Abstract

Social protests can be devastating since they can cause economic setbacks and the loss of life. However, despite their detrimental effects, they are commonplace in Southern Africa. From 2020 to 2021, Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa experienced protests. As such, this study relies on content analysis and primary and secondary data to investigate their root causes. It builds on the frustration-aggression theory to reason that it is the primary explanatory factor for protests in the Southern African countries. This study found that protesters manifested their frustrations through aggression which was revealed when they torched stores, burned property and looted. The unemployment and poverty levels in the countries mentioned above brewed frustrations which culminated in aggressive behaviour that adversely affected businesses. The protests aggravated the already ailing economies when disrupting business transactions in Eswatini and South Africa in particular. Therefore, this study recommends ways of avoiding social protests and their consequences.

Keywords: Protests, Lesotho, Eswatini, South Africa, Unemployment

Introduction

Some theories that account for rebellious behaviour can hardly explain the widespread protests witnessed in Southern Africa in recent years. For instance, collective action theory would have mentioned the quest to provide public good but failed to explain the rationale behind looting and violence that resulted from the protests (Jenkins 1983). Conversely, the rational choice theory would have dwelt on a free-rider problem and fallen back on its head because the protests in these Southern African countries seemed massive and very organized (Kuran 1991). In this context, the failure of rational choice theory would be the assumption that rational self-interested individuals are unlikely to contribute to securing a public good (Olson 1965). There is a need for a theory that would account for the anger expressed in Southern African protests through looting and ransacking.

The failure to understand the root causes of social protests compounds problems. Isolated as protests were in South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini, they have resulted in much damage (Burke 2021; Chokoe 2021). In most cases, violence was witnessed, property looted, injuries sustained, and a high number of deaths reported. The economic losses instigated in one country spilled over to another. For instance, the protest in South Africa in July 2021 caused fuel and food shortages in Lesotho and Eswatini (SABC 2021a). The protest in South Africa aggravated the situation in the latter country (News Reporter 2021). Hence, social protests can delay the delivery of goods, cut the supply chain, lead to the reduction of profits, and ultimately result in job losses and poverty. Despite the lack of understanding of their causes, they have adversely affected Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa within a short time; hence it is worth understanding their patterns and causes.

The reactions of the social protesters in Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa manifested some form of frustration. Commonly, the frustration stems from a sense of injustice emanating from the moral disdain from being wronged. Frustration entails a cognitive process through which a perpetrator of an alleged injustice can be identified (Mikula 2003). Feeling of injustice can stem from the realization that a government illegitimately perpetuates inequality by not making jobs accessible to all those who are qualified to have them. Nepotism and corruption are mostly the causes of such grievances in Africa (Bratton and van de Walle, 1994). Infringing on citizens’ entitlements through unjustifiable means is tantamount to injustice.

Perception of injustice does not result from the inability of a government to create jobs. Instead, attribution of responsibility influences the feeling of injustice and deprivation. People’s feeling of entitlement to jobs, which they are precluded from accessing, results in a sense of injustice. Injustice connotes that some agent is responsible for the encountered or experienced hardship, loss and suffering (Montada 1991). Also, citizens feel more deprived when they consider themselves deserving but are prevented from accessing their entitlement due to various reasons such as corruption, nepotism and failure to create jobs (Lancaster 2018).

It would be an exaggeration to claim that all citizens join protests due to a perception of an injustice perpetrated by their government. Since frustration-aggression theory falls short of accounting for the bystanders who eventually feel compelled to join strikes, this paper draws from the snowballing effect to explain the role played by a critical mass. In South Africa, for instance, many people from different societal classes joined the July 2021 protest. The elderly, children, youth, working-class and the poor found themselves in a protest that does not directly affect them (Isilow 2021).

This paper is not only breaking ground by examining the causes of social protests in Southern Africa’s understudied countries like Lesotho and Eswatini, but it also attempts to broaden the applicability of the frustration-aggression theory and bandwagon theory. It is imperative to study these countries that South Africa landlocks to understand the dynamics of the spillover effect in terms of trade flow. Lesotho and Eswatini are small countries that are exceedingly dependent on imports from South Africa; hence, the riots in the latter country significantly affect the former landlocked countries’ economies (World Bank 2020). The three countries are members of a common monetary area and are selected due to their interdependence. In particular, Lesotho and Eswatini are chosen based on their dependence on South Africa.

The paper aims to unearth the root causes of social protests hence it inquires: what caused the social protests in Lesotho, South Africa and Eswatini from 2020 to 2021? The author examines newspapers, journal articles, reports, and online documents to answer this research question. The data from these above sources complement videos from YouTube and South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) news channels which mainly cover news in the three countries mentioned above. Other YouTube videos were broadcast by WION (Indian media) and Kagogo News Channel (Eswatini media) among others. The videos analysed were those covering the protests in the three countries from 2020 to 2021. By examining these data, the author attempts to capture protesters’ perceptions and motives for protesting. In addition, at least two purposively selected key informants who are academics from each country mentioned above were contacted through telephone for additional data and the paper refers to them through pseudo names. To examine the data, the author engaged content analysis to understand the common patterns and themes from the data.

Structurally, this paper is divided into six different parts. This first part is an introduction, while the subsequent is a conceptual review and theoretical framework. The third part traces the origins of poverty, unemployment and inequality in Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa. The fourth examines the motives of the protesters, while the fifth analysis the rationale behind the social protests. Finally, the sixth is the conclusion.

Social protests in the lenses of frustration-aggression and bandwagon theories

Southern Africa has recently seen a wave of protests within a short space of time. Protests are collective challenges posed to the political elite or authorities by people with mutual concerns and common goals seeking reforms in power distribution and resources. When such protests are sustained over time, they can be referred to as social movements (Silva 2015). Protesters collectively resist the authorities to challenge unfavourable policies and push for social, economic, political and environmental justice. Most democracies' legal framework permit citizens to protest.

This paper’s argument is hinged on the frustration-aggression hypothesis or theory to analyze the causes of protests. The theory is essential for explaining violence. Since the 1930s, it has been applied chiefly in psychology, criminology, sociology and ethnology (Elson and Breuer 2017). The theory has undergone alterations and reformulations, but its fundamental assumption of the frustration-aggression still holds. The frustration component of the theory is typically associated with an event instead of emotion and is the one responsible for aggressive behaviour (Elson and Breuer 2017). Despite the decline in the volume of scholarship referring to the theory of frustration and aggression, it can be applied in political science to account for social protests (Robarchek 1977).

The frustration-aggression hypothesis was first formulated by Dollard et al. (1939, p. 1), who contended that “the occurrence of aggressive behaviour always presupposes the existence of frustration and, contrariwise, that the existence of frustration always leads to some form of aggression.” However, the authors did not refer to frustration as an emotional experience. Instead, they referred to it as an act of interference with or thwarting the occurrence or attainment of someone’s plans or instigated goals. Thus, frustration does not denote an emotional state but an event (Dollard et al. 1939). Having noted the deficit in the hypothesis mentioned earlier, the authors reframed it to disqualify its deterministic assumption to contend that the instigation produced by frustration is not limited to aggression (Miller et al. 1941; Roberchek, 1977). Hence, aggression is simply one of the frustrations’ many possible outcomes or consequences.

The frustration-aggression theory was adjusted to cater for the contextual forces. Pastore (1952, p. 279) maintained, “The occurrence of the aggressive response depends on the subject’s understanding of the situation.” Thus, the shift indicated that the environmental contingencies and internal processes, such as the issue on which frustration is tied, are essential for analyzing the frustration-aggression connections. One crucial factor in understanding this link is the extent to which frustration is regarded as arbitrary. For instance, during a protest in Lesotho, the Prime Minister perceived the demonstration and frustration of protesters as subjective because he assumed it was politically driven. The misconstruing of protesters’ frustrations matters because it can increase the probability and intensity of the likely aggressive behaviour (Pastore 1952; Kulik and Brown 1979).

According to Kulik and Brown (1979), there is a positive correlation between aggression and blame. Aggression intensifies when blame is unjustly attributed to a thwarting. Alternatively, aggressive reactions are aggravated when the thwarting is illegitimate or unjustifiable. Self-caused thwarting produces insignificant anger. Logically, a graduate has more justifiable reasons to demonstrate intense anger due to blocked job opportunities than an unskilled individual. Also, unexpected thwarting results in greater aggression than the expected thwarting (Kregarman and Worchel 1961; Lancaster 2018). As students strive to graduate, some have no idea they are condemned to spend half their lives unemployed—the unexpected thwarting in failure to create jobs results in more frustrations. A goal response must be under implicit or overt operation and prevented from attaining consummation to instigate aggression (Roberchek, 1977). This means that graduates should be in search of job attainment and prevented from accessing them if there is going to be a resulting instigation of aggression.

When a government merely deprives citizens of the opportunity to acquire jobs, this deprivation alone does not constitute frustration. It qualifies to be a frustration as long as it interferes with the gratification of a goal-directed activity (Roberchek, 1977). Where graduates anticipate attaining satisfaction, pleasure and peace after acquiring jobs but are unjustly prevented from accessing them, they are predisposed to frustration. Their frustration results when their access to an activity that fulfils their needs is unjustly foiled.

During protests, the aggression of some protesters may not directly be related to a target. Hence, Berkowitz (1962) and Dollard et al. (1939) assert that the behaviour does not need to be overt; it may be symbolic or expressed through direct attacks on objects or may not appear to be aimed at any target. This explains why frustrated protesters, through job deprivation, may tend to ransack and foray into stores (Crosby, 1982). There is an explanation for people to join a protest that seems unrelated to their agenda. This happens because an occurrence of the relevant aggressive cues within the environment increases the chance of an overt aggressive response (Berkowitz 1962).

Not all citizens frustrated by the thwarting when they strive to attain jobs may join a protest. The individual may realize that some elements of the frustrating situation contain peril (Berkowitz 1962). Thus this serves as an adequate reason to conceal hostility. The fear of sanctions may dissuade some individuals from joining ongoing protests. Frustrated as the individuals may be, their conscience can convince them that hostility would disrespect moral standards; hence guilt may inhibit the expression of one’s hostility. The frustration-aggression theory can hardly explain why individuals who are not frustrated would join a social protest to engage in plundering as it were in Eswatini and South Africa. Hence, at this juncture, this paper shifts to bandwagon theory to complement the frustration-aggression theory.

The bandwagon effect can be accounted for by the involvement of protesters not disgruntled by a thwarting of a social protest, also known as the domino or snowball effect (Gavious and Mizrahi 2001). Some citizens’ decision to refrain from or join a collective action is determined by the number of protesters participating in a social protest (Karklins and Petersen 1993). A large number of protesters reduces the risks of an individual’s involvement in collective action; hence the perception that many people are involved in a social protest attracts more people.

A bandwagon effect is a term assigned to situations where information about the majority’s stance influences people to adopt the same view. The contrast is the underdog effect, whereby the information causes some people to assume a minority perspective. The bandwagon effect has been primarily applied when analyzing elections, voting and opinion polls (Marsh 1985; Farjam 2020). In addition, the model helps explain how critical mass attracts more people to join protests to trigger massive participation in a social protest (Kuran 1991; Rasler 1996).

Origins of poverty and government failures in Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa

Eswatini and Lesotho are monarchies, but the former is an absolute monarch. While the powers of the King are confined to symbolic affairs in Lesotho, in Eswatini, King Mswati’s control extends to strategic resources such as land and the appointment of cabinet members and the Prime Minister. Mswati III holds supreme powers over the legislature, executive and judiciary. In contrast, the Prime Minister is elected in Lesotho, heads the government, and has executive powers, while King Letsie III is the head of state. Both countries adopted the concurrent use of customary and civil laws. Unlike the two constitutional monarchs, the Republic of South Africa is a constitutional democracy with the President elected by the parliament. The President heads the state and the national executive, consisting of the cabinet and Deputy President (Tsikoane et al. 2007; World Bank 2020).

Eswatini and Lesotho were colonized by Britain and gained independence in 1968 and 1966, respectively. The British stripped off the commoner’s land during colonialism to allocate it to chiefs and the royal family. Equally, through the 1913 Natives Land Act, the whites in South Africa allocated merely 7% of land to Africans, who were the majority. Although Africans were better at farming than the whites, they were forced by the Act to be squatters paying rent to whites who owned land instead of being entrepreneurs. Faced with such hardships, some people decided to return to Lesotho and occupy the arable land, thus decreasing the already small land left from the wars with the Boers in South Africa. Hence, Murray (1980, p. 3) noted that Lesotho shifted from being “the granary of the Free State and parts of (Cape) Colony” to becoming a labour reserve for South Africa. As a result, Basotho desperately became migrant workers working in the mines of South Africa and weakened their yield in farming (World Bank 2015a; 2022c, 2020; Plath et al. 1987).

While the British created a cheap labour reserve by depriving ordinary people of their land and engineered poverty by compelling them to depend on employment during colonialism, Lesotho and Eswatini failed to transform their economies after independence. Due to the readily available jobs in South Africa, Basotho and Swazis lacked incentives to be in agriculture. In South Africa, the white settlers used segregation policies and apartheid to impoverish the black race and reserved skilled and semiskilled jobs for whites. Besides, the settlers enacted a 1953 Bantu Education Act to ensure that blacks acquire unproductive education to remain poor (World Bank 2015b; 2022c, 2020).

The blacks were deprived of their freedoms and land when white farmers allocated themselves vast lands, thereby forcing the blacks to survive on low wages from them. Moreover, where they needed to encroach on the land of the blacks, they demolished their townships, compelling them to become tenants. The African National Congress was formed in 1912 to wage a struggle for freedom, and its fruits were realized in 1994 when Nelson Mandela became the President. Since 1994, it constructed 4 million houses for South Africans and promulgated the Land Restitution Act to restore some dispossessed lands, but this process has stalled since 2014 (World Bank 2015b; 2022c, 2020).

The effect of foreign policy changes on economic ills in Southern Africa

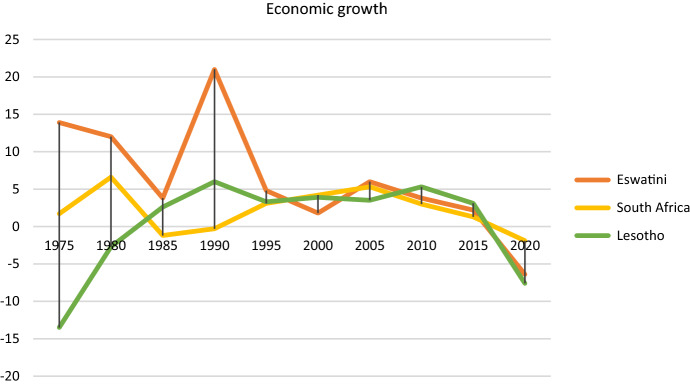

During the apartheid regime of South Africa, Eswatini’s economy experienced its heydays, as illustrated in Fig. 1. It realized at least 8% economic growth per annum since the investment was redirected from South Africa due to its segregation policies. While lucrative agriculture in Lesotho died due to a change in South Africa’s policies, Eswatini maintained a robust economic management system emphasizing education, infrastructure, and health expenditure. By 1995, a year after the demise of South Africa’s apartheid regime, Eswatini created jobs for its citizens as its export base gradually expanded to make it a lower-middle-income country. However, it began to experience setbacks after the end of apartheid.

Fig. 1.

The GDP growth (annual %)—Eswatini, Lesotho, South Africa.

Source World Bank (2021)

In South Africa, however, most blacks were still disadvantaged because they had few assets, poor skills and were unqualified for formal employment (Murray 1980; World Bank 2022c; 2020). The interconnectedness and interdependence of Eswatini, Lesotho and South Africa’s economies are illustrated in Fig. 1. The figure demonstrates how the former country’s productivity declined due to expanding South African investments.

A high level of inequality in Southern Africa is manifested in severe inequality of opportunities (De Juan, and Wegner 2017). Inequality and poverty in Eswatini and Lesotho are traceable to the colonial period when colonialism divided land, governance and employment opportunities between the traditional and modern realms by favouring the former. Poor policies caused unequal access to job opportunities, markets, services, assets and entitlements. Also, apartheid caused problems for South Africa. Wealth is unevenly distributed such that the 10% of wealthy South Africans own 70.9% of the total household net wealth of the economy (World Bank 2020). Among the rich are the South African Indians because the apartheid regime was lenient towards them. Similarly, Lesotho features among the countries with high inequality globally. Consequently, the countries’ entrenched inequality of opportunities thwarts some people from combatting poverty (World Bank 2022c; 2020).

After the demise of the apartheid regime in South Africa, Eswatini’s economic growth declined by 3% from 2000 to 2010 and 2.6% from 2011 to 2018. The World Bank (2020) notes that Eswatini’s economic policies were weak and inconsistent during these setbacks; hence investment shifted to South Africa. The poverty and income inequality levels are high in Eswatini, which is not befitting for a lower-middle-income country. While poverty seems to have declined in 2001 in Eswatini, the absolute number of poor citizens surged from the same year to 2017. Deprivation in access to health, education and public services crippled Eswatini (World Bank 2015b; 2022c, 2020).

The aggravation of poverty in Southern Africa during COVID-19

Besides the shift in South Africa’s policies that adversely affected Eswatini and Lesotho’s economic performance, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the situation in the three countries (Lees, et al. 2020; Arndt et al. 2021). The two adverse factors compounded the frustration of the unemployed graduates who felt they deserved jobs. Since 2015, the three countries’ economic performance remained poor, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, they contracted sharply in 2020, primarily due to the COVID-19-related restrictions and several country lockdowns despite efforts meant to curb the pandemic’s effects listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Efforts implemented by Southern African countries to mitigate poverty

| South Africa | Lesotho | Eswatini |

|---|---|---|

| Free primary and high school education | Free primary education | Free primary education |

| Free health care | Free health care | Free health care |

| Disabled persons’ grant | Disabled persons’ grant (Vulnerability grant) | Disabled persons’ grant |

| Orphanage grant | Orphanage grant (Vulnerability grant) | Orphanage grant |

| Old age grant | Old age grant | Old age grant |

| Social relief grant (introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic) | COVID-19 lockdown support (temporary support for selected economic sectors) | None |

| Child support grant (0–18 years) | None | None |

Source Fieldwork (2022)

The three countries under scrutiny have unevenly distributed poverty between rural and urban areas. For example, in South Africa, rural poverty was estimated at 80.3% in rural areas and 40.1% in urban areas in 2015, while in Lesotho, it was about 61% in rural areas and 39% in urban areas in 2017, and 80% of its population lived in rural areas. In 2017, Eswatini’s rural poverty was 70.1% compared to the 19.6% in urban areas, and it is worth noting that its rural inhabitants make up 90% of the country’s 1.1million population.

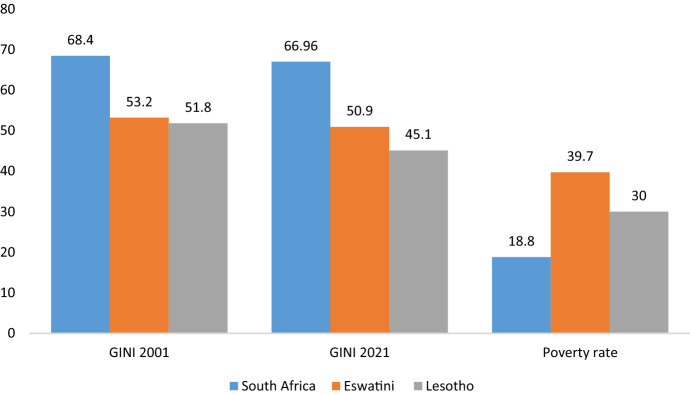

Persisting poverty and inequalities in the three countries under investigation stimulated citizens’ frustrations. For example, Lesotho’s poverty levels stagnated at around 30% between 2020 and 2021, with the $1.90(USD)/ person/day (in 2011 Purchasing Power Parity terms). Similarly, Eswatini’s poverty levels stagnated at high levels for half a decade, with 39.7% of the population estimated to live under the international $1.90 poverty line in 2016 and 2017. Equally, South Africa’s poverty level was estimated at around 18.8% in 2015, as indicated in Fig. 2 (World Bank 2021; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and The World Bank, 2022a, 2022b).

Fig. 2.

Poverty, unemployment and income inequality levels in Southern Africa.

Source World Bank (2022c, 2022a, 2022b) and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and The World Bank (2022)

The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the macroeconomic performance and budgetary constraints of the three countries, limiting their fiscal capacity to respond to shocks. In addition, Lesotho and Eswatini’s geographical proximity and close economic ties with South Africa as a hegemony with porous borders affect the two countries economic performance. For instance, more than 60% of Basotho households depend on monthly remittances from South Africa, and the COVID-19 lockdowns significantly threatened Lesotho’s economy, as Fig. 1 indicates (World Bank 2020, 2022a, 2022b; International Bank for Reconstruction & Development and The World Bank, 2022a, 2022b). Equally, exports and remittances, on which Basotho households depend on as depicted in Fig. 3, dropped significantly, especially with the shut-down in South Africa.

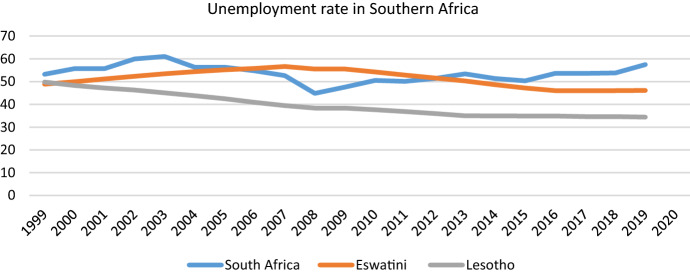

Fig. 3.

The unemployment rate in Southern Africa.

Source O’Neill (2021)

The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and The World Bank (2022a, b, c) assessed the Gini index to measure the extent to which the distribution of income or consumption expenditure among households in Lesotho, South Africa and Eswatini deviated from a perfectly equal distribution. The study found that South Africa is the most unequal country in the world, ranking first among 164 countries in the World Bank’s global poverty database. Botswana, Eswatini, and Namibia are among the 15 most unequal countries, while Lesotho still ranks among the top 20 making it better than its counterparts, as indicated in Fig. 2. The bandwagon effect of South Africa and Eswatini protests is more likely to be intense than in Lesotho due to profound inequalities in the two countries. Equally, the looting may be higher in the two countries because of pronounced inequalities, as revealed in Fig. 2.

Most importantly, unemployment is high in Lesotho and Eswatini due to poor labour market outcomes and diminishing productivity (Damane and Sekantsi 2018; Kali 2020). A sizeable percentage of the population lives in rural areas and lacks access to services. While inhabitants of rural areas are unqualified for formal employment in urban areas, educated graduates find it hard to acquire jobs. In Lesotho, the government is the primary source of employment, and the private sector is mainly concentrated on textile industries that pay low wages. In Eswatini, while most youth languish in dire poverty, King Mswati indulges in opulence. He maintains at least 15 wives, private jets, a fleet of poshest vehicles such as Rolls Royce, expensive mansions, and an entourage that travels the world with him (Keimey, 2016). Despite his extravagant life, over 60% of Swazis live under $1.25 per day, and 80% are below $2 per day (Kimeyi, 2016; African Insider; 2021). Unemployment in Eswatini is gradually increasing. Likewise, just 64.2% of black South Africans, compared with 5.2% of South African Indians and 41.3% of coloureds (a person of mixed descent speaking Afrikaans or English as mother tongue) lived under $1.90 per day in 2015 (Damane and Sekantsi 2018; World Bank 2022c; 2020). Figure 3 illustrates the unemployment rate in Eswatini, Lesotho and South Africa from 1999 to 2020.

Mechanisms for mitigating poverty and frustration in Southern Africa

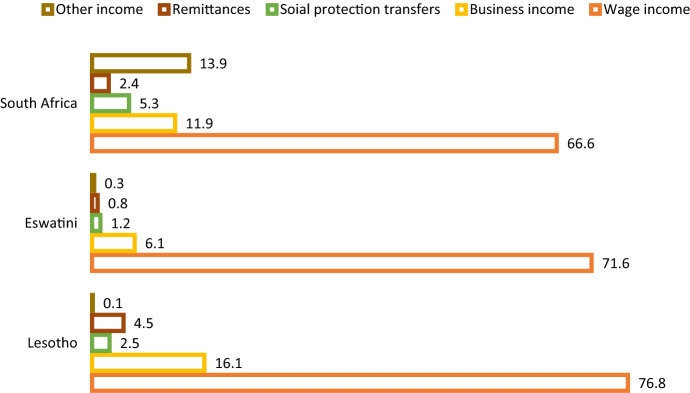

Southern African countries under scrutiny adopted several mechanisms and policies to curb poverty, inequality and, by extension, citizens’ frustrations. As a result, South Africa and Lesotho have high social protection than Eswatini to support the poor, as Fig. 4 illustrates. However, Lesotho desperately depends on remittances, which hints at its dependence on South Africa (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development & The World Bank, 2022a, 2022b).

Fig. 4.

Decomposition of inequality by income source in Southern Africa.

Source Adapted from International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and The World Bank (2022)

Figure 4 shows the decomposition of inequality by income source. The income sources assessed are wage incomes, business income (profits and agricultural income), social transfers (such as social protection benefits, pensions, and other government grants), remittances (including gifts), and other income sources. Social protection transfers are highest in South Africa, and remittances are highest in Lesotho since many Basotho depend on employment in South Africa (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development & The World Bank, 2022a, 2022b). In addition, the two countries have made more efforts than Eswatini to curb unemployment, poverty and citizens’ frustration by providing social grants, free primary education, and elderly social grant, among others. Table 1 illustrates the social grants and efforts implemented by the three countries to mitigate poverty and frustrations.

South Africa attempted to curb its inequality more than its counterparts, but problems persist (De Juan, and Wegner 2017; Cotterill, 2021). Since corporate ownership, management positions and high-salary jobs remained mainly in the hands of the white; the government introduced some interventions such as the Broad-based black economic empowerment (BBBEE) Act in 2003 to usher the blacks into economic positions. However, in practice, Kedy (one respondent from South Africa) revealed that the whites still earn more than the blacks because employers decide to prioritize them even when doing the same job.

Protests and unemployment in Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa

This paper argues that all the social protests witnessed in South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini between 2020 and 2021 were ignited by frustration with the government. The citizens, particularly the youth, realized that their governments had thwarted their aspirations and goals by not providing jobs after graduation. As a result, they have reached a point where they can no longer sit back and watch poverty go into their houses through their windows.

On 9 November 2020, just eight months before protests were encountered in Eswatini and South Africa, Basotho youth engaged in a protest dubbed #bachashutdown. The youth were disgruntled by inequality and exclusionary policies in the country. They were displeased with the government for designing a Youth Policy without their involvement. They first applied for a permit as required by the Public Meetings and Processions Act 2011 but were denied it. The police cited COVID-19 regulations as an excuse, but the youth disputed that by saying that unemployment is worse than COVID-19. The youth were pushed by hunger out of their homes, as was evident from their placards during the demonstration (SABC, 2021a, 2021b). According to Kolane (2020), one interviewee from Lesotho, contended:

Nothing for us without us! The intolerable and worsening unemployment rate deprives us of our livelihood. Moreover, the source of our depression, justification for substance abuse, and other toxic coping mechanisms render us helpless and frequently lead to death.

The youth tried to hand over their petition to their elected representatives. They requested the government to declare unemployment as a disaster or state of emergency, just as it did with COVID-19. The youth wanted the government to empower them for leadership and create job opportunities. According to SkyAlpha (2020), one interviewee from Lesotho, pointed out:

The government has failed because it is not creating employment and supporting youth businesses. When vacancies are available, they are used to gain political mileage since people are hired based on their political party affiliation. They hire politically. We saw that when there were posts for the Ministry of Home Affairs. They (politicians) fought for the posts. They fail even to create jobs for their loyal people and instead give them the jobs that belong to the nation.

The youth were frustrated because of the high unemployment rate and nepotism (Damane and Sekantsi 2018; Kali 2020). Leronti, an interviewee from Lesotho, pointed out, “We found that nepotism is the biggest problem.” Leronti continued, “There is no way a government that promotes nepotism can create jobs.” The protesters argued that politicians often hijack youth supporting programmes and infiltrate them with their people for political gains whenever the government proposes an initiative to empower the youth or create jobs. As a result, every good policy with the potential to curb unemployment is always politicized and undermined by politicians for political mileage (SkyAlpha 2020; SABC 2021a). Therefore nepotism aggravates the situation characterized by poor policies and undermines even the few good policies (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

The youth demanding employment in Lesotho.

The youth felt they deserved jobs but were deprived opportunities by the politicians. They saw unemployment as severe deprivation of their livelihood. Hence, Sello, an interviewee from Lesotho, said, “If we do not have a job, we do not have a livelihood and dignity(sic).” They were concerned that preference was given to those with political affiliations (The Post 2020). However, the police shot the protesters with rubber bullets and incarcerated about 11 of them for unlawful protest.

On 20 June 2021, seven months after the protest in Lesotho, Eswatini experienced a violent protest, more massive than the one seen in the former country. The protest in Eswatini started after Thabani Nkomonye, a law student, died in May 2021 at the hands of the police. The unrest took shape when Prime Minister Themba Masuku refused to take petitions from the youth to the King and banned all marches. Hence Seluleko, an interviewee from Eswatini, pointed out, “We are not allowed to protest against injustice. We are not allowed to even dare suggest some reforms through petitions.” Thus their grievances were stifled to prevent the expression of their frustrations. Following the incident, Manzini was overwhelmed by protesters who mounted barricades on the roads and torched businesses, especially those linked to the King (White et al. 2021). The police and the army were deployed to quell the protests, and at least 27 people died while more than 150 were injured (Burke 2021; Free Newsletter 2021). Figure 6 illustrates the damage caused by looting in Eswatini.

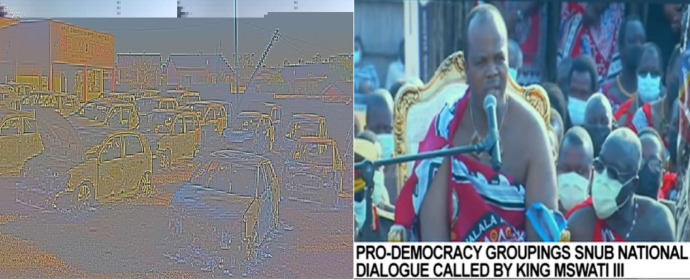

Fig. 6.

Looting in Eswatini and the King addressing the nation.

The demands of the people of Eswatini were twofold. First, they were frustrated by the lack of employment opportunities. Second, they demanded democracy because they believed it would help address their main problem. According to Young (2021), one interviewee from Eswatini, argued:

We want an elected prime minister. We want someone we can hold accountable for everything happening in the country…The King is leading a lavish lifestyle while most people in the country are poor. People do not have jobs, but then there is a guy who has all the money and owns big companies.

While many people raised the issue of unemployment and equality as their frustration, others indirectly alluded to COVID-19. Thandwa, an interviewee from South Africa, uttered, “COVID-19 might have been an indirect impetus because people are feeling more deprived than ever due to lockdown and general economic decline” (Krippahl 2021). The challenges of unemployment, inequality and poverty were always part of people’s frustrations and justification for aggression. Despite the lack of jobs, the looting deprived at least 5000 more people of their jobs (Krippahl 2021).

The protesters’ frustrations were mainly attributed to unemployment and lack of freedom in Eswatini. “We are fighting for jobs, food, democracy and freedoms. Yes, some people tried to exploit the protests for their agenda, but … they were not our people. We are fighting a liberation struggle, not stealing,” contended Siyabonga, an interviewee from Eswatini (Burke 2021). In such instances, intruders can lead to misunderstanding the causes of protests.

Less than a month after protests in Eswatini, South Africa, experienced a massive widespread protest on 10 July 2021. The protest was triggered by the arrest of former President Jacob Zuma, who was facing corruption and bribery charges. Zuma disdained the court order to testify in a Commission of inquiry against state capture and corruption charges perpetrated when he was in power from 2009 to 2018. His court contempt compelled the constitutional court to issue his arrest and sentence him to 15 months imprisonment (Cohen 2021; Outlook web bureau 2021; Eligon and Chutel, 2021).

The jailing of Zuma stimulated protests, especially in Kwazulu Natal, where he resides. Sporadic riots were witnessed here and there and eventually escalated to widespread protests. The protests affected Kwazulu Natal, Johannesburg and Soweto. Not surprisingly, protests started in Kwazulu Natal; hence President Ramaphosa attributed the demonstrations to ethnic mobilization. However, his remarks do not explain the occurrence of riots across the country, especially among the communities which are not Zulu (Cohen 2021; Outlook web bureau 2021). Hence, the bandwagon theory accounts for the widespread protests, although it does not fully explain why many people took to the streets. Frustration and aggression theory explains how unemployment triggered these protests.

Some journalists and analysts attribute the frustrations of South Africans protests to unemployment and poverty. For example, according to Mlaba (2021):

The social protests, which started on 10 July 2021, have heightened to the mass looting of businesses and malls, the destruction of property and the loss of lives during the confrontation with the police. All these are being experienced due to the country’s escalating rates of poverty and inequality.

Other analysts argued that South Africa experienced a massive protest because of its inequality and not the arrest of Jacob Zuma. The disgruntlement was triggered because at least 10% of the people own more than half of the country’s national income while the majority drown in poverty (Mlaba 2021). In addition, at least 2 million people lost their jobs in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which intensified the existing inequality.

Manifestation of frustration and aggression through looting during social protests

The aggression of the protesters was manifested through looting in Eswatini and South Africa. Starting on 25 June, protesters blocked roads, burned tires on the roads, and threw stones at the police that were shooting at them with stun grenades and live bullets in Eswatini. Eventually, the protesters raided many businesses and burned some stores and vehicles. During his speech, King Mswati III estimated the damage done to the property to be around $170 million. The King alleged that drugs intoxicated some protesters. Hence they assumed that he had fled the country. The King’s speech ended without mentioning how the concerns of Swazis would be addressed (SABC 2021a).

Similarly in South Africa, the looting was not a mere expression of aggression, but a means to get food. The director of Economic Justice and Dignity Group maintained:

These protests are triggered by economic issues, not necessarily the political issue of releasing Jacob Zuma. What was needed was a stimulus and the Free Zuma campaign was that. These protests are related to food and have provided a cover for people who feel excluded economically just to come and take over (Mlaba 2021).

Many South Africans were convinced that the protest was instigated by hunger and anger. They were convinced that the violence and looting reflected the depth of poverty in the country. However, President Ramaphosa partly misdiagnosed the problem by attributing it to ethnic affiliations while the challenge is threefold: unemployment, poverty and inequality. Hunger spurred anger in people, hence they expressed their frustration of not getting jobs through looting and stealing. Some people blamed the government for doing little to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on poor people in the country (Chokoe 2021). Figure 7 depicts the looters ransacking foodstuffs from shops.

Fig. 7.

Looting in South Africa.

Source Mlaba (2021)

While many protests in Lesotho resulted in looting (Kali 2022), the recent one did not due to two factors. Firstly, despite the demonstrations lacking police authorization, a parliamentarian listened to the protesters’ demands before the police quelled the protest. Secondly, the media gave platforms to the protesters until the authorities decided to listen and respond to the petition the youth wanted to submit to Prime Minister. Besides, the protests in the three countries did not culminate in social movements mainly due to COVID-19 regulations that ban protests.

Understanding the rationale behind the protests in Southern Africa

Various reasons are often proffered to explain the root causes of protests. Sometimes people claimed that social protests were politically motivated in Eswatini (Burke 2021). Equally, the protest witnessed in South Africa in July 2021 was associated with the discontent triggered by the incarceration of former President Jacob Zuma (SABC 2021b). While these claims seem to hold water, they fail to account for the widespread rampant looting and ransacking throughout the country. If these political motives were the cause of the protest, the demonstrations could have been limited to areas like Kwazulu Natal, where Jacob Zuma’s stronghold and support emanates. The main issue behind the protests has to do with people’s frustrations.

Sometimes protests are associated with the quest for democracy (White et al. 2021; Masuku and Mkentane 2021). When protesters took to the streets in Eswatini, some claimed they were expressing their discontent against King Mswati, who reigned in the country from 1986 until today. King Mswati is an absolute monarch who banned political party pluralism and hold sway over the parliament. He has the power to appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister and ministers. Superficially, it would make sense to claim that the protesters who took to the streets in June 2021 in Eswatini demanded democratic governance. However, Lesotho and South Africa are both democratic but also experienced the same protests around the same period. The COVID-19 pandemic probably exacerbated unemployment, inequality and poverty; hence people vested their frustrations through aggression manifested in looting.

In some cases, protesters are blamed for being manipulated by political parties to mobilize support for a specific agenda. In Lesotho, for instance, the youth took to the streets under the #bachashutdown. As a result, political parties accused them of being misused to rip off the government’s legitimacy. However, their demonstration came after Prime Minister Thomas Thabane, accused of murdering his ex-wife, resigned. Moreover, it was unleashed a few months after Prime Minister Moeketsi Majoro replaced Thomas Thabane. Therefore, it cannot be convincing to claim that political parties mobilized protesters against the newly appointed Prime Minister to discredit him for poor performance.

Given the different contexts of the protest mentioned above, it would not make sense to claim that all protests are politically motivated. Also, claiming that no common or single factor motivated all protests in Southern Africa would manifest some analytical deficit. Despite the countries being unique and their protests having different forms of responses, they reveal a common thread that accounts for them all when they are all examined case by case. Hence, this paper argues that among the various factors responsible for social protests in Southern Africa, there is a common reason for all of them: people’s frustrations.

Citizens of Southern Africa engaged in protests to challenge what they regard as corrupt governments that cannot create jobs. They feel entitled to jobs but are frustrated because they are not accessible due to rampant nepotism and corruption. In terms of corruption in the world, Eswatini ranks 117, Lesotho 83 and South Africa 69; a number close to one signifies a country’s cleanness (Transparency international 2020). In Africa, South Africa ranks 44, Lesotho ranks 41 and Eswatini 33 based on scores where 100 indicates very clean (World Data Atlas 2020). Amongst the three Southern African countries, Eswatini is the most corrupt, followed by Lesotho and South Africa is the least corrupt. The degree of their corruptness is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Corruption perception in Southern Africa.

Source World Data Atlas (2020)

In the two instances of protest in Eswatini and South Africa, the aggression of protesters was not directly connected to the target. While in Lesotho, protesters marched to the National Assembly to hand over petitions because they blamed the government for nepotism and failure to create jobs. In Eswatini and South Africa, the protesters targeted shops. Their frustration was linked to food but not people’s businesses; hence their target was the government. Hence Berkowitz (1962) and Dollard et al. (1939) maintain that the aggressive reaction does not need to be overt or directly linked to the target. Nevertheless, the demonstrations related to the imprisonment of Zuma in South Africa and the killing of a student in Eswatini were pertinent aggressive cues within the environment that increased the probability of more aggressive responses, which have to do with unemployment, inequality and poverty.

Some of the youth did not join the protest in Lesotho. Equally, not every person joined the demonstration in Eswatini and South Africa. Many feared that the police and the army would use disproportionate force and assault them, as it happened in the three countries. As a result, many people were shot and injured in Lesotho, while several died in Eswatini and South Africa. While many were frustrated by unavailable and inaccessible jobs, they could not protest because some phases of the frustration and aggression process contained danger (Berkowitz 1962). Hence they have learned not to resort to an aggressive response when they encounter a situation where their efforts to attain their entitlements are thwarted.

Some photos (see Fig. 7) and videos showed children and older people looting in South Africa. It would be incorrect to claim that the government prevented even children’s attempts to secure jobs. Some videos also portrayed some South Africans loading the loot in their vehicles. A closer outward look at such looters revealed they were not all poor (WION 2021). Hence, it is not their frustrations that allured them to join social protests. Instead, it is the bandwagon effect (see Gavious and Mizrahi 2001). Their decision to join the protest was based on the number of people who were participating in it. They realized that the massiveness of the protest lowers the cost of engaging in it, as witnessed in both Eswatini and South Africa when the police failed to control the demonstrations and soldiers had to be deployed (see Karklins and Petersen 1993).

This study contributes scientific knowledge by blending bandwagon and frustration-aggression theories to examine social protests. Besides expanding the applicability of these theories, it unearths the root causes of social protests and thus facilitates finding solutions to social problems. Thus, this study informs policy and adds to the existing literature on the subject under investigation. However, it does not examine how governments can quell protests without inflicting injuries and killing protesters. Furthermore, the study did not investigate how protesters can effectively vent their frustrations without breaking the law. Lastly, the study could not examine the role of the judiciary in mitigating corruption in Southern Africa despite its significance in contributing to thwarting it. Hence, future research should examine how protests can be effectively managed and prevented and assess the judiciary’s role in curbing corruption.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study attempted to investigate the root causes of protests in three southern African countries which experienced them one after another within 12 months. The author relied on frustration-aggression theory and bandwagon to explain the triggers of protest and collective action. The study relied on content analysis to examine the extant data from primary to secondary sources to understand the common causes of protest.

The author established that protests are disastrous and costly because they resulted in the destruction of property, interruption of business chain and activities, injuries and loss of life in Lesotho, Eswatini and South Africa within a year. The social protest in South Africa adversely affected the two kingdoms because they were largely dependent on it. Social protests are more catastrophic when misunderstood and misdiagnosed, as the issue in question may not be promptly addressed. It is imperative to understand how unemployment, inequality, and poverty cause frustrations and compel people to manifest it through aggression.

This study examined the root causes of the three most recent social protests witnessed in three Southern African countries. All the protests were triggered by poor policies that failed to curb unemployment, inequality and poverty. However, it is sometimes difficult to understand their real cause since protesters’ frustration may not be directly linked to the target. Besides, some people with no stake in the protest often join it. Hence, this study drew from frustration-aggression theory and the snowball effect to shed light on these dynamics of social behaviour during demonstrations.

Eswatini, Lesotho and South Africa can avoid social protests, looting and citizens’ frustrations which lead to aggressive behaviour. The governments of these Southern African countries should strengthen their economic policies to create jobs and curb unemployment. This could be attained by supporting the private sector instead of relying on the public sector to create jobs for every graduate. Furthermore, the countries mentioned above should appraise their education systems to clear all the remains of colonial designs that are ineffective in creating job creators by introducing an education system that encourages the proliferation of entrepreneurs. Finally, the countries in question should be responsive to protesters’ petitions to prevent aggressive behaviour.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to Dr Paul Otieno Onyalo, Advocate Mokitimi Tsosane, Seluleko Langa, and anonymous reviewers for their comments on the paper as well as Mosala Qekisi, Thuso Mosabala and Helene Gouanlewueu Kali for proofreading this work. I would also like to thank the respondents that helped with the data.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are made available by the corresponding author through a private repository under a special request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has declared no conflict of interest.

References

- African Insider (2021). Eswatini Protesters burn King Mswati’s house. Want him out of power [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pA0GMMJ1eFI, Accessed 12 June 2021.

- Arndt C, Davies R, Gabriel S, Harris L, Makrelov K, Modise B, Robinson S, Simbanegavi W, Anderson L (2021) Recovering from COVID-19: economic scenarios for South Africa. International Food Policy Research Institute; https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/download/10734.pdf, Accessed 17 Aug 2021.

- Berkowitz L. Aggression: A social psychological analysis. New York: McGraw-Hil; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton M, Van de Walle N. Neopatrimonial regimes and political transitions in Africa. World Politics. 1994;46(4):453–489. doi: 10.2307/2950715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J (2021) Eswatini protests: ‘we are fighting a liberation struggle. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/08/eswatini-protests-we-are-fighting-a-liberation-struggle, Accessed 19 Sept 2021.

- Chokoe A (2021) The looting of shops during protests is a greater societal problem than meets the eye. The Mail & Guardian. https://mg.co.za/opinion/2021-07-13-the-looting-of-shops-during-protests-is-a-greater-societal-problem-than-meets-the-eye/, Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

- Citizen Reporter (2021) Eswatini pro-democracy protesters burn brewery partly owned by King Mswati. The Citizen. https://citizen.co.za/news/news-world/news-africa/2550753/eswatini-pro-democracy-protestors-burn-brewery-partly-owned-by-king-mswati/, Accessed 19 Aug 2021.

- Cohen M (2021) Bloomberg. Bloomberg - Are you a robot? https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-07-13/why-ex-leader-s-arrest-cast-south-africa-into-turmoil-quicktake, Accessed 19 Aug 2021.

- Cotterill J (2021) We can’t sit back: South Africans Reel from riots. Financial times. https://www.ft.com/content/5d1b9604-8b39-41f0-8d7c-fee2948d6fcf, Accessed 11 Nov 2021.

- Crosby FJ. Relative deprivation and working women. USA: Oxford University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Damane M, Sekantsi LP. The sources of unemployment in Lesotho. Mod Econ. 2018;09(05):937–965. doi: 10.4236/me.2018.95060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Juan A, Wegner E. Social inequality, state-centered grievances, and protest: Evidence from South Africa. J Conflict Resolut. 2017;63(1):31–58. doi: 10.1177/0022002717723136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dollard J, Miller E, Mowrer O, Sears R. Frustration and aggression. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Eligon J., & Chutel L. (2021) The new york times - Breaking news, US news, world news and videos. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/29/world/africa/jacob-zuma-prison.html, Accessed 8 March 2022.

- Elson M, Breuer J. The Wiley handbook of violence and aggression. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farjam M. The bandwagon effect in an online voting experiment with real political organizations. Int J Pub Opin Res. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edaa008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Free Newsletter (2021) Weeks of rioting fail to force reform in Eswatini. The New Humanitarian. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2021/7/13/weeks-of-rioting-fails-to-force-reform-in-eswatini, Accessed 25 August 2021.

- Gavious A, Mizrahi S. A continuous-time model of the bandwagon effect in collective action. Soc Choice Welfare. 2001;18(1):91–105. doi: 10.1007/s003550000061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, & World Bank (2022) New World Bank report assesses sources of inequality in five countries in Southern Africa. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/03/09/new-world-bank-report-assesses-sources-of-inequality-in-five-countries-in-southern-africa, Accessed 01 Jan 2022.

- Isilow H (2021) Death toll amid violent pro-zuma protests in South Africa rises to 23. Anadolu Ajansı. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/death-toll-amid-violent-pro-zuma-protests-in-south-africa-rises-to-23/2303078, Accessed 10 Aug 2021.

- Jenkins JC. Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements. Ann Rev Sociol. 1983;9(1):527–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.09.080183.002523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kagogo News Channel (2021) King mzwati’s address to the nation on the protest [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nHcV7SRcl7cSABC, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- Kali M. Rebellious civil society and democratic consolidation in Lesotho. J Soc Econ Dev. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s40847-022-00189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kali M. Causes and solutions of poverty in Lesotho. Eur J Behav Sci. 2020;3(2):23–38. doi: 10.33422/ejbs.v3i2.396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karklins R, Petersen R. Decision calculus of protesters and regimes: Eastern Europe 1989. J Politics. 1993;55(3):588–614. doi: 10.2307/2131990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimenyi MS (2016) The human development cost of the King of Swaziland’s lifestyle and his “Bevy” of wives. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2012/09/21/the-human-development-cost-of-the-king-of-swazilands-lifestyle-and-his-bevy-of-wives/, Accessed 23 Sept 2021.

- Koloane N (2020) TLI calls on youths to join #BachaShutdown. The reporter Lesotho | Fresh news, daily. https://www.thereporter.co.ls/2020/10/27/tli-calls-on-youths-to-join-bachashutdown/, Accessed 17 Oct 2021.

- Kregarman JJ, Worchel P. Arbitrariness of frustration and aggression. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 1961;63(1):183–187. doi: 10.1037/h0044667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippahl (2021) Eswatini: King Mswati III sitting ‘on a powder keg’. DW.COM. https://www.dw.com/en/eswatini-king-mswati-iii-sitting-on-a-powder-keg/a-58174915, Accessed 10 Oct 2021.

- Kulik JA, Brown R. Frustration, attribution of blame, and aggression. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1979;15(2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(79)90029-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuran T. Now out of never: The element of surprise in the East European revolution of 1989. World Politics. 1991;44(1):7–48. doi: 10.2307/2010422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster L. Unpacking discontent: where and why protest happens in South Africa. S Afr Crime Quart. 2018;64:29–44. doi: 10.17159/2413-3108/2018/i64a3031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lees A, Mascagni G, Santoro F (2020) Simulating the impact of COVID-19 on formal firms in Eswatini. ICTD. https://www.ictd.ac/publication/simulating-impact-covid-formal-firms-eswatini/, Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- Marsh C. Back on the bandwagon: the effect of opinion polls on public opinion. British J Political Sci. 1985;15(1):51–74. doi: 10.1017/s0007123400004063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masuku L, Mkentane L (2021) Eswatini at a standstill as democracy protests turn violent. BusinessLIVE. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/world/africa/2021-06-29-eswatini-at-a-standstill-as-democracy-protests-turn-violent/, Accessed 27 July 2021.

- Mikula G. Testing an attribution-of-blame model of judgments of injustice. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2003;33(6):793–811. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Sears R, Mowrer O, Doob L, Dollard J. The frustration-aggression hypothesis. Psychol Rev. 1941;48(4):337–342. doi: 10.1037/h0055861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mlaba K (2021) Poverty, inequality and looting: Everything you need to know about South Africa’s protests. Global citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/everything-you-need-to-know-south-africa-protests/?template=next, Accessed 17 Oct 2021.

- Montada L. Coping with life stress. In: Steensma H, Vermunt R, editors. Social justice in human relations volume 2: Societal and psychological consequences of justice and injustice. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. p. 930. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. From granary to labour reserve: an economic history of Lesotho. S Afr Labour Bull. 1980;6(4):3–20. [Google Scholar]

- News Reporter (2021) Eswatini reports shortage of fuel. 013NEWS. https://013.co.za/2021/07/15/eswatini-reports-shortage-of-fuel/, Accessed 23 July 2021.

- Olson M. The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups, second printing with a new preface and appendix. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill A (2021) Swaziland - youth unemployment rate 1999–2019 | Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/813070/youth-unemployment-rate-in-swaziland/, Accessed 18 July 2021.

- Outlook web bureau (2021) South African president Ramaphosa condemns violence ‘Based on ethnic mobilization. https://www.outlookindia.com/. https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/world-news-south-african-president-ramaphosa-condemns-violence-based-on-ethnic-mobilisation/387856, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- Pastore N. The role of arbitrariness in the frustration-aggression hypothesis. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 1952;47(3):728–731. doi: 10.1037/h0060884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath J, Holland D, Carvalho J. Labor migration in Southern Africa and agricultural development: some lessons from Lesotho. J Dev Areas. 1987;21(2):159–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasler K. Concessions, repression, and political protest in the Iranian revolution. Am Sociol Rev. 1996;61(1):132. doi: 10.2307/2096410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robarchek C. Frustration, aggression, and the nonviolent Semai. Am Ethnol. 1977;4(4):762–779. doi: 10.1525/ae.1977.4.4.02a00100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SABC (2021a) Eswatini citizens raise concern over shortage of fuel. SABC News - Breaking news, special reports, world, business, sport coverage of all South African current events. Africa’s news leader. https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/eswatini-citizens-raise-concern-over-shortage-of-fuel/

- SABC (2021b) Army deployed in parts of Gauteng and Kwazulu Natal [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tGn86GdFqtw, Accessed 28 July 2021.

- SABC News. (2020) Police heavy-handedly break youth march demanding job opportunities in Lesotho [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MCuWV5cEcZ8, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- Silva E. Social Movements, Protest, and Policy. Eur Rev Lat Am Caribb Stud. 2015;100:27–39. doi: 10.18352/erlacs.10122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SkyAlpha (2020) Bachashutdown - Aluta [Video]. Sky Alpha HD. https://skyalphahd.com/radio/videos/BpmLKoPVgto/, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- The Post (2020) ‘We’re on our own. https://www.thepost.co.ls/news/were-on-our-own/

- Transparency International (2020) Corruption perceptions index 2020 for Swaziland. Transparency.org. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index/swz, Accessed 18 July 2021.

- Tsikoane T, Mothibe T, Ntho M, Maleleka D (2007) Consolidating democratic governance in Southern Africa: Lesotho (32). EISA. https://www.eisa.org/pdf/rr32.pdf, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- White T, Holtz L, Blankenship M (2021) Africa in the news: Eswatini protests, upgrades to Rwanda’s health system, and energy and environment updates. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2021/07/03/africa-in-the-news-eswatini-protests-upgrades-to-rwandas-health-system-and-energy-and-environment-updates/, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- WION (2021) Prozuma protest in South Africa - Google search [Video]. Google. https://www.google.com/search?q=prozuma+protest+in+south+africa&sxsrf=ALiCzsZB6v4CSc2x8UzmgNug_dQgxOxppw:1668952965762&source=lnms&tbm=vid&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiT7a6l9rz7AhXHS8AKHdnDCs8Q_AUoA3oECAMQBQ&biw=1366&bih=625&dpr=1#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:8d4f8ef9,vid:WIHHuVTHMtM, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- World Bank (2015a) Lesotho: systematic country diagnostic (97812). World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23109/Lesotho000Systematic0country0diagnostic.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, Accessed 05 July 2021.

- World Bank (2015b) Republic of South Africa systematic country diagnostic an incomplete transition overcoming the legacy of exclusion in South Africa (125838). World Bank Group. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/815401525706928690/pdf/WBG-South-Africa-Systematic-Country-Diagnostic-FINAL-for-board-SECPO-Edit-05032018.pdf, Accessed 05 July 2021.

- World Bank (2020) Poverty & equity brief South Africa. DataBank | The world bank. https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/33EF03BB-9722-4AE2-ABC7-AA2972D68AFE/Global_POVEQ_ZAF.pdf, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

- World Bank (2021) GDP growth (annual %) - Eswatini, Lesotho, South Africa. World Bank Open Data Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?contextual=default&locations=SZ-LS-ZA, Accessed 02 July 2022.

- World Bank (2022a) The World Bank in Lesotho: overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lesotho/overview#:~:text=Poverty%202021, Accessed 02 Oct 2022.

- World Bank (2022b) The World Bank in Eswatini: overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/eswatini/overview#:~:text=Eswatini%20is%20a%20landlocked%20country,line%20in%202016%20and%202017, Accessed 02 Oct 2022.

- World Bank. (2022c) Inequality in Southern Africa: an assessment of the Southern African Customs Union Inequality in Southern Africa. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099125303072236903/pdf/P1649270c02a1f06b0a3ae02e57eadd7a82.pdf, Accessed 02 Oct 2022.

- World Data Atlas. (2020) Search - knoema.com. Knoema. https://knoema.com/search?query=south+africa&pageIndex=&scope=&term=&correct=&source=Header, Accessed 18 July 2021.

- Young P (2021) It’s getting worse day by day: Pro-democracy protests in Eswatini intensify. The Observers - France 24. https://observers.france24.com/en/africa/20210701-pro-democracy-protests-eswatini-intensify, Accessed 02 Oct 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are made available by the corresponding author through a private repository under a special request.