Abstract

Patients recovered from COVID-19 may develop long-COVID symptoms in the lung. For this patient population (post-COVID patients), they may benefit from longitudinal, radiation-free lung MRI exams for monitoring lung lesion development and progression. The purpose of this study was to investigate the performance of a spiral ultrashort echo time MRI sequence (Spiral-VIBE-UTE) in a cohort of post-COVID patients in comparison with CT and to compare image quality obtained using different spiral MRI acquisition protocols. Lung MRI was performed in 36 post-COVID patients with different acquisition protocols, including different spiral sampling reordering schemes (line in partition or partition in line) and different breath-hold positions (inspiration or expiration). Three experienced chest radiologists independently scored all the MR images for different pulmonary structures. Lung MR images from spiral acquisition protocol that received the highest image quality scores were also compared against corresponding CT images in 27 patients for evaluating diagnostic image quality and lesion identification. Spiral-VIBE-UTE MRI acquired with the line in partition reordering scheme in an inspiratory breath-holding position achieved the highest image quality scores (score range = 2.17–3.69) compared to others (score range = 1.7–3.29). Compared to corresponding chest CT images, three readers found that 81.5% (22 out of 27), 81.5% (22 out of 27) and 37% (10 out of 27) of the MR images were useful, respectively. Meanwhile, they all agreed that MRI could identify significant lesions in the lungs. The Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence allows for fast imaging of the lung in a single breath hold. It could be a valuable tool for lung imaging without radiation and could provide great value for managing different lung diseases including assessment of post-COVID lesions.

Keywords: MRI, Spiral sampling, Stack-of-spirals, Ultrashort echo time, COVID-19, Post-COVID, Lung imaging

1. Introduction

The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the SARS-CoV-2 viruses, has presented an unprecedented crisis and challenge to public health. Until July 2022, over 500 million COVID-19 cases have been reported globally [1]. Although most people infected with COVID-19 experience mild to moderate symptoms without the need for hospitalization and specific treatments, some people could become severely sick and require medical attention. In the meantime, even with mild disease outcome, many patients may develop long COVID symptoms, a post-COVID syndrome associated with certain chronic symptoms and damage in the lung as well as other organs such as the brain and/or the heart [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]. Indeed, long COVID has emerged as an ongoing healthcare challenge requiring more attention and careful investigation [4]. This will ensure that the long-term outcomes of post-COVID patients, including residual damage in the lung and other organs, can be studied, better understood and properly managed.

It has been a consensus that the lung is one of the first organs the SARS-CoV-2 viruses attack in severely sick patients [10]. As a result, proper screening and management of anatomical and functional sequelae of COVID-19 in the lung has been a pressing clinical need. Currently, Computed Tomography (CT) is the most commonly used imaging modality for assessment of lung anatomy, and it has been used in post-COVID patients in many research studies [11]. CT offers excellent morphologic information, but the need of ionizing radiation has been a major concern that restricts frequent exams for studying the longitudinal change of lung structure [12], especially in the post-COVID patient cohort. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) represents a promising radiation-free imaging modality for lung imaging in post-COVID care. Although MRI is not traditionally used for imaging the lung, recent advances in MRI technology have made this possible both in the research and clinical settings [[13], [14], [15]]. For example, MRI with ultra-short echo time acquisition (UTE-MRI) has enabled visualization of short T2* structures in the lung, as demonstrated in many studies [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]]. This provides a new opportunity for longitudinal screening of lung structure abnormality such as ground-glass opacity and fibrotic-like changes, making MRI well-suited for post-COVID management [28].

Conventional UTE-MRI is typically implemented based on a center-out 3D radial trajectory or its variants [18,29,30]. This allows for radio frequency (RF) excitation using a non-selective pulse and immediate data acquisition following RF excitation without the need for slice/slab selection, both of which are important to ensure minimum echo time. However, limitations associated with the center-out 3D radial trajectory include reduced imaging efficiency and prolonged scan time due to center-out half-echo sampling, the requirement for isotropic spatial resolution resulting in reduced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and high computational burden due to large data size. Meanwhile, due to long scan time, free-breathing acquisition is normally necessary for UTE-MRI with center-out 3D radial sampling [17,18,31,32], which in turn requires reliable motion compensation methods to manage respiratory motion.

Recently, a new UTE-MRI sequence, called Spiral-VIBE-UTE, has been proposed for more efficient lung imaging [33,34]. Here, VIBE, standing for Volumetric Interpolated Breath-hold Examination, is a Siemens acronym for 3D breath-hold gradient echo (GRE) sequences. The Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence includes several new components. First, it employs center-out spiral sampling, which provides more flexibility to design longer readout to compensate for the reduced scan efficiency in traditional UTE-MRI. Second, Spiral-VIBE-UTE implements a stack-of-spirals trajectory, where spiral sampling is applied in the kx-ky plane and Cartesian sampling is applied along the kz dimension (slice direction). Compared to the 3D radial trajectory, this provides flexibility to perform imaging with anisotropic spatial resolution and volumetric coverage, enabling faster imaging speed to acquire a 3D image of the lung. To date, Spiral-VIBE-UTE has been applied for both anatomical imaging and functional imaging in the lung [[35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]], but to the best of our knowledge, it has not been tested in post-COVID patients yet.

The purpose of this study includes the following three aspects. First, we aimed to study the performance of Spiral-VIBE-UTE for imaging pulmonary structure in post-COVID patients and to compare its performance against corresponding CT references. Second, since stack-of-spirals sampling can be performed with either a partition-in-line looping scheme or a line-in-partition looping scheme (referred to as reordering, see the Method section below for more details), it remains unclear which reordering scheme would give better performance in lung imaging, especially in the presence of cardiac motion and/or residual respiratory motion (e.g., when a breath hold is not successful). Thus, it is important to investigate the resulting image quality of different acquisition schemes for in-vivo lung imaging. Third, we also sought to compare image quality acquired in an expiratory breath-hold position and an inspiratory breath-hold position in Spiral-VIBE-UTE imaging. This study is expected to have both technical and clinical significance. From the technical perspective, the results of this study will provide more guidance to use this relatively new sequence for breath-hold lung imaging. From the clinical perspective, this study will provide initial evidences to show the feasibility of Spiral-VIBE-UTE MRI for post-COVID management in comparison with CT, which could potentially enable longitudinal imaging studies in this patient population for better understanding of disease development.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence

2.1.1. UTE-MRI Acquisition based on stack-of-spirals sampling

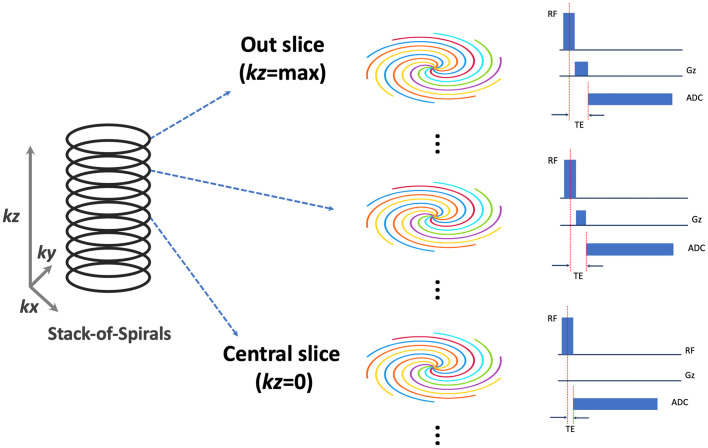

The Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence implements a hybrid stack-of-spirals sampling trajectory, as previously described by Mugler et al. [33,34]. As shown in Fig. 1 , spiral sampling is employed in the kx-ky plane for the Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence while Cartesian sampling is implemented along the kz direction. For the kx-ky plane, each spiral interleaf rotates by a linear angle (360o/total number of spiral interleaves) from the previous interleaf. In the kz direction, all spiral interleaves corresponding to different slice locations maintain the same rotation angle. To achieve ultra-short echo time (TE), the sequence has the following three features. First, non-selective RF excitation is employed in the sequence to shorten the duration of the RF pulse. Second, variable TE is implemented for difference image slices [42], as shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, the minimum TE is achieved for the central slice where the slice-encoding gradient is not enabled (kz = 0, see Fig. 1). While the slice-encoding gradient gets stronger towards outer slices, the TE is also increased and it reaches the maximum for the first outer slice (kz = +max/−max, see Fig. 1). Since the central slice primarily determines the image contrast in 3D imaging, this unique sampling scheme ensures that the overall 3D acquisition can have ultra-short TE when the central slice has the minimum TE. Third, center-out spiral sampling is implemented for data acquisition, which helps reduce the TE and enables increased sampling efficiency. Other advantages of Spiral-VIBE-UTE over traditional UTE-MRI based on 3D radial sampling include the flexibility to choose a slice thickness that is different from in-plane spatial resolution for better managing scan time and SNR, which allows for 3D lung UTE-MRI within a single breath hold.

Fig. 1.

The stack-of-spirals are acquired in the kx-ky plane and every slice maintains the same number of spiral interleaves rotating by a pre-defined angle. The ultra-short echo time (TE) is achieved by shortening the duration of the RF pulse, varying TE for different image slices (with minimum TE at kz = 0) and center-out spiral sampling during data acquisition.

2.1.2. Sampling reordering in spiral-VIBE-UTE MRI

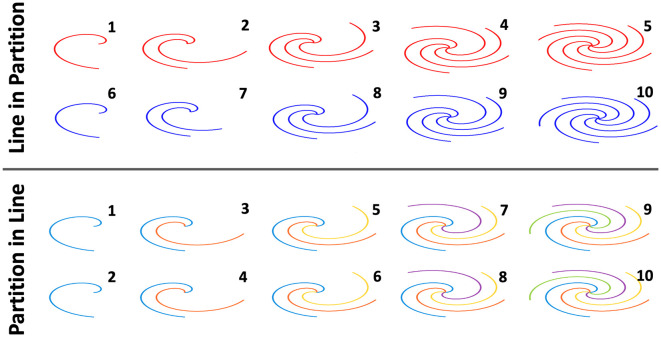

The stack-of-spirals sampling trajectory provides additional flexibility to design how one can acquire a 3D UTE-MR image. As shown in Fig. 2 for a simple example to acquire a stack-of-spirals dataset with two slices and 5 spiral interleaves in each slice, data acquisition can be performed in a line in partition loop (referred to as Lin-in-Par reordering hereafter) or a partition in line loop (referred to as Par-in-Lin reordering hereafter). For Lin-in-Par reordering, all spiral interleaves are acquired for one slice before moving to the next slice, while for Par-in-Lin reordering, a spiral interleaf with the same rotation angle in all slices (referred to as a spiral stack) are acquired before moving to the next stack. The order of acquisition is labelled in Fig. 2 from 1 to 10 for acquiring the total 10 spiral interleaves. In this study, it was hypothesized that imaging with different reordering schemes can lead to different imaging performance, and therefore, image quality from these two reordering schemes was compared for lung imaging.

Fig. 2.

Different reordering schemes can be implemented in stack-of-spirals acquisition including line in partition (Lin-in-Par) reordering and partition in line (Par-in-Lin) scheme. For Lin-in-Par reordering, all spiral interleaves are acquired for one slice before moving to the next slice, while for Par-in-Line reordering, a spiral interleaf with the same rotation angle in all slices are acquired before moving to the next stack. The order of acquisition is labelled from 1 to 10 for acquiring the total 10 spiral interleaves.

2.2. Post-COVID patient recruitment

A total of 36 adult post-COVID patients (20 males, 16 females, mean age = 44.6 ± 14.6 years) who had previously recovered from COVID-19 infection were recruited for this study. All the recruited patients had previously been tested positive for COVID-19 either with a PCR test or an antigen test. Patients were referred from the outpatient clinics at our hospital between December 2020 and September 2021. Other inclusion and exclusion criteria for the recruitment were: age > 18; no COVID-19 infection and symptoms at the time of MRI exams (self-reporting); no significant medical illness; no implanted metal devices; no tattoos larger than one centimeter in diameter or tattoos with metallic ink; no claustrophobia; no pregnancy; no breast feeding; no significant lung disease history. We did not set a restriction on the time between COVID-19 infection and the MRI/CT scan. The study was HIPAA compliant and was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Written consents were obtained from all participants prior to the MRI scan. In addition, a healthy volunteer (male, 59-year-old) without COVID-19 history was also recruited to participate in the study. The main purpose of the volunteer imaging was to compare image quality between different acquisition schemes while successful breath holding can be ensured.

2.3. Data acquisition

2.3.1. MRI acquisition

For each subject, Spiral-VIBE-UTE imaging was performed using a prototype stack-of-spirals UTE sequence for four different scans, including Spiral-VIBE-UTE imaging with the Lin-in-Par reordering scheme performed in both expiratory and inspiratory breath-holding positions (referred to as Spiral-Exp Lin-in-Par and Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par, respectively), and Spiral-VIBE-UTE imaging with the Par-in-Lin reordering scheme performed in both expiratory and inspiratory breath-holding positions (referred to as Spiral-Exp Par-in-Lin and Spiral-Insp Par-in-Lin, respectively). Relevant imaging parameters were: non-selective excitation, FOV = 480x480mm2, spatial resolution = 2.1 × 2.1mm2, slice thickness = 2.5 mm, total number of slices = 96, TR = 2.65 ms, TE = 0.05–0.27 ms from the central slice to the outer slice, flip angle = 5o, spiral readout duration = 1160us, RF pulse duration = 60us, number of spiral interleaves for each slice = 140. In data acquisition, 48 slices were acquired with a slice thickness of 5 mm (half of the slice resolution set in the scanner), and zero-filling was performed along the slice dimension to generate all the 96 slices with a slice thickness of 2.5 mm. As a result, a total of four MRI scans were performed in each subject in four separate breath holds. Imaging was performed in the coronal orientation. Uniform spiral density was implemented. All images were fully sampled to achieve the Nyquist rate and images were reconstructed directly on the scanner using a standard gridding algorithm. For comparison, 3D breath-hold Cartesian imaging using a clinical VIBE sequence was also performed in the volunteer. All MRI scans were performed on a 3 T clinical scanner (MAGNETOM Biograph mMR, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany).

The healthy volunteer without COVID-19 history underwent the same breath-hold scans as the post-COVID patients. In addition, two 3D Cartesian scans were also performed using a clinically available 3D gradient echo (GRE) sequence, one in an expiratory breath-holding position and the other in an inspiratory breath-holding position. Relevant imaging parameters were similar to the spiral scans. The volunteer confirmed that all imaging tasks were performed under successful breath holds. For comparison purpose, all these scans were also repeated during free breathing in the volunteer.

2.3.2. CT acquisition

Among the 36 recruited post-COVID patients, 27 patients also underwent chest CT scan as part of an on-going COVID-19 research study at our hospital. Chest CT imaging was performed on a Siemens SOMATOM Force dual-energy CT scanner following standard clinical protocols with a matrix size of 512 × 512, in-plane spatial resolution of 0.68 × 0.68mm2 and a slice thickness of 3 mm. All CT scans were performed in the coronal orientation in an inspiratory breath-holding position as implemented in the clinic.

2.4. Image assessment

All images were evaluated to compare overall image quality for different MRI acquisition protocols and diagnostic quality between MRI and CT. A web-based DICOM viewer (Discovery Viewer referred as DV hereafter) was developed to review and score the images. The readers were allowed to access the tool from any modern browser as long as they were connected to the internal network. The readers can sign in anytime for the assessment with a registration system and can resume any incomplete progress. The DV included tools for scrolling, windowing and drawing for efficient assessment of images. All the results were stored locally in an internal server for analysis.

2.4.1. Comparison of MRI protocols

Visual image quality assessment was performed to evaluate the MR images acquired with four different protocols. Specifically, images were evaluated for large arteries, large airways, segmental arteries, segmental broncho vascular structures, sub-segmental vessels, and overall motion artifacts (from cardiac motion and/or residual respiratory motion). All images were pooled and randomized for blind assessment by three chest radiologists who read both chest CT and MR images in their daily routine clinical work at the Mount Sinai hospital with 11 years (A.J., reader 1), 6 years (A.B., reader 2) and 5 years (M.C., reader 3) of clinical experiences. Three readers independently scored the images based on a 5–1 scale, where 5 to 1 indicates the best image quality to the worst or the most artifacts to the least. The results were summarized for each assessment category as mean ± standard deviation. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used to evaluate the difference between different acquisition protocols, where a P value smaller than 0.05 indicates statistical significance. Inter-reader variability was assessed using the Bland-Altman analysis.

2.4.2. Comparison between MRI and CT

For the comparison between MRI and CT, all the three readers who performed the image quality assessment for MRI also evaluated the diagnostic quality of all paired MR and CT images independently. Here, from all the spiral MRI acquisition protocols, only MR images acquired with the protocol that received the highest image quality score were used for the comparison. Specifically, the readers assessed the confidence of using lung MR images for potential clinical use in comparison with corresponding CT images, indicating whether the diagnostic quality of MR images was “non-diagnostic”, “acceptable but worse than CT”, or “similar to CT”. In addition, the same reader evaluated whether the post-COVID lung lesions observed in the CT images (if they exist) could also be identified in corresponding MR images.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Among all the 36 post-COVID patients, 7 patients were hospitalized for COVID-related symptoms and the average time stayed at the hospital was 10.16 ± 5.4 days. Three of the 7 patients who were in the hospital also stayed in the intensive care unit (ICU) during the acute COVID phase (the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection). The average time between the COVID acute phase and the MRI scans was 243 ± 133 days. Among all the 27 patients who had chest CT scans. 8 patients had the CT exam after the MRI exam and 19 patients had the CT exam before the MRI exam. The time between the COVID acute phase and the CT imaging was 223 ± 146 days, and the average time between the CT and MRI scans was 43 ± 80 days.

3.2. Comparison of MRI protocols

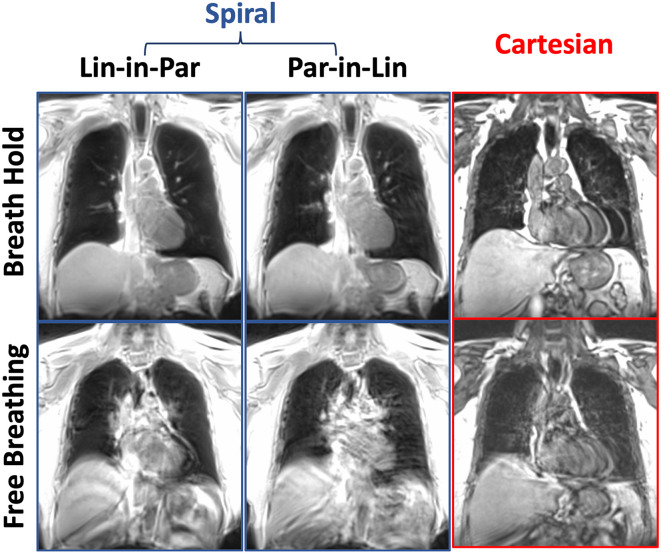

Comparisons of lung MR images acquired with different spiral protocols in the healthy volunteer are presented in Fig. 3 . For the breath-hold spiral images, the Lin-in-Par reordering yielded better image quality than the Par-in-Lin reordering, where residual motion artifacts were observed in the image acquired with Par-in-Lin reordering. Since the volunteer confirmed successful breath holds, the motion artifacts are likely caused by cardiac motion. Corresponding breath-hold Cartesian image also produced clear ghosting artifacts due to cardiac motion. For free-breathing acquisitions, all images show strong motion artifacts from both respiratory and cardiac motion. This initial comparison suggested that Spiral-VIBE-UTE imaging with the Lin-in-Par reordering is more reliable and more robust to motion.

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of lung MR images acquired with different spiral protocols in the healthy volunteer. For the breath-hold spiral images, the Lin-in-Par reordering yielded better image quality than the Par-in-Lin reordering. Corresponding breath-hold Cartesian image also produced clear ghosting artifacts due to cardiac motion. For free-breathing acquisitions, all images show strong motion artifacts from both respiratory and cardiac motion.

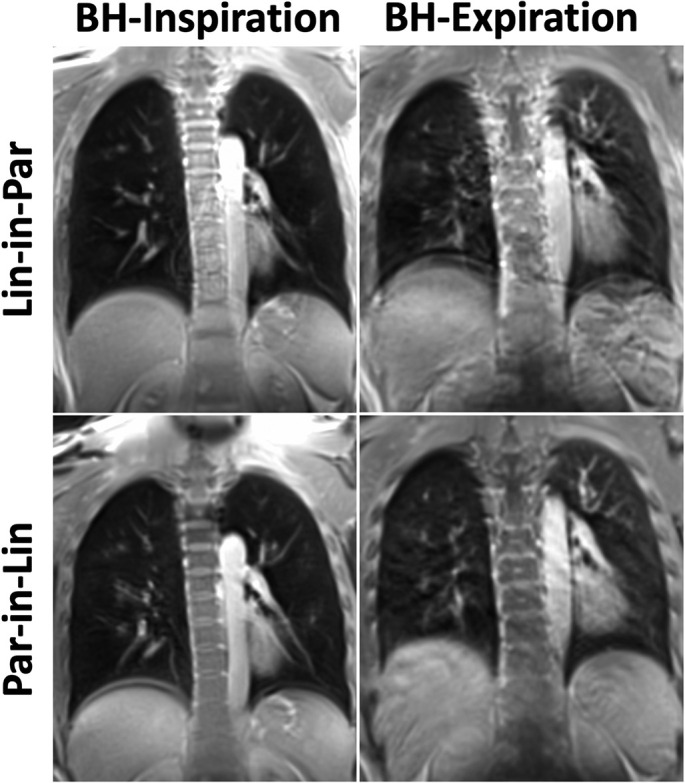

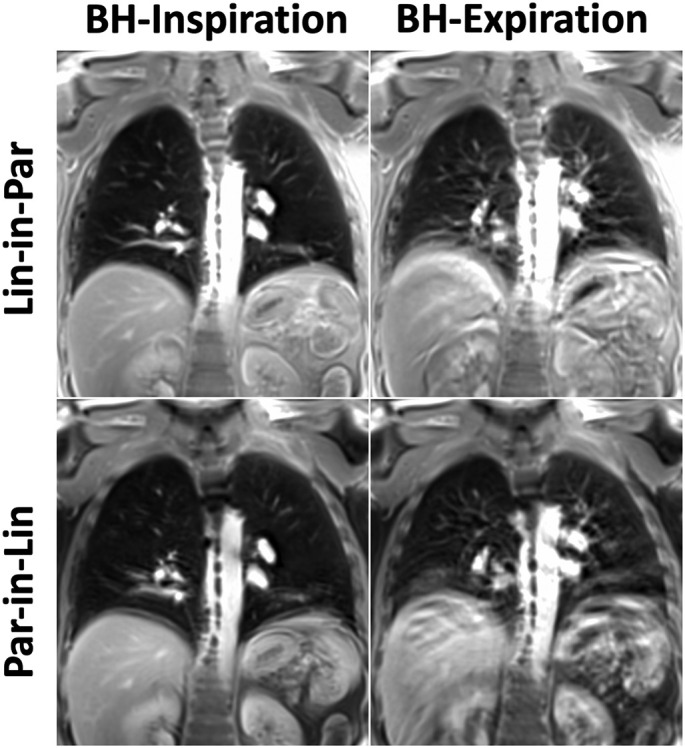

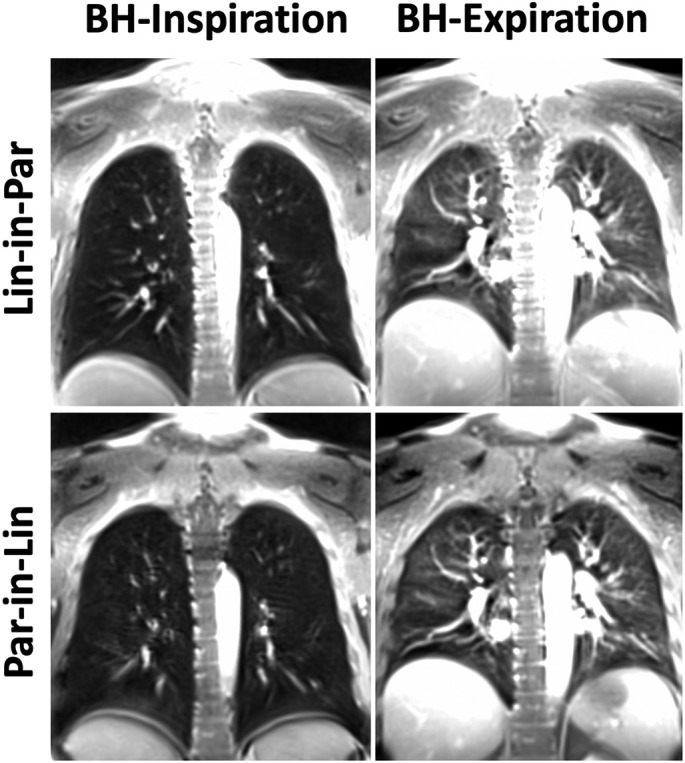

Comparisons of spiral lung MR images acquired with different reordering schemes and breath-hold positions are shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 for three post-COVID patients. For all the comparisons, Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par consistently yielded better image quality and less artifacts than others. Meanwhile, spiral images acquired in an expiratory breath-holding position yielded lower image quality regardless of the reordering scheme. This is likely due to the increased difficulty to hold the breath in an expiratory position.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of different spiral lung MR acquisition protocols in the first representative post-COVID patient.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of different spiral lung MR acquisition protocols in the second representative post-COVID patient.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of different spiral lung MR acquisition protocols in the third representative post-COVID patient.

The average scores from the three readers for all the 36 post-COVID patients are summarized in Table 1 for different acquisition protocols and different assessment categories. Overall, Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par achieved the best image quality compared to others. Specifically, Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par received significantly better scores than Spiral-Exp Lin-in-Par and Spiral-Exp Par-in-Lin in all the assessment categories. Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par received significantly better scores than Spiral-Insp Par-in-Lin for assessment of large arteries, segmental arteries and the artifact level. While Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par also received higher scores than Spiral-Insp Par-in-Lin for assessment of large airways, segmental broncho vascular structures and sub-segmental vessels, the differences did not reach significance. The results for the inter-reader variability assessed using the Bland-Altman analysis are presented in the supplementary figures (Fig. S1 to Fig. S3) in supporting information. The offset towards 1 for Figs. S1 and S2 shows a mean bias greater for reader 1 compared to readers 2 and 3. Fig. S3 shows a strong agreement between readers 2 and 3 with a skewness of the data towards the lower bound.

Table 1.

Average scores and statistical tests for all image quality metric. The average scores include all three readers and the 36 post-COVID patients. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to identify statistical significance between different acquisition protocols and assessment categories.

| Spiral Inspiration Lin-in-Par (1) | Spiral Expiration Lin-in-Par (2) | Spiral Inspiration Par-in-Lin (3) | Spiral Expiration Par-in-Lin (4) | 1 vs. 2, 4 | 1 vs. 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Arteries Score | 3.69 ± 0.41 | 3.29 ± 066 | 3.19 ± 0.44 | 3.11 ± 0.7 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

| Large Airways Score | 3.56 ± 0.45 | 3 ± 0.69 | 3.57 ± 0.44 | 2.99 ± 0.65 | P < 0.05 | 0.07 |

| sSegmental Arteries Score | 2.97 ± 0.48 | 2.47 ± 0.6 | 2.58 ± 0.5 | 2.28 ± 0.54 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

| Segmental Broncho vascular Structures Score | 2.52 ± 0.49 | 2 ± 0.55 | 2.28 ± 0.56 | 1.9 ± 0.57 | P < 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Sub-segmental Vessels Score | 2.17 ± 0.38 | 1.77 ± 0.44 | 2 ± 0.45 | 1.7 ± 0.44 | P < 0.05 | 0.65 |

| Artifact Level Score | 2.54 ± 0.44 | 3.1 ± 0.62 | 3 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.66 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

3.3. Comparison between MRI and CT

The Spiral-Insp Lin-in-Par lung MR images were used for comparison with CT since it received the best image quality scores. Here, a total of 27 cases were used for the comparison. For reader 1, 22 MRI cases (81.5%) were found to be useful (17 cases had similar diagnostic quality as CT and 5 cases were acceptable) while the rest 5 were found not useful. For reader 2, 22 MRI cases (81.5%) were found to be useful (one cases had similar diagnostic quality as CT and 21 cases were acceptable) while the rest 5 were found not useful. For reader 3, only 10 MRI cases (37%) were found to be useful (none had similar diagnostic quality as CT but all the 10 cases were acceptable) while the rest 17 were found not useful.

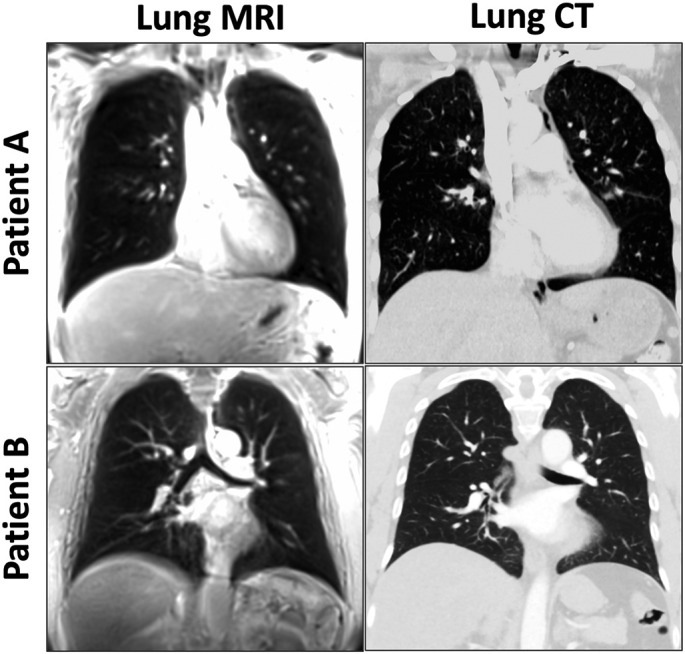

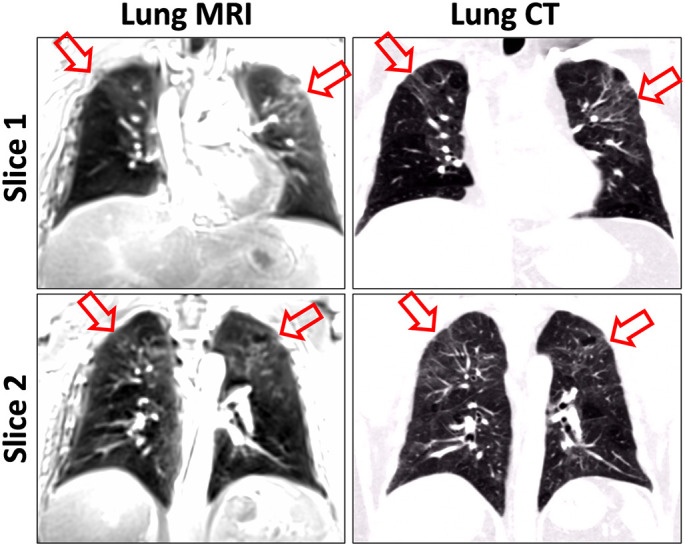

Comparison of chest CT and lung MR images in two representative post-COVID patients without COVID-related lesions is shown in Fig. 7 . Lung lesions were found in 4 cases by reader 1, 7 cases by reader 2, and 3 cases by reader 3. In particular, substantial lung opacities were found in one case, as shown in Fig. 8 for two representative slices. The ground glass opacities observed in CT (red arrows) can be clearly delineated in MRI as well. For this case, the CT images were acquired on 01/25/2021 while the MR images were acquired on 05/20/2021. During the acute COVID phase, this patient was hospitalized for 14 days and was also admitted to ICU. All the readers agreed that MRI was useful for identifying the lesions in this case.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of chest CT and lung MR images in two representative post-COVID patients without COVID-related lesions.

Fig. 8.

Comparison between CT and MR images in a post-COVID patient with COVID-related lesions. According to the expert chest radiologist, the MR images have a similar diagnostic quality compared to CT for this case. The ground glass opacities (red arrows) can be clearly observed both in CT and MRI. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

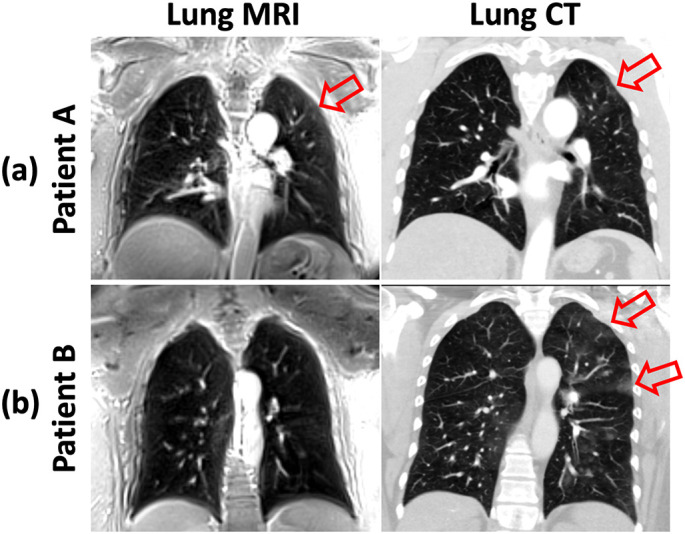

Fig. 9a shows another case with lung lesions identified in CT images. Subacute ground glass opacities can be seen in the left lung in CT (red arrows) and it can also be identified in MRI. For this case, MR images were found to have acceptable diagnostic quality (but worse than CT) by reader 1 and reader 3, but not reader 3. The CT images were acquired on 02/18/2021 while the MR images were acquired on 02/25/2021. Fig. 9b shows the third case with lung lesions identified in CT images. For this case, all readers could not find lesions in MR images. The CT images were acquired on 05/03/2020 while the MR images were acquired on 04/19/2021, and this large gap in time (∼1 year) likely explains why the lesions were not observable on the MRI.

Fig. 9.

Diagnostic quality comparison between CT and MRI for two post-COVID patients with COVID related lesions in the lungs. (a) For the first patient (Patient A), acceptable diagnostic quality according to the expert chest radiologist. Subacute ground glass opacities (red arrows) observed in the left lung in CT can also be identified in MRI. (b) For the second patient (Patient B), MR images are not useful according to the expert chest radiologist. Ground glass opacities (red arrows) observed in the left lung in CT are not identifiable in the MR images. The big gap in time between the CT and MRI exams (∼1 year) may explain why the lesions were not observable on the MRI. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

In this work, we tested the performance of the Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence for breath-hold lung images in a cohort of post-COVID patients. As the technical aspect, we investigated the imaging performance using different reordering schemes in stack-of-spirals acquisition and also compared image quality in lung images acquired in different breath-holding positions. As the clinical aspect, we have evaluated the diagnostic performance of spiral UTE MRI for assessment of the lung in comparison with CT. Our results have suggested that spiral UTE MRI with the Lin-in-Par reordering performed in an inspiratory breath-holding position ensures the best image quality, and this sequence could be potentially useful for fast lung imaging for longitudinal evaluation or screening purpose.

For the technical side, our results have shown that spiral UTE MRI using the Par-in-Lin reordering is more sensitive to motion compared to the Lin-in-Par reordering. Given the efficient k-space coverage with spiral k-space sampling, this is because motion (cardiac motion and/or residual respiratory motion due to failed breath holds) is mainly present along the slice direction (kz) with Lin-in-Par reordering, while in-plane (kx-ky) motion artifacts can potentially be avoided. With Par-in-Lin reordering, however, motion is highly minimized along the slice direction and is mainly present in the kx-ky plane, making motion artifacts more noticeable. Variable-density spiral sampling might potentially increase the motion robustness, but it requires longer scan time to achieve Nyquist sampling, which might be more suited for free-breathing undersampled acquisition in combination with sparse reconstruction techniques. Meanwhile, free-breathing data acquisition can also benefit from golden-angle rotation [30,43,44], which could facilitate data sorting based on a respiratory motion signal and self-gated image reconstruction.

A constant sampling density was implemented in the spiral sampling in this work. This is because image acquisition was not accelerated in our lung MRI study and a standard gridding reconstruction was applied to generate lung MR images directly on the scanner. Therefore, a constant sampling density can ensure faster acquisition of a fully sampled images compared to variable-density spiral sampling. For accelerated data acquisition that requires more advanced image reconstruction (e.g., compressed sensing or deep learning), it is expected that variable-density spiral sampling can ensure better imaging performance.

In this study, we have also shown that breath-hold imaging in an inspiratory position is more reliable to ensure good image quality. This is expected because it is easier for a subject, especially a patient, to hold breath in the inspiratory position and this is also the acquisition protocol used in clinical CT exams. Based on these observation and investigation, it is suggested that the Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence is performed in an inspiratory position for breath-hold imaging with the Lin-in-Par reordering. We believe these investigations are important to guide other users who are interested in using this imaging sequence and translation of this new method into the clinic.

The capability of fast breath-hold imaging is one of the key advantages for the Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence. Different from traditional UTE sequences that are typically based on a 3D non-Cartesian sampling trajectory (e.g., center-out radial), using a hybrid Cartesian-spiral trajectory can provide much faster imaging speed, which ultimately ensures imaging of the whole lung within a single breath hold. In addition to breath-hold imaging, this sequence can also be performed during free breathing with self-gated acquisition, as recently shown by Javed et al. [45]. Spiral sampling also provides good incoherence for combination with different sparse reconstruction methods for acceleration of data acquisition. This sequence may also be combined with difference magnetization preparation pulses, such as the inversion recovery preparation [46], so that it can be used for MR parameter mapping in the lung.

From the clinical side, our results have shown a small incidence of post-COVID lesions in post-COVID patients. Due to the lack of radiation, spiral UTE MRI can offer a great opportunity to closely follow the evolution of post-COVID lung diseases in time for identifying lesions that could correspond to lung fibrosis, which is one of the most common side effects caused by COVID-19 [47]. The fast-imaging speed provided by the Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence is a key advantage to reduce the cost associated with MRI exams and increases its value and patient throughout. Despite the reduced image resolution compared to CT, our study has shown that spiral UTE MRI can still be useful, especially when major lung opacities are presented. For those cases where MR images are not useful, motion and limited spatial resolution could be two main reasons. Indeed, a breath hold duration of ∼16 s can still be long for patients, especially for those with reduced capacity and capability of breath holding. Therefore, additional acceleration of data acquisition with compressed sensing and/or deep learning would be important to further improve the performance of this imaging technique. In the meantime, the long gap between the MRI and CT scans in this study could also contribute to the discrepancy for evaluating the diagnostic quality.

We noticed that the results comparing MRI with CT vary among the three readers, especially between reader 3 and the other two. There are two main reasons that may contribute to this. First, reader studies often have inter-reader variation at different degrees, which is due to the nature of subjective assessment of image quality. In particular, the three readers who participated in this study have different levels of clinical experience. Second, lung MRI is not routinely performed in current clinical practice. Therefore, chest radiologists might be biased in assessing lung MR images, as they could be very used to the image quality provided by chest CT for clinical diagnosis. It is not expected that lung MRI will completely replace chest CT, but hopefully it could serve as a useful alternative as needed. The bottom line in this study is that all the three readers have agreed that MRI could identify major lesions that are seen in CT.

This study has several important limitations requiring discussion. First, we did not set any clinical criteria for patient recruitment. We recruited post-COVID patient regardless of their status during the infection phase. This could be the main reason why we did not see COVID-related lesions in most of the patients. In future studies, it is important to assess the quality of spiral UTE MRI in a target post-COVID patient group, so that its performance in post-COVID management can be further evaluated. Second, the primary objective of this feasibility study is to test the performance of spiral UTE MRI for imaging the lung in post-COVID patients. As a result, we did set a criterion on vaccination status for patient recruitment. It would be interesting to investigate the presence of COVID-related lesions between patients with vaccination and those without vaccination in future works. Third, the time between CT and MRI scans and the time between COVID-19 infection and MRI/CT scans varies substantially in our study. As a result, COVID-related lesions may not be present on both exams since the lesions may disappeared at the time of exams. Longitudinal MRI in a target patient cohort may be needed to further investigate and study the development of post-COVID lesions. Despite these limitations, our current study still demonstrated the initial feasibility and performance of spiral UTE MRI for managing post-COVID patients, and more importantly, it provides some useful guidance to other users who are interested in using this sequence to study post-COVID patients and other lung diseases.

5. Conclusion

The Spiral-VIBE-UTE sequence has been shown as a valuable tool for lung imaging without radiation. It enables fast imaging of the lung in a single breath hold and could provide great value for managing different lung diseases including assessment of post-COVID lesions. For breath-hold lung imaging, the Lin-in-Par reordering scheme during inspiratory data acquisition can ensure the best image quality.

Author statement

Valentin Fauveau: Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Formal Analysis, Software, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization.

Adam Jacobi: Formal Analysis, Investigation.

Adam Bernheim: Formal Analysis, Investigation.

Michael Chung: Formal Analysis, Investigation.

Thomas Benkert: Resources.

Zahi A Fayad: Methodology, Resources.

Li Feng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Investigation, Data Curation, Project Administration, Supervision.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Renata Pyzik for helping with patient recruitment, thank Dr. Yang Yang for helpful discussion and protocol installment, and thank Dr. Marco Pereanez for helping get chest CT images from the PACS. This study is supported by the NIH/NIBIB (R01EB031083).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2022.12.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.COVID-19 Map - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center 2022. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- 2.Milos R.I., Kifjak D., Heidinger B.H., Prayer F., Beer L., Röhrich S., et al. Morphological and functional sequelae after COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiologe. 2021;61:888–895. doi: 10.1007/S00117-021-00905-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subramanian A., Nirantharakumar K., Hughes S., Myles P., Williams T., Gokhale K.M., et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med. 2022 doi: 10.1038/S41591-022-01909-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koc H.C., Xiao J., Liu W., Li Y., Chen G. Long COVID and its management. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:4768–4780. doi: 10.7150/IJBS.75056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Sanchez I., Rodriguez-Mañas L., Laosa O. Long COVID-19: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Clin Geriatr Med. 2022:38. doi: 10.1016/J.CGER.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zazzara M.B., Bellieni A., Calvani R., Coelho-Junior H.J., Picca A., Marzetti E. Inflammaging at the time of COVID-19. Clin Geriatr Med. 2022:38. doi: 10.1016/J.CGER.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montes-Ibarra M., Oliveira C.L.P., Orsso C.E., Landi F., Marzetti E., Prado C.M. The impact of long COVID-19 on muscle health. Clin Geriatr Med. 2022:38. doi: 10.1016/J.CGER.2022.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauria A., Carfi A., Benvenuto F., Bramato G., Ciciarello F., Rocchi S., et al. Neuropsychological measures of long COVID-19 fog in older subjects. Clin Geriatr Med. 2022:38. doi: 10.1016/J.CGER.2022.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gyöngyösi M., Alcaide P., Asselbergs F.W., Brundel B.J.J.M., Camici G.G., da Costa Martins P., et al. Long COVID and the cardiovascular system - elucidating causes and cellular mechanisms in order to develop targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies: a joint scientific statement of the ESC Working Groups on Cellular Biology of the Heart and Myocardial & Pericardial Diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2022 doi: 10.1093/CVR/CVAC115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upadhya S., Rehman J., Malik A.B., Chen S. Mechanisms of lung injury induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Physiology. 2022;37:88–100. doi: 10.1152/PHYSIOL.00033.2021/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/PHYSIOL.00033.2021_F003.JPEG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe A., So M., Iwagami M., Fukunaga K., Takagi H., Kabata H., et al. One-year follow-up CT findings in COVID -19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respirology. 2022 doi: 10.1111/RESP.14311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts J.R. Radiation risks for CT scans. Emerg Med News. 2008;30:10–12. doi: 10.1097/01.EEM.0000313909.40373.B2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wild J.M., Marshall H., Bock M., Schad L.R., Jakob P.M., Puderbach M., et al. MRI of the lung (1/3): methods. Insights Imaging. 2012;3:345–353. doi: 10.1007/S13244-012-0176-X/FIGURES/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biederer J., Beer M., Hirsch W., Wild J., Fabel M., Puderbach M., et al. MRI of the lung (2/3). Why… When … How? Insights Imaging. 2012;3:355–371. doi: 10.1007/S13244-011-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biederer J., Mirsadraee S., Beer M., Molinari F., Hintze C., Bauman G., et al. MRI of the lung (3/3)-current applications and future perspectives. Insights Imaging. 2012;3:373–386. doi: 10.1007/S13244-011-0142-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi A., Ozier A., Ousova O., Raffard G., Crémillieux Y. Ultrashort-TE MRI longitudinal study and characterization of a chronic model of asthma in mice: inflammation and bronchial remodeling assessment. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1451–1459. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng L., Delacoste J., Smith D., Weissbrot J., Flagg E., Moore W.H., et al. Simultaneous evaluation of lung anatomy and ventilation using 4D respiratory-motion-resolved ultrashort Echo time sparse MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:411–422. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delacoste J., Chaptinel J., Beigelman-Aubry C., Piccini D., Sauty A., Stuber M. A double echo ultra short echo time (UTE) acquisition for respiratory motion-suppressed high resolution imaging of the lung. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:2297–2305. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robson M.D., Gatehouse P.D., Bydder M., Bydder G.M. Magnetic resonance: an introduction to ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:825–846. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veldhoen S., Heidenreich J.F., Metz C., Petritsch B., Benkert T., Hebestreit H.U., et al. Three-dimensional ultrashort echotime magnetic resonance imaging for combined morphologic and ventilation imaging in pediatric patients with pulmonary disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2020:1. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J., Feng L., Otazo R., Kim S.G. Rapid dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for small animals at 7T using 3D ultra-short echo time and golden-angle radial sparse parallel MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81:140–152. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grodzki D.M., Jakob P.M., Heismann B. Ultrashort echo time imaging using pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA) Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:510–518. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson K.M., Fain S.B., Schiebler M.L., Nagle S. Optimized 3D ultrashort echo time pulmonary MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1241–1250. doi: 10.1002/MRM.24570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stock K.W., Chen Q., Hatabu H., Edelman R.R. Magnetic resonance T2/* measurements of the normal human lung in vivo with ultra-short echo times. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(99)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres L., Kammerman J., Hahn A.D., Zha W., Nagle S.K., Johnson K., et al. Structure-function imaging of lung disease using ultrashort echo time MRI. Acad Radiol. 2019;26:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch F.W., Sorge I., Vogel-Claussen J., Roth C., Gräfe D., Päts A., et al. The current status and further prospects for lung magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 2020;50:734–749. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04594-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatabu H., Alsop D.C., Listerud J., Bonnet M., Gefter W.B. T2* and proton density measurement of normal human lung parenchyma using submillisecond echo time gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Radiol. 1999;29:245–252. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(98)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg M., Prabhakar N., Dhooria S., Lamichhane S. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) chest in post-COVID-19 pneumonia. Lung India. 2021;38:498–499. doi: 10.4103/LUNGINDIA.LUNGINDIA_206_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielles-Vallespin S., Weber M.A., Bock M., Bongers A., Speier P., Combs S.E., et al. 3D radial projection technique with ultrashort echo times for sodium MRI: clinical applications in human brain and skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:74–81. doi: 10.1002/MRM.21104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng L., Delacoste J., Smith D., Weissbrot J., Flagg E., Moore W.H., et al. Simultaneous evaluation of lung anatomy and ventilation using 4D respiratory-motion-resolved ultrashort echo time sparse MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:411–422. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang W., Ong F., Johnson K.M., Nagle S.K., Hope T.A., Lustig M., et al. Motion robust high resolution 3D free-breathing pulmonary MRI using dynamic 3D image self-navigator. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:2954–2967. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu X., Chan M., Lustig M., Johnson K.M., Larson P.E.Z. Iterative motion-compensation reconstruction ultra-short TE (iMoCo UTE) for high-resolution free-breathing pulmonary MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83:1208–1221. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John P., Mugler I., Fielden S.W., Meyer C.H., Altes T.A., Miller G.W., et al. (ISMRM 2015) Breath-hold UTE Lung Imaging using a Stack-of-Spirals Acquisition. https://archive.ismrm.org/2015/1476.html

- 34.John P., Mugler I., Meyer C.H., Pfeuffer J., Stemmer A., Kiefer B. (ISMRM 2017) Accelerated Stack-of-Spirals Breath-hold UTE Lung Imaging. https://archive.ismrm.org/2017/4904.html

- 35.Heidenreich J.F., Weng A.M., Metz C., Benkert T., Pfeuffer J., Hebestreit H., et al. Three-dimensional ultrashort Echo time MRI for functional lung imaging in cystic fibrosis. Radiology. 2020;296:191–199. doi: 10.1148/RADIOL.2020192251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landini N., Orlandi M., Occhipinti M., Nardi C., Tofani L., Bellando-Randone S., et al. Ultrashort Echo-time magnetic resonance imaging sequence in the assessment of systemic sclerosis-interstitial lung disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2022 doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olthof S.C., Reinert C., Nikolaou K., Pfannenberg C., Gatidis S., Benkert T., et al. Detection of lung lesions in breath-hold VIBE and free-breathing spiral VIBE MRI compared to CT. Insights Imaging. 2021:12. doi: 10.1186/S13244-021-01124-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sen Huang Y., Niisato E., Su M.Y.M., Benkert T., Chien N., Chiang P.Y., et al. Applying compressed sensing volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination and spiral ultrashort Echo time sequences for lung nodule detection in MRI. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2021:12. doi: 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS12010093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cha M.J., Ahn H.S., Choi H., Park H.J., Benkert T., Pfeuffer J., et al. Accelerated stack-of-spirals free-breathing three-dimensional ultrashort Echo time lung magnetic resonance imaging: a feasibility study in patients with breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021:11. doi: 10.3389/FONC.2021.746059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heidenreich J.F., Veldhoen S., Metz C., Pereira L.M., Benkert T., Pfeuffer J., et al. Functional MRI of the lungs using single breath-hold and self-navigated ultrashort Echo time sequences. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020:2. doi: 10.1148/RYCT.2020190162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sen Huang Y., Niisato E., Su M.Y.M., Benkert T., Hsu H.H., Shih J.Y., et al. Detecting small pulmonary nodules with spiral ultrashort echo time sequences in 1.5 T MRI. MAGMA. 2021;34:399–409. doi: 10.1007/S10334-020-00885-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qian Y., Boada F.E. Acquisition-weighted stack of spirals for fast high-resolution three-dimensional ultra-short echo time MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:135–145. doi: 10.1002/MRM.21620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkelmann S., Schaeffter T., Koehler T., Eggers H., Doessel O. An optimal radial profile order based on the golden ratio for time-resolved MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:68–76. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.885337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng L. Golden-angle radial MRI: basics, advances, and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022 doi: 10.1002/JMRI.28187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Javed A., Ramasawmy R., O’Brien K., Mancini C., Su P., Majeed W., et al. Self-gated 3D stack-of-spirals UTE pulmonary imaging at 0.55T. Magn Reson Med. 2022;87:1784–1798. doi: 10.1002/MRM.29079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng L., Liu F., Soultanidis G., Liu C., Benkert T., Block K.T., et al. Magnetization-prepared GRASP MRI for rapid 3D T1 mapping and fat/water-separated T1 mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2021;86:97–114. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hama Amin B.J., Kakamad F.H., Ahmed G.S., Ahmed S.F., Abdulla B.A., Mohammed S.H., et al. Post COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis; a meta-analysis study. Ann Med Surg. 2022;77 doi: 10.1016/J.AMSU.2022.103590. 103590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material