Abstract

Background

Glaucoma is a neurodegenerative ophthalmic disorder and is considered among the leading causes of irreversible blindness. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common type of glaucoma that affects after 30 years of life, progressing slowly, and manifests as decreased visual acuity leading to blindness if not treated. POAG is genetically heterogeneous, inherited most commonly in autosomal dominant mode. Several genes have been reported for POAG with myocilin (Myoc) being most common. The present study has been conducted to screen 25 POAG families with 2 or more affected members for their association with Myoc and CYP1B1 (the most common gene in primary congenital glaucoma).

Methods

After approval from Institutional Ethical Review Committee (ERC), 25 POAG families were enrolled from the southern province (Sindh) of Pakistan. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals and diagnosis was confirmed by consultant ophthalmologists using various instruments and means. Venous blood was obtained from affected individuals and their normal family members for DNA extraction and subsequent analysis.

Results

All samples were initially screened for the Myoc gene followed by CYP1B1. Screening for Myoc revealed one previously reported variant c.144G>T in POAG-06 whereas screening for CYP1B1 in all 25 families showed a novel variant c.649G>A in POAG-02. The pathogenicity of the novel variant was confirmed using various bioinformatics tools.

Conclusion

This is the first report of any POAG family found associated with a novel variant in CYP1B1 from the southern province of Pakistan whereas one family found associated with a reported variant in Myoc. The remaining 23 POAG families did not found to be associated with either Myoc or CYP1B1 indicating genetic heterogeneity of the population in this part of the world.

Keywords: Glaucoma, POAG, Myocilin, CYP1B1

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a progressive neurodegenerative ocular disease that accounts for the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide (Tham et al., 2015). At the global level, it is reported to affect 65–70 million people’s qualities of life with an expectation to get worsen over time (Thau et al., 2018). Among subtypes of Glaucoma, the primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form and approximately 3.54% prevalence in the age spectrum of (40–80 years) was observed (Kreft et al., 2019). POAG manifests itself by slowly degenerating retinal ganglion cells, optic nerve head neural tissue deficit with an ultimate loss of visual field. Intraocular pressure (IOP) is considered a substantial aspect of POAG patho-physiology, especially the loss of optic nerve (Evangelho et al., 2019). A rare but more severe and aggressive form of POAG termed juvenile open-angle glaucoma (JOAG) has an early age onset (3–40 years) and encompasses 4% of cases of childhood glaucoma (Kwun et al., 2016). In Pakistan glaucoma is the 3rd leading cause of blindness in populations with different ethnic backgrounds (Mahar and Shahzad, 2008).

POAG is a genetically heterogeneous disorder with miscellaneous inheritance. POAG’s complex and variable phenotype intimate’s multifactorial etiology, for instance, multifaceted genetic network (one or more genes) along with environmental influences. There are several genetic loci reported to be directly involved in disease onset or considered risk elements found by Genome-wide association studies (Porter et al., 2011, Kader et al., 2017). MYOC (myocilin) is the very first gene identified to cause POAG in an autosomal dominant fashion. Itis involved in both juvenile (8–30%) and adult (2–4%) onset-POAG. MYOC is found to ubiquitously express in both ocular and non-ocular tissues e.g. skeletal muscles, brain, heart, retina, trabecular meshwork (TM), and ciliary body in the eye, and play a pivotal role in maintaining intraocular pressure (eye). Out of three exons, its 3rd exon is reported to robustly hold a burden of pathogenic variants. This exon comprised olfactomedin domain which is important for carrying out intracellular trafficking, neurogenesis, cell–cell adhesion, and neural crest formation like functions (Jain et al., 2017, Marques et al., 2018). An impaired myocilin protein may impact TM function and possibly lead towards high IOP (Wang et al., 2019). To date, there are more than 150 pathogenic variants in MYOC reported being responsible for glaucoma according to human genome mutation database (HGMD). MYOC may share a common path with CYP1B1(modifying MYOC function), another well-known gene reported causing glaucoma (Vincent et al., 2002).

In the eye, CYP1B1 (cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1) is found to express in endoplasmic reticula of ciliary body and iris, helps with both Exo and endogenous substrates metabolism. An aberrant CYP1B1 protein function alters IOP by impacting crucial substrates metabolism in ciliary epithelium, a prime source of aqueous humor. It might affect aqueous humordrainage indirectly by disrupting proper TM development (Micheal et al., 2015). To date, 277 pathogenic variants in CYP1B1 are reported to cause primary congenital glaucoma (DATABASE).

In the current study, we aimed to portray the role of the POAG genes spectrum in Pakistan. For so, we have screened 25 Pakistani consanguineous families affected with glaucoma. MYOC and CYP1B1 exons screening identified one known [p.(Gln48His)] and one novel [p.(Asp217Asn)] missense variants in two families POAG06 and POAG02, respectively.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Ethical approval and clinical examination

The current study was approved by the ERC of Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences, Jamshoro. The study was performed following the principles of Helsinki. Twenty-five Pakistani families (Sindh province) with at least two POAG affected were recruited for the study. Participated subjects underwent an extensive clinical examination by an ophthalmologist. Goldmann applanation tonometry was used to assess IOP and Goldmann gonioscope was used to evaluate iridocorneal angles (anterior chamber angles). Visual acuity test was performed along with fundus examination with + 90 Diopter lens by using slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Peripheral blood samples were obtained from patients after written informed consents. DNA of all affected and normal siblings were extracted by standard previously optimized protocol (Grimberg et al., 1989).

2.2. Mutation screening and bioinformatics analysis

Before CYP1B1exons screening, all enrolled families were excluded for any pathogenic variants in MYOC, the gene responsible for the majority of POAG cases worldwide. The intronic and exonic boundaries of the CYP1B1 gene were amplified and directly sequenced as described previously (Sheikh et al., 2014). Sanger sequencing data were analyzed by Chromas v 1.45 software. Pathogenicity predictions for identified variants were obtained by an online analysis tool called Varsome (https://varsome.com/). Protter was used to visualize protein sequence and topology (https://wlab.ethz.ch/protter/start/). Clustal omega was used to obtain amino acid conservation alignment. Phyre2 was used to generate CYP1B1 and MYOC proteins 3D structures. Chimera was used to visualizing obtained structures. Ramachandran and hydropathy plots were generated by Molprobity (https://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/) and (https://www.tcdb.org/progs/?tool=hy dro) respectively.

3. Results

MYOC gene exons screening in probands from 25 Pakistani consanguineous families revealed one known nonsynonymous variant [p.(Gln48His)] in one family POAG-06. This family was ascertained from the Sindh province of Pakistan. Detailed family history showed thirteen individuals in three generations to be affected with glaucoma, of which two participated in the study. Both affected underwent a detailed clinical examination by an ophthalmologist and were diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical findings and pathogenicity predictions for variants found in Pakistani POAG families.

| Family | POAG02 | POAG06 | |||||||||

| Gene | CYP1B1 | MYOC | |||||||||

| Variant | c.649G>A, p.(Asp217Asn) | c.144G>T, p.(Gln48His) | |||||||||

| gnomAD | 0.0008760 | 0 | |||||||||

| ACMG | PM2, PP2, BP4 | PS1, PM2, PP2, BP4 | |||||||||

| CADD | |||||||||||

| DANN | 0.99 | 0.96 | |||||||||

| FATHMM-MKL | Damaging | Damaging | |||||||||

| Mutation Taster | Disease-causing | Polymorphism | |||||||||

| Mutation Assessor | Low | Low | |||||||||

| SIFT4G | Tolerated | Damaging | |||||||||

| GERP | 4.4 | 5.7 | |||||||||

| Reference | This study | (Sripriya et al., 2004),(Gobeil et al., 2006) | |||||||||

| Subject | IV:01 | IV:03 | IV:04 | IV:07 | IV:08 | IV:09 | V:02 | IV:02 | IV:03 | IV:06 | |

| Gender | M | M | M | F | M | M | M | M | F | F | |

| Age (yrs) | 65 | 70 | 40 | 60 | 88 | 60 | 49 | 73 | 79 | 75 | |

| Age of onset | 39 | 42 | 38 | 45 | 49 | 43 | 40 | 41 | 50 | 47 | |

| Ethnicity | Sindhi | Sindhi | |||||||||

| Status | Affect ed | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | |

| Visual acuity | Right | 6/60 | 6/24 | 6/9 | 6/12 | NPL | CF | 6/18 | 6/36 | NPL | 2/60 |

| Left | 6/36 | PL | 6/9P | 6/60 | NPL | 6/60 | 6/12 | 6/24 | 6/60 | 3/60 | |

| IOP mmHg | Right | 20 | 14 | 12 | 18 | 25 | 20 | 14 | 12 | 25 | 14 |

| Left | 16 | 26 | 14 | 22 | 28 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 20 | |

| C/D | Right | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Left | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| Gonioscopy | OA | OA | OA | OA | OA | OA | OA | OA | OA | OA | |

| Trabeculectomy surgery | Left | Right | Bilateral | Right | NIL | Left | Bilateral | Bilateral | Left | Bilateral | |

PL: Perception of light, IOP: Intraocular pressure, C/D ratio: Cup/Disc ratio, NPL: No Perception of Light, CF: Counting Fingers, OA: Open-Angle.

PS1: Same amino acid change as a previously established pathogenic variant regardless of nucleotide change.

PM2: Not found in controls or extremely low frequency in 1000 Genomes Project.

PP2: Low rate of benign missense variation and common mechanism of disease.

BP4: Multiple lines showed no impact on gene and gene products.

One affected (IV:02) has an early onset of disease (41 years old) versus his sibs. Despite different age-onset, they all have severe vision loss, particularly IV:03. Gonioscopy suggests opened angle for the anterior chamber. IOP in IV:02 was observed to be 28/32 mmHg before trabeculectomy with the cup to disc ratio of 0.8/0.7 (Table 1).After bilateral trabeculectomy, IOP was controlled to 12 mm Hg (OD) and 18 mmHg (OS). Bilateral vision loss in IV: 03 possibly reflect a late diagnosis to treat. The IV: 03 lost visual acuity in the right eye (NPL) and left eye acuity was normal6/60. The fundoscopy revealed that the C/D ratio was 1.0/0.9 and gonioscopy confirmed openangle of the anterior chamber. She underwent a left eye trabeculectomy with a consequent drop of IOP to16 mmHg. Similarly, late diagnosis in IV: 06 results in visual acuity 2/60 and 3/60 (OD and OS) respectively. Fundus examination revealed a C/D ratio of 0.9/0.9 and IOP was controlled to 14/20 mmHg after bilateral trabeculectomy.

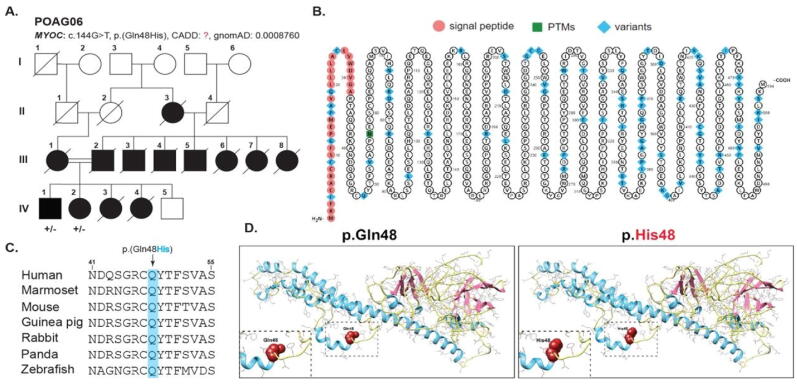

By known gene screening, we have identified a known missense variant [p. (Gln48His)] in MYOC which was segregating in POAG06 in an autosomal dominant manner (Fig. 1A). This p. (Gln48His) substitution is predicted to be damaging by multiple Pathogenicity prediction programs e.g. FATHMM-MKL, SIFT4G. We did not find this variant in the allele frequency database called gnomAD (Table 1). p.Gln48 is also found to be highly conserved across several vertebrate species (Fig. 1C). MYOC protein topology with known variants (highlighted in blue) is shown in Fig. 1B; however, the current study variant is marked in red. As per molecular modeling prediction, p.Gln48 replacement with histidine which is comparatively big than wild type residue results in introducing structural changes that might lead to collision (Fig. 1D). MYOC protein confines in TM extracellular matrix and hydropathy plot analysis showed hydrophobicity score to be −0.744 for wild type versus mutant protein −0.711. Ramachandran plots analysis revealed 73 and 87% of wild-type protein residues to lie in favored and allowed regions respectively with 64 outliers. However, MYOC mutant protein 72 and 85% residues lie in favored and allowed regions with 75 outliers (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

A- Family pedigree of POAG06 showing and affected individuals (filled squares and circles). Females are represented by circles and males by squares. B- Shows Myoc protein topology with known variants (highlighted in blue). C- Clustal Omega multiple alignment sequence showing conservation of glutamine in various species. D- Molecular modeling prediction of glutamine replacement with histidine showing bigger size than wild-type residue.

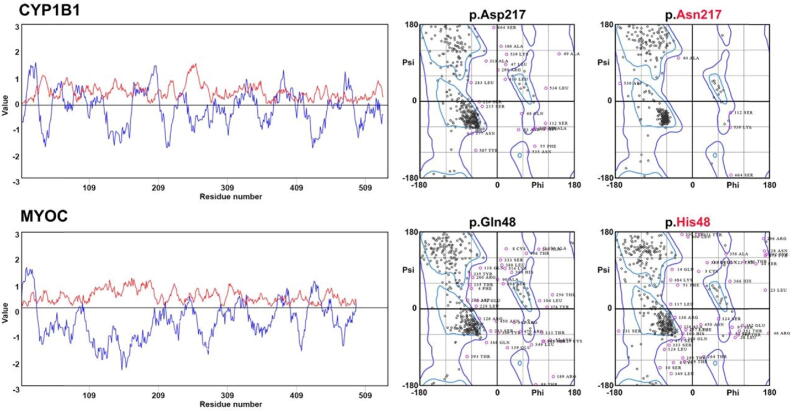

Fig. 3.

Hydrophobicity plot showed CYP1B1 protein to contain hydrophobic amino terminal with −2.122 score. Ramachandran plots calculated protein’s backbone bond angles, interestingly 93 and 98% of CYP1B1 mutant protein residues were found in favored and allowed regions respectively versus wild type protein (77 and 91%). MYOC protein’shydropathy plot analysis showed hydrophobicity score to be −0.744 for wild type versus mutant protein −0.711. Ramachandran plots analysis revealed 73 and 87% of wild type protein residues to lie in favored and allowed regions respectively with 64 outliers. However, MYOC mutant protein 72 and 85% residues lie in favored and allowed regions with 75 outliers.

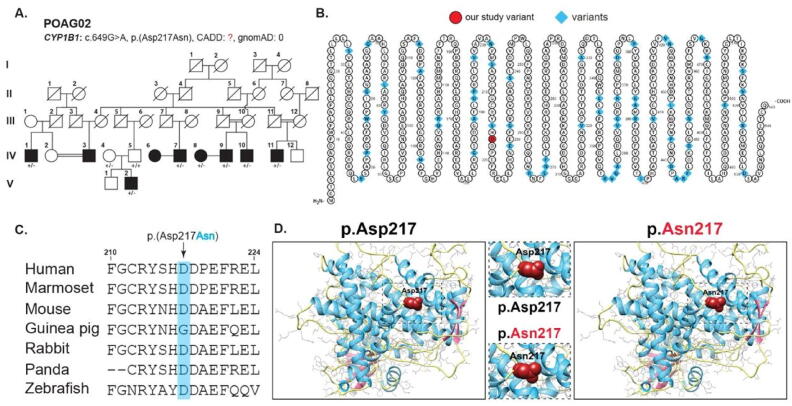

CYP1B1 exons screening in families revealed a novel missense variant [p.(Asp217Asn)] in one family POAG02 segregating in autosomal dominant pattern (Fig. 2A). The affected individuals were diagnosed with open-angle (OP) glaucoma and clinically assessed for visual atrophy. There were nine affected in the family, of which seven participated in the study after written informed consents. This family POAG02 was also enrolled from the Sindh province of Pakistan. Detailed clinical findings showed cup to disc ratio as high as 1.0 (Table 1). We found total cupping in the affected individual (IV: 8) who did not undergo trabeculectomy, however, all other affected had variable cupping consistent towards corresponding reduced visual acuity (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

A- Family pedigree of POAG02 showing and affected individuals (filled squares and circles). Females are represented by circles and males by squares. B- Shows CYP1B1 protein topology with known variants (highlighted in blue). C- Clustal Omega multiple alignment sequence showing conservation of aspartate in various species. D- Molecular modeling prediction of aspartic acid replacement with asparagine resulting in loss of normal charge and interactions among neighboring amino acids.

There was a range of visual field loss in affected varying from 6/60 to counting fingers (IV: 09). All patients had normal or near-normal IOP as they endured trabeculectomy shortly after being diagnosed with POAG apart from (IV:08).

The pathogenic CYP1B1 identified a novel variant [p. (Asp217Asn)] was confirmed by using different pathogenicity prediction programs with an allele frequency of 0.0008760 in gnomAD (Table 1). p.Asp217 is found to be highly conserved across several species (Fig. 2C). CYP1B1 protein topology is shown in Fig. 2B. p.Asp217 is located in the main protein domain called cytochrome p450 which carries oxidative degradation of different compounds. Molecular predictions suggest wild-type residue p.Asp217 to be different in charge than mutant p.Asn217 which might result in the loss of interactions with other residues or same charged ligands (Fig. 2D). The hydrophobicity plot showed CYP1B1 protein to contain a hydrophobic amino-terminal with a −2.122 score (Fig. 3). We did not find any impact of missense mutation on the overall hydrophobicity score. Ramachandran plots calculated protein’s backbone bond angles, interestingly 93 and 98% of CYP1B1 mutant protein residues were found in favored and allowed regions respectively versus wild type protein (77 and 91%, Fig. 3).

4. Discussion

Glaucoma is a chronic neurodegenerative ophthalmological disorder that manifests as raised intraocular pressure (IOP) leading to optic neuronal degeneration and atrophy. If not treated it could lead to permanent blindness. Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide. Although raised IOP has been implicated in its pathogenesis by almost all studies its exact etiology has so far been remained unclear. Molecular genetic studies have pointed towards some genes in association with glaucoma and such identification of the genes has provided some understanding as far as the pathogenesis of inherited forms of glaucoma is concerned (Fingert, 2011).

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most prevalent form of glaucoma among all glaucoma patients. Most of the genetic studies have constituted the correlation of different genes with the POAG1. (M Gemenetzi).

The present study was carried out to ascertain the association of CYP1B1 and MYOC with 25 families’ suffering from primary open-angle glaucoma enrolled from the southern province of Pakistan. All families had two or more individuals affected with POAG. About CYP1B1, a heterozygous variant was found to be segregating in all nine affected members of family POAG02. No other family suffering from POAG was found to be associated with CYP1B1 on direct sequencing. The prevalence of CYP1B1 in our group of families was thus found to be 4% (1/25 families). It is noteworthy that, heterozygous CYP1B1 variants cause POAG in an autosomal dominant way, whereas in the case of familial PCG with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, heterozygous individuals are phenotypically normal possibly due to recessive mode of inheritance although compound heterozygous mutations in CYP1B1 have also been reported (Sheikh et al., 2014, Souzeau et al., 2015).

A study conducted on 40 families enrolled from Pakistan and affected with POAG has reported the prevalence of CYP1B1 among 4 families (10%), however, its prevalence among non-familial POAG patients was found to be 3%. It is however important to note that this previous study was carried out in the Punjab province of the country which is ethnically different from Sindhi speaking population of the country (Micheal et al., 2015). The results of our study about CYP1B1 prevalence in POAG families however could be compared to an Indian study which finds the prevalence of CYP1B1 as 2% among 200 enrolled families (4/200) (Melki et al., 2004).

Inherited forms of glaucoma are extremely heterogeneous with variable penetrance across different ethnicities. One such study has demonstrated interfamilial variation in phenotype in association with the same CYP1B1 mutations exhibiting congenital glaucoma and POAG (Melki et al., 2004). Another study on Iranian patients showed the presence of homozygous CYP1B1 variants in individuals with POAG and JOAG (Suri et al., 2008). It is important to mention here that we have some studies that have shown the association of CYP1B1 with an early-onset form of POAG termed Juvenile open-angle glaucoma (JOAG) (Vincent et al., 2002). In our study, however, all affected individuals had glaucoma onset after 35 years of their life. Furthermore, detailed and careful family history followed by an ophthalmological examination by our panel of consultants did not reveal any sign of congenital glaucoma.

Keeping in view the association of CYP1B1 with various types of glaucoma and its expression in variable phenotypes, it has been suggested that some genetic or epigenetic factors might be responsible for the variable expression and pathogenicity of CYP1B1 variants.

Our cohort of 25 families with POAG was also screened for its association with myocilin (Myoc), the most common gene found in association with inherited forms of POAG. Of 25 families, only one family POAG-06 was found to be segregating with a reported variant (c.144G>T; pGln48His) in myocilin. In this family (POAG-06), thirteen affected and nine normal individuals were present in three successive generations. All patients were clinically examined and found to have characteristic features of POAG.

This variant was first reported by (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2002) in three POAG-affected sporadic patients of Indian origin. The age of all three patients ranged between 20 and 70 years of age.

Likewise, another study carried out in 2003 on 100 sporadic POAG patients also reported the same variant on direct sequencing (Sripriya et al., 2004). Both Mukhopadhyay et al. (2002) and Sripriya et al. (2004) reported this mutation in the six sporadic cases whereas, in this study, it has been found among thirteen affected familial patients of the same family. This finding is therefore significant in this regard as it is being reported for the first time in familial cases from Sindhi speaking population of Pakistan. Bioinformatics tools have demonstrated the presence of this variant within the N-terminus of MYOC protein which is important for initiation of oligomerization as well as other extracellular interactions by its leucin zippers present in two coiled-coil domains. So, the mutation [p. (Gln48His)] found in this coiled region may impact its normal function and affect IOP (Wang et al., 2019).

Our study is important in the sense that this is for the first time that any CYP1B1 associated POAG family is being reported from Sindh province of Pakistan with identification of a novel variant in a heterozygous fashion. The same cohort of families on sequencing revealed a reported variant in the myocilin gene as well. The remaining 23 families of POAG did not show their association with either CYP1B1 or Myoc which clearly shows the genetic heterogeneity of different ethnic populations within this part of the World. These families will be further investigated through Exome or Genome sequencing to look for any variant within regulatory sequences of the genes. Screening of the population for reported genes for various forms of inherited glaucoma is therefore important in terms of early diagnosis and further management to provide a better and independent life to the affected individuals. Furthermore, identification of the variants in association with glaucoma will help to understand the pathophysiology of the disorder using bioinformatics tools or animal studies

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their heartfelt gratitude to their alma mater, The Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences. Jamshoro, Pakistan.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Yaqoob Shahani, Email: muhammad.yaqoob@lumhs.edu.pk.

Samreen Memon, Email: samreen.memon@lumhs.edu.pk.

Shakeel Ahmed Sheikh, Email: shakeel.shaikh@lumhs.edu.pk.

Shazia Begum Shahani, Email: drshaziashahani@pumhs.edu.pk.

Ikram din Ujjan, Email: ikramujjan@lumhs.edu.pk.

Ashok Kumar Narsani, Email: Ashok.narsani@lumhs.edu.pk.

Ali Muhammad Waryah, Email: aliwaryah@lumhs.edu.pk.

References

- DATABASE, H.G.M. Human Gene Mutation Database.

- Evangelho K., Mogilevskaya M., Losada-Barragan M., Vargas-Sanchez J.K. Pathophysiology of primary open-angle glaucoma from a neuroinflammatory and neurotoxicity perspective: a review of the literature. Int. Ophthalmol. 2019;39:259–271. doi: 10.1007/s10792-017-0795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingert J.H. Primary open-angle glaucoma genes. Eye. 2011;25:587–595. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobeil S., Letartre L., Raymond V. Functional analysis of the glaucoma-causing TIGR/myocilin protein: integrity of amino-terminal coiled-coil regions and olfactomedin homology domain is essential for extracellular adhesion and secretion. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;82(6):1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimberg J., Nawoschik S., Belluscio L., McKee R., Turck A., Eisenberg A. A simple and efficient non-organic procedure for the isolation of genomic DNA from blood. Nucl. Acids Res. 1989;17(20):8390. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Zode G., Kasetti R.B., Ran F.A., Yan W., Sharma T.P., Bugge K., Searby C.C., Fingert J.H., Zhang F., Clark A.F., Sheffield V.C. CRISPR-Cas9-based treatment of myocilin-associated glaucoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2017;114:11199–11204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706193114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kader M.A., Namburi P., Ramugade S., Ramakrishnan R., Krishnadas S.R., Roos B.R., Periasamy S., Robin A.L., Fingert J.H. Clinical and genetic characterization of a large primary open angle glaucoma pedigree. Ophthalmic Genet. 2017;38:222–225. doi: 10.1080/13816810.2016.1193883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft D., Doblhammer G., Guthoff R.F., Frech S. Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors of primary open-angle glaucoma - a cohort study based on longitudinal data from a German public health insurance. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:851. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6935-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwun Y., Lee E.J., Han J.C., Kee C. Clinical Characteristics of Juvenile-onset Open Angle Glaucoma. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2016;30:127–133. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2016.30.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahar P.S., Shahzad M.A. Glaucoma Burden in a Public Sector Hospital. Pak J. Ophthalmol. 2008;24(3):112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Marques A.M., Ananina G., Costa V.P., de Vasconcellos J.P.C., de Melo M.B. Estimating the age of the p.Cys433Arg variant in the MYOC gene in patients with primary openangle glaucoma. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0207409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melki R., Colomb E., Lefort N., Brezin A.P., Garchon H.J. CYP1B1 mutations in French patients with early-onset primary open-angle glaucoma. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:647–651. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheal S., Ayub H., Zafar S.N., Bakker B., Ali M., Akhtar F., Islam F., Khan M.I., Qamar R., den Hollander A.I. Identification of novel CYP1B1 gene mutations in patients with primary congenital and primary open-angle glaucoma. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2015;43:31–39. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, A., Acharya, M., Mukherjee, S., Ray, J., Choudhury, S., Khan, M., Ray, K., 2002. Mutations in MYOC gene of Indian primary open angle glaucoma patients. [PubMed]

- Porter L.F., Urquhart J.E., O'Donoghue E., Spencer A.F., Wade E.M., Manson F.D., Black G.C. Identification of a novel locus for autosomal dominant primary open angle glaucoma on 4q35.1-q35.2. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:7859–7865. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh S.A., Waryah A.M., Narsani A.K., Shaikh H., Gilal I.A., Shah K., Qasim M., Memon A.I., Kewalramani P., Shaikh N. Mutational spectrum of the CYP1B1 gene in Pakistani patients with primary congenital glaucoma: novel variants and genotype-phenotype correlations. Mol. Vis. 2014;20:991–1001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souzeau E., Hayes M., Zhou T., Siggs O.M., Ridge B., Awadalla M.S., Smith J.E., Ruddle J.B., Elder J.E., Mackey D.A., Hewitt A.W., Healey P.R., Goldberg I., Morgan W.H., Landers J., Dubowsky A., Burdon K.P., Craig J.E. Occurrence of CYP1B1 Mutations in Juvenile Open-Angle Glaucoma With Advanced Visual Field Loss. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:826–833. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripriya S., Uthra S., Sangeetha R., George R.J., Hemamalini A., Paul P.G., Amali J., Vijaya L., Kumaramanickavel G. Low frequency of myocilin mutations in Indian primary open-angle glaucoma patients. Clin. Genet. 2004;65:333–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri F., Kalhor R., Zargar S.J., Nilforooshan N., Yazdani S., Nezari H., Paylakhi S.H., Narooie-Nejhad M., Bayat B., Sedaghati T., Ahmadian A., Elahi E. Screening of common CYP1B1 mutations in Iranian POAG patients using a microarray-based PrASE protocol. Mol. Vis. 2008;14:2349–2356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham Y.C., Liao J., Vithana E.N., Khor C.C., Teo Y.Y., Tai E.S., Wong T.Y., Aung T., Cheng C.Y., International Glaucoma Genetics, C. Aggregate Effects of Intraocular Pressure and Cup-to-Disc Ratio Genetic Variants on Glaucoma in a Multiethnic Asian Population. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thau A.J., Rohn M.C.H., Biron M.E., Rahmatnejad K., Mayro E.L., Gentile P.M., Waisbourd M., Zhan T., Hark L.A. Depression and quality of life in a communitybased glaucoma-screening project. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2018;53:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A.L., Billingsley G., Buys Y., Levin A.V., Priston M., Trope G., Williams-Lyn D., Heon E. Digenic inheritance of early-onset glaucoma: CYP1B1, a potential modifier gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:448–460. doi: 10.1086/338709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Li M., Zhang Z., Xue H., Chen X., Ji Y. Physiological function of myocilin and its role in the pathogenesis of glaucoma in the trabecular meshwork (Review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019;43:671–681. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]