Abstract

Background

General anaesthesia (GA) for atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation is often preferred over conscious sedation (CS) to minimize patient discomfort and reduce the risk of map disruption from patient movement but may pose an additional risk to some patients with significant comorbidity or poor cardiac function.

Methods

We extracted data for 300 patients who underwent AF ablation between the years 2017 and 2019 and compared the outcomes of AF ablation with CS and GA.

Results

Compared to the GA group, patients were younger in the CS group (63 versus 66 years, p = 0.02), had less persistent AF (34% versus 46%, p = 0.048) and the left atrial dimension was smaller (41 versus 45 mm, p = 0.01). More patients had cryoballoon ablation (CBA) than radiofrequency (RFA) ablation in the CS than the GA group (88% CB with CS and 56% RF with GA, p < 0.01), frequency of ASA score 3-4 (higher anaesthetic risk) was less for CS than for GA (45% versus 75%, p < 0.01), and procedural duration was shorter for patients who had CS (110 versus 139 min, p < 0.001). Of the patients receiving CS, 127/182 (70%) were planned for same day discharge (SDD) and this occurred in 120 (94%) of those patients. There were no significant differences in complication rates between the groups (5.1% in GA and 6% in CS, p = 0.8). AF type was the only significant predictor of freedom from AF recurrence on multivariate analysis (HR 0.33, 0.13–0.82, p = 0.018).

Conclusion

In this study, the use of CS compared with GA for AF ablation was associated with similar outcomes and complication rates.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation ablation, General anaesthesia, Conscious sedation

1. Introduction

AF and its complication related hospitalization carry a significant burden on the health system [1,2]. Anaesthesia in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation poses a number of unique challenges and considerations for the electrophysiologist and the anaesthetist alike. It can be a lengthy procedure with discomfort and both conscious sedation (CS) and general anaesthesia (GA) [3,4] have their own advantages and disadvantages. In a survey of the writing group members in the 2017 ESC guidelines on AF ablation, 73% used GA, 13% deep sedation with an anaesthetist, and 14% CS with an electrophysiology nurse [5]. Different approaches throughout the world, however, reflect different sedation guidelines, different experience with sedation techniques and different staffing in the electrophysiology lab.

AF ablation is commonly performed both with an anaesthetist present and without since the use of techniques such as cryoballoon ablation (CBA) make the procedure shorter and generally lead to less patient discomfort [6,7]. This is a potentially significant advantage for performing AF ablation in the public hospital system where the availability of anaesthetist support is often less [8]. For RF ablation, however, there is discomfort from heating in different regions of the left atrium, the procedures may last longer than 2 h and it is critical that the patient doesn't move their chest as this will reduce the accuracy of catheter localization within the electroanatomic mapping system [9]. In general, the potential advantages to CS are that the total procedural time and recovery time may be shorter than for GA [10], and the advantages to GA include that the patient will not experience/recall any discomfort (once the cannula is in and the anaesthetic is given) and for this reason they are not likely to move their chest resulting in movement of any electroanatomic maps performed [11].

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the last 300 AF ablations performed in the local area (both redo and denovo cases) with the aim of determining if sedation or general anaesthesia were associated with a significant difference in complications or in the rates of freedom from recurrent AF.

2. Methods

After obtaining Ethics Committee approval we extracted data for 300 consecutive patients with symptomatic AF, refractory to at least one AAD, who had undergone CBA or RFA between the years of 2017 and 2019 in 4 hospitals in the local area. Any complications relating to the procedure itself were collected prospectively at the time as this is done routinely at these centres. We then compared those patients who had GA with CS with regards to the procedural aspects such as procedure duration, complications related to the procedure and the anaesthetic approach, acute success rates and then freedom from AF recurrence during follow up. Recurrence was counted if it was symptomatic or detected on Holter monitor.

2.1. Anaesthesia definitions

CS was defined as maintaining patients' spontaneous breathing and purposeful response to painful stimulus and GA was defined as no response to painful stimulus, without patients spontaneous breathing, requiring ventilatory support using either a Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA) or Endotracheal Tube (ETT) [12]. We used American Society of Anaesthesia classification (ASA class) to evaluate the participants’ pre-procedural risk [13].

2.2. Sedation approach

Anaesthetic medications in the majority of the CS group were administered by the cardiology nursing staff and consisted largely of midazolam and fentanyl titrated to effect. In the GA group medications were administered by the anaesthetist and these consisted primarily of midazolam, propofol, remifentanyl infusion and a paralysing agent at induction for patients who were intubated. Volatile anaesthetic agents (eg. Sevoflurane) were used in <5% of cases for maintenance of anaesthesia.

2.3. AF ablation methods

2.3.1. Cryoballoon

Briefly, three sheaths were placed into the right femoral vein (6,7,11 Fr) under ultrasound guidance and a decapolar catheter was positioned into the coronary sinus. The left atrium was accessed via a trans-septal puncture using an SLO sheath (TOE or ICE guidance were only used if there was difficulty in crossing the septum) and this sheath was then exchanged for a FlexCath® sheath (Medtronic). The Cryocath® Arctic Front balloon (23 or 28 mm) (Medtronic) was then advanced to the left atrium for ablation. The Achieve® mapping catheter (Medtronic) was positioned into each vein in turn and cryoballoon freezes were applied until all veins were electrically isolated. When freezing the right sided pulmonary veins, the right phrenic nerve was paced via a quadripolar catheter in the subclavian vein and a diaphragmatic CMAP was also recorded to identify any early impairment in diaphragmatic contraction. A purse string suture was tied over the venous access site at the end of the case for haemostasis [14].

2.3.2. Radiofrequency

After placing three sheaths into the right femoral vein (6,8,8 Fr) under ultrasound guidance, a deflectable decapolar catheter was placed into the coronary sinus, and two transeptal punctures were performed under fluoroscopic guidance with a Cook transeptal needle (TOE or ICE guidance were only used if there was difficulty in crossing the septum). A Lasso mapping catheter was then advanced through one SLO sheath, while the other was exchanged for a steerable sheath. Mapping was performed with the Lasso catheter and ablation was performed in two circles (WACA) around the left and then the right sided pulmonary veins with irrigated ablation to achieve isolation. Pacing to identify the location of the right phrenic nerve was routinely performed. All RFA cases were performed with the CARTO (Biosense Webster) or NavX (Abbott Medical) mapping systems. A purse string suture was tied over the venous access site at the end of the case for haemostasis [14].

2.4. Follow up

All patients were reviewed as a routine at 3 months with a Holter monitor and clinic visit, followed by clinic visits and Holter monitors at 6, and 12 months. AADs were stopped at 3 months following ablation and were only restarted where a recurrence had occurred. Patients were contacted by the phone at the end of the follow up period for the study and all correspondence from the electronic local area health record, general practitioners and other specialists was reviewed.

3. Study endpoints

The primary endpoints for this study were freedom from recurrence of symptomatic atrial tachyarrhythmia following AF ablation and procedural or anaesthetic complication rates in patients undergoing CS or GA.

4. Statistical analysis

All the demographic and procedural characteristics of patients were reported as frequencies for categorical variables, and means (SD) for continuous variables. Student's t-test was used to compare means of the characteristics between the sedation types, and Chi-squared/Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables across sedation types. Univariable logistic regression (with Hochberg FDR adjustments) and multivariable logistic regression were utilised to explore the association between the procedural outcomes and sedation types, as well as with other risk factors. Univariable survival analysis was utilused to explore the association between the time to AF recurrence and the sedation types, as well as the assocation with other risk factors. Kaplan-Meier survival curves with an overall follow up of 24 months were used to show freedom from recurrence in the two different sedation groups. All statistical analyses were programmed using R and SAS V9.4.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Baseline characteristics

This study included 300 patients with AF, who underwent either RF or CB AF ablation. The baseline characteristics of the cohort, stratified by sedation type, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (total number = 300).

| Variable | GA (N = 118) | CS (N = 182) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) (%) | 41 (34.7) | 63 (34.6) | 1 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 66.1 (10.2) | 63.2 (11.4) | 0.02 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.5 (4.82) | 30.2 (5.49) | 0.20 |

| Symptom's duration (months), mean (SD) | 49.3 (47.6) | 51.3 (49.8) | 0.73 |

| CCF (%) | 36 (30.5) | 40 (22) | 0.12 |

| HTN (%) | 59 (50.0) | 79 (43.4) | 0.31 |

| DM (%) | 14 (11.9) | 20 (11.0) | 0.96 |

| Stroke (%) | 7 (5.9) | 8 (4.4) | 0.74 |

| COPD (%) | 7 (5.9) | 24 (13.2) | 0.07 |

| OSA (%) | 17 (14.4) | 26 (14.3) | 1 |

| GORD (%) | 30 (25.4) | 61 (33.5) | 0.17 |

| AF Type, persistent (%) | 54 (45.8) | 61 (33.5) | 0.04 |

| AF Type, paroxysmal (%) | 64 (54.2) | 120 (65.9) | 0.04 |

| LA dimension, mean (SD) | 4.47 (0.833) | 4.15 (0.654) | 0.01 |

| LVEF, mean (SD) | 57.2 (14.3) | 56.0 (10.8) | 0.55 |

| Previous ablation (%) | 40 (33.9) | 24 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Pre-procedure AADs (%) | 112 (94.9) | 171 (94.0) | 0.92 |

| Amiodarone (%) | 49 (41.5) | 55 (30.2) | 0.05 |

| Flecainide (%) | 28 (23.7) | 69 (37.9) | 0.01 |

| Sotalol (%) | 63 (53.4) | 79 (43.4) | 0.11 |

| Digoxin (%) | 14 (11.9) | 30 (16.5) | 0.34 |

| OAC (%) | 116 (98.3) | 172 (94.5) | 0.13 |

| First procedure or Redo | |||

| Redo (%) | 39 (33.1) | 19 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| First (%) | 79 (66.9) | 163 (89.6) | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index, CCF: congestive cardiac failure, HTN: hypertension, DM: diabetes mellitus, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OSA: obstructive sleep apnoea, LA: left atrium.

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, OAC: oral anticoagulation.

5.2. Procedural outcomes and complications

182 patients had AF ablation with CS and 118 patients had AF ablation under GA. There was a higher proportion of patients in the GA group who had RFA (56% vs. 11%) and a lower proportion who had CBA (44% vs. 88%) (p < 0.001). Procedural duration in the CS group was shorter (115 vs. 139 min), and the fluoroscopy duration was longer (24.7 vs. 19 min) (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Patients were less likely to receive arterial line monitoring with CS than GA (23% versus 98%, p < 0.01). Of the patients receiving CS, 127/182 (70%) were planned for same day discharge (SDD) and this occurred in 120 (94%) of those patients. The most common reason for failure of SDD was a late time for procedural completion.

Table 2.

Procedural characteristics.

| Variable | GA (N = 118) | CS (N = 182) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure type | |||

| RFA (%) | 66 (55.9) | 21 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| CBA (%) | 52 (44.1) | 161 (88.5) | <0.001 |

| ASA 1-2 (%) | 29 (24.6) | 101 (55.5) | <0.001 |

| ASA 3-4 (%) | 89 (75.4) | 81 (44.5) | <0.001 |

| Procedure time, mean (SD) | 139 (52.1) | 115 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| RFA, mean (SD) | 177 (36.2) | 162 (36) | |

| CBA, mean (SD) | 91.9 (21.8) | 109 (25.4) | |

| Fluoro time, mean (SD) | 19.0 (7.63) | 24.7 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| RFA, mean (SD) | 20.8 (8.74) | 24.3 (10.5) | |

| CBA, mean (SD) | 16.6 (5.1) | 24.8 (12) | |

| Anaesthetist present (%) | 118 (100) | 75 (41.2) | <0.001 |

| Radial arterial line (%) | 116 (98.3) | 42 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Procedural complication (%) | 6 (5) | 12 (6.5) | 0.9 |

| RFA (%) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | |

| CBA (%) | 5 (4.2) | 11 (6) | |

| Sedation related complication (%) | 0 | 2 (1.1) | NA |

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesia classification, RFA: radiofrequency ablation, CBA: cryoballoon ablation.

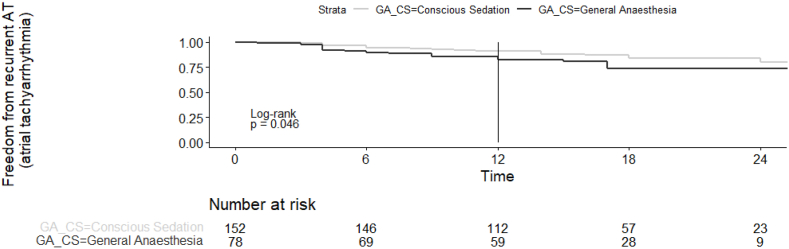

The freedom from recurrence of ATs for denovo procedures at 24 months is shown in Fig. 1. Freedom from ATs at 12 months was 83% and 91%, and at 24 months, 74% and 80%, in GA and CS group, respectively (p = 0.04) (Fig. 1). There was no statistically significant difference in freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias during follow up, when comparing the use of GA versus CS based on the procedure type (CBA versus RFA, Fig. 2, Fig. 3). On univariate analysis the only significant predictors of freedom from recurrence of AT off AADs following ablation were the use of CS (HR 0.53, 0.28–0.99, p = 0.05) and the presence of paroxysmal AF (HR 0.3, 0.16–0.58, p < 0.01) (Table 3). AF type was the only significant predictor on multivariate analysis (HR 0.33, 0.13–0.82, p = 0.01) (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Survival free from AT recurrence comparing GA and CS group, denovo procedures.

Fig. 2.

Survival free from AT recurrence comparing GA and CS in RFA group.

Fig. 3.

Survival free from AT recurrence comparing GA and CS in CBA group.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios from Univariable Cox Regression Models (N = 242) for freedom from recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmia.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| CS versus GA | 0.53 (0.28–1) | 0.05 |

| AF type (paroxysmal vs. persistent) | 0.3 (0.16–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.71 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.61 (0.32–1.15) | 0.12 |

| BMI | 1.04 (0.98–1.1) | 0.24 |

| LVEF | 1 (0.96–1.03) | 0.84 |

| LA dimension | 1.32 (0.77–2.27) | 0.31 |

| CCF (yes vs. no) | 1.65 (0.83–3.29) | 0.15 |

| HTN (yes vs. no) | 1.34 (0.71–2.53) | 0.37 |

| DM (yes vs. no) | 1.95 (0.86–4.44) | 0.11 |

| COPD (yes vs. no) | 1.17 (0.41–3.31) | 0.76 |

| OSA (yes vs. no) | 1.36 (0.62–2.97) | 0.44 |

| GORD (yes vs. no) | 0.69 (0.33–1.45) | 0.32 |

| Procedure duration (minutes) | 1 (0.99–1.01) | 0.42 |

| Procedure type (RF vs. CB) | 0.71 (0.3–1.71) | 0.45 |

| Anaesthetist present (yes vs. no) | 1.86 (0.9–3.83) | 0.09 |

| Complete pulmonary vein isolation (yes vs. no) | 0.32 (0.08–1.32) | 0.11 |

| ASA (3-4 vs. 1-2) | 0.9 (0.47–1.7) | 0.73 |

Table 4.

Hazard ratios from multivariable cox regression models (N = 242).

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| CS versus GA | 0.74 (0.27, 2.03) | 0.55 |

| AF type (paroxysmal vs. persistent) | 0.33 (0.13, 0.82) | 0.01 |

| LVEF | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.62 |

There was a total of 18 procedural complications. 3 major complications (1%) including 2 pericardial tamponades (1 in the CS and 1 in the GA group), both were treated with a subcostal drain only and 1 transient ischaemic attack. Minor complications (5%) include 2 groin haematomas (neither requiring an intervention), 1 transient haemoptysis, and 12 transient phrenic palsies which was the most common complication in both groups; 3 (2.5%) in the GA, 9 (4.9%) in CS group (p = 0.40).

5.3. Sedation related complications

The most common combination of medications in the GA group was propofol (98.3%), midazolam (87.3%), and fentanyl (83.1%) and in the CS group was midazolam (94.5%) and fentanyl (84.6%). There were no sedation related complications in the GA group. In the CS group, a patient with morbid obesity and OSA became drowsy post procedure and was found to be in type 2 respiratory failure, requiring a period of non-invasive ventilation. This was thought to be due to peri-procedural prophylactic phenergan for known contrast allergy. The patient was discharged from hospital uneventfully. Another patient in the CS group became agitated and confused after anaesthetic which was investigated with brain CT and MRI, both were unremarkable, and patient was discharged home the following day.

6. Discussion

This paper represents the first regional comparison between different approaches to anaesthesia for AF ablation. It also includes the largest cohort in comparing anaesthetic approaches in CBA patients. Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias during follow up was higher in the CS group for denovo procedures (83% vs. 91% at 12 months, and 74% vs. 80% at 24 months, in GA and CS groups, respectively p = 0.04). On multivariate analysis, however, the only significant predictor of freedom from recurrent ATs was AF type (HR 0.33 (0.13, 0.82) for PAF) suggesting that the univariate difference in arrhythmia recurrence was predominantly owing to the favourable patient characteristics in the CS group. CS was, as expected, more likely to be chosen for denovo procedures in patients with paroxysmal AF undergoing cryoballoon ablation. Whereas patients who received GA had larger LA sizes, more persistent AF and more often had had prior ablations. These factors all appeared to increase the rates of AT recurrence in the GA group.

Narui et al. [15] retrospectively reviewed 255 patients with AF who underwent RF ablation with ‘deep sedation’ with propofol and ‘mild sedation’ with flunitrazepam [15]. In this study there was no significant difference in the rates of AF recurrence (29.0 vs 26.5%, p = 0.85 for mild and deep sedation respectively) and no difference in complication rates. There was less spontaneous pulmonary veins firing with deep sedation, however, but no significant difference in the rates of non-pulmonary vein triggers seen [15]. In the study by Di Biase et al. [9], they randomized 257 patients undergoing denovo RFA for paroxysmal AF, to CS with fentanyl and midazolam or GA. They found a higher freedom from recurrent ATs using GA, compared to CS (88% vs. 69%, p < 0.001) at 17 ± 8 months, without any sedation related complications [9]. Furthermore, at redo procedures more pulmonary veins were durably isolated with the use of GA [9]. This was true also in the observational study by Martin et al. [16] who followed 292 patients having had RFA and found that freedom from recurrent ATs was less at 1 year when GA was used compared to CS with fentanyl and midazolam (63.9% vs 42.3%, p = 0.002). However, in the meta-analysis by Li et al. [17], there was a non-significant reduction in the risk of AT recurrence (RR: 0.79, 95% CI 0.56–1.13, p = 0.2) and in complication rates (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.64–1.42, p = 0.82) with the use of GA compared to CS.

Heterogeneity in the findings of these studies may reflect the fact that CS and GA are broad terms and the way in which they are performed, the depth of CS, the medications used and the experience of the sedationist differ significantly between studies. Overall, there seems to be a trend towards improved outcomes with RFA with GA and this is intuitive since GA can facilitate improved contact force and stability for ablation [18]. In this study, however, the majority of patients receiving CS underwent cryoballoon ablation (161/182) where catheter stability is achieved by cryoadhesion of the catheter to the pulmonary vein antrum [19]. In the study of CS versus GA for cryoballoon ablation, Wasserlauf et al. [10] followed 55 patients with GA and 119 with CS. There was no significant difference in freedom from recurrent AF in these two groups at 0.9 years (61.8% GA vs 63.0% with CS, p = 0.9) and no difference in the complication rates, suggesting that particularly with cryoballoon AF ablation, CS is likely to achieve equivalent outcomes to GA.

There were no significant differences in the rates of complications between the GA and the CS groups (Table 2). Major complication rates were 1.7% in the GA group and 0.6% in CS group (p = NS) and minor complications were 3.4% in GA and 5.0% in CS (p = NS). It should be acknowledged that complications were generally infrequent and that this study therefore had low power for this outcome. The most frequent complication in this study was transient PNP occurring in 2.5% of the GA group, and 4.9% of CS patients (p = 0.4). In this study transient PNP was seen only in patients who underwent cryoballoon ablation and is a complication that is recognised to occur more frequently with cryoballoon ablation [20,21]. Whilst there was no difference in the rates of PNP is this study patients may tolerate phrenic nerve pacing better under general anaesthesia and less movement or spontaneous breathing may make early PNP easier to detect. The use of CS, however, may make early recognition of stroke or of cardiac perforation (due to the patient reporting pericardial pain) easier.

There were no significant differences in the rates of sedation related complications in this study (GA: 0%, CS: 1.1%, p = NS). Sedation related complications were low overall with both GA and CS and when an anaesthetist was not present. However, given the retrospective nature, it is likely that patients who were at a higher anaesthetic risk (due to morbid obesity, OSA, a prior sedation related complication or limited functional reserve, for example) were more likely to have an anaesthetist present for their ablation [12]. Some studies have shown that deep sedation with propofol can be performed safely in the electrophysiology laboratory by the cardiology team in conjunction with specialist nursing staff [22,23]. However, there are significant regional differences in training and experience in relation to anaesthesia provision that limit the generalizability of these studies.

CS was most commonly performed with a benzodiazepine and opioid combination in this study. This combination was used for electrophysiology procedures in 1344 patients by Kovoor et al. [24] with no major sedation related complications. In a study by Munkler et al. [11], they used a standardized questionnaire assessing pain and awareness during the procedure, recovery, and post procedural effects in 117 consecutive patients who underwent catheter ablation for atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias with deep sedation using midazolam with either ketamine or propofol. The majority of the study participants reported a high level of satisfaction with peri-procedural sedation. This outcome, however, was limited to a selected cohort of patients who underwent the procedure with deep sedation without any comparison to a lower-level sedation. Moreover, all the answers were subject to the patients’ perspective as opposed to including any objective assessment of peri-procedural alertness level. In this study, all the patients in the GA and CS groups tolerated the procedure, suggesting the perioperative assessments for GA or CS were made with a high degree of accuracy.

In this study the procedure times were longer for patients receiving GA (130 vs 115 min, p < 0.001) and the fluoroscopy times were shorter (19.0 vs 24.7 min) than with CS. This is likely to relate to the fact that more patients receiving RFA [20] had GA than CS (55.9% of patient versus 11.5% respectively), (Table 2). Patients receiving GA were also older (66.1 vs 63 years, p = 0.02), had more persistent AF (45.8 vs 33.5%, p = 0.04), larger left atria (4.5 vs 4.2 mm, p = 0.04) and had a higher incidence of a previous ablation (33.9 vs 13.2%, p < 0.001). All of which would potentially make the procedure more complex and therefore increase procedural duration. Despite one trial that found shorter procedural times with GA for RFA [9], the meta-analysis by Li et al. [17] did not find a significant difference in procedure or fluoroscopy times with GA and CS. In contrast to this, the study by Wasserlauf et al. [10] did find that total laboratory time (280 vs 245 min, p < 0.001) and both nonprocedure time (92 vs 71 min, p < 0.001), and procedure time (188 vs 174 min, p = 0.09) were longer when cryoballoon ablation was performed with GA instead of CS. In this study a longer preparation and procedure time for GA did not appear to be offset by a more easily performed ablation as was the case in most RFA studies [[15], [16], [17], [18]].

In this study, the majority of patients who underwent AF ablation with CS were able to undergo SDD (94% of those planned for SDD) and this is the first local study to show the feasibility of SDD in patients undergoing AF ablation which may lead to potential cost savings for the procedure. The safety and feasibility of same day discharge (SDD) after AF ablation has been shown previously in several international trials [[25], [26], [27]]. In the multicentre study by He et al. [28], they showed safety and cost effectiveness of SDD in 967 patients who had complex left atrial RF or CB ablation. They used CS in 95% of patients. Only 8% of the cohort who were planned for SDD required overnight admission [28]. In another multicentre cohort study by Deyell et al. [25] on 3054 patients undergoing AF ablation, SDD was achieved in 79.2% without an increase in hospital readmission or complication rate. In a retrospective study by Wang et al. [29] on 351 patients who underwent first AF ablation for persistent AF, it was shown that AF ablation with GA was associated with higher cost and total procedural time compared with AF ablation with sedation without any statistically significant differences in freedom from AF at 1 year [29]. Martin et al. [15], however, found that despite a higher initial expense rate of using GA compared to CS, GA reduced the rate of redo procedures in patients with persistent AF with more comorbidities [16].

6.1. Limitations

Although procedural complications were collected prospectively, sedation related complications and later sequelae of anaesthetic approaches such as throat pain from intubation or wrist pain from arterial line placement were collected retrospectively and the true incidence may have been underestimated. The sedation methods in this study were not randomized, and the confounding by indication in this observational study is a significant limitation. However, we aimed to present the results of real-world scenarios where both GA and CS are used in the treatment for AF ablation.

7. Conclusion

In this study of patients undergoing both RFA and CBA for AF, the use of CS compared to GA resulted in similar short- and long-term outcomes and complication rates. This supports the current practice of individualizing the choice of anaesthesia based on procedural and patient characteristics.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Robert Thomas (MBBS, FCICM, FANZCA) and Dr Paul Healey (MBBS, FCICM, FANZCA) for their valued contribution to the anaesthetic aspects of the study design and results.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Indian Heart Rhythm Society.

References

- 1.Patel NJ, Deshmukh A, Pant S, Singh V, Patel N, Arora S, et al. Contemporary trends of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation in the United States, 2000 through 2010: implications for healthcare planning. (1524-4539 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Gallagher C, Hendriks JA-O, Giles L, Karnon J, Pham C, Elliott AD, et al. Increasing trends in hospitalisations due to atrial fibrillation in Australia from 1993 to 2013. (1468-201X (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. (0003-3022 (Print)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Thomas S.P., Thakkar J.A.Y., Kovoor P., Thiagalingam A., Ross D.L. Sedation for electrophysiological procedures. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37(6):781–790. doi: 10.1111/pace.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calkins H., Hindricks G., Cappato R., Kim Y.H., Saad E.B., Aguinaga L., et al. 2017. HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. (1556-3871 (Electronic)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalman JM, Sanders P Fau-Brieger DB, Brieger Db Fau - Aggarwal A, Aggarwal A Fau - Zwar NA, Zwar Na Fau - Tatoulis J, Tatoulis J Fau - Tay AE, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia consensus statement on catheter ablation as a therapy for atrial fibrillation. (1326-5377 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Jackson N, Barlow M Fau-Leitch J, Leitch J Fau-Attia J, Attia J. Treating atrial fibrillation: pulmonary vein isolation with the cryoballoon technique. (1444-2892 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cheng TC, Joyce Cm Fau-Scott A, Scott A. An empirical analysis of public and private medical practice in Australia. (1872-6054 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Di Biase L, Conti S Fau-Mohanty P, Mohanty P Fau-Bai R, Bai R Fau-Sanchez J, Sanchez J Fau - Walton D, Walton D Fau-John A, et al. General anesthesia reduces the prevalence of pulmonary vein reconnection during repeat ablation when compared with conscious sedation: results from a randomized study. (1556-3871 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wasserlauf J., Knight B.P., Li Z., Andrei A.-C., Arora R., Chicos A.B., et al. Moderate sedation reduces lab time compared to general anesthesia during cryoballoon ablation for AF without compromising safety or long-term efficacy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol : PACE (Pacing Clin Electrophysiol) 2016;39(12):1359–1365. doi: 10.1111/pace.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munkler P, Attanasio P, Parwani AS, Huemer M, Boldt LH, Haverkamp W, et al. High patient satisfaction with deep sedation for catheter ablation of cardiac arrhythmia. (1540-8159 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Practice Guidelines for Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia A report by the American society of anesthesiologists task force on moderate procedural sedation and analgesia, the American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons, American college of radiology, American dental association, American society of dentist anesthesiologists, and society of interventional radiology. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2018;128(3):437–479. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002043. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle D.J.G.E. StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. American society of anesthesiologists classification (ASA class) [updated 2019 may 13]. . In: StatPearls [internet]. Treasure island (FL)https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441940/ Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson N, McGee M, Ahmed W, Davies A, Leitch J, Mills M, et al. Groin haemostasis with a purse string suture for patients following catheter ablation procedures (GITAR Study). (1444-2892 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Narui R., Matsuo S., Isogai R., Tokutake K., Yokoyama K., Kato M., et al. Impact of deep sedation on the electrophysiological behavior of pulmonary vein and non-PV firing during catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2017;49(1):51–57. doi: 10.1007/s10840-017-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin C.A., Curtain J.P., Gajendragadkar P.R., Begley D.A., Fynn S.P., Grace A.A., et al. Improved outcome and cost effectiveness in ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation under general anaesthetic. EP Europace. 2017;20(6):935–942. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li KHC, Sang T, Chan C, Gong M, Liu Y, Jesuthasan A, et al. Anaesthesia use in catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. (1759-1104 (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Chikata A., Kato T., Yaegashi T., Sakagami S., Kato C., Saeki T., et al. General anesthesia improves contact force and reduces gap formation in pulmonary vein isolation: a comparison with conscious sedation. Heart Ves. 2017;32(8):997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00380-017-0961-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrade J.G., Khairy P., Dubuc M. Catheter cryoablation. Circulation: Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2013;6(1):218–227. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.973651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuck K.H., Brugada J., Furnkranz A., Metzner A., Ouyang F., Chun K.R., et al. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2235–2245. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortuni F, Casula M, Sanzo A, Angelini F, Cornara S, Somaschini A, et al. Meta-analysis comparing cryoballoon versus radiofrequency as first ablation procedure for atrial fibrillation. (1879-1913 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kottkamp H., Hindricks G., Eitel C., Muller K., Siedziako A., Koch J., et al. Deep sedation for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a prospective study in 650 consecutive patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22(12):1339–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wutzler A., Rolf S., Huemer M., Parwani A.S., Boldt L.-H., Herberger E., et al. Safety aspects of deep sedation during catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol : PACE (Pacing Clin Electrophysiol) 2012;35(1):38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovoor P, Porter R Fau-Uther JB, Uther Jb Fau-Ross DL, Ross DL. Efficacy and safety of a new protocol for continuous infusion of midazolam and fentanyl and its effects on patient distress during electrophysiological studies. (0147-8389 (Print)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Deyell Marc W., Leather Richard A., Macle L., Forman J., Khairy P., Zhang R., et al. Efficacy and safety of same-day discharge for atrial fibrillation ablation. JACC (J Am Coll Cardiol): Clinical Electrophysiology. 2020;6(6):609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D NA, Mariam W, Luthra P, Edward F, D JK, S AL, et al. Safety of same day discharge after atrial fibrillation ablation. (1941-6911 (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.N Akula D., Mariam W., Luthra P., Edward F., Katz D J., Levi S A., et al. Safety of same day discharge after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Atr Fibrillation. 2020;12(5):2150. doi: 10.4022/jafib.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He H., Datla S., Weight N., Raza S., Lachlan T., Aldhoon B., et al. Safety and cost-effectiveness of same-day complex left atrial ablation. Int J Cardiol. 2021;322:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z., Jia L., Shi T., Liu C. General anesthesia is not superior to sedation in clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness for ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol. 2021;44(2):218–221. doi: 10.1002/clc.23528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]