Abstract

Diaphragmatic hernias can be congenital or acquired and are a protrusion of intra-abdominal contents through an abnormal opening in the diaphragm. Acquired defects are rare and occur secondary to direct penetrating injury or blunt abdominal trauma. This case review demonstrates two unconventional cases of large diaphragmatic hernias with viscero-abdominal disproportion in adults. Case 1 is a 27-year-old man with no prior medical or surgical history. He presented following a 24-h history of increasing shortness of breath and left-sided pleuritic chest pain, and no history of trauma. Chest X-ray demonstrated loops of bowel within the left hemithorax with displacement of the mediastinum to the right. Computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a large diaphragmatic defect causing herniation of most of his abdominal contents into the left hemithorax. He underwent emergency surgery, which confirmed the viscero-abdominal disproportion. He required an extended right hemicolectomy to reduce the volume of the abdominal comtents and laparostomy to reduce the risk of abdominal compartment syndrome and recurrence of the hernia. Case 2 is a 76-year-old man with significant medical comorbidities who presented with acute onset of abdominal pain. He had a history of traumatic right-sided chest injury as a child resulting in right-sided diaphragmatic paralysis. Chest X-ray demonstrated a large right-sided diaphragmatic hernia with abdominal viscera in the right thoracic cavity. CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated both small and large bowel loops within the right hemithorax, compression of the right lung and displacement of the mediastinum to the left. The CT scan also demonstarted viscero-abdominal disproportion. Operative management was considered initially but following improvement with basic medical management and no further deterioration, a non-operative approach was adopted. Both cases illustrate atypical presentations of adults with diaphragmatic hernias. In an ideal scenario, these are repaired surgically. When the presumed diagnosis shows characteristics of a viscero-abdominal disproportion and surgery is pursued, the surgeon must consider that primary abdominal closure may not be possible and multiple operations may be necessary to correct the defect and achieve closure. Sacrifice of abdominal viscera may also be necessary to reduce the volume of abdominal contents.

Keywords: Diaphragmatic hernia, Blunt and penetrating trauma, Open and minimal access repair, Congenital diaphragmatic hernia, Abdominal compartment syndrome, Delayed closure, Viscero-abdominal disproportion

Background

A diaphragmatic hernia is a protrusion of the intra-abdominal contents through an abnormal opening in the diaphragm. Diaphragmatic hernias can be congenital or acquired.

One in 500 new-born babies have a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH).1 This results from incomplete formation of the diaphragm during embryogenesis. A diaphragmatic hernia can occur at the oesophageal hiatus (sliding and para-oesophageal hiatal hernias), in the posterolateral region (Bochdalek’s hernia) or in the parasternal region (Morgagni–Larrey). Morgagni’s hernia often refers to those occurring on the right, whereas Larrey’s hernia refers to those on the left.2

Acquired diaphragmatic hernias are rare with an incidence of <5%. They are usually secondary to a direct penetrating injury (65% of cases), such as a gunshot or a stab injury, or blunt abdominal trauma (35%) such as road traffic accidents or falls.3

Here, we present two unconventional cases of large diaphragmatic hernias presenting in adulthood. Both cases are unique with characteristics of congenital origin (viscero-abdominal disproportion). We discuss the rationale for treating the individuals based on the clinical picture (symptoms, comorbidities, prolonged recovery, length of hospital stay, likelihood of re-operation).

Case history

Case 1

The first case is that of a 27-year-old man with no previous medical or surgical history, and no history of trauma. He presented with a 24-h history of increasing shortness of breath associated with left-sided pleuritic subcostal chest pain that was sharp in nature and non-radiating. On review of his history, the patient reported a 2-year history of mild epigastric pain without vomiting or changes in his bowel habits. In addition, he reported a weight gain of 20kg over the past 2 years and a 1-year history of dyspnoea. The patient denied recent trauma. Of note, the patient was referred for an ultrasound scan of his abdomen 5 years prior to this admission to investigate derangement in liver function tests. The report at that time noted that the left flank was difficult to visualise due to bowel gas and that the spleen could not be seen; however, no further investigations were undertaken.

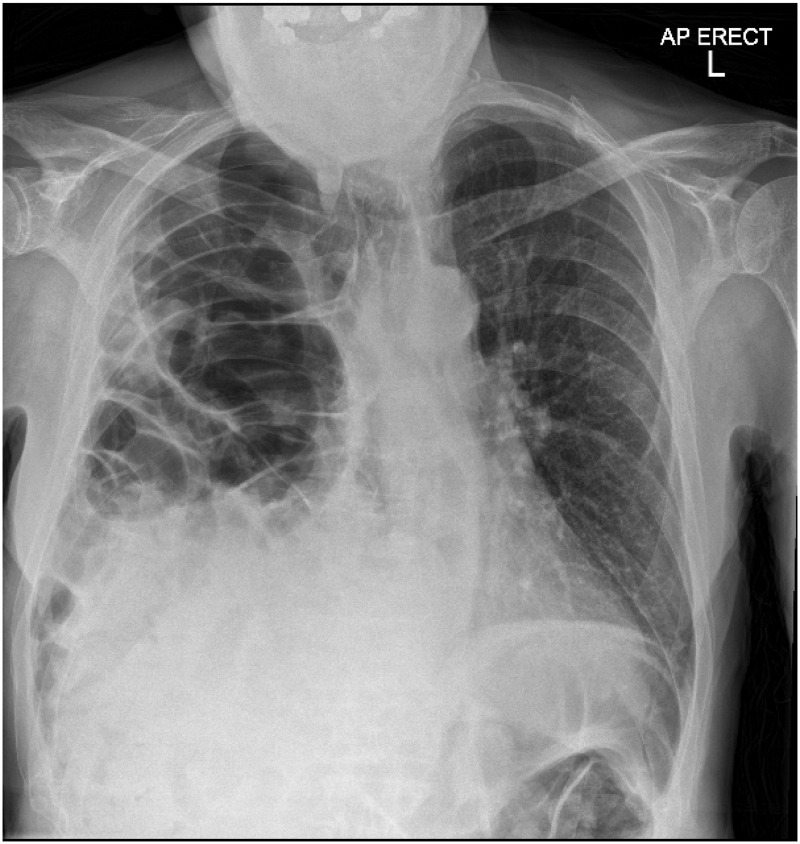

Admission chest X-ray demonstrated loops of bowel within the left hemithorax with displacement of the mediastinum to the right (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Admission chest X-ray demonstrating loops of bowel within the left hemithorax and mediastinal shift to the right

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis confirmed a large 104mm left-sided posterior diaphragmatic defect causing the majority of his abdominal contents to herniate into the left hemithorax with complete collapse of the left lung and mediastinal shift to the right (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

Computed tomography scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis with contrast demonstrating a large left-sided posterior diaphragmatic defect causing abdominal content to herniate into the left hemithorax with complete collapse of the left lung

The abdominal and pelvic space appeared very small in volume (viscero-abdominal disproportion), raising the suspicion of a congenital hernia.

The patient was counselled and had a detailed discussion regarding the difficulties in attempting repair of his hernia. This conversation included discussions that the abdomen would be unable to accommodate the reduced contents. Significant risks such as intraabdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) necessitating a laparostomy and early recurrence were discussed. The primary aim was to displace the herniated abdominal viscera from the left hemithorax, which was causing the mediastinal shift and respiratory compromise, and to repair the diaphragmatic defect.

An emergency laparotomy with a rooftop incision was performed. The herniated viscera could not be reduced safely owing to adhesions in the thorax. Access to the left thoracic cavity was achieved by a left thoraco-abdominal extension of the laparotomy through the left seventh intercostal space. This enabled division of the mediastinal, lung and chest wall adhesions. These adhesions confirmed our hypothesis that this man had probably lived into adulthood with a CDH.

The left thoraco-abdominal access also enabled mesh reinforcement of the large posterior diaphragmatic defect from the thoracic side. A hybrid Parietex™ Optimized Composite (Medtronic) mesh was used to cover the defect with the resorbable collagen barrier side placed on the diaphragm facing the abdominal cavity. The mesh was sutured in place with a double layer of non-absorbable interrupted Prolene sutures.

The posterolateral segment of the left diaphragm looked weak. The decision was therefore made to reinforce the left hemidiaphragm. This was achieved with a large Permacol™ surgical implant (Medtronic), which is a porcine dermal acellular collagen implant (cross-linked acellular collagen matrix) mesh. The Permacol™ mesh was placed over the diaphragm and the Parietex™ mesh on the thoracic side. The mesh was fixed posterolaterally along the origins of the diaphragm starting along the psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles, and extended laterally to the seventh to ninth ribs. The medial and anterior sides were easier to fix to the diaphragm. Interrupted Prolene nonabsorbable sutures were used throughout.

The reduced contents into the abdominal cavity did not allow safe closure of the incision. The right side of the rooftop laparotomy was therefore left open as a laparostomy with some of the greater curve of the stomach, all of the spleen and majority of the colon lying outside the abdominal cavity.

A planned relook was undertaken a few days later at which time the grossly dilated colon and small bowel loops could not be managed by the left-sided transverse laparostomy. The rooftop abdominal opening was therefore extended to a midline laparotomy. Despite the midline laparotomy, the grossly distended colon could not be controlled to create a laparostomy. Review with specialist hernia and colorectal surgeons was undertaken and sacrifice of the colon was considered as the option to allow creation of a manageable laparostomy. An extended right hemicolectomy or subtotal colectomy with splenectomy were considered as possible options to debulk the abdominal contents. An extended right hemicolectomy with a stapled side-to-side ileocolonic anastomosis was adequate to create a manageable laparostomy. The laparostomy was managed using a negative pressure laparostomy management kit.

The patient had a prolonged hospital recovery and was discharged 71 days after admission with planned follow-up at routine intervals on an outpatient basis to monitor healing of the laparostomy by secondary intention. The patient is clinically well with no recurrence 1 year after surgery.

Case 2

A 76-year-old man presented to accident and emergency with an acute onset of abdominal pain associated with nausea and diarrhoea. Three days prior to the onset of pain, the patient had a fall that resulted in extensive bruising to his lower back. The patient’s background medical history included hypertension, asthma, hypothyroidism and severe Parkinson’s disease, and a history of a traumatic right-sided diaphragmatic paralysis secondary to a crush injury to the chest 60 years prior.

Initial observations in the emergency department demonstrated a tachycardia of 102 and a tachypnoea of 31 breaths per minute. However, oxygen saturations were within normal limits. Chest examination demonstrated decreased air entry in the right hemithorax (Figure 3).

Figure 3 .

Chest X-ray, August 2020, showing marked elevation of the right hemidiaphragm

Chest X-ray demonstrated the presence of abdominal viscera within the right thoracic cavity that was felt to be a significant progression from the previous chest X-ray performed 7 months prior to the current admission (Figure 4).

Figure 4 .

Admission chest X-ray, January 2021, demonstrating loops of bowel within the right hemithorax and mediastinal shift to the left

An urgent CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated both small and large bowel loops within the right hemithorax, compression of the right lung and displacement of the mediastinum to the left (Figure 5).

Figure 5 .

Computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrating both small and large bowel loops within the right hemithorax, compression of the right lung and displacement of the mediastinum to the left

The CT also confirmed a small portion of intact diaphragm posteriorly and an intact right crus, but the central and anterior portions of the right diaphragm were not appreciable.

Operative management was considered in the first instance. However, his symptoms improved with conservative medical management consisting of intravenous fluids and parenteral nutrition. These factors, combined with the high anticipated risk of operative complications including need for laparostomy, prolonged critical care and mortality, made the team persevere with non-operative management. The patient continued to improve clinically and was successfully discharged home 12 days following admission. He returned to normal physical activity 3 months post discharge. He has continued to improve at home and at a review 9 months after the admission, was managing walks of up to 3 miles and had been managing to play a set of tennis regularly.

Discussion

These two cases demonstrate atypical presentations of adults with diaphragmatic hernias. Although both cases are unique in their own respects, they do share similarities. They both constitute an ‘acute on chronic’ picture rather than the typical presentation of an acquired diaphragmatic hernia in the adult population. For this reason, management of these particular individuals did not comply with traditionally described treatment algorithms.

There is no consensus on the absolute indications for surgery or the timing of surgical intervention in the literature. A traumatic rupture of the diaphragm is generally considered an indication for surgical repair. Primary suture repair or bridging the defect with a synthetic mesh has been the standard of care during past decades. Biological meshes are considered to be effective in closing the diaphragmatic defect with a limited inflammatory response, and minimising adhesion formation.4

In an ideal scenario, CDH repair (when approached using a laparotomy) should achieve primary abdominal closure. However, this can be associated with a high risk of developing ACS.5,6 This is a direct result of viscero-abdominal disproportion or loss of right of domain. In the cases presented, achieving primary abdominal closure would not have been possible because this would be associated with the risks of ACS. To avoid this complication, a delayed abdominal closure is advised.7

Case 1 demonstrates a young individual with what would be considered as a CDH presenting beyond childhood. He presented in adulthood with no prior symptoms that would warrant any concern or suspicion of this diagnosis. A definite viscero-abdominal disproportion and presence of mediastinal and thoracic adhesions intraoperatively confirmed the preoperative suspicions of CDH. Abdominal closure was not possible and ultimately resulted in sacrifice of abdominal viscera to enable delayed healing by secondary intention and a resultant abdominal hernia.

By comparison, Case 2 demonstrates an individual who had a history of reduced space in his right thoracic cavity due to paralysis of his right hemidiaphragm. Despite loss of the remaining lung capacity on the right side he was able to tolerate the additional reduction in lung volume (despite being acutely unwell and his medical comorbidities). We believe this is a unique case of non-operative management of a large acute or acute on chronic diaphragmatic hernia and have not found any other case in the literature.

Conservative management of large asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic hiatal hernias is well established but there is no literature on non-hiatal diaphragmatic hernias being managed non-operatively. As such, this case report may represent the first example of non-operative management being used in practice for this subtype of diaphragmatic hernias.

Conclusions

Adults may present with acute on chronic exacerbation of diaphragmatic hernia with minimal or no trauma. The surgeon must be aware of and identify the viscero-abdominal disproportion on the CT scans, which will help plan complex treatment options. This may include a planned laparostomy, prolonged hospital stay with multiple surgeries and sacrifice of abdominal viscera, as in the first case. Staged complex abdominal wall reconstruction may need to be considered. In addition, the patient will endure a prolonged course of recovery and rehabilitation, which may not be suitable or deemed survivable for individuals who are in the older demographic with multiple comorbidities such as the man described in the second case.

References

- 1.Testini M, Giraldi A, Iseria RMet al. Emergency surgery due to diaphragmatic hernia: A case series and review. World J Emerg Surg 2017; 12: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arikan S, Dogan MB, Kocakusak Aet al. Morgagni’s hernia: analysis of 21 patients with our clinical experience in diagnosis and treatment. Indian J Surg 2018; 80: 239–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amboss. Acquired Diaphragmatic Hernias. http://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/Acquired_diaphragmatic_hernias/ (cited April 2023).

- 4.Antoniou S, Pointner R, Granderath Fet al. The use of biological meshes in diaphragmatic defects – An evidence-based review of the literature. Front Surg 2015; 2: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell D, Baird R, Puligandla P. Abdominal wall closure in neonates after congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48: 930–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki T, Okamoto T, Hanyu Ket al. Repair of Bochdalek hernia in an adult complicated by abdominal compartment syndrome, gastropleural fistula and pleural empyema: report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5: 82–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Costa K, Saxena A. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair analysis in relation to postoperative abdominal compartment syndrome and delayed abdominal closure. Updates Surg 2021; 73: 2059–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]