Abstract

Study Objectives:

To examine children with Down syndrome with residual obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) to determine if they are more likely to have positional OSA.

Methods:

A retrospective chart review of children with Down syndrome who underwent adenotonsillectomy at a single tertiary children’s hospital was conducted. Children with Down syndrome who had a postoperative polysomnogram with obstructive apnea-hypopnea index (OAHI) > 1 event/h, following adenotonsillectomy with at least 60 minutes of total sleep time were included. Patients were categorized as mixed sleep (presence of ≥ 30 minutes of both nonsupine and supine sleep), nonsupine sleep, and supine sleep. Positional OSA was defined as an overall OAHI > 1 event/h and a supine OAHI to nonsupine OAHI ratio of ≥ 2. Group differences are tested via Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical.

Results:

There were 165 children with Down syndrome who met inclusion criteria, of which 130 individuals had mixed sleep. Patients who predominately slept supine had a greater OAHI than mixed and nonsupine sleep (P = .002). Sixty (46%) of the mixed-sleep individuals had positional OSA, of which 29 (48%) had moderate/severe OSA. Sleeping off their backs converted 14 (48%) of these 29 children from moderate/severe OSA to mild OSA.

Conclusions:

Sleep physicians and otolaryngologists should be cognizant that the OAHI may be an underestimate if it does not include supine sleep. Positional therapy is a potential treatment option for children with residual OSA following adenotonsillectomy and warrants further investigation.

Citation:

Lackey TG, Tholen K, Pickett K, Friedman N. Residual OSA in Down syndrome: does body position matter? J Clin Sleep Med. 2023;19(1):171–177.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, sleep position, positional obstructive sleep apnea, child, Down syndrome, trisomy 21, tonsillectomy, polysomnogram, sleep study, persistent obstructive sleep apnea

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Residual obstructive sleep apnea is common in children with Down syndrome following first-line adenotonsillectomy. Continuous positive airway pressure compliance is suboptimal. For adults, positional therapy is a treatment option.

Study Impact: Children with Down syndrome and refractory obstructive sleep apnea following adenotonsillectomy have more severe obstruction in the supine position. Positional therapy is a potential treatment option. Results from this study support further investigation of positional therapy in children following unsuccessful surgery.

INTRODUCTION

In contrast to otherwise healthy nonsyndromic children, 50–70% of children with Down syndrome (DS) are diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1–6 The increased risk and prevalence in this population is due to several clinical characteristics including hypotonia, weight, an underdeveloped midface with relative macroglossia, and lymphoid hyperplasia.7–9 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a sleep study, or polysomnogram (PSG), by age 4 years in children with DS. First-line therapy in children with OSA is tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy (T&A), as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical guideline.10 The International Classification of Sleep Disorders defines cure as an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) < 1 event/h.11 For children with DS, cure (AHI < 1 event/h) ranges from 12 to 37%.12–14 In the childhood adenotonsillectomy study which investigated nonsyndromic children, the OSA cure rate was 80% following a T&A. Cure was defined as an AHI < 2 events/h and the obstructive apnea index < 1.15

Children with residual OSA after T&A are often referred for continuous positive airway pressure. Unfortunately, adherence to continuous positive airway pressure is low in the pediatric population.16,17 Alternative to positive pressure ventilation include weight loss, intranasal corticosteroids, leukotriene modifier therapy, rapid maxillary expansion, and various surgeries including but not limited to lingual tonsillectomy, base of tongue reduction, supraglottoplasty, mandibular distraction osteogenesis, and tracheostomy.18 Another potential treatment option is positional therapy, which aims to keep patients in the nonsupine position to alleviate OSA that occurs in the supine position.19–21 Severity of OSA by body position has been increasingly recognized, with children often having more respiratory events in the supine position,20,22–26 though some studies have found no difference.27–29 Positional OSA (POSA) is characterized by an obstructive apnea-hypopnea index (OAHI) that is at least twice as high in the supine position compared to the nonsupine position.30 POSA is present in approximately 19% of children,19 which increases to 48–58% in obese children21,31 and 32% following T&A.19 Specifically, in children with DS, 22–33% have POSA; however, these studies contained a small heterogenous group of patients with and without prior upper airway surgery.19,32

Residual OSA following a T&A is common in children with DS, yet identifying targets for therapy remains elusive. Recent evidence suggests sleep positional therapy attenuates obstructive sleep disturbance. Our primary objective was to examine children with DS with residual OSA to determine if they are more likely to have POSA.

METHODS

The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this research study.

Study participants

Children with DS who underwent T&A from 2009 to 2015 for OSA at Children’s Hospital of Colorado were identified retrospectively through an electronic medical record search as reanalysis of previous cohort published by Ingram et al.12 Inclusion criteria were DS, PSG following T&A, residual OSA (OAHI > 1 event/h), and at least 60 minutes of total sleep time on PSG. Patients were excluded if they had surgery that included supraglottoplasty, lingual tonsillectomy, or base of tongue reduction. There were three sleep position groups: mixed sleep (presence of at least 30 minutes of both supine and nonsupine sleep), nonsupine sleep (< 30 minutes of supine sleep), and supine sleep (< 30 minutes of nonsupine sleep). Initial descriptive analysis included all those with > 60 minutes of sleep, but only patients with mixed sleep were further categorized into POSA and non-POSA; POSA was defined as an overall OAHI ≥ 1 event/h and a supine OAHI to nonsupine OAHI ratio of ≥ 2. Patients were further categorized based on OAHI into four groups: no OSA (< 1 event/h), mild (≥ 1 to < 5 events/h), moderate (≥ 5 to < 10 events/h), and severe (≥ 10 events/h). Individual charts were reviewed to confirm inclusion criteria.

Measures

For each patient, the following demographic information was recorded: age, sex, ethnicity, date of surgery, indication for surgery, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) percentile. The BMI percentile for age/sex was calculated per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. BMI percentile categories were defined as underweight (< 5%), healthy weight (≥ 5% and < 85%), overweight (≥ 85% and < 95%), and obesity (≥ 95%). PSG metrics collected included mean oxygen saturation (SpO2), SpO2 nadir, total sleep time, sleep time in the different stages and position of sleep, and OAHI overall and by different stages and position of sleep. Sleep position was defined by supine and nonsupine (prone and lateral combined). Details of time spent in nonrapid eye movement, rapid eye movement (REM), supine, and nonsupine sleep were examined with at least 30 minutes spent in each position for all patients. PSGs were scored using the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines.33,34 Data were absent in a limited random number of categories and patients. All data were stored in a secure REDCap database.

Data analysis

Demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics, summarized for continuous variables with medians and interquartile ranges or mean (standard deviation), and for categorical variables with frequencies and proportions. Group differences were tested via t test or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables dependent on distribution and chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables dependent on cell size. Logistic regression for POSA was performed considering the variables age, BMI percentile, and percent of REM sleep minutes. All hypothesis testing was done at alpha 0.05. All summaries and analysis were done using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Between 2009 and 2015, 278 children underwent a T&A and underwent a PSG postoperatively. Of those, 165 patients met the inclusion criteria with 130 (79%) meeting the criteria for mixed sleep. Twenty-one (13%) had predominantly nonsupine sleep and 14 (8%) had supine sleep. Supine sleep had a higher postoperative median OAHI (P < .05; Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of sleep categories.

| Mixed (n = 130) | Predominantly Nonsupine (n = 21) | Predominantly Supine (n = 14) | Total (n = 165) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at postsurgery PSG, y* | 5.61 (3.19, 8.94) | 6.52 (5.62, 8.84) | 10.76 (5.94, 15.76) | 6.29 (3.40, 9.25) | .003 |

| BMI% category | .86 | ||||

| Under | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Healthy/under | 57 (48.3%) | 10 (47.6%) | 6 (46.2%) | 73 (48.0%) | |

| Overweight | 29 (24.6%) | 6 (28.6%) | 4 (30.8%) | 39 (25.7%) | |

| Obese | 31 (26.3%) | 5 (23.8%) | 3 (23.1%) | 39 (25.7%) | |

| BMI percentile for age** | 86 (68, 96) | 86 (67, 95) | 90 (51, 93) | 86 (67, 95) | .93 |

| Total sleep time, mean (SD) | 397.40 (78.66) | 348.91 (105.86) | 313.02 (152.70) | 384.07 (93.87) | <.001 |

| Stage REM (% sleep time) | 16.65 (11.40, 20.40) | 12.20 (4.70, 20.10) | 10.65 (5.65, 14.78) | 15.60 (10.00, 20.40) | .046 |

| Stage N1 (% sleep time) | 6.40 (3.00, 11.10) | 5.00 (3.00, 9.80) | 7.20 (3.97, 14.40) | 6.10 (3.00, 11.03) | .49 |

| Stage N2 (% sleep time) | 49.80 (42.50, 56.00) | 52.40 (45.00, 56.40) | 47.85 (39.58, 61.20) | 49.95 (42.08, 56.58) | .89 |

| Stage N3 (% sleep time) | 24.10 (19.60, 30.10) | 27.70 (19.80, 33.30) | 22.75 (14.57, 28.72) | 24.35 (19.45, 30.70) | .34 |

| NREM OAHI | 4.25 (2.25, 8.60) | 2.10 (1.20, 2.80) | 6.80 (3.20, 16.38) | 4.00 (1.90, 8.60) | .003 |

| REM OAHI | 12.40 (4.65, 24.83) | 9.25 (2.62, 14.45) | 29.00 (19.00, 60.85) | 12.20 (4.55, 25.40) | .006 |

| OAHI | 5.75 (2.90, 10.65) | 2.70 (1.50, 5.10) | 14.25 (4.90, 22.10) | 5.30 (2.70, 10.70) | .002 |

| Degree OSA | .02 | ||||

| Mild (1 –< 5) | 56 (43.1%) | 15 (71.4%) | 4 (28.6%) | 75 (45.5%) | |

| Moderate (5–< 10) | 38 (29.2%) | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (14.3%) | 43 (26.1%) | |

| Severe (10+) | 36 (27.7%) | 3 (14.3%) | 8 (57.1%) | 47 (28.5%) |

*Continuous variables are reported as median (interquartile ranges) unless otherwise noted. **Data were absent in a limited number of categories and patients. Time reported in minutes. BMI = body mass index, NREM = nonrapid eye movement, OAHI = obstructive apnea-hypopnea index, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, PSG = polysomnogram, REM = rapid eye movement, SD = standard deviation.

The mixed-sleep cohort had median age of 5.61 years (interquartile ranges: 3.19, 8.94) with median BMI percentile of 86 (interquartile ranges: 68, 96). Sixty (46%) met the criteria for POSA. Age at time of PSG, ethnicity and BMI percentile were similar between POSA and non-POSA patients. Female patients were more likely to have POSA (P < .05; Table 2). Table 3 provides details of the time spent in each sleep stage and body position. Mean SpO2 and SpO2 nadir were similar between the two groups. Median OAHI was greater in the non-POSA cohort (7.75 v 4.75, P < .05; Table 3).

Table 2.

Demographics of analytic cohort by presence of POSA.

| Non-POSA (n = 70) | POSA (n = 60) | Total (n = 130) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at post surgery PSG, y* | 5.49 (3.00, 8.48) | 6.30 (3.42, 9.01) | 5.61 (3.19, 8.94) | .34 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 39 (55.7%) | 30 (50.0%) | 69 (53.1%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 25 (35.7%) | 17 (28.3%) | 42 (32.3%) | |

| Black/African American | 1 (1.4%) | 5 (8.3%) | 6 (4.6%) | |

| Asian | 2 (2.9%) | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| More than 1 race | 3 (4.3%) | 4 (6.7%) | 7 (5.4%) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| BMI percentile category** | .90 | |||

| Under | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Healthy | 30 (49.2%) | 27 (47.4%) | 57 (48.3%) | |

| Overweight | 14 (23.0%) | 15 (26.3%) | 29 (24.6%) | |

| Obese | 16 (26.2%) | 15 (26.3%) | 31 (26.3%) | |

| Sex (female) | 27 (38.6%) | 36 (60.0%) | 63 (48.5%) | .03 |

*Continuous variables are reported as median (interquartile ranges) unless otherwise noted. **Data was absent in a limited number of categories and patients. BMI = body mass index, POSA = positional sleep apnea, PSG = polysomnogram.

Table 3.

Polysomnography data for children with and without POSA following a T&A.

| Non-POSA (n = 70) | POSA (n = 60) | Total (n = 130) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sleep time (TST)* | 379.50 (332.85, 459.00) | 400.00 (366.50, 473.88) | 391.05 (349.75, 463.15) | .04 |

| REM time | 59.75 (41.25, 85.38) | 66.00 (39.15, 92.12) | 61.50 (40.25, 88.50) | .63 |

| NREM time, mean (SD) | 321.22 (68.82) | 350.06 (60.82) | 334.53 (66.58) | .01 |

| Supine time | 169.35 (104.70, 215.00) | 150.30 (96.75, 205.07) | 162.25 (100.75, 215.00) | .49 |

| Nonsupine time, mean (SD) | 213.56 (93.04) | 253.71 (101.26) | 232.09 (98.61) | .02 |

| REM supine time | 17.00 (4.00, 32.00) | 14.50 (2.75, 35.12) | 16.50 (3.25, 32.75) | .91 |

| REM nonsupine time | 36.50 (21.00, 63.00) | 38.00 (16.38, 65.25) | 37.00 (17.50, 64.50) | .96 |

| NREM supine time | 149.50 (92.50, 196.50) | 102.75 (71.12, 168.62) | 137.00 (89.00, 193.50) | .09 |

| NREM nonsupine time, mean (SD) | 178.90 (77.71) | 223.65 (91.07) | 199.69 (86.69) | .01 |

| Mean SPO2 % TST | 94.00 (92.50, 95.00) | 93.70 (92.72, 94.93) | 93.95 (92.50, 95.00) | .71 |

| SPO2% nadir TST | 83.00 (77.25, 85.00) | 81.00 (78.53, 84.25) | 82.00 (78.00, 85.00) | .46 |

| OAHI | 7.75 (2.82, 12.68) | 4.75 (3.05, 9.03) | 5.75 (2.90, 10.65) | .04 |

| Degree OSA | ||||

| Mild (1–< 5) | 25 (35.7%) | 31 (51.7%) | 56 (43.1%) | |

| Moderate (5–< 10) | 19 (27.1%) | 19 (31.7%) | 38 (29.2%) | |

| Severe (10+) | 26 (37.1%) | 10 (16.7%) | 36 (27.7%) | |

| NREM OAHI | 5.70 (2.42, 9.52) | 3.70 (1.95, 6.80) | 4.25 (2.25, 8.60) | .12 |

| REM OAHI | 15.70 (7.60, 29.30) | 9.15 (3.83, 19.12) | 11.80 (5.00, 23.50) | .01 |

| Supine OAHI | 6.80 (3.95, 14.40) | 9.45 (5.65, 16.50) | 8.20 (4.53, 15.38) | .06 |

| Nonsupine OAHI | 6.65 (2.65, 13.05) | 2.55 (1.50, 4.93) | 3.55 (2.00, 8.40) | <.001 |

| NREM supine OAHI | 6.10 (2.70, 11.00) | 6.60 (4.40, 14.20) | 6.50 (3.30, 12.70) | .28 |

| NREM nonsupine OAHI | 6.10 (2.70, 11.00) | 6.60 (4.40, 14.20) | 6.50 (3.30, 12.70) | .28 |

| REM supine OAHI | 16.05 (3.40, 37.45) | 18.45 (5.25, 33.20) | 17.50 (4.35, 34.83) | .87 |

| REM nonsupine OAHI | 12.25 (4.57, 29.70) | 3.10 (1.40, 9.40) | 7.00 (2.60, 21.80) | <.001 |

*Continuous variables are reported as median interquartile ranges) unless otherwise noted. Time reported in minutes. NREM = nonrapid eye movement, OAHI = obstructive apnea-hypopnea index, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, REM = rapid eye movement, POSA = positional sleep apnea, SD = standard deviation, SPO2 = oxygen saturation, T&A = adenotonsillectomy.

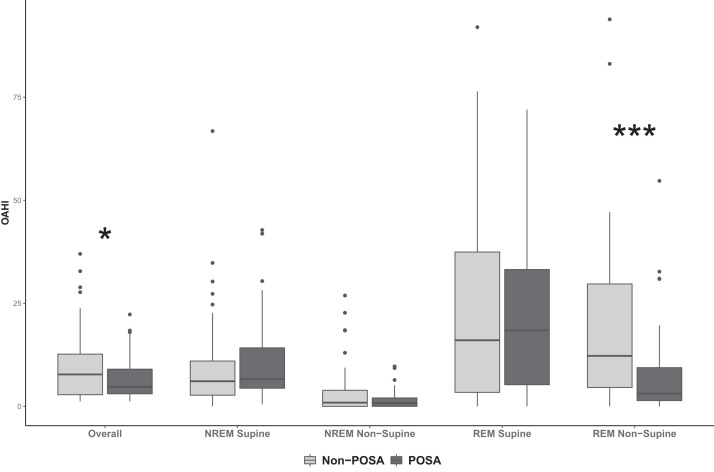

Obstructive events by sleep stage and position were further investigated. Of note, the median time spent in REM supine sleep was less than 30 minutes. POSA patients had a lower REM nonsupine OAHI (P < .05). REM supine OAHI was highest in the POSA cohort but was not significantly different from the non-POSA cohort. POSA patients had a lower REM nonsupine OAHI compared to non-POSA patients (3.1 vs 12.25; P < .05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Obstructive apnea-hypopnea index (OAHI) distribution by sleep stage and position for positional obstructive sleep apnea (POSA) and non-POSA cohorts.

Median OAHI was greater in the non-POSA cohort (*P < .05). POSA patients had a lower rapid eye movement nonsupine OAHI compared to non-POSA patients (***P < .001). NREM = nonrapid eye movement, REM = rapid eye movement.

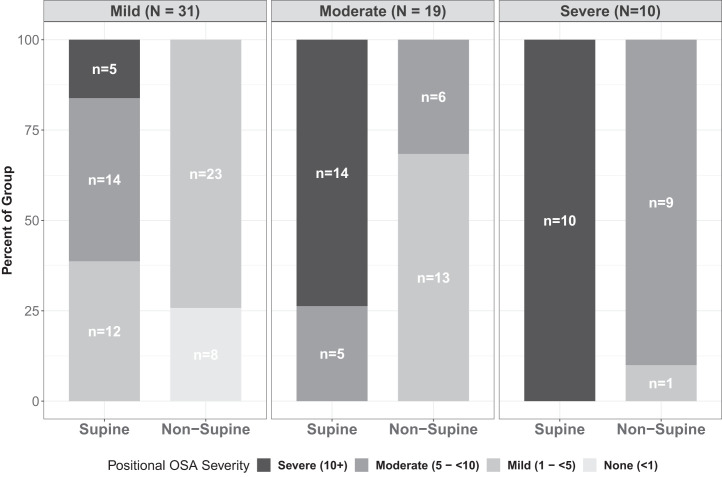

Sixty (46%) of the mixed-sleep individuals had POSA, of which 29 (48%) had moderate/severe OSA (Figure 2). Sleeping off their backs converted 14 (48%) of the 29 children with moderate/severe OSA to mild OSA. Age, BMI percentile category, percent of REM supine sleep, and percent of REM nonsupine sleep did not influence the presence of POSA. BMI-percentile category was not associated with POSA, when adjusted for age and time spent in REM and non-REM sleep (P > .05).

Figure 2. Positional obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) rates for overall mixed sleep OSA categories.

DISCUSSION

POSA is characterized by an OAHI that is at least twice as high in the supine position compared to the nonsupine position.30 In our cohort, the prevalence of POSA in children with DS was similar to findings in obese children.21,31 Our data support the hypothesis that children with DS with refractory OSA following T&A are more likely to have OSA in the supine position. Approximately half of the children with a residual OAHI ≥ 1 event/h met the criteria for POSA. Potentially, positional therapy is a viable treatment option and may convert almost 50% of children with moderate/severe POSA (OAHI ≥ 5 events/h) patients to at most mild OSA.

In this investigation, the presence of POSA was not influenced by age, obesity status, or sleep stage, which is similar to other studies.21,35 Although the amount of REM sleep was similar for both the POSA and non-POSA group, children with POSA had fewer respiratory events during REM nonsupine sleep compared to non-POSA children. For children with DS, anatomy and neuromuscular tone may play a pivotal role. Children with DS are known to have relative macroglossia and lower muscle tone.36,37 Either of these conditions may contribute to POSA, especially during stage REM sleep,3,4,22,26,38–40 which is associated with loss of genioglossus tone and reduced pharyngeal muscle activity. In our investigation, the AHI was higher in REM supine sleep for both cohorts but children with POSA had a significantly lower REM nonsupine OAHI. Potentially, anatomical obstruction related to gravity is increased in our POSA patients. Our conclusions are limited as time spent in REM-supine was small. Further investigations are necessary to determine the contributions of anatomy and muscle tone to POSA.

For children with refractory OSA following a T&A, the primary treatment is noninvasive ventilation; however, the adherence rate for children to these therapies is low.16,17,41,42 In addition, there is a risk of craniofacial changes due to the mask interference depending upon the child’s age, which may place children with DS at greater risk with their known midface hypoplasia.43 Drug-induced sleep endoscopy–directed surgery is another option and may include the following procedures: supraglottoplasty, lingual tonsillectomy, posterior tongue base reduction, or palatal surgery.13 A less-invasive and potentially as effective treatment option is positional therapy.44 Positional devices studied in adults have demonstrated reduced AHI, supine sleep time, and daytime somnolence.45–48 Compliance to positional therapy devices range from 38–89% measured at 1 month and 1 year after treatment initiation.46–49 Of note, for those who are continuous positive airway pressure–compliant, continuous positive airway pressure has a greater reduction in AHI compared to positional therapy.50

Investigation of positional devices in the pediatric population has yet to be studied and may provide a successful alternative in select patients. Almost half of the study patients with POSA have the potential to be successfully treated with positional therapy alone to no longer have moderate/severe OSA. This underscores the importance of reviewing the sleep study results for a positional component. Although positional therapy is infrequently recommended in children compared with adults,51 our results demonstrate that further investigation of success and feasibility of positional therapy as a management option for persistent OSA in children with DS is warranted. An initial evaluation of positional therapy success may be further investigated when undergoing drug-induced sleep endoscopy. At the authors’ institution the drug-induced sleep endoscopy protocol has been modified to include positioning maneuvers when POSA is present on the pre–drug-induced sleep endoscopy PSG.

Despite the promising findings, the current study has a few limitations besides being a retrospective study. A selection bias may exist since not every child with DS during the study period underwent a postoperative PSG. Subsequently, the prevalence of POSA in this cohort may be an overestimate. In addition, for our laboratory, body position documentation relies upon the acquiring sleep technologist so it may be inaccurate at times. However, this risk is mitigated since body position accuracy is reviewed by both the scoring technician and interpreting physician. Also, the technologist-to-patient ratio is low (1.2:1), so the technologist is not overextended. Another limitation is that our study did not specify within nonsupine sleep right-lateral, left-lateral, or prone positioning. Of note, it is unlikely that there would be sufficient time in each position to perform a meaningful analysis. The value of specific nonsupine sleep is still being elucidated, which may include a unique seated sleeping position as described by Senthilvel and Krishna.35

The strengths of the study include that this cohort is the largest POSA investigation of children with DS following a T&A. The study population was confined to young children with DS who had a postoperative PSG. By requiring at least 30 minutes of both supine and nonsupine sleep, the risk of a sampling error in the OAHI is reduced. Future directions include investigating whether children with DS will tolerate position maneuvers and whether they have improvement in their quality of life with intervention.

Sleep physicians and otolaryngologists should be cognizant that the OAHI may be an underestimate if it does not include supine sleep. Positional therapy is a potential treatment option for children with persistent OSA following an adenotonsillectomy, especially in children with DS, and warrants further investigation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- BMI

body mass index

- DS

Down syndrome

- OAHI

obstructive apnea-hypopnea index

- POSA

positional sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnogram

- SpO2

oxygen saturation

- T&A

adenotonsillectomy

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest. Work for this study was performed at Children’s Hospital of Colorado (CHCO) and University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. This study was funded by the Children’s Hospital Center for Research in Outcomes in Children’s Surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dyken ME , Lin-Dyken DC , Poulton S , Zimmerman MB , Sedars E . Prospective polysomnographic analysis of obstructive sleep apnea in down syndrome . Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003. ; 157 ( 7 ): 655 – 660 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Miguel-Díez J , Villa-Asensi JR , Alvarez-Sala JL . Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in children with Down syndrome: polygraphic findings in 108 children . Sleep. 2003. ; 26 ( 8 ): 1006 – 1009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shott SR , Amin R , Chini B , Heubi C , Hotze S , Akers R . Obstructive sleep apnea: should all children with Down syndrome be tested? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006. ; 132 ( 4 ): 432 – 436 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ng DK , Hui HN , Chan CH , et al . Obstructive sleep apnoea in children with Down syndrome . Singapore Med J. 2006. ; 47 ( 9 ): 774 – 779 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzgerald DA , Paul A , Richmond C . Severity of obstructive apnoea in children with Down syndrome who snore . Arch Dis Child. 2007. ; 92 ( 5 ): 423 – 425 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marcus CL , Keens TG , Bautista DB , von Pechmann WS , Ward SL . Obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome . Pediatrics. 1991. ; 88 ( 1 ): 132 – 139 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allanson JE , O’Hara P , Farkas LG , Nair RC . Anthropometric craniofacial pattern profiles in Down syndrome . Am J Med Genet. 1993. ; 47 ( 5 ): 748 – 752 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silverman M . Airway obstruction and sleep disruption in Down’s syndrome . Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988. ; 296 ( 6637 ): 1618 – 1619 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lefaivre JF , Cohen SR , Burstein FD , et al . Down syndrome: identification and surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea . Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997. ; 99 ( 3 ): 629 – 637 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marcus CL , Brooks LJ , Draper KA , et al. American Academy of Pediatrics . Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome . Pediatrics. 2012. ; 130 ( 3 ): 576 – 584 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: : American Academy of Sleep Medicine; ; 2014. . [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ingram DG , Ruiz AG , Gao D , Friedman NR . Success of tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome . J Clin Sleep Med. 2017. ; 13 ( 8 ): 975 – 980 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Best J , Mutchnick S , Ida J , Billings KR . Trends in management of obstructive sleep apnea in pediatric patients with Down syndrome . Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018. ; 110 : 1 – 5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nehme J , LaBerge R , Pothos M , et al . Treatment and persistence/recurrence of sleep-disordered breathing in children with Down syndrome . Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019. ; 54 ( 8 ): 1291 – 1296 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marcus CL , Moore RH , Rosen CL , et al. Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT) . A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea . N Engl J Med. 2013. ; 368 ( 25 ): 2366 – 2376 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beebe DW , Byars KC . Adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea adhere poorly to positive airway pressure (PAP), but PAP users show improved attention and school performance . PLoS One. 2011. ; 6 ( 3 ): e16924 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawkins SMM , Jensen EL , Simon SL , Friedman NR . Correlates of pediatric CPAP adherence . J Clin Sleep Med. 2016. ; 12 ( 6 ): 879 – 884 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amaddeo A , Khirani S , Griffon L , Teng T , Lanzeray A , Fauroux B . Non-invasive ventilation and CPAP failure in children and indications for invasive ventilation . Front Pediatr. 2020. ; 8 : 544921 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verhelst E , Clinck I , Deboutte I , Vanderveken O , Verhulst S , Boudewyns A . Positional obstructive sleep apnea in children: prevalence and risk factors . Sleep Breath. 2019. ; 23 ( 4 ): 1323 – 1330 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walter LM , Dassanayake DUN , Weichard AJ , Davey MJ , Nixon GM , Horne RSC . Back to sleep or not: the effect of the supine position on pediatric OSA: sleeping position in children with OSA . Sleep Med. 2017. ; 37 : 151 – 159 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tholen K , Meier M , Kloor J , Friedman N . Persistent OSA in obese children: does body position matter? J Clin Sleep Med. 2021. ; 17 ( 2 ): 227 – 232 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. El-Kersh K , Cavallazzi R , Patel PM , Senthilvel E . Effect of sleep state and position on obstructive respiratory events distribution in adolescent children . J Clin Sleep Med. 2016. ; 12 ( 4 ): 513 – 517 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pereira KD , Roebuck JC , Howell L . The effect of body position on sleep apnea in children younger than 3 years . Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005. ; 131 ( 11 ): 1014 – 1016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang XW , Li Y , Zhou F , Guo CK , Huang ZT . Association of body position with sleep architecture and respiratory disturbances in children with obstructive sleep apnea . Acta Otolaryngol. 2007. ; 127 ( 12 ): 1321 – 1326 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernandes do Prado LB , Li X , Thompson R , Marcus CL . Body position and obstructive sleep apnea in children . Sleep. 2002. ; 25 ( 1 ): 66 – 71 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verginis N , Jolley D , Horne RSC , Davey MJ , Nixon GM . Sleep state distribution of obstructive events in children: is obstructive sleep apnoea really a rapid eye movement sleep-related condition? J Sleep Res. 2009. ; 18 ( 4 ): 411 – 414 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cuhadaroglu C , Keles N , Erdamar B , Aydemir N , Yucel E , Oguz F , Deger K . Body position and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome . Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003. ; 36 ( 4 ): 335 – 338 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dayyat E , Maarafeya MM , Capdevila OS , Kheirandish-Gozal L , Montgomery-Downs HE , Gozal D . Nocturnal body position in sleeping children with and without obstructive sleep apnea . Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007. ; 42 ( 4 ): 374 – 379 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pereira KD , Rathi NK , Fatakia A , Haque SA , Castriotta RJ . Body position and obstructive sleep apnea in 8-12-month-old infants . Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008. ; 72 ( 6 ): 897 – 900 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cartwright RD , Diaz F , Lloyd S . The effects of sleep posture and sleep stage on apnea frequency . Sleep. 1991. ; 14 ( 4 ): 351 – 353 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Selvadurai S , Voutsas G , Massicotte C , et al . Positional obstructive sleep apnea in an obese pediatric population . J Clin Sleep Med. 2020. ; 16 ( 8 ): 1295 – 1301 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nisbet LC , Phillips NN , Hoban TF , O’Brien LM . Effect of body position and sleep state on obstructive sleep apnea severity in children with Down syndrome . J Clin Sleep Med. 2014. ; 10 ( 1 ): 81 – 88 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iber C , Ancoli-Israel S , Chesson A , Quan SF ; for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed . Westchester, IL: : American Academy of Sleep Medicine; ; 2007. . [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berry RB , Budhiraja R , Gottlieb DJ , et al . Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . J Clin Sleep Med. 2012. ; 8 ( 5 ): 597 – 619 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Senthilvel E , Krishna J . Body position and obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome . J Clin Sleep Med. 2011. ; 7 ( 2 ): 158 – 162 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guimaraes CVA , Donnelly LF , Shott SR , Amin RS , Kalra M . Relative rather than absolute macroglossia in patients with Down syndrome: implications for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea . Pediatr Radiol. 2008. ; 38 ( 10 ): 1062 – 1067 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santoro JD , Pagarkar D , Chu DT , et al . Neurologic complications of Down syndrome: a systematic review . J Neurol. 2021. ; 268 ( 12 ): 4495 – 4509 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chamseddin BH , Johnson RF , Mitchell RB . Obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome: demographic, clinical, and polysomnographic features . Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019. ; 160 ( 1 ): 150 – 157 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nagao A , Komori M , Kajiyama T , et al . Apnea hypopnea indices categorized by REM/NREM sleep and sleep positions in 100 children with adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea disease . Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019. ; 119 : 32 – 37 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spruyt K , Gozal D . REM and NREM sleep-state distribution of respiratory events in habitually snoring school-aged community children . Sleep Med. 2012. ; 13 ( 2 ): 178 – 184 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Uong EC , Epperson M , Bathon SA , Jeffe DB . Adherence to nasal positive airway pressure therapy among school-aged children and adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome . Pediatrics. 2007. ; 120 ( 5 ): e1203 – e1211 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marcus CL , Rosen G , Ward SL , et al . Adherence to and effectiveness of positive airway pressure therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea . Pediatrics. 2006. ; 117 ( 3 ): e442 – e451 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roberts SD , Kapadia H , Greenlee G , Chen ML . Midfacial and dental changes associated with nasal positive airway pressure in children with obstructive sleep apnea and craniofacial conditions . J Clin Sleep Med. 2016. ; 12 ( 4 ): 469 – 475 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tapia IE , Marcus CL . Newer treatment modalities for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea . Paediatr Respir Rev. 2013. ; 14 ( 3 ): 199 – 203 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Benoist LBL , Verhagen M , Torensma B , van Maanen JP , de Vries N . Positional therapy in patients with residual positional obstructive sleep apnea after upper airway surgery . Sleep Breath. 2017. ; 21 ( 2 ): 279 – 288 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Newell J , Mairesse O , Neu D . Can positional therapy be simple, effective and well tolerated all together? A prospective study on treatment response and compliance in positional sleep apnea with a positioning pillow . Sleep Breath. 2018. ; 22 ( 4 ): 1143 – 1151 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Omobomi O , Quan SF . Positional therapy in the management of positional obstructive sleep apnea-a review of the current literature . Sleep Breath. 2018. ; 22 ( 2 ): 297 – 304 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Beyers J , Vanderveken OM , Kastoer C , et al . Treatment of sleep-disordered breathing with positional therapy: long-term results . Sleep Breath. 2019. ; 23 ( 4 ): 1141 – 1149 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yingjuan M , Siang WH , Leong Alvin TK , Poh HP . Positional therapy for positional obstructive sleep apnea . Sleep Med Clin. 2019. ; 14 ( 1 ): 119 – 133 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Srijithesh PR , Aghoram R , Goel A , Dhanya J . Positional therapy for obstructive sleep apnoea . Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019. ; 5 : CD010990 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Barnes H , Edwards BA , Joosten SA , Naughton MT , Hamilton GS , Dabscheck E . Positional modification techniques for supine obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Sleep Med Rev. 2017. ; 36 : 107 – 115 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]