Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES) for the prevention of dry eye after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK).

Design

Prospective, single-center, single-blinded, parallel group, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial.

Participants

Between February 2020 and October 2020, patients at the Samsung Medical Center scheduled to undergo PRK to correct myopia were screened and enrolled.

Methods

The participants in the TES group were instructed to use the electrical stimulation device (Nu Eyne 01, Nu Eyne Co) at the periocular region after the operation, whereas those in the control group were to use the sham device. Dry eye symptoms were evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively at weeks 1, 4, and 12 using the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5), and the Standard Patient Evaluation for Eye Dryness II (SPEED II) questionnaire. Dry eye signs were assessed using tear break-up time (TBUT), total corneal fluorescein staining (tCFS), and total conjunctival staining score according to the National Eye Institute/Industry scale. The pain intensity was evaluated using a visual analog scale.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes were OSDI and TBUT.

Results

Twenty-four patients were enrolled and completed follow-up until the end of the study (12 patients in the TES group, 12 patients in the control group). Refractive outcomes and visual acuity were not different between the groups. No serious adverse event was reported with regard to device use. No significant difference in OSDI and SPEED II questionnaires and the DEQ-5 was observed between the groups in the 12th week after surgery. The TBUT scores 12 weeks after the surgery were 9.28 ± 6.90 seconds in the TES group and 5.98 ± 2.55 seconds in the control group with significant difference (P = 0.042). The tCFS and total conjunctival staining score were significantly lower in the TES group than in the control group at postoperative 4 weeks. Pain intensity at the first week was significantly lower in the TES group than in the control group by 65% (P = 0.011).

Conclusion

The application of TES is safe and effective in improving dry eye disease after PRK.

Financial Disclosure(s)

The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

Keywords: Corneal nerve regeneration, Dry eye, Electrostimulation, Refractive surgery

Abbreviations and Acronyms: DED, dry eye disease; DEQ-5, 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire; LLT, lipid layer thickness; NGF, nerve growth factor; OSDI, Ocular Surface Disease Index; PRK, photorefractive keratectomy; SPEED II, Standard Patient Evaluation for Eye Dryness II; TBUT, tear break-up time; tCFS, total corneal fluorescein staining; TES, transcutaneous electrical stimulation; UDVA, uncorrected distant visual acuity

In the second meeting of the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop in 2017, dry eye disease (DED) was defined as a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by loss of tear film homeostasis and other ocular symptoms in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play an etiological role.1 Nerve fibers in the corneal epithelium are responsible for maintaining normal corneal structure and function.2,3 Corneal nerves play a significant role in maintaining tear film stability through tear secretion, the blinking reaction, and corneal wound healing.4,5 However, corneal sensory innervation can be disrupted by various factors, including trigeminal nerve damage, refractive surgery, and chronic contact lens wear.6 A signaling cascade that leads to an inflammatory reaction and reduced lacrimal secretion can ultimately result in DED related to corneal nerve damage.

Dry eye disease related to corneal nerve damage occurs most commonly after refractive surgery. Refractive surgery is known to induce dry eye owing to decreased corneal sensation, reduced tear production, and impaired wound healing after surgery.7, 8, 9, 10 A periodic analysis of the corneal nerve physical condition, corneal sensory function, and DED level of patients who underwent laser surgery demonstrated that the corneal nerve density and corneal sensitivity decreased drastically after laser surgery, and the degrees of eye dryness and pain increased simultaneously.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Although there are signs of improvement over time, a significant part of the corneal nerve does not recover, leading to persistent eye dryness and pain. Accordingly, it is crucial to develop efficient ways to accelerate and improve the wound healing process, thereby avoiding DED that may arise from damage to the structural integrity of the cornea and the disruption of tear secretion.16,17

Many attempts have been made to accelerate or promote wound healing and nerve regeneration with electrical stimulation.18, 19, 20, 21 It has been suggested that the application or enhancement of the electric field can increase the wound healing rate.18 Electrical stimulation affects cell migration and proliferation and accelerates nerve regeneration.20, 21, 22, 23 The promotion of neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and nerve growth factor (NGF) through increased calcium influx into the neurons, has been suggested to help with nerve and tissue regeneration.24,25 In particular, Ghaffariyeh et al26 reported that electrical stimulation after surgery improved corneal nerve recovery in an animal study. Moreover, transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES) around the periorbital regions with DED showed improvement in DED symptoms.27,28

Dry eye after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) is the most common short- or long-term complication and remains a major concern for practitioners.29 As described above, this complication results from corneal nerve damage during PRK. Despite clinical studies showing that periorbital TES improved general DED and ocular pain, the effects of TES in DED related to corneal nerve damage have not yet been evaluated.27,30 Therefore, we postulated the wound healing and nerve regeneration effects of TES and further investigated the efficacy and safety of TES in treating DED related to corneal nerve damage after PRK.

Methods

Patients

This prospective, single-center, randomized, single-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and Samsung Medical Center (SMC 2019-07-166). The study was registered as a clinical trial (KCT0004602) and abided by the CONSORT statement (Supplemental Material 1, available at www.ophthalmologyscience.org).31

The study was conducted at the Samsung Medical Center. Patients scheduled to undergo PRK to correct myopia were screened and enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age 19 to 60 years, refractive error of −0.50 to −7.50 diopters of spherical myopia, astigmatism between 0.00 and 3.00 diopters, and distance visual acuity correctable to ≥ 0.1 logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a history of recurrent corneal erosions, basement membrane disease, or keratoconus; an estimated postoperative residual stromal bed thickness of < 350 μm; uncontrolled systemic diseases, including diabetes mellitus and autoimmune disease, retinal disease, and glaucoma; previous ophthalmic surgery within 6 months; systemic medications known to affect the ocular surface (eg, tetracycline derivative, antihistamines, and isotretinoin); structural lid abnormalities; active ocular inflammation; and pregnancy. On detailed explanation of the study, all patients provided written informed consent. Eligible patients were randomly allocated to the study or control group (Fig 1). The randomization was conducted by computer-generated random number allocation and applied to sequentially enrolled patients. The randomization schedule was predetermined, before commencing participant recruitment, such that the investigator involved in the baseline participant assessment was not involved in the treatment allocation.

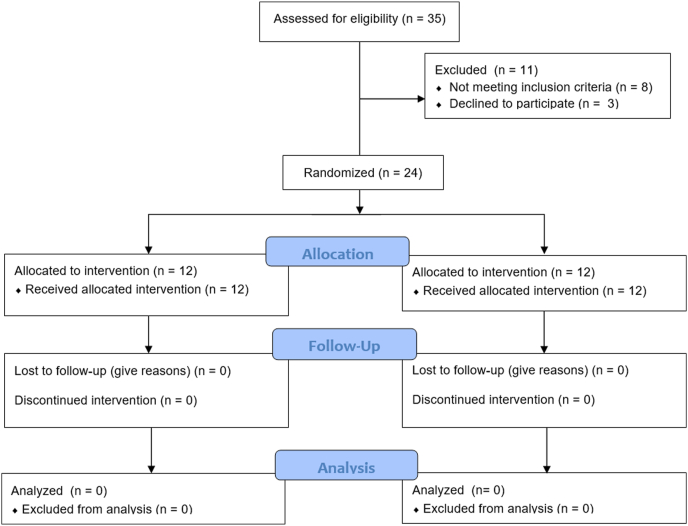

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Surgical Technique

All surgeries were performed by 2 surgeons (T.-Y.C. and D.H.L.) using standardized techniques. Eligible patients were scheduled to undergo bilateral PRK surgery using a WaveLight EX500 excimer laser (Alcon). The correction target was based on the manifest refraction adjusted using the Alcon nomogram, with emmetropia being the target in all patients. A few drops of 20% alcohol were instilled into an 8.0-mm well to create a round epithelial defect. After 25 seconds, the alcohol was removed, and a balanced salt solution was poured to irrigate the cornea. The epithelium was then removed smoothly using a spatula, and laser ablation was performed. The eyes were once again irrigated with a balanced salt solution. Sponges soaked in 0.05% mitomycin-C solution were placed on the eye for 20 seconds, followed by vigorous irrigation with a balanced salt solution. Finally, an AcuVue Oasys (Johnson and Johnson) bandage contact lens was placed on the eye. The same procedure was repeated in the other eye.

Postoperative Medications

Patients with PRK received the following medications: topical moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops (Vigamox, Alcon) 4 times a day for 2 weeks and topical loteprednol 0.5% eye drops (Lotepro) 6 times a day for 2 weeks; this schedule was then tapered for 3 months. All patients were prescribed ketorolac (Acuvail, Allergan), which was permitted to be used up to 3 times a day for unbearable pain on the day of surgery. The artificial tear (hyaluronic acid 0.15%) was also prescribed for their use if needed.

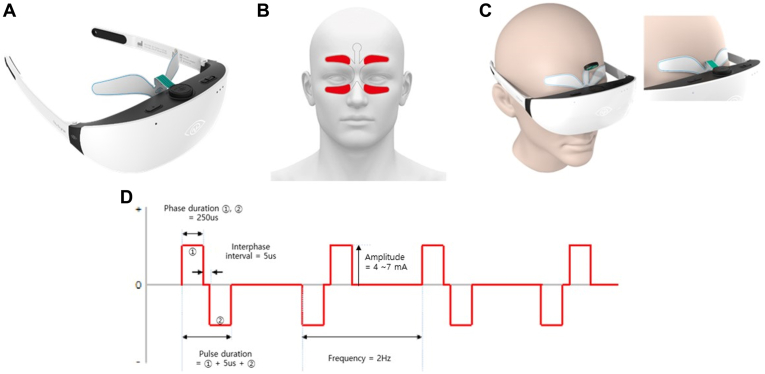

Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical stimulation was administered to the study group, whereas the sham device was assigned to the control group. An electrode patch was designed to provide electrical stimulation at the periocular region, with 4 electrodes placed on the supraorbital and infraorbital regions (Fig 2B). The electrode patch was connected to a gogglelike device (Nu Eyne 01, Nu Eyne Co) (Fig 2A) that output an electric current that subsequently generated electric stimulation on the ocular surfaces and around the associated branches of the trigeminal nerve. A 2-Hz biphasic pulse was used with a phase and an interphase interval of 250 microseconds and 5 microseconds, respectively. For the study group, the amplitude of the pulse was applied between 4 mA and 7 mA and controlled manually by each patient to the maximum tolerable level. The biphasic pulse was alternatively applied with an inverted waveform (Fig 2D) to prevent charge accumulation. The sham device had the same appearance as the real device but only a 0.5-mA biphasic pulse was delivered once every 30 seconds to confirm proper attachment of the device on the participant. The participants were instructed to use the device once a day for 15 to 30 minutes for 2 weeks and then only once a week for 2 weeks until 3 months after the operation.

Figure 2.

A, Electrical stimulator and electrode (NuEyne 01, Nu Eyne Co). B, Examples of electrode attachment. C, Device application. D, Waveform of electrical stimulation.

Patient Evaluation

A complete ophthalmic examination was performed for all patients preoperatively, including uncorrected distant visual acuity (UDVA), best-corrected distant visual acuity, manifest refraction, cycloplegic refraction, slit-lamp microscopy, and fundus examination. After the surgery, patients visited the clinic at postoperative days 1 and 3 and weeks 1, 4, and 12 and received the scheduled examination.

Dry eye signs and symptoms were evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively at weeks 1, 4, and 12. Dry eye symptoms were assessed using the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire, and the Standard Patient Evaluation for Eye Dryness II questionnaire. Dry eye signs were assessed using the tear break-up time (TBUT), Schirmer I test without anesthesia, total corneal fluorescein staining, and total conjunctival staining score according to the National Eye Institute/Industry scale.

The pain intensity was evaluated using a visual analog scale. The visual analog scale was on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 to 10 points, in which 0 corresponded to “no pain” and 10 corresponded to “the worst imaginable pain.” The pain intensity was evaluated before surgery and at postoperative days 1, 3, and 7.

Tear osmolarity tests were performed using a TearLab Osmolarity System (TearLab Corporation).32 Lipid layer thickness (LLT) measurement was performed using a LipiView interferometer (TearScience Inc.) preoperatively and postoperatively after 12 weeks.33 The test for matrix metalloproteinase 9 in the tear film was performed using InflammaDry (Quidel). The test result of InflammaDry was categorized into 5 levels (negative, trace positive, weak positive, positive, and strong positive) and then interpolated to the concentration by comparing with a previous reference (Brujic M, Kadling DL. Making matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels more meaningful. Poster presented at: Global Specialty Lens Symposium, January 21–24, 2016; Las Vegas, NV). Corneal sensitivity was assessed using a Cochet–Bonnet esthesiometer (Harada). “Touch,” “pain,” and “blink” sensations were evaluated and recorded in millimeters.34

Statistical Analysis

This study was an exploratory clinical trial; therefore, we set 10 patients in each group, which is the minimal sample size for evaluating efficacy and safety. Assuming a 20% dropout rate, the target sample size was calculated as 24 subjects. Statistical analyses were performed using Matlab R2018b (MathWorks Inc). The primary outcomes were the OSDI score and TBUT. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted for all tests. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for intragroup comparisons, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for intergroup comparisons. The safety index was defined as the ratio of the postoperative corrected distance visual acuity at 3 months to the preoperative corrected distance visual acuity. The efficacy index was defined as the ratio of postoperative UDVA at 3 months to the preoperative corrected distance visual acuity. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. All tests were 2-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The study was conducted between February 2020 and October 2020. Thirty-five patients were screened, and among these participants, 8 did not meet the criteria, whereas 3 did not agree to the participation terms and conditions. Finally, 24 patients were enrolled in this study, of whom 12 were included in the TES group with real stimulation and the other 12 were included in the control group with sham stimulation. All registered patients completed follow-up until the end of the study. In the TES group, the mean age of the 12 patients was 28.3 ± 4.7 years (range, 19–37 years), and 6 were women. In the control group, the mean age of the 12 patients was 26.6 ± 5.6 years (range, 20–35 years), and 7 were women. The preoperative refractive error did not differ significantly between the 2 groups. Demographics and preoperative data of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and Preoperative Data of Study Participants

| Total Subjects (N = 24) | Study Subjects (n = 12) | Control Subjects (n = 12) | P∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs )† | 27.5 ± 5.0 | 28.3 ± 4.7 | 26.6 ± 5.3 | 0.232 |

| Sex | 0.682‡ | |||

| Male | 11 | 6 | 5 | |

| Female | 13 | 6 | 7 | |

| Spherical error (D)† | 3.88 ± 1.23 | 3.80 ± 1.39 | 3.95 ± 1.20 | 0.694 |

| Cylindrical error (D)† | 1.00 ± 0.67 | 1.00 ± 0.80 | 0.80 ± 0.49 | 0.311 |

| Central corneal thickness (μm)† | 551.8 ± 24.9 | 545.9 ± 22.3 | 557.8 ± 26.4 | 0.101 |

D = diopter.

Student t test.

Value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Chi-square test.

Three months after the procedure, the UDVA in the TES group was 0.015 ± 0.044 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution, whereas that in the control group was 0.010 ± 0.024 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution, with no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.775, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Of the eyes in the TES and control groups, 87.5% and 83.3% had 20/20 or better UDVA, respectively. The spherical and cylindrical error and spherical equivalent also showed no significant differences between the groups. The efficacy index (0.97 in TES group vs. 0.98 in the control group) and safety index were similar between groups (1.17 in the TES group vs. 1.13 in the control group, respectively). Detailed information on the refractive outcomes is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Refractive Outcomes of the Participants at 12 Weeks after the Surgery

| Total Subjects (N = 24) | Study Subjects (n = 12) | Control Subjects (n = 12) | P∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDVA† | 0.012 ± 0.035 | 0.015 ± 0.044 | 0.010 ± 0.024 | 0.775 |

| BDVA† | −0.054 ± 0.073 | −0.061 ± 0.080 | −0.046 ± 0.068 | 0.579 |

| Spherical error (D) | 0.19 ± 0.30 | 0.14 ± 0.26 | 0.24 ± 0.34 | 0.142 |

| Cylindrical error (D) | −0.08 ± 0.21 | −0.06 ± 0.15 | −0.10 ± 0.26 | 0.207 |

| Spherical equivalent (D) | 0.15 ± 0.33 | 0.11 ± 0.26 | 0.19 ± 0.40 | 0.310 |

| Efficacy index | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.775 |

| Safety index | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 0.579 |

BDVA = best-corrected distant visual acuity; D = diopter; logMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; UDVA = uncorrected distant visual acuity.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Visual acuity is presented as logMAR scale.

A total of 73 adverse events were reported during the clinical investigation; 60% of these were associated with visual function, eye dryness, and pain associated with laser epithelial keratomileusis, whereas 40% were related to the use of the investigation device. While using the device, headaches, skin rashes, drowsiness, mild discomfort, and skin breakout were reported. All events occurred in both the study and control groups and were short-lasting and temporary. A single serious adverse event was reported in a patient with pneumothorax, which was concluded to be irrelevant to device use and to this clinical trial. No serious adverse event was reported with regard to device use, thus demonstrating its safety (Table 3). Additionally, all laser epithelial keratomileusis procedures were performed successfully and showed no effect on surgery outcomes on device usage.

Table 3.

Summary of Overall Adverse Events (Safety Population)

| Study Subjects (n = 12) | Control Subjects (n = 12) | Total (N = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of AEs | 27 | 46 | 73 |

| Total number of SAEs | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total number of device-related AEs | 8 (3) | 21 (4) | 29 (7) |

| Headache | 4 (2) | 9 (2) | 13 (4) |

| Skin rash | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Drowsiness | 1 (1) | 5 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Skin discomfort | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Skin breakout | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

AE = adverse event; SAE = serious adverse event. Data presented as number of reported events (number of related participants).

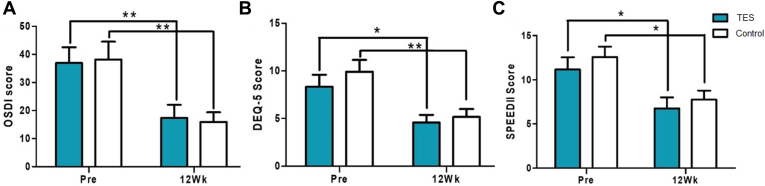

The preoperative OSDI scores were 36.92 ± 19.48 and 38.17 ± 21.98 for the study and control groups, respectively. No significant difference was observed between the groups (P = 0.885, Wilcoxon rank sum test). In both groups, the OSDI scores improved in the 12th week after surgery when compared with the measurements before surgery (Fig 3A). No significant difference was reported between the groups in the 12th week after surgery (P = 0.885, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Similar trends were observed in the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire and Standard Patient Evaluation for Eye Dryness II surveys between the 2 groups in terms of the changes before and after surgery. Both groups improved from before to after surgery, but no significant differences were found between the 2 groups in the 12th week (Fig 3B, C).

Figure 3.

Subjective dry eye symptom scores from study and control groups (Pre: screening before the surgery, 12Wk: 12 weeks after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). A, Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI). B, 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5). C, Standard Patient Evaluation for Eye Dryness II (SPEED II). TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

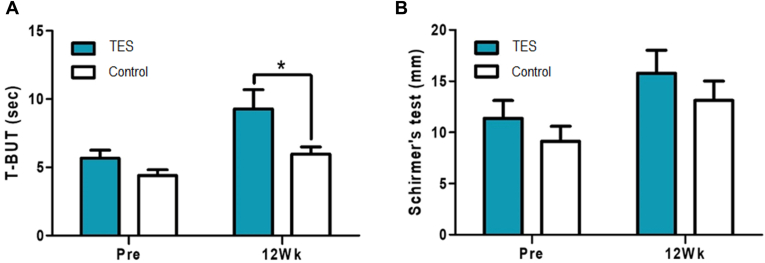

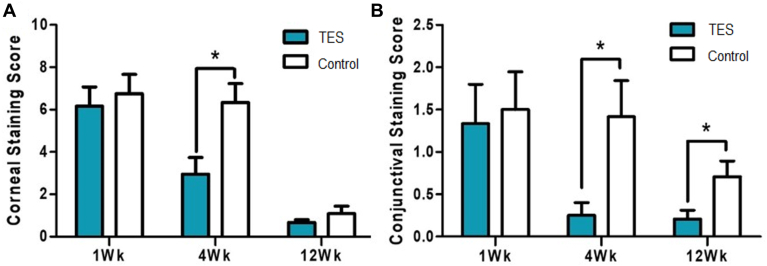

The TBUT scores before the surgery were 5.66 ± 2.88 seconds in the TES group and 4.40 ± 2.04 seconds in the control group and showed no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.081, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The TBUT scores 12 weeks after the surgery were 9.28 ± 6.90 seconds in the TES group and 5.98 ± 2.55 seconds in the control group, with a significant difference of 63% increase in the TES group compared with in the control group (P = 0.042, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig 4A). When the study and control groups were compared using the Schirmer test measured before and 12 weeks after the surgery, the groups improved by 40% with no significant difference between the 2 groups (Fig 4B). Although the corneal fluorescent staining scores 12 weeks after surgery decreased in both the study and control groups to a similar level, the rate of decrease was more rapid in the TES group. The score at 4 weeks after treatment was 52% lower than that at 1 week, with a significant difference from the control group (P = 0.003, Fig 5A). The conjunctival fluorescent staining score decreased more rapidly in the TES group than in the control group. Whereas the TES group showed an 81% decrease 4 weeks after surgery and an 85% decrease 12 weeks after surgery, the control group decreased by 53%, on average, 12 weeks after surgery. The differences from weeks 4 to 12 remained significant (P = 0.0290 at 4 weeks, P = 0.026 at 12 weeks, Fig 5B).

Figure 4.

(A) Tear break-up time and (B) Schirmer test results before and 12 weeks after the surgery (Pre: screening before the surgery, 12Wk: 12 weeks after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test). T-BUT = tear break-up time; TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

Figure 5.

(A) Corneal and (B) conjunctival fluorescent staining scores 1 week (1Wk), 4 weeks (4Wk), and 12 weeks (12Wk) after the surgery compared between the study and control groups. ∗P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test). TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

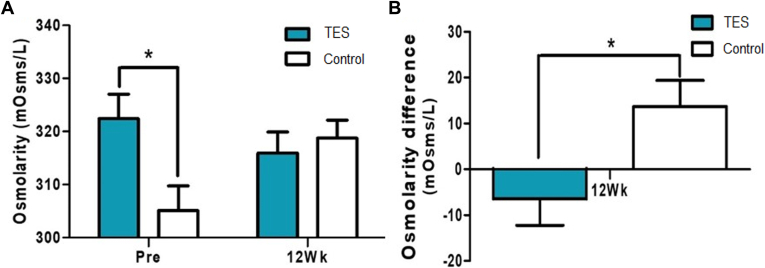

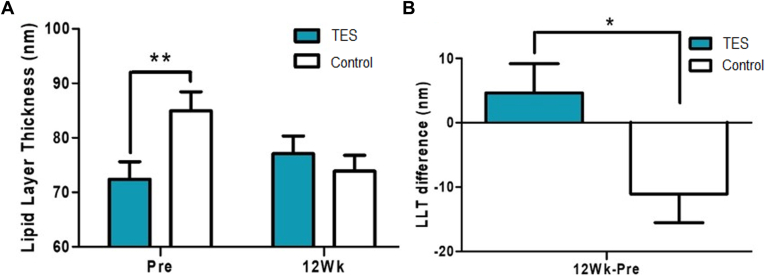

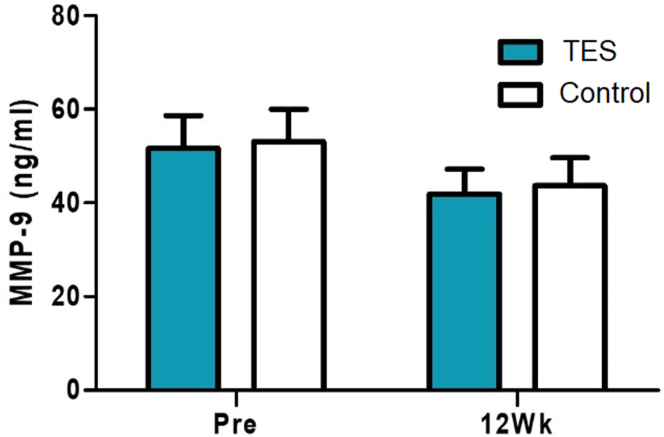

Although randomized with each group of 12 patients, the osmolarity scores were significantly higher before surgery in the TES group (P = 0.022, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig 6A). When comparing the differences between the 2 groups with the scores before surgery and 12 weeks after surgery, osmolarity was decreased in the TES group and increased in the control group (P = 0.030, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig 6B). Although randomized with each group of 12 patients, LLT was significantly higher in the control group before surgery (P = 0.009, Wilcoxon rank sum test). In contrast, the TES group had increased LLT and the control group had decreased LLT 12 weeks after surgery (Fig 7A). When comparing the differences between the 2 groups with the scores before and 12 weeks after the surgery, a significant difference was observed (P = 0.023, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig 7B). Moreover, the concentrations of matrix metallopeptidase 9 were not significantly different between the groups before and 12 weeks after surgery (Fig 8).

Figure 6.

A, Osmolarity test scores before and 12 weeks after the surgery compared between the test and control groups. B, Differences of osmolarity test scores between before and 12 weeks after the surgery of the study and control groups (Pre: screening before the surgery, 12Wk: 12 weeks after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test). TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

Figure 7.

A, Lipid layer thickness (LTT) before and 12 weeks after the surgery compared between the study and control groups. B, Differences of LLT between before and 12 weeks after the surgery of the study and control groups (Pre: screening before the surgery, 12Wk: 12 weeks after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

Figure 8.

Concentrations of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) before and 12 weeks after the surgery compared between the study and control groups (Pre: screening before the surgery, 12Wk: 12 weeks after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

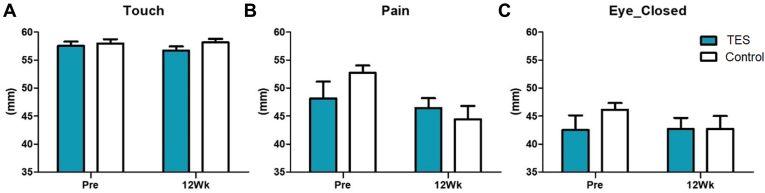

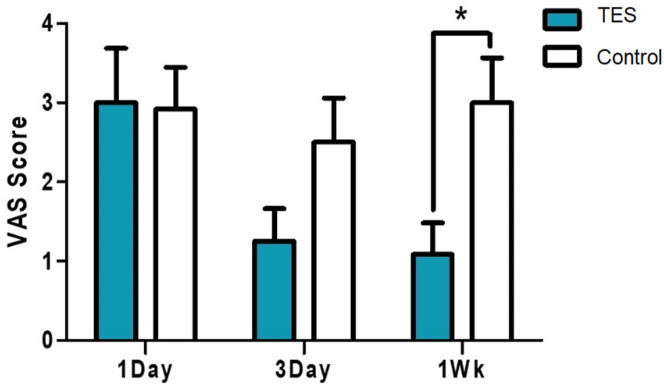

By 12 weeks after surgery, all patients in both groups showed a normal range (55–60 mm) in the esthesiometer test in touch sensation, and no difference was found between the groups (Fig 9). Pain sensation also showed no difference at 12 weeks. The change in pain sensation before and after surgery was smaller in the TES group, although not significant (7.04 mm decrease in the control group vs. 1.67 mm decrease in the TES group, P = 0.214, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The change in the blink sensation showed a similar trend. When questioned, the eye pain score based on the visual analog scale began to decrease 3 days after surgery. By the first week, the pain had decreased by 65% compared with the control group (P = 0.011, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig 10).

Figure 9.

Corneal sensitivity measured with a corneal aesthesiometer before and 12 weeks after the surgery to be compared between the study and control groups (Pre: screening before the surgery, 12Wk: 12 weeks after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). A, Touch: sensing level. B, Pain: pain level. C, Eye_Closed: While the eyes were closed. TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation.

Figure 10.

Pain rating score with VAS change before and after the surgery. (1Day: 1 day after, 3Day: 3 days after, 1Wk: 1 week after the surgery, ∗P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test). TES = transcutaneous electrical stimulation; VAS = visual analog scale.

Discussion

This prospective, randomized, single-blinded, and placebo-controlled clinical trial revealed that TES was effective in improving DED related to corneal nerve damage after PRK. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation after PRK showed significant improvement in subjective symptoms and TBUT scores along with a reduction in eye pain and staining scores. In addition, in the TES group, tear film osmolarity and LLT decreased and increased, respectively, as opposed to the control group, ultimately showing improvements in dry eye status. No serious adverse effects were observed from the application of TES for 12 weeks after PRK.

Several studies have reported the induction of the reinnervation effect through electrical stimulation of the peripheral nerves.24,25,35, 36, 37, 38 Accordingly, electrical stimulation promotes expression of neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and NGF, resulting in faster wound healing and reinnervation.24,25 In an animal study in rats, brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression was upregulated on immediate electrical stimulation of damaged facial and sciatic nerves with crush axotomy.35,36 Other studies report peripheral nerves and Schwann cells were induced to express NGF with electrical stimulation.24,37,38 Interestingly, NGF is responsible for goblet cell differentiation and mucin production, which is required for better tear film maintenance.39 Furthermore, Lambiase et al40 demonstrated that NGF was responsible for corneal wound healing. Additionally, an animal study from our group showed that both NGF expression and corneal nerve density were higher in the TES group than the control group (unpublished data, Young Sik Yoo, et al, 2022). Based on these data and those from previous studies, we hypothesized that TES would be efficient in improving DED related to corneal nerve damage.

Previous clinical studies evaluating the effect of TES showed improvement in dry eye and chronic ocular pain; however, these studies focused primarily on general dry eye and ocular pain populations.27,28,30 Dry eye disease after PRK is different from general DED and is known to be associated with damage to the corneal afferent nerve during PRK, leading to a disruption in sensory input to the ocular surface lacrimal gland feedback system.7 Considering the mechanism of TES, DED related to corneal nerve damage seems to be the best candidate for testing the effects of electrical stimulation. Corneal nerve damage is associated with dry eyes, and dry eye symptoms are common in the setting of corneal nerve injury followed by refractive surgery.41,42 We were able to demonstrate improvement in TBUT and ocular surface staining after TES in this study. Moreover, there was a general decrease in eye dryness measured through subjective questionnaires, such as the OSDI, 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire, and Standard Patient Evaluation for Eye Dryness II (Fig 3), but no difference was found between the groups despite objective dry eye indicators, showing better results in the TES group. This may have originated from the corneal denervation after PRK, which requires a relatively longer time to recover. Changes in subepithelial plexus and stromal trunks are known to appear from 2 to 4 months after surgery, whereas the nerve density continues to improve until 12 months after the surgery.43 Thus, comparing the results 3 months after the surgery in this study may not be long enough to see a difference. Also, patients after PRK experience relatively severe pain compared with the general DED patients throughout the study period. Such an outcome imposes difficulty in detecting improvements in dry eye symptoms by electrical stimulation at the subchronic postoperative stage (2–3 months) of PRK. There is a study reporting no difference in symptom scores between the cyclosporine-treated study group and control group at 2 months after PRK.44 Interestingly, a study showed electrostimulation improved symptom scores in general dry eye wherein the corneal nerve received milder damage.27,28 This suggests DED from relatively mild corneal nerve damage, such as from cataract surgery, would be more feasible to show improvement of symptoms by electrostimulation.

The effects of electric stimulation and neuromodulation on pain relief have been well established.45, 46, 47 In our previous clinical study, oral medication for neuropathic pain was also effective for early stage pain relief after PRK.48 However, the TES group showed lower pain scores 1 week after surgery than the control group and did not differ at days 1 and 3 between the 2 groups in the present study. In general, patients’ complaints associated with pain after PRK were clinical manifestations and developed during the first 3 days. This implies that the lower pain score in the TES group at 1 week might have been because of an improvement in DED related to corneal nerve damage in the study group.

Additionally, the present study did not demonstrate a significant difference in corneal sensitivity between the study and control groups (Fig 9). For a typical study, it is suggested that central corneal sensitivity recovers within 6 months after surgery,9,10 and corneal nerve density takes 12 months or more. Thus, it would take > 12 weeks to monitor and measure the impact of electrical stimulation on corneal sensitivity. Moreover, the results of esthesiometer were almost all in normal range for both groups at 12 weeks. As mentioned above, the changes in subepithelial plexus and stromal trunks after PRK start 2 to 4 months postoperatively; however, it is hard to assume that the corneal nerve had been fully regenerated at 12 weeks in both groups.43 A previous report noted that, although corneal nerve density and length had been decreased 12 months after PRK in in vivo confocal microscopy, corneal sensitivity measured by Cochet–Bonnet esthesiometer recovered to preoperative levels within 1 month after surgery.49 We assume the lack of difference in corneal sensitivity did not directly correlate with the disuse of electrostimulation because the use of esthesiometer had no effect on corneal nerve status in PRK patients. Further study using in vivo confocal microscopy may be required to come up with a deductive conclusion.

An interesting result in this study is that TES increased LLT and decreased tear osmolarity. The lipid layer of the tear film prevents evaporation of the aqueous layer and maintains tear osmolarity, thus playing an important role in tear film stability.50 Inflammation of the cornea and conjunctiva and high osmolarity of the tear film causes inflammation in the meibomian glands, which secrete lipid components.6,51 The improvement of TBUT and both corneal and conjunctival staining on TES, along with an increase in LLT and a decrease in tear osmolarity, suggests TES improves dry eye via various mechanisms. The faster improvement in the corneal and conjunctival staining scores in the TES group seems to be associated with increased mucin and lipid production and reduced tear osmolarity through TES. Additionally, this result may demonstrate that electrical stimulation induces wound healing in the corneal and conjunctival tissue, aligning with the findings of Song et al22 and Ghaffarieh et al.23

There are limitations to this study because this was a pilot study involving a small number of participants. The subjective symptoms did not significantly differ between the TES and control groups, thus suggesting the small number of participants might not have been sufficient to detect these differences in the present study. Increasing the number of participants is necessary for future studies. In addition, the overall study period was relatively short to further investigate the outcome of nerve regeneration. To fully evaluate the effect of TES on DED related to corneal damage after PRK, a larger study with a longer follow-up period is required.

In conclusion, the application of TES is safe and effective in improving DED after PRK. Further studies are needed to evaluate patients with a more general type of DED without exposure to external events such as laser surgery.

Manuscript no. XOPS-D-22-00164R1.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available atwww.ophthalmologyscience.org.

Disclosure(s): All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The authors made the following disclosures:

Supported by a grant of a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government's Ministry of Education (NRF-2020R1A2C2014139; Seoul, Korea) which was received by T.-Y.C., a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HR21C0885), which was received by T.-Y.C.,

HUMAN SUBJECTS: Human subjects were included in this study. This prospective, single-center, randomized, single-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and Samsung Medical Center (SMC 2019- 07-166). The study was registered as a clinical trial (KCT0004602) and abided by the CONSORT statement (Supplemental Material 1 [available at www.ophthalmologyscience.org]).

No animal subjects were included in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: D.H. Kim, P. Kim, Lim, Chung

Analysis and interpretation: Han, Yoo, D.H. Kim, Lim, Chung

Data collection: Han, Yoo, Shin, J.Y. Park, D.H. Kim, P. Kim

Obtained funding: Chung

Overall responsibility: Chung

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Craig J.P., Nichols K.K., Akpek E.K., et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller L.J., Pels L., Vrensen G.F. Ultrastructural organization of human corneal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:476–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benitez-Del-Castillo J.M., Acosta M.C., Wassfi M.A., et al. Relation between corneal innervation with confocal microscopy and corneal sensitivity with noncontact esthesiometry in patients with dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:173–181. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng I.D., Kurose M. The role of corneal afferent neurons in regulating tears under normal and dry eye conditions. Exp Eye Res. 2013;117:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dartt D.A. Neural regulation of lacrimal gland secretory processes: relevance in dry eye diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:155–177. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bron A.J., de Paiva C.S., Chauhan S.K., et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:438–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang R.T., Dartt D.A., Tsubota K. Dry eye after refractive surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:318–322. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinto G.G., Camacho W., Behrens A. Postrefractive surgery dry eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19:335–341. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283009ef8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao C., Stapleton F., Zhou X., et al. Structural and functional changes in corneal innervation after laser in situ keratomileusis and their relationship with dry eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253:2029–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao C., Golebiowski B., Stapleton F. The role of corneal innervation in LASIK-induced neuropathic dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2014;12:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erie J.C., McLaren J.W., Hodge D.O., Bourne W.M. Recovery of corneal subbasal nerve density after PRK and LASIK. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.J., Kim J.K., Seo K.Y., et al. Comparison of corneal nerve regeneration and sensitivity between LASIK and laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK) Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann W.A., Shah C.P., von Mohrenfels C.W., et al. Tear film function and corneal sensation in the early postoperative period after LASEK for the correction of myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:911–916. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-1130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dooley I., D’Arcy F., O’Keefe M. Comparison of dry-eye disease severity after laser in situ keratomileusis and laser-assisted subepithelial keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1058–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darwish T., Brahma A., O’Donnell C., Efron N. Subbasal nerve fiber regeneration after LASIK and LASEK assessed by noncontact esthesiometry and in vivo confocal microscopy: prospective study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1515–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljubimov A.V., Saghizadeh M. Progress in corneal wound healing. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;49:17–45. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dartt D.A. Regulation of tear secretion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;350:1–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2417-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid B., Song B., McCaig C.D., Zhao M. Wound healing in rat cornea: the role of electric currents. FASEB J. 2005;19:379–386. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2325com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang E.T., Zhao M. Regulation of tissue repair and regeneration by electric fields. Chin J Traumatol. 2010;13:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song B., Gu Y., Pu J., et al. Application of direct current electric fields to cells and tissues in vitro and modulation of wound electric field in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1479–1489. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haastert-Talini K., Grothe C. Electrical stimulation for promoting peripheral nerve regeneration. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;109:111–124. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420045-6.00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song B., Zhao M., Forrester J., McCaig C. Nerve regeneration and wound healing are stimulated and directed by an endogenous electrical field in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4681–4690. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghaffarieh A., Ghaffarpasand F., Dehghankhalili M., et al. Effect of transcutaneous electrical stimulation on rabbit corneal epithelial cell migration. Cornea. 2012;31:559–563. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823f8b2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobianchi S., Casals-Diaz L., Jaramillo J., Navarro X. Differential effects of activity dependent treatments on axonal regeneration and neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;240:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenjin W., Wenchao L., Hao Z., et al. Electrical stimulation promotes BDNF expression in spinal cord neurons through Ca(2+)- and Erk-dependent signaling pathways. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:459–467. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9639-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghaffariyeh A., Peyman A., Puyan S., et al. Evaluation of transcutaneous electrical simulation to improve recovery from corneal hypoesthesia after LASIK. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1133–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedrotti E., Bosello F., Fasolo A., et al. Transcutaneous periorbital electrical stimulation in the treatment of dry eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:814–819. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai M.M., Zhang J. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical stimulation combined with artificial tears for the treatment of dry eye: A randomized controlled trial. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:175. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spadea L., Giovannetti F. Main complications of photorefractive keratectomy and their management. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:2305–2315. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S233125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zayan K., Aggarwal S., Felix E., et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the long-term treatment of ocular pain. Neuromodulation. 2020;23:871–877. doi: 10.1111/ner.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D., CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLOS Med. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Versura P., Campos E.C. TearLab Osmolarity System for diagnosing dry eye. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2013;13:119–129. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finis D., Pischel N., Schrader S., Geerling G. Evaluation of lipid layer thickness measurement of the tear film as a diagnostic tool for Meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2013;32:1549–1553. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182a7f3e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaido M., Kawashima M., Ishida R., Tsubota K. Relationship of corneal pain sensitivity with dry eye symptoms in dry eye with short tear break-up time. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:914–919. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma N., Marzo S.J., Jones K.J., Foecking E.M. Electrical stimulation and testosterone differentially enhance expression of regeneration-associated genes. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alrashdan M.S., Sung M.A., Kwon Y.K., et al. Effects of combining electrical stimulation with BDNF gene transfer on the regeneration of crushed rat sciatic nerve. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:2021–2029. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan L., Xia R., Ding W. Short-term low-frequency electrical stimulation enhanced remyelination of injured peripheral nerves by inducing the promyelination effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on Schwann cell polarization. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2578–2587. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J., Ye Z., Hu X., et al. Electrical stimulation induces calcium-dependent release of NGF from cultured Schwann cells. Glia. 2010;58(5):622–631. doi: 10.1002/glia.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambiase A., Manni L., Bonini S., et al. Nerve growth factor promotes corneal healing: structural, biochemical, and molecular analyses of rat and human corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1063–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambiase A., Micera A., Pellegrini G., et al. In vitro evidence of nerve growth factor effects on human conjunctival epithelial cell differentiation and mucin gene expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4622–4630. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galor A., Moein H.R., Lee C., et al. Neuropathic pain and dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2018;16:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levitt A.E., Galor A., Weiss J.S., et al. Chronic dry eye symptoms after LASIK: parallels and lessons to be learned from other persistent post-operative pain disorders. Mol Pain. 2015;11:21. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0020-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alio J.L., Javaloy J. Corneal inflammation following corneal photoablative refractive surgery with excimer laser. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee H.S., Jang J.Y., Lee S.H., et al. Clinical effectiveness of topical cyclosporine a 0.05% after laser epithelial keratomileusis. Cornea. 2013;32:e150–e155. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31829100e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sironi V.A. Origin and evolution of deep brain stimulation. Front Integr Neurosci. 2011;5:42. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2011.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lefaucheur J.P., Ménard-Lefaucheur I., Goujon C., et al. Predictive value of rTMS in the identification of responders to epidural motor cortex stimulation therapy for pain. J Pain. 2011;12:1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson M.D., Burchiel K.J. Peripheral stimulation for treatment of trigeminal postherpetic neuralgia and trigeminal posttraumatic neuropathic pain: a pilot study. Neurosurgery. Jul. 2004;55(1):135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paik D.W., Lim D.H., Chung T.Y. Effects of taking pregabalin (Lyrica) on the severity of dry eye, corneal sensitivity and pain after laser epithelial keratomileusis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106:474–479. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu C., Yu A., Zhang C., et al. Structural and functional alterations in corneal nerves after single-step transPRK. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2022;48:778–783. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sweeney D.F., Millar T.J., Raju S.R. Tear film stability: a review. Exp Eye Res. Dec. 2013;117:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan C. Springer; 2015. Dry eye: A practical approach. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.