Abstract

Background:

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is exceedingly common among individuals with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. However, studies on alcohol use in psychiatric illness rely largely on population surveys with limited representation of severe mental illness (SMI); schizophrenia, bipolar disorder.

Methods:

Using data from the Genomic Psychiatry Cohort (GPC) (Pato MT, 2013), associations of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia with alcohol use problems were examined in a diverse US based sample, considering the influence of self-described race (African Ancestry (AA), European Ancestry (EA), or Latinx Ancestry (LA)), sex, and tobacco use. Participants answered alcohol use problem items derived from the CAGE instrument, yielding a summed “probable” alcohol use disorder (pAUD) risk score.

Results:

This study included 1952 individuals with bipolar disorder with psychosis (BDwP), 409 with bipolar disorder without psychosis (BD), 9218 with schizophrenia (SCZ), and 10416 unaffected individuals. We found that SMI (BDwP, BD, SCZ) was associated with elevated AUD risk scores (B = 0.223, p<0.001), an association which was strongest in females, particularly those of AA and LA, and in tobacco users. Schizophrenia was associated with the greatest increase in pAUD score (B = 0.141, p<0.001). pAUD risk scores were increased among participants with bipolar disorder, with greater increases in BDwP (B = 0.125, p<0.001) than in BD without psychosis (B = 0.027, p<0.001).

Limitations:

Limitations include reliance on self-report data, screening items for AUD, voluntary recruitment bias, and differences in race/sex distribution between groups, which were statistically adjusted for in analytic models.

Conclusions:

SMI is associated with risk for AUD, particularly amongst females from racial minority groups, smokers, and those with psychotic disorders.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis, substance use, addiction, dual diagnosis

1. Introduction

Among individuals with severe mental illness (SMI), co-occurring substance use disorders (SUD) are extraordinarily common, seen in roughly half of all cases (Drake & Mueser, 2000). Due to its widespread accessibility, cultural acceptance, and high addictive potential, alcohol is the most commonly used intoxicating substance in SMI (Regier et al., 1990) and in general populations worldwide (Peacock et al., 2018), resulting in 3 million global deaths each year (World Health Organization, 2019). Further, co-occurring alcohol use disorder (AUD) is associated with a significantly increased burden of medical and psychosocial problems in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Brunette et al., 2018; Cardoso et al., 2008; Drake & Mueser, 2002; García et al., 2016; Hjorthøj et al., 2015; Hunt et al., 2016). Unfortunately, in patients with psychotic disorders, AUD often goes undiagnosed and untreated (Buckley & Brown, 2006; Drake et al., 1990). Characterizing demographic and clinical correlates of alcohol abuse in this population may inform efforts for early detection, targeted preventative intervention, and the development of mechanistic hypotheses accounting for increased harmful drinking in patients with a severe mental illness.

Existing data on rates of alcohol use in psychiatric illness largely stem from general population surveys, with limited representation of individuals with psychotic disorders. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey, conducted between 1980 and 1985, found lifetime AUD was present in 33.7% and 46.2% of respondents with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, respectively, compared with 13.5% of the general population (Regier et al., 1990). Subsequent studies have found slightly lower rates of AUD in schizophrenia, ranging from 22%−32% (Degenhardt et al., 2001; Montross et al., 2005; Swartz et al., 2006; Toftdahl et al., 2016). Population surveys since the ECA program have reported heterogeneous rates of AUD in those with bipolar disorder, ranging anywhere from 24–54% (Di Florio et al., 2014; Oquendo et al., 2010).

In psychiatric cohorts, as in the population at large, there exist significant gender differences in alcohol consumption, with males drinking more frequently, consuming larger quantities, and developing AUDs at higher rates than females (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). although recent studies have found this gap is narrowing (Keyes et al., 2008). Women may drink less, in part, due to greater physiologic sensitivity to ethanol, but sociocultural factors may have an even greater impact. In the US, culturally-defined gender roles may dictate greater acceptance of public intoxication, social disinhibition, and externalizing behavior among men, with women subjected to greater social sanctions for drinking (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). While females with severe mental illnesses drink less than their male counterparts (Brunette et al., 2018; Hunt et al., 2018), differences in drinking between men and women appear to be reduced in the context of severe mental illness (Frye et al., 2003; Hartz et al., 2014).

While it is often reported that Whites in the United States (US) consume more alcohol than those who identify as African American or Black, with Hispanic/Latino individuals falling somewhere in between (D. Falk et al., 2008), these trends may not hold true in severe mental illness. For instance, in a large sample of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (n=6,424), Montross et al. (2005) found that alcohol abuse occurred significantly more often in Black (25%) than White (22%) or Hispanic/Latino participants (19%), while Kilbourne et al. (2005) found that patients from any ethnic minority group were at increased risk for AUD in the context of bipolar disorder. Other authors, however, report a White predominance in AUD diagnoses among patients with primary psychotic disorders, analogous to general population trends (Brunette et al., 2018; Miles et al., 2003). Therefore, further research conducted in large and diverse samples of individuals with severe mental illness is needed to better understand these potential group differences.

In psychiatric samples, as in the population at large, those who abuse alcohol are at considerably increased risk for other SUDs, particularly tobacco use disorder (TUD). Alcohol and tobacco are the two most commonly abused drugs among patients with severe mental illness, likely due to their legal status, accessibility, and highly addictive nature (Waxmonsky et al., 2005). In a mixed psychosis sample, Kavanagh et al. (2004) found that those who used tobacco in the past year had a 3.3 times greater risk of lifetime AUD. Similarly, in 80 adolescents with bipolar disorder, baseline tobacco use predicted the subsequent development of alcohol abuse and/or dependence (Heffner et al., 2012). This suggests that, while severe mental illness alone predisposes one to developing an AUD, co-occurring TUD may compound the risk of alcohol use problems in these patients. Although there exists widespread consensus that SMI, AUD, and TUD all have statistically and clinically significant relationships with one another (D. E. Falk et al., 2006; Hartz et al., 2014; Kavanagh et al., 2004), the interaction between alcohol and tobacco use problems has not been sufficiently studied in large samples with psychotic illness.

The present study examined problematic alcohol use behaviors in the largest available cohort of African Ancestry (AA), European Ancestry (EA), and Latinx Ancestry (LA) individuals ascertained for schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders in the USA. Our measure of ‘probable’ AUD risk (pAUD) consisted of a quantitative score based on responses to a questionnaire derived from the CAGE instrument, consistent with a growing appreciation for the dimensional nature of alcohol problems (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Helle et al., 2020; Krueger et al., 2018). Further, we examined the influence of race, sex, and lifetime TUD on the association between SMI diagnoses and alcohol use problems. Guided by the extant literature, we hypothesized that pAUD scores would be significantly higher among participants diagnosed with severe mental illness.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and recruitment

The present study examines data from the Genomic Psychiatry Cohort (GPC), a multi-institutional genomic study which collects participants including cases with the diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and “controls”, whom are defined as individuals not diagnosed with schizophrenia (SCZ) or bipolar disorder (BD) or multiple depressive episodes (>4) and with no first- or second-degree relatives with SCZ or BD. Further, participants were screened for traumatic brain injury(Pato et al., 2013). Participants come from urban, suburban, and rural populations across the United States. All participants were recruited through referrals from healthcare professionals, recruitment in community dwellings or hospital waiting rooms, and through online advertising. Control participants were recruited through similar means and come from the same geographic regions as cases. All participants were provided with informed consent. Individual institutional review board approval was granted for each recruitment site. Further detail on the GPC sample can be found in Pato et al., 2013. Participants (cases and controls) used in this analysis were those that selected one of the following self-reported ‘races’ among the choices given: African American/Black (African Ancestry - AA), White / Caucasian ( European -Caucasian Ancestry - EA), or Hispanic/Latino ( Latino-Ancestry LA) For the purposes of this analysis, those who selected other racial groups or multiple racial groups were not included in the present analysis because of much smaller sample size.

2.2. Severe Mental Illness Classification

All participants enrolled as cases were assessed by trained interviewers using the Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis and Affective Disorders (DI-PAD). This semi-structured clinical interview was developed for the GPC study from the Diagnostic Interview for Genetics Studies (DIGS) (Nurnberger et al., 1994; Pato et al., 2013). DI-PAD data is applied to the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness (OPCRIT) (McGuffin et al., 1991), a 90-item electronic checklist with diagnostic algorithms, to diagnosis schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar disorders, a method which has proved consistent with best-estimate lifetime procedures (Azevedo et al., 1999). Diagnostic criteria represented in OPCRIT derive from the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and are consistent with DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Every case and control also receves the GPC Screening Questionaire, ( Pato et al, 2013) that includes self report of “race/ethnicity”, sex, medical illnesses, and 32 yes/no quesitons screening for psychiatric illnesses, substance use/abuse including pAUD and pTUD.

In the present study, schizophrenia cases include participants that have been diagnosed with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder depressed type. Bipolar disorder without psychosis (BD) includes participants with a history of mania, with or without depression, and no history of psychotic symptoms. Bipolar disorder with psychosis (BDwP) denotes participants with a history of mania, with or without depression, and a history of psychotic symptoms. This BDw/P groups also includes those diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder bipolar type, as these patients are typically clustered with bipolar disorder due to similarities in lifetime symptomatology, treatment responsiveness, and course of illness (Keck et al., 1994; Keshavan et al., 2011; Winokur et al., 1998). The term severe mental illness (SMI) refers to participants with either BD, BDwP or Scz).

2.3. Alcohol use disorder risk assessment

All participants were administered a screening questionnaire, including a series of 6 yes/no questions on signs and symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence, adapted from the CAGE questionnaire (Ewing, 1984) and the DIGS (Nurnberger et al., 1994). AUD score, ranging from 0 to 6, reflects the number of “yes” responses to the following alcohol use screener items. The more items endorsed the more severe the risk for pAUD:

(Q12) Do you often have more than 4 drinks in one day (for women) or more than 5 drinks in one day (for men)

(Q13) Have you been under the influence of alcohol 3 or more times in situations where you could have caused an accident or gotten hurt? (Examples: driving while intoxicated, operating machinery, during sports, or while using a gun)

(Q14) Have you often had a lot more to drink than you intended to have or do you often drink to calm your nerves?

(Q15) Have you ever wanted to quit or tried to cut down on your drinking and found that you couldn’t?

(Q16) Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

(Q17) Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

A ‘yes’ response to 2 or more items, in accordance with the CAGE instrument (Ewing, 1984) indicates high risk for AUD and qualifies a participant as having a ‘probable AUD’ in the present study.

2.4. Tobacco use assessment

The screener questionnaire contained 4 yes/no questions assessing dimensions of tobacco use disorder (TUD). A participants TUD score, ranging from 0 to 4, reflects the number of “yes” responses to the following tobacco use screener items. Similarly the more items endorsed the more severe the risk for TUD:

Over your lifetime, have you smoked more than 100 cigarettes? Include cigars, pipes, and chewing tobacco.

Have you ever had a period of one month or more when you smoked cigarettes every day?

Did you usually smoke your first cigarette within one hour of waking up?

Have you ever wanted to quit smoking or have tried to quit smoking and found that you couldn’t?

In the present study, a TUD score of 2 or more qualifies as a ‘probable TUD’.

2.5. Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 28). Linear regression modelling was used to examine the association of severe mental illness and AUD score, adjusting for female sex, race, and probable TUD, which were included as covariates. Two-way interaction terms [SMI x Race], [SMI x Sex], and [SMI x TUD] were tested in the regression model, in order to determine whether Race, Sex, or TUD significantly moderates the relationship between SMI and AUD score. Three-way interactions [SMI x Race x Sex] were also tested to look for moderating effects of race and sex on the association of SMI with AUD score. Post-hoc, three regression models were run to determine the association of individual SMI diagnoses (Scz, BDwP, and BD) with AUD score, adjusting for sex, race, and probable TUD. Additional analyses included one-way ANOVA testing to examine differences in rates of probable AUD and mean AUD scores between SMI diagnoses, as well as independent samples t-tests to identify differences in mean AUD score by sex.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

The sample used for this study comprises 19,647 individuals, including 8,253 schizophrenia cases (Scz), 1,796 bipolar disorder with psychosis cases (BDwP), 384 bipolar without psychosis cases (BD), and 9,214 controls. Average age was similar across diagnostic groups, with mean ages of 43.51 years (SD 12.76) for Scz, 43.00 years (SD 12.58) for BDwP, 43.67 years (SD 13.81) for BD, and 41.58 years (SD 15.77) for controls. There was no available data on when subjects began smoking or using alcohol so duration of tobacco and alcohol use could not be analyzed. However, sex and race varied in their distribution between groups (see Table 1), with disproportionate representation of AA individuals in all groups. The male to female ratio in the schizophrenia group was roughly 2 to 1, which may be a reflection of the male predominance often reported in schizophrenia (Abel et al., 2010). For this reason, race and sex were controlled for in all analyses.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by diagnostic group.

| SCZ (N=8,253) | BD with Psychosis (N = 1,796) | BD without Psychosis (N = 384) | SMI (N = 10,433) | Control (N = 9,214) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 2663 (32.3%) | 910 (50.7%) | 210 (54.7%) | 3783 (36.3%) | 4900 (53.2%) |

| Male | 5590 (67.7%) | 886 (49.3%) | 174 (45.3%) | 6650 (63.7%) | 4314 (46.8%) |

| Race | |||||

| European Ancestry | 3010 (36.5%) | 177 (9.9%) | 79 (20.6%) | 3266 (31.3%) | 3052 (33.1%) |

| African Ancestry | 3817 (46.2%) | 1231 (68.5%) | 232 (60.4%) | 5280 (50.6%) | 4468 (48.5%) |

| Latinx Ancestry | 1426 (17.3%) | 388 (21.6%) | 73 (19.0%) | 1887 (18.1%) | 1694 (18.4%) |

SMI is the sum of SZ, BD w. Psychosis and BD without Psychosis

3.2. Severe Mental Illness and Risk for AUD

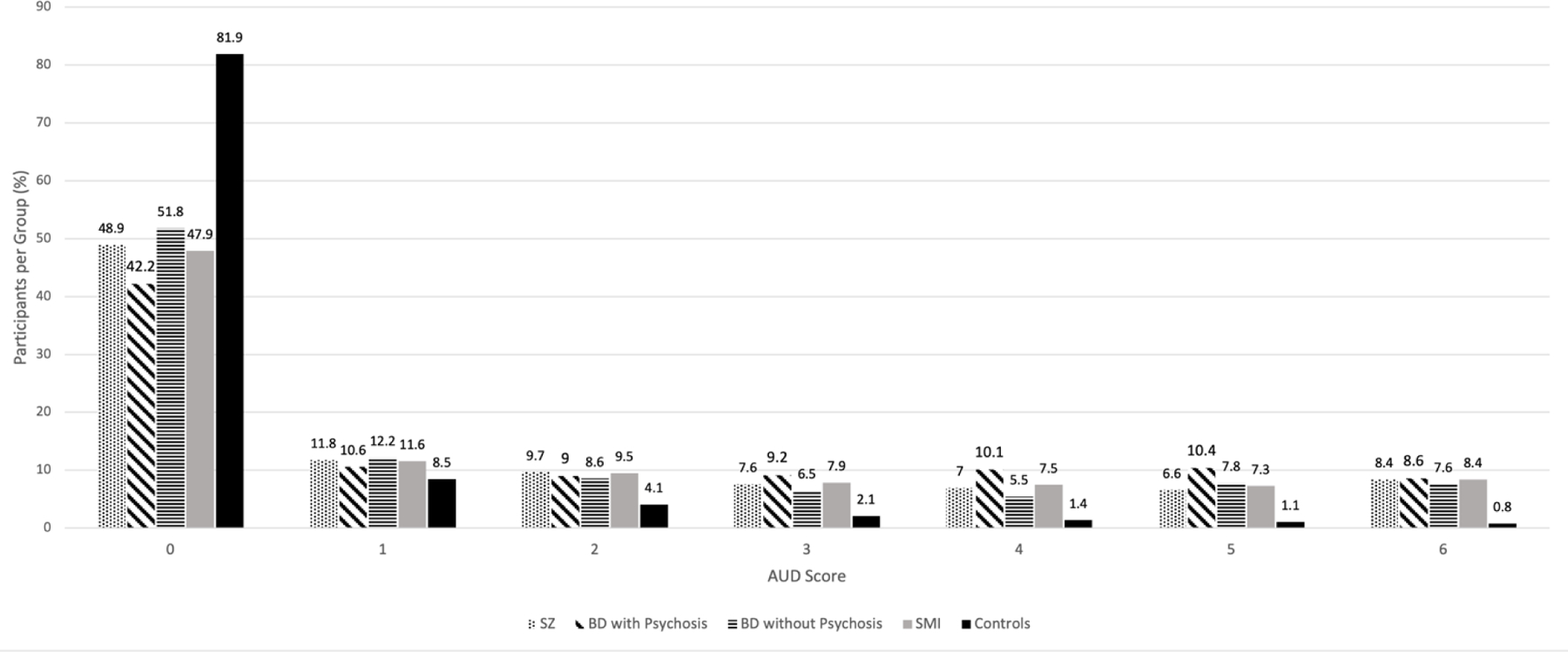

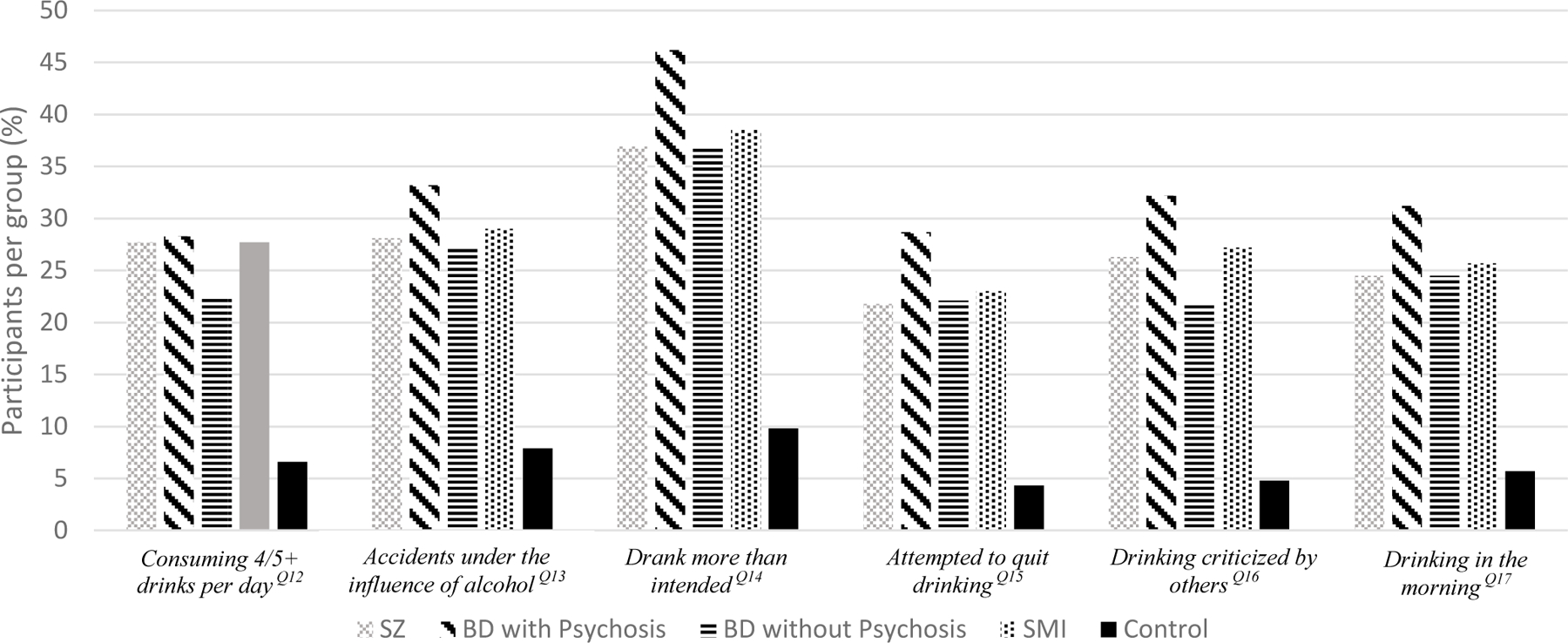

The rates of probable AUD, indicated by an AUD score of 2 or more, varied significantly across diagnostic groups (χ2 (3, N=19,647) = 2,483.50, p<0.001). The highest rates were seen in the BDwP group (47.2%), followed by the SCZ (39.3%) and the BD without Psychosis groups (35.9%), all of which were markedly higher than controls (9.6%). Further, the distribution of AUD scores varied considerably across groups (see Figure 1), with higher AUD scores (4–6) reported predominately by SMI participants. While an AUD score of 0 was seen in 81.9% of controls, only 51.8% of BD without Psychosis, 42.2% of BDwP, and 48.9% of Scz participants scored 0. Conversely, a maximum AUD score of 6 was rare among controls (0.8%), but relatively common among BD without Psychosis (7.6%), BDwP (8.6%), and Scz (8.4%) participants. Figure 2 depicts which alcohol use problem screening items were endorsed most frequently for each of the 3 SMI diagnosis groups, as well as the combined SMI group, compared to the control group. Among all participants and groups, ‘drinking more than intended’ was the most commonly endorsed alcohol use problem screening item. Notably, the BDwP group had the greatest endorsement of alcohol use problem screening items, with over 30% of this group endorsing 3 of the other 6 alcohol use problem items, including experiencing accidents or harm under the influence of alcohol, having others criticize their drinking, and drinking first thing in the morning.

Figure 1.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) score distribution by diagnosis

This displays the distribution of AUD scores in participants with bipolar disorder (BD), bipolar disorder with psychosis (BDwP), schizophrenia (Scz), serious mental illness (SMI) and no severe mental illness (controls).

Figure 2.

Participants Endorsing Alcohol Use Problem Screening Items (%)

Among SMI group Q14 was endorsed the highest (38.5%) followed by Q13 (29%), Q12 (27.7%), Q16 (27.2%), Q17 (25.7%) and Q15 (23.0%). When compared by each Dx Q14 was endorsed the most by BD with Psychosis (46.2%), BD without Psychosis (37%) and SZ (36.9%). Among controls Q14 was also endorsed the most (9.8%), followed by Q13 (7.9%), Q12 (6.6%), Q17 (5.7%), Q16 (4.8%) and Q15 (4.3%).

Q12 More than 4/5 drinks/day

Q13 Under influence of alcohol/accident/hurt

Q14 More to drink than intended/calm nerves

Q15 Wanted to quit/cut down

Q16 People annoyed/criticize drinking

Q17 Drink in morning [eye opener]

Linear regression analysis found that the SMI diagnosis was associated with a higher AUD score after controlling for sex, race, and probable TUD The main effect of SMI on AUD score was driven by the combined effects of SCZ, BDwP, and BD diagnoses, each of which significantly increased drinking problems. However, the size of these effects differed by diagnosis. When adjusting for sex, race, and probable TUD, the association of SMI diagnosis with AUD score was greatest for schizophrenia (Beta (B) = 0.141, p<0.001**), followed by BDwP (B = 0.125**) and then BD (B = 0.027**) (see Table 2+3).

Table 2.

Effects of SMI on AUD score, including interactions with sex, race, and probable TUD

| AUD Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size (standardized β) | p-value | ||

| Main Effects | |||

| Any SMI ** | 0.223 | <0.001 | |

| Scz ** | 0.141 | <0.001 | |

| BDwP ** | 0.125 | <0.001 | |

| BD ** | 0.027 | <0.001 | |

| Interactions | |||

| SMI x Sex ** | − 0.073 | <0.001 | |

| SMI x Race | − 0.017 | 0.218 | |

| SMI x Sex x Race * | − 0.029 | 0.001 | |

| SMI x TUD ** | 0.154 | <0.001 | |

Notes: Abbreviations include AUD (alcohol use disorder), SMI (severe mental illness), SCZ (schizophrenia), BDwP (bipolar disorder with psychosis), BD (bipolar disorder), and TUD (tobacco use disorder). Sex, race, age, and TUD were included as covariates in all models.

Significant p<0.05

p<0.001

Table 3. Effects of SMI on AUD score by Sex and Race.

| AUD Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size (standardized β) | p-value | ||

| Main Effect | |||

| Any SMI | |||

| Sex x Race Group | |||

| AA Males** | 0.321 | <0.001 | |

| EA Males** | 0.313 | <0.001 | |

| LA Males** | 0.299 | <0.001 | |

| AA Females** | 0.367 | <0.001 | |

| EA Females** | 0.283 | <0.001 | |

| LA Females** | 0.369 | <0.001 | |

Notes: Abbreviations include AUD (alcohol use disorder), SMI (severe mental illness), AA (African Ancestry), EA (European Ancestry), and LA (Latinx Ancestry). Age and TUD were included as covariates in all models.

Significant p<0.05

p<0.001

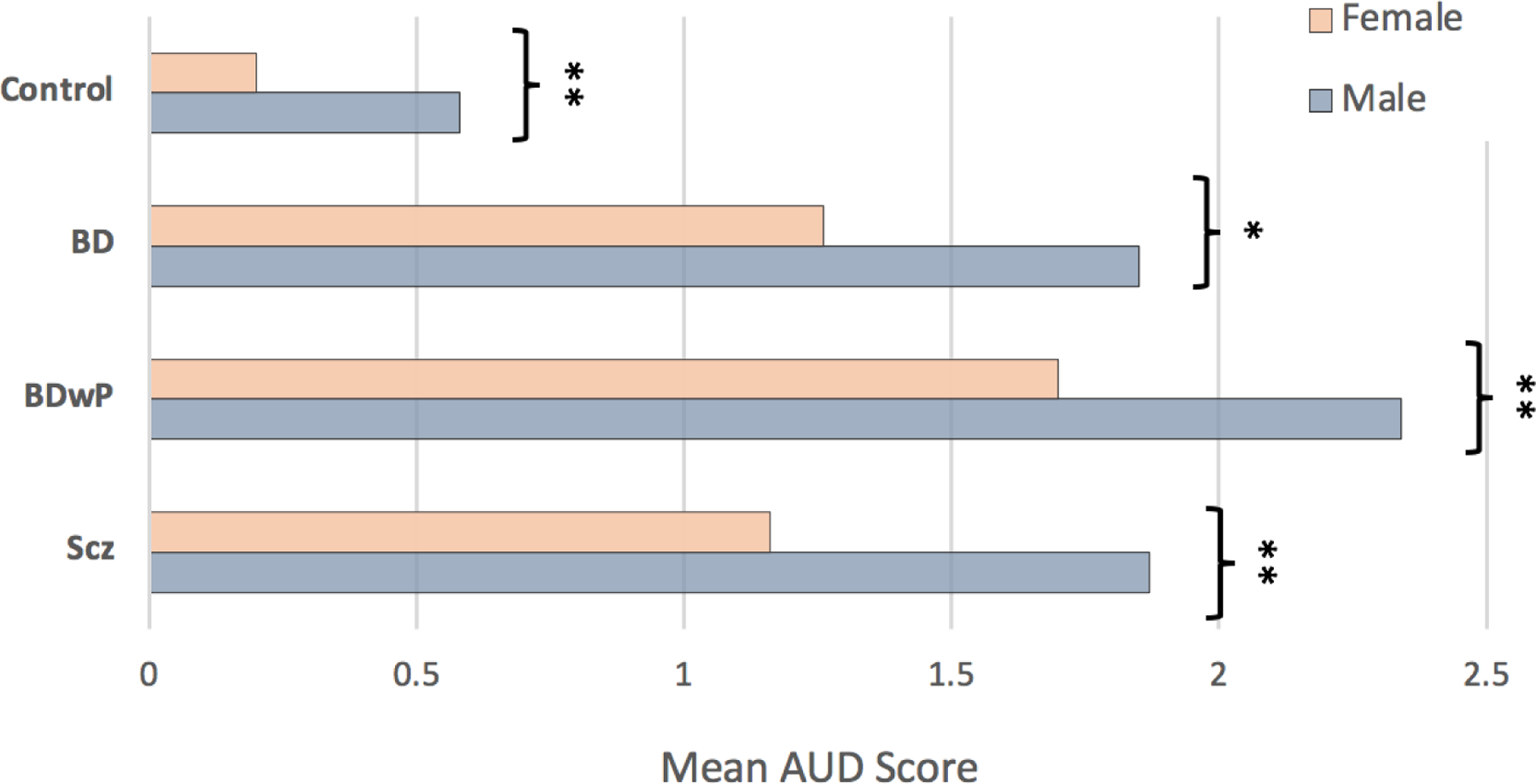

The two-way interaction [SMI x Race] was not significantly associated with AUD score in this model, likely due to the inclusion of all three race categories, two of which (EA and LA) had similar effects. Interestingly, the association of severe mental illness with AUD score was greater in females (B = 0.251**) than in males (B = 0.221**). This reflects a decreased gender gap in alcohol use among SMI cases, relative to controls. That is, while males with SMI drank more than females with SMI, and unaffected males drank more than unaffected females, the difference between males and females was less among those with SMI (see Figure 3). As shown in Table 2, the three-way interaction term [SMI x Sex x Race] was significantly associated with AUD score. This was likely driven by race, AA females and LA females, who displayed the strongest associations between SMI and AUD score (B = 0.367** and B = 0.369**, respectively, see Table 3). Probable tobacco use disorder strengthened the association of SMI diagnosis and AUD score, as indicated by the significant two-way interaction of [SMI x TUD] (see Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mean alcohol use disorder scores in males vs. females, by diagnosis.

Abbreviations include BD (bipolar disorder), BDwP (bipolar disorder with psychosis), and SCZ (schizophrenia). Significant p<0.01 *, p<0.001 **, determined by independent samples t-test.

4. Discussion

Alcohol use disorder is exceedingly common in patients with severe mental illness (SMI) and carries devastating consequences. In one of the largest existing samples of individuals with SCZ or BD ( with and without Psychosis), we found both diagnoses were associated with an increase in alcohol use problems in a diverse racial sample of males and females. Our findings (see Table 2) suggest that a diagnosis of SCZ carries the greatest risk for AUD (B = 0.141, p<0.001), followed by BDw/P (B = 0.125, p<0.001), and then BD (B =0.027, p<0.001). In addition, there was a notable increase in severity of alcohol use as measured by increasing CAGE scores for those with each SMI compared to controls. Less than 10% of controls answered 2 or more questions ‘yes’ on the CAGE for AUD while 47.3% BDw/P, 39.3% SCZ and 36% BD did so (Figure 1–2). The association of SMI with problematic alcohol consumption also varied significantly based on participants’ sex, race, and tobacco use history. Population surveys have yielded broad ranges of AUD prevalence in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder that overlap considerably (Degenhardt et al., 2001; Di Florio et al., 2014; Montross et al., 2005; Oquendo et al., 2010; Swartz et al., 2006; Toftdahl et al., 2016). Using an AUD score of 2 or more to identify participants at high risk for AUD, in accordance with the CAGE instrument (Ewing, 1984). After adjusting for sex, race, and tobacco use, we found that a schizophrenia diagnosis carried the greatest risk for AUD (Table 2). Heightened risk for AUD in the context of schizophrenia, relative to bipolar illness, may be driven by more chronic, persistent, and severe psychotic symptoms, unique cognitive aberrations in domains of decision-making and reward processing, as well as socio-economic disadvantage.

In the present sample, psychosis was associated with greater AUD risk in those with bipolar disorder, mirroring similar findings in the general population and in unipolar depression (Pignon et al., 2020). This is likely a bidirectional relationship, in which alcohol use is both driven by psychosis and can precipitate or worsen positive symptoms (McGrath et al., 2016).

In line with well-established general population trends (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Keyes et al., 2008), we found that females in our sample drank less than males (see Figure 3). However, SMI was more strongly associated with AUD risk in females than males, reflected by the significant effects of the interaction term [Sex x SMI] (see Table 2). This indicates that, although women drink less overall, in the context of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, they are not far behind their male counterparts. This is consistent with previous data suggesting that women more often drink to ameliorate dysphoria and stress (Lipschitz et al., 2000; Pedrelli et al., 2016), common experiences in those living with a severe psychiatric disorder (Betensky et al., 2008).

Further, we found that females with SMI who identify as AA or LA may be particularly vulnerable to alcohol use disorder, displaying larger effect sizes ( AA females ES= .367, males ES=.321 and LA females ES = .369, males ES=.299 in our regression models than their EA and male counterparts (table 3). While it is often reported that Whites are at greater risk of AUD in the general population, in line with findings from Kilbourne et al. (Kilbourne et al., 2005) and Montross et al. (Montross et al., 2005), our data suggest that this is not the case in SMI, where minority individuals may suffer greater proneness to AUD. Although we found that the interaction term [Sex x Race x SMI] had a significant effect on AUD score, when sex was not considered, race did not significantly impact the model (see Table 2). It is possible that intersecting forms of social disadvantage and discrimination experienced by racial minorities, women, and individuals living with mental illness additively increase one’s risk for alcohol use disorder (Holley et al., 2016; Mereish & Bradford, 2014; Vu et al., 2019). Vulnerability to AUD among racial minorities may be driven by social disadvantage, psychological effects of perceived discrimination, and reduced access to psychiatric services (Mulia et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2007). Although minority individuals are more likely to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder (Schwartz & Blankenship, 2014), which according to our analysis disproportionately increases their risk of AUD, they are less likely to receive effective treatment for either illness (Oluwoye et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2007).

Widespread abuse of alcohol among individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders may be explained through multiple mechanisms. Genome-wide association studies indicate a shared polygenic liability for severe mental illness and AUD, finding collections of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) common to schizophrenia (Hartz et al., 2017) and bipolar disorder (Reginsson et al., 2018) are also associated with AUD in those without these disorders. Further, individuals with SMI may be more vulnerable to the reinforcing effects of alcohol, reflected in aberrant dopaminergic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic transmission, all of which are implicated in ethanol intoxication, along with altered frontal cortical reward network activity (Ashok et al., 2017; Benes, 2001). Meanwhile, insufficient inhibitory tone from frontal cortical regions may contribute to impulsivity, impaired decision making, and difficulty modulating harmful drinking behaviors in individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Gold et al., 2008; Hartwell et al., 2009; Heerey et al., 2008; Shurman et al., 2005). While it is likely that predisposition to chemical addiction is a fundamental component of SMI, premorbid alcohol misuse is also common and may interact with one’s genetic vulnerability to give rise to psychotic illness (Drake & Mueser, 2002).

Adverse socioenvironmental factors may interact with this biological diathesis to addiction, shaping it’s development and trajectory. Individuals suffering from SMI often report drinking as a means to ameliorate dysphoria connected with poverty, housing instability, social immobility, and discrimination (Drake & Mueser, 2002). This is consistent with our finding on the pronounced effects of SMI on AUD risk among racial/ethnic minority females, faced with unique intersectional disadvantage. Peer influence may also propagate alcohol use among individuals with SMI, who often inhabit social networks where alcohol abuse is normalized, and can function as a vehicle for social engagement (Drake et al., 2002; Drake & Mueser, 2002). Further, traumatization and posttraumatic stress disorder, both independent risk factors for AUD (Smith & Cottler, 2018), occur at vastly higher rates among those with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Levit et al., 2021; Mueser et al., 1998) and may contribute to the pervasiveness of dual diagnoses (Regier et al., 1990).

Our findings confirm past reports that in psychiatric samples, both alcohol and tobacco use are markedly increased and strongly associated with one another (Heffner et al., 2012; Kavanagh et al., 2004). We found that probable TUD strengthened the association between SMI and AUD score, suggesting that patients with SMI who use tobacco represent a population that is particularly vulnerable to AUD. The association between AUD and TUD may arise from overlapping genetic risk factors and common alterations in mesocorticolimbic dopamine signaling (Vink et al., 2014). Smoking may, therefore, serve as a proxy measure for predisposition to addiction, explaining why SMI cases who smoke so often abuse alcohol. In addition, nicotine may ameliorate alcohol withdrawal symptoms through inhibition of withdrawal induced upregulation of GABAA receptors (Dani & Harris, 2005). These interactions are of considerable consequence, as alcohol and tobacco use contribute to the dramatically increased burden of medical morbidity and mortality associated with psychotic illness (Callaghan et al., 2014; Hjorthøj et al., 2015).

4.1. Limitations

Although our participants were drawn from an array of urban, suburban, and rural communities across the country, the present study is not a population survey and may not be representative of the US population. However, participants were recruited on the basis of a probable SMI diagnosis, allowing for a larger clinical sample than is typically seen in population surveys (Grant et al., 2015; Hasin & Grant, 2015; Regier et al., 1990). Voluntary recruitment invariably introduces the potential for selection bias, often leading to greater representation of females, older adults, whites, and socioeconomically advantaged individuals (Patel et al., 2003). The disproportionate number of female participants in our control and bipolar disorder groups (see Table 1) may reflect this effect. However, our analyses controlled for sex, race, and age to account for potential confounding effects of differences in group demographics. While we studied alcohol use in one of the largest cohorts of AA and LA individuals with SMI, further research is needed on other racial/ethnic groups in the US (i.e., Asian American, Pacific Islanders, Mixed Race).

Our AUD data derived from retrospective self-reports, which may be influenced by the cognitive impairments or psychotic processes associated with severe mental illness, as well as by normal processes of forgetting (Magura & Kang, 1996; Saykin et al., 1991). Socially desirable responding may further lead to underreporting of substance abuse (Magura & Kang, 1996; Saykin et al., 1991; Welte & Russell, 1993). However, as a legal and less stigmatized substance, alcohol consumption is often more accurately disclosed than other drug use (Barnea et al., 1987). Further, our AUD measure was drawn from the CAGE questionnaire, whose validity has been well established in both inpatient and outpatient psychiatric populations (Dhalla & Kopec, 2007; Mayfield et al., 1974). Like the CAGE instrument, our substance use questionnaire refers to lifetime alcohol use, but does not differentiate current use, historic use, or years of use. However, AUD among those with SMI is typically a chronic disorder, characterized by relapse and persistence (Bartels et al., 1995), making lifetime AUD a clinically relevant specification.

4.2. Conclusions

In recent decades, the World Health Organization (WHO) has focused on reducing disparities in health through early identification of those at high risk for alcohol problems, catching harmful drinking in primary healthcare settings and implementing behavioral interventions before significant consequences arise (Blas et al., 2010). Shedding light on the degree of risk for alcohol use disorder among different patient populations may prove invaluable in national and international efforts for early identification and treatment of alcohol abuse and dependence. This may be of particular importance in severe mental illness, as AUDs are often overlooked in these patients (Buckley & Brown, 2006; Drake et al., 1990). Our analysis confirmed that risk for AUD is significantly heightened in individuals with SMI, particularly those with psychotic illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychosis. Additionally, we found that one’s sex, racial identity, and tobacco use history interact with AUD risk in psychotic illness. Our findings highlight the need for further work in public health and clinical psychiatry to address the pervasive comorbidity of alcohol use disorder and severe mental illness, directing resources to marginalized minority populations, which may be disproportionately impacted by psychotic illness and concomitant alcohol use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank all the Genomic Psychiatry Cohort domestic and foreign sites for their contribution to the project.

We would like to acknowledge all the GPC collection sites for their efforts with data collection.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01MH104964, R01MH085548).

Role of the Funding Source:

National Institute of Mental Health – participant enrollment and data analysis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

The Authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- Abel KM, Drake R, & Goldstein JM (2010). Sex differences in schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry, 22(5), 417–428. 10.3109/09540261.2010.515205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR (Fourth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok AH, Marques TR, Jauhar S, Nour MM, Goodwin GM, Young AH, & Howes OD (2017). The dopamine hypothesis of bipolar affective disorder: The state of the art and implications for treatment. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(5), 666–679. 10.1038/mp.2017.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo MH, Soares MJ, Coelho I, Dourado A, Valente J, Macedo A, Pato M, & Pato C (1999). Using consensus OPCRIT diagnoses. An efficient procedure for best-estimate lifetime diagnoses. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 175, 154–157. 10.1192/bjp.175.2.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea Z, Rahav G, & Teichman M (1987). The Reliability and Consistency of Self-reports on Substance Use in a Longitudinal Study. British Journal of Addiction, 82(8), 891–898. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb03909.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Drake RE, & Wallach MA (1995). Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 46(3), 248–251. 10.1176/ps.46.3.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes F (2001). GABAergic Interneurons Implications for Understanding Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(1), 1–27. 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00225-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betensky JD, Robinson DG, Gunduz-Bruce H, Sevy S, Lencz T, Kane JM, Malhotra AK, Miller R, McCormack J, Bilder RM, & Szeszko PR (2008). Patterns of stress in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 160(1), 38–46. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blas E, Kurup AS, & World Health Organization (Eds.). (2010). Equity, social determinants, and public health programmes World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Babbin S, Meyer-Kalos P, Rosenheck R, Correll CU, Cather C, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Penn DL, Addington J, Estroff SE, Gottlieb J, Glynn SM, Marcy P, Robinson J, & Kane JM (2018). Demographic and clinical correlates of substance use disorders in first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 194, 4–12. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PF, & Brown ES (2006). Prevalence and Consequences of Dual Diagnosis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(07), e01. 10.4088/JCP.0706e01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, Orlan C, Graham C, Kakouris G, Remington G, & Gatley J (2014). Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 48(1), 102–110. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso BM, Kauer Sant’Anna M, Dias VV, Andreazza AC, Ceresér KM, & Kapczinski F (2008). The impact of co-morbid alcohol use disorder in bipolar patients. Alcohol, 42(6), 451–457. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, & Harris RA (2005). Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nature Neuroscience, 8(11), 1465–1470. 10.1038/nn1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, & Lynskey M (2001). Alcohol, cannabis and tobacco use among Australians: A comparison of their associations with other drug use and use disorders, affective and anxiety disorders, and psychosis. Addiction (Abingdon, England: ), 96(11), 1603–1614. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961116037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla S, & Kopec JA (2007). The CAGE Questionnaire for Alcohol Misuse: A Review of Reliability and Validity Studies. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 33–41. 10.25011/cim.v30i1.447 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Di Florio A, Craddock N, & van den Bree M (2014). Alcohol misuse in bipolar disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis of comorbidity rates. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 29(3), 117–124. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, & Mueser KT (2000). Psychosocial approaches to dual diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26(1), 105–118. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, & Mueser KT (2002). Co-Occurring Alcohol Use Disorder and Schizophrenia. Alcohol Research & Health, 26(2), 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, Hurlbut SC, Teague GB, & Beaudett MS (1990). Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorders in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(1), 57–67. 10.1093/schbul/16.1.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Wallach MA, Alverson HS, & Mueser KT (2002). Psychosocial Aspects of Substance Abuse By Clients With Severe Mental Illness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(2), 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JA (1984). Detecting Alcoholism: The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA, 252(14), 1905–1907. 10.1001/jama.1984.03350140051025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi H, & Hiller-Sturmhöfel S (2006). An Epidemiologic Analysis of Co-Occurring Alcohol and Tobacco Use and Disorders. Alcohol Research & Health, 29(3), 162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Yi H, & Hiller-Sturmhöfel S (2008). An Epidemiologic Analysis of Co-Occurring Alcohol and Drug Use and Disorders. Alcohol Research & Health, 31(2), 100–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Denicoff K, Nolen WA, Kupka R, Leverich GS, Pollio C, Grunze H, Walden J, & Post RM (2003). Gender Differences in Prevalence, Risk, and Clinical Correlates of Alcoholism Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(5), 883–889. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García S, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, López-Zurbano S, Zorrilla I, López P, Vieta E, & González-Pinto A (2016). Adherence to Antipsychotic Medication in Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenic Patients. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 36(4), 355–371. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Waltz JA, Prentice KJ, Morris SE, & Heerey EA (2008). Reward Processing in Schizophrenia: A Deficit in the Representation of Value. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(5), 835–847. 10.1093/schbul/sbn068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, & Hasin DS (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(8), 757–766. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell KJ, Tolliver BK, & Brady KT (2009). Biologic Commonalities between Mental Illness and Addiction. Primary Psychiatry, 16(8), 33–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz SM, Horton AC, Oehlert M, Carey CE, Agrawal A, Bogdan R, Chen L-S, Hancock DB, Johnson EO, Pato CN, Pato MT, Rice JP, & Bierut LJ (2017). Association Between Substance Use Disorder and Polygenic Liability to Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 82(10), 709–715. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz SM, Pato CN, Medeiros H, Cavazos-Rehg P, Sobell JL, Knowles JA, Bierut LJ, Pato MT, & Genomic Psychiatry Cohort Consortium. (2014). Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(3), 248–254. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, & Grant BF (2015). The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: Review and summary of findings. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(11), 1609–1640. 10.1007/s00127-015-1088-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA, Bell-Warren KR, & Gold JM (2008). Decision-Making Impairments in the Context of Intact Reward Sensitivity in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 64(1), 62–69. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner JL, DelBello MP, Anthenelli RM, Fleck DE, Adler CM, & Strakowski SM (2012). Cigarette smoking and its relationship to mood disorder symptoms and co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders following first hospitalization for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 14(1), 99–108. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00985.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle AC, Trull TJ, Watts AL, McDowell Y, & Sher KJ (2020). Psychiatric Comorbidity as a Function of Severity: DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder and HiTOP Classification of Mental Disorders. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(3), 632–644. 10.1111/acer.14284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthøj C, Østergaard MLD, Benros ME, Toftdahl NG, Erlangsen A, Andersen JT, & Nordentoft M (2015). Association between alcohol and substance use disorders and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression: A nationwide, prospective, register-based study. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 2(9), 801–808. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00207-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley LC, Tavassoli KY, & Stromwall LK (2016). Mental Illness Discrimination in Mental Health Treatment Programs: Intersections of Race, Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 311–322. 10.1007/s10597-016-9990-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GE, Large MM, Cleary M, Lai HMX, & Saunders JB (2018). Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990–2017: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 234–258. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GE, Malhi GS, Cleary M, Lai HMX, & Sitharthan T (2016). Comorbidity of bipolar and substance use disorders in national surveys of general populations, 1990–2015: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 321–330. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Waghorn G, Jenner L, Chant DC, Carr V, Evans M, Hemnan H, Jablensky A, & McGrath JJ (2004). Demographic and clinical correlates of comorbid substance use disorders in psychosis: Multivariate analyses from an epidemiological sample. Schizophrenia Research, 66(2–3), 115–124. 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00130-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, & West SA (1994). Pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacology, 114(4), 529–538. 10.1007/BF02244982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Morris DW, Sweeney JA, Pearlson G, Thaker G, Seidman LJ, Eack SM, & Tamminga C (2011). A dimensional approach to the psychosis spectrum between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: The Schizo-Bipolar Scale. Schizophrenia Research, 133(1), 250–254. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, & Hasin DS (2008). Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 93(1–2), 21–29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS, Pincus H, Williford WO, Kirk GF, & Beresford T (2005). Clinical, psychosocial, and treatment differences in minority patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 7(1), 89–97. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Kotov R, Watson D, Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Ruggero CJ, Simms LJ, Widiger TA, Achenbach TM, Bach B, Bagby RM, Bornovalova MA, Carpenter WT, Chmielewski M, Cicero DC, Clark LA, Conway C, DeClercq B, DeYoung CG, … Zimmermann J (2018). Progress in achieving quantitative classification of psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 282–293. 10.1002/wps.20566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit J, Valderrama J, Georgakopoulos P, Brooklyn AA-GPC, Pato CN, & Pato MT (2021). Childhood Trauma and Psychotic Symptomatology in Ethnic Minorities With Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open, 2(1), sgaa068. 10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipschitz DS, Grilo CM, Fehon D, McGLASHAN TM, & Southwick SM (2000). Gender Differences in the Associations Between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Problematic Substance Use in Psychiatric Inpatient Adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(6), 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, & Kang S-Y (1996). Validity of Self-Reported Drug Use in High Risk Populations: A Meta-Analytical Review. Substance Use & Misuse, 31(9), 1131–1153. 10.3109/10826089609063969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield D, Mcleod G, & Hall P (1974). The CAGE Questionnaire: Validation of a New Alcoholism Screening Instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry, 131(10), 1121–1123. 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade L, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Browne MO, Caldas de Almeida JM, Chiu WT, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Have M ten Hu, Kovess-Masfety C, Lim V, C. CW, … Kessler RC. (2016). The bi-directional associations between psychotic experiences and DSM-IV mental disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(10), 997–1006. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15101293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin P, Farmer A, & Harvey I (1991). A Polydiagnostic Application of Operational Criteria in Studies of Psychotic Illness: Development and Reliability of the OPCRIT System. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(8), 764–770. 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320088015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH, & Bradford JB (2014). Intersecting Identities and Substance Use Problems: Sexual Orientation, Gender, Race, and Lifetime Substance Use Problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(1), 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles H, Johnson S, Amponsah-Afuwape S, Finch E, Leese M, & Thornicroft G (2003). Characteristics of Subgroups of Individuals With Psychotic Illness and a Comorbid Substance Use Disorder. Psychiatric Services, 54(4), 554–561. 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montross LP, Barrio C, Yamada A-M, Lindamer L, Golshan S, Garcia P, Fuentes D, Daly RE, Hough RL, & Jeste DV (2005). Tri-ethnic variations of co-morbid substance and alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 79(2), 297–305. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser K, Goodman L, Trumbetta S, Rosenberg S, Osher F, Vidaver R, Auciello P, & Foy D (1998). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 493–499. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE (2009). Disparities in Alcohol-related Problems among White, Black and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(4), 654–662. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (2004). Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(8), 981–1010. 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, Severe JB, Malaspina D, & Reich T (1994). Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(11), 849–859; discussion 863–864. 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwoye O, Stiles B, Monroe-DeVita M, Chwastiak L, McClellan JM, Dyck D, Cabassa LJ, & McDonell MG (2018). Racial-Ethnic Disparities in First-Episode Psychosis Treatment Outcomes From the RAISE-ETP Study. Psychiatric Services, 69(11), 1138–1145. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Liu S-M, Hasin DS, Grant BF, & Blanco C (2010). Increased risk for suicidal behavior in comorbid bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(7), 902–909. 10.4088/JCP.09m05198gry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. (2019). Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Patel MX, Doku V, & Tennakoon L (2003). Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(3), 229–238. 10.1192/apt.9.3.229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pato MT, Sobell JL, Medeiros H, Abbott C, Skar B, Buckley PF, Bromet EJ, Escamilla MA, Fanous AH, Lehrer DS, Macciardi F, Malaspina D, McCarroll SA, Marder SR, Moran J, Morley CP, Nicolini H, Perkins DO, Purcell SM, … Pato CN (2013). The Genomic Psychiatry Cohort: Partners in Discovery. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics : The Official Publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics, 0(4), 306–312. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, Colledge S, Hickman M, Rehm J, Giovino GA, West R, Hall W, Griffiths P, Ali R, Gowing L, Marsden J, Ferrari AJ, Grebely J, Farrell M, & Degenhardt L (2018). Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction (Abingdon, England: ), 113(10), 1905–1926. 10.1111/add.14234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrelli P, Borsari B, Lipson SK, Heinze JE, & Eisenberg D (2016). Gender Differences in the Relationships Among Major Depressive Disorder, Heavy Alcohol Use, and Mental Health Treatment Engagement Among College Students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(4), 620–628. 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignon B, Sescousse G, Amad A, Benradia I, Vaiva G, Thomas P, Geoffroy PA, Roelandt J-L, & Rolland B (2020). Alcohol Use Disorder Is Differently Associated With Psychotic Symptoms According To Underlying Psychiatric Disorders: A General Population Study. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire: ), 55(1), 112–120. 10.1093/alcalc/agz077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, & Goodwin FK (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA, 264(19), 2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reginsson GW, Ingason A, Euesden J, Bjornsdottir G, Olafsson S, Sigurdsson E, Oskarsson H, Tyrfingsson T, Runarsdottir V, Hansdottir I, Steinberg S, Stefansson H, Gudbjartsson DF, Thorgeirsson TE, & Stefansson K (2018). Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder associate with addiction. Addiction Biology, 23(1), 485–492. 10.1111/adb.12496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Mozley LH, Resnick SM, Kester DB, & Stafiniak P (1991). Neuropsychological Function in Schizophrenia: Selective Impairment in Memory and Learning. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(7), 618–624. 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Bond J (2007). Ethnic Disparities in Clinical Severity and Services for Alcohol Problems: Results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(1), 48–56. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RC, & Blankenship DM (2014). Racial disparities in psychotic disorder diagnosis: A review of empirical literature. World Journal of Psychiatry, 4(4), 133–140. 10.5498/wjp.v4.i4.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurman B, Horan WP, & Nuechterlein KH (2005). Schizophrenia patients demonstrate a distinctive pattern of decision-making impairment on the Iowa Gambling Task. Schizophrenia Research, 72(2), 215–224. 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NDL, & Cottler LB (2018). The Epidemiology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 39(2), 113–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Canive JM, Miller DD, Reimherr F, McGee M, Khan A, Van Dorn R, Rosenheck RA, & Lieberman JA (2006). Substance Use in Persons With Schizophrenia: Baseline Prevalence and Correlates From the NIMH CATIE Study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(3), 164–172. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000202575.79453.6e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toftdahl NG, Nordentoft M, & Hjorthøj C (2016). Prevalence of substance use disorders in psychiatric patients: A nationwide Danish population-based study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(1), 129–140. 10.1007/s00127-015-1104-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Hottenga JJ, de Geus EJC, Willemnsen G, Neale MC, Furberg H, & Boomsma DI (2014). Polygenic risk scores for smoking: Predictors for alcohol and cannabis use? Addiction (Abingdon, England: ), 109(7), 1141–1151. 10.1111/add.12491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu M, Li J, Haardörfer R, Windle M, & Berg CJ (2019). Mental health and substance use among women and men at the intersections of identities and experiences of discrimination: Insights from the intersectionality framework. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 108. 10.1186/s12889-019-6430-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxmonsky JA, Thomas MR, Miklowitz DJ, Allen MH, Wisniewski SR, Zhang H, Ostacher MJ, & Fossey MD (2005). Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use in bipolar disorder: Data from the first 2000 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. General Hospital Psychiatry, 27(5), 321–328. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte JW, & Russell M (1993). Influence of Socially Desirable Responding in a Study of Stress and Substance Abuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 17(4), 758–761. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winokur G, Turvey C, Akiskal H, Coryell W, Solomon D, Leon A, Mueller T, Endicott J, Maser J, & Keller M (1998). Alcoholism and drug abuse in three groups—Bipolar I, unipolars and their acquaintances. Journal of Affective Disorders, 50(2–3), 81–89. 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00108-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.