude as the reflection of the person's underlying values, which predict behaviour in reference to these values. Properties of attitude evolved from past experiences, feelings, and associated beliefs about an object (Haddock & Maio 2004). Indeed, positive attitudes are a prerequisite for therapeutic engagement and enhancement of AOD knowledge and treatment skills for mental health nurses and can optimize integrated care capacity. In contrast, when displaying negative attitudes towards clients with dual diagnosis, nurses can impede consumers' recovery due to service disengagement and treatment non‐compliance (Anandan et al. 2020).

A comprehensive understanding of attitudes and perceptions in nurses is required to inform future implementation of training programs aimed to improve the management of dual diagnosis by mental health nurses. This study thus aimed to explore the perceptions and attitudes of mental health nurses towards alcohol and other drug use in mental health consumers with a comprehensive systematic synthesis of the literature. Three research questions guiding this process included: (i) What are mental health nurses' perceptions and attitudes towards drug and alcohol use within the mental health population? (ii) How do mental health nurses perceive their role perception in the management of dual diagnosis? And (iii) What factors influence mental health nurses' attitudes towards the problems of alcohol and other drugs?

METHODS

The present systematic review was conducted in accordance with the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Protocols (PRISMA‐P) statement (Moher et al. 2009), and is being reported in line with the enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of the qualitative research (ENTREQ) statement (Tong et al. 2012).

Synthesis methodology

A narrative synthesis was performed given that the outcome variables were a heterogeneous collection of qualitative data. The main methods of synthesis involved tabulation using ‘meta‐matrices’ (Miles & Huberman 1994), textual descriptions, and a qualitative synthesis of themes (Popay et al. 2006).

Inclusion criteria

Criteria for considering studies for this review were classified by:

Population and setting

In order to meet inclusion criteria, studies had to involve participants that were mental health nurses employed by mental health services. However, the mental health team often involves clinicians from a range of disciplines such as medical officers, allied health professionals, and nurses providing comprehensive care for the mental health population. Therefore, studies were included that comprised at least 50 % of mental health nurses in the respondent groups.

Study design

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies were included.

Outcomes

The review focused on mental health nurses' attitudes towards dual diagnosis of mental illness, illicit substance use, and harmful alcohol consumption. Studies including outcome variables measuring the participants' attitudes towards problematic drug and alcohol use in mental health service users were included. Studies of clinician attitudes towards tobacco smoking were excluded because the culture of smoking is socially accepted as a stress management tool for consumers (Sheals et al. 2016). Studies about forensic mental health nursing were also excluded given the highly secure drug‐free environment in this setting.

Data sources

The following electronic databases were searched: Medline, CINAHL, SCOPUS review, and PsychINFO. Reference searches of relevant reviews and articles were also conducted. Similarly, a grey literature search was done with help of Google and the Grey Matters tool which is a checklist of health‐related sites organized by topic. The tool is produced by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH 2018 (cited 2019 Feb 22)).

Search strategy

The search included all relevant peer‐reviewed studies with no year limit. Table S1 lists the search terms used. An additional, connectedpapers.com was used to identify the papers connected to the selected articles. Connected Papers is a web‐based research tool that helps to explore other linking papers in similar research fields (https://www.connectedpapers.com/?s=09).

Study screening methods

First, titles and abstracts of articles returned from initial searches were screened based on the eligibility criteria outlined above. Second, full texts were examined in detail and screened for eligibility. Third, references of all considered articles were hand‐searched to identify any relevant report missed in the search strategy by the same two reviewers independently. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. EndNote version X9 (Clarivate Analytics), was used to manage all records.

Quality assessment

This study used the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 to assess bias at the individual study level (Hong et al. 2018). MMAT is developed to critically appraise the quality of empirical studies using qualitative, quantitative, and mixed‐method research. Instead of calculating the overall score, MMAT provides more criterion details to better inform quality assessment.

RESULTS

Search results

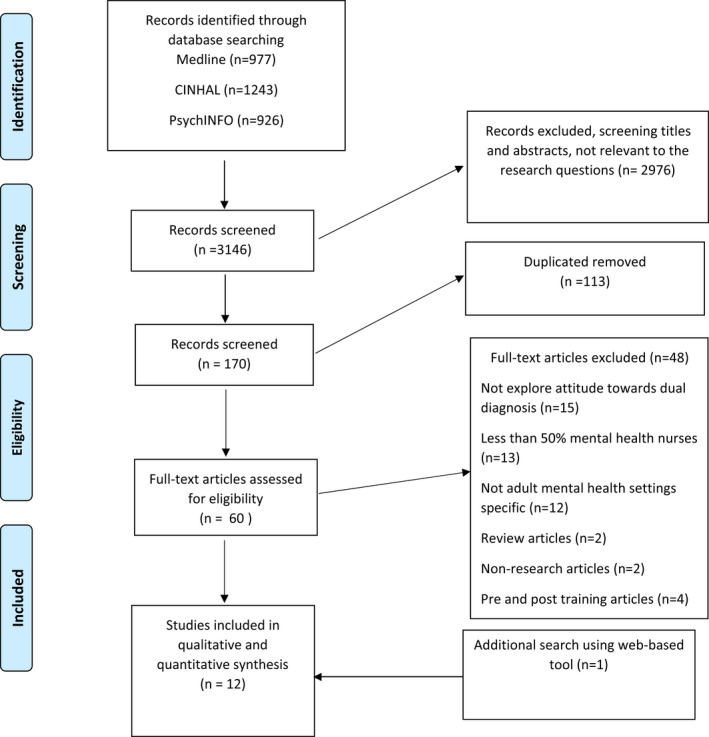

As displayed in the flowchart (Fig. 1), the initial search resulted in 5232 articles derived from health science databases including Medline (n = 977), CINHAL (n = 1243), PsychINFO (n = 926), and Scopus (n = 2086). The first screening of the titles and abstracts yielded 60 relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria covering mental health nurses' attitudes towards drug and alcohol use within mental health settings. Finally, full‐text of these studies were assessed for eligibility and 12 were included in the review. Studies were excluded that did not explore attitudes (n = 15), recruited less than 50% mental health nurses (n = 13), did not include attitudes about the adult drug and alcohol and mental health population (n = 12), described measurement of attitudes linked to pre and post training (n = 4), or were review articles (n = 2) and non‐research articles (n = 2). Twelve articles were selected for the pooled analysis, including 11 from the database search and one from the web‐based search tool.

Fig. 1.

Systematic review flowchart.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and findings of the included studies on mental health nurses' perceptions and attitudes towards alcohol and other drug use in mental health clients.

Table 1.

Findings from the included studies on mental health nurses' perceptions and attitudes towards alcohol and other drug use in mental health clients

| Author | Study design | Population and sample size | Settings | Outcome measures | Results and comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryrie and McGowan (1998) (UK) | Qualitative | N = 20 (mostly mental health nurses) | Acute mental health inpatient | Semi‐structured staff questionnaire with 16 items covering demographic and professional data, previous drug health training and work experience, perception of dual diagnosis and clinical management, training and support | Drug and alcohol use was perceived as problematic, associated with symptoms exacerbation, prolonged recovery, and provoking other social and legal issues. The nurses felt ill‐prepared to provide appropriate care for mental health consumers with concurrent drug and alcohol use problems. They expressed discontent with the scarcity of policy and protocol to guide clinical practice to manage substance use in acute mental health facilities. |

| Williams 1999 (UK) | Quantitative with written comments | N = 127, 40% were nurses | Mental health clinicians working at United Bristol Healthcare Trust – across settings | Attitudes to Substance Use Questionnaire covering demographic and professional data, perception of substance use in causing of mental health issues, role perception regarding assessment and referral, opinions on drug screen assessment and treatment optimism |

Nurses were more likely to ascribe the causation of mental illness due to substance use and valued the importance of drug screen assessment than psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, and physiotherapists Nurses perceived that recreational substance use is common and does not necessarily lead to mental illness. They believed that there should be a specialist dedicated ward to provide care for drug‐related consumers |

| Happell et al. (2002) (Australia) | Quantitative | N = 134 mental health nurses | Metropolitan community | Developed questionnaire Substance Abuse Attitude Survey covering knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills in drug health | The nurses felt confident in their clinical competence of alcohol and substance screening assessment among mental health consumers but not the clinical interventions. They perceived making referral pathways part of their role, while only half of them considered role responsibility for comorbid management |

| Deans and Soar (2005) (Australia) | Qualitative | N = 13 with 10 were mental health nurses (77%) | Rural community | In‐depth interviews conducted to capture feelings and experiences when caring for dual diagnosis consumers | Mental health professionals commonly experience the feeling of frustration in caring for dual diagnosis consumers. They believed mental health consumers use drugs and alcohol to self‐medicate psychotic symptoms. Believed that treatment tends to be ineffective, resulting in prolonged discharge plans |

| Coombes and Wratten (2007) (UK) | Qualitative | N = 7 mental health nurses | Community | Semi‐structured interviews conducted face‐to‐face using audio tape‐recorded and transcribed for the data analysis stage | Believed that they are not adequately equipped with regards to dual diagnosis knowledge and skills. They also tended to believe that all dual diagnosis clients are violent and unpredictable |

| Wadell and Skrster (2007) (Sweden) | Qualitative | N = 11 mental health nurses | Acute mental health inpatient | Participants were asked to describe a caring encounter where they were involved in managing patients with depression and alcohol use problems. During the interviews, further prompted questions were asked to elaborate on the participants' choice of words and their intended meaning | The importance of therapeutic engagement and transparency in patient communication regarding alcohol‐related harmful effects was highlighted. Believed talking about alcohol use is a part of their job, but primarily assumed this task should be the doctor's responsibility |

| Ralley et al. (2009) (UK) | Statistical analysis using repertory grids data | N = 12 mental health nurses | Long stay low‐secure mental health units | Repertory grid technique to understand how mental health nurses construe dual diagnosis consumers in their workplace | Consumer‐related drug and alcohol misuse were more likely to be construed as problematic by the nurses compared to drug and alcohol use by acquaintances |

| Howard and Holmshaw (2010) (UK) | Descriptive mixed methods – quantitative and qualitative |

Quantitative: N = 84 with 41 were mental health nurses and 11 other (e.g. environment co‐ordinator, welfare rights worker, nurse specialist) (50–62%) Qualitative: N = 10 multidisciplinary staff with 2 were nurses |

Mental health inpatient for assessment, treatment and residential rehabilitation units | Co‐occurring Mental Health and Illicit Substance User Perception Questionnaire measured attitude and professional role in perceived knowledge and personalized perceptions. Interview questions explored the participants' experiences working with mental health consumers with co‐occurring drug and alcohol problems in the inpatient setting, multidisciplinary accountability, training and support, and enabling factors and barriers to effective care for this population |

Mental health staff with clinical experience in both acute inpatient and residential rehabilitation were less likely to have negative attitudes compared to those who only have worked in just one of these settings Additional drug‐related problems the consumer brings into clinical care units (such as supplying drugs to other patients or increased aggression due to substance withdraw) were highlighted as the main reasons for staff unwillingness to provide care. Experiences of distress working with consumers with a substance use history were reported |

| Lundahl et al. (2014) (Sweden) | Qualitative | N = 15 Registered nurses working at three psychiatric wards dedicating for patients with substance dependence particularly patients with a history of GHB/GBL abuse | Acute inpatient mental health unit dedicated for substance‐dependent consumers in urgent need of mental health care | Themes of discussion covered withdrawal symptoms, medications, medicine distribution, knowledge, and communication | Attitudes related to GHB/GBL consumers included vigilance around early warning signs of aggressive behaviour. Despite the negative feelings derived from treatment‐related challenges, nurses continued to nurture therapeutic alliance when providing care for mental health consumers with comorbid GHB/GBL problems. They used a range of strategies to establish consumer engagement including open communication, promotion of psychological safety, and respect |

| Johansson and Wiklund‐Gustin (2016) (Sweden) | Participatory research approach | N = 6 mental health nurses | Unspecified inpatient mental health | Four reflective dialogues were conducted to shared experiences of caring for substance use disorder patients | Four themes included the balance between understanding and frustration, being supportive or a guardian of order, safeguarding the healthy while being observant of problems, and protecting oneself while engaging in a caring relationship. Overall, it was believed that the caring encounter can be balanced out with other regulatory requirements in the psychiatric care environment, but it requires the nurses to remain multifaceted and vigilant in all aspects of care |

| Molina‐Mula et al. (2018) (Spain) | Quantitative | N = 167 mental health nurses | Emergency, short‐stay units, and mental health | Seaman‐Mannello scale including behaviour towards alcohol problems, the dichotomy between therapy and treatment, personal/professional satisfaction when working with patients with alcohol problems, tendency to identify oneself with the ability to help patients with alcohol problem, perceptions towards personal characteristics of those with alcohol problems and nurses' attitudes towards alcohol consumption | Nurses believed that consumers with alcohol problems should be offered medical treatment for their alcohol‐related health problems. Even so, they often expressed dissatisfaction when providing care for alcohol‐related consumers. They disclosed disapproval about alcohol consumption even moderate consumption. Mental health nurses in this study exhibited negative attitudes and were unmotivated about providing care for consumers with alcohol problems. The nurses often preferred to provide care for other groups of consumers over consumers with alcohol problems because they did not provide job satisfaction |

| Siegfried et al. (1999) (Sydney, Australia) | Cross‐sectional | N = 338 with 210 were mental health nurses (62%) | Inpatient, community, and child and adolescent unit | A 47‐item questionnaire was developed which measured the role of the mental health professional in the management of drug and alcohol problems and their willingness to upskill in the area of clinical care for alcohol and other drug use | The majority of respondents regarded working with dual diagnosis consumers to be challenging with regards to treatment effectiveness. They believed their role when caring for these consumers includes assessment and referral to specialized services, but does not include consumer education, and management of comorbidity |

Participant characteristics of included studies

Although five studies involved participants other than nurses, including medical staff and allied health professionals, the majority of participants included mental health nurses (50–77%) (Deans & Soar 2005; Howard & Holmshaw 2010; Siegfried et al. 1999; Williams 1999). The remaining studies recruited only mental health nurses (Coombes & Wratten 2007; Happell et al. 2002; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Lundahl et al. 2014; Ralley et al. 2009; Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Wadell & Skrster 2007). The clinical settings of these studies involved inpatient (Howard & Holmshaw 2010; Jackman et al. 2020; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Lundahl et al. 2014; Pinderup 2016, 2018; Ralley et al. 2009; Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Wadell & Skrster 2007), community (Coombes & Wratten 2007; Deans & Soar 2005; Happell et al. 2002), and multiple mental healthcare facilities (Molina‐Mula et al. 2018; Siegfried et al. 1999; Williams 1999).

Study characteristics

Overall findings identified considerable heterogeneity in research methodologies and inconsistent study outcomes. Various data collection strategies were used across the selected studies, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed‐methods. Seven studies obtained qualitative data (Coombes & Wratten 2007; Deans & Soar 2005; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Lundahl et al. 2014; Ralley et al. 2009; Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Wadell & Skrster 2007), another four studies used questionnaires and surveys (Happell et al. 2002; Molina‐Mula et al. 2018; Siegfried et al. 1999; Williams 1999), and one study used the mixed research methods (Howard & Holmshaw 2010). A diverse range of assessment scales were employed across the studies including Likert scales 1–5 (Molina‐Mula et al. 2018; Williams 1999) and 1–7 (McKenna et al. 2010), and binary variables (Happell et al. 2002).

Quality assessment of studies

Two independent reviewers appraised the selected studies using the MMAT tool. For each study type, an appropriate category is used to assess the quality of selected studies critically. Difference opinions on the appraisal components were managed by discussion. Twelve studies were selected for the review. Table 2 presents details of the quality assessment of the selected studies.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the selected studies using MMAT tool (including items relevant to qualitative studies)

| MMAT Checklist/Selected studies | Ryrie and McGowan (1998) | Williams (1999) | Happell et al. (2002) | Deans and Soar (2005) | Coombes and Wratten (2007) | Wadell and Skrster (2007) | Ralley et al. (2009) | Howard and Holmshaw (2010) | Lundahl et al. (2014) | Johansson and Wiklund‐Gustin (2016) | Molina‐Mula et al. (2018) | Siegfried et al. (1999) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening questions (for all types) | ||||||||||||

| S1. Are there clear research questions? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Cannot tell’ to one or both screening questions. | ||||||||||||

| 1. Qualitative | ||||||||||||

| 1.1 Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| 1.2 Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research questions? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| 1.3 Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| 1.4 Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| 1.5 Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| 2. Quantitative descriptive | ||||||||||||

| 2.1 Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| 2.2 Is the sample representative of the target population? | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| 2.3 Are the measurements appropriate? | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| 2.4 Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Cannot tell |

| 2.5 Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Mixed methods | ||||||||||||

| 3.1 Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3.2 Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3.3 Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3.4 Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3.5 Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Summary of four main attitude themes

Mental health nurses' attitudes towards dual diagnosis management could be placed into the following themes, reflecting the complicated relationships among factors that drive their perception of care for dual diagnosis consumers.

Attitudes towards AOD use among mental health consumers

Of the selected papers, six examined the participants' belief about the intention of drug and alcohol use within the mental health population using both qualitative and quantitative measures (Deans & Soar 2005; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Ralley et al. 2009;Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Williams 1999). Two studies observed that alcohol and drug use among mental health consumers was generally not considered part of their illness but, rather, a self‐inflicted lifestyle behaviour (Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Williams 1999). Ralley et al. (2009) reported that many mental health professionals construed consumer‐related substance misuse as problematic compared to non‐consumer‐related substance misuse, which was deemed habitual. In this study, it was speculated that the consumer was consciously using drugs despite knowing the predictable adverse health outcomes. Moreover, negative attitudes towards consumer's drug use behaviour were expressed, with the underlining assumption that the consumers purposefully negate the attempts made by the treatment team to assist them with their recovery (Ralley et al. 2009). Molina‐Mula et al. (2018) used a discrete quantitative assessment tool, the Seaman‐Mannello scale, to examine nurses' perceptions and attitudes towards alcohol problems. An unfavourable disposition towards consumers with alcohol use problems was observed. The majority of nurses (80.1%) agreed or totally agreed that the ‘life of alcoholics was not pleasant,’ and many (61.9%) agreed that ‘alcoholic patients had poor physical health’. The nurses predominantly displayed negative attitudes towards individuals who drink moderately, they believed it was unhealthy and harmful and made the person ‘weak’.

In contrast, one qualitative study of nurses working in remote areas of Victoria, Australia, expressed sympathy towards consumers with dual diagnosis and demonstrated an understanding with regards to self‐medication of psychotic symptoms or enhancement of social activities (Deans & Soar 2005). A smaller‐scale study also demonstrated that nurses generally agreed that consumers use substances to alleviate their symptoms and cope with their life struggles (Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016).

Attitudes towards caring for mental health consumers with concurrent AOD problems

Eight studies explored mental health nurses' willingness to care for consumers with concurrent problematic drug and alcohol use (Coombes & Wratten 2007; Deans & Soar 2005; Happell et al. 2002; Howard & Holmshaw 2010; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Lundahl et al. 2014; Molina‐Mula et al. 2018; Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Wadell & Skrster 2007). A general lack of willingness to care for consumers with dual diagnosis within the mental health services was observed in several studies. Mental health professionals reported feeling of ‘unsafe’ when caring for dual diagnosis consumers. Reluctance of mental health nurses to engage with dual diagnosis consumers was observed and underlined by a perception that they are violent and unpredictable, and therefore unsafe (Coombes & Wratten 2007). Further reasons for distance in therapeutic engagement included additional drug‐related problems in clinical care units such as supplying drugs to other patients, increased aggression due to substance withdrawal, and ward safety (Howard & Holmshaw 2010). Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin, (2016) examined the attitudes of mental health nurses in a psychiatric inpatient ward. These authors observed that nurses reported being vigilant of manipulative behaviour but reported trying to understand underlying reasons for behaviour. Nurses also reported emotional burden when caring for consumers with drug and alcohol problems and attempts to desensitize to relapses (Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016). Finally, in a large‐scale study involving 275 mental health nurses working across settings, Molina‐Mula and colleagues used the Seaman‐Mannello Scale to examine nurses' attitudes when working with alcohol‐related consumers. Under subscale two measuring job satisfaction, most of the items in this subscale scored less than three out of five, indicating dissatisfaction when providing care for consumers with alcohol problems (Molina‐Mula et al. 2018).

In contrast, a small‐scale study exploring mental health nurses' experience when caring for major depressive disorder and alcohol problems observed a greater willingness to care (Wadell & Skrster 2007). Nurses expressed commitment for providing care for dually diagnosed depression and alcohol problems, supporting trust‐based collaborative relationships as a prerequisite for therapeutic engagement. They would use a variety of engagement approaches when working with dual diagnosis consumers according to what they perceived as the most appropriate in the context, such as paternalism, confrontation, and compassion styles. Similarly, a qualitative study by Lundahl et al. (2014) investigated mental health nurses' views and experiences providing care for consumers using Gamma‐hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), an illicit substance in many countries. This study revealed positive clinical care attitudes including ‘striving for a good relationship’ and ‘striving to optimize and develop nursing care’. It was observed that these mental health nurses demonstrated understanding of a good therapeutic relationship by showing respect, being present, listening, and caring towards the consumers and a desire to foster a calming and comfortable atmosphere so that consumers can feel psychologically safe during their hospital admission.

Attitudes towards role perception

Six studies examined the perceived professional role of dual diagnosis management in mental healthcare (Happell et al. 2002; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Ryrie & McGowan 1998; Siegfried et al. 1999; Wadell & Skrster 2007; Williams 1999). Generally, mental health nurses' role perception of clinical care for dual diagnosis consumers included screening, assessment, consumer education, and acute medical management rather than responsibility for specific interventions for drug and alcohol use, namely motivational interventions (Watson et al. 2013) or psychosocial treatment of dual diagnosis (Cleary et al. 2009). Four studies reported that mental health nurses believed that drug and alcohol assessment, consumer education, and exploring referral pathways are part of their professional role (Happell et al. 2002; Siegfried et al. 1999; Wadell & Skrster 2007). Additionally, one study also reported the need to enhance clinical assessment skills, consumer education and counselling skills, knowledge of substance interaction with prescribed medications, and intoxication management (Ryrie & McGowan 1998).

However, several studies indicated that mental health nurses did not perceive the clinical care or ongoing management of these consumers as part of their role. For example, one study reported that nurses assumed that it should be the doctor's responsibility to talk about alcohol use to mental health consumers (Wadell & Skrster 2007), while another study observed that they believed a dedicated specialist should provide care for drug and alcohol consumers in the ward setting (Williams 1999), or that referring dual diagnosis consumers on to drug and alcohol services is preferable (Happell et al. 2002). By comparison, nurses in one study by Johansson and Wiklund‐Gustin (2016) recognized that their duty was to provide care beyond symptom management for consumers with substance use disorders and to discuss health‐associated problems self‐care strategies, social skills, personal strengths, and resources following withdrawal.

Attitudes towards treatment optimism

Five studies mentioned the nurses' attitudes towards treatment optimism (Coombes & Wratten 2007; Deans & Soar 2005; Johansson & Wiklund‐Gustin 2016; Lundahl et al. 2014; Wadell & Skrster 2007). Four studies consistently reported negative attitudes towards treatment optimism. Deans & Soar (2005) found that nurses commonly expressed frustration in caring for dual diagnosis consumers, claiming that treating mental disorders for this group tended to be ineffective, resulting in prolonged discharge plans. Their prominent negative feelings towards treatment outcomes included frustration, resentment, helplessness, and hopelessness, with a description of treatment ineffectiveness attributable to individual responsibilities rather than situational circumstances (Deans & Soar 2005). Findings from a study of community‐based mental health services where care often requires long‐term commitment revealed that community mental health nurses perceived the SUD as untreatable and time‐consuming (Coombes & Wratten 2007). Regarding specific substances like GHB, Lundahl et al. (2014) discovered that nurses' negative feelings were derived from many treatment‐related factors such as an absence of step‐down community‐based services to promote continuum care following discharge from the hospital and a delay in responding to social services referrals upon discharge, leaving mental health nurses concerned about patients' risk of relapse.

One study reported treatment optimism towards management of depression and alcohol problems whereby nurses believed that informing patients about the harmful effects of alcohol can motivate consumers to abstain from alcohol consumption (Wadell & Skrster 2007). Finally, Johansson and Wiklund‐Gustin (2016) demonstrated that nurses perceived that addressing substance use alone is likely to be ineffective and that intervention should be integrated with mental health care.

DISCUSSION

This review provides a synthesis of the literature that has examined mental health nurses' attitudes and perceptions of mental health consumers with concurrent drug and alcohol problems. Four themes emerged including drug and alcohol use among mental health consumers, caring for dual diagnosis consumers, role perception, and treatment optimism. Overall, there was a mix of positive and negative attitudes across all four themes.

There were predominant beliefs held by mental health nurses regarding personal choice for drug and alcohol use among mental health consumers. Many nurses in the selected studies shared beliefs that consumers with a dual diagnosis make an informed choice leading to the subsequent treatment ineffectiveness and ill‐health. However, the neurobiological theories of drug addiction indicate that relapse to substance use is driven by neuroadaptation and impact on brain function and decision‐making (Kalivas & Volkow 2005). Environmental factors such as employment and societal instability are also strongly associated with and drive patterns of substance use within these communities (Hellman et al. 2015). Importantly, early trauma is also key factor associated with later substance use problems (Lin et al. 2020). Sadly, misconceptions of addiction and addictive behaviour can lead to stereotyping and prejudicial attitudes that are then likely to result in discriminatory clinical care practices against mental health consumers with a history of drug and alcohol use, hence depriving their access to quality care (Yang et al. 2017). Thus, mental health nurses' attitudes towards mental health consumer‐related drug and alcohol use may have flow on effects with regards to effective management of dual diagnosis.

Several studies observed that mental health nurses were somewhat hesitant to be involved in the care of dual diagnosis consumers. One small‐scale qualitative study of 11 Swedish nurses explored mental health nurses' experience when caring for individuals with major depressive disorder and alcohol use problems and reported a willingness to be involved in care that was not observed in other studies that explored illicit drug use (Wadell & Skrster 2007). It is possible that the perception of alcohol use among consumers with major depressive disorder is more acceptable than illegal substance use. Furthermore, mental health nurses across settings expressed open‐mindedness about receiving additional training in the drug and alcohol field including assessment and referral capacity despite predominantly holding the belief that clinical intervention for addiction is beyond their role and the responsibility of the medical team or specialized services (Happell et al. 2002; Wadell & Skrster 2007; Williams 1999). One evidence‐based model for managing dual diagnosis is integrated care (Louie et al. 2018). Integrated care aims to provide coordinated, efficient and effective care that responds to all of the needs of the consumer, requiring both assessment of drug and alcohol and the mental health conditions, along with a comprehensive management plan for treating both problems (Marel et al. 2016) Interestingly, none of the participants considered the responsibility of managing drug and alcohol issues in dual diagnosis consumers to be part of their role. This ambivalence in role perception demonstrates a lack of awareness regarding integrated comorbidity management in the mental health care system, possibly reflecting a somewhat incomplete implementation of contemporary evidence‐based practice to improve quality of care.

Limitations

There was heterogeneity across the selected studies such as the diverse study methods, assessment tools, and attitudes measured. The study population targeted mental health nurses working at specific mental health settings which may not be generalizable for the broader mental health nursing community in other healthcare systems and countries. Moreover, it is possible that small‐scale studies with a highly selective population may be biased towards yielding more optimistic attitudes compared with what might be observed in larger representative sample studies (Lundahl et al. 2014; Wadell & Skrster 2007). For example, Lundahl et al. (2014) selectively recruited senior experienced professionals who worked at psychiatric wards dedicated to drug and alcohol consumers and their perceived drug and alcohol knowledge was moderate to very knowledgeable (86%). These factors are likely to be driving the positive clinical care attitudes that were reported by the nurses, such as striving for optimum care and the therapeutic relationship (Lundahl et al. 2014). It is also important to note that there were few studies included in the review that were conducted recently, and these findings may not represent contemporary attitudes.

Clinical and practice implications

Our findings highlight the existence of attitudes towards drug and alcohol use in mental health consumers that may need to be addressed in order to improve care. Training in drug and alcohol‐related problems can alter pre‐existing negative attitudes and improve mental health professionals' attitudes towards therapeutic care. Educational interventions could be implemented to improve mental health nurses' attitudes towards dual diagnosis management and should cater to specific nursing groups to optimize the desired outcomes (Jackman et al. 2020). For example, nurses who received training in drug and alcohol were less likely to hold negative attitudes towards drug and alcohol problems (Howard & Holmshaw 2010). Several of the studies in this review suggest that many mental health nurses are open to training opportunities to enhance their knowledge and skills in assessing and treating dual diagnosis. Indeed, mental health staff identified training as essential for increasing knowledge and enhancing clinical practice, such as understanding drug awareness, legality matters, and appropriate therapeutic consumer engagement (Howard & Holmshaw 2010). Nurses also suggested that skills might include different engagement approaches depending on the context, building a therapeutic relationship (Lundahl et al. 2014). The lack of treatment optimism could also be addressed by education regarding evidence‐based care. Addressing team attitudes is also likely to be important. Team attitudes have previously been recognized at handovers or multidisciplinary team meetings in which clinicians reported a mix of positive and negative perceptions from team members regarding care for dual diagnosis consumers (Howard & Holmshaw 2010). Structured training programs could incorporate these factors accordingly. Finally, with regards to management approaches such as integrated care (Louie et al. 2018), training packages could be developed (Louie et al. 2021) including the development of clinical practice guidelines along with ongoing clinical supervision (Giannopoulos et al. 2021), clinical champions (Wood et al. 2020) and sufficient time allocation for training (Louie et al. 2021) to facilitate individual and team attitudes and clinical practice change in dual diagnosis management (Lundahl et al. 2014).

CONCLUSION

We conducted a synthesis of the existing literature regarding mental health nurses' attitudes and perceptions regarding drug and alcohol use in mental health consumers. There were mixed attitudes regarding the four emergent themes of drug and alcohol use among mental health consumers, working with these consumers, role perception, and treatment optimism. Fewer recent studies in this research area indicate the need for up‐to‐date knowledge of mental health nurses' perception of care in comorbid management, and the changes of this perception in the context of modern society. Nonetheless, attitudes that may need to be addressed in future training programs to enhance dual diagnosis management include the perception of decision‐making regarding addictive behaviours, safety issues, confidence in and knowledge of effective treatment options, and engagement and management approach. In addition, the extent of training and clinical support for nurses to develop positive attitudes towards providing care for mental health consumers with concurrent drug and alcohol problems remains a contemporary research gap.

RELEVANCE FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

The review broadened our understanding of mental health nurses' perceptions and attitudes towards alcohol and other drug use among mental health consumers. We also found that effective therapeutic care for this population does not only require clinicians to have adequate knowledge about the health problems but also a non‐moralistic approach and positive attitudes towards care. Finally, research‐informed training programs can enhance clinical practice in caring for dual diagnosis consumers by upskilling staff's drug health knowledge and shifting their skewed perceptions towards more optimum care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

KM, PH, EL, and TTM conceived the study and developed research methods. TTM conducted the literature search. TTM and EL independently screened all articles identified from the search. KM, EL, and TTM conveyed finding analysis and interpretation. Studies' appraisal was conducted independently by TTM and LM. TTM wrote the manuscript with the support of KM, EL, MC, AB, and LM. All authors revised and contributed to editing the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Search terms using PICO.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Declaration of conflict of interest: Dr. Michelle Cleary is the Editorial Board Member of the International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Alcohol . (2018). Retrieved from World Health Organization. [Cited 22 July 2021]. Available from: URL: https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/alcohol

- Alcohol, Tabacco and Other Drugs in Australia . (2021). Retrieved from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Alsuhaibani, R. , Smith, D. C. , Lowrie, R. , Aljhani, S. & Paudyal, V. (2021). Scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and substance abuse in relation to dual diagnosis, social and community outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 21 (1), 209–223. 10.1186/s12888-021-03188-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandan, R. , Cross, W. & Olasoji, M. (2020). Mental Health Nurses' attitudes towards consumers with co‐existing mental health and drug and alcohol problems: A scoping review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 42, 346–357. 10.1080/01612840.2020.1806964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CADTH . (2018). Grey matters: A practical tool for searching health‐related grey literature Internet . [Cited 22 February 2019]. Available from: URL: https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters-practical-tool-searching-health-related-grey-literature

- Ciobanu, L. G. , Ferrari, A. J. , Erskine, H. E. et al. (2018). The prevalence and burden of mental and substance use disorders in Australia: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52 (5), 483–490. 10.1177/0004867417751641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, M. , Hunt, G. E. , Matheson, S. & Walter, G. (2009). Psychosocial treatments for people with co‐occurring severe mental illness and substance misuse: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65 (2), 238–258. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes, L. & Wratten, A. (2007). The lived experience of community mental health nurses working with people who have dual diagnosis: A phenomenological study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14 (4), 382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran, G. M. , Sullivan, G. , Williams, K. , Han, X. , Allee, E. & Kotrla, K. J. (2008). The association of psychiatric comorbidity and use of the emergency department among persons with substance use disorders: An observational cohort study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 8 (17), 1–6. 10.1186/1471-227X-8-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans, C. & Soar, R. (2005). Caring for clients with dual diagnosis in rural communities in Australia: The experience of mental health professionals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12 (3), 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi, C. & Mezzina, R. (2020). Dual diagnosis: A systematic review of the organization of community health services. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66 (3), 300–310. 10.1177/0020764019899975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannopoulos, V. , Morley, K. , Louie, E. et al. (2021). The role of clinical supervision in implementing evidence‐based practise for managing comorbidity. The Clinical Supervisor, 40, 158–177. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, N. , Newton‐Howes, G. , Ford, H. , Williman, J. & Foulds, J. (2018). The prevalence of comorbid alcohol use disorder in the presence of personality disorder: Systematic review and explanatory modelling: Alcohol use disorder prevalence in personality disorder: Systematic review. Personality and Mental Health, 12 (3), 216–228. 10.1002/pmh.1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, G. & Maio, G. R. (2004). Contemporary Perspectives on the Psychology of Attitudes: An Introduction and Overview. Hove: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Happell, B. , Carta, B. & Pinikahana, J. (2002). Nurses' knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding substance use: A questionnaire survey. Nursing and Health Sciences, 4 (4), 193–200. 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2002.00126.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman, M. , Majamäki, M. , Rolando, S. , Bujalski, M. & Lemmens, P. (2015). What causes addiction problems? Environmental, biological and constitutional explanations in press portrayals from four European welfare societies. Substance Use & Misuse, 50 (4), 419–438. 10.3109/10826084.2015.978189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q. N. , Gonzalez‐Reyes, A. & Pluye, P. (2018). Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24 (3), 459–467. 10.1111/jep.12884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, V. & Holmshaw, J. (2010). Inpatient staff perceptions in providing care to individuals with co‐occurring mental health problems and illicit substance use. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17 (10), 862–872. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, G. E. , Large, M. M. , Cleary, M. , Lai, H. M. X. & Saunders, J. B. (2018). Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990–2017: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 234–258. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, G. E. , Malhi, G. S. , Cleary, M. , Man, H. , Lai, X. & Sitharthan, T. (2016). Comorbidity of bipolar and substance use disorders in national surveys of general populations, 1990–2015: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 321–330. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman, K.‐M. , Scala, E. , Nwogwugwu, C. , Huggins, D. & Antoine, D. G. (2020). Nursing attitudes toward patients with substance use disorders: A quantitative analysis of the impact of an educational workshop. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 31 (3), 213–220. 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane‐Llopis, E. & Matytsina, I. (2006). Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: A review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25 (6), 515–536. 10.1080/09595230600944461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, L. & Wiklund‐Gustin, L. (2016). The multifaceted vigilance ‐ nurses' experiences of caring encounters with patients suffering from substance use disorder. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30 (2), 303–311. 10.1111/scs.12244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas, P. W. & Volkow, N. D. (2005). The neural basis of addiction: A pathology of motivation and choice. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162 (8), 1403–1413. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, R. E. F. , Marel, C. & Mills, K. L. (2017). A systematic review of the prevalence of comorbid mental health disorders in people presenting for substance use treatment in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36 (4), 527–539. 10.1111/dar.12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X. , Liu, J. , Pan, Y. , Zeng, X. , Chen, F. & Wu, J. (2020). Prevalence of childhood trauma measured by the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in people with substance use disorder: A meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie, E. , Giannopoulos, V. , Baillie, A. et al. (2018). Translating evidence‐based practice for managing comorbid substance use and mental illness using a multimodal training package. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 14, 111–119. 10.1080/15504263.2018.1437496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie, E. , Giannopoulos, V. , Uribe, G. et al. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the pathways to comorbidity care (PCC) training package for the management of comorbid mental disorders in drug and alcohol settings. Frontiers in Health Services, 12. 10.3389/frhs.2021.785391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie, E. , Morley, K. C. , Giannopoulos, V. et al. (2021). Implementation of a multi‐modal training program for the management of comorbid mental disorders in drug and alcohol settings: Pathways to comorbidity care (PCC). Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 1‐9, 304–312. 10.1080/15504263.2021.1984152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl, M. K. , Olovsson, K. J. , Rönngren, Y. & Norbergh, K. G. (2014). Nurse's perspectives on care provided for patients with gamma‐hydroxybutyric acid and gamma‐butyrolactone abuse. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23 (17–18), 2589–2598. 10.1111/jocn.12475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marel, C. , Mills, K. , Kingston, R. et al. (2016). Guidelines on the Management of Co‐Occurring Alcohol and Other Drug and Mental Health Conditions in Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Settings. Sydney, Australia: Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health and Substance Use, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales. Available from: URL:. https://comorbidity.edu.au/sites/default/files/National [Google Scholar]

- Mark, T. L. (2003). The costs of treating persons with depression and alcoholism compared with depression alone. Psychiatric Services, 54, 1095–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, B. , Thom, K. , Howard, F. & Williams, V. (2010). In search of a national approach to professional supervision for mental health and addiction nurses: The New Zealand experience. Contemporary Nurse, 34 (2), 267–276. 10.5172/conu.2010.34.2.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded Sourcebook, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Medicine, 3 (3), e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina‐Mula, J. , Gonzalez‐Trujillo, A. & Simonet‐Bennassar, M. (2018). Emergency and mental health nurses' perceptions and attitudes towards alcoholics. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 15 (8), 13. 10.3390/ijerph15081733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderup, P. (2016). Training changes professionals' attitudes towards dual diagnosis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15 (1), 53–62. 10.1007/s11469-016-9649-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderup, P. (2018). Improving the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of mental health professionals regarding dual diagnosis treatment ‐ a mixed methods study of an intervention. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39 (4), 292–303. 10.1080/01612840.2017.1398791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J. , Roberts, H. , Sowden, A. et al. (2006). Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme, 1 (1), b92. [Google Scholar]

- Ralley, C. , Allott, R. , Hare, D. J. & Wittkowski, A. (2009). The use of the repertory grid technique to examine staff beliefs about clients with dual diagnosis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16 (2), 148–158. 10.1002/cpp.606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryrie, I. & McGowan, J. (1998). Staff perceptions of substance use among acute psychiatry inpatients. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 5 (2), 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheals, K. , Tombor, I. , McNeill, A. & Shahab, L. (2016). A mixed‐method systematic review and meta‐analysis of mental health professionals' attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction, 111 (9), 1536–1553. 10.1111/add.13387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried, N. , Ferguson, J. , Cleary, M. , Walter, G. & Rey, J. M. (1999). Experience, knowledge and attitudes of mental health staff regarding patients' problematic drug and alcohol use. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 33 (2), 267–273. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. , Chi, F. & Hinman, A. (2011). Integrating care for people with co‐occurring alcohol and other drug, medical, and mental health conditions. Alcohol Research & Health, 33 (4), 338–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson, M. , Slade, T. & Mills, K. (2009). Comorbidity in Australia: Findings of the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43 (7), 606–614. 10.1080/00048670902970908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Flemming, K. , McInnes, E. , Oliver, S. & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12 (1), 181. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel, L. C. , Brouwers, E. P. M. , van Weeghel, J. & Garretsen, H. F. L. (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131 (1), 23–35. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadell, K. & Skrster, I. (2007). Nurses' experiences of caring for patients with a dual diagnosis of depression and alcohol abuse in a general psychiatric setting. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28 (10), 1125–1140. 10.1080/01612840701581230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. M. , Fayter, D. , Mdege, N. , Stirk, L. , Sowden, A. J. & Godfrey, C. (2013). Interventions for alcohol and drug problems in outpatient settings: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32 (4), 356–367. 10.1111/dar.12037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. (1999). Attitudes of mental health professionals to co‐morbidity between mental health problems and substance misuse. Journal of Mental Health, 8 (6), 605–613. 10.1080/09638239917076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, K. , Giannopoulos, V. , Louie, E. et al. (2020). The role of clinical champions in facilitating the use of evidence‐based practice in drug and alcohol and mental health settings: A systematic review. Implementation Science: Research & Practice, 1, 263348952095907. 10.1177/2633489520959072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. , Wong, L. Y. , Grivel, M. M. & Hasin, D. S. (2017). Stigma and substance use disorders: An international phenomenon. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30 (5), 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Search terms using PICO.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.