Abstract

The advancement in pharmaceutical research has led to the discovery and development of new combinatorial life-saving drugs. Rapamycin is a macrolide compound produced from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Rapamycin and its derivatives are one of the promising sources of drug with broad spectrum applications in the medical field. In recent times, rapamycin has gained significant attention as of its activity against cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients. Rapamycin and its derivatives have more potency when compared to other prevailing drugs. Initially, it has been used exclusively as an anti-fungal drug. Currently rapamycin has been widely used as an immunosuppressant. Rapamycin is a multifaceted drug; it has anti-cancer, anti-viral and anti-aging potentials. Rapamycin has its specific action on mTOR signaling pathway. mTOR has been identified as a key regulator of different pathways. There will be an increased demand for rapamycin, because it has lesser adverse effects when compared to steroids. Currently researchers are focused on the production of effective rapamycin derivatives to combat the growing demand of this wonder drug. The main focus of the current review is to explore the origin, development, molecular mechanistic action, and the current therapeutic aspects of rapamycin. Also, this review article revealed the potential of rapamycin and the progress of rapamycin research. This helps in understanding the exact potency of the drug and could facilitate further studies that could fill in the existing knowledge gaps. The study also gathers significant data pertaining to the gene clusters and biosynthetic pathways involved in the synthesis and production of this multi-faceted drug. In addition, an insight into the mechanism of action of the drug and important derivatives of rapamycin has been expounded. The fillings of the current review, aids in understanding the underlying molecular mechanism, strain improvement, optimization and production of rapamycin derivatives.

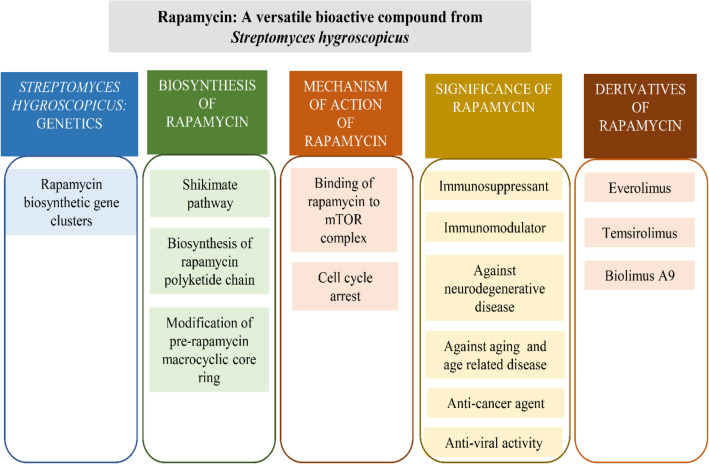

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Autophagy, FKBP-12, Immunosuppressant, Macrolactone, mTOR, Rapamycin, Streptomyces hygroscopicus

Introduction

Streptomyces hygroscopicus can produce more than 180 bio-active metabolites. These metabolites appertain to four different classes of bioactive compounds: regulatory compounds, pharmacological metabolites, agro biological and antagonistic agents [1]. In a recent study it was found that Streptomyces hygroscopicus was capable of biosynthesizing gold and silver nanoparticles which can be employed as potent anti-microbial nanomedicine [2]. This organism is capable of synthesizing various vitally important drugs. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved anti-cancer drugs such as pterocidin and nigercin are produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Pterocidin is a linear polyketide antineoplastic compound with a δ-lactone terminus that was found to have cyto-toxic activity against tumour cells [3, 4]. Other versatile metabolites of S. hygroscopicus encompass ascomycin, rapamycin, geldanamycin, hygromycin, hygrocin, nigercin. Among this, rapamycin is considered as a life sustaining drug with multiple pharmaceutical applications [5].

Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, was discovered as an anti-fungal agent against Candida in 1975 [6, 7]. Later, its efficiency as an immunosuppressant was studied and approved by United States Food and Drug Administration in 1999. After a year, in 2000 European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the administration of rapamycin in patients undergoing organ transplantation [8]. Rapamycin has varied pharmacological activities such as anti-cancer activity, immunosuppressant, anti-aging, anti-diabetic and used against autoimmune diseases [9]. Moreover, rapamycin is an mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor which has less side effects when compared to calcineurin inhibitors like FK506 and Cyclosporine [10].

High demand of rapamycin in the medical field attracted a lot of researchers and pharmaceutical companies to facilitate more research about the bioactive potency of rapamycin. Productivity of available strains of Streptomyces hygroscopicus was very low when compared to its demand in the current scenario. Hence, many pharmaceutical companies are funding more to isolate a potent strain and to enhance the production of rapamycin [11]. Current researches focus on elucidating the anti-cancer, cardiovascular, anti-diabetic and anti-neurodegenerative potencies of rapamycin [12].

The ability to interact with mTOR signalling is a major lead of rapamycin when compared to other currently available immunosuppressants. Similar to calcineurin inhibitors, rapamycin binds to FKBP12 protein and inhibits the interleukins and cytokines needed for the proliferation of T cells, but the mode of action was found to be different [13]. Calcineurin inhibitors associated with the calcium efflux pathway can induce various side effects such as diabetes, neurological problems and renal dysfunction, whereas, rapamycin-fkbp12 complex directly binds to mTOR and inhibits the proliferation of IL-2 and other signalling molecules essential for T and B cells proliferation and survival [14–16]. The major bioactive metabolites of S. hygroscopicus [4, 6, 17–39] are highlighted in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Streptomyces hygroscopicus producing metabolites

| SI.no | Compound | Class | Bioactivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chitinase and beta-1,3- glucanase | Glcosyl hydrolase family 1 | Antagonistic activity Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Sclerotium rolfsii | [17] |

| 2 | Ascomycin | Immunomycin | Antifungal | [18] |

| 3 | Elaiophylin | Autophagy inhibitors | Antibiotic inhibiting testosterone 5-reductase | [19] |

| 4 | Anti-helmintics | Macrocyclic lactone antibiotic | Inhibitory activity against a broad spectrum of nematodes | [20] |

| 5 | Hygrocin A and B | Naphthoquinone macrolides (anti-fungal, bacterial, parasitic, cancer, viral, bacteriophage, tuberculosis) | Inhibiting polypeptide synthesis | [21] |

| 6 | Nigericin | Polyether antibiotics | Anti-cancer and anti-malarial activity | [22] |

| 7 | S632A3 | Glutarimide antibiotic | Inhibitory activity against Saccharomyces sp. | [23] |

| 8 | Pterocidin | δ-lactone terminus | Anti-cancer activity | [4] |

| 9 | Geldanamycin | Aminoglycosides | Inhibitors of ATP synthesis | [22] |

| 10 | Carriomycin, | Polyether antibiotic | Active against Gram-positive bacteria, several fungi, yeasts and Mycoplasma | |

| 11 | Nocardamine | Siderophore synthetase super-family | Inhibits M. smegmatis and M. bovis biofilm formation | [24] |

| 12 | Mannopeptimycins | Cyclic glycopeptide antibiotics | Against methicillin-resistant Staphylococci and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci | [26, 27] |

| 13 | Scopafungin | Lipopeptide anti-fungal | Inhibit pathogenic fungi, yeasts, and Gram-positive bacteria. | [28] |

| 14 | Neocopiamycin B | Macro cyclic lactone antibody | Anti-fungal activity | [29] |

| 15 | Psicofuranine | Adenosine analog. Anti-neoplastic and antibiotic agent. | Anti-bacterial activity | [30] |

| 16 | Herbimycin | Benzoquinone ansamycin antibiotic | Potent herbicidal activity against most mono- and di-cotyledonous plants | [31] |

| 17 | Leuseramycin | Polyether antibiotic | Anti-fungal activity | [32] |

| 18 | Demalonylcopiamycin | Macrolide antibiotic | Anti-bacterial activity | [33] |

| 19 | Pentalenolactone I | Sesquiterpene | Immunosuppressant | [34] |

| 20 | Hygromycin | Aminoglycoside | Anti-bacterial, Immunosuppressant | [35] |

| 21 | Hydantocidin | Spironucleosides. | Herbicidal activity | [36] |

| 22 | Trialaphos | Organophosphate’s pesticides | Antibiotic | [37] |

| 23 | Gopalamycin | Polyether antibiotic | Anti-fungal activity against Brown rust | [38] |

| 24 | Validamycin | Aminocyclitol antibiotics | Antifungal and antibacterial against Brown rust activity | [39] |

| 25 | Bialaphos | Acetyltransferase | Inhibits glutamine synthetase | [6] |

Streptomyces hygroscopicus: genetics

Streptomyces hygroscopicus displays a complex life cycle with a 10,1458,33 bp long two linear DNA with 71.9% G + C content. The genome contains 8,849 coding sequences with an average length of 952bps. Six rRNAs and sixty-eight tRNAs were reported in Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Both the ends of linear genome are protected by telomere like 14 bp long Terminal Inverted Repeats (TIR), which is the shortest discovered TIRs in Actinomycetes till date [40–42]. Streptomyces genome is highly inconstant and carries very large deletion prone areas [43].These deletion prone area in Streptomyces hygroscopicus genome ranges from 240 to 2150 kb. Mostly, the frequent deletions take place in the AseI sites (ATTAAT) on the chromosome [43]. Study on genomics of Streptomyces hygroscopicus 5008, discovered 29 gene clusters involved in the production of validamycin [42]. pSHJG1 with a length of 164,564 bp and pSHJG2 with a length of 73,285 bp were the two plasmids isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus 5008 [41].

Rapamycin biosynthetic gene clusters

The core structure of rapamycin was derived by the extension of (4R,5R)-4,5-dihydroxycyclohexa-1,5-dienecarboxylic acid by polyketide synthase (PKS). Type 1 polyketide synthase facilitated the biosynthesis of rapamycin [44]. Rapamycin-PKS was 107.3 kb long accommodating rapA, rapB and rapC open reading frames. These gene clusters encoded multienzymes RAPS1 (900 kDa), RAPS2 (1.07 MDa) and RAPS3 (660 kDa) [45, 46]. Between these genes was rapP situated, which coded for the pipecolate-incorporating enzyme. In addition, 22 genes were identified on both sides of this 3 ORF. Among the additional genes, several genes encoded the enzymes required for biosynthesis of rapamycin. Genes rapJ, rapN, rapO, rapI, rapM, rapQ and rapL were included in the addition set of gene clusters. Genes rapJ and rapN encoded two cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases (P450s), rapO coded for the production of associated ferredoxin (Fd) and rapI, rapM, rapQ produce the three potential SAM-dependent O-methyltransferases (MTases). The product of these genes acted as tailoring enzymes for pre-rapamycin [47]. Rapamycin biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces hygroscopicus, its products and functions are specified in Table 2. Cyclodeaminases coded by rapL gene converted L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid [47]. Products of positive regulatory genes rapH and rapG enhanced the promoter region of rapA and rapB. In a recent study, the over expression of rapH and rapG enhanced the production of rapamycin and deletion of both these genes resulted in complete down regulation of rapamycin production. Complementation studies revealed that rapG regulated the rapamycin core genes and rapH possessed a supportive role [48]. Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) was coded by rapP, which facilitated the attachment of L-pipecolic acid to the linear structure of pre-rapamycin [47].

Table 2.

Streptomyces hygroscopicus rapamycin biosynthetic gene function

| Rapamycin Gene | Product | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| rapA | Rapamycin Polyketide Synthase 1(RAPS1) | Initiation and extension of polyketide chain | [44, 45] |

| rapB | Rapamycin Polyketide Synthase 2(RAPS2) | Elongation of the polyketide chain | [44, 45] |

| rapC | Rapamycin Polyketide Synthase 3(RAPS3) | Termination of polyketide chain | [44, 45] |

| rapJ | cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases (P450s) | Link Carboxyl group at C9 position | [48] |

| rapN | cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases (P450s) | Link hydroxyl group at C27 position | [44, 45] |

| rapO | Ferredoxin | Required for the catalytic activity of P450s | [46] |

| rapI | SAM-dependent O-methyltransferases (MTases) | Modify the C39 site by O-methylation | [45] |

| rapM | SAM-dependent O-methyltransferases (MTases) | Modify the C16 site by O-methylation | [45] |

| rapQ | SAM-dependent O-methyltransferases (MTases) | Modify the C27 site by O-methylation | [45] |

| rapL | Cyclodeaminases | Convert L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid. | [45] |

| rapG | Unknown | Regulate rapamycine core genes | [45] |

| rapH | Unknown | Supportive role in the enhancement of core ORF sites | [45] |

| rapP | RapP(160 kDa) is a Nonribosmal peptide synthetase (NRPS) | Convert the linear structure of pre-rapamycin to cyclic by attaching pipecolic acid. | [46] |

| rapK | Code for the production of chorismatase | Convert chorismite to 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid | [53] |

Biosynthesis of rapamycin

Shikimate pathway

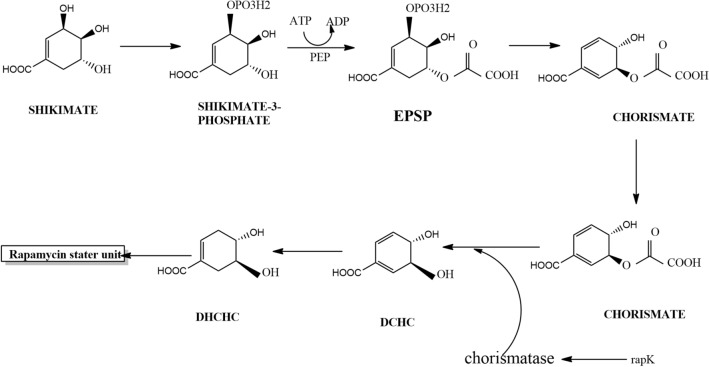

Shikimic pathway in microorganisms produces aromatic bioactive compounds, but in some scenario the aromatic shikimic acid will be converted to non-aromatic compounds. It can act as a precursor for the biosynthesis of various biologically beneficial metabolites like cyclohexanecarboxylic (CHC) acid and dihydroxycyclohexanecarboxylic (DHCHC) [49]. (1R,3R,4R)-3,4 Dihydroxycyclohexanecarboxylic (DHCHC) was found to be the pioneer unit for the biosynthesis of rapamycin which was derived from shikimic acid [50, 51]. DHCHC was also reported to be involved in the biosynthesis of ascomycin and tacrolimus (FK506) [51]. Phosphoenol pyruvate and erythrose-4-phospate were used as substrates for shikimate pathway to synthesize chorismate [52]. The first enzyme in the shikimate pathway was DAHP which was encoded by dahp gene in Streptomyces hygroscopicus. The co-expression of dahp and rapK promoted enhanced production of rapamycin [10]. rapK gene present in the rapamycin gene cluster codes for chorismatase which hydrolysised chorismate and produced 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid [53]. RapK was first considered as a putative pteridine-dependent dioxygenase that can act at the C9 in rapamycin, but later the importance of rapK gene was studied. Deletion of rapK gene completely inhibited the production of 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid and abolished the biosynthesis of rapamycin [54]. Figure 1 illustrates the formation of 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid by Shikimate pathway.

Fig. 1.

4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid biosynthesis through shikimate pathway. rapK gene code for chorismatase convert chorismite to DCHC. (EPSP: 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate, DCHC: (4R,5R)-4,5-dihydroxycyclohexa-1,5-dienecarboxylic acid), DCHC: 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid)

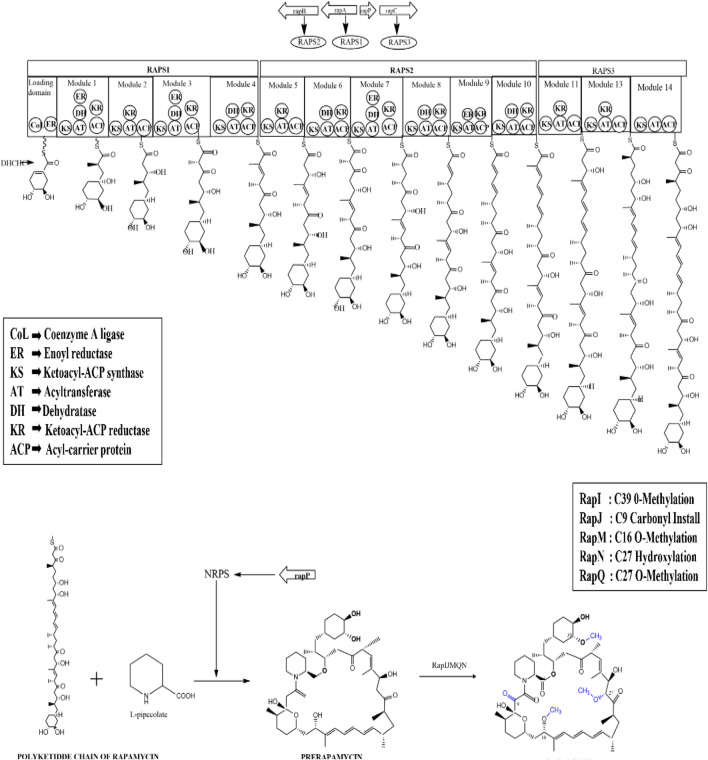

Biosynthesis of rapamycin polyketide chain

RAPS1 carried four modules for the initiation and extension of polyketide chain. RAPS2 consisted of six modules for chain elongation and the last four modules were present in RAPS3 for termination of polyketide chain [45]. The three giant parts of polyketide synthase contained 14 separate sets and each module carried out the extension of polyketide chain. The acyl-carrier protein (ACP), β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KS) and acyltransferase (AT) domains were the core groups, and enoyl reductase (ER), β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (KR) and dehydratase (DH) were the enzymatic groups contained in the modules of polyketide synthase. 4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid starter unit was attached to the CL domain of the chain by a novel ligase enzyme in the N terminus of RAPS1. ER actively modified the starter unit after attachment [55]. Figure 2 represents the biosynthetic pathway of rapamycin production.

Fig. 2.

Biosynthesis of rapamycin. This picture illustrates the biosynthesis of rapamycin linear polyketide chain and the convention of linear chain to circular pre rapamycin. Post tailoring genes convert prerapamycin to rapamycin

The biosynthesis of rapamycin was initiated by the attachment of ATP dependent DHCHC to the loading domain in the N terminus which carried coenzyme A ligase (CL), ER and ACP domains. CoA ligase helped in the activation of starter unit. The activated DHCHC was transferred to the β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthase domain of RAPS1 [45, 46, 56]. After linking with RAPS1, the enoyl reductase domain reduced the cyclohexane ring of the activated DHCHC [55]. Either (2 S)-malonyl-CoA or (2 S)-methylmalonyl-CoA was attached to the starter unit by the modules of polyketide synthase enzyme, which resulted in the formation of macrolactone ring [47, 77]. β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase, acyltransferase, ACP, auxiliary β-keto processing domains, ketoreductase, dehydratase and enoyl reductase present in each modules facilitated the elongation of polyketide chain [47].

Rapamycin polyketide chain termination and cyclization was marked by linking the pipecolate acid to the terminal end of the linear chain. The gene rapL coded for Cyclodeaminase enzyme facilitated the cyclodeamination reaction of L-lysine and resulted in the biosynthesis of precursor L-pipecolate. The linear rapamycin polyketide chain exhibited a thioester linkage between RAPS3 and transferred the chain that was bound covalently to pipecolic moiety [48, 55, 57]. Linkage of the synthesized polypeptide linear chain with pipecolate was aided by rapP gene which coded for RapP enzyme. RapP(160 kDa) was a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) composed of 1542 amino acids organized in four domains. Pipecolate attached to the terminal end of the polyketide chain was linked to the C-34 hydroxyl group of the chain that composed the macrolactam ring of the pre-rapamycin [46, 47].

Modification of pre-rapamycin macrocyclic core ring

The genes rapM, rapQ, rapI, rapJ, rapN and rapO translated the post tailoring enzymes that modified the pre-rapamycin structure. O methylation and oxidation were considered as the last steps in the conversion of the 31-membered pre-rapamycin lactone ring to rapamycin. SAM-dependent O-methyltransferase (MTase), Rapl modified the C39 region of hydroxyl group and catalysed the methylation process. RapM was the second SAM-dependent O-methyltransferase (MTase) which O-methylated the C16 region of pre-rapamycin. Cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase RapJ linked a carbonyl group to the C9 region and Rap N Cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase added a hydroxyl group at C27, followed by the addition of methyl group at C27 region by SAM-dependent O-methyltransferase RapQ. The overall modification yielded active rapamycin. Ferredoxin required for the cytochrome P450 enzyme activity was translated by rapO [47, 54, 55].

Mechanism of action of rapamycin

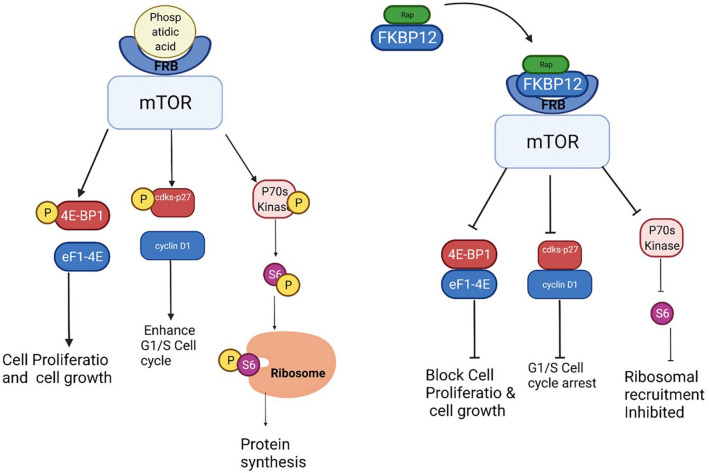

mTOR, a Ser/Thr kinase has been identified as a key regulator of different pathways. It was reported to have a significant role in cell proliferation, survival metabolism, cell growth and angiogenesis. mTOR was found to belong to the family of phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases (PIKKs) which regulated various cellular signalling [58]. mTOR1 and mTOR2 were the two complexes of mTOR, having distinct functions [59–61]. mTOR1 was sensitive to rapamycin whereas mTOR2 was insensitive, but prolonged administration of rapamycin indirectly affected the mTOR2 complex [62]. Dysfunction in mTOR signalling led to various disease conditions like tumor formation, arthritis, insulin resistance and osteoporosis [63]. Ribosomal biogenesis, cellular response to hypoxia, protein translation, glucose, lipid and nucleotide metabolism, and cell growth promotion were the major events carried out by mTOR1, whereas, mTOR2 regulated the cell proliferation and survival mechanisms by phosphorylating different protein kinases included in the family of AGC [59].

Rapamycin was found to be capable of binding to the hydrophobic binding pockets of cytosol protein FKBP12, thereby forming a dimer. Further, it was found to bind to the serine kinase region of FKBP12-Rapamycin Binding domain (FRB) present in mTOR1 [64, 65]. FRB, the binding site for phosphatidic acid positively regulated the mTOR1 pathway while, FKBP12-rapamycin complex bound to FRB resulted in negative regulation of mTOR1 [66]. Another study reported the potency of rapamycin to discretely bind to FRB with the help of small binding molecules, but with a lower affinity [66]. FRB attracted the FKBP12-Rapamycin dimer complex towards it and this complex induced down-regulation of 4E binding protein-1 (4E-BP1) and the 40 S ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70s6k) [67–69]. 4E-BP1 was a negative repressor associated with initiation factor eIF4E that blocked the activation of eF1-4E [70, 71]. When mTOR was activated, it phosphorylated 4E-BP1 which led to the disassociation of 4E-BP/eIF4e complex and increased the availability of free eIF4e. Free eIF4e associated with any of eIF-4G, -4B, or -4 A formed a multi-subunit complex with eIF-4 F. This led to the translation of mRNA for the enhancement of cell cycle and cell proliferation [69–71]. While FKBP12-Rapamycin complex bound to the FRB site of mTOR inactivated the system and kept 4E-BP1 dephosphorylated, it also decreased the availability of free eIF4e. This resulted in the suppression of mRNA translation for cell cycle metabolism [72, 73].

Rapamycin was found to induce cell cycle arrest by down regulating the Ser/Thr protein kinase P70S6K essential for G1 cell cycle progression. PI3K/Akt transduction pathway stimulated mTOR, which led to the phosphorylation and activation of P70S6K. Phosphorylated P70S6K recruited 40 S ribosomal subunit by phosphorylating S6 ribosomal protein. This activation enhanced the translation of ribosomal proteins, elongation factors, and insulin growth factor–II needed for cell proliferation and survival metabolism. In contrast, rapamycin complex inactivated the mTOR signalling pathway by dephosphorylating the Ser/Thr protein kinase, P70S6K, that led to cell cycle arrest [74–76] (Fig. 3).Inactivation of 4E-BP1 led to the suppression of translation of cyclin D1 mRNA and induced a deficiency of cdk4/cyclin D1 complexes. In addition, Rapamycin enhanced the formation of cyclin/cdks-p27 complex by suppressing the escape of the complex. It also enhanced the formation of cdks27 inhibitor which led to cell cycle arrest at G1/S transition and blocked the production of IL-2 and other cytokines essential for T cells proliferation [76–79]. In rapamycin treated cells, thymidine absorption was reduced to about 50–70%, indicating that rapamycin slowed down the cell proliferation instead of complete inhibition [79].

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of action of rapamycin. This picture illustrates the interaction of rapamycin-FKBP12 complex with FRB domain in the mTOR. This interaction dephosphorylates 4E-BP1, cdks-p27 and P70s kinase and clock cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest and inhibit ribosomal recruitment

Pharmaceutical significance of rapamycin

Rapamycin as an immunosuppressant

Initially, rapamycin was considered as a macro lactone antifungal antibiotic. After the discovery of structurally similar macro lactone immunosuppressant FK506 (tricolimus), rapamycin was identified as an immunosuppressant. Both rapamycin and tricolimus can selectively inhibit the proliferation of T-lymphocytes [80]. The pipecolate moiety present in the macrolactone ring of both FK506 and rapamycin binds to the cellular receptor - FKBP12, for the inhibition of T-cell proliferation. But both of these possess different modes of action [81–83]. FK506 and cyclosporine was found to form a complex with FKBP12 that inhibited calcium-calmodulin dependent protein phosphatase [83, 84]. FK506-FKBP12 complex inhibited the activity of calcineurin due to transcriptional and translocational inactivation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). NFAT was observed to take part in the activation of IL-2 genes which were necessary for the activation and proliferation of T cells [84, 85]. Rapamycin-FKBP12 complex blocked the T cell proliferation by interacting with mTOR This complex inhibited the translation of 15–20% of proteins by inducing G1/S phase cell cycle arrest [82]. Administration of calcineurin drugs induces neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. No neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity were observed in patients administrated with rapamycin. This was found to be one of the major advantages of rapamycin therapy over calcineurin drugs [83, 86, 87]. FK506 inhibited the calcineurin phosphatase which resulted in renal vasoconstriction and enhanced the production of multiple cytokines which induced nephrotoxicity [88]. Administration of low concentrations of calcineurin inhibitors in combination with rapamycin was reported to be effective over monotherapy as it could impede graft rejection [87].

Rapamycin was considered as a strong immunosuppressant and anti-rejection drug after organ transplantation [89]. Studies reported that rapamycin was capable of halting both acute and chronic organ rejections and were also able to reverse chronic graft rejection [90, 91]. Rapamycin blocked the T cell proliferation by arresting G1/S progression. It was found that rapamycin was not a specific inhibitor of IL-2 and IL-4, and that it could also inhibit the actions of B cells, IL-3, IL-4, mast cells, lymphoid tumor cells, hepatocytes and fibroblasts [92]. Studies documented that very low concentrations of rapamycin was required to inhibit the IgG immunoglobulin (IC50 = 0.3 nM-2 nM) when compared to cyclosporine (IC50 = 0.3 microM-2 microM) [93, 94].

Rapamycin was used in kidney, skin, heart, pancreas and small bowel transplants for preventing the allograft rejection [88]. A study in porcine renal allograft model documented that rapamycin as a potent immunosuppressant in renal transplantation surgery. Also, a low serum creatinine level was observed upon administration of rapamycin in contrast to higher levels of serum creatinine detected upon usage of FK506 and cyclosporine. Alanine transaminase levels (ATL) were elevated upon administration of higher doses of rapamycin in porcine models which decreased to normal within 2 to 4 weeks after completing the treatment period [95, 96]. Improved organ function at later stages was observed upon treatment with a combination of sirolimus with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) after renal transplantation [97].

Rapamycin can be called one among the most effective immunosuppressants which can downturn cardiac vasculopathy [98]. Use of calcineurin inhibitors could be the leading reason for renal dysfunction in cardiac transplant patients. Replacement of calcineurin inhibitors with rapamycin was found to reduce renal dysfunction aiding in normal cardiac functions [99]. Prolonged use of calcineurin inhibitors in heart transplant patients showed calcineurin inhibitor induced renal impairments, but shifting to rapamycin regained normal renal functions [100, 101]. Rapamycin was suggested as a surrogate for lung transplanted patients suffering from calcineurin inhibitors induced toxicity [102]. Rapamycin was also found to be a practical in-vivo drug for refining pulmonary functions in lung allografted recipients suffering from bronchiolitis obliterans (BOS) [103].

Rapamycin for autoimmune diseases

Recently rapamycin has been used as an immuno modulator against certain autoimmune diseases [104]. It was proved that rapamycin can be used against autoimmune rheumatic disease. The effect of Sirolimus was studied against systemic lupus erythematosus and found to be effective in monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressants. Skin rashes, arthritis and thrombocytopenia were reduced in systemic lupus erythematosus patients treated with rapamycin [105]. Auto reactive CD4 T cells play a significant role in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rapamycin regulates the CD4 cell metabolism through the dual inhibition of glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism [106]. It was found to be one of the effective target for the treatment of SLE. Rapamycin rectified the dysfunction of CD4 T cells and reversed the effect of systemic lupus erythematosus [106].

Spondyloarthritis Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (SpA PBMCs) secreted the inflammatory cytokines which caused SpA fibroblast-like synoviocytes and osteogenesis. mTOR activation amplified the secretion of IL-17 A and TNFα which enhanced the activation of SpA fibroblast-like synoviocytes and induced osteogenesis in humans [110, 111]. mTOR pathway was found to regulate the cell proliferation and bone metabolism. It was found that rheumatic arthritis could be controlled by targeting the mTOR pathway [111]. Rheumatic arthritis is characterized by the damage of bone and cartilage tissues in joints and synovial membranes resulting in inflammatory pain and stiffness. Steroids and immunosuppressant were normally used for the treatment of rheumatic arthritis [107–109]. It was found that rapamycin administered mouse showed reduced amounts of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IL‑1β responsible for rheumatic arthritis [109]. Another significant finding was that rapamycin interacted with mTOR1 complex and inhibited the secretion of IL-17 A and TNFα by the peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Thus terminating the differentiation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in spondyloarthritis patients [112]. A 21-year-old renal transplant recipient administered with FK506 and steroid drugs developed juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. As an alternate, rapamycin was administered to the renal transplant patients. It showed significant reduction in inflammation [112]. Thus, rapamycin was found to be an effective alternative drug of choice against autoimmune diseases.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are sub-populations of T cells specified to regulate the immune response. Treg cells prevents the autoimmune condition by impeding the production of T cells and cytokines. FOXP3 was identified as a transcription factor of regulatory T cells. Mutation in foxp3 gene led to dysfunction of regulatory T cells, which resulted in severe autoimmune diseases [113– 115]. Immuno-dysregulation, poly-endocrinopathy, enteropathy and X-linked syndromes were the major autoimmune diseases caused due to the dysfunction of FOXP3 [115, 116]. FOXP3 regulated the production of adenosine deaminase through C39 pathway. Adenosine deaminase controlled the production of Ruxn1 which positively enhanced the secretion of FOXP3. Rapamycin favoured the expression of CD39/Runx1 pathway. In the presence of rapamycin, adenosine deaminase and Runx1 expressions were enhanced, which positively regulated the production of FOXP3, ultimately elevating the production of regulatory T cells. Recent studies documented that rapamycin selectively enhanced the proliferation of Treg cells in non-human primate models. It can be used to cure graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [117–119].

Rapamycin against cancer

mTOR pathway regulates the expression of many oncogenes like PI3K, Akt, and eIF4E. Different types of tumor cells showed hyper activity of mTOR pathway which resulted in activation of these oncogenes. The two mTOR complex, mTOR complex 1 modulate cell growth and metabolism while survival and cell proliferation is modulated by mTOR complex 2. Hence, an effective way to suppress tumor is by inducing the suppression of mTOR pathway. Many studies reported rapamycin as a powerful drug against mTOR activation. Different studies proved the efficiency of rapamycin as an anticancer drug. Rapamycin slowed the proliferation of tumor cells, inducing apoptosis and impeding angiogenesis in tumor cells. Rapamycin suppressed tumor by inhibiting mTOR and causing cell cycle arrest [61, 120–122].

Rapamycin is an approved anti-cancer drug to treat renal cancer. VEGF-A and TGF-beta1 promoted angiogenesis in renal cancer patients. Treatment with rapamycin turned down the amount of VEGF-A and TGF-beta1 [122, 123]. Rapamycin reduced the metastatic tumor growth in mouse and was also found to be effective against pancreatic cancer. Rapamycin, along with anti-VEGF antibody, showed better activity against pancreatic cancer and liver metastasis. The drug combination also inhibited tumor angiogenesis [123, 124]. Rapamycin inhibited pancreatic cancer via four different mechanisms: dephosphorylation and inhibition of p70s6K and 4E-BP-1 activity, hindering DNA synthesis and suppression of anchorage-dependent and -independent proliferation, masking the cyclin D1 expression and inhibition of serum induced proliferation of cancer cells [125, 126]. In a recent study, rapamycin was found to induce apoptosis by blocking the insulin-like growth factor-I-mediated cell growth. It was also stated that administration of rapamycin could restrict the metastatic promotion of lung cancer cells via reduction of VEGF [126].

Rapamycin against ageing and age-related diseases

Aging is the process of gentle reduction in the biological functioning of tissues and organs in an organism Aging of a cell leads to dysfunction of normal biological activities like protein synthesis, ribosomal synthesis, glucose metabolism, autophagy, lipid metabolism, cell growth, development and transcriptional metabolism. The mTOR is the key nutrient sensing regulator of aging [127–129]. Different studies showed that TOR mutation increased the life span of Caenorhabditis elegans, yeast and Drosophila [130]. Currently rapamycin is the only known pharmacological agent used to increase the life span in male and female model organisms by inhibiting the TOR1 complexes [131, 132] .

Initially, it was believed that anti-aging manipulations should be done at the early stages of life to increase the life span of an organism. Administration of rapamycin in 19 months old mice showed an increased life span, proved for the first time that anti-aging treatment can be effectively implemented at later stages of life. Studies conducted in three different age groups of mice ( 4 months, 9 months and 19 months) demonstrated increased life span in similar rates [133–136]. Larger concentrations of rapamycin was detected in female mice when compared to male mice administered with equal concentration of the drug, substantiating its longer life span [136].

Effect of rapamycin on hutchinson-gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS)

Progeria is a strange autosomal dominant genetic disorder leading to premature ageing. Mutation at a specific site of LMNA gene resulted in the accumulation of mutated lamin A called Progerin. Accumulation of progerin in nuclear membrane resulted in the dysfunction in dynamic movement of nuclear lamin polymers and changed the normal morphology of nuclear membrane. It also induced mitotic abnormalities and increased the rate of telomere shortening. The phenotypical and genotypical disorders due to progeria resulted in premature death of an individual at an early age of 15 [137–140]. Progeria was first discovered in 1886 and it took more than 100 years to discover a medicine against the disease. In 2020 the first and only medicine named lonafarnib was discovered and approved by the FDA for treatment of progeria [139].

Rapamycin is used as a drug for autoimmune diseases, cancer and many other disorders. Recently, administration of rapamycin to progerial mice models cured cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders that developed as a result of progeria. The test organism also recovered from atherosclerosis. Rapamycin’s potency to induce autophagy is the key to treat Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome [140, 141]. Recent research findings illustrated a decline in the concentration of progerin upon treatment with rapamycin via the induction of autophagy and showed restored fibroblast morphology [142]. In a study conducted by John et al. in 2012 [140], the mechanism of rapamycin mediated autophagic denaturation of progerin was demonstrated. It was found that K63-linked poly-Ub chains promoted the ubiquitination of progerin. Further it was observed that the mutated Lamin A protein co-immunoprecipitated with autophagy adaptor protein p62 and resulted in the clearance of progerin. In the presence of rapamycin, the colonization of progerin with both p62 and autophagy linked proteins: FYVE and ALFY. These observations stated that p62, FYVE and ALFY were the main components that facilitated the clearance of progerin in the presence of rapamycin [141].

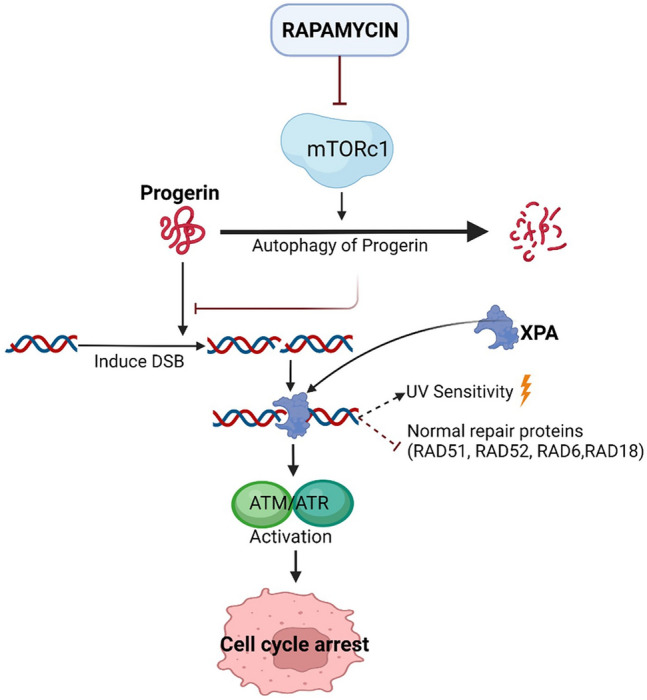

Progerin induced pseudo–DNA damage response resulted in telomere shortening and dysfunction. Telomere shortening, in turn, resulted in geroconversion, which is the most common reason for development of age related disorders [142]. In Lamin A mutated cells, accumulation of progerin resulted in double stranded DNA breaks (DSB). Also, these cells exhibited a nuclear site for an excision repair protein called XPA (Xeroderma Pigmentosum type A) protein, due to which XPA protein binds to the DSBs as the foci for XPA is co-localized with the DSB region. The XPA-DSB interaction prevented the recruitment and binding of normal DSB repair proteins such as RAD52, RAD51, RAD6 and RAD18 proteins. It also facilitated the induction of ATM/ATR pathways eventually promoting permanent irreversible cell cycle arrest. In progerian cells, the accumulation of XPA showed elevated sensitivity towards UV radiations [143–147]. Administration of rapamycin enhanced the autophagic degeneration of progerin protein, delaying the entire process of cell cycle arrest [142]. Figure 4 represents the mechanism of action of rapamycin against progeria.

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of action of rapamycin against progeria. Accumulation of progerin eventually results in the cell cycle arrest. Rapamycin interaction enhanced the autophagy and cleared the accumulation of progerin

Effect of rapamycin on neurodegenerative disease

Recent studies proved the neuroprotective potency of rapamycin. Dysfunction of mTOR regulated pathways like lysozyme-autophagy, mitochondria-dependent apoptosis, cap-independent translation of pro-survival factors and cap-dependent translation of pro-cell death proteins were considered as the reason for neurogenerative disease like Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Administration of rapamycin aided in regulation of mTOR pathway and prevented neurodegeneration [148].

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease caused due to the deposition of plaques formed by intracellular neurofibrillary tangles and extracellular amyloidal protein activities. Due to this, the interactions between nerve cells were blocked and resulted in dementia [149]. Defect in the autophagy-lysosome pathway played a significant role in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease [150]. Application of mTOR inhibitors like rapamycin positively induced autophagy and was reported as a potent pharmacological drug for the treating Alzheimer’s disease. Study conducted in mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease (AD-Tg) concluded that administration of rapamycin improved memory and showed reduction in anxiety and depression [151].

In 2020, Ai-Ling Lin et al. [152] conducted a study to find the response of rapamycin in mice that express human APOE4 gene and overexpress Aβ. There studies indicated that rapamycin were successfully restored the normal brain function [152]. Recently it was found that rapamycin induced the mitophagy to clear the cognitive and synaptic plasticity defects of Alzheimer’s disease. It also increased the synaptic plasticity, and the expression of synapse-related proteins, impedes cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis. Rapamycin decreased the oxidative stress and protects hippocampus neurons from adverse effect of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease can induce the neurovascular coupling. Recently it was found that rapamycin has the ability to decrease the neurovascular coupling in mouse model [153–155]. These recent studies substantiate the benefits of rapamycin against Alzheimer’s disease and it could be really beneficial to do the human trials to use rapamycin as a drug against Alzheimer’s disease.

Parkinson disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder that affects the proper locomotion of an individual [156, 157]. Decrease in the levels of dopamine and agglomeration of Lewy bodies, composed of α-synuclein, resulted in Parkinson disease [158]. It was found that accumulation of α-synuclein enhanced the overexpression of mTOR pathway which led to decline in autophagy [159, 160]. Different studies were conducted to disclose the therapeutic effect of rapamycin against Parkinson’s disease, substantiated the ability of rapamycin to trigger autophagy and increase the dopamine levels [161]. These evidences designate the potential of rapamycin to be used as a therapeutical drug against Parkinson Disease.

Anti-viral property of rapamycin

Recent research illustrated that viral infections led to over expression of mTORC1 which, in turn, facilitated the activation of viral protein synthesis and cell cycle proliferation in the host cells [162–164]. It was found that, zika virus infection resulted in the over expression of both mTORC1 and mTORC2. Zika virus protein expression and progeny production was reduced by the inhibition of mTOR kinase using rapamycin [162, 163]. Different studies conducted on the effect of mTOR inhibitors over viral infections stated that rapamycin blocked the synthesis of viral proteins and enhanced immune response [164–166].

mTOR complex inhibitors are found to be a successful antiviral agent. By computational docking, it was found that rapamycin had a greater binding affinity of -11.87 k cal/mol towards the N protein. N protein is present in the C Terminal Domain of Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [167]. RdRp enzyme is the most conserved enzyme in the RNA virus, which catalyze the replication of RNA from RNA template. SARS-CoV-2 has the same RdRp enzyme for RNA replication. In an in vivo study conducted by Pokhrel [168] and his team found that rapamycin was one among the top three compound against RdPp. Rapamycin has the ability to inhibit the proliferation of IL-2, IL-6 and IL-10. Recently, during pandemic, rapamycin was used to control the cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients [169]. A 13 year old renal transplant patient was recovered from COVID-19 after 4 days of rapamycin therapy [170]. Matteo [171] mentioned that rapamycin can decrease the mortality rate in Covid-19 patients with β‑thalassemia.

In 2017, Kumar [172] conducted a study to discover the significance of mTOR inhibitors on HIV. It was found that mTORC1 inhibition interrupted the glycosylation of viral envelop proteins. Specific mTORC1 inhibition blocked viral reactivation and replication. The CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) was found to be the co-receptor for HIV [173]. Two different studies were conducted by Heredia [174] to examine the effect of rapamycin on CCR5 receptors. The results of the study revealed that the administration of rapamycin specifically reduced the surface expression of CCR5 on T cells and macrophages. Further they also found that rapamycin administration inhibited the replication of CCR5 tropic strains of HIV-1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and macrophages [175]. These data also substantiate the possibilities of using rapamycin as a potential drug against Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Advancements in rapamycin production

The amount of rapamycin produced by streptomyces hygroscopicus is very less to meet the demand of the current world. To enhance the production of rapamycin, various physical, chemical and biological methods are instigated. Authentic media optimization studies facilitated the researchers and industrialist to design new media components to enhance the production of rapamycin. Soya, tyrosin, ammonium sulphate are important compounds for the enhanced production of rapamycin. Trace metals, cobalt chloride, zinc sulphate and ferric chloride induced the production of rapamycin.

Rap L is responsible for the conversion of L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid by cyclodeamination. Addition of lysin stimulated the production of rapamycin by 150% [176]. L-pipecolic acid formed from L-Lysin is a major compound in the structure of rapamycin. Supplementation of lysin in the medium increased the amount of freely available L-pipecolic acid. This might be the reason for the increased production of rapamycin. It was found that nano particle sized soya, 1% NaCl and glycerol enhanced the production and compounds like CaCo3 reduced the synthesis of rapamycin [177, 178].

Genetic engineering is one of the key methods to increase the production of desired compound. Apart from media optimization studies, strain improvements influenced the rate of rapamycin production. N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitroso guanidine (NTG) induced mutation in MTCC 5681 strain enhanced the production of rapamycin [179]. Protoplast shuffling was found to be a significant method to increase the yield of rapamycin. As mentioned previously in Sect. 2.1, that over expression of rapH and rapG increased the production of rapamycin. Recently, it was observed that overexpression of rapK gene enhanced the synthesis of chorismatase and increased the availability of the starter unit (4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid). Increased amount of starter unit in the cell consistently increased the amount of rapamycin production [180].

Till date, researchers have focused on modifying the rapamycin polyketide genes in order to increase the production of rapamycin. The enhancement of associated pathways such as the shikimic acid pathway may increase the yield of rapamycin. In addition, another option for enhancing the production of rapamycin is to delete the ascomycin polyketide genes. As both ascomycin and rapamycin share similar starter unit (4,5-dihydroxycyclohex-1-enecarboxylic acid), deletion of ascomycin genes may enhance the availability of the starter unit, thereby increasing the production of rapamycin. However extensive research is mandatory to prove the importance of shikimic acid in the production of rapamycin.

Rapamycin derivatives

The derivative of a bioactive compound can be synthesized by addition, deletion or by replacing a functional group from the parental structure of a drug. Derivative of a compound can be achieved by either manipulating the metabolic pathways or specific genes. To synthesize a novel rapamycin derivative, Frank [181] designed an L-pipecolate minimal media. The medium was supplemented with L-pipecolate analog, nipecotic acid to synthesize two sulfur containing rapamycin analogues [20-thiarapamycin and 15-deoxo-19-sulfoxylrapamycin]. Nipecotic acid suppressed the biosynthesis of rapamycin. Ascomycin and tricolimus are structurally similar immunosuppressants. When compared to other structurally similar calcineurin inhibitors, the selective mode of action of rapamycin on mTOR reduced the adverse effects. To enhance the affinity of rapamycin to mTOR and to reduce the minimal side effects, researchers have focused on the derivatives of rapamycin. A comparative study on different derivatives of rapamycin aids in elucidating the drawbacks and side effects of existing rapamycin analogues. Also, it will be helpful in developing a new derivative with enhanced potential.

Everolimus is a 2-hydroxyethyl derivative of rapamycin. Everolimus is a second-generation derivative of rapamycin with a slight difference in the C-39 methylation and C-40 2 hydroxyethyl group regions in everolimus [182]. The major side effects of sirolimus are thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, edema and hypercholesterolemia are comparatively less in everolimus [183]. The 2-hydroxyethyl derivative of rapamycin have lesser half-life and 98% of the drug was metabolized in hepatocytes, whereas, only 91% of clearance occurs in case of rapamycin. Rapamycin was metabolized by CYP3A4 and everolimus was metabolized by CYP3A4, CYP2CA and CYP3A5 and both are substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp). In comparison both the drugs had difference in pharmacodynamics and widely using in heart and kidney transplanted patients as an immunosuppressant [184].

Temsirolimus is a 42-[3-hydroxy-2 (hydroxymethyl)-2- methylpropanoate] rapamycin used for the treatment of Renal cell carcinomas (RCC). C40 domain of rapamycin was modified to obtain everolimus and temsirolimus. Among the first-generation derivatives of rapamycin, temsirolimus has the least terminal half-life ranging from 9 to 27 h. 82% of the drug was eliminated through feces and about 5% through urine. It was involved in drug-drug interaction with CYP3A4 but unlike rapamycin P-gp was not a substrate for temsirolimus [183, 185]. Currently, everolimus is used as an immunosuppressant and temsirolimus against RCC.

Biolimus A9 also known as urolimus is derived from rapamycin by modifying the C40 region with alkoxy-alkyl group [186]. Biolimus is an anti-proliferative drug to coat the biodegradable eluting sent for the treatment of cardiovascular disorders. Everolimus and sirolimus mediate the cell death by ROS activation. Rather than ROS mode of inhibition biolimus inhibit the ULK1 in VSMCs and promote stronger cell cycle arrest [187].

Everolimus, temsirolimus and biolimus are the important derivatives of rapamycin. C40 region is altered in all the derivatives of rapamycin. Ridaforolimus –a rapamycin derivative is a kinase inhibitor of the mTOR. It was formulated by substituting the C40 region with phosphine oxide. This drug is used for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma [188]. Recently, phase III clinical trial was conducted to check the efficiency of this drug. Many other new rapamycin derivatives are synthesized and clinical trials are conducted by researchers and pharmaceutical companies.

Conclusion

This review reiterates the genetics of Streptomyces hygroscopicus and the versatile drug rapamycin. Since the discovery of rapamycin, many studies have been conducted to evaluate the potency and versatility of the drug. But still, it is an area of keen interest for researchers. In 2020, lonafarnib, the first FDA approved drug was introduced for the treatment of progeria. Recent research reports evidenced the application of rapamycin for the treatment of progeria. This unlocks up the likelihoods to a new realm of research. Here, we discussed the unique mechanism of action of rapamycin against viruses. The exact potency of rapamycin to target corona virus and its associated pathways could emerge as a saviour for COVID-19 patients. Effect of rapamycin and its combinations with other drugs on corona viral infection needs to be deliberated and targeted for future research. Biosynthetic mechanism of rapamycin by Streptomyces hygroscopicus illustrates the importance and specific functions of rapamycin genes. Currently existing Streptomyces hygroscopicus strains showed less production potency. The researchers and pharmaceutical industries fail to meet the exact requirement for rapamycin. Discovering the genetic makeup and mechanisms of rap core genes and associated putative genes provide opportunities for genetic alterations in the genome of the organism in order to enhance the biosynthesis of rapamycin.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Vellore Institute of Technology for the constant encouragement, help and support for extending necessary facilities.

Funding

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sanjeev K. Ganesh, Email: sanjeevkganesh246@gmail.com

C. Subathra Devi, Email: csubathradevi@vit.ac.in

References

- 1.Salwan R, Sharma V. Bioactive compounds of Streptomyces: biosynthesis to applications. Studies in natural products chemistry. Netherlands: Elsevier BV; 2020. pp. 467–491. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadhasivam S, Shanmugam P, Veerapandian M, Subbiah R, Yun K. Biogenic synthesis of multidimensional gold nanoparticles assisted by Streptomyces hygroscopicus and its electrochemical and antibacterial properties. Biometals. 2012;25:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9506-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Igarashi Y, Asano D, Furihata K, Oku N, Miyanaga S, Sakurai H, et al. Absolute configuration of pterocidin, a potent inhibitor of tumor cell invasion from a marine-derived Streptomyces. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:654–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.11.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igarashi Y, Miura SS, Fujita T, Furumai T. Pterocidin, a cytotoxic compound from the endophytic Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Antibiot. 2006;59:193–195. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Kim SG, Blenis J. Rapamycin: one drug, many effects. Cell Metab. 2014;4:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hara O, Murakami T, Imai S, Anzai H, Itoh R, Kumada Y. The bialaphos biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces viridochromogenes: cloning, heterospecific expression, and comparison with the genes of Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:351–359. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-2-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo YJ, Kim H, Park SR, Yoon YJ. An overview of rapamycin: from discovery to future perspectives. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;44:537–53. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1834-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vézina C. Rapamycin (Ay-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot. 1975;28:721–726. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chueh SCJ, Kahan BD. Clinical application of sirolimus in renal transplantation: an update. Transpl Int. 2005;18:261–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang L, Liu J, Wang C, Liu H, Wen J. Enhancement of rapamycin production by metabolic engineering in Streptomyces hygroscopicus based on genome-scale metabolic model. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;44:259–270. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patsenker E, Schneider V, Ledermann M, Saegesser H, Dorn C, Hellerbrand C. Potent antifibrotic activity of mTOR inhibitors sirolimus and everolimus but not of cyclosporine A and tacrolimus in experimental liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu ZN, Shen WH, Chen XY, Lin JP, Cen PL. A high-throughput method for screening of rapamycin-producing strains of Streptomyces hygroscopicus by cultivation in 96-well microtiter plates. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1135–1140. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-8463-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber KH, Arriola ASI, Yu D, Brinkman JA, Velarde MC, Syed FA. A novel rapamycin analog is highly selective for mTORC1 in-vivo. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fruman DA, Wood MA, Gjertson CK, Katz HR, Burakoff SJ, Bierer BE. FK506 binding protein 12 mediates sensitivity to both FK506 and rapamycin in murine mast cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:563–571. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raimondi AR, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS. Rapamycin prevents early onset of tumorigenesis in an oral-specific K-ras and p53 two-hit carcinogenesis model. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;69:4159–4166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunz J, Hall MN. Cyclosporin A, FK506 and rapamycin: more than just immunosuppression. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:334–338. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prapagdee B, Kuekulvong C, Mongkolsuk S. Antifungal potential of extracellular metabolites produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus against phytopathogenic fungi. Int J Biol Sci. 2008;4:330–337. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang P, Yin Y, Wang X, Wen J. Enhanced ascomycin production in Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. Ascomyceticus by employing polyhydroxybutyrate as an intracellular carbon reservoir and optimizing carbon addition. Microb Cell Factories. 2021;20:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01561-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima SMA. Characterization of the biochemical, physiological, and medicinal properties of Streptomyces hygroscopicus ACTMS-9H isolated from the Amazon (Brazil) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:711–723. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nonaka K, Tsukiyama T, Okamoio Y, Sato K, Kumasaka C, Yamamoto T, Maruyama F, Yoshikawa H. New milbemycins from Streptomyces hygroscopicus subsp. aureolacrimosus: fermentation, isolation and structure elucidation. J Antibiot. 2000;53:694–704. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai P, Kong F, Ruppen ME, Glasier G, Carter GT. Hygrocins A and B, naphthoquinone macrolides from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1736–1742. doi: 10.1021/np050272l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heisey RM, Putnam AR. Herbicidal effects of geldanamycin and nigericin, antibiotics from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Nat Prod. 1986;49:859–865. doi: 10.1021/np50047a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugawara K, Nlshiyama Y, Toda S, Komiyama N, Hatori M, Moriyama T, et al. Lactimidomycin‡ a new glutarimide group antibiotic production, isolation, structure and biological activity. J Antibiot. 1992;45:9. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deboer C, Meulman PA, Wnuk RJ, Peterson DH. Geldanamycin, a new antibiotic. J Antibiot. 1970;23:1433–1441. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.23.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imada A, Nozaki Y, Hasegawa T, Igarasi S, Yoneda M, Mizuta E. Carriomycin, a new polyether antibiotic produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Antibiot. 1978 doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.77-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deboer C, Dietz A. The description and antibiotic production of Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. Geldanus. J Antibiot. 1976;29:1182–8. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh MP, Petersen PJ, Weiss WJ, Janso JE, Luckman SW, Lenoy EB. Mannopeptimycins, new cyclic glycopeptide antibiotics produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus LL-AC98: antibacterial and mechanistic activities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:62–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.62-69.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson LE, Dietz A. Scopafungin, a crystalline antibiotic produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. Enhygrus var. Nova. Appl Microbiol. 1971;22:303–308. doi: 10.1128/am.22.3.303-308.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukai T, Kuroda J, Nomura T, Jun U, Akao M. Skeletal structure of neocopiamycin B from Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. Crystallogenes. J Antibiot. 1999;52:340–344. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui H, Sato K, Enei H, Hirose Y. Production of guanosine by psicofuranine and decoyinine resistant mutants of Bacillus subtilis. Agric Biol Chem. 1979;43:1739–1744. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1979.10863695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omura S, Iwai Y, Takahashi Y, Sadakane N, Nakagawa A, Oiwa H. Herbimycin, a new antibiotic produced by a strain of Streptomyces. J Antibiot. 1979;32:255–261. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gesheva V. Optimization of the production medium for biosynthesis of antifungal antibiotic Ak-111-81 by phosphate-deregulated mutant of Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;158:20–24. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanova V, Gesheva V, Kolarova M. Dihydroniphimycin: New polyol macrolide antibiotic produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus 15. Isolation and structure elucidation. J Antibiot. 2000;53:627–632. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uyeda M, Mizukami M, Yokomizo K, Suzuki K. Pentalenolactone I and hygromycin A, immunosuppressants produced by Streptomyces filipinensis and Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65:1252–1254. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palaniappan N, Ayers S, Gupta S, Habib ES, Reynolds KA. Production of hygromycin A analogs in Streptomyces hygroscopicus NRRL 2388 through identification and manipulation of the biosynthetic gene cluster. Chem Biol. 2006;13:753–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakajima M, Itoi K, Takamatsu Y, Kinoshita T, Okazaki T, Kawakubo K. Hydantocidin: a new compound with herbicidal activity from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Antibiot. 1991;44:293–300. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato H, Nagayama K, Abe H, Kobayashi R, Ishihara E. Isolation, structure and biological activity of trialaphos. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:1133–1134. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1991.10870694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nair MG, Thorogood DL, Chandra A, Ammermann E, Walker N, Kiehs K. Gopalamicin, an antifungal macrodiolide produced by Soil Actinomycetes. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:2308–2310. doi: 10.1021/jf00046a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anandan R, Dharumadurai D, Manogaran GP. Marine Microbiology: Bioactive Compounds and Biotechnological Applications. New York: Wiley publishers; 2016. An Introduction to Actinobacteria; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nindita Y, Cao Z, Fauzi AA, Teshima A, Misaki Y, Muslimin R. The genome sequence of Streptomyces rochei 7434AN4, which carries a linear chromosome and three characteristic linear plasmids. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, Qu S, Lu C, Zheng H, Zhou X, Bai L, Deng Z. Genomic and transcriptomic insights into the thermo-regulated biosynthesis of validamycin in Streptomyces hygroscopicus 5008. BMC Genom. 2012;13:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee SH, Choe H, Bae KS, Park DS, Nasir A, Kim KM. Complete genome of Streptomyces hygroscopicus subsp. limoneus KCTC 1717 (= KCCM 11405), a soil bacterium producing validamycin and diverse secondary metabolites. J Biotechnol. 2016;219:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volff JN, Altenbuchner J. Genetic instability of the Streptomyces chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:239–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Risdian C, Mozefm T, Wink J. Biosynthesis of polyketides in Streptomyces. Microorganisms. 2019;7:124. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7050124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwecke T, Apariciom JF, Molnár I, König A, Khaw LE, Haydock SF, Caffrey P, Cortes J, Lester JB. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyketide immunosuppressant rapamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7839–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molnár I, Aparicio JF, Haydock S, Khaw LE, Schwecke T, König A, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. Organisation of the biosynthetic gene cluster for rapamycin in Streptomyces hygroscopicus: analysis of genes flanking the polyketide synthase. Gene. 1996;169:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gatto GJ, Boyne MT, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Biosynthesis of pipecolic acid by RapL, a lysine cyclodeaminase encoded in the rapamycin gene cluster. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3838–3847. doi: 10.1021/ja0587603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuščer E, Coates N, Challis I, Gregory M, Wilkinson B, Sheridan R, Petkovic H. Roles of rapH and rapG in positive regulation of rapamycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4756–4763. doi: 10.1128/JB.00129-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patva NL, Demain AL, Roberts MF. Incorporation of acetate, propionate, and methionine into rapamycin by streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Nat Prod. 1991;54:167–177. doi: 10.1021/np50073a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson DJ, Patton S, Florova G, Hale V, Reynolds KA. The shikimic acid pathway and polyketide biosynthesis. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;20:299–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrman KM, Weaver LM. The shikimate pathway. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:473–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andexer JN, Kendrew SG, Nur-e-Alam M, Lazos O, Foster TA, Zimmermann AS, Warneck TD, Suthar D, Coates NJ, Koehn FE, Skotnicki J. Biosynthesis of the immunosuppressants FK506, FK520, and rapamycin involves a previously undescribed family of enzymes acting on chorismate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4776–4781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015773108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gregory MA, Gaisser S, Lill RE, Hong H, Sheridan RM, Wilkinson B. Isolation and characterization of pre-rapamycin, the first macrocyclic intermediate in the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant rapamycin by S. hygroscopicus. Angew Chemie - Int Ed. 2004;43:2551–2553. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kwan DH, Schulz F. The stereochemistry of complex polyketide biosynthesis by modular polyketide synthases. Molecules. 2011;16:6092–115. doi: 10.3390/molecules16076092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lowden PA, Wilkinson, Böhm GA, Handa S, Floss HG, Leadlay PF, Staunton J. Origin and true nature of the starter unit for the rapamycin polyketide synthase. Angew Chemie - Int Ed. 2001;40:799–801. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010216)40:4<777::AID-ANIE7770>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.König A, Schwecke T, Molnár I, Böhm GA, Lowden PA, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. The pipecolate-incorporating enzyme for the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant rapamycin - nucleotide sequence analysis, disruption and heterologous expression of rapP from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:526–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarkaria JN, Tibbetts RS, Busby EC, Kennedy AP, Hill DE, Abraham RT. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases by the radiosensitizing agent wortmannin. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4375–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chow LQ, Chen C, Raben D. EGFR inhibitors and radiation in HNSCC. Curr Cancer Ther Rev. 2007;3:255–266. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-1-11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zou Z, Tao T, Li H, Zhu X. MTOR signaling pathway and mTOR inhibitors in cancer: progress and challenges. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:1–1. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00396-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sarbassov DD, Guertin D, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. MTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;168:960–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science. 1996;273:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.You JS. The role of diacylglycerol kinase Zeta in Mechanotransduction: a positive Regulator of skeletal muscle Mass. Madison: The University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leone M, Crowell KJ, Chen J, Jung D, Chiang GG, Sareth S, Abraham RT, Pellecchia M. The FRB domain of mTOR: NMR solution structure and inhibitor design. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10294–10302. doi: 10.1021/bi060976+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gingras AC, Kennedy SG, O’Leary MA, Sonenberg N, Hay N. 4E-BP1, a repressor of mRNA translation, is phosphorylated and inactivated by the akt(PKB) signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:502–513. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brunn GJ, Hudson CC, Sekulic A, Williams JM, Hosoi H, Houghton PJ, Lawrence JC, Jr, Abraham RT. Phosphorylation of the translational repressor PHAS-I by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Science. 1997;277:99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dufner A, Andjelkovic M, Burgering BMT, Hemmings BA, Thomas G. Protein kinase B localization and activation differentially affect S6 kinase 1 activity and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-Binding protein 1 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4525–4534. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vignot S, Faivre S, Aguirre D, Raymond E. mTOR-targeted therapy of cancer with rapamycin derivatives. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:525–537. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chatterjee A, Mukhopadhyay S, Tung K, Patel D, Foster DA. Rapamycin-induced G1 cell cycle arrest employs both TGF-β and rb pathways. Cancer Lett. 2015;360:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim DH, Sabatini DM. Raptor and mTOR: subunits of a nutrient-sensitive complex. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 259 – 70. 2003 doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18930-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu L, Zaloudek C, Mills GB, Gray J, Jaffe RB. In-vivo and in-vitro ovarian carcinoma growth inhibition by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor (LY294002) Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:880–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seufferlein T, Rozengurt E. Galanin, neurotensin, and phorbol esters rapidly stimulate activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5758–5764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hidalgo M, Rowinsky EK. The rapamycin-sensitive signal transduction pathway as a target for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19:6680–6686. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kawamata S, Sakaida H, Hori T, Maeda M, Uchiyama T. The Upregulation of p27Kip1 by Rapamycin results in G1 arrest in exponentially growing T-Cell lines. Blood Am J Hematol. 1998;91:561–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aagaard-Tillery KM, Jelinek DF. Inhibition of human B lymphocyte cell cycle progression and differentiation by rapamycin. Cell Immunol. 1994;91:561–569. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gonzalez J, Harris T, Childs G, Prystowsky MB. Rapamycin blocks IL-2-driven T cell cycle progression while preserving T cell survival. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:572–585. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Monfar M, Lemon KP, Grammer TC, Cheatham L, Chung J, Vlahos CJ, Blenis J. Activation of pp70/85 S6 kinases in interleukin-2-responsive lymphoid cells is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and inhibited by cyclic AMP. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:326–337. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sigal NH, Dumont FJ. Cyclosporin A, FK-506, and rapamycin: pharmacologic probes of lymphocyte signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:519–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991;253:905–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1715094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structure of FKBP-FK506, an immunophilin-immunosuppressant complex. Science. 1991;252:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1709302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rahal EA, Chakhtoura M, Abu Dargham R, Khauli RB, Medawar W, Abdelnoor AM. Advantages of sirolimus in a calcineurin-inhibitor minimization protocol for the immunosuppressive management of kidney allograft recipients. ISRN Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/536484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vellanki S, Garcia AE, Lee SC. Interactions of FK506 and rapamycin with FK506 binding protein 12 in opportunistic human fungal pathogens. Front mol biosci. 2020;416:113544. doi: 10.1126/science.1709302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunol Today. 1992;13:136–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90111-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blankenship JR, Heitman J. Calcineurin is required for Candida albicans to survive calcium stress in serum. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5767–5774. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5767-5774.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forgacs B, Merhav HJ, Lappin J, Mieles L. Successful conversion to rapamycin for calcineurin inhibitor-related neurotoxicity following liver transplantation. Transpl Proc. 2005;37:912–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saunders R, Metcalfe MS, Nicholson ML. Rapamycin in transplantation: a review of the evidence. Kidney Int. 2001;59:3–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fantus D, Thomson AW. Evolving perspectives of mTOR complexes in immunity and transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:891–902. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Poston RS, Billingham M, Hoyt EG, Pollard J, Shorthouse R, Morris RE, Robbins RC. Rapamycin reverses chronic graft vascular disease in a novel cardiac allograft model. Circulation. 1999;100:67–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Neuhaus P, Klupp J, Langrehr JM. mTOR inhibitors: an overview. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:473–484. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.24645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dumont FJ, Su Q. Mechanism of action of the immunosuppressant rapamycin. Life Sci. 1995;58:373–395. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luo H, Chen H, Daloze P, Chang JY, St-Louis GWJ. Inhibition of in-vitro immunoglobulin production by rapamycin. Transplantation. 1992;53:1071–1076. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199205000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kasap B. Sirolimus in pediatric renal transplantation. Pediatr Transpl. 2011;15:673–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Granger D, Cromwell JW, Chen SC, Goswitz JJ, Morrow DT, Beierle FA, Suren, Sehgal Daniel M, Canafax, Arthur J, Matas AL. Prolongation of renal allograft survival in a large animal model by oral rapamycin monotherapy. Transplantation. 1995;59:183–186. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Almond PS, Moss A, Nakhleh RE, Melin M, Chen S, Salazar A, Ken Shirabe, Arthur J, Matas Rapamycin: immunosuppression, hyporesponsiveness, and side effects in a porcine renal allograft model. Transplantation. 1993;56:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Renders L, Steinbach R, Valerius T, Schöcklmann HO, Kunzendorf U. Low-dose sirolimus in combination with mycophenolate mofetil improves kidney graft function late after renal transplantation and suggests pharmacokinetic interaction of both immunosuppressive drugs. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2004;27:181–185. doi: 10.1159/000079808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mancini D, Pinney S, Burkhoff D, LaManca J, Itescu S, Burke E, Edwards N, Oz M, Marks AR. Use of rapamycin slows progression of cardiac transplantation vasculopathy. Circulation. 2003;108:48–53. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070421.38604.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kushwaha SS, Khalpey Z, Frantz RP, Rodeheffer RJ, Clavell AL, Daly RC, Christopher G, McGregor., Brooks S, Edwards, Sirolimus in cardiac transplantation: Use as a primary immunosuppressant in calcineurin inhibitor-induced nephrotoxicity. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bestetti R, Theodoropoulos TAD, Burdmann EA, Abbud FM, Cordeiro JA, Villafanha D. Switch from calcineurin inhibitors to sirolimus-induced renal recovery in heart transplant recipients in the midterm follow-up. Transplantation. 2006;81:692–696. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000177644.45192.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Delgado JF, Crespo MG, Manito N, Camprecios M, Rábago G, Lage E, Arizón JM, Roig E, Lage E. Usefulness of sirolimus as rescue therapy in heart transplant recipients with renal failure: analysis of the spanish multicenter observational study (RAPACOR) Transpl Proc. 2009;41:3835–3837. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ussetti P, Laporta R, De Pablo A, Carreno C, Segovia J, Pulpón L (2003) Rapamycin in lung transplantation: preliminary results. Transpl Proc 35(5):1974–1977. 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00688-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Fine NM, Kushwaha SS. Recent advances in mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor use in Heart and Lung Transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100:2558–2568. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang Z, Wu X, Duan J, Hinrichs D, Wegmann K, Zhang GL, Hall M, Rosenbaum JT. Low dose rapamycin exacerbates autoimmune experimental uveitis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Peng L, Wu C, Hong R, Sun Y, Qian J, Zhao J, Wang Q, Tian X, Wang Y, Li M, Zeng X. Clinical efficacy and safety of sirolimus in systemic lupus erythematosus: a real-world study and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yin Y, Choi SC, Xu Z, Perry DJ, Seay H, Croker BP, et al. Normalization of CD4 + T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(274):274ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mayer DF, Kushwaha SS. Transplant immunosuppressant agents and their role in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:219–225. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200305000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McInnes IB, O’Dell JR. State-of-the-art: rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1898–906. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]