Abstract

The aim of this work is the design and 3D printing of a new electrochemical sensor for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes based on loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). The food related diseases involve a serious health issue all over the world. Listeria monocytogenes is one of the major problems of contaminated food, this pathogen causes a disease called listeriosis with a high rate of hospitalization and mortality. Having a fast, sensitive and specific detection method for food quality control is a must in the food industry to avoid the presence of this pathogen in the food chain (raw materials, facilities and products). A point-of-care biosensor based in LAMP and electrochemical detection is one of the best options to detect the bacteria on site and in a very short period of time. With the numerical analysis of different geometries and flow rates during sample injection in order to avoid bubbles, an optimized design of the microfluidic biosensor chamber was selected for 3D-printing and experimental analysis.

For the electrochemical detection, a novel custom gold concentric-3-electrode consisting in a working electrode, reference electrode and a counter electrode was designed and placed in the bottom of the chamber. The LAMP reaction was optimized specifically for a primers set with a limit of detection of 1.25 pg of genomic DNA per reaction and 100% specific for detecting all 12 Listeria monocytogenes serotypes and no other Listeria species or food-related bacteria. The methylene blue redox-active molecule was tested as the electrochemical transducer and shown to be compatible with the LAMP reaction and very clearly distinguished negative from positive food samples when the reaction is measured at the end-point inside the biosensor.

Keywords: Loop-mediated isothermal AMPlification (LAMP), Listeria monocytogenes, Electrochemical detection, Biosensor, 3D printing, Numerical analysis

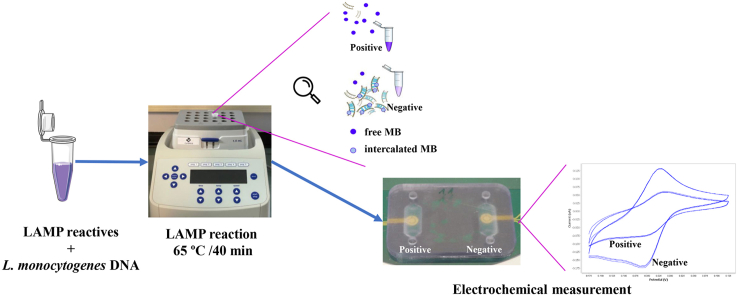

Graphical abstract

Loop-mediated isothermal AMPlification (LAMP); Listeria monocytogenes; Electrochemical detection; Biosensor; 3D printing; Numerical analysis.

1. Introduction

The food industry market has globalized so rapidly that there is an urgent need to improve the biological, chemical and physical monitoring of food quality control during all processes, from farm to fork. This trend in the industry raises the need to strengthen food safety by developing and implementing online quality control systems [1]. Biological hazards caused by bacteria, viruses and their toxins constitute one of the most serious risks to consumer health. The microorganisms responsible for the greatest economic losses in the food sector, due to claims and medical expenses are mainly Samonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter and Escherichia coli [2]. Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) has a high incidence and persistence in the food industry and is very difficult to eradicate and eliminate from equipment and facilities. The consumption of contaminated food with L. monocytogenes generates the disease known as listeriosis with a high rate of hospitalization (90%) and mortality (20–30%) [3]. The main difficulty for the eradication of this pathogen is its ability to generate biofilms [4] and to adapt to stress conditions.

Several biosensors for the detection of L. monocytogenes have been described so far [5] based on different transduction systems: optical, piezoelectric, amperometric and different recognition analytes such as antibodies or DNA. Antibody based biosensors rely on the antigen-antibody affinity and are generally much less sensitive than DNA-based biosensors [6]. Some DNA-based biosensors use DNA probes to detect the DNA target and are based on hybridization reactions, which are of high operational complexity, while other DNA biosensors are based on the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technique. The PCR method is the most extensively used nucleic acid amplification-based method for the pathogen detection in food quality control laboratories and agri-food industries [7]. However, its main drawback for incorporation into a sensor is the need for temperature cycling up to 95 °C, which makes sensor fabrication and stabilization difficult and complicates in situ measurements. For this reason, isothermal amplification methods have become a very suitable alternative to PCR because these methods avoid temperature cycling and the working temperature of the enzymes is always below 68 °C.

As a matter of that, one of the isothermal methods that is being most widely adapted to point of test systems is the Loop mediated isothermal AMPlification (LAMP) [8]. The LAMP method allows the amplification of nucleic acids at a single temperature, around 65 °C, in a closed tube that requires no intermediate steps for reagent addition and results are available in less than 30 min [9]. Amplified DNA can be detected by several methods like fluorescence [10], colorimetric [11] or electrochemical readout [12]. The use of LAMP for application in microfluidic solutions (microchips and microdevices) [13] allows, in addition to performing amplification at constant temperature, to reduce the manufacturing cost; for both test point devices and consumables, facilitates the operational steps for a user-friendly solution and increases the stability and quality of the assay.

Several LAMP reactions had been developed for the specific detection of L. monocytogenes. Wachiralurpan et al. developed a method for the detection of L. monocytogenes, they combined the LAMP reaction with a lateral flow dipstick (LAMP-LFD) for a rapid and visual detection method, they also tested their developed LAMP-LFD in chicken meat samples achieving a better sensitivity (90,2%) and accuracy (97.5%) than the PCR [14]. Ma et al., developed a LAMP reaction for detecting L. monocytogenes in fresh-cut fruits and vegetables [15], the detection method they used is based on the precipitation of the magnesium pyrophosphate that forms a white precipitate when the reaction occurs and gel electrophoresis is used to confirm the results. Although with their LAMP reaction can detect up to 1 CFU μL−1, the detection method is hardly scalable for on-site testing [15]. In addition, the drawback of these studies is that the opening of the tube after the end of the amplification reaction for DNA resolution by LFD or electrophoresis increases the risk of contamination between samples, and, therefore, increased false positive results. Cross-contamination of samples in the LAMP technique is a recurring problem that needs to be solved. High amplification efficiency and DNA products containing multiple inverted repeats make the LAMP reaction extremely vulnerable to false-positive amplification caused by environmental contaminations [16].

This combination between an isothermal amplification and an intercalating redox reporter presents very interesting advantages especially for Point-Of-Care (POC) devices, facilitating the needs of miniaturization, portability, low cost devices production and real-time determinations [7, 17, 18]. Hsieh et al. developed a microfluidic device to perform the LAMP amplification of Salmonella typhimurium and used MB as redox reporter [19]. Luo et al. expanded this work demonstrating the multiplexing capabilities of the technique for the simultaneous detection of various different bacterial genes [20]. Other interesting applications include the detection of Yersinia enterocolitica [21] or Salmonella spp. in food samples [8]. Comparable solutions have also been implemented in the food control domain, for example for the differentiation of meat species, using a sensor relying on the interaction between DNA and Hoechst33258 [22]. Furthermore, a similar approach was used for the detection of microRNA, using ruthenium hexamine as redox probe [23].

Most of the electrochemical reported biosensors are based on stereolithography printing (SLA) or Direct-Ink-Writing (DIW) [24, 25]. Mass production is limited and expensive because large number of different geometries must be tested to select the most optimal one. This factor increases the per-unit cost fabrication of sensors. In this manner, during the last few years, the use of additive manufacturing (3D printing) techniques has grown significantly in the field of microfluidics [26, 27, 28, 29]. As a versatile and more affordable technique, 3D is widely used for the development of new materials prototypes [30] that allows obtaining devices systems that include samples pre-treatment [31]. This technique highlights due to some of its advantages such as fast production, cost-effectiveness, and ability to obtain accurate and complex designs [32, 33]. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations have been used as an important tool to optimize biosensor chip design. CFD tools can help to predict the working scenario before starting the fabrication step [34].

Our DNA-based sensor has the advantage of integrating the electrochemical LAMP detection into a CFD designed 3D-printed microfluidic chip, which prevents contamination, reduces the cost, simplifies the measurement process and allows parallel determinations [35, 36].

This electrochemical sensor will provide a point-of-test solution for effective control of the pathogen throughout the food chain, from raw material to food product and thus, effectively prevent the spread of L. monocytogenes in facilities and provide with an efficient tool for food quality control.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and reagents

The extraction of total DNA from Listeria and non-Listeria strains was carried out with the Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit (ZYMO Research, US) and DNeasy PowerFood Microbial Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Nucleic acid concentration and quality was determined by measuring the optical density at 260/280 nm with a Nanodrop® ND 1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, US). For the LAMP amplification, the primer sets were designed based on the hly gene of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b (GeneBank accession number: MG922920.1). Sequences alignment was performed using Bioedit Sequence Alignment Editor (Bioedit version 7.0.5.3).

LAMP primers were synthesized by Biomers, Germany. LAMP mixture buffer for isothermal amplification contained ThermoPol buffer (10X), MgSO4, MgCl2, dNTPs, Bst DNA polymerase large fragment were purchased from New England Biolabs, UK and Maxima Reverse Transcriptase from Fisher Scientific, S.L. Calcein 5G, betaine and Methylene Blue (MB) were acquired from Sigma Aldrich, UK. Fluorescence emission was monitored with the Rotor-Gene Q 5plex HRM Platform (Qiagen, Germany). The Nutrient Agar plates for growth of Listeria and non-Listeria strains and the Maximum Recovery Diluent (MRD) were purchased from Oxoid, UK and the Listeria Special broth for the enrichment of food samples was acquired from Bio-Rad, EEUU. The Lenticule discs used for spiked food samples was acquired from Sigma Aldrich, UK.

Pressure-sensitive acrylic adhesive ARcare 93551 (Adhesives Research) was used for assembling the microfluidic chips. All the electrochemical measurements were performed using a STAT 400 potentiostat (Metrohm Dropsens, Spain).

The thermophysical properties of the LAMP mixtures were determined with Anton Paar DMA 5000 M vibrator type densitometer (Anton Paar, Austria) with U-form quartz tube sensor to measure the density of the fluids. The dynamic viscosity was analyzed with an AMVn microviscosimeter of falling ball principle (Anton Paar, Austria). For the determination of the refractive index, an Anton Paar Abbemat WR MW refractometer (Anton Paar, Austria) was used at 589.3 nm. Furthermore, the thermal conductivity and specific heat of the samples was determined with Thermtest TH1-L1 equipment (Thermtest, Canada). The surface tension was measured using a Sigma 700 Force Tensiometer (Biolin Scientific).

Later, the HARVARD PHD 2000 Infusion/Withdraw equipment (Harvard Apparatus, USA) was used for the experimental analysis to inject the sample into the fabricated chips made of transparent acrylic resin (SC 801 Clear; Phrozen). The pump has a high precision (0.35 %) that allows the injection of very low inlet flow rates (up to 1.7.10−12 m3 s−1). In addition, to simulate the working condition of a LAMP reaction (65 °C), the VWR VMS-C7 Advanced Magnetic Stirrer heater that can work in a temperature range from 0 °C to 200 °C was used.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preliminary design of microfluidic device

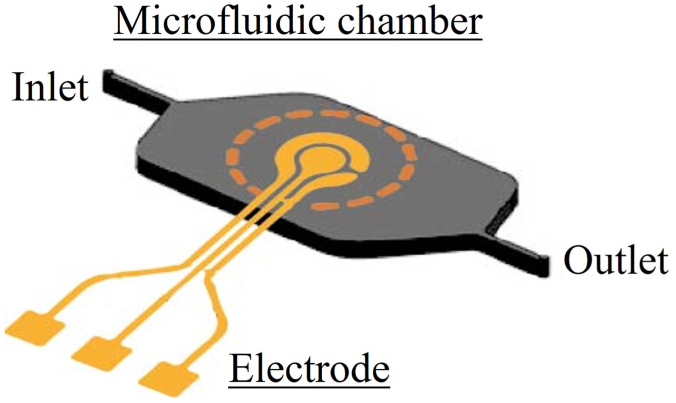

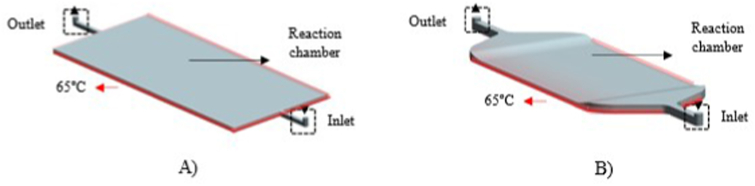

Figure 1 shows a schematic design of the chamber as well as the electrochemical sensor for the detection of L. monocytogenes. The initial design of the microfluidic device featured a bioreactor with initial dimensions of 5 mm × 0.6 mm x 9 mm (width × height × length). This initial design was optimized by numerical analysis considering the reaction buffer for LAMP amplification.

Figure 1.

Preliminary design of the microdevice.

2.2.2. Study of the physicochemical properties of the fluids

Before numerical study of the chip and the optimization of the design to be printed, it is crucial to define the thermophysical properties involved in the numerical simulations. In addition, optical properties such as refractive index allow the quantification of variations in reaction processes. Two solutions were analysed in this study; M1: consisting in ThermoPol reaction buffer Large 10X, MgSO4, 100mM, MB. 8 μg μL−1 and RNAse/DNAse free water and M2: with the components of sample M1 and Betaine, 5M. Betaine is an isostabilizing agent for DNA that eliminates composition dependence of DNA melting temperature, destabilizing the DNA duplex by reducing secondary structure of nucleic acids in the reaction [37]. Density, thermal expansion coefficient, dynamic viscosity, thermal conductivity, specific heat, refractive index, and surface tension of the two samples were comparatively studied. Considering that LAMP reaction occurs around 65 °C, all the properties were measured in a temperature range from 25 °C to 65 °C.

Regarding the experimental procedure, for each property to study, first, it was essential to calibrate all the equipment using bidistilled water as reference. As for the LAMP mixtures, three independent tests were carried out for each sample-property to be determined thus verifying that the experimental results were reliable. In addition, it was necessary to verify always that there were no bubbles in the equipment at the beginning of each experiment (after the filling process).

In the case of the thermal expansion coefficient (α), for each α value, the density at five different temperatures was measured, two below, two above and at operating temperature. For example, for a temperature of 25 °C, the density was determined from 24 °C to 26 °C (increase of 0.5 °C). Then, α was calculated by Eq. (1), where is the density of the fluid at the study temperature and refers to the slope of the obtained curve. The dynamic viscosity was studied at four different capillary angles (40-50-60-70°) and the average was calculated.

| (1) |

2.2.3. Numerical analysis

CFD simulations were carried out using ANSYS Fluent 2020 R2 software (Ansys® Fluent | Fluid Simulation Software, Release 20.2) to optimize and validate the final microfluidic design. For this application, the numerical analysis was an important tool used to predict-simulate experimental working conditions before starting the fabrication of microfluidic systems. Regarding numerical simulations, to date several works have been presented. In this context, both Errarte et al. and Sanjuan et al. numerically analysed the separation of different particle sizes in microfluidic channels predicting the optimal experimental working environment [38, 39].

Regarding the methodology followed, all CFD simulations can be divided into three general steps. First, the design of the microfluidic device to be analysed was carried out. Afterwards, the meshing of the geometric domain was performed. This consists of dividing the domain into different small cells to be studied since numerical simulations do the calculations for each cell in the domain. The third step was to run the simulations. In this section, the general thermohydrodynamic expressions of mass, momentum and energy conservation laws for an incompressible steady-state fluid were considered Eq. (2), Eq. (3), and Eq. (4). In addition, all the properties of the samples (measured before) to be studied were introduced together with the working conditions to be simulated.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where is the fluid velocity, is the sample density, is the kinematic viscosity and and correspond to the thermal conductivity and specific heat. and represent the temperature and pressure

In the case of LAMP reaction, the generation of bubbles in a microfluidic chip is a major issue, and can be caused by three different reasons, the air being introduced by sample loading, the evaporation of the water of the reaction mixes due to the high temperatures and the dissolve gas present in the reaction [40]. Bubbles can interfere with the electrodes, disrupting the electrochemical measurement. Avoiding bubble generation in the filling process and obtaining a homogeneous temperature distribution in the reaction chamber is crucial to achieve a suitable performance of the microfluidic sensor. Therefore, both were studied numerically to design the optimum electrochemical sensor. In the case of the evaporation of the water of the reaction mix, it was not necessary to study because in a LAMP reaction the temperature is below the boiling point of the water in contrast with the temperature of a PCR reaction.

2.2.4. Design and 3D-printing of microfluidic chip

The microfluidic devices were designed with Autodesk Fusion 360 software considering the results obtained from finite element analysis. Then, the design was sliced through Chitubox Slice Software, the software provided by the printer Phrozen. The microfluidic chip was fabricated via 3D printing based on SLA using digital light projection using a Phrozen Mini printer (Phrozen, Taiwan). The designed microfluidic device includes one inlet, one outlet and a reaction chamber where the detection electrode will be placed, being its dimension described in Section 3.2.

Microfluidic chips were fabricated with a commercial DLP-SLA 3D printing tool (Phrozen Mini, Phrozen, Taiwan) with a build volume of L120 x W68 x H130 mm. The DLP light engine with a light source of LEDs emits at 405 nm was selectively masked by a 1920 × 1080 LCD screen that provides a XY resolution of 62.5 μm. Printing was done with a commercial resin that enables high-resolution motives and adequate solvent resistance for the selected application. The design was divided in layers of 30 μm thickness, these layers were printed by 20 s of shutter speed. The prototype was printed parallel to the printing support, so that the resulting device will present the maximum possible transparency for the resin used.

After printing, the chip was cleaned in IPA bath to remove uncured resin from the channels. Finally, thermal post-cure process was carried out in a hydraulic press at 60 °C for 48 h to completely cure the chips. Fluid inlets to the printed channels were drilled, in order to adapt male mini Luer fluid connectors allowing direct connection of the chip to syringe pumps.

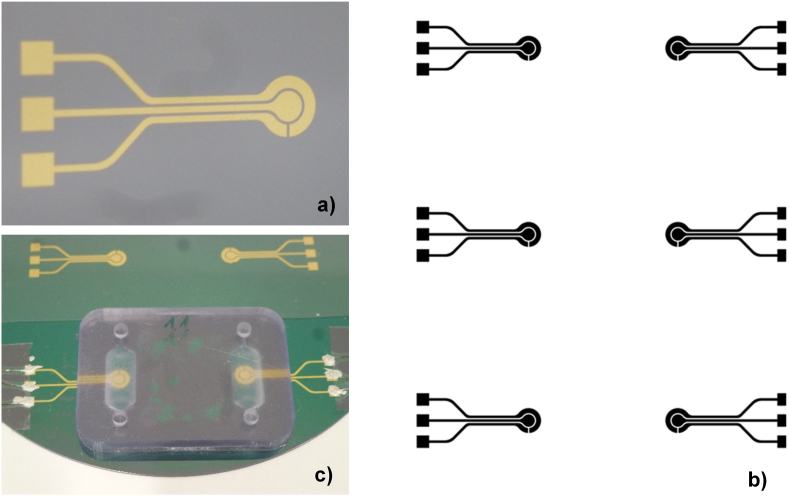

2.2.5. Electrode design and fabrication

A circular concentric 3-electrode design was chosen, with a 4mm2 central Working Electrode (WE) and a Reference Electrode (RE) and larger Counter Electrode (CE) in the perimeter of the WE (Figure 2a). The geometry and size of the electrodes constitutes a good balance between a minimization of sample volume and maximization of electrode area to improve the sensitivity of the measurements. The electrodes were developed on gold on 4” silicon oxide wafers. They were fabricated using standard photolithography by means of a EVG620 mask aligner and gold evaporation driven by an electron beam evaporator (AJA International Inc.) in vacuum. The process followed was the metal lift-off in acetone. Each wafer contained six electrode units, as shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

Gold electrodes unit fabricated by photolithography (a) on a 4″ silicon dioxide wafer (b). Each electrode unit comprises of a working electrode, a counter and a reference electrode.

Once the electrodes were fabricated, the microfluidic chips were assembled. First, an acrylic pressure-sensitive adhesive ARcare 93551 of 25μm were cut in a plotter using the STL archive. The sensor was assembled as shown in Figure 2c, sealed in a vacuum bag and cured at 60 °C for 24 h. Once the curing process was finished, copper wires were fixed to the electrodes by using a silver conductive paint (186–3600, RS).

2.2.6. Bacterial strains and nucleic acid extraction

For the specificity study performed by LAMP reaction, the list of inclusive and exclusive microorganisms is included in Table 1. All bacterial strains were acquired from the Spanish Type Culture Collection (Valencia, Spain) and were grown on the corresponding medium. Specifically, L. monocytogenes strains were grown on Nutrient Agar plates at 37 °C±1 °C in the presence of CO2 at 2.5 atm for 24h. Bacterial strains used as inclusive for the specificity study were microorganisms belonging to different serotypes of L. monocytogenes specie. The exclusive microorganisms tested, were species of the genus Listeria not belonging to the specie L. monocytogenes and also other bacteria commonly recovered in food products. L. monocytogenes serotype 4b is the cause of most clinical isolates in sporadic and outbreaks in humans [41]. For this reason, the serotype 4b (CECT 935) was established as the reference strain for this study.

Table 1.

Listeria and non-Listeria strains used for specificity study.

| Inclusive and exclusive bacteria | Number | Species | Strain(a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive: Listeria monocytogenes |

1 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 1 | CECT 7467 |

| 2 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 1/2a | CECT 5873 | |

| 3 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 1/2b | CECT 936 | |

| 4 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 1/2c | CECT 911 | |

| 5 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 1a | CECT 4031 | |

| 6 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 3a | CECT 933 | |

| 7 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 3b | CECT 937 | |

| 8 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 3c | CECT 938 | |

| 9 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 4a | CECT 934 | |

| 10 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 4b | CECT 935 | |

| 11 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 4c | CECT 5725 | |

| 12 | Listeria monocytogenes serb 4d | CECT 940 | |

| Exclusive: Other Listeria species/Non-Listeria species |

13 | Listeria seeligeri | CECT 941 |

| 14 | Listeria grayi | CECT 942 | |

| 15 | Listeria innocua | CECT 5377 | |

| 16 | Listeria innocua | CECT 5378 | |

| 17 | Listeria ivanovii | CECT 5368 | |

| 18 | Listeria seeligeri | CECT 5340 | |

| 19 | Listeria welshimeri | CECT 5380 | |

| 20 | Pseudomona aeuroginosa | CECT 116 | |

| 21 | Citrobacter freundii | CECT 401 | |

| 22 | Proteus vulgaris | CECT 4077 | |

| 23 | Salmonella typhimurium | CECT 4300 | |

| 24 | Enterococcus faecalis | CECT 184 | |

| 25 | Staphylococcus aureus | CECT 239 | |

| 26 | Bacillus subtilis | CECT 498 | |

| 27 | Klepsiella pneumoniae | CECT 144 |

Notes: a Strains source: CECT: Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo, Spain. b Ser: serotype.

For the optimization of the reaction and limit of detection studies, the DNA used as positive control was extracted with Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA was measure with a Nanodrop ND 1000 spectophotometer for making serial dilutions of known concentrations.

For food samples assays, dairy milk, smoked salmon and fresh cheese purchased in the market were spiked with L. monocytogenes (ser 4b) calibrated lenticule discs with known colony forming bacteria units (cfu). For this purpose, 25 mL or 25 g of food sample was mix with 225 mL of Listeria special broth. The mixture was spiked with the desired amount of L. monocytogenes making 10-fold serial dilutions of the lenticule disc between 103–100 cfu in MRD. The enrichment of the spiked food samples was done during 16–18 h at 37 °C. The extraction of the enriched food samples was carried out with the DNeasy PowerFood Microbial Kit according to the manufacturer's instruction.

2.2.7. The LAMP reaction, primer design, specificity analysis and limit of detection

The design and selection of primer sets is the most crucial step in the development of a LAMP reaction. For this study, a primer set targeting hly gene sequence of the L. monocytogenes encoding Listeriolysin O, essential to promote bacterial escape from the phagosomal compartment to the cytoplasm, was designed [42]. Target sequence specificity was analyzed in silico by performing an alignment study involving 12 different serotypes of L. monocytogenes strains registered in the Genbank (National Center for Biotechnology Information-NCBI) and 7 Listeria species (no monocygenes) to ensure a specific design capable of detecting all the reported serotypes. This study was performed using BioEdit v7.0.5.3 software [43] for editing and alignment of nucleic acid sequences and primers. Twenty-one different primers sets were designed with PrimerExplorerv5 software [44] and the critical parameters of the reaction such as MgSO4 concentration, betaine and temperature were experimentally optimized. The best set of primer was selected based on the specificity and sensitivity criteria. The final experimental specificity assays were carried out with 12 strains of the different serotypes of L. monocytogenes, 7 exclusive strains corresponding to other Listeria spp. and 8 exclusive strains of bacteria from different genera (Table 1).

The optimized LAMP reaction was performed in a final volume of 25 μL, consisted on 4 μL of primers FIP (5′-CGG CTT TGA AGG AAG AAT TTT TGA TCT GCC GTA AGY GGR AAA T-3′) and BIP (5′-GGW GGY TCC GCA AAA GAT GAT TTC AAA ATA TCK CGT AAG TCT CC-3′) 1.6 μM, Loop-F (5′-TTG TYA GTT CTA CAT CAC CTG AGA-3′) and Loop-B (5′-AGT TCA AAT CAT CGA CGG YAA CCT-3′) 0,8 μM, F3 (5′-AGT AAA AGC TGC TTT TGA YG-3′) and B3 (5′-YCG RTT AAA AGT AGC RCC TT-3′) 0.2 μM, 2.5 μL of 10X Bst Large buffer, 2 μL of MgSO4 100mM, 3.5 μL of dNTP solution mix, 1.5 μL of Bst large 8u μL−1 and 1 μL of calcein 625 μM. The amplification reaction was performed at 65 °C for 50 min and monitored with a real time RotorGene thermocycler at 60 sec. intervals and read with the green filter. During the isothermal reaction, the generated by-product pyrophosphate binds to the calcein bound to manganese ions as well as to magnesium ions, resulting in two detection methods that indicate that the LAMP reaction is successful: fluorescent emissions from calcein and/or the production of manganese phosphate that forms a precipitate that is visually detected [45]. The generated fluorescence was monitored at real time and at the end-point by the naked eye.

To determine the limit of detection of the primers, several serial dilutions of the L. monocytogenes 4b strain extracted DNA were done. Considering the whole genome length of the L. monocytogenes genome, 1 genome copy corresponds to 2.94 fg [46, 47]. Taking this consideration, dilutions with a final concentration of 25 pg, 2.5 pg, 1.25 pg and 0.620 pg corresponding to 8500, 850, 425 and 210 copies, respectively were done. All the reactions were run in triplicate. The limit of detection for the assay was defined as the smallest dilution that gave positive result for all three assays.

2.2.8. Electrochemical detection

For the electrochemical determinations, the LAMP reaction was performed in a final volume of 25 μL, consisted of the same reaction components used for colorimetric and fluorescence based detection exchanging calcein for MB, 8 μL mL−1. MB is a small molecule that intercalates into the new DNA strands generated during the amplification. The intercalated MB is limited in its electroactivity, due to the surrounding nucleotides that prevent the free exchange of electrons that occurs when the MB is free in solution. There is, therefore, an inversely proportional relation between the number of copies generated during amplification (and thus the initial amount of target DNA in the sample) and the electrochemical signal produced by MB.

Three consecutive scans were performed by cyclic voltammetry at a 100 mV s−1 scan rate in a potential window from –175 to +125mV and the height of the oxidation peak of the last one was compared. Two different measurement procedures were followed. On the one hand, “off-chip” determinations, simply placing a 20 μL sample drop covering the three electrodes. On the other hand, “on-chip” measurements, injecting the same sample volume in the mounted chips.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Study of the physicochemical properties of the fluids

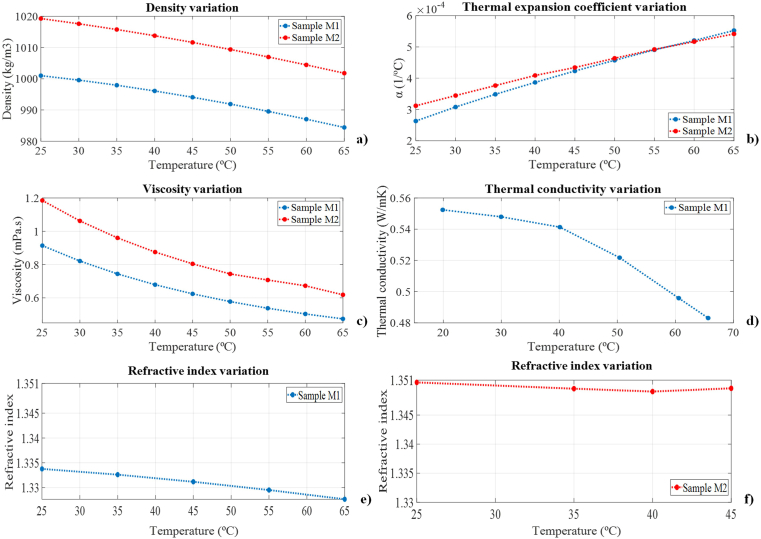

As mentioned in Section 2.2.2, LAMP mixtures (M1 and M2) were characterized to input in the numerical simulations and thus enhance working conditions. The following Table 2 and Figure 3 show the results obtained.

Table 2.

Properties of the LAMP mixtures at 25 °C and 65 °C (fluid) and chip material (solid).

| Material | M1 (25 °C) | M2 (25 °C) | M1 (65 °C) | M2 (65 °C) | Solid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg m−3) | 1000.987 | 1019.290 | 987.041 | 1001.782 | 1020 |

| Thermal expansion (K−1) | 2.63.10−4 | 3.12.10−4 | 5.52.10−4 | 5.42.10−4 | - |

| Thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1) | 0.55 | - | 0.48 | - | 0.2 |

| Specific heat (J kg−1 K−1) | 3023 | - | 1829 | - | 1486 |

| Viscosity (kg m−1 s−1) | 9.139.10−4 | 1.185.10−3 | 4.739.10−4 | 6.1.10−4 | - |

| Surface tension (N m−1) | 0.031 | - | 0.027 | - | - |

| Contact angle (°) | - | - | - | - | 92 |

Figure 3.

Analysis and comparison of the thermophysical properties of samples M1 and M2: density (a), thermal expansion coefficient (b), viscosity (c), thermal conductivity (d), and refractive index (e–f) variations.

Regarding the experimental characterization of the LAMP mixtures, in terms of density (Figure 3a) and dynamic viscosity (Figure 3c), sample M2 presented a higher order value in the whole temperature range analysed, decreasing its density and viscosity as the temperature rises. Both fluids show a similar tendency. Moreover, in the case of thermal expansion coefficient (Figure 3b), a change in trend is shown from 40 °C onwards for the reagent M2. In addition, for the same sample, we could not determine the refractive index (Figure 3e) and (Figure 3f) after reaching a temperature of 40 °C, as it begins to exhibit disturbances. Furthermore, it is observed that the thermal conductivity (Figure 3d) of sample M1 decrease with increasing temperature.

3.2. Numerical analysis

Before the printing and fabrication, a numerical study of the microdevices was performed to predict experimental working conditions and optimize in the microsystem design. Both the temperature distribution as well as the filling process were analysed, considering the working conditions in a LAMP reaction. For the model-experimental validation, the M1 sample was considered since as shown in Table 2, the variation of properties between the two mixtures is negligible to input the numerical simulations. At the same time, the experimental results obtained during the optimization of the LAMP reaction (this section 3.4) proved that there is a better performance of the isothermal reaction using M1 reagents.

The preliminary designs (Figure 4) of the microdevice were carried out using the software Siemens NX 11.0 (Siemens Product Lifecycle Management). The sensor contains an inlet to inject the LAMP reaction reagents and an outlet together with a reaction chamber (length = 9 mm and width = 6 mm) where the detection electrode will be placed. The difference between them is that one contains 90° thus analysing the effect of the geometry (corners) in the filling process. In addition, the second design has a height difference of 0.2 mm between the inlet-outlet and the reaction chamber. In this way, we wanted to improve the filling process by leaving the bubbles out of the reaction area if they are generated. A volume of 20 μL is required to fill the working chamber being higher the amount of reagent needed to fill the entire microfluidic system.

Figure 4.

Designed electrochemical sensors geometries for numerical simulations with (a) and without (b) 90° corners.

The simulations were resolved using the volume of fluid (VOF) multiphase model, defining the primary phase as air and the secondary phase as the LAMP reagent to be introduced. This model solves a single set of governing equations by tracking the volume fraction of each of the fluids in the entire domain [48]. First, the characteristics (Table 2) of the LAMP reagent determined and/or mentioned in section 3.1 were introduced. Apart from that, the properties of the air were defined. For that, the Fluent software database [49] was used. In addition, the characteristics such as the thermal conductivity and contact angle of the sensor material, an acrylic resin were specified using data from literature [50].

Furthermore, the same working conditions were set at Figure 4 for both simulations. On the one hand, a temperature of 65 °C was applied at the bottom of the sensor to analyse its homogenization. On the other hand, the inlets (mass-flow type) and outlets (pressure-outlet) of the microdevice were defined to analyse the filling process over time and ensure that no bubbles were generated.

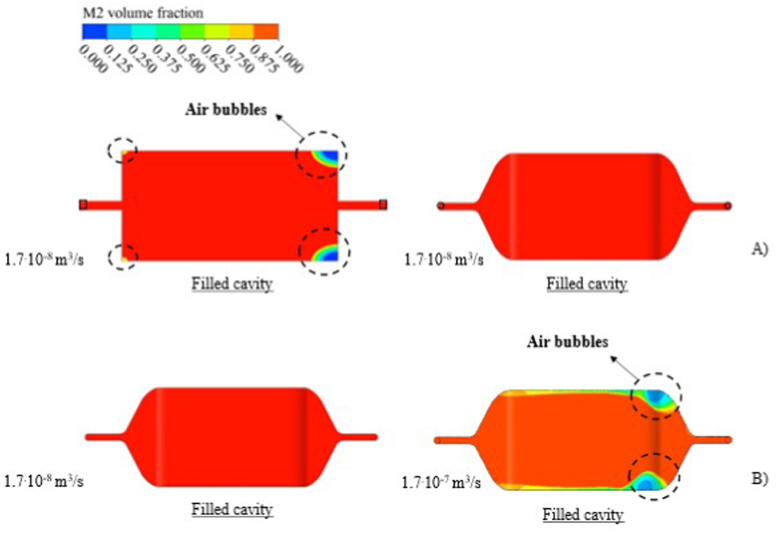

Regarding the numerical results obtained, the effect of the geometry on bubble generation was analyzed (in the filling process) for the same injection flow rate. For this purpose, a volume rate of 1.7.10−8 m3 s−1 was applied and observed (Figure 5a) that for the first geometry (Figure 4a), bubbles are always generated in the microdevice. These bubbles appear regardless of the applied inlet volume velocity. For this reason, the printing of this microdevice was rejected.

Figure 5.

Numerical results of the microdevice filling process analyzing the effect of the designed geometries (a) and the used injection flow rates (b).

For the second geometry designed (Figure 4b), the correlation between the injection flow rate and the filling of the sensor was studied. LAMP reagent under two different conditions 1.7.10−8 m3 s−1 and 1.7.10−7 m3 s−1 was injected. The results obtained (Figure 5b) showed that with a ten times higher volume velocity, the filling is not correct for this geometry. Furthermore, with flow rates lower than 1.7.10−8 m3 s−1 no bubbles were generated, even if the filling time is longer.

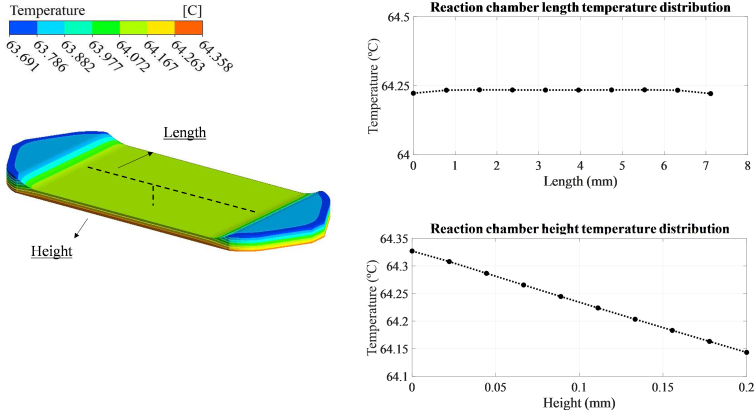

In addition, the temperature distribution along the electrochemical sensor was also simulated. The numerical results (Figure 6) showed a uniform temperature distribution throughout the sensor chamber, with a variation of less than 1° between the inlet-outlet and the area where the electrode is to be placed. Moreover, in the reaction chamber, the temperature difference between the top and bottom part is smaller than 0.2 °C and the variation along the length is negligible, 0.01 °C.

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution over the reaction chamber together with different graphs representing the variation along the height and length of the electrochemical sensor.

3.3. Experimental analysis

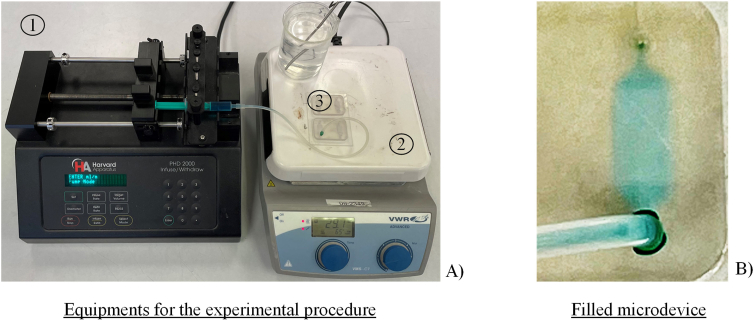

After the 3D printing of the sensor and before starting with the design of the electrode, an experimental analysis was carried out to verify the correct impression-fabrication of the chip. Regarding these experiments, the correct filling of the microfluidic chamber was validated using the previously numerically determined flow rate (1.7.10−8 m3 s−1). Moreover, verification that the 3D printed microfluidic system was not leaking was done.

For the experimental setup, an infusion pump to fill the reaction chamber together with a heater to replicate a LAMP reaction were selected. Apart from the mentioned equipment, different syringes, and microfluidic tubes to connect the pump with the electrochemical sensor were used.

Regarding the experimental procedure, first the syringe with the LAMP mixture was placed in the infusion pump (Figure 7a (1)). After that, the microfluidic tubes were connected to the microdispositive (Figure 7a (3)) positioned above the heater (Figure 7a (2)), thus generating a closed circuit for a constant flow rate. To finish, a temperature of 65 °C was applied and the sample to be studied was injected at the desired flow rate.

Figure 7.

Experimental set up (a) used to test the fabricate devices: 1) Infusion pump to fill the reaction chamber, 2) heater and 3) printed chip. An example of filled sensor without bubbles and leakages (b).

As for the results obtained (Figure 7b), verified that no bubbles are generated in the filling process and the sealing of the chip is right.

3.4. LAMP assay for Listeria monocytogenes detection

For the LAMP assay 21 set of primers specific for L. monocytogenes were designed with the software PrimerExplorerv5. The designed primer sets were tested and the critical reaction such as temperature and, betaine and MgSO4 concentrations, were optimized. The reaction containing the calcein, the dye molecule that binds to the manganese ions and quenches the fluorescence, was monitored in real time by fluorescence and observed by the naked eye at the end-point when positive samples change of colour from orange to green [45].

After optimization of all parameters the best candidate, named LM19, was selected for further studies. Although, the L. monocytogenes serotype 4b is responsible of a high number of human infections [51], the rest of the serotypes can produce the disease and contaminate food as well. Thus, the specificity study for the LM19 set was performed with DNA extracted from different L. monocytogenes serotypes, other Listeria species and bacteria commonly presented in food (Table 1). The result obtained showed an unspecific detection of Listeria welshimeri and a false negative result for the L. monocytogenes serotype 3c strain (Data not shown).

This nonspecific detection was due to similarities between the target DNA sequences of L. welshimeri and L. monocytogenes. In contrast, the false negative result was due to SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) present in the amplified region of the gene for the different L. monocytogenes serotypes. To address these results, a redesign of the LM19 primer set, was carried out, on the one hand, by an exhaustive analysis of the SNPs of the different serotypes of L. monocytogenes and, on the other hand, by studying the matches with the DNA of L. welshimeri. Accordingly, degenerated nucleotides for the new LM19v2 primers set were included, and subsequently, the specificity study against the L. monocytogenes serotypes, Listeria spp. and other bacteria was performed.

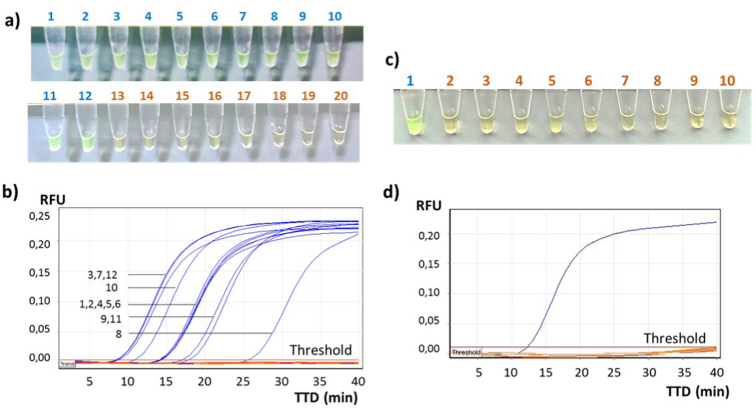

The LM19v2 primer set specifically detects genomic DNA from all 12 L monocytogenes serotypes, as can be seen in Figures 8a and b. The detection of all the serotypes involved with foodborne listeriosis significantly improves the results reported by other authors for different transduction systems and sensor platforms. All of them probed to detect only one serotype of L. monocytogenes [52, 53, 54, 55, 56]. Otherwise, this primer set did not detect DNA from any of the non-monocytogenes Listeria spp. (Figures 8a and Fig. 8b) or DNA from other bacteria genera panel (Figures 8c and Fig. 8d). This assay was monitored at real time by fluorescence and the TTD (time to detection) result was considered to assess the amplification performance. The TTD represents the time in minutes between the start of the reaction and the beginning of the amplification process, where the fluorescence emission starts to be detected. Results were observed at endpoint by a colour change in the positive samples from orange to green.

Figure 8.

Specificity results for the LM19v2 primer set. a) Colorimetric results; L. monocytogenes serotypes in green (Table 1: 1–12) and other Listeria species (Table 1: 13–19) and the negative control in orange (CN). b) Fluorescence emission results for L. monocytogenes serotypes represented in blue and other listeria in orange (same samples of image a), c) Colorimetric results; L. monocytogenes in green (CP) and exclusive species (Table 1: 20–27) and the negative control in orange (CN). d) Fluorescence emission results for L. monocytogenes serotypes represented in blue and other Listeria species in orange (same samples of image c); Time To Detection (TTD) represented at the bottom (min) and RFU (Relative Fluorescens Units) on the left side.

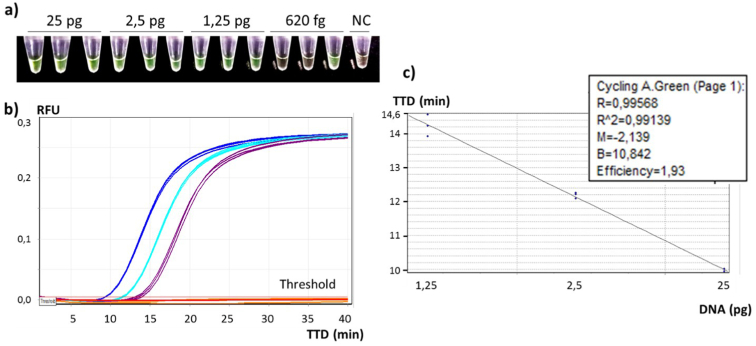

The limit of detection study was performed with genomic DNA extracted from L. monocytogenes serotype 4b (CECT 935), considered as one of the reference strains by the WDCM reference strain catalogue (WDCM Reference Strain Catalogue) [57]. Colorimetric end-point detection was positive for 3/3 amplified runs down to 1.25 pg of L. monocytognes DNA and for 1/3 runs of 620 fg (Figure 9a), showing the same bright green colour for all positive results, in contrast to orange ones for negatives samples. Therefore, the limit of detection was fixed at 1.25 pg, equivalent to 425 genomic copies of L. monocytogenes [46].

Figure 9.

Detection limit results obtained for L. monocytogenes CECT 935 (serotype 4b) a) Colorimetric results; different amounts of L. monocytogenes genomic DNA, positive samples in green and negative samples in orange. NC: Negative control. b) Real-time monitorization of the fluorescence, TTD represented at the bottom (min) and RFU (Relative Fluorescens Units) side emitted by 25pg in blue, 2.5pg in light blue and 1.25pg in violet of L. monocytogenes DNA, in the left. c) Correlation between DNA amount represented at the bottom (pg) and TTD on the left side (min).

Real time results showed that a concentration range of 25 pg–1.25 pg of L. mocytogenes DNA (n = 3) was detected in less than 20 min (Figure 9b). An excellent linear correlation between the DNA quantity and the TTD fluorescence signal over a range of 3 logarithmic orders was achieved (R2 of 0,991) (Figure 9c). This correlation will be evaluated in further studies to quantify the amount of L. monocytogenes in the sample, making the assay a quantitative detection method.

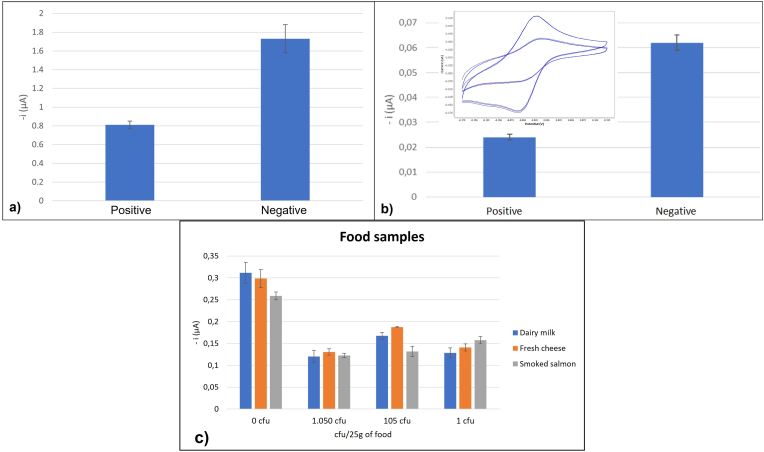

3.5. Electrochemical measurement

The verification of the sensor for detecting L. monocytogenes was initially performed in the off-chip configuration, by comparing the electrochemical response of LAMP amplification products, which include MB in the reaction buffer (see materials and methods). The assay was carried out with 250 pg of DNA extracted from L. monocytogenes serotype 4b as target for positive measurements and no-DNA for negative ones (n = 3). As shown in Figure 10a, the height of the current peak for the positive sample is lower, due to the intercalation of the MB molecules in the DNA chains created during the amplification process. The intercalated redox active molecule has its electron transfer process hindered due to the surrounding nucleotides compared to the free MB. Thus, the discrimination between a positive and a negative sample is performed in a timeframe around 1 min. The reduction in the registered current can be therefore correlated with the number of generated copies.

Figure 10.

Validation of the assay for the electrochemical detection of L. monocytogenes in the off-chip configuration (a). Validation of the assay for the electrochemical detection of L. monocytogenes on-chip configuration. Voltammograms and peak currents for the positive and negative samples (b). Food sample validation with the on-chip configuration, dairy milk results in blue, fresh cheese in orange and smoked sample in grey. Current peak represented on the left and L.monocytogenes cfu/25 g of food in the bottom (c).

The on-chip configuration was finally tested using the same positive and negative LAMP product samples; 250 pg of L. monocytogenes DNA as positive and PCR grade water as negative (Figure 10b). The assembled chips (Figure 2c) were filled through the inlet, with 45 μL (volume need to fill the entire microfluidic system) of sample with a micropipette, avoiding the introduction of any air bubbles. Following the previously described procedure, the electrochemical determinations were performed in less than 3 min, obtaining a very reproducible voltammogram, with clear differences between both samples (almost three-fold signal difference) and with clear characteristic redox peaks of the MB. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) associated to the experimental setup was evaluated by using purified and ultrapure water (Milli-Q®) with an electrical resistivity of 18.2 MὨ/cm and absence of MB. The electrical signal noise was estimated well below 10 nA along the potential window, which represents around 3% of the signal for an averaged negative sample. The great reproducibility of the CVs could be attributed to the excellent surface quality of the electrodes and the controlled volume achieved. A reference electrode of a different material was found to be unnecessary, with no observable shift in the oxidation or reduction peaks, which enormously simplifies the fabrication process.

For a further validation of the device, three type of food samples spiked with different concentrations of L. monocytogenes were tested. 25 mL or 25 g of dairy milk, fresh cheese and smoked salmon were spiked with 1050, 105 and 1 cfu. After an enrichment of 16–18 h the food samples were extracted and amplified with the LAMP reaction and the electrochemical measurement was done on-chip. As shown in Figure 10c, the three different samples of dairy milk with spiked L. monocytogenes were successfully detected and the control sample (non-spiked food) was detected as negative. The same results were obtained for the samples of fresh cheese and smoked salmon, being able to detect as little as 1 cfu/25g of L. monocytogenes in the developed electrochemical sensor. A two-sample t-test was used for comparison of electrical current figures associated to positive (n = 30) and negative (n = 9) samples in milk. It showed a value of t of 11.63 and a critical value, tc, of 2.02 for a 95% confidence level. The electrical current intensity measured shows statistically significance difference between these two data sets (p < 0.001). The t-test sample was also repeated for salmon samples, comparing electrical current of positive (n = 15) and negative (n = 6) samples, showing a statistical t of 15.29 for a 95% confidence level (p < 0,001). The same was repeated for cheese, analyzing 18 positive and 6 negative samples for the same confidence level and obtaining a t-value of 10.1, showing statistically significance difference between positive and negative samples (p < 0.001). These results confirmed that the developed sensor has a limit of detection of 1 cfu/25g in the food samples tested.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, a new 3D printed sensor for the specific detection of L. monocytogenes combining LAMP and electrochemical transduction has been developed for the first time. Numerical analysis has been proved to be useful to predict and simulate experimental working conditions and to optimize the design of the LAMP reaction chamber. The developed LAMP uses degenerated primers for the detection of all serotypes of L. monocytogenes involved in foodborne listeriosis and shows a good sensibility with a limit of detection of 1.25 pg DNA per reaction, only 425 L monocytogenes genomic copies. In addition, a fully designed electrode and microfluidic 3D fabricated device were used for the electrochemical detection. By integrating all these multidisciplinar technologies, a 3D printed electrochemical sensor with high potential for the in situ detection of L. monocytogenes in food industry has been developed.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ane Rivas-Macho: Performed the experiments, Analyzed and interpreted the data, Wrote the paper. Unai Eletxigerra: Performed the experiments, Analyzed and interpreted the data, Wrote the paper. Ruth Diez-Ahedo: Performed the experiments. Santos Merino: Analyzed and interpreted the data. Antton Sanjuan: Performed the experiments. Mounir Bou-Ali: Conceived and designed the experiments, Analyzed and interpreted the data. Leire Ruiz-Rubio: Performed the experiments, Wrote the paper. Javier del Campo: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. José Luis Vilas-Vilela: Conceived and designed the experiments. Felipe Goñi-de-Cerio: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Garbiñe Olabarria: Conceived and designed the experiments, Analyzed and interpreted the data, Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Garbiñe Olabarria as supported by Ekonomiaren Garapen eta Lehiakortasun Saila, Eusko Jaurlaritza [KK-2021/00082].

M. Mounir Bou-Ali was supported by Eusko Jaurlaritza [Research Group Program, IT1505-22].

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Wu M.Y.-C., Hsu M.-Y., Chen S.-J., Hwang D.-K., Yen T.-H., Cheng C.-M. Point-of-Care detection devices for food safety monitoring: proactive disease prevention. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schirone M., Visciano P., Tofalo R., Suzzi G. Editorial: biological hazards in food. Front. Microbiol. 2017;7 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02154. 2016–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks United States, 2017: annual report. 2017. http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/fdoss/ (accessed February 24, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doijad S.P., Barbuddhe S.B., Garg S., Poharkar K.V., Kalorey D.R., Kurkure N.V., Rawool D.B., Chakraborty T. Biofilm-forming abilities of listeria monocytogenes serotypes isolated from different sources. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soni D.K., Ahmad R., Dubey S.K. Biosensor for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes: emerging trends. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;44:590–608. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2018.1473331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J.R. Development of point-of-care biosensors for COVID-19. Front. Chem. 2020;8:517. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law J.W.F., Mutalib N.S.A., Chan K.G., Lee L.H. Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: principles, applications, advantages and limitations. Front. Microbiol. 2015;5 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y., Quyen T.L., Hung T.Q., Chin W.H., Wolff A., Bang D.D. A lab-on-a-chip system with integrated sample preparation and loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid and quantitative detection of Salmonella spp. in food samples. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1898–1904. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01459f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., Hase T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Q., Lu J., Su X., Jin J., Li S., Zhou Y., Wang L., Shao X., Wang Y., Yan M., Li M., Chen J. Simultaneous detection of multiple bacterial and viral aquatic pathogens using a fluorogenic loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based dual-sample microfluidic chip. J. Fish. Dis. 2021;44:401–413. doi: 10.1111/jfd.13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawattanapaiboon K., Pasomsub E., Prombun P., Wongbunmak A., Jenjitwanich A., Mahasupachai P., Vetcho P., Chayrach C., Manatjaroenlap N., Samphaongern C., Watthanachockchai T., Leedorkmai P., Manopwisedjaroen S., Akkarawongsapat R., Thitithanyanont A., Phanchana M., Panbangred W., Chauvatcharin S., Srikhirin T. Colorimetric reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) as a visual diagnostic platform for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Analyst. 2021;146:471–477. doi: 10.1039/d0an01775b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olabarria G., Eletxigerra U., Rodriguez I., Bilbao A., Berganza J., Merino S. Highly sensitive and fast Legionella spp. in situ detection based on a loop mediated isothermal amplification technique combined to an electrochemical transduction system. Talanta. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safavieh M., Kanakasabapathy M.K., Tarlan F., Ahmed M.U., Zourob M., Asghar W., Shafiee H. Emerging loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based microchip and microdevice technologies for nucleic acid detection. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016;2:278–294. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachiralurpan S., Sriyapai T., Areekit S., Sriyapai P., Thongphueak D., Santiwatanakul S., Chansiri K. A one-step rapid screening test of: Listeria monocytogenes in food samples using a real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification turbidity assay. Anal. Methods. 2017;9:6403–6410. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma C., Song D., Gu Q., Li P., Zhan L. Reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays allow the rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes in fresh-cut fruits and vegetables. J. Food Saf. 2019;39:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao Y., Jiang Y., Xiong E., Tian T., Zhang Z., Lv J., Li Y., Zhou X. CUT-LAMP: contamination-free loop-mediated isothermal amplification based on the CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage. ACS Sens. 2020;5:1082–1091. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.0c00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becherer L., Borst N., Bakheit M., Frischmann S., Zengerle R., Von Stetten F. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)-review and classification of methods for sequence-specific detection. Anal. Methods. 2020;12:717–746. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonardo S., Toldra A., Campas M. Biosensors based on isothermal DNA amplification for bacterial detection in food safety and environmental monitoring. Sensors. 2021;21 doi: 10.3390/s21020602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh K., Patterson A.S., Ferguson B.S., Plaxco K.W., Soh H.T. Rapid, sensitive, and quantitative detection of pathogenic DNA at the point of care through microfluidic electrochemical quantitative loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:4896–4900. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo J., Fang X., Ye D., Li H., Chen H., Zhang S., Kong J. A real-time microfluidic multiplex electrochemical loop-mediated isothermal amplification chip for differentiating bacteria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014;60:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun W., Qin P., Gao H., Li G., Jiao K. Electrochemical DNA biosensor based on chitosan/nano-V2O5/MWCNTs composite film modified carbon ionic liquid electrode and its application to the LAMP product of Yersinia enterocolitica gene sequence. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010;25:1264–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed M.U., Hasan Q., Mosharraf Hossain M., Saito M., Tamiya E. Meat species identification based on the loop mediated isothermal amplification and electrochemical DNA sensor. Food Control. 2010;21:599–605. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto K., Inada M., Ito K. Multiplex real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification using an electrochemical DNA chip consisting of a single liquid-flow channel. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:3227–3232. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nesaei S., Song Y., Wang Y., Ruan X., Du D., Gozen A., Lin Y. Micro additive manufacturing of glucose biosensors: a feasibility study. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2018;1043:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waheed S., Cabot J.M., Macdonald N.P., Lewis T., Guijt R.M., Paull B., Breadmore M.C. 3D printed microfluidic devices: enablers and barriers. Lab Chip. 2016;16:1993–2013. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00284f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padash M., Enz C., Carrara S. Microfluidics by additive manufacturing for wearable biosensors: a review. Sensors. 2020;20 doi: 10.3390/s20154236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prabhakar P., Sen R.K., Dwivedi N., Khan R., Solanki P.R., Srivastava A.K., Dhand C. 3D-Printed microfluidics and potential biomedical applications. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021;3 [Google Scholar]

- 28.He Y., Wu Y., Fu J., Gao Q., Qiu J. Developments of 3D printing microfluidics and applications in chemistry and biology: a review. Electroanalysis. 2016;28:1658–1678. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amin R., Knowlton S., Hart A., Yenilmez B., Ghaderinezhad F., Katebifar S., Messina M., Khademhosseini A., Tasoglu S. 3D-printed microfluidic devices. Biofabrication. 2016;8 doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/2/022001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.dos Santos D.M., Cardoso R.M., Migliorini F.L., Facure M.H.M., Mercante L.A., Mattoso L.H.C., Correa D.S. Advances in 3D printed sensors for food analysis. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2022;154 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardoso R.M., Kalinke C., Rocha R.G., dos Santos P.L., Rocha D.P., Oliveira P.R., Janegitz B.C., Bonacin J.A., Richter E.M., Munoz R.A.A. Additive-manufactured (3D-printed) electrochemical sensors: a critical review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2020;1118:73–91. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sochol R.D., Sweet E., Glick C.C., Wu S.-Y., Yang C., Restaino M., Lin L. 3D printed microfluidics and microelectronics. Microelectron. Eng. 2018;189:52–68. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khosravani M.R., Reinicke T. 3D-printed sensors: current progress and future challenges. Sens. Actuat. A Phys. 2020;305 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang W., Wu T., Shallan A., Kostecki R., Rayner C.K., Priest C., Ebendorff-Heidepriem H., Zhao J. A multiplexed microfluidic platform toward interrogating endocrine function: simultaneous sensing of extracellular Ca2+ and hormone. ACS Sens. 2020;5:490–499. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b02308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang Y., Sun J., Ye Y., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Sun X. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based microfluidic chip for pathogen detection. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;60:201–224. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1518897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X., Li M., Liu Y. Microfluidic-based approaches for foodborne pathogen detection. Microorganisms. 2019;7:381. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7100381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Özay B., McCalla S.E. A review of reaction enhancement strategies for isothermal nucleic acid amplification reactions. Sens. Actuat. Rep. 2021;3 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Errarte A., Martin-Mayor A., Aginagalde M., Iloro I., Gonzalez E., Falcon-Perez J.M., Elortza F., Bou-Ali M.M. Thermophoresis as a technique for separation of nanoparticle species in microfluidic devices. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2020;156 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanjuan A., Errarte A., Bou-Ali M.M. Analysis of thermophoresis for separation of polystyrene microparticles in microfluidic devices. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2022;189 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trung N.B., Saito M., Tamiya E., Takamura Y. Accurate and reliable multi chamber pcr chip with sample loading and primer mixing using vacuum jackets for N × M quantitative analysis. 14th Int. Conf. Miniaturized Syst. Chem. Life Sci., MicroTAS 2010. 2010;3:1775–1777. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasebe R., Nakao R., Ohnuma A., Yamasaki T., Sawa H., Takai S., Horiuchi M. Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b strains replicate in monocytes/macrophages more than the other serotypes. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017;79:962–969. doi: 10.1292/jvms.16-0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayal S., Charbit A., Listeriolysin O. A key protein of Listeria monocytogenes with multiple functions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006;30:514–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall T.A. BioEdit: a user friendly biological alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eiken chemical genome site primer explorer v5. 2016. http://primerexplorer.jp/elamp4.0.0/index.html (accessed May 23, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomita N., Mori Y., Kanda H., Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:877–882. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glaser P., Frangeul L., Buchrieser C., Rusniok C., Amend A., Baquero F., Berche P., Bloecker H., Brandt P., Chakraborty T., Charbit A., Chetouani F., Couvé E., de Daruvar A., Dehoux P., Domann E., Domínguez-Bernal G., Duchaud E., Durant L., Dussurget O., Entian K.D., Fsihi H., García-del Portillo F., Cossart P. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science (80-.) 2001;294:849–852. doi: 10.1126/science.1063447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez-Lázaro D., Hernández M., Pla M. Simultaneous quantitative detection of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes using a duplex real-time PCR-based assay. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004;233:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fluent, Chapter 18. Introduction to Modeling Multiphase Flows. Ansys - Fluent Man; 2001. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canonsburg T.D. Vol. 15317. ANSYS Inc.; USA: 2013. p. 814. (ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunes P.S., Ohlsson P.D., Ordeig O., Kutter J.P. Cyclic olefin polymers: emerging materials for lab-on-a-chip applications. Microfluid. Nanofluidics. 2010;9:145–161. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braga V., Vázquez S., Vico V., Pastorino V., Mota M.I., Legnani M., Schelotto F., Lancibidad G., Varela G. Prevalence and serotype distribution of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from foods in Montevideo-Uruguay. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017;48:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srisawat W., Saengthongpinit C., Nuchchanart W. Development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification-lateral flow dipstick as a rapid screening test for detecting Listeria monocytogenes in frozen food products using a specific region on the ferrous iron transport protein B gene. Vet. World. 2022;15:590–601. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.590-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tasbasi B.B., Guner B.C., Sudagidan M., Ucak S., Kavruk M., Ozalp V.C. Label-free lateral flow assay for Listeria monocytogenes by aptamer-gated release of signal molecules. Anal. Biochem. 2019;587 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2019.113449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y., Wang H., Xiao S., Wang X., Xu P., Wang X., Xu P. A triple functional sensing chip for rapid detection of pathogenic Listeria monocytogenes. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Q., Yao C., Yang C., Liu Z., Wan S. Development of an in-situ signal amplified electrochemical assay for detection of Listeria monocytogenes with label-free strategy. Food Chem. 2021;358 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saini K., Kaushal A., Gupta S., Kumar D. PlcA-based nanofabricated electrochemical DNA biosensor for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk samples. 3 Biotech. 2020;10 doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02315-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.WDCM reference strain catalogue. 2022. https://refs.wdcm.org/search/searchkey (accessed May 9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.