Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate COVID-19 disparities among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and non-Hispanic White persons in urban areas.

Methods. Using COVID-19 case surveillance data, we calculated cumulative incidence rates and risk ratios (RRs) among non-Hispanic AI/AN and non-Hispanic White persons living in select urban counties in the United States by age and sex during January 22, 2020, to October 19, 2021. We separated cases into prevaccine (January 22, 2020–April 4, 2021) and postvaccine (April 5, 2021–October 19, 2021) periods.

Results. Overall in urban areas, the COVID-19 age-adjusted rate among non-Hispanic AI/AN persons (n = 47 431) was 1.66 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.36, 2.01) times that of non-Hispanic White persons (n = 2 301 911). The COVID-19 prevaccine age-adjusted rate was higher (8227 per 100 000; 95% CI = 6283, 10 770) than was the postvaccine rate (3703 per 100 000; 95% CI = 3235, 4240) among non-Hispanic AI/AN compared with among non-Hispanic White persons (2819 per 100 000; 95% CI = 2527, 3144; RR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.17, 1.48).

Conclusions. This study highlights disparities in COVID-19 between non-Hispanic AI/AN and non-Hispanic White persons in urban areas. These findings suggest that COVID-19 vaccination and other public health efforts among urban AI/AN communities can reduce COVID-19 disparities in urban AI/AN populations. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(10):1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306966)

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities have borne a disproportionate burden of COVID-19. In March 2020, rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death among AI/AN persons have been reported to be 1.7, 3.5, and 2.4 times those of non-Hispanic White persons, respectively.1–3 The most recent analysis during January 31 through July 3, 2020 reported a COVID-19 incidence rate among AI/AN persons that was 3.5 times that of non-Hispanic White persons (594 per 100 000 vs 169 per 100 000, respectively) in a subset of 23 states with more than 70% complete race/ethnicity data.4 However, these analyses did not specifically address AI/AN people living in US urban areas and were conducted before COVID-19 vaccine availability.

The health needs of urban AI/AN people have become increasingly amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic for several reasons. Historical and ongoing health and socioeconomic inequities in urban settings have pervasive effects on the health of AI/AN people and, therefore, may play a critical role in the risk of COVID-19 exposure, transmission, morbidity, and mortality.

First, urban areas of today are located on the original homelands of AI/AN people, and according to the US Census, approximately 78% of AI/AN people in the United States live, work, and receive education and health care in urban areas.5,6 Moreover, federal legislation, including the Indian Relocation Act of 1957,7 incentivized AI/AN people to relocate from their tribal lands for better health care, education, and work; however, these services often did not materialize because of a lack of funding and priority.8 Second, urban environments pose a combination of COVID-19 exposure risks because of high population densities, reliance on public transportation, housing insecurity, and essential worker occupations that may not provide health insurance, paid sick leave, childcare, or options to work from home.9 Lastly, AI/AN populations often have a higher prevalence of underlying health conditions (e.g., diabetes, obesity, heart conditions), poverty, food and housing insecurity, homelessness, and limited access to quality health care, health insurance, and nutritious foods than other racial groups.10 These and other social determinants of health may make it difficult to follow public health guidelines to safely quarantine, work and go to school, and avoid close contact and crowded spaces to limit the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Despite the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 in the AI/AN population, AI/AN people have some of the highest rates of COVID-19 vaccination in the United States.11,12 Safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines received US Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorization on December 11 and 18, 2020, for Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, respectively, and February 27, 2021, for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, to reduce the burden of severe COVID-19 outcomes.13–15 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 data tracker, vaccination rates reached 48% by September 2021 in AI/AN people, which was higher than were rates in other racial groups (42% in Asians, 38% in Whites, and 30% in African Americans).3,12 However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether this has decreased the rate of COVID-19 among AI/AN persons compared with other races and ethnicities in the United States. Further study of the burden of COVID-19 among AI/AN persons in urban areas, particularly after vaccine rollout, is needed to inform national and local public health actions to reduce transmission, decrease disparities, and improve health outcomes in urban AI/AN communities.

We examined reports of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases among urban non-Hispanic AI/AN persons from January 22, 2020, to October 19, 2021, and compared the period before vaccination (January 22, 2020–April 4, 2021) to after vaccination (April 5–October 19, 2021). We limited our analysis to urban counties from 40 states in the United States with 70% or more complete race/ethnicity information and more than 5 cases among non-Hispanic AI/AN persons and 5 cases among non-Hispanic White persons.

METHODS

Laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases were reported to the CDC through the CDC COVID-19 case report form and the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System from January 22, 2020, to October 19, 2021.16,17 We defined a laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case as a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, from a respiratory specimen, using real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction testing. We excluded probable cases and cases without information on race (n = 10 203 116), ethnicity (n = 8 527 491), county of residence (n = 405 050), and report date (n = 2 843 587) from this analysis, as well as cases among persons who repatriated to the United States from the city of Wuhan, China, and the Diamond Princess cruise ship COVID-19 outbreak.

We classified AI/AN race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic AI/AN alone or in combination with other races. We defined the comparison group as non-Hispanic White. We chose non-Hispanic White as the comparison group to avoid comparing rates among AI/AN persons to other marginalized populations that experience similar health disparities. Because all analyses reported here were limited to non-Hispanic populations, we have omitted the term “non-Hispanic” from this study when discussing both groups.

We classified an urban county as one that either (1) was identified as metropolitan using the National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme (large central metro, large fringe metro, medium metro, small metro), or (2) was in the service area of the Urban Indian Health Institute.18 To improve the stability of rate estimates, we limited analyses to urban counties with more than 5 cases for both AI/AN and White persons and 70% or more complete race/ethnicity information. We defined a laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case as having “complete” race/ethnicity if it met both of the following criteria: (1) race was listed as 1 of the 5 Office of Management and Budget 1997 racial categories, and (2) ethnicity was listed as either Hispanic/Latino or non-Hispanic/Latino.19

We established 2 analysis periods—before vaccination (January 22, 2020–April 4, 2021) and after vaccination (April 5–October 19, 2021)—based on a cutoff date of April 5, 2021, when more than 25% of the AI/AN population in the United States achieved full vaccination coverage based on CDC data tracker data.3 This date and percentage vaccination coverage allowed us to evaluate before and after vaccination without the potential effects of waning immunity and new variants with the potential to evade vaccine-derived immunity. Additionally, we wanted to avoid potential diluting effects of the vaccine if we selected an earlier date and lower percentage vaccination coverage because so few people would have been fully vaccinated and the vaccine was limited to frontline health care workers and nursing home residents. The CDC data tracker defines full vaccination coverage as having received a dose of a single-shot COVID-19 vaccine or the second dose of the 2-dose COVID-19 vaccine series. To make comparisons between periods, we standardized the postvaccination period to the same urban geographic counties and states as the prevaccination period.

We used a generalized estimating equations (GEE) regression model to calculate cumulative incidence (cumulative cases per 100 000 population), risk ratios (RRs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for AI/AN and White persons. We adjusted the overall estimates for age (categorical) and stratified unadjusted estimates by age group (0–19 years, 20–54 years, and ≥ 55 years) and sex. We used GEE models, which perform well for estimating rates with correlated data, to account for clustering by county.20 We used the CDC’s 2018 National Center for Health Statistics bridged-race population estimates as population denominators.21 We compared the cumulative incidence, RR, and 95% CI estimates of the postvaccination period with the prevaccination period. To examine the completeness of data for severe COVID-19 outcomes among AI/AN and White persons, we calculated the percentage of known and unknown hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death status by dividing the number of cases with known (yes or no response) or unknown (missing or blank response) outcomes status by the total number of COVID-19 cases for that particular outcome. We set statistical significance at an α level of 0.05. We conducted and validated analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 4.02 (RStudio, Boston, MA). We constructed maps using R version 4.02.

RESULTS

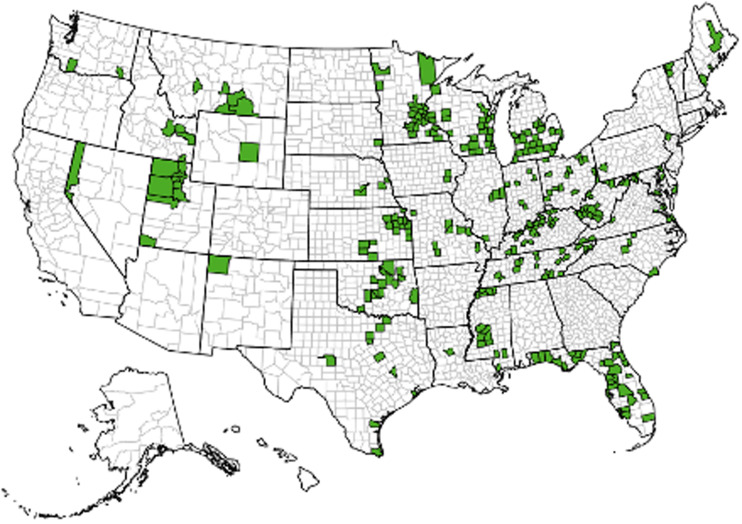

During January 22, 2020, through October 19, 2021, there were 31 192 253 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC in the United States. In the 1183 counties classified as urban, there were 58 362 cases among AI/AN persons and 3 274 534 cases among White persons. In addition, 326 urban counties (27.5%) in 40 states had more than 5 cases among AI/AN and White persons and 70% or more complete race/ethnicity (Figure 1). Among these 326 urban counties, there were 2 301 911 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported among AI/AN and White persons, of which 47 431 were among AI/AN persons and 2 254 480 were among White persons.

FIGURE 1—

Aggregate Urban County–Level Analysis of COVID-19 Cases in Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Non-Hispanic White Persons: 326 US Counties and 40 US States, January 22, 2020–October 19, 2021

Note. Urban counties indicate 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_166.pdf) and Urban Indian Health Program/Urban Indian Health Network service counties (including nonurban counties: KS: Reno County; MT: Big Horn, Broadwater, Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Silver Bow counties; NV: Churchill and Douglas counties; OK: Pottawatomie County; SD: Brown, Hughes, and Stanley counties). The 40 states were AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, MA, ME, MD, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NV, NJ, NM, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, and WI.

The overall cumulative incidence rate of COVID-19 after adjusting for age among urban-residing AI/AN persons during January 22, 2020, through October 19, 2021, was 12 360 per 100 000 population (95% CI = 10 230, 14 930), which was 1.66 (95% CI = 1.36, 2.01; P < .05) times that of urban-residing White persons (7468 per 100 000 population; 95% CI = 6881, 8106; Table 1). The median age was 34 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 21–51 years) among AI/AN persons and 40 years (IQR = 25–58 years) among White persons. For both AI/AN and White persons, most cases were aged 20 to 54 years (57.8% and 52.8%, respectively) and were female (54.6% and 52.7%, respectively; Table 1). Across the age groups, AI/AN persons were younger than White persons. Among all age and sex categories, COVID-19 incidence was significantly greater among AI/AN persons than among White persons (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Cumulative Incidence and RRs for Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Non-Hispanic White Persons in Urban Areas, by Age and Sex Groups, in the Overall, Pre- and Postvaccination Periods: United States, January 22, 2020–October 19, 2021

| Characteristics | AI/AN,a No. (%) | AI/AN,a Cumulative Incidenceb (95% CI) | Non-Hispanic White, No. (%) | Non-Hispanic White Cumulative Incidence,b (95% CI) | RRc (95% CI) |

| Overall (January 22, 2020–October 19, 2021; 326 urban counties)d | |||||

| Total | 47 431 | 12 360 (1 0230, 1 4930) | 2 254 480 | 7 468 (6 881, 8 106) | 1.66e (1.36, 2.01) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 0–19 | 10 328 (21.8) | 9 045 (7 804, 1 0480) | 400 670 (17.8) | 5 998 (5 486, 6 559) | 1.51e (1.28, 1.78) |

| 20–54 | 27 423 (57.8) | 15 080 (1 2500, 1 8200) | 1 190 324 (52.8) | 9 122 (8 325, 9 995) | 1.65e (1.36, 2.01) |

| ≥55 | 9 680 (20.4) | 11 860 (9 334, 1 5070) | 6 63486 (29.4) | 6 368 (5 954, 6 810) | 1.86e (1.46, 2.38) |

| Sexf | |||||

| Female | 25 891 (54.6) | 13 280 (1 1120, 1 5860) | 1 188 188 (52.7) | 7 751 (7 155, 8 404) | 1.71e (1.42, 2.06) |

| Male | 21 352 (45.0) | 11 610 (9 598, 1 4050) | 1 063 320 (47.2) | 7 153 (6 575, 7 782) | 1.52e (1.33, 1.99) |

| Before vaccination (January 22, 2 020–April 4, 2021; 345 urban counties)g | |||||

| Total | 36 278 | 8 227 (6 283, 1 0770) | 1 586740 | 4 416 (3 982, 4 897) | 1.86e (1.41, 2.45) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 0–19 | 7 129 (19.7) | 5 652 (4 461, 7 162) | 237 862 (15.0) | 3 050 (2 684, 3 466) | 1.85e (1.44, 2.39) |

| 20–54 | 21 149 (58.3) | 10 070 (7 701, 1 3170) | 842 644 (53.1) | 5 372 (4 785, 6 031) | 1.87e (1.43, 2.47) |

| ≥55 | 8 000 (22.0) | 8 324 (6 155, 1 1260) | 506 234 (31.9) | 4 106 (3 780, 4 460) | 2.03e (1.50, 2.75) |

| Sexf | |||||

| Female | 19 804 (54.8) | 8 853 (6 871, 1 1410) | 839 028 (52.9) | 4 597 (4 157, 5 084) | 1.93e (1.49, 2.49) |

| Male | 16 325 (45.2) | 6 345 (4 662, 8 634) | 745 912 (47.1) | 2 761 (2 450, 3 112) | 1.83e (1.38, 2.43) |

| After vaccination (April 5, 2021–October 19, 2021; 322 urban counties)h | |||||

| Total | 16 117 | 3 703 (3 235, 4 240) | 984 915 | 2 819 (2 527, 3 144) | 1.31e (1.17, 1.48) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 0–19 | 4 257 (26.4) | 3 339 (2 957, 3 770) | 214 166 (22.0) | 2 867 (2 615, 3 143) | 1.16e (1.03, 1.32) |

| 20–54 | 9 119 (56.6) | 4 391 (3 757, 5 131) | 517 309 (53.1) | 3 419 (3 039, 3 847) | 1.28e (1.12, 1.47) |

| ≥55 | 2 741 (17.0) | 2 965 (2 617, 3 360) | 253 440 (25.9) | 2 165 (1 943, 2 413) | 1.37e (1.24, 1.51) |

| Sexf | |||||

| Female | 12 292 (54.2) | 3 993 (3 504, 4 550) | 815 072 (52.5) | 2 947 (2 647, 3 282) | 1.35e (1.21, 1.52) |

| Male | 10 295 (45.4) | 3 442 (2 976, 3 980) | 733 442 (47.3) | 2 779 (2 501, 3 089) | 1.24e (1.09, 1.40) |

Note. AI/AN=American Indian and Alaska Native; CI=confidence interval; RR=risk ratio.

Source. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 case reports, 2018 National Center for Health Statistics bridged-race population estimates.

aAlone or in combination with other races and non-Hispanic.

bRate per 100 000 population.

cRR for AI/AN vs non-Hispanic White persons.

d40 states: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, MA, ME, MD, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI; 326 urban counties.

eRR is statistically significant (P < .05).

fOmits cases where sex is listed as missing, unknown, or other.

g40 states: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY; 345 urban counties.

h37 states: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, ME, MD, MI, MN, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY; 322 urban counties.

In the prevaccination period (January 22, 2020–April 4, 2021), 1 623 018 COVID-19 cases among AI/AN and White persons were reported for 345 urban counties in 40 states with more than 5 cases among both AI/AN and White persons and with 70% or more complete race/ethnicity data (Figure 2). Of these, 36 278 were AI/AN persons (age-adjusted cumulative incidence per 100 000 = 8227; 95% CI = 6283, 10 770) and 1 586 740 were White persons (cumulative incidence per 100 000 = 4416; 95% CI = 3982, 4897). Across the age groups, AI/AN persons were younger than were White persons. After adjusting for age, AI/AN people were 1.86 (95% CI = 1.41, 2.45; P < .05) times as likely to be infected with COVID-19 than were White persons during the prevaccination period. For each age and sex category, COVID-19 incidence was significantly greater among AI/AN persons than among White persons (Table 1).

FIGURE 2—

Urban Counties Included in the County-Level Analysis of COVID-19 Cases Before and After the Vaccination Period in Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Non-Hispanic White Persons: United States, January 22, 2020–October 19, 2021

Note. Urban counties indicate 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_166.pdf) and Urban Indian Health Program/Urban Indian Health Network service counties (including nonurban counties: KS: Reno County; MT: Big Horn, Broadwater, Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Silver Bow counties; NV: Churchill and Douglas counties; OK: Pottawatomie County; SD: Brown, Hughes, and Stanley counties). The 345 urban counties and 40 states in the prevaccine period (January 22, 2020–April 4, 2021) were AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY. The 322 urban counties and 37 states in the postvaccine period (April 5, 2021–October 19, 2021) were AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, ME, MD, MI, MN, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY.

In the postvaccination period April 5, 2021, through October 19, 2021, 1 001 032 cases among AI/AN and White persons were reported for the same geographic area as in the prevaccination period (data available for 322 urban counties in 37 states; Figure 2). Of these persons in the postvaccination period, 16 117 were AI/AN persons (cumulative incidence per 100 000 = 3703; 95% CI = 3235, 4240) and 984 915 were White persons (cumulative incidence per 100 000 = 2819; 95% CI = 2527, 3144). After adjusting for age, during the postvaccination period, the rate of COVID-19 among AI/AN persons was 1.31 (95% CI = 1.17, 1.48; P < .05) times that among White persons. For each age and sex category, COVID-19 incidence was significantly greater among AI/AN persons than among White persons (Table 1).

Completeness of data on COVID-19–related hospitalization, ICU admission, and death were higher among White persons than AI/AN persons during our period of interest, including during the pre- and postvaccination periods (Table 2). During January 22, 2020, through October 19, 2021, hospitalization status, ICU admission status, and death status were known for 63.7%, 13.5%, and 59.3%, respectively, of White COVID-19 patients, whereas 60.0% of hospitalization status, 6.4% of ICU admission status, and 50.9% of death status were known for AI/AN COVID-19 patients. Because of the disproportionate amount of missing hospitalization, ICU admission, and death status data, we could not analyze COVID-19–related severe outcomes.

TABLE 2—

Reported Cases and Proportions of Known and Unknown COVID-19–Related Hospitalization, ICU Admission, and Death for Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Non-Hispanic White Persons in Urban Areas for the Overall, Pre-, and Postvaccincation Periods: United States, January 22, 2020–October 19, 2021

| Severe Outcomes | Overall (Jan. 22, 2020–Oct. 19, 2021)a | Before Vaccination (Jan. 22, 2020–Apr. 4, 2021)b | After Vaccination (Apr. 5, 2021–Oct. 19, 2021)c | |||

| AI/AN,d No. (%) | Non-Hispanic White, No. (%) | AI/AN,d No. (%) | Non-Hispanic White, No. (%) | AI/AN,d No. (%) | Non-Hispanic White, No. (%) | |

| Total | 47 431 | 2 254 480 | 36 278 | 1 586 740 | 16 117 | 984 915 |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Knowne | 28 471 (60.0) | 1 435 572 (63.7) | 25 203 (69.5) | 1 148 136 (72.4) | 7 801 (48.4) | 464 554 (47.2) |

| Unknownf | 18 960 (40.0) | 818 908 (36.3) | 11 075 (30.5) | 438 604 (27.6) | 8 316 (51.6) | 520 361 (52.8) |

| ICU admission | ||||||

| Knowne | 3 039 (6.4) | 304 578 (13.5) | 2 482 (6.8) | 264 382 (16.7) | 1 014 (6.3) | 87 514 (8.9) |

| Unknownf | 44 392 (93.6) | 1 949 902 (86.5) | 33 796 (93.2) | 1 322 358 (83.3) | 15 103 (93.7) | 897 401 (91.1) |

| Death | ||||||

| Knowne | 24 148 (50.9) | 1 337 482 (59.3) | 20 652 (56.9) | 1 008 694 (63.6) | 9 682 (60.0) | 600 137 (60.9) |

| Unknownf | 23 283 (49.1) | 916 998 (40.7) | 15 626 (43.1) | 578 046 (36.4) | 6 435 (40.0) | 384 778 (39.1) |

Note. AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native; ICU = intensive care unit.

Source. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 case reports.

a40 states: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, MA, ME, MD, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI; 326 urban counties.

b40 states: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY; 345 urban counties.

c37 states: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, ME, MD, MI, MN, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NC, OH, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY; 322 urban counties.

dAlone or in combination with other races and non-Hispanic.

eHospitalization, ICU admission, and death status were considered known if the response was “yes” or “no” (not “missing” or “unknown”).

fHospitalization, ICU admission, and death status were considered unknown if the response was “missing” or “unknown” (not “yes” or “no”).

DISCUSSION

AI/AN persons experienced a disproportionate rate of COVID-19 than did White persons (RR = 1.66; 95% CI = 1.36, 2.01; P < .05) in US urban areas from January 22, 2020, to October 19, 2021. However, the disparity in the rate of COVID-19 comparing AI/AN with White persons was lower in the postvaccination period than in the prevaccination period. Given that AI/AN communities have some of the highest rates of COVID-19 vaccination in the United States,11,12 these findings suggest that COVID-19 vaccination and other public health efforts among AI/AN communities in urban areas may have been successful in reducing the COVID-19 disease burden.

The decreased rate of COVID-19 in AI/AN persons compared with White persons during the postvaccination period may be attributable to the COVID-19 vaccine, immunity from previous infection, and continued physical distancing and mask wearing in AI/AN communities.22 A previous study showed reduced disease burden of COVID-19 in fully vaccinated adults, regardless of race and ethnicity, compared with unvaccinated adults in 13 US jurisdictions, where the risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and deaths were significantly lower.23 In addition, efforts by AI/AN communities and organizations such as the Urban Indian Health Institute, Tribal Health Boards, Tribal Health Clinics, and Indian Health Service facilities to increase COVID-19 vaccination uptake in urban and rural tribal settings through vaccination events and campaigns (e.g., For the Love of Our People24) have likely played a critical role in decreasing COVID-19 risk in AI/AN persons. Many of these AI/AN community-led vaccination strategies have focused on protecting elders and the community and addressing vaccine hesitancy.

Although the resulting high rate of vaccination among AI/AN is an achievement, we found significantly higher rates of COVID-19 for each age and sex category of AI/AN persons compared with White persons in urban areas for the overall period we examined, including in the pre- and postvaccination periods. Previous studies have shown that AI/AN populations often have a higher prevalence of underlying health conditions (e.g., diabetes, obesity, heart conditions) and limited access to quality health care and health insurance than do other racial groups;10,25–27 therefore, AI/AN persons with underlying conditions may be at increased risk for COVID-19 and severe outcomes. Additionally, reports on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among persons of color show higher risk and exposure to COVID-19 compared with White persons, as they are highly represented in low-wage essential work, are caregivers at home, and provide services for others,28 including residing in highly populated urban areas and in overcrowded conditions as well as relying on public transportation—making social distancing difficult.9 Therefore, continued efforts to reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission through public health measures such as masking, physical distancing, up-to-date vaccination, and booster doses where appropriate remain important.29–31

Higher percentages of unknown and missing COVID-19 severe health outcomes data in AI/AN persons demonstrate the need for more complete COVID-19 data for hospitalization, ICU admission, and death. Missing data regarding race/ethnicity, COVID-19 symptoms, underlying health conditions, and severe outcomes not only reduced the statistical power of this study but also precluded certain meaningful epidemiologic analyses of COVID-19 in urban AI/AN people.32

Limitations

This study has several notable limitations. First, race and ethnicity data are disproportionately missing for racial minorities.33 Second, population-based surveillance systems commonly misclassify AI/AN people as other races or ethnicities, resulting in an underestimate of AI/AN morbidity and mortality.34 Third, our postvaccination period began April 5, 2021, when more than 25% of AI/AN people in the United States were fully vaccinated, and served as a conservative estimate of the postvaccination period. Fourth, the counties studied in the postvaccination period were standardized to urban counties of the prevaccination period; therefore, not all the counties in the postvaccination period necessarily met the more than 5 cases of AI/AN and White persons and the 70% or more complete race/ethnicity data requirements that the overall and prevaccination period counties did, and there might have been more missing race/ethnicity information in the counties during the postvaccination period. Fifth, because the National Center for Health Statistics bridged-race population denominator estimates are reliable only for non-Hispanic AI/AN people, this study excludes people who identify as Hispanic AI/AN, which may lead to an undercount of total AI/AN cases.34,35 Sixth, our findings are observational, and we were not able to determine causality. Finally, we excluded 72% (n = 857) and 70% (n = 831) of urban counties from the aggregate and time analyses, respectively, because of incomplete race/ethnicity data. Notably, the AI/AN populations from urban counties in the aggregate time frame of this study represent only 14.5% of all urban AI/AN individuals in the country—based on 2020 postcensal estimates of the AI/AN population. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to the overall national urban AI/AN population.

Conclusions

Our study highlights the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 among AI/AN persons in urban areas from January 22, 2020, through October 19, 2021, and before COVID-19 vaccines were available in the United States. Importantly, it also highlights a significant achievement by tribal public health professionals and communities, demonstrating a decreased disparity in COVID-19 rates among AI/AN compared with White persons before and after vaccination. Finally, this research contributes to the limited scientific literature on COVID-19 in urban AI/AN people. As others have noted, an urgent need for complete COVID-19 case surveillance data remains,4,33 and health and mortality status assessments for AI/AN populations are often hindered by a lack of complete and accurate data on race and ethnicity in surveillance and vital statistics systems.34 An immediate starting point is to support health care providers, laboratories, and local, tribal, state, and federal agencies to consistently collect and report complete COVID-19 data. Complete data allow a full understanding of COVID-19 in vulnerable, yet resilient, communities to ensure they have the information needed to rapidly respond to COVID-19.

Specifically, complete COVID-19 data are needed in the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System to fully characterize COVID-19 in AI/AN people, including more complete reporting of race/ethnicity, comorbid conditions, exposure information, symptoms, hospitalization, ICU admission, and death. Our findings can help inform national and local public health actions to reduce COVID-19 transmission, improve health outcomes, address equity in vaccination, and increase resiliency in urban AI/AN communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Indian Health Service, Department of Human and Health Services (grant U1B1IHS0006 to the Urban Indian Health Institute).

We thank Charles E. Rose with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for his assistance with the data analysis, and we are grateful for the unwavering support of the Urban Indian Health Institute and the Seattle Indian Health Board throughout this project.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons—14 states, January–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(49):1853–1856. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(24):759–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 among American Indian and Alaska Native persons—23 states, January 31–July 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(34):1166–1169. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6934e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urban Indian Health Commission. Invisible Tribes: Urban Indians and Their Health in a Changing World. Seattle: WA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Census Bureau. The American Indian and Alaska Native population: 2010. Available at. 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/dec/c2010br-10.html

- 7.Jaimes MA. The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization, and Resistance. Boston, MA: South End Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.James RD, West KM, Claw KG, et al. Responsible research with urban American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(12):1613–1616. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubay L, Aarons J, Brown KS, Kenney GM.2022. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-risk-exposure-coronavirus-work-varies-race-and-ethnicity-and-how-protect-health-and-well-being-workers-and-their-families

- 10.Urban Indian Health Institute. 2021. https://www.uihi.org/old-uihp-profiles-page

- 11.Hill L, Artiga S.2021. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/covid-19-vaccination-american-indian-alaska-native-people

- 12.Silberner J. COVID-19: how Native Americans led the way in the US vaccination effort. BMJ. 2021;374:n2168. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes key action in fight against COVID-19 by issuing emergency use authorization for first COVID-19 vaccine. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes additional action in fight against COVID-19 by issuing emergency use authorization for second COVID-19 vaccine. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-additional-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-second-covid

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA issues emergency use authorization for third COVID-19 vaccine. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-emergency-use-authorization-third-covid-19-vaccine

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/reporting-pui.html

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NNDSS supports the COVID-19 response. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/action/covid-19-response.html

- 18.Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. Vital Health Stat 2. 2014;(166):1–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Census Bureau. 2021. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

- 20.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(4):364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race/data_documentation.htm

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 incidence by age, sex, and period among persons aged <25 years—16 US jurisdictions, January 1–December 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(11):382–388. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7011e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring incidence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, by vaccination status—13 US jurisdictions, April 4–July 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(37):1284–1290. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urban Indian Health Institute. For the love of our people. 2022. https://forourpeople.uihi.org

- 25.Melkonian SC, Jim MA, Haverkamp D, et al. Disparities in cancer incidence and trends among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 2010–2015. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(10):1604–1611. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goins RT, Pilkerton CS. Comorbidity among older American Indians: the native elder care study. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2010;25(4):343–354. doi: 10.1007/s10823-010-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denny CH, Holtzman D, Goins RT, Croft JB. Disparities in chronic disease risk factors and health status between American Indian/Alaska Native and White elders: findings from a telephone survey, 2001 and 2002. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):825–827. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obinna DN. “Essential and undervalued: health disparities of African American women in the COVID-19 era.”. Ethn Health. 2021;26(1):68–79. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2020.1843604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-takes-additional-actions-use-booster-dose-covid-19-vaccines

- 30.Brooks JT, Butler JC. Effectiveness of mask wearing to control community spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2021;325(10):998–999. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon S, Joshi AD, Lo CH, et al. Association of social distancing and face mask use with risk of COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3737. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24115-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(24):759–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labgold K, Hamid S, Shah S, et al. 2020. [DOI]

- 34.Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N, et al. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S303–S311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arias E, Xu J, Curtin S, Bastian B, Tejada-Vera B. Mortality profile of the non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native population, 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70(12):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]