Abstract

Background

Patellar (knee cap) dislocation occurs when the patella disengages completely from the trochlear (femoral) groove. It affects up to 42/100,000 people, and is most prevalent in those aged 20 to 30 years old. It is uncertain whether surgical or non‐surgical treatment is the best approach. This is important as recurrent dislocation occurs in up to 40% of people who experience a first time (primary) dislocation. This can reduce quality of life and as a result people have to modify their lifestyle. This review is needed to determine whether surgical or non‐surgical treatment should be offered to people after patellar dislocation.

Objectives

To assess the effects (benefits and harms) of surgical versus non‐surgical interventions for treating people with primary or recurrent patellar dislocation.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group's Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, CINAHL, Physiotherapy Evidence Database and trial registries in December 2021. We contacted corresponding authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled clinical trials evaluating surgical versus non‐surgical interventions for treating primary or recurrent lateral patellar dislocation in adults or children.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods. Our primary outcomes were recurrent patellar dislocation, and patient‐rated knee and physical function scores. Our secondary outcomes were health‐related quality of life, return to former activities, knee pain during activity or at rest, adverse events, patient‐reported satisfaction, patient‐reported knee instability symptoms and subsequent requirement for knee surgery. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of evidence for each outcome.

Main results

We included 10 studies (eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and two quasi‐RCTs) of 519 participants with patellar dislocation. The mean ages in the individual studies ranged from 13.0 to 27.2 years. Four studies included children, mainly adolescents, as well as adults; two only recruited children. Study follow‐up ranged from one to 14 years.

We are unsure of the evidence for all outcomes in this review because we judged the certainty of the evidence to be very low. We downgraded each outcome by three levels. Reasons included imprecision (when fewer than 100 events were reported or the confidence interval (CI) indicated appreciable benefits as well as harms), risk of bias (when studies were at high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias), and inconsistency (in the event that pooled analysis included high levels of statistical heterogeneity).

We are uncertain whether surgery lowers the risk of recurrent dislocation following primary patellar dislocation compared with non‐surgical management at two to nine year follow‐up. Based on an illustrative risk of recurrent dislocation in 348 people per 1000 in the non‐surgical group, we found that 157 fewer people per 1000 (95% CI 209 fewer to 87 fewer) had recurrent dislocation between two and nine years after surgery (8 studies, 438 participants).

We are uncertain whether surgery improves patient‐rated knee and function scores. Studies measured this outcome using different scales (the Tegner activity scale, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, Lysholm, Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score and Hughston visual analogue scale). The most frequently reported score was the Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score. This indicated people in the surgical group had a mean score of 5.73 points higher at two to nine year follow‐up (95% CI 2.91 lower to 14.37 higher; 7 studies, 401 participants). On this 100‐point scale, higher scores indicate better function, and a change score of 10 points is considered to be clinically meaningful; therefore, this CI includes a possible meaningful improvement.

We are uncertain whether surgery increases the risk of adverse events. Based on an assumed risk of overall incidence of complications during the first two years in 277 people out of 1000 in the non‐surgical group, 335 more people per 1000 (95% CI 75 fewer to 723 more) had an adverse event in the surgery group (2 studies, 144 participants).

Three studies (176 participants) assessed participant satisfaction at two to nine year follow‐up, reporting little difference between groups. Based on an assumed risk of 763 per 1000 non‐surgical participants reporting excellent or good outcomes, seven more participants per 1000 (95% CI 199 fewer to 237 more) reported excellent or good satisfaction.

Four studies (256 participants) assessed recurrent patellar subluxation at two to nine year follow‐up. Based on an assumed risk of patellar subluxation in 292 out of 1000 in the non‐surgical group, 73 fewer people per 1000 (95% CI 146 fewer to 35 more) had patellar subluxation as a result of surgery.

Slightly more people had subsequent surgery in the non‐surgical group. Pooled two to nine year follow‐up data from three trials (195 participants) indicated that, based on an assumed risk of subsequent surgery in 215 people per 1000 in the non‐surgical group, 118 fewer people per 1000 (95% CI 200 fewer to 372 more) had subsequent surgery after primary surgery.

Authors' conclusions

We are uncertain whether surgery improves outcome compared to non‐surgical management as the certainty of the evidence was very low. No sufficiently powered trial has examined people with recurrent patellar dislocation. Adequately powered, multicentre, randomised trials are needed. To inform the design and conduct of these trials, expert consensus should be achieved on the minimal description of both surgical and non‐surgical interventions, and the pathological variations that may be relevant to both choice of these interventions.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Child; Humans; Young Adult; Fractures, Bone; Knee Joint; Patella; Patellar Dislocation; Patellar Dislocation/surgery; Quality of Life

Plain language summary

Surgery or non‐surgical treatments: which works better to treat people who have a dislocated knee cap?

Key messages

We did not find enough good‐quality evidence to show whether surgery or non‐surgical treatment works better to treat people who have a dislocated knee cap.

Good‐quality research is required that compare these treatments.

What is a dislocated knee cap?

The knee cap is a lens‐shaped bone at the front of the knee. A dislocation occurs when the knee cap completely moves out of the groove in the thigh‐bone at the knee. It typically occurs in young, physically active people when they twist their bent knee whilst their foot is fixed to the ground. The cause of a dislocation may be linked to an abnormal shape of the knee bones, weakness of the muscles around the hip or knees, or tightness of soft tissues on the outside of the knee.

After a knee cap dislocation, some people recover completely. But some people may have repeated dislocations, or a feeling of instability in their knee cap, or both. They may also have persistent pain or limited function.

How is a dislocated knee cap treated?

When the knee cap dislocates, the soft tissues around the knee are injured. People need to have treatment to help restore the knee back to full health. This may include treatments such as holding the knee in place (by wearing a kind of brace or bandage), exercises, manual therapy (such as physiotherapy) and taping the area around the knee. However, some doctors suggest that people may have a better outcome if surgery is performed. Surgery may be used to: repair or reconstruct the injured ligaments and muscles that hold the knee cap in the groove, reshape the groove, or change where the knee cap attaches to the shin‐bone to stop it from dislocating again.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out whether surgery or non‐surgical treatment was better at preventing another knee cap dislocation and restoring knee function. We also looked at any unwanted effects of treatment, how satisfied people were with their treatment, symptoms of instability and the need for surgery after the initial treatment.

What did we do?

We searched the medical literature until December 2021 for studies that compared surgical with non‐surgical treatment for adults or children who had a patellar dislocation. We summarised and compared the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 10 relevant studies (519 adults and children). Studies randomly allocated people to receive surgery or a non‐surgical treatment. In nine studies, people were treated for a first‐time dislocation, one study treated people after repeated knee cap dislocations. People ranged from 13 to 27 years of age, with six studies including children. People in the studies were monitored from one to nine years after their injury.

Main results

We were very uncertain about whether surgery compared to non‐surgical treatment:

‐ reduced the number of repeat dislocations;

‐ affected how well the knee cap worked;

‐ increased or reduced the risk of side effects;

‐ made a difference to how satisfied people were with treatment;

‐ increased or reduced instability in the knee cap; or

‐ increased or reduced the need for additional surgery.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

These studies were small. Some had weaknesses in their design and conduct. The quality of the evidence is very low. We were very uncertain about these findings.

How up to date is this evidence?

This review updates our previous review. The evidence is up to date to December 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Surgical compared with non‐surgical treatment for patellar dislocation.

| Surgical compared with non‐surgical treatment for patellar dislocation | ||||||

|

Population: people with lateral patellar dislocation Settings: hospital (surgical) and hospital/rehabilitation centres (non‐surgical). Countries where trials were conducted included Brazil, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and the UK. Intervention: surgical procedures, including: MPFL repair, MPFL reconstruction, medial retinacula repair, medial reefing, lateral release, tibial tuberosity transfer, modified Roux Goldwraithe procedure and osteochrondral fracture repair. Comparison: non‐surgical treatments, including bracing/orthoses and exercise‐based rehabilitation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Non‐surgical | Surgical | |||||

|

Number of participants sustaining recurrent patellar dislocationa Follow‐up: two to nine years |

348 per 1000b | 191 per 1000 (139 to 261) |

RR 0.55 (0.40 to 0.75) |

438 (8) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝c Very low | Surgery resulted in 157 fewer (95% CI 209 fewer to 87 fewer) people per 1000 having a recurrent dislocation during this time. |

|

Knee and physical functiona Measured using the Kujala patellofemoral disorders scorea Scale from: 0 to 100 (higher scores = better function) Follow‐up: two to nine years |

The mean Kujala patellofemoral disorders score in the non‐surgical group was 81.90points | The mean Kujala patellofemoral disorders score in the surgical groups was 5.73 points higher (2.91 point lower to 14.37 points higher) | MD 5.73 (‐2.91 to 14.37) | 401 (7) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝d Very low | The CI includes the putative MCID of 10 pointse in favour of surgery. Thus, this includes the possibility of a clinically important effect of surgery on outcome at two to nine years assessed using this score. |

|

Adverse effects of treatment Overall incidence of complications Follow‐up: less than two years |

277 per 1000b | 612 per 1000 (202 to 1000) |

RR 2.21 (0.73 to 6.66) |

144 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝f Very low | Surgery resulted in 335 more (95% CI 75 fewer to 723 more) people per 1000 having an adverse event during this time. |

|

Patient satisfactiona Reported as 'good' or 'excellent'. Follow‐up: two to nine years |

763 per 1000b | 770 per 1000 (564 to 1000) |

RR 1.01 (0.74 to 1.38) |

176 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝g Very low | Surgery resulted in 7 more (95% CI 199 fewer to 237 more) people per 1000 reporting a good or excellent outcome for satisfaction at this time. |

|

Patient‐reported knee instabilitya Incidence of patellar subluxation Follow‐up: two to nine years |

292 per 1000b | 219 per 1000 (146 to 327) |

RR 0.75 (0.50 to 1.12) |

256 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝h Very low | Surgery resulted in 73 fewer (95% CI 146 fewer to 35 more) people per 1000 reporting patellar subluxation at this time. |

|

Subsequent requirement for surgery (reoperations) for complicationsa Incidence Follow‐up: two to nine years |

215 per 1000b | 97 per 1000 (15 to 587) |

RR 0.45 (0.07 to 2.73) |

195 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝i Very low | Surgery resulted in 118 fewer (95% CI 200 fewer to 372 more) people per 1000 having subsequent surgery during this time. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MCID: minimal clinically important difference; MD: mean difference; MPFL: medial patellofemoral ligament; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aTrials in this analysis recruited only people with primary (first time) dislocation. bDerived from the pooled estimate in the non‐surgical group. cEvidence downgraded by three levels: one level for imprecision as fewer than 100 events were reported, and two levels for very serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias). dEvidence downgraded by three levels: two levels for serious risk of bias (selection, performance and detection bias) and one level for inconsistency as this pooled analysis exhibited statistical heterogeneity (I² = 90%). eWhilst the MCID for the Kujala score has yet to be determined for the patellar dislocation population, a change exceeding 10 points is regarded as clinically meaningful for the anterior knee pain population (Bennell 2000; Crossley 2004). fEvidence downgraded one level due to imprecision with fewer than 100 events reported, one level for risk of bias (due to high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias) and one level for inconsistency though statistical heterogeneity where this pooled analysis exhibited substantial heterogeneity (I² = 87%). gEvidence downgraded three levels: two levels due to serious risk of bias (selection, performance and detection bias) and one level for serious imprecision. hEvidence downgraded three levels: one level due to imprecision with fewer than 100 events reported, and two levels due to risk of bias (due to high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias). iEvidence downgraded three levels: one level due to imprecision with fewer than 100 events reported, two levels due to risk of bias (due to high risk of selection, performance, detection and attrition bias).

Background

This is an update of our Cochrane Review last published in 2015 (Smith 2015).

Description of the condition

Patellar dislocation occurs when the patella (kneecap) disengages completely from the trochlear (femoral) groove, typically to the lateral side when the femur rotates internally on the tibia with the foot fixed on the ground. The patella may spontaneously slip back into its original position, or require manual reduction to push it back into place. The term 'patellar instability' is used to include both patellar dislocation and subluxation (partial dislocation), or a feeling that the patella is unstable. As a result, these people often do not 'trust' their knee not to be unstable. This leads to activity modification and restriction as people try to avoid dislocations or instability. This restriction can range from everyday tasks such as walking, housework or shopping and everyday activities to more physical tasks such as sports and exercise, particularly activities involving twisting and changing direction (Smith 2011a). Accordingly, patellar dislocation and instability can have a significant impact on a person's quality of life.

When the patella dislocates laterally, injury occurs to the soft tissues of the medial aspect of the knee joint, particularly to the medial patellofemoral ligament (Thompson 2019). This predisposes to subsequent episodes of patellar dislocation or subluxation, and eventually to degenerative change in the knee joint. As well as injury of the medial capsular structures, a range of anatomical factors may predispose to patellar instability. These include variations of limb alignment, such as excessive valgus knee (Huntington 2020; Smith 2011b), or of architecture/geometry of the patella and lower femur, particularly of the trochlear groove, such as trochlear dysplasia (Huntington 2020; Thompson 2019), excessive lateral positioning of the attachment of the patellar tendon onto the shinbone (tibial tuberosity) or connective tissue laxity, such as benign joint hypermobility syndrome (Beasley 2004).

The term 'primary patellar dislocation' refers to the first time a person experiences a patellar dislocation. Its incidence is highest in young and physically active people in the second and third decades of life (Merchant 2007). The annual incidence of primary patellar dislocation has been estimated at 43 per 100,000 in children under 15 years (Nietosvaara 1994), with the incidence across all age groups much lower (estimated at seven per 100,000 by Atkin 2000). Females are more likely to be affected than males (Mitchell 2015). Women are frequently more hypermobile than men (Scher 2010). Females also have a different muscle/body mass ratio (Strugnell 2014), meaning they are more susceptible to injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament rupture and patellar dislocation (Hsiao 2010). Recurrent patellar dislocation can occur in 15% to 60% of primary dislocation cases (Martinez‐Cano 2021; Woo 1998).

Description of the intervention

Following reduction of the patellar dislocation, people frequently undergo non‐surgical treatment consisting of physiotherapy and rehabilitation (Beasley 2004; Moiz 2018). This may include treatments such as immobilisation and bracing to limit knee movement, exercises, manual therapy, taping and electrotherapeutic modalities (Moiz 2018). Non‐surgical management is frequently exercise‐based, with the aim being to restore neuro‐musculoskeletal control of the patellofemoral joint at the hip, knee, ankle and foot through strengthening and muscle recruitment exercises and activities (Smith 2011b). If muscles and soft‐tissues are tight or restricted in length, most commonly the hamstrings, quadriceps, gastrocnemius or iliotibial band/tensor fascia lata, targeted stretching exercises are prescribed (Smith 2010; Smith 2011b). Non‐surgical management is most frequently delivered by a physiotherapist (Smith 2010; Smith 2011b).

Some surgeons advocate surgical intervention for primary, or more frequently, recurrent dislocation (Donell 2006a; Thompson 2019). Such orthopaedic surgical interventions are of three main types.

Proximal patellar realignment soft tissue procedures. These are designed to repair or tighten the capsular soft tissues and tendinous soft tissues on the medial side of the knee (repair or medial plication) or reconstruct the ligamentous structures, particularly the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) to resist lateral displacement of the patella (Conlan 1993; Hautamaa 1998). If the lateral capsular soft tissues appear too tight, they may be incised (lateral release), but this is not recommended as an isolated procedure at present.

Distal patellar realignment procedures. This can include the tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) or Roux‐Goldthwaite procedures. In both instances, the surgeon alters where the patella attaches onto the tibia (Felli 2019). A TTO may be used where, most commonly, the patellar attachment is medialised (moved more centrally) and distalised (moved downwards) to correct abnormal patellar tracking in the distal femur (Cosgarea 2002; Dath 2006; Dejour 1994).

Osseous (bony) procedures. This includes a trochleoplasty where the surgeon constructs a groove in the femur for the patella to move within (Dejour 1994; Donell 2006b). This may also include femoral or tibial osteotomy for abnormal or excessive rotation of the tibia or femur.

These interventions may be performed separately or in combination. The choice of surgical intervention will be influenced by the specific anatomical abnormalities predisposing the individual to their instability problem (Thompson 2019). Physiotherapy rehabilitation is most often commenced following any of the above surgical interventions to rehabilitate people postoperatively (McGee 2017).

How the intervention might work

Non‐surgical ('conservative') treatments including physiotherapy aim to restore knee range of motion and improve patellar stability (Beasley 2004; Cosgarea 2002). It has been suggested that one principal cause of recurrent patellar dislocation is weakness of the vastus medialis, one of the four muscles forming the quadriceps (Dath 2006). By strengthening this muscle, it has been hypothesised that the patella will track more centrally in the trochlear groove, avoiding a more lateral position that may increase the likelihood of recurrent dislocation and instability symptoms (Donell 2006a). Similarly, strengthening muscle groups that control femoral internal rotation such as the glutaei muscle complex, has been suggested to reduce lateral patellar tracking through maintenance of femoral neutrality during activity (Donell 2006a; Smith 2010). Foot orthoses have also been recommended as a potential treatment adjunct, with the objective of controlling excessive tibial rotation, which may also influence patellar tracking through lateralisation of the patellar attachment on the tibia (Smith 2010). Finally, stretching shortened or tight soft tissues (such as of the hamstring, quadriceps, calf complex) through exercise or manual technique including mobilisation or massage, in addition to the lateral retinaculum/iliotibial band/tensor fascia lata, has also been proposed to reduce lateralisation of the patella within the patellofemoral joint (Smith 2010).

Surgical interventions, as described above, offer repair or reconstruction of soft tissues, or procedures to deepen the trochlear groove or to realign the patellar tendon, to stabilise the patella in a more medial position (Thompson 2019). The hypothesis is that by including an appropriate surgical procedure in addition to their postoperative rehabilitation programme, these interventions will be more effective than conservative treatment alone in reducing the recurrent instability that may substantially limit functional capabilities and quality of life.

Why it is important to do this review

Some authors have suggested that surgical interventions should be considered rather than physiotherapy alone (Boden 1997; Guhan 2009). Others have written that surgical interventions may be no better in preventing recurrent dislocation and functional restoration than non‐surgical approaches (Mears 2001; Nikku 1997). Determining the optimal management approach for this population is important for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is a high risk of recurrent patellar dislocation and instability symptoms if treatment is not effective. A second dislocation happens in around 40% of people within the first five years (Moiz 2018; Sanders 2018; Stefancin 2007). If a second (recurrent) dislocation occurs, ongoing restriction is highly likely and outcomes are poor (Liu 2018; Mäenpää 1997; Moiz 2018; Stefancin 2007). Secondly, there is a risk of cartilage lesions after repetitive subluxation and patellar dislocation (Salonen 2017). Repetitive injury of this nature can lead to early degenerative changes and osteoarthritis, resulting in long‐term pain and disability (Arendt 2016). Finally, patellar dislocation is more frequent in younger rather than older people (Huntington 2020; Merchant 2007). Ascertaining the most appropriate management strategy for this population is important to minimise the impact of this condition on their lifestyles and subsequent activities, and the impact of treatment for younger people could potentially have long‐lasting consequences.

The purpose of this systematic review is to inform clinical practice through the examination of the evidence from randomised trials comparing surgical to non‐surgical treatment approaches following patellar dislocation.

This is an update of our Cochrane Review last published in 2015, which identified five randomised studies and one quasi‐randomised study, including 344 people with primary (first‐time) patellar dislocation (Smith 2015). We found that, although there is some evidence to support surgical over non‐surgical management of primary patellar dislocation in the short term, the certainty of evidence was very low. We were very uncertain about the estimate of effect. We did not identify any trials that examined people with recurrent patellar dislocation. We concluded that adequately powered, multicentre, randomised controlled trials, conducted and reported to contemporary standards, were needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects (benefits and harms) of surgical versus non‐surgical interventions for treating people with primary or recurrent patellar dislocation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised (use of a method of allocating participants to a treatment that is not strictly random, e.g. by date of birth, hospital record number, alternation) controlled clinical trials (RCTs) evaluating surgical versus non‐surgical interventions for treating patellar dislocation (either primary or recurrent) were eligible.

Types of participants

Eligible participants were people of any age (adults or children) with a reported history of patellar dislocation, either primary or recurrent, recorded either as a historical account from a participant, or observed by a healthcare professional. We excluded trials that recruited participants who presented with anterior knee pain or patellar subluxation rather than a clear, convincing history or evidence of a patellar dislocation.

Types of interventions

Non‐surgical intervention, or conservative management, is the control intervention in this review. Non‐surgical treatment strategies following patellar dislocation include: a period of immobilisation, bracing or splinting, manual therapy, exercise‐based treatments, education and advice, electrotherapeutic modalities and taping techniques.

Surgical treatment strategies include the following.

Proximal patellar realignment soft tissue procedures such as medial reefing, lateral release, MPFL repair or reconstruction.

Distal patellar realignment procedures such as the TTO or a Roux‐Goldthwaite operation.

Osseous (bony) procedures such as trochleoplasty or femoral or tibial osteotomy.

Types of outcome measures

We assessed the clinical and radiological outcome measures described below.

Primary outcomes

Recurrent patellar dislocation.

Validated patient‐rated knee and physical function scores for patellar dislocation outcomes (Paxton 2003), e.g. the Lysholm score (Lysholm 1982), the Tegner activity score (Tegner 1985), the Hughston visual analogue score (VAS) (Flandry 1991), the Norwich Patellar Instability score (Smith 2014), the Banff‐II Patellar Instability Instrument (Hiemstra 2013) and the Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score (Kujala 1993).

We assessed these outcomes at three time points after treatment (short, medium and long term).

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life scores such as the EQ‐5D‐5L (Herdman 2011) and the Short Form‐12 (SF‐12) (Ware 1996).

Return to former activities: work and sports.

Knee pain during activity or at rest, as measured using a VAS or similar.

Adverse events (complications), e.g. deep or superficial infection, nerve palsy, allergies, rash or abrasion from taping or orthoses. These were assessed either as individual adverse events or as composite adverse event data.

Patient‐reported satisfaction such as measured with Likert scale, VAS or any other validated score.

Patient‐reported knee instability symptoms.

Subsequent requirement for knee surgery (reoperations) for complications such as infection, or mechanical instability.

These outcomes were assessed at each follow‐up time point presented within the included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update, we revised all our search strategies in line with the current Cochrane Bone Joint and Muscle Trauma Group practices. We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group's Specialised Register (15 December 2021)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) 15 December 2021, Issue 1)

MEDLINE Ovid (Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) (1946 to 15 December 2021)

Embase Ovid (1980 to 15 December 2021)

Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) (1985 to 15 December 2021)

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1981 to 15 December, Week 1, 2021)

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) (15 December 2021)

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (21 December 2021)

Clinicaltrials (21 December 2021)

There were no constraints based on language or publication status. The date of search was restricted from the date of the previous review (October 2014). Details of the previous search strategies are available in the previous review (Smith 2015).

In MEDLINE we combined a subject‐specific search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying RCTs in MEDLINE (sensitivity‐maximising version) (Lefebvre 2019). Details of search strategies for all databases are shown in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched conference proceedings from the British Orthopaedic Association Annual Congress, the British Trauma Society meetings, the European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology (EFORT) and the British Association for Surgery of the Knee (BASK) via the supplements of the Bone and Joint Journal (December Week 1 2021). We also searched bibliographies of relevant articles and contacted trial investigators in this area.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (TS and AG) independently selected the potentially eligible articles from citation titles and, if available, abstracts. Upon obtaining full articles, the same two authors independently performed the study selection. In cases of disagreement of paper inclusion/exclusion, a consensus was reached through discussion. Had that not been possible, we would have sought arbitration from a third author (CH).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (TS and AG) independently extracted data from trial reports. We contacted corresponding authors when key information was missing. In cases of disagreement, we sought consensus through discussion or adjudication by a third author (CH). After the individual review authors had extracted the relevant data, these were collated to form a single, agreed and completed data extraction form with all the included trial's characteristics and results. The template data extraction form is presented in Appendix 2. This collected all key trial data and participant information from the included articles.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (TS and AG) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials using Cochrane's risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). This consists of five domains: sequence generation (selection bias); allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding of participants, personnel (performance bias) and blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); selective reporting (reporting bias); as well as other risks of bias. We categorised risk of bias as low, unclear or high for each of the included trials. When no information was given by an included trial, we rated this domain as 'unclear' risk of bias. When differences between the ratings of the two assessors could not be resolved through discussion, we asked a third author (CH) to adjudicate.

Measures of treatment effect

We measured treatment effects using risk ratios (RR) for binary data and mean differences (MD) for continuous data. Should different scales or tools have been used to measure the same domain of a continuous outcome, we would have calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs). We used 95% confidence intervals (CI) throughout.

We categorised measurement of treatment effect time points as: short term (up to and including two years postrandomisation); medium term (over two years to less than 10 years postrandomisation); and long term (10 years or more postrandomisation). Where trials presented several follow‐up periods, we extracted and analysed data to inform short‐, medium‐ and long‐term results. Where authors reported multiple time points within the same time point category, we reported the later time point.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of randomisation in the majority of trials included in this review was the individual participant. Exceptionally, as in the case of trials including people with bilateral patellar dislocations, data for trials may be presented for dislocations or knees rather than for an individual person. Where such unit of analysis issues arose, and appropriate corrections were not made, we presented the data for such trials only when the disparity between the units of analysis and randomisation was small.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the corresponding study authors in respect of any missing key information from their publications. Where appropriate, we performed intention‐to‐treat analyses to include all people randomised to the intervention groups. We were alert to the potential mislabelling or misidentification of standard errors and standard deviations. Unless we could derive missing standard deviations from confidence interval data, we did not impute assumed values.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We appraised clinical diversity in terms of participants, interventions and outcomes for the included trials. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot and by using the I² statistic and Chi² test. The Chi² test was interpreted as demonstrating substantial heterogeneity where P was 0.10 or less. I² was interpreted where 0% to 40% indicated potentially unimportant statistical heterogeneity, 30% to 60% represented moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% represented substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100 represented considerable statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed outcome reporting bias by considering the data reported by trials against prospectively registered protocols. Where no prospectively registered protocol was available, we were unable to assess reporting biases. In the event that sufficient data were presented for a given outcome at a given time point (from at least 10 trials), we planned to assess publication bias using funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We considered clinical and methodological heterogeneity to determine whether it was appropriate to pool data in meta‐analysis. When judged appropriate, we pooled results from individual studies in meta‐analyses using fixed‐ or random‐effects models (depending on the results of heterogeneity tests), with 95% CI. We adopted a fixed‐effect model when there was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I² less than or equal to 30% and Chi² P > 0.01). We adopted a random‐effects model where there was no evidence of methodological diversity such as cohort, intervention or trial procedure, but statistical heterogeneity was evident that could not be readily explained (as denoted with an I² > 30% and Chi² P value equal to or less than 0.01). We were able to pool data in this review to determine short‐, medium‐ and long‐term outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We were unable to undertake all the planned formal subgroup analyses due to lack of studies. However, we were able to perform a formal subgroup analysis of males versus females. We made comparisons comparing results of participants under the age of 16 years following surgical and non‐surgical management.

Should data become available in a future update, we plan to carry out formal subgroup analyses to assess the difference in outcome between those who are hypermobile versus non‐hypermobile participants, in order to investigate whether this is an important prognostic variable in this patient group. We will also assess for a difference in outcome between different surgical treatments e.g. whether there is a difference in outcomes between repair versus reconstruction of MPFL. We also plan to undertaken formal subgroup analyses by participant age and primary versus recurrent patellar dislocation. We do not intend to analyse the effect of timing of surgery or conservative intervention in relation to the time since the participant's primary patellar dislocation.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses on the primary outcomes to examine the impact of including trials at high risk of bias due to lack of allocation concealment by analysing studies at low risk of selection bias (for allocation concealment). We planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis of trials where the population was poorly defined. However, this was not a limitation within the included trials so was not undertaken.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Two review authors (TS and AG) used the GRADE system to assess the certainty of the body of evidence associated with selected critical outcomes in the review. We did not construct summary of findings tables for all comparisons in this review. Instead, we summarised the evidence available for the two primary outcomes.

Recurrent patellar dislocation

Knee and physical function scores

We also summarised the evidence for four secondary outcome measures.

Incidence of complications (adverse effects of treatment)

Patient satisfaction

Patient‐reported knee instability (patellar subluxation)

Subsequent requirement for surgery

For these outcomes, we selected the follow‐up time point (short, medium or long term) for the outcome that provided the most substantial body of evidence. For knee and physical function scores, we reported the Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score in the summary of findings table because this provided the most substantial body of evidence.

We used the GRADE approach to determine the certainty of evidence for each outcome (very low, low, moderate or high), as recommended by Cochrane (Schünemann 2021). The GRADE approach assesses the certainty of a body of evidence based on the extent to which we can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. Evaluation of the certainty of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (study limitations), directness of the evidence (indirectness), heterogeneity of the data (inconsistency), precision of the effect estimates (imprecision), and risk of publication bias. The certainty of the evidence could be high, moderate, low or very low, being downgraded by one or two levels depending on the presence and extent of concerns in each of the five GRADE domains. We used footnotes to describe reasons for downgrading the certainty of the evidence for each outcome, and we used these judgements when drawing conclusions in the review. Of note, we assessed imprecision as occurring when fewer than 100 events were reported for a given analysis and/or where the confidence interval crossed both appreciable benefit and harm. We used GRADEpro GDT software to construct the summary of findings table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For this update we screened a total of 1712 records from the following databases: Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialised Register (15), CENTRAL (249), MEDLINE (410), Embase (783), AMED (23), CINAHL (105), PEDro (6), the WHO ICTRP (81), and ClinicalTrials.gov (40). Our searches of other resources, namely reference lists from potentially eligible and eligible papers, identified four additional studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria.

Once duplicates had been removed, we had a total of 1269 records. We excluded 1255 records based on titles and abstracts. We obtained the full text of the remaining 14 records and linked any references pertaining to the same study under a single study ID. Upon further analysis, we included four new studies (Askenberger 2018; Ji 2017; Rahman 2020; Regalado 2016). Including the previous six studies (Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009), 10 trials were eligible recruiting 519 participants. We excluded six new studies (Alvarez 2020; Kang 2017; Moström 2014; NCT02185001; Sillanpää 2011; Zheng 2019), and two were ongoing (Liebensteiner 2021; NCT02263807). No studies are awaiting classification. Studies excluded in the previous version of this review are reported in Smith 2015.

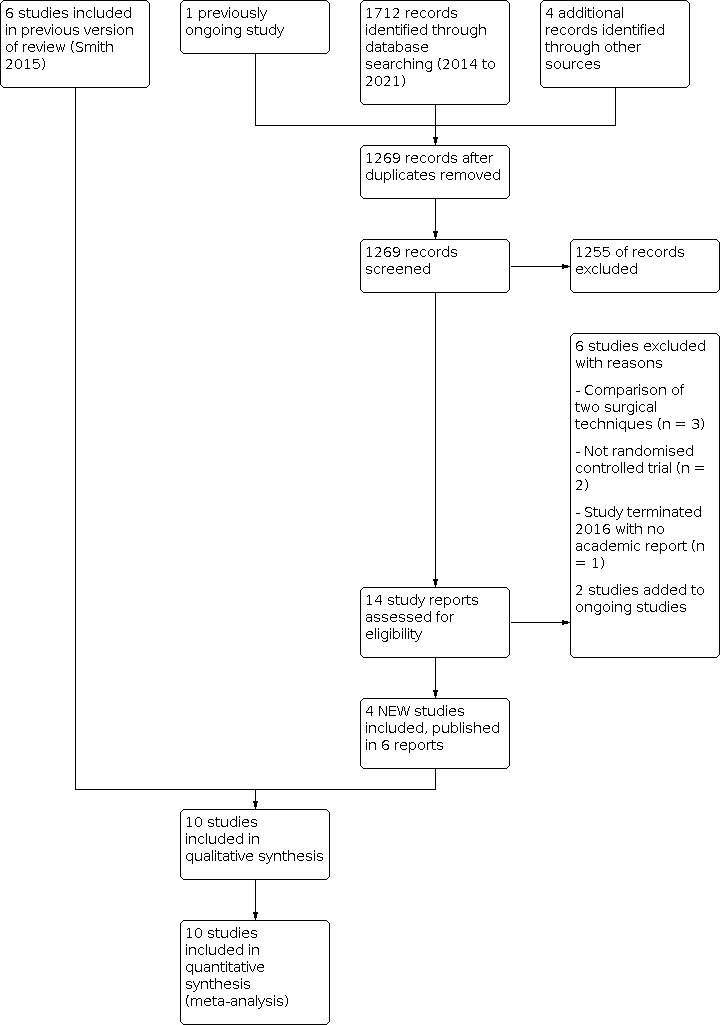

Further details of the process of screening and selecting trials for inclusion in the review are illustrated in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included 10 trials (recruiting 519 participants) published between 1997 and 2020. They were all written in English. Three trials were conducted in Finland (Nikku 1997; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009), two in Brazil (Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009), one in Germany (Petri 2013), one in Denmark (Christiansen 2008), one in Sweden (Askenberger 2018), one in China (Ji 2017) and one in the UK (Rahman 2020).

Randomisation procedure

Eight trials, including 344 participants, reported that they were randomised trials (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Petri 2013; Rahman 2020; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009), and two were quasi‐randomised by odd or even birth year (Nikku 1997; Ji 2017).

Participant demographic characteristics

Of the 500 participants for whom demographic data are available, 263 people (146 females and 117 males) were allocated surgery and 237 people (118 females and 119 males) were allocated non‐surgical intervention. The mean age in the surgery groups ranged from 13.2 years (Askenberger 2018) to 27.2 years (Petri 2013). The mean age in the non‐surgical groups ranged from 13.0 years (Askenberger 2018) to 24.6 years (Camanho 2009). Rahman 2020 did not report gender or age characteristics by group.

In the individual trials, the mean age ranged from 13.1 years in Askenberger 2018 to 26.0 years in Rahman 2020; and the percentage of females from 7.5% in Sillanpää 2009, which included military recruits, to 65.6% in Nikku 1997. Four trials included children, who were mainly adolescents, as well as adults (Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Nikku 1997). Askenberger 2018 and Regalado 2016 solely recruited children. The youngest participants were eight years old (Regalado 2016) and the oldest, who was an outlier, was 74 years old (Camanho 2009). Age was not reported in Ji 2017.

Nikku 1997 reported the outcomes of 127 knees in 125 participants, whilst Bitar 2012 reported the outcomes of 41 knees in 39 participants. In Bitar 2012, presenting trial data by patellar dislocation was unavoidable except for knee‐specific outcomes, such as the incidence of recurrent instability/dislocation. All remaining trials were analysed as one knee per person.

Four trials made reference to whether their participants presented with joint hypermobility (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Nikku 1997; Rahman 2020). Bitar 2012 reported that no patellar hypermobility was detected, and Nikku 1997 stated that one participant in each group presented with ligament laxity as assessed using the Beighton score (Carter 1964). Fourteen participants (38%) in the Askenberger 2018 non‐surgical group and 13 participants (35%) in their surgical group presented with Beighton scores of four and above to indicate joint hypermobility. Rahman 2020 reported that seven participants (38%) in their trial presented with joint hypermobility but did not present the breakdown of this by group allocation.

Patellar dislocation and eligibility criteria characteristics

Nine trials only recruited participants who had sustained primary patellar dislocation (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009). One trial only recruited participants who had experienced recurrent patellar dislocations (Rahman 2020).

The diagnosis of patellar dislocation was made during initial clinical examination within the trial, on the basis of a variety of different combinations of signs and symptoms. These inclusion criteria included: patellar dislocation requiring reduction in two trials (Christiansen 2008; Camanho 2009), a history of acute knee trauma in seven trials (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009), and intra‐articular haematoma, tenderness on the medial epicondyle and positive lateral patellar apprehension test results in Christiansen 2008 and Ji 2017. Magnetic resonance imaging was used as an eligibility criterion in four trials (Askenberger 2018; Ji 2017; Rahman 2020; Sillanpää 2009). All participants in four trials underwent arthroscopy to aid diagnosis (Askenberger 2018; Christiansen 2008; Petri 2013; Regalado 2016). The diagnosis of recurrent patellar dislocation in Rahman 2020 was a self‐reported experience of two or more lateral patellar dislocations or one dislocation with a minimum of six‐month history of subjective patellar instability leading up to the time of recruitment.

The main exclusion criteria were the presence (and/or requirement for surgical fixation) of a large osteochondral fracture presented in eight trials (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Rahman 2020; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009), an inability to follow up the planned treatment regimens in three trials (Bitar 2012; Christiansen 2008; Rahman 2020), prior knee surgery in five trials (Bitar 2012; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Regalado 2016) and a previously reported patellar dislocation or instability in nine trials (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009). Other exclusion criteria were the co‐existence of a significant tibiofemoral ligament injury requiring (or not) surgical fixation (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Ji 2017; Rahman 2020; Regalado 2016), people with conditions associated with serious neuromuscular or congenital diseases (Bitar 2012; Ji 2017), a history of a non‐traumatic event such as walking or squatting with 'moderate' stress on the knee and in the absence of acute pain in the knee (Bitar 2012), open growth plates (Rahman 2020), open injury (Petri 2013) or women who were pregnant or lactating (Petri 2013). Ji 2017 excluded people with patellofemoral dysplasia (Dejour B‐D) and patellar alta (Insall‐Salvati > 1.2) or a tibial tuberosity‐trochlear groove (TT‐TG) distance greater than 20 mm. Rahman 2020 excluded people with severe trochlear dysplasia or rotational coronal or sagittal malalignment of the femur or tibia, which in the opinion of the treating surgeon required surgical correction. Rahman 2020 also specifically excluded people with medial patellar dislocation.

Non‐surgical management

Non‐surgical management in nine trials consisted of initial immobilisation in a cast, splint or locked orthosis, followed by active mobilisation with physiotherapy. Rahman 2020 was the only trial not to use a form of immobilisation in their non‐surgical cohort, proceeding directly onto active mobilisation postrandomisation; this may be because they were the only trial studying recurrent rather than first‐time dislocation. There was variation in the duration of immobilisation and in components of the physiotherapy programmes (see Characteristics of included studies). This is summarised in Table 2. Whilst participants in four trials underwent arthroscopy prior to randomisation (Askenberger 2018; Christiansen 2008; Petri 2013; Regalado 2016), this was a diagnostic arthroscopic procedure and not a therapeutic arthroscopy. Of note in Sillanpää 2009, all participants in the non‐operative group received knee aspiration to relieve pain and four underwent arthroscopic removal of an osteochondral fragment. Similarly, Ji 2017 reported that arthroscopy surgery was performed to remove any loose bodies, if required. However, they did not report how frequently this was required. All these trials were included given the non‐corrective nature of these procedures.

1. Summary of non‐surgical management.

| Study | Knee brace/cast | Knee strength/ROM exercises | Initial FWB permitted | Initial PWB/NWB | Education/advice | Home exercise programme | Electric stimulation | Analgesia | Manual therapy | Care stability exercises | Cryotherapy | Muscle stretching exercises | CBT | Foot orthoses |

| Askenberger 2018 | 4 weeks | X | X | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bitar 2012 | 3 weeks | X | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | X | X | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Camanho 2009 | 3 weeks | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ |

| Christiansen 2008 | 2 weeks | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ji 2017 | 3 weeks | X | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nikku 1997 | 3 weeks | X | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Petri 2013 | 3 weeks | X | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Rahman 2020 | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | X | X | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | X | X |

| Regalado 2016 | 6 weeks | X | X | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Sillanpää 2009 | 6 weeks | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy treatment; FWB: full weight bearing; NWB: non‐weight bearing; PWB: partial weight bearing; ROM: range of motion

Surgical management

A summary of the surgical management interventions is presented in Table 3. The predominant operative intervention was repair or reconstruction of the soft tissues of the medial aspect of the knee joint. Four trials reported that all participants in their surgical groups solely underwent MPFL repair (Askenberger 2018; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017). This was an arthroscopic procedure in two trials (Askenberger 2018; Camanho 2009), and an open procedure in the other two trials (Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017). Nikku 1997 reported that all participants allocated to surgery in their trial received either a medial reefing with an MPFL augmentation using adductor magnus (six participants) or medial reefing with a lateral release (54 participants). Petri 2013 reported that their surgical intervention was repair of the medial soft tissues and a "MPFL‐plastic" procedure was not undertaken. Whilst they acknowledged that a lateral release was optional, they did not stipulate the frequency with which this procedure was undertaken. Sillanpää 2009 allocated 14 participants in the surgical group to receive a combined medial reefing procedure and MPFL suture repair, a Roux‐Goldwraithe (RG) procedure for four participants, and an arthroscopic repair was also required for an osteochondral fracture in six people. In Bitar 2012, the surgical procedure was an MPFL reconstruction using a medial slip of the patellar ligament, which was then sutured to the distal aspect of the vastus medialis muscle. Rahman 2020 did not report what specific surgical procedures were undertaken for their nine surgical participants. In Regalado 2016, surgical procedures were determined by clinical presentation against the Fulkerson classification (Fulkerson 1987). Through this, three participants with type I underwent lateral retinacula release (LLR); whilst 13 participants with a type II‐IV underwent a modified RG procedure (combination of proximal and distal realignment with LLR and medial imbrications).

2. Summary of surgical management.

| Study | MPFL repair | Medial reefing | Medial retinacula repair | MPFL reconstruction | Lateral release | modified Roux‐Goldwraite | Tibial tuberosity transfer | Osteochondral fracture repair |

| Askenberger 2018 | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bitar 2012 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Camanho 2009 | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Christiansen 2008 | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ji 2017 | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nikku 1997 | ‐ | X | X | X | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Petri 2013 | X | X | X | ‐ | X | ‐ | X | ‐ |

| Rahman 2020a | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Regalado 2016 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | X | X | ‐ | ‐ |

| Sillanpää 2009 | X | X | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | X | ‐ | X |

MPFL: medial patellofemoral ligament

aRahman 2020 did not specifically state what surgical interventions were performed.

All participants allocated to the surgical management strategies received a period of postoperative rehabilitation. With the exception of four trials (Askenberger 2018; Camanho 2009; Ji 2017; Rahman 2020), the postoperative rehabilitation programme used in each study was identical to that used in the non‐operative group. Camanho 2009 immobilised participants in their surgical group in an inguinal‐malleolar splint for three weeks, permitted their surgical patients to wear a movable immobiliser for three weeks and to commence passive knee range of motion exercises during this early postoperative period. Askenberger 2018 immobilised participants in a soft cast splint for four weeks following surgery. The subsequent physiotherapy programmes were the same. Ji 2017 immobilised their participants postsurgery in a knee brace in full knee extension for the first two postoperative days and then permitted knee flexion from zero to 90 degrees until four weeks postoperatively. In Rahman 2020, surgical participants underwent a similar programme of rehabilitation to their non‐surgical group, except that there was less focus on goal‐setting in the postsurgical intervention, with progress more closely dictated by surgical milestones for tissue healing.

Follow‐up time points and outcome measures

The shortest follow‐up period was 12 months (Rahman 2020). The maximum follow‐up was three years in two studies (Askenberger 2018; Christiansen 2008; Petri 2013). The mean follow‐up was 44 months (range 24 to 61 months) in Bitar 2012, and 42 months (range 24 to 54) in Ji 2017. Follow‐up in Camanho 2009 was after two years and before five years, the mean follow‐ups in the surgical and non‐surgical groups being 40.4 and 36.3 months, respectively. Nikku 1997 presented data at mean follow‐up periods of 25 months (range 20 to 45 months), seven years (range 5.7 to 9.1 years) and, for a subgroup of children only, 14 years (range 11 to 15 years), across three publications. Regalado 2016 reported their follow‐up data on children at six years. The median follow‐up was seven years, range six to nine years, in Sillanpää 2009.

Primary outcomes for review

All included trials provided data for our primary outcome of recurrent dislocation. Eight trials reported data on validated patient‐rated knee and physical function or activity scores. Eight trials reported the Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). Three trials reported the Tegner activity score (Askenberger 2018; Nikku 1997; Sillanpää 2009). Validated patient‐completed outcome measures included the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) (Christiansen 2008), the KOOS‐Child (Askenberger 2018), the Lysholm knee score (Nikku 1997), and the Hughston VAS knee score (Nikku 1997).

Secondary outcomes for review

Two trials reported other knee function and activities (Nikku 1997; Sillanpää 2009); return to former activities in one trial (Sillanpää 2009); knee pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS) in two trials (Nikku 1997; Sillanpää 2009); and adverse events relating to treatment in three trials (Nikku 1997; Rahman 2020; Regalado 2016). Participant satisfaction of outcome was reported in four trials (Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Regalado 2016). Askenberger 2018 assessed health‐related quality of life using the EQ‐5D‐Y (Wille 2010).

There was variation in the definitions used for 'instability'. Six trials reported the frequency of recurrent patellar subluxation (Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). Three studies reported the number of participants in each group who underwent subsequent surgery (Nikku 1997; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009).

Excluded studies

Studies excluded in the previous version of this review are reported in Smith 2015. In this review, we excluded six trials from the review (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We excluded three trials as they were not randomised or quasi‐randomised trials (Moström 2014; Sillanpää 2011; Zheng 2019), and two trials as some participants in the non‐surgical intervention received surgical interventions (Alvarez 2020; Kang 2017). We reclassified one trial, which was previously ongoing (NCT02185001), as excluded as it was terminated with no results presented.

Ongoing studies

Two trials are ongoing (Liebensteiner 2021; NCT02263807). Liebensteiner 2021 is an RCT being conducted in Austria and Germany, assessing outcomes of a tailored surgical approach to non‐surgical (bracing and physiotherapy) management for primary patellar dislocation. The surgical intervention is tailored to address the pathologic anatomy that predisposes participants to lateral patellar dislocation. Therefore, all participants randomised to this group will receive an MPFL reconstruction with or without trochleoplasty, tibial tuberosity transfer, derotational osteotomy, or varus osteotomy. The follow‐up period for the planned 160 participants is 24 months. NCT02263807 is an RCT taking place in Norway, comparing outcomes of surgical (MPFL reconstruction) with non‐surgical (physiotherapy) management for recurrent patellar dislocation. The follow‐up period for the planned 70 participants is 36 months. The trial commenced in 2010. At the last update, 75 participants had been enrolled.

Risk of bias in included studies

Our judgements of the risk of bias in the 10 included trials are summarised in the risk of bias graph (Figure 2) and the risk of bias summary (Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

We judged two trials as being of low risk of selection bias (Petri 2013; Rahman 2020). This reflected the use of a computer‐generated randomisation sequence and sealed envelopes (Petri 2013), and computer‐generated randomisation through a telephone system (Rahman 2020). The quasi‐randomised trials of Nikku 1997 and Ji 2017, which allocated treatment according to year of birth, were assessed as being of high risk of selection bias relating to inadequate sequence generation and lack of allocation concealment. We assessed the other six trials as unclear risk of selection bias from sequence generation, which reflected inadequate information on randomisation methods (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009). Bitar 2012 and Camanho 2009 probably used the same method involving drawing of a slip of paper specifying the treatment. Three trials referred to randomisation using a sealed envelope approach to minimise selection bias (Askenberger 2018; Christiansen 2008Sillanpaa 2009). However, no details were reported on adequate safeguards to ensure that allocation concealment were ensured throughout, hence we classified these as unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

No trials blinded their assessors to treatment allocation. Due to the design of these trials and the topic under investigation, it would have been very difficult, if not impossible, to blind treating clinicians to treatment allocation, or participants to their allocation intervention. We assessed all trials as being of high risk of performance and detection bias relating to lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged one trial as being of high risk of attrition bias as the numbers of participants lost to follow‐up differed between the groups where five non‐surgical and one surgical participant were lost to follow‐up (Regalado 2016). We considered eight trials as being of low risk of bias (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). Small losses to follow‐up were reported in five trials (Bitar 2012; Christiansen 2008; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). There were no losses reported in Camanho 2009. Four trials reported reasons for their missing participants, which we considered adequate (Askenberger 2018; Ji 2017; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). One trial was at unclear risk as the reason for attrition was not clear, and seven participants were missing from the analysis at the six‐month time point (Rahman 2020). Only Bitar 2012 confirmed that the data were analysed according to intention‐to‐treat principles.

Selective reporting

No protocols or prospective trial registration documents were available for eight trials. Two trials provided ISRCTN trial registration numbers (Askenberger 2018; Rahman 2020). Although all the planned outcomes defined in the methods section were reported in the results sections of the included trials, we judged seven trials not reporting adverse effects of surgery as having high risk of selective reporting bias (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). Two trials reported adverse events and therefore we judged them as being at low risk of selective reporting (Nikku 1997; Regalado 2016). Rahman 2020 presented adverse events but did not present the outcomes of their cohort by allocated group, and therefore were assessed as being of unclear risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We identified no other sources of bias in the included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Recurrent dislocation

All 10 trials reported the frequency of recurrent dislocation after surgery compared with non‐surgical interventions. Data for this outcome are presented for each follow‐up period; see Analysis 1.1; Figure 4.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 1: Number of participants sustaining recurrent patellar dislocation

4.

Forest plot of comparison 1. Surgical versus non‐surgical management. Outcome: 1.1 Number of participants sustaining recurrent patellar dislocation

Pooled data from two trials showed little difference between the surgical and non‐surgical groups at short‐term follow‐up (Ji 2017; Rahman 2020) (2/39 versus 4/36; risk ratio (RR) 0.48 favouring surgery, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.10 to 2.38; 2 studies, 75 participants). This finding is consistent compared to participants with recurrent dislocation events alone prior to randomisation in Rahman 2020 (1/9 versus 1/10; RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.08 to 15.28; 19 participants). Pooled data from eight trials showed a smaller incidence of recurrent dislocation at medium‐term follow‐up in the surgical group (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Regalado 2016; Sillanpää 2009) (44/231 versus 72/207; RR 0.55 favouring surgery, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.75; 8 studies, 438 participants). This trend was consistent compared to an analysis involving children only in Askenberger 2018 and Regalado 2016 (13/52 versus 27/52; RR 0.48 favouring surgery, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.82; 2 studies, 110 participants; data not shown). There was little difference between surgical and non‐surgical groups at long‐term follow‐up (24/36 versus 20/28; RR 0.93 favouring surgery, 95 CI 0.67 to 1.30; 1 study, 64 participants). For these outcomes, using GRADE criteria, we downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; one level for imprecision as fewer than 100 events were reported, and two levels for very serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias).

Sensitivity analysis

Only two studies were at low risk of selection bias (for allocation concealment), one of which reported short‐term data (Rahman 2020), and one of which reported medium‐term data (Petri 2013). The findings from Rahman 2020 were consistent with the pooled result for short‐term data in Analysis 1.1 (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.08 to 15.28; 1 study, 19 participants). However, the result in Petri 2013 indicated little or no difference in recurrent patellar dislocation in the medium term (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.09; 1 study 20 participants), and this differed from our interpretation of the primary pooled analysis.

Validated patient‐rated knee and physical function scores for patellar dislocation outcomes

Three trials reported the Tegner activity score (0 to 10: higher values indicate improved outcome) (Askenberger 2018; Nikku 1997; Sillanpää 2009) (Analysis 1.2). Pooled data from these trials showed little difference between the groups at short‐term follow‐up (MD ‐0.56 favouring non‐surgery, 95% CI ‐1.08 to ‐0.04; 190 participants). This finding was the same for a subgroup involving children only in the Askenberger 2018 study (MD ‐0.50 favouring non‐surgery, 95% CI ‐1.33 to 0.33; 65 participants). This is consistent at medium‐term follow‐up (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐1.15 to 1.15; 1 study, 40 participants); and, for children only, at long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐1.60 favouring non‐surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐2.44 to ‐0.76; 1 study, 64 participants). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; one level due to imprecision where the CIs include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm, and two levels for very serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance and detection bias and risk of selection bias in Nikku 1997).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 2: Tegner activity score (0 to 10: best score)

The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) (0 to 10 for total score: higher values indicate improved outcome) was assessed by Askenberger 2018 and Christiansen 2008 (Analysis 1.3). There was little difference between surgical and non‐surgical intervention groups at short‐term follow‐up in the KOOS subsections: symptoms (MD ‐3.35, 95% CI ‐11.09 to 4.39; 2 studies, 145 participants), pain (MD ‐1.01, 95% CI ‐10.18 to 8.15; 2 studies, 145 participants), activities of daily living (ADL) (MD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐7.96 to 7.33; 2 studies, 145 participants), sports and recreation (MD ‐4.64, 95% CI ‐21.85 to 12.57; 2 studies, 145 participants) or quality of life (MD ‐4.14, 95% CI ‐18.69 to 10.41; 2 studies, 145 participants). The results from this analysis are presented in Analysis 1.3. However, for an analysis involving children only (Askenberger 2018), participants reported better outcomes in the non‐surgical group in symptoms (MD ‐7.20, 95% CI ‐14.21 to ‐0.19; 68 participants), sports and recreation (MD ‐14.00, 95% CI ‐24.06 to ‐3.94; 68 participants) and quality of life (MD ‐12.20, 95% CI ‐21.56 to ‐2.84; 68 participants). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; one level for serious risk of bias (performance and detection bias) and two levels for serious imprecision where the CIs include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 3: KOOS (0 to 100: best outcome) at short term follow‐up

Nikku 1997 found no significant difference between the two groups in the Lysholm knee score (0 to 100: higher values indicate improved outcome) at short‐term follow‐up (MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐4.63 to 2.63; 125 participants; Analysis 1.4). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; one level due to imprecision where the CIs include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm, and two levels for very serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance and detection bias and risk of selection bias).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 4: Lysholm score (0 to 100: best score) at short‐term follow‐up

Similarly Nikku 1997 reported the Hughston visual analogue scale (VAS) patellofemoral scores (28 to 100: higher values indicate improved outcome) (Analysis 1.5). At short‐term follow‐up there was no difference between the groups in these scores (MD ‐2.80, 95% CI ‐6.70 to 1.10; 125 participants; Analysis 1.5). At a medium‐term follow‐up in Nikku 1997, this remained the same (medians (interquartile range) surgical: 89 (74 to 95) versus non‐surgical: 94 (84 to 96); reported P value = 0.08). For an analysis of children only at long‐term follow‐up, reported scores favoured non‐surgical management (MD ‐7.00, 95% CI ‐13.95 to ‐0.05; 1 study, 64 participants; Analysis 1.5). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; two levels due to very serious risk of bias (selection, performance and detection bias) and one level due to imprecision with fewer than 100 events reported.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 5: Hughston VAS patellofemoral score (28 to 100: best outcome)

The Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score (0 to 100: higher values indicate improved outcome) was evaluated in eight trials (Askenberger 2018; Bitar 2012; Camanho 2009; Christiansen 2008; Ji 2017; Nikku 1997; Petri 2013; Sillanpää 2009). Data for this outcome are presented at short‐term, medium‐term and long‐term follow‐up periods (Analysis 1.6; Figure 5). At short‐term follow‐up, Ji 2017 found higher Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders scores in the surgical group (MD 13.38 favouring surgical treatment, 95% CI 10.96 to 15.80; 1 study, 56 participants). Pooled data from seven trials showed no difference between the surgical and non‐surgical groups at medium‐term follow‐up (MD 5.73 favouring surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐2.91 to 14.37; 7 studies, 401 participants; Analysis 1.6). When assessed as adult participants alone, there was no difference between the treatments at medium term follow‐up (MD 7.99 favouring surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐6.27 to 8.27; 5 studies, 318 participants). However, when the analysis was compared to a children‐only analysis, non‐surgical treatment offered favourable outcomes (MD ‐5.79 favouring non‐surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐9.38 to ‐2.19; 2 studies, 190 participants). Although based on data for people with anterior knee pain, this result does not reach a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 10 points (Bennell 2000; Crossley 2004). For an analysis including children only, data from one trial showed no difference between surgical and non‐surgical groups at long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐1.00 favouring non‐surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐8.60 to 6.60; 1 study, 64 participants; Analysis 1.6). For the medium‐term follow‐up of this outcome, we downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; two levels for very serious risk of bias (selection, performance and detection bias) and one level for inconsistency as this pooled analysis exhibited statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 60.48, df = 6 (P < 0.0001), I² = 90%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 6: Kujala patellofemoral disorders score (0 to 100: best outcome)

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Surgical versus non‐surgical management, outcome: 1.6 Kujala patellofemoral disorders score (0 to 100: best outcome)

Nikku 1997 conducted performance tests at short‐term (mean of two years) follow‐up consisting of timed 'figure‐of‐eight' running, one‐leg hop distance and maximum number of squat downs in one minute. There were insufficient data provided to calculate effect estimates. Study authors reported significantly better squat results (P = 0.03) and superior timed 'figure‐of‐eight' run performance (P = 0.004) in the non‐surgical group compared with the surgery group. They reported no significant difference in one‐leg hop quotient between the interventions (P = 0.8). Patient‐reported outcomes of activity level were evaluated in Sillanpää 2009. There were insufficient data provided to calculate effect estimates. They reported that there was no statistically significant difference between group differences in the subjective assessment of functional knee limitations for stairs, running and squatting (P > 0.05). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence: one level for imprecision where the CIs included both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm, and two levels for very serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance and detection bias and risk of selection bias).

Sensitivity analysis

One study had low risk of selection bias (Petri 2013). This reported no difference between the surgical and non‐surgical groups for Kujala Patellofemoral Disorders score at two year follow‐up (MD 6.20 favouring surgery, 95% CI ‐9.09 to 21.49; 20 participants).

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL)

Data for an analysis of children only in Askenberger 2018 showed little difference between surgical and non‐surgical groups at short‐term follow‐up (MD 1.70 favouring surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐6.60 to 10.00; 1 study, 67 participants; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 7: Health‐related quality of life

Return to former activities: work and sports

Sillanpää 2009 reported little between‐group difference in the frequency of participants who regained the same activity level as before their dislocation at the medium‐term follow‐up (13/17 versus 15/21; RR 1.07 favouring surgery, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.56; 1 study, 38 participants; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 8: Return to former activities: work and sports

Knee pain during activity or at rest

Two trials assessed knee pain using a VAS, one at short‐term (Nikku 1997), and the other at medium‐term follow‐up (Sillanpää 2009) (Analysis 1.9). Neither found a significant difference between treatment groups. The results for Nikku 1997 were: MD 0.20 favouring non‐surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.69; 125 participants. The results for Sillanpää 2009 were: MD 0.50 favouring non‐surgical treatment, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 1.28; 38 participants. We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence; two levels due to very serious risk of bias (selection, performance and detection bias) and one level for serious imprecision with the CIs including both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 9: Knee pain (VAS 0 to 10: worst outcome)

Adverse events of interventions

Three trials reported on adverse events of treatment (Nikku 1997; Rahman 2020; Regalado 2016). Overall complications were reported in all three trials at two time points: two studies at short‐term and one study at medium‐term follow‐up (Analysis 1.10). Pooled data show there was greater incidence of complications in the surgical group at short‐term follow‐up period (63/79 versus 18/65, RR 2.21 favouring non‐surgical treatment, 95% CI 0.73 to 6.66; 2 studies, 144 participants). An analysis of only those who were recruited after recurrent patellar dislocation and instability showed that there was little difference between the groups at short‐term follow‐up (7/9 versus 6/10, RR 1.30 favouring non‐surgical; 95% CI 0.70 to 2.40; 1 study, 19 participants). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence: one level for imprecision with fewer than 100 events reported, two levels due to very serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance, detection and attrition bias), and inconsistency though statistical heterogeneity where the pooled analysis for short‐term follow‐up exhibited some heterogeneity (Chi² = 7.60, df = 1 (P = 0.006), I² = 87%). For a children‐only analysis in Regalado 2016, there was a higher incidence of overall complications in the surgical group at medium‐term follow‐up (3/16 versus 0/20; RR 8.65 favouring non‐surgical, 95% CI 0.48 to 156.11; 1 study, 36 participants). We downgraded the certainty of evidence three levels to very low‐certainty evidence: two levels for imprecision with fewer than 100 events reported, and one level due to serious risk of bias (due to high risk of performance and detection bias).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Surgical versus non‐surgical management, Outcome 10: Number of complications: overall complications