Abstract

Huntington’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by mutation of the huntingtin (HTT) gene. The identification of mutation carriers before symptom onset provides an opportunity to intervene in the early stage of the disease course. Optimal biomarkers are of great value to reflect neuropathological and clinical progression and are sensitive to potential disease-modifying treatments. Blood-based biomarkers have the merits of minimal invasiveness, low cost, easy accessibility and safety. In this review, we summarized the updated development of blood-based biomarkers for HD from six aspects, including neuronal injuries, oxidative stress, endocrine functions, immune reactions, metabolism and differentially expressed miRNAs. The blood-based biomarkers presented and discussed in this review were close to clinical applicability and might facilitate clinical design as surrogate endpoints. Exploration and validation of robust blood-based biomarkers require further standard and systemic study design in the future.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, Blood based, Peripheral, Biomarkers

Background

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a monogenic neurodegenerative disease with age-dependent progression, characterized by chronic progressive involuntary chorea, motor difficulties, cognitive impairment, and psychiatric symptoms [1–3]. HD has an incidence of 10.6–13.7 per 100,000 individuals in western populations and has shown an increasing trend in the past two decades [2, 4, 5]. The cause of HD is cytosine–adenine–guanine (CAG) repeat expansion in the first exon of the HTT gene on chromosome 4, which codes for polyglutamine in the huntingtin protein (HTT) [6, 7] and mainly affects the striatum and cortex with neuropathological progression [2]. The length of expansion is inversely correlated with HD motor symptom onset in the majority, and more than 35 repeat expansions are typically pathogenic [8], although mutation carriers with 36–39 CAG repeats confer lower penetrance because the estimated disease onset is beyond the normal life span [7, 9]. Individuals with pathogenic mutation can be detected by predictive gene testing before developing clinical symptoms. There is currently no effective disease-modifying treatment [10, 11] and death normally occurs in 15–20 years after motor symptoms appear [1]. However, the premanifest period of HD provides a natural suitable opportunity to investigate potential effective interventions to delay the progression of HD before symptoms appear; hence, robust and sensitive biomarkers to reflect or even predict pathogenic and clinical progression, monitor patients’ responses to the treatment are warranted for HD.

Biomarkers can be defined as objectively measured indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention [12, 13] and are typically classified as clinical biomarkers, imaging biomarkers and biofluid biomarkers [12, 14]. Ideal biomarkers are supposed to (1) be readily accessible and reproducible, (2) predict disease onset, reflect pathogenic and clinical progression and respond to therapeutic interventions as surrogate endpoints in clinical trials, and (3) not be easily disrupted by other comorbidities or the external environment. The Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS), a widely used scale to evaluate the severity of clinical symptoms of HD, is easy, inexpensive, and safe to perform and can directly indicate the severity of HD [15]. However, premanifest mutation carriers show no obvious clinical signs, and even for patients in the early manifest period, the changes in clinical symptoms are relatively slow and insensitive [16, 17], which may raise difficulties to observe significant clinical improvements in the course of clinical trials, especially for those trials aimed at premanifest individuals. Additionally, clinical assessments may also be affected by placebo effects and the subjective factors of different researchers and environments [16]. Neuroimaging biomarkers have the advantages of non-invasiveness, uniform standards, and accessibility. Striatal atrophy detected by MRI scan is regarded as the most sensitive, robust, and undisrupted imaging biomarkers for HD [14, 18–20]. However, neuroimaging techniques such as MRI and PET–CT are expensive and inconvenient, and involuntary movements of patients may affect the quality of the images [16].

The identification of optimal biochemical biomarkers is promising for tracking HD clinical and neuropathological progression and evaluating responses to interventions [14]. Biochemical biomarkers have been reported extensively in many cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, including the large-cohort studies PREDICT-HD [21] and TRACK-HD [22, 23]. Biofluid biomarkers derived mainly from CSF and blood can reflect disease pathogenic processes at the molecular level directly and might unravel the potential pathogenesis of HD [7]. For example, mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT) possibly plays a central and critical role in pathogenic processes of HD and the current exploration of HD therapeutics has shifted towards targeting the pathogenic mutation and aimed to intervene at the RNA and DNA levels to lower huntingtin allele [7, 10]. Clinical trials of RNA-targeting approaches including anti-sense oligonucleotide (ASO) [24], RNA interference (RNAi) [25] and adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated gene therapies [26, 27] or preclinical DNA-targeting investigations including zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) [28], CRISPR/Cas9 [29] and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [30] all provided new hope for the development of effective treatment for HD. In the meanwhile, this emphasized the potential significance of biofluid biomarkers, especially referring to mHTT, to reflect responses to HTT-lowering treatments and act as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials of HD now and in the future. CSF with a high content of specific proteins related to brain pathology is appealing, but it is limited by the invasive method of sample collection compared with peripheral blood-based biomarkers. The blood-based biomarkers for HD have the advantages of minimal invasiveness, economic affordability, easy accessibility and safety. In this review, we focused more on proposed blood-based biomarkers and mainly summarized the updated development of promising blood-based biomarkers from the perspectives of various pathogenic processes involved in HD.

Main pathogenic processes of Huntington’s disease

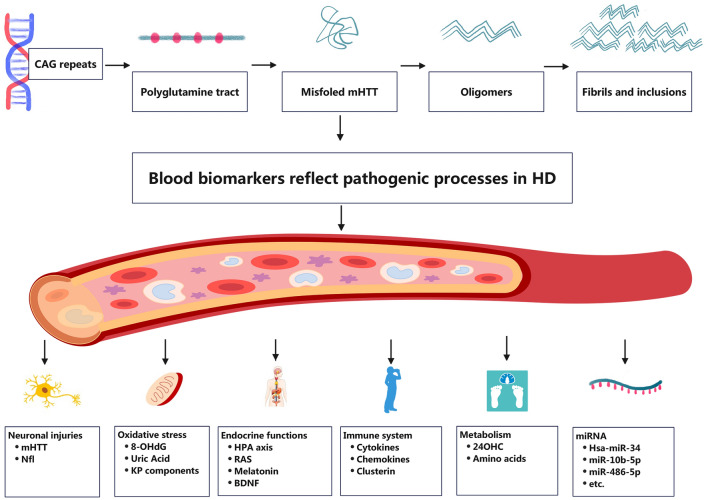

Although HD is considered a monogenetic disease [6], the biochemical molecules related to its pathophysiological processes are extensive and complicated [7]. The blood-based biomarkers are supposed to detect the peripheral pathophysiologic changes of HD directly, or hopefully, even to reflect the parallel central neuropathogenic processes to some extent. We would briefly introduce the current understanding of the central and peripheral pathogenesis underlying HD in this section before introducing the blood-based biomarkers of HD (shown in Fig. 1). HD is inherently caused by expansion of the CAG repeat in the first exon of the HTT. The pathogenic cascade of HD possibly arises from a gain of toxic function of mHTT to a large extent and a loss of function of wild-type protein and toxic RNA were also proposed to contribute to the pathogenesis in HD. The abnormal polyglutamine tract in the mHTT disrupts the normal posttranscriptional modification process of HTT [31], stimulating the misfolding of the protein and producing pathogenic oligomers and inclusions. However, the protective or toxic role of inclusions in HD is still under investigation [7, 32]. Full-length mHTT may also be cleaved by various proteases into N-terminal fragments with increased toxicity [33].

Fig. 1.

The current understanding of pathogenesis underlying HD and its related blood-based biochemical biomarkers

Widespread transcriptional dysregulation is the dominant pathogenic change in HD [7, 34]. mHTT interferes with normal translational processes, resulting in extensive degeneration to the brain, mainly striatal medium spiny neurons, in the early period [35]. Evidence also indicated that mHTT disrupted normal mitochondrial functions through various mechanisms including abnormal binding with the mitochondrial membrane, aberrant organellar axonal transport and decreased transcription of mitochondrial genes, which leads to abnormal energy metabolism and oxidative stress [36, 37]. Activated inflammatory response is considered not only a reactive process to other primary lesion, but also an active and critical pathogenic process in HD, as in other neurodegenerative diseases [38, 39]. mHTT expressed in immune cells was observed to promote autonomous microglia activation in the central nervous system(CNS) and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in the peripheral circulatory system [40].

Abnormal DNA repair mechanisms is considered central to the pathogenesis of HD [7] and somatic instability is a prominent characteristic of HD [7, 41–43]. Expanded CAG repeat undergoes progressive length increase over the course of life in an age-dependent and tissue-specific process [41, 44]. The degree of somatic instability varies in different tissues [7, 45] and possibly contributes to the cell- and region-selective property of HD [42, 46]. The most prominent somatic instability appears to occur within the striatum and cortex that show the most neuropathological involvement [42, 47]. The previous study using the method of mathematical model and computer simulation proposed the hypothesis that the onset of disease depends on the somatic expansion beyond a certain threshold in a sufficient number of vulnerable cells, and disease progresses as more and more cells involve [48]. Growing evidence also suggests that somatic repeat explains disease onset better than the length of the inherited allele, highlighting the critical role of somatic instability in the pathogenesis [49, 50].

Beyond the relatively well-established mechanisms of HD pathogenesis in the CNS, growing evidence validates that peripheral tissues are also involved in HD [51, 52]. mHTT can be ubiquitously expressed beyond the CNS, resulting in peripheral pathophysiological changes [51], and previous studies have observed systemic manifestations of peripheral tissues in HD patients including systemic metabolic dysfunction, weight loss, endocrine disturbances, cardiac failure, etc [7]. HD is gradually regarded as a systemic whole-organism disease [53]. Growing investigations have been performed to explore the effect of some peripherally administered targeting therapeutics which may be expected to elicit systemic effects [54], emphasizing the value of exploring blood-based biomarkers for HD.

Neuronal injury and death biomarkers (Table 1)

Table 1.

Summarization of previous studies on biomarkers of neuronal injuries in HD patients

| Biomarker | Study | Sample size (N) | Findings | Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHTT | Weiss et al. 2009 [56] | 9 (5HD, 4C) | HD > C | TR-FRET | Whole blood, red blood cells, and buffy coat |

| Moscovitch-Lopatin et al. 2010 [57] | 38 (38HD, 8C) | HD > C | HTRF | Buffy coat | |

| Weiss et al. 2012 [60] | 38 (18HD, 8PreHD, 12C) | HD > PreHD, HD > C | TR-FRET | Leukocytes | |

| Corr disease burden and caudate atrophy | |||||

| Moscovitch-Lopatin et al. 2013 [58] | 342 (114HD, 228C) | HD > C | HTRF | PBMCs | |

| Corr predicted time to onset | |||||

| Wild et al. 2015 [63] | 52 (39HD, 13C) | No corr with CSF mHTT level | SMC immunoassay | Plasma | |

| Hensman et al. 2017 [59] | 133 (43HD, 37PreHD, 53HD) | HD > PreHD > C | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassays | PBMCs | |

| Corr clinical stages | |||||

| Nfl | Byrne et al. 2017 [74] | 298 (201HD, 97C) |

HD > PreHD > C Corr clinical stages, cognitive functions, MRI findings and CSF Nfl level |

Ultrasensitive SIMOA | Plasma |

| Johnson et al. 2018 [77] | 198 (94HD, 104PreHD) | Corr gray matter and white matter atrophy | Ultrasensitive SIMOA | Plasma | |

|

Byrne et al. 2018 [62] Rodrigues et al. 2020 [61] |

80 (40HD, 20PreHD, 20C) |

HD > PreHD > C Corr clinical progression and MRI findings |

Ultrasensitive SIMOA | Plasma | |

| Scahill et al. 2020 [81] | 131 (64PreHD, 67C) | PreHD > C | Ultrasensitive SIMOA | Plasma | |

| Corr predicted clinical onset | |||||

| Byrne et al. 2022 [80] | 138 (11JOHD, 44PreHD, 83C) |

HD > PreHD > C Corr caudate and putamen volumes |

Ultrasensitive SIMOA | Plasma |

mHTT mutant huntingtin protein, Nfl neurofilament light protein, HTRF homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence, TR-FRET time-resolved Förster resonance energy transfer, SMC single molecule counting, SIMOA single-molecule array, HD Huntington’s disease, PreHD premanifest HD, C controls, JOHD Juvenile-onset HD, Corr correlate with, PBMCs peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT)

mHTT plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of HD [2, 7] and induces various pathogenic changes as stated above, leading to neuronal injury and death [55]. Considering predominant intracellular location of mHTT, the detection and quantification of soluble mHTT is quite challenging, especially referring to blood-based mHTT compared to CSF mHTT. Nevertheless, the value of blood-based mHTT as biomarkers has been explored preliminarily using novel and ultra-sensitive assays. Since Weiss et al. first detected soluble mHTT in the whole blood, erythrocytes and buffy coats using the method of a highly sensitive time-resolved Förster resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) and preliminarily validated increase mHTT levels in these blood-based samples comparing HD patients to controls in a small sample [56], growing study further validated that the detection of mHTT in HD patients is highly sensitive and technically and biologically reproducible using the method of Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence, TR-FRET and electrochemiluminescence immunoassays in the blood-based samples (buffy coats [57], peripheral blood mononuclear cells [58, 59], other immune cells [60]).

However, even though the quantification of blood-based mHTT is a reliable technically, it is important for a biochemical biomarker to predict the clinical onset of symptoms or reflect the progression of clinical manifestations. Weiss et al. first observed the association between blood-based mHTT levels [60] and the disease burden scores and caudate atrophy rates in patients with HD. Subsequent studies found that normalized mHTT level was associated with advancing disease stage [59] and the predicted time to onset or to phenoconversion [58]. The current evidence indeed indicates that peripheral mHTT levels can also partially reflect clinical manifestations induced by central pathogenesis, although the underlying mechanisms have not been clarified clearly. One possible explanation is that blood-based mHTT level just reflects the natural history of HD and peripheral pathogenesis is in a parallel with what occurred in the CNS to some extent, resulting in the observed clinical associations. Another hypothesis proposed by Chuang et al. suggested that HD pathogenesis in the brain is influenced by signals from peripheral tissues via the bloodstream and a leaky blood brain barrier [51]. Overall, studies regarding mHTT in peripheral circulation are still limited compared to CSF. The CSF mHTT level seems to be more appealing and promising in reflecting neuropathological and clinical progression and predicting clinical onset as a biofluid biomarker [61–63].

Huntington lower strategies have been the main focus for disease-modifying therapy studies of HD [10]. Investigators aimed to suppress the expression and functions of mHTT by targeting HTT [64, 65], HTT RNA [24] or mHTT [66, 67] directly and blocking the downstream pathogenic changes driven by gain-of-function of mHTT. The value of mHTT levels as pharmacodynamic marker or even surrogate endpoints in clinical trials is explicit. The CSF mHTT level has been used as outcome measures in clinical trials of tominersen, the first ASO targeting HTT mRNA administered to humans [11]. Compared to CSF mHTT, blood-based mHTT is less useful as pharmacodynamic biomarker in those centrally acting therapies as there is no evidence of mHTT lowering in the periphery, but not in the peripherally administered therapeutics. Blood-based mHTT could be used to monitor mHTT-lowering therapies that may be expected to elicit systemic effects. For example, branaplam, an orally available and brain penetrant small molecule splicing modulator with broad CNS and systemic distribution, was validated to successfully lowering the transcription of HTT gene using human blood samples [54]. The phase II clinical trial of branaplam used concentrations of total HTT and mHTT protein in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells as secondary outcome measures (NCT05111249). PIVOT-HD study of another orally administered small molecule splicing modulator PTC518 also used blood total HTT and mHTT as outcome measures (NCT05358717). The value of blood-based mHTT as a biomarker for evaluating the effects of potential treatments and its association with CSF mHTT deserves further well-designed investigation.

Neurofilament light protein (Nfl)

Neuronal injuries and degeneration are prominent and sensitive early hallmarks for neurodegenerative diseases [68, 69]. Except for using neuroimaging methods to measure neurodegeneration, biofluid biomarkers may provide a more sensitive, more convenient and cheaper measure to evaluate central pathogenesis. Among the most promising biomarkers for HD related to axonal degeneration is neurofilament light protein (Nfl), the light chain isoform of neurofilament proteins [70]. The application of single-molecule assay made the quantification of Nfl possible and reliable in blood samples first in 2015 [71]. And after that, the role of peripheral Nfl level as a potential robust biomarker for HD has been investigated extensively and profoundly [72, 73]. As plasma Nfl is widely supposed to be originated from CNS neuronal injuries and associated with CSF Nfl level [71, 74–76], it is quite valuable and encouraging for a peripheral biofluid biomarker to reflect central pathogenesis, paving the way for its future presumable application in stratifying HD mutation carriers through identification of particular disease stage, especially for premanifest patients, reflecting or even predicting the neuropathological and clinical progression and indicating the therapeutic effect as an outcome measure of clinical trials.

Elevated plasma Nfl concentrations were observed in many studies comparing HD patients with healthy controls [62, 74, 77–81]. However, it appeared to be more important for a biomarker to distinguish premanifest and manifest patients in HD, or even further, to help evaluate the years to onset of premanifest patients and classify the patients into disease stages more precisely. Plasma Nfl was validated to distinguish premanifest and manifest patients [62], and also showed significant difference between early-onset and late-onset patients [74]. Parkin et al. reported that the cut-off of 74.84 pg/ml for plasma Nfl distinguished manifest patients from premanifest mutation carriers with a sensitivity of 87.18% and specificity of 88.46% [78]. Longitudinal assessments over 24 months in the HD-CSF cohort further depicted the sigmoidal pattern of plasma Nfl change during disease progression clinically [61]. One retrospective cohort study firstly revealed its value of predicting clinical symptoms’ onset, which showed that baseline plasma Nfl level was a potent prognostic indicator for subsequent clinical onset within 3 years among premanifest HD patients [74]. Parkin et al. further observed the association between baseline plasma Nfl level and the clinical onset within 5 years [78] and prognostic index score-derived years to onset (PIN-YTO) [79]. They also reported that the cut-point of 45.0 pg/ml for plasma Nfl distinguished premanifest participants with > 10 predicted years to onset from those ≤ 10 years [79]. Huntington's disease Young Adult Study (HD-YAS) showed that CSF Nfl presented a more significant association with predicted years of onset than plasma Nfl among the premanifest participants who were on average approximately 24 years from predicted onset, suggesting the predictive ability of plasma Nfl among mutation carriers far from onset may be limited compared to CSF Nfl [81].

The significant correlation between plasma Nfl level and clinical and neuroimaging changes was also validated and discussed extensively [61, 62, 74, 77, 78]. Byrne and Rodrigues et al. reported that both plasma and CSF Nfl were associated with clinical severity assessed by cUHDRS scores (a composite measurement of motor, cognitive and functional performances) cross-sectionally [62] and subsequent clinical decline over two years longitudinally [61] and over three years in a retrospective study [74], however, only the correlation of plasma Nfl and clinical severity survived after adjusting for age and CAG repeat length [61, 62], indicating that plasma Nfl had a more robust and potent correlation with clinical symptoms than the CSF Nfl level. The investigators further explored whether the change rate of the plasma Nfl level was also an effective indicator; however, it performed worse than baseline Nfl concentrations in reflecting the current clinical state or predicting subsequent clinical progression [61]. Although most previous studies supported the great value of plasma Nfl in reflecting clinical severity and progression, a recent study by Parkin et al. proposed that plasma Nfl was an indicator of onset, but not symptom progression. As prior studies always used a combined premanifest and manifest cohort, they critically performed the analyses among premanifest and manifest participants separately and did not observe an association between Nfl level and clinical signs of HD among premanifest and manifest individuals separately [78]. Such a correlation can only be detected when the investigators include both premanifest and manifest individuals in the group [78], suggesting that further longitudinal studies should consider the value of plasma NFL in different stages of HD.

There are also still many uncertainties regarding CSF or plasma Nfl as outcome measures in the clinical trials. In the phase 1/2 trial of tominersen (IONIS-HTTRx), the investigators did not observe the decreased Nfl level as expected, but detected obvious dose- and time-dependent elevation of CSF Nfl during the trial and a transient increase in the open-labeled extension study. The increasing trend reversed after the cessation of the trial regimen and it remains incompletely explained [24]. As supposed by Byrne and colleagues [74], we believe that it is of great value to perform retrospective exploratory analyses in blood and CSF samples collected in previous clinical trials and including plasma and CSF Nfl levels as outcome measures in the future observational and therapeutic trials to test the efficacy and safety of interventions. Although most of HTT-lowering strategies currently being conducted are administered intrathecally which indicates an easy access to CSF samples, we believe that plasma Nfl can still provide additional information and play an important role in clinical trials of orally or intravenously administered therapeutics and long-term follow-up.

Oxidative stress biomarkers

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage play an important role in the onset and progression of many neurodegenerative diseases [82]. Increased oxidative stress markers accompanied by dysfunctional antioxidant systems in peripheral circulation was also reported among HD patients [83, 84]. The involvement of oxidative damage in HD pathogenesis is clear and many preclinical studies of drugs targeting at oxidative stress were encouraging [85]. However, most antioxidants as disease-modifying therapies were not proven to be effective in clinical trials [85, 86] Here, we summarized currently proposed promising blood-based biomarkers related to oxidative stress and antioxidant processes in HD and discussed their associations with clinical manifestations. Relevant studies were listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summarization of previous studies on biomarkers of oxidative stress in HD patients

| Biomarker | Study | Sample size (N) | Findings | Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-OHdG | Hersch et al. 2006 [87] | 94 (64 HD and 30 C) | HD > C | NR | Serum |

| Chen et al. 2007 [91] | 52 (16 HD and 36 C) | HD > C | HPLC | Leukocytes | |

| Long et al. 2012 [88] | 77 (57 Pre HD and 20 C) |

Pre HD > C Corr predicted symptom onset |

LCECA | Leukocytes | |

| Borowsky et al. 2013 [92] | 160 (64 HD, 64 PreHD, 32 C) | HD = Pre HD = C | LCECA | Plasma | |

| Ciancarelli et al. 2014 [89] | 28 (18 HD, 10 C) | HD > C | ELISA | Serum | |

| UA | Auinger et al. 2010 [96] | 347 HD | Corr TFC | NR | Serum |

| Corey-Bloom et al. 2020 [97] | 107 (38 HD, 31 PreHD, 38 C) |

Females: HD < Pre HD < C Males: HD = PreHD = C |

Colorimetric Enzymatic Reaction | Plasma | |

|

Females: positively corr with TMS Males: negatively corr with TFC, positively corr with TMS | |||||

| KP | Stoy et al. 2005 [102] | 26 (11 HD, 15 C) |

HD > C: K:T ratio, Kynurenine, Xanthurenic acid HD = C: QA, KYNA, Tryptophan HD < C: 3-Hydroxykynurenine, 3-Hydroxykynurenine acid, KYNA:K ratio |

HPLC | Plasma |

| Forrest et al. 2010 [103] | 113 (54HD, 19 PreHD, 40C) |

HD > C: K:T ratio HD = C: KYNA, Kynurenine, Tryptophan, 3-Hydroxykynurenine acid, Anthranilic acid |

HPLC | Serum | |

| Rodrigues et al. 2021 [179] | 80 (40 HD, 20 PreHD, 20 C) | HD = Pre HD = C | HPLC | Plasma |

8-OHdG 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine, UA uric acid, KP kynurenine pathway, HD Huntington’s disease, PreHD premanifest HD, C Controls, HPLC high performance liquid chromatography-electrochemical, LCECA liquid chromatography-electrochemical array, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, TFC total functional capacity, TMS total motor score, KT kynurenine tryptophan ratio, QA quinolinic acid, KYNA kynurenic acid, KYNAK kynurenic acidkynurenine, NR not reported, Corr correlate with

8-OHdG

8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is an indicator of DNA damaged by reactive oxygen free radicals [87] and was one of the most widely investigated biomarkers of oxidative stress in the early studies. Long and his colleagues first reported that both leukocyte 8-OHdG level and the rate of its annual change increased with the proximity to predicted onset time, which suggested that leukocyte 8-OHdG level monitoring could provide information for the predication of clinical onset [88]. Although other investigators also found increased 8-OHdG in serum [87, 89], plasma [90], and leukocytes [91] compared to healthy controls, significant correlations between 8-OHdG and the onset and clinical severity were not detected in most studies [89, 91, 92]. Hersch et al. also reported that the antioxidant creatine decreased plasma 8-OHdG level but did not improve any clinical symptoms [87]. A well-designed longitudinal study based on TRACK-HD patients observed no significant change in 8-OHdG among premanifest HD, early HD and healthy controls [92]. The utility of 8-OHdG yielded conflicting results and showed limited potential as a biomarker for HD considering the current evidence [93].

Uric acid (UA)

Uric acid (UA) is a natural antioxidant which can eliminate oxygen free radicals and alleviate oxidative stress damage in many neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) [94, 95]. In HD, a higher baseline serum UA level is significantly associated with more rapid clinical progression measured by the change of total functional capacity(TFC) and total motor score (TMS) in 30 months [96], but is not correlated with cognitive, behavioral and neuropsychological performances. Subsequent study performed by Corey-Bloom et al. reported that plasma UA level were lower only in female premanifest and manifest HD patients compared with healthy controls, but not in males [97]. The associations of plasma UA level between clinical manifestations also showed different patterns in females and males. Specifically, both females and males showed a significant positive correlation of plasma UA to TMS, while a negative correlation of plasma UA to TFC was only detected in male patients. The value of plasma UA as a biomarker reflecting clinical signs, its relationship with CSF UA levels and its gender-specific manner are worthy of further investigation in well-designed longitudinal studies to provide more evidence.

Kynurenine pathway (KP)

Kynurenine pathway (KP), the oxidative metabolic pathway of tryptophan in the microglia, is considered to be involved in the pathogenic process of HD [98]. 3‐hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) and its downstream product quinolinic acid (QA) are important components of KP and exerted neurotoxic effect through inducing excitoxicity [99]. QA was actually used to establish HD models for its excitotoxity before verification of the monogenetic mutation of HD [100]. Another important component of the same pathway, kynurenic acid (KYNA), were validated to display neuroprotective role in HD conversely [101]. Early studies by Stoy et al. and Forrest et al. both reported increasing kynurenine: tryptophan ratio in HD patients compared with controls, indicating an imbalance of KP in HD [102, 103], but did not detect a significant difference in baseline QA, 3-HK and KYNA levels [102, 104]. Forrest et al. further detected a negative association between tryptophan and symptoms’ severity and CAG repeats number.

However, recently, HD-CSF study by Rodrigues et al. reported no significant change in most of KP metabolites from CSF or plasma among manifest, premanifest patients and healthy controls and no associations with any clinical or imaging signs [88]. Patient-derived biofluids appear not to reflect the substantial aberrations of KP in HD. Moreover, the change of peripheral KP metabolites are supposed to be interpreted cautiously because KP metabolites in the central have different abilities to cross the blood‒brain barriers, and raises a question that whether blood is an appropriate medium to reflect the alterations of those complex components in KP related to neuropathology in HD [101]. It will be of great value to further investigate KP metabolites in blood with matched CSF samples to in a larger cohort to provide a conclusive answer.

Endocrine function biomarkers

Neuronal loss and abnormal endocrine functions have been reported in the hypothalamus [105], leading to pathogenic changes in the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal axis (HPA), hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, etc. [106]. Endocrine biomarkers in the peripheral circulatory system can also reflect central dysfunction. However, endocrine peripheral biomarkers can be easily affected external factors including drug treatment and patients’ mental state. In addition, the secretion of most hormones, such as melatonin, follows specific diurnal rhythms, resulting in the obvious heterogeneity in the published literatures and posing challenges to samples collection in the clinical setting [14]. Here, we summarized promising endocrine biomarkers in peripheral circulation and listed relevant studies in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summarization of previous studies on biomarkers of endocrine function in HD patients

| Biomarker | Study | Sample size (N) | Findings | Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH | Saleh et al. 2009 [106] | 290 (219HD, 71C) | HD = C | ELISA | Plasma |

| Cortisol | Leblhuber et al. 1995 [110] | 36 (11HD, 25C) | HD > C in males | NR | Serum |

| Mochel et al. 2007 [107] | 53 (32HD, 21C) | HD = C | ELISA | Serum | |

| Markianos et al. 2007 [108] | 125 (41HD, 18PreHD, 66C) | HD = Pre HD = C in females | NR | Plasma | |

| Saleh et al. 2009 [106] | 290 (219HD, 71C) |

HD > C No corr independence scale, TFC, TMS, behavioral score |

ELISA | Plasma | |

| Aziz et al. 2009 [111] | 16 (8HD, 8C) |

HD > C: Total cortisol secretion rate and the amplitude of the diurnal cortisol profile Corr TMS and TFC |

ELISA | Plasma | |

| Kalliolia et al. 2015 [109] | 42 (13HD, 14PreHD, 15C) | HD = Pre HD = C | ELISA | Serum | |

| RAS-related components | Lee et al. 2014 [115] | 261 (132HD, 129C) |

HD > C Corr the onset, disease duration, UHDRS, TFC, independency scale and disease burden, |

ELISA | Serum |

| Rocha et al. 2020 [114] | 57 (23HD, 18Pre HD, 16C) | HD = Pre HD = C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Christofides et al. 2006 [119] | 26 (11HD, 15C) | HD = C | Radioimmunoassay | Plasma | |

| Melatonin | Aziz et al. 2009 [120] | 18 (9HD, 9C) |

HD = C: mean diurnal melatonin Delayed time to peak Corr motor and functional impairment |

Radioimmunoassay | Plasma |

| Kalliolia et al. 2014 [121] | 42 (13HD, 14Pre HD, 15C) | HD < Pre HD < C: mean and acrophase melatonin | Radioimmunoassay | Plasma | |

| Adamczak-Ratajczak et al. 2017 [122] | 21 (3Stage 1, 2Stage 2, 6Stage 3, 10C) |

Delayed time to peak, lower amplitude and mesor in Stage 3 HD |

ELISA | Serum | |

| BDNF | Ciammola et al. 2007 [129] | 84 (42HD, 42C) |

HD < C Corr CAG repeats, disease duration, motor and cognitive performances |

ELISA | Serum |

| Zuccato et al. 2011 [132] | 398 (204HD, 56PreHD, 138C) | HD = Pre HD = C | ELISA | Serum and plasma | |

| Tasset et al. 2012 [131] | 38 (19HD, 19C) | HD < C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Wang et al. 2014 [133] | 39 (8HD, 15PreHD, 16C) | HD = Pre HD = C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Gutierrez et al. 2020 [126] | 84 (21HD, 30PreHD, 33C) | HD = Pre HD = C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Andy Ou et al. 2021 [133] | 80 (40HD, 20PreHD, 20C) |

HD = Pre HD = C No corr clinical scores or MRI brain volumetric measures |

ELISA | Plasma |

ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone, RAS Renin–angiotensin system, BDNF Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, HD Huntington’s disease, PreHD premanifest HD, C controls, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, TFC Total functional capacity, TMS total motor score, NR not reported

Hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal (HPA) axis

The results of the published studies regarding abnormal HPA axis secretion in the blood-based samples showed widely inconsistency. Although some studies detected no significant changes of plasma or serum cortisol between HD patients and controls [107–109], other investigations indeed observed the elevated level of cortisol in the HD patients [106, 110, 111]. Using the method of 24-h multiple measurements, Kalliolia et al. observed no differences of serum cortisol level between healthy controls, premanifest and manifest patients [109]. However, Aziz et al. found that plasma cortisol concentrations differed significantly in the three groups, especially in the morning and early afternoon period. Additionally, they further reported that mean 24-h cortisol was associated with TMS and TFC clinically [111].

The inconsistency of the published studies may be partially explained by the different clinical state of the included patients, inconsistent selection of potential covariates and different samples collection procedures. Considering the strict standard for samples collection, susceptibility to external conditions and comorbidities and the poor reproducibility, blood-based cortisol level appears to be less optimal and practical as a biomarker for HD in the clinical setting. Nonetheless, preliminary studies indicated a tighter correlation between salivary cortisol and psychiatric symptoms of HD [112, 113]. Compared to blood and saliva which captured the real-time level of cortisol, hair cortisol level is capable of providing the information of a long-term cortisol level [110], providing new directions for future studies.

Renin–angiotensin system (RAS)

The role of peripheral RAS in HD was investigated preliminarily. Rocha et al. first studied the peripheral changes in critical RAS components, including Ang II, Ang-(1–7), ACE, and ACE2, and their correlations with clinical measurements. They detected no significant group differences among healthy controls, premanifest HD patients and motor manifest patients but reported correlations between plasma ACE and Ang II level with cognitive performance [114]. The sample size of this cross-sectional study is relatively small, and further longitudinal research is warranted. Lee et al. detected the increased anti-angiotensin II type 1 receptor antibodies level in the serum of HD patients and its significant correlations with the onset of motor symptoms, duration of disease, UHDRS and TFC, independency scale and disease burden, indicating its potential value as a peripheral biomarker for HD [115]. Overall, there is still a paucity of the evidence of RAS-related components as biomarkers in HD to date.

Melatonin

Sleep disturbances were reported to affect nearly 90% of HD patients [116] and might be partially associated the abnormal secretion of melatonin in HD [117]. Melatonin, a pleiotropic hormone secreted by the pineal gland, maintains normal circadian rhythms and plays a neuroprotective role [118]. One early study detected no obvious changes of plasma melatonin level in HD patients compared to the controls [119]. However, the samples collection in this study was performed in a single timepoint and could only provide limited information.

24-h profiles of melatonin secretion were analyzed generally in the subsequent studies [120–122]. Although most studies still did not report a significant change of mean melatonin level compared to controls [120, 122], a different secretion pattern of melatonin was observed. Aziz et al. found that the time to peak of melatonin secretion was significantly delayed by over 90 min in early-stage HD patients compared with controls and observed a correlation between diurnal melatonin concentrations and motor and functional dysfunction [120]. Another study only detected the delay of melatonin phase with lowered amplitude and mesor in the late-stage HD patients, but not significant in the early stage [122]. Although these studies reported conflicting results in the different stage of HD, they preliminarily validated the altered pattern of plasma melatonin secretion by 24-h observations, but not by a single measurement. It should be noted that this mode of evaluation may not be practical to be performed in the clinical settings and peripheral melatonin level appeared not to be a convenient and optimal biomarker for HD considering the current evidence. Nonetheless, the neuroprotective role of melatonin was proven in HD rat models, indicating its potential role in improving some clinical manifestations and as biomarkers in clinical trials targeting at sleep disturbances [123, 124]. Future studies are supposed to perform the 24-h examinations through multiple measurements and concern that at what time of day the biomarker is the most informative.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

BDNF is an essential neurotrophic factor in the growth, maturation, and survival of neurons produced by cortical neurons [125], and it has been proven to play a critical role in various neurodegenerative diseases [126]. In HD, the presence of mHTT may disrupt normal transcription and translation processes of BDNF and suppress the functions of BDNF [127, 128], leading to selective injuries and damage to the brain, particularly the striatum [126].

The concentration change of BDNF in blood-based samples of HD patients remains controversial in previous studies. Early studies mostly reported that blood-based BDNF levels decreased in HD patients compared with controls [129–131], and Ciammola et al. further observed a significant association between BDNF level and clinical severity assessed by UHDRS motor and cognitive performance [129]. However, these conclusions were not replicated in other studies. Zuccato and colleagues detected no obvious difference of BDNF level in both serum and plasma based on a large cohort [132]. Subsequent studies using plasma samples validated this finding [126, 133] and further showed no significant associations between plasma BDNF with any clinical signs of HD [126, 134], suggesting that peripheral BDNF might not be a promising biomarker for HD [132, 134].

Overall, considering the current evidence, the value of BDNF as a biomarker may not be as robust and potent as that of other neuronal injury indicators, such as Nfl and mHTT. The peripheral BDNF did not decrease as expected, which may be partially explained by the region-specific secretion properties and its complex originations. Many studies have reported that BDNF decrease mostly occurred in the striatum [135–137], but the cortex was unaffected, or even compensated for the deficit [138]. Although BDNF level changes remain conflicting in blood, over-expression of BDNF has been verified to improve the HD phenotype in the mouse model [128], suggesting its potential role as a therapeutic target in the future. Interestingly, the analysis of DNA methylation level at BDNF Promoter IV in the whole blood detected a significant association with anxiety and depression symptoms, but not with any motor or cognitive performances [126]. The unique relationship between DNA methylation alterations of BDNF Promoter IV and neuropsychiatric symptoms deserves further validation.

Immune system biomarkers

Although abnormal immune responses have been described in many other neurodegenerative diseases [139], HD is still a unique case because the expression of mHTT in leukocytes and microglia of HD patients could primarily and directly induce the abnormal hyperactivities of immune system [140]. And immune cells express higher levels of mHTT than other tissues, and growing evidence has revealed abnormal peripheral inflammation in HD [140]. The cytokines profile in HD patients has been proven by many investigators to be different from that in healthy controls [38]. Such differences may result from primary changes in peripheral, secondary to central pathogenic processes or both, considering the ability of many cytokines to cross BBB and the tight association between peripheral and central cytokines [141]. However, peripheral immune activation is also easily affected by clinical therapeutic measures, such as some antipsychotics and other comorbidities, such as infections [142]. Hence, the value of blood-based immune biomarkers in clinical settings may be limited. The related literature is listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summarization of previous studies on biomarkers of immune system in HD patients

| Biomarker | Study | Sample size (N) | Findings | Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Dalrymple et al. 2007 [143] | 94 (46HD, 16Pre HD, 34C) | HD > Pre HD, HD > C | ELISA | Plasma |

| Mochel et al. 2007 [107] | 53 (32HD, 21C) | HD = C | ELISA | Serum | |

| Björkqvist et al. 2008 [144] | 46 (28Moderate HD, 9Early HD, 9C) | Moderate HD > Early HD > C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Sánchez-López et al. 2012 [145] | 23 (13HD, 10C) | HD > C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Trager et al. 2014 [180] | 80 (14 Moderate HD, 22 Early HD, 17PreHD, 27C) | Moderate HD > Early HD > PreHD > C | ELISA | PBMCs | |

| Wang e al. 2014 [133] | 39 (8HD, 15PreHD, 16C) | HD = PreHD = C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Chang et al. 2015 [147] | 36 (15HD, 5PreHD, 16C) |

HD > PreHD > C Corr independence scale and functional capacity |

ELISA | Plasma | |

| Corey-Bloom et al. 2020 [142] | 125 (37HD, 36Pre HD, 52C) |

HD > PreHD No corr with any clinical signs |

ELISA | Plasma | |

| IL-8 | Björkqvist et al. 2008 [144] | 46 (28Moderat HD, 9Early HD, 9C) |

Moderate HD > Early HD > C Corr UHDRS scores, TFC and TMS |

ELISA | Plasma |

| Trager et al. 2014 [180] | 80 (14 Moderate HD, 2 Early HD, 17PreHD, 27C) | Moderate HD = Early HD = PreHD = C | ELISA | PBMCs | |

| IL-18 | Chang et al. 2015 [147] | 36 (15HD, 5PreHD, 16C) |

IL-18: HD < C, PreHD < C No corr with independence scale and functional capacity |

ELISA | Plasma |

| IL-23 | Forrest et al. 2010 [103] | 113 (54HD, 19 PreHD, 40C) |

HD > PreHD = C Corr clinical severity and CAG repeats |

ELISA | Serum |

| TGF-β1 | Battaglia et al. 2011 [150] | 172 (95HD, 30PreHD, 47C) |

Pre HD < C, HD = C Corr CAG repeats, rate of progression, age of onset |

ELISA | Serum |

| Chang et al. 2014 [147] | 36 (5 PreHD, 15 HD and 16 C) | HD > Pre HD > C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Plinta et al. 2021 [151] | 140 (100 HD, 40 C) | HD = C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Chemokines | Wild et al. 2011 [152] | 99 (27 moderate HD, 23 Early HD, 15Pre HD, 34C) |

Eotaxin 3: Moderate HD > Early HD,PreHD,C MIP-1β: Moderate HD > C Eotaxin: Moderate HD = Early HD > PreHD = C MCP-1: Early HD > C MCP-4: Early HD > PreHD,C Eotaxi,MCP-1: Corr TMS and functional capacity |

ELISA | Plasma |

| Clusterin | Dalrymple et al. 2007 [143] | 73 (37 HD, 18Pre HD, 18C) | HD > Pre HD, HD > C | ELISA | Plasma |

| Silajdzic et al. 2013 [153] | 121 (40HD, 41PreHD, 40C) | HD = Pre HD = C | ELISA | Serum | |

| CRP | Stoy et al. 2005 [102] | 26 (11 HD, 15 C) | HD > C | ELISA | Plasma |

| Mochel et al. 2007 [107] | 53 (32HD, 21C) | HD = C | ELISA | Serum | |

| Sánchez-López et al. 2012 [145] | 23 (13HD, 10C) | HD > C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Silajdziˇ c et al. 2013 [153] | 121 (40HD, 41PreHD, 40C) |

HD < C No corr with clinical signs |

ELISA | Serum | |

| Wang e al. 2014 [133] | 39 (8HD, 15PreHD, 16C) | PreHD > C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Bouwens et al. 2014 [181] | 164 (122HD, 42C) |

HD > C during follow-up Corr TFC, apathy, cognition and antipsychotics use |

IFCC standardized method (COBAS INTEGRA 800 analyzer) | Plasma | |

| Corey-Bloom et al. 2020 [142] | 125 (37HD, 36Pre HD, 52C) | PreHD > C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Neopterin | Leblhuber et al. 1998 [182] | 23 (12HD, 11C) |

HD > C Corr cognitive functions |

ELISA | Serum |

| Widner et al. 1999 [154] | 12HD, ?C (NR) | HD > C | ELISA | Serum | |

| Stoy et al. 2005 [102] | 26 (11 HD, 15 C) |

HD > C Corr age and CRP level |

ELISA | Serum | |

| Christofides et al. 2006 [119] | 26 (11HD, 15C) | HD > C | ELISA | Serum |

IL interleukin, TGF-β transforming growth factor-β, CRP C-reactive protein, MCP monocyte chemoattractant protein, UHDRS unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale, HD Huntington’s disease, PreHD premanifest HD, C Controls, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, TFC total functional capacity, TMS total motor score, NR not reported, PBMCs peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Cytokines

Proteomic profiling of HD patients’ plasma by Dalrymple et al. first revealed that plasma IL-6 increased as the disease progressed, even after considering confounding factors, including age and sex [143]. Björkqvist et al. further reported that the concentrations of plasma IL-6 and IL-8 were early identified markers in the natural history of HD compared to healthy controls. The increase of plasma IL-6 level could be found nearly 16 years before predicted clinical onset in mutation carriers [144]. The increase of plasma IL-6 level was replicated in other independent cohorts [145–147], but no change of IL-6 has also been reported [107, 133, 141]. Chang et al. detected significant correlations of IL-6 concentrations to independence scale and functional capacity [147]. Additionally, plasma IL-8 level was significantly associated with clinical signs measured by UHDRS chorea scores, TFC and TMS [144]. However, Corey-Bloom et al. did not observe any associations between IL-6 and any clinical measurements in a larger cohort [142].

Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) is a multifunctional cytokine involved in various pathophysiological processes and possesses neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory functions [148, 149]. The level change of plasma TGF-β1 in HD is controversial [147, 150, 151]. Furthermore, most studies did not observe any associations between TFG-β1 and HD clinical manifestations [151]. The value of TGF-β1 as a peripheral biomarker in HD requires further validation.

Chemokines

Wild et al. reported altered chemokine profiles in HD patients compared with healthy controls. Specifically, the plasma levels of eotaxin-3, MIP-1β and eotaxin increased with disease progression clinically, and plasma MCP-1 and eotaxin levels were correlated significantly with UHDRS motor scores and function scores [152]. However, this finding has not been replicated in other independent cohorts to date.

Other biomarkers related to immune activation

Clusterin, also called apolipoprotein J, is a complement inhibitor [101]. Dalrymple et al. observed increased clusterin concentrations in plasma with HD stages [143]. However, the result was not replicated in serum samples in Silajdziˇ c’s study [153]. Many other inflammatory peripheral biomarkers have also been proposed and investigated, such as neopterin [102, 119, 154] and some acute-phase proteins [102, 107, 142], with limited replication and validation. Interestingly, Björkqvist et al. found that combinations of different cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10, were of great value in discriminating manifest HD patients, mutation carriers and healthy controls [144].

Metabolic biomarkers

Metabolic disorder in HD is characterized by progressive weight loss, abnormal cholesterol and amino acids metabolism and increased energy consumption clinically, caused by neuropathogenic injuries of energy-regulating processes, abnormal endocrine functions or peripheral mHTT expression [155, 156]. Van der Burg et al. reported that high body mass index (BMI) was significantly associated with slower clinical progression in a cohort of 5,821 mutation carriers [157]. Abnormal metabolic processes may provide new possibilities for robust peripheral biomarkers reflecting disease severity and development. Relevant studies were listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summarization of previous studies on biomarkers of metabolic biomarkers in HD patients

| Biomarker | Study | Sample size (N) | Findings | Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | Leoni et al. 2008 [161] | 303 (127HD, 42PreHD, 134C) | HD = PreHD = C | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Plasma |

| Markianos et al. 2008 [183] | 295 (145HD, 150C) |

HD < C No corr with any UHDRS scores |

ELISA | Plasma | |

| Salvatore et al. 2011 [184] | 34 (17HD, 17C) | HD = C | NR | Serum | |

| Wang e al. 2014 [133] | 39 (8HD, 15PreHD, 16C) | HD < C | ELISA | Plasma | |

| Nielsen et al. 2016 [185] | 160 (70HD, 50PreHD, 40C) | HD > PreHD = C | NR | NR | |

| 24OHC | Leoni et al. 2008 [161] | 303 (127HD, 42PreHD, 134C) |

HD < PreHD = C Corr caudate volumes |

Isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Plasma |

| Leoni et al. 2011 [158] | 303 (127HD, 42PreHD, 134C) | Corr motor score | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Plasma | |

| Leoni et al. 2013 [160] | 150 (52H, 47 M, 21L, 30 C) | H < M < L < C | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Plasma | |

| Amino acids | Cheng et al. 2016 [163] | 82 (29HD, 9Pre HD, 44C) |

HD > PreHD = C: glycine HD < PreHD = C: taurine, BCAA |

Mass spectrometry | Plasma |

| Reilmann et al. 1995 [186] | 37 (16HD, 21C) | HD < C: alanine and isoleucine | HPLC | Plasma | |

| Mochel et al. 2007 [107] | 53 (32HD, 21C) |

HD < C: BCAA BCAA corr with weight loss, CAG repeats, disease stages |

1H NMR spectroscopy | Plasma | |

| Mochel et al. 2011 [164] | 107 (70HD, 16PreHD, 21C) | HD < C: BCAA | NR | Plasma | |

| Gruber et al. 2013 [187] | 59 (24HD, 6PreHD, 29C) |

HD < C: asparagine, histidine, serine HD = C:citrulline, leucine, threonine |

HPLC | Plasma | |

| Aziz et al. 2015 [188] | 18 (9HD, 9C) | HD = C: all analyzed amino acids | NR | Plasma | |

| Nambron et al. 2016 [189] | 42 (13HD, 14PreHD, 15C) | HD = C, PreHD < C: phenylalanine, lysine and arginine | HPLC | Plasma | |

| McGarry et al. 2020 [162] | 12HD |

Arginine: corr with TMS and cognitive performances: arginine Citrulline: corr with independence score and cognitive performances Glycine: corr with TFC, independent score, cognitive performances and TMS Serine: corr with cognitive performances, independent score |

Mass spectrometry | Plasma |

24OHC 24S-hydroxycholesterol, H high gene-expanded, M medium gene-expanded, L low gene-expanded, BCAA branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine), ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, UHDRS unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale, TMS total motor scores, TFC total functional capacity, HPLC high performance liquid chromatography-electrochemical

Cholesterol metabolism

Cholesterol synthesis and metabolism are complex processes involving a complex multistep pathway [158]. Brain-based biomarkers related to cholesterol metabolism are difficult, expensive and unsafe to measure, highlighting the great value of relevant metabolites in the blood-based samples. 24S-hydroxycholesterol (24OHC), converted by 24-hydroxylases (CYP46), is a key metabolite released from the brain to peripheral circulation [159]. Leoni et al. reported significantly decreased plasma total cholesterol level when comparing late HD patients with early HD patients and decreased 24OHC level when comparing all HD patients with normal controls. However, no differences in 24OHC level were detected between the control and premanifest group [158]. In another PREDICT-HD cohort, Leoni et al. observed a significant difference among low, medium and high gene-expanded groups, showing a decreasing trend [160]. Furthermore, investigators found that the decreased 24OHC level paralleled the caudate volume change [161], indicating that peripheral 24OHC’s potential in reflecting central pathogenic processes in HD.

Other biomarkers related to metabolism

Metabolomics provided new method for detecting abnormally changed metabolites in plasma. Rosas et al. identified altered tryptophan, tyrosine, and purine pathways using metabolomics [104]. Decreased branch-chain amino acids, including valine, leucine and isoleucine, have been observed in most studies [162–164]. McGarry et al. [162] and Cheng et al. [163] also reported elevated glycine level in plasma with clinical disease progression. However, no other studies have reported the correlations between these changes and clinical severity until now.

MicroRNA (miRNA)

miRNAs are small single-stranded non-coding RNAs that bind to the 3′ untranslated regions of target mRNAs to regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level [165, 166]. miRNA dysregulation is associated with HTT aggregation [167], abnormal apoptosis [168], reduced mitochondrial functions [169] and other pathophysiologic processes in HD [170]. Despite its intracellular functions, miRNA can be released into the peripheral circulation in the form of exosomal miRNA or stable components binding with proteins in the blood, such as high-density lipoprotein [171, 172], indicating its potential value as peripheral biomarkers for HD. Gaughwin et al. first proved that hsa-miR-34 was elevated in premanifest HD patients’ plasma but not in controls’ or manifest patients, validating the feasibility of circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for HD preliminarily [173]. Other investigators also observed the dysregulation of other miRNAs in HD patients [174–177]. Díez-Planelles et al. detected thirteen kinds of miRNAs that were increased in HD patients and further reported that miR-122-5p level in plasma was significantly associated with UHDRS scales [177]. miR-100-5p, miR-641 and miR-330-3p were found to be correlated with TFC [177], and miR-10b-5p correlated with the age of symptoms onset [176]. In general, the investigations of circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for HD are still preliminary, limited and inconsistent to date and further exploration is warranted. Relevant studies were summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summarization of previous studies on biomarkers of miRNAs in HD patients

| Study | Sample size (N) | Findings | Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaughwin et al. 2011 [173] | 39 (16HD, 11PreHD, 12C) | PreHD > C = HD:Hsa-miR-34 | miR microarray analysis | Plasma |

| Hoss et al. 2015 [190] | 38 (26HD, 4PreHD, 8C) |

HD > PreHD = C, Corr age of onset: miR-10b-5p HD > C: miR-486-5p |

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR | Plasma |

| Díez-Planelles et al. 2016 [177] | 22 (15HD, 7C) |

HD > C: miR-877-5p, miR-223-3p, miR-223-5p, miR-30d-5p, miR-128, miR-22-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-338-3p, miR-130b-3p, miR-425-5p, miR-628-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-942 Corr UHDRS: miR-122-5p Corr TFC: miR-100-5p, miR-641, miR-330-3p |

qRT-PCR | Plasma |

| Chang et al. 2017 [175] | 72 (36HD, 8PreHD, 28C) |

HD < C: miR-9 No corr with UHDRS |

TaqMan miRNA assays | Peripheral leukocytes |

| Ferraldeschi et al. 2021 [174] | 49 (25HD, 24C) | HD > C: Hsa-miR-323b-3p | Digital droplet PCR | Plasma |

HD Huntington’s disease, PreHD premanifest HD, C controls, TFC total functional capacity, qRT-PCR quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, UHDRS unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale

Conclusion and future prospects

The monogenic mutation in HD provides an opportunity to identify premanifest HD in the early stage of the disease. To investigate the effect of potential disease-modified treatment strategies, especially among those mutation carriers before clinical symptoms onset, robust biomarkers that can objectively and quantitatively reflect pathophysiologic changes in HD patients are urgently required. In the past decade, numerous potential peripheral biomarkers in blood-based samples have been proposed and investigated. However, many of them demonstrated disappointing and conflicting results and there was a paucity of proper well-designed replication studies. Among those blood-based biomarkers, plasma Nfl appeared to be the most promising and encouraging peripheral biomarker. Although it is a non-specific biomarker which can be confused with neuronal injuries caused by other diseases, the strength and practicability of blood-based Nfl are highlighted in the case of HD since gene testing and mHTT-related neuropathology could provide additional information. The expression of mHTT, as a characteristic change in HD, has not been investigated extensively and thoroughly in the peripheral circulation compared to Nfl. The phase III trial of the ASO (tominersen) presented disappointing results, and some investigators suggested that allele-selective treatment strategies might be more reasonable [178], indicating the necessity of quantitative analysis of both mHTT and wild-type HTT in the future.

Blood-based biomarkers for HD have gained increasing attention in recent years and reveal new aspects of disease pathogenesis, especially referring to immune reactions of HD patients. However, blood-based biomarkers have rarely been applied in clinical practice or clinical trials to date. With growing explorations of peripheral-administered targeting therapeutics or other interventions that may be expected to elicit systemic effects in HD, we believed that the value of blood-based biomarkers would be highlighted in the future. Currently, the exploration of blood-based biomarkers lacks well-designed systemic work. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) put forward guidelines on the biomarkers analytes [101]. The standard and rigorous biomarkers’ study design was discussed comprehensively in a previous review summarized by Silajdžić et al. [84]. Another prominent problem is the discrepant definition of the stage of HD, leading to the incomparability of the current literature. The Integrated Staging System of HD (HD-ISS) recently reported by HD-RSC [9] can be applied in future studies to assess the changes in biomarkers in different stages of HD. Additionally, it is essential to match the blood-based biomarkers with the corresponding biomarkers in CSF in the same cohort to assess its cost and benefit. HDClarity provides a good example in which investigators plan to collect blood and CSF samples from 1200 participants across different stages of HD as well as healthy controls (NCT02855476). Rigorous systemic investigation to replicate conflicting findings in previous studies and explore new blood-based biomarkers in a large cohort will facilitate the application of potential blood-based biomarkers in clinical settings as well as clinical trials as surrogate endpoints.

Author contributions

SHF, ZSR and CYF conceived the article. ZSR searched relevant studies and wrote the article. SHF and CYF critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2022ZDZX0023).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Sirui Zhang and Yangfan Cheng have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ross CA, Aylward EH, Wild EJ, et al. Huntington disease: natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(4):204–216. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates GP, Dorsey R, Gusella JF, et al. Huntington disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15005. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Przybyl L, Wozna-Wysocka M, Kozlowska E, Fiszer A. What, when and how to measure-peripheral biomarkers in therapy of Huntington’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms22041561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans SJ, Douglas I, Rawlins MD, Wexler NS, Tabrizi SJ, Smeeth L. Prevalence of adult Huntington's disease in the UK based on diagnoses recorded in general practice records. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(10):1156–1160. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher ER, Hayden MR. Multisource ascertainment of Huntington disease in Canada: prevalence and population at risk. Mov Disord. 2014;29(1):105–114. doi: 10.1002/mds.25717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell. 1993;72(6):971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabrizi SJ, Flower MD, Ross CA, Wild EJ. Huntington disease: new insights into molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(10):529–546. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-0389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubinsztein DC, Leggo J, Coles R, et al. Phenotypic characterization of individuals with 30–40 CAG repeats in the Huntington disease (HD) gene reveals HD cases with 36 repeats and apparently normal elderly individuals with 36–39 repeats. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59(1):16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabrizi SJ, Schobel S, Gantman EC, et al. A biological classification of Huntington's disease: the Integrated Staging System. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(7):632–644. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabrizi SJ, Ghosh R, Leavitt BR. Huntingtin lowering strategies for disease modification in Huntington's disease. Neuron. 2019;102(4):899. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabrizi SJ, Estevez-Fraga C, van Roon-Mom WMC, et al. Potential disease-modifying therapies for Huntington's disease: lessons learned and future opportunities. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(7):645–658. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biomarkers Definitions Working Group Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69(3):89–95. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y, Chen Y, Shang H. Aberrations of biochemical indicators in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Neurodegener. 2021;10(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40035-020-00228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeun P, Scahill RI, Tabrizi SJ, Wild EJ. Fluid and imaging biomarkers for Huntington's disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2019;97:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huntington Study Group Unified Huntington’s disease rating scale: reliability and consistency. Huntington Study Group. Mov Disord. 1996;11(2):136–142. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weir DW, Sturrock A, Leavitt BR. Development of biomarkers for Huntington's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(6):573–590. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulsen JS, Langbehn DR, Stout JC, et al. Detection of Huntington's disease decades before diagnosis: the Predict-HD study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):874–880. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.128728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aylward EH, Liu D, Nopoulos PC, et al. Striatal volume contributes to the prediction of onset of Huntington disease in incident cases. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(9):822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurgens CK, van de Wiel L, van Es AC, et al. Basal ganglia volume and clinical correlates in 'preclinical' Huntington's disease. J Neurol. 2008;255(11):1785–1791. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazio P, Paucar M, Svenningsson P, Varrone A. Novel imaging biomarkers for Huntington's disease and other hereditary choreas. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(12):85. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulsen JS, Long JD, Johnson HJ, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in premanifest Huntington disease show trial feasibility: a decade of the PREDICT-HD study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:78. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabrizi SJ, Scahill RI, Owen G, et al. Predictors of phenotypic progression and disease onset in premanifest and early-stage Huntington's disease in the TRACK-HD study: analysis of 36-month observational data. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(7):637–649. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss DJH, Pardiñas AF, Langbehn D, et al. Identification of genetic variants associated with Huntington's disease progression: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(9):701–711. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabrizi SJ, Leavitt BR, Landwehrmeyer GB, et al. Targeting huntingtin expression in patients with Huntington's disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2307–2316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguiar S, van der Gaag B, Cortese FAB. RNAi mechanisms in Huntington's disease therapy: siRNA versus shRNA. Transl Neurodegener. 2017;6:30. doi: 10.1186/s40035-017-0101-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Estevez-Fraga C, Tabrizi SJ, Wild EJ. Huntington's disease clinical trials corner: November 2022. J Huntingtons Dis. 2022;11(4):351–367. doi: 10.3233/jhd-229006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evers MM, Miniarikova J, Juhas S, et al. AAV5-miHTT gene therapy demonstrates broad distribution and strong human mutant huntingtin lowering in a Huntington's disease minipig model. Mol Ther. 2018;26(9):2163–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeitler B, Froelich S, Marlen K, et al. Allele-selective transcriptional repression of mutant HTT for the treatment of Huntington's disease. Nat Med. 2019;25(7):1131–1142. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekman FK, Ojala DS, Adil MM, Lopez PA, Schaffer DV, Gaj T. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing increases lifespan and improves motor deficits in a Huntington's disease mouse model. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2019;17:829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fink KD, Deng P, Gutierrez J, et al. Allele-specific reduction of the mutant huntingtin allele using transcription activator-like effectors in human Huntington's disease fibroblasts. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(4):677–686. doi: 10.3727/096368916x690863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehrnhoefer DE, Sutton L, Hayden MR. Small changes, big impact: posttranslational modifications and function of huntingtin in Huntington disease. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(5):475–492. doi: 10.1177/1073858410390378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ast A, Buntru A, Schindler F, et al. mHTT seeding activity: a marker of disease progression and neurotoxicity in models of Huntington's disease. Mol Cell. 2018;71(5):675–688.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffner G, Island ML, Djian P. Purification of neuronal inclusions of patients with Huntington's disease reveals a broad range of N-terminal fragments of expanded huntingtin and insoluble polymers. J Neurochem. 2005;95(1):125–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez-Sanchez M, Licitra F, Underwood BR, Rubinsztein DC. Huntington's disease: mechanisms of pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a024240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosas HD, Salat DH, Lee SY, et al. Cerebral cortex and the clinical expression of Huntington's disease: complexity and heterogeneity. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 4):1057–1068. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neueder A, Orth M. Mitochondrial biology and the identification of biomarkers of Huntington's disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2020;10(4):243–255. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2019-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panov AV, Gutekunst CA, Leavitt BR, et al. Early mitochondrial calcium defects in Huntington's disease are a direct effect of polyglutamines. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(8):731–736. doi: 10.1038/nn884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valadão PAC, Santos KBS, Ferreira EVTH, et al. Inflammation in Huntington's disease: a few new twists on an old tale. J Neuroimmunol. 2020;348:577380. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denis HL, Lauruol F, Cicchetti F. Are immunotherapies for Huntington's disease a realistic option? Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(3):364–377. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crotti A, Benner C, Kerman BE, et al. Mutant huntingtin promotes autonomous microglia activation via myeloid lineage-determining factors. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(4):513–521. doi: 10.1038/nn.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kacher R, Lejeune FX, Noël S, et al. Propensity for somatic expansion increases over the course of life in Huntington disease. Elife. 2021 doi: 10.7554/eLife.64674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennedy L, Evans E, Chen CM, et al. Dramatic tissue-specific mutation length increases are an early molecular event in Huntington disease pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(24):3359–3367. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swami M, Hendricks AE, Gillis T, et al. Somatic expansion of the Huntington's disease CAG repeat in the brain is associated with an earlier age of disease onset. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(16):3039–3047. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monckton DG. The contribution of somatic expansion of the CAG repeat to symptomatic development in Huntington's disease: a historical perspective. J Huntingtons Dis. 2021;10(1):7–33. doi: 10.3233/jhd-200429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mouro Pinto R, Arning L, Giordano JV, et al. Patterns of CAG repeat instability in the central nervous system and periphery in Huntington's disease and in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(15):2551–2567. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shelbourne PF, Keller-McGandy C, Bi WL, et al. Triplet repeat mutation length gains correlate with cell-type specific vulnerability in Huntington disease brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(10):1133–1142. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennedy L, Shelbourne PF. Dramatic mutation instability in HD mouse striatum: does polyglutamine load contribute to cell-specific vulnerability in Huntington's disease? Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(17):2539–2544. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.17.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan S, Itzkovitz S, Shapiro E. A universal mechanism ties genotype to phenotype in trinucleotide diseases. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3(11):e235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genetic Modifiers of Huntington’s Disease (GeM-HD) Consortium CAG repeat not polyglutamine length determines timing of Huntington’s disease onset. Cell. 2019;178(4):887–900.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciosi M, Maxwell A, Cumming SA, et al. A genetic association study of glutamine-encoding DNA sequence structures, somatic CAG expansion, and DNA repair gene variants, with Huntington disease clinical outcomes. EBioMedicine. 2019;48:568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chuang CL, Demontis F. Systemic manifestation and contribution of peripheral tissues to Huntington's disease pathogenesis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;69:101358. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sassone J, Colciago C, Cislaghi G, Silani V, Ciammola A. Huntington's disease: the current state of research with peripheral tissues. Exp Neurol. 2009;219(2):385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gómez-Jaramillo L, Cano-Cano F, González-Montelongo MDC, Campos-Caro A, Aguilar-Diosdado M, Arroba AI. A new perspective on Huntington's disease: how a neurological disorder influences the peripheral tissues. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 doi: 10.3390/ijms23116089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keller CG, Shin Y, Monteys AM, et al. An orally available, brain penetrant, small molecule lowers huntingtin levels by enhancing pseudoexon inclusion. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1150. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28653-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eshraghi M, Karunadharma PP, Blin J, et al. Mutant Huntingtin stalls ribosomes and represses protein synthesis in a cellular model of Huntington disease. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1461. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21637-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiss A, Abramowski D, Bibel M, et al. Single-step detection of mutant huntingtin in animal and human tissues: a bioassay for Huntington's disease. Anal Biochem. 2009;395(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moscovitch-Lopatin M, Weiss A, Rosas HD, et al. Optimization of an HTRF assay for the detection of soluble mutant huntingtin in human buffy coats: a potential biomarker in blood for Huntington disease. PLoS Curr. 2010;2:Rrn1205. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moscovitch-Lopatin M, Goodman RE, Eberly S, et al. HTRF analysis of soluble huntingtin in PHAROS PBMCs. Neurology. 2013;81(13):1134–1140. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55ede. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hensman Moss DJ, Robertson N, Farmer R, et al. Quantification of huntingtin protein species in Huntington's disease patient leukocytes using optimised electrochemiluminescence immunoassays. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiss A, Träger U, Wild EJ, et al. Mutant huntingtin fragmentation in immune cells tracks Huntington's disease progression. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3731–3736. doi: 10.1172/jci64565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodrigues FB, Byrne LM, Tortelli R, et al. Mutant huntingtin and neurofilament light have distinct longitudinal dynamics in Huntington's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2020 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Byrne LM, Rodrigues FB, Johnson EB, et al. Evaluation of mutant huntingtin and neurofilament proteins as potential markers in Huntington's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2018 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat7108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wild EJ, Boggio R, Langbehn D, et al. Quantification of mutant huntingtin protein in cerebrospinal fluid from Huntington's disease patients. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):1979–1986. doi: 10.1172/jci80743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monteys AM, Ebanks SA, Keiser MS, Davidson BL. CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the mutant huntingtin allele in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Agustín-Pavón C, Mielcarek M, Garriga-Canut M, Isalan M. Deimmunization for gene therapy: host matching of synthetic zinc finger constructs enables long-term mutant Huntingtin repression in mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0128-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Z, Wang C, Wang Z, et al. Allele-selective lowering of mutant HTT protein by HTT-LC3 linker compounds. Nature. 2019;575(7781):203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1722-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harding RJ, Tong YF. Proteostasis in Huntington's disease: disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(5):754–769. doi: 10.1038/aps.2018.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]