Abstract

Background

For patients with opioid use disorder (OUD), medications for OUD (MOUD) reduce morbidity, mortality, and return to use. Nevertheless, a minority of patients receive MOUD, and underutilization is pronounced among rural patients.

Objective

While Veterans Health Administration (VHA) initiatives have improved MOUD access overall, it is unknown whether access has improved in rural VA health systems specifically. How “Community Care,” healthcare paid for by VHA but received from non-VA providers, has affected rural access is also unknown.

Design

Data for this observational study were drawn from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse. Facility rurality was defined by rural-urban commuting area code of the primary medical center. International Classification of Diseases codes identified patients with OUD within each year, 2015–2020. We included MOUD (buprenorphine, methadone, extended-release naltrexone) received from VHA or paid for by VHA but received at non-VA facilities through Community Care. We calculated average yearly MOUD receipt; linear regression of outcomes on study years identified trends; an interaction between year and rural status evaluated trend differences over time.

Participants

All 129 VHA Health Systems, a designation that encompasses one or more medical centers and their affiliated community-based outpatient clinics

Main Measures

The average proportion of patients diagnosed with OUD that receive MOUD within rural versus urban VHA health care systems.

Key Results

From 2015 to 2020, MOUD access increased substantially: the average proportion of patients receiving MOUD increased from 34.6 to 48.9%, with a similar proportion of patients treated with MOUD in rural and urban systems in all years. Overall, a small proportion (1.8%) of MOUD was provided via Community Care, and Community Care did not disproportionately benefit rural health systems.

Conclusions

Strategies utilized by VHA could inform other health care systems seeking to ensure that, regardless of geographic location, all patients are able to access MOUD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08027-4.

KEY WORDS: rural, veterans, access, opioid agonist, opioid use disorder

For patients diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD), receipt of medications for OUD (MOUD) is associated with substantial improvements in morbidity and mortality, as well as reduced rates of return to use.1–4 However, in the USA, a minority of patients receive MOUD.2 While access is suboptimal among all patients, it is more pronounced among rural patients.5–7 In 2018, 57% of rural US counties had no clinician approved to prescribe buprenorphine, while this was true of just 12% of large, metropolitan counties.8 Rural federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are also less likely to offer buprenorphine, relative to urban FQHCs.9 Rural patients face even greater barriers to accessing methadone, which requires frequent attendance at an opioid treatment program (OTP).10,11 Although federal policy changes responsive to the COVID pandemic have temporarily increased rural patients’ access to methadone via OTPs, methadone remains difficult to access for rural patients, who experience median drive times of 45+ min one way to access treatment.12

VHA has undertaken multiple initiatives to expand access to MOUD for patients generally and rural patients specifically. Such initiatives are justified given that approximately one-third of VHA patients are rural residents.7 Recent national efforts have included the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer Initiative, increased buprenorphine prescribing through telemedicine, external facilitation provided to low-performing sites, and an initiative to hire clinical pharmacists to address substance use disorders in rural settings.13–19

Access to MOUD in rural settings may also have been impacted by a national policy change enacted by Congress under the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act (2014) and finalized under the VA MISSION Act (2019). Under this legislation, VA patients who meet certain criteria (for instance, those who live >40 miles from a Veterans Health Administration facility) can be treated in a non-VA health care setting and have this care reimbursed by VHA. An explicit goal of this legislation was to enhance health care access for rural VA patients.20

In this study, we (1) describe trends in the proportion of VHA patients receiving MOUD from 2015 to 2020, (2) compare urban and rural VA health care systems across this outcome, and (3) measure the relative contribution of MOUD received from community providers in rural versus urban systems. We hypothesized that urban health systems would show improved patient access to MOUD relative to rural health systems, and that a larger proportion of MOUD would be provided by Community Care in rural relative to urban systems.

DATA AND SAMPLE

Data were drawn from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse, which contains national patient- and facility-level data for VHA, including care reimbursed by VHA but received through community providers via the Community Care Program. We examined data from all VHA health systems (n=129), a designation that encompasses medical centers and their affiliated outpatient clinics. Facility rurality was defined by the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) code of the VHA medical center. OUD was identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 9th and 10th Revisions diagnosis codes (Appendix Table 1). The first OUD diagnosis within each calendar year was the index diagnosis for that year; a second diagnosis within a 12-month period was required for validation.21 MOUD utilization was determined by inpatient or outpatient pharmacy records for buprenorphine, procedure codes for extended-release naltrexone, or clinic visits to an OTP. We excluded buprenorphine formulations indicated for pain. As a measure of accessibility, receipt of MOUD was determined by receipt of one or more prescription of buprenorphine, visit to an opioid treatment program, or injection of extended-release injectable naltrexone within 12 months of index OUD diagnosis.

We calculated health system-year specific rates of MOUD receipt by dividing the number of patients diagnosed with OUD in each facility in each calendar year by the number who received any MOUD within 12 months of the index diagnosis. We used linear regression of outcomes on study years to identify yearly trends; an interaction between year and rural status evaluated rural-urban trend differences over time. We calculated average rates of MOUD (received through VA and Community Care combined) for rural and urban health systems across study years (2015–2020), and calculated t-statistics to assess differences. We repeated this analysis examining trends in MOUD received through Community Care alone, and conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding data from the year 2020, representing the COVID period.

Reflecting some research suggesting that ICD codes may overrepresent the overall incidence of OUD in the VHA patient population, given potentially inaccurate diagnosis of OUD assigned to patients receiving long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) for chronic pain,22 we excluded patients who had received LTOT over the last 90/104 days of the calendar year, allowing for small gaps in prescriptions.23 We chose this approach as we did not want to inappropriately exclude patients who were diagnosed with OUD following cessation of an LTOT prescription. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the VA Portland Health Care System.

RESULTS

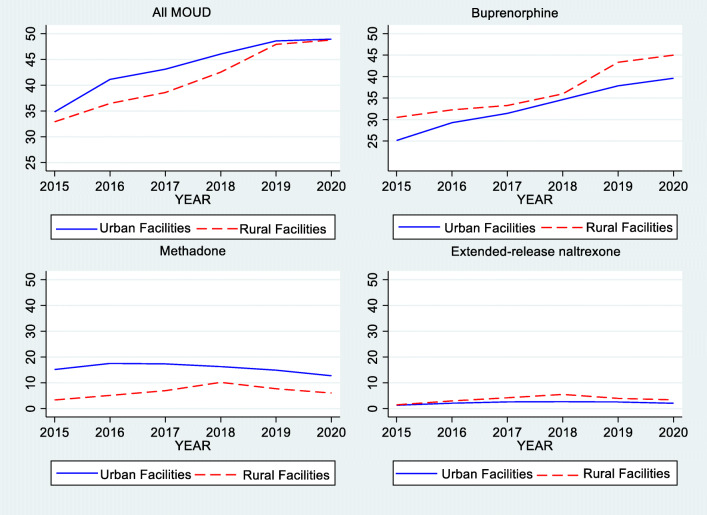

From 2015 to 2020, on average 51,765 patients were diagnosed with OUD per year. Of 129 VHA health systems, 15 (11.6%) were classified as rural by geographic location. Across health systems, the average proportion of patients receiving MOUD increased from 34.6% in 2015 to 48.9% in 2020. Increase was evident in both urban (34.8 to 48.9%) and rural (32.9 to 48.8%) systems.

Overall, the average proportion of patients receiving buprenorphine increased by 2.9%/year, compared to a 0.2%/year increase for extended-release naltrexone and .5%/year decline for methadone, with no difference in average yearly change between urban and rural systems (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average change per year in MOUD receipt for rural, urban and all VHA health care systems, 2015–2020

| Change per year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Overall | Urban | Rural | Difference |

| Medication for opioid use disorder |

2.8 (0.000) [2.3–3.3] |

2.7 (0.000) [2.2–3.3] |

3.36 (0.003) [1.2–5.5] |

0.6 (0.580) [−1.6–2.8] |

| Methadone |

−0.5 (0.162) [−1.1–0.2] |

−0.6 (0.075) [−1.3–0.1] |

0.7 (0.493) [−1.3–2.7] |

1.3 (0.227) [−0.8–3.4] |

| Buprenorphine |

2.9 (0.000) [2.4–3.4] |

2.9 (0.000) [2.4–3.4] |

3.1 (0.006) [0.9–5.3] |

0.2 (0.859) [−2.0–2.4] |

| Extended-release naltrexone |

0.2 (0.000) [0.1–0.3] |

0.1 (0.000) [0.1–0.2] |

0.4 (0.004) [0.1–0.7] |

0.2 (0.082) [-0.0–0.5] |

The table shows regression estimates, corresponding p-values in parenthesis, and 95% confidence intervals in square brackets. Estimates are based on linear regressions of outcomes on study years (2015 to 2020, overall change per year), and on linear regressions of outcomes on study years interacted with rural status (other three columns). Standard errors are clustered at the facility level

As shown in Fig. 1, rural health systems appear to rely more heavily on buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone and less on methadone to treat OUD relative to urban systems, although differences were largely not statistically significant. In 2020, 45.0% of patients in rural systems received buprenorphine relative to 39.6% in urban systems (p=0.097); 3.4% received extended-release naltrexone relative to 2.0% in urban systems (p=0.013) and 6.0% received methadone relative to 12.7% in urban systems (p=0.137) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Change in the use of a all MOUD, b buprenorphine, c methadone, and d extend-release injectable naltrexone from 2015 to 2020, rural versus urban VHA Health Care Systems

Table 2.

MOUD receipt for rural, urban and all VHA health care systems, 2020

| Proportion of patients receiving: | Overall | Rural | Urban | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All MOUD | 48.9 (12.3) | 48.8 (13.2) | 48.9 (12.2) | 0.959 |

| Methadone | 11.9 (16.4) | 6.0 (13.2) | 12.7 (16.7) | 0.137 |

| Buprenorphine | 40.2 (11.8) | 45.0 (13.5) | 39.6 (11.5) | 0.097 |

| Extended-release naltrexone | 2.2 (2.0) | 3.4 (2.8) | 2.0 (1.8) | 0.013 |

MOUD medications for opioid use disorder, VHA Veterans Health Authority. All data cells are listed as mean (standard deviation). Data includes MOUD received within VHA facilities as well as those paid for by VHA but accessed in non-VHA facilities via the Community Care Program

Table 3 reveals the average proportion of MOUD attributable to Community Care in each year (2015–2020). As shown, Community Care did not disproportionately benefit rural health systems. Overall, the average proportion of patients receiving MOUD through Community Care in rural systems was 0.8% relative to 1.9% within urban systems (p=0.011). Most of the difference was attributable to community-based methadone, which contributed to 2.0% of all methadone dispensing in urban health care systems but only 0.9% of all methadone dispensing in rural health care systems (p=0.010). In contrast, the proportion of buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone received through Community Care was similar between urban and rural systems. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded the year 2020 from this analysis, to test for possible differences given the COVID-19 pandemic. Results were consistent with the primary model (see Appendix Table 2).

Table 3.

MOUD receipt through community care: rural, urban and all VHA health care systems, 2015–2020

|

Proportion of patients receiving: |

Overall | Rural | Urban | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All MOUD | 1.8 (3.6) | 0.8 (1.2) | 1.9 (3.8) | 0.011 |

| Methadone | 1.9 (3.9) | 0.9 (1.4) | 2.0 (4.1) | 0.010 |

| Buprenorphine | 0.13 (0.3) | 0.13 (0.3) | 0.13 (0.4) | 0.865 |

| Extended release naltrexone | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.796 |

MOUD medications for opioid use disorder, VHA Veterans Health Administration. All data cells are listed as mean (standard deviation). Data includes only MOUD accessed in non-VHA facilities via the Community Care Program

As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded patients who had received LTOT for chronic pain in the last 90/104 days of each calendar year from our denominator of patients diagnosed with OUD. Overall, these results showed a roughly one percentage point higher proportion of VHA patients prescribed MOUD overall, but no differences from the primary analyses in terms of trends over time, rural-urban differences or proportion of MOUD received via non-VHA health systems through community providers.

DISCUSSION

Across VHA health care systems, there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD from 2015 to 2020. By 2020, nearly 50% of patients diagnosed with OUD had received MOUD, up from less than 35% just 6 years earlier. Much of this increase was attributable to greatly expanded use of buprenorphine. This rate of medication receipt is significantly higher than that documented in some other health systems. For instance, a recent report documenting receipt of MOUD among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries found that just 19% of beneficiaries diagnosed with OUD had accessed MOUD over the 9-month study period.24 Further, while prior research has documented geographic disparities in access to OUD treatment in non-VA healthcare systems,6 we identified no rural-urban disparity at the systems-level within VA, which appears to reflect greater utilization of buprenorphine within rural relative to urban VA systems. In 2022, VHA added injectable buprenorphine to the VA formulary, making it a covered pharmacy benefit, which will likely increase buprenorphine accessibility in rural settings even more.

Yet more work is needed. In 2020, of all patients diagnosed with OUD, less than half received a medication, either from or paid for by VHA, to treat their OUD. Barriers to providing MOUD that have been documented within VHA include perceived lack of time, lack of support to diagnose and treat OUD, and issues with credentialing and privileging waivered prescribers.25 A recent VHA Notice addressed some of these barriers, including directing VA facilities to remove buprenorphine prescribing as a delineated privilege and recommending reduced caseload expectations for those providing medical management of OUD.26 More generally, to ensure ongoing progress in MOUD accessibility, policy and systems-level changes that could increase the proportion of patients prescribed MOUD include addressing financial and regulatory barriers (e.g., eliminating the x-waiver to prescribe buprenorphine), and expanding access to MOUD in non-specialty clinical settings (primary care, emergency department) as well as criminal justice settings (prison, jail).25,27 Finalizing the temporary regulatory changes enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as relaxing methadone take-home policies and telemedicine requirements, and waiving the need for an in-person visit prior to prescribing buprenorphine, may also be considered. Notably, these policy changes substantially lowered the barriers for patients to receive MOUD and have thus far not been shown to have negatively impacted patient outcomes, including mortality.19,28–31

With a superior safety profile and fewer regulatory hurdles to prescribing, buprenorphine has overtaken methadone as the most common medication used to treat OUD within VHA. Nonetheless, it is important that methadone remain available to those patients who may prefer or benefit from it (e.g., patients with a high tolerance for opioids given fentanyl exposure). To target rural-urban disparities in access to methadone specifically, health care systems should consider establishing mobile clinics—linked with an existing OTP—as this is an available tool to reach underserved areas.10 Legislators might also evaluate changes to federal law, which limits provision of methadone to OTPs, to consider more accessible treatment settings, such as community-based pharmacies.6 Such changes would likely bolster methadone accessibility in rural areas, which would translate into greater availability of methadone through Community Care.

We acknowledge limitations to our investigation. First, we required two diagnoses of OUD for inclusion in our sample. However, this decision reflects prior research suggesting that a non-trivial number of OUD diagnoses in the VA medical record may inaccurately assign a diagnosis of OUD to patients.21 Second, our data describe average levels of MOUD use between rural and urban facilities; a patient-level analysis could show different trends. Third, we classified facility rurality based on the RUCA code of the primary medical center within the health system, as this is the classification system used by VHA. Other rural classification systems may yield differing results. Fourth, because we were interested in the relative accessibility of MOUD between rural and urban health care systems, we classified any MOUD over the course of a year as receiving MOUD (e.g., one prescription of buprenorphine, one visit to an opioid treatment program). However, patients could face barriers to MOUD retention attributable to rural residence, which would not be captured through this analysis. Finally, we are unable to observe MOUD that VHA patients may receive in other health care systems that is not paid for by VHA.

CONCLUSION

VHA has shown substantial growth in the use MOUD over a recent 6-year period, mostly attributable to expanded use of buprenorphine. A better understanding of the VHA initiatives that led to these improvements could inform strategies in non-VHA settings seeking to ensure that, regardless of geographic location, all patients are able to receive appropriate OUD treatment.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 28 kb)

Funding

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development (IK2HX003007) and resources from the VA Health Services Research and Development-funded Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care at the VA Portland Health Care System (CIN 13-404). No author reports having any potential conflict of interest with this study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. bmj. 2017;357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences E and Medicine. Medications for opioid use disorder save lives. National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed]

- 3.Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, Chaisson CE, McPheeters JT, Crown WH, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622–e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Wang N, Xuan Z, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137–45. doi: 10.7326/M17-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Showers B, Dicken D, Smith JS, Hemlepp A. Medication for opioid use disorder in rural America: A review of the literature. J Rural Ment Health. 2021;45(3):184. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrilla CHA, Moore TE, Patterson DG, Larson EH. Geographic distribution of providers with a DEA waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a 5-year update. J Rural Health. 2019;35(1):108–12. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin R. Rural Veterans Less Likely to Get Medication for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghertner R. US trends in the supply of providers with a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in 2016 and 2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107527. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones EB. Medication-Assisted Opioid Treatment Prescribers in Federally Qualified Health Centers: Capacity Lags in Rural Areas. J Rural Health. 2018;34(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joudrey PJ, Bart G, Brooner RK, Brown L, Dickson-Gomez J, Gordon A, et al. Research priorities for expanding access to methadone treatment for opioid use disorder in the United States: A National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network Task Force report. Subst Abuse. 2021;42(3):245–54. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1975344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amiri S, Lutz R, Socías ME, McDonell MG, Roll JM, Amram O. Increased distance was associated with lower daily attendance to an opioid treatment program in Spokane County Washington. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;93:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joudrey PJ, Edelman EJ, Wang EA. Drive Times to Opioid Treatment Programs in Urban and Rural Counties in 5 US States. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1310–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, Burden J, Codell NK, Mhatre-Owens A, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abuse. 2020;41(3):275–82. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagedorn HJ, Gustavson AM, Ackland PE, Bangerter A, Bounthavong M, Clothier B, Harris AH, Kenny ME, Noorbaloochi S, Salameh HA, Gordon AJ. Advancing Pharmacological Treatments for Opioid Use Disorder (ADaPT-OUD): an Implementation Trial in Eight Veterans Health Administration Facilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;3:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07274-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins EJ, Malte CA, Gordon AJ, Williams EC, Hagedorn HJ, Drexler K, et al. Accessibility to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder After Interventions to Improve Prescribing Among Nonaddiction Clinics in the US Veterans Health Care System. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2137238–e2137238. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354–9. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyse JJ, Mackey K, Kansagara D, Tuepker A, Gordon AJ, Korthuis PT, et al. Expanding access to medications for opioid use disorder through locally-initiated implementation. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2022;17(1):1–1. doi: 10.1186/s13722-022-00312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Tiffany E, Drexler K, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abuse. 2018;39(2):139–44. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frost MC, Zhang L, Kim HM, Lin L. (Allison). Use of and Retention on Video, Telephone, and In-Person Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2236298–e2236298. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell BA, Abel EA, Park D, Edmond SN, Leisch LJ, Becker WC. Validity of incident opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnoses in administrative data: a chart verification study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(5):1264–70. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06339-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagisetty P, Garpestad C, Larkin A, Macleod C, Antoku D, Slat S, et al. Identifying individuals with opioid use disorder: Validity of International Classification of Diseases diagnostic codes for opioid use, dependence and abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108583. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Carr TP, Deyo RA, Dobscha SK. Clinical characteristics of veterans prescribed high doses of opioid medications for chronic non-cancer pain. PAIN®. 2010;151(3):625–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries: Influence of CARES Act Implementation. [Internet]. 2022 Jan. Report No.: No. 29. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/data-highlight-jan-2022-opiod.pdf

- 25.Hawkins EJ, Danner AN, Malte CA, Blanchard BE, Williams EC, Hagedorn HJ, et al. Clinical leaders and providers’ perspectives on delivering medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder in Veteran Affairs’ facilities. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buprenorphine Prescribing for Opioid Use Disorder; VHA Notice 2022-02. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans health Administration; 2022.

- 27.Madras BK, Ahmad NJ, Wen J, Sharfstein J. Improving access to evidence-based medical treatment for opioid use disorder: strategies to address key barriers within the treatment system. NAM Perspect. 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Brothers S, Viera A, Heimer R. Changes in methadone program practices and fatal methadone overdose rates in Connecticut during COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;131:108449. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones CM, Compton WM, Han B, Baldwin G, Volkow ND. Methadone-involved overdose deaths in the US before and after federal policy changes expanding take-home methadone doses from opioid treatment programs. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(9):932–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amram O, Amiri S, Panwala V, Lutz R, Joudrey PJ, Socias E. The impact of relaxation of methadone take-home protocols on treatment outcomes in the COVID-19 era. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;20:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2021.1979991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore DT, Wischik DL, Lazar CM, Vassallo GG, Rosen MI. The intertwined expansion of telehealth and buprenorphine access from a prescriber hub. Prev Med. 2021;152:106603. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 28 kb)