Abstract

Background and Objective

Determination of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1/2 mutational status is crucial for a glioma diagnosis. It is common for IDH mutational status to be determined via a two-step algorithm that utilizes immunohistochemistry studies for IDH1 R132H, the most frequent variant, followed by next-generation sequencing studies for immunohistochemistry-negative or immunohistochemistry-equivocal cases. The objective of this study was to evaluate adding a rapid real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay to the testing algorithm.

Methods

We validated a modified, commercial, qualitative, RT-PCR assay with the ability to detect 14 variants in IDH1/2 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded glioma tumor specimens. The assay was validated using 51 tumor formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. During clinical implementation of this assay, 48 brain tumor specimens were assessed for IDH result concordance and turnaround time to result.

Results

Concordance between the RT-PCR and sequencing and IHC studies was 100%. This RT-PCR assay also showed concordant results with IHC for IDH1 R132H for 11 of the 12 (92%) tumor specimens with IDH mutations. The RT-PCR assay yielded faster results (average 2.6 days turnaround time) in comparison to sequencing studies (17.9 days), with complete concordance.

Conclusions

In summary, we report that this RT-PCR assay can reliably be performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens and has a faster turnaround time than sequencing assays and can be clinically implemented for determination of IDH mutation status for patients with glioma.

Key Points

| Rapid qualitative real-time polymerase chain reaction is a reliable method for detection of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from gliomas. |

| The identification of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in gliomas by qualitative real-time polymerase chain reaction improves the clinical turnaround time signifying its clinical utility. |

Introduction

Gliomas are the most common primary malignant brain tumors in the USA with an annual incidence of 6 in 100,000 [1]. The incidence of gliomas has been shown to vary by age, sex, and race or ethnicity, with the highest prevalence in the USA being among non-Hispanic whites [1]. On a global scale, the incidence is also variable, with the highest rates observed in the USA, Canada, Australia, and Northern Europe [2]. Profiling histologic characteristics assigns gliomas into World Health Organization classifications that range from grade 1 to 4 [3]. While grade 1 gliomas are potentially curable with timely resection, gliomas that range from grades 2–4 are invasive and have a worse prognosis [4, 5]. Accurate classification of these tumors is critical for appropriate treatment [3–6].

Over the years, molecular profiling of these tumors has led to the identification of several molecular features that give insight into prognosis, with some being targets of therapeutic interventions [6, 7]. Patients with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-mutant gliomas show favorable prognoses compared with patients with IDH-wild-type glioblastoma [8–10]. Thus, the determination of IDH mutational status in patients with glioma is central to the diagnostic work-up.

IDH1 and IDH2 are metabolic enzymes involved in cellular aerobic respiration. IDH1, which is located on chromosome 2q33, and IDH2, which is located on 15q26.1, encode the IDH1 and IDH2 enzymes, respectively, which catalyze the oxidative carboxylation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate [4, 11]. Disease-associated variants in the enzymatic active sites of IDH1 and IDH2 lead to the production of the oncometabolite 2-hydroxygluterate [8, 11]. To date, 2-hydroxygluterate has been hypothesized to trigger oncogenesis through an epigenetic mechanism, which involves global alteration of the methylation pattern of DNA and histone proteins [12, 13]. IDH-mutant gliomas exhibit genome-wide DNA hypermethylation and these epigenetic changes make glioma cells more susceptible to additional oncogenic events [8, 14]. In addition to gliomas, IDH mutations have also been observed in several types of cancers, including acute myeloid leukemia, enchondroma, chondrosarcoma, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and all display a similar mechanism of tumorigenesis [8, 15].

Over the last 15 years, studies have found that approximately 80–90% of adult grade 2/3 gliomas and grade 4 astrocytomas that progressed from lower grade gliomas harbor mutations at either p.R132 of IDH1 or p.R172 of IDH2 [16–20]. In fact, an IDH mutation is required to give a diagnosis of oligodendroglioma. The most observed IDH mutation in gliomas is IDH1 p.R132H, with the p.R132H variant accounting for approximately 90% of all IDH mutations in supratentorial astrocytomas and more than 90% of IDH mutations in oligodendrogliomas [3, 8]. Other IDH1 mutations are rare and include IDH1 p.R132C (found in 3.6–4.6% of cases), p.R132G (in 0.6–3.8%), p.R132S (in 0.8–2.5%), and p.R132L (in 0.5–4.4%) [3]. In addition to mutations in IDH1, mutations in a homologous gene IDH2, which are much less common than IDH1 mutations, have also been identified in gliomas [3, 4]. IDH2 mutant protein in gliomas show changes at residue p.R172, with the p.R172K mutation being the most frequent [3, 4].

IDH1/2 mutations play a crucial role in tumor classification owing to their significance in predicting longer overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with gliomas [3, 10, 21–27]. It has been proposed that impaired NADPH production in gliomas with IDH1 mutations may sensitize the tumors to radiation and chemotherapy, providing an explanation for why patients with IDH-mutant neoplasms live longer [22, 23]. It has also been shown that along with MGMT promoter methylation, IDH mutations can promote treatment-induced apoptosis by inhibiting cellular protection against oxidative stress during treatment with chemotherapeutic agents such as temozolomide [9, 28]. Current clinical trials with selective and pan-mutant IDH1/2 inhibitors have shown that this class of drugs may be used in novel therapeutic intervention strategies for patients with IDH-mutant malignancies, including ivosidenib in patients with IDH-mutant gliomas [29, 30].

Although immunohistochemistry (IHC) for IDH1 R132H will identify a vast majority of IDH mutations, sequencing studies are employed to investigate alternate variants in IDH1 and IDH2 [31–33]. However, sequencing studies can often take several weeks for the results to be generated and analyzed, which may delay treatment.

In this study, we validated qualitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect variants in IDH1/2 as an alternative assay to massively parallel sequencing (MPS) technology. The RT-PCR assay for IDH1/2 mutations described in this article utilizes formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples and has a faster turnaround time (TAT) for IDH mutation status than sequencing studies, leading to increased efficiency in the molecular diagnostic work-up for these tumors. High-impact case use includes high-grade gliomas in patients aged younger than 55 years, who have a greater probability of having IDH mutations, as well as the wide variety of newly characterized gliomas without IDH mutations but with other specific entity-defining genetic abnormalities, as described in the most recent edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Central Nervous System Tumours [3].

Materials and Methods

Validation and Residual Clinical Specimens

Fifty-one previously characterized FFPE specimens were used for validation. Samples spanned a range of tumor percentages that are binned < 10%, 10–25% (n = 4), 26–50% (n = 3), and >50% (n = 44) at our institution. Samples with and without a disease-associated IDH variant were selected based on results from in-house multigene solid tumor DNA panels. Horizon DNA reference standards (IDH1 R132H and IDH2 R172K) were obtained as genomic DNA (Horizon Discovery Ltd., Waterbeach, UK).

DNA Extraction

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor specimens were accepted as either rolls or slides for macro-dissection. Tumor percentage was semi-quantitatively assessed by a neuropathologist and ranged from 10 to > 50%. DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DSP DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from 5 to 15 slides with 5-μm thick sections or up to three tubes containing three 10-μm thick rolls. Briefly, tissue was deparaffinized and then lysed overnight. Additional proteinase K was added if tissue was not dissolved following overnight incubation. Specimens were de-crosslinked for 1 h at 90 °C. After equilibration to room temperature, RNase A was added. Samples were washed and DNA was eluted in 50 μL of ATE buffer.

Qualitative RT-PCR for IDH Variant Detection

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens were analyzed for IDH1 and IDH2 variants using the Abbott RealTime IDH1 and IDH2 Assays (Abbott Molecular, Inc., Abbott Park, IL, USA), which are US Food and Drug Administration approved for detection in blood and bone marrow specimens. Briefly, homogeneous real-time fluorescence polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using the Abbott m2000rt identifies five single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in IDH1 (p.R132C, p.R132H, p.R132G, p.R132S, and p.R132L) and nine SNVs in IDH2 (p.R140Q, p.R140L, p.R140G, p.R140W, p.R172K, p.R172M, p.R172G, p.R172S, and p.R172W). Variant calling is performed by the Abbott m2000rt software and results are qualitatively reported as positive or not detected. Tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following exceptions incorporating previously validated workflow modifications. The archived FFPE specimen DNA used in this study was extracted as described above instead of the Abbott mSample Preparation SystemDNA Kit. A 1:3 dilution step was introduced into the IDH2 assay prior to testing to mimic the IDH1 assay protocol and normalize the specimen processing. The Abbott Realtime IDH1 and IDH2 Control Kit controls were extracted with the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and 10 ng of DNA was input into each reaction. While the Abbott method is qualitative, CT values can be read off the instrument. A standard input of 10 ng for each QIAamp extracted control was chosen to reflect the CT value observed for the controls when following the manufacturer’s extraction protocol.

Accuracy and Precision

Accuracy was assessed by comparing the concordance of qualitative results from the individual IDH assays to results from one of two in-house MPS panels. Additionally, the 47 specimens evaluated on the IDH1 assay were compared to immunohistochemical staining for the IDH1 variant R132H. Precision was assessed by analysis of inter-assay variability and intra-assay reproducibility. Cell line DNA with the R132H variant control was tested in triplicate by three operators over nine runs. The R172K variant control DNA was tested in triplicate by three operators over ten runs. To assess the precision of FFPE specimen, two samples, one positive (IDH1: R132H or IDH2: R172K) and one not detected, were tested on each assay in triplicate by three operators over 3 non-contiguous days utilizing multiple lots of reagents.

DNA Input

The amount of input DNA was calculated for all reactions of the IDH1 (n = 196 reactions) and IDH2 (n = 106 reactions) assays. Inputs ranged from 1.5 to 635 ng in the IDH1 assay and from 1.8 to 2940 ng in the IDH2 assay, both with a median input of 125 ng. IDH-positive and IDH-negative specimens were serially diluted into nuclease-free water to achieve inputs near the recommended minimum input.

Analytical Sensitivity

Variant detection at low allele frequencies was validated by making dilutions based off the variant allele frequency estimated by the sequencing panels. Serial dilutions were made using IDH wild-type FFPE samples with a similar tumor percentage. For example, a sample with an initial variant allele frequency (VAF) of 25% was diluted to VAFs of 12.5% and 6.25%, and continued until a VAF below 1% was achieved. Eight IDH1-mutant specimens, consisting of seven R132H variant specimens and one R132G variant specimen, were evaluated. Five IDH2-mutant specimens, consisting of two R172K variant specimens, one R172W variant specimen, and one R172M variant specimen were assessed. Dilutions were performed in triplicate. Concordance with the variant called for the undiluted specimen was assessed.

Comparator Methodology

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were stained with clone H09 of a monoclonal mouse anti-human IDH1 (R132H) antibody. Slides were pretreated for 20 min in BOND Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and then processed on the Bond III Autostainer. Positive areas are stained with DAB chromogen while hematoxylin stained the nuclei blue.

Sequencing Panels

Extracted DNA from clinical samples was run on one of two in-house sequencing panels. Both panels sequence the regions of IDH1 and IDH2 covered by the IHC and RT-PCR assays. DNA quality was assessed with the Qubit Broad Spectrum Range assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and the D1000 screen tape on the Agilent TapeStation (Aglient, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Samples with sufficient DNA quality were run on the solid tumor panel, while those with lower quality were reflexed to the Penn Precision Panel (PPP). Libraries were prepped with the Agilent HaloplexHS Target Enrichment System (Agilent) and loaded onto a HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced with 2 × 150 base pair reads. Low-yield solid tumor specimens were run on the PPP, which is optimized for low-yield specimens, as previously described [34]. Read coverage depth was ≥ 50× for the solid panel and ≥ 250× for PPP. An in-house pipeline combining the onboard Illumina HiSeq or MiSeq analysis with a custom-designed informatics workflow was used to process the data for each run. Variant calls were based on the human reference sequence UCSC build hg 19 (NCBI build 37.1). Sensitivities were ≥ 2% VAF for the solid panel and ≥ 5% VAF for PPP.

Clinical Application of Assay

The IDH mutation status was determined with both RT-PCR assays and sequencing studies for 48 brain tumors of patients who were diagnosed at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania between November 2019 and March 2022. It should be noted that for approximately 5 months during this period (November 2020–March 2021) tumor specimens were unable to be submitted for the in-house IDH1/2 RT-PCR assay because of prioritization of laboratory resources for coronavirus disease 2019 testing. Tumor specimens collected during this period were sent to an outside laboratory for assessment of IDH mutation status; therefore, these cases were not included in this study. A diagnosis of glioma or another type of primary central nervous system (CNS) neoplasm was confirmed by an experienced neuropathologist after surgical resection or stereotactic biopsy. The following clinical data were retrieved from electronic medical records and assessed: age at diagnosis, sex/gender, date of specimen collection, date of specimen receipt in laboratory for RT-PCR and sequencing studies, date of verification of results of RT-PCR and MPS, IDH1/2 mutation status based on results of RT-PCR and MPS, and final histopathologic diagnosis. This study was approved by an independent institutional review board at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP IRB 827290).

Results

Comparison of RT-PCR IHC and MPS

The performance of the Abbott IDH1 and IDH2 assays was evaluated using 51 unique FFPE specimens previously characterized on in-house sequencing panels. Concordance on both methods was assessed. Additionally, concordance with immunohistochemistry for the R132H variant of IDH1 was compared. Forty-five specimens (21 IDH1 wild-type and 24 IDH1 mutant) were tested on the IDH1 assay. Disease-associated variants in IDH1 included R132H (n = 17), R132G (n = 2), R132C (n = 1), and R132L (n = 1). Data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 below. An overall agreement of 100% (45/45) was observed between RT-PCR and MPS for detection of IDH1 mutations.

Table 1.

Concordance of IDH1 and IDH2 results between real-time polymerase chain reaction IDH assays, IHC, and MPS panel

| Abbott IDH1 assay | Abbott IDH2 assay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not detected | Detected | Not detected | Detected | |

| MPS panel | ||||

| Not detected | 24 | 0 | 12a | 0 |

| Detected | 0 | 21 | 0 | 5 |

| IHC | ||||

| R132H negative (other variants) | 24 | 1 (4) | ||

| R132H positive | 0 | 16 | ||

IDH isocitrate dehydrogenase, IHC immunohistochemistry, MPS massively parallel sequencing

aOne sample positive for variant E226K is not detectable on the polymerase chain reaction assay

Table 2.

Concordance of positive IDH1 and IDH2 results by variant

| IDH1 variant | Concordance | IDH2 variant | Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| R132C | 1/1 | R172K | 3/3 |

| R132H | 17/17 | R172M | 1/1 |

| R132G | 2/2 | R172W | 1/1 |

| R132L | 1/1 |

IDH isocitrate dehydrogenase

Comparison to IHC results was evaluated for all 45 specimens tested on the IDH1 assay. The IHC stain specifically identifies only the R132H variant of IDH1. One specimen was negative for R132H on IHC, but a R132H variant was detected both by PCR and the sequencing panel. This specimen was reclassified as a true false negative on the IHC. IDH mutant protein for four specimens was not detected by IHC but identified on the other methods. These four specimens harbor variants that are not detectable by the IHC stain. Following these resolutions, the positive qualitative agreement between these two methods was ~ 98%.

A total of 17 specimens (13 IDH2 wild-type and 5 IDH2 mutant) were evaluated on the IDH2 assay. Disease-associated variants in IDH2 included R172K (n = 3), R172W (n = 1), and R172M (n = 1). One specimen had a variant detected on the sequencing panel that was negative by PCR. This variant, E226K, was not expected to be detected by PCR. Therefore, following discrepancy resolution, all specimens were concordant for IDH2 mutation detection.

Specificity was determined using specimens with different IDH1 or IDH2 variants and the accuracy of variant calling was evaluated. There were no incorrect variant calls over the 150 reactions run with the 21 IDH1-positive specimens. One IDH2 specimen was run on the IDH1 assay with a result of ‘Not detected’. No incorrect variant calls were observed over 70 reactions of the five IDH2-positive specimens on the IDH2 assay. A total of seven IDH1 specimens were run on the IDH2 assay. All seven specimens were called ‘Not detected’. Additionally, one specimen with the IDH2 variant E226K was not detected by the IDH2 assay. These data suggest there is neither cross-reactivity nor non-specific variant detection occurring.

Limit of Detection and Analytical Sensitivity

DNA input from FFPE specimens was evaluated at, below, and above the manufacturer set minimum input of 10 ng. The amount of input DNA was calculated for all reactions of the IDH1 (n = 196 reactions) and IDH2 (n = 106 reactions) assays. Inputs ranged from 1.5 to 635 ng in the IDH1 assay and from 1.8 to 2940 ng in the IDH2 assay, both with a median input of 125 ng. While performance across a wide range of DNA inputs was successful, some samples with low levels of DNA (e.g., < 5 ng) showed low amplification of their internal control (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation of DNA input amounts

| DNA input (ng) | No. of samples | No. of amplified reactions (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDH1 | |||

| Variant not present | > 100 | 16 | 33/33 (100) |

| 5–100 | 5 | 9/9 (100) | |

| < 5 | 2 | 0/4 (0) | |

| Variant present | > 100 | 21 | 128/128 (100) |

| 5–100 | 6 | 16/16 (100) | |

| < 5 | 3 | 6/6 (100) | |

| IDH2 | |||

| Variant not present | > 100 | 10 | 10/10 (100) |

| 5–100 | 4 | 18/18 (100) | |

| < 5 | 8 | 4/8 (50) | |

| Variant present | > 100 | 3 | 47/47 (100) |

| 5–100 | 5 | 19/19 (100) | |

| < 5 | 2 | 4/4 (100) |

IDH isocitrate dehydrogenase

To resolve the low number of amplified reactions in the samples ≤ 5 ng, 20 samples were analyzed for genomic DNA degradation on the Aligent 4200 TapeStation. Nine of 20 samples harbored either an IDH1 or IDH2 variant; the remaining 11 samples contained no IDH variants. An overall average of 10% (range 1.4–36.4%; standard deviation 9.4%) degradation was observed. Five of the six total specimens that failed to amplify at or below 5 ng were analyzed and had an average degradation of 16.5% (range 7.1–36.4%; standard deviation 12%), indicating these amplification failures may be more likely in samples with higher degradation. However, as no amplification failures were observed above 5 ng, a conservative minimum input of 10 ng of DNA for a clinical specimen was implemented.

Analytical sensitivity was evaluated using dilutions of a positive specimen. Variant allele frequency was estimated from MPS results. Positive specimens were diluted two-fold into the negative specimen with the same tumor percentage to achieve predicted VAFs that ranged from 47 to 0.53%. There was a 100% detection rate for all samples at VAFs ≥ 2%, 1–2%, and < 1% (Table 4). Our data suggest that variant detection is accurate even at lower VAFs (< 1% in all replicates) than the manufacturer limit of detection for blood and bone marrow specimens. For all variants tested, the limit of detection was at least 2% VAF.

Table 4.

Limit of detection for IDH1 and IDH2 variants with a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay

| Variants | % VAF | No. of samples | No. of replicates | No. of detected (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R132G | ≥ 2 | 1 | 11 | 11 (100) |

| 1–2 | 1 | 3 | 3 (100) | |

| < 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 (100) | |

| R132H | ≥ 2 | 7 | 48 | 48 (100) |

| 1–2 | 7 | 27 | 27 (100) | |

| < 1 | 6 | 18 | 18 (100) | |

| R172K | ≥ 2 | 2 | 11 | 11 (100) |

| 1–2 | 2 | 9 | 9 (100) | |

| < 1 | 2 | 6 | 6 (100) | |

| R172W | ≥ 2 | 1 | 7 | 7 (100%) |

| 1–2 | 1 | 3 | 3 (100%) | |

| < 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 (100%) | |

| R172M | ≥ 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 (100%) |

| 1–2 | 1 | 6 | 6 (100%) | |

| < 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 (100%) |

VAF variant allele frequency

Intra- and Inter-Assay Variation

Acceptable criteria for assessing assay precision were defined as concordance with the expected variant call. Because of limited specimens, the validation of precision was completed with gDNA from R132H and R172K variant cell lines. Concordance within-run and between-runs was assessed. R132H and R172K cell lines were tested in triplicate by three different technologists. Precision was verified using a positive and negative FFPE sample on each assay. All samples were concordant with the expected results within and between runs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Assessment of intra- and inter-assay variation on a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay

| Gene | Variant | Source | Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDH1 | R132H | Cell line | 27/27 |

| R132H | FFPE | 9/9 | |

| Absent | FFPE | 9/9 | |

| IDH2 | R172K | Cell line | 27/27 |

| R172K | FFPE | 9/9 | |

| Absent | FFPE | 9/9 |

FFPE formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

Clinical Utilization of RT-PCR Assay with Comparison to MPS

There were 48 patients identified with a histopathologic diagnosis of glioma or another primary CNS neoplasm that were assessed for IDH1/2 mutations with both RT-PCR and MPS. Of all the patients in this study, 12 of the tumor specimens were found to have mutations in either IDH1 or IDH2 (25%). Within our cohort, nine patients (19%) had an IDH1 mutation, and three patients (6%) had an IDH2 mutation. The most common IDH mutation encountered was IDH1 p.R132H, which was seen in six patients. All the IDH mutations were detected in patients with a final histopathologic diagnosis of either IDH-mutant astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma. Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Demographic, diagnostic, and molecular characteristics of clinical samples

| Characteristic | All patients, N = 48 (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range, IQR) | 42 (24–72, 31–53) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 (38) |

| Male | 30 (62) |

| Tumor classification | |

| Glioblastoma, IDH wild-type, WHO grade 4 | 24 (50) |

| Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 2 | 4 (8) |

| Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 4 | 3 (6) |

| Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-codeleted, WHO grade 2 | 3 (6) |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-codeleted, WHO grade 3 | |

| Diffuse midline glioma, WHO grade 4 | 2 (4) |

| Low-grade glioma (one with FGFR1 variant, one with PTPN11 variant) | 2 (4) |

| Atypical glial cells, suspicious for glioma | 2 (4) |

| Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 3 | 2 (4) |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma, WHO grade 1 | 1 (2) |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, WHO grade 2 | 1 (2) |

| Dysembryoplastic neuropithelial tumor, WHO grade 1 | 1 (2) |

| Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor, WHO grade 1 | 1 (2) |

| Diffuse hemispheric glioma, H3 G34-mutant, WHO grade 4 | 1 (2) |

| Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, IDH wild-type, H3 wild-type, WHO grade 4 | 1 (2) |

| 1 (2) | |

| IDH1/2 mutation status | |

| IDH1 | 9 (19) |

| IDH2 | 3 (6) |

| Not detected | 36 (75) |

| IDH1/2 mutations detected | |

| IDH1 p.R132H | 6 (50) |

| IDH1 p.R132G | 2 (17) |

| IDH1 p.R132L | 1 (8) |

| IDH1 p.R132M | 1 (8) |

| IDH2 p.R172G | 1 (8) |

| IDH2 p.R172K | 1 (8) |

IDH isocitrate dehydrogenase, IQR interquartile range, WHO World Health Organization

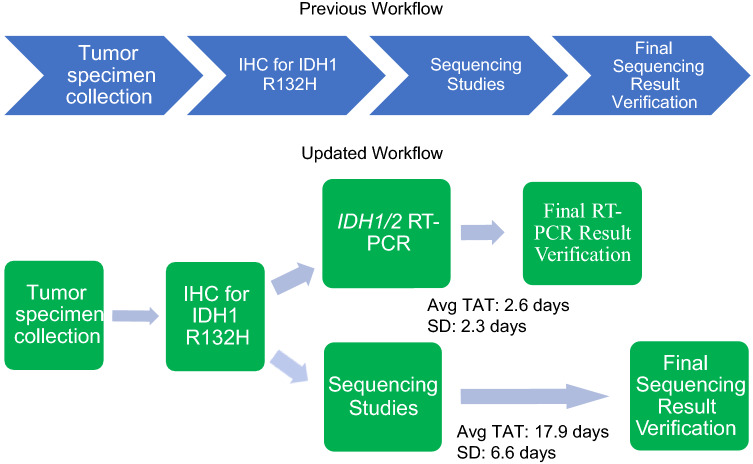

The average TAT for verification of RT-PCR results was 2.6 days (standard deviation 2.3 days), while the average TAT for verification of sequencing results was 17.9 days (standard deviation 6.6 days). Comparison of RT-PCR and MPS showed that there was an average 15.3-day lead time (p < 0.05) on obtaining the IDH mutation status from the RT-PCR assay compared with MPS (Fig. 1). All tumor specimens show concordant results between RT-PCR and MPS for IDH mutation status, including identification of the specific variant in either IDH1 or IDH2 (Table 7). It was shown that for patients who were found to have an IDH1 p.R132H variant on RT-PCR and MPS, corresponding IHC showed positive staining in five of the six tumor specimens. The one case where IHC was not considered positive was found to be uninterpretable on evaluation because of heavy background staining within the areas of the tumor.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of turnaround time (TAT) to diagnosis from having immunohistochemistry (IHC) -> next-generation sequencing versus including real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The first sequence depicts the two-step algorithm utilized for determination of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status for glioma tumor specimens, which includes IHC studies for IDH1 R132H with follow-up sequencing studies. The second sequence shows an alternative algorithm that utilizes the RT-PCR assay to determine IDH mutation status and has a faster average TAT than sequencing studies. Avg average, SD standard deviation

Table 7.

Results comparison across immunohistochemistry/RT-PCR/massively parallel sequencing in clinical samples

| Final histopathologic diagnosis | Tumor percentage (%) | RT-PCR result | Sequencing result | Variant allele frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q co-deleted, WHO grade 2 | 100 | IDH2 p.R172K | IDH2 (p.R172K, c.515G>A) | 43 |

| 2 | Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-codeleted, WHO grade 2 | 95–100 | IDH1 p.R132H | IDH1 (p.R132H, c.395G>A) | 24 |

| 3 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 2 | 100 | IDH1 p.R132L | IDH1 (p.R132L, c.395G>T) | 38 |

| 4 | Anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q co-deleted, WHO grade 3 | 100 | IDH1 p.R132H | IDH1 (p.R132H, c.395G>A) | 44 |

| 5 | Anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, 1p/19q co-deleted, WHO grade 3 | 99 | IDH1 p.R132H | IDH1 (p.R132H, c.395G>A) | 42 |

| 6 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 4 | 100 | IDH1 p.R132H | IDH1 (p.R132H, c.395G>A) | 57 |

| 7 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 2 | 95 | IDH1 p.R132H | IDH1 (p.R132H, c.395G>A) | 21 |

| 8 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 3 | 95 | IDH2 p.R172G | IDH2 (p.R172G, c.514A>G) | 34 |

| 9 | Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 2 | 100 | IDH1 p.R132G | IDH1 (p.R132G, c.394C>G) | 34 |

| 10 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 2 | 95 | IDH2 p.R172M | IDH2 (p.R172M, c.515G>T) | 37 |

| 11 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 2 | 90 | IDH1 p.R132G | IDH1 (p.R132G, c.394C>G) | 40 |

| 12 | Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, WHO grade 4 | 100 | IDH1 p.R132H | IDH1 (p.R132H, c.395G>A) | 43 |

IDH isocitrate dehydrogenase, RT-PCR real-time polymerase chain reaction, WHO World Health Organization

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the ability of a RT-PCR assay to detect IDH1/2 mutations as an alternative to MPS. This RT-PCR assay for IDH1/2 mutations has been found to be reliable and provide results of IDH1/2 mutation status more quickly when compared with sequencing studies. These findings suggest that determining IDH mutation status with this RT-PCR assay is a dependable method for detecting mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 in patients with glioma, providing a shorter time between surgical tumor specimen collection and molecular characterization after histopathologic diagnosis. By providing a faster means of determining IDH1/2 mutation status, clinical utilization of this RT-PCR assay may yield increased efficiency for implementing therapeutic interventions in patients with glioma as well as quicker enrollment in clinical trials, particularly those that administer selective IDH-mutant inhibitors [11, 29].

Before development of this RT-PCR assay at our institution, IHC studies for IDH1 R132H with follow-up MPS was the two-step algorithm utilized for determination of IDH mutation status for glioma tumor specimens. Despite its accuracy, use of this algorithm led to longer TATs for IDH profiling in glioma tumor specimens, especially for patients who had less common, non-IDH1 R132H mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 (Fig. 1). Previous studies showed that various assays using Sanger sequencing have been developed to detect IDH mutations; [35–40] however, some of these methods only target the most frequent IDH mutation, IDH1 R132H, or a limited panel of IDH1 mutations [36, 38–40]. In this study, we validated the performance of a new RT-PCR assay for IDH1/2 mutations on a cohort of FFPE tumor specimens, which can detect 14 single nucleotide variants in IDH1/2 (five SNVs in IDH1 and nine SNVs in IDH2). Given the completely concordant results with MPS during validation as well as its ability to detect a wide distribution of variants in IDH1/2, we show that this RT-PCR assay can serve as an alternative method to MPS in a two-step algorithm to determine IDH mutation status in patients with glioma.

We recognize that while useful in cases requiring a quick TAT for IDH1/2 analysis, there are limitations to this RT-PCR assay. In situations with limited tissue available, a more complete sequencing analysis, even with a longer TAT, is desirable to assess not only in IDH1/2 mutations but also genetic alterations in TERT, H3, and others. Therefore, in our practice, we carefully consider when to order IDH1/2 RT-PCR testing during initial triage of our specimens. For patients aged > 55 years, a negative IDH1-R132H stain can be interpreted as IDH wild-type with high confidence. These specimens will be routed for next-generation sequencing, which will confirm IDH1/2 status, and IDH1/2 RT-PCR will not be performed. IDH1/2 RT-PCR may be performed in patients aged > 55 years with positive IDH1-R132H staining if there is sufficient material for both PCR as well as next-generation sequencing. However, patients aged < 55 years may harbor less common IDH mutations, which can only be discovered after molecular investigation. Thus, the most common scenario where IDH1/2 RT-PCR is utilized is in patients aged < 55 years with equivocal IDH1-R132H staining and with sufficient tissue present for next-generation sequencing in addition to IDH1/2 RT-PCR. In the event that a patient aged < 55 years demonstrates equivocal or negative IDH1-132H staining and tissue is limited, IDH1/2 RT-PCR will not be pursued and available tissue is sent for next-generation sequencing. While sacrificing the TAT in terms of clarifying IDH status, the overall gain of information via complete sequencing to render an integrated diagnosis is of paramount importance. The quick TAT of the IDH1/2 PCR assay allows for faster confirmation of the mutation as IDH mutations are less frequent in this age group. Of note, while next-generation sequencing is always prioritized when tissue is limited, our molecular laboratory has optimized testing such that material for MGMT promoter analysis and IDH1/2 RT-PCR can be obtained from one small specimen. In cases where there is enough tissue for both MGMT promoter methylation testing as well as next-generation sequencing, the IDH1/2 RT-PCR assay can be performed using the genetic material obtained for MGMT promoter methylation analysis.

In addition to being accurate, another advantage of this RT-PCR assay is the ability to deliver rapid results in comparison to MPS. There have been several examples in the literature showing how PCR assays can provide rapid and accurate results compared with sequencing studies when determining IDH mutation status [32, 35, 41]. Catteau et al. developed a DNA-based PCR assay for IDH1/2 with the capability of determining IDH mutation status within only 5 h of DNA extraction from FFPE tumor specimens [32]. In this study, we show that the average TAT for RT-PCR for IDH1/2 mutations was approximately 2–3 days with 100% concordance with MPS. In comparison, MPS took approximately 2 weeks (15.3 days) longer to deliver a result compared with the RT-PCR assay. DNA-based sequencing studies have been found to be relatively more labor intensive, require sophisticated equipment and trained personnel, and are often not readily available in all institutions that evaluate glioma tumor specimens [32, 41]. Additionally, the sequencing panel, at its minimum input, requires 10× more DNA input than the PCR assay. Therefore, we propose this RT-PCR assay as a method that can provide rapid accurate results for IDH1/2 mutation status with minimal required input.

This study also showed that this RT-PCR assay has strong analytical sensitivity, with the ability to detect variants in IDH1/2 at a lower VAF. During validation of the assay, the data showed that detection of the 14 variants in IDH1 and IDH2 was accurate even at very low VAFs (<1% in all replicates). Additionally, for all variants tested, the limit of detection was at least 2% VAF. This RT-PCR shows higher sensitivity in comparison to Sanger sequencing, which typically detects levels as low as around 20% of the mutant allele load [32]. During clinical evaluation with this RT-PCR assay, 48 tumor specimens showed 100% concordance with MPS results, with VAFs that ranged between 21% and 57%. These findings suggest that this RT-PCR assay is a sensitive and specific method in detecting IDH1/2 mutations in patients with glioma. This outcome has been shown in other studies and emphasizes that DNA-based PCR assays are a reliable method for determination of IDH mutation status [32, 36, 41]. One of the weaknesses of this assay and other DNA-based assays is that the sensitivity of the method is greatly influenced by the quality of the tumor specimen obtained [41]. Although this RT-PCR assay can detect IDH1/2 mutations at a low VAF, tumor specimens are recommended to have a relatively high concentration of tumor cells in the demarcated area of the histologic section of the tumor specimen submitted for testing for best results. Studies have shown that issues arise with FFPE glioma specimens when there is low tumor cellularity given the infiltrative nature of these tumors or if there are areas of extensive necrosis or adjacent areas of normal tissue within the specimen submitted for testing [32, 41–43]. To ensure accurate results, it is recommended that glioma specimens with a high content of neoplastic cells based on an histopathologic evaluation are submitted, especially when the biopsy size is small or if there is a more infiltrative component of the tumor present [32, 41]. However, our study was limited in samples below 10% neoplastic cells to appropriately assess the impact of tumor cellularity.

Regarding IHC, RT-PCR was found to be in agreement with immunohistochemical studies for IDH1 R132H in 11 of 12 (92%) tumor specimens. It was shown that for patients who were found to have an IDH1 p.R132H variant on RT-PCR and MPS, corresponding IHC showed positive staining in five of the six tumor specimens. The one case where IHC was not considered positive was found to be uninterpretable on evaluation because of heavy background staining within the areas of the tumor. Although IHC is fast and inexpensive with high sensitivity, the method can suffer from issues with interpretation owing to weak or nonspecific background staining or regional heterogeneity of IDH1-R132H protein expression throughout the tumor [39, 44]. As mentioned previously, the algorithmic approach to the determination of IDH mutation status involves IHC for IDH1 R132H because this is the most frequent mutation in IDH-mutant gliomas and IHC is a reliable method that can quickly determine if this specific variant is present [3]. We propose that compared with sequencing, IHC for IDH1 R132H along with this RT-PCR assay for IDH1/2 mutations can provide faster results for IDH mutation status, especially for patients who are under the age of 55 years and are negative or equivocal for IDH1 R132H on immunohistochemical studies. This RT-PCR assay may also be utilized to provide a faster method to rule-out an IDH-mutant glioma and start considering alternative diagnoses such as IDH wild-type glioblastoma or gliomas without IDH mutations but with other specific entity-defining genetic abnormalities. Many of these gliomas, especially those seen in pediatric and young adult populations, are newly characterized entities based on specific recurrent molecular abnormalities that have been defined in the most recent edition of the WHO Classification of Central Nervous System Tumours [3].

There are a variety of testing modalities available for molecular characterization of brain tumors, and some of the more novel methods, such as MPS and DNA-methylation profiling, are able to identify genetic alterations and provide epigenetic profiles for different types of glioma tumor specimens [3, 32–34, 45]. Compared with other methods, sequencing studies allow for a more broad and in-depth molecular diagnostic analysis of tumor specimens, having the major advantage of assessing multiple molecular features in one study [33]. These studies are adept at simultaneous assessment of mutations, copy number alterations, fusion genes, and other genetic alterations necessary for the classification and treatment of primary CNS neoplasms [33, 45]. Despite the ability to provide more detailed comprehensive molecular information on tumor specimens, some disadvantages of MPS include higher costs, slower TAT for data analysis and delivery of results, higher input requirements, and use of technology that is not readily available in all neuropathological centers [32, 41, 46]. Studies have shown that compared with other molecular assays, sequencing studies can be highly expensive and less cost effective when utilized to assess various genetic abnormalities in glioma tumor specimens [31, 33, 46]. Recent studies found that across institutions the TAT for whole genome sequencing studies can range between 5 and 19 days, with each panel testing for a variable number of genes [47, 48]. However, the high costs of sequencing studies and slightly slower TATs do not outweigh the value of providing a comprehensive molecular analysis of glioma tumor specimens, which can yield significant information for treatment decisions and provide prognostic indications for specific types of tumors. Thus, despite the ability of this RT-PCR assay to provide accurate results with a faster TAT for IDH mutation status, this method should not serve as a replacement for sequencing studies for a comprehensive molecular assessment of gliomas. Furthermore, sequencing studies provide an assessment of multiple pathologic genetic abnormalities that are critical to the diagnostic work-up and classification of glioma tumor specimens, and the true clinical utility and added value of sequencing studies are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Some of the limitations for our study include the retrospective nature of the study and the data being sourced from a single institution. This study also has a relatively smaller series of patient specimens; however, the co-occurrence of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic during the start of the clinical evaluation with this RT-PCR assay likely played a major role in this outcome. However, a strength of this study is the inclusion of a wide variety of glioma and primary CNS tumor specimens submitted for clinical evaluation.

Conclusions

We have validated a PCR-based assay that provides rapid and accurate detection of 14 variants in IDH1 and IDH2 in FFPE glioma tumor specimens. The assay showed high sensitivity and reliability compared with sequencing studies during validation, proving its ability to be utilized in clinical practice. Additionally, this assay was incorporated into the clinical algorithm for IDH mutation status determination for patients with glioma and showed decreased TATs compared with sequencing studies. We recommend the combination of IHC for IDH1 RI32H and follow-up RT-PCR studies when IDH mutation status is specifically requested for the clinical assessment of patients with glioma.

Declarations

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this article.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Abbott Molecular Inc. sponsored Sarah E. Herlihy for a Lab Roots lecture of the validation data presented in this article. All data validation and analysis were completed prior to the service initiation. Ernest J. Nelson, Maria A. Gubbiotti, Alicia M. Carlin, MacLean P. Nasrallah, Vivianna M. Van Deerlin have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: EJN, MPN, SEH; methodology: EJN, AMC, SEH; formal analysis and investigation: EJN, MAG, AMC, VMVD, SEH; writing, original draft preparation: EJN, SEH; writing, review and editing: EJN, MAG, AMC, MPN, VMVD, SEH; supervision: MPN, VMVD, SEH.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Cote DJ, Ascha M, Kruchko C, et al. Adult glioma incidence and survival by race or ethnicity in the United States from 2000 to 2014. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):1254–1262. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leece R, Xu J, Ostrom OT, et al. Global incidence of malignant brain and other central nervous system tumors by histology, 2003–2007. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(11):1553–1564. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Central nervous system tumours. WHO classification of tumours. 5th edn. vol. 6. 2021. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/Central-Nervous-System-Tumours-2021..

- 4.Deng L, Xiong P, Luo Y, et al. Association between IDH1/2 mutations and brain glioma grade. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(4):5405–5409. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(5):492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witthayanuwat S, Pesee M, Supaadirek C, et al. Survival analysis of glioblastoma multiforme. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(9):2613–2617. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.9.2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JW, Turcan S. Epigenetic reprogramming for targeting IDH-mutant malignant gliomas. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1616. doi: 10.3390/cancers11101616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SongTao Q, Lei Y, Si G, et al. IDH mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in secondary glioblastoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(2):269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou P, Xu H, Chen P, et al. IDH1/IDH2 mutations define the prognosis and molecular profiles of patients with gliomas: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dang L, Yen K, Attar EC. IDH mutations in cancer and progress toward development of targeted therapeutics. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):599–608. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X, Hu H. The roles of 2-hydroxyglutarate. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:651317. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.651317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagné LM, Boulay K, Topisirovic I, et al. Oncogenic activities of IDH1/2 mutations: from epigenetics to cellular signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(10):738–752. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki H, Aoki K, Chiba K, et al. Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):458–468. doi: 10.1038/ng.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii T, Khawaja MR, DiNardo CD, et al. Targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) in cancer. Discov Med. 2016;21(117):373–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Losman JA, Kaelin WG., Jr What a difference a hydroxyl makes: mutant IDH, (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate, and cancer. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):836–852. doi: 10.1101/gad.217406.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, et al. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(6):597–602. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bleeker FE, Lamba S, Leenstra S, et al. IDH1 mutations at residue p.R132 (IDH1(R132)) occur frequently in high-grade gliomas but not in other solid tumors. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(1):7–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang C, Xu K, Shu HG. The role of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in glioma brain tumors. Molecular Targets of CNS Tumors. In: InTechOpen; 2011. 10.5772/23238.

- 21.Khan I, Waqas M, Shamim MS. Prognostic significance of IDH 1 mutation in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67(5):816–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bleeker FE, Atai MA, Lamba S, et al. The prognostic IDH1(R132) mutation is associated with reduced NADP+-dependent IDH activity in glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(4):487–494. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0645-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sledzinska P, Bebyn MG, Furtak J, et al. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in gliomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10373. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichimura K, Pearson DM, Kocialkowski S, et al. IDH1 mutations are present in the majority of common adult gliomas but rare in primary glioblastomas. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(4):341–347. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewandowska M, Furtak J, Szylberg T, et al. An analysis of the prognostic value of IDH1 (isocitrate dehydrogenase 1) mutation in Polish glioma patients. Mol Diagnosis Ther. 2014;18(1):45–53. doi: 10.1007/s40291-013-0050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai YT, Ning XB, Han GQ, et al. Assessment of the association between isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation and mortality risk of glioblastoma patients. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1501–1508. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molenaar RJ, Verbaan D, Lamba S, et al. The combination of IDH1 mutations and MGMT methylation status predicts survival in glioblastoma better than either IDH1 or MGMT alone. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(9):1263–1273. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, et al. IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in low-grade gliomas. Neurology. 2010;75(17):1560–1566. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f96282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma H. Development of novel therapeutics targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in cancer. Curr Top Med Chem. 2018;l8(6):505–524. doi: 10.2174/1568026618666180518091144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellinghoff IK, Ellingson BM, Touat M, et al. Ivosidenib in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1-mutated advanced glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(29):3398–3406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeWitt JC, Jordan JT, Frosch MP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of IDH testing in diffuse gliomas according to the 2016 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system recommendations. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(12):1640–1650. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catteau A, Girardi H, Monville F, et al. A new sensitive PCR assay for one-step detection of 12 IDH1/2 mutations in glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:58. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Synhaeve NE, van den Bent MJ, French PJ, et al. Clinical evaluation of a dedicated next generation sequencing panel for routine glioma diagnostics. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sussman RT, Shaffer S, Azzato EM, et al. Validation of a next-generation sequencing oncology panel optimized for low input DNA. Cancer Genet. 2018;228–229:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gondim DD, Gener MA, Curless KL, et al. Determining IDH-mutational status in gliomas using IDH1-R132H antibody and polymerase chain reaction. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2019;27(10):722–725. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bujko M, Kober P, Matyja E, et al. Prognostic value of IDH1 mutations identified with PCR-RFLP assay in glioblastoma patients. Mol Diagn Ther. 2010;14(3):163–169. doi: 10.1007/BF03256369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horbinski C, Kelly L, Nikiforov YE, et al. Detection of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations by fluorescence melting curve analysis as a diagnostic tool for brain biopsies. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12(4):487–492. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perizzolo M, Winkfein B, Hui S, et al. IDH mutation detection in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded gliomas using multiplex PCR and single-base extension. Brain Pathol. 2012;22(5):619–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urbanovska I, Megova MH, Dwight Z, et al. IDH mutation analysis in glioma patients by CADMA compared with SNaPshot assay and two immunohistochemical methods. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019;25(3):971–978. doi: 10.1007/s12253-018-0413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felsberg J, Wolter M, Seul H, et al. Rapid and sensitive assessment of the IDH1 and IDH2 mutation status in cerebral gliomas based on DNA pyrosequencing. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(4):501–507. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malueka RG, Theresia E, Fitria F, et al. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism, immunohistochemistry, and DNA sequencing for the detection of IDH1 mutations in gliomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(11):3229–3234. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.11.3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal S, Sharma MC, Jha P, et al. Comparative study of IDH1 mutations in gliomas by immunohistochemistry and DNA sequencing. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(6):718–726. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee D, Suh YL, Kang SY, et al. IDH1 mutations in oligodendroglial tumors: comparative analysis of direct sequencing, pyrosequencing, immunohistochemistry, nested PCR and PNA-mediated clamping PCR. Brain Pathol. 2013;23(3):285–293. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preusser M, Wohrer A, Stary S, et al. Value and limitations of immunohistochemistry and gene sequencing for detection of the IDH1-R132H mutation in diffuse glioma biopsy specimens. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70(8):715–723. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31822713f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reifenberger G, Wirsching HG, Knobbe-Thomsen CB, et al. Advances in the molecular genetics of gliomas: implications for classification and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(7):434–452. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bale TA, Jordan JT, Rapalino O, et al. Financially effective test algorithm to identify an aggressive, EGFR-amplified variant of IDH-wildtype, lower-grade diffuse glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(5):596–605. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banyi N, Alex D, Hughesman C, et al. Improving time-to-treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients through faster single gene EGFR testing using the Idylla EGFR testing platform. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(10):7900–7911. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29100624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duncavage EJ, Schroeder MC, O'Laughlin M, et al. Genome sequencing as an alternative to cytogenetic analysis in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(10):924–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]