Abstract

We describe the case of a 42-year-old man with cirrhosis who presented with fever and imaging concerning for metastatic disease from suspected renal cell carcinoma. He had a right renal mass with multiple pulmonary masses and underwent a lung biopsy and oncology consultation. Blood cultures revealed Klebsiella pneumoniae, and all the lesions disappeared after intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Our case attempts to increase awareness of this unique presentation of invasive Klebsiella infections and discusses host factors that can predispose to this condition.

Keywords: septic pulmonary emboli, bacterial pyomyositis, sepsis in liver cirrhosis, metastatic infection, klebsiella pneumoniae (kp)

Introduction

Infection and ascites are one of the most common causes of hospitalization in cirrhotic patients. Immune dysfunction, gut dysbiosis, and increased bacterial translocation that occurs in cirrhosis can predispose these patients to invasive infections with increased mortality [1]. Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae from the intestinal origin are frequently isolated as a source of infection in cirrhotic patients, while gram-positive bacteria are a frequent cause of infection in hospitalized patients [1]. We describe a rare case of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in a patient with cirrhosis that at the time of presentation was concerning for diffusely metastatic disease with suspected primary renal cell carcinoma.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old male with a history of decompensated alcohol-related cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital with acute onset of fever, jaundice, and poor oral intake for two weeks. He also reported diarrhea for five days. His past medical history included hypertension and anxiety. He reported drinking two bottles of wine daily. Physical examination showed that he was alert and oriented, with a temperature of 99.1 °F, heart rate of 100 beats per minute, and blood pressure of 152/90 mmHg. He had tenderness over the right costovertebral angle, with a soft, nontender abdomen. There was no flank dullness to suggest ascites. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Initial laboratory results obtained on admission.

mEq/L, milliequivalents per liter; mg/dL, milligrams per deciliter; U/L, units per liter; mmol/L, millimoles per liter; μL, microliter; fL, femtoliter; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; INR, international normalized ratio; WBC, white blood cell

| Laboratory test | Result | Reference ranges |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 110 | 135-148 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.5 | 3.5-5 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 88 | 98-112 |

| CO2 (mEq/L) | 22 | 24-31 |

| Anion gap (mEq/L) | 9 | 7-15 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 19 | 6-20 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.91 | 0.7-1.2 |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | >=90 | >=90 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 134 | 65-99 |

| Protein (g/dL) | 6.1 | 6.3-8.3 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.8 | 3.5-5 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 148 | 40-129 |

| ALT (U/L) | 46 | 5-50 |

| AST (U/L) | 76 | 10-50 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 8 | 0.0-1.2 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 2.9 | 0.5-2.2 |

| WBC count (μL-1) | 26,190 | 4,500-11,000 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.3 | 14-18 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 28.60 | 41-51 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 93.2 | 82-100 |

| Platelet count (μL-1) | 63,000 | 150,000-400,000 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 28.8 | 11.5-14.5 |

| INR | 2.7 |

Urinalysis showed pyuria with nitrites and hematuria as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Urinalysis.

RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell; HPF, high-power field

| Urinalysis | Result | Reference range |

| Color | Amber | - |

| Appearance | Cloudy | - |

| Glucose (urinalysis) | Negative | Negative |

| Bilirubin (urinalysis) | Negative | Negative |

| Ketones (urinalysis) | Trace | Negative |

| Specific gravity | 1.013 | 1.001-1.035 |

| Blood (urinalysis) | Moderate | Negative |

| pH | 5 | 5-8.5 |

| Protein | Negative | Negative |

| Urobilinogen | 4 | <2 |

| Nitrite | Positive | Negative |

| Leukocyte esterase | Moderate | Negative |

| RBC (urinalysis) | 8/HPF | 0-1/HPF |

| WBC | 71/HPF | 0-5/HPF |

| Bacteria | Many | Few |

| Yeast | None seen | |

| Yeast with pseudohyphae | None seen |

Viral hepatitis serologies were negative. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Na (MELD-Na) score was 31. Two sets of blood cultures grew K. pneumoniae in both aerobic and anaerobic bottles. Urine culture grew more than 100,000 colony-forming units of K. pneumoniae. The susceptibility of the organism isolated from blood and urine cultures is described in Table 3.

Table 3. Antibiotic susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration

| Antibiotic name | Klebsiella pneumoniae MIC | Susceptibility |

| Amikacin | <=8 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanate | <=4/2 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Ampicillin | >16 mcg/mL | Resistant |

| Ampicillin/Sulbactam | 8/4 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Aztreonam | <=2 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Cefazolin | <=1 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Cefepime | <=1 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Cefoxitin | <=4 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Ceftaroline | <=0.25 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Ceftazidime | <=2 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Ceftriaxone | <=1 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Cefuroxime sodium | <=4 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Ciprofloxacin | <=0.25 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Ertapenem | <=0.25 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Gentamicin | <=2 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Levofloxacin | <=0.5 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Meropenem | <=0.5 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 4/4 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Tetracycline | <=2 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Tigecycline | <=1 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Tobramycin | <=2 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | <=0.5/9.5 mcg/mL | Susceptible |

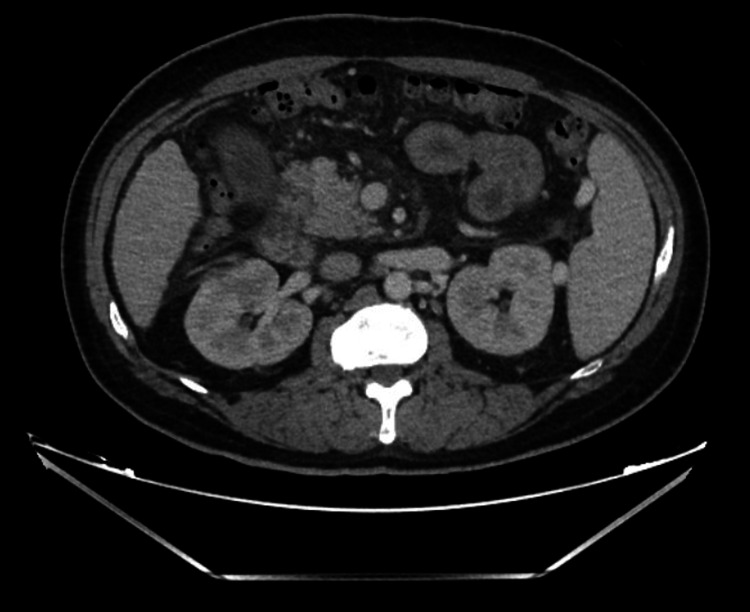

CT of the abdomen and pelvis was interpreted by radiology as a 4 cm heterogeneous enhancing right renal mass, suspicious for renal cell carcinoma, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. CT abdomen and pelvis showing a 4 cm heterogeneously enhancing right renal mass suspicious for renal cell carcinoma.

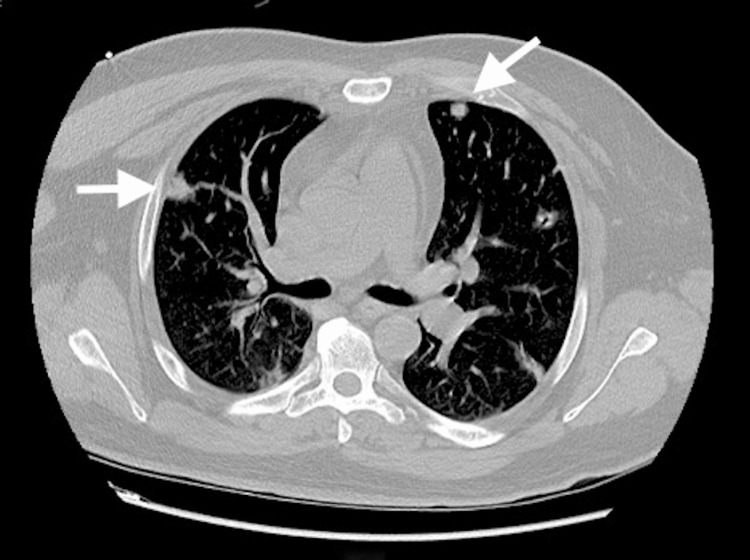

Consequently, a CT chest was obtained, which demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules bilaterally up to 1.5 cm and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. CT chest showing multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules highly suspicious for metastatic disease, measuring up to 1.5 cm in the right upper lobe.

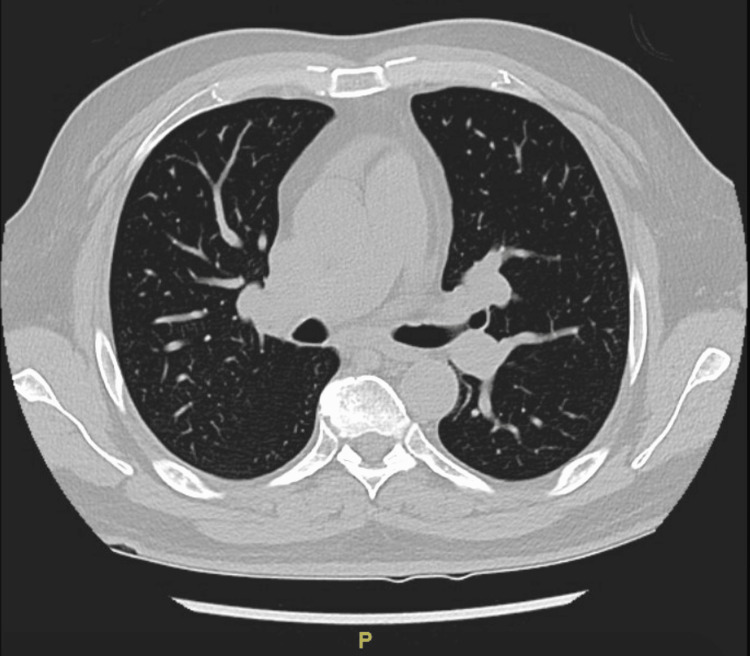

Given the radiological appearance of these masses, there was a strong suspicion that these were metastatic masses from a primary renal malignancy. Tumor markers were ordered, and oncologists were consulted. A renal biopsy was planned for histopathological diagnosis; however, after weighing the risks of post-procedural bleeding between a renal and lung biopsy, a CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy of a right upper lobe pulmonary nodule was pursued and showed necroinflammation suggestive of an abscess. Before the biopsy, the coagulopathy was addressed with a transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and intravenous vitamin K after which the international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.6 on the day the biopsy was conducted. Cytology was negative for malignancy. The patient received two weeks of IV ceftriaxone 2 g every 24 hours, and repeat imaging of the abdomen showed a reduction in the size of the renal mass to 2.5 cm with features now consistent with perinephric abscess. The radiologic features seen on CT this time included an ill-defined parenchymal abnormality in the anterior right kidney, which was overall improving and consistent with evolving pyelonephritis with a stable 2.5 cm overlying perinephric abscess. Drainage was not pursued at this time as its size was less than 3 cm, and it was responding to antibiotics. Similarly, the pulmonary nodules had reduced in size and number in response to the antibiotics, thus revealing their infectious nature. While on IV ceftriaxone for two weeks, the patient then developed septic arthritis of the right sternoclavicular joint with pyomyositis of the right pectoralis muscles. Drainage of the muscle abscess also grew the same isolate of Klebsiella as identified in the blood and urine cultures. An echocardiogram to evaluate for infective endocarditis was negative. Repeat blood cultures done 3 and 14 days after the initial blood culture were negative. He received IV ceftriaxone for eight weeks. A follow-up CT scan of the chest and abdomen three months after discharge (Figures 3, 4) showed complete resolution of the renal abscess, myositis, and pulmonary nodules with residual scarring in the lungs.

Figure 3. Resolution of the pulmonary ground glass opacities after IV antibiotics.

IV, intravenous

Figure 4. Resolution of renal abscess after IV antibiotics.

IV, intravenous

Discussion

This case study attempts to increase awareness of an invasive Klebsiella infection that can lead to multiple septic metastases, which can be mistaken for malignancy before invasive testing, as mentioned above. Most community-acquired Klebsiella infections are associated with pneumonia or urinary tract infections. In the past few decades, an invasive syndrome called K. pneumoniae invasive syndrome, which causes primary liver abscesses followed by metastatic abscesses, has been reported. Our case is a rare presentation, where our patient had widespread dissemination without the presence of any hepatic abscesses [2]. This is a well-known entity in South-East Asia, but more recently, it has also been reported in other continents [3]. Specific hypervirulent capsular strains (K1 and K2) and diabetes mellitus predispose the host to an invasive infection [4-6]. We do not know the capsular serotype of this infection in our patient as typing was not available at our institution. This patient’s risk factors for invasive infection included heavy alcohol use, protein-calorie malnutrition, and cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction [7]. Cirrhosis of the liver is associated with immune dysfunction due to damage to the reticuloendothelial system, deficient bactericidal and opsonization capabilities related to low levels of C3 complement protein, and impairment in chemotaxis mechanisms [7,8].

In patients with cirrhosis, these infections are associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, urinary tract infections, and community-acquired pneumonia [6]. The incidence of Klebsiella infections in patients with cirrhosis is variable. In a prospective study of 159 cirrhotic patients in India, 23% of infections were secondary to K. pneumoniae [9]. Another study in Spain reported an incidence of K. pneumoniae infections in patients with cirrhosis as 1.9% [10]. This patient developed septic arthritis and pyomyositis despite two weeks of antibiotics, which further underscores the increased risk of invasive infections in cirrhotic patients. Hypoproteinemia, ascites, third space expansion, and impaired renal function have been postulated to cause unpredictable drug exposure, response, and altered pharmacokinetics of antimicrobials [11].

In our patient, the imaging-based presumption of neoplasia could have led to incorrect and unnecessary investigations, thus highlighting the importance of increasing awareness of septic metaplasia secondary to certain Klebsiella infections. In a systematic review of 168 patients with septic pulmonary emboli, 8% of these cases were secondary to Klebsiella [12]. Septic pulmonary emboli with metastatic infection to other vital organs pose a poor prognosis [2]. Joint involvement is quite rare as evidenced by the few cases reported in the literature [13]. Of these cases, diabetes, heavy alcohol use, and cirrhosis or IV drug use have been the major risk factors for hematogenous spread to bone or joint, as seen in this patient [13].

We weighed the risks versus benefits of doing a lung biopsy compared to a renal biopsy and proceeded with a lung biopsy after correcting his coagulopathy due to the lower risk of post-procedural bleeding [14,15].

Community-acquired Klebsiella isolates remain susceptible to cephalosporins. The treatment regimen involves third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins and varies from two to four weeks for a solitary abscess and at least six weeks for multiple abscesses [16].

Conclusions

Our case study demonstrates metastatic Klebsiella infection with multiple pulmonary septic emboli, a pyogenic renal abscess, and muscle involvement that was initially suspicious for a metastatic malignancy due to the radiographic appearance of the right renal mass and the presence of multiple lung lesions. Widespread dissemination of Klebsiella with abscesses is possible while sparing the liver. Early recognition and prompt treatment are important as this infection is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: a position statement based on the EASL Special Conference 2013. Jalan R, Fernandez J, Wiest R, et al. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1310–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced multiple invasive abscesses: a case report and literature review. Wang B, Zhang P, Li Y, Wang Y. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:0. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ, et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:160–166. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Septic pulmonary embolism caused by a Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: clinical characteristics, imaging findings, and clinical courses. Chou DW, Wu SL, Chung KM, Han SC. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2015;70:400–407. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2015(06)03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clones causing bacteraemia in adults in a teaching hospital in Barcelona, Spain (2007-2013) Cubero M, Grau I, Tubau F, Pallarés R, Dominguez MA, Liñares J, Ardanuy C. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diagnosis and management of bacterial infections in decompensated cirrhosis. Pleguezuelo M, Benitez JM, Jurado J, Montero JL, De la Mata M. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:16–25. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25135860/ J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acquired C3 deficiency in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis predisposes to infection and increased mortality. Homann C, Varming K, Høgåsen K, Mollnes TE, Graudal N, Thomsen AC, Garred P. Gut. 1997;40:544–549. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Infection in cirrhosis: A prospective study. Bhattacharya C, Das-Mondal M, Gupta D, Sarkar AK, Kar-Purkayastha S, Konar A. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Fernández J, Navasa M, Gómez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Hepatology. 2002;35:140–148. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloodstream infections in patients with liver cirrhosis. Bartoletti M, Giannella M, Lewis RE, Viale P. Virulence. 2016;7:309–319. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1141162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical characteristics of septic pulmonary embolism in adults: a systematic review. Ye R, Zhao L, Wang C, Wu X, Yan H. Respir Med. 2014;108:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klebsiella pneumoniae septic arthritis in a cirrhotic patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Park CH, Joo YE, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim SJ. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:608–610. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.4.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Major bleeding and risk of death after percutaneous native kidney biopsies: a French nationwide cohort study. Halimi JM, Gatault P, Longuet H, et al. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:1587–1594. doi: 10.2215/CJN.14721219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Incidence of bleeding after 15,181 percutaneous biopsies and the role of aspirin. Atwell TD, Smith RL, Hesley GK, et al. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:784–789. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Jun JB. Infect Chemother. 2018;50:210–218. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]