Abstract

There is limited information regarding the morphometric relationships of panicle traits in oat (Avena sativa) and their contribution to phenology and growth, physiology, and pathology traits important for yield. To model panicle growth and development and identify genomic regions associated with corresponding traits, 10 diverse spring oat mapping populations (n = 2,993) were evaluated in the field and 9 genotyped via genotyping-by-sequencing. Representative panicles from all progeny individuals, parents, and check lines were scanned, and images were analyzed using manual and automated techniques, resulting in over 60 unique panicle, rachis, and spikelet variables. Spatial modeling and days to heading were used to account for environmental and phenological variances, respectively. Panicle variables were intercorrelated, providing reproducible archetypal and growth models. Notably, adult plant resistance for oat crown rust was most prominent for taller, stiff stalked plants having a more open panicle structure. Within and among family variance for panicle traits reflected the moderate-to-high heritability and mutual genome-wide associations (hotspots) with numerous high-effect loci. Candidate genes and potential breeding applications are discussed. This work adds to the growing genetic resources for oat and provides a unique perspective on the genetic basis of panicle architecture in cereal crops.

Keywords: archetype analysis, Avena, GWAS, high-throughput phenotyping, image analysis, NAM population, panicle, plant architecture, spikelet, TILLING population, Plant Genetics and Genomics

Introduction

The genus Avena comprises a group of mostly annual grasses that represent a series of ploidy levels. Grown as a source of food, feed, and cosmetics, cultivated oat (Avena sativa) is a major cereal crop with diverse end products. For instance, oat is marketed as being a heart-healthy food because of its high soluble fiber (β-glucan) content and is a valued ingredient in cosmetics for its naturally occurring avenanthramides. Globally, oat production has suffered in the last decade due to competition for other high-value cereal crops with better yield, agronomic properties, and disease resistance. In addition, oat production is increasingly being challenged by both a rapidly changing environment and pathogen population, which indicates that fundamental genetic improvements must be made to ensure its relevance in future markets.

Spring oat is an allohexaploid (Murphy and Hoffman 1992), consisting of 3 subgenomes (A, C, and D) with 7 chromosomes each and an entire genome size of 11–15 Gb. A unique aspect of the oat genome is that there is extensive structural variation (Chaffin et al. 2016), especially among species and ploidy levels (Kamal et al. 2022; Tinker et al. 2022). To date, chromosome-scale genome assemblies have been made publicly available of wild oat diploids, Avena atlantica and Avena eriantha (CC, 2n = 14), and Avena longiglumis (AA, 2n = 14), tetraploid Avena insularis (CCDD, 2n = 4x = 28) (Kamal et al. 2022), and cultivated hexaploid A. sativa (AACCDD, 2n = 6x = 42) (The Oat Genome project, https://avenagenome.org, https://wheat.pw.usda.gov). Soon, the genome sequences of 30 diverse oat lines (mostly A. sativa) will be released along with a gene expression atlas to assist in genetic mapping, gene characterization, and breeding (PanOat, https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/PanOat).

The breeding of oat cultivars has historically been accomplished by phenotypic evaluation with trait introgression requiring large bi-parental populations and numerous cycles of selection. Molecular marker-assisted selection accelerates this process by predicting traits with seedling genotyping. Diagnostic marker development requires a diverse germplasm base for screening and genome-wide genotyping to conduct association analysis to determine genomic regions that are associated with agronomically important traits. Oat geneticists have largely focused on evaluating diverse and segregating populations for traits related to yield, disease resistance (Esvelt Klos et al. 2017; Admassu-Yimer et al. 2018; Kebede et al. 2020), and milling properties (Doehlert et al. 1999, 2005; Carlson, Montilla-Bascon, et al. 2019; Zimmer et al. 2020; Brzozowski et al. 2022b; Esvelt Klos et al. 2021; Tinker et al. 2022).

The most important and devastating disease of wild and cultivated oat (Avena spp.) is oat crown rust (CR), which is caused by the obligate biotrophic fungus, Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae (Pca) (Nazareno et al. 2018). Pca is a multicyclic basidiomycete fungus, with the asexual phase occurring in oat and the sexual phase in buckthorn (Rhamnus spp.). Infection of Pca on oat gives rise to yellow-orange pustules containing newly formed urediniospores, accompanied by chlorotic and/or necrotic regions on host leaves. During the summer, urediniospores can complete multiple rounds of infection on oat, and disease incidence can be especially volatile (Miller et al. 2020), which is why breeding for durable, adult plant resistance (APR) is crucial. Other prioritized pathogens are oat stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. avenae) (Kebede et al. 2020), fusarium head blight (Bjørnstad et al. 2017), and barley yellow dwarf virus (luteoviruses) (Lin et al. 2014; Foresman et al. 2016).

Recent approaches to phenotyping and genetic selection have eased technical requirements to obtaining the breeders’ perennial goal: A superior cultivar. With the race to inexpensive, high-throughput sequencing, genomic-estimated breeding values can be obtained from prior related datasets and high-density SNP markers (Heffner et al. 2009). These values (genomic selection) are especially useful when space is limited and/or many recombinants are required for maximizing the success of multitrait indices. In general, oat genotyping has been heavily biased toward the oat 6k SNP chip (Tinker et al. 2014; Esvelt Klos et al. 2016; Bonman et al. 2019) and genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) (Poland et al. 2012; Chaffin et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2020). A new oat genotyping platform is currently under development and soon made operational, prioritizing cost per sample, even genomic distribution, and high minor allele frequency (Jason D. Fiedler, personal communication). While genomic selection is widely used in plant and animal breeding and has become more standardized (Lipka et al. 2012), high-throughput phenotyping methods are comparatively diverse (Bierman et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2020), often tailored to a single species or trait, and can be technically difficult to meaningfully implement in a breeding program. When high-throughput genotyping and phenotyping are equally informative and cost-effective at varying scales, the time to cultivar release will be radically minimized.

In general, spring oat is bred to be high-yielding with high-test weight and disease resistance. However, what has been loosely assessed are the relationships of these and other important traits with panicle morphology (Doehlert et al. 2006), and if and how it can be modulated to optimize yield. The panicle inflorescence of oat is morphologically distinct from other important cereal crops (e.g. wheat, barley, and rice) as well as morphologically diverse, because an ideotype has not been widely established (Diederichsen 2008). In general, each breeding program has, directly or indirectly, selected oat lines having equilateral, sided, or semi-sided panicles. Yet, beyond sidedness, selection on panicle traits have been paid little attention, and there is a limited body of research on exactly what morphometric relationships should be considered important in an oat breeding program. While the morphological differences of modern cereal crop inflorescences are obvious, oat panicle architecture has been loosely selected upon and is inherently more diverse. The Poaceae undoubtedly share common morphological features that are regulated by similar genes with similar function (paralogs), yet both allopolyploidization and subfunctionalization obfuscate direct transferability of gene–function relationships (Santantonio et al. 2019), so oat may well have evolved unique gene regulatory factors controlling panicle morphology and architecture.

The objectives of this study were to (1) develop representative models of panicle growth and development using a large image dataset comprising 10 multiparent oat mapping populations, (2) define distinct reference cases of panicle form from which comparisons of likeness are made (panicle archetypes), (3) assess morphometric relationships of panicle variables and their contribution to growth and disease incidence, and (4) identify genomic regions and candidate genes most associated with phenotypic variation.

Materials and methods

Population development

The A. sativa cv. “Otana” (CI 9252) purebred milling line served as a common parent to a total of 9 multiparent families (Table 1) whose 9 parents were selected based on genetic diversity and APR for oat CR. For a full description of this population, see Nazareno et al. (2022). These families are referred to as the O × S population.

Table 1.

Summary of O × S (n = 1,431) and OT30171 TILLING (n = 1,297) populations.

| Family ID | N | Generation | Female parent | Male parent | Male parent origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O × S population | |||||

| O035 | 135 | F9 | CI 9252 | CI 7035 | Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| O412 | 122 | F12 | CI 9252 | PI 263412 | Algeria |

| O416 | 190 | F10 | CI 9252 | CI 9416 | South Carolina, United States |

| O616 | 178 | F12 | CI 9252 | PI 260616 | Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil |

| O706 | 126 | F9 | CI 9252 | CI 4706 | Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| O712 | 171 | F7 | CI 9252 | CI 1712 | Ontario, Canada |

| O733 | 167 | F10 | CI 9252 | PI 189733 | Pichincha, Ecuador |

| O887 | 141 | F12 | CI 9252 | PI 266887 | Portalegre, Portugal |

| O8000 | 201 | F10 | CI 9252 | CI 8000 | Arkansas, United States |

| TILLING population | |||||

| OT3071 | 1,297 | M7 | OT3071 | OT3071 | Univ. Saskatchewan, Canada |

The A. sativa OT3071 purebred milling line (generously provided by Aaron Beattie, University of Saskatchewan, Canada) was selected to generate a mutant population (Table 1) by imbibing seeds with a 1.2% (w/v) ethyl methanesulfonate solution in tubes on a shaker set at 150 rpm for 7 h at 23°C. Seeds were sown in the greenhouse and self-pollinated to the M7 generation. This family is referred to as the TILLING population.

DNA isolation, sequencing, and variant calling

The O × S families were genotyped along with their parents (n = 1,521) via GBS (Elshire et al. 2011) using both PstI and MspI restriction enzymes, as described in Poland et al. (2012), conducted at the USDA-ARS Cereal Genotyping Lab at Edward T. Schafer Agricultural Research Center (Fargo, ND). Pooled libraries were sequenced with Illumina HiSeq 4000 or NovaSeq 6000 in 2 × 150 bp paired-end mode to an average depth of 2 million reads per line. Reads were quality filtered and trimmed with bbduk (BBTools, https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools) and aligned to the A. sativa OT3098 reference genome assembly (OT3098 v2, PepsiCo, https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/jb?data=/ggds/oat-ot3098v2-pepsico) with Bowtie 2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012). The genome analysis toolkit (GATK4) (Best Practices, https://gatk.broadinstitute.org) was used to process read alignments into population-level variant calls. SNPs and indels were filtered in VCFtools (minDP = 5, max-missing = 0.5, maf = 0.01, maq = 30, baq = 20) and duplicates merged with BCFtools norm (Danecek et al. 2011, 2021). GBS read alignments and variant filtration were performed on SCINet high-performance computing clusters (Ceres SCINet, https://scinet.usda.gov/).

In silico gene annotations of the OT3098 v2 reference genome have provided a means for candidate gene searches via blastnAltschul et al. (1990) based on the extensive genomics databases developed for Triticeae and Avena (e.g. GrainGenes, https://www.wheat.pw.usda.gov). Candidate gene searches were performed first by intersecting marker positions and gene ranges from the latest annotation, where nearly 5% of markers were found to be inside coding regions of at least 1 gene model. Nearby genes from top associations (±100 kb from start or stop codon) were considered, primarily selected according to biological relevance to the trait of interest.

Field design

The O × S and TILLING populations were planted in double hill plots at North Dakota State University (Fargo, ND) in May 2021. Within row and between row spacing was 0.5 m. Both populations were planted in augmented design with parents and checks represented at least once per row (Supplementary Fig. 1). The 2 trials were separated by a 1-m buffer row of oats. Check varieties in the O × S trial were HiFi and Maida, and checks in the TILLING trial were HiFi, ND-Heart, ND131603, ND141327, Killdeer.

Field measurements

Days to heading (HD) was considered the number of days after planting for at least 50% panicles in a plot to be fully emerged from flag leaves. Chlorophyll content (SPAD) was measured in the middle of the growing season at panicle emergence on the widest part of the flag leaf using a Minolta 502+ SPAD meter (Konica Minolta, Gainesville, FL). Plot height (HT) was measured at physiological maturity, 1 week before harvest. Lodging (LDG) was measured twice, at 4 weeks (LDG1, continuous) and 1 week (LDG2, ordinal) prior to harvest, and visually assessed as a plot average, such that a value of 100 or 5 indicates complete lodging, respectively. Lodging was not measured in the TILLING trial due to time constraints.

Mean oat CR disease variables for the O × S population used in this study were provided by Nazareno et al. (2022), collected 2017 to 2020 in field conditions. Coefficient of infection was calculated as the product of % disease severity (continuous) and reaction class (ordinal) (Lin et al. 2014).

Feature extraction from panicle images

For each genotype, a representative panicle was sampled 3 weeks before harvest, placed in a sheet protector, and stored at 4°C until imaged using a benchtop ImageFormula FBS102 laser scanner (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). Raw TIFF images (600 dpi) were output in the same dimensions to avoid the requirement of a reference scale, then binary transformed and inverted in ImageJ version 1.53p (Schneider et al. 2012). Images were processed on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, with an 18-core Intel Xeon E5-2699v3 CPU, NVIDIA 12GB Titan V GPU, and 128GB DDR4 2,133 MHz ECC RAM. All panicle variables were measured in ImageJ or R version 4.1.0 (R Core Team 2021). Panicle architecture modeled in this study was adapted from those developed by Carlson et al. (2021). Panicle variable abbreviations and calculations are further described in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2.

Trait abbreviations and their descriptions, with mean and standard error (± SE), coefficient of variation (CV%), and heritability (h2) for both O × S and TILLING populations.

| Trait | Description | Units | O × S | TILLING | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | CV% | h 2 | Mean ± SE | CV% | h 2 | |||

| Growth and physiology | ||||||||

| HD | Heading date | dap | 62.18 ± 0.24 | 14.4 | 0.39 | 45.13 ± 0.13 | 10.2 | 0.41 |

| SPAD | Chlorophyll content | — | 57.43 ± 0.14 | 9.20 | 0.53 | 61.68 ± 0.15 | 8.90 | 0.35 |

| HT | Plant height | cm | 81.64 ± 0.29 | 13.6 | 0.58 | 86.56 ± 0.20 | 8.20 | 0.66 |

| LDG1 | Lodging severity, early | % | 1.77 ± 0.15 | 313 | 0.92 | — | — | — |

| LDG2 | Lodging severity, late | 0–5 | 2.87 ± 0.03 | 37.4 | 0.54 | — | — | — |

| Panicle variables | ||||||||

| PD | Panicle diameter | cm | 10.9 ± 0.09 | 31.6 | 0.55 | 8.61 ± 0.07 | 30.8 | 0.67 |

| PH | Panicle height | cm | 17.57 ± 0.12 | 24.9 | 0.44 | 14.64 ± 0.07 | 17.9 | 0.34 |

| PA | Panicle area | cm2 | 100.9 ± 1.37 | 51.7 | 0.44 | 65.16 ± 0.77 | 42.4 | 0.57 |

| PC | Panicle circularity | 0–1 | 0.35 ± 0.004 | 37.1 | 0.50 | 0.37 ± 0.003 | 31.1 | 0.64 |

| Rachis variables | ||||||||

| RL | Rachis length | cm | 17.81 ± 0.11 | 23.0 | 0.40 | 15.32 ± 0.07 | 16.1 | 0.56 |

| RD | Peduncle diameter | cm | 0.5 ± 0.001 | 10.1 | 0.43 | — | — | — |

| MXINL | Max internode length | cm | 5.45 ± 0.03 | 21.2 | 0.28 | 4.34 ± 0.02 | 14.9 | 0.40 |

| MINL | Mean internode length | cm | 4.37 ± 0.03 | 21.0 | 0.23 | 3.43 ± 0.26 | 14.3 | 0.49 |

| NN | Rachis node number | # | 5.24 ± 0.03 | 20.4 | 0.63 | 5.94 ± 0.05 | 13.1 | 0.26 |

| NPCM | Rachis nodes cm−1 | # | 0.3 ± 0.002 | 21.7 | 0.57 | 7.03 ± 0.08 | 38.4 | 0.41 |

| RB1L | Rachis branch length | cm | 8.73 ± 0.09 | 40.6 | 0.57 | 7.03 ± 0.08 | 38.4 | 0.34 |

| RB1A | Rachis branch angle | ∘ | 49.98 ± 0.47 | 35.7 | 0.64 | 43.16 ± 0.47 | 38.9 | 0.20 |

| RCA | Rachis curvature | ∘ | 174.8 ± 0.17 | 3.80 | 0.91 | 174.5 ± 0.15 | 3.10 | 0.02 |

| NDEV | Rachis node deviance | — | 1.04 ± 0.09 | 319 | 0.97 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 216 | 0.74 |

| Spikelet variables | ||||||||

| SN | Spikelet number | # | 35.0 ± 0.39 | 42.9 | 0.43 | 42.37 ± 0.38 | 32.0 | 0.65 |

| SNU | Upper spikelet number | # | 12.18 ± 0.15 | 45.6 | 0.26 | 16.05 ± 0.17 | 37.0 | 0.07 |

| SNL | Lower spikelet number | # | 23.02 ± 0.28 | 46.2 | 0.30 | 25.86 ± 0.24 | 33.9 | 0.01 |

| MSD | Mean spikelet diameter | cm | 0.90 ± 0.002 | 10.4 | 0.63 | 0.8 ± 0.002 | 7.40 | 0.43 |

| MSL | Mean spikelet length | cm | 1.44 ± 0.004 | 10.6 | 0.66 | 1.26 ± 0.003 | 8.20 | 0.53 |

| MSA | Mean spikelet area | cm2 | 35.01 ± 0.20 | 22.1 | 0.68 | 27.65 ± 0.12 | 16.1 | 0.38 |

| MSP | Mean spikelet perimeter | cm | 4.44 ± 0.02 | 15.5 | 0.66 | 3.75 ± 0.01 | 12.2 | 0.36 |

| SSA | Sum spikelet area | cm2 | 1247 ± 11.3 | 34.4 | 0.48 | 1248 ± 10.42 | 30.0 | 0.59 |

| SSP | Sum spikelet perimeter | cm | 156.6 ± 1.51 | 36.7 | 0.51 | 165.9 ± 1.40 | 30.4 | 0.58 |

| SECC | Spikelet eccentricity | — | 0.84 ± 0.001 | 6.40 | 0.58 | 0.84 ± 0.001 | 5.50 | 0.32 |

| SSOL | Spikelet solidity | 0–1 | 0.82 ± 0.001 | 4.90 | 0.59 | 0.83 ± 0.001 | 4.70 | 0.37 |

| SCIR | Spikelet circularity | 0–1 | 0.38 ± 0.001 | 12.7 | 0.57 | 0.42 ± 0.001 | 11.5 | 0.31 |

| Panicle kite variables | ||||||||

| KD | Kite diameter | cm | 9.5 ± 0.10 | 39.2 | 0.53 | 7.5 ± 0.08 | 40.0 | 0.37 |

| KH | Kite height | cm | 17.81 ± 0.11 | 23.0 | 0.40 | 15.32 ± 0.07 | 16.1 | 0.56 |

| KDH | Kite diameter height | cm | 4.13 ± 0.06 | 51.7 | 0.30 | 4.08 ± 0.05 | 42.2 | 0.19 |

| KA | Kite area | cm2 | 88.57 ± 1.28 | 55.1 | 0.44 | 59.15 ± 0.78 | 47.3 | 0.47 |

| KP | Kite perimeter | cm | 42.08 ± 0.27 | 24.0 | 0.56 | 35.22 ± 0.18 | 18.5 | 0.53 |

| KCIR | Kite circularity | 0–1 | 0.58 ± 0.003 | 19.2 | 0.58 | 0.56 ± 0.004 | 22.9 | 0.32 |

| KDEN | Kite density | — | 14.32 ± 0.15 | 40.0 | 0.77 | 21.37 ± 0.20 | 32.9 | 0.63 |

| CHA | Convex hull area | cm2 | 124.6 ± 1.74 | 53.2 | 0.40 | 82.76 ± 0.95 | 41.3 | 0.01 |

| CHP | Convex hull perimeter | cm | 92.89 ± 0.81 | 33.3 | 0.45 | 77.16 ± 0.62 | 28.9 | 0.01 |

| CCIR | Convex hull circularity | 0–1 | 0.2 ± 0.003 | 52.3 | 0.45 | 0.19 ± 0.002 | 45.7 | 0.03 |

| CDEN | Convex hull density | — | 13.44 ± 0.26 | 72.2 | 0.27 | 18.75 ± 0.34 | 65.5 | 0.40 |

Spikelet number (SN), as well as mean and sum diameter, area (SSA), perimeter (SSP), and circularity () were obtained first by removing outlier objects in ImageJ (px = 8, threshold = 0), and any whitespace around the edges of scanned images with autocrop (border = 0), which served as input to analyze_objects (tolerance = 5, extension = 1, index = B, invert = true, method = watershed, lower size = 500, upper size = 6,000) in pliman version 1.0.0 (Olivoto et al. 2022), after which pixel values were converted to cm units. Since the watershed algorithm is somewhat imperfect in this application, only segmented objects (spikelets) were considered in mean calculation that were not or did not contain the rachis, peduncle, partial spikelets, or debris (area = 0.25–1.25 cm2, major axis = 0.15–2.75 cm, max eccentricity = 2.5).

Several well-known RGB indices were calculated from mean values of individual segmented spikelets. Since these indices are autocorrelated (Supplementary Table 2), the most informative indices from GWAS results are discussed. Informative RGB indices were: excess green (, Woebbecke et al. 1993), excess green excess red difference index (), normalized green blue difference index [, Hunt et al. 2005], normalized red–blue difference index [, Peñuelas et al. 1994], normalized green–red difference index [, Gitelson et al. 2002], and visible atmospherically resistant index [, Gitelson et al. 2002]. The formulas and descriptions of all RGB indices used can be found in Supplementary Table 1 and a complete list of GWAS results in Supplementary Table 3.

Rachis length (RL), primary rachis internode length, and primary branch length (RB1L) were calculated via Euclidian distance: . Vectors recorded in ImageJ were (1) terminal apex of lower panicle branch, (2) first rachis node, (3) second rachis node, and (4) terminal apex of the rachis. Since the rachis of scanned panicles were imperfectly aligned to image borders, vectors were rotated around the first rachis node, so the first and second rachis nodes had the same y scalar. Rachis node number (NN) was measured manually in ImageJ, whereas the sum of point distances between node vectors was considered sum internode length (SINL). Mean rachis internode length (MINL) was calculated using the first 3 internodes from the first rachis node. Deviance from the linear regression of rachis node (x) vectors and rachis axes (y) was termed as node deviance (NDEV), akin to rachis curvature. The number of rachis nodes per unit length of the rachis was calculated as NN/SINL (nodes cm−1 rachis). Peduncle diameter (PED) was manually measured 1-cm beneath the first rachis node in ImageJ. Kite density (KDEN) was calculated as SSA/KA.

The 2-D panicle kite models introduced in this study were developed as quantitative assessments of panicle shape based on the fewest number of morphometric variables. Panicle diameter (PD and KD) was considered the distance between the apices of the 2 longest branches and panicle height (PH and KH) as the distance from the first node to the terminal spikelet. Panicle kite area (KA) was calculated as (KD × KH)/2. Panicle kite diameter height (KDH) was calculated as the difference of y scalars representing the terminal apex of the lower branch and the first rachis node. Panicle kite branching angle (KBA) was calculated as the angle between the 2 vertices: (1) first primary branch apex → first rachis node and (2) first rachis node → second rachis node. Panicle erectness or rachis angle (RCA) was assessed by calculating the angle between the 2 vertices: (1) first rachis node → second rachis node and (2) second rachis node → terminal spikelet of rachis, such that indicates skew. Panicle convex hull area (CHA), perimeter (CHP), and circularity (CHC) were estimated from postfiltered spikelet vectors using ployarea. Panicle area (PA) was considered the total area from inverted binary images, and panicle density and convex hull density (CHDEN) as SSA/PA and SSA/CHA, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in the open-source statistical computing platform, R version 4.1.0 (R Core Team 2021). Pairwise Pearson correlations were performed using cor.test and principal components analysis (PCA) with prcomp and variables projected with biplot. Archetypal analysis of oat panicle architecture was performed with stepArchetypes (k = 1:9, reps = 5) in archetypes (Eugster and Leisch 2009), using the 2 ratios as input variables: (1) panicle diameter to panicle length and (2) panicle diameter length to panicle length, a morphometric model first introduced in Carlson et al. (2021). Residual sum of squares (RSS) was used to estimate archetype number (k = 5). Pairwise t-tests were performed for each panicle archetype (1–5) to identify significant differences of family proportions (adj. P < 0.01), using the Euclidean distance of each genotype to that of the 5 archetypes (extremes, AD1–AD5) identified for the 2 ratios described. No transformations were used in archetypal analyses. For the genome-wide association of panicle archetypes, analyses were performed using the point distance of the panicle kite ratio vector ( and ) for each individual line to that of each archetype vector, AD1 to AD5. Pairwise t-tests were also performed to identify significant differences (adj. P < 0.01) in rachis NN (by family) separately for rachis nodes 3–8. ANOVA was used to test (P < 0.05) for the interaction of total rachis NN and rachis internode proportion variables. Orthogonal least squares (OLS) and Type II ranged major axis regression was performed in lmodel2 (Legendre and Legendre 2012) to estimate coefficients. Panicle RGB distances were calculated using 2 bins for each RGB channel with getHistList (omit black background: lower = 0 and upper = 0.1, hsv = false) and getColorDistanceMatrix with default parameters in colordistance (Weller and Westneat 2019).

Variance components were estimated separately for the O × S and TILLING populations. To account for spatial variation, SpATS was used to model spatial trends as 2-dimensional P-splines (nseg = 10/20, ANVOA = true) (Rodríguez-Álvarez et al. 2018) using column and row as covariates in the P-spline model (control = 0.001). Genotype was considered as random, and both check and block (tray) as fixed. For the O × S trial, genotypes were grouped by family, assuming different genetic variance for each. Predicted genotypic values were used in GWAS with and without normalizing transformation. Optimal transformations of these values were estimated using bestNormalize (orderNorm = false, k = 10, reps = 5, standardize = true, eps = 0.002), based on the Pearson test statistic for normality, in bestNormalize (Peterson and Cavanaugh 2020). Visual inspection of quantile–quantile (QQ) plots (observed ) vs. expected ) was also used to report best normalizing transformation. While most traits did not require transformation, unique techniques were: and log, where , as well as arcsinh, Box-Cox, and Yeo-Johnson transformations. Phenotypic correlation networks were estimated separately for the O × S and TILLING populations, using a pairwise Pearson correlation matrix (threshold: ) serving as input to graph_from_adjacency_matrix (mode = undirected, weighted = true, diag = false) for graph construction, number of network edges with degree (mode = all, loops = false), and number of blocks based on vertex connectivity using cohesive_blocks in igraph (Csardi and Nepusz 2006).

Genome-wide association was conducted for 60 field and panicle traits collected from 1,450 O × S individuals, including the parents. A total of 83 O × S progeny individuals were dropped prior to GWAS, due to excess missingness >0.85 or heterozygosity >0.35. A total of 81,016 markers passed filtering requirements (maf = 0.01, max site missingness = 0.5, max site heterozygosity = 0.35). To control for population structure (Q) and kinship (K), the mixed linear model (MLM) (Yu et al. 2006) association method was implemented in GAPIT version 3 (Lipka et al. 2012) using EMMAX (Kang et al. 2010) to calculate significance levels. For GWAS, the following equation was used:

where Y is the phenotype vector; X represents SNP genotype vectors; P is a matrix containing the first 5 principal components (PCs) (SNP fraction = 0.65); and HD represents a vector of the heading date (HD). For genotypic effects, (0, ), where K is a kinship matrix accounting for pairwise relatedness between lines, estimated via A.mat (method = EM, tolerance = 0.02, shrinkage = false) in rrBLUP version 4.6.1 (Endelman 2011), and residual effects as (0, ). Marker-based heritability was calculated as , where is genetic variance and is the residual variance. Significant associations from MLM results were reported using the false discovery rate (FDR) adj. P = 0.01. To identify the best hits in high-LD regions, a multilocus model was also implemented via the FarmCPU method (Liu et al. 2016), using the same 5 PCs and kinship matrix (FDR adj. P = 0.01). Association networks were constructed using graph_from_dataframe (links = traits, target = chromosomes, directed = false) for graph construction and degree (mode = all, loops = false) for network edges in igraph (Csardi and Nepusz 2006). GWAS was performed on SCINet high-performance computing clusters (Ceres SCINet, https://scinet.usda.gov/).

Results

Automatic and manual measurement of oat panicle features from 2,993 images yielded a rich dataset consisting of over 60 unique variables (Table 2, Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Data set 1, and Supplementary Dataset 2). This study describes the diversity and heritability of panicle archetype and the morphometric relationships of corresponding variables and other field-collected traits in 10 diverse, multiparent oat mapping populations. In addition, genome-wide associations were assessed in the O × S population using high-density GBS data aligned to the most recent annotated A. sativa OT3098 v2 reference genome. This is the first study in oat that applies both high-throughput phenotyping and genotyping to characterize genomic regions (Supplementary Table 3) and candidate genes (Table 3) associated with variation in panicle, growth, and disease traits across diverse pedigrees.

Fig. 1.

Morphometric variables and pairwise relationships. Illustrations (a) of panicle, rachis, and spikelet morphometric variables derived from panicle images. Pearson pairwise correlation matrix (b) of variables used in GWAS and (c) PCA biplot of the first 2 PCs and % variance explained by each. The size and intensity of each filled circle in the correlation matrix indicates the strength and direction of the relationship (P > 0.05 are not shown), respectively, as indicated in the legend.

Table 3.

Genes of interest located within genome-wide association hotspots.

| Oat genea | Pos (Mb) | No.b | Gene ID | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Dg0001988 | 318.38 | 1 | MYB36 | Endodermal differentiation | Liberman et al. (2015) |

| 4Dg0001989 | 318.41 | 1 | RS1 | Shoot organ patterning | González-Grandío et al. (2017) |

| 4Dg0002014 | 319.53 | 2 | JUB1 | Gibberellin homeostasis | Dong et al. (2022) |

| 7Ag0000916 | 74.974 | 1 | HPSE3 | Cell surface degrading enzyme | Fux et al. (2009) |

| 7Cg0000287 | 24.875 | 1 | BX8 | Cytokinin glycosyltransferase | Li et al. (2015) |

| 7Cg0000313 | 26.154 | 1 | EXPA9 | Cell wall loosening/extension | Shin et al. (2005) |

| 7Cg0000343 | 27.869 | 1 | AP2-3 | Spikelet/meristem determinacy | Vavilova et al. (2020) |

| 7Cg0000464 | 33.154 | 2 | GALT6 | Arabinogalactan glycosylation | Basu et al. (2015) |

| 7Cg0000465 | 33.166 | 2 | NOV | Auxin controlled cell patterning | Tsugeki et al. (2009) |

| 7Dg0003379 | 510.71 | 4 | WAK2/3/5 | Cell expansion/coordination | Kohorn and Kohorn (2012) |

Gene names truncated, omitting “AVESA.00001b.r3.” preceding A. sativa OT3098 v2 chromosome and gene model identifiers (v3 annotation).

Number of nearby genes with same annotation.

Archetypal analysis of the oat inflorescence

The heritability of panicle and spikelet variables were moderately high in both populations; however, compared to O × S families, there was limited genetic variance () for some traits in the TILLING population (e.g. upper: lower spikelet ratio and rachis curvature/skew) (Table 2). Likewise, the TILLING population displayed a lower CV (%) for nearly all morphological, growth, and disease variables compared to the O × S population. Nevertheless, both the TILLING and O × S were essential to modeling oat panicle architecture by their sheer size in numbers as well as genetic and phenotypic diversity.

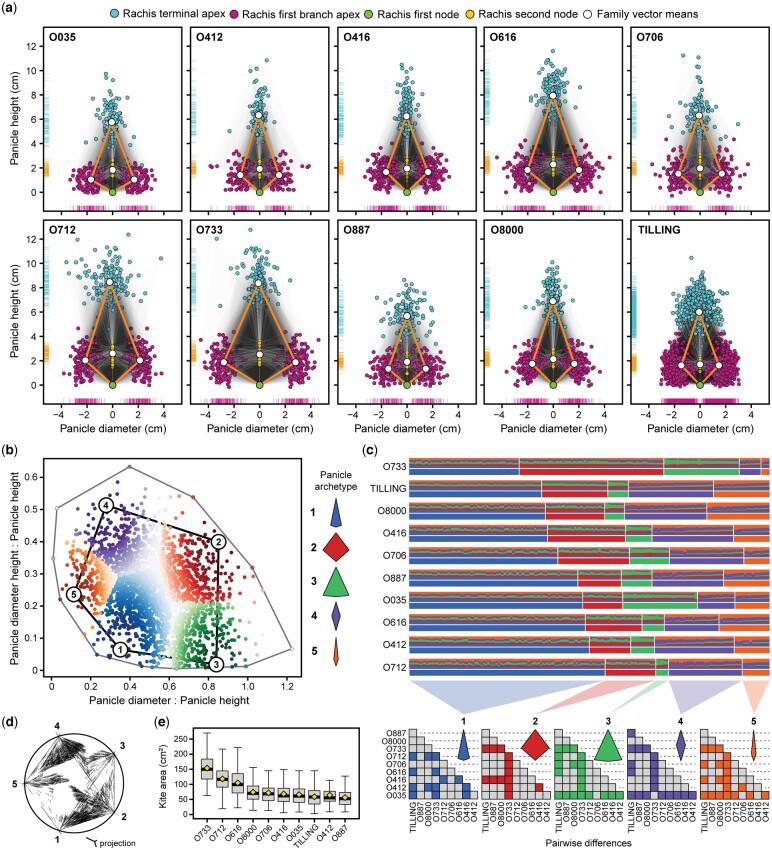

The techniques used here to identify oat panicle archetype were based on the ratio of the panicle diameter to height and the height at the maximum diameter to height (i.e. kite ratio) (Figs. 1a and 2). Using stepwise selection to estimate the most representative number of archetypes, RSS was minimized at k = 5 (Fig. 2, b and c). Panicle archetypes (extremes) were modeled as 2-D kites (Carlson et al. 2021) and can be generalized as common leaf shapes: acuminate or spear (archetype 1), rhomboid (archetype 2), deltoid (archetype 3), lanceolate (archetype 4) and subulate (archetype 5) (Fig. 2c). Based on family means, archetype 1 was most frequently represented (Fig. 2, b–d), yet there was still substantial variation within and among families in kite ratios and archetype proportions (Fig. 2, d and e). For instance, the family with the greatest mean 2-D kite area, O × S family O733 (Fig. 1f), was almost exclusively assigned to archetypes 1–3, having few lines with narrow or compact panicles (archetypes 4 and 5), whereas deltoid-like archetype 3 was not well-represented in either TILLING and O8000, but had the greatest archetypes 4 and 5 proportions.

Fig. 2.

Archetypal analysis. Overlapping panicle kite models (a) of genotypes from the O × S and TILLING populations. The x-axis positions of lower rachis branch apex, terminal rachis apex, first rachis node, and second rachis node are scaled by the first rachis node. Large points connected by segments (panicle kite model) each represent family means of corresponding variables. Scatterplot of (b) panicle diameter (x-axis) and panicle diameter height (y-axis) ratios with panicle height of all oat lines included in this study. Panicle archetype proportions (c) by family individual, ordered by archetype and minimum distance within each archetype. Pairwise t-tests were performed for archetypes (individual distance to archetypes) across families, wherein only significant pairwise differences (adj. P < 0.01) are filled. Simplex plot (d) depicting k archetype projections of all individuals and (e) panicle kite area (cm2) distributions, with family means represented by yellow diamonds.

The most significant GWAS results for kite area and PA surrounded the top associated marker on chromosome 7C at 2.486 Mb, from 2.46 to 2.49 Mb (Supplementary Table 3). Although kite and panicle diameter variables only had significant marker associations in the same region, associations for kite height and panicle height (RL) were represented on all 3 chromosome 7 subgenomes, with similar peak positions (7A: 74.972 Mb, 7C: 17.864 Mb, and 7D: 510.660 Mb). In general, there was limited power to detect genome-wide associations for archetype variables (Euclidean distance to archetypes, i.e. extremes). While most were weakly associated, significant associations could most often be found in similar genomic regions of panicle size and density variable associations.

Rachis allometry and magnitude of curvature

The rachis node vectors of all inbred lines were manually recorded in ImageJ. The sum distance between node vectors (internode lengths) was deemed sum internode length (i.e. RL) and each internode divided by this sum, its internode proportion (Fig. 3a). The total number of rachis nodes was divided by the sum internode length to retrieve the number of nodes per unit length of rachis (rachis nodes cm−1) (Fig. 3, a–c). Rachis nodes cm−1 was akin to the cohort of panicle density variables, but not a surrogate entirely, because it did not consider 2-D kite or convex hull area (sum spikelet area/total area).

Fig. 3.

Rachis morphology and allometry. Rachis internode proportions (a) from total RL in the O × S population, ordered by number of internodes, then by first internode proportion. The right y-axis represents the number of nodes cm−1 rachis (loess span = 0.2). Internode proportions by family (b) are similarly ordered, with significant pairwise differences (adj. P < 0.01) highlighted by rachis NN in lower triangles to the right. Model II regression (c) of log10(rachis internode proportion) and log10(rachis NN), with results in the lower left legend by NN. d) Decrease in mean rachis internode proportion (y) with increasing NN (x), modeled as , with R2 values to the right. Boxplots of (e) NN, (f) RL, (g) nodes cm−1 rachis, and (h) square-root deviance of nodes along the rachis, in descending order by family means (diamonds).

Based on orthogonal least squares and type II regression methods, the slopes (m) of log10(rachis internode proportion) and log10(NN) decreased for genotypes that had developed at least 4 rachis nodes (m = −0.24 to −0.60) but between −0.70 and −0.74 for those with 5–8 nodes (Fig. 3c), which were most common. The correlation between the 2 variables exhibited the same inverse relationship. There was no interaction between the total number of nodes developed and individual rachis internode proportions (ANOVA P = 0.6). This relationship also indicated size independence of both proximal and distal rachis internodes, but a dependence of interior internodes. Importantly, a consistent pattern arose as the number of nodes increased: For every addition of a node (x) to the rachis, the mean sequential rachis internode proportion (y) was equivalent to , with essentially perfect fit () (Fig. 3d). Based on this growth formula, irrespective of NN or panicle density, the placement of nodes along the rachis can effectively be modeled as such.

The TILLING population surpassed all O × S families in mean rachis NN (Fig. 3e) and mean rachis nodes cm−1, likely because the lines were derived from an improved milling line, however, there were O × S progeny individuals that did exceed 0.5 nodes cm−1 (Fig 3g). Deviance of node vectors along the length of the rachis represented here the magnitude of rachis curvature, which was inversely correlated () with the inner angle derived from the first (lowest) rachis branch and terminal apex from 2-D kite models (Fig. 1b). Sum internode length was a better estimate of the actual RL (Fig. 3f), compared to kite or panicle height variables, because the latter models did not account for instances of curvature (but optimal for calculating panicle density). There were extreme cases of rachis curvature, notably, lines in family O712, wherein the square-root rachis deviance was nearly 7 times the population mean (Fig. 3h). Overall, the mean family rachis deviance declined along with corresponding variances.

Top marker associations for rachis nodes cm−1 were on chromosomes 4D: 318.444 Mb and 7C: 24.920 Mb, whereas the best associations for density variables were 2A: 2.558 Mb (CHDEN only), 4C: 90.134 Mb (panicle density only), and 7C: 24.908 Mb (kite and panicle density) (Supplementary Table 3). Those for rachis NN were 4A: 290.699 Mb, 4D: 318.444 Mb, 7A: 70.463 Mb, and 7D: 510.660 Mb. Both rachis curvature and deviance variables had common marker associations on chromosome 1A at 313.867 and 379.413 Mb, and unique associations at 3C: 491.943 Mb and 3D: 446.638 Mb, respectively.

Spikelet size, number, and color

The number of spikelets detected were somewhat dependent on the maturity of the panicle, since panicles were scanned before being dried to reduce handling time and ensure the original panicle architecture/form was maintained. For late maturing lines, some panicles were still green at the time of scanning, and rachis branches were not completely expanded, although the panicle was completely extruded. Hence, sum spikelet variables may not have been completely representative for those lines, but likely provided accurate spikelet mean values. The mean number of spikelets per panicle was 35 and 42 in the O × S and TILLING populations, respectively (Table 2). SN was most correlated with PA (r = 0.72) and rachis NN (r = 0.66). Akin to GWAS results for rachis NN, associations for SN surrounded peak marker positions on chromosomes 4D: 318.445 Mb, 7A: 74.972 Mb, and 7D: 510.660 Mb. Associations for both mean spikelet area and mean spikelet diameter centered around 4D: 318.445 Mb, whereas both sum spikelet area and sum spikelet perimeter were near peak positions 7D: 510.660 Mb and 7A: 71.152, and spikelet ratio at 7C: 24.626 Mb. Mean spikelet circularity marker associations were restricted to 5A: 379.664 Mb and mean spikelet length at 6A: 443.017 Mb.

GWAS results for spikelet RGB indices fell into 2 main categories: (1) normalized G-R difference and (2) normalized G–B or R–B differences (Supplementary Table 3). For instance, marker associations with NRBDI surrounded the peak marker 5C: 473.757 Mb, and those with NGRDI surrounded the peak marker at 7C: 32.375 Mb, the latter of which was most similar to GWAS results for green leaf index at 7C: 30.049 Mb. In general, spikelet RGB marker associations describing G–R differences resided between 30 to 32 Mb on chr7C and R–B differences at 473 Mb on chr5C. While there was some variation as to the top associated marker for traits within each of these main groupings, it was not substantial enough to attribute additional information or elicit unique signal from GWAS.

Panicle density

Panicle density was considered as the total sum area of segmented spikelets divided by either PA or modeled as a kite or convex hull (Fig. 1a). A greater panicle kite density, calculated as sum spikelet area/panicle kite area, was more apt to identify unbranched and equilateral panicles, whereas panicle CHDEN, calculated as sum spikelet area/panicle convex hull area, identified unbranched but sided panicles. This was because panicle kite area was calculated by measuring the first primary rachis branch as the base hypotenuse of kite models, but panicle convex hull area was calculated as a polygon, fit around the object perimeter (segmented terminal spikelets) of the scanned image. By taking the log difference of panicle densities calculated with kite area and convex hull area, nearly all TILLING lines predicted as sided (log difference >2) had 69% and 77% lower circularity and kite diameter: kite height ratio, respectively. Overall, there were similar proportions of predicted branchless or near-branchless lines in the O × S (n = 32 or 2.27%) and TILLING (n = 37 or 2.95%) populations, yet the TILLING population exhibited far stronger equilateral branchless phenotypes (archetypes 4 and 5) (Fig. 2c). For both populations, panicle density decreased with an increase in panicle circularity (), yet a greater number of spikelets panicle−1 were observed for those panicles with greater circularity (r = 0.65). Kite and panicle density variables had some of the strongest marker associations in this study (Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 4b), of which both variables were most associated with genomic regions surrounding chromosome 7C: 24.627–24.908 Mb (). However, panicle CHDEN was restricted to a chromosome 7D region around 508.376 Mb, with weaker associations near 7A: 66.627 Mb. Associations for panicle circularity were nearest 7C: 24.626 Mb and 7A: 71.719 Mb.

Fig. 4.

GWAS results. Physical genomic positions of significant genome-wide associations (a) (FDR adj. P < 0.01) in the O × S population. Nearby hits were binned by 10-Mb intervals for clarity, reporting the position of the strongest association within each bin. Manhattan and QQ plots (b) of selected field agronomic and panicle variables, with genome-wise thresholds, FDR = 0.05 (light horizontal line) and Bonferroni (dark horizontal line).

Plant growth, physiology, and disease severity

Panicle variables were strongly correlated in the O × S population, as well as with the field-collected traits: heading date, chl. content, and plant height (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2, and Supplementary Fig. 2). These relationships were significantly weaker in the TILLING population, as random mutagenesis of the OT3071 founder line accounted for the observed phenotypic variation among mutagenized lines, not linkage (recombination). The use of heading date as a covariate controlled for differences in germination and floral phenology in the O × S population. In general, QQ plots for GWAS results (Fig. 4) run with the heading date covariate were modestly improved for most traits compared to those run without the covariate, as well as increased significance levels and elimination of spurious associations of weak LD.

Heading ranged from 35 to 100 dap, with a mean of 62 and 45 dap in the O × S and TILLING populations, respectively. Morphological traits most correlated with heading date were SN (r = 0.45), NN (r = 0.45), and mean spikelet area (). RGB indices correlated with heading date were primarily green—red differences, notably, EGERDI (r = 0.58). Marker associations for heading date primarily surrounded peak positions at 4D: 304.272 Mb and 7A: 72:948 Mb.

There was considerable variation in the O × S population for plant height, which had moderately high heritability (), with nearly all outliers positively skewed. Panicle variables having the strongest correlations with plant height were panicle height (r = 0.69), primary panicle internode length (r = 0.53), and SN (r = 0.62). Inverse correlations with plant height were CR severity () and panicle density (). Early lodging was also quite variable in the O × S (Table 2) and was positively associated with lodging at harvest (r = 0.26), PA (r = 0.17), panicle height (r = 0.20), and plant height (r = 0.24), and had the greatest numbers of dispersed marker associations (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Plant height was the agronomic trait most correlated with panicle morphological variables, such as total RL, rachis branch length, and internode length (Supplementary Table 2). Significant associations for plant height were on chromosomes 4A (best hit: 277.566 Mb), 4D, 7A, 7C, and 7D, and for mid-season % lodging severity on chromosomes 1A, 1D, 2A, 4D, and 6C (best hit at 6C: 77.141 Mb).

In the TILLING population, foliar chl. content (SPAD, i.e. nitrogen status) was most correlated with heading date (r = 0.23), spikelet sum area (r = 0.22) and SN (r = 0.2), as well as comparatively weak correlations (r < 0.3) with most variables in the O × S population, but the strongest was with CR severity (r = 0.20) (Supplementary Table 3). For most of the 9 O × S families, CR disease severity was inversely correlated with plant height (, range: −0.31 to −0.57), panicle height (, range: −0.2 to −0.49), and panicle perimeter (, range: −0.2 to −0.44), and positive correlations with mean spikelet diameter (r = 0.29, range: 0.1 to 0.26), and mean chl. content (SPAD) (r = 0.2, range: 0.1 to 0.33), of which the strongest associations were observed in family O035. Overall, CR severity was positively associated with chl. content (r = 0.2) and spikelet area (r = 0.28) and inversely with PA () (Fig. 1b). GWAS for SPAD was underpowered () and QQ-plots did not benefit from phenotypic normalization or HD covariate exclusion (Fig. 4b), with peak marker associations on 4A: 268.148 Mb, 4D: 318.257, and 7D: 478.965 Mb.

Association hotspots and functionally relevant genes

As expected of strong pairwise phenotypic correlations (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2), panicle and spikelet variables shared genome-wide associations of high-effect (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3, and Supplementary Fig. 4). All 3 subgenomes of A. sativa homeologous group 7 had strong associations with most panicle and spikelet variables, with hotspots represented nearest chromosome ends (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3), and tended to cluster by size, length, number, and shape. For instance, marker associations for plant height, panicle length, and spikelet size and number, and NN variables were colocated nearest to 7A: 71 Mb and 7D: 507 Mb. Morphometric variables related to panicle and kite size, density, and circularity clustered around chr7C: 26 Mb, whereas SN and rachis NN associations around 4D: 318 Mb (Fig. 4b). There were strong associations of mostly panicle size, density, and archetype variables within 7C: 24–30 Mb. In this region, 16 associations exclusive to panicle variables were at physical positions: 24.627, 24.968, and 26.03 Mb. There are a total of 33 annotated genes within this 1.4 Mb interval, of which some have annotations biologically relevant to associated variables (Table 3).

The first marker, positioned at 24.627 Mb, was most associated with panicle kite density and mean spikelet ratio ( and 9, respectively). Genes flanking this marker are a calmodulin-binding receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase 2, 2 chaperone ClpB1-like proteins, and defective in exine formation 1. Nearby, at 24.968 Mb, the second marker was most associated with panicle perimeter and circularity, as well as with total RL and rachis internode length (, maf = 0.06). Genes flanking this marker are annotated as brassinosteroid signaling kinase 5, DIMBOA UDP-glucosyltransferase BX8, zinc finger MYM-type protein 1, and dolichol-phosphate mannosyltransferase subunit 1-like. The third marker, at 26.039 Mb, was most associated with panicle and kite area and diameter, as well as panicle archetypes (, maf = 0.13). Three genes flanking this marker are a scarecrow-like protein 9, β3-glucuronyltransferase and expansin-A9. Associations for panicle kite density (, maf = 0.33) downstream this region at 27.873 Mb is directly within the coding region of an APETALA AP2-3 gene, akin to T. aestivum spelt factor protein (Q) gene (MK101279.1). In addition, genes annotated as NO VEIN (NOV) and hydroxyproline-O-galactosyltransferase 6-like were nearest the panicle kite area chr7C associated marker at 33.339 Mb. There are 2 other predicted NOV genes on A. sativa OT3098 v2 chromosome 4A: 304.07 Mb and 4D: 329.98 Mb, with 100% coverage of NOV on 7A (BLAST E-value = 0).

Marker associations for most panicle size and density variables were well-represented on chr7C, and GWAS results for spikelet size, rachis NN, RL, and field traits were most well-represented on chromosomes 4D, 7A, and 7D. Probable candidates for node and SN and related traits on chr4D are annotated as homeobox protein Rough Sheath 1 (RS1) and a Myb-related 36 at 318 Mb, as well as transcription factor JUNGBRUNNEN 1 at 319 Mb (Table 3). Three markers on chr7A were associated with 16 CR (66.627 Mb, maf = 0.30), panicle and kite (74.972 Mb, maf = 0.43), and spikelet (107.520 Mb, maf = 0.21) variables. A region associated with CR disease variables, less than 1 Mb from the marker positioned at 66.627 Mb, are 2 wall-associated receptor kinase genes, a disease resistance protein RGA2-like, and 18 other mostly uncharacterized gene models. The second marker positioned at 7A: 74.972 Mb was associated with panicle and kite variables and nearest to numerous genes related with branching and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. These genes are flavanone 3-hydroxylase, heparinase-like protein 3, cytochrome P450 84A1, and senescence-related gene SRG1.

Discussion

The present study sought to reduce the morphological complexity of the oat panicle to its primary archetypes, assess pairwise phenotypic relationships, and identify a core set of genomic loci and/or genes as putative modulators of panicle architecture, growth, and disease resistance. There were numerous panicle morphometric variables strongly correlated with plant growth and disease incidence, of which were most apt to have mutual top genome-wide associations. While the establishment of an ideotype for panicle architecture in spring oat is in its early stages, our results provide a framework for modulating the panicle to improve yield and component traits through breeding and selection.

Panicle archetypes and other models of panicle growth and development in oat

We define panicle archetypes as statistically distinct reference cases from which comparisons of likeness are made. All other individuals were assigned a proportion of membership (i.e. likeness) to each based on multiple variables, wherein archetypes are fully self-representative, having zero membership with any other archetype. In contrast, all comprise some nonzero likeness to each archetype, although the extent of this likeness may be negligible. Alternatively, an individual having equal archetype membership proportions is also free to arise, such that if projected on a 2-D plane, the Euclidean distance of the vertex to that of each archetype is approximately the same. Akin to population genetics theory, these cases would be considered admixed.

Based on archetype analysis, a total of 5 panicle archetypes were represented using panicle images from nearly 3,000 lines across 10 oat mapping populations. The inclusion of additional variables to the kite model, such as the number of segmented spikelets and spikelet area, accurately portrayed a more nuanced quantitative trait: panicle density. The relationships among the numerous variables derived from manual and automatic measurements of the oat panicle provided a reasonable picture of the morphometric landscape. In addition, input variables to derive 2-D kite models from either automatic or manual methods, were strongly correlated, and indicates that these models can be exploited with little user input.

The 2-D panicle kite models introduced in this study were successfully developed as quantitative assessments of the oat panicle based on the fewest number of morphometric variables. Diederichsen (2008) characterized panicle traits among diverse accessions of hexaploid A. sativa obtained from the Plant Gene Resources of Canada collection. Using 9 environmentally stable and qualitative morphological traits, these accessions were clustered into 118 representative groups, largely defined by source and geography. A broader sample of germplasm may elicit an increased number of panicle archetypes from what was observed in the present study, and additional characteristics may lead to higher-level morpho-groups. However, the 2-D panicle kite models were not meant to describe a confined number of groups of segregating characters, but rather, a simple quantitative model of the oat panicle having the fewest possible dimensions, using the fewest possible measurements. While 5 panicle archetypes were identified, no 2 individuals had the same input values.

Morphometric relationships are particularly informative with respect to plant biology and genetic selection. For instance, comparing modern and diverse oat germplasm, Brzozowski et al. (2022b) found that selection has directly reduced heritability of seed size in modern breeding programs, and that specialized metabolites, like avenanthramides, are positively correlated with seed size. In addition, oat seed size has been found to be negatively correlated with β-glucan content (Zimmer et al. 2021). Avenanthramide content has also been reported to be positively associated with oat CR resistance (Wise et al. 2008). In the present study, oat CR severity was found to be inversely correlated with plant height and panicle size. Relationships such as these can assist the breeder in considering the effects of latent variables as a resolvable network, rather than forfeiting them as an inevitable consequence of selection. Moreover, the effect of intensive selection on quantitative traits is essentially complex because plant biochemistry is not at all static (Hu et al. 2020; Brzozowski et al. 2022a), especially in changing environments DeWitt et al. (2022). Further, variables like panicle density can be modified, since it is essentially a function of RL, rachis branch length, and SN, but panicle architecture cannot easily be modified per se because of the apparent conformity to the oat panicle growth model.

Here, we model the development of nodes sequentially along the oat panicle rachis as , where x is the number of nodes. This model is essentially a perfect fit (), irrespective the number of nodes per unit length of the rachis (panicle density), panicle sidedness, or curvature. In comparison to wheat or barley, which have uniform rachis internode lengths, oat panicle architecture is likewise predictable in accordance with this model. As implied, modulation of oat panicle architecture in this sense could be problematic if rachis internode lengths are sequentially restricted to this principle. However, internode patterning has been successfully altered in Arabidopsis mutants (Smith and Hake 2003) as well as shoot apical meristem architecture in maize (Thompson et al. 2015). Deviations from this growth model, specifically the identification of lines with internodes of equal length, could be exploited to develop novel oat panicle types by crossing with high panicle density lines with stiff stalks (wide peduncle/culm diameter). While this dataset did not include data on grain yield, multivariable selection methods could be used to optimize panicle architecture to guide breeding efforts for yield and milling traits. It is theoretically possible to maximize the number of spikelets per unit length of the panicle rachis by index selection or multiple regression of panicle density variables (e.g. rachis nodes cm−1, panicle density, panicle circularity, and SN), given the moderately high heritability.

APR for oat CR is correlated with plant height and panicle size

The rapid evolution of oat CR has made breeding for reliable resistance especially problematic, although natural sources of nonrace specific resistance (APR) have been identified (Admassu-Yimer et al. 2018; Rines et al. 2018). APR is essentially a host-pathogen-environment interaction response, and the genetic factors in the host cell that confer APR in any 1 environment or pathogen population will be differentially weighted. For instance, if the expression of a host gene(s) posits physical barriers to pathogen attack, only in radically different (suboptimal) host environments should there be degeneration of gene function. Likewise, race-specific host resistance genes only become superfluous in new pathogen populations. Unfortunately, today, oat production is increasingly challenged by both a rapidly changing environment and pathogen population (Nazareno et al. 2018). Therefore, it is imperative the oat research community rigorously investigate the variation in phenotypic relationships and genetic basis of APR to build better breeding practices and stable, disease-resistant cultivars.

Generated by Nazareno et al. (2022), the CR data in the present study was used to seek potential morphometric relationships with APR for CR. Among O × S families, CR severity was most associated with shorter, early heading lines having a larger spikelets, smaller panicles and peduncles, and darker flag leaves. Based on these results, APR for CR is most pronounced for taller, stiff stalked plants with a more open panicle structure. However, a larger panicle corresponded with more numerous but smaller individual spikelets, so this phenotype is not particularly ideal on its own, assuming this relationship is at least partially transferrable with respect to kernel size (Doehlert et al. 2004a, 2004b). More work on this topic would add to our knowledge of the direction of oat domestication and define limits to phenotypic selection. In addition, future fine mapping and gene expression studies in these and other diverse pedigrees will better define the molecular components involved in the slow-rusting, APR phenotype.

Genome-wide association hotspots comprise genes likely attributable to variation in oat panicle size and density

A common question in linkage and association studies is whether mutual QTL or QTN (hotspots) are a result of pleiotropy, strong linkage, and/or population structure (Crowell et al. 2016; Esvelt Klos et al. 2016; Carlson, Gouker, et al. 2019). In a rice (Oryza sativa) association panel and RIL population, Crowell et al. (2016) effectively used novel phenomics techniques, which detected several subpopulation-specific associations for panicle traits, many of which were colocated (Crowell et al. 2014). Likewise, Zhong et al. (2021) identified candidate genes for panicle traits in a rice association population using phenomics. In addition, a semiautomated method for feature extraction in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) was used to validate published QTL for panicle traits Zhou et al. (2019) and surmised that colocated regions were targets of selection based on population substructure. In the present study, the top GWAS results for variables in similar trait classes were frequently colocated and comparable in allelic effect. However, the genetic basis remains uncertain until functional characterization is accomplished. Genome-wide associations for heading date and plant height within chromosomes 4A, 4D, 7A, and 7D were within the QTL LOD support intervals for the same traits identified across 5 A. sativa mapping populations (Tinker et al. 2022), which implicate VRN1 and VRN3 genetic regions as containing vernalization and meristem identity genes AP1 and FT1, respectively (Holland et al. 1997, 2002; Nava et al. 2012). Compared to QTL results for plant height in Tinker et al. (2022), unique marker associations in the O × S population were those within a hotspot region on chromosome 7C for panicle size and density traits.

The top GWAS hit for panicle density on chromosome 7C was within a DIMBOA UDP-glucosyltransferase BX8 at 24.9 Mb. In Arabidopsis, overexpression of this gene (AT5G05860) lead to reduced tolerance to both ABA and osmotic stress at the seedling stage but increased drought tolerance at maturity (Li et al. 2015), and mutants had increased water loss under drought stress due to increased stomatal aperture. Of the panicle density associations localized to this region, another candidate at 27 Mb is an APETALA AP2-3 gene, homologous to the spelt factor protein (Q) gene (Q″-5A allele, Hordeum vulgare homolog AAL50205.1). Spelt factor gene Q is regulated by mir157 and TOPLESS, and mutations in this gene have resulted in reduced plant height, compact spikes, and rachis fragility (easier threshability) Vavilova et al. (2020) and considered to be a major domestication gene in cultivated wheat (Simons et al. 2006). This is likely the same or similar locus/gene implicated in previous oat genetic mapping studies for heading date and plant height (Holland et al. 1997, 2002; Nava et al. 2012; Tinker et al. 2022).

Panicle diameter and panicle archetypes 4 and 5 had common associations surrounding an expansin-A9 gene. In rice, EXPA genes are highly expressed in developing panicles, and function to loosen and extend cell walls by disrupting bonds between cellulose and pectin (Shin et al. 2005). PA associations on chromosome 7C revealed 2 GALT6-like and 2 NOV nearby genes. Based on Arabidopsis mutant analysis, NOV was purported to be involved in vascular development, required for PIN protein expression, and auxin distribution in developing leaf primordia and meristematic tissues by mediating auxin-dependent cell specification and patterning (Tsugeki et al. 2009). In addition, application of endogenous auxin to fused roots in Arabidopsis NOV mutants induced the formation of lateral root primordia. Reduced root hair growth was also found in GALT mutants, as well as accelerated senescence and reduced seed set and seed coat mucilage (Basu et al. 2015). Involved in protein glycosylation, the GALT6-like homolog identified here is implicated in the addition of galactose in arabinogalactan (AGP) core proteins, representing the first committed step of AGP polysaccharide addition, and required for AGP function. It is possible that auxin is restricted or unspecified in meristematic tissues of the panicle inflorescence, thereby limit the initiation of primordium outgrowth of primary branches along the rachis. Unfortunately, the most extreme branchless phenotypes (archetype 5) were observed in TILLING lines, and may very well be informative, however, the population is yet to be genotyped.

Plant height, RL, internode length, NN, SN, and panicle density were strongly correlated across oat populations. Plant height, panicle RL, and SN had top associations on 7A at 74.972 Mb within the coding region of Heparanase-like protein 3, a cell surface and extracellular matrix-degrading enzyme (Fux et al. 2009). The best association for SN (and a top hit for NN) was on chromosome 7D at 510.660 Mb, nearest 4 wall-associated kinase genes: WAK1, WAK2 (2), and WAK3. WAKs function as pectin receptors, coordinating cell expansion and stress response (Kohorn and Kohorn 2012). The best associations for rachis NN and SN on chr4D was approximately 25 kb from homeobox protein RS1 (maize homolog RS1), which is most similar in sequence to Arabidopsis homeobox protein KNAT1. RS1 is a positive regulator of LOB and is expressed in vegetative meristems and floral primordia and plays a role in patterning and placement of lateral organs along the shoot axis (Becraft and Freeling 1994; Tsiantis et al. 1999). Other potential candidate genes for rachis NN on chromosome 4D are 2 copies of transcription factor JUB1. In both Arabidopsis (Wu et al. 2012) and tomato (Thirumalaikumar et al. 2018), JUB1 negatively regulates leaf senescence by modulation of H2O2 levels through the regulation of DREB2A and DELLA, eliciting tolerance to abiotic stresses. In addition, JUB1 activation by HB40 has been shown to repress shoot growth and branching by suppression of GA (González-Grandío et al. 2017; Dong et al. 2022). It is possible that allele-specific expression of JUB1 could differentially affect oat panicle architecture by regulating GA homeostasis.

If designed from these association results, the use of simple PCR-based markers could potentially reduce the reliance on valuable research resources associated with complex phenotyping of panicle traits in large, segregating oat populations. Further, fine mapping of these genomic hotspots in different populations could initiate the deployment of broadly reproducible markers, which would aid in downstream efforts of molecular cloning and characterization of candidate genes and causal loci.

A novel dataset for oat phenomics

With respect to the consequences and immediacy of global climate change, the future of plant breeding will require aggressive research and development of genomics and phenomics methodologies in order to conserve resources required to make better informed selections. In this study, a total of 106,728 spikelets were segmented in our dataset of 2,993 panicle images (mean: 35 spikelets panicle−1) and could invariably be used as a training set for spikelet detection and quantification of future image datasets using computer vision techniques (Bochkovskiy et al. 2020). For instance, in this study, EGERDI was well-correlated with heading date, using only single representative panicles measured in situ. While other important panicle-related traits, such as grain milling properties and chemical composition, could not be assessed via RGB analysis alone, it may be possible to use a combination of RGB and/or multispectral imaging methods. Further, repeated measurements of plant height, canopy density, heading date, SN, biomass, foliar diseases, and photosynthetic traits could all be assessed using unmanned terrestrial or aerial systems. Once calibrated, automation would minimize both the number of personnel and time dedicated to manual phenotyping of oat populations, which can be substantial when multiple environments are under consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Cayley Steen, John Davies, and Lauren Carlson for their excellent technical assistance and Aaron Beattie (University of Saskatchewan) for generously providing A. sativa OT3071 to generate the TILLING population. This research used resources provided by the SCINet project of the United States Department of Agriculture—Agricultural Research Service, ARS Project Number: 0500-00093-001-00-D.

Funding

This research was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture—Agricultural Research Service CRIS Project Number: 3060-21000-038-035. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Contributor Information

Craig H Carlson, Cereal Crops Research Unit, Edward T. Schafer Agricultural Research Center, USDA-ARS, Fargo, ND 58102, USA.

Jason D Fiedler, Cereal Crops Research Unit, Edward T. Schafer Agricultural Research Center, USDA-ARS, Fargo, ND 58102, USA.

Sepehr Mohajeri Naraghi, Department of Plant Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105, USA.

Eric S Nazareno, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA.

Naa Korkoi Ardayfio, Department of Plant Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105, USA.

Michael S McMullen, Department of Plant Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105, USA.

Shahryar F Kianian, Cereal Disease Laboratory, USDA-ARS, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA.

Data Availability

GBS sequence read data and metadata for all O × S progeny and parent lines are available online at NCBI SRA BioProject: PRJNA867565. Supplementary Tables 1–3 are in Supplementary File 1. Supplementary Figs. 1–4 are in Supplementary File 2. Supplementary Dataset 1 (phenotypes), Supplementary Dataset 2 (panicle images), R code, and corresponding metadata are available online at https://zenodo.org/, registered under: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7011302.

Supplemental material is available at GENETICS online.

Literature cited

- Admassu-Yimer B, Gordon T, Harrison S, Kianian S, Bockelman H, Bonman JM, Esvelt Klos K.. New sources of adult plant and seedling resistance to Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae identified among Avena sativa accessions from the national small grains collection. Plant Dis. 2018;102(11):2180–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ.. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu D, Tian L, Wang W, Bobbs S, Herock H, Travers A, Showalter AM.. A small multigene hydroxyproline-O-galactosyltransferase family functions in arabinogalactan-protein glycosylation, growth and development in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becraft PW, Freeling M.. Genetic analysis of Rough sheath1 developmental mutants of maize. Genetics. 1994;136(1):295–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman A, LaPlumm T, Cadle-Davidson L, Gadoury D, Martinez D, Sapkota S, Rea M.. A high-throughput phenotyping system using machine vision to quantify severity of grapevine powdery mildew. Plant Phenomics. 2019;2019:9209727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnstad Å, He X, Tekle S, Klos K, Huang Y-F, Tinker NA, Dong Y, Skinnes H.. Genetic variation and associations involving fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol accumulation in cultivated oat (Avena sativa L.). Plant Breed. 2017;136(5):620–636. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy A, Wang CY, Liao HYM. Yolov4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934v1, 2020.

- Bonman JM, Bockelman HE, Hijmans RJ, Hu G, Klos KE, Gironella AIN.. Evaluation of grain β-glucan content in barley accessions from the USDA National Small Grains Collection. Crop Sci. 2019;59(2):659–666. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski LJ, Campbell MT, Hu H, Caffe M, Gutiérrez L, Smith KP, Sorrells ME, Gore MA, Jannink JL.. Generalizable approaches for genomic prediction of metabolites in plants. Plant Genome. 2022a;15(2): e20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski LJ, Hu H, Campbell MT, Broeckling CD, Caffe M, Gutiérrez L, Smith KP, Sorrells ME, Gore MA, Jannink JL.. Selection for seed size has uneven effects on specialized metabolite abundance in oat (Avena sativa L.). G3 (Bethesda). 2022. b;12(3):jkab419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CH, Gouker FE, Crowell CR, Evans L, DiFazio SP, Smart CD, Smart LB.. Joint linkage and association mapping of complex traits in shrub willow (Salix purpurea L.). Ann Bot. 2019;124(4):701–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CH, Stack GM, Jiang Y, Taşkıran B, Cala AR, Toth JA, Philippe G, Rose JKC, Smart CD, Smart LB.. Morphometric relationships and their contribution to biomass and cannabinoid yield in hybrids of hemp (Cannabis sativa). J Exp Bot. 2021;72(22):7694–7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MO, Montilla-Bascon G, Hoekenga OA, Tinker NA, Poland J, Baseggio M, Sorrells ME, Jannink JL, Gore MA, Yeats TH.. Multivariate genome-wide association analyses reveal the genetic basis of seed fatty acid composition in oat (Avena sativa L.). G3 (Bethesda). 2019;9(9):2963–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin AS, Huang Y‐F, Smith S, Bekele WA, Babiker E, Gnanesh BN, Foresman BJ, Blanchard SG, Jay JJ, Reid RW, et al. A consensus map in cultivated hexaploid oat reveals conserved grass synteny with substantial subgenome rearrangement. Plant Genome. 2016;9(2):plantgenome2015.10.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell S, Falcão AX, Shah A, Wilson Z, Greenberg AJ, McCouch SR.. High-resolution inflorescence phenotyping using a novel image-analysis pipeline, PANorama. Plant Physiol. 2014;165(2):479–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell S, Korniliev P, Falcao A, Ismail A, Gregorio G, Mezey J, McCouch S.. Genome-wide association and high-resolution phenotyping link Oryza sativa panicle traits to numerous trait-specific qtl clusters. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10527–10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csardi G, Nepusz T.. The igraph software package for complex network research. Int J Complex Syst. 2006;1695:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, Handsaker RE, Lunter G, Marth GT, Sherry ST, et al. ; 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group . The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(15):2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10(2): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt N, Guedira M, Murphy JP, Marshall D, Mergoum M, Maltecca C, Brown-Guedira G.. A network modeling approach provides insights into the environment-specific yield architecture of wheat. Genetics. iyac076. 2022;221(3): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichsen A. Assessments of genetic diversity within a world collection of cultivated hexaploid oat (Avena sativa l.) based on qualitative morphological characters. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2008;55(3):419–440. [Google Scholar]

- Doehlert D, McMullen M, Jannink J, Panigrahi S, Gu H, Riveland N.. A bimodal model for oat kernel size distributions. Can J Plant Sci. 2005;85(2):317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Doehlert DC, Jannink J, McMullen MS.. Kernel size variation in naked oat. Crop Sci. 2006;46(3):1117–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Doehlert DC, McMullen MS, Baumann RR.. Factors affecting groat percentage in oat. Crop Sci. 1999;39(6):1858–1865. [Google Scholar]

- Doehlert DC, McMullen MS, Jannink J, Panigrahi S, Gu H, Riveland NR.. Evaluation of oat kernel size uniformity. Crop Sci. 2004a;44(4):1178–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Doehlert DC, McMullen MS, Jannink JL, Panigrahi S, Gu H, Riveland N.. Influence of oat kernel size and size distributions on test weight. Cereal Res Commun. 2004b;32(1):135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Tarkowska D, Sedaghatmehr M, Welsch M, Gupta S, Mueller-Roeber B, Balazadeh S.. The HB40-JUB1 transcriptional regulatory network controls gibberellin homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2022;15(2):322–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshire RJ, Glaubitz JC, Sun Q, Poland JA, Kawamoto K, Buckler ES, Mitchell SE.. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endelman JB. Ridge regression and other kernels for genomic selection with R package rrBLUP. Plant Genome. 2011;4(3):250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Esvelt Klos K, Huang YF, Bekele WA, Obert DE, Babiker E, Beattie AD, Bjørnstad s, Bonman JM, Carson ML, Chao S, et al. Population genomics related to adaptation in elite oat germplasm. Plant Genome. 2016;9(2). doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2015.10.0103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esvelt Klos K, Yimer BA, Babiker EM, Beattie AD, Bonman JM, Carson ML, Chong J, Harrison SA, Ibrahim AM, Kolb FL, et al. Genome-wide association mapping of crown rust resistance in oat elite germplasm. Plant Genome. 2017;10(2):10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esvelt Klos K, Yimer BA, Howarth CJ, McMullen MS, Sorrells ME, Tinker NA, Yan W, Beattie AD.. The genetic architecture of milling quality in spring oat lines of the Collaborative Oat Research Enterprise. Foods. 2021;10(10):2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugster M, Leisch F.. From spider-man to hero-archetypal analysis in R. J Stat Soft. 2009;30(8):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Foresman BJ, Oliver RE, Jackson EW, Chao S, Arruda MP, Kolb FL.. Genome-wide association mapping of barley yellow dwarf virus tolerance in spring oat (Avena sativa L.). PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux L, Ilan N, Sanderson RD, Vlodavsky I.. Heparanase: busy at the cell surface. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(10):511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson AA, Kaufman YJ, Stark R, Rundquist D.. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens Environ. 2002;80(1):76–87. [Google Scholar]

- González-Grandío E, Pajoro A, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Tarancón C, Immink RG, Cubas P.. Abscisic acid signaling is controlled by a BRANCHED1/HD-ZIP I cascade in Arabidopsis axillary buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(2):E245–E254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner EL, Sorrells ME, Jannink JL.. Genomic selection for crop improvement. Crop Sci. 2009;49(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Holland JB, Moser HS, O'Donoughue LS, Lee M.. QTLs and epistasis associated with vernalization responses in oat. Crop Sci. 1997;37(4):1306–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Holland J, Portyanko V, Hoffman D, Lee M.. Genomic regions controlling vernalization and photoperiod responses in oat. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;105(1):113–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Gutierrez-Gonzalez JJ, Liu X, Yeats TH, Garvin DF, Hoekenga OA, Sorrells ME, Gore MA, Jannink JL.. Heritable temporal gene expression patterns correlate with metabolomic seed content in developing hexaploid oat seed. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(5):1211–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]