Abstract

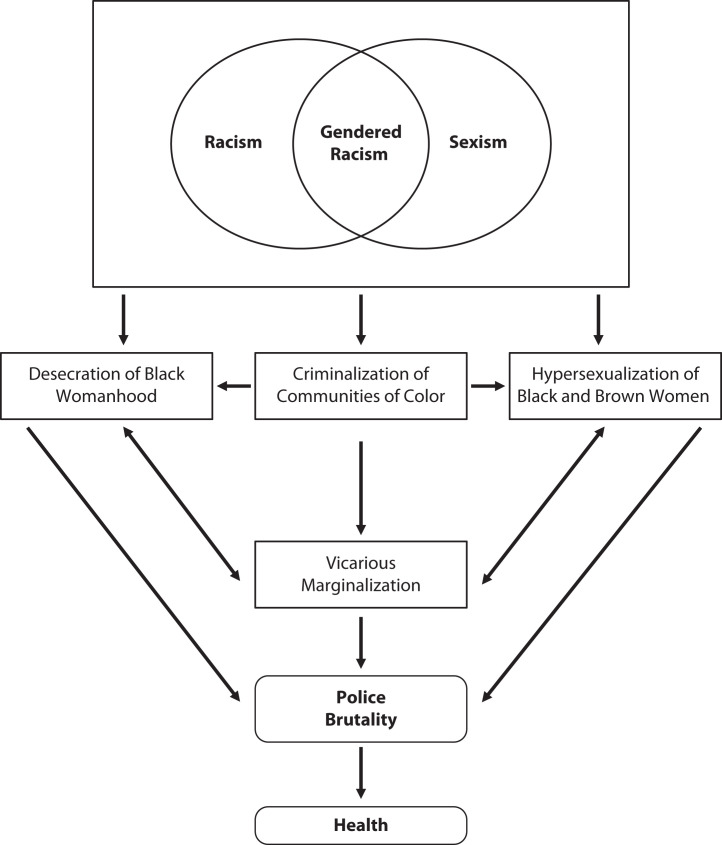

Police brutality harms women. Structural racism and structural sexism expose women of color to police brutality through 4 interrelated mechanisms: (1) desecration of Black womanhood, (2) criminalization of communities of color, (3) hypersexualization of Black and Brown women, and (4) vicarious marginalization.

We analyze intersectionality as a framework for understanding racial and gender determinants of police brutality, arguing that public health research and policy must consider how complex intersections of these determinants and their contextual specificities shape the impact of police brutality on the health of racially minoritized women.

We recommend that public health scholars (1) measure and analyze multiple sources of vulnerability to police brutality, (2) consider policies and interventions within the contexts of intersecting statuses, (3) center life course experiences of marginalized women, and (4) assess and make Whiteness visible. People who hold racial and gender power—who benefit from racist and sexist systems—must relinquish power and reject these benefits. Power and the benefits of power are what keep oppressive systems such as racism, sexism, and police brutality in place. (Am J Public Health. 2023;113(S1):S29–S36. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307064)

Police brutality is a social determinant of health, causing mortality, morbidity, and disability.1,2 Police brutality also extends to police neglect and words, policies, and actions that dehumanize, intimidate, and cause physical, psychological, and sexual harm.1,3 Police brutality can be experienced directly through personal contact with the police, vicariously through witnessing or hearing about police actions in the media or within one’s kin and social networks, and ecologically through living, working, or attending schools in heavily policed neighborhoods.2,4

Exposure to and health consequences of police brutality are not equally distributed. Racially minoritized communities are disproportionately exposed to police brutality, significantly increasing mortality rates and elevating odds of physical and psychological problems.2 Even though most of the research focuses on male victims of police brutality,5 Black and other women and gender-nonconforming people of color are significantly harmed, and their experiences rendered invisible.6 Intersectionality behooves us to analyze beyond the racism of police brutality.

We examine how intersecting systems of racism and sexism expose racially minoritized women to police brutality. We also discuss the relevance of applying an intersectionality framework in research that examines the health impacts of police brutality and in the development of policies to eliminate this form of structural violence that harms women of color.

We use “women of color” to refer to Black women and other racially minoritized women who are not racialized as White. We understand that anti-Blackness is at the center of structural racism and police brutality7 and that, even within the heterogeneous category of “women of color,” Black women experience anti-Black racism perpetrated and sustained by other women of color.8 However, our analysis focuses on the experiences of women of color to acknowledge the complex reality that we are all victims of the White supremacy that makes structural racism possible, and we can be complicit in each other’s oppression. We simultaneously center the experiences of Black women and incorporate how other women of color, especially Indigenous women and Latinas, are racialized and gendered in ways that disproportionately expose them to police brutality.

POLICE BRUTALITY, RACISM, AND SEXISM

Police brutality is not new. Colonizers who settled in what is now known as New England appointed constables to police and murder Indigenous Peoples, ensuring control over seized lands.9 During the antebellum era, White men of various social classes were deputized by the law to surveil, whip, arrest, shoot, and lynch enslaved and freed Black persons.10 Moreover, law enforcement officers encouraged the beatings and killings of (perceived) Mexicans who were considered trespassers. Law enforcement officers often secured victims, enabling White mobs to murder them.11 That Black and Brown communities continue to be disproportionately exposed to police brutality2 tells us that policing is a tool of White supremacy and racial domination. Indeed, contemporary evidence that being White protects from police brutality12 also demonstrates that the system of policing has remained unchanged.

Police brutality is the most enduring form of structural racism.13 We define structural racism as the universe of historical and contemporary factors that operate across multiple systems and institutions to foster racial oppression by providing power, privileges, and resources to people who are White at the expense of others who are not White.14 As a form of structural racism, police brutality is sustained by many systems. It influences processes, expectations, and outcomes across other systems in ways that continue to disadvantage racially minoritized communities.

Police brutality is also sustained by structural sexism, and it shapes people’s experiences and life chances by gender.5 We define sexism as a cumulative array of factors that operate across institutions to ensure male supremacy at the expense of women and gender-nonconforming persons.15 Structural sexism is characterized by pervasive and “systematic gender inequality in power and resources—at the macro, meso, and micro levels of the gender system.”15(p487) Gender inequities disproportionately expose women to police neglect and to sexual harassment by police.5,16 These inequities foster entitlement to and sexualization of women’s bodies by both the police and the public. Women’s claims of and worries about police brutality, as well as their demands to the police, are easily dismissed because of systematic deprioritization of their needs.17

GENDERED RACISM AND POLICE BRUTALITY

Gendered racism refers to a distinct form of structural racism that is perpetuated and experienced along gender lines.18 This concept was introduced specifically to highlight how the racial oppression of Black women is structured by racist perceptions of gender that are mediated by institutional and interpersonal actions.18 For women not racialized as White, gendered racism encompasses and extends beyond the separate and additive effects of structural racism and structural sexism. It recognizes that (1) racism harms women of color like it does men of color, (2) sexism harms women of color like it does White women, and (3) a third phenomenon—a hybrid of racism and sexism—emerges as a unique axis of oppression that harms women of color in multiplicative ways. Gendered racism draws from Black feminist and womanist frameworks that emphasize intersectionality—how ideologies, structures, and systems of oppression intersect with each other to reproduce new axes of oppression.19–21

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework to analyze the interconnected nature of systemic oppression.21 It examines power dynamics within and between groups and makes visible the interlocking, distinct, multiplicative, and evolving ways that policies and practices impact individuals and groups based on their relationship to power.21,22 Intersectionality calls attention to how the needs and experiences of Black women are ignored by White feminist movements and by antiracist movements that predominantly center the experiences of Black men, underscoring that racism and sexism are inextricably linked in their influence on the life chances of Black women. This analysis is scarce within the literature about the public health impacts of police brutality.

Even though other systems of inequality shape the health of Black women, such as social class, cis-heteronormativity, citizenship, and disability, to name a few, we examine 2 main systems and their impact on police brutality: racism (race) and sexism (gender). We focus on the intersection of racism and sexism because public health discourse on police brutality often centers victims as men, especially Black men. This further makes invisible the multiple ways by which Black and other women of color are harmed by police violence. Given limited national data on how police brutality impacts Black women specifically, our analyses of mechanisms through which intersecting systems of racism and sexism expose them to police brutality over the life course can help inform research and policy, including data collection, analyses, and implementation of interventions. These 4 interrelated mechanisms include (1) desecration of Black womanhood, (2) criminalization of communities of color, (3) hypersexualization of Black and Brown women, and (4) vicarious marginalization (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Four Interrelated Mechanisms Connecting Gendered Racism and Police Brutality

Desecration of Black Womanhood

Womanhood is typically perceived as White. Black women are often dehumanized and perceived as outside of the category of “woman.”23 Desecration of Black womanhood describes how Black women are held in opposition to the White supremacist ideal of White women as the exemplar of womanhood. White women are perceived as pure, righteous, and worthy of protection and dignity, and their sanctification occurs at the expense of Black women. For example, during the first wave of incarceration of women in the late 1800s, Black women were disproportionately arrested and imprisoned.24 Like Black men, they were considered aggressive.24 Unlike White women, they were rarely perceived to have been sufficiently punished, or to have suffered enough. They were not perceived as having the “feminine” qualities ascribed to womanhood, qualities that merited patriarchal protection—submissiveness, fragility, and soft-spokenness. Black women were imprisoned alongside men. In contrast, reformatories were opened to house White women who were perceived to need moral reform and protection from the bad influence of Black women and from dangerous Black men.24

Indeed, this dehumanization goes as far back as the time of slavery. Black women were chattel: nonpeople.23 They were treated as tools for wealth accumulation through grueling labor they were forced to perform and through childbearing: the children they bore and loved were also considered chattel. They were forced to literally (routinely through rape) reproduce the labor force.23 Because of gendered racism, even after the formal abolition of slavery in the 19th century, Black women continue to be dehumanized, viewed as disposable, inherently threatening, and not worthy of defense.21,23

Today, Black women and Latinas report higher rates of police brutality in the forms of physical police violence, psychological intimidation, and police neglect, compared with non-Latina White women.25 Black and Indigenous women have disproportionately greater risk of being killed at the hands of police, a rate more than twice that of White women.26 In gendered racialized dynamics, White men and police officers serve as “protectors” of normative White womanhood. However, Black and other women of color are desecrated—perceived as perpetual threats—and their humanity rendered invisible by state agents.5 Racist stereotypes and tropes of Black women such as being “lazy,” “loud,” and “promiscuous” also desecrate Black womanhood, elevating exposure to police brutality.6 Desecration of Black womanhood is shaped in part by the criminalization of Black and Brown communities, communities to which Black women belong (Figure 1).

Criminalization of Black and Brown Communities

Routinely racialized forms of policing in general and the war on drugs in particular facilitate the criminalization and routine profiling of Latina, Black, and Indigenous women as drug couriers and purveyors, leading to disproportionate stops, searches, detention, and incarceration of women of color.6 Indeed, before the police-perpetrated death of Sandra Bland that began as a result of a traffic stop, Bland had been arrested twice and charged for possession of small amounts of marijuana. After her first arrest, she served 30 days in Harris County jail, a facility that is among the Department of Justice’s most criticized facilities for unconstitutional confinement.6 Black women are routinely victims of violent policing. As scholars have documented, many unarmed Black girls and women have been killed and physically assaulted by police, including 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, who was killed while she was sleeping, and 22-year-old Rekia Boyd, who was shot in the head and killed in Chicago in 2015.27

Women of color and members of their social and kin networks are targeted in the racist War on Drugs. For example, Breonna Taylor’s ex-boyfriend was the subject of an ongoing drug investigation. Taylor’s affiliation to him was used as an excuse to issue a no-knock warrant for her address, criminalizing and murdering her in her own apartment.28 Tarika Wilson and her 14-month-old son were killed under similar circumstances, shot by police during a drug raid targeting a Black man. Wilson was at home, holding her son.27

Black women’s survivorship and attempts at self-protection are also criminalized.29 For example, girls and women like Marissa Alexander, Cyntoia Brown, Alisha Walker, and CeCe McDonald were criminalized for defending themselves from interpersonal violence from which the police provided no safety. Many Black women and gender-nonconforming survivors continue to be incarcerated for the “crime” of protecting themselves from perpetrators of violence. As Kaba puts it, unlike normative White women, Black survivors of violence are treated as though they deserve abuse, and as though they are “incapable of claiming a self worth defending.”29(p32)

Hypersexualization

Gendered racism helps explain the sexualized nature of police violence toward women of color. As building blocks of the United States, racial capitalism and colonialism rely on ownership and exploitation of bodies that are racialized as Black and Brown.30 Racial capitalism and colonialism are co-constitutive—they reinforce each other and co-produce other forms of oppression. They are also patriarchal, with both relying on the “sexual exploitation of women of color through rape and systems of concubinage.”31(p2) One of the contemporary manifestations of sexual exploitation of Black and other non-White women is hypersexualization—assumptions that women of color are sexually deviant, aggressive, available, and promiscuous.32 Hypersexualization is driven, in part, by criminalization of Black and Brown communities. Thus, it facilitates surveillance of the bodies of women of color as well as sexual violence against them. It is no surprise that women of color are more likely than any other group to be sexually harassed, assaulted, and raped by the police during searches and routine traffic and street stops.16 Data from the experiences of women in Baltimore, Maryland; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Washington, DC, suggest that Latinas experience police sexual violence at much higher rates than non-Latina White women.25 Indigenous women and transgender women of color are also disproportionately victims of police sexual harassment, assault, and rape.6

Police disproportionately threaten women of color with drug-related arrests and charges that can lead to incarceration or interfere with work and family life if they do not perform sexual acts.6 Police sexual violence extends beyond harassment, assault, and rape. It includes invasions of privacy such as voyeurism and viewing and distributing sexually explicit photographs or videos of crime victims.16 Unnecessary pat downs and strip and body cavity searches are also forms of police sexual violence commonly perpetrated against girls and women of color.6

The Burden of Vicarious Marginalization

Vicarious marginalization refers to “the marginalizing effect of police maltreatment that is targeted toward others.”33(p2104) Interlocking dimensions of gender, social class, and broader racial inequities constrain women of color who reside in impoverished neighborhoods. These margins of oppression symbolize a lack of power, and they increase exposure and vulnerability to police brutality. Vicarious exposure to police brutality—knowledge about the harmful experiences of others within one’s network—might increase anticipatory stress of police brutality. As women of color are typically perceived as pillars of and caregivers in their communities, gender norms compel them to assume protector and provider roles for family members and friends, including those arrested, incarcerated, or murdered by the police.34 These burdens can increase stress and take away from resources that matter for health—hence, affecting health outcomes.

Moreover, perceiving their own vulnerability to police brutality as secondary, Black and Indigenous women often focus their attention on the physical appearance of Black and Indigenous boys and men in their lives—for example, their clothing, hair, weight and height—given how their looks might expose them to police brutality,35 often to the neglect of considerations for their own health and safety. As survivors of loved ones unjustly killed by the carceral system, Black women may face a rapid deterioration of health and early death from the stress of fighting for justice on the deceased’s behalf as well as from the trauma of the sudden loss. Erica Garner—daughter of Eric Garner, who was choked to death by police in 2014—died from a heart attack at age 27 after years of advocacy work. Journalistic work has also evidenced repeated reports of Black women survivors facing multiple physical health consequences in addition to the psychological trauma of the violent deaths of their loved ones. Structural racism in the form of racial residential segregation establishes disproportionately Black and Brown neighborhoods characterized by economic deprivation and lethal police surveillance.36

IMPLICATIONS

A significant and growing body of research links police brutality to various health outcomes.2 The violence and injustice of police brutality and its impact on health have centered police brutality as a salient determinant of health requiring policy action.37 To eliminate police brutality and address its health consequences, research and policy must address the complex ways in which systems such as race and gender intersect over the life course to increase exposure to police brutality, harming health. Considering multiple sources of vulnerability and how they increase or moderate risk independently and interconnectedly across different axes matters. This requires more systematic collection of various forms of data on police brutality, especially among Black and Brown women. For example, personal narratives, ethnographies, and interviews about the nature and outcomes of police brutality; the social, political, and economic contexts in which it is experienced and anticipated; and how it affects multiple health outcomes are important data for public health policy.

We propose 4 specific recommendations for research and policy:

-

1.

Research should examine multiple sources of vulnerability. Anti-Blackness is unquestionably at the center of police brutality.7 However, determinants of exposure to police brutality and the moderators of its impact on health should not be limited to anti-Blackness or anti‒Black masculinity. For example, lesbians, transgender women, and gender-nonbinary adults are more likely than their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts to be stopped, arrested, and verbally and physically assaulted by the police.2 Women with limited household incomes disproportionately experience psychological police violence and police neglect (police not responding when needed, responding too late, or responding inappropriately) compared with their peers with higher incomes.25 Data analyses on the impact of police brutality on health should not only examine these statuses independently but should also explore multiple systems that drive health consequences of police brutality and their intersections. As Lisa Bowleg writes, “intersectionality’s promise lies in its potential to elucidate and address health disparities across a diverse array of intersections including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, [socioeconomic status], disability, and immigration and acculturation status.”38(p1270) Researchers who seek to answer these questions must then apply analytic methods that focus on interlocking types of oppression. A systematic review by Guan et al.39 provides some examples. We must capture the multidimensionality of structural inequity in our research. Leveraging measures such as the Multidimensional Measure of Structural Racism can move this effort forward.40

-

2.

Consider the context of intersecting statuses in policy-making. Mechanisms through which factors such as race, gender identity, and disability, for example, intersect to shape exposure to police brutality and how this exposure affects health are context-specific and dynamic. Cisgender privilege might protect an impoverished Black woman from police brutality in the same context where her Blackness and disability increase her vulnerability. Interventions like divesting from carceral systems and instead investing in access to resources that matter for health like affordable housing can help reduce exposure to police brutality among Black unhoused and economically marginalized women who are disproportionately surveilled. However, intersectionality requires us to consider how Black transgender women, for example, will still face housing discrimination and other forms of transphobic exclusion and violence that ultimately leaves them exposed to and harmed by police brutality. Just like multiple intersecting systems and structures shape the health of women of color, multiple policies are required to address intersecting systems that shape health.

-

3.

Center the experiences of marginalized populations over the life course. An intersectionality framework requires us to analyze co-constitutive systems and mechanisms that shape health and to also ground these analyses in experiences of historically marginalized populations over their life course.22,38 This will make certain policies and interventions are responsive to their needs. For example, we know that Black, Latinx, and Indigenous households are exposed to police brutality at disproportionately higher rates than White households.2 As adults, women from these households continue to be exposed to police brutality because they are considered not worthy of defending29 or inherently violent, because they are perceived as proximal to criminalized Black and Brown men and because their communities and economic circumstances are more broadly marginalized and criminalized.5,6 Examining how direct police contact and vicarious and ecological exposure to police brutality during childhood, adolescence, and key periods in their lives affect health is important. Interventions to address the health impacts of police brutality must also consider the direct and indirect experiences of police brutality over the life course of women of color, especially women whose lives are at the intersection of multiple axes of oppression.

-

4.

Assess and expose the benefits of Whiteness. Finally, intersectionality emphasizes the relevance of power in shaping health.22,38 Structural racism is about power—systemic social, economic, and political domination. Structural racism is White-controlled; it is maintained and reproduced by the invisibility of Whiteness. Assessing the ways by which Whiteness, including normative constructions of White womanhood, sustains police brutality will make Whiteness more visible. Making Whiteness visible can contribute to the elimination of health inequities caused by police brutality and structural racism more broadly. Specifically, public health researchers must pose questions that explore how Whiteness limits exposure to police brutality and how and when it is mobilized as a powerful resource to buffer the impact of police brutality on the health of White and White-adjacent (benefiting from Whiteness by virtue of light skin but belonging to a racially minoritized group) people who might also be exposed.

CONCLUSION

Police brutality harms women. Women of color in the United States occupy at least 2 marginalized statuses. We argue that these statuses intersect in distinct ways to shape their exposure to police brutality and, ultimately, their health. Conceptualizations of gender, femininity, masculinity, and sexuality, while evolving, are constantly racialized. Assessing the impact of police brutality on the health of women of color in the context of historical and contemporary meanings and performances of sexuality and gender might expand our understanding of determinants of police brutality. Racist and sexist stereotypes, policies that target and criminalize Black and Brown communities, Black women’s attempt at survivorship and self-protection, and broader structural inequities intersect to expose women of color to police brutality. Simultaneously, police brutality is used to criminalize and punish them for experiencing these inequities.

Gender and race are not the only factors that matter for police brutality and health. Other factors such as socioeconomic status and (dis)ability intersect to increase or reduce vulnerability to police brutality and produce new mechanisms that connect police brutality to health. These factors, the nature of their intersections, and the mechanisms they create are context-specific and dynamic. A life course assessment of these intersections is an important research agenda for public health. Such research will help identify areas for specific interventions, as well as explore the impact of policies on differentially marginalized populations. Our 4 recommendations are not a 1-to-1 match with the 4 mechanisms we identify. Each recommendation matters for undoing all the mechanisms that connect gendered racism to police brutality. For example, multiple sources of data and measures of structural oppression can help us identify systems and patterns that desecrate Black womanhood or that facilitate the hypersexualization of women of color in different contexts. And decentering Whiteness will certainly dismantle all 4 mechanisms.

Ultimately, the goal is to eliminate police brutality, structural sexism, and structural racism. Investing in new, noncarceral ways to promote community safety is long overdue. Dismantling both structural racism and structural sexism matter significantly for improving the health of women of color. However, these efforts require the willingness of people who hold racial and gender power—who benefit from racist and sexist systems—to relinquish power and reject these benefits. Power and benefits of power are what keep oppressive systems in place. We have the tools to dismantle the systems of oppression that maintain police brutality; we must now decide if we have the will.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by a National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant (R01 HD103684).

Note. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies and views of the National Institutes of Health nor do they imply endorsement by the US government.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Human participants were not involved, therefore institutional review board approval was not required.

Footnotes

See also Jones and Santos-Lozada, p. S13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police brutality and Black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):662–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeVylder JE, Anglin DM, Bowleg L, Fedina L, Link BG. Police violence and public health. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2022;18(1):527–552. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072720-020644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandes S. Patterns of injustice: police brutality in the courts. Buffalo Law Review. 1999;47(3):1275. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.165395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurencin CT, Walker JM. Racial profiling is a public health and health disparities issue. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(3):393–397. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00738-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang S, Cooper FR, Rolnick AC. Race and gender and policing. Nevada Law Journal. 2020;21(3):885. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritchie AJ. Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buggs SG, Pittman Claytor C. Systemic anti-Black racism must be dismantled: statement by the American Sociological Association section on racial and ethnic minorities. Sociol Race Ethn. 2020;6(3):289–291. doi: 10.1177/2332649220941019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li A. Solidarity: the role of non-Black people of color in promoting racial equity. Behav Anal Pract. 2020;14(2):549–553. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kratcoski P, Cebulak W. Policing in democratic societies: an historical overview. In: Das D, Marenin O, editors. Challenges of Policing Democracies A World Perspective. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Gordon and Breach Publishers; 2000. pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinton E, Cook D. The mass criminalization of Black Americans: a historical overview. Annu Rev Criminol. 2021;4(1):261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-060520-033306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrigan WD, Webb C. Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848‒1928. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn KB, Goff PA, Lee JK, Motamed D. Protecting Whiteness: White phenotypic racial stereotypicality reduces police use of force. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2016;7(5):403–411. doi: 10.1177/1948550616633505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd RW. Police violence and the built harm of structural racism. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):258–259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of US racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homan P. Structural sexism and health in the United States: a new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. Am Sociol Rev. 2019;84(3):486–516. doi: 10.1177/0003122419848723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purvis DE, Blanco M. Police sexual violence: police brutality, #MeToo, and masculinities. Calif Law Rev. 2020;108:1487. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3403676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones N. The gender of police violence. Tikkun. 2016;31(1):25–28. doi: 10.1215/08879982-3446861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Essed P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Vol 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooks B. Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics. Boston, MA: South End Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins PH. Black feminist thought in the matrix of domination. In: Collins PH, editor. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman; 1990. pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankivsky O, Christoffersen A. Intersectionality and the determinants of health: a Canadian perspective. Crit Public Health. 2008;18(3):271–283. doi: 10.1080/09581590802294296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooks B. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler AM. Gendered Justice in the American West: Women Prisoners in Men’s Penitentiaries. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedina L, Backes BL, Jun H-J, et al. Police violence among women in four US cities. Prev Med. 2018;106:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards F, Lee H, Esposito M. Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(34):16793–16798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821204116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crenshaw KW, Ritchie AJ, Anspach R, Gilmer R, Harris L. Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women. New York, NY: African American Policy Forum; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin J. Breonna Taylor: transforming a hashtag into defunding the police. J Crim L Criminol. 2021;111(4):995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaba M. We Do This’ Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith A. Heteropatriarchy and the three pillars of White supremacy: rethinking women of color organizing. In: Dickinson TD, Schaeffer RK., editors. Transformations: Feminist Pathways to Global Change. New York, NY: Routledge; 2015. p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benard AAF. Colonizing Black female bodies within patriarchal capitalism: Feminist and human rights perspectives. Sex Media Soc. 2016;2(4):1–11. doi: 10.1177/2374623816680622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks S. Hypersexualization and the dark body: race and inequality among Black and Latina women in the exotic dance industry. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2010;7(2):70–80. doi: 10.1007/s13178-010-0010-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell MC. Police reform and the dismantling of legal estrangement. Yale Law J. 2017;126(7):2054–2150. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malone Gonzalez S. Making it home: an intersectional analysis of the police talk. Gend Soc. 2019;33(3):363–386. doi: 10.1177/0891243219828340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell AJ, Phelps MS. Gendered racial vulnerability: how women confront crime and criminalization. Law Soc Rev. 2021;55(3):429–451. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel M, Sherman R, Li C, Knopov A. The relationship between racial residential segregation and Black‒White disparities in fatal police shootings at the city level, 2013–2017. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(6):580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Public Health Association. 2022. https://apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/29/law-enforcement-violence [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan A, Thomas M, Vittinghoff E, Bowleg L, Mangurian C, Wesson P. An investigation of quantitative methods for assessing intersectionality in health research: a systematic review. SSM Popul Health. 2021;16:100977. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chantarat T, Van Riper DC, Hardeman RR. The intricacy of structural racism measurement: a pilot development of a latent-class multidimensional measure. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101092. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]