Abstract

Telephone genetic counseling (TGC) is accepted as standard clinical care for people seeking hereditary cancer risk assessment. TGC has been shown to be non-inferior to in-person genetic counseling, but trials have been conducted with a predominantly highly educated, non-Hispanic White population. This article describes the process of culturally adapting a TGC protocol and visual aid booklet for Spanish-preferring Latina breast cancer survivors at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. The adaptation process included two phases. Phase 1 involved a review of the literature and recommendations from an expert team including community partners. Phase 2 included interviews and a pilot with the target population (n = 14) to collect feedback about the adapted protocol and booklet following steps from the Learner Verification and Revision Framework. We describe the adaptation process and report the main adaptations following the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Interventions (FRAME). Adaptations in Phase 1 were responsive to the target population needs and characteristics (e.g., delivered in Spanish at an appropriate health literacy level, addressing knowledge gaps, targeting cultural values). Phase 2 interviews were crucial to refine details (e.g., selecting words) and to add components to address GCT barriers (e.g., saliva sample video). Cultural adaptations to evidence-based TGC protocols can increase the fit and quality of care for historically underserved populations. As TGC visits become routine in clinical care, it is crucial to consider the needs of diverse communities to adequately promote equity and justice in cancer care.

Keywords: Genetic counseling, Hereditary breast and ovarian cancers, Telehealth, Equity, Cultural adaptations

This article describes the process of adapting a telephone genetic counseling protocol and visual aid booklet for Spanish-preferring Latina breast cancer survivors at increased risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC). Culturally adapting interventions can improve health outcomes in historically marginalized populations and promote equity.

Implications.

Practice: Genetic counselors can consider using culturally appropriate information (e.g., using a flan metaphor to explain genetic mutations) with Hispanic Spanish-preferring patients.

Policy: Policymakers should adjust reimbursement policies for genetic counseling that is provided via phone or video.

Research: Future research should assess how accessible genetic counseling delivered by video would be relative to telephone only, especially with racially/ethnically diverse populations.

INTRODUCTION

There is currently a high demand for genetic counseling and testing (GCT) for hereditary conditions, including cancer. Genetic test results inform treatment decisions, risk reduction, and risk management strategies for patients diagnosed with cancer and their relatives [1, 2], which can substantially improve health outcomes and life expectancy [3]. Receiving genetic counseling prior to testing is both recommended and associated with positive psychosocial outcomes as well as satisfaction with testing decisions [4, 5]. Latinas at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers (HBOC) have comparable prevalence of pathogenic variants (PV) to other groups [6], but are less likely to be referred to and receive GCT than non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs) [7, 8]. Therefore, improving access to and use of GCT for Hispanic/Latinx populations is crucial to address disparities in cancer care.

Telephone genetic counseling (TGC) as a delivery strategy can address well-known barriers to GCT that Latinas face [9–11]. TGC can broaden access to the limited number of Spanish-speaking counselors in the United States [12], reduce transportation difficulties, allow more flexibility for scheduling appointments, and reduce high costs [9, 10, 13–16]. Prior studies have supported that TGC is not inferior to in-person genetic counseling (IPGC) in terms of knowledge, worry, decisional conflict, satisfaction, cancer-specific distress, and quality of life [17]. Overall, TGC has also been shown to be cost saving, more convenient [17–20], and is currently an accepted alternative to IPGC in clinical practice. Yet, limited data are available on the effectiveness of TGC among Hispanic/Latinx communities, and in particular those for whom Spanish is their preferred language. Most studies on TGC for cancer genetics have been conducted with predominantly highly-educated NHWs [17, 19, 21]. Evaluating TGC for Spanish-preferring patients at increased risk of hereditary cancers is warranted.

Implementing interventions that are responsive to the patient’s needs and align with their cultural values can increase both satisfaction and effectiveness [22, 23]. Meta-analytic evaluations show that culturally and linguistically targeted adaptations are more effective in improving health outcomes for marginalized populations compared to the standard of care [23]. Cultural adaptations entail systematic modifications to consider the target population’s language, culture, and overall context [24]. These adaptations have the overarching goal of improving reach, engagement, and sustainability [22, 25]. Evidence suggests that cultural adaptations improve the fit of an intervention to a specific group, making the content more relevant or relatable, and tapping into important shared values (e.g., family). For instance, transcreation, in contrast to translation, is the process of “infusing culturally relevant themes, images, and context into materials (...) to meet the health literacy and informational needs of the new target population while maintaining a theoretical and empirical basis” [26]. Transcreation provides a complimentary framework to adapt evidence-based interventions (EBIs) for minority populations with the goal of addressing disparities without compromising fidelity [23, 27].

Prior efforts to culturally adapt interventions and treatments for Hispanic/Latinx people have been reported to have high acceptability and success [26, 28–30]. However, there has been little consistency in the reporting of their processes and results. Systematically documenting and reporting the cultural adaptation process can help advance the emerging science of cultural adaptations [31]. Stirman and colleagues’ Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based interventions (FRAME) (2018) provides a complete framework to categorize adaptations to EBIs, that describes in detail the decision-making process, such that it easier to understand the effects of different kinds of modifications to the intervention outcomes [32]. In cancer genomics, only a few interventions have been targeted to Spanish-preferring Hispanic/Latinx patients with the goal of increasing knowledge or uptake of GCT [33–35]. Few studies have reported their adaptation process for educational materials about hereditary cancer risk for Spanish-preferring individuals [33, 36]. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports of prior studies that aimed to culturally adapt pre or post-test genetic counseling practices for Spanish-preferring patients, particularly with telephone-based modalities. This study describes the process of culturally adapting a TGC protocol and visual aid booklet developed by Schwartz et al. [17] for Spanish-preferring Latina breast cancer survivors at increased risk for HBOC.

METHODS

Original protocol

The procedures and results of Schwartz and colleagues’ non-inferiority trial have been previously reported [17, 37]. Briefly, women 21 to 85 years old with at least a 10% risk for a BRCA1/2 mutation were recruited from four university hospitals. Participants (n = 669) were randomly assigned to receive pretest genetic counseling and result disclosure either in person at one of the clinics (usual care) or by telephone. Genetic counselors in both arms used a standardized visual aids booklet during the session to communicate different concepts and risks to patients.

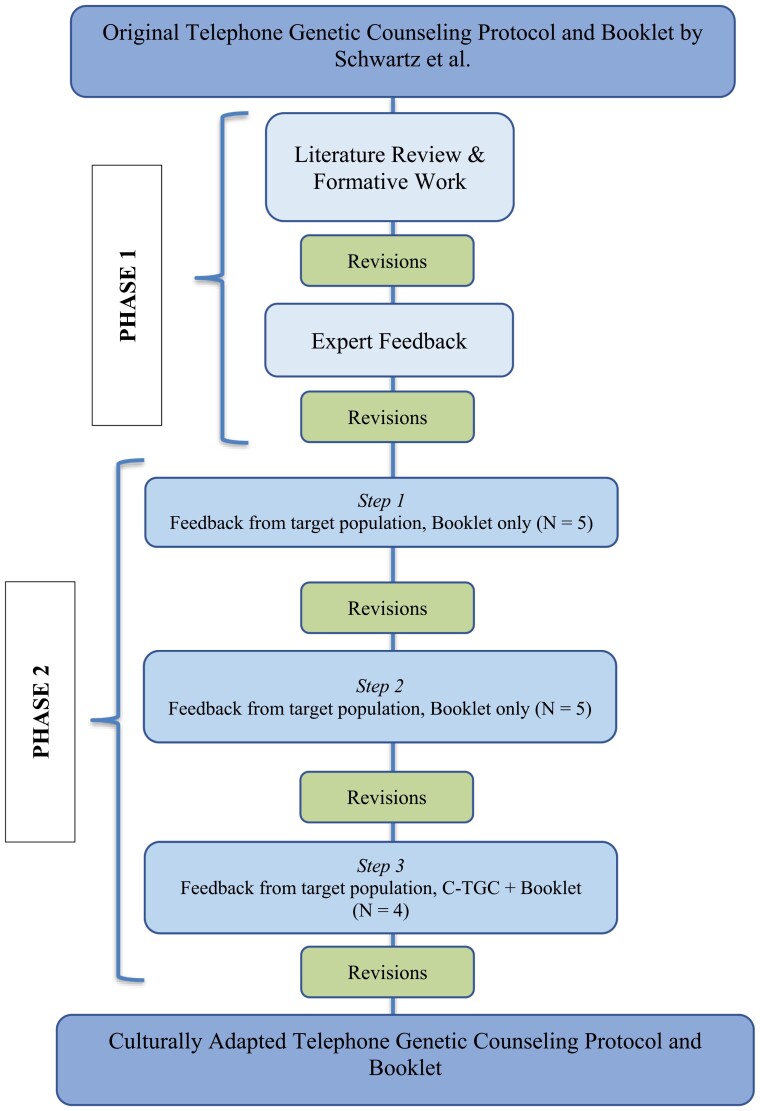

Following consensus guidelines [38], the adaptation process of the protocol and visual aid booklet followed two phases (see Fig. 1): literature review and pilot phase.

Fig 1.

Steps of the adaptation process.

Phase 1—Literature review and expert feedback

Phase 1 was informed by a review of the literature, prior formative work, and expert feedback. The review of the literature included information about Latina breast cancer survivors’ experiences with genetic counseling and testing, and evidence-based risk communication. Based on the literature review and our prior formative work [10, 11], the lead investigator (PI) and Research Assistant (RA) conducted an initial adaptation of the TGC protocol and booklet.

A team of 10 experts, including genetic counselors, linguists, community partners, and experts in translational genomics acted as consultants and met to review the protocol and booklet for style, content, and validity. Two patient navigators, one genetic counselor, the PI, and the RA were bilingual in English and Spanish. Two members of the expert team were the lead investigators of the original study.

Feedback was obtained from all experts during in-person meetings, in which the RA took detailed notes regarding suggested adaptations. Further, experts could share annotated documents via email with the RA. A round of revisions to the materials was conducted with the collected feedback after each meeting. There was a total of ten rounds of adaptations conducted over approximately seven months. Throughout Phase 1, despite the multiple cultural adaptations conducted (e.g., adding culturally-relevant images) all materials remained in English so that the monolingual English-speakers in the expert panel could understand the content. The resulting version of the TGC protocol and booklet was then translated into Spanish and reviewed by multiple native Spanish-speakers from different countries of origin to ensure cross-national validity.

Phase 2—Pilot feedback from target population

Participants

We recruited through a community organization that serves Latinas with breast cancer. Potential participants were screened for eligibility by the RA. They were eligible if they self-identified as Latina, female, were 18 years old or older, native Spanish speakers, had been diagnosed with breast cancer, had completed treatment other than hormone therapy, and met National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 2018 criteria for genetic cancer risk assessment for HBOC due to their personal or family history of cancer. Women who had already received genetic counseling were excluded. Eligible women interested in participating, scheduled an in-person interview at a convenient location (e.g., church, community organization).

Procedures

Phase 2 adaptations were guided by the three steps of the Learner Verification and Revision Framework [39]. Step 1: semi-structured interviews were conducted with five participants to gather feedback about the visual aid booklet specifically. During the interview, the interviewer showed participants the booklet page by page and asked participants open-ended questions about their thoughts on the format, their understanding, emotions elicited by the information and images, cultural acceptability, and suggestions for improvement (e.g., what do you understand from this graph?). We specifically asked participants about their use of certain words or phrases that bilingual team members were not sure how to translate (e.g, risk factors, screening, red flags, genetic mutation, genetic counseling). After these initial five interviews, adaptations based on participant feedback were made prior to the subsequent round. Step 2: semi-structured interviews were conducted with five new participants using the same protocol and interview guide as before. Again, changes were made to the booklet prior to the subsequent round. Step 3: four women who had not participated in the previous rounds of interviews completed the entire culturally adapted telephone genetic counseling (C-TGC) protocol with the booklet. After completing C-TGC, the four women participated in semi-structured interviews. Interviews in Step 3 included the same questions from the previous interview guide regarding the usability and acceptability of the booklet and their experiences with the process of receiving C-TGC (e.g., Was the language and information used during the genetic counseling session culturally appropriate? How was the process of getting tested; did you have any challenges?). The C-TGC and booklet were refined one last time according to the feedback received (Fig. 1).

All interviews for Phase 2 were completed in 2018 and 2019. Interviews were conducted by the PI or RA in Spanish and in private rooms. They lasted approximately one hour and were audio-recorded with participants’ permission. Participants responded to a short survey that assessed sociodemographic and clinical information. All participants gave their informed consent to participate. The first ten participants provided verbal consent only, while the last four provided written consent, including the appropriate HIPAA components, to receive C-TGC, evaluate the adapted protocol, and give us feedback for improvement. Study procedures were approved by Georgetown University Institutional Review Board Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

Phase 1: We reviewed meeting notes and used rapid integration of the feedback into the adaptation of the materials. Phase 2: Sociodemographic and clinical factors were summarized using descriptive statistics (IBM Statistics SPSS 25). Semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim in Spanish and de-identified. The qualitative analysis of the interviews was conducted in Spanish by bilingual RAs using Dedoose Qualitative Software [40]. We followed a deductive approach to develop the codebook, centering around explicit feedback and suggested adaptations for the C-TGC and visual aid booklet. Selected codes included aspects liked, aspects disliked, length, understanding of information, and suggestions about the format, language, and illustrations and graphs for the booklet specifically. All interviews were coded by two independent coders, who then met to reconcile each coded interview until they reached consensus. We used the same protocol to analyze all fourteen interviews from the Learner Verification process.

Finally, results were further categorized following the FRAME categories [32], which indicate each of the changes made (i.e., what was retained, removed, added, or modified), the stage at which it as conducted, whether it was planned or unplanned, the decision-makers, its fidelity to the original protocol, and the ultimate goal. FRAME differentiates between contextual and content modifications. Contextual modifications are “changes made to...the format, channel, setting or location in which the overall intervention is delivered” [41]. This may include the personnel who deliver the intervention or the population for which it is targeted [32]. In contrast, content modifications refer to “changes to the intervention procedures, materials, or delivery” [41].

There were 12 iterations of adaptations to the C-TGC and booklet throughout the entire process. The version resulting from each iteration was saved in a secure shared folder with the study team indicating the version number and date.

RESULTS

Key findings from every step of the adaptation process are detailed below. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of Latina breast cancer survivors (n = 14) who participated in the pilot phase of the adaptation process.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical factors of participants in Phase 2

| n = 14 | M(SD)/n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | |

| Age at time of interview | 47.86 (5.67) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 14 (100%) |

| Self-identified race | |

| White | 3 (21.43%) |

| More than one race | 3 (21.43%) |

| Unsure/not reported | 8 (57.14%) |

| Country of birth | |

| Argentina | 1 (7.14%) |

| Bolivia | 1 (7.14%) |

| Colombia | 3 (21.43%) |

| El Salvador | 3 (21.43%) |

| Honduras | 3 (21.43%) |

| Mexico | 1 (7.14%) |

| Panama | 1 (7.14%) |

| Puerto Rico | 1 (7.14%) |

| Years living in the United States | 18.36 (7.16) |

| Highest education level completed | |

| Primary school (0–8 years) | 1 (7.14%) |

| Secondary school (9–12 years) | 4 (28.57%) |

| 2 years of technical school | 2 (14.28%) |

| Some university or college | 4 (28.57%) |

| Graduate degree | 3 (21.42%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single or never married | 7 (50%) |

| Married or living with partner | 5 (35.71%) |

| Divorced | 1 (7.14%) |

| Widowed | 1 (7.14%) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 4 (28.57%) |

| Part-time | 2 (14.28%) |

| Full-time homemaker or family caregiver | 1 (7.14%) |

| Retired | 1 (7.14%) |

| Unemployed, seeking employment | 1 (7.14%) |

| Medical leave | 1 (7.14%) |

| Not reported | 4 (28.57%) |

| Clinical factors | |

| Breast cancer diagnosis, yes | 14 (100%) |

| Age at diagnosis | 41.64 (4.81) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| Stage 0 | 2 (14.28%) |

| Stage 1 | 4 (28.57%) |

| Stage 2 | 2 (14.28%) |

| Stage 3 | 5 (37.71%) |

| Prior genetic testing for HBOC | 8 (57.14%) |

Findings from Phase 1—Literature review and expert feedback

Evidence-based risk communication strategies included recommendations to use visual aids in the form of pictographs, natural frequencies rather than percentages, and interpretive labels to convey meaning [42]. Further, work from Joseph et al. [43] has shown a mismatch between what counselors discuss (i.e., too much biomedical information) and the patient’s information needs. Our own formative work interviewing both genetic counselors and Latina women at risk for HBOC (see [10, 11]) revealed key barriers and facilitators that Latinas face when accessing GCT, misconceptions, and cultural values that influence decision-making. For example, we found that participants often confuse cervical and uterine cancer with ovarian cancer and that informing the risk of family members (e.g., siblings and children) was a key motivator for receiving genetic counseling or testing. Other previous work reported finding feelings of guilt in Latina women about passing on a genetic mutation to their children (e.g., if they had a positive result) [44].

During the expert panel revisions, community partners noted a trend in which many Latina breast cancer survivors who had been diagnosed with breast cancer years before had received genetic testing without genetic counseling. Genetic counselors and experts in translational genomics added that women who had received genetic testing for hereditary cancer risk ten years ago or longer would have likely only received BRCA1/2 testing and were therefore eligible for broader multigene panel testing at the time of the study. Experts also recommended reducing the amount of technical medical information from both the TGC protocol and booklet, using bullet points rather than paragraphs, and discussing challenges with family communication and implications for family members more in-depth. Modifications Informed by Phase 1. The C-TGC protocol and booklet were planned to be delivered in Spanish by a Spanish-speaking certified genetic counselor. We modified the eligibility criteria to include women who had previously received genetic testing for HBOC without counseling. C-TGC appointments were made available on evenings and weekends. The content of the booklet was simplified to improve understanding for those with lower health literacy. We significantly reduced the text while increasing images, graphs, and tables. We worked closely with an independent, bilingual, Latinx illustrator to create and integrate culturally representative images (Table 2). Specifically, we created a main character that appeared throughout the booklet and changed the pedigree to a family tree depicting diverse relatives. The C-TGC protocol and booklet emphasized the benefits that genetic counseling and testing could have for both the patient and their family through both text and images.

Table 2.

Visual examples of modifications to the booklet

| Original | Adapted |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Following advice from the expert panels, we removed information about chromosomes, autosomal dominant inheritance, and cumulative risk. Instead of providing detail on autosomal dominant inheritance, the C-TGC protocol directed the genetic counselor to explain genes and patterns of inheritance verbally and in plain-language. As the booklet was used as a guide for the counseling session, the genetic counselor could refer to an image of a coin being tossed to explain the 50% chance of inheriting a genetic mutation and emphasize that people have no control over which genes they pass on to their children. This last point was added intentionally to the protocol to address potential guilt. A particularly culturally relevant example used during the C-TGC and reinforced with an image in the booklet was a metaphor used by the counselor in which they use a flan recipe to explain that some genetic alterations are harmless (e.g., adding more sugar to the flan) and others may change the instructions completely (e.g., using salt instead of sugar).

Information regarding the pros and cons of genetic testing and the potential test results was retained but presented in a simplified format to enhance the fit for the target population. Lastly, we added an “additional resources” booklet in recognition that Latinas have more barriers to access information about HBOC in Spanish and that they may want to share it with family members.

For the C-TGC process, we divided the pre-test genetic counseling session in two separate phone calls. An RA collected the family history and shared the final pedigree with the genetic counselor before the first counseling session. This change was intended to decrease the duration of the first genetic counseling session given how extensive Hispanic/Latinx families can be [45]. Collecting the family history prior to counseling also gave patients more time to gather additional information if needed. The counselor was encouraged to pause, repeat, reiterate, simplify, rephrase, and slow down as much as possible.

Findings from Phase 2—Steps 1 and 2

Most participants mentioned that booklets were easy to understand for people with little to no formal education. Participants consistently said that what they liked most about the booklets was how instructive they were and the easy explanations. One participant highlighted, “Yes, (the booklet) is very clear, quite easy to understand.” (104). All participants agreed that the length was ideal to keep them engaged, often describing it as short and concise and that it contained an adequate amount of information. Participants appreciated the use of a flan recipe metaphor to explain the concept of mutation. For instance, one participant said, “Yes (the recipe example) is important because sometimes there are people that are more—I mean, they understand things better through examples, or are more visual.” (101) Participants appreciated the example of flipping a coin to highlight that hereditary cancer was by chance and reported feeling like the illustrations represented the Latinx community. One participant said: “I identified with the girl…. Yeah, looking at them (the images), the families reminded me of my mom and dad” (105).

Suggested changes from these interviews, focused on the booklet, included using the same time frame in the pictographs for cancer risk (i.e., risk up until 70 years old), using female figure sticks and cancer ribbons in the pictograms, and adding a short blurb of information with the bottom-line message to reinforce the meaning of the graph (e.g., “A genetic alteration in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene results in a high risk of developing a second cancer”). Participants could understand the graphs better when they had a short-written explanation with their bottom-line meaning.

Participants agreed that the phrase genetic alteration was clearer compared to genetic mutation (could sound like mutilation) and genetic change (could convey that test results could change due to their behaviors). Lastly, participants preferred the translation of genetic counseling to be asesoría genética rather than consejería genética given that counseling (“consejería”) could be understood as psychological counseling.

Modification informed by phase 2—steps 1 and 2

All of the changes suggested by participants were integrated into the booklets. The only change that was later retracted was adding cancer ribbons into the pictographs, as the images ended up being too busy and distracting rather than informative. We added to the C-TGC protocol that the counselor give a verbal explanation while referring to the graphs. Additionally, natural frequencies were written in numbers next to pictographs.

To address the needs of previously tested vs. untested participants, we created separate visual aid materials with information targeted to women who had not received genetic testing vs. those who had their prior results available. The booklets differed in the order the information was presented. An explanation of genetic test results was inserted before going into a discussion of risk. Both booklets included a section on family communication.

Findings from Phase 2—step 3

Participants (n = 4) reported that completing the C-TGC was comfortable and convenient. While most expressed a preference for receiving counseling in person, they also recognized that transportation was an important barrier for many patients, especially those in active treatment who may not always feel well enough to travel. Additionally, when participants became aware of the shortage of Spanish-speaking GC in the USA, they reported a preference for receiving counseling in Spanish by phone rather than English in person. Participants reported that the booklet helped them understand the information presented to them during the counseling session better. One participant said, “So the booklet also helped me understand (ubicarme) in what she was asking me, or the page, or whatever it was, it was very well guided.” (302). One participant reported reading the booklet before the appointment and another one reported sharing it with her relatives. One participant who had received genetic testing prior to the study was grateful for the possibility of receiving counseling. In her words,

I knew that I had received genetic testing—I did receive it. Ok? But, specifically, the doctor only told me “OK, your problem is not genetic. But then, when I received the information with you (...) I learned a lot of things because, like, when I had the interview with the—with the doctor, she was explaining to me, step by step, with the booklet and all. I was learning more about the risks that contribute little by little. I mean, the steps that are involved when the problem is genetic. So that helped me a lot too.” (301)

Some participants continued to have trouble understanding numbers and medical words on their own, but these were resolved once the counselor explained. One participant had remaining questions that she forgot to ask during the counseling session and one participant, who completed GT through the study, reported having some difficulty with the process.

“After the kit arrived, it took me maybe a week because (…) I feel quite insecure about not knowing things well, and I was waiting that my niece—my niece is very smart —and I was waiting that she would have a day off to go to her house and do it together with her. She was the one who helped me, and I don’t even know how—I would like to be like her, I don’t know how she does it. Look, she told me read bun bun bun, yes. She - She took off the---, and then, “are you sure you take that off?” “yes tía, yes, don’t worry” and that’s it. And she did the saliva thing to me.” (304)

Modifications informed by phase 2—step 3

We filmed a video in Spanish explaining how to collect the saliva sample. The video featured a Latina community partner giving verbal instructions and showing the saliva kit components.

Final C-TGC and visual aid booklet

Booklet

The final booklet was 14 pages long, double-sided, and 11 × 4.25″ in size. It included a description of genetic counseling and testing, hereditary cancer, genes, genetic alterations and the risk of cancer, the potential results of genetic tests and their implications, including a short guide on management options for individuals with a positive result. It also included tips on informed decision-making, family communication, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). The additional resources booklet included a glossary, frequently asked questions (e.g., cost), and clarification of common misconceptions (e.g., ovarian vs. cervical cancer).

C-TGC

The C-TGC consisted of a ~15 min call to collect family history, a 50–60 min call for the first genetic counseling session, and, if appropriate, a final 15 min call to disclose the genetic test results. C-TGC was provided in Spanish by a bilingual licensed genetic counselor. The visual aid booklets were sent ahead of the scheduled TGC appointment to be used as a guide in conjunction with the discussion with the genetic counselor. The counselor followed a protocol with probes to refer to the visual materials during the discussion (e.g., “as you can see in page X…”). After the first counseling session, women were offered free/low-cost multigene panel testing and were mailed a self-collection saliva sample kit if interested. The process of genetic testing was explained again by the RA over the phone and the video with instructions on how to collect the saliva sample was shared as a link by text message. Women who completed genetic testing were mailed a physical copy of the genetic counseling notes and test results in both English and Spanish. A full list of the final adaptations is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cultural adaptations conducted, classified according to the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications- Expanded (FRAME)

| Key changes | FRAME elements | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORIGINAL | ADAPTATION | WHAT | WHEN | WHO | Planned/unplanned | Fidelity | Reasons/goals |

| Recruitment from University hospital | Recruitment from community-based organizations | Context: Setting | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | Location/Accessibility, Access to resources | |

| Sample was mostly NHWs, high education, high SES | Target population was Spanish speaking Latinas, lower education, low SES | Context: Population | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | Consistent | Increase reach |

| English-speaking genetic counselor | Spanish-speaking genetic counselor with cultural competence | Context: Personnel | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | ||

| Only include patients who had never received GC or GT | Include women who had previously received GT without GC | Context: Population | Per-Implementation (Phase 2) | Research team, Community members, Recipients | Unplanned, proactive based on what we found at the onset of recruitment | Unknown | Improve fit to change in clinical practice and effectiveness/outcomes |

| Delivery in English only | Delivery in Spanish only | Context: Population | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | Consistent | Improve fit, Recipient: Spoken languages |

| Targeted drawings representing the content included in the booklet | Content: Adding elements | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team, Community members | Planned, proactive and reactive | Consistent | Address cultural factors, Recipient: Literacy and education level, and Cultural or religious norms | |

| Content targets common misconceptions | Content: Adding elements | Pre-Implementation (Phase 2) | Research team | Planned, proactive based on prior formative work | Improve effectiveness, Recipient: Literacy and education level | ||

| Blood Sample | Saliva sample | Context: Format | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | Consistent | Recipient: Access to resources |

| Video instructions for saliva collection | Content: Adding elements | Maintenance/Sustainment | Recipients | Unplanned, proactive based on results from Phase 2 | Recipient: Literacy and education level, Access to resources | ||

| Booklet with additional information (e.g., glossary) | Content: Adding elements | Pre-Implementation (Phase 2) | Community members, Recipients | Unplanned, proactive based on results from Phase 2 | |||

| Included high-level information (e.g., chromosomes, autosomal dominant inheritance) | The booklet and counseling session did not include technical information | Content: Removing elements | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | Unknown | Recipient: Literacy and education level |

| Family history collected at pre-test counselling session | Family history collected prior to pre-test counselling session | Content: Spreading | Pre-implementation (Phase 1) | Research team | Planned, proactive | Organization and Setting: Time constraints |

|

DISCUSSION

This paper described the process of culturally adapting an evidence-based TGC protocol for Spanish-speaking Latinas at risk of HBOC. TGC has previously been shown to be non-inferior to IPGC [17], but earlier studies have included low representation from Hispanic/Latinx people [20]. To our knowledge, this is the first TGC intervention culturally adapted for Latinas, a historically underrepresented population in genetics and genomics research.

TGC can address the unique barriers that at-risk Latinas face to hereditary cancer risk assessment, including facilitating access to Spanish-speaking counselors, eliminating the need for transportation, and providing more flexible schedules. However, it is essential to fully consider the needs of the Hispanic/Latinx community and implement policies that promote equity and justice in cancer care [46]. Meta-analytic reviews have shown that culturally adapted treatments are more relevant to the target population and are efficacious for ethnic minorities [23].

In addition to describing the methodology used to inform cultural adaptations, we report the main final adaptations with FRAME [32], FRAME offers a common language to discuss and systematically capture cultural adaptations, allowing a better understanding of the effects that different adaptations have on the intended outcomes [32]. Most adaptations in the C-TGC protocol and booklet were planned, informed by the literature review and expert panel, and decided by the multidisciplinary team. All initial adaptations conducted during Phase 1 were designed to be directly responsive the target population needs and characteristics (e.g., delivered in Spanish at an appropriate health literacy level). On the other hand, the learner verification process and pilot with the target population, Phase 2, was crucial to refine details (e.g., colors, selecting words) and obtain important insight that we had overlooked (e.g., adding how to collect a saliva sample video). Importantly, evidence shows lower uptake of genetic testing in TGC vs. IPGC, especially for minority women [47–49]. The reasons for this discrepancy are not fully known; thus, it would be important to explore the impact of adding a culturally-targeted video with instructions on how to collect saliva samples at home on uptake of GT.

Specific cultural adaptations described here can be readily applied to clinical practice. For instance, participants really enjoyed and appreciated having a culturally targeted booklet with visual aids. TGC sessions should include visual materials that represent diverse communities, are accessible, and written at an appropriate literacy level. Genetic counselors can use strategies to make the content of the counseling session more relevant for Latina patients, such as using culturally-relevant examples (e.g., flan recipe). Latina women have large families and prior research shows a lack of communication within the family regarding cancer history [11]. In our C-TGC protocol, an RA collected the family history prior to the counseling session. This may not be possible in clinical practice due to workforce capacity. Instead, Latina patients could be encouraged in advance of the pre-test counseling session to ask their relatives more information about their cancer history, including types of cancer and age of diagnosis. Further, a recent study evaluating TGC vs IPGC found that numeracy moderated the relationship between mode of counseling and knowledge post counseling [50]. Risk communication strategies used in our culturally-adapted protocol may be useful for different populations with low numeracy (e.g., using pictograms to depict risk in addition to natural frequencies and a sentence with the bottom-line meaning).

Other adaptations conducted for the C-TGC can inform policy improvements to the standard of care. Given that many patients are increasingly offered genetic testing by non-genetics professionals, possibly without comprehensive pre-test genetic counseling [51, 52], the visuals used in our booklet could be supplemented with brief text as a stand-alone educational resource for patients in this context. Additionally, due to the accommodations during the Covid-19 pandemic, cancer genetic counseling is currently being offered with a video component. We received feedback that some Latinas may prefer video vs. telephone visits. Future studies should assess how accessible video visits would be relative to TGC only, given the option for either/or, and adjust policies accordingly (e.g., reimbursement) [53].

Our study followed a rigorous research methodology consistent with established cultural adaptation process recommendations [29, 38]. Namely, taking a step-wise approach informed by (i) the context and existing literature, (ii) expert evaluations, (iii) feedback from the target population, and (iv) testing [29]. Nevertheless, this study had some limitations. We recruited a small convenience sample of Latina immigrants from an urban area in the Washington, DC region. Additional adaptations may be relevant for other Latina populations (e.g., living in rural areas, second generation). Moreover, Latinas are not a monolithic group. Our study included participants from limited countries of origin, so there may be differences with other groups.

Culturally adapting interventions can improve health outcomes in historically marginalized populations and promote equity. Implementing the cultural adaptations described here may increase the weight of TGC benefits compared to the known challenges, enhance the fit for Hispanic/Latinx populations and improve their quality of care. Future research will evaluate in a randomized controlled trial the effectiveness of C-TGC vs. enhanced usual care for Latinas at risk of HBOC.

Contributor Information

Sara Gómez-Trillos, Department of Oncology, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA; Jess and Mildred Fisher Center for Hereditary Cancer and Clinical Cancer Genomics, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA.

Kristi D Graves, Department of Oncology, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA; Jess and Mildred Fisher Center for Hereditary Cancer and Clinical Cancer Genomics, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA.

Katie Fiallos, Kimmel Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Marc D Schwartz, Department of Oncology, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA; Jess and Mildred Fisher Center for Hereditary Cancer and Clinical Cancer Genomics, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA.

Beth N Peshkin, Department of Oncology, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA; Jess and Mildred Fisher Center for Hereditary Cancer and Clinical Cancer Genomics, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA.

Heidi Hamilton, Department of Linguistics, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA.

Vanessa B Sheppard, Department of Health Behavior and Policy, Virginia Commonwealth University, VA, USA.

Susan T Vadaparampil, Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA.

Claudia Campos, Nueva Vida, Inc., Alexandria, VA, USA.

Ana Paula Cupertino, School of Medicine and Dentistry, Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA.

Maria C Alzamora, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, MedStar Washington Hospital Center/Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA.

Filipa Lynce, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Alejandra Hurtado-de-Mendoza, Department of Oncology, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA; Jess and Mildred Fisher Center for Hereditary Cancer and Clinical Cancer Genomics, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington DC, USA.

Funding

This project was funded by Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (GHUCCTS) by Federal Funds; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS); and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA) (KL2TR001432; Hurtado-de-Mendoza. PI).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest to report.

Human Rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All study procedures were approved by the Georgetown University Medical Center Institutional Review Board prior to 2018.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency statements: The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03959267. The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered. De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive. De-identified data from this study can be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) at the discretion of the principal investigator. If interested, please email the corresponding author. There is not analytic code associated with this study. Materials used to conduct the study are not publicly available. If interested, please email the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Weitzel JN, McCaffrey SM, Nedelcu R, MacDonald DJ, Blazer KR, Cullinane CA.. Effect of genetic cancer risk assessment on surgical decisions at breast cancer diagnosis. Arch Surg. 2003; 138(12):1323–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz MD, Isaacs C, Graves KD, et al. Long-term outcomes of BRCA1/BRCA2 testing: risk reduction and surveillance. Cancer. 2012; 118(2):510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salhab M, Bismohun S, Mokbel K.. Risk-reducing strategies for women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations with a focus on prophylactic surgery. BMC Womens Health. 2010; 10(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meiser B, Halliday JL.. What is the impact of genetic counselling in women at increased risk of developing hereditary breast cancer? A meta-analytic review. Soc Sci Med. 2002; 54(10):1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark S, Bluman LG, Borstelmann N, et al. Patient motivation, satisfaction, and coping in genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Genet Couns. 2000; 9(3):219–235. doi: 10.1023/A:1009463905057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weitzel JN, Clague J, Martir-Negron A, et al. Prevalence and type of BRCA mutations in Hispanics undergoing genetic cancer risk assessment in the southwestern United States: a report from the Clinical Cancer Genetics Community Research Network. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31(2):210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cragun D, Weidner A, Kechik J, Pal T.. Genetic testing across young hispanic and non-hispanic white breast cancer survivors: facilitators, barriers, and awareness of the genetic information nondiscrimination act. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2019; 23(2):75–83. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2018.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dean M, Boland J, Yeager M, et al. Addressing health disparities in Hispanic breast cancer: accurate and inexpensive sequencing of BRCA1 and BRCA2. GigaScience. 2015; 4(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sussner KM, Jandorf L, Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB.. Barriers and facilitators to BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in New York City. Psycho-Oncology. 2013; 22(7):1594–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gómez-Trillos S, Sheppard VB, Graves KD, et al. Latinas’ knowledge of and experiences with genetic cancer risk assessment: barriers and facilitators. J Genet Couns. 2020; 29(4):505–517. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Graves K, Gómez-Trillos S, et al. Provider’s perceptions of barriers and facilitators for latinas to participate in genetic cancer risk assessment for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Healthcare. 2018; 6(3):116. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6030116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Augusto B, Kasting ML, Couch FJ, Lindor NM, Vadaparampil ST.. Current approaches to cancer genetic counseling services for Spanish-speaking patients. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019; 21(2):434–437. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sussner KM, et al. BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in New York city: new beliefs shape new generation. J Genet Couns. 2015; 24(1):134–148. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9746-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vadaparampil ST, Wideroff L, Breen N, Trapido E.. The impact of acculturation on awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk among Hispanics in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2006; 15(4):618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cruz-Correa M, Pérez-Mayoral J, Dutil J, et al. Clinical cancer genetics disparities among Latinos. J Genet Couns. 2017; 26(3):379–386. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-0051-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glenn BA, Chawla N, Bastani R.. Barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer risk among ethnic minority women: an exploratory study. Ethn Dis. 2012; 22(3):267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized non-inferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32(7):618–626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gordon ES, Babu D, Laney DA.. The future is now: technology’s impact on the practice of genetic counseling. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2018; 178(1):15–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buchanan AH, Datta SK, Skinner CS, et al. Randomized trial of telegenetics vs. in-person cancer genetic counseling: cost, patient satisfaction and attendance. J Genet Couns. 2015; 24(6):961–970. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Danylchuk NR, Cook L, Shane-Carson KP, et al. Telehealth for genetic counseling: a systematic evidence review. J Genet Couns. 2021; 30(5):1361–1378. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zilliacus EM, Meiser B, Lobb EA, et al. Are videoconferenced consultations as effective as face-to-face consultations for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic counseling? Genet Med. 2011; 13(11):933–941. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barrera M, Berkel C, Castro FG.. Directions for the advancement of culturally adapted preventive interventions: local adaptations, engagement, and sustainability. Prev Sci. 2017; 18(6):640–648. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chu J, Leino A.. Advancement in the maturing science of cultural adaptations of evidence-based interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017; 85(1):45–57. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM.. Cultural adaptation of treatments: a resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2009; 40(4):361. doi: 10.1037/a0016401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cabassa LJ, Baumann AA.. A two-way street: bridging implementation science and cultural adaptations of mental health treatments. Implement Sci. 2013; 8(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Piñeiro B, Díaz DR, Monsalve LM, et al. SYSTEMATIC transcreation of self-help smoking cessation materials for Hispanic/Latino smokers: improving cultural relevance and acceptability. J Health Commun. 2018; 23(4):350–359. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1448487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nápoles AM, Stewart AL.. Transcreation: an implementation science framework for community-engaged behavioral interventions to reduce health disparities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018; 18(1):710. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3521-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rivera YM, Vélez H, Canales J, et al. When a common language is not enough: transcreating cancer 101 for communities in Puerto Rico. J Cancer Educ. 2016; 31(4):776–783. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0912-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Domenech Rodríguez MM, Baumann AA, Schwartz AL.. Cultural adaptation of an evidence based intervention: from theory to practice in a latino/a community context. Am J Community Psychol. 2011; 47(1):170–186. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valle CG, Padilla N, Gellin M, et al.¿Ahora qué?: cultural adaptation of a cancer survivorship intervention for Latino/a cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2019; 28(9):1854–1861. doi: 10.1002/pon.5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chambers DA, Norton WE.. The adaptome: advancing the science of intervention adaptation. Am J Prev Med. 2016; 51(4, Supplement 2,):S124–S131. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stirman SW, Baumann AA, Miller CJ.. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019; 14(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Reyna VF, Wolfe CR, et al. Adapting a theoretically-based intervention for underserved clinical populations at increased risk for hereditary cancer: lessons learned from the BRCA-Gist experience. Prev Med Rep. 2022; 28:101887. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Graves KD, Gómez-Trillos S, et al. Developing a culturally targeted video to enhance the use of genetic counseling in Latina women at increased risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Community Genet. 2020; 11(1):85–99. doi: 10.1007/s12687-019-00423-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Conley CC, Castro-Figueroa EM, Moreno L, et al. A pilot randomized trial of an educational intervention to increase genetic counseling and genetic testing among Latina breast cancer survivors. J Genet Couns. 2021; 30(2):394–405. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rodríguez VM, Robers E, Zielaskowski K, et al. Translation and adaptation of skin cancer genomic risk education materials for implementation in primary care. J Comm Genet. 2017; 8(1):53–63. doi: 10.1007/s12687-016-0287-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peshkin BN, Kelly S, Nusbaum RH, et al. Patient perceptions of telephone vs. in-person BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic counseling. J Genet Couns. 2016; 25(3):472–482. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9897-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barrera M Jr, Castro FG, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ.. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012; 81(2):196. doi: 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chavarria EA, Christy SM, Simmons VN, Vadaparampil ST, Gwede CK, Meade CD.. Learner verification: a methodology to create suitable education materials. Health Lit Res Pract. 2021; 5(1):e49–e59. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20210201-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dedoose Version 9.0.17, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (2021). Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.https://www.dedoose.com/. Accessibility verified February 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A.. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2013; 8(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fischhoff B. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence Based User’s Guide. Washington DC: Government Printing Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Joseph G, Pasick R, Schillinger D, Luce J, Guerra C, Cheng J.. Information mismatch: cancer risk counseling with diverse underserved patients. J Genet Counsel. 2017; 26(5):1090–1104. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nycum G, Avard D, Knoppers BM.. Factors influencing intrafamilial communication of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic information. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009; 17(7):872–880. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Bradatan C.. Hispanic Families in the United States: Family Structure and Process in an Era of Family Change. National Academies Press (US); 2006. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19902/. Accessibility verified January 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kronenfeld JP, Graves KD, Penedo FJ, Yanez B.. Overcoming disparities in cancer: a need for meaningful reform for Hispanic and Latino cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2021; 26(6):443–452. doi: 10.1002/onco.13729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, et al. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: a cluster randomized trial. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2014; 106(12):dju328. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Crawford K, Koelliker E, Proussaloglou E, et al. The impact of converting to telehealth for cancer genetic counseling and testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. JCO. 2021; 39(15_suppl):e13612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.e13612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Butrick M, Kelly S, Peshkin BN, et al. Disparities in uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a randomized trial of telephone counseling. Genet Med. 2015; 17(6):467–475. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Binion S, Sorgen LJ, Peshkin BN, et al. Telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary cancer risk: patient predictors of differential outcomes. J Telemed Telecare. 2021; 1357633X211052220. doi: 10.1177/1357633X211052220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Armstrong J, Toscano M, Kotchko N, et al. Utilization and outcomes of BRCA genetic testing and counseling in a national commercially insured population: the ABOUT study. JAMA Oncol. 2015; 1(9):1251–1260. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. DeFrancesco MS, Waldman RN, Pearlstone MM, et al. Hereditary cancer risk assessment and genetic testing in the community-practice setting. Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 132(5):1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Westby A, Nissly T, Gieseker R, Timmins K, Justesen K.. Achieving equity in telehealth: ‘centering at the margins’ in access, provision, and reimbursement. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021; 34(Supplement):S29–S32. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]