Abstract

The binding performance of dissolved organic matters (DOM) plays a critical role in the migration, diffusion and removal of various residual pollutants in the natural water environment. In the current study, four typical DOMs (including bovine serum proteins BSA (proteins), sodium alginate SAA (polysaccharides), humic acid HA and fulvic acid FA (humus)) are selected to investigate the binding roles in zwitterionic tetracycline (TET) antibiotic under various ionic strength (IS = 0.001–0.1 M) and pH (5.0–9.0). The dialysis equilibration technique was employed to determine the binding concentrations of TET, and the influence of IS and pH on binding performance was evaluated via UV–vis spectroscopy, total organic carbon (TOC), and Excitation-Emission-Matrix spectra (EEM), zeta potentials and molecule size distribution analysis. Our results suggested that carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl were identified as the main contributors to TET binding based on the fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis, and the binding capability of four DOMs followed as HA > FA » BSA > SAA. The biggest binding concentrations of TET by 10 mg C/L HA, FA, BSA and SAA were 0.863 μM, 0.487 μM, 0.084 μM and 0.086 μM, respectively. The higher binding capability of HA and FA is mainly attributed to their richer functional groups, lower zeta potential (HA/FA = −15.92/-13.54 mV) and the bigger molecular size (HA/FA = 24668/27750 nm). IS significantly inhibits the binding interaction by compressing the molecular structure and the surface electric double layer, while pH had a weak effect. By combining the Donnan model and the multiple linear regression analysis, a modified Karickhoff model was established to effectively predict the binding performance of DOM under different IS (0.001–0.1 M) and pH (5.0–9.0) conditions, and the R2 of linear fitting between experiment-measured logKDOC and model-calculated logKOC were 0.94 for HA and 0.91 for FA. This finding provides a theoretical basis for characterizing and predicting the binding performance of various DOMs to residual micropollutants in the natural water environment.

Keywords: Dissolved organic matters, Tetracycline, Karickhoff model, pH, Ionic strength

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Effect of IS and pH on binding performance of four typical DOMs was evaluated.

-

•

Binding capability followed as HA > FA » BSA > SAA.

-

•

Carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl were identified as the main contributors to bind.

-

•

A modified Karickhoff model was established to predict the binding performance.

1. Introduction

In recent years, various antibiotics have been widely used in medical treatment, animal husbandry and aquaculture [1,2]. However, up to 58% of the unmetabolized components of those ingested antibiotics are re-discharged into the natural water environment due to their low bioavailability [3,4]. According to previous reports, as many as 68 residual antibiotics have been detected in the surface water environment of different river basins, with concentrations ranging from ng/L to mg/L [5,6]. Given that the residual antibiotics pose a serious potential threat to human health and the ecosystem through bioaccumulation and endocrine disruption [7], the researches on migration, transformation and toxic effects of residual antibiotics are a matter of urgency.

Residual antibiotics pose a strong intendancy to binding with dissolved organic matter (DOM) in the water environment, due to their abundant functional groups and double ionization structure [8,9], which will significantly affect their migration, conversion and removal during wastewater treatment processes [10,11]. As a complex organic mixture of decomposed and physicochemically altered biogenic material from a variety of sources, DOM is widely present in soil and aquatic ecosystems, which contains abundant constituents (humic substances, polysaccharides, and proteins) and functional groups (carboxyl, phenolic hydroxyl, amino, keto, etc.) [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. Given that DOM may act as proton donor or acceptor and pH buffering agent in water environment [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]], it has significant implications for toxicity, transport, phase distribution and bioavailability of organic pollutants [21,22]. Previous studies have revealed a binding reaction between DOM and clarithromycin through cation exchange, and polar interactions and hydrogen bonding to explain the binding of atrazine, phenanthrene and lindane to DOM, and also proposed electrostatic interactions and hydrophobic bonding [14,[23], [24], [25]]. However, a consensus on their underlying binding interaction mechanisms is still not established, and the structural features of DOM governing the binding interaction of residual organics remain largely unclear [25]. Furthermore, the binding performance between residual antibiotics and DOM molecules with different structures and functional groups still lacks deep research.

Previous studies have reported that the water chemistries, especially pH and ionic strength (IS), have a significant impact on the binding performance of DOM, since pH could affect the hydrolysis of functional groups and the ion distribution of residual zwitterions [[26], [27], [28]], while IS would destroy the molecular structure and compresses the double electric layers on molecule surface by electrostatic effect [27,29]. Zhao's research on the combination of enrofloxacin and humic acid (HA) reported that the binding constant would decrease from 0.27 to 0.06 L/mg with pH increase from 5.0 to 9.0, while Yang et al. have reported that the binding concentration of tetracycline (TET) on the DOMs would decrease from 0.8 to 0.58 μM with IS increase from 0.001 to 0.1 M [8,30]. However, no consistent results have been obtained because both negative and positive relationships have been reported between IS or pH and the binding coefficients [30,31]. To better fit the binding effect of the DOM under different pH and IS environmental conditions, various models are established and constantly modified, such as the classic Langmuir [32], Freundlich [33,34], affinity distribution Model VI [35], and continuous affinity distribution NICA-Donnan model [26,36]. Due to the differences of organic pollutants (pKa, hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity, functional groups and structures etc.), the adaptability of those models is still relatively limited, especially considering the impact of various IS and pH.

Previous scholars try to use the Karickhoff model to fit the binding performance, which applies octanol/water partition coefficient (Kow) to fit the organic carbon/water partition coefficient (Koc) [37], and combines the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation to taking account of the pH effect [38], but the impact of IS has not been considered. Thereby, the Karickhoff model needs to be further modified to adapt to changes of both pH and IS.

In the present study, zwitterionic tetracycline was selected as the target pollutant, and the binding performance of four typical dissolved organic compounds humic acid (HA), fulvic acid (FA), bovine serum protein (BSA), and sodium alginate (SAA) on tetracycline at various pH (5.0–9.0) and IS (0.001–0.1 M) were investigated. The dialysis bag equilibrium experiment was applied to determine the binding concentrations, and the UV–visible absorption spectra, total organic carbon (TOC) and Excitation-Emission-Matrix spectra (EEM) were employed to evaluate the effect of pH and IS, while the fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra were adopted to probe the function groups involving in binding. Besides, the changes of surface potential and molecular size of DOM were monitored by zeta potential and dynamic light scattering, respectively. Finally, based on the Donnan model and the multiple linear regression analysis, a modified Karickhoff model was established to effectively predict the binding performance of DOM under various pH and IS conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Suwannee River Humic Acid Standard III (HA, cat. #3S101H) and Suwannee River Fulvic Acid Standard III (FA, cat. #3S101F) were purchased from the International Humic Substances Society (IHSS). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), sodium alginate (SAA) and the acetonitrile (HPLC-grade) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Tetracycline hydrochloride (98%, GR) was supplied by TCI Co. Ltd. Perchloric acid (70%, GR), sodium perchlorate (98%, GR), sodium hydroxide (98%, GR) and phosphoric Acid were obtained from Chengdu Kelong Co., Ltd. The detailed structures and characteristics of the four DOMs were listed in Figs. S1a–S1d and Text. S1.

2.2. Sorption experiments

The dialysis processes were performed using Spectra/Por 6 dialysis bags (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) with a cut-off molecular weight of 1000 Da. The dialysis membrane stored in sodium azide was washed thoroughly with deionized water before use. Transfer 5 ml of 10 mg/L DOM samples to the dialysis bags (10 mm length × 20 mm diameter), and clamp the dialysis bags at both ends, then put it into the conical flask filled with deionized water. Pre-dialysis was performed with stirring at a speed of 30 r/min for 24 h in the dark. The water in the beaker was replaced at 4, 10, and 20 h, respectively, to remove DOM molecules fraction less than 1000 Da [39].

The dialysis bags containing the pre-dialyzed DOM were placed in a 100 ml reaction solution, in which the concentration of tetracycline (TET) was 5 μM, while the absence of TET was the control group. The pH was adjusted to 5.0–9.0 by 0.01 M NaOH and 0.01 M HClO4, and the IS was adjusted to 0.001–0.1 M by NaClO4 [36]. Conical flasks with reaction solution were shaken at 40 r/min for 48 h in the dark to completely dialysis balance. Finally, the solutions inside and outside the dialysis bag were taken for UV–visible absorption spectra, EEM, TOC and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis.

2.3. Analysis methods

Withdrawn samples were measured by HPLC (Waters e2695), equipped with a Waters Symmetry C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm) working at 35 °C, and a UV–visible detector (Waters 2489) set at 355 nm. The mobile phase was maintained at a 1.0 mL/min flow rate with a constant ratio (20 mM H3PO4/acetonitrile: 80/20). The binding concentration (Cbind) and DOC binding coefficient (KDOC) were calculated based on Eqs. (1), (2)):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Cin and Cout are the TET concentration inside and outside the dialysis bag, Cbind (μM) is the binding concentration, and [DOC] (mg/L) is the concentration of DOM inside the dialysis bag.

The UV–visible absorption spectra were measured on a spectrophotometer (Mapada UV-1800) at the range of 200–400 nm. TOC was analyzed by a multi-N/C 3100 analyzer (Analytikjena). Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 700 V xenon lamp and a 1 cm quartz cell was employed to the detection of the fluorescence EEM spectra. The excitation and emission wavelength range of both HA and FA were set as 200–450 nm and 250–550 nm, while BSA was set as 200–350 nm and 250–500 nm at an interval of 5 nm. Since SAA has no fluorescence response, no EEM spectra measurement has been performed.

To explore the mechanisms responsible for DOMs binding TET, the high concentration solutions of HA/FA/BSA/SAA-TET mixture were prepared to get better Fourier Transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and freeze dried. All FTIR spectra of the obtained mixture particles, HA/FA/BSA/SAA particles, and TET particles were collected in a 600–4000 cm−1 range with a resolution of 4 cm−1, and 60 scans by FTIR Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Nicolet Is5) equipped with a Germanium attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory.

An AccuSizer 780 particle sizer (Santa Barbara, USA) was employed to determine the distribution particle sizes of DOM. Zeta potentials of DOM at different pH values (5.0, 7.0 and 9.0) and IS (0–0.1 M) were measured in quadruplicate by a zeta potential analyzer (NICOMP 380) at 25 °C.

2.4. Determination of partition coefficients

The distribution of TET between organic carbon and water (KOC) could be rough predicted based on the octanol-water partition coefficient (KOW), according to the Karickhoff model [40] (Eq. (3)).

| (3) |

The KOW of the substance is suitable for compounds that exist only in the non-ionic form at a given pH. Zwitterionic tetracyclines are usually present in aqueous solutions in both non-ionic and ionic forms Fig. S2b. At a given pH, the non-ion to ion ratio of a compound is usually adjusted by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, and the dissociation partition coefficient (D) is calculated through Eqs. (4), (5)) [41]. Considering that this study focuses on natural water bodies, the research range of pH is selected from 5.0 to 9.0. The molecular information and ionic distribution of tetracycline are shown in Figs. S2a–2b and Text. S2.

| (4) |

| (5) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Binding performance with four DOMs

The binding performance of HA, FA, BSA, and SAA on TET under different pH (5.0, 7.0 and 9.0) and IS (0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 M) conditions are investigated. As shown in Fig. 1, the binding capacity of DOM molecules on TET was in the following order: HA > FA » BSA > SAA. Prior studies have proved that the carboxylic and phenolic hydroxyl played a critical role in binding interaction between DOM and micropollutants [30,42], so that the richer content of the two functional groups for HA and FA molecules contributed to their greater binding capacity, compared to BSA and SAA molecules. Due to that, the ionization constants (pKa) of carboxyl groups and phenolic groups are about 3.0 and 10.0 [43], respectively, the carboxyl groups were almost ionized at the experimental pH range (5.0–9.0), which played the dominant role in TET binding [44]. Compared to FA molecules, the higher binding capacity of HA on TET might be owing to the higher degree of polymerization of HA molecules, which made HA molecules more stable against the disturbance of pH and IS [45]. As for the negative concentration difference (ΔCbind = Cin-Cout) for BSA, it might be owing to that BSA molecules tended to adsorb small molecular anions due to the amino protonation, which inhibited TET binding, while the unique chain structure of SAA was not conducive to the combination of TET.

Fig. 1.

TET binding performance on HA (a), FA (b), BSA (c) and SAA (d) ([HA] = [FA] = [BSA] = [SAA] = 10 mg/L, [TET] = 5 μM, IS 0.001–0.1 M, pH 5.0–9.0).

As illustrated in Fig. 1a and b, the binding capacity increased with pH for HA, but decreased with pH for FA. Due to the electrostatic neutralization of deprotonated groups, compared with FA, HA with a more compact molecule configuration would hinder the combination of TET and DOM at low pH [46]. However, as pH increased from 5.0 to 9.0, the electrostatic repulsion effect gradually dominated the binding of TET. This was ascribed to the conversion from TET± to TET- (Fig. S2), and the increase of negative surface charge due to the further deprotonation of phenolic hydroxyl groups of DOMs. In terms of the effect of IS, both HA and FA showed a negative correlation with IS in TET binding, which might be owing to the competitive adsorption between cationic with TET-. Besides, the higher IS would destroy the size and structure of DOM molecules. As for the BSA, the binding concentration of TET increased slightly with the increase of IS, since it would adsorb counter ions to neutralize the negative surface charge [47], weakening the electrostatic repulsion with TET-.

3.2. Evolution of DOMs and TET binding sites

To explore the mechanisms responsible for DOMs binding TET, the FTIR spectra of the obtained mixture particles, HA/FA/BSA/SAA particles, and TET particles were collected in a 600–4000 cm−1 range (Fig. 2). The bands of 1709, 1614, and 1576 cm−1 were assigned to stretching vibrations of carboxylic acid C O, ketone C O and antisymmetric stretch of carboxylate COO- [42]. The peaks located at 1450, 1387 and 1411 cm−1 corresponded to the stretch C–N stretching vibration, C–O symmetric stretching and COO- symmetric stretching, while the 1206 and 1036 cm−1 were attributed to the O–H stretching vibrations of phenol and alcohol [22]. As for the HA and FA, the peaks intensity of 1709, 1206 and 1036 cm−1 decreased after binding with TET, indicating that the carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups played a circle role in binding interaction, which was consistent with our previous study [8]. Additionally, the increase of weak peaks located at 1576 and 1450 cm−1 in HA-TET and FA-TET suggested that the TET was not mechanically mixed with the HA and FA but chemically bound to them [21]. In terms of BSA, the peak of 1450 cm−1 decreased significantly, proving that the carboxyl groups were identified as the major contributor to the binding role, while the intensity decrease of 1036 and 1411 cm−1 revealed that the carboxyl and hydroxyl groups of SAA were involved in the binding interaction. Based on the above analysis, the carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups were the main contributors to the binding of DOMs to TET, which could explain the difference in the binding ability of the four DOMs.

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectra of free HA/FA/BSA/SAA particles, free TET particles and HA/FA/BSA/SAA-TET mixture particles.

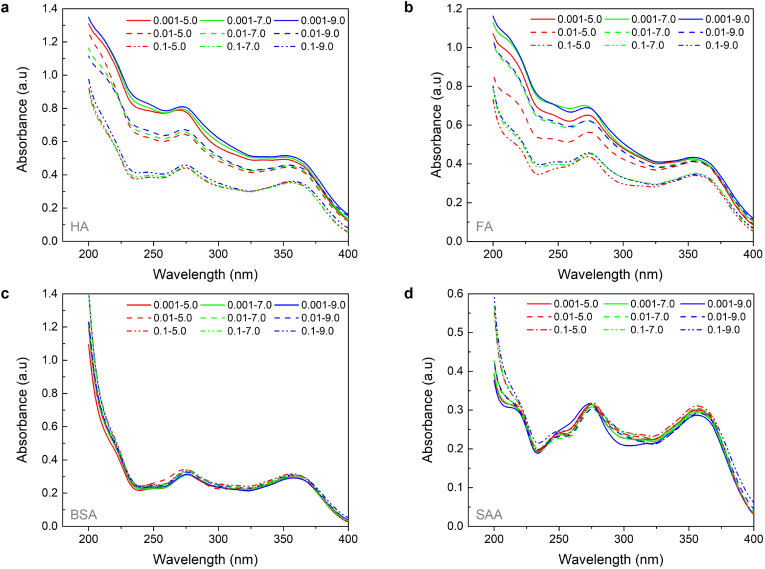

3.3. Evolution of UV–vis spectra, TOC and fluorescence quenching

Fig. 3a–d are the UV–visible light absorption spectra of HA, FA, BSA and SAA combined with TET. The absorption peaks at 275 nm and 355 nm are characteristic absorption peaks of TET. Compared to BSA and SAA, the UV absorption intensity for HA and FA decreased significantly with IS increase from 0.001 M to 0.1 M, confirming that IS had a greater impact on the molecular structure of HA and FA, which was consistent with the binding performance of DOM molecules [48].

Fig. 3.

UV–vis spectra of HA (a), FA (b), BSA (c) and SAA (d) after binding balance with TET ([HA] = [FA] = [BSA] = [SAA] = 10 mg/L, [TET] = 5 μM, value - value represents IS(M)-pH).

The UV absorbance at 254 nm (UV254) is a characteristic parameter of DOM molecular abundance in natural waters [49]. Thus, the UV254 of HA and FA was selected as an auxiliary indicator of TET binding, and the linear fitting between UV254 after binding balance and Cbind of HA and FA was performed (Fig. S3). The slope value (k) reflected the influence of pH on binding interaction under different IS background conditions. With the increase of IS from 0.001 M to 0.1 M, the k decreased 7.5 times for HA and 2.8 times for FA, indicating that the effect of pH on TET binding would be significantly suppressed at high IS, especially for HA.

The △TOC (the difference between inside and outside of dialysis bag) was monitored to further explore the binding performance of DOM molecules under different conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 4a and b, the △TOC decreased significantly with the increase of IS for both HA and FA, which might be attributed to the weakening of TET binding; moreover, the molecules of HA and FA were compressed to pass through the dialysis bag freely. Due to the chain structure of SAA [50], the changes of △TOC were not sensitive to IS and pH (Fig. 4d). Of note, the changes of △TOC of BSA were positively correlated with IS (Fig. 4c), which attributed to the increase of TET binding, and the polymerization of BSA reduced the loss of small molecule fragments.

Fig. 4.

Difference of TOC between internal and external dialysis bag of the HA (a) and (b) FA, BSA (c) and SAA (d) after binding balance with TET ([HA] = [FA] = [BSA] = [SAA] = 10 mg/L, [TET] = 5 μM, IS 0.001–0.1 M, pH 5.0–9.0).

Fig. 5a, c and 5e are the EEM spectra of HA, FA, and BSA, and the spectra after binding with TET at pH 5.0–9.0 and IS 0.001–0.1 M were listed at Figs. S4–S6, respectively. The EEM analysis was not performed on SAA, since it has no fluorescence response. The fluorescence peaks of HA are located at 275/465 nm (Ex/Em) and 320/465 nm, the fluorescence peaks of FA are located at 275/450 nm and 320/450 nm, and the fluorescence peaks of BSA are located at 230/340 nm and 280/340 nm. Previous studies reported that the binding interaction between DOM and organic contaminants would result in fluorescence quenching [30,51]. Herein, the fluorescence quenching rates caused after binding balance were summarized in Fig. 5b, d and 5f. In terms of the HA and FA molecules, the effect of IS on the fluorescence intensity rates was bigger than pH, indicating a greater influence on binding interaction. Additionally, the fluorescence quenching rate presented a positive relationship with IS for HA and FA, but a negative relationship for BSA, which might be attributed to that IS would eliminate the electrostatic repulsion between BSA peptide chains and weaker protein aggregation. This was in line with the results of the TOC analysis.

Fig. 5.

EEM spectra of HA (a), FA (c) and BSA (e); fluorescence quenching rate of the HA (b), FA (d) and BSA (f) after binding balance with TET ([HA] = [FA] = [BSA] = 10 mg/L, [TET] = 5 μM, IS 0.001–0.1 M, pH 5.0–9.0).

3.4. Zeta potential variation of DOM bound with TET

Given that the electrostatic effect was the main force in the binding interaction between DOMs combined with TET, the zeta potentials of four DOMs under different pH and IS conditions were detected to monitor surface charge changes (Fig. 6). Due to the deprotonation of the carboxyl groups, the zeta potentials of four DOM molecules were negative at the initial dissolution conditions, from small to large as HA < FA < SAA < BSA (Fig. S7). The higher negative charges indicated a higher electronic double layer potential of the DOM molecules, which were more conducive to the electrostatic combination of DOMs and TET [27]. The changes of zeta potentials under various pH suggested that the zeta potentials of HA and FA were more sensitive to pH than SAA (Fig. 6a), due to conjugation and induction effects led to that the phenolic hydroxyl groups were easier to ionize than the alcoholic hydroxyl groups. However, the zeta potentials gradually increased with IS increase (Fig. 6b), since that IS would compress the electric double layer and Na+ would combine with the deprotonated functional groups [52].

Fig. 6.

Changes of DOM molecules' zeta potentials with pH (a) and IS (b) ([HA] = [FA] = [BSA] = [SAA] = 10 mg/L, pH for pristine is 5.5).

3.5. Behavior of size distribution of DOM bound with TET

Given that IS has a significant impact on the structure and electronegativity of DOM molecules, the size distributions of HA, FA, BSA, and SAA under the conditions of IS = 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 M were investigated (Fig. S8). Of note, the mean diameter of HA and FA were 24668 nm and 27750 nm, respectively, while the average molecular sizes of BSA and SAA were only 106 nm and 2542 nm (Fig. 7) [53]. The larger molecular sizes demonstrated that HA and FA contained more binding sites compared to BSA and SAA, which was consistent with the results of the TET binding experiments. Since the intra-molecular electrostatic repulsion was weakened and the molecular structure would be destroyed, all the DOM molecule sizes were decreased with the IS increase. The HA and BSA molecular sizes were compressed by nearly 27 and 5 times, respectively, while FA and SAA molecular sizes were 106 and 103 times, revealing that the molecular structures of FA and SAA were more unstable to IS.

Fig. 7.

Changes of DOM molecules' mean diameter with IS ([HA] = [FA] = [BSA] = [SAA] = 10 mg/L, IS 0.001–0.1 M, pH 5.5).

The changes of zeta potentials and molecular sizes of DOMs inevitably caused varies in the molecular electric double layer, which was related to the binding performance. The Donnan model was proved to well explain the electrostatic adsorption of the DOM binding effect [54], and the Donnan volume (VD) as a circle parameter could better describe the electric double layer and potential changes [29], which was closely related to the IS (Eq. (6) and Text. S3) [29,54,55]. To determine the indirect relationship between IS and binding performance, the VD values calculated by the Donnan model were fitted to the KDOC parameters obtained from the experiment, and the results are shown in Fig. 8. A significant linear relationship between VD and KDOC under various IS conditions indicated that the IS had a significant effect on the electrostatic effect of DOM binding.

| (6) |

where b is an adjustable parameter, IS and VD are the ionic strength and Donnan volume, respectively. Based on Milne's study [55], the b values of HA and FA were selected as bHA = 0.51 and bFA = 0.63 in this study.

Fig. 8.

Correlation analysis between KDOC and Donnan volume VD for HA (a) and FA (b).

3.6. Binding model fitting performance

KOC could be predicted by the dissociation partition coefficient (D) based on the Karickhoff model, which was related to KOW, pKa of TET and environmental pH. Given that the IS also played a vital role in binding performance, the Karickhoff model was modified to better adapt the effect of different IS and pH (Eq. (7)), and the parameters k1, k2, and c are obtained by regression analysis.

| (7) |

The linear regression analysis was performed to calculate the parameters for HA and FA, except for BSA and SAA due to their weak binding capacity, and the results are listed in Table 1. The higher correlation coefficient R2 and the lower residual sum of squares (RSS) demonstrated that the established model has good adaptability and stability to HA and FA. The experimentally determined logarithmic partition coefficient (log KDOC) for the distribution of TET between DOM and water was plotted against a model predicted logarithmic organic carbon partition coefficient (log KOC) to verify the reliability of the model. As illustrated in Fig. 9, the significant linear relationship between log KDOC and log KOC for HA molecules (R2 = 0.94) and FA molecules (R2 = 0.91) confirmed that the modifying Karickhoff model could achieve better prediction for the binding interaction between TET and DOM molecules under different IS and pH conditions.

Table 1.

Parameters of logKOC model calculated by linear regression analysis.

| DOM | k1 | k2 | c | RSS | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 0.053 | −0.220 | −2.250 | 0.018 | 0.92 |

| FA | −0.118 | −0.186 | −2.630 | 0.033 | 0.83 |

Fig. 9.

Correlation analysis between experimentally determined logKDOC and the model predicted logKOC for HA (a) and FA (b).

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effects of IS (0.001–0.1 M) and pH (5.0–9.0) on the binding performance of HA, FA, BSA, and SAA to TET were investigated systematically. Due to the difference in molecular size, structure and surface potential, the binding capacity of different DOM molecules varies widely, and the sequence 10 mg C/L DOMs biggest binding concentration can be ordered as follows: HA (0.863 μM) >FA(0.487 μM) »BSA(0.084 μM) >SAA (0.086 μM). The results of dialysis experiments indicated that IS would inhibit the binding capacity of both HA and FA, slightly increase the binding capacity of BSA, but does not affect SAA. As for pH, which was positively correlated with HA and BSA binding capacity, and negatively correlated with FA. The results of the UV–vis spectrum, TOC measurement, and fluorescence quenching revealed that IS had a stronger effect on binding performance than pH, and FA was more sensitive to IS compared to other DOM molecules. As the IS increased from 0.001 to 0.1 M, the size of the average HA, FA, BSA and SAA molecules would be compressed by nearly 27, 106, 5 and 103 times, respectively, while the zeta potentials would decrease −20.63, −10.52, −18.70 and −5.10 mV respectively with pH increase from 5.0 to 9.0. The electrostatic interaction was verified as the main contributor to binding interaction by linear correlation analysis between Donnan volume and KDOC. Based on the Donnan model and the multiple linear regression analysis, a modified Karickhoff model was established, which was proved to effectively predict the binding performance of DOM under different IS and pH conditions, due to a significant linear relationship (R2 = 0.94 for HA and R2 = 0.91 for FA) between experiment-measured logKDOC and model-calculated logKOC.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China [NO. 51878422] and [NO.42177060], Science and Technology Bureau of Chengdu [2017-GH02-00010-342 HZ] and [2021-YF05-00350-SN], Innovation Spark Project in Sichuan University [Grant No. 2082604401254] for the financial support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2021.100133.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Mo W.Y., Chen Z., Leung H.M., Leung A.O. Application of veterinary antibiotics in China's aquaculture industry and their potential human health risks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017;24:8978–8989. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5607-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Q., Yi P., Dong W., Chen Y.H., He L.P., Pan B. Decisive role of adsorption affinity in antibiotic adsorption on a positively charged MnFe2O4@CAC hybrid. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:745. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q.Q., Ying G.G., Pan C.G., Liu Y.S., Zhao J.L. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:6772–6782. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi Z.X., Liu R.T., You H., Wang D.L. Binding of the veterinary drug tetracycline to bovine hemoglobin and toxicological implications. J. Environ. Sci. Health. 2014;49:978–984. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2014.951587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutgersson C., Fick J., Marathe N., Kristiansson E., Janzon A., Angelin M., Johansson A., Shouche Y., Flach C.F., Larsson D.G.J. Fluoroquinolones and qnr genes in sediment, water, soil, and human fecal flora in an environment polluted by manufacturing discharges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:7825–7832. doi: 10.1021/es501452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li B., Zhang T. Different removal behaviours of multiple trace antibiotics in municipal wastewater chlorination. Water Res. 2013;47:2970–2982. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao S.C., Hu Y.Y., Cheng J.H., Chen Y.C. Research progress on distribution, migration, transformation of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in aquatic environment. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018;38:1195–1208. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2018.1471038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang B., Wang C., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Li W., Wang J., Tian Z., Chu W., Korshin G.V., Guo H. Water Research; 2021. Interactions between the Antibiotic Tetracycline and Humic Acid: Examination of the Binding Sites, and Effects of Complexation on the Oxidation of Tetracycline; p. 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H., Yao H., Sun P., Li D., Huang C.H. Transformation of tetracycline antibiotics and Fe(II) and Fe(III) species induced by their complexation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:145–153. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibley S.D., Pedersen J.A. Interaction of the macrolide antimicrobial clarithromycin with dissolved humic acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:422–428. doi: 10.1021/es071467d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang B., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Li W., Wang J., Guo H. Insight into the role of binding interaction in the transformation of tetracycline and toxicity distribution. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology. 2021;8 doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2021.100127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longstaffe J.G., Simpson M.J., Maas W., Simpson A.J. Identifying components in dissolved humic acid that bind organofluorine contaminants using 1H 19F reverse heteronuclear saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:5476–5482. doi: 10.1021/es101100s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nebbioso A., Piccolo A. Molecular characterization of dissolved organic matter (DOM): a critical review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;405:109–124. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philippe A., Schaumann G.E. Interactions of dissolved organic matter with natural and engineered inorganic colloids: a review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:8946–8962. doi: 10.1021/es502342r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Guo Y., Pan Y., Yang X. Distinct effects of copper on the degradation of β-lactam antibiotics in fulvic acid solutions during light and dark cycle. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology. 2020;3 doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2020.100051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keiluweit M., Kleber M. Molecular-level interactions in soils and sediments: the role of Aromatic π-systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:3421–3429. doi: 10.1021/es8033044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen T.H., Goss K.-U., Ball W.P. Polyparameter linear free energy relationships for estimating the equilibrium partition of organic compounds between water and the natural organic matter in soils and sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:913–924. doi: 10.1021/es048839s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ke R., Luo J., Sun L., Wang Z., Spear P.A. Predicting bioavailability and accumulation of organochlorine pesticides by Japanese medaka in the presence of humic acid and natural organic matter using passive sampling membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:6698–6703. doi: 10.1021/es0707355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Li W., Wang J., Tian Z., Du E., Guo H. Staged assessment for the involving mechanism of humic acid on enhancing water decontamination using H2O2-Fe(III) process. J. Hazard Mater. 2020;407:124853. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng H., Liu M., Zeng W., Chen Y. Optimization of the O3/H2O2 process with response surface methodology for pretreatment of mother liquor of gas field wastewater. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021;15 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren D., Huang B., Yang B., Pan X., Dionysiou D.D. Mitigating 17alpha-ethynylestradiol water contamination through binding and photosensitization by dissolved humic substances. J. Hazard Mater. 2017;327:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu Q.L., He J.Z., Blaney L., Zhou D.M. Roxarsone binding to soil-derived dissolved organic matter: insights from multi-spectroscopic techniques. Chemosphere. 2016;155:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Vecchio R., Schendorf T.M., Blough N.V. Contribution of quinones and Ketones/Aldehydes to the optical properties of humic substances (HS) and chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:13624–13632. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b04172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei K., Han X., Fu G., Zhao J., Yang L. Mechanism of ofloxacin fluorescence quenching and its interaction with sequentially extracted dissolved organic matter from lake sediment of Dianchi, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014;186:8857–8864. doi: 10.1007/s10661-014-4049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X., Guo X., Yang Y., Tao S., Xing B. Sorption mechanisms of phenanthrene, lindane, and atrazine with various humic acid fractions from a single soil sample. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:2124–2130. doi: 10.1021/es102468z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christl I., Ruiz M., Schmidt J.R., Pedersen J.A. Clarithromycin and tetracycline binding to soil humic acid in the absence and presence of calcium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:9933–9942. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan B., Ghosh S., Xing B.S. Dissolved organic matter conformation and its interaction with pyrene as affected by water chemistry and concentration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:1594–1599. doi: 10.1021/es702431m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Z.J., Jiang C.C., Guo Q., Li J.W., Wang X.X., Wang Z., Jiang J. A novel diagnostic method for distinguishing between Fe(IV) and (∗)OH by using atrazine as a probe: clarifying the nature of reactive intermediates formed by nitrilotriacetic acid assisted Fenton-like reaction. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;417:126030. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milne C.J., Kinniburgh D.G., Tipping E. Generic NICA-donnan model parameters for proton binding by humic substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:2049–2059. doi: 10.1021/es000123j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X., Hu Z., Yang X., Cai X., Wang Z., Xie X. Noncovalent interactions between fluoroquinolone antibiotics with dissolved organic matter: a (1)H NMR binding site study and multi-spectroscopic methods. Environ. Pollut. 2019;248:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carmosini N., Lee L.S. Ciprofloxacin sorption by dissolved organic carbon from reference and bio-waste materials. Chemosphere. 2009;77:813–820. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Z., Mao L., Xian Q., Yu Y., Li H., Yu H. Effects of dissolved organic matter from sewage sludge on sorption of tetrabromobisphenol A by soils. J. Environ. Sci. 2008;20:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(08)62152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan S., Zhang D., Song W. Mechanistic considerations of photosensitized transformation of microcystin-LR (cyanobacterial toxin) in aqueous environments. Environ. Pollut. 2014;193:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulshrestha P., Giese R.F., Aga D.S. Investigating the molecular interactions of oxytetracycline in clay and organic matter:insights on factors affecting its mobility in soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38:4097–4105. doi: 10.1021/es034856q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi Z., Di Toro D.M., Allen H.E., Sparks D.L. A general model for kinetics of heavy metal adsorption and desorption on soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:3761–3767. doi: 10.1021/es304524p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan M., Han X., Zhang C. Investigating the features in differential absorbance spectra of NOM associated with metal ion binding: a comparison of experimental data and TD-DFT calculations for model compounds. Water Res. 2017;124:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong J., Ran Y., Chen D., Yang Y., Zeng E.Y. Association of endocrine-disrupting chemicals with total organic carbon in riverine water and suspended particulate matter from the Pearl River, China. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012;31:2456–2464. doi: 10.1002/etc.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magnér J., Alsberg T., Broman D. The ability of a novel sorptive polymer to determine the freely dissolved fraction of polar organic compounds in the presence of fulvic acid or sediment. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009;395:1525–1532. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maoz A., Chefetz B. Sorption of the pharmaceuticals carbamazepine and naproxen to dissolved organic matter: role of structural fractions. Water Res. 2010;44:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karickhoff S.W. Semi-empirical estimation of sorption of hydrophobic pollutants on natural sediments and soils. Chemosphere. 1981;10:833–846. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magner J.A., Alsberg T.E., Broman D. The ability of a novel sorptive polymer to determine the freely dissolved fraction of polar organic compounds in the presence of fulvic acid or sediment. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009;395:1525–1532. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan W., Zhang J., Jing C. Adsorption of Enrofloxacin on montmorillonite: two-dimensional correlation ATR/FTIR spectroscopy study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;390:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng F., Yuan G., Wei J., Bi D., Wang H. Leonardite-derived humic substances are great adsorbents for cadmium. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017;24:23006–23014. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9947-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei J., Tu C., Yuan G., Zhou Y., Wang H., Lu J. Limited Cu(II) binding to biochar DOM: evidence from C K-edge NEXAFS and EEM-PARAFAC combined with two-dimensional correlation analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;701:134919. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klučáková M. Conductometric study of the dissociation behavior of humic and fulvic acids. React. Funct. Polym. 2018;128:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones K.D., Tiller C.L. Effect of solution chemistry on the extent of binding of phenanthrene by a soil humic acid: a comparison of dissolved and clay bound humic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999;33:580–587. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medda L., Barse B., Cugia F., Bostrom M., Parsons D.F., Ninham B.W., Monduzzi M., Salis A. Hofmeister challenges: ion binding and charge of the BSA protein as explicit examples. Langmuir. 2012;28:16355–16363. doi: 10.1021/la3035984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen W., Yu H.Q. Advances in the characterization and monitoring of natural organic matter using spectroscopic approaches. Water Res. 2021;190:116759. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin H., Guo L. Variations in colloidal DOM composition with molecular weight within individual water samples as characterized by flow field-flow fractionation and EEM-PARAFAC analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:1657–1667. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b07123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang D.L., Xue W.J., Zeng G.M., Wan J., Chen G.M., Huang C., Zhang C., Cheng M., Xu P.A. Immobilization of Cd in river sediments by sodium alginate modified nanoscale zero-valent iron: impact on enzyme activities and microbial community diversity. Water Res. 2016;106:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L., Liang N., Li H., Yang Y., Zhang D., Liao S., Pan B. Quantifying the dynamic fluorescence quenching of phenanthrene and ofloxacin by dissolved humic acids. Environ. Pollut. 2015;196:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan Z.-r., Zhu Y.-y., Meng H.-s., Wang S.-y., Gan L.-h., Li X.-y., Xu J., Zhang W. Insights into thermodynamic mechanisms driving bisphenol A (BPA) binding to extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of activated sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;677:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dukhin A.S., Parlia S. Measuring zeta potential of protein nano-particles using electroacoustics. Colloids Surf., B. 2014;121:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benedetti M.F., Van Riemsdijk W.H., Koopal L.K. Humic substances considered as a heterogeneous donnan gel phase. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996;30:1805–1813. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milne C.J., Kinniburgh D.G. Generic NICA-donnan model parameters for proton binding by humic substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;35:2049–2059. doi: 10.1021/es000123j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.