Abstract

Study design

Retrospective case-series study

Objectives

To assess (1) low cone beam CT (CBCT) mediated intraoperative navigation to limit radiation exposure without compromising surgical accuracy, and (2) the potential of intraoperative C-arm CBCT navigation to augment pedicle screw (PS) placement accuracy in AIS surgery compared to pre-surgery CT-based planning.

Methods

The first part involved a prospective phantom study, comparing radiation doses for conventional CT, and standard (6sDCT) and a low dose (5sDCT) Artis Zeego®-imaging. Next, 5sDCT- and 6sDCT-navigation were compared on PS accuracy and radiation exposure during AIS correction. The final part compared surgical AIS deformity correction through intraoperative 5sDCT navigation to a matched cohort treated using conventional pre-surgery CT-scans for navigation. Outcome parameters included operation time, skin dose (SD), dose area product (DAP), intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complications, and PS deviation rates.

Results

The phantom study demonstrated a reduction in radiation for the 5sDCT protocol. Moreover, 5sDCT-imaged patients (n = 15) showed a significantly lower SD (-27.41%) and DAP (-30.92%), without compromising PS accuracy compared with 6sDCT-settings (n = 15). Finally, AIS correction through intraoperative CBCT C-arm navigation (n = 27) significantly reduced screw deviation rates (6.83% versus 10.75%, P = .016) without increasing operation times, compared with conventional CT (n = 37).

Conclusions

Intraoperative navigation using a CBCT C-arm system improved the accuracy of PS insertion and reduced surgery time. Moreover, it reduced radiation exposure compared with conventional CT, which was further curtailed by adapting the low-dose 5sDCT protocol. In short, our study highlights the benefits of intraoperative CBCT navigation for PS placement in AIS surgery.

Keywords: cone beam CT, idiopathic scoliosis, screw perforation, radiation dose, navigation, artis zeego

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a complex disorder that involves a curvature and rotation deformity of the spine. While its prevalence is estimated at .5%–5.2%, 1 the etiology of AIS remains largely elusive.2,3 Curvature corrections aimed to alleviate disability, reduce neurological risk, and improve patients’ self-image generally involve surgical translation and rotation techniques followed by spinal fixation.4-7 Contemporary correction maneuvers employ instrumentation comprising pedicle screws (PS) to provide a strong fixational force enabling vertebral manipulation and correction maintenance. PS insertion requires meticulous care not to impair adjacent and critical nerve and vasculature structures. Generally, PS placement is attempted following careful preoperative planning, direct visualization, and pedicle probing.8,9 Nevertheless, detection of pedicle breaches remains challenging.

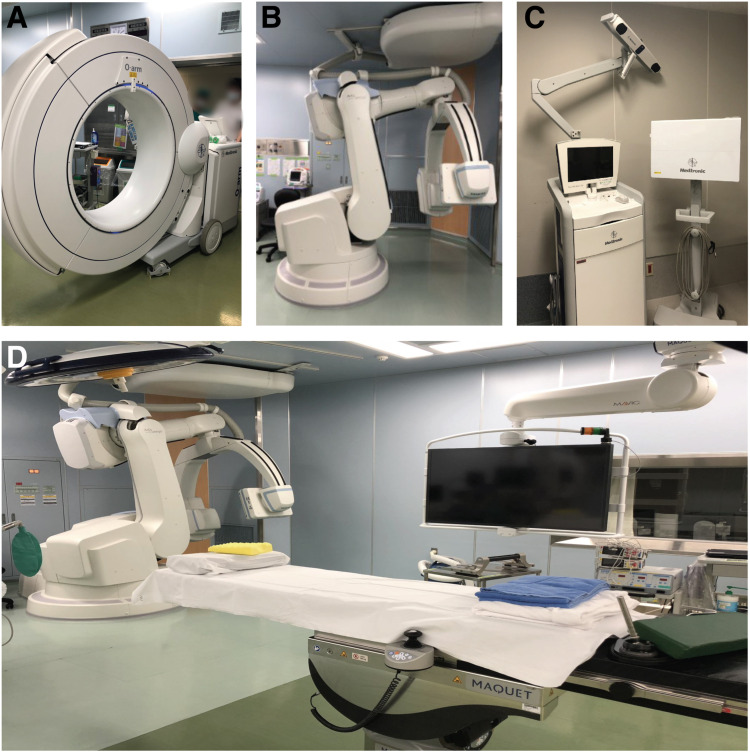

Intraoperative imaging and navigation techniques have become commonplace for instrumented spinal surgeries, including hybrid operating rooms (ORs) with incorporated navigation systems.10,11 (Figure 1) Such floor-mounted C-arm multi-axis robotic cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) 3D-imaging devices (Figures 1B and 1D) rely on a cone-shaped X-ray beam emitted towards a two-dimensional (2D) detector that is rotated once around the patient, generating complete volumetric data in a single rotation. It is unlike conventional CT scans, which rely on fan-shaped X-ray beams that create slice-by-slice images to construct a stacked 3D image.12,13 As a result, CBCT has been suggested to decrease the amount of radiation exposure compared with conventional CT methods. 17 Intraoperative CBCT also has the potential advantage of enabling direct repositioning of misplaced screws, thereby reducing re-operating rates and postoperative CT scans. Work by Cordemans et al highlighted that intraoperative CBCT allows for accurate measurement of screw misplacement similar to postoperative CT scans in their spinal surgery cohort. 14 Identical conclusions were made by Burström et al. 15 Both studies involved patients undergoing spinal fusion for a range of spinal diseases, including malignancies and trauma. One study by Oba et al 16 specifically examined the potential utility of intraoperative CBCT for AIS corrective surgery. However, they did not compare outcomes with other navigation techniques nor did they record radiation exposure.

Figure 1.

Illustrative overview of imaging and navigation equipment described in this study. (A) O-arm™ Surgical Imaging System (Medtronic Inc, Memphis, TN, USA; not used), (B) Robotic C-arm system Artis Zeego® (Siemens AG, Forchheim, Germany), (C) StealthStation® S7® (Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA), and (D) Magnus Operating Table System (Maquet, Rastat, Germany) within a hybrid operating room.

AIS correction engenders a particularly challenging surgical procedure due to the relatively small and abnormally angled pedicles. As such, navigation techniques are ideally examined on AIS patients specifically. Moreover, AIS patients are relatively young individuals, exacerbating potential radiation exposure risks,17,18 although others argue against an overemphasis on this aspect. 19 Considering these limitations of the contemporary literature, by this retrospective study consisting of three separate parts, we aim to (1) validate the potential of a low-exposure protocol for the Artis Zeego® to reduce radiation exposure while maintaining surgical precision, and (2) to examine potential improvements in safety and accuracy of PS insertion for AIS deformity correction guided by intraoperative robotic C-arm CBCT system compared with a matched cohort planned for conventional presurgical CT navigation.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

All procedures described were performed in accordance with ethical standards directed by and upon approval of our institutional review board and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. (12R-036, 16R-052) Informed consent for analysis of medical records was provided by participants or their respective parent(s) or legal guardian(s). Medical records were screened for AIS patients who underwent posterior (or anterior and posterior) correction and spinal fusion (PSF) from Jan 2015 to Jan 2020. Patient records were eligible if patients were mainly classified as thoracic curve scoliosis (T2–T12) with Lenke type 1 to 3.

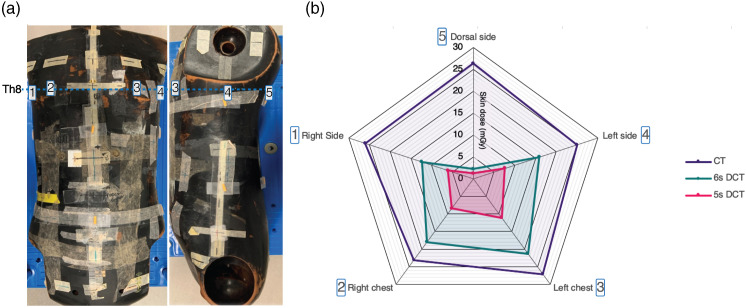

The first part of the study aimed to get a general impression of radiation dosage involved in the different imaging settings using in-phantom dose measurements with radiophotoluminescence glass dosimeters (Chiyoda Technol Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The dosimeters were attached to five locations at thoracic vertebrae level 8 on the back, right and left side, and right and left chest of the phantom (Figure 2A). Effective doses were measured using standard CT equipment (SOMATOM Definition Edge, Siemens AG) and the Artis Zeego® system. Artis Zeego® runs on syngo DynaCT (Siemens AG), which provides a standard 6-second spin (6sDCT) protocol. 17 In our institution, a “low-exposure protocol” has been adapted involving 248 projections during a 5-second spin (5sDCT; see Supplemental Figure 1 for a settings overview). Standard CT, 5sDCT, and 6sDCT imaging measurements were each taken once to evaluate dosimetric readings.

Figure 2.

(A) Radiophotoluminescence glass dosimeter on anthropomorphic phantom at thoracic vertebrae level 8 (Th8); [1] Right side, [2] Right chest, [3] Left chest, [4] Left side, and [5] Dorsal side. (B) Skin dose (SD) measured at each site using conventional computed tomography (CT), or cone beam CT (CBCT) using 6sDCT or 5sDCT settings.

The second part of the study involved the validation of radiation exposure reduction by the 5sDCT protocol while retaining accurate PS placement during AIS surgery. The 5sDCT cohort was compared to a historical AIS patient cohort treated under the 6sDCT navigation settings. Postoperative images to detect PS deviations were obtained through the 5sDCT or 6sDCT settings for the 6sDCT cohort.

To assess improved PS accuracy through intraoperative CBCT navigation, the third study part, included patients that underwent surgical correction using the intraoperative robotic CBCT C-arm with 5sDCT within the hybrid OR (L-group) treated from Jan 2017 to Jan 2020. The cohort was matched to a historical AIS cohort (treated from Jan 2015 to Dec 2016) who underwent similar procedures in a standard OR using pre-surgery CT-scans for navigation (M-group). Cohort matching for both the second and third study parts was based on patient age, height, weight, Lenke type, 20 and Cobb angle.

Surgical Intervention

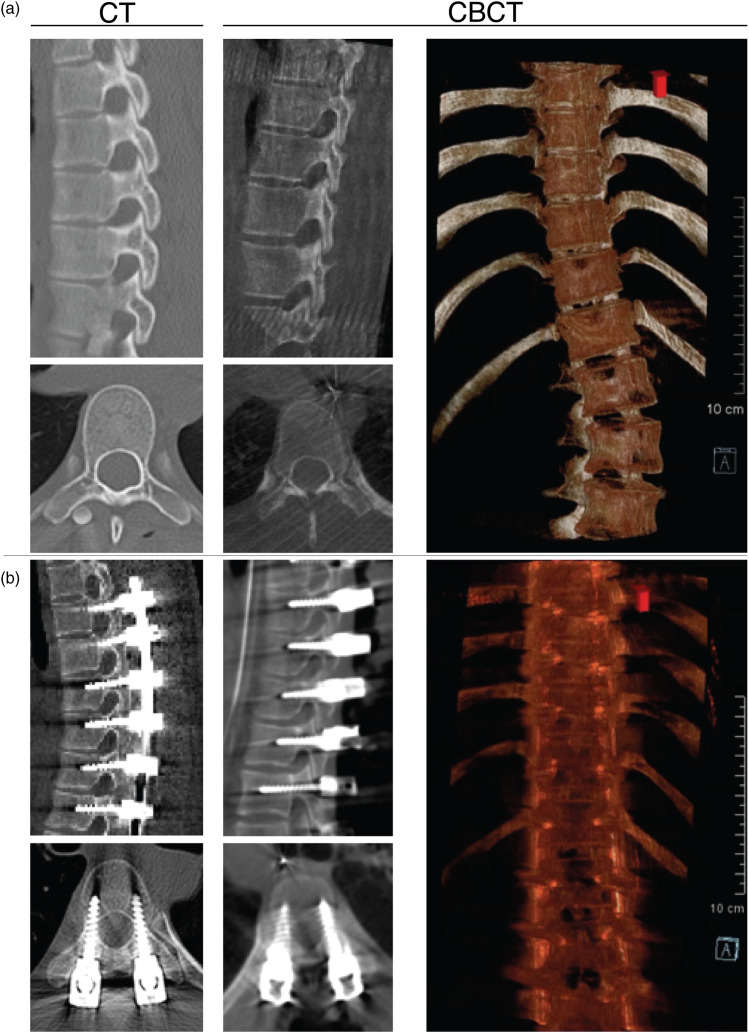

All surgical procedures were performed by the same spine surgeon. Patients were placed in the prone position during PSF with instrumentation. Generally, two titanium PS were employed per vertebral level, however, if the surgeon considered the pedicle too small or fragile, the insertion could be skipped or PS could be replaced by hooks. Before insertion of the PS, the inferior and superior articular processes within the to-be-fixed range were resected. The hybrid OR encompassed a radiolucent Magnus Operating Table System (Maquet, Rastat, Germany) and a StealthStation® S7® navigation system (Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA; Figures 1C and 1D). Surgical navigation was performed using surface registration based on the intraoperative CBCT images (L-group; see Video 1 for 3D reconstruction) or the preoperative CT images (M-group; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Comparing navigation images from conventional CT and intraoperative CBCT scan. Pictures represent sagittal and axial views of representative AIS spines (A) pre- and (B) post-surgical instrumented deformity correction. For a representative animation of the CBCT 3D images see Video 1. (CBCT: cone-beam computed tomography, CT: computed tomography). Video 1. Example of spine 3D reconstruction using our 5sDCT CBCT scan technique of spine pre- and post-surgical correction.

Outcome Parameters

For each patient, standard demographics, preoperative radiographic assessments (i.e., main Cobb angle and Lenke type 20 ), and surgical features were registered. Similarly, screw deviation rates (assessed postoperatively using intraoperatively obtained CBCT-images or postoperative CT images) were evaluated (Video 1). Screw deviations were qualified according to Nakanishi et al 21 with grade 2 or higher being considered violations. Patient records were also examined for serious or severe adverse events up to 2 years following deformity correction, including neurological, vascular, and infectious complications.22,23 Finally, radiation exposure was determined for the 5sDCT, 6sDCT, and L-groups as dose area product (DAP) and skin dose (SD).24-27

Statistical Analysis

All data were collected and processed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Co. Ltd, Redmond, WA). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation unless stated otherwise. Comparisons between patient groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U test or chi-square test. A P value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Part 1: Phantom Dose Measurements

The SD was measured as 25.5 ± 1.6 mGy, 14 ± 7.3 mGy, and 6.9 ± 3.7 mGy in the CT group, 6sDCT, and 5sDCT, respectively (Figure 2B). The SD was higher in the CT group than in the 5sDCT. Moreover, CT showed a clear trend of higher SD compared with the 6sDCT. Minimal radiation was measured at the dorsal side, likely due to the 200° imaging rotation for CBCT compared with the 360° rotation for the CT scan. Overall, both CBCT methods showed a clear SD reduction, with 44.8 ± 29.1% and 72.9 ± 14.2% reduction compared with CT for 6sDCT and 5sDCT, respectively (Supplemental Table 1).

Part 2: 5sDCT Protocol Assessment

In total, 30 patients were included, 15 patients for 6sDCT and 15 patients for 5sDCT navigation with no significant differences in demographic distributions (Table 1). Post-operative parameters revealed a significantly longer surgical time (P = .001) for the 5sDCT cohort, likely due to a larger fused region (P = .037). Regardless, the 5sDCT setting was able to significantly reduce radiation exposure levels (Table 2); DAP was measured as 38.4 ± 11.4 Gy/cm2 for 6sDCT and 26.5 ± 11.8 Gy/cm2 for 5sDCT (P = .003). Similarly, an SD of 126.2 ± 37.3 mGy for 6sDCT was significantly (P = .004) higher than 91.6 ± 34.8 mGy for 5sDCT. Despite the lower exposure, the rate of screw deviations remained similar (P = .120) with 24 of 290 (8.3%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 5.37-12.06%) screw violations for 6sDCT compared with 16 of 314 (5.1%, CI: 2.94-8.14%) for 5sDCT.

Table 1.

Tabular summary of demographic patient characteristics of part 2 included for assessment of low-exposure (5sDCT) protocol.

| 6sDCT | 5sDCT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | P-value | ||

| Participants | 15 | 15 | |||||

| Sex (male: Female) | 1:14 | 0:15 | .31 | ||||

| Lenke type | .56 | ||||||

| Type Ⅰ | 11 | 73.3% | 13 | 86.6% | |||

| Type Ⅱ | 3 | 20.0% | 1 | 6.7% | |||

| Type Ⅲ | 1 | 6.7% | 1 | 6.7% | |||

| Mean | ±SD | (Range) | Mean | ±SD | (Range) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 15.1 | ±1.2 | (13-17) | 15.3 | ±2.5 | (12-21) | .64 |

| Height (cm) | 156.2 | ±7.5 | (146-171) | 157.3 | ±5.6 | (146-167) | .37 |

| Weight (kg) | 45.4 | ±6.3 | (36.3-60.4) | 47.1 | ±7.5 | (34.0-63.5) | .42 |

| Main preoperative CA (°) | 44.7 | ±8.3 | (35-61) | 53.6 | ±15.6 | (35-81) | .13 |

| Fused vertebrae (n//patient) | 8.9 | ±0.8 | (8-11) | 9.6 | ±1.0 | (8-12) | .04 |

| PS density (PS/patient) | 19.3 | ±2.0 | (16-24) | 20.9 | ±2.1 | (18-26) | .046 |

CA: Cobb angle, n/a: not applicable, PS: pedicle screw, SD: standard deviation. Significant P-values are marked in bold.

Table 2.

Tabular summary of post-operative outcome parameters of part 2 for assessment of low-exposure (5sDCT) protocol. DAP: dose area product, DR: screw deviation rate, SD: standard deviation, n/a: not applicable. Significant P-values are marked in bold.

| 6sDCT | 5sDCT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Mean | ±SD | (Range) | Mean | ±SD | (Range) | P-value |

| Surgical time (min) | 204.7 | ±45.2 | (139-283) | 298.1 | ±77.1 | (163-485) | <.001 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 209.1 | ±275.6 | (30-1100) | 200.2 | ±198.3 | (16-705) | .60 |

| DAP (Gy/cm2) | 38.4 | ±11.4 | (23.2-67.5) | 26.5 | ±11.8 | (8.5-58.2) | .003 |

| Skin dose (mGy) | 126.2 | ±37.3 | (76.3-219.3) | 91.6 | ±34.8 | (38.0-190.5) | .004 |

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | P-value | |||

| DR (deviation/total screws) | 24/290 | 8.3% | 16/314 | 5.1% | .12 | ||

| Post-surgery complications | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | n/a | ||

Part 3: Intraoperative CBCT Imaging Compared With Pre-surgery CT Imaging

For the third part, 27 patients were categorized in the L-group and 37 in the M-group. There were no differences in group characteristics (Table 3). All surgeries were successfully performed, and no postoperative complications such as neurovascular injury or adverse events resulting from pedicle violations were monitored during up to two years follow-up (Figure 3B). Average operation times showed a significant reduction (P = .033) in the L-group: 256.9 ± 79.7 min compared with 298.6 ± 79.1 min in the M-group. Intraoperative blood loss showed a nonsignificant (P = .084) decrease in the L-group (174.2 ± 172.0 mL) relative to the M-group (239.5 ± 167.9 mL). In total, 542 screws were employed in the L-group (20.1 ± 2.3/patient) and 735 screws in the M-group (19.9 ± 2.2/patient; P = .840). For the M-group 35 of 770 PS were skipped or replaced by hooks compared to 12 of 554 PS in the L-group. (P = .021) Thirty-seven out of 542 PS in the L-group (6.8%, CI: 4.9-8.6%) and 79 out of 735 PS in the M-group (10.8%, CI:9.3-13.2%) were classified as PS violations (P = .016). The L-group received a DAP of 31.4 ± 12.7 Gy/cm2 (Median: 30.0 Gy/cm2) and an SD of 105.4 ± 38.8 mGy (Median: 97.0 mGy; Table 4).

Table 3.

Tabular summary of demographic patient characteristics of part 3: comparing conventional pre-surgery CT navigation (M-group) with intraoperative robotic C-arm 3D CBCT imaging navigation (L-group). CA: cobb angle, PS: pedicle screw, SD: standard deviation.

| L-Group | M-group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | P-value | ||

| Participants | 27 | 37 | |||||

| Sex (male: Female) | 1:26 | 3:34 | .47 | ||||

| Lenke type | .35 | ||||||

| Type Ⅰ | 21 | 78% | 25 | 68% | |||

| Type Ⅱ | 4 | 15% | 7 | 19% | |||

| Type Ⅲ | 2 | 7% | 5 | 13% | |||

| Mean | ±SD | (Range) | Mean | ±SD | (Range) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 15.1 | ±2.0 | (12-21) | 15.9 | ±2.6 | (12-26) | .21 |

| Height (cm) | 157.1 | ±6.8 | (146-171) | 157.0 | ±8.9 | (143-180) | .74 |

| Weight (kg) | 46.5 | ±7.0 | (34.0-63.5) | 49.2 | ±11.3 | (30.0-95.0) | .20 |

| Main preoperative CA (°) | 49.3 | ±13.8 | (33-81) | 49.0 | ±10.9 | (36-78) | .68 |

| Fused vertebrae (n//patient) | 9.3 | ±1.0 | (8-12) | 9.4 | ±1.3 | (7-12) | .58 |

| PS density (PS/patient) | 20.1 | ±2.3 | (16-26) | 19.9 | ±2.2 | (15-25) | .84 |

Table 4.

Tabular summary of post-operative outcome parameters of part 3: comparing conventional pre-surgery CT navigation (M-group) with intraoperative robotic C-arm 3D CBCT imaging (L-group).

| L-Group | M-group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Mean | ±SD | (Range) | Mean | ±SD | (Range) | P-value |

| Surgical time (min) | 256.9 | ±79.7 | (139-485) | 298.6 | ±79.1 | (168-477) | .03 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 174.2 | ±172.0 | (16-705) | 239.5 | ±167.9 | (28-762) | .08 |

| DAP (Gy/cm2) | 31.4 | ±12.7 | (8.5-67.5) | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Skin dose (mGy) | 105.4 | ±38.8 | (38.0-219.3) | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | P-value | |||

| Skipped PS (screw/sites) | 12/554 | 2.2% | 35/770 | 4.6% | .02 | ||

| DR (deviation/total PS) | 37/542 | 6.8% | 79/735 | 10.8% | .02 | ||

| Post-surgery complications | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | n/a | ||

DAP: dose area product, DR: screw deviation rate, PS: pedicle screw, SD: standard deviation, n/a: not applicable. Significant P-values are marked in bold.

Discussion

As surgical navigation with intraoperative CBCT has become more prevalent, concerns have been raised regarding potential surgery time extensions.28-30 Surprisingly, in our study, we found that intraoperative robotic C-arm CBCT actually significantly reduced surgery time. One explanation could be the additional time taken for intraoperative CT scans in the M-group after screw insertion to assess potential screw deviation after corrective manipulation. Notably, however, the surgery time within the L-group could likely be further reduced if we had applied automatic registration instead of manual registration. Our literature review (Supplemental Table 2, for an overview of identified studies) of CBCT-guided PS-based instrumented spinal surgeries suggests that our average time of 260 min is in line with other studies employing intraoperative C-arm imaging. For example, Tajsic et al 31 and Oba et al 16 presented surgery times of 211 min and 236 min respectively. Additionally, the intraoperative CBCT provided lower rates of skipped PS, suggesting the CBCT based navigation offers higher confidence to the surgeon to employ PS insertion than navigation based on pre-operative CT-scans.

It is important to justify and optimize radiation doses. The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) promotes three principles of radiological protection: justification, optimization, and dose limits. 32 Specifically, the 2011 “ICRP Statement on Tissue Reaction” has set the exposure limit of 20 mSV a year upon the eye lens. 33 Medical workers can take various actions to reduce radiation exposure. For example, surgeons and accompanying staff can be located outside the OR during the imaging process. Moreover, while exposure to patients cannot be avoided, the incidental dosages applied with modern imaging equipment are relatively low and potentially negligible. 19 By contrast, others have emphasized the higher rates of cancer among patients with scoliosis and caution against radiography. For example, a recent metanalysis by Luan et al 18 found that among 3301 patients with general adolescent scoliosis, 532 developed cancer (17.6%) following a period of ≥20 years, compared with 457 cases among 3045 (13.1%) in a control cohort. The authors attributed this increase to radiation exposure during the management of scoliotic deformity. 18 In our view, this assumption is somewhat presumptuous, as the studies included do not directly correlate radiation dose with carcinogenesis or propose alternative hypotheses. 19 Instead, Oakley et al hypothesized that the enhanced cancer rates might be inherent to the scoliotic pathology itself. 19 Noticeably, few reports have examined radiation doses in patients undergoing spinal instrumentation by C-arm CBCT. Cordemans et al reported a DAP of 81.6 Gy/cm2 and SD of 267 mGy, while Kaminski et al reported a DAP of 82.8 Gy/cm2 and SD of 273 mGy, both of which are double the amount measured in our cohort.14,34 Gebhard et al found that iso-C3D-arm-guided spinal fusion resulted in higher doses of 664 mGy. 35 Kobayashi et al 36 measured SD of 401 mGy for AIS surgeries using the O-arm™. These findings suggest that radiation exposure through robotic C-arm CBCT devices tends to be lower than conventional CT. Moreover, considering our suggestion that intraoperative CBCT removes the need for post-correction CT-scans, we conclude that intraoperative CBCT-mediated navigation can reduce radiation exposure during AIS surgery.

Finally, we assessed the ability of CBCT navigation to enhance PS insertion accuracy. A systematic review on the deviation rate of thoracic and lumbar screws reported a proportion of 3%–20% with the freehand technique, 0%–7% with CT navigation, and 0%–29% with fluoroscopy-based navigation. 37 In recent reports on O-arm™ navigation for idiopathic scoliosis corrections, Kotani et al and Oba et al reported a 3.1% and 2.7% deviation rate respectively.29,38 A review by Bohoun et al 39 of 16 studies reporting on fusion surgery using intraoperative O-arm™ imaging concluded that perforation rates were 1%–27%. Taken together, these findings suggest that O-arm™ navigation could potentially contribute to safer and more accurate screw insertion than conventional procedures. Very few publications report on screw deviation rates in C-arm CBCT navigated scoliosis surgeries, but our literature review includes reporting of 347 identified screw deviations (using the highest rates) among 4903 inserted PS (7.08%; Table 5). Combining 5sDCT cohorts from the second and third parts of our study, we found an overall screw deviation rate of 6.6% using the Artis Zeego®, which is in line with other reports. It should be noted that the identified studies employed screw instrumentation for a wide range of spinal diseases. In addition, the included studies applied varying classification methods to identify PS deviations, again limiting direct comparison (Supplemental Table 3, for an overview of classification schemes). Notably, the largest number of studies employed the Gertzbein and Robbins’ classification scheme, 40 which was primarily designed for adult vertebral fracture patients. Whether the 2 mm threshold is sufficiently cautions for adolescent AIS patients with relatively smaller pedicles, remains to be determined. Moreover, as highlighted by Floccari et al 41 significant variability among surgeons’ opinions exist as to which PS should be maintained or should be corrected. Alternatively, future work could consider employing specific measurements e.g., screw size distortion, as a direct comparison of radiography quality between CT and CBCT images and devices. Although, in our study, primarily titanium screws were employed, which represent less distortion on 3D-imaging 42 and thus this imaging-effect did likely not strongly affect results. Nevertheless, we are of the opinion that our results show a beneficial trend for intraoperative C-arm CBCT navigation to enhance the accuracy of PS placement.

Table 5.

Literature review of pedicle screw deviation rates in pedicle screw instrumentation based spinal surgery using intraoperative C-arm 3D CBCT-based imaging navigation. The overview only includes studies involving human observation, i.e. animals or phantom dummies were not included into the overview. Values are presented as the total number of detected screw deviations/total number of screws (percentage of total). Note the differences in classification systems employed in quantifying screw deviations. An overview on the specifics of deviation-criteria of each classification scheme is presented in Supplemental Table 2. AR: supported by augmented reality, RA: Robot-assisted.

| Authors | Year | Ref | Equipment | Classification | Ref | Deviation rate | (%) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holly et al. | 2003 | 43 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Custom | — | 5/94 | (5.3%) | |

| Holly et al. | 2006 | 44 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Custom | — | 1/42 | (2.4%) | |

| Lekovic et al. | 2008 | 45 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Mirza | 46 | 5/94 | (5.3%) | |

| Rajasekaran et al. | 2008 | 47 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Custom | — | 7/242 | (2.9%) | |

| Ito et al. | 2008 | 48 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Unspecified | — | 5/176 | (2.8%) | |

| Smith et al. | 2008 | 49 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Unspecified | — | 2/24 | (8.3%) | |

| Nakashima et al. | 2009 | 50 | Iso-C 3-dimensional | Custom | — | 11/150 | (7.3%) | |

| Liu et al. | 2010 | 51 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Custom | — | 13/140 | (9.2%) | |

| Sugimoto et al. | 2010 | 52 | Siremobil Iso- C3D | Rajasekaran | 47 | 6/154 | (3.9%) | |

| Elmi-Terander et al. | 2016 | 53 | AlluraClarity FD20 | Gertzbein | 40 | 7/47 | (14.9%) | |

| Kaminski et al. | 2017 | 34 | Artis Zeego | — | — | — | — | |

| Cordemans et al. | 2017 | 14 | Artis Zeego II | Gertzbein | 40 | 42/348 | (12.1%) | |

| Heary | 54 | 50/358 | (14.4%) | AR | ||||

| Cordemans et al. | 2017 | 55 | Artis Zeego II | Gertzbein | 40 | 81/695 | (11.7%) | |

| Heary | 54 | 107/695 | (15.4%) | |||||

| Hyun et al. | 2017 | 56 | Unspecified | Gertzbein | 40 | 0/130 | (.0%) | |

| Fujimori et al. | 2017 | 57 | Ziehm Vision FD V ario | Upendra | 58 | 10/203 | (4.9%) | |

| Kageyama et al. | 2017 | 59 | Artis Zeego | Neo | 60 | 6/50 | (12.0%) | |

| Bohoun et al. | 2018 | 39 | AlluraClarity FD20 | Custom | — | 8/313 | (2.6%) | RA |

| Takahata et al. | 2018 | 61 | INFX-8000H | Hojo | 62 | 4/166 | (2.4%) | |

| Tajsic et al. | 2018 | 31 | Arcadis Orbic | Unspecified | — | 14/192 | (7.3%) | |

| Elmi-Terander et al. | 2019 | 63 | AlluraClarity FlexMove | Gertzbein | 40 | 15/253 | (5.9%) | |

| Edstrom et al | 2020 | 64 | Unspecified | Gertzbein | 40 | 15/240 | (6.3%) | |

| Edstrom et al | 2020 | 65 | Allura FlexMove | — | — | — | — | AR |

| McClendon et al. | 2020 | 66 | ARTIS Pheno | — | — | — | — | AR |

| Oba et al. | 2020 | 16 | ARTIS Pheno | Gertzbein | 40 | 18/531 | (3.9%) | |

| Tkatschenko et al. | 2020 | 67 | Artis Zeego II | Modified Gertzbein | 68 | 0/32 | (.0%) | AR |

| Burstrom et al | 2021 | 15 | Allura Xper FD20 | — | — | — | — | |

| Current study | Artis Zeego II | Nakanishi | 21 | 40/604 | (6.6%) |

One limitation of our study is that we did not measure the radiation exposure from the preoperative CTs in the M-group and, thus, were unable to directly compare exposure rates between the groups. However, our phantom study revealed a clearly reduced exposure rate for the CBCT techniques. Another limitation is the retrospective and nonrandomized nature of the study. Although case matching was applied, the different periods for each cohort in which the corrections took place might also have affected the outcomes. Moreover, our findings were obtained under specific imaging conditions set at our institute and thus might vary when operated by others. Even so, cumulatively our data and other reports suggest that intraoperative CBCT navigation allows for enhanced PS accuracy, operating time reductions, and a suggested lower radiation exposure. Accordingly, we are of the opinion that these benefits outweigh the likely small risk increase 26 provoked by the low-radiation exposure generated by CBCT. Moreover, future developments in software and equipment, are likely to enable radiation dosage reduction without compromising on resolution and accuracy. These advancements are highly encouraged.

Conclusion

In summary, intraoperative CBCT navigation with a robotic C-arm device for AIS surgery reduced PS deviation rates and radiation exposure compared with conventional preoperative CT-based procedures. Moreover, our low-dose 5sDCT setting was able to reduce radiation dosages significantly without compromising PS accuracy.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Low Radiation Protocol for Intraoperative Robotic C-Arm Can Enhance Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Deformity Correction Accuracy and Safety by Masahiro Tanaka, MD, PhD, Jordy Schol, MSc, Daisuke Sakai, MD, PhD, Kosuke Sako, MD, Kazuyuki Yamamoto, MD, Kensuke Yanagi, MD, Akihiko Hiyama MD, PhD, Hiroyuki Katoh MD, PhD, Masato Sato MD, PhD, and Masahiko Watanabe M in Global Spine Journal.

Video 1

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Hiroyuki Kobayashi, M.D., PhD (Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara, Japan) for his support and advice for the statistical analysis, and Natsumi Horikita (Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara, Japan) for her support in processing and animating the CT-images for publication.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Jordy Schol https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5489-2591

Kensuke Yanagi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5286-4535

Akihiko Hiyama https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2474-9118

Hiroyuki Katoh https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0046-3008

References

- 1.Konieczny MR, Senyurt H, Krauspe R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of children's orthopaedics. 2013;7(1):3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smit TH. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: The mechanobiology of differential growth. JOR Spine. 2020;3(4):e1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng Y, Wang SR, Qiu GX, Zhang JG, Zhuang QY. Research progress on the etiology and pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Chinese medical journal. 2020;133(4):483-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasler CC. A brief overview of 100 years of history of surgical treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of children's orthopaedics. 2013;7(1):57-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai D, Schol J, Hiyama A, et al. Simultaneous translation on two rods improves the correction and apex translocation in adolescent patients with hypokyphotic scoliosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021;34(4):597-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafon Y, Lafage V, Dubousset J, Skalli W. Intraoperative three-dimensional correction during rod rotation technique. Spine. 1976;34(5):512-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakai D, Tanaka M, Takahashi J, et al. Cobalt-chromium versus titanium alloy rods for correction of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis based on 1-year follow-up: a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021;34(6):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe K, Matsumoto M, Tsuji T, et al. Ball tip technique for thoracic pedicle screw placement in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(2):246-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donohue ML, Moquin RR, Singla A, Calancie B. Is in vivo manual palpation for thoracic pedicle screw instrumentation reliable? J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(5):492-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirose T, Otsuka K, Nagano H, et al. Evaluation of Spinal Surgery within the Hybrid Operating Room. J Chugoku-Shikoku Orthop Assoc. 2015;27(2):277-281. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shigeru S, Takeshi I, Yosuke N, et al. Evaluation of Navigation Surgery for Scoliosis Using Intra-operative Real-time CT. J Spine Res. 2011;2:1592-1595. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatesh E, Elluru SV. Cone beam computed tomography: basics and applications in dentistry. J Istanbul Univ Fac Dent. 2017;51(3 suppl 1):S102-S121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orth RC, Wallace MJ, Kuo MD. C-arm cone-beam CT: general principles and technical considerations for use in interventional radiology. J Vasc Intervent Radiol : J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;20(7 suppl l):S538-S544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordemans V, Kaminski L, Banse X, Francq BG, Cartiaux O. Accuracy of a new intraoperative cone beam CT imaging technique (Artis zeego II) compared to postoperative CT scan for assessment of pedicle screws placement and breaches detection. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(11):2906-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burström G, Cewe P, Charalampidis A, et al. Intraoperative cone beam computed tomography is as reliable as conventional computed tomography for identification of pedicle screw breach in thoracolumbar spine surgery. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(4):2349-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oba H, Ikegami S, Kuraishi S, et al. Perforation Rate of Pedicle Screws Using Hybrid Operating Room Combined With Intraoperative Computed Tomography Navigation for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine. 2020;45(20):E1357-E1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demirel A, Pedersen PH, Eiskjær SP. Cumulative radiation exposure during current scoliosis management. Danish medical journal. 2020;67(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luan FJ, Wan Y, Mak KC, Ma CJ, Wang HQ. Cancer and mortality risks of patients with scoliosis from radiation exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(12):3123-3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oakley PA, Ehsani NN, Harrison DE. The Scoliosis Quandary: Are Radiation Exposures From Repeated X-Rays Harmful? Dose-response : A Publication of International Hormesis Society. 2019;17(2):1559325819852810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 2001;83(8):1169-1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi K, Tanaka M, Misawa H, Sugimoto Y, Takigawa T, Ozaki T. Usefulness of a navigation system in surgery for scoliosis: segmental pedicle screw fixation in the treatment. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(9):1211-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi D, Roemer FW, Mian A, Gharaibeh M, Müller B, Guermazi A. Imaging features of postoperative complications after spinal surgery and instrumentation. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(1):W123-W129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuroiwa M, Schol J, Sakai D, et al. Predictive Factors for Successful Treatment of Deep Incisional Surgical Site Infections following Instrumented Spinal Surgeries: Retrospective Review of 1832 Cases. Diagnostics. 2022;12(2):551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stecker MS, Balter S, Towbin RB, et al. Guidelines for patient radiation dose management. J Vasc Intervent Radiol : J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;20(7 suppl l):S263-S273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balter S. Methods for measuring fluoroscopic skin dose. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):136-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Electrotechnical Commission . Medical electrical equipment-part 2-43. In. Particular Requirement for the Safety of X-Ray Equipment for Interventional Procedures. 2nd edition. Geneva, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul J, Jacobi V, Farhang M, Bazrafshan B, Vogl TJ, Mbalisike EC. Radiation dose and image quality of X-ray volume imaging systems: cone-beam computed tomography, digital subtraction angiography and digital fluoroscopy. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(6):1582-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin M, Liu Z, Liu X, Yan H., Han X., Qiu Y., Zhu Z. Does intraoperative navigation improve the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in the apical region of dystrophic scoliosis secondary to neurofibromatosis type I: comparison between O-arm navigation and free-hand technique. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(6):1729-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotani T, Akazawa T, Sakuma T, et al. Accuracy of Pedicle Screw Placement in Scoliosis Surgery: A Comparison between Conventional Computed Tomography-Based and O-Arm-Based Navigation Techniques. Asian Spine Journal. 2014;8(3):331-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebara S. Spinal surgery with Robotic C-arm System “Artis zeego” – Anterior VATS external correction and internal fixation surgery. J MIOS. 2015;76:79-87. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tajsic T, Patel K, Farmer R, Mannion RJ, Trivedi RA. Spinal navigation for minimally invasive thoracic and lumbosacral spine fixation: implications for radiation exposure, operative time, and accuracy of pedicle screw placement. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(8):1918-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Protection ICoR. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 103. Ann ICRP. 1990;37(1-3):1-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Authors on behalf of I, Stewart FA, Akleyev AV, et al. ICRP publication 118: ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs--threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann ICRP. 2012;41(1-2):1-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaminski L, Cordemans V, Cartiaux O, Van Cauter M. Radiation exposure to the patients in thoracic and lumbar spine fusion using a new intraoperative cone-beam computed tomography imaging technique: a preliminary study. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(11):2811-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebhard FT, Kraus MD, Schneider E, Liener UC, Kinzl L, Arand M. Does computer-assisted spine surgery reduce intraoperative radiation doses? Spine. 2006;31(17):2024-2028. ; discussion 2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi K, Ando K, Ito K, et al. Intraoperative radiation exposure in spinal scoliosis surgery for pediatric patients using the O-arm imaging system. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28(4):579-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelalis ID, Paschos NK, Pakos EE, et al. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement: a systematic review of prospective in vivo studies comparing free hand, fluoroscopy guidance and navigation techniques. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(2):247-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oba H, Ebata S, Takahashi J, et al. Pedicle Perforation While Inserting Screws Using O-arm Navigation During Surgery for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Risk Factors and Effect of Insertion Order. Spine. 2018;43(24):E1463-E1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohoun CA, Naito K, Yamagata T, Tamrakar S, Ohata K, Takami T. Safety and accuracy of spinal instrumentation surgery in a hybrid operating room with an intraoperative cone-beam computed tomography. Neurosurg Rev. 2019;42(2):417-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gertzbein SD, Robbins SE. Accuracy of pedicular screw placement in vivo. Spine. 1976;15(1):11-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Floccari LV, Larson AN, Crawford CH, 3rd, et al. Which Malpositioned Pedicle Screws Should Be Revised? J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(2):110-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elliott MJ, Slakey JB. CT provides precise size assessment of implanted titanium alloy pedicle screws. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1605-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holly LT, Foley KT. Three-dimensional fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous thoracolumbar pedicle screw placement. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(3 suppl l):324-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holly LT, Foley KT. Percutaneous placement of posterior cervical screws using three-dimensional fluoroscopy. Spine. 2006;31(5):536-541.discussion 541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lekovic GP, Potts EA, Karahalios DG, Hall G. A comparison of two techniques in image-guided thoracic pedicle screw placement: a retrospective study of 37 patients and 277 pedicle screws. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(4):393-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirza SK, Wiggins GC, Kuntz Ct, et al. Accuracy of thoracic vertebral body screw placement using standard fluoroscopy, fluoroscopic image guidance, and computed tomographic image guidance: a cadaver study. Spine. 2003;28(4):402-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajasekaran S, Vidyadhara S, Ramesh P, Shetty AP. Randomized clinical study to compare the accuracy of navigated and non-navigated thoracic pedicle screws in deformity correction surgeries. Spine. 2007;32(2):E56-E64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ito Y, Sugimoto Y, Tomioka M, Hasegawa Y, Nakago K, Yagata Y. Clinical accuracy of 3D fluoroscopy-assisted cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9(5):450-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith HE, Welsch MD, Ugurlu RC, Sasso AR, Vaccaro A. Comparison of radiation exposure in lumbar pedicle screw placement with fluoroscopy vs computer-assisted image guidance with intraoperative three-dimensional imaging. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2008;31(5):532-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakashima H, Sato K, Ando T, Inoh H, Nakamura H. Comparison of the percutaneous screw placement precision of isocentric C-arm 3-dimensional fluoroscopy-navigated pedicle screw implantation and conventional fluoroscopy method with minimally invasive surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(7):468-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu YJ, Tian W, Liu B, et al. Comparison of the clinical accuracy of cervical (C2-C7) pedicle screw insertion assisted by fluoroscopy, computed tomography-based navigation, and intraoperative three-dimensional C-arm navigation. Chinese medical journal. 2010;123(21):2995-2998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sugimoto Y, Ito Y, Tomioka M, et al. Clinical accuracy of three-dimensional fluoroscopy (IsoC-3D)-assisted upper thoracic pedicle screw insertion. Acta Med Okayama. 2010;64(3):209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elmi-Terander A, Skulason H, Söderman M, et al. Surgical Navigation Technology Based on Augmented Reality and Integrated 3D Intraoperative Imaging: A Spine Cadaveric Feasibility and Accuracy Study. Spine. 2016;41(21):E1303-E1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heary RF, Bono CM, Black M. Thoracic pedicle screws: postoperative computerized tomography scanning assessment. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(4 suppl):325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cordemans V, Kaminski L, Banse X, Francq BG, Detrembleur C, Cartiaux O. Pedicle screw insertion accuracy in terms of breach and reposition using a new intraoperative cone beam computed tomography imaging technique and evaluation of the factors associated with these parameters of accuracy: a series of 695 screws. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(11):2917-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hyun SJ, Kim KJ, Jahng TA, Kim HJ. Minimally Invasive Robotic Versus Open Fluoroscopic-guided Spinal Instrumented Fusions. Spine. 2017;42(6):353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujimori T, Iwasaki M, Nagamoto Y, et al. Reliability and Usefulness of Intraoperative 3-Dimensional Imaging by Mobile C-Arm With Flat-Panel Detector. Clinical Spine Surgery: A Spine Publication. 2017;30(1):E64-E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Upendra BN, Meena D, Chowdhury B, Ahmad A, Jayaswal A. Outcome-based classification for assessment of thoracic pedicular screw placement. Spine. 2008;33(4):384-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kageyama H, Yoshimura S, Uchida K, Iida T. Advantages and Disadvantages of Multi-axis Intraoperative Angiography Unit for Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Placement in the Lumbar Spine. Neurol Med -Chir. 2017;57(9):481-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neo M, Sakamoto T, Fujibayashi S, Nakamura T. The clinical risk of vertebral artery injury from cervical pedicle screws inserted in degenerative vertebrae. Spine. 2005;30(24):2800-2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahata M, Yamada K, Akira I, et al. A novel technique of cervical pedicle screw placement with a pilot screw under the guidance of intraoperative 3D imaging from C-arm cone-beam CT without navigation for safe and accurate insertion. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(11):2754-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hojo Y, Ito M, Suda K, Oda I, Yoshimoto H, Abumi K. A multicenter study on accuracy and complications of freehand placement of cervical pedicle screws under lateral fluoroscopy in different pathological conditions: CT-based evaluation of more than 1,000 screws. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(10):2166-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elmi-Terander A, Burström G, Nachabe R, et al. Pedicle Screw Placement Using Augmented Reality Surgical Navigation With Intraoperative 3D Imaging: A First In-Human Prospective Cohort Study. Spine. 2019;44(7):517-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edström E, Burström G, Persson O, et al. Does Augmented Reality Navigation Increase Pedicle Screw Density Compared to Free-Hand Technique in Deformity Surgery? Single Surgeon Case Series of 44 Patients. Spine. 2020;45(17):E1085-E1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edström E, Burström G, Nachabe R, Gerdhem P, Elmi Terander A. A Novel Augmented-Reality-Based Surgical Navigation System for Spine Surgery in a Hybrid Operating Room: Design, Workflow, and Clinical Applications. Operative Neurosurgery. 2020;18(5):496-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McClendon J, Almekkawi AK, Abi-Aad KR, Maiti T. Use of Pheno Room, Augmented Reality, and 3-Rod Technique for 3-Dimensional Correction of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. World neurosurgery. 2020;137:291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tkatschenko D, Kendlbacher P, Czabanka M, Bohner G, Vajkoczy P, Hecht N. Navigated percutaneous versus open pedicle screw implantation using intraoperative CT and robotic cone-beam CT imaging. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(4):803-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rampersaud YR, Pik JH, Salonen D, Farooq S. Clinical accuracy of fluoroscopic computer-assisted pedicle screw fixation: a CT analysis. Spine. 2005;30(7):E183-E190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Low Radiation Protocol for Intraoperative Robotic C-Arm Can Enhance Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Deformity Correction Accuracy and Safety by Masahiro Tanaka, MD, PhD, Jordy Schol, MSc, Daisuke Sakai, MD, PhD, Kosuke Sako, MD, Kazuyuki Yamamoto, MD, Kensuke Yanagi, MD, Akihiko Hiyama MD, PhD, Hiroyuki Katoh MD, PhD, Masato Sato MD, PhD, and Masahiko Watanabe M in Global Spine Journal.

Video 1