Abstract

Background

Dermographism is the most common form of chronic inducible urticaria. However, the natural history and clinical course of patients with dermographism in tropical countries has not fully been described.

Objective

To examine clinical features, natural history and clinical course of dermographism in Thai patients according to their experiences.

Methods

A cross-sectional, internet-based survey was conducted in 2021. All study respondents completed a 45-item questionnaire that was circulated on social media regarding dermographism.

Results

Among the 2,456 respondents who reported dermographism, 1,900 had symptomatic dermographism (SD), while 556 had simple dermographism (SimD). Of the respondents who reported SD and SimD, the female to male ratio was 2.2:1 and 2.4:1, respectively. The median age of the first episode of SD and SimD was 16 and 15 years, respectively. Older age, greater body weight, cardiovascular diseases, allergic conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis, changes in temperature, and family history of dermographism were all factors linked to an increased probability of SD. Half of the respondents with SD reported moderate itch severity. Moreover, about half of SD and almost all of SimD respondents let the wheal resolve on its own. Second generation H1-antihistamines were most commonly prescribed while over-the-counter medicines were taken by both SD and SimD respondents.

Conclusion

This survey highlights several aspects of dermographism in Thai patients which can be useful for healthcare providers. SD is troublesome and affects the quality of life of many patients, leading some to seek medication themselves.

Keywords: Clinical course, Chronic inducible urticaria, Dermographism, Natural history, Tropical country

INTRODUCTION

Dermographism is one of the common dermatologic problems in clinical practice. The meaning of dermographism for the lay person is “writing on the skin”. Dermographism is characterized by the occurrence of wheals after stroking or rubbing the skin [1]. Dermographism typically occurs within seconds to minutes after exposure to a stimulant and may last for one to 3 hours [2,3]. The overall prevalence of dermographism in the general population according to previous reports ranges from 1%–5% [4,5], with a greater prevalence in young adults and females [6,7]. The pathogenesis of dermographism is still uncertain, but histamine liberated from mast cells has been postulated as a mechanism in most studies [8,9].

Diagnosis of dermographism is based on patient history and confirmed by a provocation test using a smooth blunt object (closed ball pen or a wooden spatula), dermographometer, or Fric test [1,10]. The onset of a pruritic palpable wheal with itch within 10 minutes of provocation is considered symptomatic dermographism (SD) [1]. SD is distinguished from simple dermographism (SimD) by the presence of itching and/or burning sensation of a wheal [6,11]. The symptoms of dermographism and intense itch may limit daily activities [12]. Although there are several reports [6,8,12,13] about the clinical characteristics, aggravating factors, comorbidities, severity of dermographism, and management of patients, there is still limited information in particular aspects. To fill this gap, we generated a comprehensive questionnaire to describe the clinical presentation and management of patients with dermographism according to their experiences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a descriptive cross-sectional, internet-based survey conducted in Thai participants between May to July 2021. The study protocol was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (COA no. 204/2021). Informed consents were obtained from all participants. All study participants were invited to anonymously complete the online questionnaire via social media (i.e., Facebook or Line application). The questionnaire was sent to the general population and was not distributed to urticaria patients or those with other skin diseases. The following information was provided to all recipients in Thai: “Dermographism is a chronic skin condition with a red and raised line (wheal) or sometimes a red area (flare) on the part of the skin that is scratched or rubbed with a blunt object. It can occur in areas associated to tight clothing such as the edge of your underwear or pants, or when your skin rubs against the edge of a table. Each dermographism lesion lasts for a short time. As it heals, the skin returns to its normal appearance. Dermographism can come along with itching in some people, known as SD. The symptoms can affect a person’s daily life and dermographism may last many years.” A picture of dermographism was provided on the first page of the questionnaire along with the aforementioned description of dermographism to allow respondents to determine if he/she had the condition. The eligible criteria included being a male or female aged 18 or above, ability to read and understand the Thai-language questionnaire, a willingness to respond to the online survey, and previous experience of dermographism. This survey was a self-administered questionnaire and required only 5–10 minutes to complete. The questionnaire consisted of 45 questions covering the following:

(1) Demographic data: age, gender, height, body weight, and family history of dermographism

(2) Underlying conditions, history of allergy, and family history of allergy

(3) Clinical characteristics and associated factors of dermographism: age at which first episode of dermographism happened, current status of dermographism, part of the body where dermographism usually appears, aggravating factors, average duration of wheals, time of the day which wheals usually occur, frequency of dermographism, occurrence of angioedema with dermographism, and occurrence and relation of spontaneous wheals to dermographism

(4) Severity of dermographism and its effect on quality of life: severity of wheals, severity of itch using a 10-centimeter visual analogue scale (VAS)

(5) Management of dermographism according to respondents’ experiences: name of over-the-counter (OTC) medicine and prescription drugs, frequency and regularity of taking medicines, response after taking medicines, duration of medicine use, side effects of medicine use, type of physician visited, and number of physicians visited

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Descriptive statistics including the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range were used to analyze continuous variables. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were reported. Statistical associations of categorical data between groups were analyzed using the chi-square test of independence and Fisher exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine potential risk factors for SD. The multivariate model used forward variable selection to identify variables independently associated with SD. Results were reported with a 95% confidence interval and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Among 2,456 respondents, SD was reported in 1,900 respondents (77.4%) and SimD was 556 respondents (22.6%). The majority of respondents with SD and SimD were below 60 years and female (Table 1). The total female to male ratio was 2.2:1. The body weight and body mass index was significantly higher in the SD group than SimD group (p = 0.033 and p = 0.003, respectively). Only 688 participants (28%) reporting underlying conditions, the cardiovascular diseases were significantly higher in SD than SimD groups (p < 0.02). Personal history of atopy was significantly more often in SD than SimD groups (p < 0.001) especially in allergic conjunctivitis (p = 0.036) and atopic dermatitis (p < 0.001). A family history of dermographism (1st degree relative) in SD was significantly higher than SimD group (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Demographics of respondents with dermographism.

| Characteristic | Total (n = 2,456) | SD (n = 1,900) | SimD (n = 556) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 43.6 ± 14.2 | 44.2 ± 14.1 | 41.7 ± 14.2 | <0.001* | |

| Age group (yr) | <0.001* | ||||

| 18–30 | 596 (24.3) | 422 (22.2) | 174 (31.3)† | ||

| 31–45 | 700 (28.5) | 560 (29.5) | 140 (25.2)† | ||

| 46–60 | 856 (34.9) | 665 (35.0) | 191 (34.4) | ||

| >60 | 304 (12.4) | 253 (13.3) | 51 (9.2)† | ||

| Female sex | 1,693 (68.9) | 1,302 (68.5) | 391 (70.3) | 0.421 | |

| Body weight (kg) | 62.4 ± 14.0 | 62.7 ± 14.1 | 61.3 ± 13.7 | 0.033* | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 (20.3–25.7) | 23.0 (20.4–25.8) | 22.3 (20.0–25.3) | 0.003* | |

| Underlying diseases‡ | |||||

| Hypertension | 266 (10.8) | 215 (11.3) | 51 (9.2) | 0.153 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 112 (4.6) | 85 (4.5) | 27 (4.9) | 0.704 | |

| Thyroid diseases | 57 (2.3) | 48 (2.5) | 9 (1.6) | 0.211 | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 49 (2.0) | 45 (2.4) | 4 (0.7) | 0.014* | |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 19 (0.8) | 15 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | 0.868 | |

| Liver diseases | 6 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.623 | |

| Renal diseases | 7 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0.597 | |

| Cancer | 16 (0.7) | 12 (0.6) | 4 (0.7) | 0.821 | |

| History of symptoms of atopy | 1,469 (59.8) | 1,210 (63.7) | 259 (46.6) | <0.001* | |

| Symptoms of atopy‡ | |||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 1,084 (73.8) | 885 (73.1) | 199 (76.8) | 0.220 | |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 756 (51.5) | 638 (52.7) | 118 (45.6) | 0.036* | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 798 (54.3) | 694 (57.4) | 104 (40.2) | <0.001* | |

| Asthma | 99 (6.7) | 85 (7.0) | 14 (5.4) | 0.345 | |

| Family history of atopy (1st degree relative) | 866 (59.0) | 712 (58.8) | 154 (59.5) | 0.855 | |

| Family history of dermographism (1st degree relative) | 492 (20.0) | 419 (22.1) | 73 (13.1) | <0.001* | |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation, number (%), or median (interquartile range).

SD, symptomatic dermographism; SimD, simple dermographism.

*Statistical significance. †Significant between group. ‡Respondents were able to choose more than one response.

Clinical characteristics, disease severity, and associated factors (Table 2)

Table 2. Clinical characteristics and associated factors of dermographism.

| Characteristic | Total (n = 2,456) | SD (n = 1,900) | SimD (n = 556) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age onset of the 1st episode of dermographism (yr) | 16 (10–28) | 16 (10–30) | 15 (10–25) | 0.065 | |

| Current symptoms of dermographism | 1,245 (50.7) | 1,017 (53.5) | 228 (41.0) | <0.001* | |

| Locations of dermographism‡ | |||||

| Arm | 2,014 (82.0) | 1,559 (82.1) | 455 (81.8) | 0.906 | |

| Leg | 1,767 (71.9) | 1,390 (73.2) | 377 (67.8) | 0.013* | |

| Trunk | 1,260 (51.3) | 1,049 (55.2) | 211 (37.9) | <0.001* | |

| Face | 326 (13.3) | 284 (14.9) | 42 (7.6) | <0.001* | |

| Scalp | 124 (5.0) | 115 (6.1) | 9 (1.6) | <0.001* | |

| Severity of dermographism | <0.001* | ||||

| Skin-colored raised linear wheal | 149 (9.7) | 116 (9.2) | 33 (12.3) | ||

| Slightly red raised linear wheal | 500 (32.7) | 374 (29.6) | 126 (47.0)† | ||

| Obviously red and raised linear wheal | 399 (26.1) | 330 (26.1) | 69 (25.7) | ||

| Raised and red linear wheals with a surrounding red area | 482 (31.5) | 442 (35.0) | 40 (14.9)† | ||

| Duration of dermographism (min) | 30 (10–40) | 30 (15–60) | 15 (10–30) | <0.001* | |

| Time of the day when dermographism occurred‡ | |||||

| Morning after waking up | 95 (3.9) | 75 (3.9) | 20 (3.6) | 0.706 | |

| Daytime during activities | 892 (36.3) | 660 (34.7) | 232 (41.7) | 0.003* | |

| Evening during activities | 497 (20.2) | 424 (22.3) | 73 (13.1) | <0.001* | |

| Any time of the day | 1,021 (41.6) | 782 (41.2) | 239 (43.0) | 0.442 | |

| Day (s) per week when respondents usually had dermographism | <0.001* | ||||

| 1 | 1,422 (57.9) | 1,010 (53.2) | 412 (74.1)† | ||

| 2 | 400 (16.3) | 336 (17.7) | 64 (11.5)† | ||

| 3 | 281 (11.4) | 256 (13.5) | 25 (4.5)† | ||

| 4 | 98 (4.0) | 90 (4.7) | 8 (1.4)† | ||

| 5 | 73 (3.0) | 63 (3.3) | 10 (1.8) | ||

| 6 | 15 (0.6) | 14 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| 7 | 167 (6.8) | 131 (6.9) | 36 (6.5) | ||

| Dermographism affected by the temperature | 1,666 (67.8) | 1,395 (73.4) | 271 (48.7) | <0.001* | |

| Type of weather in which dermographism occurred frequently | 0.004* | ||||

| Hot weather | 1,063 (63.8) | 869 (62.3) | 194 (71.6)† | ||

| Cold weather | 169 (10.1) | 141 (10.1) | 28 (10.3) | ||

| Both kinds of weather | 434 (26.1) | 385 (27.6) | 49 (18.1)† | ||

| Aggravating factors‡ | |||||

| Stroking/scratching of skin | 1,440 (58.6) | 1,084 (57.1) | 356 (64.0) | 0.003* | |

| Rubbing by object, such as edge of a table | 831 (33.8) | 621 (32.7) | 210 (37.8) | 0.026* | |

| Drying oneself with a towel after showering or bathing | 194 (7.9) | 162 (8.5) | 32 (5.8) | 0.033* | |

| Wearing tight clothes | 1,329 (54.1) | 1,079 (56.8) | 250 (45.0) | <0.001* | |

| Menstruation | 171 (7.0) | 151 (7.9) | 20 (3.6) | <0.001* | |

| Stress | 417 (17.0) | 363 (19.1) | 54 (9.7) | <0.001* | |

| Drugs | 20 (0.8) | 15 (0.8) | 5 (0.9) | 0.800 | |

| Effect on quality of daily life or activity | <0.001* | ||||

| No | 708 (28.8) | 388 (20.4) | 320 (57.6)† | ||

| A little | 1,157 (47.1) | 958 (50.4) | 199 (35.8)† | ||

| Moderate | 441 (18.0) | 412 (21.7) | 29 (5.2)† | ||

| Severe | 150 (6.1) | 142 (7.5) | 8 (1.4)† | ||

| Effect of dermographism on sleep | <0.001* | ||||

| No | 1,031 (42.0) | 632 (33.3) | 399 (71.8)† | ||

| A little | 883 (36.0) | 756 (39.8) | 127 (22.8)† | ||

| Moderate | 356 (14.5) | 337 (17.7) | 19 (3.4)† | ||

| Severe | 186 (7.6) | 175 (9.2) | 11 (2.0)† | ||

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

SD, symptomatic dermographism; SimD, simple dermographism.

*Statistical significance. †Significant between group. ‡Respondents were able to choose more than one response.

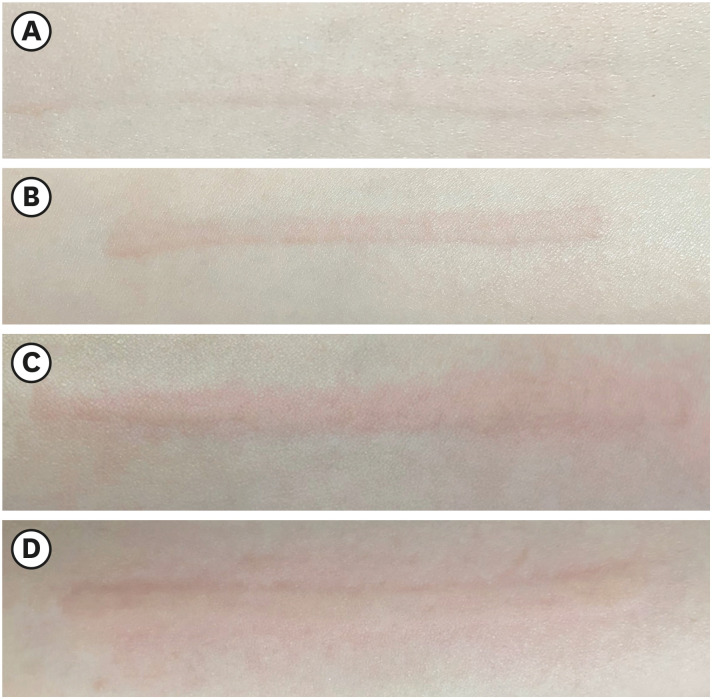

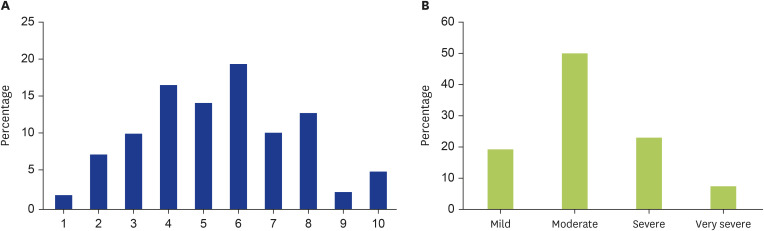

Respondents with SD had been active dermographism higher than SimD group (p < 0.001). The dermographism was initially appeared in adolescence in both groups. Arm was the most reported location of dermographism (82%). The median duration of symptoms in SD significantly longer than SimD group (p < 0.001). The severity of dermographism was categorized into 4 grades as shown in Fig. 1 and assessed in this survey. The severity of symptoms in SD was more intense than SimD group. In the SD group, 60% of SD reported obviously red and raised linear wheal and progress with surrounding flare in some patients. Whereas, 47% of SimD reported slightly raised and redden wheals. In SD group, half of them reported moderate severity of itch (Fig. 2). Focus on the frequency in each week, dermographism occurred more frequency in SD than SimD groups (p < 0.001). Nearly half of participants (41.6%) suffered from symptoms any time of the day. Concomitant angioedema was reported in 194 respondents (7.9%). Coexisting spontaneous wheals were reported in 529 respondents (21.5%).

Fig. 1. Severity of dermographism was categorized as skin-colored raised linear wheal (A), slightly red raised linear wheal (B), obviously red and raised linear wheal (C), and raised and red linear wheals (D) with a surrounding red area.

Fig. 2. The greatest severity of itch was reported by respondents’ experiences in the 1,900 symptomatic dermographism (SD) group. (A) Percentage of respondents who responded to each severity of itch was assessed by a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 1 to 10. (B) SD respondents’ VAS scores were categorized based on Reich et al. [23] into 4 levels, including mild (VAS score 1–3), moderate (VAS score 4–6), severe (VAS score 7–8), and very severe (VAS score 9–10).

A change in temperature was reported as more of a significant aggravating factor in the SD group than the SimD group (p < 0.001). Hot weather was the condition most reported to induce dermographism in both groups. Stroking or scratching of skin was the most common aggravating factor. Other reported factors including rubbing by object, bathing, drying by a towel, wearing tight clothes, menstruation and stress were significantly related in SD than SimD. In the aspect of severity and quality of life impairment, nearly 30% of SD respondents reported moderate to severe effects in quality of daily activities and sleep. Whereas half of SimD participants reported no effect in both aspects.

Factors independently associated with probability of SD from univariate and multivariate logistic regression are illustrated in Table 3. Interestingly, the factors of increasing age, cardiovascular diseases and changing in both hot and cold temperature strongly increased the probability of SD approximately 2 to 3 folds with the odds ratio 1.985 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.377–2.861), 2.895 (95% CI, 1.006–8.332), and 3.399 (95% CI, 2.410–4.794), respectively.

Table 3. Factors independently associated with probability of symptomatic dermographism from univariate and multivariate logistic regression.

| Factor | Univariable, OR (95% CI)† | Multivariable, OR (95% CI)†* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (1-kg increasing) | 1.008 (1.001–1.015) | 1.009 (1.002–1.016) | |

| Age group (yr) | |||

| 18–30 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| 31–45 | 1.649 (1.277–2.130) | 1.486 (1.136–1.944) | |

| 46–60 | 1.436 (1.131–1.823) | 1.295 (1.007–1.665) | |

| >60 | 2.045 (1.443–2.899) | 1.985 (1.377–2.861) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 3.348 (1.199–9.349) | 2.895 (1.006–8.332) | |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 1.877 (1.499–2.349) | 1.463 (1.148–1.863) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 2.501 (1.982–3.156) | 1.746 (1.358–2.245) | |

| Changes in temperature | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| Hot temperature | 2.528 (2.043–3.128) | 2.293 (1.842–2.856) | |

| Cold temperature | 2.842 (1.847–4.372) | 2.565 (1.653–3.978) | |

| Both hot and cold temperature | 4.434 (3.185–6.173) | 3.399 (2.410–4.794) | |

| Family history of dermographism (1st degree relative) | 1.872 (1.430–2.450) | 1.523 (1.150–2.017) | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; reference, reference value for odds ratio.

*From logistic regression models that included age, age group, weight, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, history of any symptoms of allergy, allergic conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis, respondents who had dermographism at present, changes in environmental temperature, and family history of dermographism. †Comparison of respondents with symptomatic dermographism versus simple dermographism.

Management of dermographism

The majority of respondents with SD (58.7%) and SimD (82.2%) reported they let dermographism resolve on its own (Table 4). However, the SD group was reported to take medication significantly higher than SimD group (p < 0.001).

Table 4. Respondents’behaviors to manage dermographism.

| Question | Take OTC medicines (n = 382) | See a doctor for treatment (n = 248) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD (n = 346) | SimD (n = 36) | p value | SD (n = 216) | SimD (n = 32) | p value | ||

| Type of physician patients see for diagnosis and treatment of dermographism | 0.987 | ||||||

| General practitioner | - | - | 39 (18.1) | 6 (18.8) | |||

| Dermatologist | - | - | 148 (68.5) | 22 (68.8) | |||

| Allergist | - | - | 29 (13.4) | 4 (12.5) | |||

| Frequency of taking OTC medicines | 0.558 | ||||||

| 1–3 days per week | 288 (83.2) | 28 (77.8) | - | - | |||

| 4–6 days per week | 37 (10.7) | 6 (16.7) | - | - | |||

| Everyday | 21 (6.1) | 2 (5.6) | - | - | |||

| Taking medicines regularly | 0.786 | 0.493 | |||||

| Yes | 54 (15.6) | 5 (13.9) | 128 (59.3) | 21 (65.6) | |||

| No | 292 (84.4) | 31 (86.1) | 88 (40.7) | 11 (34.4) | |||

| Duration of taking medicines (yr) | 3 (1–9.8) | 3 (1–5) | 0.519 | 1 (0.2–2) | 1 (0–1) | 0.287 | |

| Effect of medicines on dermographism | 0.328 | 0.115 | |||||

| No improvement at all | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.8) | 0 (0) | |||

| Partially improved but was not completely controlled | 101 (29.2) | 7 (19.4) | 76 (35.2) | 10 (31.3) | |||

| Did not occur during the course of medication but it recurred when medication was discontinued | 55 (15.9) | 4 (11.1) | 41 (19.0) | 2 (6.3) | |||

| Improved and it did not recur when medicine was discontinued | 186 (53.8) | 25 (69.4) | 93 (43.1) | 20 (62.5) | |||

| Effect of medicines on itch | |||||||

| Not improve at all | 3 (0.9) | - | 3 (1.4) | - | |||

| Partially improved but not completely disappeared | 107 (30.9) | - | 76 (35.2) | - | |||

| Did not occur during the course of medication but it recurred when medication was discontinued | 66 (19.1) | - | 47 (21.8) | - | |||

| Improved and it did not recur even when medicine was discontinued | 170 (49.1) | - | 90 (41.7) | - | |||

| Side effect(s) from taking medicines | 23 (6.6) | 3 (8.3) | 0.702 | 33 (15.3) | 0 (0) | 0.018* | |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (interquartile range).

OTC, over-the-counter; SD, symptomatic dermographism; SimD, simple dermographism.

*Statistical significance.

“Took OTC medicines” group (382 respondents)

Only 64.7% filling the name of the medicine, H1-antihistamines (AH1) was the most reported medication (95.5%) including 1st generation (30.9%), 2nd generation (64.2%), and both generations (4.9%). Approximately 80% of SD and SimD respondents reported to take medication irregularly with the frequency of 1–3 days per week. The median treatment duration was approximately 3 years in both groups. For treatment outcomes, the majority of SD (53.8%) and SimD (69.4%) respondents reported an improvement of symptoms without recurrence after stop medication. Additionally, less than 10% of respondents experienced side effects including drowsiness, dry mouth, blurred vision, dizziness, and headache.

“See a doctor for treatment” group (248 participants)

Nearly 70% of respondents of this group chose to consult dermatologists for diagnosis and treatment. AH1 was also the most prescribed drug (74.5%) including 1st generation (6.9%), 2nd generation (81%), and both generations (12.1%). More than half of respondents with SD (59.3%) and SimD (65.6%) took medications regularly. The median treatment duration was 1 year for both groups. For treatment outcomes, the majority of respondents with SD (43.1%) and SimD (62.5%) an improvement of symptoms without recurrence after stop medication. Approximately 15.3% of respondents reported side effects, including drowsiness, dry mouth, dizziness/headache, blurred vision, and constipation.

“Take OTC medicines and see the doctor for treatment” group (253 respondents)

In the earlier step to take OTC medicines, more than half of them took medications irregularly with the frequency of 1–3 days per week. AH1 was the most reported drug (91.7%) including 1st generation (20.3%), 2nd generation (71.1%), and both generations (8.6%). In the later stages, half of SD (54.5%) and SimD (58.1%) groups chose to consult dermatologists for diagnosis and treatment of dermographism. AH1 still were the most prescribed medicines (82%) including were 1st generation (17.1%), 2nd generation (68.3%), and both generations (14.6%). After consultants, the median treatment durations of SD and SimD groups were 1.5 and 1 year, respectively. For treatment outcomes, respondents with SD (46.4%) and SimD (54.8%) reported an improvement of symptoms without recurrence after stop medication. The side effects including drowsiness, dizziness/headache, dry mouth, blurred vision, and constipation in both SD and SimD respondents was not different between the earlier and later stages.

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study was performed as an internet-based survey to collect information about dermographism in Thai patients in terms of characteristics, associated factors, severity, and impact on quality of life and management, according to respondents’ experiences. The general findings on dermographism observed in this study were consistent with previous studies, including female predominance, median age of onset, health status, history of atopy, and concomitant chronic spontaneous urticaria [5,7,12,14]. The median onset age of dermographism in this study was 16, which was similar to previous reports which showed onset of dermographism was more common in younger people [6,7,15]. Half of the respondents had dermographism at the time of responding to the questionnaire. The severity of dermographism in the SD group was greater than in the SimD group.

The association between dermographism and atopy is still controversial [15,16]. In 2010, Uthaisangsook [17] reported prevalence of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and asthma in Thai university students to be 47.0%, 20.3%, and 11.6%, respectively. In 2015, Sapsaprang et al. reported the prevalence of allergic rhinitis in Thai university students was 58.5% [18]. However, there is no report on the prevalence of allergic conjunctivitis in the Thai population. When compared to the general population, this study implies an increase only in the prevalence of atopic dermatitis in dermographism (32.5%), while allergic rhinitis and asthma in individuals with dermographism is similar to the general population (44.1% and 4.0%, respectively). Our findings were consistent with a recent study in China which reported a high percentage of atopic dermatitis (21.1%) in SD patients [15]. Body weight, body mass index, and cardiovascular diseases were significantly higher in the SD group than SimD group in the present study, which had also not been previously described. Although cardiovascular diseases in this study were associated with dermographism, a true association requires further studies. A metabolic syndrome may relate to pro-inflammatory cytokines including histamine release; however, the evidence is inconclusive [19]. Only 2.3% of respondents with dermographism in this study reported concomitant thyroid diseases, which is similar to the 1.5%–2% observed in previous reports [6,15].

Referring to previous studies, there was information about patients who had familial dermographism [3,20]. Jedele and Michels [3] reported an autosomal dominance inheritance pattern of dermographism in 4 generations of one family. Schoepke et al. [12] reported 14% of patients with SD had family history of dermographism, which was consistent with 20% of respondents observed in this study. There are 2 possible explanations for this finding. First, the prevalence of dermographism appears to be more than expected in the general population and it might occur by chance in family members. Second, patients with familial dermographism might have only mild symptoms and hence do not seek medical care [3]. Hence, the frequency of familial dermographism might be an area to look into.

Stress was mentioned as an aggravating factor that provoked dermographism in previous reports [4,6,13,20]. Interestingly, some respondents in the present study also reported menstruation as another aggravating factor for dermographism, although the association of hormonal changes and dermographism has not been described. One possible explanation for this finding was that menstruation might cause stress in women [21,22]. However, a previous study reported that acute psychosocial stress did not alter the magnitude of demographic reactions [13]. Therefore, the effect of stress on dermographism flare-ups remains uncertain.

The majority of respondents with SD and SimD let the dermographism resolve on its own. However, approximately 26% of respondents took medicines on their own depending on severity of symptoms. Some SD respondents visited a doctor to manage dermographism. The median time from occurrence to disappearance of dermographism in the SD group was 2-fold longer than the SimD group, which could be explained by the fact itch symptom provoked repetitive scratches on skin lesion in SD, resulting in a prolonged period of dermographism [8].

There were several limitations of this study. An internet-based survey may have a selection bias for middle-aged respondents than other age groups. Another bias was that the higher level of socioeconomic status and education, the higher participation was possible. Additionally, no diagnostic tests were performed to confirm if respondents with dermographism really had it. Less than half of respondents filled the details of treatment including types and doses of medication. The information of skin care usage was not contained in this questionnaire. Moreover, the questionnaire was designed to collect details of respondents who had dermographism, so the prevalence in the entire population could not be determined. Thus, further studies should be conducted to determine prevalence of confirmed cases of dermographism in different geographic areas.

This study is interesting and provide some insight about patient's perception of dermographism. However, about the treatment aspect, mostly, less than half of responders in each group know the name of their medicine. Dosage of medicine used is not included in the result. These limitations about treatment aspect should be included in the discussion about treatment effects. Limitation from not including the skin care activity should also be discussed.

In conclusion, this survey highlights several aspects of dermographism for healthcare providers. Dermographism can occur at any age and can even persist in adults. SD is more troublesome than SimD and it affects the quality of life of patients, leading some sufferers to seek medication and medical care from a physician. Therefore, physicians should be aware that education about dermographism in the general population, including appropriate management, is important.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Chalermphrakiat Grant from the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. We gratefully acknowledge the help of Mr Suthipol Udompunturak, M.Sc. for his assistance in data analysis and statistical support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Chuda Rujitharanawong, Papapit Tuchinda, Leena Chularojanamontri, Visanu Thamlikitkul, Kanokvalai Kulthanan.

- Formal analysis: Chuda Rujitharanawong, Papapit Tuchinda, Leena Chularojanamontri, Visanu Thamlikitkul, Kanokvalai Kulthanan.

- Investigation: Chuda Rujitharanawong, Papapit Tuchinda, Leena Chularojanamontri, Kanokvalai Kulthanan.

- Methodology: Visanu Thamlikitkul, Kanokvalai Kulthanan.

- Project administration: Chuda Rujitharanawong, Yanisorn Nanchaipruek, Kanokvalai Kulthanan.

- Writing - original draft: Chuda Rujitharanawong, Yanisorn Nanchaipruek.

- Writing - review & editing: Visanu Thamlikitkul, Kanokvalai Kulthanan.

References

- 1.Magerl M, Altrichter S, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, Grattan CE, Lawlor F, Mathelier-Fusade P, Meshkova RY, Zuberbier T, Metz M, Maurer M. The definition, diagnostic testing, and management of chronic inducible urticarias - The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus recommendations 2016 update and revision. Allergy. 2016;71:780–802. doi: 10.1111/all.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casale TB, Sampson HA, Hanifin J, Kaplan AP, Kulczycki A, Lawrence ID, Lemanske RF, Levine MI, Lillie MA. Guide to physical urticarias. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;82:758–763. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jedele KB, Michels VV. Familial dermographism. Am J Med Genet. 1991;39:201–203. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320390216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathews KP. Urticaria and angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;72:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontou-Fili K, Borici-Mazi R, Kapp A, Matjevic LJ, Mitchel FB. Physical urticaria: classification and diagnostic guidelines. An EAACI position paper. Allergy. 1997;52:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breathnach SM, Allen R, Ward AM, Greaves MW. Symptomatic dermographism: natural history, clinical features laboratory investigations and response to therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:463–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1983.tb01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirby JD, Matthews CN, James J, Duncan EH, Warin RP. The incidence and other aspects of factitious wealing (dermographism) Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong RC, Fairley JA, Ellis CN. Dermographism: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:643–652. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azkur D, Civelek E, Toyran M, Mısırlıoğlu ED, Erkoçoğlu M, Kaya A, Vezir E, Giniş T, Akan A, Kocabaş CN. Clinical and etiologic evaluation of the children with chronic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37:450–457. doi: 10.2500/aap.2016.37.4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Abdul Latiff AH, Baker D, Ballmer-Weber B, Bernstein JA, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brzoza Z, Buense Bedrikow R, Canonica GW, Church MK, Craig T, Danilycheva IV, Dressler C, Ensina LF, Giménez-Arnau A, Godse K, Gonçalo M, Grattan C, Hebert J, Hide M, Kaplan A, Kapp A, Katelaris CH, Kocatürk E, Kulthanan K, Larenas-Linnemann D, Leslie TA, Magerl M, Mathelier-Fusade P, Meshkova RY, Metz M, Nast A, Nettis E, Oude-Elberink H, Rosumeck S, Saini SS, Sánchez-Borges M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Staubach P, Sussman G, Toubi E, Vena GA, Vestergaard C, Wedi B, Werner RN, Zhao Z, Maurer M. Endorsed by the following societies: AAAAI, AAD, AAIITO, ACAAI, AEDV, APAAACI, ASBAI, ASCIA, BAD, BSACI, CDA, CMICA, CSACI, DDG, DDS, DGAKI, DSA, DST, EAACI, EIAS, EDF, EMBRN, ESCD, GA2LEN, IAACI, IADVL, JDA, NVvA, MSAI, ÖGDV, PSA, RAACI, SBD, SFD, SGAI, SGDV, SIAAIC, SIDeMaST, SPDV, TSD, UNBB, UNEV and WAO. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73:1393–1414. doi: 10.1111/all.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bart RS, Ackerman AB. Urticarial dermographism. Report of occurrence in identical twins: a method for quantitating urticarial skin sensitivity. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:716–719. doi: 10.1001/archderm.94.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoepke N, Młynek A, Weller K, Church MK, Maurer M. Symptomatic dermographism: an inadequately described disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:708–712. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallengren J, Isaksson A. Urticarial dermographism: clinical features and response to psychosocial stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:493–498. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sánchez-Borges M, González-Aveledo L, Caballero-Fonseca F, Capriles-Hulett A. Review of physical urticarias and testing methods. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:51. doi: 10.1007/s11882-017-0722-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L, Wang X, Wang W, Wang B, Li L. Symptomatic dermographism in Chinese population: an epidemiological study of hospital-based multicenter questionnaire survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38:131–137. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1984220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taşkapan O, Harmanyeri Y. Evaluation of patients with symptomatic dermographism. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uthaisangsook S. Risk factors for development of asthma in Thai adults in Phitsanulok: a university-based study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2010;28:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapsaprang S, Setabutr D, Kulalert P, Temboonnark P, Poachanukoon O. Evaluating the impact of allergic rhinitis on quality of life among Thai students. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:801–807. doi: 10.1002/alr.21540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Shi GP. Mast cells and metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston TG, Cazort AG. Dermographia; clinical observations. J Am Med Assoc. 1959;169:23–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.1959.03000180025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deligeoroglou E, Creatsas G. Menstrual disorders. Endocr Dev. 2012;22:160–170. doi: 10.1159/000331697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y, Im EO. Stress and premenstrual symptoms in reproductive-aged women. Health Care Women Int. 2016;37:646–670. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2015.1049352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reich A, Heisig M, Phan NQ, Taneda K, Takamori K, Takeuchi S, Furue M, Blome C, Augustin M, Ständer S, Szepietowski JC. Visual analogue scale: evaluation of the instrument for the assessment of pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:497–501. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]