Abstract

The growing demand for all-solid flexible, stretchable, and wearable devices has boosted the need for liquid-free and stretchable ionoelastomers. These ionic conducting materials are subjected to repeated deformations during functioning, making them susceptible to damage. Thus, imparting cross-linked materials with healing ability seems particularly promising to improve their durability. Here, a polymeric ionic liquid (PIL) bearing allyl functional groups was synthesized based on the quaternization of N-allylimidazole with a copolymer rubber of poly(epichlorohydrin) and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO). The resulting PIL was then cross-linked with dynamic boronic ester cross-linkers 2,2′-(1,4-Phenylene)-bis[4-mercaptan-1,3,2-dioxaborolane] (BDB) through thiol–ene “click” photoaddition. PEO dangling chains were additionally introduced for acting as free volume enhancers. The properties of the resulting all-solid PIL networks were investigated by tuning dynamic cross-linkers and dangling chain contents. Adjusting the cross-linker and dangling chain quantities yielded soft (0.2 MPa), stretchable (300%), and highly conducting ionoelastomers (1.6 × 10–5 S·cm–1 at 30 °C). The associative exchange reaction between BDB endowed these materials with vitrimer properties such as healing and recyclability. The recycled materials were able to retain their original mechanical properties and ionic conductivity. These healable PIL networks display a great potential for applications requiring solid electrolytes with high ionic conductivity, healing ability, and reprocessability.

Keywords: polymeric ionic liquid, ionoelastomer, vitrimer, self-healing, covalent adaptative network (CAN), boronic ester metathesis, solid polymer electrolyte, ionic conductor

Introduction

Stretchable conducting materials are one of the most demanded components for soft and stretchable electronics. Among the different explored strategies, those relying on ionic charge carriers instead of electrons are especially promising since they can combine the softness, transparency, and stretchability of ionic gels while taking advantage of their intrinsic ionic conduction.1 Ionoelastomers have been introduced recently as liquid-free and stretchable ionic conductors.2−4 They rely on the synthesis of polymeric ionic liquid (PIL) networks in which either ionic liquid-like anions or cations are fixed to the elastomer backbone. Their ionic conductivity is provided by their counterions remaining mobile without the need of any liquid phase, thanks to the high dissociation in the dry state of their ionic liquid-like charge carriers. They are especially promising since they inherently solve the solvent evaporation or liquid leakage issues associated with classical polymer gels such as hydrogels or ionogels. Ionoelastomers can pave the way to the development of all-solid, soft, stretchable, and wearable electrochemical devices and ionotronics.

Nonetheless, with growing environmental awareness and the demand to address multiple problems of traditional polymer networks, tremendous interest has been shown in developing sustainable high-performance polymer materials by combing the facile processability of thermoplastics with the performance advantages of permanent cross-linked thermosets. Fabrication of dynamic reversible polymer networks has become a popular strategy, particularly by introducing thermally activated exchangeable chemical bonds into polymer networks, leading to materials known as vitrimers. Indeed, vitrimers are defined as permanently cross-linked networks with dynamic covalent bonds that allow the network to change its topology while maintaining a constant number of chemical bonds in the system, using a so-called associative mechanism, at all temperatures below degradation.5 Vitrimers demonstrate excellent potentials due to their unique combination of properties, including mechanical properties at service temperatures, self-healing, shape-memory, malleability, and recyclability.5−9 Subsequently to the introduction of vitrimers by Leibler and co-workers in 2011,10 a series of vitrimers have been developed based on different dynamic exchange reaction mechanisms. Exchange reactions such as olefin metathesis,11,12 imine exchange,13−16 disulfide chemistry,17,18 siloxane exchange,19,20 silyl ether metathesis,21 transesterification,10,22,23 transamination of vinylogous amide or urethane,24−26 transcarbonation,27,28 transcarbamoylation,29 transalkylation,30−32 boronic ester exchange,33−35 and so on have been investigated.

While most of the research focuses on the application of vitrimers for reprocessable and recyclable thermoset materials,35−38 there are a few groups reporting the application of dynamic covalent bonds in ionic conductors. Some examples of ionically conducting networks with exogenous lithium salts have been demonstrated. Evans et al. developed healable and recyclable lithium ion-conducting films based on LiTFSI-doped boronic-ester-based poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) networks which demonstrated a maximum conductivity of 3.5 × 10–4 S·cm–1 at 90 °C.39 Kato et al. investigated lithium-ion conduction and adhesive properties of PEO-based polymer electrolyte containing exchangeable disulfide bonds.40 Xue and co-workers synthesized self-healable ionically conducting materials containing hydrogen bonds between urea functional groups and disulfide bonds for lithium-ion batteries.41 These examples of all-solid electrolytes, based on the dispersion of lithium salt in a polymer network, have an extended lifetime and improved cycling stability after deformation or even cracks. Ionically conducting materials with dynamic covalent bonds based on ionogels were also reported.42 Healable and reprocessable gelatin ionogels due to the reversible exchange of imine bonds have been designed for flexible supercapacitors.43 These dynamic ionogels demonstrated an ionic conductivity higher than 1 mS·cm–1 at room temperature, thanks to the use of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate. Alternatively, the research team of Wang et al. reported PU ionogels demonstrating an ionic conductivity of about 14 mS·cm–1 with the presence of 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide.44 The cracked PU ionogels can be readily healed at room temperature and restore their original performance, owing to the dynamic boronic ester cross-linker used in the polymer network. Healable and recyclable boronic ester-based ionogels using 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoro-borate have also been reported.45 Besides these examples of liquid-containing ionic gels, there are only a few examples of reprocessable liquid-free ionic conductors based on PILs without the addition of exogenous salt. In 2015, Montarnal et al. first reported the design of PIL networks exhibiting vitrimer properties using transalkylation reaction.30 The solvent- and catalyst-free polyionic polymer networks were shown to be reprocessable but exhibited limited ionic conductivity (2 × 10–8 S·cm–1 at 30 °C). More recently, Lopez et al. reported the N-transalkylation of 1,2,3-triazolium perfluoropolyether-based PIL networks.46 Ionic conductivities for these polyelectrolytes range from 5 × 10–7 S·cm–1 to 1.1 × 10–6 S·cm–1 at 27 °C. These inspiring examples are particularly interesting for recyclable or healable all-solid polymer electrolytes. However, the ionic conductivities of these systems might be too low for using as ionically conducting materials in soft electronics. In addition, they present an high elastic modulus (8 MPa) with poor stretchability (elongation at break = 20%).30

In this work, liquid-free, stretchable, highly conducting, and reprocessable ionoelastomer are reported (Scheme 1a). Polymeric ionic liquid bearing allyl functional group (PIL allyl) is first synthesized from the quaternization of N-allylimidazole with a high-molecular-weight commercially available poly(epichlorohydrin-co-ethylene oxide) rubber (Scheme 1b). The ionoelastomer is then obtained by the cross-linking of PIL allyl with di-thiol cross-linkers through the thiol–ene click reaction. The presence of dynamic boronic ester function into the cross-linker structure turns the ionoelastomer into a reprocessable and healable vitrimer (Scheme 1a, path i). The introduction of polar poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) dangling chains onto the ionoelastomer main chains is used to enhance the material’s free volume, resulting in tunable mechanical properties and ionic conduction(Scheme 1a, path ii). The effects of dynamic cross-linkers and dangling chains on thermomechanical and ionic conductivities of the materials are first investigated and described. Finally, the vitrimer dynamic properties of the resulting ionoelastomers such as stress relaxation, healing, and recyclability are presented. The unique combination of properties of these dynamic ionoelastomers makes them ideal candidates as ionically conducting materials in soft and stretchable electronics, smart electrochemical devices, and wearables.

Scheme 1. (a) Illustration of the Dithiol Containing Boronic Ester Cross-Linker BDB and the Synthetic Route to Obtain (i) Dynamic PIL-BDB Networks and (ii) PIL-BDB-PEGSH Dynamic Networks with Dangling Chains; (b) Synthetic Route of PIL Allyl; and (c) Network Rearrangement of Ionoelastomers via Boronic Ester Exchange Reaction.

Experimental Section

Materials

The copolymer of poly(epichlorohydrin) and PEO (Hydrin C2000XL, Mw = 8.7 × 106 g·mol–1) is obtained from Zeon chemicals (1H NMR spectrum in Figure S1). Benzene-1,4-diboronic acid was purchased from Apollo Scientific. Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) was purchased from Solvionic. 1,4-Butanediol bis(thioglycolate) (dithiol, DT) and heptane were purchased from TCI Chemicals. Darocur 1173 (2-Hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone), 1-thioglycerol, PEG methyl ether thiol (PEGSH) with an average Mn of 800 g·mol–1, and 1-decanethiol 99% (C10SH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Finally, dimethylformamide (DMF), 1-allylimidazole, and magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO4·7H2O) were purchased from Acros-Organics. Dichloromethane (DCM) was acquired from VWR Chemicals.

All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of PIL Allyl

4 g of C2000XL are solubilized in 23 mL of DMF at 80 °C for 3 h. Once the polymer is solubilized, 10 equivalents of allylimidazole compared to epichlorohydrin function are added. The reaction takes place for 55 h at 90 °C, and the solution becomes orange. 2.2 equiv of LiTFSI salt are dissolved in water (1:2.5 wt). The reaction medium is directly precipitated in LiTFSI solution. The counter-anion of PIL is exchanged from Cl– to TFSI–. The obtained polymer is washed with excess water and then reprecipitated twice in DCM using acetone as the solvent. The obtained final product is dried under dynamic vacuum at 70 °C for 3 days (yield rate 45–65%). The successful synthesis of PIL allyl is confirmed by 1H NMR (Figure S2).

Synthesis of 2,2′-(1,4-Phenylene)-bis[4-mercaptan-1,3,2-dioxaborolane]

The synthesis of dithiol-containing boronic ester cross-linker 2,2′-(1,4-Phenylene)-bis[4-mercaptan-1,3,2-dioxaborolane] (BDB) was reported by Chen et al.34 Benzene-1,4-diboronic acid (3.0 g, 18.1 mmol) and 1-thioglycerol (4.01 g, 37.1 mmol) are dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (80 mL) and water (0.1 mL). 5 g of magnesium sulfate is added to the mixture. After stirring at room temperature for 24 h, the mixture is filtered and concentrated. The resulting white solid is purified by repeatedly filtering and washing with heptane (yield 80%). The successful synthesis of BDB is explicitly confirmed by 1H NMR (Figure S3).

Preparation of Cross-Linked PIL Allyl Networks

PIL allyl is first dissolved in acetone [msolvent = 2 × (mPIL allyl + mBDB or mDT)] before introducing thiol precursors (DT or BDB, PEGSH or C10SH). 2 wt % of photoinitiator Darocur relative to the total weight of PIL allyl and thiol precursors is then added into the vial. The mixture is cast into a mold consisting of two glass plates separated by a 0.5 mm thick Teflon spacer. Free-standing cross-linked PIL allyl films are obtained by curing the precursor solution with a UV curing conveyor system after 50 scanning passages (Primarc UV Technology, Minicure, Mercury vapor Lamp, UV intensity 100 W·cm–2, duration of each scan 4 s). The acetone is evaporated under vacuum after the synthesis at 50 °C for 1 day. Reference samples without thiol precursors have also been prepared using the same method.

Methods and Techniques

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

1H NMR spectra were recorded at 297 K on a Bruker AVANCE 400 spectrometer at 400 MHz and referenced to the residual solvent peaks [1H, δ 7.26 for CDCl3; 1H, δ 2.05 for (CD3)2CO].

Infrared Spectroscopy

Attenuated total reflection (ATR)-Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed using a Tensor 27 (Bruker) FTIR instrument equipped with an ATR accessory unit.

Extractable Content

Soxhlet experiments were performed with a BUCHI SpeedExtractor E-914. The extractable content was determined by three cycles of extraction in acetone at 70 °C under 100 bar. Each cycle lasts about 15 min.

Rheology

Rheological measurements were performed with an Anton Paar Physica MCR 301 rheometer equipped with a CTD 450 temperature control device and a plate–plate geometry (Gap 250 or 500 μm, diameter 25 mm, plate; polymerization system made from a lower glass plate coupled with an UV lamp 142 mW·cm–2). A 1% deformation was imposed at 1 Hz. Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) were recorded as a function of time. The solution of precursors of materials was put in the rheometer geometry, and measurements begin immediately with UV exposure at 30 °C.

Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) experiments were performed in air on a Q50 model (TA Instruments) applying a heating rate of 10 °C·min–1 to 600 °C.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Glass transitions of the materials were determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Sequences of temperature ramps (heating, cooling jump, heating, cooling, and heating) in the −80 to 180 °C range were performed at 20 °C·min–1 ramping up and 5 °C·min–1 cooling down using a TA Instruments Q1000 equipped with a liquid nitrogen cooling accessory and calibrated using sapphire and high purity indium metal. All samples were prepared in hermetically sealed pans (5–10 mg/sample) and were referenced to an empty pan. The reported Tg values are from the second heating cycle.

Tensile Testing

Traction experiments were performed on a Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer instrument (TA, Q800) in the tensile mode at room temperature on samples with size 0.8 cm × 2 cm. A strain rate of 20%·min–1 to 500% was applied with an initial strain of 0.05% and a preload force of 0.01 N to obtain stress–strain curves.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) experiments were conducted on the Q800 in the tension mode. Heating ramps were performed from −70 to 200 °C at a constant rate of 3 °C·min–1 with a maximum strain amplitude of 0.05% at a fixed frequency of 1 Hz and a preload force of 0.01 N.

Stress Relaxation Measurements

Stress relaxation measurements were carried out on the Q800 at different temperatures. A preload force of 0.01 N and a constant strain of 3% were applied, and the stress decay was monitored over time.

Ionic Conductivity

The ionic conductivity was measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy using a VSP 150 potentiostat (Biologic SA). Samples were first dried under vacuum 70 °C for 1 day before being positioned between two gold electrodes and placed in a thermostated cell under an argon atmosphere. Experiments were carried out in a temperature range from 25 to 100 °C, in the frequency range from 2 MHz to 1 Hz with a rate of 6 points per decade and at 0 V with an oscillation potential of 10 mV. The ionic conductivity (S·cm–1) is calculated using the equation

| 1 |

where Z is the real part of the complex impedance (ohms), d is the thickness of the sample (cm), and S is the sample area (cm2).

The characterizations described above have been performed on 2–4 different batches for each composition. For each batch of each composition, tensile properties have been measured 2–6 times. Ionic conductivity has been measured 1–4 times for every batch of each composition. Stress relaxation has been followed and measured 2–5 times per investigated relaxation temperature, for each batch of each composition. The standard deviation is given as an error bar in the graphs.

Remolding Tests

Compression molding tests were conducted using a SPECAC hydraulic press with 4000 stability temperature controllers at 120 °C and a pressure of 285 kg·cm–2 for 2 h.

Healing Tests

The healing experiments were conducted in two different manners: stacked or interfacial. Sample films were first cut into two pieces. Then, the two pieces of the samples were either stacked together or closely placed in contact at the interface. The samples were protected by Teflon films and pressurized by two glass plates with clips and then were heated at 120 °C for 2 h in the oven.

Calculation of Topology Freezing Temperature Tv and Activation Energy of the Dynamic Exchange Reaction Ea

Based on Maxwell’s model for viscoelastic fluids, the stress relaxation behavior of the vitrimer can be described with eq 2 where the relaxation time τ is determined as the time required to relax to 37% (1/e) of initial stress47

| 2 |

For vitrimers, relaxation times reflect associative exchange reactions, and their temperature dependence can be fitted to the Arrhenius equation (eq 3)24,48

| 3 |

The values of τ were then plotted as a function of temperature to determine the activation energy Ea of the associative exchange reaction. The topology freezing temperature Tv is another key characteristic for vitrimer materials. Conventionally, the hypothetical Tv is chosen as the temperature at which the viscosity equals 1012 Pa·s as this value describes the liquid-to-solid transition of a glass-forming liquid.7,10 The relation between the viscosity η and the characteristic relaxation time τ can be expressed with the Maxwell relation (eq. 4)49

| 4 |

where G stands for the shear modulus, ν for the Poisson ratio, and E′ for the storage modulus at the rubbery plateau. Using the Poisson ratio = 0.5 usually used for rubbers,24,49Tv is determined by combing eqs 3 and 4.

Results and Discussion

Stretchable, highly conducting, and reprocessable ionoelastomers are developed from a commercial rubber turned into a PIL and from the vitrimer dynamic chemistry (Scheme 1a). The liquid-free ionoelastomer is intrinsically conductive, thanks to its ionic liquid-like cations attached to the polymer chains, leaving the anions mobile. The material is also dynamic, thanks to its boronic ester cross-linkers offering the ionoelastomer with both stretchability and vitrimer features. At low temperatures, the topology of the vitrimer network is frozen, behaving then like a permanently cross-linked ionoelastomer. At elevated temperatures, the network can flow by topology rearrangement and behaves like viscoelastic liquids with interesting capabilities such as healability, malleability, and recyclability (Scheme 1c). The PIL is first synthesized from a commercially available and high-molecular-weight rubber, a copolymer of poly(epichlorohydrin) and PEO (Scheme 1b). The allyl functions pending from the synthesized PIL (PIL allyl) will be used subsequently for its cross-linking with dynamic functions and for the introduction of dangling chains as free volume enhancers through thiol–ene click reactions.

Synthesis and Characterization of PIL Allyl

The synthetic route of PIL allyl is adapted from the synthesis protocols of PILs previously described (Scheme 1b).50,51 Two steps were involved in the preparation of PIL allyl: the quaternization of N-allylimidazole with a commercial rubber C2000XL and the subsequent anion–exchange reaction of chloride ions with bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (TFSI) anion. This known and robust synthesis is a simple post-modification of a commercially available polymer to obtain a linear PIL with suitable features such as high ionic conductivity, low Tg, and the possibility to be cross-linked through thiol–ene click reaction and to facilitate any subsequent up-scaling. The successful synthesis of PIL allyl has been confirmed by ATR-FTIR and 1H NMR. ATR-FTIR spectrum of C2000XL, PIL allyl with Cl– and TFSI– counter-anions can be found in Figure S4. The quaternization of the C2000XL is confirmed by the disappearance of the stretching band of the C–Cl halogen bond at 737 cm–1 and a new band of allyl C–H deformation vibration at 995 cm–1. The successful ion exchange to TFSI– counter-anion is proved by the C–F stretching bands at 736 and 1047 cm–1, as well as the C-CF3 stretching band at 1347 cm–1. 1H NMR spectra of PIL allyl in deuterated acetone shows peaks of the imidazolium ring at 9.0 and 7.73 ppm in the spectra confirming the quaternization of C2000XL. The comparison in proton integrations from imidazolium groups and C2000XL backbone highlights the quaternization of epichlorohydrin units (Figure S2).

The thermal properties of PIL allyl were investigated by DSC and TGA (Figure S5a,b). PIL allyl is a gluey polymer with poor free-standing ability at room temperature with a Tg of −19 °C observed by DSC. No crystallization nor melting could be observed, implying the amorphous nature of PIL allyl. Besides that, an onset of mass loss at 314 °C measured by TGA has been assigned to thermal degradation. The ionic conductivity behavior of PIL allyl at different temperatures has been measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (Figure S5c). At 30 °C, PIL allyl demonstrates an ionic conductivity of 2.7 × 10–5 S·cm–1, which is among the highest reported values at room temperature for linear PILs.52,53 This excellent performance is the result of the combination between the highly dissociating ion pair (EMI and TFSI),52,54 the well-known dissociating media from ethylene oxide units, and the flexible nature of the polymer chains, as indicated by the low Tg of the material. By increasing the temperature, the ionic conductivity increases as the ion mobility rises and finally reaches 1.3 × 10–3 S·cm–1 at 80 °C, following a Vogel–Tamman–Fulcher (VTF) dependency (Figure S5d). This indicates that the movement of the charge carriers is correlated with the polymer chain movement with a parameter A found to be 54.7 S·K1/2·cm–1, while the Ea, the activation energy of ionic conduction, is 9.6 kJ·mol–1. Therefore, PIL allyl is a solid ionic conductor with a wide operating temperature range of about −19 to 314° C.

Synthesis of Ionoelastomer Based on PIL

In order to obtain ionoelastomers, the resulting PIL allyl was then cross-linked with different quantities of di-thiol dynamic cross-linkers containing boronic ester functions (Scheme 1a, path i). 2,2′-(1,4-Phenylene)-bis[4-mercaptan-1,3,2-dioxaborolane], named BDB, was used as a cross-linker and synthesized following a protocol reported elsewhere.34 PEG chains terminated with a thiol functional group (PEGSH, average Mn = 800 g·mol–1) were also introduced into the PIL networks as polar dangling chains and as free volume enhancers (Scheme 1a, path ii). Darocur 1173 (2-Hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone) was selected as the free-radical photoinitiator as it has been previously reported to be efficiently used for the addition reaction between thiol and 1-allylimidazole.55 Details of all sample compositions and characterizations are listed in Table 1. The PIL allyl network synthesized by free-radical cross-linking via the allyl pendant groups without the addition of any thiol cross-linker was used as blank (PIL D1). Non-vitrimer PIL allyl permanent networks using 1,4-butanediol Bis(thioglycolate) (DT) as a non-dynamic dithiol cross-linker (PIL-DT) were synthesized for comparison. Illustration of PIL-DT networks (Figure S13) and the complete study of these control samples can be found in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Compositions and Characterizations of all PIL Allyl Cross-Linked Networks with or without PEG Dangling Chains Using 2 wt % of Darocur 1173 as the Photoinitiator.

| sample | BDB (mol %) | PEGSH (mol %) | extractable content (wt %) | Tα (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIL-D1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |

| PIL-BDB5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2.7 |

| PIL-BDB10 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 10.2 |

| PIL-BDB25 | 25 | 0 | 4 | 25.1 |

| PIL-BDB50 | 50 | 0 | 5 | 30.4 |

| PIL-BDB100 | 100 | 0 | 8 | 41.5 |

| PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 | 25 | 25 | 3 | –2.4 |

| PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 | 25 | 50 | 2 | –12.0 |

To study the cross-linking reaction kinetics between allyl and thiol functional groups at 30 °C, the precursor mixtures of a vitrimer sample (PIL-BDB25, i.e., 25 mol % of thiol groups of BDB vs allyl function), its corresponding non-dynamic control sample (PIL-DT25, i.e., 25 mol % of thiol groups of DT vs allyl function) or the blank sample PIL-D1 were poured into the rheometer followed by an in-situ photopolymerization (Figure S6). The gel points, where G′ and G″ curves intersected, were within 10 s for all samples, indicating the fast polymerization kinetics between allyl and thiol functional groups (PIL-BDB25 and PIL-DT25). Both PIL-BDB25 and PIL-DT25 samples reached a G′ plateau of about 250 kPa. On the other hand, the presence of radical reactions between allyl functional groups (PIL-D1) is also observed but to a limited extent. The PIL-D1 sample reached a G′ plateau with 2 orders of magnitude lower at only 1.8 kPa and a G″ plateau of 400 Pa, probably due to the very limited cross-linking between allyl functional groups. Soluble fractions of PIL-BDB networks were determined by extraction in acetone (Table 1, the soluble fractions of PIL-DT networks are reported in Table S5). The extractable content of the blank sample PIL-D1 without any thiol functional group was found to be 9 wt %, indicating the formation of a polymer network through the radical cross-linking reaction of allyl bonds. Indeed, a limited cross-linking between a few allyl functional groups would be sufficient to form an insoluble network from high-molecular-weight PIL. The obtained material was very soft, gluey, and not free-standing. On the other hand, the thiol–ene click reaction between boronic ester cross-linkers and allyl functional groups led to free-standing non-sticky materials with relatively low soluble fractions between 1 to 8 wt %, indicating that the presence of dithiol cross-linker tipped the balance in favor of the dominant thiol–ene click reaction, generating a better cross-linked network. The soluble fractions of PIL-DT networks follow the same trend with values ranging from 3 to 8 wt %.

The introduction of PEGSH into the polymer network through its thiol functional group does not cause any change in the formation of polymer networks. Indeed, extractable contents lower than 5% were obtained when PEGSH was used at 25 or 50 mol % versus allyl function in PIL-BDB25 networks.

Healing Behavior and Thermomechanical Properties of the Ionoelastomers

After verifying the formation of PIL-BDB networks, these materials were first subjected to healing tests to check if the presence of BDB cross-linkers enables vitrimer behaviors and to study the effect of the dynamic cross-linker content (Figure 1a). Sample films were cut into two pieces, then stacked together, and healed at 120 °C for 2 h. We arbitrarily set our healing temperature at 120 °C to prevent dissociative exchange of boronic ester function that might occur in the presence of moisture,9 even if as shown later (Figures 3 and S11), it could have been performed at lower temperature for longer time. For samples containing 5 and 10 mol % of BDB, no healing could be observed as the two sample pieces could be easily separated. Below 10 mol % BDB cross-linker loadings, there is probably not enough dynamic units present to enable the associative exchange mechanism of boronic ester and to provide the materials with efficient healing properties. Indeed, the dynamic functions must be in close vicinity for the exchange to proceed6 (see the exchange reaction in Scheme 1a). On the opposite, the films of PIL-BDB with 25, 50, and 100 mol % loadings of the BDB content completely fused into one piece with homogeneous thickness. After the selected healing process, no trace of the original films could be seen, and the same order of magnitude is recovered for the Young’s modulus and elongation at break of the materials (Figures S8, S9 and Table S1). The same tests were also conducted on PIL-DT non-vitrimer control samples. In sharp contrast, all these samples could be separated easily, and no healing effect was detected, as expected. These observations indicate that dynamic shuffling of the boronic esters is directly responsible for the healing behavior of these materials (Scheme 1c).

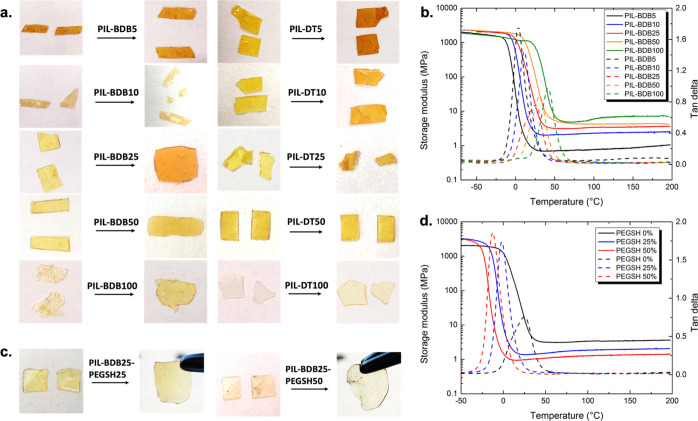

Figure 1.

(a) Healing tests at 120 °C during 2 h of PIL-BDB samples and their control samples PIL-DT by stacking two pieces together; (b) DMA curves of PIL-BDB series samples; (c) healing tests of PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 samples; and (d) DMA curves of PIL-BDB-PEGSH series samples.

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of the stress relaxation curves of PIL-BDB25 with PIL-DT25 samples at 30 and 60 °C; stress relaxation curves of (b) PIL-BDB25, (c) PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25, and (d) PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 at different temperatures; and Arrhenius plots of relaxation times vs temperature of (e) PIL-BDB and (f) PIL-BDB25-PEGSH vitrimer materials.

To better understand the effect of the dynamic cross-linker content on the properties of PIL-BDB networks and on the different healing behaviors observed, PIL-BDB series samples were subjected to DMA experiments between −70 and 200 °C. Figure 1b shows the storage modulus and tan δ versus temperature of cross-linked PIL-BDB networks with different loads of BDB dynamic cross-linker. At low temperatures, the storage modulus of glassy states of all samples is similar (about 2 GPa), whereas the storage modulus decreases remarkably when the samples go through an evident and narrow α relaxation. As expected, the storage modulus on the rubbery plateau increases with increasing BDB content, that is, increasing cross-link density. Besides, the storage modulus (E′) on the rubbery plateau is rather constant when increasing further the temperature, suggesting that the networks maintain their structural integrity at higher temperatures. Generally, Tα is defined as the peak of tan δ versus temperature curve, and all Tα values are shown in Table 1. It is evident that Tα increases with increasing the cross-linking density. Tan δ peak intensity represents the ratio of the viscous (E″) to elastic (E′) responses of a viscoelastic material. It can serve as an indicator for the elasticity of the material, and a lower value implies a higher elasticity, whereas a higher value indicates that the material has more energy dissipation potential. Two trends of tan δ peak value evolution can be observed. By increasing the BDB cross-linker content from 5 to 25 mol %, tan δ peak value decreases, indicating that the elasticity of the samples increases with the cross-link density. On the other hand, tan δ peak value increases from 25 to 100 mol % of the BDB content which seems to indicate an increase in mechanical energy dissipation by the materials. It might be related to the higher availability of boronic ester groups present in the system and therefore an increase in the network rearrangement, resulting in materials with more elevated energy dissipation ability (vide infra). These results obtained from DMA experiments can be related to the observations of healing tests. PIL-BDB series samples can be divided into two groups: (1) PIL-BDB5 and PIL-BDB10 samples and (2) PIL-BDB25, PIL-BDB50 and PIL-BDB100 samples. While the first group of PIL-BDB samples did not possess enough dynamic cross-links and demonstrates a typical viscoelastic response as cross-link density increases, it appears that a minimum of 25 mol % of BDB is necessary to enable the vitrimer properties of the ionoelastomers. Thus, further characterizations were only conducted on PIL-BDB samples with 25, 50, and 100 mol % of the BDB content.

The same characterizations were performed on materials containing dangling chains. A content of 25 or 50 mol % of PEGSH versus allyl groups was used to prepare PIL-BDB25-PEGSH networks, that is, with the minimum content of 25 mol % of BDB enabling the vitrimer properties, as described in Scheme 1a, path ii. PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 samples were first subjected to healing experiments (Figure 1c). For both samples, the two films completely fused into one piece, and no trace of the original films could be seen, proving that the thermally activated healing ability enabled by boronic ester bonds is not compromised with the addition of PEG dangling chains. As PEGSH loading increases, the storage modulus of rubber plateau consistently declines, and the Tα decreases, which can be explained by the introduction of PEGSH pendant chains acting as the internal plasticizer by increasing the free volume and facilitating the motion of polymer chains.

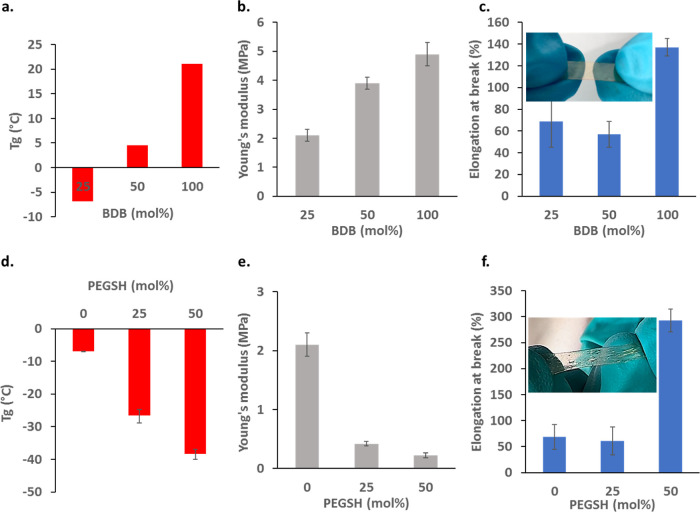

Thermal and mechanical properties of the dynamic ionic materials, that is, the PIL-BDB series (with BDB content above 25 mol % vs allyl) and the PIL-BDB25-PEGSH series (with PEGSH content of 25 to 50 mol % vs allyl) were then investigated. From DSC measurements (thermograms are shown in Figure S7a,b, respectively), it appears that all samples are completely amorphous, with only one glass transition detected. By plotting Tg values of PIL-BDB series samples as a function of the BDB molar ratio (Figure 2a), one can see that the Tg increases from −7.0 °C with 25 mol % of the BDB cross-linker to 21.2 °C with 100 mol %. This tendency is typically observed for a thermoset of which the cross-linking density is increased. On the other hand, when the Tg values of PIL-BDB25-PEGSH samples are plotted as a function of PEGSH molar ratio (Figure 2d), it appears that Tg monotonously decreased from −7 to −38.5 °C with increasing quantities of PEG dangling chains, that is, with increasing free volume. Owing to their low Tg, PIL-BDB-PEGSH25 and PIL-BDB-PEGSH50 are very soft and flexible materials at room temperature. These results illustrate the possibility of tuning the Tg of the materials by adjusting the quantities of cross-linkers and dangling chains.

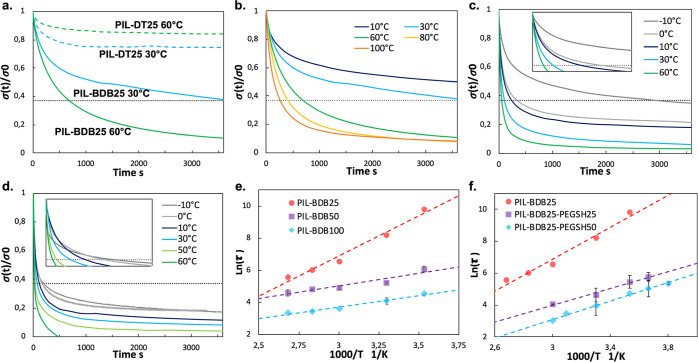

Figure 2.

Evolution of Tg (a,d), Young’s modulus (b,e), and elongation at break (c,f) as a function of BDB for the PIL-BDB and PEGSH content for PIL-BDB25-PEGSH. Insert: photographs of stretched ionoelastomer vitrimers (PIL-BDB25 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25). Stress relaxation behaviors of PIL-based ionoelastomer vitrimers.

Tensile test experiments were then performed to evaluate the stiffness and the stretchability of all samples (Figure S8). Increasing the cross-linker content from 25 to 100 mol % of BDB, and so the cross-linking density, led as expected to an increase in Young’s modulus (Figure 2b) from 2.1 to 4.9 MPa, respectively. Simultaneously, the elongation at break remains insensitive and around 65% for the BDB content below 50 mol % but increases significantly up to 137% when the BDB content is at 100 mol % (Figure 2c, photograph of stretched PIL-BDB25 inserted). A similar tendency about the sharp increase in the elongation at break was reported in the literature for samples with a high content of dynamic exchangeable functions.56 The high concentration of exchangeable groups and the fast boronic ester exchange reaction within PIL-BDB100 sample might allow the polymer network to rearrange and to release the inner stress in time before fracture. Young’s modulus of PIL-BDB-PEGSH samples dropped dramatically compared to PIL-BDB25 from 2.1 to 0.2 MPa (Figure 2e). This effect was expected considering the additional free volume induced by the pendant chain of PEGSH. Moreover, the average strain at break was measured around 65% for PIL-BDB25 and PIL-BDB-PEGSH25. One can hypothesize that the additional free volume generated by 25 mol % PEGSH only is not high enough to affect this property. On the opposite, the introduction of 50 mol % of PEGSH turns the ionoelastomer into a ductile material with a strikingly increased elongation at break up to 293% for PIL-BDB-PEGSH50. The photograph inserted in Figure 2f of stretched PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 sample illustrates the elastic behavior. More pictures of stretched ionoelastomer vitrimers can be found in Figure S10 (see video available in the Supporting Information). All these results demonstrated that the mechanical properties of the ionoelastomer can be easily tuned by both cross-linker and dangling chain content to reach high stretchability.

Owing to exchange reactions of vitrimers at elevated temperatures, vitrimer materials demonstrate macroscopic flow and stress relaxation enabled by reversible rearrangement of the cross-linked network.57 On the contrary, conventional thermosets are resistant to stress relaxation under an applied strain due to their stable cross-linked networks.58 To study the exchange dynamics of boronic ester bonds, PIL-BDB and PIL-BDB-PEGSH samples were subjected to stress relaxation experiments at various temperatures by monitoring the decrease in stress over time at a constant strain of 3%. Same tests were conducted on PIL-DT samples which served as non-dynamic control samples without the boronic ester cross-linkers. Figure 3a compares the stress relaxation curves obtained at 30 and 60 °C of PIL-BDB25 and PIL-DT25. The non-dynamic control sample PIL-DT25 initially releases around 20% of the initial stress before reaching a plateau, as expected from a permanently cross-linked network. On the other side, the PIL-BDB25 sample relax stress continuously, decreasing to 63% of the initial stress after 1 h at 30 °C and 90% after only 1 h at 60 °C. These results provide convincing confirmation that the dynamic boronic ester cross-linkers enable the network rearrangement in PIL-BDB samples as expected from a vitrimer material. Same contrasts are also seen by comparing between PIL-BDB50 and PIL-DT50 in Figure S11a and PIL-BDB100 and PIL-DT100 in Figure S11b.

Stress relaxation curves for increasing temperature are reported in Figure 3b, for PIL BDB25. This ionoelastomer vitrimer presents large stress relaxation whose rate increases with increasing temperature as the relaxation process is essentially controlled by the thermally activated boronic ester exchange reaction.34 Similar tests performed on PIL-BDB50 and PIL-BDB100 are reported in Figure S11c,d, respectively. The same tendency is observed for those samples, and it is worth noting that the rates of relaxation increase with the content of dynamic cross-linker in the material, that is, PIL-BDB100 relaxed of about 63% in 1 min only at 30 °C, for instance. This sample even completely releases stress in less than 40 min at 60 °C when PIL-BDB25 is not fully relaxed after 1 h at higher temperatures. Vitrimer behavior is observed for the PIL-BDB25-PEGSH series containing 25 mol % and 50 mol % of PEG dangling chains, as presented in Figure 3c,d respectively. Comparison between these samples shows that the dangling chains also increase the relaxation rate as it takes 1 h at 30 °C for PIL-BDB25 to relax 63%, whereas it takes only 1.1 min for PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50. The high relaxation rates of PIL-BDB-PEGSH samples could be explained by the presence of dangling chains that facilitate the motion of polymer chains and consequently the exchange reaction between boronic ester groups. At −10 and 0 °C, stress relaxation is also observed since these temperatures are still above the Tg of the materials preventing the quenching of the network topology coupled to the quenching of segmental motions.24

Relaxation time τ of a vitrimer is defined as the time required to relax to 37% (1/e) of initial stress.47 The comparison of relaxation time at different temperatures allows investigating further their relaxation behavior (values in Table S2). The relaxation times of PIL-BDB and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH samples (Figure 3e,f) show an Arrhenius temperature dependence as expected for vitrimer materials, confirming an associative exchange mechanism for the boronic ester exchange reaction. Activation energies Ea (eq 3) of the viscous flow for each system were calculated from the slope of ln(τ) versus the reciprocal temperature and are reported in Table 2. The Ea of PIL-BDB25, PIL-BDB50, and PIL-BDB100 were found to be 41.6, 13.0, and 11.9 kJ·mol–1, respectively. The abundant exchangeable linkages existing in PIL-BDB50 and PIL-BDB100 networks result in very fast exchange kinetics and consequently low activation energies of the viscous flow. These results are similar to the activation energies (7.7–13.8 kJ·mol–1) for styrene-butadiene rubber with the boronic ester cross-linker.34 The Ea are 21.9 and 24.1 kJ·mol–1 for PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50, respectively, which are lower than that of PIL-BDB25 (41.6 kJ·mol–1), probably because of increasing polymer chain mobility with the introduction of PEG dangling chains. The hypothetical topology freezing temperature Tv can be extrapolated from relaxation times based on the method described in the experimental part. When the temperature is below Tv, the exchangeable reaction is slow, the network topology is frozen, and the vitrimer behaves like a normal cross-linked elastomer. Above Tv, exchangeable reactions are enabled, vitrimers progressively behave like viscoelastic liquids with an increase in the temperature and can be reprocessed and recycled. The hypothetical Tv of PIL-BDB25, PIL-BDB50, and PIL-BDB100, as reported in Table 2, is −44, −154, and −169 °C, respectively, confirming that an increase in the BDB content, that is, in exchangeable functions, tends to facilitate the dynamic behavior and to lower the apparent Tv. The hypothetical Tv is lower than Tg. In this case, the vitrimer behaves like a viscoelastic liquid with an Arrhenius-law-compliant viscosity at T > Tg.5 As the temperature drops and approaches Tg, the dynamic exchange reaction remains fast while segmental motions of polymers associated with Tg limit the topology rearrangement of the network. As expected, the hypothetical Tv of PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 dropped with the introduction of PEG chains to −128 and −130 °C, respectively, confirming here the enhancement of the dynamic behavior by the presence of dangling chain and free volume in the ionoelastomers. While these Tv are all below the Tg of the corresponding materials, theoretically enabling the topological rearrangement at any temperature above Tg, it should be noted that after prolonged contact of PIL-BDB samples at room temperature for several months, the two films could still be easily separated without any obvious uncontrolled co-bonding. It indicates that even with a low Tv, significant topological rearrangement of samples containing more than 25 mol % of BDB can be activated only when desired by heating to trigger the healing ability.

Table 2. Relaxation Times Extracted from Stress Relaxation Tests of PIL-BDB and PIL-BDB-PEGSH Samples and Their Corresponding Theoretical Tv and Ea Associated with the Boronic Ester Exchange Reaction.

| sample | Tg (°C) | Tv (°C) | Ea(kJ·mol–1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIL-BDB25 | –7.0 | –44 | 41.6 |

| PIL-BDB50 | 4.6 | –154 | 13.0 |

| PIL-BDB100 | 21.2 | –169 | 11.9 |

| PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 | –26.8 | –128 | 21.9 |

| PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 | –38.5 | –130 | 24.1 |

Ionic Conducting Behavior of the Ionoelastomer Vitrimers

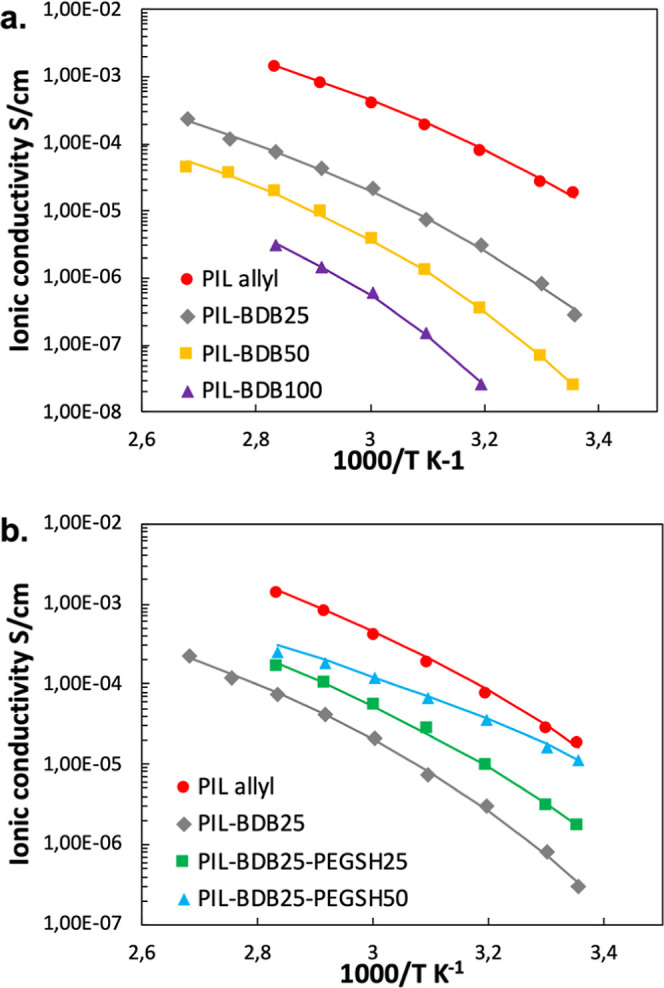

The ionic conductivity behaviors of PIL-based ionoelastomer vitrimers at different temperatures were studied by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (Figure 4). The effect of cross-linking degree was studied by comparing ionically conducting behaviors of pristine PIL allyl linear polymer and PIL-BDB25, PIL-BDB50, and PIL-BDB100 networks (Figure 4a). The values of ionic conductivities at 30 °C and VTF parameters are listed in Table 3. The ionic conductivity dropped dramatically by 2 orders of magnitude after introducing 25 mol % of BDB cross-linker, from 2.7 × 10–5 S·cm–1 of PIL allyl to 8.0 × 10–7 S·cm–1 of the PIL-BDB25 sample at 30 °C. The ionic conductivities further decreased with increasing BDB content (i.e., cross-link density). It should be noted that the ionic conductivity behavior of the PIL-BDB100 sample could not be evaluated below 40 °C due to a too low conductivity at this temperature which is below its α transition (Figure 1b), where the mobility of the polymer chain is restricted and not sufficient to support conduction.

Figure 4.

(a) Ionic conductivity behaviors of PIL-BDB series samples at different temperatures compared with pristine PIL allyl linear polymer and (b) ionic conductivity behaviors of PIL-BDB25-PEGSH series samples with dangling chains at different temperatures compared with PIL allyl polymer and PIL-BDB25 sample. Solid lines: calculation according to the VTF equation.

Table 3. Ionic Conductivity and VTF Parameters (A Factor and Activation Energy of Ion Conduction Ea) of all PIL Allyl, PIL-BDB Series, and PIL-BDB-PEGSH Series Samplesa.

| sample | ionic conductivity at 30 °C(S·cm–1) | A (S·K1/2·cm–1) | Ea(kJ·mol–1) | Tg (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIL allyl | 2.7 × 10–5 | 54.7 | 9.6 | –19.0 |

| PIL-BDB25 | 8.0 × 10–7 | 5,6 | 9,4 | –7.0 |

| PIL-BDB50 | 6.8 × 10–8 | 1.7 | 9.0 | 4.6 |

| PIL-BDB100 | 2.6 × 10–8 at 40 °C | 0.3 | 7.4 | 21.2 |

| PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 | 3.0 × 10–6 | 22.3 | 11.4 | –26.8 |

| PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 | 1.6 × 10–5 | 4.3 | 9.4 | –38.5 |

R2 > 0.99 in all cases.

Adding dangling chains into cross-linked PIL-BDB networks increases the free volume and tunes the media polarity. We hypothesized that it would facilitate the ion mobility and consequently lead to higher ionic conductivity.59−61 To verify this hypothesis, we compared the ionic conductivities of pristine PIL allyl, PIL-BDB25, PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25, and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 samples at various temperatures (Figure 4b). The PIL-BDB25 sample demonstrated an ionic conductivity of 8.0 × 10–7 S·cm–1 at 30 °C. With the addition of 25 mol % of PEG dangling chains, this value increased by four times to 3.0 × 10–6 S·cm–1. The ionic conductivity further escalated to 1.6 × 10–5 S·cm–1 at 30 °C with 50 mol % of PEGSH, which was 20 times higher compared to the PIL-BDB25 sample with the same cross-linking density but in the absence of dangling chains. Notably, PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 demonstrated an ionic conductivity at 30 °C slightly below that of PIL allyl linear polymer, proving that the addition of polar PEG dangling chains could effectively counterbalance the ionic conductivity lost due to cross-linking. To the best of our knowledge, the ionic conductivities reported herein are higher than any other all-solid ion-conducting dynamic PIL networks reported in the literature.30,31,46 It should be highlighted that apolar alkyl chains were also introduced into cross-linked PIL networks in a similar manner in order to increase the free volume. Details of these materials can be found in Table S3. It has been found that despite the Tg decreased after introducing alkyl dangling chains, the ionic conductivities of those PIL-based networks decreased from 10–6 to 10–8 to 10–7 S·cm–1 at 30 °C. It demonstrates that the choice of polar dangling chains such as PEG is critical in the enhancement of ionic mobility. Indeed, the existence of hydrogen bonding between the imidazolium group and PEO has been reported.62,63 This interaction could allow better the dissociation of the 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (EMIM TFSI) ionic pair by hindering the cation and creating a polar medium to promote the ionic movement.

VTF parameters of the synthesized ionoelastomers were extrapolated, with R2 fit values above 0.99, confirming that the movement of ions was correlated to those of polymer chains. For either PIL allyl, PIL-BDB, and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH samples, the activation energies of ionic conduction were around 10 kJ·mol–1, which demonstrates that the modification in the polymer network environment does not affect the capacity of the charge carrier to move within the network and thus their capacity to participate to the ionic conduction. It is also noticed that the A value significantly decreases with increasing BDB, indicating a decrease in charge carrier proportion, as observed elsewhere.64,65 Due to the reduction of the movement of the polymer chain via cross-linking and the decrease in overall polarity, these modifications might build up ion clusters and limit dissociated ion’s quantity. Regarding the effect of PEGSH on the conductivity of the ionoelastomers, the introduction of additional ethylene oxide segments via PEGSH induces several antagonist effects. It promotes the dissociation of ion clusters, decreases the Tg, and thus T0 of the material, but it also dilutes the concentration of charge carriers. In other words, the introduction of 25 mol % PEGSH leads to a huge increase in A factor, thanks to the dissociation potential of the ethylene oxide unit which erases the dilution effect. However, an additional increase in PEGSH further dilutes the charge carrier concentration, thus decreasing A value. Besides, the associated decrease in Tg, inducing larger (T – T0) value, is beneficial for reaching high ionic conductivity as the movement of polymer chain is promoted. Finally, the introduction of polar dangling chains allows bringing the ionic conductivity back to that of the bare PIL allyl, attenuating thus the effect of cross-linking. As a result, the PIL-based ionoelastomers exhibit high ionic conductivity with high stretchability. In addition, these two parameters can be tuned by both cross-linker and dangling chain content.

Recycling Behavior of Ionoelastomer Vitrimers

Based on the results of healing tests and stress relaxation tests, we further envisioned that the dynamic boronic ester cross-links could allow the reprocessing of these materials. To verify this, samples were cut into small chips and then remolded using a hydraulic press under a pressure of 285 kg·cm–2 at 120 °C for 2 h. PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 samples were remolded into new cohesive samples (Figure 5a), and the ionic conductivity behavior of the recycled samples remained similar to pristine samples (Figure 5d). Likewise, results of recycled PIL-BDB samples are summarized in the Supporting Information (Figure S12 and Table S4). DMA tests were carried out on PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 and PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 after recycling and compared with their pristine samples (Figure 5b,c). The storage modulus at the glassy state and the rubbery storage modulus remained similar within the experimental error. The position and height of tan δ peak of both recycled samples nearly overlap with original samples, indicating no significant modification on the network properties, at least at the DMA scale. To go further, these samples were reprocessed up to three times. The ionic conductivities at room temperature and Young’s modulus measured after each recycling cycle remained similar even after three cycles of recycling (Figure 5e,f). All these results indicate that the dynamic exchange reaction of boronic ester bonds allows topology rearrangement of the covalently cross-linked PIL-BDB-PEGSH networks enabling them to be reshaped and recycled.

Figure 5.

(a) Recycling tests of PIL-BDB-PEGSH series samples; (b) comparison of the ionic conductivity behavior of pristine and recycled PIL-BDB-PEGSH samples at different temperatures; (c) DMA curves of the PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 sample after recycling compared with its pristine sample; (d) DMA curves of the PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 sample after recycling compared with its pristine sample; (e) ionic conductivities at room temperature of PIL-BDB-PEGSH samples after each recycling cycle; and (f) Young’s modulus of PIL-BDB-PEGSH samples measured after each recycling cycle.

The washability of the ionoelastomer has been considered for further use in possible applications such as smart electrochemical devices and wearables. Taking advantage of the “dry” nature of the synthesized ionoelastomers, with ions grafted directly on the polymer backbone, is especially promising since these ionic materials do not contain any dispersed salt39,40,66 or ionic liquid42−45 that can be extracted in the presence of a solvent. The washability of PIL-BDB25-PEGSH samples has been evaluated in immersing them in a classical dry-cleaning solvent (C2Cl4) at ambient temperature for 1 h. PIL-BDB25-PEGSH25 demonstrates a very limited swelling ratio of 5.6 wt % and an ionic conductivity of 1.5 × 10–6 S·cm–1 after the dry washing test, which is very similar to its ionic conductivity before immersion (1.7 × 10–6 S·cm–1). PIL-BDB25-PEGSH50 exhibits a swelling ratio of 8.6 wt % and an ionic conductivity of 1.5 × 10–5 S·cm–1 after immersion, which is identical to its pristine value (1.5 × 10–5 S·cm–1). PIL-BDB25-PEGSH ionic conducting membranes are promising materials compatible with the dry-cleaning process as they can maintain their dimensional stabilities and ionic conducting behaviors.

Conclusions

In summary, a PIL bearing allyl functional group was successfully synthesized from commercial rubber using a simple method. It was then cross-linked with dynamic boronic ester cross-linkers BDB through thiol–ene “click” photoaddition, resulting in healable ionoelastomer. Effects of dynamic cross-linkers and additional dangling chain on thermomechanical, ionic conductivities and dynamic behavior of the materials were investigated. It has been found that higher cross-linking density results in higher Tg, higher Young’s modulus, and lower ionic conductivity. On the other hand, increasing the amount of PEG dangling chains leads to a decrease in Tg and of Young’s modulus with an increase in elongation at break and in ionic conductivity. The ionic conductivities followed typical VTF dependence due to the correlation between the charge transport of the ionic species and the segmental mobility of the polymer matrix. These materials exhibit a promising combination of high ionic conductivity reaching 1.6 × 10–5 S·cm–1 at 30 °C and high stretchability reaching 300% elongation. These ionoelastomers based on PIL networks exhibited vitrimer properties such as Arrhenius-type stress relaxation, healing, and recyclability, thanks to the associative exchange reaction between boronic ester bonds. Moreover, the recycled materials could recover their original modulus and ionically conducting behaviors. We demonstrated that all-solid ionoelastomer vitrimers can be fabricated by combining wisely recent achievements in material science (PIL, ionoelastomer, and vitrimer) and adequate polymer chemistry. Their design was driven by the need for such materials in different emerging technologies that require ionoelastomers as liquid-free rubbery electrolytes with high ionic conductivities, stretchability and facile processing, reprocessing, and healing such as supercapacitors, batteries, fuel cells, and ionic coatings for electroactive e-textile.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Il

ionic liquid

- PIL

polymeric ionic liquid

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEO

poly(ethylene oxide)

- DT

1,4-butanediol bis(thioglycolate)

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- BDB

2,2′-(1,4-Phenylene)-bis[4-mercaptan-1,3,2-dioxaborolane]

- PEGSH

poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether thiol

- LiTFSI

lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- IR

infrared spectroscopy

- TGA

thermogravimetric analysis

- DMA

dynamic mechanical analysis

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- VTF

Vogel–Tamman–Fulcher

- Tg

glass-transition temperature

- Tv

topology freezing temperature

- Ea

activation energy

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsapm.2c01635.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no 825232 “WEAFING project.”

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yang C.; Suo Z. Hydrogel Ionotronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 125–142. 10.1038/s41578-018-0018-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J.; Chen B.; Suo Z.; Hayward R. C. Ionoelastomer junctions between polymer networks of fixed anions and cations. Science 80- 2020, 367, 773–776. 10.1126/science.aay8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J.; Paquin L.; Barney C. W.; So S.; Chen B.; Suo Z.; Crosby A. J.; Hayward R. C. Low-Voltage Reversible Electroadhesion of Ionoelastomer Junctions. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2000600. 10.1002/adma.202000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming X.; Zhang C.; Cai J.; Zhu H.; Zhang Q.; Zhu S. Highly Transparent, Stretchable, and Conducting Ionoelastomers Based on Poly(Ionic Liquid)S. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 31102–31110. 10.1021/acsami.1c05833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zee N. J.; Nicolaÿ R. Vitrimers: Permanently Crosslinked Polymers with Dynamic Network Topology. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 104, 101233. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2020.101233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winne J. M.; Leibler L.; Du Prez F. E. Dynamic Covalent Chemistry in Polymer Networks: A Mechanistic Perspective. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 6091–6108. 10.1039/c9py01260e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denissen W.; Winne J. M.; Du Prez F. E. Vitrimers: Permanent Organic Networks with Glass-like Fluidity. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 30–38. 10.1039/c5sc02223a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortman D. J.; Brutman J. P.; De Hoe G. X.; Snyder R. L.; Dichtel W. R.; Hillmyer M. A. Approaches to Sustainable and Continually Recyclable Cross-Linked Polymers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 11145–11159. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wemyss A. M.; Bowen C.; Plesse C.; Vancaeyzeele C.; Nguyen G. T. M.; Vidal F.; Wan C. Dynamic Crosslinked Rubbers for a Green Future: A Material Perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2020, 141, 100561. 10.1016/j.mser.2020.100561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montarnal D.; Capelot M.; Tournilhac F.; Leibler L. Silica-Like Malleable Materials from Permanent Organic Networks. Science 80- 2011, 334, 965–968. 10.1126/science.1212648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. X.; Guan Z. Olefin Metathesis for Effective Polymer Healing via Dynamic Exchange of Strong Carbon-Carbon Double Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14226–14231. 10.1021/ja306287s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. X.; Tournilhac F.; Leibler L.; Guan Z. Making Insoluble Polymer Networks Malleable via Olefin Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8424–8427. 10.1021/ja303356z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciaccia M.; Cacciapaglia R.; Mencarelli P.; Mandolini L.; Di Stefano S. Fast Transimination in Organic Solvents in the Absence of Proton and Metal Catalysts. A Key to Imine Metathesis Catalyzed by Primary Amines under Mild Conditions. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2253–2261. 10.1039/c3sc50277e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taynton P.; Yu K.; Shoemaker R. K.; Jin Y.; Qi H. J.; Zhang W. Heat- or Water-Driven Malleability in a Highly Recyclable Covalent Network Polymer. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 3938–3942. 10.1002/adma.201400317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Zhang P.; Zhang H.; Yan C.; Zheng Z.; Wu B.; Yu Y. A Transparent, Highly Stretchable, Autonomous Self-Healing Poly(Dimethyl Siloxane) Elastomer. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2017, 38, 1700110. 10.1002/marc.201700110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y.; Shan S.; Lin Y.; Zhang A. Network Reconfiguration and Unusual Stress Intensification of a Dynamic Reversible Polyimine Elastomer. Polymer 2020, 186, 122031. 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.122031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rekondo A.; Martin R.; Ruiz de Luzuriaga A.; Cabañero G.; Grande H. J.; Odriozola I. Catalyst-Free Room-Temperature Self-Healing Elastomers Based on Aromatic Disulfide Metathesis. Mater. Horiz. 2014, 1, 237–240. 10.1039/c3mh00061c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang H. P.; Qian H. J.; Lu Z. Y.; Rong M. Z.; Zhang M. Q. Crack healing and reclaiming of vulcanized rubber by triggering the rearrangement of inherent sulfur crosslinked networks. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4315–4325. 10.1039/c5gc00754b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P.; McCarthy T. J. A Surprise from 1954: Siloxane Equilibration Is a Simple, Robust, and Obvious Polymer Self-Healing Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2024–2027. 10.1021/ja2113257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmolke W.; Perner N.; Seiffert S. Dynamically Cross-Linked Polydimethylsiloxane Networks with Ambient-Temperature Self-Healing. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 8781–8788. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b01666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tretbar C. A.; Neal J. A.; Guan Z. Direct Silyl Ether Metathesis for Vitrimers with Exceptional Thermal Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 16595–16599. 10.1021/jacs.9b08876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelot M.; Unterlass M. M.; Tournilhac L.; Leibler L. Catalytic Control of the Vitrimer Glass Transition. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 789–792. 10.1021/mz300239f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altuna F. I.; Pettarin V.; Williams R. J. J. Self-Healable Polymer Networks Based on the Cross-Linking of Epoxidised Soybean Oil by an Aqueous Citric Acid Solution. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 3360–3366. 10.1039/C3GC41384E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denissen W.; Rivero G.; Nicolaÿ R.; Leibler L.; Winne J. M.; Du Prez F. E. Vinylogous Urethane Vitrimers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 2451–2457. 10.1002/adfm.201404553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denissen W.; Droesbeke M.; Nicolaÿ R.; Leibler L.; Winne J. M.; Du Prez F. E. Chemical Control of the Viscoelastic Properties of Vinylogous Urethane Vitrimers. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14857. 10.1038/ncomms14857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerre M.; Taplan C.; Nicolaÿ R.; Winne J. M.; Du Prez F. E. Fluorinated Vitrimer Elastomers with a Dual Temperature Response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13272–13284. 10.1021/jacs.8b07094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder R. L.; Fortman D. J.; De Hoe G. X.; Hillmyer M. A.; Dichtel W. R. Reprocessable Acid-Degradable Polycarbonate Vitrimers. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 389–397. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Feng Z.; Liang Z.; Lv Y.; Xiang F.; Xiong C.; Duan C.; Dai L.; Ni Y. Vitrimer-Cellulose Paper Composites: A New Class of Strong, Smart, Green, and Sustainable Materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 36090–36099. 10.1021/acsami.9b11991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortman D. J.; Brutman J. P.; Cramer C. J.; Hillmyer M. A.; Dichtel W. R. Mechanically Activated, Catalyst-Free Polyhydroxyurethane Vitrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 14019–14022. 10.1021/jacs.5b08084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obadia M. M.; Mudraboyina B. P.; Serghei A.; Montarnal D.; Drockenmuller E. Reprocessing and Recycling of Highly Cross-Linked Ion-Conducting Networks through Transalkylation Exchanges of C-N Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6078–6083. 10.1021/jacs.5b02653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obadia M. M.; Jourdain A.; Cassagnau P.; Montarnal D.; Drockenmuller E.; Lyon C. P. E. Tuning the Viscosity Profile of Ionic Vitrimers Incorporating 1,2,3-Triazolium Cross-Links. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1703258. 10.1002/adfm.201703258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks B.; Waelkens J.; Winne J. M.; Du Prez F. E. Poly(Thioether) Vitrimers via Transalkylation of Trialkylsulfonium Salts. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 930–934. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.7b00494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash J. J.; Kubo T.; Bapat A. P.; Sumerlin B. S. Room-Temperature Self-Healing Polymers Based on Dynamic-Covalent Boronic Esters. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2098–2106. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Tang Z.; Zhang X.; Liu Y.; Wu S.; Guo B. Covalently Cross-Linked Elastomers with Self-Healing and Malleable Abilities Enabled by Boronic Ester Bonds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 24224–24231. 10.1021/acsami.8b09863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röttger M.; Domenech T.; van der Weegen R.; Breuillac A.; Nicolaÿ R.; Leibler L. High-Performance Vitrimers from Commodity Thermoplastics through Dioxaborolane Metathesis. Science 80- 2017, 356, 62–65. 10.1126/science.aah5281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue L.; Guo H.; Kennedy A.; Patel A.; Gong X.; Ju T.; Gray T.; Manas-Zloczower I. Vitrimerization: Converting Thermoset Polymers into Vitrimers. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 836–842. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffy F.; Nicolaÿ R. Transformation of Polyethylene into a Vitrimer by Nitroxide Radical Coupling of a Bis-Dioxaborolane. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 3107–3115. 10.1039/c9py00253g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taplan C.; Guerre M.; Winne J. M.; Du Prez F. E. Fast Processing of Highly Crosslinked, Low-Viscosity Vitrimers. Mater. Horizons 2020, 7, 104–110. 10.1039/c9mh01062a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jing B. B.; Evans C. M. Catalyst-Free Dynamic Networks for Recyclable, Self-Healing Solid Polymer Electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18932–18937. 10.1021/jacs.9b09811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato R.; Mirmira P.; Sookezian A.; Grocke G. L.; Patel S. N.; Rowan S. J. Ion-Conducting Dynamic Solid Polymer Electrolyte Adhesives. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 500–506. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo Y. H.; Li S.; Zuo C.; Zhang Y.; Gan H.; Li S.; Yu L.; He D.; Xie X.; Xue Z. Self-Healing Solid Polymer Electrolyte Facilitated by a Dynamic Cross-Linked Polymer Matrix for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1024–1032. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Nguyen G. T. M.; Vancaeyzeele C.; Vidal F.; Plesse C. Photopolymerizable Ionogel with Healable Properties Based on Dioxaborolane Vitrimer Chemistry. Gels 2022, 8, 381. 10.3390/gels8060381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Song H.; Wang Z.; Zhang J.; Zhang J.; Ba X. Stretchable, Self-Healable, and Reprocessable Chemical Cross-Linked Ionogels Electrolytes Based on Gelatin for Flexible Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 3991–4004. 10.1007/s10853-019-04271-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Wang H.; Du X.; Cheng X.; Du Z.; Wang H. Self-Healing, Anti-Freezing and Highly Stretchable Polyurethane Ionogel as Ionic Skin for Wireless Strain Sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 130724. 10.1016/j.cej.2021.130724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.; Yang J.; Yang H.; Miao R.; Wen R.; Liu K.; Peng J.; Fang Y. Boronic Ester-Based Dynamic Covalent Ionic Liquid Gels for Self-Healable, Recyclable and Malleable Optical Devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 12493–12497. 10.1039/c8tc03639j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G.; Granado L.; Coquil G.; Lárez-Sosa A.; Louvain N.; Améduri B. Perfluoropolyether (PFPE)-Based Vitrimers with Ionic Conductivity. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 2148–2155. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright T.; Tomkovic T.; Hatzikiriakos S. G.; Wolf M. O. Photoactivated Healable Vitrimeric Copolymers. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 36–42. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Zhang S.; Zhang X.; Gao L.; Wei Y.; Ji Y. Detecting Topology Freezing Transition Temperature of Vitrimers by AIE Luminogens. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–8. 10.1038/s41467-019-11144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C.; Shi S.; Wang D.; Helms B. A.; Russell T. P. Poly(Oxime-Ester) Vitrimers with Catalyst-Free Bond Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13753–13757. 10.1021/jacs.9b06668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponkratov D. O.; Lozinskaya E. I.; Vlasov P. S.; Aubert P. H.; Plesse C.; Vidal F.; Vygodskii Y. S.; Shaplov A. S. Synthesis of Novel Families of Conductive Cationic Poly(Ionic Liquid)s and Their Application in All-Polymer Flexible Pseudo-Supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 281, 777–788. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.05.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plesse C.; Nguyen G. T. M.; Braz Ribeiro F.; Morozova S. M.; Drockenmuller E.; Shaplov A. S.; Vidal F.. All-Solid State Ionic Actuators Based on Polymeric Ionic Liquids and Electronic Conducting Polymers. In Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD) XX; Bar-Cohen Y., Ed.; SPIE, 2018; p 51. 105941H 10.1117/12.2300774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W.; Texter J.; Yan F. Frontiers in Poly(Ionic Liquid)s: Syntheses and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1124–1159. 10.1039/c6cs00620e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaplov A. S.; Ponkratov D. O.; Vygodskii Y. S. Poly(Ionic Liquid)s: Synthesis, Properties, and Application. Polym. Sci. B 2016, 58, 73–142. 10.1134/S156009041602007X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhôte P.; Dias A.-P.; Papageorgiou N.; Kalyanasundaram K.; Grätzel M. Hydrophobic, Highly Conductive Ambient-Temperature Molten Salts. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 1168–1178. 10.1021/ic951325x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urucu O. A.; Aracier E. D.; Çakmakçi E. Allylimidazole Containing OSTE Based Photocured Materials for Selective and Efficient Removal of Gold from Aqueous Media. Microchem. J. 2019, 146, 997–1003. 10.1016/j.microc.2019.02.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Xue L. L.; Zhou X. Z.; Cui J. X. ″Solid-Liquid″ Vitrimers Based on Dynamic Boronic Ester Networks. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 39, 1292–1298. 10.1007/s10118-021-2592-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Zhou L.; Wu Y.; Zhao X.; Zhang Y. Rapid Stress Relaxation and Moderate Temperature of Malleability Enabled by the Synergy of Disulfide Metathesis and Carboxylate Transesterification in Epoxy Vitrimers. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 255–260. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.; Liu T.; Hao C.; Zhang S.; Guo B.; Zhang J. A Catalyst-Free Epoxy Vitrimer System Based on Multifunctional Hyperbranched Polymer. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 6789–6799. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto A.; Agehara K.; Furuya N.; Watanabe T.; Watanabe M. High Ionic Conductivity of Polyether-Based Network Polymer Electrolytes with Hyperbranched Side Chains. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 1541–1548. 10.1021/ma981436q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.; Kim H. J.; Kim E.; Oh B.; Cho J. H. Photocured PEO-Based Solid Polymer Electrolyte and Its Application to Lithium-Polymer Batteries. J. Power Sources 2001, 92, 255–259. 10.1016/S0378-7753(00)00546-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal F.; Popp J. F.; Plesse C.; Chevrot C.; Teyssié D. Feasibility of Conducting Semi-Interpenetrating Networks Based on a Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Network and Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene) in Actuator Design. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 3569–3577. 10.1002/app.13055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.; Lv Y.; Liu J.; Yan Z. C.; Zhang B.; Zhang J.; He J.; Liu C. Y. Crystallization and Rheology of Poly(Ethylene Oxide) in Imidazolium Ionic Liquids. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6106–6115. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrdad A.; Niknam Z. Investigation on the Interactions of Poly(Ethylene Oxide) and Ionic Liquid 1-Butyl-3-Methyl-Imidazolium Bromide by Viscosity and Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2016, 61, 1700–1709. 10.1021/acs.jced.5b00428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen G. T. M.; Michan A. L.; Fannir A.; Viallon M.; Vancaeyzeele C.; Michal C. A.; Vidal F. Self-Standing Single Lithium Ion Conductor Polymer Network with Pendant Trifluoromethanesulfonylimide Groups: Li+ Diffusion Coefficients from PFGSTE NMR. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 4108–4117. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Fu J.; Lu Q.; Shi L.; Li M.; Dong L.; Xu Y.; Jia R. Cross-Linked Polymeric Ionic Liquids Ion Gel Electrolytes by in Situ Radical Polymerization. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122245. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Guo W.; Guo Z. H.; Ma Y.; Gao L.; Cong Z.; Zhao X. J.; Qiao L.; Pu X.; Wang Z. L. Dynamically Crosslinked Dry Ion-Conducting Elastomers for Soft Iontronics. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2101396. 10.1002/adma.202101396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.