Abstract

Objective:

To develop deep learning models to recognize ophthalmic examination components from clinical notes in electronic health records (EHR) using a weak supervision approach.

Methods:

A corpus of 39,099 ophthalmology notes labeled for 24 examination entities was assembled from the EHR of one academic center using a weakly supervised approach. Four pre-trained transformer-based language models (DistilBert, BioBert, BlueBert, and ClinicalBert) were fine-tuned to this named entity recognition task and compared to a baseline regular expression model. Models were evaluated on the weakly labeled test dataset, a human-labeled sample of that set, and a human-labeled independent dataset.

Results:

On the weakly labeled set, all transformer-based models had recall >0.92, with precision varying from 0.44-0.85. The baseline model had lower recall (0.77) and comparable precision (0.68). On the human-annotated sample, the baseline model had high recall (0.96) with variable precision across entities (0.11-1.0). All Bert models had recall ranging from 0.77-0.84, and precision >=0.95. On the independent dataset, precision was 0.93 and recall 0.39 for BlueBert. The baseline model had better recall (0.72) but worse precision (0.44).

Conclusion:

We developed the first deep learning system to recognize eye examination components from clinical notes, leveraging a novel opportunity for weak supervision. Transformer-based models had high precision on human-annotated labels, whereas the baseline model had poor precision but higher recall. This system may be used to improve cohort design and feature identification using free-text clinical notes, and our weakly supervised approach may help amass large datasets of domain-specific entities from EHRs in other fields.

Keywords: natural language processing, named entity recognition, weak supervision, deep learning, ophthalmology, electronic health records

INTRODUCTION

More information than ever is stored in free-text notes within the electronic health record (EHR), including detailed descriptions of patients’ symptoms, examination, and the physician's assessment and plan. Automated extraction of this information could provide the basis for efficiently defining research cohorts by clinical phenotype or treatment trajectory and developing predictive models for patient outcomes. Especially critical in ophthalmology is the eye examination portion of clinical notes, which details patients’ anterior and posterior eye segment exams. Without fast methods to collect these critical findings, the abilities to characterize ophthalmology cohorts and build predictive models are severely hampered.

A major challenge in identifying this information is that clinical free-text notes are unstructured and require natural language processing (NLP) techniques to process, understand, and compute over. Transformer-based deep learning architectures such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers)[1] and its descendants have ushered in a revolution in performance on many NLP tasks, including named entity recognition (NER) tasks. Extensions of BERT to the biomedical domain are also available, including BioBert,[2] pretrained on biomedical literature; ClinicalBert [3,4] and BlueBert,[5] pretrained on biomedical literature and critical care EHR notes; and DistilBert,[6] a smaller version of BERT with 40 percent fewer parameters. These models have performed well on benchmark biomedical named entity tasks such as recognizing disease entities.[2-5,7] However, there have not been efforts to use these NLP models to perform NER for the abovementioned ophthalmology exam components. The most advanced previous work extracted visual acuity measurements from free-text progress notes using a rule-based text-processing approach.[8]

A critical barrier to the use of BERT-based models to perform NER in ophthalmology is the lack of appropriately large and annotated corpora for model training, a barrier shared by everyone desiring to use these models for real-world or domain-specific tasks outside of benchmark datasets. Manual annotations on clinical notes require expertise and are time-consuming and difficult to produce on a scale sufficiently large to train BERT models. Thus, this study sought to use a weakly supervised approach requiring minimal manual annotation of training corpora in order to build and evaluate transformer-based deep learning models that can identify elements of the anterior segment (slit lamp) exam (SLE) and posterior segment (fundus) exam (FE) and their lateralities from free-text ophthalmology clinical notes. The goal was to train models for our domain-specific task using readily available weakly labeled data from EHRs and compare model performance against a smaller subset of human-annotated data. In doing so, we aimed develop the first models that researchers could eventually use to characterize ophthalmology patients based on granular clinical findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

We identified from the Stanford Research Repository (STARR)[9] all of the encounters with associated clinical progress notes, slit lamp examinations, and fundus examinations of patients who were seen by the Department of Ophthalmology at Stanford University since 2008. This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Preprocessing Labels

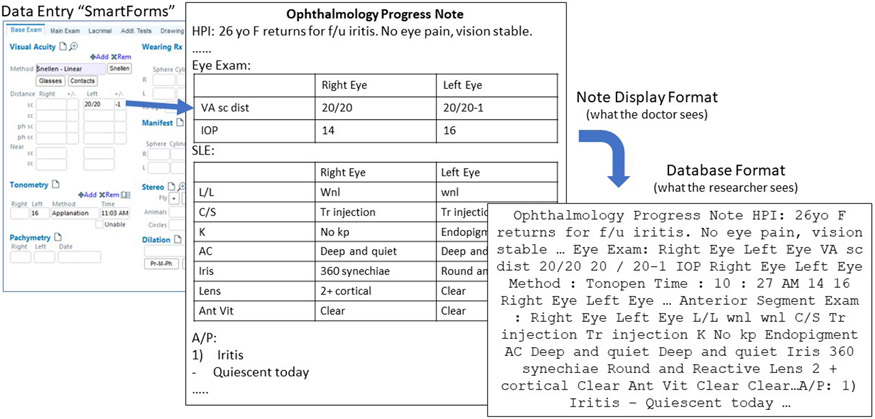

Some physicians use semi-structured fields ("SmartForms") to document eye examination observations. SmartForms are a feature of the EHR (Epic Systems) used to document semi-structured text which are commonly used in many deployments of this system and in multiple specialties including ophthalmology. Information entered into SmartForms is often imported into the clinical free-text note using providers' custom note templates. Thus, pairs of SmartForms and corresponding clinical notes represent notes which are labeled with the clinical exam information. Figure 1 illustrates such a pair. There are many different types of examination measurements, for each of the right and left eyes. A summary of the eye exam components and their abbreviations is given in Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 1. Example SmartForm and corresponding clinical progress note.

The leftmost panel shows the SmartForm template which clinicians use to enter text documenting different parts of the eye exam into discrete labeled fields. This information can then be imported via customizable templates into each clinician’s progress notes. The progress notes are then stored into a research database. VA = visual acuity; sc = counting fingers; IOP = intra-ocular pressure; L/L = lids and lashes; C/S = conjunctiva and sclera; K = cornea; AC = anterior chamber; Ant Vit = anterior vitreous; HPI = history of present illness; f/u = follow-up.

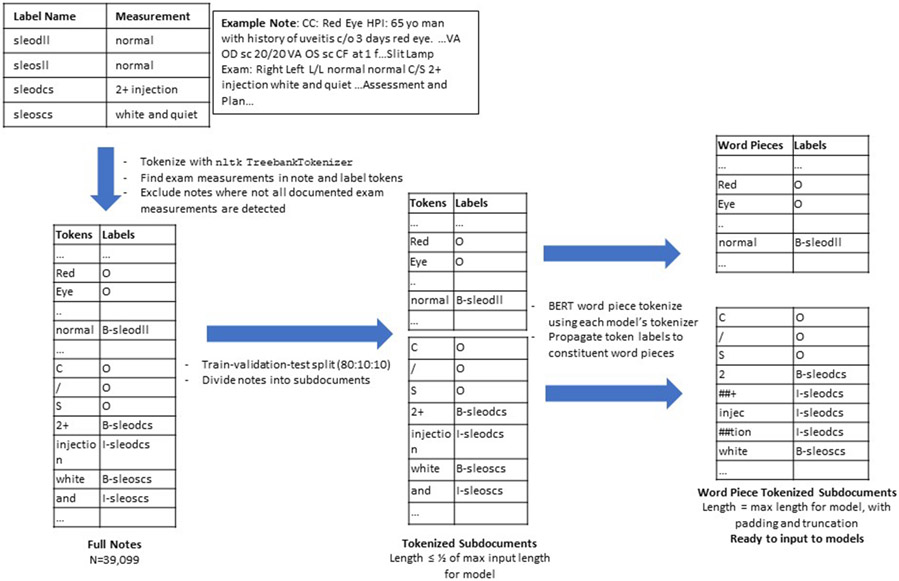

Although we have the exam information in the SmartForms and the corresponding free-text note into which that information is imported, we do not know exactly which words (tokens) in the note correspond to each examination finding, particularly in cases where multiple findings have the same description, such as “normal”, resulting in these descriptions appearing many times in the same note. Therefore, a custom preprocessing pipeline was developed to assign token-level labels for each document ("training labels"), illustrated in Figure 2. Each document was pre-tokenized using the Treebank Tokenizer in the Python Natural Language ToolKit v3.5.[10] For each component of an eye exam (“label”, e.g. “conjunctiva/sclera”), we identified the finding (e.g. “white and quiet”) documented in the SmartForm, then searched the patient’s note for these tokens and labeled them accordingly. If the token search yielded multiple matches (e.g., multiple findings are “normal”), a greedy process was used to assign each label to a token, iterating through each label and assigning the first matched token to that label if the token wasn't already assigned to another label. This assumes that reporting of eye exam measurements starts with the right side. Labels were constructed in the Inside-Outside-Beginning (IOB2) format,[11,12] with 'O' for no label or outside of the entity, 'B-label' for the beginning of an entity, and 'I-label' for tokens that continue (or are inside of) an entity. The result of this process is a list of tokens and a list of corresponding SLE or FE labels. Data were split into 80:10:10 train, validation, and test sets (N=31279, 3910, 3910 respectively). Full notes were split into shorter subdocuments for input into models which have specified maximum input lengths. BERT word piece tokenization was performed to further decompose tokens into word pieces. Original full word token-level labels were "propagated" as appropriate to each word piece token: "O" labels were assigned to each word piece within a word labeled with "O", and "I" labels were assigned to each word piece within a word labeled "I" or for sequential word piece tokens within words originally labeled "B". Padding and truncation were used to standardize the length of each subdocument for input into models.

Figure 2. Preprocessing pipeline for clinical progress notes and corresponding SmartForm entity labels.

An example progress note and its corresponding SmartForm documentation is shown, as well as the process by which SmartForm labeled entities are assigned to individual words in the progress note. Notes with individual words labeled as entities are tokenized, split into shorter subdocuments, and word piece tokenized as appropriate for input into each Bert model. Label Name: entity label describing a portion of the eye examination. Measurement: The measurement associated with an examination component. Token: A single element of text for computational processing. Labels: entity labels assigned to each token for computational processing. sleodll = slit lamp exam, right eye, lids and lashes; sleosll = slit lamp exam, left eye, lids and lashes; sleodcs = slit lamp exam, right eye, conjunctiva and sclera; sleoscs = slit lamp exam, left eye, conjunctiva and sclera.

Baseline Classifier

The baseline NER model uses regular expressions (regex) to search for anatomical “header” keywords within the text and basic text processing to assign text sandwiched between keywords to the eye exam component indicated by the earlier keyword. See Supplemental Table 2 for summary of overall approach and specific regular expressions used.

BERT Modeling and Experimental Details

All pre-trained models were initialized through the huggingface transformers library[13] for the token classification task, and fine-tuned on our data to identify the different types of eye examination entities. All models were trained with standard cross-entropy loss function for token classification, with the Adam optimizer (learning rate 5e-5, weight decay of 0.01) and warmup steps of 500. Validation loss was calculated after each epoch, and early stopping was used with patience of 3. The model with the best validation loss was used for final evaluation. Each model had varying maximum allowable input lengths, and the batch size was varied to fit the model on GPU (NVIDIA Tesla P100) for training, as summarized in Supplemental Table 3.

Standard Evaluation Metrics

We evaluated the performance of our NER system using the Python seqeval package (v1.2.2)[14]. We report standard metrics for NER tasks: precision, recall, and F1 score for each named entity type as well as micro-averaged metrics across all entities.[15]

Error Analysis and Qualitative Evaluation Metrics

We further analyzed the performance of each model and the baseline classifier on a sample of 100 manually annotated documents from the test set, using the Prodigy annotation tool (https://prodi.gy/) to visualize and correct our models' predictions. We also manually corrected and analyzed samples of the models' training labels as well, given that these were assigned algorithmically rather than by a human and could contain noise. On the annotated sample of documents, we report the standard evaluation metrics of each model (and its training labels) to the ground truth human annotation. We also give qualitative examples of typical contexts in which the models fail.

We also identified an independent set of clinical progress notes (“outset”) in which providers directly typed their eye exam findings into free text rather than into SmartForms. The format of these free text exam findings was more variable and more customized to individual providers. Of the 84,292 notes in the “outset”, we randomly sampled 100 to investigate in detail. We divided these notes into shorter subdocuments and input them into the BlueBert model, then manually reviewed the BlueBert model predictions in Prodigy to identify strengths and weaknesses of this model on an independent set of fully free text notes.

Model Demonstration

We have built a demonstration for all models which is available online (http://flasknerapp.herokuapp.com/). Users can input any text and choose a model to identify the words that form the ophthalmic exam.

RESULTS

Model Performance Against Training Labels

Performance of the models against the weakly supervised SmartForm-based training labels in the test set is summarized in Table 1. All BERT models had excellent recall, micro-averaging over 0.92. Precision varied, ranging from a high of 0.85 micro-averaged for DistilBert to a low of 0.44 micro-averaged for BlueBert. The baseline model had lower recall (0.77) than the BERT models, though comparable and sometimes higher precision (0.68).

Table 1.

Model Performance Against Weakly Supervised Labels in Test Set

| Component | Baseline Model | DistilBert | BioBert | BlueBert | ClinicalBert | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | ||

| SLE, Right | L/L | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.5 | 0.99 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 0.8 |

| C/S | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.99 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.78 | |

| K | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.99 | 0.8 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.98 | 0.68 | |

| AC | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.7 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.47 | 0.99 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.54 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Iris | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.9 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 0.8 | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.99 | 0.71 | |

| Lens | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.9 | 0.73 | 0.5 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.98 | 0.7 | |

| AV | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.5 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.98 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 0.79 | |

| FE, Right | Disc | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.9 | 0.75 | 0.4 | 0.95 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.6 | 0.48 | 0.95 | 0.64 |

| CDR | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.96 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.9 | 0.76 | |

| M | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.88 | 0.54 | |

| V | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.51 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.89 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.88 | 0.69 | |

| P | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 0.88 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.85 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.83 | 0.44 | |

| SLE, Left | L/L | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.7 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 0.7 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 0.8 | 0.69 | 0.99 | 0.82 |

| C/S | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 0.8 | 0.51 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.43 | 0.99 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.77 | |

| K | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.78 | 0.6 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.98 | 0.68 | |

| AC | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.9 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.5 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.98 | 0.7 | |

| Iris | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.9 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.99 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.79 | |

| Lens | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.61 | 0.9 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.98 | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 0.7 | |

| AV | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.99 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.84 | |

| FE, Left | Disc | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.88 | 0.7 | 0.39 | 0.94 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.94 | 0.68 |

| CDR | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.79 | |

| M | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.9 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.9 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.89 | 0.56 | |

| V | 0.7 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 0.5 | 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.74 | |

| P | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.4 | 0.53 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.84 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.85 | 0.48 | |

| Micro avg | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.96 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.95 | 0.69 | |

Pr = precision, Rec = recall, L/L = lids and lashes, C/S = conjunctiva and sclera, K = cornea, AC = anterior chamber, AV = anterior vitreous, Disc = optic disc, CDR = cup to disc ratio, M = macula, V = vessels, P = periphery.

Common Sources of Training Label Errors

During the human annotation of the training labels, common sources of errors were noted in the algorithmic weak label-assignment. Performance metrics of the labeling algorithm compared to human-annotated ground truth on a sample of 100 notes is presented in Supplemental Table 4. The overall micro-averaged F1 score of training labels when evaluated against human annotations was high (0.96). Examples of common types of errors are illustrated in Supplemental Figure 1 and include instances where some exam components are not labeled or partially missed and where text outside of the eye exam is mislabeled as an eye exam finding.

Model Performance Against Human-Annotated Ground Truth

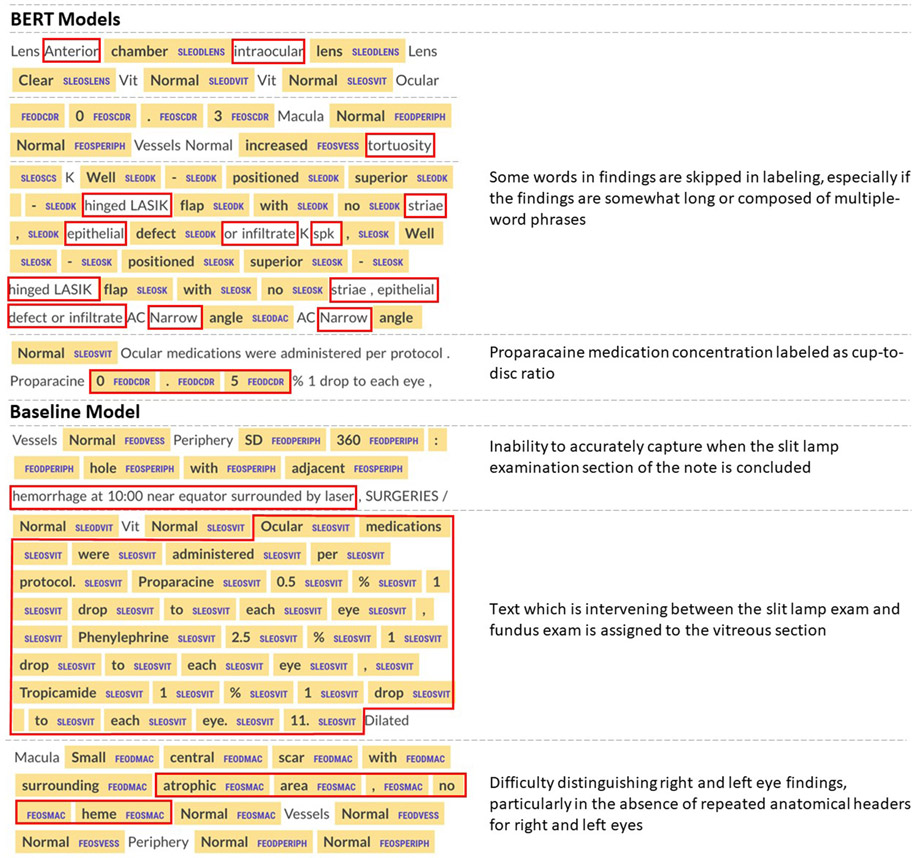

Given the existence of some noise in the training labels, we manually annotated a sample of 100 notes from the test set for the true entity labels. BERT and baseline model predictions were compared against this human-annotated ground truth to evaluate the true performance of the models (Table 2). The baseline model had high recall (0.96 micro-averaged) but precision was variable, ranging from 0.11 to 1 depending on specific entity, for an overall micro-averaged precision of 0.57. BERT models had uniformly better performance, with micro-averaged F1-score ranging from 0.86 (DistilBert) to 0.9 (BlueBert), micro-averaged recall ranging from 0.77 (DistilBert) to 0.84 (BlueBert), and micro-averaged precision ranging from 0.95 (ClinicalBert) to 0.98 (BioBert). Thus, for BERT models, precision was higher than recall when evaluated against human-annotated ground truth data, while recall was higher than precision when tested on algorithmically-labeled data. Examples of common model errors are given in Figure 3. Most errors occur when contiguous words that comprise a finding are not all labeled, with some words “skipped” in labeling.

Table 2.

Model Performance Against Human-Annotated Ground Truth in Test Set

| Component | Baseline Model | DistilBert | BioBert | BlueBert | ClinicalBert | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | Pr | Rec | F1 | ||

| SLE, Right | L/L | 0.78 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.8 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| C/S | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.96 | |

| K | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 1 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.74 | 0.83 | |

| AC | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | |

| Iris | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.96 | |

| Lens | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.98 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.86 | |

| AV | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.69 | 0.81 | |

| FE, Right | Disc | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.82 |

| CDR | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.95 | |

| M | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 0.73 | |

| V | 0.33 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.83 | |

| P | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 0.84 | |

| SLE, Left | L/L | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.88 |

| C/S | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 | |

| K | 0.7 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 1 | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.8 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.75 | |

| AC | 0.4 | 0.99 | 0.57 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| Iris | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.96 | |

| Lens | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.73 | 0.82 | |

| AV | 0.11 | 0.95 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.81 | |

| FE, Left | Disc | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.8 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.82 |

| CDR | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.5 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.95 | |

| M | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.7 | |

| V | 0.32 | 0.95 | 0.48 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.84 | |

| P | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.8 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.82 | |

| Micro avg | 0.57 | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.97 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.8 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.84 | 0.9 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.88 | |

Pr = precision, Rec = recall, L/L = lids and lashes, C/S = conjunctiva and sclera, K = cornea, AC = anterior chamber, AV = anterior vitreous, Disc = optic disc, CDR = cup to disc ratio, M = macula, V = vessels, P = periphery.

Figure 3. Examples of Common Types of BERT and Baseline Model Prediction Error.

Examples of common model mistakes on the text from the test set are given in the left column, along with corresponding explanations to the right. Areas highlighted in yellow show the model prediction. Areas boxed in red are those areas where the model has made a mistake, either in the prediction label or in failure to recognize any entity.

Evaluation Against Independent Fully Free-Text Clinical Notes

To evaluate whether a model trained on SmartForm-labeled notes could potentially generalize to completely free-text progress notes, we chose to evaluate the baseline model and the highest-performing BERT model (BlueBert) on an independent set of 100 progress notes which document the eye examination in free-text. This approach is possible at our center because many ophthalmologists prefer not to use SmartForm-driven templates to document their eye exam; thus, their notes are examples of completely free-text ophthalmology notes. Results are summarized in Table 3. Broadly, the BlueBert model had very good precision (micro-average 0.93) but relatively poor recall (0.39), whereas the baseline model had better recall (0.72) but poor precision (0.44).

Table 3.

Model Performance on Independent Set of Free-Text Progress Notes

| Component | Baseline Model | BlueBert Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1 | Precision | Recall | F1 | ||

| SLE, Right | Lids and Lashes | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.7 | 0.91 | 0.41 | 0.57 |

| Conjunctiva/Sclera | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.5 | 0.66 | |

| Cornea | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.37 | 0.5 | |

| Anterior Chamber | 0.9 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.8 | |

| Iris | 0.85 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.31 | 0.47 | |

| Lens | 0.29 | 0.78 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.52 | |

| Anterior Vitreous | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| FE, Right | Optic Nerve | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Cup To Disc Ratio | 0.49 | 0.6 | 0.54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Macula | 0.86 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.46 | |

| Vessels | 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.71 | |

| Periphery | 0.87 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.39 | 0.56 | |

| SLE, Left | Lids and Lashes | 0.51 | 0.8 | 0.62 | 0.87 | 0.39 | 0.54 |

| Conjunctiva/Sclera | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 0.7 | |

| Cornea | 0.51 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.38 | 0.52 | |

| Anterior Chamber | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 0.77 | |

| Iris | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.27 | 0.42 | |

| Lens | 0.29 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.4 | 0.55 | |

| Anterior Vitreous | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| FE, Left | Optic Nerve | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cup To Disc Ratio | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Macula | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.96 | 0.32 | 0.49 | |

| Vessels | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.7 | |

| Periphery | 0.2 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.96 | 0.45 | 0.61 | |

| Micro average | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.39 | 0.55 | |

DISCUSSION

We were able to leverage EHR data captured from routine ophthalmic care to train deep learning NER models in a semi-supervised manner to detect with high precision findings from the anterior and posterior segment exams and their lateralities embedded within ophthalmology clinical progress notes. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to train a deep learning model to recognize eye examination components from clinical progress notes.

The level of performance we observed for recognition of ophthalmic exam components is within the expected range based on previous reports of BioBert’s performance on biomedical NER tasks,[2] and all BERT models outperformed the baseline regex model. Hand-crafted regular expressions can be an effective and computationally inexpensive means of recognizing specific text sequences. However, because note templates vary greatly from doctor to doctor, it is unfeasible to build regular expressions that capture all patterns. The baseline model’s approach to assigning entities is inflexible and only works reliably for notes that document exam findings in a consistent order with all heading keywords present. Regex models also struggled to distinguish right from left eye findings when these findings were often contiguous without obvious syntactical signals indicating the end of the right eye finding and the beginning of the left eye finding. On the other hand, transformer models can learn to label entities more flexibly. Although the original training labels were noisy and imperfect, our results suggest that BERT models trained using this weak supervision approach can ignore some noise present in training labels to achieve better performance against the human-annotated labels. The baseline model also frequently fails when assigning entities to the final heading of any exam section, as there is no reliable syntactical way to identify the end of the last finding. This limitation exists even when note-taking styles are consistent, thus rendering transformer models favorable to the regex model in multiple ways.

A unique aspect of our study is evaluating performance on an independent set of notes not generated in the same manner as the original training and test sets, simulating how ophthalmic notes might appear at other sites or systems. In this setting, our model maintained excellent precision in many categories, with lower recall. The baseline model had the opposite pattern of performance, with generally preserved recall and worse precision. The transformer model thus misses many entities, likely when they occur in contexts different from in the training set, whereas the baseline model over-identifies words belonging to entities, which may happen when the patterns for the context cues (headers) are missing or different and the regex is allowed to match long sequences of irrelevant text. Further work to improve performance may attempt to combine both types of models to optimize both precision and recall, or to gather larger training datasets from a greater variety of institutions and providers.

The ability to start with a relatively large training corpus without any manual annotation is the main strength of the weak supervision approach. Rather than manually annotating 24 different eye examination entities across thousands of notes, which would be laborious and time-consuming, we algorithmically produced nearly 40,000 relatively cleanly labeled notes. Although crowdsourcing can be a way to generate large annotated corpora for training purposes,[16-18] unlike in image labeling where images may be relatively easily de-identified, clinical text would be much more difficult to reliably de-identify to the point where release to crowdsourcing workers would be safe. Medical text is also full of abbreviations and would require significant training of crowdsourced workers to interpret.

Our work performing NER for the ophthalmic exam may have broad potential applications. Researchers in other specialties may also wish to utilize a similar weakly supervised approach to build their own specialized NER systems for clinical notes, for example to automatically recognize relevant clinical measures of polyps from colonoscopy reports, tumors from pathology reports, etc. Reconstruction of tabular structure from unstructured text is another general challenge for which this approach may be used. The granular characterization of patients’ clinical characteristics can enable cohort construction for observational research as well as for clinical trials, which is often complex with many specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.[19] In ophthalmology, we would be able to identify cohorts with specific ophthalmic features not commonly documented in structured billing codes, such as disc hemorrhages for glaucoma patients, geographic atrophy for macular degeneration patients, or the signs of previous eye surgery or laser. Similarly, researchers building predictive models for ophthalmic or other clinical outcomes may wish to use an NER system to construct meaningful input features for predictive models which can improve their performance and explainability. Many EHR systems besides Epic are entirely free-text, such as in the Veterans’ Health Administration. To understand any eye examination components from such systems on a large scale, our NER model can be fine-tuned to suit those ophthalmology notes, and it may require manually annotating fewer notes than training de novo without weak supervision.

Several challenges and limitations remain. The loss of tabular formatting in the notes makes it difficult even for human graders to understand the measurements and their types, so perhaps it is unsurprising that the models may find it difficult. There is great variation in how the eye exam findings are documented: for example, sometimes with all right eye findings reported and then all left eye findings, and sometimes alternating right and left. These models are also not designed to handle cases where the provider documents bilateral findings, such as “normal OU.” Furthermore, notes must be split up into shorter segments because of model input length limitations. Because the sections documenting eye examination components are not really "sentences", notes could be split in awkward locations, cutting off the context of the findings. Finally, the models trained on weakly labeled data sometimes replicated the mistakes present in training labels.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have developed, to our knowledge, the first deep learning pipeline to recognize eye examination components from clinical progress notes. Our system leverages a weakly supervised labeling system to produce nearly 40,000 relatively cleanly labeled notes to train BERT-based models. The models trained in this manner performed better on a set of manually labeled notes than on the algorithmically labeled notes, while a baseline model based on regular expressions held near identical performance across the two sets. This suggests the BERT-based models were able to learn entity recognition patterns beyond the small noise present in the training set. Our work holds many potential applications to ophthalmology research, from precise cohort design to feature engineering for predictive model development. This weak supervision approach leveraging routinely collected EHR data may also be generalized to other specialties seeking to train models to recognize specific entities from free-text notes.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY TABLE.

| What is known? | What does this add? |

|---|---|

|

|

FUNDING SOURCES

Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (SYW); National Institutes of Health National Eye Institute 1K23EY03263501 (SYW); Research to Prevent Blindness unrestricted departmental funds (SYW; WH); National Eye Institutes P30-EY026877 (SYW; WH)

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the use of clinical notes in the study, which include many protected health identifiers containing patient information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, et al. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2017.http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020;36:1234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang K, Altosaar J, Ranganath R. ClinicalBERT: Modeling Clinical Notes and Predicting Hospital Readmission. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2019.http://arxiv.org/abs/1904.05342 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alsentzer E, Murphy JR, Boag W, et al. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2019.http://arxiv.org/abs/1904.03323 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng Y, Yan S, Lu Z. Transfer Learning in Biomedical Natural Language Processing: An Evaluation of BERT and ELMo on Ten Benchmarking Datasets. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2019.http://arxiv.org/abs/1906.05474 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanh V, Debut L, Chaumond J, et al. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2019.http://arxiv.org/abs/1910.01108 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abadeer M Assessment of DistilBERT performance on Named Entity Recognition task for the detection of Protected Health Information and medical concepts. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop. Online: : Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. 158–67. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baughman DM, Su GL, Tsui I, et al. Validation of the Total Visual Acuity Extraction Algorithm (TOVA) for Automated Extraction of Visual Acuity Data From Free Text, Unstructured Clinical Records. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2017;6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe HJ, Ferris TA, Hernandez PM, et al. STRIDE--An integrated standards-based translational research informatics platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2009;2009:391–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.nltk. Github; https://github.com/nltk/nltk (accessed 2 Jun 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wikipedia contributors. Inside–outside–beginning (tagging). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2020.https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Inside%E2%80%93outside%E2%80%93beginning_(tagging)&oldid=958799045 (accessed 1 Mar 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramshaw LA, Marcus MP. Text Chunking using Transformation-Based Learning. arXiv [cmp-lg]. 1995.http://arxiv.org/abs/cmp-lg/9505040 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf T, Debut L, Sanh V, et al. HuggingFace’s Transformers: State-of-the-art Natural Language Processing. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2019.http://arxiv.org/abs/1910.03771 [Google Scholar]

- 14.seqeval. Github; http://github.com/chakki-works/seqeval (accessed 1 Mar 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterbak T Named entity recognition with Bert. Depends on the definition. 2018.https://www.depends-on-the-definition.com/named-entity-recognition-with-bert/ (accessed 1 Mar 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitry D, Peto T, Hayat S, et al. Crowdsourcing as a screening tool to detect clinical features of glaucomatous optic neuropathy from digital photography. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Mudie LI, Baskaran M, et al. Crowdsourcing to Evaluate Fundus Photographs for the Presence of Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2017;26:505–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Mudie L, Brady CJ. Crowdsourcing: an overview and applications to ophthalmology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2016;27:256–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez-Boussard T, Monda KL, Crespo BC, et al. Real world evidence in cardiovascular medicine: ensuring data validity in electronic health record-based studies. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019;26:1189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.