Abstract

Objectives

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is a common problem of cardiac surgery. Beta-blockers are recognized as effective prophylactic agents available for POAF management. To better understand its effect on isolated atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery, a meta-analysis was conducted.

Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were searched and filtered by comparing the efficacy of beta-blockers and control users in isolated POAF for cardiac surgery. Seventeen RCTs were identified and analyzed by typical meta-analysis methods. The search was performed from inception to May 31, 2020. Subgroup analyses were conducted for type of surgery and beta-blocker, starting time and route of administration of beta-blocker, and dosage of intravenous landiolol hydrochloride.

Results

Beta-blockers were effective in reducing isolated POAF risk (risk ratio [RR], 0.52 [0.41, 0.66], P = .31, I2 = 12%). In subgroup analyses, beta-blocker administration during postoperative period (RR, 0.43 [0.29, 0.62], P = .84, I2 = 0%) and on-pump coronary artery bypass graft (RR, 0.34 [0.04, 3.15], P = .56, I2 = 0%) had lowest risk of isolated POAF incidence. Intravenous landiolol hydrochloride at 2 μg/kg/min also had low risk of isolated POAF occurrence.

Conclusions

Beta-blocker treatment helps to reduce isolated atrial fibrillation incidence after cardiac surgery. Our subgroup analyses also reveal postoperative beta-blocker administration after on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery is most effective in reducing isolated POAF risk. Intravenous landiolol hydrochloride at a dosage of 2 μg/kg/min has also displayed favorable results. Further trials may be required to explore these factors.

Key Words: atrial fibrillation, coronary disease, beta-blocker, meta-analysis, bypass graft

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; b-blocker, beta-blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPG, Clinical Practice Guidelines; IV, intravenous; ONCABG, on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; POAF, postoperative atrial fibrillation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia

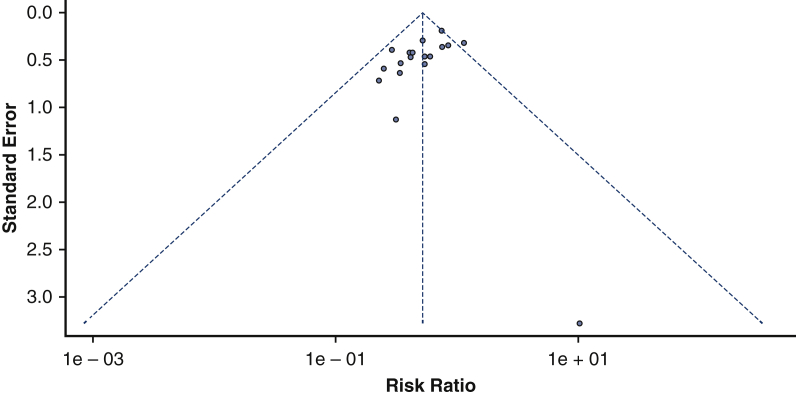

Forest plot of isolated POAF incidence after cardiac surgery.

Central Message.

Beta-blocker treatment reduces incidence of isolated atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery.

Perspective.

We show that beta-blockers reduce risk of isolated atrial fibrillation (AF) after cardiac surgery. Through subgroup analyses, we found that postoperative beta-blocker initiation after coronary artery bypass graft procedures displayed low risk of isolated postoperative AF. IV landiolol hydrochloride at 2 μg/kg/min also presented favorable results. Further trials are required to explore these factors.

See Commentaries on pages 86 and 88.

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is a pertinent problem, causing difficulties in postoperative management by increasing the incidence of complications like postoperative stroke and hospital length of stay.1 Throughout all existing research, beta-blockers (b-blockers) emerge as the prophylactic agent that is universally recognized as a therapy that helps in the reduction of POAF incidence. Current guidelines adopt the use of b-blockers into their standard therapy recommendations for prophylactic action against POAF.2

Despite previous studies focusing on postoperative efficacy of b-blockers, few meta-analyses focus on POAF in isolation because most studies associate POAF with other arrhythmia such as atrial flutter (AFL).3,4 As AFL may occur as isolated arrhythmia, these studies may have conflated the effect of POAF incidence by classifying POAF and AFL together. Moreover, many studies do not explore the effect that factors like surgery, timing, route of administration, and dosing methodology have on the effect of b-blockers on isolated POAF incidence. Hence, we hope that our meta-analysis addresses these issues as we provide an up-to-date review of the benefits of b-blockers in reduction of isolated atrial fibrillation (AF) incidence after cardiac surgery.

Methods

Search Strategy

Our study was performed in strict accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Two authors (Y.M, L.H.D) performed the search, using PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases. The range of dates was standardized from inception to May 31, 2020. The key words used were “beta-blocker, metoprolol, carvedilol, bisoprolol, esmolol, atenolol, acebutolol, propranolol, postoperative atrial fibrillation, cardiac surgery, coronary artery bypass surgery, valve surgery.” A hand search of references from reviews and reference lists was also performed. The most recent or complete study was selected among duplicate studies. Based on the abstract or summary analysis, the online software Rayyan QCRI (Qatar Computing Research Institute [Data Analytics], Doha, Qatar) was then employed to deconflict selected articles in a blinded manner. Conflicts were discussed and the final decision was made by senior author T.K.

Selection Criteria

Trials were filtered through the following inclusion criteria: randomized controlled trial (RCT), report of isolated POAF incidence for treatment and control arms, cardiac surgery, and perioperative initiation of b-blocker treatment. We excluded reviews, case reports, conference abstracts, animal studies, studies that did not segregate outcomes of sotalol and other b-blockers, studies on noncardiac surgeries, studies that did not segregate outcomes of isolated POAF and other supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), and studies on antiarrhythmic agents like amiodarone.

Patients included in the trials were not co-medicated with antiarrhythmic agents like amiodarone during the study. Sotalol was also excluded due to its additional class III antiarrhythmic properties, which would have been an unreliable representation of our results if incorporated in our study.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (Y.M., L.H.D.) independently extracted data from included studies to a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Richmond, Wash) database. Any disagreements at any stage were resolved by consensus with a senior author (T.K.). Preoperative data extracted included the name of first author, publication date of article, country, year, study type, sample size, and baseline characteristics of patients like mean age, percentage of male patients, comorbidities, ejection fraction, and previous b-blocker treatment. Procedural data were also reported and consisted of type of operative procedure, non-study and study drug regimen, target dose indicator, timings, and route of b-blocker administration. In addition, isolated POAF rates in b-blocker and control arms were recorded. Due to study design, we split Sasaki and colleagues5 into 2 substudies. The first study, Sasaki #1, measured outcomes of 1 μg/kg/min of intravenous (IV) landiolol hydrochloride, whereas Sasaki #2 measured outcomes of 2 μg/kg/min of IV landiolol hydrochloride.

The included studies were all RCTs; hence, the Jadad scale was used to assess the risk of bias within each study. The scale was based on the factors of randomization, blinding, and accountability of all patients. The highest attainable score was 5. Studies with a score of 3 or greater were deemed to be of a high quality.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in the R environment through the “metabin” function of “meta” package. The incidence of isolated POAF in control and b-blocker arms were treated as dichotomous variables. A random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled treatment effects as marked study heterogeneity was present. A forest plot was generated, and statistical results of risk ratios (RRs) were displayed at a 95% confidence interval. I2 was considered to quantify statistical heterogeneity. We also conducted subgroup analyses to identify the influences of type of surgery, starting time of b-blocker therapy, route of administration of study b-blocker, type of intervention, and starting dose for IV landiolol hydrochloride. A sensitivity analysis was performed to further explore the study heterogeneity that exists between our included trials. To inspect for the risk of bias across studies, we performed Egger's regression test and generated a funnel plot for publication bias.

Results

Literature Retrieval

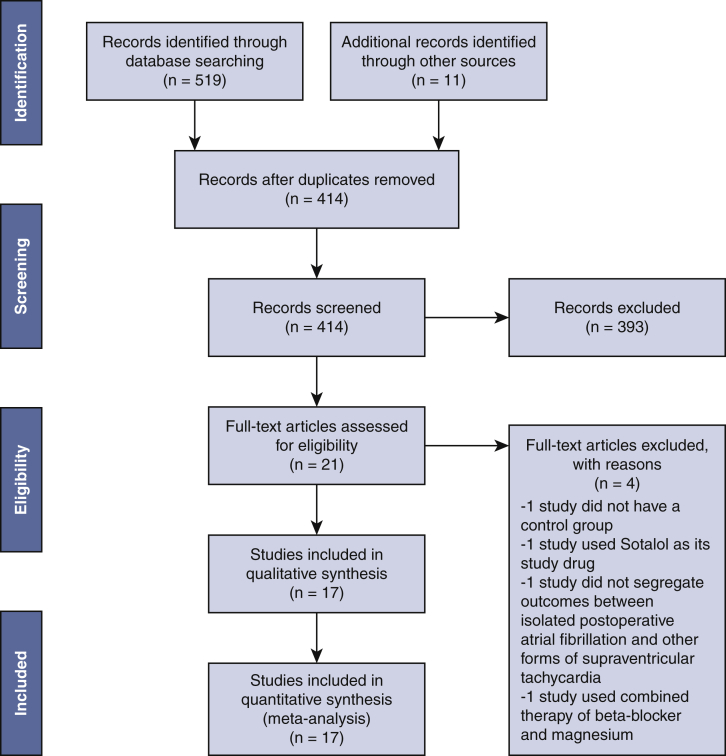

A total of 519 papers were identified from database searches, which were culled to 403 studies after duplicates were filtered. In total, 11 articles were added after manual trawling of references. A total of 414 papers were screened based on their abstracts, with the application of predefined criteria. In all, 393 articles were excluded due to: (1) case reports or conference abstracts; (2) reported outcomes of SVT that did not segregate data for isolated AF; and (3) inclusion of sotalol in its study drug. The final 21 papers were reviewed in full text, and the following were excluded due to the following reasons: 1 study did not have a control group,6 1 study used sotalol as its study drug,7 1 study did not segregate outcomes between isolated AF and other forms of SVT,8 and 1 study focused on the combination therapy of b-blocker and magnesium.9 Eventually, 17 RCTs,5,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 fully satisfying our predefined inclusion criteria, were selected from papers published in varying years. Figure 1 is the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols flow chart of our study as per established 2009 guidelines.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature retrieval. A framework that describes the process of our study selection—519 papers were identified from databases and other sources, 414 studies were screened after duplicate removal, final 21 articles assessed in full text, and 17 RCTs were eventually included in our study.

The included studies were published between 1983 and 2020 and are from 9 different countries (United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Turkey, Austria, Japan, China, Brazil, Australia) (Table 1). Patient enrollment ranged from 24 to 140 patients. All trials focused on isolated POAF for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eleven trials only included patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery,10, 11, 12,14,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 whereas 6 other trials included patients with a variety of surgeries (CABG and valve).5,13,15,23, 24, 25 Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. According to the Jadad scale, overall risk of bias within RCTs was low because all studies scored 3 or more points (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in randomized controlled trials

| First author | Country | Year | Study type | Patients, N | Men, % | Mean age, y | Comorbidity: hypertension, N | Comorbidity: Recent MI, N | Comorbidity: diabetes mellitus, N | Co-morbidity: hyperlipidemia, N | Comorbidity: COPD, N | Ejection fraction, % | Previous b-blocker treatment, N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel et al, 198310 | NJ, USA | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 50 Control: 50 |

B-Blocker: 88 Control: 78 |

B-Blocker: 56.8 ± 1.3 Control: 56.4 ± 1.2 |

NR | B-Blocker: 2 Control: 2 |

NR | NR | NR | B-Blocker: 49 ± 2 Control: 53 ± 2 |

NR |

| Ormerod et al, 198411 | Cambridge, UK | NR | Randomized controlled trial |

B-Blocker: 27 Control: 33 |

B-Blocker: 85.1 Control: 90.9 |

B-Blocker: 54.9 Control: 51.8 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | B-Blocker: ≥40 Control: ≥40 |

NR |

| Rubin et al, 198712 | NY, USA | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 37 Control: 40 |

NR | B-Blocker: 55.0 ± 8.6 Control: 55.8 ± 2 |

B-Blocker: 14 Control: 22 |

NR | B-Blocker: 0 Control: 6 |

NR | NR | B-Blocker: ≥50 Control: ≥50 |

B-Blocker: 28 Control: 29 |

| Cork et al, 199513 | Ariz, New Orleans, La, and Pa, USA; Munich, Germany |

NR | Randomized placebo controlled Trial | B-Blocker: 16 Control: 14 |

B-Blocker: 68.8 Control: 57.1 |

B-Blocker: 60.0 ± 2.7 Control: 63.2 ± 2.1 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | B-Blocker: 51.3 ± 4.9 Control: 57.6 ± 4.0 |

B-Blocker: 6 Control: 1 |

| Yazicioglu et al, 200214 | Ankara, Turkey | March 1999-December 1999 | Randomized placebo controlled trial | B-Blocker: 40 Control: 40 |

B-Blocker: 80 Control: 75 |

B-Blocker: 57.1 ± 7.3 Control: 55.3 ± 8.1 |

B-Blocker: 12 Control: 9 |

B-Blocker: 4 Control: 5 |

NR | NR | NR | B-Blocker: ≥30 Control: ≥30 |

NR |

| Auer et al, 200415 | Wels, Austria | January 2001-May 2002 | Pilot randomized placebo controlled trial | B-Blocker: 62 Control: 65 |

B-Blocker: 59.7 Control: 58.5 |

B-Blocker: 68 ± 9 Control: 63 ± 12 |

B-Blocker: 41 Control: 36 |

B-Blocker: 13 Control: 10 |

B-Blocker: 21 Control: 12 |

NR | NR | B-Blocker: 69 ± 9 Control: 68 ± 8 |

B-Blocker: 24 Control: 22 |

| Imren et al, 200716 | New York, USA Ankara, Turkey |

July 2002-November 2005 | Randomized placebo controlled trial | B-Blocker: 41 Control: 37 |

B-Blocker: 59 Control: 60 |

B-Blocker: 62.2 ± 6.6 Control: 61.4 ± 5.9 |

B-Blocker: 18 Control: 16 |

B-Blocker: 14 Control: 12 |

B-Blocker: 14 Control: 11 |

B-Blocker: 24 Control: 21 |

NR | B-Blocker: 54 ± 12 Control: 52 ± 14 |

NR |

| Sezai et al, 201117 | Tokyo, Japan | NR | Randomized placebo controlled trial | B-Blocker: 70 Control: 70 |

B-Blocker: 88.6 Control: 94.3 |

B-Blocker: 68.5 ± 4.7 Control: 66.7 ± 8.9 |

B-Blocker: 58 Control: 50 |

B-Blocker: 27 Control: 24 |

B-Blocker: 35 Control: 37 |

B-Blocker: 36 Control: 42 |

B-Blocker: 3 Control: 2 |

B-Blocker: 54.5 ± 14.2 Control: 55.6 ± 13.5 |

B-Blocker: 17 Control: 25 |

| Sun et al, 201118 | Nanjing, China | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 30 Control: 28 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Fujii et al, 201219 | Tokyo, Japan | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 36 Control: 34 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sezai et al, 201220 | Tokyo, Japan | NR | Pilot randomized placebo controlled trial | B-Blocker: 34 Control: 34 |

B-Blocker: 76.5 Control: 88.2 |

B-Blocker: 68.5 ± 9.6 Control: 68.2 ± 7.5 |

B-Blocker: 26 Control: 28 |

B-Blocker: 9 Control: 12 |

B-Blocker: 16 Control: 14 |

B-Blocker: 17 Control: 17 |

B-Blocker: 2 Control: 2 |

B-Blocker: 60.4 ± 10.1 Control: 60.0 ± 13.6 |

B-Blocker: 9 Control: 9 |

| Rossi Neto et al, 201321 | Sau Paulo, Brazil | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 35 Control: 33 |

B-Blocker: 68.6 Control: 66.7 |

NR | B-Blocker: 25 Control: 25 |

B-Blocker: 16 Control: 12 |

B-Blocker: 12 Control: 11 |

B-Blocker: 25 Control: 18 |

NR | B-Blocker: 66.3 ± 1.1 Control: 64.0 ± 1.0 |

NR |

| Ogawa et al, 201322 | Toyohashi, Japan | January 2008-May 2010 | Randomized controlled Trial | B-Blocker: 68 Control: 68 |

B-Blocker: 72.1 Control: 82.4 |

B-Blocker: 69.3 ± 6.3 Control: 71.6 ± 7.8 |

B-Blocker: 46 Control: 52 |

B-Blocker: 29 Control: 37 |

B-Blocker: 41 Control: 40 |

NR | NR | B-Blocker: 59.6 ± 11.5 Control: 53.9 ± 11.9 |

B-Blocker: 19 Control: 15 |

| Skiba et al, 201323 | Australia | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 27 Control: 73 |

B-Blocker: 74.1 Control: 82.2 |

B-Blocker: 69 ± 2.2 Control: 63 ± 1.2 |

B-Blocker: 17 Control: 44 |

B-Blocker: 6 Control: 19 |

B-Blocker: 5 Control: 21 |

B-Blocker: 21 Control: 43 |

NR | B-Blocker: >30 Control: >30 |

B-Blocker: 11 Control: 4 |

| Sezai et al, 201524 | Tokyo, Japan | NR | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 30 Control: 30 |

B-Blocker: 86.7 Control: 80 |

B-Blocker: 64.8 ± 9.6 Control: 68.3 ± 9.4 |

B-Blocker: 23 Control: 19 |

NR | B-Blocker: 16 Control: 13 |

B-Blocker: 12 Control: 17 |

B-Blocker: 0 Control: 0 |

B-Blocker: ≤35 Control: ≤35 |

B-Blocker: 12 Control: 16 |

| Liu et al, 201625 | Dalian, China | NR | Pilot randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 12 Control: 12 |

B-Blocker: 66.7 Control: 50 |

B-Blocker: 58.9 ± 9.8 Control: 62.1 ± 7.1 |

B-Blocker: 8 Control: 8 |

NR | B-Blocker: 4 Control: 3 |

NR | NR | B-Blocker: 52.7 ± 6.0 Control: 55.8 ± 3.2 |

B-Blocker: 1 Control: 0 |

| Sasaki #1 et al, 20205 | Tohoku, Japan | April 2010-June 2014 | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 23 Control: 25 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sasaki #2 et al, 20205 | Tohoku, Japan | April 2010-June 2014 | Randomized controlled trial | B-Blocker: 22 Control: 25 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Mean values presented as mean ± standard deviation. MI, Myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NR, not reported; B-Blocker, beta-blocker.

Table 2.

Jadad scale for randomized controlled trials

| First author | Randomization (2 points) | Blinding (2 points) | Account of all patients (1 point) | Total (5 points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel et al, 198310 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Ormerod et al, 198411 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Rubin et al, 198712 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Cork et al, 199513 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Yazicioglu et al, 200214 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Auer et al, 200415 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Imren et al, 200716 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Sezai et al, 201117 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Sun et al, 201118 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Fujii et al, 201219 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Sezai et al, 201220 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Rossi Neto et al, 201321 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Ogawa et al, 201322 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Skiba et al, 201323 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Sezai et al, 201524 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Liu et al, 201625 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Sasaki et al, 20205 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

Characteristics of Studies

Patient characteristics

Among our included studies, a total of 650 patients underwent perioperative b-blocker treatment, whereas 711 patients were in the control arm. Almost all trials included patients with mean ejection fraction ≥30%. Only Sezai and colleagues 2015 included patients with <35% ejection fraction. Sun and colleagues 2011 also focused on patients with rheumatic heart disease. Moreover, comorbidities were found in patients of 12 RCTs.10,12,14, 15, 16, 17,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 We observed that patients with hypertension (n = 288) were the most common in the b-blocker arm, followed by diabetes mellitus (n = 164), hyperlipidemia (n = 135), recent myocardial infarction (n = 120), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (n = 5). With regards to the control arm, patients with hypertension (n = 309) were the most common, followed by diabetes mellitus (n = 168), hyperlipidemia (n = 158), recent myocardial infarction (n = 133), and COPD (n = 4). Patients in all studies were under continuous electrocardiogram monitoring postoperatively. Follow-up period in all trials was confined to a hospital stay.

Procedural characteristics

There were 588 CABG and 78 valve surgeries performed in the b-blocker group. Meanwhile, 625 CABG and 91 valve surgeries were conducted in the control group. We noted that Imren and colleagues and Fujii and colleagues administered a postoperative b-blocker for b-blocker and control arms. In addition, Sezai and colleagues 2015 delivered a postoperative non-study b-blocker for treatment group only. In 16 of 17 studies, patients were b-blocker naïve. Only Auer and colleagues allowed their patients in the treatment group to take non-study b-blockers before and during the trial. Procedural characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Procedural characteristics of patients in randomized controlled trials

| First author | Operative procedure | Non-study drug regimen | Study drug regimen | Target dose indicators | Preoperative B-blocker, timing | Intraoperative B-Blocker, timing | Postoperative B-Blocker, timing | Route of administration for study drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel et al, 198310 | B-Blocker: 50 CABG Control: 50 CABG | NR | B-Blocker: IV propranolol administered preoperatively, and also received 1 mg IV Propranolol at induction of anesthesia and onset of cardiopulmonary bypass; 2 mg IV propranolol continued postoperatively for every 4 h, until able to take oral fluids, and switched to 10 mg oral propranolol every 6 h for 24 h; 20 mg oral propranolol continued for next 4 d; 10 mg oral propranolol continued from 6th postoperative day to discharge Control: IV propranolol therapy was discontinued 6 h preoperatively; no additional IV propranolol was initiated unless indicated by arrhythmias or hypertension |

NR | B-Blocker: IV propranolol, discontinued 6 h preoperatively Control: IV Propranolol, discontinued 6 h preoperatively |

B-Blocker: IV propranolol, at onset of anesthesia and cardiopulmonary bypass |

B-Blocker: IV propranolol, until patient able to take oral fluids Oral propranolol, for 5 d |

IV and oral |

| Ormerod et al, 198411 | B-Blocker: 27 CABG Control: 33 CABG | NR | B-Blocker: oral propranolol (15-30 mg per day) was started on the morning after operation, as soon as patient was able to take oral drugs Control: no specific antiarrhythmic agent |

Dose of oral propranolol was based on weight of patient | – | – | B-Blocker: oral propranolol, morning after operation |

Oral |

| Rubin et al, 198712 | B-Blocker: 37 CABG Control: 40 CABG | NR | B-Blocker: 20 mg oral propranolol every 6 h, starting on postoperative day 1 and continued for approximately 6 wk Control: no drug |

NR | – | – | B-Blocker: oral propranolol, started on postoperative day 1 for 6 wk |

Oral |

| Cork et al, 199513 | B-Blocker: 14 CABG, 3 valve surgery Control: 14 CABG, 1 valve surgery |

All patients received 10 mg of diazepam, 0.1 mg/kg intramuscular morphine, and 0.2-0.3 mg intramuscular scopolamine approximately 60-90 min before operation | B-Blocker: loading Dose of 500 μg/kg/min IV esmolol was given over 4 min just before cannulation of aorta and vena cava; 300 μg/kg/min IV esmolol continued until 10 min after release of aortic crossclamp Control: placebo infusion |

NR | – | B-Blocker: IV esmolol, 4 min before cannulation and continued until 10 min after release of aortic crossclamp |

– | IV |

| Yazicioglu et al, 200214 | B-Blocker: 40 CABG Control: 40 CABG | NR | B-Blocker: single dose of 50 mg oral atenolol started 3 d before operation, dose was halved (25 mg) in 8 patients but none were discontinued Control: placebo |

Single dose of 50 mg oral atenolol maintained at same dose before and after the operation | B-Blocker: oral atenolol, 3 d before |

B-Blocker: oral atenolol, NR | B-Blocker: oral atenolol, NR | Oral |

| Auer et al, 200415 | B-Blocker: 22 valve surgery, 42 CABG Control: 32 valve surgery, 35 CABG |

All drugs previously prescribed to the patient were continued unchanged except for b-blockers, the dose of which was halved on the day of start of study | B-Blocker: 50 mg of oral metoprolol every 12 h Control: matching placebo capsules |

Dose of oral metoprolol was halved if HR dropped to <50 beats per minute, or sustained pacing for bradycardia was required after surgery | B-Blocker: oral metoprolol, 24-48 h before |

B-Blocker: oral metoprolol, NR |

B-Blocker: oral metoprolol, up to 8 d after operation |

Oral |

| Imren et al, 200716 | B-Blocker: 41 OPCABG Control: 37 OPCABG | Intraoperative use of 50-300 μg/kg/min IV esmolol in both groups; postoperative inotropic use of dobutamine and dopamine | B-Blocker: 50 mg of oral metoprolol every 24 h, initiated minimum 4 d before surgery and continued until morning of surgery; 50 mg oral metoprolol initiated 1 d after operation again Control: placebo; 50 mg oral metoprolol initiated 1 d after operation |

IV esmolol: Increase dose gradually toward targeted heart rate (50 beats per minute), up to a maximum of 300 μg/kg/min |

B-Blocker: oral metoprolol, minimum 4 d before |

B-Blocker: IV esmolol, NR Control: IV esmolol, NR |

B-Blocker: oral metoprolol, initiated 1 d after operation till indefinite Control: oral metoprolol, initiated 1 d after operation till indefinite |

Oral |

| Sezai et al, 201117 | B-Blocker: 70 ONCABG Control: 70 ONCABG | NR | B-Blocker: 2 μg/kg/min IV landiolol hydrochloride during operation, discontinued after 48 h Control: physiological saline |

NR | – | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, discontinued after 48 h |

NR | IV |

| Sun et al, 201118 | B-Blocker: 30 CABG Control: 28 CABG | NR | B-Blocker: 2 mg/kg IV esmolol before removal of aortic clamp Control: saline |

NR | – | B-Blocker: IV esmolol, administered before removal of aortic clamp | – | IV |

| Fujii et al, 201219 | B-Blocker: 36 OPCABG Control: 34 OPCABG | 2.5-5 mg/d oral carvedilol was initiated in both groups after extubation and was continued postoperatively | B-Blocker: 5-10 μg/kg/min IV landiolol hydrochloride after operation, until oral drug administration was possible Control: non-IV landiolol hydrochloride |

Adjustment of dose of IV landiolol hydrochloride to control HR at 60-80 beats per minute | – | – | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, up until oral administration was possible oral carvedilol Control: oral carvedilol |

IV |

| Sezai et al, 201220 | B-Blocker: 34 ONCABG Control: 34 ONCABG | NR | B-Blocker: 5 μg/kg/min IV landiolol hydrochloride for 3 d, starting from completion of central anastomosis Control: no B-Blocker; placebo |

NR | – | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, after central anastomosis |

NR | IV |

| Ross Neto et al, 201321 | B-Blocker: 35 CABG Control: 33 CABG | NR | B-Blocker: 200 mg/d oral metoprolol initiated at least 72 h before surgery Control: No B-Blocker |

Dose in 1 patient was reduced to 100 mg/d due to asymptomatic heart rate of less than 50 beats per minute | B-Blocker: oral metoprolol, initiated at least 72 h before surgery |

NR | NR | Oral |

| Ogawa et al, 201322 | B-Blocker: 68 OPCABG Control: 68 OPCABG | Continuous dosing with diltiazem and nitroglycerin was undertaken during the operation | B-Blocker: 3-5 μg/kg/min IV landiolol hydrochloride started immediately after anesthesia induction, continued for 2 d after operation Control: non-IV landiolol hydrochloride |

Adjustment of dose of IV landiolol hydrochloride to control HR at 60-90 beats per minute |

– | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, immediately after anesthesia |

B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, up to 2 d after operation |

IV |

| Skiba et al, 201323 | B-Blocker: 19 CABG alone, 2 valve surgery alone, 4 CABG and valve surgery Control: 54 CABG alone, 5 valve surgery alone, 6 CABG and valve surgery | No patients required inotropes or digoxin before surgery | B-Blocker: up to 4 doses of 5 mg of IV metoprolol were given–in the OT, and within the first 24 h postoperatively; oral metoprolol introduced 24 h postoperatively and continued until follow-up Control: standard therapy (ie, no anti-arrhythmic medication, unless patient was on preoperative B-blocker, in which case it was given postoperatively at same oral dose) |

IV metoprolol: dose was stopped and remainder discarded, if HR dropped below 55 beats per minute, or systolic blood pressure fell to less than 90 mm Hg oral metoprolol: omitted if HR dropped below 55 beats per minute, or systolic blood pressure fell to less than 90 mm Hg |

– | B-Blocker: IV metoprolol, NR | B-Blocker: IV metoprolol, within first 24 h postoperatively oral metoprolol, after first 24 h postoperatively and continued until follow-up |

IV and Oral |

| Sezai et al, 201524 | B-Blocker: 23 CABG alone, 1 CABG and mitral valve replacement, 4 aortic valve replacement alone, 1 mitral valve replacement alone, 1 double valve Replacement alone Control: 23 CABG alone, 1 CABG and aortic valve replacement, 5 aortic valve replacement alone, 1 double valve replacement alone |

Unspecified oral B-blocker for b-Blocker treatment group after surgery | B-Blocker: 2 μg/kg/min IV landiolol hydrochloride at a time of weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass, continued for at least 2 d unspecified oral b-blocker Control: non-IV landiolol hydrochloride |

Once oral b-blocker administered, IV landiolol hydrochloride infusion rate decreased to 1 μg/kg/min | – | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, time of weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, at least 2 d postoperatively Unspecified oral b-blocker, NR |

IV |

| Liu et al, 201625 | B-Blocker: 7 CABG, 5 valve surgery Control: 7 CABG, 5 valve surgery |

Perioperative dosing with diltiazem and nitroglycerin were undertaken | B-Blocker: 70 μg/kg/min IV esmolol during incision, until initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass Control: 0.9% saline |

Dosages of IV esmolol titrated every 2 min to maintain HR within 80% of baseline level | – | B-Blocker: IV esmolol, from incision to initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass | – | IV |

| Sasaki #1 et al, 20205 | B-Blocker: 6 CABG, 17 valve surgery Control: 9 CABG, 16 valve surgery | Administration of oral B-Blockers was prohibited during study period | B-Blocker: 1 μg/kg/min IV landiolol hydrochloride after ICU admission and continued for 4 d Control: non-IV landiolol hydrochloride |

NR | – | – | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, after ICU admission and continued for 4 d Unspecified oral b-blocker |

IV |

| Sasaki #2 et al, 20205 | B-Blocker: 4 CABG, 18 valve surgery Control: 9 CABG, 16 valve surgery | Administration of oral b-blockers was prohibited during study period | B-Blocker: 2 μg/kg/min IV landiolol Hydrochloride after ICU admission and continued for 4 d Control: non-IV landiolol hydrochloride |

NR | – | – | B-Blocker: IV landiolol hydrochloride, after ICU admission and continued for 4 d Unspecified oral B-Blocker |

IV |

B-Blocker, Beta-blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; NR, not reported; IV, intravenous; HR, heart rate; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; ONCABG, on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; OT, operating theater; ICU, intensive care unit.

In all studies, routes of administration for study b-blockers were either through intravenous/IV (n = 9),5,13,17, 18, 19, 20,22,24,25 oral (n = 6),11,12,14, 15, 16,21 or combined (n = 2).10,23 Moreover, starting time of study b-blocker also varied among the trials. A greater number of studies involved intraoperative (n = 9),10,13,17,18,20,22, 23, 24, 25 followed by preoperative (n = 4)14, 15, 16,21 and postoperative initiation (n = 4).5,11,12,19

Starting dose of b-blocker was similarly varied. Among studies with IV administration, dosage ranged from <2 μg/kg/min (n = 1),5 2 μg/kg/min (n = 4),5,17,18,24 >2 μg/kg/min (n = 5),13,19,20,22,25 1 mg (n = 1),10 and <50 mg/d (n = 1).23 In contrast, with regards to oral administration, dosage ranged from <50 mg/d (n = 1),11 50 mg/d (n = 2),14,16 and >50 mg/d (n = 3).12,15,21 Six studies also reported a target dose based on heart rate,15,19,21, 22, 23,25 whereas 1 study based their target dose on patients' weight11 and another guided their dosage on a separate b-blocker.24

Results of Meta-Analysis

Isolated POAF incidence

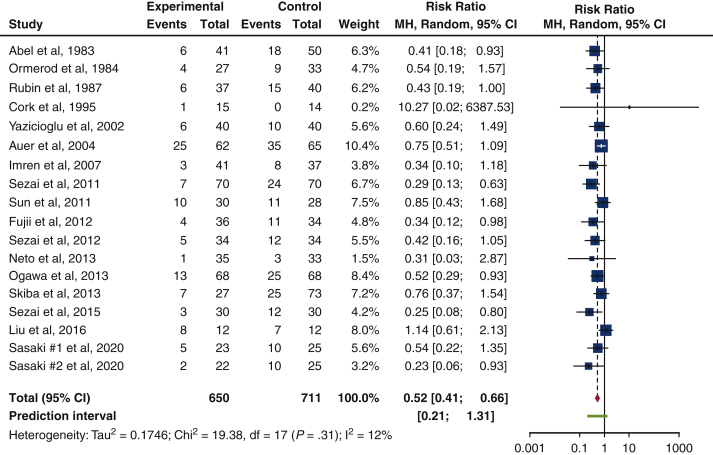

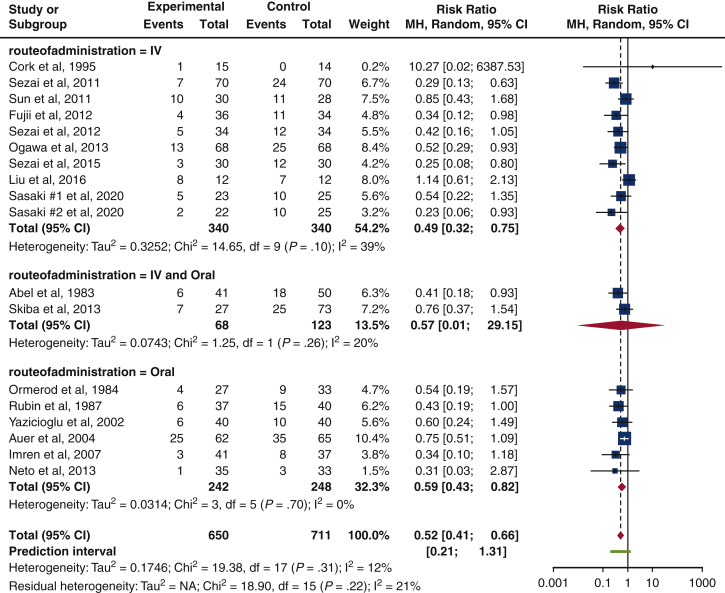

Our study showed that the risk of isolated POAF incidence in 1361 patients was greater among patients in the control arm as compared to the b-blocker arm. This is reflected in the risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.66; I2 = 12%; P = .31). There was acceptable heterogeneity present in the studies (I2 = 12%), but this result trended toward significance (P = .31). Figure 2 displays the results of our study in the form of a forest plot, whereas Table 4 reveals the isolated POAF rate in RCTs.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of isolated POAF incidence after cardiac surgery. A forest plot comparing isolated POAF incidence between b-blocker and control users, in our 17 included trials. Overall risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.66; P = .31) suggests a 48% reduction in risk of isolated POAF in b-blocker users among our 17 included trials. Size of the blue square represents the relative weight of the studies' contributions to the overall risk ratio. MH, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Outcomes of patients in randomized controlled trials

| First author | Patients, N | Definition of POAF | POAF rate, N (%) | Total POAF rate, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel et al, 198310 | B-Blocker: 41 Control: 50 |

POAF Incidence within first 72 h postoperatively, and on 6th postoperative day | B-Blocker: 6/41 (14.6) Control: 18/50 (36) |

Total: 24/91 (26.4) |

| Ormerod et al, 198411 | B-Blocker: 27 Control: 33 |

Prolonged period of irregular atrial tachycardia | B-Blocker: 4/27 (14.8) Control: 9/33 (27.3) |

Total: 13/60 (21.7) |

| Rubin et al, 198712 | B-Blocker: 37 Control: 40 |

Episode lasting more than 30 s | B-Blocker: 6/37 (16.2) Control: 15/40 (37.5) |

Total: 21/77 (27.3) |

| Cork et al, 199513 | B-Blocker: 15 Control: 14 |

NR | B-Blocker: 1/15 (6.7) Control: 0/14 (0) |

Total: 1/29 (3.4) |

| Yazicioglu et al, 200214 | B-Blocker: 40 Control: 40 |

POAF incidence of unspecified duration | B-Blocker: 6/40 (15) Control: 10/40 (25) |

Total: 16/80 (20) |

| Auer et al, 200415 | B-Blocker: 62 Control: 65 |

POAF of >5 min in duration, or for any length of time requiring intervention for angina or hemodynamic compromise | B-Blocker: 25/62 (40.3) Control: 35/65 (53.8) |

Total: 60/127 (47.2) |

| Imren et al, 200716 | B-Blocker: 41 Control: 37 |

Frequency of POAF occurrence from operation time to 6th postoperative day | B-Blocker: 3/41 (7.3) Control: 8/37 (21.6) | Total: 11/78 (14.1) |

| Sezai et al, 201117 | B-Blocker: 70 Control: 70 |

POAF that occurs during the initial 1-week period after surgery | B-Blocker: 7/70 (10) Control: 24/70 (34.2) |

Total: 31/140 (22.1) |

| Sun et al, 201118 | B-Blocker: 30 Control: 28 |

NR | B-Blocker: 10/30 (33.3) Control: 11/28 (39.3) |

Total: 21/58 (36.2) |

| Fujii et al, 201219 | B-Blocker: 36 Control: 34 |

NR | B-Blocker: 4/36 (11.1) Control: 11/34 (32.4) |

Total: 15/70 (21.4) |

| Sezai et al, 201220 | B-Blocker: 34 Control: 34 |

POAF that occurs during the initial 1-week period after surgery | B-Blocker: 5/34 (14.7) Control: 12/34 (35.3) |

Total: 17/68 (25) |

| Rossi Neto et al, 201321 | B-Blocker: 35 Control: 33 |

NR | B-Blocker: 1/35 (2.9) Control: 3/33 (9.1) |

Total: 4/68 (5.9) |

| Ogawa et al, 201322 | B-Blocker: 68 Control: 68 | NR | B-Blocker: 13/68 (19.1) Control: 25/68 (36.8) |

Total: 38/136 (27.9) |

| Skiba et al, 201323 | B-Blocker: 27 Control: 73 |

POAF that occurs up to 6 d postoperatively, and detected by continuous ECG monitoring | B-Blocker: 7/27 (26) Control: 25/73 (34.1) |

Total: 32/100 (32) |

| Sezai et al, 201524 | B-Blocker: 30 Control: 30 |

POAF that occurs during the initial 1-week period after surgery | B-Blocker: 3/30 (10) Control: 12/30 (40) |

Total: 15/60 (25) |

| Liu et al, 201625 | B-Blocker: 12 Control: 12 |

NR | B-Blocker: 8/12 (66.7) Control: 7/12 (58.3) |

Total: 15/24 (62.5) |

| Sasaki #1 et al, 20205 | B-Blocker: 23 Control: 25 |

Continuous atrial fibrillation sustained for more than 5 min | B-Blocker: 5/23 (21.7) Control: 10/25 (40) |

Total: 15/48 (31.3) |

| Sasaki #2 et al, 20205 | B-Blocker: 22 Control: 25 |

Continuous atrial fibrillation sustained for more than 5 min | B-Blocker: 2/22 (9.1) Control: 10/25 (40) |

Total: 12/47 (25.5) |

POAF, Postoperative atrial fibrillation; B-Blocker, beta-blocker; NR, not reported.

Subgroup analyses

Type of surgery

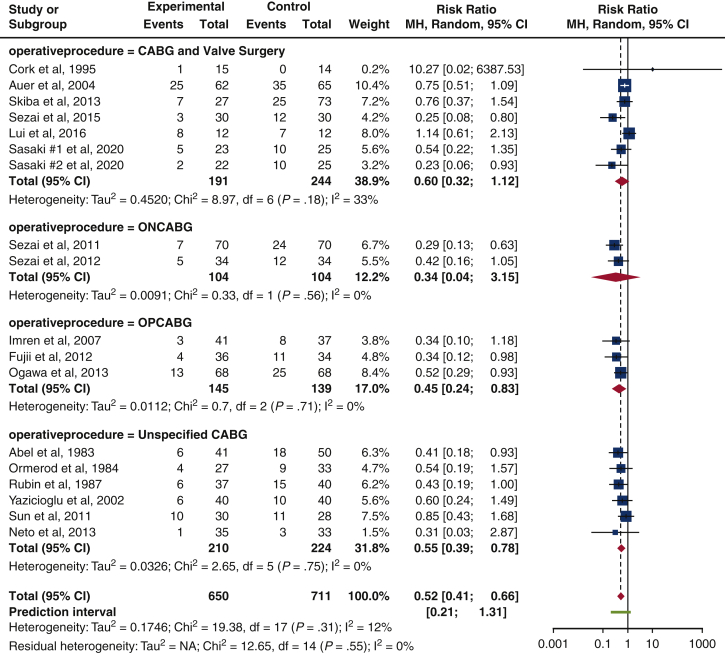

The risk of isolated POAF prevalence was lowest in patients who underwent on-pump CABG (ONCABG) (risk ratio [RR], 0.34 [0.04-3.15], P = .56, I2 = 0%), compared with those who undertook off-pump CABG (OPCABG) (RR, 0.45 [0.24-0.83], P = .71, I2 = 0%), unspecified CABG (RR, 0.55 [0.39-0.78], P = .75, I2 = 0%), and combined CABG and valve surgeries (RR, 0.60 [0.32-1.12], P = .18, I2 = 33%). Results from CABG and combined CABG and valve procedures were acceptable in statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, I2 = 0%, I2 = 0%, and I2 = 33%). However, results were not statistically significant (P = .56, P = .71, P = .75, and P = .18). Only 2 studies provided data for ONCABG17,20 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis on the influence of type of surgery. The forest plot suggests an overall reduction in isolated POAF risk for CABG and valve surgeries, where ONCABG displays the lowest risk ratio (risk ratio, 0.34 [0.04-3.15], P = .56, I2 = 0%). Size of the blue square represents the relative weight of the studies' contributions to the overall risk ratio. MH, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ONCABG, on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting.

Route of administration

The IV route had the lowest risk of isolated POAF occurrence (RR, 0.49 [0.32-0.75], P = .10, I2 = 39%), relative to those initiated through the IV and oral route (RR, 0.57 [0.01-29.15], P = .26, I2 = 20%) and oral route (RR, 0.59 [0.43-0.82], P = .70, I2 = 0%). All results achieved acceptable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 39%, I2 = 20%, I2 = 0%), but none were statistically significant (P = .10, P = .26, P = .70). Only 2 studies used a combined IV and oral administration10,23 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis on the route of b-blocker administration. The forest plot indicates a reduction in isolated POAF risk in all types of b-blocker administration, although the IV route yields the lowest isolated POAF risk. (risk ratio, 0.49 [0.32-0.75], P = .10, I2 = 39%). Size of the blue square represents the relative weight of the studies' contributions to the overall risk ratio. MH, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval; IV, Intravenous.

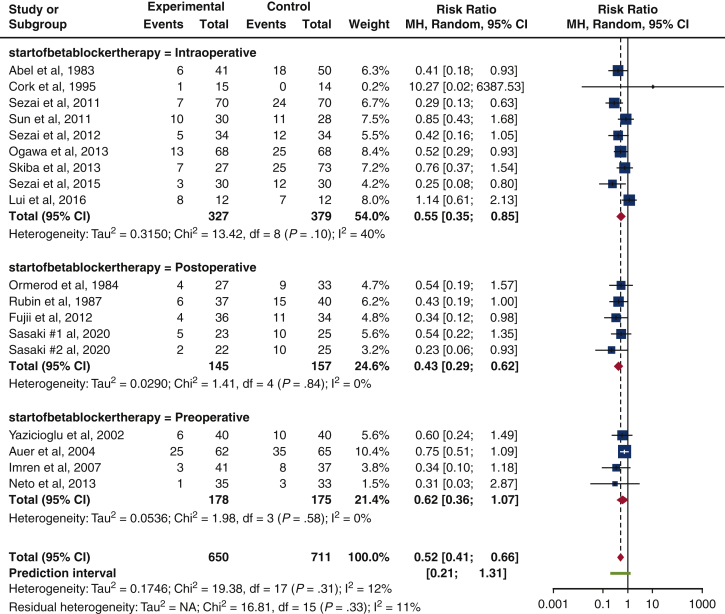

Starting time of beta-blocker administration

The greatest reduction in risk of isolated POAF occurrence was in the postoperative arm (RR, 0.43 [0.29-0.62], P = .84, I2 = 0%), followed by intraoperative (RR, 0.55 [0.35-0.85], P = .10, I2 = 40%), and finally preoperative (RR, 0.62 [0.36-1.07], P = .58, I2 = 0%). All results trended towards significance (P = .84, P = .10, P = .58), while achieving acceptable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, I2 = 40%, I2 = 0%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis on the starting time of b-blocker administration. The forest plot displays an overall reduction in risk of isolated POAF incidence for all timings, but postoperative b-blocker administration is noted to have the lowest risk (risk ratio, 0.43 [0.29-0.62], P = .84, I2 = 0%). Size of the blue square represents the relative weight of the studies' contributions to the overall risk ratio. MH, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval.

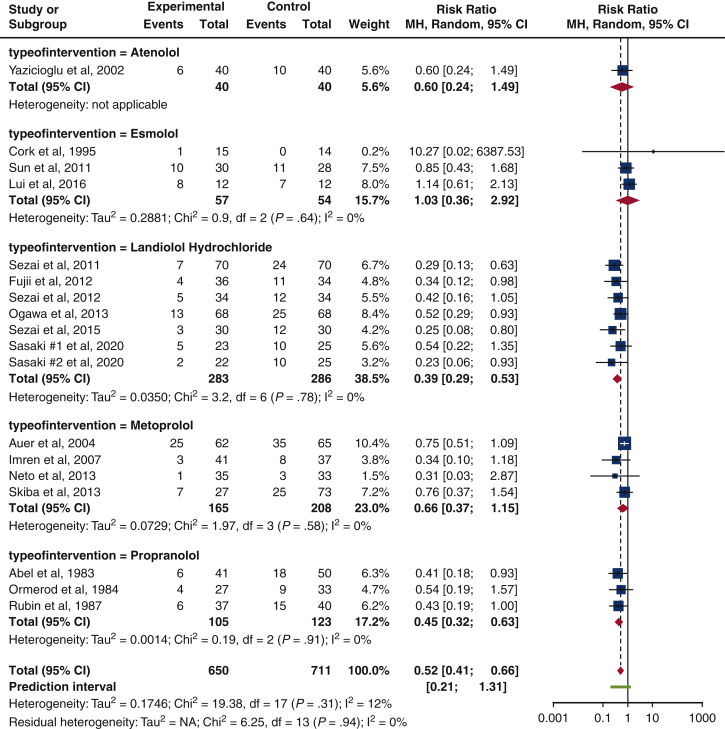

Type of beta-blocker

Landiolol hydrochloride achieved the greatest reduction in risk of isolated POAF incidence (RR, 0.39 [0.29-0.53], P = .78, I2 = 0%), followed by propranolol (RR, 0.45 [0.32-0.63], P = .91, I2 = 0%) and atenolol (RR, 0.60 [0.24-1.49], not applicable). In contrast, esmolol increased the risk of isolated POAF incidence (RR, 1.03 [0.36, 2.92], P = .64, I2 = 0%). All results achieved a statistical homogeneity (I2 = 0%), but they were not statistically significant (P = .78, P = .91, P = .64). Only 1 study used atenolol as its study b-blocker14 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis on the type of b-blocker. The forest plot shows a reduction in risk of isolated POAF incidence for atenolol, landiolol hydrochloride, metoprolol, and propranolol. In contrast, esmolol is found to have an increase in isolated POAF risk (risk ratio, 1.03 [0.36-2.92], P = .64, I2 = 0%). Size of the blue square represents the relative weight of the studies' contributions to the overall risk ratio. MH, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval.

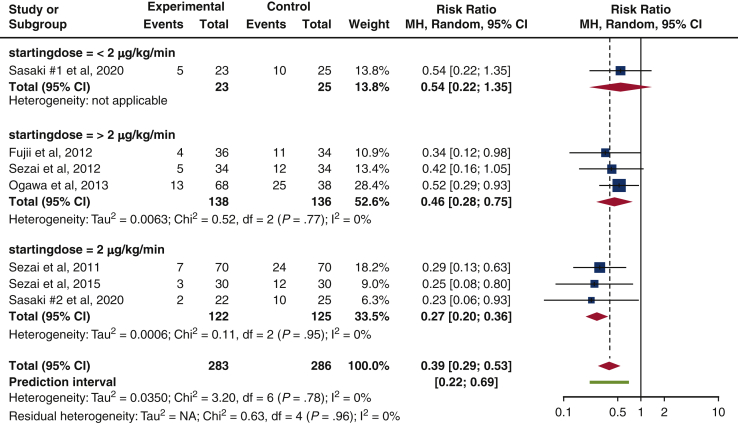

Starting dosage for landiolol hydrochloride

Among studies that administered IV landiolol hydrochloride, starting dose of 2 μg/kg/min had lowest risk of isolated POAF incidence (RR, 0.27 [0.20-0.36], P = .95, I2 = 0%), compared with >2 μg/kg/min (RR, 0.46 [0.28-0.75], P = .77, I2 = 0%) and <2 μg/kg/min (RR, 0.54 [0.22-1.35], not applicable). Results achieved a statistical homogeneity (I2 = 0%), but they were not statistically significant (P = .95, P = .77). Only 1 study recorded a starting dose of <2 μg/kg/min5 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis on dosage for IV landiolol hydrochloride. The forest plot depicts a reduction in isolated POAF risk for all dosages of IV landiolol hydrochloride, and the greatest reduction in risk is found from a dose of 2 μg/kg/min (risk ratio, 0.27 [0.20-0.36], P = .95, I2 = 0%). Size of the blue square represents the relative weight of the studies' contributions to the overall risk ratio. MH, Mantel–Haenszel; CI, confidence interval.

Sensitivity analyses

Studies that used standard care instead of placebo in their control arms were excluded.5,10, 11, 12,18,19,21, 22, 23, 24, 25 We also excluded studies with relatively different methodology: Sezai and colleagues 2015 and Sun colleagues due to their study populations, as well as Imren and colleagues and Fujii and colleagues for the administration of postoperative b-blocker in both arms. Results remained consistent and did not alter our interpretation on the benefits of b-blocker on isolated POAF incidence.

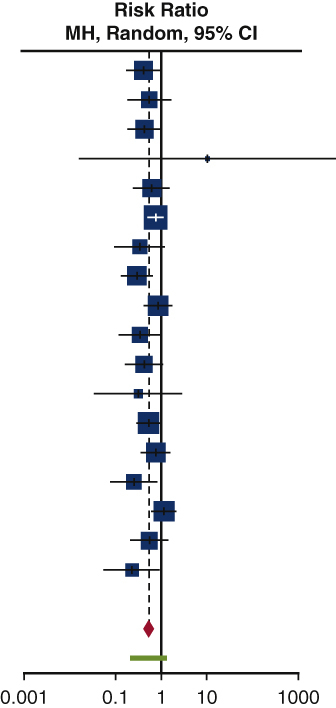

Risk of bias across studies

Our funnel plot reveals no evidence of asymmetry and suggests the absence of publication bias (see Figure 8). This is supported by results from Egger's regression test (P = .06191).

Figure 8.

Funnel plot of publication bias. Our funnel plot of publication bias did not have any signs of asymmetry and hence, did not indicate any publication bias across our included studies.

Discussion

Although there are numerous meta-analyses that focus on b-blockers and their effect on POAF incidence, none have segregated POAF from other forms of SVT, such as AFL. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that achieves this aim.

It is clinically relevant to investigate isolated POAF, as this provides a more reliable representation of the effect of b-blockers and POAF incidence. Although existing literature indicate a close inter-relationship between AF and AFL,26 AFL may also arise in isolation, displaying how certain studies may have conflated the effect of POAF incidence by grouping AF and other arrhythmias together. Moreover, patients with increased risks of isolated AFL were found to have a similar profile for those with POAF. Clinical risk factors include diabetes mellitus, previous heart failure, COPD, age, male sex, and atrial size abnormalities like cardiomyopathy.27 Fatemi and colleagues28 also elucidated a key finding that among CABG and valve procedures, isolated postoperative AFL was more prevalent than isolated POAF. This demonstrated an increase in risk of isolated AFL among POAF patients. Hence, it is important to consider the source of AFL and differentiate isolated AFL from AFL which is caused by AF. Although most studies do not report the source of AFL, we decided not to include any studies that grouped AFL with POAF in order to separate the factors, which would provide more reliable results on the effect of b-blockers on POAF incidence.

Our study shows that there is a greater reduction in isolated POAF risk for patients in the b-blocker arm (albeit not statistically significant), as compared with those in the control arm. This result is not unexpected, as b-blockers are known to effectively maintain sinus rhythm and control ventricular rate through its anti-arrhythmic effects. However, through our subgroup analyses, we identify other factors that influence isolated POAF rate as well.

In our study, CABG procedures (OPCABG/ONCABG/unspecified) are observed to yield a lower risk of isolated POAF incidence than combined CABG and valve procedures. This corroborates with Patel and colleagues,29 which reports a POAF rate of 25% to 40% for CABG, and 50% to 60% for valve surgeries. In a follow-up comparison between OPCABG and ONCABG surgeries, we observed a trend that ONCABG procedures had lower risk of POAF prevalence. Similar results were noted in Lewicki and colleagues,30 which concludes with no significant difference in POAF rates between ONCABG and OPCABG procedures (18.3% vs 19.3%). In contrast, Athanasiou and colleagues31 outlines a statistically significant advantage that OPCABG has over ONCABG in reducing POAF risk (odds ratio, 0.60 [0.45-0.82], P = .05). This was attributed to the avoidance of atrial cannulation and cardioplegia in OPCABG, which results in reduced atrial dilatation and eventually reduced AF. In view of the contrasting results, more trials are needed for our ONCABG analysis to support current views that ONCABG may be the gold standard in contemporary cardiac surgical practice.32

Through a subgroup analysis on starting time of b-blocker administration, we found that postoperative initiation of b-blocker therapy trended toward having the least risk of isolated POAF incidence, followed by intraoperative and preoperative b-blocker administration. The relatively greater risk in patients with preoperative b-blocker initiation could be attributed to a rebound phenomenon, where these patients discontinued the use of b-blockers after surgery. It is thus recommended that patients who started b-blocker preoperatively should continue their medication after surgery, as supported in the 2017 European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs).33 Moreover, our favorable results on postoperative b-blocker initiation is similarly found in the current Cochrane Review.4 A recent retrospective cohort study further explored timings within the postoperative period itself and compared outcomes between b-blocker administration before and after postoperative day 5.34 Given the current evidence, more trials should be conducted to explore the benefits of postoperative b-blocker administration. An update into American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) CPGs could also be reviewed, as current recommendations only include preoperative b-blocker administration for CABG procedures only.2

Moreover, through a subgroup analysis on type of b-blocker used, landiolol hydrochloride trended toward having the lowest risk of isolated POAF incidence among the 5 b-blockers. Propranolol was next, followed by metoprolol, atenolol, and esmolol. These results are supported by the current Cochrane Review,4 which also displayed landiolol hydrochloride with a lower risk of POAF occurrence compared to metoprolol and esmolol. However, in contrast to our study, Atenolol was reported to have the lowest risk ratio (RR, 0.30 [0.05-1.90]) instead. In view of our results, there was only 1 study14 that focused on atenolol and hence, there should be further trials conducted on atenolol before any conclusions can be made. In contrast, esmolol was found to increase the risk for isolated POAF incidence. Numerous early trials on esmolol have also been terminated because of its failed ability to reduce POAF. Esmolol thus should be approached with caution.

A follow-up examination into the route of b-blocker administration corresponds with our favorable results on IV landiolol hydrochloride creating the least risk of POAF incidence. However, current ACC/AHA guidelines do not include the use of landiolol hydrochloride and recommend the use of metoprolol and esmolol.2 The contradictions with proposed ACC/AHA guidelines should be explored further to provide an up-to-date review on perioperative care for cardiac surgery patients. Given the positive results of landiolol hydrochloride in reducing POAF incidence, there should be more trials/studies conducted to explore its beneficial impact.

To evaluate the benefit of landiolol hydrochloride on POAF rate, we investigated the optimal starting dose for landiolol hydrochloride. We found the starting dose of 2 μg/kg/min to be optimal in reducing isolated POAF risk, albeit not statistically significant. Although the recommended landiolol hydrochloride dosage is not stipulated in the ACC/AHA CPGs, it is found to be consistent with other studies.35 More trials in follow-up studies are needed for further discussion.

The findings of this study need to be interpreted in the context of known limitations. First, through the inclusion of b-blockers in control arms, results may be affected in Imren and colleagues and Fujii and colleagues. Sezai 2015 and colleagues also used a non-study b-blocker postoperatively. These studies were still included, as Imren and colleagues and Fujii and colleagues standardized the b-blocker use in both arms, whereas Sezai 2015 and colleagues did not specify the duration of non-study b-blocker administration. A sensitivity analysis did not reveal a change in consistency of results. Second, Sezai 2015 and colleagues included patients with <35% ejection fraction and Sun and colleagues focused on patients with rheumatic heart disease. This may introduce unreliable results because POAF is likely to happen at a relatively higher rate in these trials. However, a sensitivity analysis also did not show any change in results. Lastly, only Auer and colleagues allowed patients to take non-study b-blockers before and during the trial. This could have led to an overestimation on the efficacy of b-blockers. By discontinuing background b-blocker treatment, POAF incidence could have increased due to b-blocker withdrawal phenomena. We hope that future trials take this into account and give more details to their dosing methodology.

Conclusions

Our study shows that perioperative b-blocker reduces risk of isolated POAF incidence after cardiac surgery. Through subgroup analyses, we find that postoperative b-blocker administration after ONCABG surgery is most effective in reducing isolated POAF risk. IV landiolol hydrochloride at a dosage of 2 μg/kg/min has also displayed favorable results. Further trials may be required to explore these factors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Villareal R.P., Hariharan R., Liu B.C., Kar B., Lee V.V., Elayda M., et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation and mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January C.T., Wann L.S., Alpert J.S., Calkins H., Cigarroa J.E., Cleveland J.C., Jr., et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e1–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crystal E., Connolly S.J., Sleik K., Ginger T.J., Yusuf S. Interventions on prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2002;106:75–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000021113.44111.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blessberger H., Lewis S.R., Pritchard M.W., Fawcett L.J., Domanovits H., Schlager O., et al. Perioperative beta-blockers for preventing surgery-related mortality and morbidity in adults undergoing cardiac surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD013435. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki K., Kumagai K., Maeda K., Akiyama M., Ito K., Matsuo S., et al. Preventive effect of low-dose landiolol on postoperative atrial fibrillation study (PELTA study) Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. May 5, 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11748-020-01364-9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osmanovic E., Ostojic M., Avdic S., Djedovic S., Delic A., Kadric N., et al. Pharmacological prophylaxis of atrial fibrillation after surgical myocardial revascularization. Med Arch. 2019;73:19–22. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2019.73.19-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forlani S., De Paulis R., de Notaris S., Nardi P., Tomai F., Proietti I., et al. Combination of sotalol and magnesium prevents atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:720–725. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03773-6. discussion 725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly S.J., Cybulsky I., Lamy A., Roberts R.S., O'Brien B., Carroll S., et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of prophylactic metoprolol for reduction of hospital length of stay after heart surgery: the beta-blocker length of stay (BLOS) study. Am Heart J. 2003;145:226–232. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behmanesh S., Tossios P., Homedan H., Hekmat K., Hellmich M., Müller-Ehmsen J., et al. Effect of prophylactic bisoprolol plus magnesium on the incidence of atrial fibrillation after coronary bypass surgery: results of a randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1443–1450. doi: 10.1185/030079906X115649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abel R.M., van Gelder H.M., Pores I.H., Liguori J., Gielchinsky I., Parsonnet V. Continued propranolol administration following coronary bypass surgery. Antiarrhythmic effects. Arch Surg. 1983;118:727–731. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390060045010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ormerod O.J., McGregor C.G., Stone D.L., Wisbey C., Petch M.C. Arrhythmias after coronary bypass surgery. Br Heart J. 1984;51:618–621. doi: 10.1136/hrt.51.6.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin D.A., Nieminski K.E., Reed G.E., Herman M.V. Predictors, prevention, and long-term prognosis of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cork R.C., Kramer T.H., Dreischmeier B., Behr S., DiNardo J.A. The effect of esmolol given during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:28–40. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazicioglu L., Eryilmaz S., Sirlak M., Inan M.B., Aral A., Tasoz R., et al. The effect of preoperative digitalis and atenolol combination on postoperative atrial fibrillation incidence. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:397–401. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auer J., Weber T., Berent R., Puschmann R., Hartl P., Ng C.K., et al. A comparison between oral antiarrhythmic drugs in the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: the pilot study of prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation (SPPAF), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2004;147:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imren Y., Benson A.A., Zor H., Tasoglu I., Ereren E., Sinci V., et al. Preoperative beta-blocker use reduces atrial fibrillation in off-pump coronary bypass surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sezai A., Minami K., Nakai T., Hata M., Yoshitake I., Wakui S., et al. Landiolol hydrochloride for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: new evidence from the PASCAL trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1478–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun J., Ding Z., Qian Y. Effect of short-acting beta blocker on the cardiac recovery after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:99. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujii M., Bessho R., Ochi M., Shimizu K., Terajima K., Takeda S. Effect of postoperative landiolol administration for atrial fibrillation after off pump coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2012;53:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sezai A., Nakai T., Hata M., Yoshitake I., Shiono M., Kunimoto S., et al. Feasibility of landiolol and bisoprolol for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: a pilot study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossi Neto J.M., Gun C., Ramos R.F., Almeida A.F., Issa M., Amato V.L., et al. Myocardial protection with prophylactic oral metoprolol during coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: evaluation by troponin I. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2013;28:449–454. doi: 10.5935/1678-9741.20130074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogawa S., Okawa Y., Goto Y., Aoki M., Baba H. Perioperative use of a beta blocker in coronary artery bypass grafting. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2013;21:265–269. doi: 10.1177/0218492312451166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skiba M.A., Pick A.W., Chaudhuri K., Bailey M., Krum H., Kwa L.J., et al. Prophylaxis against atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: beneficial effect of perioperative metoprolol. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sezai A., Osaka S., Yaoita H., Ishii Y., Arimoto M., Hata H., et al. Safety and efficacy of landiolol hydrochloride for prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery with landiolol hydrochloride for left ventricular dysfunction (PLATON) trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X., Shao F., Yang L., Jia Y. A pilot study of perioperative esmolol for myocardial protection during on-pump cardiac surgery. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:2990–2996. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldo A.L. More musing about the inter-relationships of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter and their clinical implications. Circulation. 2013;6:453–454. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granada J., Uribe W., Chyou P.H., Maassen K., Vierkant R., Smith P.N., et al. Incidence and predictors of atrial flutter in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2242–2246. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00982-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fatemi M., Leledy M., Le Gal G., Bezon E., Mondine P., Blanc J.J. Atrial flutter after non-congenital cardiac surgery: incidence, predictors and outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2011;153:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel D., Gillinov M.A., Natale A. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: where are we now? Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2008;8:281–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewicki L., Siebert J., Rogowski J. Atrial fibrillation following off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: incidence and risk factors. Cardiol J. 2016;23:518–523. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2016.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Athanasiou T., Aziz O., Mangoush O., Al-Ruzzeh S., Nair S., Malinovski V., et al. Does off-pump coronary artery bypass reduce the incidence of post-operative atrial fibrillation? A question revisited. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams D.H., Chikwe J. On-pump CABG in 2018. Still the gold standard. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:992–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sousa-Uva M., Head S.J., Milojevic M., Collet J.P., Landoni G., Castella M., et al. 2017 EACTS guidelines on perioperative medication in adult cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53:5–33. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chanan E, Cuff G, Kendale S, Galloway A, Nunnally M. Adverse Outcomes Associated with Absent or Delayed B-Blocker Administration after Cardiac Surgery. Presented at: International Anesthesia Research Society 2019 Annual Meeting; 2019; Montreal, Canada.

- 35.Shibata S.C., Uchiyama A., Ohta N., Fujino Y. Efficacy and safety of landiolol compared to amiodarone for the management of postoperative atrial fibrillation in intensive care patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30:418–422. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.