Abstract

Objective:

Assessment of social processes underlying anticipation for recovery-related support from family in the event of a substance problem. We drew from literature on social support, substance use, and social networks to develop a path model connecting emotionally close family relationships, closeness among members in the wider family network (density), previous emotional support exchanges, and anticipated support.

Subjects and Methods:

We used a sample from the 2019 Nebraska Annual Social Indicators Survey (284 adults; 57% female; 94% white; 46.26% living in rural areas) and employed generalized structural equation modeling with logistic regression equations for our binary dependent variable (anticipated support).

Results:

Denser family networks were associated with individuals’ close relations with family (b = .18, p < .001), close family relations were associated with support received by (b = .25, p < .05) and given to (b = .47, p < .001) family, and only support given to family increased the odds of anticipated support (IRR = 4.32, CI = 1.13, 16.48).

Conclusions:

Family-wide dynamics are important for understanding how support exchange relates to anticipated support. Prioritizing efforts to strengthen family relationships and improve the likelihood that at-risk individuals, especially in rural areas, can overcome substance problems is important.

Keywords: anticipated support, substance use, social support, family, density

1. Introduction

Substance use is a widely recognized public health crisis (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2020). Rural America in particular faces rising overdose rates and increasing substance dependence (Dombrowski et al. 2016; National Institute on Drug Abuse 2020). Unfortunately, access to treatment centers is sparse in rural areas (Jones et al. 2015). For example, over 100,000 Nebraskans aged 18-25 who needed treatment were not able to access it in 2018 and 2019, a shortage exacerbated by lack of access to transportation (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2020; Dombrowski and Khan 2016; Palombi et al. 2019). In such circumstances, a lack of formal support makes support from informal sources, like family, even more important for recovery efforts. Indeed, research shows that emotional support and other recovery assistance from family is crucial for sustained abstinence in general (el-Bassell, Chen & Cooper 1998; Strauss & Falkin 2001; McKee et al. 2011; Hiller et al. 2013; Granfield & Cloud 2001; Kumar et al. 2016; Spohr et al. 2019).

Since those who can access support from family have better recovery outcomes, those who anticipate that they could access family support are also better equipped for recovery (see Wethington & Kessler 1986; Krause 1997). This extends to those who are not currently struggling with substance problems but may struggle in the future. We know of no research that examines anticipated support from family in the event of a substance problem, though such inquiry provides important information about the supportive infrastructure in place for individuals who may be at risk, like those in rural areas. Our goal in this paper is to understand the social processes associated with this infrastructure. Below, we discuss predictors of anticipated support generally before contextualizing to substance use and family relationships.

1.2. Past Exchanges as Predictors of Anticipated Support

Research indicates that anticipated support—the expectation that individuals could access support from others should they need (Wethington & Kessler 1986; Krause 1997)—is shaped by past support exchange (Krause 1997), including both given and received support (Thomas 2010). Having received support confirms that support was available and sets the expectation that it will continue to be available (Newland & Furnham 1999; Haber et al. 2007; DeFreese & Smith 2013). Having given support sets the expectation that support will be reciprocated when needed (Plickert, Cote & Wellman, 2007).

Support varies in kind (Thoits 1995), but emotional support is particularly relevant for recovery efforts (el-Bassell et al. 1998; Strauss & Falkin 2001; McKee et al. 2011; Hiller et al. 2013; Kumar et al. 2016). Emotional support refers to empathy, acceptance, and encouragement (Thoits 1995). It is important because substance use is highly stigmatized, which can deter individuals from seeking help (Ayres et al. 2012; Barry et al. 2014; Browne et al. 2016). Emotional support helps offset stigma and faciliates help-seeking (Kozloff et al. 2013). Thus, given and received emotional support exchanges should set the expectation that one could ask for (and would receive) recovery support if needed.

1.3. Family Network Structures as Context for Close Relations

What facilitates emotional support exchanges? Close relationships do because individuals are more motivated to aid those to whom they feel close (Johnson et al. 1993; Reis & Franks 1994; Haber et al. 2007). Indeed, research supports that close family members often provide emotional support that aids recovery efforts (el-Bassell et al. 1998; Strauss & Falkin 2001; McKee et al. 2011; Hiller et al. 2013; Kumar et al. 2016). But what influences emotionally close family relationships?

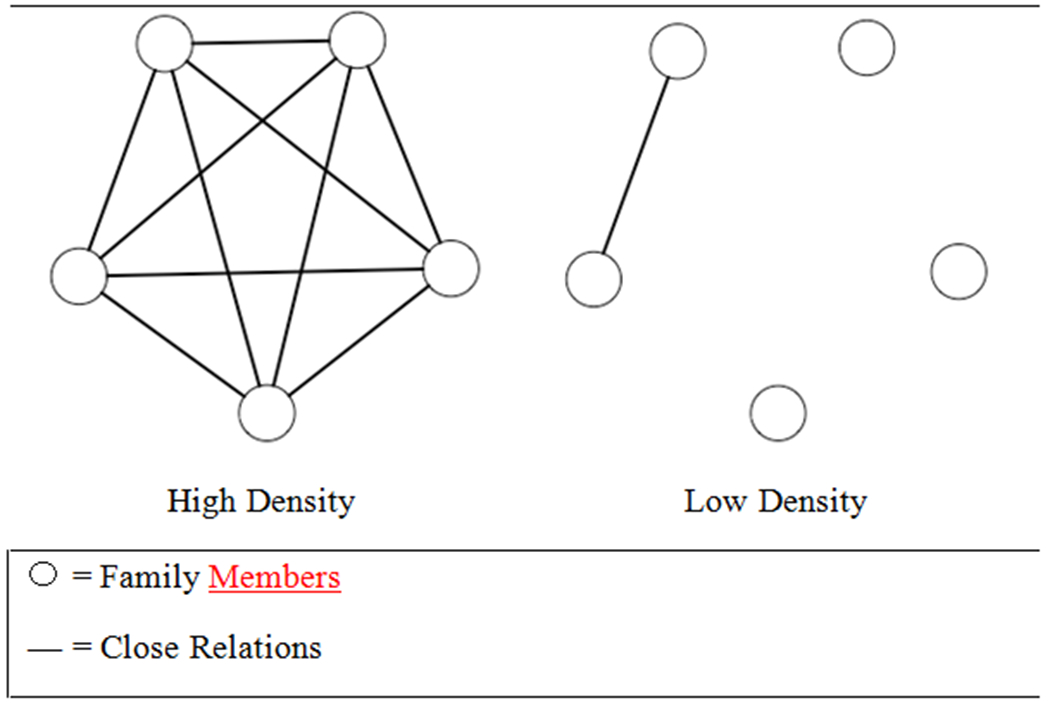

Social relations are embedded within social networks, or wider relational contexts where people are interconnected. Consider the relation between an individual and one of their family members (e.g., spouse, child, parent, etc.). This relationship is embedded within the wider family network, where all other family members themselves share unique relations (Widmer 2016; adams 2019; Smith 2020). Relations among one’s family members provide information about the dynamics within a family network (see Figure 1). Family networks with many connections between members are highly dense networks indicating strong relationships with close emotional bonds (Green et al. 2001; Friedkin 2004). Families with few connections are low in density, indicating weak relations. Family network density influences individuals’ own relations by facilitating strong, positive relationships between them and their family members (Elias 1983). For example, information may be readily shared in a close, tightly knit (high density) family, allowing family members to gain insight into each other’s problems and resolve disputes. These positive dynamics facilitate emotional closeness (Cornwell 2012). By contrast, the sparse nature of an emotionally distant (low density) family may inhibit this relational understanding, preventing individuals from developing close family relations (Meyers, Varkey & Aguirre 2002).

Figure 1.

High versus Low Density Example

1.4. Current Study

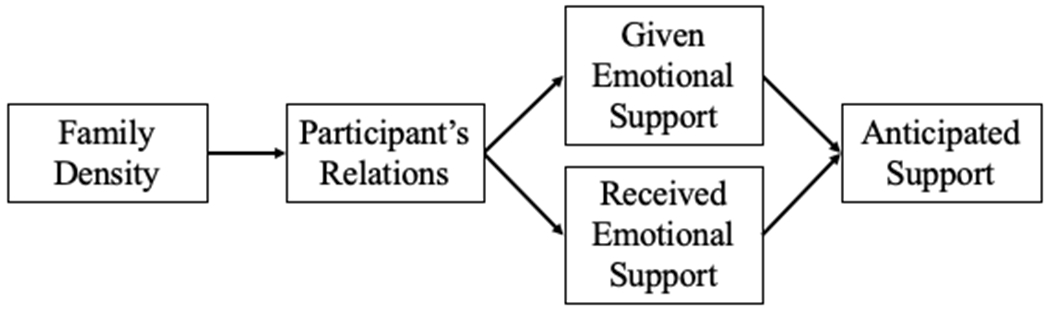

Based on the foregoing, we propose a theoretical model (Figure 2): highly dense networks lead to close emotional relationships which facilitate emotional exchanges; exchanges, in turn, lead to anticipated support.

Figure 2.

Theoretical Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

To test our model, we use data from those within a highly rural area: the 2019 Nebraska Annual Social Indicators Survey (NASIS), an annual omnibus mail survey of Nebraska adults (19 or older). Surveys were distributed to 2,400 addresses which were sampled with an equal probability of selection from a complete list of Nebraskan residential addresses (Smyth et al. 2019). Severe state-wide flooding occurred shortly after surveys were mailed; thus, participation was lower than in previous years (390 surveys were returned; 16.3% response rate). Although generalizability is not possible with these data, they can be used to investigate general support processes, which is the purpose of this work.

The sample used here consists of 284 individuals (of whom, about 46% reported living in a rural area). This includes individuals who answered the dependent variable (78 cases were missing) and provided enough information for a density score to be calculated (28 cases were excluded because they only listed one family member; density cannot be calculated with less than two network members). Missing data on demographic variables was imputed at the mean (e.g., age) or by selecting values of categorical variables at the same rate as they occurred in the dataset (only 14 participants had missing data).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Anticipated Support

Our dependent variable is a binary indicator of anticipated support for a substance problem. Participants were asked: “If you or a close family member needed to seek treatment for substance reasons, would you turn to any of the following for help?” Here, we specifically examine the “Family or friend” option, and participants selected “Yes” (coded as 1) or “No” (coded as 0).

2.2.2. Family Network

Participants provided information about their family networks in response to the following prompt:

Please list the initials (or nicknames) of up to 5 of the most important people in your life, people who are so important to you that you consider them to be part of your family, even when you do not get along. These people may be related to you, but they may also be a close friend, a romantic partner, or a trusted family friend as long as you consider them to be part of your family.

Empty boxes presented below the prompt allowed participants to list up to five family members.

2.2.3. Family Density

Participants were asked: “How close are the people you listed to each other?” All possible combinations were listed (e.g., Person 1 and Person 2, Person 1 and Person 3), and participants indicated if each pair were “Extremely close,” “Quite close,” “Fairly close,” or “Not very close.” Note that these items do not assess relationships between participants and their family members; instead, they uniquely assess the relationships among one’s family members. Pairs reported as being “Extremely close” or “Quite close” were considered to have a close (compared to a not close) relationship.

From this information, we calculated a family density score. We summed the number of close relationships; then, we divided by the total number of possible close relationships (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). The result is a proportion, ranging from 0-1, describing the degree to which one’s family is closely connected. A score of 0 indicates that none of the existing relationships are close, or that one’s family has low density. A score of 1 indicates that all close relationships that could exist actually do, or that one’s family has high density.

2.2.4. Participants’ Relations

Participants were asked: “How close do you feel to each person?” Participants indicated if they were “Extremely close,” “Quite close,” “Fairly close,” or “Not very close” to each family member. Note that these items uniquely describe the participants’ relations, or the connections that exist between them and their family members. Relations reported as being “Extremely close” or “Quite close” were considered to have a close (compared to a not close) relationship. We express participants’ relationship scores as a proportion ranging from 0-1. We summed the number of close relations, then divided by the number of family.

2.2.5. Emotional Support Exchanges

For each family member, participants were asked if, within the past six months, they “received emotional support from them” and if they “provided emotional support to them.” Participants selected “Yes” or “No” for each item for each family member. We express received and given support scores as proportions ranging from 0-1. We separately summed the number of family from whom (then to whom) emotional support was received (and given), then divided each sum by the number of family.

2.2.6. Gender Homophily

We control for gender homophily in our analyses because the more homophilous individuals are, or the more they have in common, the closer they tend to be (Curry & Dunbar, 2013). Participants were asked to indicate if each family member was “Male” or “Female.” If the respondent and the family member were female (or male), the relation was considered homophilous. We express gender homophily as a proportion ranging from 0-1. We summed the number of homophilous relations, then divided by the number of family.

2.2.7. Network Size

We also control for network size, since larger networks provide more access to social resources (Lin 1999). After answering all questions about family elicited by the network prompt, respondents were asked to list other individuals that they considered family. Empty boxes presented below this follow-up prompt allowed participants to list up to ten other family members. Additional information was not collected. We calculated the total network size by summing the number of family in the network and follow-up prompts.

2.2.7. Demographic Variables

Demographic information was asked at the end of the survey. We control for age, gender, education, and marital status because support is negatively related with age, positively related with socioeconomic status indicators like education, and higher for women and those who are married (Thoits 1995). Furthermore, women tend to have closer relations with family members, close relations decline after middle age, and closer relations are associated with marriage and education (Ward 2008; Smith et al. 2015).

Participants were asked “What year were you born?” The number was subtracted from 2019 to assess age in years. For gender, participants indicated if they were “Male” or “Female” (“Female” coded as 1). For education, participants indicated the highest degree they attained. We collapsed the “No diploma” and “High School Diploma/GED” categories in a “High School or Less” category, retained the “Some college, but no degree” category, and collapsed the “Technical/Associated/Junior College,” “Bachelor’s Degree,” and “Graduate Degree” categories into a “Graduated College” category. For marital status, we collapsed the “Married” and “Married, living apart” categories and also collapsed the “Not married, but living with a partner (cohabitating),” “Never married,” “Divorced,” “Widowed,” and “Separated” categories (“Married” and “Married, living apart” coded as 1). We were not able to include race/ethnicity due to an extreme lack of variation on this variable (94% of the sample was white).

2.3. Analytic Strategy

We use generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) with sampling weights for household probability of selection as well as age and gender to estimate the path model in Figure 2. All estimated pathways were linear except for the logistic regression equations on our binary dependent variable. Network size, gender homophily, age, gender, education, and being married were included as controls and were estimated on participants’ relations as well as given, received, and anticipated support. Stata 15 (StataCorp 2017) was used to estimate the model.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for all variables. On average, the sample is about 57 years old, and about 57% is female. The sample is highly educated, as nearly 69% completed a college degree of some kind. About 63% of the sample is married. On average, individuals listed nearly five family members for the first prompt and nearly eight in total. Though family density (.54), and gender homophily (.51), were moderate, individuals reported close relations with nearly all family (.88). On average individuals indicated giving more support to more of their family (.64) than receiving (.54). Majority (72.54%) of the sample reported anticipating family support for a substance problem.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 284)

| M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 56.70 (14.93) | 0-1 |

| Gender | 0.56 (0.50) | 0-1 |

| Education | ||

| High School or Less | 0.12 (0.33) | 0-1 |

| Some College | 0.19 (0.39) | 0-1 |

| Graduated College | 0.69 (0.46) | 0-1 |

| Married | 0.63 (0.48) | 0-1 |

| Anticipated Support | 0.73 (0.45) | 0-1 |

| Family Density | 0.54 (0.33) | 0-1 |

| Participant’s Relations | 0.88 (0.22) | 0-1 |

| Given Support | 0.64 (0.36) | 0-1 |

| Received Support | 0.54 (0.38) | 0-1 |

| Family Members Listed | 4.73 (0.68) | 2-5 |

| Full Network Size | 798 (4.06) | 2-15 |

| Gender Homophily | 0.51 (0.23) | 0-1 |

3.2. GSEM Results

Table 2 shows the generalized structural equation model (GSEM) results. Family density shows a significant coefficient on participants’ relations (b = .18, p < .001). Participants’ relations, in turn, show significant coefficients on given (b = .25, p < .05) and received (b = .47, p < .001) support. Given support shows a significant coefficient on anticipated support (IRR = 4.32, CI = 1.13, 16.48), but received support does not (IRR = 1.01, CI = 0.29, 3.47).

Table 2.

Unstandardized Generalized Structural Equation Model Results (N = 284)

| Close Relations | Given Support | Received Support | Anticipated Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | IRR (CI) | |

| Family Density | 0.18*** (0.04) | |||

| Participant’s Relations | 0.25** (0.10) | 0.47*** (0.09) | ||

| Given Support | 4.32* (1.13, 16.49) | |||

| Received Support | 1.01 (0.29, 3.47) | |||

| Full Network Size | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) |

| Gender Homophily | −0.08 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.10) | 0.14 (0.11) | 5.12 (0.94, 28.03) |

| Age | −0.01 (0.00) | −0.01*** (0.00) | −0.01*** (0.00) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) |

| Woman | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.61 (0.31, 1.18) |

| Education | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.03) | 1.05 (0.65, 1.70) |

| Married | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.05) | 1.32 (0.64, 2.70) |

|

| ||||

| Error Variance | ||||

| Participant’s Relations | 0.11 (0.01) | |||

| Given Support | 0.11 (0.01) | |||

| Received Support | 0.11 (0.01) | |||

|

| ||||

| Error Covariance | ||||

| Given Support, Received Support | 0.06*** (0.01) | |||

Note. Model was estimated with sample weights for household probability of selection as well as age and gender in order to more closely resemble the Nebraska population.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Since family density, participants’ relations, and given support are proportions, the associated coefficients are interpreted like other binary predictors (e.g., referencing a score of 1 compared to 0). For example, compared to those with families that are not dense (i.e., no family members are close), individuals with families that are maximally dense (i.e., all family members are close) show an increase of .18 (or 18%) in the proportion of family members with whom they themselves are close. Similar interpretations follow for participants’ relations on given and received support. Anticipating support is interpreted as an odds ratio. Compared to those who gave no emotional support to any family, the odds of anticipating support are over four times higher for those who gave emotional support to all family.

Finally, out of all control variables (network size, gender homophily, age, gender, education, and being married), only age shows significant coefficients. Age is negatively associated with given (b = −.01, p < .001) and received (b = −.01, p < .001) support, meaning that with each one-year increase in age, the proportion of family members with whom support is exchanged decreases by .01. In short, older adults exchange emotional support with fewer family than younger adults.

4. Discussion

The goal of this paper was to understand the social processes associated with anticipated support from family in the event of a substance problem. We know of no research that examines this, though it is especially important in rural America—such as much of Nebraska—which exhibits rising overdose rates and substance dependence exacerbated by the lack of access to formal treatment (Jones et al. 2015; Dombrowski and Khan 2016; National Institute on Drug Abuse 2020; Palombi et al. 2019). In such settings, support from family is even more important, and those who expect that they would have access family support are better equipped for recovery should they find themselves struggling with a substance problem (see Wethington & Kessler 1986; Krause 1997).

To address this, we drew from research on social support, substance use, and social networks. We proposed a model where dense relationships among one’s family members facilitates close relations between an individual and their family members, close relations faciliate emotional support exchange, and emotional support exchange facilitates anticipation of recovery-related support from family. Testing this model on a highly rural sample of Nebraskans, we found support for these relationships. Family density was associated with closer relations between participants and their family, which was associated with participants’ past given and received emotional support exchanges. However, only having given emotional support was associated with a greater likelihood of anticipating support.

Though we found overall support for our model, our data are limited in several ways. The data do not contain information about participants’ (or their family’s) past or current substance use, and our dependent variable does not capture the kind of recovery support (e.g., emotional) that is anticipated, nor from whom. We also were not able to assess the effect of race/ethnicity as the majority of our sample was white. Access to this information would allow us to corroborate if certain individuals anticipate differential access to kinds/sources of recovery support (el-Bassell et al. 1998; Strauss & Falkin 2001; McKee et al. 2011) and would also help us further tease out who does and does not have supportive family relations (and by extension, who does and does not anticipate they would have recovery support) (Latkin et al. 1996; Hiller et al. 2013). It likely would not, however, change the basic structure of relationships we found, though research should verify this with larger, representative samples.

Nonetheless, our results carry important implications. First, they provide evidence for processes that well-position individuals for recovery should they need it. Close relationships with family and expectations for reciprocity (following from having given support) appear particularly important among our sample. Second, our results underscore the importance of considering family-wide dynamics for these processes, as family context sets the stage for individuals’ own relationships and exchanges with family members (Elias 1983; Green et al. 2001; Widmer 2006). Together, this information highlights areas of focus for preventative community action. To improve the likelihood that at-risk individuals overcome substance problems, communities can prioritize partnerships in which families, schools, and local service organizations coordinate efforts to promote strong family relationships (Epstein & Sanders 2002). Efforts may include support groups, workshops, or other events designed to encourage supportive exchanges and improve family bonds (O’Connor 2003). These efforts may strenghten supportive infrastructure generally, but they would be especially beneficial for those residing in rural areas with limited access to formal sources of recovery-related support.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant P20 GM130461. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- adams jimi. (2019). Gathering Social Network Data. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres RM, Eveson L, Ingram J, & Telfer M (2012). Treatment experience and needs of older drug users in Bristol, UK. Journal of Substance Use 17(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, & Goldman HH (2014). Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: Public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 65(10), 1269–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne T, Priester MA, Clone S, Iachini A, DeHart D, & Hock R (2016). Barriers and facilitators to substance use treatment in the rural south: A qualitative study. Journal of Rural Health 32, 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2020. “2018-2019 National surveys on drug use and health: Model-based estimated totals (in thousands) (50 states and the District of Columbia)”. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD. Retrieved September 14, 2021 (https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2018-2019-nsduh-state-prevalence-estimates). [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B (2012). Spousal network as a basis for spousal support. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(2), 229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry O, & Dunbar RIM (2013). Do birds of a feather flock together?: The relationship between similarity and altruism in social networks. Human Nature, 24, 336–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFreese JD, & Smith AL (2013). Teammate social support, burnout, and self-determined motivation in collegiate athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14, 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski K, Crawford D, Khan B, & Tyler K (2016). Current rural drug use in the Midwest. Journal of Drug Abuse, 2(3), 1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski K, & Khan B (2016). The scope and scale of rural drug use in Nebraska. In Dombrowski K & Gocchi-Carrasco K (Eds.), Reducing health disparities: Research updates from the field (2nd ume, pp. 59–77). Syron Design Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Elias N (1983). The court society. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- el-Bassell N, Chen D, & Cooper D (1998). Social support and social network profiles among women on methadone. Social Service Review, 72(3), 379–491. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL, & Sanders MG (2002). Family, school, and community partnerships. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting, Volume 5, Practical Issues in Parenting (pp. 407–437). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Friedkin NE (2004). Social cohesion. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 409–425. [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, & Cloud W (2001). Social context and “natural recovery:” The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(11), 1543–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LR, Richardson DS, Lago T, & Schatten-Jones EC (2001). Network correlates of social and emotional loneliness in young and older adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(3), 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Haber MG, Cohen JL, Lucas T, & Baltes BB (2007). The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller S, Syvertsen J, Lozada R, & Ojeda VD (2013). Social support and recovery among Mexican female sex workers who inject drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(1), 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Hobfoll SE, & Zalcberg-Linetzy A (1993). Social support knowledge and behavior and relational intimacy: A dyadic study. Journal of Family Psychology, 6, 266–277. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, & McCance-Katz E (2015). National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff N, Cheung AH, Ross LE, Winer H, Ierfino D, Bullock H, & Bennett KJ (2013). Factors influencing service use among homeless youths with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services, 64(9), 925–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (1997). Received support, anticipated, support, social class, and mortality. Research on Aging, 19(4), 387–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PC, McNeeley J & Latkin CA (2016). ‘It’s not what you know but who you know’: Role of social capital in predicting risky injection drug use behavior in a sample of people who inject drugs in Baltimore City. Journal of Substance Use, 21(6), 620–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Mandell W, Vlahov D, Oziemkowska M, & Celentano D (1996). People and places: Behavioral settings and personal network characteristics as correlates of needle sharing. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 13(2), 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N (1999). Social networks and status attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), 467–487. [Google Scholar]

- McKee LG, Bon-Miller MO, & Moos RH (2011). Depressive symptoms, friend and partner relationship quality, and posttreatment abstinence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(1), 141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SA, Varkey S, & Aguirre AM (2002). Ecological correlates of family functioning. American Journal of Family Therapy, 30(3), 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). Nebraska: Opioid-involved deaths and related harms. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state/nebraska-opioid-involved-deaths-related-harms [Google Scholar]

- Newland J, & Furnham A (1999). Perceived availability of social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 659–663. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DL (2003). Toward empowerment: Revisioning family support groups. Social Work With Groups, 25(4), 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Palombi L, Hawthorne AN, Irish A, Becher E & Bowen E (2019). “One out of ten ain’t going to make it:” An analysis of recovery capital in the rural upper Midwest. Journal of Drug Issues 49(4), 680–702. [Google Scholar]

- Plickert G, Cote RR, & Wellman B (2007). It’s not who you know, it’s how you know them: Who exchanges what with whom? Social Networks, 29(3), 405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Reis Harry T., & Franks P (1994). The role of intimacy and social support in health outcomes: Two processes or one? Personal Relationships, 1, 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KE, O’Rourke A, White RH, Park JP, Musci RJ, Kilkenny ME, Sherman SG, & Allen ST (2020). Polysubstance use in rural West Virginia: Association between latent classes of drug use, overdose, and take-home naloxone. International Journal of Drug Policy, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EJ, Marcum CS, Boessen A, Almquist ZW, Hipp JR, Nagle NN, & Butts CT (2015). The relationship of age to personal network size, relational multiplexity, and proximity to alters in the western United States, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 70(1), 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA (2020). The continued relevance of ego network data.” In Light R & Moody J (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Social Networks. (pp. 170–187). [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, Witt-Swanson L, Deng S, Kerr M, Meiergerd K, Benes R, Lamer S, Stallworth G, Yapp M, Predmore D, & Slagle B (2019). 2019 Winter NASIS methodology report. Bureau of Sociological Research, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://bosr.unl.edu/Winter%20NASIS%2019_Methodology%20Report_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Spohr SA, Livingston M, Taxman FS, & Walters ST (2019). What’s the influence of social interactions on substance use and treatment initiation? A prospective analysis among substance-using probationers. Addictive Behaviors, 89, 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SM, & Falkin GP (2001). Social support systems of women offenders who use drugs: A focus on the mother-daughter relationship. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 27(1), 65–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR090120.htm

- Thoits PA (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Extra Issue: The State of the Art and Directions for the Future, 53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Patricia A. (2010). “Is it Better to Give or to Receive? Social Support and the Well-being of Older Adults.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 65B(3): 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RA (2008). Multiple parent-adult child relations and well-beingin middle and later life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 63(4), 239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S & Faust K (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications, Volume 8. Cambridge Univeristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, & Kessler RC (1986). Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 27(1), 78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmer ED (2016). Family configurations: A structural approach of family diversity in late modernity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]