Abstract

Background

Multimorbidity frequently co-occurs with behavioral health concerns and leads to increased healthcare costs and reduced quality and quantity of life. Unplanned readmissions are a primary driver of high healthcare costs.

Objective

We tested the effectiveness of a culturally appropriate care transitions program for Latino adults with multiple cardiometabolic conditions and behavioral health concerns in reducing hospital utilization and improving patient-reported outcomes.

Design

Randomized, controlled, single-blind parallel-groups.

Participants

Hispanic/Latino adults (N=536; 75% of those screened and eligible; M=62.3 years (SD=13.9); 48% women; 73% born in Mexico) with multiple chronic cardiometabolic conditions and at least one behavioral health concern (e.g., depression symptoms, alcohol misuse) hospitalized at a hospital that serves a large, mostly Hispanic/Latino, low-income population.

Interventions

Usual care (UC) involved best-practice discharge processes (e.g., discharge instructions, assistance with appointments). Mi Puente (“My Bridge”; MP) was a culturally appropriate program of UC plus inpatient and telephone encounters with a behavioral health nurse and community mentor team who addressed participants’ social, medical, and behavioral health needs.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was 30- and 180-day readmissions (inpatient, emergency, and observation visits). Patient-reported outcomes (quality of life, patient activation) and healthcare use were also examined.

Key Results

In intention-to-treat models, the MP group evidenced a higher rate of recurrent hospitalization (15.9%) versus UC (9.4%) (OR=1.91 (95% CI 1.09, 3.33)), and a greater number of recurrent hospitalizations (M=0.20 (SD=0.49) MP versus 0.12 (SD=0.45) UC; P=0.02) at 30 days. Similar trends were observed at 180 days. Both groups showed improved patient-reported outcomes, with no advantage in the Mi Puente group. Results were similar in per protocol analyses.

Conclusions

In this at-risk population, the MP group experienced increased hospital utilization and did not demonstrate an advantage in improved patient-reported outcomes, relative to UC. Possible reasons for these unexpected findings are discussed.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02723019. Registered on 30 March 2016.

KEY WORDS: clinical trial, Hispanic Americans, mental health, multimorbidity, patient readmission, transitional care

Adults with multimorbidity (i.e., two or more chronic health conditions) experience an elevated risk of death, disability, functional limitations, and reduced quality of life.1–3 Multimorbidity contributes to steadily escalating US healthcare costs, in large part due to more frequent hospital admissions and readmissions.4,5 Multimorbidity frequently co-occurs with behavioral health concerns, such as depression and anxiety,6 which further increase risk of poor outcomes including hospital readmissions.7–9

The hospital discharge process involves conveyance of complex information and instructions, coordination of care, and information transfer, and includes multidisciplinary providers, patients, and caregivers.10,11 Patient factors such as pain, distress, or low health literacy can interfere with understanding, and many individuals face barriers (e.g., transportation, healthcare access) to following discharge instructions. Older adults and individuals with low income, who are more likely to suffer multimorbidity,12 are especially vulnerable to patient-level barriers. A lack of language-congruent, culturally appropriate processes creates barriers for ethnic and racial minority groups.13 The fragmented nature of the healthcare system also contributes to discontinuity in the care transition process.14

Many programs have been implemented to improve the transition from hospital to other settings.15 A 2022 Cochrane review of 33 studies concluded that patient-centered, structured, programs led to a small reduction in length of stay (LOS) and readmissions across 90 days, but no improvement in mortality.16 Little evidence was found for intervention effectiveness in improving participants’ functional status or well-being.16 Only three studies focused on settings that serve ethnically and racially diverse, low-income populations.17–19 Furthermore, many care transition interventions have been unsuccessful when tested in community settings where they meet patient-, system-, and payer-level barriers.15 Additional research is needed to understand how to improve care transitions in settings that serve diverse populations who may benefit most.

The current trial examined the effectiveness of a care transitions program for patients of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity with multiple cardiometabolic health conditions and behavioral health concerns. Chronic cardiometabolic conditions frequently cluster20 and commonly co-occur with behavioral health concerns such as depression or disease-related distress,21–23 and several are among the top ten diagnoses associated with 30-day readmissions.24 Hispanics/Latinos have high rates of cardiometabolic disorders and also exhibit worse outcomes,25 although there is substantial within ethnic group heterogeneity.26 In the USA, people of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity are more likely than non-Hispanic white persons to have untreated behavioral health concerns.27,28 This population is affected by social adversity and experiences unique care barriers such as limited English language proficiency and health literacy29 that can interfere with successful care transitions.

The Mi Puente (“My Bridge”; MP) program applied evidence-based care transitions approaches,19,30 while adapting materials and strategies for implementation in a hospital that serves a largely Hispanic/Latino, low-income population. We hypothesized that MP would reduce 30- and 180-day recurrent hospitalizations and improve patient-reported outcomes relative to usual care (UC).

METHODS

Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Scripps Health (reviewing) and San Diego State University (relying) and all participants provided written informed consent. Trial methods have previously been reported in detail31 and are briefly summarized below.

Participants and Setting

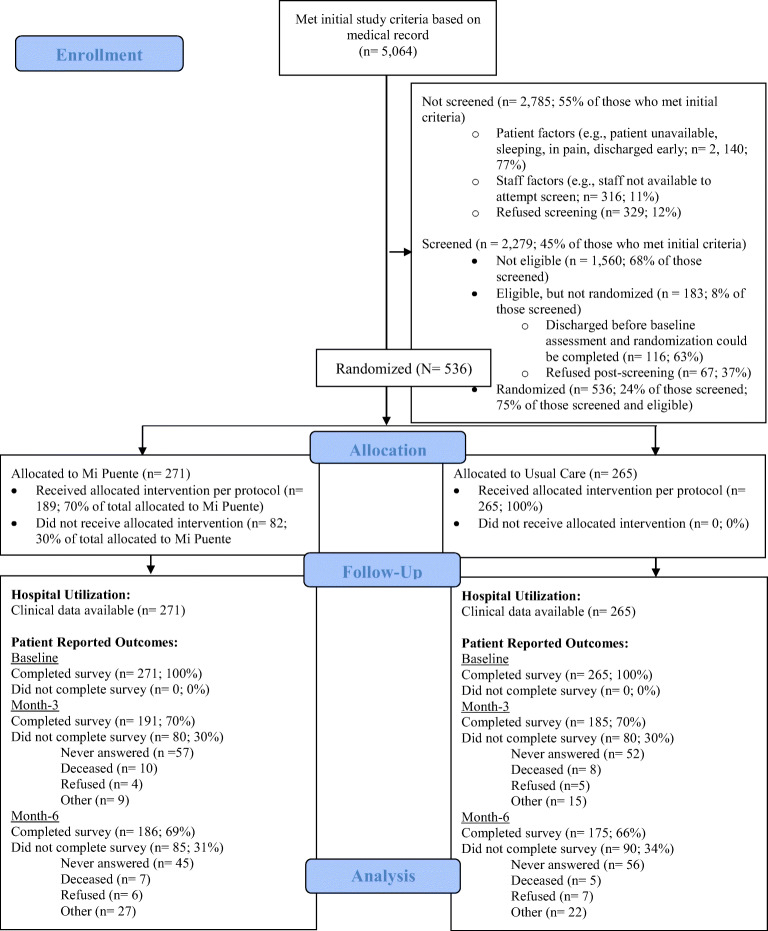

Between July 2016 and March 2020, the study enrolled 536 inpatients of a hospital in South San Diego County that serves a mostly Hispanic/Latino, low-income patient population. Eligibility criteria included the following: Hispanic/Latino ethnicity; age ≥ 18 years; English or Spanish proficiency; ≥ 2 cardiometabolic conditions (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular or cardiovascular diseases); and ≥ 1 behavioral health concern (depression or anxiety symptoms, disease-related distress, chronic stress, smoking, alcohol misuse, medication non-adherence, and/or lack of outpatient healthcare). Participants who were pregnant, had a life-threatening condition, could not provide informed consent, were being discharged to a location other than home, and/or had no telephone access were excluded. The CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1. The target sample size was N=560; however, enrollment was paused in March 2020, and then concluded early due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the design accommodated a 20% attrition rate, sample size was adequate for all analyses. This modification was approved by the study IRBs and funder.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Design, Blinding, and Randomization

The study used a randomized, controlled, single-blind, parallel-groups, superiority design. Participants and interventionists were not blinded given the nature of the intervention. However, individuals conducting medical records abstraction to evaluate the primary outcome of hospital readmissions, and assessors of patient-reported outcomes, were blinded to participants’ group assignments. Blinding of interviewers assessing patient-reported outcomes may have been violated in a small number of instances where, due to staffing issues, the same interviewer conducted both the in-person baseline and the telephone-based follow-up assessment, and they recalled the participant’s assignment, or the participant mentioned their group, during a follow-up interview.

Assignment to conditions was fully randomized with 1 to 1 allocation and no blocking or stratification. A computer-generated complete randomization sequence was conducted by the study statistician (SCR) and communicated to the study project manager, who placed the assignment within sealed, opaque envelopes that were labeled by sequential participant number. The project manager was not involved in participant screening, enrollment, or assessment. The randomization assignment was unveiled by the interviewer who screened and consented the participant, immediately following the baseline assessment.

Recruitment, Screening, and Enrollment

Daily electronic health records (EHR) lists identified potential participants based on primary inclusion/exclusion criteria. Participants were then approached at bedside to complete recruitment and screening for the presence of any behavioral health concern and telephone access. Patients who were interested and eligible completed written informed consent and baseline surveys, and then were randomized to MP or UC.

Interventions

The study compared UC to the MP behavioral health nurse (“nurse”) plus volunteer community mentor (“mentor”) team-led intervention.

UC patients received the hospital’s usual care discharge process with written discharge instructions, assistance with appointments and referrals, and other assistance (e.g., with billing, insurance) as required.

In addition to UC discharge processes, the MP group received support from the bilingual, bicultural nurse/mentor team. The program was designed to address patient needs holistically, with the nurse addressing medical, psychological, social, and logistical aspects of the care transition, and the mentor providing support and leveraging community resources to address adverse social determinants and other barriers. Components and content were guided by the Ideal Transitions in Care (ITC) framework15 and adapted processes and materials from evidence-based programs including project Re-Engineered Discharge (Project RED)19,32 and the Care Transitions Intervention30 to the specific socioeconomic, cultural, and health context. The program was flexible, patient-centered, and focused on engaging individuals as active participants in their healthcare.

The nurse component was conducted in an inpatient visit prior to discharge, and/or during a follow-up phone call within 1 week of discharge. The intervention consisted of the following: (1) Needs assessment; (2) Collaborative creation of a personal health record; (3) Goal setting and action planning; (4) Medication review; (5) Health education; (6) Discussion of symptom red flags; and (7) Assistance with outpatient follow-up and referrals. Family or other caregivers were encouraged to participate, consistent with the evidence base33 and Hispanic/Latino cultural values.34

The mentors had a shared cultural and community context with participants, and personal lived experience with the conditions of interest and/or healthcare system. They provided two to four, once-per-week support calls in the 30 days following discharge that aimed to motivate the patient and problem-solve around multilevel barriers. Mentors used a manual of community resources to address issues such as housing and food security, behavioral health, transportation, insurance/benefits, and emergency services.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was hospital readmissions (inpatient, emergency department (ED), observation) within 30 and 180 days post-discharge, obtained through EHR audits at the study site. Given the relatively small number of participants with more than one readmission, this variable was coded as “any” versus “no” readmission for primary analysis. Secondary outcomes included the count of readmissions and total inpatient LOS. Patient-reported outcomes were obtained in-person at baseline, and by telephone at 3 and 6 months. Measures included the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) Global-10 Health Scale,35 the 13-item Patient Activation Measure (PAM),36 and a short version of the Chronic Illness Resources Survey (CIRS) to assess supports for self-management over the past 3 months.37 Patients also self-reported healthcare use in the past 3 months (study specific measure), to examine changes in outpatient visits, ED and urgent care visits, and poor healthcare access (any inability to obtain care when needed in the past 3 months). Self-reported inpatient days were also collected to capture total hospitalizations, including those outside of the study setting. Data collection concluded in November 2020.

Covariates and Sample Characteristics

At baseline, participants reported sociodemographic characteristics and their preferred language. Housing security was added to the baseline assessment in January 2017. LACE index (a predictor of readmission and mortality risk that considers LOS, admission acuity, comorbidities, and ED use, and ranges from 1 (lowest risk) to 19 (highest risk)38) and index hospitalization LOS were derived from EHRs.

Treatment Fidelity

For MP, intervention delivery was monitored through checklists completed by the nurse and mentor at each encounter. We defined intervention “per protocol” as receiving a nurse contact within 1 week (either inpatient or telephone) and at least 2 mentor contacts within 30 days of discharge.

Statistical Methods

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and MPLUS.39 Descriptive analyses were conducted to describe the sample and examine baseline differences by group. Missing data analyses were conducted for the patient-reported outcomes only, since all participants had hospital outcomes, and examined associations of missingness with demographic and health variables shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics at Baseline, Overall, and by Group

| Variable | Total sample* N=536 |

Usual care N=265 |

Mi Puente N=271 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (M SD) | 62.30 (13.19) | 62.66 (12.21) | 61.94 (14.10) | 0.53 |

| Sex (N %) | 0.60 | |||

| Male | 279 (52.1) | 141 (53.2) | 138 (50.9) | |

| Female | 257 (47.9) | 124 (46.8) | 133 (49.1) | |

| Race (N %) | 0.63 | |||

| White | 150 (28.6) | 67 (26.0) | 83 (31.2) | |

| Black or African American | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 8 (1.5) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| More than one race | 35 (6.7) | 21 (8.1) | 14 (5.3) | |

| Some other race | 325 (62.0) | 164 (63.6) | 161 (60.5) | |

| Education (N %) | 0.03 | |||

| < High school education | 247 (48.1) | 134 (53.2) | 113 (43.3) | |

| ≥ High school education | 266 (51.9) | 118 (46.8) | 148 (56.7) | |

| Income (N %) | 0.68 | |||

| < 30,000 year | 414 (83.8) | 207 (83.1) | 207 (84.5) | |

| ≥ 30,000 year | 80 (16.2) | 38 (15.5) | 42 (16.9) | |

| Employment (N %) | 0.65 | |||

| Employed | 106 (20.5) | 50 (19.7) | 56 (21.3) | |

| Not employed | 411 (79.5) | 204 (80.3) | 207 (78.7) | |

| Marital status (N %) | 0.14 | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 260 (48.5) | 137 (51.7) | 123 (45.4) | |

| Not married/cohabitating | 276 (51.5) | 128 (48.3) | 148 (54.6) | |

| Place of birth (N %) | 0.08 | |||

| USA | 137 (25.6) | 58 (21.9) | 79 (29.2) | |

| Mexico | 390 (72.8) | 204 (77.0) | 186 (68.6) | |

| Other | 9 (1.7) | 3 (1.1) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Language (N %) | 0.09 | |||

| Spanish | 412 (76.9) | 212 (80.0) | 200 (73.8) | |

| English | 124 (23.1) | 53 (20.0) | 71 (26.2) | |

| Insurance (N %) | 0.43 | |||

| Uninsured | 39 (7.3) | 17 (6.4) | 22 (8.2) | |

| Insured (any) | 495 (92.7) | 248 (93.6) | 247 (91.8) | |

| Housing security† (N %) | 0.96 | |||

| Stable housing | 379 (89.6) | 188 (89.5) | 191 (89.7) | |

| Unstable housing | 44 (10.4) | 22 (10.5) | 22 (10.3) | |

| Health characteristics | ||||

| Total qualifying cardiometabolic conditions (M/SD) | 3.33 (1.37) | 3.35 (1.41) | 3.31 (1.33) | 0.75 |

| Total qualifying behavioral health concerns (M/SD) | 2.98 (1.61) | 3.03 (1.66) | 2.93 (1.56) | 0.47 |

| LACE index (M/SD) | 7.36 (2.33) | 7.47 (2.25) | 7.26 (2.41) | 0.31 |

| Index visit length of stay, days (M/SD) | 4.66 (5.24) | 4.45 (5.52) | 4.87 (4.95) | 0.35 |

*Sample sizes differ due to missing data for individual variables

†Self-reported housing security was added in January 2017 and is not available on the entire sample

Variables that differed by group at baseline were added as covariates to account for non-equivalence, along with age, sex, and LACE index. Statistical significance was assessed at alpha <.05. Unstandardized regression coefficients (B) or odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals, and P values are reported. The primary analyses followed intention-to-treat principles. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted, limiting the MP group to those who received the intervention per protocol as defined above.

Logistic regression models were conducted regressing any/no readmission in 30 or 180 days on “group” (MP or UC) and covariates. Readmissions count and total LOS were examined using negative binomial models, to account for significant overdispersion identified. For descriptive purposes, we also examined vital status at 180 days, using a logistic regression model; only 2 participants were deceased at 30 days.

Analyses of patient-reported outcomes used multilevel modeling with random intercepts and slopes, and the appropriate link function for a target outcome, with group (MP versus UC) as the between-subjects factor, time (weeks since baseline) as the within-subjects factor, and a cross-level, group-by-time interaction effect. These analyses used Robust Maximum Likelihood Estimation in MPLUS,39 in which model parameters and standard errors are estimated using all observed data, resulting in unbiased estimates under various missing data assumptions.40

RESULTS

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the sample. Nearly 50% had less than a high school education, and 83.8% had household incomes <$30,000/year. On average, participants had 3.33 cardiometabolic health conditions and 2.98 behavioral health concerns. MP participants had higher educational attainment than UC participants. As shown in Table 2, about 70% of MP participants received the intervention per protocol.

Table 2.

Proportion of Mi Puente Group (N=271) That Received the Intervention per Protocol-- Overall, Nurse, and Mentor Intervention Components

| Per protocol N (%) |

Not per protocol N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Nurse component (contact within 1 week of discharge) | 249 (91.9%) | 22 (8.1%) |

| Mentor component (at least 2 contacts within 30 days of discharge) | 202 (74.5%) | 69 (25.5%) |

| Overall (both nurse and mentor components completed per protocol) | 189 (69.7%) | 82 (30.3%) |

Missing data analyses indicated that N=305 participants (57%) completed patient-reported outcomes assessments at all timepoints; 53 (10%) and 40 (7.5%) were missing only the 3-month or 6-month assessment, respectively, and 112 (21%) were missing both follow-up assessments. Those with missing data at both timepoints (vs. complete data) were more likely to be male (48.7% vs. 37.0%), to be not married/living with their partner (47.5% vs. 38.5%), and to have unstable housing (70.0% vs. 40.3 %) (data not shown).

Table 3 displays the descriptive statistics and results from intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses of intervention effects for readmissions and vital status. The MP group had a significantly higher likelihood of any readmissions (15.9% versus 9.4%; OR 1.91, 95% CI, 1.09, 3.33) and more readmissions (M=0.20 versus 0.12; P=0.02) within 30 days than UC, respectively. At 180 days, there was a non-significant trend toward more readmissions and longer total LOS in the MP versus UC group. There was no difference in vital status at 180 days. The pattern of effects was similar in per protocol analyses.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Results of Intention-to-Treat and “Per Protocol” Regression Analyses for Hospitalization Outcomes

| Hospitalization outcome | Total sample N=536 |

Usual care N=265 |

Mi Puente N=271 |

Mi Puente “per protocol” N=189 |

Intention-to-treat analyses* N=563 |

“Per protocol” analyses† N=454 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | OR (95% CI) or B (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) or B (95% CI)* | P | |

| 30-day outcomes | ||||||||

| ≥1 hospitalization‡ | 68 (12.7) | 25 (9.4) | 43 (15.9) | 29 (15.3) | 1.91 (1.09, 3.33) | 0.01 | 1.89 (0.98, 3.37) | 0.06 |

| Hospitalization count§ | 0.16 (0.47) | 0.12 (0.45) | 0.20 (0.49) | 0.19 (0.49) | 0.65 (.11, 1.08) | 0.02 | 0.65 (0.05, 1.24) | 0.03 |

| Total length of stay‡ | 0.29 (1.33) | 0.19 (0.93) | 0.39 (1.63) | 0.32 (1.40) | 1.07 (−0.32, 2.46) | 0.13 | 0.93 (−0.64, 2.49) | 0.24 |

| 180-day outcomes | ||||||||

| ≥1 hospitalization‡ | 218 (40.7) | 98 (37.0) | 120 (44.3) | 85 (45.0) | 1.28 (−0.12, 2.62) | 0.19 | 1.35 (0.90, 2.02) | 0.15 |

| Hospitalization count§ | 0.85 (1.67) | 0.74 (1.43) | 0.97 (1.88) | 0.97 (1.81) | 0.26 (−0.26, 0.55) | 0.09 | 0.21 (−0.06, 0.58) | 0.11 |

| Total length of stay§ | 1.61 (4.53) | 1.28 (3.64) | 1.93 (5.24) | 1.60 (3.30) | 0.51 (−0.05, 1.08) | 0.07 | 0.51 (−0.15, 1.16) | 0.13 |

| Vital status deceased‡ | 30 (5.6) | 13 (4.9) | 17 (6.3) | 9 (4.8) | 1.35 (0.59, 3.08) | 0.48 | 1.09 (0.43, 2.76) | 0.85 |

*Analyses compare values for the usual care (referent, coded 0) versus the entire Mi Puente group (coded 1), controlling for age, sex, education, and LACE index

†Analyses compare values for the usual care (referent, coded 0) versus the Mi Puente group (coded 1) that received the intervention per protocol, controlling for age, sex, education, and LACE index

‡Analyzed using logistic regression model, statistics are N (%) and OR (95% CI)

§Analyzed using negative binomial regression model, statistics are M (SD), and unstandardized regression coefficient B (95% CI), which can be interpreted as the difference between groups in the logs of expected counts of hospitalizations

Both groups showed statistically significant improvements over time in patient-reported outcomes including quality of life, patient activation, resources for self-management, and reductions in urgent/ED visits, inpatient nights, and poor healthcare access (Table 4). There was no change in either group in the number of self-reported outpatient visits. A group-by-time interaction effect showed that the decrease in self-reported urgent/ED visits was larger for the UC versus MP group. For other patient-reported outcomes, there was no difference between the UC and MP groups in the level of change over time. Results of patient-reported outcomes analyses were similar in per protocol analyses.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics and Results of Intention-to-Treat and “Per Protocol” Multilevel Analyses for Patient-Reported Outcomes

| Variable | Usual care N=265 |

Mi Puente N=271 |

Mi Puente “per protocol” N=189 |

Group × time interaction effect, intention to treat* N=563 |

Group × time interaction effect, “per protocol”† N=454 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life (PROMIS scores)‡ | |||||

| B (95% CI); P | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14); P <0.001 | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14); P <0.001 | 0.11 (0.07, 0.14); P <0.001 | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.04); P = 0.73 | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.04); P = 0.80 |

| Baseline M (SD) | 26.63 (6.23) | 26.91 (6.00) | 27.32 (6.10) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 M (SD) | 29.13 (7.22) | 29.32 (6.62) | 29.60 (6.84) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 M (SD) | 29.57 (7.13) | 29.74 (7.32) | 30.32 (7.46) | -- | -- |

| Patient activation (PAM scores)‡ | |||||

| B (95% CI); P | 0.18 (0.10, 0.25); P <.001 | 0.23 (0.17, 0.30); P <.001 | 0.23 (0.15, 0.31); P <.001 | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.16); P = 0.28 | 0.05 (−0.16, 0.06); P = 0.36 |

| Baseline M (SD) | 61.85 (12.33) | 60.14 (11.40) | 60.27 (11.33) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 M (SD) | 65.58 (13.77) | 65.89 (13.21) | 66.72 (13.64) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 M (SD) | 66.81 (14.45) | 66.15 (11.87) | 66.10 (11.98) | -- | -- |

| Self-management resources (CIRS scores)‡ | |||||

| B (95% CI); P | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02); P <.001 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02); P <.001 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02); P <.001 | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01); P =0.71 | .00 (−0.01, 0.01); P = 0.47 |

| Baseline M (SD) | 2.78 (0.63) | 2.80 (0.68) | 2.89 (0.70) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 M (SD) | 3.18 (0.65) | 3.14 (0.64) | 3.18 (0.65) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 M (SD) | 3.14 (0.68) | 3.14 (0.69) | 3.19 (0.70) | -- | -- |

| Outpatient visits past 3 months§ | |||||

| B (95% CI); P | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01); P = 0.61 | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01); P = 0.55 | 0.00 (0.01, 0.02); P = 0.70 | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01); P = 0.42 | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.01); P = 0.54 |

| Baseline M (SD) | 4.42 (6.83) | 4.82 (7.20) | 4.82 (6.85) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 M (SD) | 5.01 (6.76) | 4.87 (6.20) | 4.81 (6.24) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 M (SD) | 4.39 (6.79) | 5.39 (7.79) | 5.37 (7.77) | -- | -- |

| Urgent care/ED visits past 3 months§ | |||||

| B (95% CI); P | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.02); P <.001 | −0.02 (−0.03, −0.01); P <.001 | −0.02 (−0.03,−0.01); P <.001 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03); P = 0.02 | 0.01 (0.00, 0.03); P = 0.03 |

| Baseline M (SD) | 1.49 (2.49) | 1.55 (1.73) | 1.43 (1.66) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 M (SD) | 1.18 (1.85) | 1.48 (1.96) | 1.44 (1.93) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 M (SD) | 0.65 (1.31) | 1.04 (1.57) | 0.99 (1.55) | -- | -- |

| Inpatient days past 3 months§ | |||||

| B (95% CI); P | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.01); P <0.001 | −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01); P <0.001 | −0.04 (−0.06 −0.02); P <0.001 | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.02); P = 0.98 | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02); P =0.50 |

| Baseline M (SD) | 2.87 (5.33) | 4.47 (9.17) | 4.13 (8.57) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 M (SD) | 3.22 (5.74) | 5.10 (9.58) | 5.38 (10.35) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 M (SD) | 2.62 (8.11) | 2.71 (6.92) | 1.97 (6.06) | -- | -- |

| Poor healthcare access in past 3 months‖ | |||||

| OR (95% CI); P | 0.90 (0.85, 0.96); P = 0.002 | 0.93 (0.87, 0.98); P = 0.02 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98); P = 0.02 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09); P = 0.23 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09); P = 0.25 |

| Baseline N (%) | 43 (16.2) | 42 (15.6) | 26 (13.8) | -- | -- |

| Month 3 N (%) | 20 (10.8) | 23 (12.0) | 16 (10.6) | -- | -- |

| Month 6 N (%) | 17 (9.7) | 23 (12.4) | 18 (12.3) | -- | -- |

*Analyses compare values for the usual care (referent, coded 0) versus the entire Mi Puente group (coded 1), controlling for age, sex, education, and LACE index

†Analyses compare values for the usual care (referent, coded 0) versus the Mi Puente group (coded 1) that received the intervention per protocol, controlling for age, sex, education, and LACE index

‡Analyzed using linear regression model. For within group comparisons, B can be interpreted as the change in the outcome (e.g., PAM score, inpatient days) for each 1-week increase in time beyond the baseline

§Analyzed using negative binomial regression model. For within group comparisons, B can be interpreted as the difference in the logs of expected counts of hospitalizations for each 1-week increase in time beyond the baseline

‖Analyzed using logistic regression model

DISCUSSION

The current study tested the effectiveness of a culturally appropriate care transitions intervention in reducing readmissions and improving patient-reported outcomes. Contrary to expectations, when compared to UC, the MP group showed increased hospital utilization as assessed by hospital records at 30 days and at 180 days (non-significant) and by self-report (i.e., changes in total ED/urgent care visits) across 6 months. Both groups showed improved patient-reported outcomes, with no advantage in the MP group.

There are several possible explanations for these unexpected results. First, although Mi Puente applied evidence-based concepts from effective programs,15,19,30,32 the intervention lacked a strong connection with outpatient care. As detailed previously,31 the trial included collaboration with a large Federally Qualified Health Center system that serves a sizeable segment of the South San Diego community, but practically, we could not directly connect many patients to this system due to differences in insurance, primary care providers, or preferences. Second, while the MP intervention provided education about symptom “red flags,” it did not include a structured system (e.g., 24/7 nurse hotline, telemonitoring, clinician home visits) for monitoring, managing, or triaging symptoms after discharge, which appears to be a particularly effective strategy within the ITC framework.15 Direct clinical support was limited primarily to the first week of the intervention (with some exceptions if the nurse provided additional support calls), after which the intervention transitioned from the behavioral health nurse to the community mentors. The combination of initial discussion of red flags, encouragement to seek care proactively (i.e., not only when symptoms became intolerable), and the lack of ongoing symptom monitoring and triage, plus insufficient linkage with outpatient care, may have resulted in increased recurrent hospitalization rates in the MP group. Furthermore, home visits from a healthcare professional were omitted from the current intervention because we sought a cost-effective, sustainable approach, but they are a component of many prior successful studies16 and an effective means of symptom monitoring and management support.15 Finally, although community mentors focused on social determinants, resources in San Diego County were often insufficient to meet housing, food, or transportation needs.

Our study focused on an at-risk population that is affected by adverse social determinants, which can amplify stress and pose barriers to following discharge instructions and obtaining outpatient care. Most participants were born in Mexico, and some may have been ineligible for assistance programs that require residency/citizenship documentation. By comparison, only three trials included in the Cochrane 2022 review16 examined low-income settings.17–19 A Project RED trial conducted in a Boston safety-net hospital found reduced 30-day hospital utilization versus usual care.19 Key differences from MP included pharmacist support and direct connection with outpatient services. Another study examined a “discharge transfer intervention” for medical-surgical patients of a Boston safety-net hospital, but only included patients with primary medical homes within the same system. The study showed improvements in timely outpatient follow-up, but was not powered to examine readmissions.18 A third study examined a language-concordant (English, Spanish, Chinese) self-management intervention delivered to older patients at a San Francisco hospital. Similar to our findings, the study found a non-significant trend toward increased ED visits and readmissions in the intervention group. Investigators speculated that providing information about symptom red flags and medication side effects may have sensitized patients, leading to more ED and hospital stays. As noted above, it is likewise possible that the MP intervention itself prompted patients to return to the hospital more readily, either because they were attuned to symptomatic changes or wished to be proactive and did not have easy access to outpatient care. If present, such effects may have been especially salient in the first 30 days from discharge, when the intervention was conducted, which may account in part for the larger differences between the groups in this timeframe. A full process evaluation of the MP trial is underway and may provide additional insight.

Importantly, although the Cochrane review observed a beneficial effect of care transitions interventions overall, effects were small and not entirely consistent.16 Similar findings have been identified in prior systematic reviews.41–43 Varied approaches are used to improve care transitions, and the field lacks clear consensus regarding the critical “ingredients.” A systematic review by Hansen and colleagues found that the most effective interventions were those focused on multiple aspects of the care transition.44 Another review of the effects of hospital to home care transition interventions on 30-day readmissions rates found that interventions that were more complex, that promoted patient self-care, or that were conducted less recently were more likely to show positive effects.42 The authors speculated that more recent trials were less likely to show that interventions were superior due to the general improvement in usual care discharge processes that has occurred over time. Future research would benefit from applying non-traditional designs, such as a multiphase optimization approach,45 to identify key components and optimal dosages, or risk stratification to identify patients in need of more/less intensive intervention. Moreover, because intervention effectiveness depends on contextual factors beyond the hospital level (e.g., clinician collaboration, outpatient system engagement, patient social determinants, the presence of “post-hospital syndrome” heightening patient vulnerability in the weeks following discharge46), a focus on the discharge process alone may be insufficient. The MP program was theoretically framed in the social-ecological model47 and attempted to address factors at multiple levels, yet encountered barriers related to outpatient integration and availability of community resources.

Limitations

The study may not have captured all readmissions since there are many regional hospitals. Other evolving approaches, such as the use of statewide health information exchanges, may improve ascertainment in future research.48 We did not delineate preventable from nonpreventable readmissions and did not have information on readmission acuity. However, it is likely that these limitations equally affected both groups. Excluding patients discharged to skilled nursing or other care settings may have led to a healthier or younger sample versus the larger population. The final year of the trial was concurrent with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and recruitment was ended early, although statistical power was adequate. Some hospitalizations may have occurred due to COVID-19, but it is likely that this affected both groups. Finally, the results cannot be generalized beyond the study population, site, and geographic region.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates the challenges involved in attempting to improve the care transitions process in an at-risk population. The study also suggests that care transitions interventions can bring unintended consequences. Additional research is needed to determine the specific approaches (e.g., symptom monitoring, home visits, pharmacist support, emphasizing the outpatient side of the transition, refining the education approach around red flags) that are most effective in improving hospital and patient outcomes in these contexts.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants, staff, trainees, interventionists, volunteers, community partners, and community advisory board members who contributed to the Mi Puente research trial.

Funding

The current study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health (NIH/NINR 5 R01 NR015754; Philis-Tsimikas and Gallo, Multiple Principal Investigators). The funding body had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation, or in preparing the manuscript. Additional support was provided by P30 DK111022-02 from the NIH/NIDDK (Gallo, Fortmann), and 1 U54 TR002359-05 from NCATS/NIH (Philis-Tsimikas, Fortmann, Gallo).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with appropriate data use agreement.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunes BP, Flores TR, Mielke GI, Thumé E, Facchini LA. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;67:130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan A, Wallace E, O’Hara P, Smith SM. Multimorbidity and functional decline in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:168. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0355-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPhail SM. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: Impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;9:143–56. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.S97248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin AB, Hartman M, Lassman D, Catlin A. National Health Care Spending In 2019: Steady Growth For The Fourth Consecutive Year. Health Affairs. 2021;40(1):14–24. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Read JR, Sharpe L, Modini M, Dear BF. Multimorbidity and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J, Härter M. Quality of life in medically ill persons with comorbid mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80(5):275–86. doi: 10.1159/000323404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen L, van Schijndel M, van Waarde J, van Busschbach J. Health-economic outcomes in hospital patients with medical-psychiatric comorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmedani BK, Solberg LI, Copeland LA, Fang-Hollingsworth Y, Stewart C, Hu J, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, AMI, and pneumonia. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(2):134–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl T, Katapodis N, Schneiderman S. Care Transitions. In: Hall KK, Shoemaker-Hunt S, Hoffman L, et al. Making Healthcare Safer III: A Critical Analysis of Existing and Emerging Patient Safety Practices [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020 Mar. 15. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555516/. Accessed October 30, 2020. [PubMed]

- 11.Brock J, Jencks SF, Hayes RK. Future directions in research to improve care transitions From Hospital Discharge. Medical Care. 2021;59:S401–S4. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, Salisbury C, Blom J, Freitag M, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: A systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karliner LS, Auerbach A, Nápoles A, Schillinger D, Nickleach D, Pérez-Stable EJ. Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions. Med Care. 2012;50(4):283–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318249c949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang HJ, Boutwell AE, Maxwell J, Bourgoin A, Regenstein M, Andres E. Understanding patient, provider, and system factors related to Medicaid readmissions. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(3):115–21. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(16)42014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke RE, Guo R, Prochazka AV, Misky GJ. Identifying keys to success in reducing readmissions using the ideal transitions in care framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:423. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Lannin NA, Clemson L, Cameron ID, Shepperd S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2022(2). 10.1002/14651858.CD000313.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Goldman LE, Sarkar U, Kessell E, Guzman D, Schneidermann M, Pierluissi E, et al. Support from hospital to home for elders: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(7):472–81. doi: 10.7326/m14-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balaban RB, Weissman JS, Samuel PA, Woolhandler S. Redefining and redesigning hospital discharge to enhance patient care: A randomized controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1228–33. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0618-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge Program to decrease rehospitalization. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150(3):178–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prados-Torres A, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Hancco-Saavedra J, Poblador-Plou B, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity patterns: A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(3):254–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM. State of the Art Review: Depression, Stress, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(11):1295–302. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Groot M, Golden SH, Wagner J. Psychological conditions in adults with diabetes. Am Psychol. 2016;71(7):552–62. doi: 10.1037/a0040408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skinner TC, Joensen L, Parkin T. Twenty-five years of diabetes distress research. Diabet Med. 2020;37(3):393–400. doi: 10.1111/dme.14157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss AJ, Jiang HJ. Overview of Clinical Conditions with Frequent and Costly Hospital Readmissions by Payer, 2018: Statistical Brief #278. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. July 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb278-Conditions-Frequent-Readmissions-By-Payer-2018.jsp. Accessed May 24, 2022. [PubMed]

- 25.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–e639. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000001052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(17):1775–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabassa LJ, Zayas LH, Hansen MC. Latino adults’ access to mental health care: a review of epidemiological studies. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33(3):316–30. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López SR, Barrio C, Kopelowicz A, Vega WA. From documenting to eliminating disparities in mental health care for Latinos. Am Psychol. 2012;67(7):511–23. doi: 10.1037/a0029737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG, Davis D, Escamilla-Cejudo JA. Hispanic health in the USA: A scoping review of the literature. Pub Health Rev. 2016;37(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s40985-016-0043-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman EA, Roman SP, Hall KA, Min SJ. Enhancing the care transitions intervention protocol to better address the needs of family caregivers. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):2–11. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460118.60567.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, Bravin JI, Clark TL, Savin KL, Ledesma DL, et al. My Bridge (Mi Puente), a care transitions intervention for Hispanics/Latinos with multimorbidity and behavioral health concerns: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3722-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell SE, Martin J, Holmes S, van Deusen LC, Cancino R, Paasche-Orlow M, et al. How Hospitals Reengineer Their Discharge Processes to Reduce Readmissions. J Healthc Qual. 2016;38(2):116–26. doi: 10.1097/jhq.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodakowski J, Rocco PB, Ortiz M, Folb B, Schulz R, Morton SC, et al. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: A Metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1748–55. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savage B, Foli KJ, Edwards NE, Abrahamson K. Familism and health care provision to Hispanic older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2016;42(1):21–9. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20151124-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, Christodolou C, Cook K, Hahn EA, et al. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(9):1311–21. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Eakin E. A social-ecologic approach to assessing support for disease self-management: the Chronic Illness Resources Survey. J Behav Med. 2000;23(6):559–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1005507603901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajaguru V, Han W, Kim TH, Shin J, Lee SG. LACE Index to predict the high risk of 30-day readmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med. 2022;12(4). 10.3390/jpm12040545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus. Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mabire C, Dwyer A, Garnier A, Pellet J. Effectiveness of nursing discharge planning interventions on health-related outcomes in discharged elderly inpatients: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(9):217–60. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2016-003085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, Brito JP, Mair FS, Gallacher K, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–107. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Straßner C, Hoffmann M, Forstner J, Roth C, Szecsenyi J, Wensing M. Interventions to Improve Hospital Admission and Discharge Management: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. Qual Manag Health Care. 2020;29(2):67–75. doi: 10.1097/qmh.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:307–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daddato AE, Dollar B, Lum HD, Burke RE, Boxer RS. Identifying patient readmissions: Are our data sources misleading? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(8):1042–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with appropriate data use agreement.