Abstract

Prior research has examined the association between flourishing and suicidal ideation, but it is unknown whether this association is causal. Understanding the causality between flourishing and suicidal ideation is important for clinicians and policymakers to determine the value of innovative suicide prevention programs by improving flourishing in at-risk groups. Using a linked nationwide longitudinal sample of 1619 middle-aged adults (mean age 53, 53% female, 88% White) from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), this retrospective cohort study aims to assess the causal relationship between flourishing and suicidal ideation among middle-aged adults in the US. Flourishing is a theory-informed 13-scale index covering three domains: emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Suicidal ideation was self-reported in a follow-up interview conducted after measuring flourishing. We estimated instrumental variable models to examine the potential causal relationship between flourishing and suicidal ideation. High-level flourishing (binary) was reported by 486 (30.0%) individuals, and was associated with an 18.6% reduction in any suicidal ideation (binary) (95% CI, − 29.3– − 8.0). Using alternative measures, a one standard deviation increase in flourishing (z-score) was associated with a 0.518 (95% CI, 0.069, 0.968) standard deviation decrease in suicidal ideation (z-score). Our results suggest that prevention programs that increase flourishing in midlife should result in meaningful reductions in suicide risk. Strengthening population-level collaboration between policymakers, clinical practitioners, and non-medical partners to promote flourishing can support our collective ability to reduce suicide risks across social, economic, and other structural circumstances.

Subject terms: Health care, Medical research, Risk factors, Psychiatric disorders, Trauma, Comorbidities

Introduction

Suicide is a significant public health crisis in the U.S. From 1999 to 2019, suicide rates among adults aged 45–64 in the U.S. increased by 60%, from 6.0 to 9.6 cases per 100 000 population in females and 43.8% from 20.8 to 29.9 in males1. Early intervention and suicide prevention programs are crucial to reduce the risks of suicide2,3. Existing suicide prevention efforts are dominated by risk reduction strategies4,5. However, meta-analyses have found that common risk factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, psychological factors, physical health, and social relationships, yield limited predictive power for fatal and nonfatal suicidal behavior6,7. Besides, suicide risk factors are typically identified through association studies and do not fully account for potential confounding6.

With the increasing availability and acceptance of integrative health practices, recent literature has suggested strength-based positive psychological interventions as a promising new approach to preventing suicide8–11. These well-being-focused suicide prevention programs can enhance social determinants of health (SDoH) via early intervention among high-risk populations, thus reducing individual and structural burdens of suicidal behaviors.

Flourishing reflects a comprehensive assessment of well-being, with multiple complementary frameworks currently being the subject of research12–15. In this study, we focus on Keyes’ framework15,16, which combines hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Table 1). The hedonic framework considers emotional well-being (e.g., happiness, life satisfaction). The eudaimonic framework addresses psychological well-being (e.g., mastery of life, personal growth) and social well-being (e.g., social integration, social cohesion)13–15. Flourishing conceptually overlaps with mental well-being and can contribute to a novel approach to reducing suicidal ideation. Recently, human flourishing has been suggested as a conceptual touchstone for prevention-related priorities and objective endpoints in the 2020s17. Previous studies have found flourishing associated with a decreased risk of suicidal ideation18,19. However, we are unaware of any studies that have assessed the causal effect of flourishing on suicidal ideation.

Table 1.

Measures of primary exposure (Flourishing Subscales and Domains), primary outcome and instrumental variables.

| Constructs | Measures | Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Primary exposures: flourishing (measured before suicidal ideation) | ||

| Items | ||

| Flourishing domain 1: eudaimonic well-being | ||

| Psychological well-being | 1 Strongly agree; 2 Somewhat agree; 3 A little agree; 4 Neither agree or disagree; 5 A little disagree; 6 Somewhat disagree; 7 Strongly disagree. (R) indicates reverse coding | |

| 1. Autonomy | I am not afraid to voice my opinions, even when they are in opposition to the opinions of most people. (R) | |

| My decisions are not usually influenced by what everyone else is doing. (R) | ||

| I tend to be influenced by people with strong opinions | ||

| I have confidence in my own opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus. (R) | ||

| It’s difficult for me to voice my own opinions on controversial matters | ||

| I tend to worry about what other people think of me | ||

| I judge myself by what I think is important, not by the values of what others think is important. (R) | ||

| 2. Environmental mastery | In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live. (R) | |

| The demands of everyday life often get me down | ||

| I do not fit very well with the people and the community around me | ||

| I am quite good at managing the many responsibilities of my daily life. (R) | ||

| I often feel overwhelmed by my responsibilities | ||

| I have difficulty arranging my life in a way that is satisfying to me | ||

| I have been able to build a living environment and a lifestyle for myself that is much to my liking. (R) | ||

| 3. Personal growth | I am not interested in activities that will expand my horizons | |

| I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world. (R) | ||

| When I think about it, I haven’t really improved much as a person over the years | ||

| I have the sense that I have developed a lot as a person over time. (R) | ||

| For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth. (R) | ||

| I gave up trying to make big improvements or changes in my life a long time ago | ||

| I do not enjoy being in new situations that require me to change my old familiar ways of doing things | ||

| 4. Positive relations with others | Most people see me as loving and affectionate (R) | |

| Maintaining close relationships has been difficult and frustrating for me | ||

| I often feel lonely because I have few close friends with whom to share my | ||

| I enjoy personal and mutual conversations with family members and friends. (R) | ||

| People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others (R) | ||

| I have not experienced many warm and trusting relationships with others | ||

| I know that I can trust my friends, and they know they can trust me. (R) | ||

| 5. Purpose in life | I live one day at a time and don’t really think about the future | |

| I have a sense of direction and purpose in life. (R) | ||

| I don’t have a good sense of what it is I’m trying to accomplish in life | ||

| My daily activities often seem trivial and unimportant to me | ||

| I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality. (R) | ||

| Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them. (R) | ||

| I sometimes feel as if I’ve done all there is to do in life | ||

| 6. Self-acceptance | When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out. (R) | |

| In general, I feel confident and positive about myself. (R) | ||

| I feel like many of the people I know have gotten more out of life than I have | ||

| I like most parts of my personality. (R) | ||

| In many ways I feels disappointed about my achievements in life | ||

| My attitude about myself is probably not as positive as most people feel about themselves | ||

| When I compare myself to friends and acquaintances, it makes me feel good about who I am. (R) | ||

| Social well-being | 1 Strongly agree; 2 Somewhat agree; 3 A little agree; 4 Neither agree or disagree; 5 A little disagree; 6 Somewhat disagree; 7 Strongly disagree. (R) indicates reverse coding | |

| 1. Meaningfulness of society | The world is too complex for me | |

| I cannot make sense of what’s going on in the world | ||

| 2. Social integration | I don’t feel I belong to anything I’d call a community | |

| I feel close to other people in my community (R) | ||

| My community is my source of comfort (R) | ||

| 3. Acceptance of others | People who do a favor expect nothing in return (R) | |

| People do not care about other people’s problems | ||

| I believe that people are kind (R) | ||

| 4. Social contribution | I have something valuable to give to the world (R) | |

| My daily activities do not create anything worthwhile for my community | ||

| I have nothing important to contribute to society | ||

| 5. Social actualization | The world is becoming a better place for everyone (R) | |

| Society has stopped making progress | ||

| Society isn’t improving for people like me | ||

| Flourishing domain 2: Hedonic well-being | ||

| Emotional well-being | ||

| 1. Positive affect | During the past 30 days, how much of the time did you feel full of life, happy, cheerful, in good spirits, calm or peaceful, satisfied? | 1 All of the time; 2 Most of the time; 3 Some of the time; 4 A little of the time; 5 none of the time |

| 2. Life satisfaction | How would you rate your life overall these days? | 0 (the worst possible) to 10 (the best possible) |

| Primary outcome: suicidal ideation (measured after flourishing) | ||

| Self-reported suicidal ideation from Mood and Anxiety symptoms questionnaire (MASQ) | during the past week, how much you have felt or experienced thoughts about death or suicide? | transformed into binary: have suicidal ideation (a little bit, moderately, quite a bit, or extremely vs. non-suicidal ideation (no) |

| Instrumental variables: adverse childhood experiences, daily discrimination | ||

| Adverse childhood experiences | Physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse, parental divorce, parental depression, and alcohol or drug abuse of any parent | Binary (yes/no) |

| Daily discrimination | How often on a day-to-day basis do you experience each of the following types of discrimination? | Never, rarely, sometimes, often |

| You are threatened or harassed | ||

| You are called names or insulted | ||

| People act as if they think you are not as good as they are | ||

| People act as if they think you are dishonest | ||

| People act as if they are afraid of you | ||

| People act as if they think you are not smart | ||

| You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores | ||

| You are treated with less respect than other people | ||

| You are treated with less courtesy than other people | ||

We used two algorithms to measure flourishing based on the theory. (1) Binary Scoring Algorithm: For each of the 13 scales above (6 psychological + 5 social wellbeing + 2 emotional wellbeing), we computed binary measures, where cut-points were applied to code the upper third of the distribution of each summed scale as one and the lower two-thirds as zero. Flourishing was then indicated when six of the 11 psychological and social well-being scales were equal to one, and at least one of the two emotional well-being scales was equal to one. A second binary measure was constructed in the same way, but omitted the 2 emotional well-being scales such that the measure was equal to one when six of the 11 psychological and social well-being scales were equal to one and zero otherwise. (2) Z-score Scoring Algorithm: All 13 scales are summed and converted to a z-score. A second measure also summed the measure, but omitted the 2 emotional well-being items, and was then converted to a z-score. Flourishing was measured temporally prior to suicidal ideation.

This study is the first to examine the causal effect of flourishing on suicidal ideation. Our design is strengthened by the ability to construct a linked, nationally representative, longitudinal dataset where flourishing was measured temporally before suicidal ideation. To estimate the causal association between flourishing and suicidal ideation4,20,21, we conduct instrumental variables (IV) analyses22–24. IV is a technique used in health economics, psychiatry, and other areas of medicine to remove parameter bias arising from self-selection, random measurement error, and reverse causation (also called simultaneity bias) when analyzing observational data25,26.

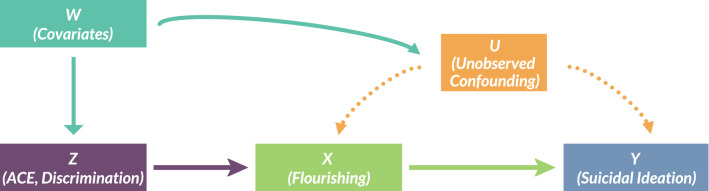

IV analysis requires the identification of instruments: exogenous variables that influence the factor of interest (primary exposures) but have no direct influence on the primary outcome, conditional on included covariates. We use two valid instruments to determine the causal effect of flourishing on suicidal ideation. These instruments are chosen based on theoretical considerations. The stress-diathesis theory implies that suicidal ideation is due to distal factors (diathesis) from early life and proximal factors from recent stressors27. We thus chose two instruments: (1) adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as a diathesis factor measuring childhood trauma that has been demonstrated to have epigenetic effects28–31; and (2) daily discrimination as a stressor factor measuring perceptions of discrimination32. Figure 1 shows a directed acyclic graph (DAG) and temporal ordering of primary exposures to outcomes. The key assumption is that both ACEs and daily discrimination are exogenous and should only affect suicidal ideation through their inhibitory impacts on flourishing, conditional on covariates.

Figure 1.

Directed Acyclic Graph.The relationship between flourishing, X, and suicidal ideation, Y, can be estimated using our set of conditional instruments (ACEs, daily discrimination), Z, that are valid conditional on included covariates, W. Y (suicidal ideation) was measured after X (flourishing). W includes severe psychological distress, depression, anxiety, chronic pain, a set of five inflammatory markers, substance use, binge drinking, health status, personality factors, health insurance, and socioeconomic factors (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, household income adjusted for household size). The function of Z, conditional on W, in this model is to remove the confounding effects of U (which is a set of unobserved confounders in the error term of the regression analysis) regarding the effect of X on Y. In other words, all these variables in W are included in closing off backdoor paths (non-causal paths) between X and Y, or in econometric terms, to remove any correlation between the set of instruments and the error term.

Results

Among 1619 participants, 850 (5.5%) were women, and 769 (47.5%) were men (mean age, 53.4, standard deviation (SD) 12.7 years). Table 2 summarizes the baseline characteristics of our study cohort. 202 participants (12.6%) endorsed suicidal ideation. High-level flourishing (binary) was reported by 486 participants (30%), the mean (SD) of daily discrimination was 12.9 (4.6), and the mean (SD) of ACEs was 3.5 (1.9).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants Included in the study sample (N = 1619)a.

| Characteristics | N (%)/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Suicidal Ideation Measures | |

| Suicidal Ideation (binary), N (%) | 202 (12.5%) |

| Suicidal Ideation, (Range 1–5), Mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Flourishing Measures | |

| Continuous, (Range:119–406.5), Mean (SD) | 311.9 (45.2) |

| Continuous, (Range:115–392), Mean (SD) | 300.7 (43.8) |

| Binary, N (%) | 486 (30.0%) |

| Binary (eudaimonic only), N (%) | 635 (39.2%) |

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 53.4 (12.7) |

| Ages 45–55, N (%) | 430 (26.6%) |

| Ages 55–64, N (%) | 393 (24.3%) |

| Ages 65 and older, N (%) | 348 (21.5%) |

| Female, N (%) | 850 (52.5%) |

| Male, N (%) | 769 (47.5%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, N (%) | 14 (0.9%) |

| Black, N (%) | 68 (4.2%) |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 62 (3.8%) |

| Other Race, N (%) | 102 (6.3%) |

| White, N (%) | 1431 (88.4%) |

| Married, N (%) | 1124 (69.4%) |

| Separated, N (%) | 26 (1.6%) |

| Divorced, N (%) | 215 (13.3%) |

| Widowed, N (%) | 76 (4.7%) |

| High School, N (%) | 273 (16.9%) |

| Bachelor's, N (%) | 401 (24.8%) |

| Graduate School, N (%) | 435 (26.9%) |

| Household Income (equivalized) $1s, Mean (SD) | 83,874.3 (66,919.6) |

| Insurance and Health | |

| Health Insurance, N (%) | 1509 (93.2%) |

| Poor/Fair Health Status, N (%) | 170 (10.5%) |

| Chronic Pain, N (%) | 586 (36.2%) |

| Inflammatory Markers, Mean (SD) | |

| C-reactive protein, (ug/ml) (range: 0.05–79.3) | 2.8 (4.8) |

| Fibrinogen, (mg/dl) (range: 45–759) | 340.7 (79.0) |

| Interleukin-6, (pg/ml) (range: 0.06–145.05) | 1.2 (4.0) |

| E-Selectin, (ng/ml) (range: 0.09–175) | 40.7 (20.2) |

| Intercellular adhesion molecule-1, (ng/ml) (range: 30–3334) | 278.9 (143.8) |

| Psychological/Mental Health Measures | |

| Neuroticism (range: 1–4) | 2.0 (0.6) |

| Conscientiousness (range: 1–4) | 3.4 (0.5) |

| Severe Psychological Distress, N (%) | 44 (2.7%) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder, N (%) | 36 (2.2%) |

| Depression, N (%) | 157 (9.7%) |

| Substance/Alcohol Abuse | |

| Substance Use, N (%) | |

| 5 + Drinks (monthly frequency), mean (SD) (range: 0–30) | 0.6 (2.8) |

| Instrumental Variables | |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences, mean (SD) (range: 0–8) | 3.5 (1.9) |

| Daily Discrimination, mean (SD) (range: 9–33) | 12.9 (4.6) |

SD Standard Deviation.

aData were compiled from the MIDUS 2, MIDUS Refresher, MIDUS Refresher Biomarker Project, and MIDUS 2 Biomarker Project.

Standard overidentification tests were performed using the two-stage limited information maximum likelihood (2SLIML) model. Hansen’s J statistic (a test of the joint null hypothesis that the instruments are uncorrelated with the error term and correctly excluded from the estimated equation, assuming at least one instrument is valid) showed that the null hypothesis could not be rejected in any 2SLIML specification.

The strength of the set of instruments could only be tested using the 2SLIML model. The Montiel-Olea-Pflueger weak instrument test33, a test that is robust to both heteroskedasticity and serial correlation, yielded an effective F-statistic of 15.52, greater than the relevant critical value of 8.38, indicating less than 5% worst-case bias. Hansen’s J failed to reject the hypothesis that no instrument was correlated with the error term, given that the other instrument is valid. Finally, an endogeneity test rejected the hypothesis that flourishing is exogenous. See Table S1 in the Supplementary.

The effect of achieving the standard binary definition of flourishing using the bivariate probit model is a 18.6% reduction (95% CI: 8.0, 29.3) in binary suicidal ideation (Table 3, Table S2 in Supplementary). This is not statistically different from the 44.7 percentage point reduction (95% CI: 11.5, 77.8) in binary suicidal ideation when the 2SLIML model is used.

Table 3.

Effect of Flourishing on Suicidal Ideationa.

| Measures | Marginal Effect | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flourishing (Hedonic and Eudaimonic) | ||||

| Binary Flourishing, Binary Suicidal Ideation | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.447 | − 0.778 | − 0.115 | 0.008 |

| Bivariate Probit | − 0.186 | − 0.293 | − 0.08 | 0.001 |

| Continuous Flourishing (z-score), Binary Suicidal Ideation | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.228 | − 0.4 | − 0.06 | 0.009 |

| Instrumental Variables Probit | − 0.22 | − 0.382 | − 0.057 | 0.008 |

| Binary Flourishing, Continuous Suicidal Ideation (z-score) | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.959 | − 1.84 | − 0.079 | 0.033 |

| Continuous Flourishing (z-score), Continuous Suicidal Ideation (z-score) | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.518 | − 0.968 | − 0.069 | 0.024 |

| Abbreviated Flourishing (Eudaimonic Only) | ||||

| Binary Flourishing, Binary Suicidal Ideation | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.414 | − 0.737 | − 0.091 | 0.012 |

| Bivariate Probit | − 0.247 | − 0.38 | − 0.115 | < 0.001 |

| Continuous Flourishing (z-score), Binary Suicidal Ideation | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.231 | − 0.409 | − 0.053 | 0.011 |

| Instrumental Variables Probit | − 0.222 | − 0.39 | − 0.053 | 0.01 |

| Binary Flourishing, Continuous Suicidal Ideation (z-score) | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.928 | − 1.767 | − 0.089 | 0.03 |

| Continuous Flourishing (z-score), Continuous Suicidal Ideation (z-score) | ||||

| Instrumental Variables 2SLIML | − 0.523 | − 0.984 | − 0.062 | 0.026 |

2SLIML two-stage limited information maximum likelihood.

aControlled variables include age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, household income, health insurance, personality factors, substance use, binge drinking, health status, generalized anxiety, depression, severe psychological distress, 5 inflammatory markers, and chronic pain.

Our sensitivity analyses yielded additional findings. We find that the hedonic aspect, while important conceptually, does not make a difference in terms of reducing binary suicidal ideation when using a binary flourishing variable. This may be a special case only relevant to suicidal ideation that may not apply in other applications. The relevant statistics for the 2SLIML model that uses a binary flourishing variable that omits the hedonic scales (these statistics are not available for bivariate probit models) are as follows: Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 15.46 > 7.7 critical value; Hansen’s J p = 0.55; endogeneity p = 0.005). See Table S1 in the Supplementary. As shown in Table 3, there is no statistical difference in the results when this is done.

In addition, as shown in Table 3, the continuous version of flourishing yields a similarly-size parameter, whether or not the hedonic aspects are included and whether or not 2SLIML or instrumental variables probit is used as an estimator. The relevant test statistics for the 2SLIML are as follows (this set of statistics is not available for the instrumental probit model): continuous flourishing (hedonic and eudaimonic): Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 16.83 > 5.14 critical value; Hansen’s J p = 0.53; endogeneity p = 0.1; continuous flourishing (eudaimonic only): Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 16.04 > 4.97 critical value; Hansen’s J p = 0.44; endogeneity p = 0.01.

Further down in Table 3, the binary version of the flourishing combined with the z-score of suicidal ideation yields similarly sized parameters, whether or not the hedonic aspects are included, with suicidal ideation being reduced 0.959 standard deviations (95% CI: 0.079, 1.840) when flourishing is present (Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 15.53 > 8.38 critical value; Hansen’s J p = 0.50; endogeneity p = 0.02). The corresponding parameters when only the eudaimonic aspects of flourishing are included is 0.928 (95% CI: 0.089, 1.767) (Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 15.55 > 7.67 critical value; Hansen’s J p = 0.96; endogeneity p = 0.02). See Supplementary Table S5.

Finally, in Table 3, the z-score version of flourishing combined with the z-score of suicidal ideation yields similarly sized parameters, whether or not the hedonic aspects are included, with the reduction being approximately half a standard deviation when flourishing increases by one standard deviation: − 0.518 (95% CI: − 0.968, − 0.069) (Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 16.83 > 5.09 critical value; Hansen’s J P = 0.99; endogeneity p = 0.04). The corresponding parameter when only the eudaimonic aspects of flourishing are included is − 0.523 (95% CI: − 0.984, − 0.062) (Montiel-Olea-Pflueger Effective F 16.04 > 4.92 critical value; Hansen’s J p = 0.92; endogeneity p = 0.04). See Table S6 in the Supplementary. All of the above models correct for measurement error and omitted variable bias34–36.

Discussion

This is the first study to clarify the nature of the association between flourishing and suicidal ideation. Using the IV approach, we corrected for bias in the estimated parameters of flourishing due to omitted variables or measurement error35. Reverse causation was ruled out by the temporal ordering of the data (suicidal ideation was measured after flourishing). Our findings demonstrated the negative associations of ACEs and discrimination with flourishing37–39, as well as the effect of flourishing on reducing suicidal ideation18,19. Results are larger in magnitude but consistent with previous studies, most of which used cross-sectional designs. Flourishing inhibits suicidal ideation both when defined as a threshold to achieve and as a continuous set of measures to improve. Flourishing also need not include hedonic measures, at least in this application.

The first major strength of our investigation is the use of instrumental variables analysis to account for unmeasured confounding variables40,41. We determined that ACEs and daily discrimination are negatively correlated with flourishing at approximately the same magnitudes (when z-scores are used), suggesting that stress and diathesis factors damage flourishing similarly. Emerging literature, based on the cross-sectional National Survey of Children’s Health, has revealed the negative impact of ACEs on childhood flourishing42,43. Similarly, others have shown an association between daily discrimination and flourishing17. We extended such dose–response relationships in the context of the U.S. midlife population. Existing positive psychology and human flourishing theories can explain our findings. People who are flourishing will thrive amid adversity by maximizing their potential by changing abilities and limitations14, which reduces the risks of suicidal ideation. By contrast, those who lack purpose in life (psychological aspect of flourishing) are more likely to consider suicide when exposed to childhood trauma or daily discrimination14.

The causal effect of flourishing on reducing suicidal ideation suggests flourishing can serve as a target of suicide prevention, shifting the paradigm from the traditional notion of risk reduction towards a more holistic approach—focusing on wellbeing and social determinants of health (SDoH) including flourishing, especially by enhancing social networks and social connectedness17. Our second major contribution is to parse the key constructs of flourishing to those that are modifiable and can reduce suicidal ideation via clinical or population-level interventions. Using multiple flourishing measures, we found that the hedonic aspect of flourishing does not add additional magnitude to the measured relationship compared with the situation when we only included the eudaimonic aspects of flourishing. While this may not be the case for other outcomes, this is nevertheless an important issue, as the eudaimonic aspects of flourishing are more modifiable and can be taught through direct interventions (aimed at improving psychological and social well-being measured in our study). Improving the eudaimonic aspects of flourishing may improve the hedonic aspects of flourishing44. Evidence-based positive psychology interventions (focusing on systematically promoting mindfulness, patient-caregiver dyadic interpersonal interactions, and coping) have been associated with increased positive affect and reduced depression and mortality in medical populations10,12.

Flourishing-based suicide prevention can be useful and effectively implemented in both clinical care and population-based settings12,12. Within psychiatry, screening for flourishing may be a promising way to detect individuals susceptible to childhood trauma or stress that could end in suicide. Treating patients using the lens of flourishing may help clinicians provide better patient-centered care that is more holistic and more acceptable to patients42,45. Flourishing-centered suicide prevention programs may be especially relevant to suicide attempts encountered in the emergency department setting given the high suicide rates of 178 per 100 000 person-years in the first three months after discharge and the lack of care coordination with the warm handoff46,47. Family-focused interventions, as promoted by the Institute of Medicine, may be pivotal to promoting flourishing by supporting family connections37,48. Equally important is to promote flourishing among physicians and healthcare workers who may encounter patients with suicidal ideation, as improving the personal growth and environmental mastery of physicians and healthcare workers may reduce their risks of burnout49.

At the population level, flourishing-based suicide prevention could be achieved effectively with evidence-based programs and policy efforts across the sectors of health care, education, and human services17. On the one hand, it is key to implement a collaborative and holistic approach to address structural factors (e.g., policies that improve education, income, reduce racism and other forms of discrimination, etc.), create safe and connected families, and build connected communities as a foundation for intergenerational flourishing. On the other hand, our findings highlight that the broad dissemination of individual-oriented “positive psychology” interventions (e.g., strength-based asset development, emotional regulations, positive interpersonal skills)12,13 can reduce suicide via a more effective public health approach. These individually-oriented interventions can amplify the positive effects of other policies focused on structural change. Our findings emphasize the importance of flourishing in reducing suicidal ideation as an urgent consideration with potential short-term and longer-term benefits.

Limitations

Our study had limitations. First, studies of attrition and retention in MIDUS have revealed that White, female, married people with higher education and better health were more likely to stay in subsequent waves50. Given the possible disproportionate exposure to ACEs and discrimination among vulnerable populations (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, males), this attrition bias suggests that our findings may be understated. However, the recently NIA-funded MIDAS Retention Early Warning project reinstated a substantial portion of dropouts and provided valuable opportunities to investigate the extent to which flourishing among those who dropped out would cause reduced suicidal ideation43. Second, the measure of suicidal ideation was self-reported, which may underestimate suicide risks. In addition, we only used a single question to measure suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation is a multifaceted issue, and there are full instruments developed for this single issue, but to our knowledge, such instruments are not available in data that also contains measures of flourishing. Third, our operationalization of flourishing is relatively narrow, whereas alternative measures of flourishing cover a broader array of life domains. Future studies are encouraged to validate the findings in this study using a more diverse sample and other measures of flourishing. Lastly, although we included all common suicide risks in our data, results may be biased if some risk factors for suicide that correlate with our instruments are unmeasured.

In sum, risk-reduction suicide interventions have focused on teaching people how not to die, whereas flourishing-focused suicide prevention teaches us how to live. Our evidence showing the possible causal effect of promoting flourishing on reducing suicidal ideation provides a promising future direction for a more effective and scalable approach.

Methods

Data and participants

We obtained data from four samples of the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study that allowed us to construct two longitudinal cohorts, which we then combined51. The first is the MIDUS 2 Project (2004–2006)52, which contains a 10-year follow-up of participants from the original MIDUS study. The second is the MIDUS 2 Biomarker Project (2004–2009)53, a longitudinal follow-up of MIDUS 2, containing biological assessments and information on suicidal ideation. The third is the MIDUS Refresher Study (2011–2014)54, designed to replenish the MIDUS cohort. The fourth is from the MIDUS Refresher Biomarker study (2012–2016)55, which paralleled the MIDUS 2 Biomarker Project and was a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS Refresher Study, containing biological assessments and information on suicidal ideation. All participants gave informed consent56. The response rates for the four samples were 81.0%, 39.3%, 73.0%, and 41.5%, respectively. Following previous research40,57, the current study linked these four samples (n = 1619). We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. This study was not considered human subjects research by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, as defined by federal regulations at 45 CFR 46.102 (DHHS) and/or 21 CFR 50.3 (FDA).

Measures

The primary outcome, primary exposure, and instrumental variable described below have a clear temporal ordering (Fig. 1). Suicidal ideation is temporally preceded by flourishing, which is temporally preceded by the set of instrumental variables (all of which look back to exogenous events from the past).

Primary outcome: suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation is a single question from the Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire (MASQ) available in both the MIDUS 2 Biomarker and Refresher Biomarker projects58, asking the respondent, “during the past week, how much you have felt or experienced thoughts about death or suicide?” Because we want to capture any amount of suicidal ideation, we transformed this question into a binary variable (having “a little bit” up to “extreme” thoughts of suicide) vs. non-suicidal ideation cases (having “no” thoughts of suicide). Binary measures of suicidal ideation are commonly employed when measuring self-report suicidal ideation using similar measures of MASQ like PHQ-959 (e.g., dichotomizing the 4-point scale responses60,61) and have been found to be valid for clinical assessment41. For sensitivity analyses, following a recent review regarding the effectiveness of different suicide screening measures62, we transformed the original suicidal ideation question into a z-score, which is expressed in standard deviations and avoids any loss of data.

Primary exposure: flourishing

Flourishing is based on a 13-scale index measuring emotional well-being (hedonic aspect), psychological well-being, and social well-being (eudaimonic aspects) (Table 1)15.

Emotional well-being contains two subscales. These include a 6-item measure of positive affect, with each item being measured on a 5-point scale (1 = none of the time, 2 = a little of the time, 3 = some of the time, 4 = most of the time, 5 = all of the time), and a single life satisfaction item measured on a 10-point scale (1 = worst possible life overall these days to 10 = best possible life overall these days).

Psychological well-being includes 6 subscales. Each item is coded on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Items are reverse coded as indicated in Table 1.

Social well-being includes 5 subscales, one with 2 items and the remaining each having 3 items. Each item is scored on a 7-point scale and coded in the same way as the items for psychological well-being. Items are reverse coded as indicated in Table 1.

Keyes’ binary measure of flourishing (high-level flourishing) is constructed using the following algorithm: for each of the 13 scales described above, we computed binary measures, where cut-points were applied to code the upper third of the distribution of each scale as one, and the lower two-thirds as zero. Flourishing was then indicated when six of the 11 psychological and social well-being scales were equal to one, and at least one of the two emotional well-being scales was equal to one16.

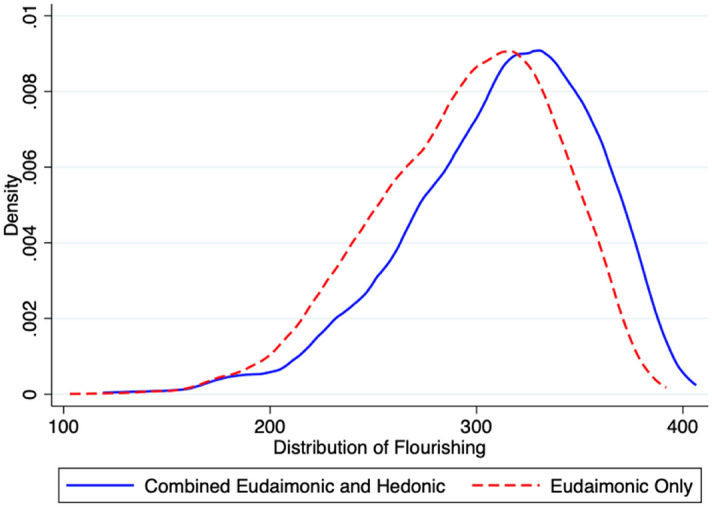

To facilitate sensitivity analyses, we also constructed additional flourishing measures. These alternative measures are designed to determine whether outcomes are sensitive to the inclusion/exclusion of the hedonic aspect of flourishing and whether flourishing may be not only be considered as a state (whether an individual is in the upper third of emotional, psychological, and social well-being), but also as a process (improvements in emotional, psychological, and social well-being are valuable and desirable as one moves toward the upper one-third threshold goal). We thus constructed an alternative binary measure that omitted the two emotional well-being (hedonic) scales. We also constructed two continuous measures of flourishing (one that included both the hedonic and eudaimonic scale sets, and one that only included the eudaimonic scale set) by summing all relevant scales and converting the sum to a z-score15–17. The distribution of each continuous measure is approximately normal. See Fig. 2. These scales are described in Table 1, and the relevant scoring algorithms are described in the footnotes to the table.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Flourishing (Continuous Measures).

Instrumental variables: ACEs and daily discrimination

Exposure to ACEs is a summed score of 8 binary (yes/no) categories of adverse experiences (physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse, parental divorce, parental depression, and alcohol or drug abuse of any parent) occurring before age 18 (range 0–8, Table 1). This measure has been validated and is consistent with empirical applications29,37,63 and theory28. We transformed this scale into a z-score.

Daily discrimination is measured using the validated daily perceived discrimination scale (Table 1)32,64. Responses to each question are coded 0–3 (never, rarely, sometimes, often) and then summed. We transformed this scale into a z-score.

Covariates

We controlled for potential pathways between the instrumental variables and suicidal ideation to ensure that the instruments only affect suicidal ideation through their impact on flourishing. We thus include the following known risk factors for suicidal ideation: (1) socioeconomic characteristics, including participants’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational level, household income (adjusted for household size), and health insurance status; (2) physical health, including diminished health status (poor health or fair health), binge drinking (number of days with more than five drinks per day in the past 30 days), substance use (ever used the following in the past 12 months either without a doctor's prescription, in larger amounts than prescribed, or for a longer period than prescribed: sedatives, tranquilizers, stimulants, painkillers, antidepressants, inhalants, marijuana/hashish, cocaine/crack, LSD/hallucinogens, heroin), any chronic pain (yes/no), and a set of 5 inflammatory markers, which have been found to be affected by ACEs and could impact suicidal ideation40,65, including C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, fibrinogen, E-selectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule; (3) psychological factors, including the Kessler K666, generalized anxiety disorder67, depressed affect67; and 4) two personality traits measured by the Big Five (neuroticism, conscientiousness) that are known determinants of suicidal ideation68–70.

Statistical analysis

Main analysis

Our main analysis includes three instrumental variables models: a two-stage limited information maximum likelihood (2SLIML) model, a bivariate probit model that is a recursive probit model71–73 and an IV probit model that is a control function35. All instrumental variables models must satisfy three criteria: instruments must be exogenous, strongly correlate with the endogenous variable of interest, and not correlate with the error term24.

Both instruments were theoretically exogenous: ACEs occurred in childhood, and daily discrimination occurred due to the actions of third parties. We evaluated whether or not the correlation between the endogenous variable of interests (flourishing) and instruments (ACEs and daily discrimination) is sufficiently strong using the Montiel-Olea-Pfluegar weak instrument test33. To avoid any potential correlations between the instruments and the error term, we included the known risk factors for suicidal ideation, including socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., marital status, household income), physical health (e.g., chronic pain, inflammation), psychological factors, and social relationships, which are listed in detail above6,47,74,75. We additionally evaluated whether the instruments were exogenous using an overidentification test and whether the flourishing parameter was significantly different after being corrected (endogeneity test). Figure 1 presents a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of the model76,77. All models are estimated using Stata 1633,78.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed three sets of sensitivity analyses. We used binary measures of flourishing that omitted emotional well-being (measures included eudaimonic aspects only). We used continuous versions of flourishing (z-scores) for both the eudaimonic-hedonic measure of flourishing and the eudaimonic-only measure of flourishing. Finally, we estimated every model substituting the z-score of suicidal ideation for the binary version. Thus, we estimated all combinations of measures of suicidal outcomes (binary, z-score) and measures of flourishing (binary eudaimonic-hedonic, binary eudaimonic only, continuous eudaimonic-hedonic, continuous eudaimonic only). Binary suicidal ideation-binary flourishing models were estimated using 2SLIML and bivariate probit; binary suicidal ideation-continuous flourishing models were estimated using 2SLIML and IV probit (control function probit); continuous suicidal ideation-binary flourishing models were estimated using 2SLIML, and continuous suicidal ideation-continuous flourishing models were estimated using 2SLIML.

Ethical approval

This study was not required to obtain ethics approval since it uses publicly available data that contains no identifiable private information and is therefore not considered human subjects research by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California. The authors did not have access to any personally identifiable information or information that would link the data to individuals’ identities. All data are reported in aggregate to eliminate the possibility of deductive identification of individuals.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Contributors’ Statement Page: X. and B. had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: All authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Data are public and were independently obtained by each author. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: B. Obtained funding: X. Administrative, technical, or material support: X.

Funding

This study was supported by grants CORONAVIRUSHUB-D-21-00125 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (PI Xiao) and NIHCM 226371-01 from National Institute for Health Care Management Research and Educational Foundation (PI Xiao).

Data availability

Data sharing: Data are accessible through Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). The public-use data files in this collection are available for access by the general public through https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/series/203. Access does not require affiliation with an ICPSR member institution. All Stata code is accessible from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-28568-2.

References

- 1.CDC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), Nonfatal Injury Data. WISQARSTM — Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting Systemhttps://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html (2022).

- 2.Xiao Y, Cerel J, Mann JJ. Temporal trends in suicidal ideation and attempts among US adolescents by sex and race/ethnicity, 1991–2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2113513–e2113513. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John Mann J, Michel Christina A, Auerbach Randy P. Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: A systematic review. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2021;178:611–624. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh CG, et al. Prospective validation of an electronic health record-based, real-time suicide risk model. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e211428. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czeisler MÉ, et al. Follow-up survey of US adult reports of mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic, September 2020. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2037665. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin JC, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2017;143:187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao Y, et al. Suicide prevention among college students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021;10:e26948. doi: 10.2196/26948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen J, et al. Strengths-based assessment for suicide prevention: Reasons for life as a protective factor from Yup’ik Alaska native youth suicide. Assessment. 2021;28:709–723. doi: 10.1177/1073191119875789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen J, Wexler L, Rasmus S. Protective factors as a unifying framework for strength-based intervention and culturally responsive American Indian and Alaska native suicide prevention. Prev. Sci. 2022;23:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vranceanu A-M, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a resiliency intervention for the prevention of chronic emotional distress among survivor-caregiver dyads admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e2020807. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill SV, Coyne-Beasley T. The use of protective caregiving to create positive racial-ethnic socialization and mitigate psychological outcomes of racial discrimination. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e212544. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.VanderWeele TJ, McNeely E, Koh HK. Reimagining health—Flourishing. JAMA. 2019;321:1667–1668. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.VanderWeele TJ. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:8148–8156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702996114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. Flourishing under fire: Resilience as a prototype of challenged thriving. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and The Life Well-lived 15–36 (American Psychological Association, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1037/10594-001.

- 15.Keyes CLM, Simoes EJ. To flourish or not: Positive mental health and all-cause mortality. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102:2164–2172. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002;43:207–222. doi: 10.2307/3090197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin J. Human flourishing: A new concept for preventive medicine. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021;61:761–764. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rey L, Mérida-López S, Sánchez-Álvarez N, Extremera N. When and how do emotional intelligence and flourishing protect against suicide risk in adolescent bullying victims? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2019;16:2114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16122114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mai Y, et al. Impulsiveness and suicide in male offenders: Examining the buffer roles of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and flourishing. Psychol. Psychother. 2021;94:289–306. doi: 10.1111/papt.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiba K, Kubzansky LD, Williams DR, VanderWeele TJ, Kim ES. Associations between purpose in life and mortality by SES. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021;61:e53–e61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim ES, Whillans AV, Lee MT, Chen Y, VanderWeele TJ. Volunteering and subsequent health and well-being in older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020;59:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dippel C, Ferrara A, Heblich S. Causal mediation analysis in instrumental-variables regressions. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata. 2020;20:613–626. doi: 10.1177/1536867X20953572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dippel, C., Gold, R., Heblich, S. & Pinto, R. Mediation Analysis in IV Settings With a Single Instrument. (2019).

- 24.Maciejewski ML, Brookhart MA. Using instrumental variables to address bias from unobserved confounders. JAMA. 2019;321:2124–2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanderWeele TJ. Can sophisticated study designs with regression analyses of observational data provide causal inferences? JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78:244–246. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlsson H, Kendler KS. Applying causal inference methods in psychiatric epidemiology: A review. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77:637. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:819–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang J, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, epigenetics and telomere length variation in childhood and beyond: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020;29:1329–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00787-019-01329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang S, Postovit L, Cattaneo A, Binder EB, Aitchison KJ. Epigenetic modifications in stress response genes associated with childhood trauma. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:808. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artigas R, Vega-Tapia F, Hamilton J, Krause BJ. Dynamic DNA methylation changes in early versus late adulthood suggest nondeterministic effects of childhood adversity: A meta-analysis. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2021;12:768–779. doi: 10.1017/S2040174420001075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thumfart KM, Jawaid A, Bright K, Flachsmann M, Mansuy IM. Epigenetics of childhood trauma: Long term sequelae and potential for treatment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pflueger CE, Wang S. A robust test for weak instruments in stata. Stata J. 2015;15:216–225. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1501500113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Measurement Error in Nonlinear Models: A Modern Perspective. (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006).

- 35.Wooldridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. MIT press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jargowsky PA. Omitted variable bias. Encycl. Soc. Meas. 2005;2:919–924. doi: 10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00127-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitaker RC, et al. Association of childhood family connection with flourishing in young adulthood among those with type 1 diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e200427. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson D, Sharif I, Fink A. The relative contributions of adverse childhood experiences and healthy environments to child flourishing in delaware. Del. J. Public Health. 2016;2:58–61. doi: 10.32481/djph.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitaker RC, Dearth-Wesley T, Herman AN. Childhood family connection and adult flourishing: associations across levels of childhood adversity. Acad. Pediatr. 2021;21:1380–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boylan JM, Cundiff JM, Fuller-Rowell TE, Ryff CD. Childhood socioeconomic status and inflammation: Psychological moderators among black and white Americans. Health Psychol. 2020;39:497. doi: 10.1037/hea0000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker J, et al. Screening for suicidality in cancer patients using Item 9 of the nine-item patient health questionnaire; does the item score predict who requires further assessment? Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2010;32:218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikrahan GR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a well-being intervention in cardiac patients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2019;61:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song J, et al. Who returns? Understanding varieties of longitudinal participation in MIDUS. J. Aging Health. 2021;33:896–907. doi: 10.1177/08982643211018552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldon KM, Corcoran M, Prentice M. Pursuing eudaimonic functioning versus pursuing hedonic well-being: The first goal succeeds in its aim, whereas the second does not. J. Happiness Stud. 2019;20:919–933. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9980-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopez-Gomez I, Chaves C, Hervas G, Vazquez C. Comparing the acceptability of a positive psychology intervention versus a cognitive behavioural therapy for clinical depression. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017;24:1029–1039. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olfson M, et al. Short-term suicide risk after psychiatric hospital discharge. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73:1119–1126. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung DT, et al. Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74:694–702. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bethell CD, Gombojav N, Whitaker RC. Family resilience and connection promote flourishing among US children even amid adversity. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2019;38:729–737. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB. A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19) Aging Ment. Health. 2003;7:186–194. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radler BT, Ryff CD. Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. J. Aging Health. 2010;22:307–331. doi: 10.1177/0898264309358617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. How Healthy are We? A National Study of Well-Being at Midlife. University of Chicago Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryff, C. D. et al. Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 2), 2004–2006: Version 7. (2007) 10.3886/ICPSR04652.V7.

- 53.Ryff, C. D., Seeman, T. & Weinstein, M. Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 2): Biomarker project, 2004–2009: Version 9. (2010) 10.3886/ICPSR29282.V9.

- 54.Ryff, C. D. et al. Midlife in the United States (MIDUS refresher), 2011–2014: Version 3. (2016) 10.3886/ICPSR36532.V3.

- 55.Weinstein, M., Ryff, C. D. & Seeman, T. E. Midlife in the United States (MIDUS refresher): Biomarker project, 2012–2016: Version 6. (2017) 10.3886/ICPSR36901.V6.

- 56.Love GD, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, Ryff CD. Bioindicators in the MIDUS national study: Protocol, measures, sample, and comparative context. J. Aging Health. 2010;22:1059–1080. doi: 10.1177/0898264310374355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yip T, et al. Linking discrimination and sleep with biomarker profiles: An investigation in the MIDUS study. Compr. Psychoneuroendocr. 2021;5:100021. doi: 10.1016/j.cpnec.2020.100021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson D, et al. Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1995;104:15–25. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malone TL, et al. Prediction of suicidal ideation risk in a prospective cohort study of medical interns. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0260620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tordoff DM, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5:e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim S, Lee H-K, Lee K. Which PHQ-9 items can effectively screen for suicide? Machine learning approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:3339. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goldstein E, Topitzes J, Miller-Cribbs J, Brown RL. Influence of race/ethnicity and income on the link between adverse childhood experiences and child flourishing. Pediatr. Res. 2021;89:1861–1869. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01188-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999;40:208–230. doi: 10.2307/2676349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hostinar CE, Lachman ME, Mroczek DK, Seeman TE, Miller GE. Additive contributions of childhood adversity and recent stressors to inflammation at midlife: Findings from the MIDUS study. Dev. Psychol. 2015;51:1630. doi: 10.1037/dev0000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kessler RC, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000;15:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cobb-Clark DA, Schurer S. The stability of big-five personality traits. Econ. Lett. 2012;115:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schultz DP, Schultz SE. Theories of Personality. Cengage Learning; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang L, et al. Associations between impulsivity, aggression, and suicide in Chinese college students. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:551. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shelton Brown H, Pagán JA, Bastida E. The impact of diabetes on employment: Genetic IVs in a bivariate probit: Impact of diabetes on employment. Health Econ. 2005;14:537–544. doi: 10.1002/hec.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chiburis RC, Das J, Lokshin M. A practical comparison of the bivariate probit and linear IV estimators. Econ. Lett. 2012;117:762–766. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2012.08.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Presley CJ, et al. Association of broad-based genomic sequencing with survival among patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the community oncology setting. JAMA. 2018;320:469–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.9824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiao Y, Lindsey MA. Adolescent social networks matter for suicidal trajectories: Disparities across race/ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, and socioeconomic status. Psychol. Med. 2021;52:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao Y, Brown TT. The effect of social network strain on suicidal ideation among middle-aged adults with adverse childhood experiences in the US: A twelve-year nationwide study. SSM Popul. Health. 2022;18:101120. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lipsky AM, Greenland S. Causal directed acyclic graphs. JAMA. 2022;327:1083–1084. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zander, B. van der, Textor, J. & Liskiewicz, M. Efficiently finding conditional instruments for causal inference. In: Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2015).

- 78.Baum CF, Schaffer ME, Stillman S. Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. Stata J. 2007;7:465–506. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0800700402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing: Data are accessible through Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). The public-use data files in this collection are available for access by the general public through https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/series/203. Access does not require affiliation with an ICPSR member institution. All Stata code is accessible from the corresponding author.