Abstract

Background

Myocardial fibrosis is a common pathophysiological process involved in many cardiovascular diseases. However, limited prior studies suggested no association between focal myocardial fibrosis detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and disease severity in Eisenmenger syndrome (ES). This study aimed to explore potential associations between myocardial fibrosis evaluated by the CMR LGE and T1 mapping and risk stratification profiles including exercise tolerance, serum biomarkers, hemodynamics, and right ventricular (RV) function in these patients.

Methods

Forty-five adults with ES and 30 healthy subjects were included. All subjects underwent a contrast-enhanced 3T CMR. Focal replacement fibrosis was visualized on LGE images. The locations of LGE were recorded. After excluding LGE in ventricular insertion point (VIP), ES patients were divided into myocardial LGE-positive (LGE+) and LGE-negative (LGE−) subgroups. Regions of interest in the septal myocardium were manually contoured in the T1 mapping images to determine the diffuse myocardial fibrosis. The relationships between myocardial fibrosis and 6-min walk test (6MWT), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP), hematocrit, mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP), pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI), RV/left ventricular end-systolic volume (RV/LV ESV), RV ejection fraction (RVEF), and risk stratification were analyzed.

Results

Myocardial LGE (excluding VIP) was common in ES (16/45, 35.6%), and often located in the septum (12/45, 26.7%). The clinical characteristics, hemodynamics, CMR morphology and function, and extracellular volume fraction (ECV) were similar in the LGE+ and LGE− groups (all P > 0.05). ECV was significantly higher in ES patients (28.6 ± 5.9% vs. 25.6 ± 2.2%, P < 0.05) and those with LGE− ES (28.3 ± 5.9% vs. 25.6 ± 2.2%, P < 0.05) than healthy controls. We found significant correlations between ECV and log NT-pro BNP, hematocrit, mPAP, PVRI, RV/LV ESV, and RVEF (all P < 0.05), and correlations trends between ECV and 6MWT (P = 0.06) in ES patients. An ECV threshold of 29.0% performed well in differentiating patients with high-risk ES from those with intermediate or low risk (area under curve 0.857, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Myocardial fibrosis is a common feature of ES. ECV may serve as an important imaging marker for ES disease severity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12968-022-00880-2.

Keywords: Eisenmenger syndrome, Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, Myocardial fibrosis, T1 mapping, Extracellular volume

Background

As the extreme end of the uncorrected congenital heart disease-related pulmonary artery hypertension spectrum, Eisenmenger syndrome (ES) is characterized by cyanosis, secondary erythrocytosis, and multi-organ disorder and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Ventricular dysfunction is one of the risk indicators for poor prognosis; nonetheless, the related mechanisms were not well defined [2–4]. Myocardial fibrosis is a common pathophysiological process involved in many cardiovascular diseases. The chronic cyanosis in ES could trigger myofibroblast activity by various signaling pathways, leading to myocardial fibrosis [5–7]. A pathological autopsy study has demonstrated the existence of ventricular myocardial fibrosis in ES [8]. However, the clinical relevance of myocardial fibrosis in ES patients has not been clarified.

Myocardial fibrosis includes focal replacement and diffuse interstitial fibrosis that could be detected, respectively, by the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and T1 mapping techniques of cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) [9–11]. Broberg et al. suggested that LGE was prevalent in ES yet not correlated with disease severity, ventricular remodeling, or survival [12]. Several studies suggested that diffuse myocardial fibrosis was present in pulmonary hypertension (PH) [13–18]. Furthermore, our recent study suggested that shunt location was significant for changes in diffuse myocardial fibrosis in ES patients [19]. However, the clinical significance of myocardial fibrosis evaluated by CMR LGE and T1 mapping in ES patients remains largely unexplored. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate potential associations between myocardial fibrosis evaluated by the CMR LGE and T1 and risk stratification profiles including clinical severity, pulmonary artery hemodynamics, and right ventricular (RV) function in ES patients.

Methods

Study population

This prospective observational study was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (ChiCTR1800019314). From January 2013 to December 2019, consecutive adult patients in our hospital with a definite diagnosis of ES were prospectively enrolled. ES diagnosis was established according to the following criteria: (1) known intra-cardiac or extra-cardiac non-restrictive congenital defect at the atrial, ventricular, or arterial level (isolated or a combination of defects); (2) reversed or bidirectional shunt resulting in hypoxemia (cutaneous oxygen saturation < 92% at rest or < 87% with exercise [20–22]); (3) hemodynamic measurements of resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥ 25 mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) ≤ 15 mmHg, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) > 3 Wood units. Patients with complex congenital heart disease types (e.g., transposition of the great arteries, double-outlet RV, univentricular heart) or with a relatively small defect (atrial septal defect (ASD) < 2.0 cm or ventricular septal defect (VSD) < 1.0 cm) [23]. Patients with a contraindications for CMR, including a history of contrast allergy, implantation of implantable cardioverter defibrillator or pacemaker, or claustrophobia were excluded.

In total, 54 patients met the clinical diagnostic criteria for adult ES and underwent CMR examination. Furtherly, we excluded 3 patients with ES and atrial fibrillation whose cine images could not analyze cine data including RV volume and RV ejection fraction (RVEF), and additionally 6 ES patients who had suboptimal T1 data quality. Ultimately, a total of 45 ES patients were included in the present study. Among them, there were 11 patients (24.4%) of simple ASD, 2 patients (4.4%) of anomalous pulmonary venous drainage (APVD) complicated with ASD, 1 patient (2.2%) of aortopulmonary window, 17 patients (37.8%) of VSD, 9 patients (20.0%) of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), 3 patients (6.7%) of combined VSD and PDA, 1 patient (2.2%) of atrioventricular septal defect, and 1 patient (2.2%) of combined ASD and PDA. With the exception for isolated extra-cardiac defects (aortopulmonary window or PDA) and pre-tricuspid shunts (ASD or APVD complicated with ASD), a total of 35 patients (77.8%) with intra-cardiac defects and 32 patients (71.1%) with post-tricuspid shunts were included in the subgroup analysis.

The study also included a control group of 30 individuals with a similar age and sex distributions to the ES group who underwent contrast-enhanced CMR examination and selected from our database of healthy volunteers [24]. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent, and the local institutional ethics committee at West China Hospital approved the study protocol (2018271).

Clinical assessment

All patients were clinically and hemodynamically stable at study enrollment. Medical history was recorded, and a physical examination was performed. All patients performed a non-encouraged 6-min walk test (6MWT), and the distance was recorded [25]. World Health Organization (WHO) functional class was evaluated for each patient. Plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) and hematocrit (Hct) levels were collected from the hospital electronic medical record system. Peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2%) at rest and the end of the 6MWT were recorded in a pre-defined form. The risk stratification profiles of the ES patients were evaluated according to the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension strategy proposed by Galie et al. [26]. Low-, intermediate-, and high-risk strata were defined by estimated 1-year mortality risks of < 5%, 5–10%, and > 10%, respectively. The specific risk strategy approach can be found in Additional file 1. The time difference between the clinical assessment and the CMR acquisitions was ≤ 7 days.

CMR protocol

CMR acquisitions were performed using a 3 T scanner (Magnetom Tim Trio or Skyra; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using a dedicated 32-channel phase array cardiac coil or a 30-channel body coil with simultaneous electrocardiographic (ECG) gating technique within 72 h after right heart catheterization (RHC) examination. Among the ES participants, 22 (48.9%) were examined by the Trio/32-channel phase array cardiac coil, and the rest by the Skyra/30-channel body coil. Cine imaging was acquired using an ECG-gated balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequence during end-expiratory breath-hold in standard short-axis cine views and 2-, 3-, and 4-chamber longitudinal views, covering both ventricles from the basal to the apical level. The specific sequence parameters were as follows: echo time (TE), 1.3 ms; repetition time (TR), 3.4 ms; temporal resolution, 35–45 ms; flip angle (FA), 50°; matrix size, 256 × 192; field-of-view (FOV), 340 × 320 mm; spatial resolution, 1.5 × 1.3 mm; slice thickness, 8 mm without gaps. Gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) was administered intravenously at 0.15 mmol/kg. Short- and long-axis LGE images were obtained using the inversion recovery turbo fast low-angle shot sequence with phase-sensitive reconstruction 10–15 min after contrast injection at slice locations identical to those acquired by cine CMR. The scanning time per slice usually ranged from 8 to 12 s, depending on the patient’s heart rate. The LGE parameters were TR, 700 ms; TE, 1.56 ms; flip angle, 20°; matrix size, 256 × 192; slice thickness, 8 mm; FOV, 340 × 320 mm; acquired and reconstructed voxel size, 1.8 × 1.4 × 8 mm.

T1 mapping images were scanned using the motion-corrected modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) sequence before and after contrast injection in three short-axis slices (basal, mid, and apical) with a fixed 5(3)3/4(1)3(1)2 scheme, respectively. Post-contrast T1 measurements were performed approximately 15 min after contrast injection. The parameters for MOLLI included non-selective inversion pulse; bSSFP single-shot readout with a 35° flip angle; minimum inversion time (TI), 110 ms; TI increment, 80 ms; TR/TE, 2.9/1.12 ms; FOV, 360 × 272 mm; matrix size, 256 × 192; acquired and reconstructed voxel size, 2.1 × 1.4 × 8 mm; slice thickness, 8 mm. LGE and T1 mapping sequences were acquired during the end-diastolic cardiac phase.

Image analysis

Cardiac volumes and mass were determined by manually drawing the end-diastole and end-systole endocardial and epicardial borders using the Qmass software (version 8.1, Medis Medical Imaging, Leiden, the Netherlands) and indexed to the body surface area following the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance post-processing guidelines [27]. Papillary muscles and trabeculations were considered part of the cavity volume and excluded from the myocardial mass. LGE images were qualitatively assessed for myocardium hyperintensity. LGE was determined when focal myocardial enhancement was visible in either short- or long-axis view by two independent observers (CG and LLW, both with three years of CMR experience) blinded to the clinical data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or through consultation with a third reviewer (YCC with over ten years of CMR experience). The location of each LGE region was recorded and classified into ventricular insertion point (VIP), septum, RV myocardium, RV trabeculae, left ventricular (LV) myocardium, or LV papillary. After excluding LGE in VIP, patients with ES were divided into myocardial LGE-positive (LGE+) and LGE-negative (LGE−) subgroups.

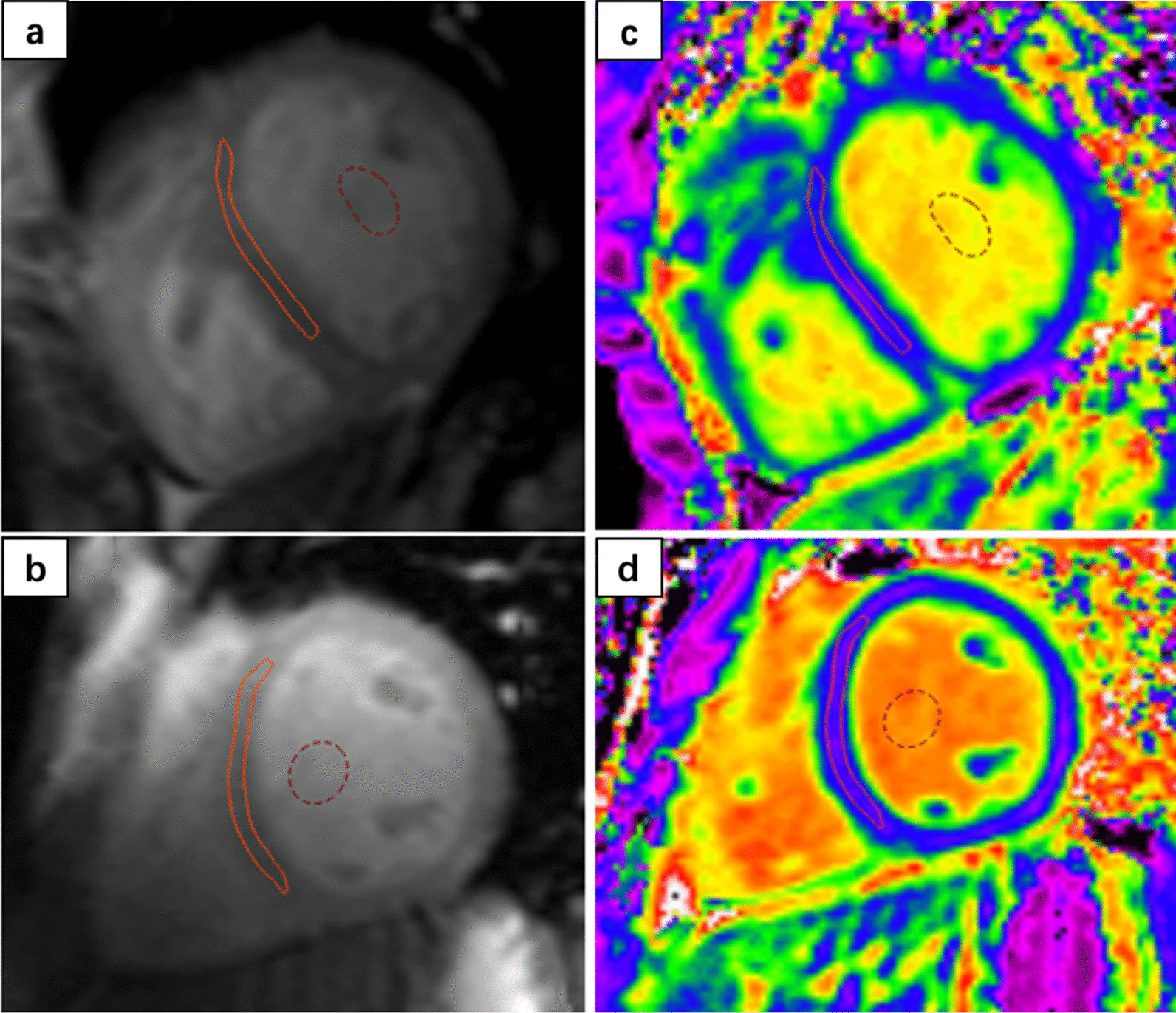

Pre- and post-T1 mapping images were analyzed on the mid-ventricular LV short-axis slice with dedicated QMap software (version 2.2.6, Medis Medical Imaging). The largest possible regions of interest (ROI) for septal myocardium sampling were manually contoured, strictly excluding any LGE (Fig. 1). Furthermore, epicardial fat, trabeculations, and near-wall blood were carefully excluded from the ROI. A T1 value of the blood pool was acquired by drawing an ROI in the LV cavity. The extracellular volume fraction (ECV) was calculated using the following formula: ECV = (1 − Hct) × ([1/T1myocardium post–1/T1 myocardium pre]/[1/T1blood post–1/T1blood pre]). The Hct was measured within 24 h of the CMR scanning.

Fig. 1.

Representative ROI contours on native T1 and extracellular volume fraction (ECV) mapping images of a normal control (a native T1 mapping; c ECV mapping) and a patient with Eisenmenger syndrome (ES) (b native T1 mapping; d ECV mapping). The orange solid contour line represents the septum. The red dotted contour represents the blood pool. ROI region of interest, ECV extracellular volume, ES Eisenmenger syndrome

Right heart catheterization

All patients underwent RHC to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the disease severity. RHC was performed routinely in free-breathing patients following a standard procedure [23]. The following invasive hemodynamic measurements were attained: mean right atrial pressure (mRAP), mPAP, PAWP, and the pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio (Qp:Qs). Cardiac output (CO) was calculated by the indirect Fick equation. PVR was calculated using the formula: PVR = (mPAP − PAWP/CO).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation if the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed normal distribution; otherwise, data are presented as the median and interquartile range. Categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage. Independent Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test compared continuous variables with normal and skewed distributions, respectively. Fisher’s exact or χ2 test compared categorical variable groups. Associations between variables were tested using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to identify the largest area under the curve (AUC) for discriminating high-risk from low- and intermediate-risk profiles in patients with ES. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 23.0, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, International Business Machines, Inc., Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) and GraphPad Prism for Macintosh, Version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). For all tests, a two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Overall, 45 ES patients (female, 32/45, 71.1%; 36.6 ± 11.1 years) and 30 healthy controls (female, 18/30, 60.0%; 38.4 ± 14.8 years) were enrolled. Patient and clinical characteristics and hemodynamic data are summarized in Table 1. Compared with healthy controls, ES patients had lower body mass index and systolic blood pressure and higher heart rate (all P < 0.05). Most ES patients were in WHO functional class II (27/45, 60.0%). Besides, we depicted in ES patients typical clinical characteristics of cyanosis and secondary erythrocytosis reflected by decreased SpO2 and increased Hct. We also found impaired hemodynamics manifested in elevated mPAP and PVR index (PVRI) and significant right-to-left or bidirectional shunts.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with ES and normal controls

| Healthy controls (n = 30) | ES patients (n = 45) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 38.4 ± 14.8 | 36.6 ± 11.1 | 0.588 |

| Female, n, % | 18 (60.0) | 32 (71.1) | 0.331 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.987 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.1 ± 2.5 | 20.2 ± 3.5 | 0.009 |

| SBP, mmHg | 119 ± 8 | 113 ± 16 | 0.031 |

| DBP, mmHg | 73 ± 5 | 70 ± 11 | 0.145 |

| HR, bpm | 76 ± 7 | 89 ± 16 | < 0.001 |

| Hct, % | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.11 | < 0.001 |

| Plt, 109/L | – | 150 ± 47 | – |

| NT-pro BNP, pg/mL | – | 460 (83—1515) | – |

| Tnt, ng/L | – | 10.9 ± 7.7 | – |

| 6MWT, m | – | 424 ± 92 | – |

| WHO class I/II/III/IV, n | – | 2/27/16/0 | – |

| SpO2, % | – | 86 ± 5 | – |

| Hemodynamic characteristics | |||

| mRAP, mmHg | – | 7 ± 4 | – |

| mPAP, mmHg | – | 68 ± 20 | – |

| PAWP, mmHg | – | 10 ± 4 | – |

| Qp:Qs | – | 1.0 ± 0.3 | – |

| PVRI, Wood units × m2 | – | 26.1 ± 14.3 | – |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | – | |

| SvO2, % | – | 61.2 ± 9.5 | – |

ES Eisenmenger syndrome, BSA body surface area, BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, Hct hematocrit, NT-pro BNP N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, 6MWT 6-min walking test, WHO World Health Organization, SpO2 peripheral arterial oxygen saturation, mRAP mean right atrial pressure, mPAP mean pulmonary artery pressure, PAWP pulmonary artery wedge pressure, Qp:Qs pulmonary to systemic flow ratio, PVRI pulmonary vascular resistance index, CI cardiac index, SvO2 mixed venous oxygen saturation

Values in bold indicate P values < 0.05

CMR morphology and function characteristics of ES and healthy controls

Significant differences in ventricular morphology and function between ES patients and healthy controls were demonstrated, including increased biventricular end-systolic volume (ESV) index (ESVI), decreased biventricular EF, decreased biventricular stroke volume index (SVI), increased LV mass index (LVMI), and increased RV ESV/LV ESV ratio (all P < 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

CMR characteristics in patients with ES and normal controls

| Healthy controls (n = 30) | ES patients (n = 45) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricle, LV | |||

| LV EDVI, mL/m2 | 78 ± 13 | 82 ± 30 | 0.512 |

| LV ESVI, mL/m2 | 29 ± 7 | 39 ± 17 | 0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 62.7 ± 4.0 | 52.9 ± 7.9 | < 0.001 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 45 ± 8 | 565 ± 18 | 0.002 |

| LV SVI, mL/m2 | 31 ± 5 | 39 ± 12 | < 0.001 |

| Right ventricle, RV | |||

| RV EDVI, mL/m2 | 73 ± 13 | 122 ± 57 | < 0.001 |

| RV ESVI, mL/m2 | 30 ± 9 | 78 ± 47 | < 0.001 |

| RVEF, % | 59 ± 7 | 36 ± 13 | < 0.001 |

| RV SVI, mL/m2 | 26 ± 4 | 41 ± 14 | < 0.001 |

| RV EDV/LV EDV | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| RV ESV/LV ESV | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Diffuse myocardial fibrosis | |||

| Native T1, ms | 1209 ± 40 | 1266 ± 76 | < 0.001 |

| ECV, % | 25.6 ± 2.2 | 28.6 ± 5.9 | 0.004 |

| LGE presence, n (%) | |||

| Anterior/inferior VIP | – | 43 (95.6%) | – |

| Any myocardium* | – | 16 (35.6%) | – |

| Septum | – | 12 (26.7%) | – |

| RV myocardium | – | 10 (22.2%) | – |

| LV myocardium | – | 3 (6.7%) | – |

| RV trabeculae | – | 3 (6.7%) | – |

| LV papillary | – | 1 (2.2%) | – |

ES Eisenmenger syndrome, CMR cardiovascular magnetic resonance, LV left ventricular, RV right ventricular, EDVI end-diastolic volume index, ESVI end-systolic volume index, EF ejection fraction, massi mass index, SVI stroke volume index, ECV extracellular volume, LGE late gadolinium enhancement, VIP ventricular insertion point

*Excluding anterior and inferior VIP

Values in bold indicate P values < 0.05

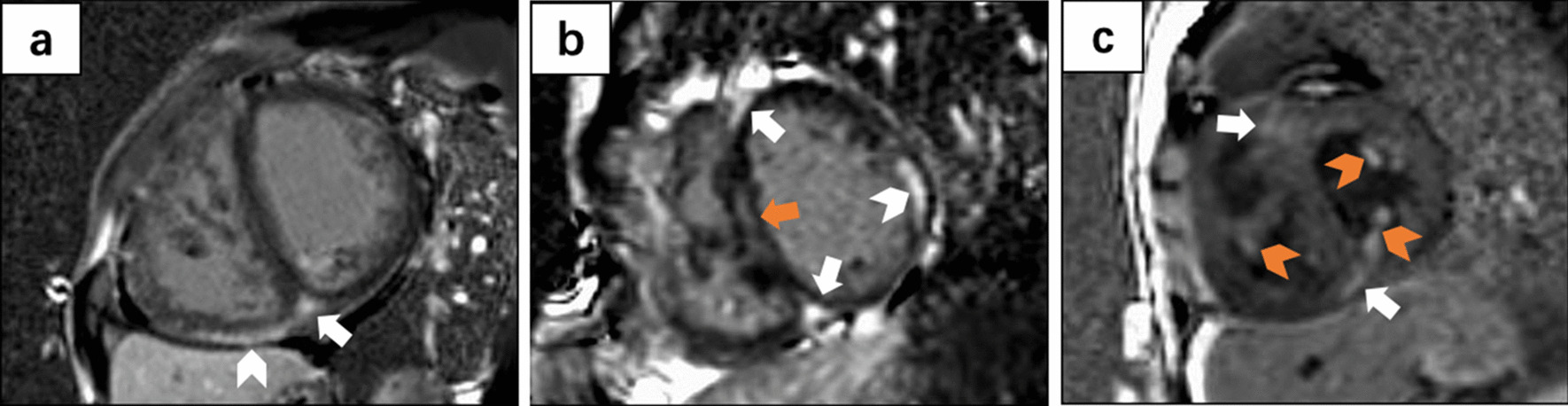

Characteristics of myocardial fibrosis in patients with ES

LGE located in anterior/inferior VIP was identified in 43 (95.6%) ES patients. Myocardial LGEs (excluding VIP) were found in 16 (35.6%) ES patients, with septal LGE in twelve (26.7%), RV myocardial LGE in ten (22.2%), LV myocardial LGE in three (6.7%), RV trabeculae LGE in three (6.7%), and LV papillary LGE in one (2.2%). Representative examples of LGE images are presented in Fig. 2. Excluding anterior/inferior VIP, the LGE+ and LGE− subgroups had similar clinical characteristics, hemodynamics, and CMR morphology and function (Additional file 2).

Fig. 2.

Representative examples of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images. a Inferior ventricular insertion points (VIP), white arrow) and right ventricular (RV) myocardium (white chevron); b Anterior/inferior VIP (white arrow), septum (orange arrow) and left ventricular (LV) myocardium (white chevron); c Anterior/inferior VIP (white arrow), LV papillary (orange chevron), and RV trabeculae (orange chevron). LGE late gadolinium enhancement, VIP ventricular insertion point, LV left ventricular, RV right ventricular

In terms of diffuse myocardial fibrosis, ES patients demonstrated higher native T1 value (1266 ± 76 vs. 1209 ± 40 ms, P < 0.001) and ECV (28.6 ± 5.9% vs. 25.6 ± 2.2%, P = 0.004) than healthy controls (Table 2). When we set the upper normal native T1 limit at 1282 ms and ECV at 29.8%, 16 patients with ES (35.6%) had a native T1 value above this limit, and 17 (37.8%) had an ECV values higher than the upper limit.

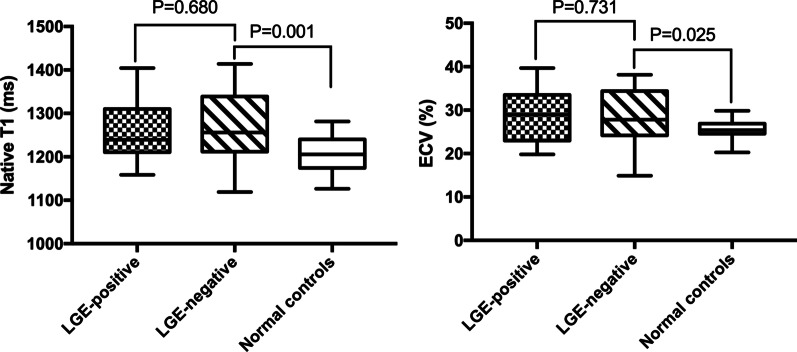

Furthermore, the association between LGE and diffuse myocardial fibrosis was investigated. We found no difference in the native T1 and ECV values between the LGE+ and LGE− subgroups (native T1, 1260 ± 18 vs. 1270 ± 15 ms, P = 0.68; ECV, 29.0 ± 1.5% vs. 28.3 ± 1.1%, P = 0.731); however, both native T1 and ECV values in ES patients in the LGE subgroup were significantly higher than in the healthy controls (both P < 0.05; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Native T1 and ECV box plots for the LGE-positive, LGE-negative, and normal control groups. ECV extracellular volume, LGE late gadolinium enhancement

Correlation between diffuse ventricular fibrosis and clinical characteristics, hemodynamics, and ventricular function

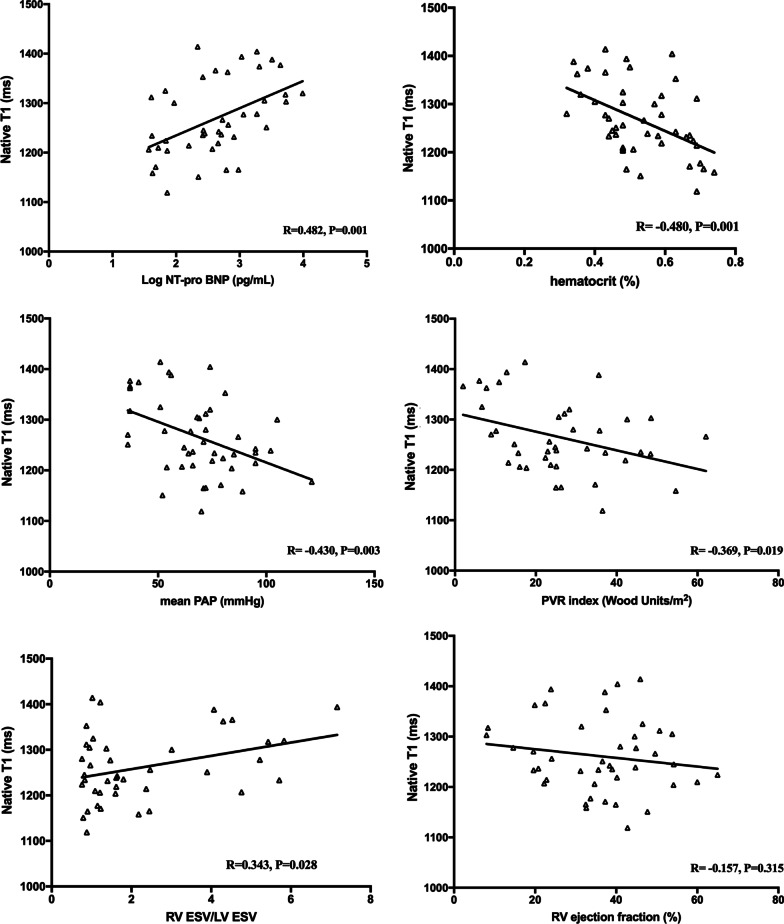

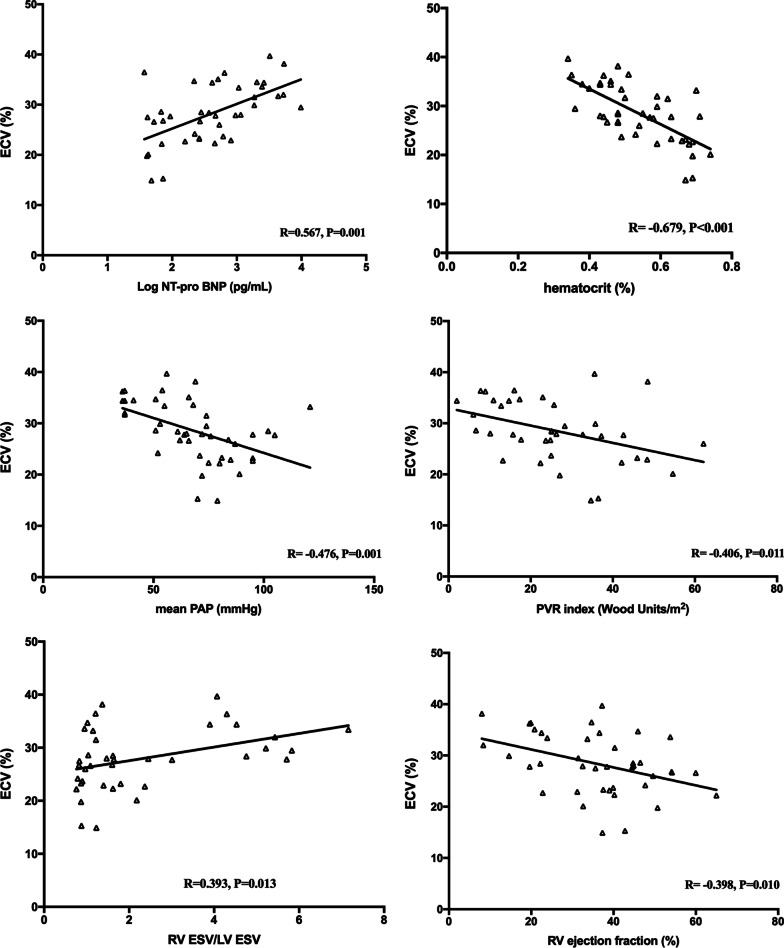

As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, compared to native T1, ECV yielded stronger correlations with serum Log NT-pro BNP (R = 0.567, P = 0.001), Hct (R = − 0.679, P < 0.001), RV afterload represented by mPAP (R = − 0.476, P = 0.001) and PVRI (R = − 0.406, P = 0.011), RV volume represented by RV ESV/LV ESV (R = 0.393, P = 0.013), and RV function represented by RVEF (R = − 0.398, P = 0.010). We found no association between native T1 and RVEF (R = 0.157, P = 0.315). Moreover, correlation trends between 6MWT and native T1 (R = − 0.278, P = 0.075) and ECV (R = − 0.299, P = 0.061) were observed. In the subgroup analysis, there were significant correlations or correlation trends between ECV and Log NT-pro BNP (R = 0.520, P = 0.003 and R = 0.527, P = 0.003), Hct (R = − 0.645, P < 0.001 and R = − 0.637, P < 0.001), mPAP (R = − 0.456, P = 0.008 and R = − 0.222, P = 0.238), PVRI (R = − 0.411, P = 0.027 and R = − 0.183, P = 0.372), RV/LV ESV (R = 0.390, P = 0.036 and R = 0.308, P = 0.098), and RVEF (R = − 0.493, P = 0.005 and R = 0.206, P = 0.094) in patients with intra-cardiac defects and post-tricuspid shunts, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Correlations of myocardial native T1 with biomarkers, RV afterload, and RV remodeling. NT-pro BNP N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, PAP pulmonary artery pressure, PVR pulmonary vascular resistance, RV right ventricular, LV left ventricular, ESV end-systolic volume

Fig. 5.

Correlation of myocardial ECV with biomarkers, RV afterload, and RV remodeling. ECV extracellular volume, NT-pro BNP N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, PAP pulmonary artery pressure, PVR pulmonary vascular resistance, RV right ventricular, LV left ventricular, ESV end-systolic volume

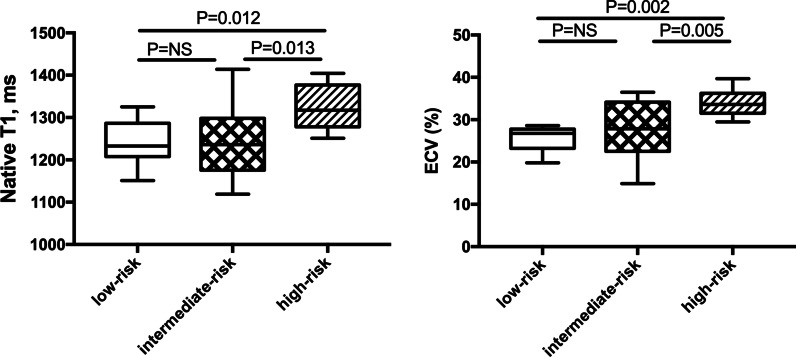

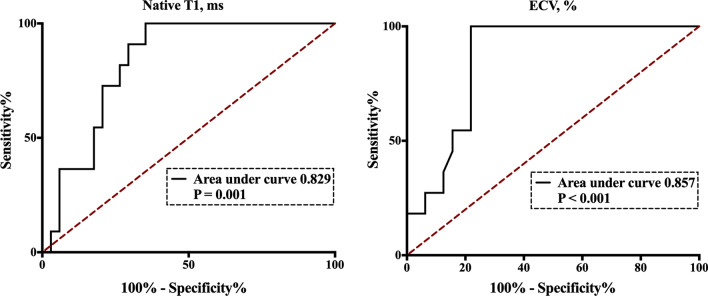

Prediction of risk stratification by native T1 and ECV

As shown in Fig. 6, ES patients in the high-risk group exhibited significantly higher native T1 and ECV values than patients in the low- and intermediate-risk groups (both P < 0.05). Furthermore, ROC curve analysis showed that an ECV threshold of 29.0% could distinguish ES patients in the high-risk group from those in the low- and intermediate-risk groups with an AUC of 0.857 (larger than for native T1; 0.829) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Native T1 and ECV in ES patients with various risk profiles. ECV extracellular volume, ES Eisenmenger syndrome

Fig. 7.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for discriminating ES patients with a high-risk profile from those with low- and intermediate-risk profiles. ECV extracellular volume, ES Eisenmenger syndrome

Discussion

This study comprehensively evaluated myocardial fibrosis by CMR using LGE and T1 mapping. While no significant association was found between focal myocardial fibrosis as indicated by LGE and ES clinical severity, diffuse myocardial fibrosis was remarkable in ES patients and was closely associated with biomarkers of disease progression, impaired pulmonary hemodynamics, and maladaptive RV remodeling. Moreover, diffuse fibrosis performed well in identifying ES patients and a high-risk profile. Furthermore, we observed that the clinical relevance and discrimination ability of ECV were generally better than those of native T1.

CMR is the reference standard for the non-invasive imaging evaluation of myocardial fibrosis. In this study, both focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis were detected in patients with ES using the CMR LGE and T1 mapping techniques, respectively. Broberg et al. reported that 73.0% of 30 ES patients had LGE, but both qualitative and quantitative LGE did not correlated with exercise intolerance, degree of cyanosis, ventricular size and function remodeling, and survival [12]. We have recently characterized LGE distribution in ES patients with different shunt locations [19]. However, the clinical significance of LGE and diffuse myocardial fibrosis in these patients needed to be further elucidated. In this study, LGE at the anterior/inferior VIP was very common and found in 95.6% of ES patients. Therefore, we divided patients with ES into LGE+ and LGE− subgroups according to the presence or absence of myocardial LGE after excluding VIP. Similar with Broberg et al., we did not find the correlation between LGE and clinical disease severity or ventricular size and function. Although LGE was associated with risk stratification and the risk of cardiomyopathy-related death [28], LGE value in patients with PH has long been debated. A study evaluating 124 patients with PH found that LGE did not predict mortality [29], consistent with the findings of Freed et al. and Swift et al., who used multivariate regression analysis and found no association between LGE and additional risks in PH patients [30, 31]. Therefore, LGE in PH, particularly in the anterior/inferior VIP region, is more likely a consequence of muscle fiber disarray following an increase in septal bowing mechanical stress and interstitial space expansion due to RV hypertrophy than a sign of RV pathological decompensation.

Our study demonstrated a significantly higher diffuse myocardial fibrosis in LGE− ES patients than in the healthy controls. This finding was consistent with the previous understanding that T1 mapping has been established as a substantiated and reproducible CMR technique to accurately quantify diffuse myocardial fibrosis before LGE onset [32–34]. Besides, we found no difference in diffuse myocardial fibrosis changes between those with and without LGE among patients with ES. We think it is reasonable and interpretable since we have excluded replacement fibrosis as the cause for native T1 and ECV elevation by actively avoiding contouring LGE areas in the myocardial mapping process.

Diffuse myocardial fibrosis might be the pathophysiological cause of ventricular dysfunction in ES patients. Noteworthy, only one study, published by Broberg et al. in 2010, quantified diffuse myocardial fibrosis in ten patients with cyanotic heart disease in the subgroup analysis, demonstrating a correlation between the global LV diffuse fibrosis and LV end-diastolic volume index (EDVI) and ejection fraction (EF) [13]. Nevertheless, the correlation between diffuse fibrosis and RV function has not been investigated even though right heart failure has been known as the main determinant of disease progression and poor outcomes in ES patients [2–4]. Our study provided preliminary insights into the knowledge gap in this field, showing that ES patients and various shunt locations had significantly different right heart remodeling and diffuse myocardial fibrosis [19]. These findings suggested that diffuse myocardial fibrosis might correlate with RV remodeling [19]. However, the clinical significance of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in ES patients was not investigated. In the present study, higher diffuse myocardial fibrosis was confirmed in ES patients than healthy controls and associated with increased serum NT pro-BNP level and secondary erythrocytosis, both substantial serological markers reflecting the severity of heart failure and predicting mortality in ES patients [35, 36]. Additionally, a correlation between diffuse myocardial fibrosis and increased RV afterload was observed. Previous studies have shown that diffuse myocardial fibrosis was an important byproduct of adverse ventricular loading [37]. More importantly, elevated ECV was positively correlated with maladaptive RV expansion and negatively correlated with RV systolic dysfunction. These findings supported the speculation that diffuse myocardial fibrosis had a vital role in the RV response mechanism to persistent volume and pressure overload, extending our knowledge of contributors to RV dysfunction in ES patients.

In recent years, patients with PH benefited greatly from the advent of targeted therapy [23]. The current PH guidelines recommend a risk assessment tool and risk stratification-guided targeted therapy, especially for patients with idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension [23, 26]. The application and performance of the risk stratification strategy in patients with ES need further validation. Considering that the pathophysiology and prognosis of patients with ES are distinct from those with idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension, increasing numbers of scholars advocate the establishment of a unique risk assessment tool for ES patients [38, 39]. In the present study, diffuse myocardial fibrosis in ES patients with a high-risk profile was significantly higher than in those with low- and intermediate-risk profiles, supporting a promising pathological marker for ES risk stratification.

A plausible explanation for the better clinical correlation and discrimination performance of ECV than native T1 mapping is that ECV could be normalized by comparing changes in T1 relaxation rates in the blood pool before and after contrast administration and was highly accurate and reproducible, while native T1 could be affected by intracellular water content, field strengths, the CMR system acquisition sequence, and individual conditions [40, 41]. All the above suggest a potential value for ECV in clinical severity assessment and a possible prognostic role in patients with ES.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, a relatively small number of subjects was recruited; however, given the low prevalence of ES, the sample size compared favorably with published studies. Second, we did not determine the predictive value of native T1 and ECV for future events (arrhythmia, death, hemoptysis, etc.) in patients with ES. Further research is warranted to determine whether alterations in diffuse ventricular fibrosis have prognostic significance and reveal whether targeting fibrosis could be a strategy to slow down the maladaptive process, prevent the development of RV failure, and allow full recovery of cardiac function in patients with ES.

Conclusions

The marked diffuse myocardial fibrosis found in patients with ES was significantly correlated with clinical severity, RV afterload, RV size, RV systolic function, and the risk stratification profile.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. The risk stratification approach. Low risk: at least three low-risk criteria and no high-risk criteria; Intermediate risk: definitions of low or high risk not fulfilled; High risk: at least two high-risk criteria including CI or SvO2. WHO, World Health Organization; 6MWT, 6-min walking distance; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; RAP, right atrial pressure; CI, cardiac index; SvO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation.

Additional file 2. Comparison between ES patients with and without LGE. ES, Eisenmenger syndrome; BMI, body mass index; HR, heart rate; SpO2, peripheral arterial oxygen saturation; WHO, World Health Organization; 6MWD, 6-min walking distance; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; Hct, hematocrit; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PVRi, pulmonary vascular resistance index; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; EDVi, end-diastolic volume index; ESVi, end-systolic volume index; EF, ejection fraction; massi, mass index; SVi, stroke volume index.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 6MWT

6 Minute walk test

- APVD

Anomalous pulmonary venous drainage

- ASD

Atrial septal defect

- AUC

Area under the curve

- bSSFP

Balanced steady-state free precession

- CMR

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- CI

Cardiac index

- CO

Cardiac output

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- ECV

Extracellular volume fraction

- EDVI

End-diastolic volume index

- EF

Ejection fraction

- ES

Eisenmenger syndrome

- ESV

End-systolic volume

- ESVI

End-systolic volume index

- FA

Flip angle

- FOV

Field-of-view

- Hct

Hematocrit

- LGE

Late gadolinium enhancement

- LGE+

Late gadolinium enhancement positive

- LGE−

Late gadolinium enhancement negative

- LV

Left ventricle/left ventricular

- LVMI

Left ventricular mass index

- MOLLI

Motion-corrected modified Look-Locker inversion recovery

- mPAP

Mean pulmonary artery pressure

- mRAP

Mean right atrial pressure

- NT-pro BNP

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

- PAWP

Pulmonary artery wedge pressure

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- PH

Pulmonary hypertension

- PVR

Pulmonary vascular resistance

- PVRI

Pulmonary vascular resistance index

- Qp:Qs

Pulmonary to systemic flow ratio

- RHC

Right heart catheterization

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROI

Region of interest

- RV

Right ventricle/right ventricular

- RVEF

Right ventricular ejection fraction

- SpO2

Peripheral arterial oxygen saturation

- SvO2

Mixed venous oxygen saturation

- SVI

Stroke volume index

- TE

Echo time

- TR

Repetition time

- TI

Inversion time

- VIP

Ventricular insertion point

- VSD

Ventricular septal defect

- VIP

Ventricular insertion point

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

YCC designed the study and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. JH collected clinical data and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. LDY collected clinical data and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. BW collected clinical data and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. SFP collected clinical data and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. CG analyzed data, performed statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript, and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. JHG analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. KW interpreted the results and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. CC interpreted the results and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. LLW interpreted the results and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. XLC interpreted the results and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. JJG interpreted the results and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the 1·3·5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant number ZYJC18013); and the National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant number Z2018A08).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol conforms with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at West China Hospital (2018271). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chao Gong and Jinghua Guo contributed equally to this paper

References

- 1.Diller GP, Kempny A, Inuzuka R, Radke R, Wort SJ, Baumgartner H, et al. Survival prospects of treatment naive patients with Eisenmenger: a systematic review of the literature and report of own experience. Heart. 2014;100:1366–1372. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nashat H, Kempny A, McCabe C, Price LC, Harries C, Alonso-Gonzalez R, et al. Eisenmenger syndrome: current perspectives. Res Rep Clin Cardiol. 2017;8:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diller GP, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Kempny A, Dimopoulos K, Inuzuka R, Giannakoulas G, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations in contemporary Eisenmenger syndrome patients: predictive value and response to disease targeting therapy. Heart. 2012;98:736–742. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diller GP, Dimopoulos K, Broberg CS, Kaya MG, Naghotra US, Uebing A, et al. Presentation, survival prospects, and predictors of death in Eisenmenger syndrome: a combined retrospective and case-control study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1737–1742. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchhorn R, Ross RD, Bartmus D, Wessel A, Hulpke-Wette M, Bursch J. Activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and sympathetic nervous system and their relation to hemodynamic and clinical abnormalities in infants with left-to-right shunts. Int J Cardiol. 2001;78:225–230. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(01)00398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohn JN. Myocardial structural effects of aldosterone receptor antagonism in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:597–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diller GP, Dimopoulos K, Okonko D, Li W, Babu-Narayan SV, Broberg CS, et al. Exercise intolerance in adult congenital heart disease: comparative severity, correlates, and prognostic implication. Circulation. 2005;112:828–835. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez-Arroyo J, Santos-Martinez LE, Aranda A, Pulido T, Beltran M, Munoz-Castellanos L, et al. Differences in right ventricular remodeling secondary to pressure overload in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:603–606. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1711LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swoboda PP, McDiarmid AK, Erhayiem B, Law GR, Garg P, Broadbent DA, et al. Effect of cellular and extracellular pathology assessed by T1 mapping on regional contractile function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan K, Li W, Sun J, Xu Y, Wang J, Liu H, et al. Regional amyloid distribution and impact on mortality in light-chain amyloidosis: a T1 mapping cardiac magnetic resonance study. Amyloid. 2019;26:45–51. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2019.1578742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Li W, Wan K, Liang Y, Jiang X, Wang J, et al. Myocardial tissue reverse remodeling after guideline-directed medical therapy in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14:e007944. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broberg CS, Prasad SK, Carr C, Babu-Narayan SV, Dimopoulos K, Gatzoulis MA. Myocardial fibrosis in Eisenmenger syndrome: a descriptive cohort study exploring associations of late gadolinium enhancement with clinical status and survival. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:32. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-16-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broberg CS, Chugh SS, Conklin C, Sahn DJ, Jerosch-Herold M. Quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and its association with myocardial dysfunction in congenital heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:727–734. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.842096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broberg CS, Huang J, Hogberg I, McLarry J, Woods P, Burchill LJ, et al. Diffuse LV myocardial fibrosis and its clinical associations in adults with repaired tetralogy of fallot. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:86–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang D, Li X, Sun JY, Cheng W, Greiser A, Zhang TJ, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance evidence of myocardial fibrosis and its clinical significance in adolescent and adult patients with Ebstein’s anomaly. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018;20:69. doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roller FC, Wiedenroth C, Breithecker A, Liebetrau C, Mayer E, Schneider C, et al. Native T1 mapping and extracellular volume fraction measurement for assessment of right ventricular insertion point and septal fibrosis in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:1980–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiter U, Reiter G, Kovacs G, Adelsmayr G, Greiser A, Olschewski H, et al. Native myocardial T1 mapping in pulmonary hypertension: correlations with cardiac function and hemodynamics. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:157–166. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4360-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel RB, Li E, Benefield BC, Swat SA, Polsinelli VB, Carr JC, et al. Diffuse right ventricular fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary hypertension. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:253–263. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong C, He S, Chen X, Wang L, Guo J, He J, et al. Diverse right ventricular remodeling evaluated by MRI and prognosis in Eisenmenger syndrome with different shunt locations. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;55:1478–1488. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broberg CS, Ujita M, Prasad S, Li W, Rubens M, Bax BE, et al. Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in Eisenmenger syndrome is associated with biventricular dysfunction and decreased pulmonary flow velocity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galie N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, Granton J, Berger RM, Lauer A, et al. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 2006;114:48–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatzoulis MA, Landzberg M, Beghetti M, Berger RM, Efficace M, Gesang S, et al. Evaluation of macitentan in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. Circulation. 2019;139:51–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Respir J. 2015;46:903–975. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01032-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong Y, Yang D, Han Y, Cheng W, Sun J, Wan K, et al. Age and gender impact the measurement of myocardial interstitial fibrosis in a healthy adult Chinese population: a cardiac magnetic resonance study. Front Physiol. 2018;9:140. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laboratories ATSCoPSfCPF ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galie N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, Grunig E, Jing ZC, Moiseeva O, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801889. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01889-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG, et al. Standardized image interpretation and post processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) board of trustees task force on standardized post processing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:35. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gulati A, Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Guha K, Khwaja J, Raza S, et al. Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2013;309:896–908. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abouelnour AE, Doyle M, Thompson DV, Yamrozik J, Williams RB, Shah MB, et al. Does late gadolinium enhancement still have value? Right ventricular internal mechanical work, Ea/Emax and late gadolinium enhancement as prognostic markers in patients with advanced pulmonary hypertension via cardiac MRI. Cardiol Res Cardiovasc Med. 2017;2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Freed BH, Gomberg-Maitland M, Chandra S, Mor-Avi V, Rich S, Archer SL, et al. Late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts clinical worsening in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:11. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swift AJ, Rajaram S, Capener D, Elliot C, Condliffe R, Wild JM, et al. LGE patterns in pulmonary hypertension do not impact overall mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:1209–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.aus dem Siepen F, Buss SJ, Messroghli D, Andre F, Lossnitzer D, Seitz S, et al. T1 mapping in dilated cardiomyopathy with cardiac magnetic resonance: quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:210–216. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fontana M, White SK, Banypersad SM, Sado DM, Maestrini V, Flett AS, et al. Comparison of T1 mapping techniques for ECV quantification. Histological validation and reproducibility of ShMOLLI versus multibreath-hold T1 quantification equilibrium contrast CMR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:88. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iles L, Pfluger H, Phrommintikul A, Cherayath J, Aksit P, Gupta SN, et al. Evaluation of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with cardiac magnetic resonance contrast-enhanced T1 mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1574–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin-Garcia AC, Arachchillage DR, Kempny A, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Martin-Garcia A, Uebing A, et al. Platelet count and mean platelet volume predict outcome in adults with Eisenmenger syndrome. Heart. 2018;104:45–50. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-311144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reardon LC, Williams RJ, Houser LS, Miner PD, Child JS, Aboulhosn JA. Usefulness of serum brain natriuretic peptide to predict adverse events in patients with the Eisenmenger syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babu-Narayan SV, Kilner PJ, Li W, Moon JC, Goktekin O, Davlouros PA, et al. Ventricular fibrosis suggested by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in adults with repaired tetralogy of fallot and its relationship to adverse markers of clinical outcome. Circulation. 2006;113:405–413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimopoulos K, Wort SJ, Gatzoulis MA. Pulmonary hypertension related to congenital heart disease: a call for action. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:691–700. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arvanitaki A, Giannakoulas G, Baumgartner H, Lammers AE. Eisenmenger syndrome: diagnosis, prognosis and clinical management. Heart. 2020;106:1638–1645. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-316665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Liu X, Yang F, Wang J, Xu Y, Fang T, et al. Prognostic value of myocardial extracellular volume fraction evaluation based on cardiac magnetic resonance T1 mapping with T1 long and short in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:4557. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07650-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersen S, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Vonk Noordegraaf A, de Man FS. Right ventricular fibrosis. Circulation. 2019;139:269–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. The risk stratification approach. Low risk: at least three low-risk criteria and no high-risk criteria; Intermediate risk: definitions of low or high risk not fulfilled; High risk: at least two high-risk criteria including CI or SvO2. WHO, World Health Organization; 6MWT, 6-min walking distance; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; RAP, right atrial pressure; CI, cardiac index; SvO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation.

Additional file 2. Comparison between ES patients with and without LGE. ES, Eisenmenger syndrome; BMI, body mass index; HR, heart rate; SpO2, peripheral arterial oxygen saturation; WHO, World Health Organization; 6MWD, 6-min walking distance; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; Hct, hematocrit; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PVRi, pulmonary vascular resistance index; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; EDVi, end-diastolic volume index; ESVi, end-systolic volume index; EF, ejection fraction; massi, mass index; SVi, stroke volume index.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.