Abstract

Gamma distributed delay differential equations (DDEs) arise naturally in many modelling applications. However, appropriate numerical methods for generic gamma distributed DDEs have not previously been implemented. Modellers have therefore resorted to approximating the gamma distribution with an Erlang distribution and using the linear chain technique to derive an equivalent system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). In this work, we address the lack of appropriate numerical tools for gamma distributed DDEs in two ways. First, we develop a functional continuous Runge–Kutta (FCRK) method to numerically integrate the gamma distributed DDE without resorting to Erlang approximation. We prove the fourth-order convergence of the FCRK method and perform numerical tests to demonstrate the accuracy of the new numerical method. Nevertheless, FCRK methods for infinite delay DDEs are not widely available in existing scientific software packages. As an alternative approach to solving gamma distributed DDEs, we also derive a hypoexponential approximation of the gamma distributed DDE. This hypoexponential approach is a more accurate approximation of the true gamma distributed DDE than the common Erlang approximation but, like the Erlang approximation, can be formulated as a system of ODEs and solved numerically using standard ODE software. Using our FCRK method to provide reference solutions, we show that the common Erlang approximation may produce solutions that are qualitatively different from the underlying gamma distributed DDE. However, the proposed hypoexponential approximations do not have this limitation. Finally, we apply our hypoexponential approximations to perform statistical inference on synthetic epidemiological data to illustrate the utility of the hypoexponential approximation.

Keywords: infinite delay equation, functional continuous Runge–Kutta methods, delay differential equations, linear chain trick

1. Introduction

Gamma distributed delay differential equations (DDEs), generically of the form

|

(1.1) |

have been extensively used in mathematical biology, epidemiology and pharmacometric modelling (Andò et al., 2020; Câmara De Souza et al., 2018; Cassidy, 2021; Champredon et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2018; Hurtado & Kirosingh, 2019; Smith, 2011). These models describe the influence of the past on the current state through the convolution integral

|

where  is the probability density function (PDF) of the gamma distribution. The initial value problem (1.1) is equipped with initial data in the form of the history function

is the probability density function (PDF) of the gamma distribution. The initial value problem (1.1) is equipped with initial data in the form of the history function  . Typically,

. Typically,  , where

, where  is a probability measure (Hale & Verduyn Lunel, 1993). The Radon–Nikodym derivative of

is a probability measure (Hale & Verduyn Lunel, 1993). The Radon–Nikodym derivative of  with respect to Lebesgue measure is the PDF

with respect to Lebesgue measure is the PDF  given by

given by

|

which is parameterized using the shape and scale parameters,  and

and  , respectively. While both these parameters can be positive reals, many authors, when considering applications, artificially restrict

, respectively. While both these parameters can be positive reals, many authors, when considering applications, artificially restrict  to integer values and (1.1) is thus an Erlang distributed DDE. This restriction is useful as these Erlang distributed DDEs can then be reduced to an equivalent system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) through the linear chain technique (MacDonald, 1978; Vogel, 1961). A major impediment to the implementation of the more general gamma distributed DDE is the lack of appropriate numerical techniques for their simulation (Breda et al., 2016; Diekmann et al., 2018, 2020b). Here, we address this impediment in two distinct manners, first, by implementing a functional continuous Runge–Kutta (FCRK) method to simulate (1.1) and, second, by deriving a finite dimensional approximation of (1.1) that is more accurate than the common Erlang approximation.

to integer values and (1.1) is thus an Erlang distributed DDE. This restriction is useful as these Erlang distributed DDEs can then be reduced to an equivalent system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) through the linear chain technique (MacDonald, 1978; Vogel, 1961). A major impediment to the implementation of the more general gamma distributed DDE is the lack of appropriate numerical techniques for their simulation (Breda et al., 2016; Diekmann et al., 2018, 2020b). Here, we address this impediment in two distinct manners, first, by implementing a functional continuous Runge–Kutta (FCRK) method to simulate (1.1) and, second, by deriving a finite dimensional approximation of (1.1) that is more accurate than the common Erlang approximation.

Currently, existing numerical tools for the simulation and study of DDEs with finite delays, such as the continuous Runge–Kutta methods described in Bellen et al. (2009) and implemented in major software packages, often perform poorly when the minimal delay is smaller than the numerical solution step-size, a phenomena termed ‘overlapping’. Since the minimal delay in the Gamma-distributed DDE (1.1) is zero, this class of DDEs always exhibits overlapping. FCRK methods naturally and efficiently deal with overlapping, but although they were first proposed in the 1970s (Maset et al., 2005; Tavernini, 1971), they still have not been widely implemented in software packages nor extended to the infinite delay case. In fact, numerical tools for problems with infinite delay have only recently started to be developed. Recent work for problems with infinite delay includes pseudo-spectral techniques (Diekmann et al., 2020b; Gyllenberg et al., 2018), and the development of ODE approximations of the gamma-distributed DDE without enforcing  (Koch & Schropp, 2015; Krzyzanski, 2019). Krzyzanski (2019) used the binomial theorem to develop an ODE approximation of a generic gamma distributed DDE. However, this approximation relies on truncating the infinite series expansion of the PDF of the gamma distribution at some finite value. While Krzyzanski (2019) does derive explicit error bounds dependent on the number of terms

(Koch & Schropp, 2015; Krzyzanski, 2019). Krzyzanski (2019) used the binomial theorem to develop an ODE approximation of a generic gamma distributed DDE. However, this approximation relies on truncating the infinite series expansion of the PDF of the gamma distribution at some finite value. While Krzyzanski (2019) does derive explicit error bounds dependent on the number of terms  in the series expansion, the artificial truncation of the convolution integral ensures that the numerical approximation is not consistent. In a related work focused on lifespan distributions, Koch & Schropp (2015) impose a fixed upper bound for the lifespan duration, then subdivide the interval of possible lifespan durations into

in the series expansion, the artificial truncation of the convolution integral ensures that the numerical approximation is not consistent. In a related work focused on lifespan distributions, Koch & Schropp (2015) impose a fixed upper bound for the lifespan duration, then subdivide the interval of possible lifespan durations into  sub-compartments. The populations in each sub-compartment are weighted according to the probability of a lifespan of that length when calculating the total population size. Once again, this method requires the modeller to determine a fixed upper bound of the lifespan duration and does not capture the full dynamics of the infinite delay DDE. The FCRK method developed in this work explicitly computes the improper convolution integral and eliminates the requirement that modellers impose artificial upper bounds when simulating (1.1). To our knowledge, the FCRK method developed in this work is the first numerical method that does not artificially truncate the infinite delay by imposing artificial bounds. Consequently, the FCRK method derived here is the first consistent numerical method for DDEs with infinite delay; while we focus on gamma distributed DDEs, our method should be straightforward to adapt to other distributed DDEs where the integrand in the convolution integral decays exponentially.

sub-compartments. The populations in each sub-compartment are weighted according to the probability of a lifespan of that length when calculating the total population size. Once again, this method requires the modeller to determine a fixed upper bound of the lifespan duration and does not capture the full dynamics of the infinite delay DDE. The FCRK method developed in this work explicitly computes the improper convolution integral and eliminates the requirement that modellers impose artificial upper bounds when simulating (1.1). To our knowledge, the FCRK method developed in this work is the first numerical method that does not artificially truncate the infinite delay by imposing artificial bounds. Consequently, the FCRK method derived here is the first consistent numerical method for DDEs with infinite delay; while we focus on gamma distributed DDEs, our method should be straightforward to adapt to other distributed DDEs where the integrand in the convolution integral decays exponentially.

The main difficulty in applying FCRK methods to infinite delay problems is the evaluation of the semi-infinite convolution integral. Our main new contribution to FCRK methods is to demonstrate how to do this both accurately and efficiently. To achieve this, we derive a novel change of variable to map the semi-infinite domain of integration to a compact interval. While many changes of variables exist to map semi-infinite to compact domains of integration, our approach is derived to conserve sufficient regularity and therefore ensure the accuracy of our numerical method. In particular, we derive explicit conditions to ensure sufficient regularity of the transformed integrand that depend only on the parameters of the PDF  . Then, existing composite Newton–Cotes methods are utilized to numerically calculate the transformed convolution integral and thus efficiently evaluate the right-hand side of (1.1). To ensure the accuracy of the FCRK method, we derive order conditions on the quadrature method which allow us to evaluate the integrals just sufficiently accurately to maintain the global order of the FCRK method. In particular, we establish an explicit relationship between the stepsize of the FCRK method and the stepsize of the quadrature method. We prove the fourth-order convergence of our FCRK method in Theorem 2.1 and Appendix C and demonstrate the accuracy of our FCRK method through a number of examples in Section 4.1.

. Then, existing composite Newton–Cotes methods are utilized to numerically calculate the transformed convolution integral and thus efficiently evaluate the right-hand side of (1.1). To ensure the accuracy of the FCRK method, we derive order conditions on the quadrature method which allow us to evaluate the integrals just sufficiently accurately to maintain the global order of the FCRK method. In particular, we establish an explicit relationship between the stepsize of the FCRK method and the stepsize of the quadrature method. We prove the fourth-order convergence of our FCRK method in Theorem 2.1 and Appendix C and demonstrate the accuracy of our FCRK method through a number of examples in Section 4.1.

Inspired by the lack of readily available appropriate numerical methods for problems such as (1.1), there has also been considerable interest in approximating infinite delay DDEs by forms that are more convenient for simulation (Cassidy et al., 2019; Diekmann et al., 2018, 2020a; Hurtado & Kirosingh, 2019; Koch & Schropp, 2015; Krzyzanski, 2019). The most well-known of these is the previously mentioned linear chain technique, wherein modellers often make the simplifying assumption that  when implementing gamma distributed DDE models. We refer to this assumption as the Erlang approximation. However, this assumption imposes constraints on the sample mean and variance of the delayed process. Typically, for a general gamma-distributed random variable with mean

when implementing gamma distributed DDE models. We refer to this assumption as the Erlang approximation. However, this assumption imposes constraints on the sample mean and variance of the delayed process. Typically, for a general gamma-distributed random variable with mean  and variance

and variance  , modellers impose

, modellers impose  , where

, where  rounds

rounds  to the nearest integer with

to the nearest integer with  (Cassidy & Craig, 2019; Jenner et al., 2021). As a result, it is only possible to fit one of these statistics with an Erlang distribution, as the system

(Cassidy & Craig, 2019; Jenner et al., 2021). As a result, it is only possible to fit one of these statistics with an Erlang distribution, as the system

|

only admits a solution if  which corresponds to

which corresponds to

In light of this limitation of the Erlang approximation, recent work has explored using phase type distributions to approximate generic distributed DDEs. These phase-type distributed DDEs are then reduced to a system of ODEs through a variant of the linear chain technique (Cassidy, 2021; Hurtado & Richards, 2020; Hurtado & Kirosingh, 2019). These phase-type distributions approximate the underlying distribution either by minimizing some distance measurement between distributions or by matching moments of the underlying distribution. We take the latter approach when developing a novel hypoexponential approximation of the generic gamma distributed DDE (1.1). Existing work has identified the ‘reachable’ bounds in moment space and the minimal number of phases required to match the first three moments of the underlying distribution using phase type distributions (Bobbio et al., 2005; Johnson & Taaffe, 1989, 1990). However, in general, it may not be possible to match the first three moments, and even if it is possible, the required number of phases can be arbitrarily high (Osogami & Harchol-Balter, 2006). In fact, we prove in Theorem 3.3 that it is not possible to match three or more moments of a generic gamma distribution using purely hypoexponential distributions. Accordingly, we only match the first two moments of the underlying gamma distribution. We match the first two moments without imposing any restrictions on their values, and the parameters of our approximating phase-type distribution are entirely determined by the mean and variance of the underlying distribution. Moreover, our approximation is exact if the underlying distribution is Erlang.

To achieve this two moment matching, we derive explicit rates of the hypoexponential approximation to match the first two moments of a given gamma distribution and then derive the equivalent system of ODEs. These ODE models are simple to study numerically and have the added benefit of being easy to implement in scientific software packages and explain for scientific collaborators. Furthermore, we leverage our FCRK method to simulate (1.1) and thus explicitly evaluate the accuracy of our hypoexponential approximation by comparison against solutions obtained from our FCRK method, which has not been done in prior work. As we will show, our approximation more accurately captures the dynamics of the underlying gamma distributed DDE than the Erlang approximation obtained by setting  while being as simple to implement in existing scientific software as the common Erlang approximation.

while being as simple to implement in existing scientific software as the common Erlang approximation.

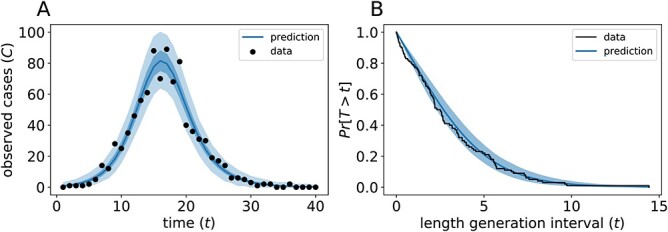

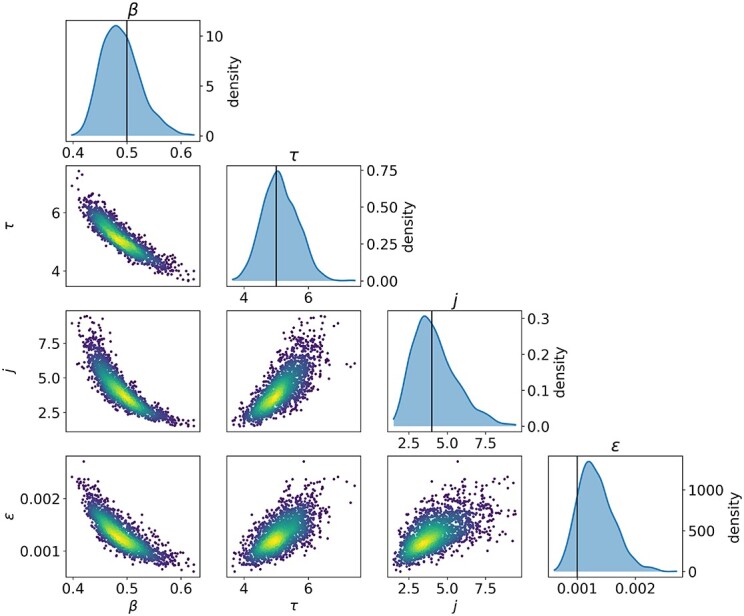

Finally, we apply our hypoexponential approximation to the problem of statistical inference. Erlang delay models are often used in epidemiology of infectious diseases (Champredon et al., 2018; Greenhalgh & Rozins, 2021; Rozhnova et al., 2021; Sanche et al., 2020) but also in many other fields (Câmara De Souza et al., 2018; Cassidy, 2021; Cassidy & Humphries, 2019; Gossel et al., 2017). A common approach is to define an epidemiological model in terms of ODEs and estimate parameters by fitting the model to disease incidence data. One key parameter, the basic reproduction number  , is closely related to the generation interval (or it is proxy the serial interval), the initial exponential growth rate of the epidemic and time to recovery

, is closely related to the generation interval (or it is proxy the serial interval), the initial exponential growth rate of the epidemic and time to recovery  (Roberts & Heesterbeek, 2007). This relationship depends not only on the mean infectious period

(Roberts & Heesterbeek, 2007). This relationship depends not only on the mean infectious period  but also on the distribution of this period. Therefore, making invalid assumptions about this distribution can lead to spurious estimates of, e.g.,

but also on the distribution of this period. Therefore, making invalid assumptions about this distribution can lead to spurious estimates of, e.g.,  and the corresponding critical vaccination coverage. The same argument holds for other intervals with randomly distributed durations such as the duration of the period that an individual has been exposed, but is not yet infectious (

and the corresponding critical vaccination coverage. The same argument holds for other intervals with randomly distributed durations such as the duration of the period that an individual has been exposed, but is not yet infectious ( ).

).

In practice, the random times  and

and  are often assumed to be

are often assumed to be  -distributed so that the DDEs can simply be implemented as ODEs using the linear chain technique. This is convenient because ODE models are easy to implement in commonly used software packages for statistical inference (Carpenter et al., 2017), whereas support for DDE models is much less common and often restricted to an Erlang distributed or fixed delays (Lixoft, 2019; Raue et al., 2014, 2009). Apart from convenience, there is no reason to assume that the distributions of

-distributed so that the DDEs can simply be implemented as ODEs using the linear chain technique. This is convenient because ODE models are easy to implement in commonly used software packages for statistical inference (Carpenter et al., 2017), whereas support for DDE models is much less common and often restricted to an Erlang distributed or fixed delays (Lixoft, 2019; Raue et al., 2014, 2009). Apart from convenience, there is no reason to assume that the distributions of  and

and  should be

should be  instead of gamma distributions. The hypoexponential approximation of the gamma distribution proposed here still allows for an ODE approximation of the DDE model but removes the need to assume that the shape

instead of gamma distributions. The hypoexponential approximation of the gamma distribution proposed here still allows for an ODE approximation of the DDE model but removes the need to assume that the shape  parameter is an integer.

parameter is an integer.

Another purely practical reason for using the hypoexponential approximation of the gamma distribution instead of an  distribution is that estimating the integer shape parameter

distribution is that estimating the integer shape parameter  of the Erlang distribution can be inconvenient in some software packages. For instance, in the commonly used package for Bayesian inference Stan (Carpenter et al., 2017), the estimated parameters have to be real-valued due to the limitations imposed by the Hamiltonian Monte-Carlo method. Accordingly, to estimate an integer valued

of the Erlang distribution can be inconvenient in some software packages. For instance, in the commonly used package for Bayesian inference Stan (Carpenter et al., 2017), the estimated parameters have to be real-valued due to the limitations imposed by the Hamiltonian Monte-Carlo method. Accordingly, to estimate an integer valued  , modellers must repeat the analysis for multiple fixed values of

, modellers must repeat the analysis for multiple fixed values of  and compare the results with Bayes factors or information criteria as LOO-IC or WAIC (Vehtari et al., 2017). This extra step, and the resulting extra computation, can be avoided if

and compare the results with Bayes factors or information criteria as LOO-IC or WAIC (Vehtari et al., 2017). This extra step, and the resulting extra computation, can be avoided if  is allowed to be real-valued and estimated by the software package, as when using either the FCRK method or the approximation derived in this work. However, updating existing scientific software to use our FCRK method would be much more time-consuming than using our hypoexponential approximation. Consequently, we implement the hypoexponential approximation in Stan and use the resulting ODE system for statistical inference of epidemiological parameters and evidence synthesis, thus illustrating a simple application of the hypoexponential approximation derived in this work.

is allowed to be real-valued and estimated by the software package, as when using either the FCRK method or the approximation derived in this work. However, updating existing scientific software to use our FCRK method would be much more time-consuming than using our hypoexponential approximation. Consequently, we implement the hypoexponential approximation in Stan and use the resulting ODE system for statistical inference of epidemiological parameters and evidence synthesis, thus illustrating a simple application of the hypoexponential approximation derived in this work.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. We begin by developing a numerical method to simulate the general gamma distributed DDE by using the theory of FCRK methods to address overlapping in the convolution integral in Section 2. We then give sufficient conditions to ensure that our evaluation of the semi-infinite convolution integral conserves the accuracy of the underlying FCRK method by proving the convergence of our method in Section 2.1.1 and Appendix C. Next, in Section 3, we develop our hypoexponential approximation by considering a more generic concatenation of exponentially distributed waiting times than the Erlang distribution and allowing for the rate parameters to vary between compartments. In Section 3.2, we derive explicit expressions of these rates that replicate the first and second moments of the gamma distribution in (1.1). Turning to numerical results, we confirm that the FCRK method derived in Section 2 performs to the proven accuracy in Section 4.1. Then, by leveraging the numerical simulation of the gamma distributed DDE (1.1), we show that the hypoexponential approximation outperforms the common Erlang approximation of the underlying gamma-distributed DDE in Section 4.2. The comparison between the Erlang and hypoexponential approximations against the true solution of the distributed DDE obtained via our FCRK method has not been performed previously. As the most striking illustration, we show in Section 4.2.1 that the Erlang-distributed DDE does not necessarily replicate the qualitative properties of the underlying gamma-distributed DDE. Finally, we illustrate how to implement the hypoexponential approximation to estimate the parameters of an epidemiological model in Stan in Section 5 before finishing with a brief discussion.

1.1 Notation and assumptions

Choosing an appropriate state space for DDEs with infinite delay can be subtle (Cassidy & Humphries, 2019; Hale & Verduyn Lunel, 1993). Here, for fixed  , we follow Diekmann & Gyllenberg (2012); Gyllenberg et al. (2018); Hino et al. (1991) and consider the state space

, we follow Diekmann & Gyllenberg (2012); Gyllenberg et al. (2018); Hino et al. (1991) and consider the state space  given by

given by

|

(1.2) |

is a Banach space under the norm

is a Banach space under the norm

|

In practice, we take  so that the convolution integral in (1.1) converges at time

so that the convolution integral in (1.1) converges at time  .

.

The IVP (1.1) has a unique solution  if

if  is globally Lipschitz (Diekmann & Gyllenberg, 2012). We immediately obtain that the solution

is globally Lipschitz (Diekmann & Gyllenberg, 2012). We immediately obtain that the solution  is continuous on

is continuous on  . However, to establish the accuracy of the FCRK method, we require further differentiability of the solution

. However, to establish the accuracy of the FCRK method, we require further differentiability of the solution  , and consequently, the function

, and consequently, the function  . In general, the convolution integral in (1.1) smooths the initial function

. In general, the convolution integral in (1.1) smooths the initial function  for

for  , as the kernel

, as the kernel  is analytic, and ensures that the only possible breaking point is

is analytic, and ensures that the only possible breaking point is  . Then, if the function

. Then, if the function  is

is  -times differentiable,

-times differentiable,  is

is  times differentiable for

times differentiable for

Throughout the paper, we use the following notation. If  , then the ceiling and floor of

, then the ceiling and floor of  are defined as

are defined as  and

and  , respectively. The fractional part of

, respectively. The fractional part of  is denoted

is denoted  . The nearest integer to

. The nearest integer to  is denoted

is denoted  . We parameterize the gamma distribution with shape and rate parameters and denote a gamma distribution with shape parameter

. We parameterize the gamma distribution with shape and rate parameters and denote a gamma distribution with shape parameter  and rate parameter

and rate parameter  by

by  . Hence, when a random variable

. Hence, when a random variable  , then

, then  has mean

has mean  and variance

and variance  . Similarily, we denote a hypoexponential distribution with rates

. Similarily, we denote a hypoexponential distribution with rates  by

by  . Finally, we denote the function segment

. Finally, we denote the function segment  for

for  .

.

2. FCRK methods

Most existing numerical methods for DDEs have been adapted from known numerical methods for ODEs (Bellen et al., 2009; Enright & Hayashi, 1997; Eremin, 2016; Vermiglio, 1988). For a given stepsize  and integration mesh given by

and integration mesh given by  , these continuous Runge–Kutta (CRK) methods are designed to output a continuous function over the delay interval. This continuous function is then used to evaluate the solution at the abscissa

, these continuous Runge–Kutta (CRK) methods are designed to output a continuous function over the delay interval. This continuous function is then used to evaluate the solution at the abscissa  of the RK method, which is necessary for accurate evaluation of the intermediate functions in each CRK step, since these fall at time points

of the RK method, which is necessary for accurate evaluation of the intermediate functions in each CRK step, since these fall at time points  which typically do not fall on the integration mesh. This illustrates another difficulty with CRK methods: when the delay

which typically do not fall on the integration mesh. This illustrates another difficulty with CRK methods: when the delay  is smaller than the stepsize

is smaller than the stepsize  , as if

, as if  , then overlapping will occur, i.e. the

, then overlapping will occur, i.e. the  st step will require knowledge of the solution in the current step (Eremin, 2019; Eremin et al., 2020), and the method can no longer be explicit. Overlapping is inevitable when solving (1.1) since the convolution integral in (1.1) requires knowledge of the solution

st step will require knowledge of the solution in the current step (Eremin, 2019; Eremin et al., 2020), and the method can no longer be explicit. Overlapping is inevitable when solving (1.1) since the convolution integral in (1.1) requires knowledge of the solution  on the entire semi-infinite interval

on the entire semi-infinite interval  .

.

A class of methods, now called FCRK methods, has been developed which have a continuous interpolant associated with each stage of the Runge–Kutta method, allowing for the construction of methods which remain explicit even in the case of overlapping. Such methods were first proposed in the 1970s (Cryer & Tavernini, 1972; Tavernini, 1971), with the convergence theory and construction of explicit methods up to order 4 derived in the 2000s (Bellen et al., 2009; Maset et al., 2005). However, the development of the methods to that point had been purely theoretical, and the works cited above do not contain any implementations or numerical simulations. FCRK methods have recently been implemented for distributed DDEs with possibly time dependent, but finite, delay (Eremin, 2019; Langlois et al., 2017). To our knowledge, Langlois et al. (2017) was the first instance of applying these FCRK methods to explicitly simulate a distributed DDE arising in mathematical biology. Here, we implement a fourth-order FCRK method for the infinite delay initial value problem (1.1). In what follows, we consider fixed time step methods and leave the variable time step case to future work.

Following Definition 6.1 of Bellen et al. (2009), we define an s-stage FCRK method as follows.

Definition 2.1.

-stage FCRK method —

A

-stage FCRK method is a triple

such that

and

are polynomial functions into

and

, respectively, with

and

, and

with

It is customary to represent a  -stage FCRK method

-stage FCRK method  by its Butcher tableau

by its Butcher tableau

|

where  and

and  and

and  are the components of

are the components of  and

and  Now, for a given step size

Now, for a given step size  , the

, the  -stage FCRK method creates a continuous approximation

-stage FCRK method creates a continuous approximation  to the solution of the IVP (1.1)

to the solution of the IVP (1.1)  through

through

|

(2.1) |

The stage interpolant  is a continuous approximation of the solution

is a continuous approximation of the solution  defined by

defined by

|

(2.2) |

where

|

(2.3) |

are the stage variables,  represents the numerical approximation of the solution up to the current stage and

represents the numerical approximation of the solution up to the current stage and  is the continuous approximation of

is the continuous approximation of  in the stage given by

in the stage given by

|

Thus, the piecewise interpolants  agree with

agree with  at the collocation points

at the collocation points  and define the piecewise continuous polynominal function

and define the piecewise continuous polynominal function  . For (1.1) with history function

. For (1.1) with history function  and stepsize

and stepsize  computed up to

computed up to  , the local error function is given by

, the local error function is given by

|

The uniform and discrete order of an FCRK method are intrinsically related to this local error function (see Equation (1.2) and Definition 4.1 in Maset et al. (2005)). The uniform order of an FCRK method is the maximal error incurred over a single time step:

Definition 2.2. Uniform order. —

Let

be a positive integer and let

be the approximation of the solution

of an IVP with sufficiently smooth right hand side obtained using an FCRK method with step size

. The FCRK method has uniform order

if

Conversely, the discrete order is the error incurred at the collocation points  , which corresponds to

, which corresponds to  in the definition of

in the definition of  :

:

Definition 2.3. Discrete order. —

Let

be a positive integer and let

be the approximation of the solution

of an IVP with sufficiently smooth right-hand side obtained using an FCRK method with step size

. The FCRK method has discrete order

if

Finally, the global order of the numerical method is the absolute error incurred throughout the simulation when considering the solution  and

and  as continuous functions on the interval

as continuous functions on the interval  .

.

Definition 2.4. Global order. —

A

-stage method has global order

if

The connection between the local error measurements given in Definitions 2.2 and 2.3 and the global order of an FCRK method is considered by Bellen & Zennaro (2013) and Bellen et al. (2009). Explicitly, if the  -stage method has global order

-stage method has global order  on

on  , then

, then  is a

is a  th order approximation of

th order approximation of  as

as

|

In what follows, we use the fourth-order explicit FCRK method due to Tavernini (1971) with global fourth order and Butcher tableau given by (Bellen et al., 2009)

|

(2.4) |

although our results hold for other FCRK schemes.

2.1 Numerical quadrature

In theory, FCRK methods are directly applicable to the infinite delay case (1.1). However, in practice, a s-stage FCRK method implicitly assumes the ability to accurately calculate the right-hand side of equation (1.1). Accordingly, the main difficulty in numerically simulating (1.1) is the numerical calculation of the improper convolution integral

|

appearing in (2.3).

Most numerical quadrature methods are designed for a compact domain of integration. However, artificially truncating the convolution integral in (1.1) would introduce unnecessary error while simultaneously ensuring that the FCRK method is not consistent as the quadrature stepsize,  , converges to 0. Thus, to compute the convolution integral, we map the semi-infinite domain of integration to the compact set

, converges to 0. Thus, to compute the convolution integral, we map the semi-infinite domain of integration to the compact set  through the change of variables

through the change of variables

|

where  and

and  are two parameters determined later. The improper integral then becomes

are two parameters determined later. The improper integral then becomes

|

(2.5) |

In general, we require a  times continuously differentiable integrand for a

times continuously differentiable integrand for a  th order composite Newton–Cotes quadrature method to obtain

th order composite Newton–Cotes quadrature method to obtain  th order accuracy. To ensure that our change of variable does not prohibit achieving such accuracy, we show how to choose the positive constants

th order accuracy. To ensure that our change of variable does not prohibit achieving such accuracy, we show how to choose the positive constants  and

and  to ensure that the transformed integrand is sufficiently smooth for our numerical integration techniques. This requirement is naturally dependent on the smoothness of the solution

to ensure that the transformed integrand is sufficiently smooth for our numerical integration techniques. This requirement is naturally dependent on the smoothness of the solution  and the history function

and the history function  Furthermore, even if

Furthermore, even if  is differentiable, it is likely that

is differentiable, it is likely that

|

where the superscripts denote limits from the left and right, so the solution  is not continuously differentiable at

is not continuously differentiable at  (Bellen et al., 2009). Accordingly, when implementing a numerical quadrature method, we will enforce that transformed initial point

(Bellen et al., 2009). Accordingly, when implementing a numerical quadrature method, we will enforce that transformed initial point  is part of the integration mesh. We now show how to choose

is part of the integration mesh. We now show how to choose  and

and  to ensure that the integrand is sufficiently smooth away from this breaking point.

to ensure that the integrand is sufficiently smooth away from this breaking point.

Lemma 2.1.

Assume that

is

times differentiable and set

(2.6) Then,

is

times differentiable in

for

. Furthermore, if the

th derivative of

,

, is bounded for

, then there exists

such that

for

.

The proof of Lemma 2.1 is straightforward and follows from the rapid decay of  at

at  . This decay, along with the fact that the history function

. This decay, along with the fact that the history function  belongs to the function space

belongs to the function space  for

for  , ensures that

, ensures that  as

as  . We give the full proof in Appendix A. In practice, we use the fifth-order open composite Simpson’s rule, which is the fifth-order composite open Newton–Cotes method, and require the integrand to have a bounded fourth derivative. Therefore, when implementing the FCRK method, we apply (2.6) with

. We give the full proof in Appendix A. In practice, we use the fifth-order open composite Simpson’s rule, which is the fifth-order composite open Newton–Cotes method, and require the integrand to have a bounded fourth derivative. Therefore, when implementing the FCRK method, we apply (2.6) with  . When evaluating the numerical approximation of the convolution integral (2.5), we avoid the mesh points

. When evaluating the numerical approximation of the convolution integral (2.5), we avoid the mesh points  where the interpolant is continuous but not differentiable by ensuring these points are in the integration mesh. Finally, it is known that solutions of DDEs typically have discontinuous derivatives at breaking points. However, when considering a distributed DDE such as (1.1), we can leverage the additional smoothing offered by the convolution integral and only must ensure that

where the interpolant is continuous but not differentiable by ensuring these points are in the integration mesh. Finally, it is known that solutions of DDEs typically have discontinuous derivatives at breaking points. However, when considering a distributed DDE such as (1.1), we can leverage the additional smoothing offered by the convolution integral and only must ensure that  is in the integration mesh at each time point (Eremin et al., 2020).

is in the integration mesh at each time point (Eremin et al., 2020).

After the change of integration variable, with  and

and  chosen as in (2.6), solving the IVP (1.1) is equivalent to solving

chosen as in (2.6), solving the IVP (1.1) is equivalent to solving

|

(2.7) |

We recall that  depends explicitly on the solution

depends explicitly on the solution  through the definition (2.5). Finally, while we only consider fixed time step FCRK methods in this work, using variable time step methods on the reformulated IVP (2.7) is possible.

through the definition (2.5). Finally, while we only consider fixed time step FCRK methods in this work, using variable time step methods on the reformulated IVP (2.7) is possible.

Then, to simulate (2.7) using an FCRK method, we must numerically evaluate the convolution integral

|

(2.8) |

where we note that the integrand is depends explicitly on the solution of (2.7).

2.1.1 Quadrature rules and order conditions

As we are developing an FCRK method to numerically integrate (2.7), we will not evaluate the transformed convolution integral (2.8) exactly. Rather, as mentioned, we will use a quadrature method to numerically evaluate the integral to sufficient accuracy to maintain the global order of the FCRK method. Specifically, we consider an FCRK method of global order  so that the interpolant (2.1) is accurate to order

so that the interpolant (2.1) is accurate to order  on each stage. We thus have

on each stage. We thus have

|

Therefore, if we were to calculate the convolution integral (2.8) exactly, then we would evaluate the right-hand side of (2.7) to order  . In each RK stage, the evaluations of

. In each RK stage, the evaluations of  occur within the calculation of

occur within the calculation of  , so we gain an extra order of accuracy via the multiplication by

, so we gain an extra order of accuracy via the multiplication by  in (2.2). Then, the local error in each step of the numerical method has order

in (2.2). Then, the local error in each step of the numerical method has order  as required, with the extra order coming from the multiplication by

as required, with the extra order coming from the multiplication by  .

.

However, in practice, we cannot evaluate the convolution integral (2.8) exactly, and nor would we want to do so. Indeed, as the numerical solution  is only a

is only a  -th order approximation of the true solution

-th order approximation of the true solution  , it is not computationally efficient to evaluate the convolution integral

, it is not computationally efficient to evaluate the convolution integral  to extreme precision. Thus, the numerical integration should be sufficiently accurate to preserve the global order of the method, but not so accurate as to be computationally inefficient. To illustrate this idea, assume that we evaluate the integral (2.8) to order

to extreme precision. Thus, the numerical integration should be sufficiently accurate to preserve the global order of the method, but not so accurate as to be computationally inefficient. To illustrate this idea, assume that we evaluate the integral (2.8) to order  using a composite quadrature method with stepsize

using a composite quadrature method with stepsize  , so

, so

|

where  denotes the quadrature approximation of the convolution integral. Now, consider an FCRK method of order

denotes the quadrature approximation of the convolution integral. Now, consider an FCRK method of order  with coefficients

with coefficients  and stepsize

and stepsize  . Using Taylor’s theorem, we see that

. Using Taylor’s theorem, we see that

|

where  is the partial derivative of

is the partial derivative of  with respect to the second variable. Therefore, the first stage step

with respect to the second variable. Therefore, the first stage step  is calculated with the same accuracy as the numerical integration. We can thus proceed inductively to calculate each

is calculated with the same accuracy as the numerical integration. We can thus proceed inductively to calculate each  and

and  with accuracy

with accuracy  . Accordingly, for the continuous approximation

. Accordingly, for the continuous approximation  of the solution

of the solution  , equation (2.2) gives

, equation (2.2) gives

|

Thus, if  for some constant

for some constant  , then

, then  . Therefore, the condition

. Therefore, the condition  ensures that we do neither decrease the accuracy of the scheme nor perform extra computations when numerically integrating (2.8) using a

ensures that we do neither decrease the accuracy of the scheme nor perform extra computations when numerically integrating (2.8) using a  th order quadrature rule.

th order quadrature rule.

Finally, we note that the integrand in (2.8) is not defined at  . Accordingly, we use an open quadrature method so that the end points of the domain of integration,

. Accordingly, we use an open quadrature method so that the end points of the domain of integration,  and

and  , are not included. In particular, we use the composite Simpson’s open rule for which the base method is given by

, are not included. In particular, we use the composite Simpson’s open rule for which the base method is given by

|

where  . We note that the integrand of (2.8) must be sufficiently smooth inside each integration sub-interval to ensure the composite order. As previously mentioned,

. We note that the integrand of (2.8) must be sufficiently smooth inside each integration sub-interval to ensure the composite order. As previously mentioned,  is a potential breaking point of the distributed DDE. Therefore, we must enforce that

is a potential breaking point of the distributed DDE. Therefore, we must enforce that  is as an end-point of one of the sub-intervals at each step

is as an end-point of one of the sub-intervals at each step  by including

by including

|

in the quadrature mesh. Furthermore, since  is only

is only  at the mesh points

at the mesh points  preceding the current step

preceding the current step  , we include the transformed mesh points

, we include the transformed mesh points  in the integration mesh. These points may not be evenly spaced in

in the integration mesh. These points may not be evenly spaced in  , and so, the composite Simpson’s open rule does not use a uniform step size

, and so, the composite Simpson’s open rule does not use a uniform step size  to partition

to partition  . To ensure the global accuracy of the FCRK method, it is sufficient to divide

. To ensure the global accuracy of the FCRK method, it is sufficient to divide  into sub-intervals of maximal length

into sub-intervals of maximal length  . The composite quadrature rule therefore has error

. The composite quadrature rule therefore has error  and is sufficiently accurate to maintain the global error of the fourth-order FCRK methods considered here. Indeed, we utilize results from Bellen et al. (2009); Maset et al. (2005) to prove the following result in Appendix C

and is sufficiently accurate to maintain the global error of the fourth-order FCRK methods considered here. Indeed, we utilize results from Bellen et al. (2009); Maset et al. (2005) to prove the following result in Appendix C

Theorem 2.1. Global order of the FCRK method —

Assume that the right-hand side of (1.1) is 4 times continuously differentiable and let

be the explicit FCRK method with global fourth order defined in (2.4). Furthermore, let the simulation mesh include all breaking points of the DDE (1.1) and have maximal stepsize

, and calculate the convolution integral

using the composite Simpson’s open rule with maximal sub-interval size of

. Then, the FCRK method has global order 4.

3. ODE approximations

In Section 2, we developed a numerical method to solve the distributed DDE (1.1). As mentioned, numerical methods for distributed DDEs are computationally demanding, complicated and as a result, not available in most off-the-shelf scientific software packages. Therefore, we discuss a common method by which modellers avoid these difficulties via an Erlang approximation of (1.1) before deriving a new phase-type approximation of (1.1).

3.1 Erlang approximation

In many modelling applications, it is common to avoid the difficulties in simulating (1.1) by enforcing that  . As previously mentioned, the case

. As previously mentioned, the case  corresponds to

corresponds to  , where

, where  and

and  are the mean and variance of the underlying gamma distribution. As

are the mean and variance of the underlying gamma distribution. As  being an integer multiple of

being an integer multiple of  is not generic, it is common to round

is not generic, it is common to round  to the nearest integer

to the nearest integer  and then set the rate parameter

and then set the rate parameter  . This approximation allows modellers to replace the gamma distributed delay with an Erlang distribution and thus approximate (1.1) by the Erlang distributed DDE

. This approximation allows modellers to replace the gamma distributed delay with an Erlang distribution and thus approximate (1.1) by the Erlang distributed DDE

|

(3.1) |

The Erlang-distributed random variable  with shape and rate parameters

with shape and rate parameters  and

and  , respectively, has precisely the same mean

, respectively, has precisely the same mean  as the random variable in (1.1), but not the same variance. Then, it is a simple application of the linear chain technique—where the convolution integral is written as the solution to a system of differential equations—to obtain the equivalent ODE formulation to (3.1)

as the random variable in (1.1), but not the same variance. Then, it is a simple application of the linear chain technique—where the convolution integral is written as the solution to a system of differential equations—to obtain the equivalent ODE formulation to (3.1)

|

(3.2) |

3.2 Hypoexponenetial approximations

The approximation involved in the linear chain technique described previously replaces the gamma-distributed convolution integral with an Erlang distributed convolution integral parameterized to match the first moment of the original gamma distribution. Here, we develop an improved approximation technique to approximate the gamma-distributed DDE (1.1) by constructing a random variable  with corresponding probability measure

with corresponding probability measure  that matches the first two moments of the original gamma distribution and considering the corresponding distributed DDE

that matches the first two moments of the original gamma distribution and considering the corresponding distributed DDE

|

(3.3) |

We construct  such that it represents the concatenation of exponentially distributed random variables, so it is a phase-type distribution, and we show that (3.3) admits a finite dimensional representation. We then derive the equivalent ODE formulation to (3.3) and show that this approximation is more accurate than the approximation in (3.1). There are infinitely many such random variables

such that it represents the concatenation of exponentially distributed random variables, so it is a phase-type distribution, and we show that (3.3) admits a finite dimensional representation. We then derive the equivalent ODE formulation to (3.3) and show that this approximation is more accurate than the approximation in (3.1). There are infinitely many such random variables  and we consider two specific cases. We discuss the benefits of each approximation in Section 3.4.

and we consider two specific cases. We discuss the benefits of each approximation in Section 3.4.

3.2.1 The fixed hypoexponential approximation

We begin by deriving the rates of the exponentially distributed random variables whose concatenation is the random variable  , where

, where  is the concatenation of an Erlang distribution with two exponential distributions. We parametrize the Erlang distribution so that the rates of the Erlang distribution are fixed as the fractional part of

is the concatenation of an Erlang distribution with two exponential distributions. We parametrize the Erlang distribution so that the rates of the Erlang distribution are fixed as the fractional part of  varies. Accordingly, we refer to this approximation as the fixed hypoexponential approximation, with corresponding random probability measure

varies. Accordingly, we refer to this approximation as the fixed hypoexponential approximation, with corresponding random probability measure  .

.

Theorem 3.1.

Consider the gamma distributed random variable

with shape parameter

, mean

and variance

. Let

be the random variable obtained by concatenating

independent and exponentially distributed variables where

of these exponentially distributed random variables have identical rates

while the remaining two exponentially distributed variables have rates

and

. Then, setting

and

ensures that

and

have the same first two moments.

Proof.

The moment generating function (MGF)

of the random variable

is given by

The mean

and variance

of

are therefore

Recalling that

and setting

and

, gives

From this,

must solve

By symmetry,

must be the other root of this polynomial. Hence, we obtain

which ensures that the random variable

matches the first two moments of the gamma distribution.

When  , the square roots in the definition of

, the square roots in the definition of  and

and  vanish identically, leading to the following Corollary.

vanish identically, leading to the following Corollary.

Corollary 3.1.

If the gamma-distributed random variable

has integer shape parameter

, then the random variable

defined in Theorem 3.1 is also Erlang distributed and

for

.

3.2.2 A smoothed hypoexponential approximation

The parametrization of the hypoexponential distribution in Theorem 3.1 is determined by the choice of  and is therefore not unique. Here, we derive a slightly different parameterization of the hypoexponential approximation. This alternative approximation has benefits and a disadvantage compared with the fixed hypoexponential approximation, which we discuss below.

and is therefore not unique. Here, we derive a slightly different parameterization of the hypoexponential approximation. This alternative approximation has benefits and a disadvantage compared with the fixed hypoexponential approximation, which we discuss below.

Again, denote the mean of the gamma-distributed random variable  by

by  and let

and let  denote the shape parameter. Now we define a second hypoexponentially distributed random variable

denote the shape parameter. Now we define a second hypoexponentially distributed random variable  with the same mean and variance as

with the same mean and variance as  . We once again use a concatenation of an Erlang distribution with two exponential distributions. Here, unlike the fixed approximation described in Theorem 3.1, the rate of the Erlang distribution varies continuously as the fractional part of

. We once again use a concatenation of an Erlang distribution with two exponential distributions. Here, unlike the fixed approximation described in Theorem 3.1, the rate of the Erlang distribution varies continuously as the fractional part of  changes. We therefore refer to this approximation as the smoothed hypoexponential approximation, with corresponding probability measure

changes. We therefore refer to this approximation as the smoothed hypoexponential approximation, with corresponding probability measure  .

.

Theorem 3.2.

Let

be a

-distributed random variable where

. Consider the hypoexponentially distributed random variable

with rate parameters

. Recalling that

as

, set

, and define

and

by

(3.4) If

, then we define

. Then,

and

have the first two moments.

The proof of Theorem 3.2 is similar to the proof of Theorem 3.1 and is given in Appendix B. We note that we use the term smooth when describing the smoothed hypoexpoential approximation of  to refer to the continuous dependence of

to refer to the continuous dependence of  on

on  and not in the infinitely differentiable sense. Once again, if

and not in the infinitely differentiable sense. Once again, if  is an integer, it follows from the definition that the smoothed hypoexponential approximation is exact.

is an integer, it follows from the definition that the smoothed hypoexponential approximation is exact.

3.3 ODE representation of the hypoexponential DDE

The random variables  and

and  as defined in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2 correspond to the concatenation or addition of

as defined in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2 correspond to the concatenation or addition of  exponentially distributed random variables. As the derivation that follows is identical for the smoothed and fixed approximations, we drop the indices

exponentially distributed random variables. As the derivation that follows is identical for the smoothed and fixed approximations, we drop the indices  and

and  . The PDF of the hypoexponential distributions is obtained by convolving the PDFs of an Erlang distributed random variable with rate

. The PDF of the hypoexponential distributions is obtained by convolving the PDFs of an Erlang distributed random variable with rate  and shape parameter

and shape parameter  , and the two exponentially distributed random variables with respective rates

, and the two exponentially distributed random variables with respective rates  and

and  , where the rates are given explicitly in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2. The exponential distributions have respective PDFs

, where the rates are given explicitly in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2. The exponential distributions have respective PDFs  and

and  . Then, the delayed term in (3.3) is given by the convolution integral

. Then, the delayed term in (3.3) is given by the convolution integral

|

where  . The convolution integral

. The convolution integral

|

will satisfy a system of  ODEs in a similar manner to the linear chain technique (Cassidy, 2021; Diekmann et al., 2018, 2020a). To show that this is indeed the case, we introduce

ODEs in a similar manner to the linear chain technique (Cassidy, 2021; Diekmann et al., 2018, 2020a). To show that this is indeed the case, we introduce  auxiliary variables

auxiliary variables  satisfying

satisfying

|

with initial conditions

|

and

|

Then, using the linear chain technique on the Erlang-distributed variables  for

for  , we see

, we see

|

Then, an application of the main result in (Cassidy, 2021) shows that

|

It follows from the associativity of convolution that

|

Therefore, the distributed DDE (3.3) is equivalent to the  dimensional system of ODEs

dimensional system of ODEs

|

(3.5) |

where the rates  and

and  are taken from the fixed or smooth hypoexponential approximation.

are taken from the fixed or smooth hypoexponential approximation.

3.4 A comparison between fixed and smooth hypoexponential approximations

The rates  and

and  determine the expected residence time in the

determine the expected residence time in the  st and

st and  th compartments. Now, if these rates were to grow arbitrarily large, then the expected residence time would become arbitrarily small and the system of differential equations would become stiff. Furthermore, the dynamical system obtained from the gamma-distributed DDE has interesting behaviour as a function of the shape parameter

th compartments. Now, if these rates were to grow arbitrarily large, then the expected residence time would become arbitrarily small and the system of differential equations would become stiff. Furthermore, the dynamical system obtained from the gamma-distributed DDE has interesting behaviour as a function of the shape parameter  . For

. For  we expect the gamma-distributed DDE to define an infinite dimensional dynamical system. However, when

we expect the gamma-distributed DDE to define an infinite dimensional dynamical system. However, when  the gamma-distributed DDE can be reduced to a finite dimensional system of ODEs through the linear chain technique as detailed in Section 3.1. Assuming continuous dependence of dynamics on the parameter

the gamma-distributed DDE can be reduced to a finite dimensional system of ODEs through the linear chain technique as detailed in Section 3.1. Assuming continuous dependence of dynamics on the parameter  , as

, as  the gamma-distributed DDE approaches a transit compartment model with

the gamma-distributed DDE approaches a transit compartment model with  compartments. However, both the fixed and smoothed approximations are equivalent to transit compartment models with

compartments. However, both the fixed and smoothed approximations are equivalent to transit compartment models with  compartments. Thus, it is possible that the residence time in the final compartment becomes arbitrarily small so that the extra compartment in the hypoexponential approximation is negligible at the cost of the ODE system becoming stiff.

compartments. Thus, it is possible that the residence time in the final compartment becomes arbitrarily small so that the extra compartment in the hypoexponential approximation is negligible at the cost of the ODE system becoming stiff.

To formalize this argument, consider the limit of  and the fixed hypoexponential distribution. Then,

and the fixed hypoexponential distribution. Then,  and

and  must simultaneously satisfy

must simultaneously satisfy

|

which is only possible if  It is simple to show that, if

It is simple to show that, if  the rates

the rates  and

and  are bounded from above so that this stiffness only occurs when

are bounded from above so that this stiffness only occurs when  for the fixed hypoexponential distribution.

for the fixed hypoexponential distribution.

Now, consider the smoothed approximation and  for each integer

for each integer  . We immediately see that the rate

. We immediately see that the rate  can become arbitrary large in the limit, and the system of ODEs becomes stiff. In addition, as

can become arbitrary large in the limit, and the system of ODEs becomes stiff. In addition, as  , the argument of the square roots

, the argument of the square roots  in (3.4) approaches

in (3.4) approaches  , and the derivative of

, and the derivative of  becomes arbitrarily large as

becomes arbitrarily large as  . This is problematic for optimization methods that require the gradient of the objective function. To circumvent these singularities in the smooth hypoexponential approximation, we slightly modify (3.4) by replacing

. This is problematic for optimization methods that require the gradient of the objective function. To circumvent these singularities in the smooth hypoexponential approximation, we slightly modify (3.4) by replacing  and

and  by

by  and

and  , defined by

, defined by

|

where  is a small constant. By choosing

is a small constant. By choosing  , the practitioner can now trade-off the size of the discontinuities of the objective function at integer values of

, the practitioner can now trade-off the size of the discontinuities of the objective function at integer values of  , with the level of stiffness of the resulting ODEs. As we will see in Section 5, for statistical inference, one often needs to optimize an objective function which depends on the solution of a DDE (1.1) at certain time points

, with the level of stiffness of the resulting ODEs. As we will see in Section 5, for statistical inference, one often needs to optimize an objective function which depends on the solution of a DDE (1.1) at certain time points  . For many optimization algorithms, it helps if the objective function depends smoothly on the model parameters, including

. For many optimization algorithms, it helps if the objective function depends smoothly on the model parameters, including  , and so using the smoothed hypoexponential in these scenarios may be advantageous.

, and so using the smoothed hypoexponential in these scenarios may be advantageous.

Furthermore, we note that the approximations in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2 are approximations of the semi-infinite convolution integral in (1.1). To compare the hypoexponential approximations against the true gamma distribution, we first consider the survival function of the gamma distribution with mean  and shape parameter

and shape parameter  which is given by

which is given by

|

We also compute the survival functions corresponding to the fixed and smoothed hypoexponential approximations of the gamma distribution with mean  and shape parameter

and shape parameter

|

(3.6) |

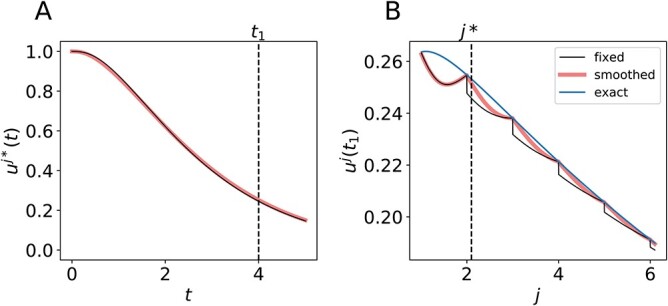

We plot  and

and  in Fig. 1 to illustrate the difference between the fixed and smoothed hypoexponential approximations. We do not present

in Fig. 1 to illustrate the difference between the fixed and smoothed hypoexponential approximations. We do not present  as it overlaps the two approximations. Furthermore, for fixed

as it overlaps the two approximations. Furthermore, for fixed  it is possible to view

it is possible to view  and

and  as functions of

as functions of  . In Fig. 1 (B), we show this function for both approximations and the exact solution. For the fixed hypoexponential approximation (derived in Theorem 3.1)

. In Fig. 1 (B), we show this function for both approximations and the exact solution. For the fixed hypoexponential approximation (derived in Theorem 3.1)  , we generally lose continuous dependence on the parameter

, we generally lose continuous dependence on the parameter  at integer values as the rates of the Erlang distribution

at integer values as the rates of the Erlang distribution  do not vary continuously but rather jump as

do not vary continuously but rather jump as  crosses each integer. However, using the smoothed hypoexponential parameterization, the rates

crosses each integer. However, using the smoothed hypoexponential parameterization, the rates  vary continuously with

vary continuously with  which appears to reduce the size of jumps at integer values of

which appears to reduce the size of jumps at integer values of  . However, an analytical study of these jumps is beyond the scope of the current work.

. However, an analytical study of these jumps is beyond the scope of the current work.

Fig. 1.

Trajectory dependence on the shape parameter  is not smooth. (A) The trajectory

is not smooth. (A) The trajectory  and

and  for

for  calculated with the fixed (black) and smoothed (red) hypoexponential approximations in (3.6). The exact solution

calculated with the fixed (black) and smoothed (red) hypoexponential approximations in (3.6). The exact solution  is not shown as it overlaps with the two curves. (B) The graph of

is not shown as it overlaps with the two curves. (B) The graph of  with

with  , using the fixed (black) and smoothed (red) parameterizations of the hypoexponential approximation, and the exact solution (blue).

, using the fixed (black) and smoothed (red) parameterizations of the hypoexponential approximation, and the exact solution (blue).

3.5 Approximation error estimates

The natural phase space for distributed DDEs such as (1.1) or (3.3) is the space of exponentially weighted functions  (Cassidy, 2021; Diekmann & Gyllenberg, 2012). In general, solutions evolving from the space of

(Cassidy, 2021; Diekmann & Gyllenberg, 2012). In general, solutions evolving from the space of  measurable functions remain integrable with respect to

measurable functions remain integrable with respect to  (Cassidy & Humphries, 2019; Hale, 1974).

(Cassidy & Humphries, 2019; Hale, 1974).

Now, for the rate parameter of the gamma distribution given by  , solutions of the gamma-distributed DDE will satisfy the growth bound in (1.2) with

, solutions of the gamma-distributed DDE will satisfy the growth bound in (1.2) with  . Furthermore, solutions

. Furthermore, solutions  of linear gamma-distributed DDE (1.1) are of the form

of linear gamma-distributed DDE (1.1) are of the form  with

with  . To illustrate the increased accuracy offered by the hypoexponential approximation, we use this linear case to derive explicit bounds for the approximation error induced by replacing the gamma distribution in (1.1) by an Erlang distribution as in (3.1) or by the hypoexponential approximation in (3.3). In both cases, we will express the approximation error as the difference of the MGFs evaluated at

. To illustrate the increased accuracy offered by the hypoexponential approximation, we use this linear case to derive explicit bounds for the approximation error induced by replacing the gamma distribution in (1.1) by an Erlang distribution as in (3.1) or by the hypoexponential approximation in (3.3). In both cases, we will express the approximation error as the difference of the MGFs evaluated at  and we will see that the hypoexponential approximation has one fewer term than the Erlang approximation.

and we will see that the hypoexponential approximation has one fewer term than the Erlang approximation.

3.5.1 Erlang-distributed DDE

In the Erlang approximation described in Section 3.1, we approximated the convolution integral in the gamma-distributed DDE

|

where  is the rate of the approximating Erlang distribution, and the Erlang-distributed DDE (3.1) is otherwise identical to (1.1). Thus, to compute the error induced by this approximation, we consider the difference between the convolution integrals where

is the rate of the approximating Erlang distribution, and the Erlang-distributed DDE (3.1) is otherwise identical to (1.1). Thus, to compute the error induced by this approximation, we consider the difference between the convolution integrals where

|

We immediately obtain

|

where the MGF of the gamma-distributed random variable is given by

|

and  is the MGF of the Erlang distribution

is the MGF of the Erlang distribution

|

Then,

|

(3.7) |

Using the binomial theorem and the fact that the Erlang distribution is parameterized so that the first moment matches that of the gamma distribution, we can write the numerator in (3.7) as

|

Thus, the approximation error in the Erlang approximation case (see Section 3.1) is order  . We see from the above analysis that if

. We see from the above analysis that if  , then (3.7) is identically 0 and the approximation is exact.

, then (3.7) is identically 0 and the approximation is exact.

3.5.2 Hypoexponential approximations

Turning to the two moment approximations derived in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2, we see that the approximation error induced by integrating with respect to the random variable  is given by

is given by

|

Then, we obtain

|

(3.8) |

where  is the MGF of the random variable

is the MGF of the random variable  and is given by

and is given by

|

Then, we see

|

(3.9) |

By recalling that  and the fact that the first two moments agree, we use the binomial theorem to write the numerator in (3.9) as

and the fact that the first two moments agree, we use the binomial theorem to write the numerator in (3.9) as

|

Now, recalling that  and

and  , we have

, we have

|

Thus, as  and

and  are entirely determined by the mean and variance of the gamma distribution, we can write the error (3.8) as

are entirely determined by the mean and variance of the gamma distribution, we can write the error (3.8) as

|

where  Accordingly, we see that the approximation error is order

Accordingly, we see that the approximation error is order  , or one order better than the Erlang-distributed DDE approximation. We also see that for

, or one order better than the Erlang-distributed DDE approximation. We also see that for  as

as  as in Section 3.2,

as in Section 3.2,  so (3.9) is identically 0, and the approximation is exact.

so (3.9) is identically 0, and the approximation is exact.

3.6 On three moment matching

The ODE approximations in this section aim to replicate the gamma-distributed DDE by matching the first (in the case of the Erlang approximation) or first and second moments (in the hypoexponential approximations) of the underlying gamma distribution. It is natural to ask if a similar technique could allow for a more accurate approximation by matching the first three moments. To address this question, it is simpler and equivalent to match first three cumulants, rather than moments, of gamma and hypoexponential. The cumulant generating function of a gamma-distributed random variable  with shape and rate parameters

with shape and rate parameters  and

and  is given by

is given by

|

Therefore, the cumulants  are

are

|

Conversely, the cumulant generating function of hypoexponential-distributed random variable  is given by

is given by

|

Therefore, the cumulants of  are given by

are given by

|

Now, we show that if a hypoexponential distribution matches the first three cumulants, and thus moments, of  then

then  .

.

Theorem 3.3.

Let

be a gamma-distributed random variable and assume that

such that

for

. Then,

.

Proof.

Without loss of generality by scaling, we take

. Write

, so that

. The following system of equations for the first three cumulants must hold

Now, consider the sum

. We have

and therefore

As all terms of

are non-negative, we must have

for all

. As

, we obtain

for all

. It follows that

and

.

We therefore conclude that it is not possible to match the first three moments of a generic gamma distribution using a hypoexponential approximation. This three moment matching problem has been extensively studied (Bobbio et al., 2005; Osogami & Harchol-Balter, 2006). A generalized hypoexponential random variable corresponding to a Markov chain where each stage is visited at most once, i.e. the linear chain flows in one direction but some stages can be skipped, can be used to match the first three moments of gamma-distributed random variable. However, these generalized hypoexponential random variables are more demanding to implement than the hypoexponential approximations derived in Theorems 3.1 and 3.2. In short, their output varies depending on normalized moments, require at least as many parameters as the hypoexponential approximations, and the non-zero probability of skipping stages does not allow for a simple skip-free Markov chain interpretation as in the hypoexponential approximation.

4. Numerical results

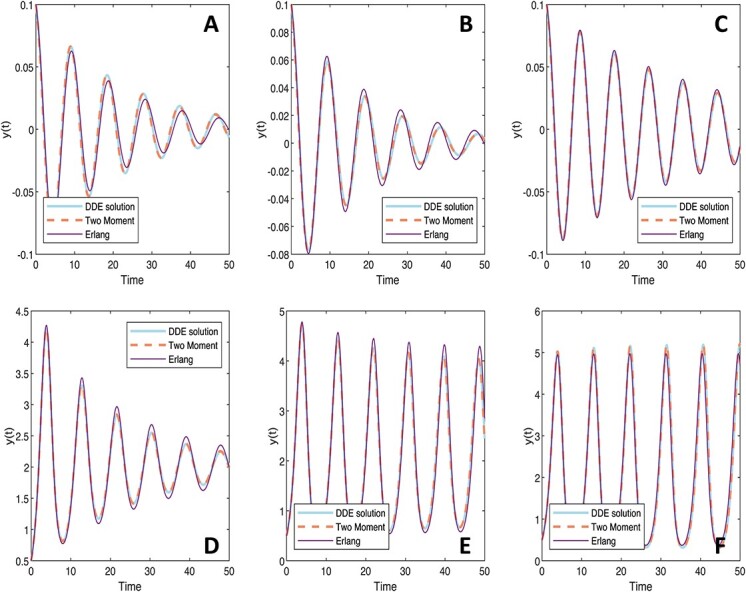

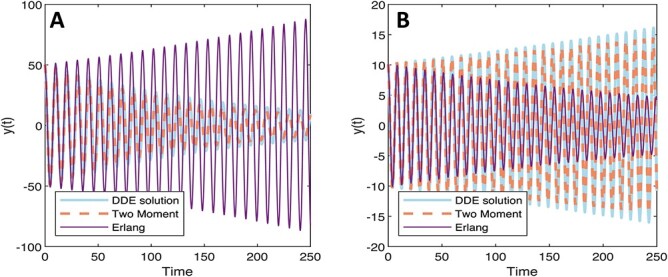

Here, we illustrate the analytical results of Section 2 and evaluate the hypoexponential approximations derived in Section 3.2 by comparing the direct simulation of (1.1) using the FCRK method in Section 2 against the numerical simulation of the approximate ODE (3.3) and the Erlang distributed DDE (3.1). We first show that the FCRK method for (1.1) is accurate to the order demonstrated in Theorem 2.1. We then test the accuracy of the hypoexponential approximation derived in Section 3.2 using our FCRK method to provide reference solutions of generic gamma-distributed DDEs.

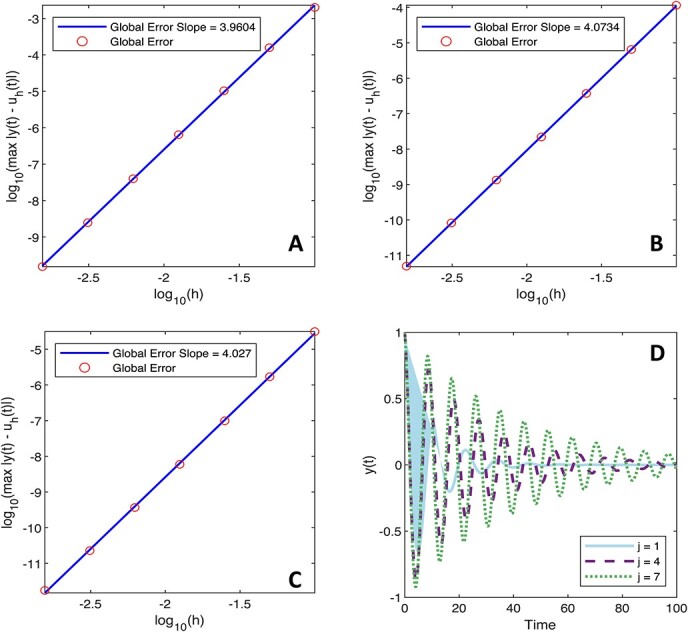

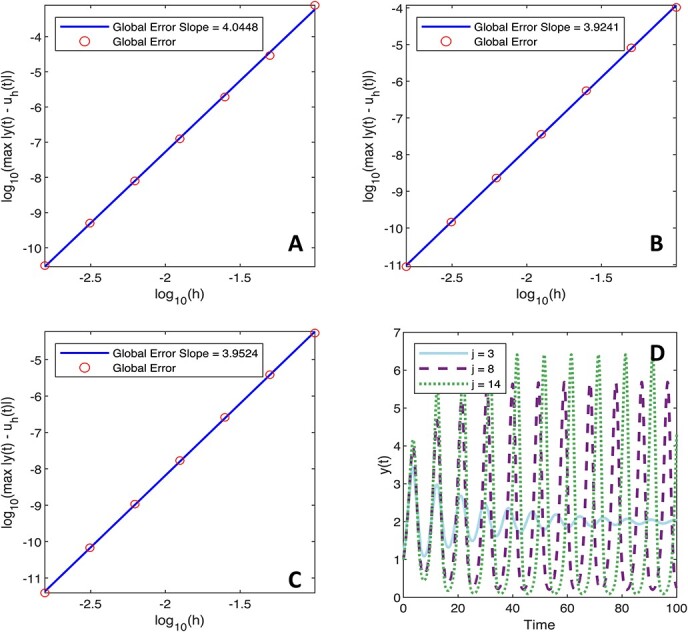

4.1 Numerical verification of the FCRK method

We test the fourth-order FCRK numerical solver by comparing the output of the FCRK method for (1.1) against differential equations with known, or reference, solutions. To obtain these known solutions, we first consider (1.1) in the case where the shape parameter  is an integer. The gamma distribution in (1.1) is thus an Erlang distribution so, using the linear chain technique, we derive an equivalent ODE formulation. This equivalent ODE formulation can either be solved analytically or simulated using established techniques for systems of ODEs as implemented in Matlab to give the reference solution

is an integer. The gamma distribution in (1.1) is thus an Erlang distribution so, using the linear chain technique, we derive an equivalent ODE formulation. This equivalent ODE formulation can either be solved analytically or simulated using established techniques for systems of ODEs as implemented in Matlab to give the reference solution  .

.

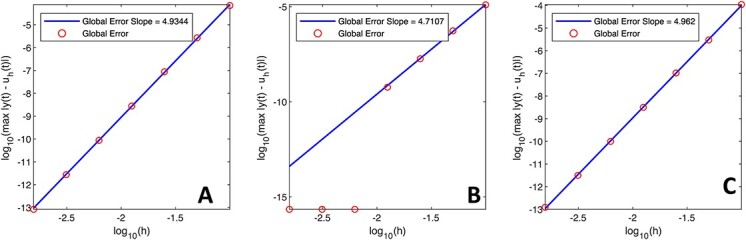

We simulate the Erlang-distributed DDE (1.1) using our fourth-order FCRK method to compute the numerical solution  for a given step size

for a given step size  . Then, to compute the accuracy of our simulation, we compute the

. Then, to compute the accuracy of our simulation, we compute the  error between the solution of (1.1), as obtained using our FCRK method, and the reference solution, obtained via the equivalent ODE. In general, when using a

error between the solution of (1.1), as obtained using our FCRK method, and the reference solution, obtained via the equivalent ODE. In general, when using a  th order FCRK method, the error between the numerical solution,

th order FCRK method, the error between the numerical solution,  and the reference solution,

and the reference solution,  , satisfies

, satisfies

|

where  is the stepsize of the FCRK method. The error

is the stepsize of the FCRK method. The error  then satisfies

then satisfies

|

Therefore, we consider the error  as a function of the step size

as a function of the step size  of the FCRK method and thus compute

of the FCRK method and thus compute  for a various values of

for a various values of  . The slope of

. The slope of  as a function of

as a function of  is the order

is the order  of the FCRK method.

of the FCRK method.

4.1.1 Linear test problem

We first consider the linear test problem

|

(4.1) |

where we set  , and choose

, and choose  so the mean delay time

so the mean delay time  . In this case, we can use the linear chain technique to reduce the Erlang distributed DDE in (4.1) to

. In this case, we can use the linear chain technique to reduce the Erlang distributed DDE in (4.1) to

|

(4.2) |

where

|

Equation (4.2) is a linear system of ODEs and has an exact solution given by matrix exponentials. For  , the analytical solution is

, the analytical solution is

|

Thus, we simulate (4.1) using the fourth-order FCRK method described in the preceding section for  and compare it against the analytic solution of (4.2) for

and compare it against the analytic solution of (4.2) for  on the interval

on the interval  . Furthermore, we simulate (4.1) for