Abstract

Following the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, finding efficient forms of treatment is seen as a priority for both adults and children. On April 25, 2022, remdesivir has become the first United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved COVID-19 treatment for young children, specifically ≥28-days-old children, weighing ≥3 kilograms, who are either hospitalized or non-hospitalized, showing a high risk for progression to severe COVID-19 (prone to hospitalization or death). This new approval, which expands its already FDA-approved use in adults to young children, is supported by the CARAVAN study (a phase 2/3 single-arm, open-label study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of remdesivir (GS-5734™) in participants, from birth to < 18 years of age, with COVID-19). This study is in progress, with an estimated primary completion in February 2023. While positive effects of remdesivir have been ascertained through various studies, controversy has surrounded remdesivir since its initial FDA approval in 2020 due to the contradictory results obtained by various studies. However, many case reports state its positive effects on the outcome of the patients, encouraging an optimistic vision for the future.

Keywords: COVID-19, young children, pediatric, remdesivir, benefits and limitations.

SUMMARY

1. Introduction

2. COVID-19 pathogenesis

3. SARS-CoV-2 infection and clinical manifestations in the pediatric population

4. Management of COVID-19 in pediatric patients

5. Remdesivir: a treatment option for children with COVID-19

6. Remdesivir: adverse reactions described in pediatric patients

6.1 Renal adverse reactions

6.2 Hepatic adverse reactions

6.3 Cardiovascular adverse reactions

6.4 Other adverse events

7. Benefits and limitations

8. Conclusion

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)1, has affected more than 505 million people worldwide. Data from April 2022 show at least 6 million deaths caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection2, with an increased number of cases in the pediatric population consecutive to the Omicron variant3. Even though the incidence of respiratory viral infections in children is generally high, SARS-CoV-2 has rather been associated with increased frequency and severity in adults, probably due to differences between the immune response4. However, children are prone to a particular form of disease known as Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C)5, which usually requires intensive care for those affected4. Many therapies have been tested for COVID-19, and some of them have shown a favorable response in patients – one of the drugs supported by evidence as treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infection is remdesivir (Veklury)5, proving itself beneficial in both adults and children. Remdesivir has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on April 25, 2022 as the first COVID-19 treatment for young children, specifically ≥28-days-old children, weighing ≥3 kilograms, who are either hospitalized or non-hospitalized, showing a high risk for progression to severe COVID-19 (prone to hospitalization or death)6. This came as an update on its FDA approval received on October 22, 2020, which included adults and ≥ 12-year-old children weighing ≥ 40 kilograms, all requiring hospitalization7.

2. COVID-19 pathogenesis

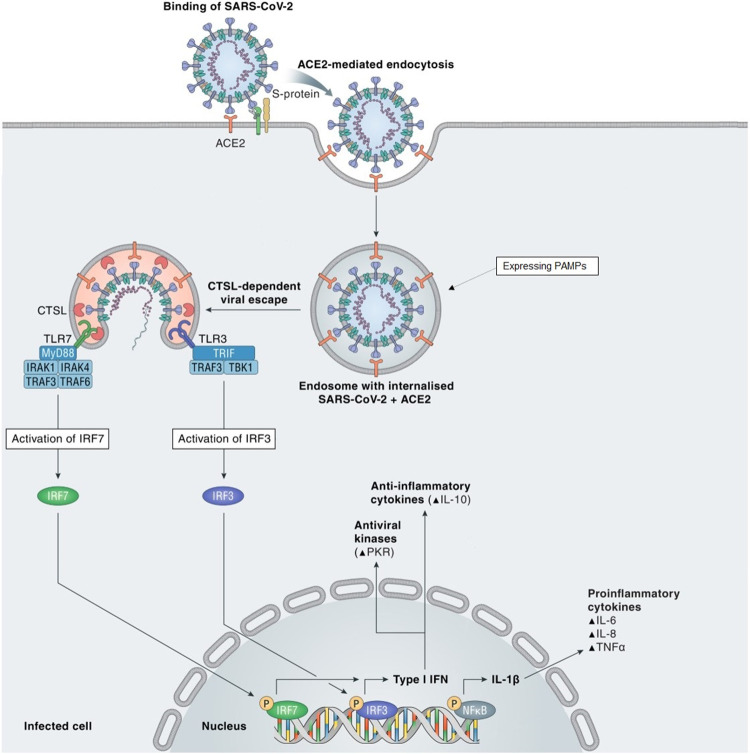

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the beta genus of the Coronaviridae family, order Nidovirales. Coronaviruses have a particular structure which includes 4 types of proteins: spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. The most important for COVID-19 pathogenesis is the S protein, as it targets the highly expressed angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in lungs, gastrointestinal tract, heart, blood vessels, kidneys8. When the S protein binds to ACE2, the virus expressing viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) enters the cytoplasm via endocytosis, where Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are able to recognize the PAMPs. Following this process, intracellular signaling cascades are initiated, leading to type I interferons (IFNs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines production (see Figure 1)9.

Figure 1. SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis.

S protein binds to ACE2 and they enter the cell through endocytosis, followed by a process of cathepsin L (CTSL)-dependent viral escape from the endosome. PAMPs are intercepted by TLR3 and TLR7, which trigger intracellular signaling cascades by activating IRF3 and IRF7. This results in nuclear synthesis of cytokines such as type I IFN or IL-1β.Partially reproduced and adapted from reference9 (this is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited9).

Two steps have been described in COVID-19 pathogenesis: firstly, the virus triggers the initial respiratory symptoms and it is either eliminated at the end of this step, or it aggravates the lung affliction. Secondly, in some patients a so-called ‘cytokine storm’ may occur, leading to hyperinflammation. This causes acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with respiratory failure in adults and MIS-C with reduced lung affliction in children4. Several physiopathological mechanisms responsible for COVID-19 progression are: virus-induced cytopathic effects, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system imbalance due to ACE2 downregulation, the ‘cytokine storm’ caused by an abnormal immune response, coagulopathy, thrombotic microangiopathy and autoimmunity9.

3. SARS-CoV-2 infection and clinical manifestations in the pediatric population

18.9% of all cases of COVID-19 are found in pediatric patients: 12,042,870 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children were described on February 3, 2022 in the United States of America (USA)3. In the pediatric population, SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted through droplets or aerosols, usually from positive adults, and it is characterized by a variable viral incubation period of 2-10 days. Other transmission routes mentioned in literature are the fecal-oral route8, vertical transmission (due to the high expression of ACE2 in the placenta), as well as transmission through human milk, which has not been thoroughly confirmed yet10. There are many risk factors involved in disease progression, such as race (higher risk in African-American and Hispanic children), gender (males are more inclined to suffer from severe forms of COVID-19)11 and comorbidities, which can be stratified by age group in two categories: < 2-year-olds, usually prematurely born with chronic lung disease, airway malformations, neurologic and cardiovascular disease, and 2 to 17-year-old individuals with obesity, diabetes mellitus and feeding tube dependency3. Regarding respiratory disease, asthma and cystic fibrosis are associated with mild forms of COVID-19, while bronchodysplasia aggravates the prognosis4. Other comorbidities associated with increased demand of pediatric intensive care unit admission are genetic anomalies, malignancy, immune suppression, chronic kidney and liver disease, malnutrition, as well as sickle cell anemia8. The aforementioned comorbidities designate the so-called “children with medical complexity”, which bear the risk of increased severity of COVID-19 through decompensation of the chronic disease12. There is contradictory evidence regarding age as a risk factor for increased severity of the disease: some data indicate that infants younger than 6 months have a higher risk of severe disease than older children12, while other studies pin the increased illness severity on older children. Fortunately, the mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infected children admitted into the intensive care unit is significantly lower than mortality found in adults13. This might be due to the fact that ACE2 receptor in alveolar type 2 cells is different in children, or because of the immune system particularities found in the pediatric population. Also, the lower rate of some comorbidities (arterial hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes) in children should not be overlooked. COVID-19 has five different clinical presentations in pediatric cases – asymptomatic, mild, moderate (developing mild respiratory distress), with severe respiratory symptoms and requiring intensive care unit admission (respiratory failure or MIS-C)4. Alongside the respiratory symptoms, digestive symptoms may occur rather frequently (diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting), and less often dermatologic lesions (urticarial or vesicular eruptions, livedo reticularis, pernio-like acral lesions) might be present8. The severity of COVID-19 in children has not been internationally classified. The guideline regarding the administration of remdesivir defines a severe case by its supplemental oxygen requirement and need for medical ventilation14. MIS-C itself is described as a post-infectious inflammatory phenomenon, even though it can also appear while the viral infection is active12.The immune response responsible for MIS-C is similar to the one found in Kawasaki disease. Its symptoms include: fever, systemic inflammatory syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction15.

4. Management of COVID-19 in pediatric patients

Since randomized control trials usually include adults, the clinical practice guidelines regarding COVID-19 management in children are mostly based on extrapolations of the results attained for the adult population2. COVID-19 cases in the pediatric population are usually less severe than those found in adults, therefore supportive care is often satisfactory for both neonates16 and older children. However, antiviral therapy with remdesivir is a viable option for patients with severe forms of the disease13. The first step in case management consists of testing the patients with increased suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 infection, using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as method of diagnosis. In neonates, testing is recommended 12-24 hours after birth, with a second test performed 24 hours after the first one. There are three scenarios found in neonates: congenital infection in live born neonates (SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed in mother and child using RT-PCR for viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) detection in umbilical cord blood, neonatal blood collected within the first 12 hours after birth, or amniotic fluid), neonatal infection acquired intrapartum (SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed in mother and child using RT-PCR for viral RNA detection in nasopharyngeal swab within the first 24-48 hours after birth) and neonatal infection acquired postpartum (SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed in the ≥ 2 days-old child, with/without infection present in parent)10. Supportive care for COVID-19 pediatric patients includes respiratory support, maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, suitable nutrition, second infection prophylaxis and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Symptomatic treatment is also provided8. Regarding antiviral treatment, remdesivir is the only FDA approved drug for young children (since April 25, 2022), in both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients who are considered to be at high risk for complications – this category of children might include those suffering from diabetes mellitus, especially in association with obesity12 (which, itself, might increase the probability of hospitalization)14, and also patients diagnosed with chronic pulmonary disease17. High intensity therapies should be avoided when treating oncologic pediatric patients18. Other drugs that could be used for treating SARS-CoV-2 patients and/or its induced symptoms in patients are dexamethasone (for patients with respiratory distress requiring oxygen or ventilatory support), bamlanivimab, casirivimab or imdevimab (monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 S protein antibodies used within complicated cases of COVID-19), tocilizumab and anakinra (when the patient has contraindications for administering remdesivir)19.

5. Remdesivir: a COVID-19 treatment option for children

Remdesivir (Veklury) is a prodrug that belongs to the class of phosphoramidate compounds. Its antiviral activity is accomplished by conversion to the active metabolite GS-443902 triphosphate (also known as GS-441524)20, which is able to incorporate itself into viral RNA, leading to premature termination21. It is an adenine nucleotide analogue20 developed in 2017 for treating Ebola virus infection5, but not being able to treat this disease successfully. However, its safety has made it a candidate for drug repurposing research22. It has broad-spectrum antiviral activity against Filoviruses (e.g., Ebola virus), Paramyxoviruses (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus) and Coronaviruses (including SARS-CoV-2)23. Remdesivir inhibits an enzyme called RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which is required for SARS-CoV-2 replication inside the host cells. Therefore, the viral RNA replication is interrupted after remdesivir administration. There is also another antiviral mechanism mentioned, which involves another enzyme - main protease (Mpro), responsible for cleaving polyproteins and coordinating SARS-CoV-2 replication. Remdesivir and its active metabolite bind to Mpro, exerting an additional inhibition of viral replication24. After successful administration of remdesivir to the first COVID-19 patient (confirmed on January 20, 2020), the symptom resolution and the favorable outcome of the patient have served as proof of its beneficial effects on treating SARS-CoV-2 infection25. Subsequently, FDA has launched a Coronavirus Treatment Acceleration Program in order to develop eligible therapeutic options for treating SARS-CoV-2 infection26. On May 1, 2020, FDA granted an emergency use authorization for remdesivir administration in severe cases of COVID-19, for both adults and children5. Shortly after, the evidence regarding the beneficial effects of remdesivir have been strengthened by new studies12, leading to expanding the approval for administration to non-severe cases of COVID-19 as well, on August 28, 202024. On October 22, 2020, remdesivir became the first FDA approved drug for treating COVID-19 in ≥ 12 years-old children and adolescents, weighing at least 40 kg and in need of hospitalization, with an additional approval for emergency use in hospitalized pediatric patients weighing ≥ 3.5 kg, that were either < 12 years-old or weighted <40 kg15. Remdesivir use in hospitalized children has increased significantly after October 2020, as it has been administered to almost 60% of hospitalized children during November and December27. Remdesivir has become the first FDA approved COVID-19 treatment for children younger than 12 years-old on April 25, 2022. The specific guidelines include using injectable remdesivir for ≥ 28 days-old children, weighing ≥ 3 kilograms, who are either hospitalized or non-hospitalized but showing a high risk for progression to severe COVID-19 (prone to hospitalization or death)6. The new FDA approval is supported by the CARAVAN Study (a phase 2/3 single-arm, open-label study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of remdesivir (GS-5734™) in participants from birth to < 18 years of age with COVID-19), with an estimated primary completion in February 2023, which includes 8 cohorts of pediatric participants (62 enrolled – May 13, 2022). 5 of them include children ≥ 28 days to < 18 years-old, 2 cohorts include 0-28 days-old term neonatal participants, and there is also a cohort of preterm neonates and 0-56 days-old infants. All of them receive age-appropriate doses of remdesivir for up to 10 days28 (see Table 1).

Table 1. CARAVAN study cohorts and remdesivir treatment administered to each cohort according to age and weight28.

| Cohort | Age and weight | Remdesivir dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 | 12-18 years-old weighing ≥ 40 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 200mg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 100 mg/day |

| Cohort 2 | ≥ 28 days-old to < 18 years-old weighing 20-40 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 2.5 mg/kg/day |

| Cohort 3 | ≥ 28 days-old to < 18 years-old weighing 12-20 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 2.5 mg/kg/day |

| Cohort 4 | ≥ 28 days-old to < 18 years-old weighing 3-12 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 2.5 mg/kg/day |

| Cohort 5 | 14-28 days-old, gestational age > 37 weeks and weight at screening ≥ 2.5 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 2.5 mg/kg/day |

| Cohort 6 | 0-14 days-old, gestational age > 37 weeks and birth weight ≥ 2.5 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 2.5mg/kg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 1.25 mg/kg/day |

| Cohort 7 | 0-56 days-old, gestational age ≤ 37 weeks and birth weight ≥ 1.5 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 2.5mg/kg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 1.25 mg/kg/day |

| Cohort 8 | < 12 years-old weighing ≥ 40 kg | Intravenous remdesivir 200mg (loading dose, on day 1) followed by 100 mg/day |

In addition, many case reports revealing remdesivir usage with a favorable outcome in the pediatric population have been cited in the literature (see Table 2).

Table 2. A series of cases cited from literature showing different approaches and outcomes of remdesivir treatment in the pediatric population.

Abbreviations: weeks of gestation (WoG); day of hospitalization (DoH); Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP); Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP); postinfectious bronchiolitis obliterans (PIBO); respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); body mass index (BMI); alanine aminotransferase (ALT); acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); atrioventricular valve regurgitation (AVVR); pro–brain natriuretic peptide (BNP); aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

| Citation | Patients treated with remdesivir | Comorbidities/Patient particularities | Treatment | Remdesivir Treatment Duration | Outcomes | Adverse drug reactions (ADR) to remdesivir |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hopwood AJ et al., 202029 | 1, neonate [birth - 40 weeks of gestation (WoG)] | -mother: 15-year-old, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at birth -patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 24 hours after birth (presumed vertical transmission) | -supplemental oxygen; continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) [started on the 4th day of hospitalization (DoH)] -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5 mg/kg/day (DoH 4-13) -dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg/day (DoH 5-8) -positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP); convalescent COVID-19 plasma: first dose of 10mL/kg, then 15mL/kg 24 hours later (DoH 8) -vancomycin (DoH 19-28) | 10 days | -favorable outcome, after 13 days of intubation and ventilation, and a total of 30 days of CPAP use. | Bradycardia (on DoH 6) |

| Sarhan MA et al., 202216 | 1, neonate (birth – 34 WoG) | -mother: 34-year-old, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 4 hours before birth -patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 24 hours after birth (presumed vertical transmission) | -intubation; ventilatory support; dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg/day (DoH 6) -midazolam, morphine, rocuronium (DoH 8) -high dose of dexamethasone (0.5mg/kg/day) (DoH 8) -remdesivir 2.5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 1.25 mg/kg/day (DoH 8-13) | 6 days | -favorable outcome, the respiratory status improved within 2 days of remdesivir; the patient was off all respiratory support on DoH 25, and was discharged home on DoH 31. | None |

| Frauenfelder C et al., 202030 | 1, 5 weeks after birth (birth - 32+6 corrected WoG) | -ex-premature twin -maternal preeclampsia -small atrial septal defect (<4mm), cleft palate | -ventilatory support -remdesivir 5 mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 1.25 mg/kg/day | 10 days | -favorable outcome, the patient tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 after 5 days of remdesivir, was extubated on DoH 18, and was discharged home. | None |

| Saikia B et al., 202131 | 2: 1st: 1 week after birth (birth – 31 WoG) 2nd: 35+2 corrected weeks (birth – 33 WoG) | -ex-premature patients | 1st: -cefotaxime, amoxicillin, gentamicin, acyclovir (empirically) -respiratory support (DoH 6) -hydrocortisone 0.5mg/kg/day (DoH 7-16) -remdesivir 2.5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 1.25mg/kg/day (DoH 11-15) 2nd: -cefotaxime, amoxicillin, gentamicin, acyclovir (empirically) -intubation shortly after admission -remdesivir 2.5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 1.25mg/kg/day (DoH 4-7) -dexamethasone 150µg/kg/day (DoH 4-10) | 1st: 5 days 2nd: 4 days | 1st: -favorable outcome, patient was extubated after 2 days of remdesivir and had a negative result for SARS-CoV-2 infection after completing the treatment with remdesivir. 2nd: -favorable outcome, the patient and came off oxygen on DoH 5, had a negative result for SARS-CoV-2 infection after 2 days of remdesivir, and was discharged home on DoH 9. | None |

| Cursi L et al., 202132 | 1, 9-day-old (birth – 36 WoG) | -ex-premature -cerebral venous thrombosis (as a complication of COVID-19) | -anti SARS-CoV-2 hyperimmune plasma -dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg/day -remdesivir 2.5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 1.25mg/kg/day (started on day 5) -enoxaparin 100 UI/kg | 10 days | -favorable outcome, the patient was extubated after 13 days and became oxygen independent after 4 more days. | None |

| Koletsi P et al., 202117 | 1, 3-year-old | -severe postinfectious bronchiolitis obliterans (PIBO), diagnosed at 13-months-old after an episode of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and adenovirus coinfection -mixed hypercapnic and hypoxemic respiratory failure | -broad spectrum antibiotics -dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg/day (DoH 1-5) -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5mg/kg/day (DoH 4-8) | 5 days | -favorable outcome, with symptom regression 24 hours after the first dose of remdesivir; the patient was discharged home on DoH 11. | None |

| Jo Y et al., 202114 | 1, 9-year-old | -obesity [body mass index (BMI) of 27.6kg/m²] | -oxygen therapy (since DoH 1) -dexamethasone 6mg (0.15mg/kg, with a maximum dose of 6mg) (DoH 2-11) -remdesivir 200mg (loading dose for body weights ≥ 40 kg), followed by 100mg/day (DoH 2-6) | 5 days | -favorable outcome, with symptom regression on DoH 4; the patient came off oxygen on DoH 9 and was discharged home on DoH 21. | None |

| Chow EJ et al., 202133 | 1, 16-year-old | -obesity (BMI of 43.9kg/m²) | -oxygen therapy (since DoH 1) -remdesivir 200mg (loading dose) | 1 day (treatment stopped after the loading dose due to ADR) | -the patient had a favorable outcome despite stopping the remdesivir treatment after only one dose (due to the presence of bradycardia). The heart rates increased and the patient returned to the usual state of health in the week after hospital discharge. | Reversible sinus bradycardia: within 6 hours after remdesivir administration, the lowest heart rate was 46 bpm. |

| Eleftheriou I et al., 202134 | 3: 1st: 13.5-year-old 2nd: 10-year-old 3rd: 3-month-old | None | -ampicillin -remdesivir -dexamethasone | -1st: 5 days -2nd: 5 days -3rd: 3 days (treatment stopped after the occurrence of ADR) | -heart rates returned to normal after completing the treatment for the 1st and 2nd patient, and 24 hours after discontinuation of remdesivir in the 3rd. | Asymptomatic sinus bradycardia: after administering the third (2nd and 3rd patient) or fourth dose (1st patient) of remdesivir. |

| Sanchez-Codez MI et al., 202135 | 1, 13-year-old | -asthma | -oxygen therapy -dexamethasone -ceftriaxone -remdesivir 200mg (loading dose), followed by 100mg/day | 3 days (treatment stopped after the occurrence of ADR) | -heart rate returned to normal 24 hours after discontinuation of remdesivir treatment | Asymptomatic sinus bradycardia: after the third dose of remdesivir (heart rate of 40 bpm) |

| Wardell H et al., 202036 | 1, 19-day-old | -suspicion of evolving myocardial injury [elevated high sensitivity troponin T and N-terminal portion of pro–brain natriuretic peptide (BNP); mildly depressed left ventricular function] | -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5mg/kg/day (started on DoH 4) -enoxaparin 0.8mg/kg/day (on DoH 5) -aspirin 20.25mg/day (on DoH 6) | 7 days | -favorable outcome, patient was discharged on DoH 9; the systolic function and ejection fraction were normal 3 weeks after discharge. | None |

| Faltin K et al., 202237 | 1, 17-year-old | -Friedrich’s ataxia-induced hypertrophic cardiomyopathy -atrial fibrillation, heart failure | -remdesivir 200mg (loading dose), followed by 100mg/day -convalescent plasma (anti-SARS-CoV-2 titer 1:600; 1 unit of 200mL) | 5 days | -favorable outcome, with normalization of myocardial injury markers subsequent to remdesivir administration; the patient was discharged on DoH 17. | None |

| Orf K et al., 202038 | 1, 5-year-old | -precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | -nebulized adrenalin -a single dose of oral dexamethasone -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5mg/kg/day (started on DoH 2) -ALL induction chemotherapy (dexamethasone, vincristine, pegylated asparaginase) (started on DoH 2) | 5 days (treatment stopped after the occurrence of ADR) | -favorable outcome (regarding COVID-19), the patient was discharged on day 8 of chemotherapy induction | -increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (maximum value: 408 U/L) on DoH 5, which returned to normal after interrupting remdesivir administration (within 10 days) |

| Dell’Isola GB et al., 202118 | 1, 6-year-old | -acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5mg/kg/day -convalescent plasma -antileukemic treatment | 5 days | -favorable outcome (regarding COVID-19), a rapid resolution of the infection was obtained. | None |

| Gadzińska J et al., 202239 | 1, (nearly) 10-year-old | -ALL | -antileukemic treatment -oxygen therapy (DoH 23) -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5mg/kg/day (DoH 26-30) | 5 days | -favorable outcome (regarding COVID-19), the patient was discharged home on DoH 38. | None |

| Rodriguez Z et al., 202040 | 1, 9-week-old | -trisomy 21 -unrepaired balanced complete atrioventricular canal defect -mild to moderate atrioventricular valve regurgitation (AVVR) | -bilevel noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (DoH 12) -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose), followed by 2.5mg/kg/day (DoH 15-25) -convalescent plasma | 11 days | -there was a lack of response to remdesivir, followed by deterioration of the patient’s clinical status despite 11 days of treatment. | None |

| Patel PA et al., 202041 | 1, 12-year-old | -severe thrombocytopenia (presumably associated with the severe form of COVID-19) | -immunoglobulin -steroids -mechanical ventilation, inhaled nitric oxide, airway pressure release ventilation -azithromycin -hydroxychloroquine 400mg twice daily on DoH 4 followed by 200mg twice daily until DoH 7 -tocilizumab 8mg/kg, 2 doses, 12 hours apart) -remdesivir 200mg (loading dose) followed by 100mg/day (started on DoH 7) | 6 days (treatment stopped after the occurrence of ADR) | -favorable outcome, even though remdesivir was discontinued, the patient was extubated on DoH 14 and discharged on DoH 24 | -mildly elevated transaminases, which led to interrupting remdesivir treatment on DoH 12. |

| Kaur M et al., 202242 | 1, 14-day-old | None | -CPAP -intubation (DoH 5) -remdesivir 5mg/kg (loading dose) (DoH 5) | 1 day (treatment stopped after the loading dose due to ADR) | - after interrupting the remdesivir treatment, the liver enzymes decreased to normal ranges until DoH 15. | -significant transaminase elevation [maximum value for aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 1121 U/L and maximum value for ALT: 832 U/L) |

Since the bioavailability by oral administration is not adequate, remdesivir can only be administered intravenously and it has a half-time of 1 hour, while its active metabolite has a longer half-time of 40 hours. The drug is metabolized within plasma and liver; thus, it is contraindicated in patients with liver disease, and while its renal excretion is low, there is one metabolite (GS-441524) that is excreted renally in a higher quantity, making remdesivir contraindicated in patients with impaired renal function. However, these data are obtained through adult studies and extrapolated into the pediatric population19. Testing the liver and kidney functions prior to remdesivir administration is mandatory4.

Drug interactions need to be analyzed, as they have multiple implications in the patient management. Remdesivir is a weak inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), organic anion transporter protein 1B1 (OATP1B1), organic anion transporter protein 1B3 OATP1B3, and Multidrug and Toxin Extrusion Protein 1 (MATE1) in vitro, but studies have shown that its inhibitory actions on drug-metabolizing enzymes or transporters are not clinically significant in COVID-19 patients treated with therapeutic doses of remdesivir23. Observational studies on adult populations revealed that clinical benefits could be obtained while using dexamethasone in addition to remdesivir treatment3. Associations with azithromycin and antiepileptic drugs should be avoided because of the risk of hepatotoxicity4, and also the latter can be responsible for reducing remdesivir serum concentration by activating CYP3A4 and cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9 (CYP2C9). It has been proved that Hydroxychloroquine has an antagonistic effect on the antiviral effect linked to remdesivir.

Therefore, the two should not be used together for treating COVID-1943.

6. Remdesivir: Adverse Drug Effects described in pediatric patients

Similar to every other medicine, adverse drug effects of remdesivir should be noted and taken into consideration when selecting it as treatment for a patient. It is known that its active metabolite accumulates in kidneys, liver and digestive tract24; thus, its most frequent adverse drug effects are kidney injury and hepatic enzymes elevation44, which can ultimately increase COVID-19 severity in patients with pre-existing complications45 Remdesivir use could be hazardous for patients with ALT or AST levels that are 5 times higher than the upper limit of normal, patients with the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min, as well as pregnant or lactating women24.

6.1 Renal adverse drug reactions

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is quite common in COVID-19 patients and it involves glomerular, tubular and vascular affliction in the kidneys9. Unfortunately, remdesivir itself can further worsen the kidney injury as its metabolite (GS-441,524) can be found in urine after drug intake44, but also through kidney accumulation of an excipient (sulfobutylated beta-cyclodextrin sodium salt), especially in pediatric patients with previous renal impairment which receive renal replacement therapies.

Therefore, remdesivir is not recommended in children of ≥28-days-old with an eGFR <30mL/min and full-term neonates (<28-days-old) with a serum creatinine of ≥ 1mg/dL43.

6.2 Hepatic adverse drug reactions

Elevation of liver transaminases and hyperbilirubinemia can be found in COVID-19 patients9. In 2021, the incidence of liver injury associated with remdesivir use was 15.2%46. Remdesivir adds an additional risk of liver impairment for the patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, as its hepatotoxicity has been proven - it reversibly increases liver enzymes44. Therefore, it is not recommended in pediatric patients with baseline ALT 5 times higher than the upper limit of normal. Liver function tests should be performed before starting remdesivir43, as well as every day during treatment4.

Drug interactions should be taken into consideration due to the risk of increased hepatotoxicity imposed by associating remdesivir intake with P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, cyclosporine or tacrolimus43.

6.3 Cardiovascular adverse drug reactions

Acute coronary syndrome, acute heart failure, arrhythmias and myocarditis are some of the cardiovascular afflictions caused by COVID-199. However, remdesivir could also be responsible for some cardiac adverse drug effects: the most talked about in literature is reversible sinus bradycardia, found in both adult and pediatric patients33, but there is also proof that it could account for cardiac arrest, shock, hypotension, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, probably through decreasing the cell viability of human pluripotent stem cell cardiomyocytes47. Some speculations have been made regarding the mechanisms that are involved in producing bradycardia: because remdesivir is an adenosine analog, it could block the atrioventricular node, or it could bind to human mitochondrial RNA polymerase, producing cardiotoxicity35.

All COVID-19 pediatric patients receiving remdesivir should be monitored through electrocardiography4.

6.4 Other adverse drug events

Other adverse drug effects cited by studies are hypersensitivity reactions (including variations in blood pressure and heart rate), labial and periocular edema, rash, nausea, hypoxemia, wheezing, shortness of breath, fever, sweating or shivering6.

7. Benefits and Limitations

While positive effects of remdesivir have been ascertained through various studies, controversy has surrounded remdesivir since its initial FDA approval in 2020.

Remdesivir has proven itself beneficial in outpatient care, reducing hospitalization and mortality by 87% (if administered early after COVID-19 diagnosis)48. Another study in favor of remdesivir administration is the double-blind, randomized Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT-1), which has also shown reduced hospitalization (10 days, compared to 15 days in patients who received placebo)49. It is also thought to be responsible for reducing the time of mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe COVID-19 cases1.

However, several studies have shown contradictory results, some of them stating that remdesivir has no impact whatsoever on treating SARS-CoV2-infection. The most important is the Solidarity trial conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2020. It involves 405 hospitals from 30 countries, and it has concluded that remdesivir does not reduce COVID-19 mortality and length of hospital stay. The timing of the FDA approval was debated as there had also been a smaller study previously published in April 2020 stating the absence of benefits in remdesivir treatment, with no impact on SARS-CoV-2 viral load, that had not been taken into consideration by FDA within remdesivir approval50. Another study made on a large group of hospitalized COVID-19 veterans treated with remdesivir has actually found an increased length of hospital, without significantly improving survival49.

Remdesivir is actually contraindicated in patients with multiorgan dysfunction, vasopressor support, co-administration of other antivirals, elevated ALT or severe renal impairment19, as liver and kidney adverse drug effects have been stated in remdesivir-treated COVID-19 patients50. It is also not recommended for patients suffering from MIS-C12.

Studies have shown that remdesivir penetration into lung tissue might not reach optimal tissue levels in all patients leading to variable therapeutic response51, which might also be caused by different timing of administration. Its best effects were obtained during high viral load (first 5 days of symptoms), while administration in advanced stages has shown poor efficiency52.

A disadvantage of remdesivir therapy is that currently it can only be administered intravenously. However, developing an orally bioavailable variant is certainly a plausible scenario for the future48.

There are also limitations involving drug interactions, as remdesivir is both a substrate for some cytochromes (CYP2C8, CYP2D6, CYP3A4) in vitro, and hydrolase, which is responsible for its metabolism12. Hydroxychloroquine and remdesivir should not be administered simultaneously because of the antagonistic effects that the former exerts on the latter24.

8. Conclusion

Since SARS-CoV-2 can affect the entire pediatric population, with different degrees of severity that range from asymptomatic to lethal, finding efficient forms of treatment is seen as a priority. While most of the studies regarding COVID-19 therapeutic measures are conducted in the adult population, many studies and case reports showing good results of remdesivir use in children have emerged. The most influential nowadays is the CARAVAN cohort study, which is currently in progression (with an estimated primary completion date in February 2023).

However, while the future appears to be brighter for young children infected with SARS-CoV-2 due to the new FDA approval of remdesivir for treating COVID-19, the long-term and short-term effects of this drug should continuously be tracked and investigated, since not all the studies have suggested a positive outcome regarding its efficiency. Thus, its administration still remains controversial and it is undoubtedly not a replacement for the prophylactic measures, such as vaccination.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Victor Babes National Institute of Pathology and Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy for their support. AT is supported by a PCE 153/2021 (PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2020-2027) grant from the Romanian Government (UEFISCDI). Authors would like to acknowledge the funding from Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization in Romania, under Program 1 – The Improvement of the National System of Research and Development, Subprogram 1.2 – Institutional Excellence – Projects of Excellence Funding in RDI, Contract No. 31PFE/30.12.2021.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C); United States food and drug administration (FDA); spike protein (S); membrane protein (M); envelope protein (E); nucleocapsid protein (N); angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2); acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); cathepsin L (CTSL); United States of America (USA); reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); ribonucleic acid (RNA); adverse drug reactions (ADR); weeks of gestation (WoG); day of hospitalization (DoH); Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP); Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP); postinfectious bronchiolitis obliterans (PIBO); respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); body mass index (BMI); alanine aminotransferase (ALT); acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); atrioventricular valve regurgitation (AVVR); pro–brain natriuretic peptide (BNP); aspartate aminotransferase (AST); RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp); main protease (Mpro); Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4); organic anion transporter protein 1B1 (OATP1B1); organic anion transporter protein 1B3 (OATP1B3); Multidrug and Toxin Extrusion Protein 1 (MATE1); Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9 (CYP2C9); estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); acute kidney injury (AKI); World Health Organization (WHO).

DISCOVERIES is a peer-reviewed, open access, online, multidisciplinary and integrative journal, publishing high impact and innovative manuscripts from all areas related to MEDICINE, BIOLOGY and CHEMISTRY

References

- 1.Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. Beigel John H, Tomashek Kay M, Dodd Lori E, Mehta Aneesh K, Zingman Barry S, Kalil Andre C, Hohmann Elizabeth, Chu Helen Y, Luetkemeyer Annie, Kline Susan, Lopez de Castilla Diego, Finberg Robert W, Dierberg Kerry, Tapson Victor, Hsieh Lanny, Patterson Thomas F, Paredes Roger, Sweeney Daniel A, Short William R, Touloumi Giota, Lye David Chien, Ohmagari Norio, Oh Myoung-Don, Ruiz-Palacios Guillermo M, Benfield Thomas, Fätkenheuer Gerd, Kortepeter Mark G, Atmar Robert L, Creech C Buddy, Lundgren Jens, Babiker Abdel G, Pett Sarah, Neaton James D, Burgess Timothy H, Bonnett Tyler, Green Michelle, Makowski Mat, Osinusi Anu, Nayak Seema, Lane H Clifford. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;383(19):1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Characteristics and conflicting recommendations of clinical practice guidelines for COVID-19 management in children: A scoping review. Quincho-Lopez Alvaro, Chávez-Rimache Lesly, Montes-Alvis José, Taype-Rondan Alvaro, Alvarado-Gamarra Giancarlo. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2022;48:102354. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Infection in Children: Diagnosis and Management. Zhu Frank, Ang Jocelyn Y. Current infectious disease reports. 2022;24(4):51–62. doi: 10.1007/s11908-022-00779-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Therapeutic Strategies for COVID-19 Lung Disease in Children. Gatti Elisabetta, Piotto Marta, Lelii Mara, Pensabene Mariacarola, Madini Barbara, Cerrato Lucia, Hassan Vittoria, Aliberti Stefano, Bosis Samantha, Marchisio Paola, Patria Maria Francesca. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2022;10:829521. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.829521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.COVID-19 treatment in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Panda Prateek Kumar, Sharawat Indar Kumar, Natarajan Vivekanand, Bhakat Rahul, Panda Pragnya, Dawman Lesa. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2021;10(9):3292–3302. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2583_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Approves First COVID-19 Treatment for Young Children. U.S. Food and Drugs Administration. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-approves-first-covid-19-treatment-young-children https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-approves-first-covid-19-treatment-young-children

- 7.Fact Sheet for Parents and Caregivers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of VEKLURY® (remdesivir) U.S. Food and Drugs Administration. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/137565/download https://www.fda.gov/media/137565/download

- 8.COVID-19 Pandemic and Children: A Review. Rathore Vinay, Galhotra Abhiruchi, Pal Rahul, Sahu Kamal Kant. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2020;25(7):574-585. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-25.7.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.COVID-19: immunopathology, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment options. van Eijk Larissa E, Binkhorst Mathijs, Bourgonje Arno R, Offringa Annette K, Mulder Douwe J, Bos Eelke M, Kolundzic Nikola, Abdulle Amaal E, van der Voort Peter Hj, Olde Rikkert Marcel Gm, van der Hoeven Johannes G, den Dunnen Wilfred Fa, Hillebrands Jan-Luuk, van Goor Harry. The Journal of pathology. 2021;254(4):307–331. doi: 10.1002/path.5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lessons Learned so Far from the Pandemic: A Review on Pregnants and Neonates with COVID-19. Marim Feride, Karadogan Dilek, Eyuboglu Tugba Sismanlar, Emiralioglu Nagehan, Gurkan Canan Gunduz, Toreyin Zehra Nur, Akyil Fatma Tokgoz, Yuksel Aycan, Arikan Huseyin, Serifoglu Irem, Gursoy Tugba Ramasli, Sandal Abdulsamet, Akgun Metin. The Eurasian journal of medicine. 2020;52(2):202–210. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2020.20118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical Features of Critical Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children. Bhumbra Samina, Malin Stefan, Kirkpatrick Lindsey, Khaitan Alka, John Chandy C, Rowan Courtney M, Enane Leslie A. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2020;21(10):e948–e953. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multicenter Interim Guidance on Use of Antivirals for Children With Coronavirus Disease 2019/Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Chiotos Kathleen, Hayes Molly, Kimberlin David W, Jones Sarah B, James Scott H, Pinninti Swetha G, Yarbrough April, Abzug Mark J, MacBrayne Christine E, Soma Vijaya L, Dulek Daniel E, Vora Surabhi B, Waghmare Alpana, Wolf Joshua, Olivero Rosemary, Grapentine Steven, Wattier Rachel L, Bio Laura, Cross Shane J, Dillman Nicholas O, Downes Kevin J, Oliveira Carlos R, Timberlake Kathryn, Young Jennifer, Orscheln Rachel C, Tamma Pranita D, Schwenk Hayden T, Zachariah Philip, Aldrich Margaret L, Goldman David L, Groves Helen E, Rajapakse Nipunie S, Lamb Gabriella S, Tribble Alison C, Hersh Adam L, Thorell Emily A, Denison Mark R, Ratner Adam J, Newland Jason G, Nakamura Mari M. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2021;10(1):34–48. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Compassionate Use of Remdesivir in Children With Severe COVID-19. Goldman David L, Aldrich Margaret L, Hagmann Stefan H F, Bamford Alasdair, Camacho-Gonzalez Andres, Lapadula Giuseppe, Lee Philip, Bonfanti Paolo, Carter Christoph C, Zhao Yang, Telep Laura, Pikora Cheryl, Naik Sarjita, Marshall Neal, Katsarolis Ioannis, Das Moupali, DeZure Adam, Desai Polly, Cao Huyen, Chokkalingam Anand P, Osinusi Anu, Brainard Diana M, Méndez-Echevarría Ana. Pediatrics. 2021;147(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-047803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A Case Report for Severe COVID-19 in a 9-Year-Old Child Treated with Remdesivir and Dexamethasone. Jo Yoon Hee, Hwang Yosub, Choi Soo Han. Journal of Korean medical science. 2021;36(29):e203. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potentially effective drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 or MIS-C in children: a systematic review. Wang Zijun, Zhao Siya, Tang Yuyi, Wang Zhili, Shi Qianling, Dang Xiangyang, Gan Lidan, Peng Shuai, Li Weiguo, Zhou Qi, Li Qinyuan, Mafiana Joy James, Cortés Rafael González, Luo Zhengxiu, Liu Enmei, Chen Yaolong. European journal of pediatrics. 2022;181(5):2135–2146. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04388-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SARS-CoV-2 Associated Respiratory Failure in a Preterm Infant and the Outcome after Remdesivir Treatment. Sarhan Mohammed A., Casalino Maria, Paopongsawan Pongsatorn, Gryn David, Kulkarni Tapas, Bitnun Ari, Gauda Estelle B. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2022;41(5):e233-e234. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A toddler diagnosed with severe postinfectious bronchiolitis obliterans and COVID‐19 infection. Koletsi Patra, Antoniadi Marita, Mermiri Despina, Koltsida Georgia, Koukou Dimitra, Noni Maria, Spoulou Vasiliki, Michos Athanasios. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ppul.25436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Case Report: Remdesivir and Convalescent Plasma in a Newly Acute B Lymphoblastic Leukemia Diagnosis With Concomitant Sars-CoV-2 Infection. Dell'Isola Giovanni Battista, Felicioni Matteo, Ferraro Luigi, Capolsini Ilaria, Cerri Carla, Gurdo Grazia, Mastrodicasa Elena, Massei Maria Speranza, Perruccio Katia, Brogna Mariangela, Mercuri Alessandra, Pasqua Barbara Luciani, Gorello Paolo, Caniglia Maurizio, Verrotti Alberto, Arcioni Francesco. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.712603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.COVID-19: potential therapeutics for pediatric patients. Younis Nour K., Zareef Rana O., Fakhri Ghina, Bitar Fadi, Eid Ali H., Arabi Mariam. Pharmacological Reports. 2021;73(6):1520-1538. doi: 10.1007/s43440-021-00316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simulated Assessment of Pharmacokinetically Guided Dosing for Investigational Treatments of Pediatric Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Maharaj Anil R., Wu Huali, Hornik Christoph P., Balevic Stephen J., Hornik Chi D., Smith P. Brian, Gonzalez Daniel, Zimmerman Kanecia O., Benjamin Daniel K., Cohen-Wolkowiez Michael. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020;174(10):e202422. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.COVID-19: Review of Epidemiology and Potential Treatments Against 2019 Novel Coronavirus. Jan Hasnain, Faisal Shah, Khan Ayyaz, Khan Shahzar, Usman Hazrat, Liaqat Rabia, Shah Sajjad Ali. Discoveries. 2020:e108. doi: 10.15190/d.2020.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drug Repurposing for Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19: A Clinical Landscape. Hossain Md. Shahadat, Hami Ithmam, Sawrav Md. Sad Salabi, Rabbi Md. Fazley, Saha Otun, Bahadur Newaz Mohammed, Rahaman Md. Mizanur. Discoveries. 2020;8(4):e121. doi: 10.15190/d.2020.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic, and Drug-Interaction Profile of Remdesivir, a SARS-CoV-2 Replication Inhibitor. Humeniuk Rita, Mathias Anita, Kirby Brian J., Lutz Justin D., Cao Huyen, Osinusi Anu, Babusis Darius, Porter Danielle, Wei Xuelian, Ling John, Reddy Y. Sunila, German Polina. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2021;60(5):569-583. doi: 10.1007/s40262-021-00984-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remdesivir for treatment of COVID-19; an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Rezagholizadeh Afra, Khiali Sajad, Sarbakhsh Parvin, Entezari-Maleki Taher. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2021;897:173926. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for COVID-19 Patients. Zhu Shudong, Guo Xialing, Geary Kyla, Zhang Dianzheng. Discoveries. 2020;8(1):e105. doi: 10.15190/d.2020.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: A Threat to Global Health. Saha Otun, Rakhi Nadira Naznin, Sultana Afroza, Rahman Md. Mahbubur, Rahaman Md. Mizanur. Discoveries Reports. 2020;3:e13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.A Description of COVID-19-Directed Therapy in Children Admitted to US Intensive Care Units 2020. Schuster Jennifer E, Halasa Natasha B, Nakamura Mari, Levy Emily R, Fitzgerald Julie C, Young Cameron C, Newhams Margaret M, Bourgeois Florence, Staat Mary A, Hobbs Charlotte V, Dapul Heda, Feldstein Leora R, Jackson Ashley M, Mack Elizabeth H, Walker Tracie C, Maddux Aline B, Spinella Philip C, Loftis Laura L, Kong Michele, Rowan Courtney M, Bembea Melania M, McLaughlin Gwenn E, Hall Mark W, Babbitt Christopher J, Maamari Mia, Zinter Matt S, Cvijanovich Natalie Z, Michelson Kelly N, Gertz Shira J, Carroll Christopher L, Thomas Neal J, Giuliano John S, Singh Aalok R, Hymes Saul R, Schwarz Adam J, McGuire John K, Nofziger Ryan A, Flori Heidi R, Clouser Katharine N, Wellnitz Kari, Cullimore Melissa L, Hume Janet R, Patel Manish, Randolph Adrienne G. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2022;11(5):191–198. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piab123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Efficacy of Remdesivir (GS-5734TM) in Participants From Birth to < 18 Years of Age With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (CARAVAN) Clinicaltrials.gov. 2019. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04431453 https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04431453

- 29.Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 Pneumonia in a Newborn Treated With Remdesivir and Coronavirus Disease 2019 Convalescent Plasma. Hopwood Andrew J, Jordan-Villegas Alejandro, Gutierrez Liliana D, Cowart Mallory C, Vega-Montalvo Wilfredo, Cheung Wang Leung, McMahan Michael J, Gomez Michael R, Laham Federico R. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2021;10(5):691–694. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Infant With SARS-CoV-2 Infection Causing Severe Lung Disease Treated With Remdesivir. Frauenfelder Claire, Brierley Joe, Whittaker Elizabeth, Perucca Giulia, Bamford Alasdair. Pediatrics. 2020;146(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neonates With SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Pulmonary Disease Safely Treated With Remdesivir. Saikia Bedangshu, Tang Julian, Robinson Simon, Nichani Sanjiv, Lawman Kelly-Beth, Katre Mahesh, Bandi Srini. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2021;40(5):e194–e196. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Severe COVID-19 Complicated by Cerebral Venous Thrombosis in a Newborn Successfully Treated with Remdesivir, Glucocorticoids, and Hyperimmune Plasma. Cursi Laura, Calo Carducci Francesca Ippolita, Chiurchiu Sara, Romani Lorenza, Stoppa Francesca, Lucignani Giulia, Russo Cristina, Longo Daniela, Perno Carlo Federico, Cecchetti Corrado, Lombardi Mary Haywood, D'Argenio Patrizia, Lancella Laura, Bernardi Stefania, Rossi Paolo. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(24) doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinus Bradycardia in a Pediatric Patient Treated With Remdesivir for Acute Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Case Report and a Review of the Literature. Chow Eric J, Maust Branden, Kazmier Katherine M, Stokes Caleb. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2021;10(9):926–929. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piab029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinus Bradycardia in Children Treated With Remdesivir for COVID-19. Eleftheriou Irini, Liaska Marianthi, Krepis Panagiotis, Dasoula Foteini, Dimopoulou Dimitra, Spyridis Nikos, Tsolia Maria. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2021;40(9):e356. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Severe sinus bradycardia associated with Remdesivir in a child with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sanchez-Codez Maria Isabel, Rodriguez-Gonzalez Moises, Gutierrez-Rosa Irene. European journal of pediatrics. 2021;180(5):1627. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-03940-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in Febrile Neonates. Wardell Hanna, Campbell Jeffrey I, VanderPluym Christina, Dixit Avika. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2020;9(5):630–635. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SARS-CoV-2 attacks the weakest point - COVID-19 course in a pediatric patient with Friedreich's ataxia. Faltin Kamil, Lewandowska Zuzanna, Małecki Paweł, Czyż Krzysztof, Szafran Emilia, Kowalska-Tupko Agnieszka, Mania Anna, Mazur-Melewska Katarzyna, Jończyk-Potoczna Katarzyna, Bobkowski Waldemar, Figlerowicz Magdalena. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2022;117:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remdesivir during induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection. Orf Katharine, Rogosic Srdan, Dexter Daniel, Ancliff Phil, Badle Saket, Brierley Joe, Cheng Danny, Dalton Caroline, Dixon Garth, Du Pré Pascale, Grandjean Louis, Ghorashian Sara, Mittal Prabal, O'Connor David, Pavasovic Vesna, Rao Anupama, Samarasinghe Sujith, Vora Ajay, Bamford Alasdair, Bartram Jack. British journal of haematology. 2020;190(5):e274–e276. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.A 10-Year-old Girl With Late Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Recurrence Diagnosed With COVID-19 and Treated With Remdesivir. Gadzińska Justyna, Kuchar Ernest, Matysiak Michał, Wanke-Rytt Monika, Kloc Malgorzata, Kubiak Jacek Z. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2022;44(2):e537–e538. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.COVID-19 convalescent plasma clears SARS-CoV-2 refractory to remdesivir in an infant with congenital heart disease. Rodriguez Zahidee, Shane Andi L, Verkerke Hans, Lough Christopher, Zimmerman Matthew G, Suthar Mehul, Wrammert Jens, MacDonald Heather, Wolf Michael, Clarke Shanelle, Roback John D, Arthur Connie M, Stowell Sean R, Josephson Cassandra D. Blood advances. 2020;4(18):4278–4281. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Severe Pediatric COVID-19 Presenting With Respiratory Failure and Severe Thrombocytopenia. Patel Pratik A, Chandrakasan Shanmuganathan, Mickells Geoffrey E, Yildirim Inci, Kao Carol M, Bennett Carolyn M. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Remdesivir-Induced Liver Injury in a COVID-Positive Newborn. Kaur Manjit, Tiwari Deepika, Sidana Vishal, Mukhopadhyay Kanya. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2022;89(8):826. doi: 10.1007/s12098-022-04237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.COVID-19 and remdesivir in pediatric patients: the invisible part of the iceberg. Yalçın Nadir, Demirkan Kutay. Pediatric research. 2021;89(6):1326–1327. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapid review of suspected adverse drug events due to remdesivir in the WHO database; findings and implications. Charan Jaykaran, Kaur Rimple Jeet, Bhardwaj Pankaj, Haque Mainul, Sharma Praveen, Misra Sanjeev, Godman Brian. Expert review of clinical pharmacology. 2021;14(1):95–103. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2021.1856655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.COVID-19 and the Cardiovascular System: How the First PostModern Pandemic ‘Weakened’ our Hearts. Towhid Syeda Tasneem, Rakhi Nadira Naznin, Arefin ASM Shamsul, Saha Otun, Mamun Sumaiya, Moniruzzaman Mohammad, Rahaman Md. Mizanur. Discoveries Reports. 2020;3:e15. [Google Scholar]

- 46.COVID-19 impact on pre-existing liver pathologies. Kamwal C, Shivakumar J, Bhattarai S, Peethambar G, Gor D, Gor D. Discoveries Reports. 2021;4(3):e25. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cardiovascular events and safety outcomes associated with remdesivir using a World Health Organization international pharmacovigilance database. Jung Se Yong, Kim Min Seo, Li Han, Lee Keum Hwa, Koyanagi Ai, Solmi Marco, Kronbichler Andreas, Dragioti Elena, Tizaoui Kalthoum, Cargnin Sarah, Terrazzino Salvatore, Hong Sung Hwi, Abou Ghayda Ramy, Kim Nam Kyun, Chung Seo Kyoung, Jacob Louis, Salem Joe-Elie, Yon Dong Keon, Lee Seung Won, Kostev Karel, Kim Ah Young, Jung Jo Won, Choi Jae Young, Shin Jin Soo, Park Soon-Jung, Choi Seong Woo, Ban Kiwon, Moon Sung-Hwan, Go Yun Young, Shin Jae Il, Smith Lee. Clinical and translational science. 2022;15(2):501–513. doi: 10.1111/cts.13168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rethinking Remdesivir: Synthesis, Antiviral Activity, and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Lipid Prodrugs. Schooley Robert T, Carlin Aaron F, Beadle James R, Valiaeva Nadejda, Zhang Xing-Quan, Clark Alex E, McMillan Rachel E, Leibel Sandra L, McVicar Rachael N, Xie Jialei, Garretson Aaron F, Smith Victoria I, Murphy Joyce, Hostetler Karl Y. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2021;65(10):e0115521. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01155-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Large Remdesivir Study Finds No COVID-19 Survival Benefit. Medscape. 2021. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/954888?reg=1 https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/954888?reg=1

- 50.Cohen Jon, Kupferschmidt Kai. The “Very, Very Bad Look” of Remdesivir, the First FDA-Approved COVID-19 Drug. Science News. 2020. https://www.science.org/content/article/very-very-bad-look-remdesivir-first-fda-approved-covid-19-drug https://www.science.org/content/article/very-very-bad-look-remdesivir-first-fda-approved-covid-19-drug

- 51.Evolution of viral variants in remdesivir-treated and untreated SARS-CoV-2-infected pediatrics patients. Boshier Florencia A T, Pang Juanita, Penner Justin, Parker Matthew, Alders Nele, Bamford Alasdair, Grandjean Louis, Grunewald Stephanie, Hatcher James, Best Timothy, Dalton Caroline, Bynoe Patricia Dyal, Frauenfelder Claire, Köeglmeier Jutta, Myerson Phoebe, Roy Sunando, Williams Rachel, de Silva Thushan I, Goldstein Richard A, Breuer Judith. Journal of medical virology. 2022;94(1):161–172. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quality and consistency of clinical practice guidelines for treating children with COVID-19. Li Qinyuan, Zhou Qi, Xun Yangqin, Liu Hui, Shi Qianling, Wang Zijun, Zhao Siya, Liu Xiao, Liu Enmei, Fu Zhou, Chen Yaolong, Luo Zhengxiu. Annals of translational medicine. 2021;9(8):633. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-7000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]