Summary

Background:

Survivors of mechanical ventilation suffer from prolonged cognitive impairment for which there is no known treatment.

Methods:

Functionally independent mechanically ventilated patients within the first 96 hours of mechanical ventilation and expected to continue for at least 24 hours were eligible for enrolment at a university hospital. Two-hundred patients were randomly assigned to receive early physical and occupational therapy (early mobilisation) or usual care. The primary outcome was cognitive impairment measured one year after hospital discharge. Patients were evaluated for cognitive impairment, neuromuscular weakness, functional independence, and quality of life upon hospital discharge and at one year. Analysis was by intention to treat. This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01777035.

Findings:

Between August 2011 and October 2019, 200 patients were enrolled and one patient withdew from the study in each group; thus 99 patients in each group were included in the analysis. The rate of cognitive impairment at one year with early mobilisation was 24·2% as compared to 43·4% with usual care (difference −19·2%; 95%CI −32·1 to −6·3%; p=0·004). Cognitive impairment was lower upon hospital discharge in the early mobilisation group (53·5% vs 68·7%; difference −15·2%; 95% CI- 28·6% to −1·7%; p=0·03). At one year, there was a reduction in ICU-acquired weakness (0% vs 14·1; difference −14·1%; 95% CI −21% to −7·3%; p<0·001) and higher physical component scores on quality of life testing (52·4 [45·3–56·8] vs 41·1 [31·8–49·4]; p<0·001) for patients in the early mobilisation group. There was no difference in rates of functional independence (64·6% vs 61·5%; difference 3%; 95% CI −10·4% to 16·4%; p=0·66) or mental component scores (55·9 [50·2–58·9] vs 55·2 [49·5–59·7]; p=0·98) in the early mobilisation and usual care groups, respectively at one year.

Interpretation:

Early mobilisation may be the first known intervention to improve long-term cognitive impairment in ICU survivors after mechanical ventilation.

Funding:

NIH/NHLBI K23 HL148387, T32 HL007605, K24HL136859, and Parker B. Francis Foundation (FP062541)

Long-term cognitive impairment affects about half of critically ill patients with respiratory failure or shock.(1–3) Although the duration of delirium has been associated with long-term cognitive dysfunction,(4) whether it is on the causal pathway remains unclear. Pharmacologic treatments for the prevention(5–7) or improvement (8, 9) of delirium have been elusive. In contrast, a nonpharmacologic approach known as early mobilisation for critically ill patients has been shown to be safe, feasible, and can shorten the duration of delirium by 50%,(10) and in turn may be an approach to prevent long-term cognitive impairment. This intervention implements physical and occupational therapy within the first days of mechanical ventilation in the throes of critical illness. Patients engage in progressive out-of-bed physical activity and simulate functional tasks such as grooming or dressing during the interruption of sedatives.(11) The simultaneous attention to physiologic and functional recovery early in the intensive care unit (ICU) course also doubles the chances of functional independence on hospital discharge.(10, 12)

Despite the short-term neurocognitive and functional gains with early mobilisation upon hospital discharge, recent ICU trials of physical therapy were unable to demonstrate any enduring benefits in physical function in the months after critical illness.(13–16) These findings question the relevance of the muscle brain crosstalk in the context of critical illness, where physical activity may also improve cognitive function.(17) However, these clinical studies differed significantly in the timing and type of the therapy sessions delivered to patients. Therapy was often delayed by over a week after mechanical ventilation,(13, 14) occurring long after the foundation for cognitive dysfunction and physical impairment was likely established. Furthermore, the lack of ICU occupational therapy(18) may have led to a focus on strengthening exercises over functional tasks such as simulation of activities of daily living, (14–16, 19, 20) which may not engage the mind enough to preserve the thinking and processing skills needed to complete complex everyday tasks. To date, there have been no clinical trials assessing the effects of early mobilisation on cognitive dysfunction at one-year. We conducted a single-center, randomised clinical trial of functionally independent mechanically ventilated patients admitted to the ICU, to determine whether early mobilisation could reduce the rates of cognitive impairment and other aspects of disability after critical illness at one year.

Methods

Consecutive patients admitted to the adult medical-surgical ICU at the University of Chicago, an urban academic hospital, were screened for eligibility from August 2011 thru October 2019. The institutional review board approved the study in July 2011. The registration of the clinical trial on clinical trials.gov occurred on January 2013 due to a clerical error. The trial was erroneously considered to be previously registered as a prior of clinical trial early mobilization(10). When the error was discovered, a new trial registration was created and no preliminary data were evaluated prior to clinical trial registration. Written informed consent was obtained by an authorized surrogate decision maker. Mechanically ventilated adults (≥18 years of age) who were functionally independent at baseline, defined as a Barthel Score of >70,(21, 22), and mechanically ventilated for less than 96 hours but expected to continue for at least 24 hours, were eligible for enrollment. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: rapidly changing neurological conditions (large stroke, status epilepticus, or intracranial hemorrhage/swelling), cardiac arrest, elevated intracranial pressure, pregnancy, terminal condition (life expectancy < 6 months), severe chronic pain syndrome, traumatic brain injury, multiple limb fractures, pelvic fractures, or more than one absent limb. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to early mobilisation (physical and occupational therapy) on the day of enrolment (intervention) or usual care with physical and occupational therapy delivered when ordered by the primary team. A computer-generated permuted balanced block randomisation scheme with random block sizes was used to allocate patients in each group. Each assignment was designated in consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelope by an investigator with no further involvement in the trial.

Patients randomised to the intervention group received physical and occupational therapy after interruption of sedation. Complete details of the therapy sessions are described elsewhere,(10, 23) but patients engaged in progressive mobilisation starting with range of motion and advancing to bed mobility activities, transferring to an upright position, sitting, standing, marching in place, and walking, as tolerated. Exercise and cueing were used to stimulate command following, increase patient interaction, and increase strength and range of motion for extremities used for functional activities. Upon sitting, patients participated in activities of daily living (ADLs) and practiced functional tasks. Progression of activities was dependent on patient tolerance and stability. Prespecified criteria that precluded the initiation or continuation of the therapy session included vital sign abnormalities such as mean arterial blood pressure < 65 mm Hg or >110 mm Hg, or systolic blood pressure >200 mm Hg; heart rate <40 beats per min or >130 beats per min; respiratory rate <5 breaths per min or >40 breaths per min; and pulse oximetry< 88% or marked ventilator asynchrony, patient distress, new arrhythmia, or concern for myocardial ischemia or airway device integrity. Contraindications for initiation of therapy also included: raised intracranial pressure; active gastrointestinal blood loss; active myocardial ischemia; continuing procedures including intermittent hemodialysis (but not including continuous ultrafiltration or hemodialysis); patient agitation that required increased sedative administration in the past 30 min; and unsecure airway.

Therapy sessions featured co-treatment with a physical and occupational therapist and continued daily throughout the hospitalization until hospital discharge or return to baseline level of function. The duration of these sessions ranged from 25 to 30 minutes.(23) Therapy was initiated in the usual care group at the direction of the primary team or upon extubation, whichever occurred first. All therapists worked primarily in the critical care setting and had prior training and extensive experience in ICU therapy practices. Therapists who conducted therapy sessions with the intervention group were distinct from the usual care group. Adverse events were collected in real-time by study personnel for intervention patients or by chart review of therapy notes for usual care patients. Patients in both the intervention and control groups were managed with goal-directed sedation to a Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) (24) determined by the primary team, underwent daily interruption of sedation,(11) and paired awakening and breathing trials (25) for weaning from mechanical ventilation. Delirium was assessed on a daily basis using the confusion assessment method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) (26, 27) during interruption of sedation.

All patients underwent cognitive testing, functional and strength assessment, and evaluation of quality of life upon hospital discharge and one year by a blinded assessor during an outpatient visit or home visit when necessary. The primary endpoint was cognitive impairment at one year defined as Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score of <26.(28) The MoCA is a 30-point screening tool that assesses multiple cognitive domains (visuospatial, naming, attention, language, verbal memory, orientation), has high sensitivity for detecting mild cognitive impairment and is considered a possible screening tool for cognitive impairment in the post-ICU population.(29–31) All patients had a strength and functional assessment completed by a physical or occupational therapist blinded to study allocation using the Medical Research Council (MRC) score (32) and Functional independence measure (FIM).(33) A combined MRC score of <48 defined the presence of ICU acquired weakness (ICU-AW).(34) Functional independence was defined as independence in ADLs and ambulation. Independence in ADLs was defined as a FIM score of ≥5 indicating completion of the ADL without physical assistance. Quality of life was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36),(35) which assesses 8 domains (physical functioning, social functioning, physical role, emotional role, mental health, pain, vitality, and general health) on a scale of 0–100 with higher scores indicating better health status. Quality of life scores were transformed to compare to population norms in the United States. Norm-based scores of ≥50 indicate scores at or above population norms and scores <40 in the physical and mental components defined quality of life scores one standard deviation below population norms. At one year after hospital discharge, patients were also interviewed to prospectively collect data on hospital, skilled nursing, long-term acute care, and rehabilitation facility admissions, corroborated by medical records to calculate the number of health care institution-free days, defined as days alive spent living at home. Deaths were also assessed using the Social Security Death Index.

Statistical Analysis

Previous research shows approximately 50% of mechanically ventilated ICU patients will be cognitively impaired at 12 months.(1, 36) We targeted a 20% reduction in cognitive impairment to 30% in intervention patients at 12 months. Sample size was estimated using the difference in proportions test for longitudinal data. (37) To detect a true difference of this magnitude with 80% power, alpha =0.05, and intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.6, required 75 subjects per arm.(38) We estimated an 18% in-hospital mortality rate in our cohort(10) and an additional 10·5% death rate by one year.(25, 39, 40) With this attrition rate, we estimated enrolling a total of 200 patients (100 per treatment group).

All analyses were performed based on an intention-to-treat approach. We used the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate to compare categorical outcomes between groups. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney two-sample rank-sum test was used to compare continuous outcomes. A modified Poisson GEE model using cluster-robust standard errors was used evaluate the average effect of the intervention on cognitive impairment.(41) To assess the effect of missing data which may not likely be missing at random, a sensitivity analysis was performed using a pattern mixture model.(42) In this analysis the degree to which the time, treatment group, and their interaction varied by study completion was assessed. In a competing risk analysis, the effect of the intervention on cognitive impairment with death as a competing risk was estimated using a Cox-proportional Hazards model.(43, 44)

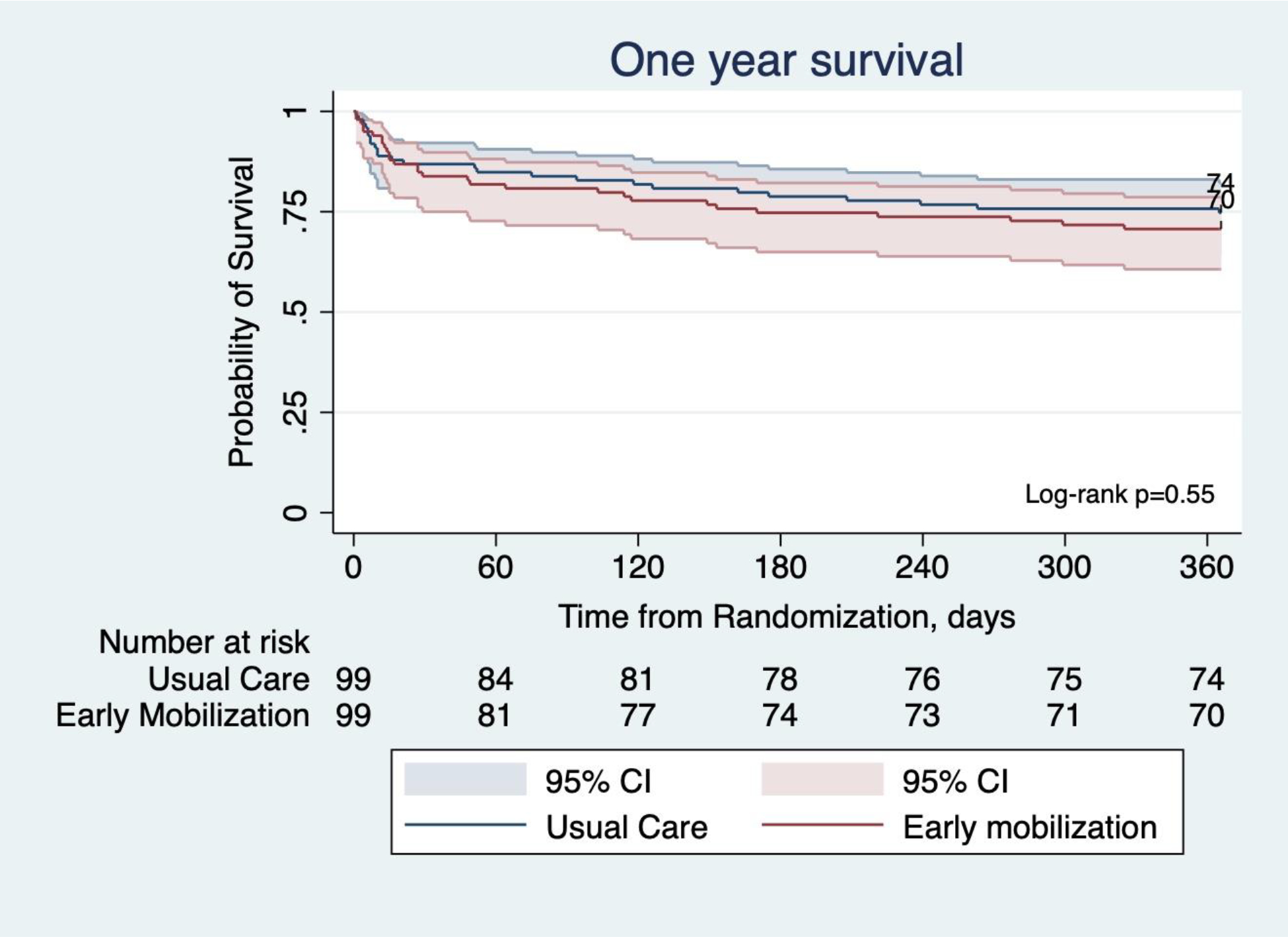

To evaluate the effect of the intervention on one year survival after randomization, we used the Kaplan-Meier procedure to estimate survival distributions in each group, with the effect of the intervention compared between groups using the log-rank test. All reported p-values are two-sided and were not adjusted for multiple testing. Significant differences between groups or across time were reported for p-value <0·05. We used Stata (StataCorp MP, 17.0) software. This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01777035.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study patients

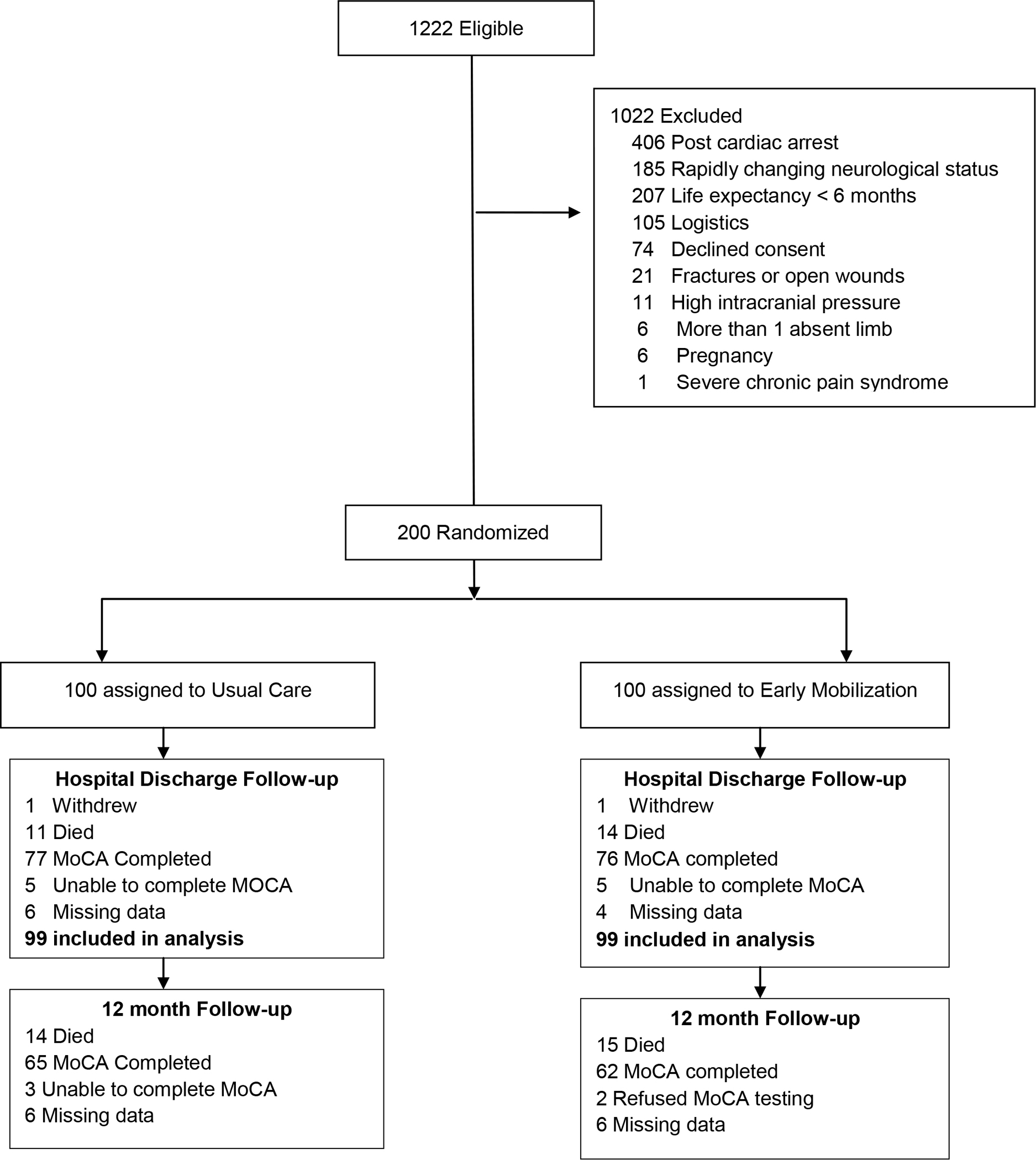

From August 2011 to October 2019, 1,222 patients met inclusion criteria, of whom 200 were ultimately enrolled and randomised (Figure 1). One patient withdrew from each group, thus 99 patients per group were included in the intention to treat analysis. Eleven (11·1%) and 14 (14·1%) died prior to hospital discharge in the usual care and intervention group, respectively. Baseline characteristics did not significantly differ between groups and are listed in Table 1 (Supplemental Table S1). At one year, there were a total of 144 survivors (n=74 usual care and n=70 intervention group; Figure 2), of which 127 (88·2%; n=65 usual care and n=62 intervention) underwent follow-up testing for cognitive impairment. Three patients in the usual care group were unable to complete the cognitive evaluation due to nonverbal status. Two patients refused completion of cognitive testing in the intervention group. Six patients in each group were lost to follow-up. Follow-up rates for secondary outcomes including quality of life, neuromuscular, and functional outcomes were similar and reported in Supplemental Table S2.

Figure 1. Flow of Participants Through the Study.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Usual care n=99 |

Intervention n=99 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Age (years) | 54·5 | [41·9–64·7] | 57·9 | [42·3–66·8] |

| Female | 44 | 44·4% | 41 | 41·4% |

| Race | ||||

| African-American | 72 | 72·7% | 68 | 68·7% |

| White, non-Hispanic | 21 | 21.2% | 26 | 26.3% |

| White, Hispanic | 4 | 4% | 4 | 4% |

| Asian | 2 | 2% | 1 | 1% |

| Barthel Index Score | 100 | [100–100] | 100 | [100–100] |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 29.8 | [24·2–35·2] | 28·2 | [23·7–33·1] |

| Less than High School Education | 8 | 7·1% | 8 | 7·1% |

| APACHE II score | 23 | [16–27] | 23 | [18–29] |

| Sepsis* | 56 | 56·6% | 63 | 63·6% |

| Diabetes | 26 | 26·3% | 23 | 23·2% |

| Primary diagnosis for intensive care unit admission | ||||

| Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure | 35 | 35·4% | 44 | 44·4% |

| Acute ventilatory failure | 24 | 24·2% | 17 | 17·2% |

| Threatened airway | 21 | 21·2% | 19 | 19·2% |

| Sepsis* | 12 | 12·1% | 14 | 14·1% |

| Liver failure | 3 | 3% | 1 | 1% |

| Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage | 1 | 1% | 2 | 2% |

| Other | 3 | 3% | 2 | 2% |

Data are expressed in n (%) and median [interquartile range] where appropriate

APACHE: Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation, scale 0–71

Sepsis includes sepsis and septic Shock as defined using Sepsis-3 Definition

Figure 2. Probability of Survival from Randomization to One Year.

Study Interventions and Hospital Data

Patients randomised to the intervention had a median of 1·1 [0.8–2] days from intubation to their first therapy session as compared to a median of 4·7 [3·3–6·8] days in the usual care group (p<0·001; table 2). Ninety-three of the 99 patients (93·9%) in the intervention group had a therapy session during mechanical ventilation within 96 hours of mechanical ventilation. Among the 6 patients who did not receive mobilisation during mechanical ventilation, the three most common reasons for deferring therapy were due to paralysis, hypotension, and transition to comfort care. Patients in the intervention group had a higher median number of therapy sessions while mechanically ventilated, in the ICU, and overall for the hospitalization than the usual care group. Six patients (6·1%) in the usual care group had therapy occur during mechanical ventilation and all were able to at least sit at the edge of the bed in the first session. Also, 48 patients (48·4%) in the usual care group received at least one therapy session in the ICU. There was a shorter time from intubation to sitting, standing, and walking in the intervention group as compared to the usual care group (supplemental table S3). In terms of adverse events, of the 696 therapy sessions delivered to the intervention group, there were 7 total adverse events (<1%). There was one arterial catheter removal and one rectal tube dislodgement and therapy had to be discontinued on 5 occasions, 3 for hemodynamic changes and 2 for respiratory distress (supplemental table S4). Of the 38 therapy sessions that occurred in the usual care group there were no adverse events (0%). Thus, adverse events were reported in 6 of the 99 patients (6%) in the intervention group and none of the patients in the usual care group (p=0.03). Duration of delirium was low overall; however patients in the intervention group had less ICU days in delirium than the usual care group (0 [0–2] vs 1 day [0–3]; p=0·005; table 2). There was no difference in ventilator free days or duration of ICU or hospital length of stay. Over half of the patients in the intervention group (51·5%) were discharged home without any need for additional therapy services as compared to one third (36·4%) in the usual care group (absolute difference 15·2%; 95% CI 1·5% to 28·8%; p=0·03).

Table 2.

Therapy Details and Hospital Outcomes

| Usual Care n=99 |

Intervention n=99 |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Time from intubation to first PT/OT session (days) | 4·7 | [3·3–6·8] | 11 | [0·8–2] | <0·001 |

| Median number of daily therapy sessions during: | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 | [0–0] | 2 | [1–3] | <0·001 |

| ICU admission | 0 | [0–1] | 4 | [2–6] | <0·001 |

| Total for hospitalization | 2 | [1–4] | 5 | [3–9] | <0·001 |

| ICU delirium duration (days) | 1 | [0–3] | 0 | [0–2] | 0·005 |

| Proportion of ICU days in delirium | 25% | [0–55·6%] | 0 | [0–28·6%] | 0·001 |

| ICU coma duration (days) | 0 | [0–1] | 0 | [0–0] | 0·62 |

| Proportion of ICU days in coma | 0% | [0–6·3%] | 0 | [0–0] | 0·67 |

| Sedation and Analgesia | |||||

| No. of patients with Propofol infusion | 71 | 71·7% | 69 | 69·7% | 0·75 |

| Median dose of Propofol (mg/day) | 1872·4 | [915·2–2803] | 1259·9 | [550·1–2615] | 0·09 |

| No. of patients with Dexmedetomidine infusion | 48 | 48·5% | 48 | 48·5% | 1 |

| Median dose Dexmedetomidine (mcg/day) | 417·8 | [99·9–1452·1] | 441·7 | [221·9–1030·3] | 0·97 |

| No of patients with Benzodiazepine infusion | 9 | 9.1% | 12 | 12·1% | 0·49 |

| Median dose of Benzodiazepine (mg/day) | 21·6 | [7·8–39·9] | 22·3 | [8·1–38·1] | 1 |

| No. Patients with Opiate infusion | 84 | 84·8% | 77 | 77·8% | 0·2 |

| Median dose Fentanyl (mcg/day) | 1647·2 | [652·2–2448·2] | 1084·1 | [531·1–2404·1] | 0·32 |

| Ventilator free days * | 24·6 | [20·8–26·1] | 25·2 | [22·9–26·4] | 0·18 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) | 3·4 | [1·9–6] | 2·7 | [1·6–4·5] | 0·11 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 5·6 | [2·9–9·8] | 4·7 | [3–8·9] | 0·51 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 9·5 | [6–17·3] | 9·7 | [5·9–16·8] | 0·8 |

| Discharge Destination | |||||

| Death | 11 | 11·1% | 14 | 14·1% | |

| Hospice | 2 | 2·0% | 2 | 2·0% | |

| Outside Hospital | 4 | 4·0% | 1 | 1% | |

| Long-term Acute Care | 7 | 7·1% | 4 | 4·0% | |

| Subacute Rehabilitation | 10 | 10·1% | 4 | 4·0% | |

| Acute Rehabilitation | 12 | 12·1% | 12 | 12·1% | |

| Home with outpatient therapy | 17 | 17·2% | 11 | 11·1% | |

| Home | 36 | 36·4% | 51 | 51·5% | 0·03** |

Data are expressed in n (%) and median [interquartile range] where appropriate

Abbreviations: ICU= intensive care unit;

ventilator-free days from study day 1 to day 28;

for comparison of home discharge without any need for services to all other possible discharge possibilities

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The proportion of patients with cognitive impairment at one year was 43·4% in the usual care group and 24·2% in the intervention group (absolute difference −19·2%; 95%CI −32·1 to −6·3%; p=0.004, Table 3). The median MoCA score at one year was higher in the intervention group in comparison to usual care (26 [24–28] vs 23 [20–26]; p<0·001). Correspondingly, upon hospital discharge patients in the intervention group had lower rates of cognitive impairment (53·5% vs 68·7%; absolute difference −15·2%; 95% CI- 28·6% to −1·7%; p=0·03). Using the modified poisson regression model, the intervention improved the risk of cognitive impairment by 19% (RR 0·81; 95% CI [0·68–0·96]; p=0·01). Risk of cognitive impairment improved over time in both groups by 2% (RR 0·98; 95%CI[0·97–0·99]; p-value= 0·001), but improved to a greater degree over time in the intervention group (group by time interaction: RR 0·97; 95%CI [0·95–0·99]; p=0·037).

Table 3.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes: Cognitive Impairment, Physical Function, and Quality of Life

| Outcome | Usual Care | Intervention | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Cognitive impairment at one-year | 43 | 43·4% | 24 | 24·2% | 0·004 |

| MoCA* score at one year | 23 | [21–26] | 26 | [24–28] | <0·001 |

| Hospital Discharge Outcome | |||||

| Cognitive impairment | 68 | 68·7% | 53 | 53·5% | 0·03 |

| MoCA score at hospital discharge | 20 | [16–23] | 23 | [19–27] | <0·001 |

| ICU-Acquired Weakness** | 38 | 38·4% | 21 | 21·2% | 0·008 |

| Total MRC Score | 49 | [44–56] | 56 | [48–60] | 0·002 |

| Functional Independence | 46 | 46·5% | 66 | 66·7% | 0·004 |

| Quality of Life | |||||

| SF-36 Physical Component Score | 39·6 | [31·8–48·5] | 45·7 | [29·7–55·6] | 0·08 |

| % with Impaired Physical Health*** | 39 | 39·4% | 29 | 29·3% | 0·13 |

| SF-36 Mental Component Score | 47·6 | [38·3–55·3] | 53·3 | [44·3–57·2] | 0·06 |

| % with Impaired Mental Health | 22 | 22·2% | 13 | 13·1% | 0·09 |

| One-Year Follow-up | |||||

| ICU-Acquired Weakness | 14 | 14·1% | 0 | 0% | <0·001 |

| Total MRC Score | 56 | [49–60] | 58 | [56–60] | 0·007 |

| Functional Independence | 61 | 61·6% | 64 | 64·6% | 0·66 |

| Quality of Life | |||||

| SF-36 Physical Component Score | 41·1 | [31·8–49·4] | 52·4 | [45·3–56·8] | <0·001 |

| % with Impaired Physical Health | 30 | 30·3% | 8 | 8·1% | <0·001 |

| SF-36 Mental Component Score | 55·2 | [49·5–59·7] | 55·9 | [50·2–58·9] | 0·98 |

| % with Impaired Mental Health | 9 | 9·1% | 7 | 7·1% | 0·8 |

Data are expressed in n (%) and median [interquartile range] where appropriate

Abbreviations: MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment, ICU: intensive care unit; MRC: medical research council; SF-36: short form 36

MoCA score<26 defined cognitive impairment

ICU-acquired weakness defined as a combined MRC score of <48

defined as at least one standard deviation below population norms (i.e. <40)

In terms of neuromuscular outcomes, patients in the intervention group had less ICU-acquired weakness on hospital discharge (21·2% vs 38·4%; absolute difference −17·2%; 95% CI −29·7% to −4·7%; p=0·008) and one year (0% vs 14·1%; absolute difference −14·1%; 95% CI −21% to −7·3%; p<0·001) than the usual care group. The rate of functional independence was higher upon hospital discharge (66·7% vs 46·5%; absolute difference 20·2%; 95% CI 6·7% to 33·7%; p=0·004) in the intervention group, but was not statistically different from the usual care group at one year (64·6% vs 61·6%; absolute difference 3%; 95% CI −10·4% to 16·4%; p=0·66). Quality of Life scores in the physical and mental health domains were not statistically different upon hospital discharge. At one year the physical component score was higher in patients randomised to intervention (52·4 [45·3–56·8] vs 41·1 [31·8–49·4], p<0·001); however, there was no statistically significant difference in mental component scores at one year between groups (55·2 [49·5–59·7] usual care vs 55·9 [50·2–58·9] intervention, p=0·98). Institution free days were not statistically different between groups (328 [121–356] usual care vs 338 [111–355] intervention; p=0·72).

Missing data and Competing risk evaluation

Using the pattern mixture model, dropout prior to completion of the one-year assessment did not alter the effect of time or intervention group on the MoCA score (suppl table S5). In a competing risk analysis of time to first cognitive test demonstrating impairment based on the cause-specific hazard ratio (with death as the competing risk), the unadjusted Cox-proportional hazards model demonstrated that the hazard ratio for intervention was 0·66 (95%CI [0·47–0·93]; p=0·019). When adjusting for APACHE II score, the hazard ratios for intervention and APACHE II score were 0·69 (95% CI [0·49–0·98]; p=0·04) and 0·97 (95% CI [0·95–0·99] p=0·01), respectively.

Discussion

In this randomised clinical trial, early mobilisation was shown to be the first known intervention to improve long-term cognitive impairment one year after patients were mechanically ventilated. Although there was no difference in functional independence between groups at one year, other aspects of long-term disability including neuromuscular weakness and quality of life related to physical health were improved with early mobilisation. This study is novel in that it is the first to demonstrate an intervention to improve long-term cognitive impairment in ICU survivors. The very early and multidisciplinary (i.e. physical and occupational therapy teams working together at the same time) are another aspect of this study’s novelty.

These findings highlight the importance of the timing and type of intervention required to improve long-term cognitive dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients. Interestingly, usual care in this study had improved such that patients received a therapy session at about 5 days after intubation, earlier than described in the intervention arms of other clinical trials of therapy in the ICU.(14–16) Specifically, Moss et al (14) mobilized patients a median of 8 days after intubation and Wright et al (16) randomised patients on the fourth day of mechanical ventilation but delivered physical therapy three days later. Despite a shorter time to therapy, patients in the usual care group still had similar rates of cognitive dysfunction at one year as previously described in mechanically ventilated patients.(2, 3) This finding suggests that the foundation for cognitive impairment similar to physical impairment is set early and requires that the intervention occurs during mechanical ventilation. Perhaps the early timing of mobilization indirectly affects cognition by sparing patients of potentially excessive sedation(45) or social isolation due to the human interaction and engagement within the first 48 hours of critical illness.

Although these findings are encouraging, they must be met with caution. The single-center design and small sample size of this trial limits the generalizability of our findings and necessitates replication. Future investigations must take into account the increased risk of adverse events in the intervention group. While this observation may be due to undersurveillance of adverse events in the control group, the higher mortality, although not statistically significant, seen in the intervention group and in other trials of early mobilization (12, 14, 46) should give one pause. Future clinical trials investigating earlier timing of therapy should invest in real-time surveillance of adverse events in both intervention and usual care groups to understand if there is excess harm. Finally, while the cognitive benefits are striking, there was no effect of early mobilization on other important outcomes such as ventilator free days, length of stay, institution free days, or mental component scores on quality of life testing. The lack of congruence of the benefits of early mobilization on cognition but not on mental component scores may suggest that improvements in cognitive scores are not completely explained by prevention of psychiatric complications which are known to alter cognition.

A recent large, multicenter, multinational clinical trial of early mobilisation (TEAM study) was unable to demonstrate any long term benefits of the intervention, including cognitive impairment at 6 months.(46) While there are many strengths of that clinical trial, there are key important differences in its implementation which may explain our disparate findings. First, the time to intervention was longer in the TEAM study intervention group (median 3 days after randomisation), with the majority of patients receiving no out of bed activity for the first two study days. In contrast, the time to intervention in our trial occured within hours after randomisation (median 2.5 hours) and a higher proportion of intervention patients ambulated in the ICU (85.9% versus 47.4%; TEAM study) (Supplemental table S6). Second, the intervention in the TEAM study did not incorporate occupational therapy which may add some cognitive benefits versus physical therapy alone. Third, there was a lower follow-up rate for the assessment of long-term cognitive impairment in the TEAM study. Finally, despite the stated goal to minimize sedation, a third to half of the TEAM study patients had a minimum RASS score of −4 or −5 indicating deep sedation in the first 5 study days. As a result, sedation was the most commonly cited barrier to mobilisation in the first 13 days of the TEAM study. Correspondingly, rates of delirium by study day varied from 25–40% in the intervention group of the TEAM study. Thus, it is possible that the high rates of delirium, coupled with deep sedation practices, and delay of therapy in the TEAM study may have confounded any treatment effect that early mobilisation may have had on cognitive impairment.

Indeed, in a landmark study of the largest description of cognitive outcomes after mechanical ventilation, Pandharipande, et al. demonstrated that the duration of delirium may be as a possible mediator of cognitive impairment.(2) Interestingly, in our study, the overall duration of ICU delirium was low in both groups, albeit shorter in patients who received early mobilisation, and yet the burden of cognitive impairment in the usual care group was substantial. This suggests that there may be other mechanisms that confer cognitive resilience in patients who receive early mobilisation. Physical activity has anti-inflammatory effects(47) and may enhance myokine secretion, which can regulate metabolism and possibly brain function.(48) The addition of occupational therapy in treatment sessions may also have a role. Occupational therapy emphasizes functional cognition, which incorporates executive function, motor skills, and performance patterns (e.g. habits or routines) to complete ADLs.(49) This approach in the context of other memory disorders such as dementia may maintain cognition and functionality in the short term.(50) Linking physical activity to task completion engages the mind in a way that passive range of motion or resistive exercises alone may not. For example, prior ICU therapy trials which relied primarily on physical therapy, but not occupational therapy, were unable to demonstrate any change in long-term cognition(19) or quality of life.(14, 20)

Limitations

In spite of the important findings, clearly this study has several limitations. First and foremost, the large effect size seen in a modestly sized study warrants replication in future work. The justification for aiming for such a large effect size in the sample size calculation was based on the recognition that this resource intensive intervention had no established long-term benefit(14, 16) and was challenging to implement on a large scale. Thus, to incentivize the adoption of this practice, we chose an effect size that would be commensurate to the investment necessary for successful implementation of early mobilisation. Another limitation was the low rate of mobilisation in the control group. Despite our own experience with early mobilisation in our ICU,(10) shifting therapy to routinely occur in the early days of mechanical ventilation was still a challenge in the usual care group. This observation emphasizes that although the necessary ingredients to build an early mobilisation program were present in terms of dedicated personnel, favorable ICU culture, and adoption of evidence-based sedation practices, they may not be sufficient. The care coordination required to align the intervention with awakening trials during windows of opportunity amidst other procedures, imaging, hemodynamic changes, and changing workflow of staff was managed by research personnel on a consistent basis for the intervention group but was lacking for the usual care patients. Early mobilisation may be considered standard of care,(51) but the usual care group’s limited adoption of this evidence-based practice is not dissimilar to the usual care described in ICUs worldwide (52–54) and underscores the potential generalizability of these findings. Thus, implementation science investigations are warranted to evaluate how best to bring evidence base to everyday clinical practice.

The screening tool for cognitive function may overestimate the prevalence of impairment; however the high sensitivity of the MoCA test (28) correspondingly indicates that the false negative rate is also relatively low. Given the high bar to demonstrate normal cognition with this tool, the observed effects of early mobilisation are especially striking. Furthermore, consensus groups have suggested the MoCA test has potential as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness.(29, 30) However, in-depth neurocognitive testing and assessment of ability to return to work to confirm the presence, degree of severity, and impact of cognitive dysfunction are warranted. The premorbid cognitive function of this cohort was not known. The nature of the intervention makes blinding of the intervention impossible. The single center design limits generalizability. Specifically the relatively low rates of coma and delirium reported in this study are not common among most ICUs.(55) However, there is a role for testing complex, multidisciplinary, collaborative, time-sensitive interventions such as early mobilisation in this setting to ensure that the intervention is delivered with high fidelity when investigating efficacy. Regardless, these findings warrant replication in a multicenter clinical trial with ICUs where delirium and coma are more common. Less than 20% of the screened population were eligible for inclusion as patients were required to be functionally independent at baseline which suggests limited applicability of this intervention. However, these criteria were necessary to ensure that patients had function to lose due to their critical illness event. Although 88% of the survivors underwent evaluation at one-year, this represents only 64% of the original clinical trial cohort. Therefore, the missing data due to death or loss to follow-up may bias these findings. In addition, post-randomization treatments such as continued rehabilitation services, cognitive therapy, or receipt of psychoactive medications were not measured and could alter these findings. There was also no adjustment for multiple testing. Finally, the small proportion of patients in the intervention group who did not receive early mobilisation coupled with the loss to follow-up, could introduce measurement bias and random confounding in spite of the intention-to-treat analysis.

Conclusions

Implementation of early mobilisation has been incorporated in ICU care bundles,(51, 52, 56) and yet has poor penetration into everyday practice. Less than 10% of mechanically ventilated patients perform any out-of-bed activity.(53) In fact, the mere presence of an endotracheal tube is a negative prognostic indicator for any physical activity.(54) Even clinical trials seeking to establish the long-term benefits of physical therapy in the ICU were unable to deliver the intervention within 72 hours of mechanical ventilation which may have led to inconclusive results.(14, 16, 46) However, previous work has shown that incorporation of early mobilisation in ICU care bundles is necessary to realize improved clinical outcomes.(57) This work also reaffirms the value added of early mobilisation even when incorporation of best practices such as interruption of sedation,(11) limiting sedation,(58) and paired awakening and breathing trials(25) have substantially decreased the duration of mechanical ventilation and delirium. The current COVID-19 pandemic has increased the numbers of community dwelling previously independent patients in need of invasive mechanical ventilation, but has also meant losing further ground on the implementation of early mobilisation.(59, 60) Given concerns related to prolonged cognitive impairment, physical disability, and poor quality of life after critical illness,(61) early mobilisation’s effects on the constellation of these sequelae warrants further investment.

To our knowledge, early mobilisation is the first intervention shown to improve long-term cognitive impairment, quality of life, and neuromuscular weakness in mechanically ventilated patients. Further investigations to validate these findings and investigate implementation strategies are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

There is no known treatment for long-term cognitive impairment after mechanical ventilation. Three systematic reviews examining the effect of early mobilization in the ICU have focused on physical and functional outcomes as opposed to cognitive effects, of which a Cochrane review was unable to determine any treatment effect due to the heterogeneity of interventions and small sample size. There is one systematic review investigating interventions that may reduce cognitive impairment in the ICU, which identified 7 studies but none had a significant effect on cognitive impairment. A Pubmed seach of “cognitive impairment after critical illness” with a restriction to human subjects and randomized clinical trials resulted in 9 citations on November 1, 2022. Two citations were publications of clinical trial protocols with no reported clinical data. Two citations did not collect data on long-term cognitive impairment. The other publications investigated the effects of early cognitive therapy with or without physical activity, high dose vitamin D, physostigmine after liver surgery, in-home cognitive, physical, and functional rehabilitation over a 3-month period after ICU discharge, or cognitive therapy alone and found no long term effects on cognitive impairment. Another clinical trial of early active exercise was recently published and demonstrated no treatment effect on cognition at 6 months after discharge.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first randomised clinical trial to improve long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of mechanical ventilation. Our study shows that the early physical and occupational therapy within the first 96 hours of mechanical ventilation is associated with a substantial improvement in cognitive impairment, neuromuscular weakness, and quality of life in the physical health domains.

Implications of all available evidence

Long-term cognitive impairment affects about half of all survivors of mechanical ventilation and yet strategies to prevent or mitigate this complication have been elusive. Our study suggests that establishing practice change to implement complex multidisciplinary interventions such as early mobilisation in the acute phase of critical illness has substantial benefits on long term disability in survivors of mechanical ventilation.

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful for the multidisciplinary team of nurses, respiratory therapists, physical and occupational therapists, housestaff, and faculty at the University of Chicago for supporting this clinical trial. Author BKP has been supported by funding from the NIH/NHLBI (K23 HL148387) and Parker B. Francis Foundation (FP062541). Authors BKP, KSW, SBP, and KCD were also supported by the NIH/NHLBI (T32 HL007605) to complete this work. Author VA was supported by NIH/NHLBI K24HL136859.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests. We declare no relevant competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Sharing:

A complete de-identified patient data set will be available to researchers to who provide a methodologically sound proposal for the purposes of achieving specific aims outlined in that proposal. Proposals should be directed to the corresponding author via email: jkress@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu and will be reviewed by the University of Chicago Critical Care Outcomes Group. Requests to access data to undertake hypothesis-driven research will not be unreasonably withheld. To gain access, data requesters will need to sign a data access agreement and to confirm that data will only be used for the agreed purpose for which access was granted. Access to the dataset will be available three years after article publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Pope D, Orme JF, Bigler ED, Larson LV. Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(1):50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1513–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girard TD, Thompson JL, Pandharipande PP, Brummel NE, Jackson JC, Patel MB, et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(3):213–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, Schmidt GA, Wright PE, Canonico AE, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):428–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page VJ, Ely EW, Gates S, Zhao XB, Alce T, Shintani A, et al. Effect of intravenous haloperidol on the duration of delirium and coma in critically ill patients (Hope-ICU): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(7):515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Bruggemann RJM, Schoonhoven L, Beishuizen A, Vermeijden JW, et al. Effect of Haloperidol on Survival Among Critically Ill Adults With a High Risk of Delirium: The REDUCE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319(7):680–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Gottfried SB. Olanzapine vs haloperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Eijk MM, Roes KC, Honing ML, Kuiper MA, Karakus A, van der Jagt M, et al. Effect of rivastigmine as an adjunct to usual care with haloperidol on duration of delirium and mortality in critically ill patients: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(20):1471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1377–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh TS, Salisbury LG, Merriweather JL, Boyd JA, Griffith DM, Huby G, et al. Increased Hospital-Based Physical Rehabilitation and Information Provision After Intensive Care Unit Discharge: The RECOVER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):901–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss M, Nordon-Craft A, Malone D, Van Pelt D, Frankel SK, Warner ML, et al. A Randomized Trial of an Intensive Physical Therapy Program for Patients with Acute Respiratory Failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(10):1101–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denehy L, Skinner EH, Edbrooke L, Haines K, Warrillow S, Hawthorne G, et al. Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical illness: a randomized controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up. Crit Care. 2013;17(4):R156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright SE, Thomas K, Watson G, Baker C, Bryant A, Chadwick TJ, et al. Intensive versus standard physical rehabilitation therapy in the critically ill (EPICC): a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2018;73(3):213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen BK. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(7):383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costigan FA, Duffett M, Harris JE, Baptiste S, Kho ME. Occupational Therapy in the ICU: A Scoping Review of 221 Documents. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(12):e1014–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, Thompson JC, Hauser J, Flores L, et al. Standardized Rehabilitation and Hospital Length of Stay Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fossat G, Baudin F, Courtes L, Bobet S, Dupont A, Bretagnol A, et al. Effect of In-Bed Leg Cycling and Electrical Stimulation of the Quadriceps on Global Muscle Strength in Critically Ill Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(4):368–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10(2):61–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohlman MC, Schweickert WD, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Feasibility of physical and occupational therapy beginning from initiation of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2089–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O’Neal PV, Keane KA, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. Core Outcome Measures for Clinical Research in Acute Respiratory Failure Survivors. An International Modified Delphi Consensus Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(9):1122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikkelsen ME, Still M, Anderson BJ, Bienvenu OJ, Brodsky MB, Brummel N, et al. Society of Critical Care Medicine’s International Consensus Conference on Prediction and Identification of Long-Term Impairments After Critical Illness. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(11):1670–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown SM, Collingridge DS, Wilson EL, Beesley S, Bose S, Orme J, et al. Preliminary Validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Tool among Sepsis Survivors: A Prospective Pilot Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(9):1108–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleyweg RP, van der Meche FG, Schmitz PI. Interobserver agreement in the assessment of muscle strength and functional abilities in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14(11):1103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS. The functional independence measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil. 1987;1:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2859–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Ely EW, Burger C, Hopkins RO. Research issues in the evaluation of cognitive impairment in intensive care unit survivors. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(11):2009–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diggle P, Diggle P. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. xv, 379 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedeker DR, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal data analysis. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Interscience; 2006. xx, 337 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):683–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikkelsen ME, Christie JD, Lanken PN, Biester RC, Thompson BT, Bellamy SL, et al. The adult respiratory distress syndrome cognitive outcomes study: long-term neuropsychological function in survivors of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(12):1307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22(6):661–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods 1997. p. 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dignam JJ, Zhang Q, Kocherginsky M. The use and interpretation of competing risks regression models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2301–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36(27):4391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, Maze M, Girard TD, Miller RR, et al. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hodgson CL, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Brickell K, Broadley T, Buhr H, et al. Early Active Mobilization during Mechanical Ventilation in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen AM, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;98(4):1154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S, Choi JY, Moon S, Park DH, Kwak HB, Kang JH. Roles of myokines in exercise-induced improvement of neuropsychiatric function. Pflugers Arch. 2019;471(3):491–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giles GM, Edwards DF, Baum C, Furniss J, Skidmore E, Wolf T, et al. Making Functional Cognition a Professional Priority. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(1):7401090010p1–p6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pimouguet C, Le Goff M, Wittwer J, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Benefits of Occupational Therapy in Dementia Patients: Findings from a Real-World Observational Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(2):509–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ely EW. The ABCDEF Bundle: Science and Philosophy of How ICU Liberation Serves Patients and Families. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, et al. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nydahl P, Ruhl AP, Bartoszek G, Dubb R, Filipovic S, Flohr HJ, et al. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients: a 1-day point-prevalence study in Germany. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jolley SE, Moss M, Needham DM, Caldwell E, Morris PE, Miller RR, et al. Point Prevalence Study of Mobilization Practices for Acute Respiratory Failure Patients in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shehabi Y, Howe BD, Bellomo R, Arabi YM, Bailey M, Bass FE, et al. Early Sedation with Dexmedetomidine in Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2506–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnes-Daly MA, Phillips G, Ely EW. Improving Hospital Survival and Reducing Brain Dysfunction at Seven California Community Hospitals: Implementing PAD Guidelines Via the ABCDEF Bundle in 6,064 Patients. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsieh SJ, Otusanya O, Gershengorn HB, Hope AA, Dayton C, Levi D, et al. Staged Implementation of Awakening and Breathing, Coordination, Delirium Monitoring and Management, and Early Mobilization Bundle Improves Patient Outcomes and Reduces Hospital Costs. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(7):885–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):e825–e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu K, Nakamura K, Katsukawa H, Elhadi M, Nydahl P, Ely EW, et al. ABCDEF Bundle and Supportive ICU Practices for Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection: An International Point Prevalence Study. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(3):e0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu K, Nakamura K, Katsukawa H, Nydahl P, Ely EW, Kudchadkar SR, et al. Implementation of the ABCDEF Bundle for Critically Ill ICU Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-National 1-Day Point Prevalence Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:735860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A complete de-identified patient data set will be available to researchers to who provide a methodologically sound proposal for the purposes of achieving specific aims outlined in that proposal. Proposals should be directed to the corresponding author via email: jkress@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu and will be reviewed by the University of Chicago Critical Care Outcomes Group. Requests to access data to undertake hypothesis-driven research will not be unreasonably withheld. To gain access, data requesters will need to sign a data access agreement and to confirm that data will only be used for the agreed purpose for which access was granted. Access to the dataset will be available three years after article publication.