Abstract

Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) is a toxin-mediated disease. It is a severe fatal disease inducing immune-mediated inflammatory reaction and occurs because of exotoxin produced by Staphylococcus aureus. Common signs and symptoms at the time of presentation lead to misdiagnosis and delay in initiation of treatment. Prognosis depends primarily on early diagnosis and prompt treatment. This is a case of a young adult male presented with fever, rash, and hypotension and diagnosed with STSS.

Keywords: Multi-organ involvement, skin infection, staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, toxin-mediated inflammatory reaction

Introduction

Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) is a clinical disorder comprising fever, rash, hypotension, and multi-organ failure.[1] Primary pathogenesis is a toxin-mediated severe immunological inflammatory response affecting multiple organs. STSS has a grave prognosis; it warrants early suspicion, diagnosis, and prompt treatment, so we are presenting the following case report in which early diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment changed the outcome of the patient.

Case Report

A 19-year-old male presented to emergency with complaints of acute onset high-grade fever, with chills for 7 days, followed by diffuse macular rash, initially over the palm [Figure 1], then extremities, and later the whole body after 2 days, followed by desquamation [Figure 2] after 6–7 days of admission. Subsequently, he developed shortness of breath, which was progressive in nature and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II. On history taking, he had a travel history to a coastal area (Goa) 4 weeks back. After 1 week of returning from Goa, he developed a boil in the gluteal region. Later on, he developed another boil in the pubic area within the next 2–3 days, for which he took treatment from the local practitioner [Figure 3]. On general examination, he was conscious, cooperative, and oriented to time, place, and person and was febrile (temperature 102.1°f axillary), with a pulse rate of 130/min, a low volume, regular, all peripheral pulses palpable, a respiratory rate of 20/minute, thoraco abdominal, regular, and a blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg in the right arm supine position. He had conjunctival congestion [Figure 4], and oral cavity examination revealed prominent, inflamed, and hypertrophic fungiform papillae with hyperemia, suggestive of a strawberry tongue [Figure 5]. The rest of the general physical examination was normal. Systemic examination revealed a palpable liver 1 cm below the right costal margin in the mid-clavicular line, which was firm and non-tender with a regular surface. There was no neurological deficit on examination. Urgent arterial blood gas (ABG) revealed compensatory metabolic acidosis. Routine investigation revealed normocytic normochromic anemia (Hb 10.5 gm/dl), neutrophilic leucocytosis (TLC 17.55 × 109/L), and a normal platelet count (150 × 109/L). Blood and urine culture were sent before starting empirical antibiotic therapy. Liver function test revealed hypoalbuminemia (albumin 2.5 mg/dl), globulin (2.2 mg/dl), and raised liver enzymes (SGOT 63 U/L, SGPT 48 U/L, ALP 82 U/L, GGT 35 U/L). The renal profile showed acute kidney injury (urea 186 mg/dl, creatinine 3.8 mg/dl), hyponatremia (Na 126 mmol/L), and hyperkalemia (K 6 mmol/L). The rest of the work-up including the fever profile and viral profile was sent and was inconclusive. The work-up for atypical infections (scrub typhus, Weil felix test, Leptospira antibody) was negative. The chest X-ray posteroanterior view revealed no focal parenchymal lesion, and the ultrasonography whole abdomen showed mild hepatomegaly.

Figure 1.

Diffuse macular rash over the palm

Figure 2.

Desquamation over the palm after 6–7 days of discharge

Figure 3.

Boil and sinus in the pubic region

Figure 4.

Conjunctival congestion

Figure 5.

Prominent, inflamed, and hypertrophic fungiform papillae with hyperemia, suggestive of a strawberry tongue

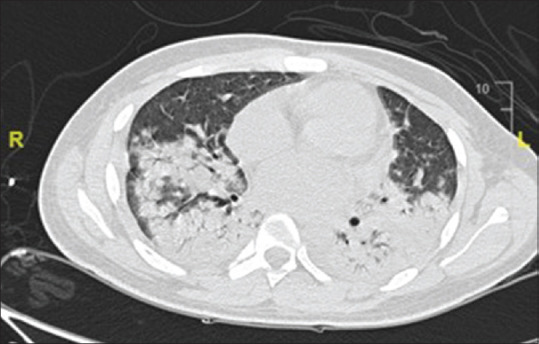

In view of initial assessment, the diagnosis of STSS was kept in mind, and he was started with empirical IV piperacilin + tazobactum, doxycycline, and linezolid, with IV fluids. His condition continued to deteriorate, and he was started on inotropes and placed on a non-invasive ventilator (NIV). Incision and drainage of the boil in the left gluteal region were performed, and the pus samples were sent for culture and sensitivity. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) thorax was performed in view of desaturation, which showed dense lobar consolidations in the bilateral lower lobe with the area of consolidation in the posterior aspect of the right upper lobe and the multiple scattered nodular area of consolidation with conglomeration in the bilateral upper lobe along with mild bilateral pleural effusion [Figure 6]. Gram staining of pus showed that Gram-positive cocci in clusters and culture revealed growth of Staphylococcus aureus. Gradually, he improved with initiation of antibiotics and pus drainage. He was stable and doing well on the last follow-up after 7 days of discharge.

Figure 6.

CECT thorax showed dense lobar consolidations in the bilateral lower lobe with the area of consolidation in the posterior aspect of the right upper lobe and the multiple scattered nodular area of consolidation with conglomeration in the bilateral upper lobe along with mild bilateral pleural effusion

Discussion

Staphylococcus aureus causes a wide spectrum of clinical presentation ranging from asymptomatic carriers to toxic shock syndrome. STSS is defined as clinical illness characterized by rapid onset of fever, rash, hypotension, and multi-organ involvement caused by toxin released by Staphylococcus aureus.[1] Toxic shock syndrome has been classified into two types on the basis of etiology, that is, menstrual and non-menstrual cases, and various clinical circumstances such as surgical and postpartum wound infection, mastitis, septorhinoplasty, sinusitis, osteomyelitis, arthritis, burns, respiratory infection following influenza, enterocolitis, and cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions (especially of the extremities, peri-anal area, and axilla) were the major contributors to the atypical STSS group.[2]

It is a potentially fatal disease affecting multiple systems,[3] with the mortality rate at approximately 6%.[4] Irreversible respiratory failure, refractory cardiac arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathy have been the common causes of death in STSS.[5,6]

STSS has varied presentation and can mimic other diseases, so the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) gave diagnostic criteria; a confirmed case is a case which has fever, hypotension, diffuse erythroderma, desquamation, and involvement of at least three organ systems, with culture negative for alternative pathogens and serologic tests negative for other conditions.[7] STSS should be suspected in all cases with fever, rash, hypotension, and multi-organ system involvement, with relevant risk factors including recent surgery, recent tampon use, and recent dermatological and soft tissue infection, which is a crucial point in focus of diagnosis of STSS. Staphylococcus aureus is not isolated; however, it can be isolated from wound or mucosal sites in 80–90% cases.[8]

Pathogenesis of STSS is based on host immune response to Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins. Exotoxin TSST-1 was initially implicated to tampon use in menstruation, but 40–60% strains were associated with atypical (non-menstrual) STSS cases. TSST-1, staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) and staphylococcal enterotoxin C (SEC), and other potential toxins such as enterotoxins A, B, C, D, E, and H are collectively called as pyrogen toxin super-antigens (Sags). These super-antigens activate a large number of T-cells by directly interacting with the invariant region of class 2 MHC molecules, without processing by antigen presenting cells, leading to massive cytokine production.[9,10]

Common clinical manifestations of STSS include fever, chills, and hypotension. Massive release of cytokines induced by toxins leads to a decrease in systemic vascular resistance, and leakage of the fluid from the intra-vascular space to the interstitial space causes hypotension, which is unresponsive to intravenous fluids and could lead to tissue ischemia and organ failure.[11]

STSS can involve the gastrointestinal system, liver, kidney, and nervous system along with the skin. Dermatological manifestations include diffuse macular erythroderma initially, with desquamation after 1–2 weeks. Superficial ulceration on mucosal membranes with petechiae, vesicles, and bullae develop in severe cases.[7] Conjunctival-scleral hemorrhage and vaginal and oropharyngeal mucosal hyperemia can also occur.[11] Gastrointestinal symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, and watery and bloody diarrhoea. Neurological manifestation usually occurs because of cerebral edema causing encephalopathy manifested as disorientation, confusion, or seizure.[12] Severe shock and multiple organ failure can be the extreme manifestations of STSS, leading to acute kidney injury, elevated liver enzymes, and metabolic acidosis.[13,14]

The management strategy should be focused on early initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, aggressive treatment of shock, and proper source control.[15]

Empirical antibiotic therapy should be focused to eradicate Staphylococcus. Clindamycin should be included in the treatment regimen because of its property to suppress the synthesis of bacterial toxins, and linezolid should be used as an alternative in the case of resistance.[8,16] Intravenous immunoglobulin use should be restricted as an adjunctive therapy in patients who are unresponsive to other therapeutic measures.[17]

Conclusion

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of STSS lead to better prognosis. The purpose of this case report is to emphasize on meticulous history taking and clinical examination to evade the worst progression of the disease.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has giver his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that name and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Research quality and ethics statement

The authors follow CARE guideline during the conduct of this report.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Todd J, Fishaut M, Kapral F, Welch T. Toxic-shock syndrome associated with phage-group-1 Staphylococci. Lancet. 1978;2:1116–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotler DP, Sandkovsky U, Schlievert PM, Sordillo EM. Toxic shock-like syndrome associated with staphylococcal enterocolitis in an HIV-infected man. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:121–3. doi: 10.1086/518286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy P, Sahni AK, Kumar A. A fatal case of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71(Suppl 1):S107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broome CV. Epidemilogy of toxic shock syndrome in the united states: Overview. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl 1):S14. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_1.s14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larkin SM, Williams DN, Osterholm MT, Tofte RW, Posalaky Z. Toxic shock syndrome: Clinical, laboratory, and pathologic findings in nine fatal cases. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:858–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-6-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paris AL, Herwaldt LA, Blum D, Schmid GP, Shands KN, Broome CV. Pathologic findings in twelve fatal cases of toxic shock syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:852–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-6-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case definitions for infectious conditions under public health surveillance. Centers for disease control and prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis JP, Osterholm MT, Helms CM, Vergeront JM, Wintermeyer LA, Forfang JC, et al. Tri-state toxic-shock syndrome study. II. Clinical and laboratory findings. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:441–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlievert PM. Role of superantigens in human disease. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:997–1002. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kum WW, Laupland KB, Chow AW. Defining a novel domain of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 critical for major histocompatibility complex class II binding, superantigenic activity, and lethality. Can J Microbiol. 2000;46:171–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesney PJ, Davis JP, Purdy WK, Wand PJ, Chesney RW. Clinical manifestations of toxic shock syndrome. JAMA. 1981;246:741–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith DB, Gulinson J. Fatal cerebral edema complicating toxic shock syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:598–9. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198803000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesney RW, Chesney PJ, Davis JP, Segar WE. Renal manifestations of the staphylococcal toxic-shock syndrome. Am J Med. 1981;71:583–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gourly GR, Chesney PJ, Davis JP, Odell GB. Acute cholestasis in patients with toxic-shock syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:928–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lappin E, Ferguson AJ. Gram-positive toxic shock syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:281–90. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis JP, Chesney PJ, Wand PJ, LaVenture M. Toxic-shock syndrome: epidemiologic features, recurrence, risk factors, and prevention. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1429–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012183032501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimberlin DW, Barnett ED, Lynfield R, Sawyer MH, editors. 32nd ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021. American Academy of Pedicatrics. Red Book 2021-2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. [Google Scholar]