Abstract

In optical devices such as camera or microscope, an aperture is used to regulate light intensity for imaging. Here we report the discovery and construction of a durable bio-aperture at nanometerscale that can regulate current at the pico-ampere scale. The nano-aperture is made of 12 identical protein subunits that form a 3.6-nm channel with a shutter and “one-way traffic” property. This shutter responds to electrical potential differences across the aperture and can be turned off for double stranded DNA translocation. This voltage enables directional control, and three-step regulation for opening and closing. The nano-aperture was constructed in vitro and purified into homogeneity. The aperture was stable at pH2–12, and a temperature of −85C to 60C. When an electrical potential was held, three reproducible discrete steps of current flowing through the channel were recorded. Each step reduced 32% of the channel dimension evident by the reduction of the measured current flowing through the aperture. The current change is due to the change of the resistance of aperture size. The transition between these three distinct steps and the direction of the current was controlled via the polarity of the voltage applied across the aperture. When the C-terminal of the aperture was fused to an antigen, the antibody and antigen interaction resulted in a 32% reduction of the channel size. This phenomenon was used for disease diagnosis since the incubation of the antigen- nano-aperture with a specific cancer antibody resulted in a change of 32% of current. The purified truncated cone-shape aperture automatically self-assembled efficiently into a sheet of the tetragonal array via head-to-tail self-interaction. The nano-aperture discovery with a controllable shutter, discrete-step current regulation, formation of tetragonal sheet, and one-way current traffic provides a nanoscale electrical circuit rectifier for nanodevices and disease diagnosis.

Keywords: Nanobiotechnology, nano-rectifier, nano-aperture, nanomotor, Nanoelectronics, Nanoelectromechanical system

INTRODUCTION

Life is perpetuated by a set of nanomachines that replicate and adapt with intricate functions1. Protein-based nanomaterials are one of these bioinspired materials that combine the advantage of nanomaterials’ size, shape, and surface chemistry, as well as biocompatibility and biodegradability2, 3. There are many exciting developments in bioinspired nanomaterials using proteins for tissue engineering4–6, drug delivery7–11, disease diagnosis12, 13, gene modification, DNA sequencing, single molecule sensing7, 8, 14–16 and application in other intelligent device17, 18. This provides the impetus for our foray into applying our understanding of the viral DNA packaging motors, which contain an elegant and elaborate channel complex, onto nanotechnology and nanomedicine.

Protein nanomaterials with a variety of controlled shapes and sizes have been wildly developed 19, 20. For example, α-helical motifs can self-assemble into various structures from fibers by star-burst arrangements to function as polynanoreactors21. Proteins can form a variety of sophisticated structures such as ferritin, chaperonins, and viral capsids 22–24,25. A diaphragm model has also been proposed to be related to DNA packaging and control in phage SPP159. Nano-tubulars have attracted tremendous interest due to their unique features, like improving viscosity due to their long length and low diameters, high surface/volume ratio, gelling ability, and biocompatibility 26–34. The accumulation of peptides into amyloid fibers in Parkinson’s disease inspired the self-assembly of nanotubes, which possess excellent robustness and electrical conductivity35, 36. The one-dimensional protein bundles assembled by metalorganic protein frameworks could mimic collagen assembly in biomineralization processes37. Also, genetically engineered bacterial proteins showed great potential for the fabrication of nanotubes38.

Here, we reported the finding and application of protein-based nano-aperture towards tumor diagnosis. The nano-aperture is made of 12 identical protein subunits from the Phi29 nano-motor. When an electrical potential was held across the nano-aperture, three reproducible discrete steps of current change were recorded.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Physical property and mechanical structure of the nano-aperture.

The aperture of a camera or microscope alters its diameter to control the amount of light flowing through its opening39 (Figure 1A–D). The voltage-controlled nano-aperture, which is a component of nano-motor40 (Phi29 DNA packaging motor), described here displays a structure and appearance similar to the cameral aperture (Figure 1E), albeit at a nanometer scale41. The twelve identical subunits of the aperture tilt 30° in a spiral configuration with a left-handed chirality, thus facilitating the directional control for one-way traffic through the aperture42–44. The X-ray crystallography (PDB ID: IFOU) shows this protein nano-aperture appears as a truncated cone (Figure 2D), with a length of 7.5 nm, a diameter of 13.8 nm for the top (C-Terminal), and 7.8 nm for the bottom (N-Terminal) (Figure 2D). When the nano-aperture is completely open, the narrowest center channel is 3.6 nm in diameter41. In nature, an anti-parallel arrangement of an aperture with a left-handed configuration facilitates the right-handed dsDNA helix to pass through the aperture via a revolving mechanism. In each step of the revolution that moves the dsDNA to the next subunit, the dsDNA physically moves to a second point on the aperture channel wall, keeping a 30° angle between the two segments of the DNA strand (Figure 1F). This structural arrangement enables the dsDNA to touch each of the 12 connector subunits (GP10 protein) in 12 discrete steps of 30° transitions for each helical pitch (Figure 1F).

Fig. 1. Structure of the camera-like nano-aperture.

(A-D) Structure of a camera aperture with stepwise-closing. (E) Crystal structure of the connector of phi29 DNA packaging motor showing the tilting of the 12 protein-subunit with 30° angle between two adjacent connector subunits. (F) Top: Illustration of one 360°-circle divided into 12 sections, showing the shift of 30° angle between two adjacent sections. Bottom: Illustration of one 360°-helical turn of dsDNA divided into 12 steps, showing the shift of 30° angle between two sequential steps.

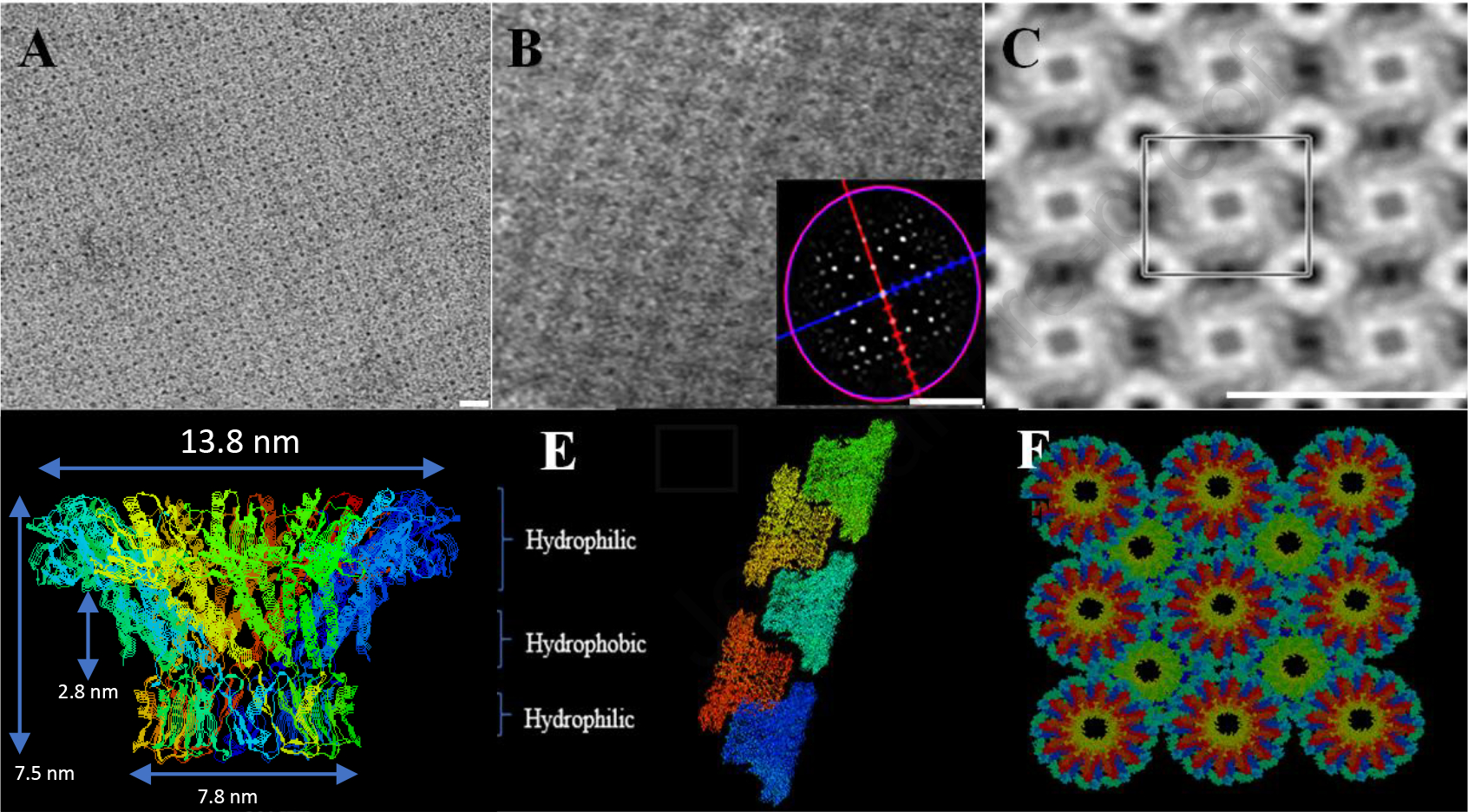

Fig. 2. Images of the pacified nano-aperture.

(A-C) TEM images of the fabricated purified nano-aperture, self-assembled into a tetragonal array. The scale bar is 25 nm. (D) Side view of the nano-aperture crystal structure. (E-F) Computationally constructed structure displaying the array structure assembled by alternative up and down arrangement, showing dimensions and polarity.

Fabrication, production, and purification of the durable homogeneous nano-aperture in large scale.

This protein nano-aperture was produced on a large scale and purified into homogeneity, with 1017 nano-aperture particles per milliliter by nickel column purification. Industrial-scale fabrication is feasible. The purified nano-aperture can efficiently self-assemble into regular tetragonal arrays via the up-and-down alternating arrangement, as observed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2A–C). Deepview/Swiss-PDBViewer program45 was used to construct 3D models of regular tetragonal arrays models. In this model, the subunit of each aperture was arranged in an alternating up and down arrangement (Figure 2E and F). The distance between each dodecamer was adjusted to 165 Å. The nano-aperture is stable at −80 to +60 °C and resistant to a pH 2–14. The homogeneity of the observed nanopore from TEM indicates high yield and reproducibility across the sample’s constituency.

Two-way traffic of peptide translocation was found in the channel of the mutant nano-aperture.

The nano-motor uses a “Revolving Through One-Way Valve” mechanism46. The protein nano-aperture with left-handed chirality functions as a one-way valve. This special structure allows DNA, to be transported with a single directional motion through the channel42. However, the one-way traffic property of the aperture can be changed into two-way traffic by the removal of 17 amino acid residues (aa 229–246) from the internal channel wall (Figure 3A), evidenced by the two-way traffic property of a peptide through the mutant nano-aperture channel (Figure 3B). The unfolded peptides is about 2 nm in diameter, similar to the diameter of dsDNA. The current blockage spike looks similar to the dsDNA indicating translocation in a similar manner. However, the rate of peptide translocation from the C-terminus to the N-terminus is lower than the translocation from the N to C, suggesting the 30-degree left chirality of the channel wall still plays a role in affecting the traffic direction. The sensing and translocation of peptides is still hampered by a lack of unique signatures that are one-to-one and onto each of the amino acids. Further investigation into how the aperture can be adjusted using the one- and two-way traffic to better discriminate against amino acids for differentiation will enable significantly improved diagnostics.

Fig. 3. One-way traffic of a nano-aperture.

(A-B) “One-way” DNA translocation of the connector of phi29 DNA packaging motor under a ramping potential from −100mV to +100mV (data from42). The change of the connector orientation leads to the appearance of current blockage spikes when dsDNA was placed at both trans and cis sides of the chamber (data from42). (C) No DNA in either chamber as negative control (data from42). (D) Alteration of voltage polarity to demonstrate that DNA can only be translocated from one side at one kind of polarity, when DNA was placed in both trans and cis chambers(data from42). (E) Illustration showing the flexible inner channel loops (green color) of the phi29 connector. (F) Two-way traffic property of peptide through the internal loop-deleted Phi29 connector. Figures were adapted with permission from42 Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Three steps of gate size transition were confirmed by electrical conductance assays.

When the nano-aperture was inserted into a membrane, the aperture’s closure can be controlled by holding the voltage, (the electrical potential difference across the connector) to specific values. This was true in the connectors from the Phi29, SPP1, T3 and T447. Here, a 3-step channel size reduction was also observed when a high potential was applied to the wild type Phi29 (120 mV), and T7 (140 mV), as well as the N-terminal (N-Δ14-N-His Phi29 with the deletion of the first 14 amino acids at the N-terminus) (80 mV) and C-terminal (C-Δ25-C-Strep Phi29 with the deletion of the last 25 amino acids at the C-terminus) (150 mV) loop deleted Phi29 connectors (Figure 4 A, B, D, E). Each step reduces the channel dimension by 32%, as evidenced by the decrease in applied current. The resistance across the membrane increases in response to the closing channel, like ion channels in neurons. An exact 32%, 64% and 96% current change was detected when a formula of Ia/Io was applied to calculate the current variation in response to translocation and conformational changes, where Io is the original current and Ia is the instantaneous current. Interestingly, a high enough voltage is not all that is needed to trigger gating, a nano-aperture with the C-terminal modified with a urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) binding peptide, once incubated with the uPAR protein, can undergo gating in its entirety (Figure 4C). It should be mentioned that uPAR has proven to be predictive biomarkers in several types of cancer, including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and pulmonary adenocarcinoma48. Three-step reopening of a closed nano-aperture has been observed after applying a low voltage, which can be readily described in a similar manner with three steps (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4. Three-step gating of connector nano-aperture of phage DNA packaging motors.

The observed dip in (A) into the 2nd step of the phi29 conformation while still in the 1st step indicates that the gating conformational changes are reversible and there are varying degrees of stability within each of the conformational states.

It is very interesting to find that in all three discrete steps of channel size reduction, the rate of reduction is all about 32%. The 32% of reduction is a rate almost identical to the rate of current blockage by dsDNA. Although the mechanism that leads to such novelty of the three 32%-reduction steps is a mystery, it is hypothesized that, during the viral evolution, the conformational change in change size reduction is a correspondence to the size of the dsDNA. That is, dsDNA has served as a mold for the adaptation of the conformational change during the mutation and adaptation process. Alternative mechanisms include that the connector subunits may independently and ubiquitously undergo conformational changes in the presence of a potential difference across the connectors, evident of an induced fit model of dsDNA translocation. The three steps would then represent the three conformational states the connector adopts in the process of dsDNA translocation.

Application of the nano-aperture for cancer biomarkers detection at the single molecule level.

We then sought out towards using this method of rapid detection of conformational change of the connector via a 32% reduction towards cancer biomarker detection. A conductance assay using an aperture conjugated with a six-histidine His-tag to the C-terminal and incubated with an anti-his tag antibody or nanogold coated with Ni-NTA, triggered one-step of conformational change; similar to the first step of gating shown in Figure 4 49, which inspired the application of the nano-aperture for single-molecule detection of antigens or antibodies by antigen-antibody interaction. Utilization of engineered protein nano-apertures with an 18-amino acid Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EpCAM) detection peptide at its C-terminal (Figure 5A), colon cancer-specific EpCAM antibody-specific binding events could be detected in real-time at the single-molecule level in 0.4 M KCl, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 conductance buffer (Figure 5B). This engineered protein nano-aperture can discriminate the signal from background events with high sensitivity (Figure 5C). The result also supported the conclusion that the shutter is located at the C-terminal (Figure 5). This conclusion was also supported by the fact that the deletion of 25 amino acids at the C-terminal disabled the three-step gating capacity49.

Fig. 5. Real-time sensing of EpCAM antibody (Ab) interactions with EpCAM antigen (Ag) using engineered phi29 connector nano-aperture, demonstrating the C-terminal is the shutter triggering the step-wise conformational change.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the placement of the colon cancer Ag into the C-terminal of the phi29 connector for real-time detection of the Ag with its corresponding Ab. (B) Histogram of current blockage events caused by the addition of diluted EpCAM Ab. (C) Histogram plotting of current transition events of specific (green) and nonspecific (red) binding to the shutter at the C–terminal caused by Ab/Ag interactions.

The nano-aperture was also re-engineered with uPAR binding peptide to its C-terminal. uPAR is the biomarker of breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Once incubated with the uPAR protein in 0.15 M KCl, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 conductance buffer, the binding signals of the uPAR protein to the C-terminal peptide were observed, evidenced by three steps gating (Figure 3C), current blockage histogram, and scatter plot result.

These nano-apertures are larger than 3 nm in diameter, making them more amenable as a single-molecule sensing platform with an advantage over other biological membrane pores which are about 1.2 nm. The uniform dimensions and homogeneous pore size make the sensing and other practical applications more reproducible. Generally, the nanopore sensing mechanism is dependent on the resistive pulse technique. Once an electrical potential is applied across the aperture, the sample molecules translocating through the aperture will generate a unique electrical current signature due to the changes in ion flow caused by the blockage46. Thus, measuring the current alternation and dwell time (length of the event) of translocation events will serve as the signature of the analytes. When different molecules, such as DNA, RNA, or peptides pass through the nano-aperture, unique, distinctive current signatures and dwell times will be generated, which can serve as the fingerprint for the identification of the corresponding molecules. Nano-apertures have been applied to the sensing of RNA, DNA50–54, chemical55. The gating mechanism could be harnessed to prove a unique third variable to the blockage signature of the translocating analytes for high-resolution discrimination. It has also been used for the differentiation of peptides with only one amino acid difference in length56 or in composition. The nano-aperture is capable of differentiating between diverse conformations of a protein57. It has also been used for quantitative analysis of the kinetic process of peptide oligomerization in real-time at the single molecule level58.

CONCLUSION

A nano-aperture with a voltage-dependent shutter system for size control has been identified and constructed. The adjustable channel size and trafficking direction made it possible to alter the aperture from one-way traffic to two-way traffic. These controllable characteristics in pore size and motion direction unleash the potential for the nano-aperture to serve as a nano-electric rectifier. The production of electrical signature from such nano-apertures have been applied to the fingerprinting of DNA, RNA, protein, chemical, and antibody. This concept enables investigation towards more precise differentiation of small molecule blockage signatures during translocation for better discrimination between small analytes. The system can be used for diagnosis via the detection of detect current change driven by small molecule binding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The research was supported by NIH grant R01 EB012135, and a sponsored research by Oxford Nanopore Technologies Ltd.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

P.G. is the consultant of Oxford Nanopore Technologies; the cofounder of Shenzhen P&Z Biomedical Co. Ltd., as well as co-founder and board member of ExonanoRNA, LLC and its subsidiary Weina Biomedical LLC.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Credit Author Statement:

P.G. conceived and designed the project. A.B, L. Z, and N.B prepared the manuscript, carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. A.B, L.Z.,N.B and P.G. cowrote the manuscript, and all authors refined the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Goel A; Vogel V Nat Nanotechnol 2008, 3, (8), 465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner V; Dullaart A; Bock AK; Zweck A Nat Biotechnol 2006, 24, (10), 1211–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raman R; Bashir R Adv Healthc Mater 2017, 6, (20). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raftery RM; Woods B; Marques ALP; Moreira-Silva J; Silva TH; Cryan SA; Reis RL; O’Brien FJ Acta Biomater 2016, 43, 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gil ES; Mandal BB; Park SH; Marchant JK; Omenetto FG; Kaplan DL Biomaterials 2010, 31, (34), 8953–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang HJ; Kim YM; Yoo BY; Seo YK J Biomater Appl 2018, 32, (6), 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L; Hu F; Wang H; Wu X; Eltahan AS; Stanford S; Bottini N; Xiao H; Bottini M; Guo W; Liang XJ ACS Nano 2019, 13, (5), 5036–5048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang Y; Liang J; Wu A; Chen Y; Zhao P; Lin T; Zhang M; Xu Q; Wang J; Huang Y ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, (2), 3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He YJ; Xing L; Cui PF; Zhang JL; Zhu Y; Qiao JB; Lyu JY; Zhang M; Luo CQ; Zhou YX; Lu N; Jiang HL Biomaterials 2017, 113, 266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu L; Liu J; Xi J; Li Q; Chang B; Duan X; Wang G; Wang S; Wang Z; Wang L Small 2018, e1800785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo W; Deng L; Yu J; Chen Z; Woo Y; Liu H; Li T; Lin T; Chen H; Zhao M; Zhang L; Li G; Hu Y Drug Deliv 2018, 25, (1), 1103–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao W; Wang Z; Chen L; Huang C; Huang Y; Jia N Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2017, 78, 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye L; Huang NL; Ma XL; Schneider M; Huang XJ; Du WD Biosens Bioelectron 2016, 78, 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravindran S; George A Front Physiol 2015, 6, 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang Y; Yao S; Chen Y; Huang J; Wu A; Zhang M; Xu F; Li F; Huang Y Nanoscale 2019, 11, (2), 611–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rink JS; Sun W; Misener S; Wang JJ; Zhang ZJ; Kibbe MR; Dravid VP; Venkatraman S; Thaxton CS ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, (8), 6904–6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerette PA; Hoon S; Seow Y; Raida M; Masic A; Wong FT; Ho VH; Kong KW; Demirel MC; Pena-Francesch A; Amini S; Tay GZ; Ding D; Miserez A Nat Biotechnol 2013, 31, (10), 908–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang D; Wang Y Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Rica R; Matsui H Chem Soc Rev 2010, 39, (9), 3499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai W; Sargent CJ; Choi JM; Pappu RV; Zhang F Nat Commun 2019, 10, (1), 3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryadnov MG Biochem Soc Trans 2007, 35, (Pt 3), 487–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kant R; Rayaprolu V; McDonald K; Bothner B J Biol Phys 2018, 44, (2), 211–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panahandeh S; Li S; Zandi R Nanoscale 2018, 10, (48), 22802–22809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sainsbury F ACS Nano 2020, 14, (3), 2565–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rother M; Nussbaumer MG; Renggli K; Bruns N Chem Soc Rev 2016, 45, (22), 6213–6249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katouzian I; Jafari SM J Control Release 2019, 303, 302–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heller I; Janssens AM; Mannik J; Minot ED; Lemay SG; Dekker C Nano Lett 2008, 8, (2), 591–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heller I; Kong J; Williams KA; Dekker C; Lemay SG J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128, (22), 7353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leroy BJ; Lemay SG; Kong J; Dekker C Nature 2004, 432, (7015), 371–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JW; Galanzha EI; Shashkov EV; Moon HM; Zharov VP Nat Nanotechnol 2009, 4, (10), 688–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel DK; Dutta SD; Ganguly K; Kim JW; Lim KT J Biomed Mater Res A 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L; Yang C; Zhao K; Li J; Wu HC Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao J; Wang L; Kang SG; Zhao L; Ji M; Chen C; Zhao Y; Zhou R; Li J Nanoscale 2014, 6, (21), 12828–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tunuguntla RH; Henley RY; Yao YC; Pham TA; Wanunu M; Noy A Science 2017, 357, (6353), 792–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sedman VL; Allen S; Chen X; Roberts CJ; Tendler SJ Langmuir 2009, 25, (13), 7256–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castillo J; Tanzi S; Dimaki M; Svendsen W Electrophoresis 2008, 29, (24), 5026–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burazerovic S; Gradinaru J; Pierron J; Ward TR Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2007, 46, (29), 5510–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballister ER; Lai AH; Zuckermann RN; Cheng Y; Mougous JD Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, (10), 3733–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spirito D; Shamsi J; Imran M; Akkermann QA; Manna L; Krahne R Nanotechnology 2020, 31, (18), 185304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y; Yang P; Wang N; Chen Z; Su D; Zhou ZH; Rao Z; Wang X Protein Cell 2020, 11, (5), 339–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz C; De Donatis GM; Zhang H; Fang H; Guo P Virology 2013, 443, (1), 28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Z; Khisamutdinov E; Schwartz C; Guo P ACS Nano 2013, 7, (5), 4082–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo P; Zhao Z; Haak J; Wang S; Wu D; Meng B; Weitao T Biotechnol Adv 2014, 32, (4), 853–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De-Donatis GM; Zhao Z; Wang S; Huang LP; Schwartz C; Tsodikov OV; Zhang H; Haque F; Guo P Cell Biosci 2014, 4, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo YY; Blocker F; Xiao F; Guo P J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2005, 5, (6), 856–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jing P; Haque F; Shu D; Montemagno C; Guo P Nano Lett 2010, 10, (9), 3620–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang S; Ji Z; Yan E; Haque F; Guo P Virology 2017, 500, 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahmood N; Mihalcioiu C; Rabbani SA Front Oncol 2018, 8, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geng J; Fang H; Haque F; Zhang L; Guo P Biomaterials 2011, 32, (32), 8234–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haque F; Wang S; Stites C; Chen L; Wang C; Guo P Biomaterials 2015, 53, 744–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heerema SJ; Vicarelli L; Pud S; Schouten RN; Zandbergen HW; Dekker C ACS Nano 2018, 12, (3), 2623–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clarke J; Wu HC; Jayasinghe L; Patel A; Reid S; Bayley H Nat Nanotechnol 2009, 4, (4), 265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venkatesan BM; Bashir R Nat Nanotechnol 2011, 6, (10), 615–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singer A; Wanunu M; Morrison W; Kuhn H; Frank-Kamenetskii M; Meller A Nano Lett 2010, 10, (2), 738–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haque F; Lunn J; Fang H; Smithrud D; Guo P ACS Nano 2012, 6, (4), 3251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ji Z; Kang X; Wang S; Guo P Biomaterials 2018, 182, 227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ji Z; Wang S; Zhao Z; Zhou Z; Haque F; Guo P Small 2016, 12, (33), 4572–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S; Zhou Z; Zhao Z; Zhang H; Haque F; Guo P Biomaterials 2017, 126, 10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chaban Y, Lurz R, Brasilès S, Cornilleau C, Karreman M, Zinn-Justin S, Tavares P, Orlova, Proc Natl Acad Sci, 2015, 7009–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang S, Zhao Z, Haque F, Guo P., Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;51:80–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S, Ji Z, Yan E, Haque F, Guo P. Virology. 2017;500:285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao F, Sun J, Coban O, Schoen P, Wang JC, Cheng RH, & Guo P 2009. ACS nano, 3(1), 100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.