Abstract

Aptamers composed of mirror-image L-(deoxy)ribose nucleic acids, referred to as L-aptamers, are a promising class of RNA-binding reagents. Yet, the selectivity of cross-chiral interactions between L-aptamers and their RNA targets remain poorly characterized, limiting the potential utility of this approach for applications in biological systems. Herein, we carried out the first comprehensive analysis of cross-chiral L-aptamer selectivity using a newly developed “inverse” in vitro selection approach that exploits the genetic nature of the D-RNA ligand. By employing a library of more than a million target-derived sequences, we determined the RNA sequence and structural preference of a model L-aptamer and revealed previously unidentified and potentially broad off-target RNA binding behaviours. These results provide valuable information for assessing the likelihood and consequences of potential off-target interactions and reveal strategies to mitigate these effects. Thus, inverse in vitro selection provides several opportunities to advance L-aptamer technology.

Keywords: L-aptamer, selectivity, in vitro selection, sequencing, RNA

Graphical Abstract

L-aptamers, those made of L-(deoxy)ribose nucleic acids, are a promising class of RNA affinity reagent, but their selectivity remains poorly characterized. Herein, we developed an “inverse’ in vitro selection method that enables comprehensive analysis of L-aptamer selectivity and revealed promiscuous RNA-binding behaviors for a model L-aptamer.

Introduction

As with other biomolecules, the function of RNA is closely related to its structure.[1] Base-pairing properties enable RNA to fold into intricate three-dimensional architectures derived from secondary structural elements, such as hairpins, bulges, and pseudoknots, which minimize the overall free energy of the molecule. RNA structural motifs can influence the transcription, splicing, cellular localization, stability, and translation of the RNA.[2] Thus, RNA structure plays a role in almost every facet of gene expression. Furthermore, structured RNA elements have been discovered to play critical roles in various diseases, including viral infections and cancer.[3]

Given the importance of RNA structure in biology and disease, development of structure-specific RNA-binding reagents has been the focus of intense research activity in recent years.[4] Several classes of RNA structure-specific reagents have been developed, including, small molecules, peptides, and engineered proteins.[4c, 5] One promising class of RNA-binding reagents are aptamers composed of mirror-image L-(deoxy)ribose nucleic acids (i.e., L-aptamers or Spieglemers).[6] Although D- and L-oligonucleotides have identical physical and chemical properties, they are incapable of forming contiguous Watson-Crick (WC) base pairs with each other.[7] This encourages recognition between D- and L-oligonucleotides to occur independent of primary sequence. This property is exploited during the process of in vitro selection in order to evolve L-aptamers that adaptively bind structured D-RNA targets through tertiary interactions (or shape) rather than sequence complementarity. Our group[8] and others[9] have shown that this unique “cross-chiral” mode of recognition occurs with low nanomolar affinity. These properties, coupled with the intrinsic nuclease resistance of L-oligonucleotides[10], provide L-aptamers a broad range of opportunities as RNA-targeted reagents.[11]

An important consideration for any class of RNA-binding reagent is selectivity, which remains a central challenge in the field.[4c] For example, the limited chemical diversity of RNA relative to proteins, along with its dynamic structures and negatively charged backbone, continue to hinder development of highly selective small-molecule ligands.[12] Moreover, all classes of RNA-binding reagents must overcome the difficulty of binding RNA specifically in a cellular environment wherein the majority of RNA is ribosomal. The dearth of RNA-targeted therapeutics relative to those targeting proteins highlights the challenge of selective RNA binding. From a selectivity standpoint, L-aptamers have several potential advantages compared to other RNA-targeted approaches. For example, selectivity can be rigorously enforced during the in vitro selection process by employing counter selection steps against structurally similar RNA targets. Indeed, L-aptamers have been shown to differentiate their intended D-RNA targets from those containing single-nucleotide mutations or minor structural perturbations.[8] Nevertheless, apart from these limited studies, the selectivity of L-aptamers for their structured RNA targets have not been comprehensively evaluated, representing a key gap in our understanding of this potentially powerful class of RNA-targeted reagent. In the current study, we employed a novel in vitro selection method to carry out the first comprehensive analysis of cross-chiral L-aptamer selectivity.

Results and Discussion

A unique feature of cross-chiral recognition is that both the L-aptamer and its D-RNA target are genetic polymers capable of directed evolution. On this basis, we develop an in vitro selection approach that exploits the genetic nature of the D-RNA target in order to carry out a comprehensive analysis of cross chiral aptamer selectivity (Figure 1). In brief, the L-aptamer of interest is immobilized on a solid support and used to enrich potential off-target sequences from a library of target-derived D-RNA molecules. This method, which is akin to the seminal work of Tuerk and Gold,[13] is herein referred to as “inverse” in vitro selection because the target ligand, not the aptamer receptor, is undergoing selective enrichment.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the inverse in vitro selection method and comparison to a standard selection approach. During inverse in vitro selection, the unhybridized loop domain of the RNA target, not the L-aptamer, undergoes selective enrichment to identify potential off-target sequences.

We chose the L-RNA aptamer L-6-4t as the focus of this study (Figure 2).[9b] L-6-4t binds tightly to the trans-activation response element RNA (D-TAR) from HIV-1 (Figure 2). The aptamer binding site on D-TAR is localized to the 6-nucleotide (nt) distal loop. In the initial report[9b], the authors found that L-6-4t was unable to bind a small set of rationally designed D-TAR variants, and thus, concluded that L-6-4t is highly selective for D-TAR. However, realizing the limitations of this small sample size to identify off-target sequences, we aimed to more thoroughly evaluate the selectivity of L-6-4t using our inverse in vitro selection approach.

Figure 2.

Sequences and secondary structures of L-6-4t, D-TAR RNA, and library D-L6N. The boxed nucleotides in D-TAR indicate the L-6-4t binding site and were randomized to generate D-L6N. Sequences of all oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1.

To begin, we chemically synthesized the D-TAR hairpin such that the distal loop domain was completely randomized, resulting in a 4,096-member library of TAR hairpins containing all possible 6-nucleotide loops (D-L6N; Figure 2 and Table S1). An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) indicated that the naïve D-L6N library had no detectable affinity for L-6-4t (Figure S1), even at concentrations of L-6-4t that greatly exceeded its Kd for D-TAR (100 nM). This indicated that very few sequences within L6N were capable of binding L-6-4t.

Library D-L6N was then subjected to the inverse selection scheme outlined in Figure 1 (see Experimental Section). Briefly, D-L6N was mixed with 5′-biotinylated L-6-4t at room temperature in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6). D-RNA hairpins that bound L-6-4t were captured using magnetic streptavidin beads. The beads were washed several times with the same binding solution, and D-RNA hairpins that remained bound then were eluted using NaOH, reverse transcribed, and amplified by PCR. The resulting dsDNAs were used to transcribe a corresponding pool of enriched RNAs to begin the next round of inverse in vitro selection. The affinity of the D-L6N pool for L-6-4t gradually increased during successive round of in vitro selection (Figure S1). After the third round, the enriched D-L6N library bound L-6-4t about as well as D-TAR. Thus, the selection was stopped at this point and the enriched library was cloned and sequenced (Table S2).

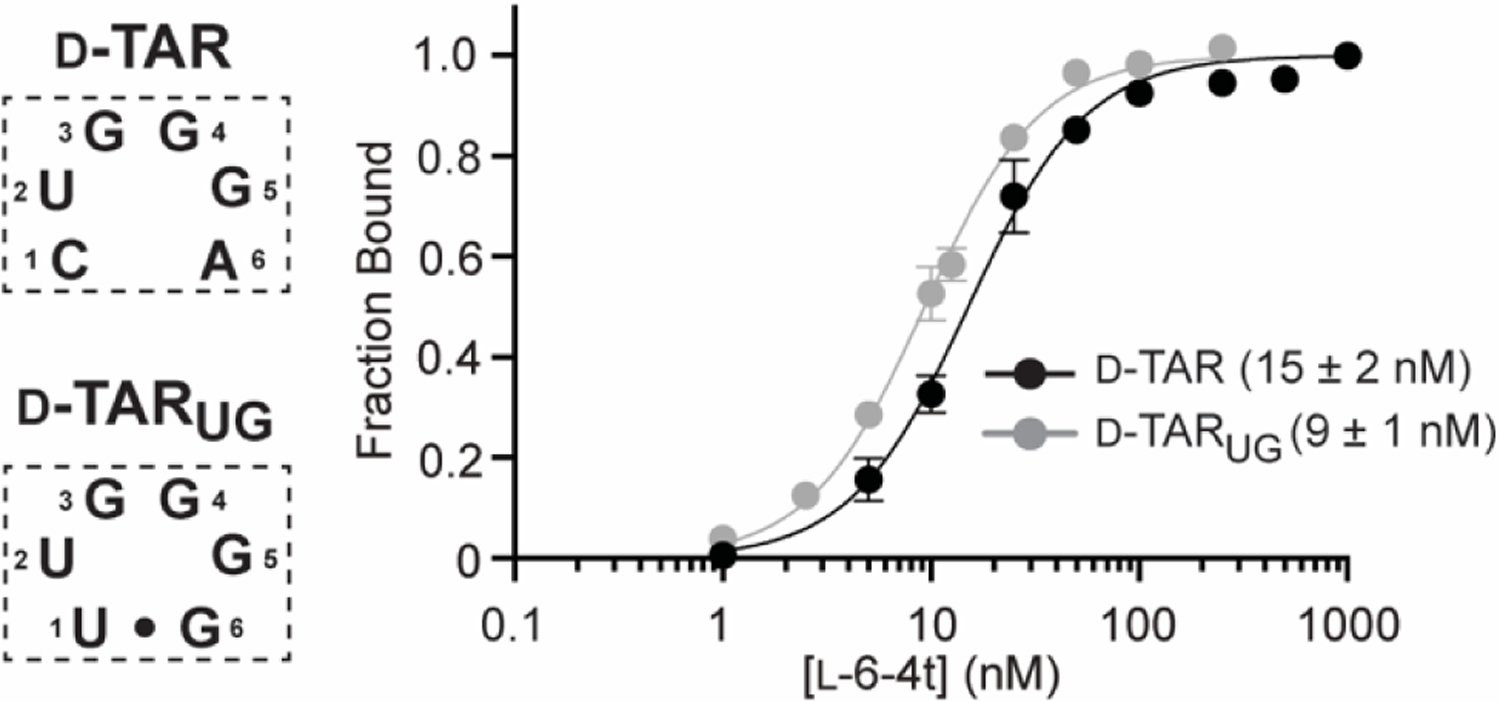

Remarkably, only two sequences were enriched during the in vitro selection process: wild-type D-TAR (5´-CUGGGA-3´) and a sequence (D-TARUG) containing two transition mutations at positions 1 and 6 of the loop (5´-UUGGGG-3´) (Figure 3). The two mutations in D-TARUG were not found individually within the enriched population, which would have resulted WC base pairing between positions 1 and 6 of the loop. This suggested that WC pairing between positions 1 and 6, but not the weaker G•U wobble pair found in D-TARUG, impairs the ability of L-6-4t to interact with these residues (Figure S2). Consistent with their nearly equal distribution in the final pool (Table S2), the Kd of D-TAR (15 ± 2 nM) and D-TARUG (9 ± 1 nM) for L-6-4t was similar, as determined by EMSA (Figure 3). While we can’t rule out that other sequences in the L6N library bind L-6-4t to some extent, the rapid and extensive enrichment of D-TAR and D-TARUG after just three rounds of in vitro selection suggested that their affinity for L-6-4t greatly exceeded that of all other possible 6-nt loops. Thus, in the context of a 6-nt loop, we conclude that L-6-4t binds with high selectively to target motif 5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3´, representing a single potential off-target sequence out of 4095. This strict sequence requirement is consistent with previously reported in-line probing data suggesting that the L-6-4t makes extensive contacts with all 6-nt in the distal loop of D-TAR.[9b]

Figure 3.

Saturation plots for binding of L-6-4t to D-TAR and D-TARUG. For simplicity, only the sequences of the 6-nt loop domain of the D-TAR hairpin is shown (boxed). The Kd is indicated in parenthesis. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Representative EMSA gels are depicted in Figures S3 and S6a.

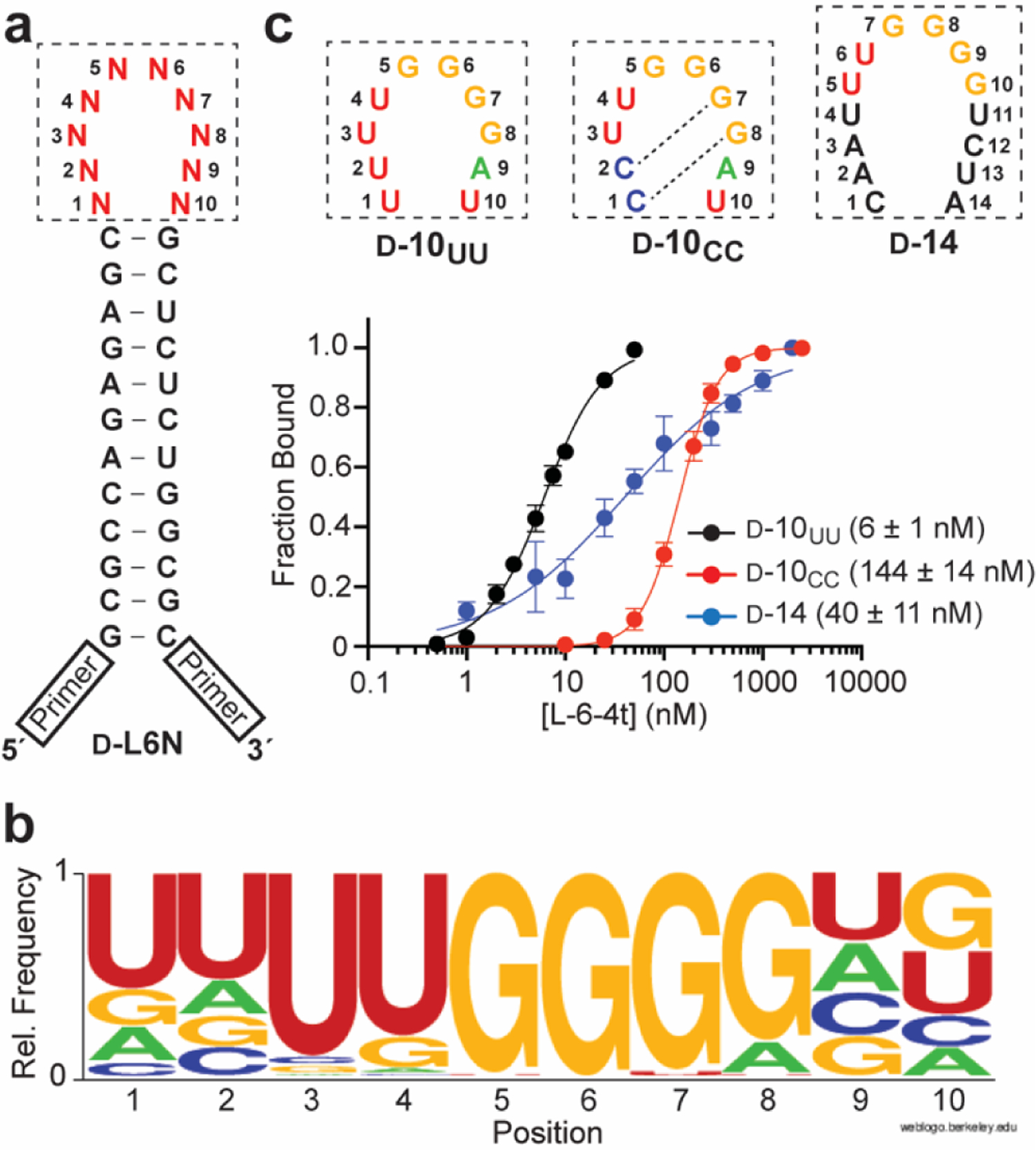

Realizing that loop domains within endogenous RNA structures are not limited to 6-nts, we next asked how expanding the D-TAR loop from 6-nt to 10-nt would impact the selectivity of L-6-4t. We chemically synthesized a variant D-TAR hairpin such that the 6-nt distal loop was replaced by a 10-nt random sequence domain, resulting in a 1,048,576-member library of hairpins containing all possible 10-nt loops (D-L10N; Figure 4a). The stem sequence in D-L10N was modified relative to D-L6N to allow sequences resulting from potential cross-contamination to be easily identified and removed from the final analysis. While the presence of the stem is essential for L-6-4t binding, the identity of the underlying nucleotides and the 3U bulge is not.[9b] Thus, these changes were not expected to impact L-6-4t binding. Library D-L10N was then subjected to the same inverse in vitro selection scheme as before. After the third round, the enriched D-L10N library was found to bind tightly to L-6-4t (Figure S4). The selection was stopped at this point and the enriched library was cloned and sequenced (Table S3).

Figure 4.

(a) Sequence and secondary structure of the D-L10N library. (b) Sequence logo depicting the relative frequency of nucleotides at each position within the random domain of D-L10N following 3-rounds of inverse selection (n = 70 sequences). (c) Saturation plots for binding of L-6-4t to D-10UU, D-10CC, and D-14. For simplicity, only the sequences of loop domain of the hairpin are shown (boxed). The Kd is indicated in parenthesis. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Representative EMSA gels are depicted in Figure S5.

Compared to the enriched 6-nt D-L6N library, there was considerably more diversity in the enriched D-L10N pool (Table S3). The consensus sequence for the 10-nt random domain from 70 individual clones is depicted in Figure 4b. Most strikingly, the vast majority of sequences (63 of 70, 90%) contained the 6-nt target motif identified above (5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3´), with a strong preference for the D-TARUG variant sequence. Moreover, when the 6-nt target motif was present, it was positioned at the center of the 10-nt random domain (positions 3–8; Figure 4b) 87% of the time. Positions 1 and 2 had a strong preference for U whereas positions 9 and 10 had a more even nucleotide distribution. To confirm that the sequencing results reflected actual binding properties, we determined the Kd of L-6-4t for a pair of model RNAs containing a central 5´-UUGGGG-3´ motif (positions 3–8) and either U (D-10UU) or C (D-10CC) at the first two positions of the loop domain, which are overrepresented and underrepresented in the population, respectively (Figure 4b). As expected from the sequencing results, we found that the Kd of D-10UU (6 ± 1 nM) was about 20-fold lower than D-10CC (144 ± 14 nM) (Figure 4c), confirming that the greater abundance of U compared to C at positions 1 and 2 reflects its higher affinity for L-6-4t. We used NUPACK[14] to investigate whether secondary structure could account for the different affinities of D-10UU and D-10CC for L-6-4t. Base pairing between residues within the 10-nt loop domain was predicted for both hairpins (Figure S2). However, the probability of these interactions at equilibrium was much greater for D-10CC due to the formation of strong C•G pairs between loop positions 1–2 and 7–8 (Figure 4c and Figure S2). The resulting secondary structure is expected to obstruct interactions with the 5´-UUGGGG-3´ motif, and thus, may contribute to the weaker binding of D-10CC to L-6-4t. It is worth noting that the Kd of L-6-4t for D-10UU is 2-fold lower than for D-TAR. Therefore, inverse in vitro selection can identify RNA structures with higher affinity for an L-aptamer compared to the original target.

Interestingly, the strong preference of the 5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3´motif for the center of 10-nt random domain (positions 3–8) was coupled to a lack of contiguous base pairing between the nucleotides on either side of this motif (Table S3). If G•U wobbles are excluded, only two sequences harboring a central 5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3 motif had full complementarity between the flanking nucleotides (i.e., base pairs 1•10 and 2•9). This suggested that destabilization of the stem adjoining the 5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3´motif provided an advantage for L-6-4t binding relative to a more constrained 6-nt loop of D-TAR, potentially by alleviating steric conflict between the stem and the L-aptamer and/or allowing greater conformational flexibility that facilitates binding. This is consistent with the higher affinity of D-10UU relative to D-TARUG. To further probe the relationship between loop size and L-6-4t binding, we prepared an RNA hairpin (D-14) with a 14-nt loop domain containing a centrally positioned 5´-UUGGGG-3´motif (Figure 4c). The 14-nt loop domain of D-14 was predicted to be primarily unpaired at equilibrium by NUPACK (Figure S6b).[14] Despite its increased loop size, L-6-4t still had considerable affinity for D-14 (Kd = 40 ± 11 nM; Figure 4c). The broad response of D-14 (Hill slope of 0.65) is most likely due to dimerization of the hairpin through loop-loop “kissing” interactions (Figure S6), which would compete with L-6-4t for binding to the 5´-UUGGGG-3´ motif. Nevertheless, this result indicates that L-6-4t has the capacity to bind the 5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3´ motif within a broad range of loop sizes.

Taken together, these results reveal that, while L-6-4t requires a hairpin loop containing the 5´-(C/U)UGGG(A/G)-3´motif for binding, the context of this target motif in terms of loop size and flanking nucleotides is actually quite variable, a characteristic that could result in potential off-target effects. This capacity for off-target binding was not previously identified using a small set of rationally designed D-TAR variants, highlighting the value of a more comprehensive approach for evaluating L-aptamer selectivity.

Finally, we asked whether L-6-4t could bind D-DNA, a property not previously investigated for RNA-binding cross-chiral aptamers. We prepared D-DNA versions of D-TAR (D-dTAR) and D-10UU (D-d10UU) and showed that L-6-4t was incapable of binding these DNA hairpins at aptamer concentrations far exceeding its Kd for native D-TAR RNA (Table S1 and Figure S7). Moreover, despite repeated attempts at inverse in vitro selection employing a DNA version of the D-L10N library, we were unable to enrich DNA hairpins that bind L-6-4t (data not shown). Thus, L-6-4t is incompatible with DNA ligands, at least for the library size tested herein. These results further support the notion that sequence-specific binding in the context of cross-chiral interactions is not limited to WC base pairing, and thus, can instead rely on other structural features that distinguish RNA from DNA (e.g., C5-methyl, 2′-OH, etc.).

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a novel “inverse” in vitro selection approach that enabled the first comprehensive characterization of cross-chiral aptamer selectivity. We showed that the TAR-binding L-aptamer L-6-4t is capable of binding its target sequence motif in various sequence and structural contexts, thereby revealing off-target interactions that were not previously identified using less comprehensive methods. However, L-6-4t failed to bind a D-DNA version of TAR, as well as, a library of TAR-derived DNA hairpins, suggesting it is unlikely to have off-target interactions with DNA. This represents a potential advantage over other classes of RNA-targeted reagents, especially those reliant on hybridization. It is important to note that selectivity is likely to be dependent on the specific L-aptamer-RNA pair, and thus, the results of this study should not be generalized for all cross-chiral aptamers. In the future it will be important to evaluate the selectivity of other cross-chiral aptamers using the approaches described herein, especially for those intended for applications in biological systems. A comprehensive view of target selectivity not only provides valuable information for assessing the likelihood and consequences of potential off-target interactions but can also reveal strategies to mitigate these effects. For example, off-target sequences or other promiscuous features of an RNA target identified by inverse in vitro selection could be employed in a counter-selection step during further L-aptamer evolution. In the case of L-6-4t, a counter selection against TAR-derived hairpins containing an expanded loop domain (e.g. D-10UU) could be used to reinforce selective binding to a 6-nt loop. Interestingly, during the course of this study we identified TAR hairpin variants with increased affinity for L-6-4t relative to the native target, suggesting that inverse in vitro selection could be used to further optimize cross-chiral interactions. Moreover, we imagine that inverse in vitro selection could be carried out on mutated versions of an L-aptamer in order to identify compensatory changes in the target RNA. Not only would such studies provide critical insights into the nature of the binding interaction, but would essentially generate orthogonal L-aptamer-RNA target pairs. Thus, in addition to identifying off-target interactions, inverse in vitro selection provides several opportunities to advance L-aptamer technology towards the goal of improved RNA affinity reagents.

Experimental Section

RNA library preparation.

The dsDNA library used to prepare D-L6N was generated from the templated cross-extension of 0.5 nmol L6N-CE1 and 0.5 nmol L6N-CE2 (Table S1) in a reaction mixture contained 8 U/μL Superscript II reverse transcriptase, 3 mM MgCl2, 75 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3), and 0.5 mM each of the four dNTPs. The reaction was carried out for 45 minutes at 42 °C, at which point the products of the reaction were ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 50 μL ultrapure water. The dsDNA library used to prepare D-L10N was generated via a 1 mL PCR reaction containing 50 pmol of template L10N-temp and 0.5 nmol of each Fwd.primer and Rev.primer (Table S1). The dsDNA products of the PCR were ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 50 μL ultrapure water. Approximately one-tenth of the dsDNA generated above was then used in a 100 μL transcription reaction containing 10 U/μL T7 RNA polymerase, 0.001 U/μL Inorganic pyrophosphatase (IPP), 25 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 10 mM DTT, 40 mM Tris (pH 7.9), and 5 mM of each of the four NTPs. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours. The resulting RNA (D-L6N or D-L10N) was concentrated by ethanol precipitation and purified by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) prior to use.

Inverse In vitro selection.

A 100 μL reaction mixture containing 25 pmol of either D-L6N or D-L10N RNA library, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6) was annealed at 70 °C for 1 minute and allowed to cool slowly to room temperature. The reaction mixture was added onto 1 mg of streptavidin coated magnetic beads (washed and pre-blocked following a previously established protocol[8a]) and incubated at 23 °C for 30 minutes. The supernatant was removed and the beads discarded to remove any bead-binding RNAs. To the retained supernatant was added 50 pmol of 5′- biotinylated L-6-4t and the solution was incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. At this point, 1.5 mg of streptavidin coated magnetic beads (pre-blocked as before) were added. After incubating for 1 hour at 23 °C, the beads were washed four times with 1 mL of the same buffer in order to remove weakly bound molecules. The retained RNA was eluted using two 150 μL portions of a stripping solution containing 25 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA. Both aliquots were quickly combined into a solution containing 30 μL of 3 M NaOAc, 30 μL of 1 M Tris (pH 7.6), and 4 μL glycogen (1 mg/mL). The RNA was then ethanol precipitated and used directly in a 50 μL reverse transcription reaction containing 10 U/μL RT, 3 mM MgCl2, 75 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3), and 0.5 mM each of the four dNTPs, which was incubated at 42 °C for 1 hour. The resulting cDNA was added as a template into a 1 mL scale PCR and amplified using Fwd.primer and Rev.primer (Table S1). The amplified DNA was ethanol precipitated and approximately half of the material was used to generate a new RNA library for the next round of selection. Following round 3, the enriched dsDNA pool was cloned into E. coli using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Bacteria were grown for 16 hours at 37 °C on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Individual colonies were amplified by PCR and sequenced by Eton Biosciences Inc. (San Diego, CA).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays:

The dissociation constant (Kd) of L-6-4t for the various D-RNA ligands was determined by EMSA as described previously.[9b] Briefly, a trace amount (0.1 – 1.0 nM) of the 5’-[32P]-labeled D-RNA hairpin ligand (or library) (Table S1) was mixed with various concentration of L-6-4t in a 20 μL reaction mixture containing 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.6), and 0.1 mg/mL tRNA. After incubating for 30 minutes at 23 °C, an aliquot was removed and analyzed by 8% native PAGE (19:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) containing 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KOAc, 20 mM NaOAc and 25 mM Tris (pH 7.6). Electrophoresis was carried out at 6–8 V/cm (0.75 mm thick gel) for 4 h at 4 °C and the gel visualized by autoradiography using a Typhoon FLA-9500 Molecular Imager (General Electric Co., Boston, MA). Binding of L-6-4t to D-DNA ligands was determined similarly, except that 10 nM of the 5′-fluorescein labeled DNA (Table S1) was used in the binding reaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM124974) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Welch Foundation (A-1909-20190330).

References

- [1].Ganser LR, Kelly ML, Herschlag D, Al-Hashimi HM, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2019, 20, 474–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wan Y, Kertesz M, Spitale RC, Segal E, Chang HY, Nat. Rev. Genet 2011, 12, 641–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Bernat V, Disney MD, Neuron 2015, 87, 28–46; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Croce CM, Nat. Rev. Genet 2009, 10, 704–714; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jaafar ZA, Kieft JS, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2019, 17, 110–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Falese JP, Donlic A, Hargrove AE, Chem. Soc. Rev 2021, 50, 2224–2243; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sheridan C, Nat. Biotechnol 2021, 39, 6–8; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Costales MG, Childs-Disney JL, Haniff HS, Disney MD, J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 8880–8900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Guan L, Disney MD, ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7, 73–86; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shortridge MD, Varani G, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2015, 30, 79–88; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Thomas JR, Hergenrother PJ, Chem. Rev 2008, 108, 1171–1224; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Velagapudi SP, Gallo SM, Disney MD, Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 292–297; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Pal S, ‘t Hart P, Front. Mol. Biosci 2022, 9; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Chen Y, Yang F, Zubovic L, Pavelitz T, Yang W, Godin K, Walker M, Zheng S, Macchi P, Varani G, Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 717–723; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Koirala D, Lewicka A, Koldobskaya Y, Huang H, Piccirilli JA, ACS Chem. Biol 2020, 15, 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Klussmann S, Nolte A, Bald R, Erdmann VA, Fürste JP, Nat. Biotechnol 1996, 14, 1112–1115; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nolte A, Klussmann S, Bald R, Erdmann VA, Furste JP, Nat. Biotechnol 1996, 14, 1116–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Ashley GW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 9732–9736; [Google Scholar]; b) Garbesi A, Capobianco ML, Colonna FP, Tondelli L, Arcamone F, Manzini G, Hilbers CW, Aelen JME, Blommers MJJ, Nucleic Acids Res 1993, 21, 4159–4165; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hoehlig K, Bethge L, Klussmann S, PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0115328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Dey S, Sczepanski JT, Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 1669–1680; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kabza AM, Sczepanski JT, ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1824–1827; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sczepanski JT, Li J, RSC Chem. Biol 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Sczepanski JT, Joyce GF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 16032–16037; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sczepanski JT, Joyce GF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13290–13293; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Umar MI, Kwok CK, Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 10125–10141; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chan C-Y, Kwok CK, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 5293–5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Hauser NC, Martinez R, Jacob A, Rupp S, Hoheisel JD, Matysiak S, Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, 5101–5111; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Urata H, Ogura E, Shinohara K, Ueda Y, Akagi M, Nucleic Acids Res 1992, 20, 3325–3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Dantsu YZ, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Genes 2022, 13, 46; [Google Scholar]; b) Young BE, Kundu N, Sczepanski JT, Chem. Eur. J 2019, 25, 7981–7990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Warner KD, Hajdin CE, Weeks KM, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2018, 17, 547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tuerk C, Gold L, Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zadeh Joseph N, Steenberg Conrad D, Bois Justin S, Wolfe Brian R, Pierce Marshall B, Khan Asif R, Dirks Robert M, Pierce Niles A, J. Comput. Chem 2011, 32, 170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.