Abstract

Introduction

Emotional support provided by health care professionals (HCPs) for people diagnosed with cancer is associated with improved outcomes. Support via social networks may also be important.

Aims

To report among a sample of distressed patients and caregivers, (1) the importance attributed to different sources of emotional support (HCPs and social networks) by distressed cancer patients and caregivers; (2) the proportion who indicate they did not receive sufficient levels of emotional support; and (3) potential associations between respondents’ demographic and clinical characteristics and reported lack of emotional support.

Methods

This study utilised cross‐sectional data from telephone interviews collected during the usual‐care phase of the Structured Triage and Referral by Telephone (START) trial. Participants completed a telephone interview 6 months after their initial call to the Cancer Council Information and Support service and included recall of importance and sufficiency of emotional support.

Results

More than two‐thirds of patients (n = 234) and caregivers (n = 152) reported that family and friends were very important sources of emotional support. Nurses (69% and 42%) and doctors (68% and 47%) were reported very important, while a lower proportion reported that psychologists and psychiatrists were very important (39%, and 43%). Insufficient levels of support were reported by 36% of participants. Perceptions of insufficient support were significantly associated with distress levels (p < .0001) and not having a partner (p = .0115).

Conclusion

Social networks, particularly family, are an important source of emotional support. Higher levels of distress, those without partners, and caregivers may require targeted interventions to increase their access to emotional support.

Keywords: caregivers, psycho‐oncology, social networks, supportive care, telephone

Short abstract

Emotional support provided by health care professionals (HCPs) and social networks for distressed patients and caregivers affected by cancer may supplement formalised psychological support. People with higher levels of distress, those without partners, and caregivers may require targeted interventions to increase their access to emotional support.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The importance of emotional support for distressed patients’ and caregivers’

When faced with a diagnosis such as cancer, patients and caregivers may need, and seek, support from a variety of sources. 1 Support can address informational, emotional, practical, spiritual, social, and physical needs and may encompass issues such as health promotion and prevention, survivorship, palliation, and bereavement. 2 Emotional support is one form of supportive care, and may be able to assist with shock, confusion, uncertainty, anger, grief, coping, and adjustment post‐diagnosis. 1 , 3 Health care professionals (HCPs) often provide emotional support; for example staff in treatment centers, psychologists, psychiatrists, counsellors and volunteers in community settings. Emotional support is also provided by social networks from friends or family members, work colleagues and pastoral care representatives. 4 , 5 The provision of emotional support is identified as an essential component of patient‐centered care. 6 Social and emotional support for people diagnosed with cancer 7 , 8 , 9 is associated with improved physical and psychological outcomes for patients 10 , 11 and lower mortality rates. 12 Evidence is emerging which shows that caregivers also require social and emotional support. 13 Therefore, it is important to consider the needs and experiences of both patients and caregivers when exploring the various options for providing supportive care.

1.2. Patient centered communication from health care professionals

Research 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 indicates that supportive care interventions delivered by HCPs often take place in a formal and structured format, such as manualised counselling and therapy. However, HCPs may also provide less structured but invaluable emotional support through patient‐centered communication, with this being an important indicator of the quality of care received. 6 , 18 , 19 Nurses can provide support through opportunistic verbal exchanges with patients, including listening to the patient's perspectives and acknowledging the emotional impact. 20 These patient‐centered care principles are likely to be important for caregivers, however, are less well‐researched.

1.3. Social network's role in emotional support

Support for both patients and caregivers via social networks may be received from family members, friends, neighbours, work colleagues and pastoral community members. This type of support from social networks can take many forms. 21 Emotional support received from friends and family in qualitative studies is described as occurring in a “listening capacity” and coming from someone who can share the highs and lows of the caregiving experience. 22 This emotional support is often spoken about at specific time‐points or milestones, such as post‐diagnosis, during active treatment, when receiving results, at follow‐up appointments, after treatment, during palliative stages and after bereavement. 23

Social networks may also assist with practical needs, such as transportation and increased domestic duties, which may require time off from paid work. 24 , 25 , 26 It is widely accepted in the literature that patient outcomes improve with supplementary informal emotional support, which is considered an essential addition to healthcare. 8 , 27 , 28 , 29 However, social network support across multiple activities is difficult to measure, thereby presenting a challenge when attempting to quantify the impact that supplementary emotional support can give. 30 Informal emotional support for caregivers has been studied in less depth than support for patients. 30

One of the challenging features of the supportive care literature is that despite the known need for support, 31 and the evidence that support can be effective, 32 , 33 , 34 the reported use of supportive care services following a referral is low (20–25%). 31 Little is understood about the contributing factors and reasons why this suboptimal uptake occurs. 31 One contributing factor to low levels of professional support service use may be that the required support is being received via social networks or via generalised supportive communication from HCPs. Clover et al. 35 reported that out of 221 significantly distressed cancer patients in an outpatient setting, 71% declined supportive care services, with 24% reporting they were “already receiving help.” While the source of support for this group was not reported, it is possible that some of this support was from the person's social network. Little is known about the relative importance that distressed cancer patients place on the various forms of support.

It is important to understand whether HCPs and social networks (individually or collectively) meet the emotional support needs of patients and caregivers. This study examined the perceived importance attributed to the person who is providing the support, whether sufficient support is provided, and which groups may be more likely to report receiving insufficient emotional support.

1.4. Aims

To report: among a sample of distressed patients and caregivers who called the Cancer Council Information and Support (CIS) service:

The importance attributed to different sources of emotional support (HCPs and social networks);

The proportion of distressed patients and caregivers who indicate they did not receive sufficient levels of emotional support;

Potential associations between respondents’ demographic and clinical characteristics and reported lack of emotional support.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

The START trial is a cluster‐randomized, stepped‐wedge study exploring the effectiveness of structured distress screening and management versus usual care delivered by the Cancer Council Information and Support (CIS) services in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria, Australia. This study used cross‐sectional data collected at 6‐month follow‐up during the usual care phase of the START trial. 36 That is, the data reported here include only those participants who were not exposed to the START trial intervention. Demographic information was collected as part of the 3‐month survey and then matched to participants’ 6‐month data using unique identifiers and a software program (STATA 15.0). 37

2.2. Participants and procedures

Patients and caregivers calling the CIS service in NSW and Victoria were screened for distress by a CIS consultant using the Distress Thermometer (DT), 8 as per standard practice at the time. Callers scoring 4 or more on the DT were identified as distressed and were invited by the CIS consultant to participate in the START trial at the close of the call. The contact details of potential participants were sent to the research team. A research assistant conducted a 30–45 minute computer‐assisted telephone interview (CATI) with participants 6 months after the initial call to the CIS service. The CATI items included the DT, and questions regarding the perceived importance of emotional support from HCPs and social networks, and the sufficiency of emotional support received.

2.3. Demographic characteristics

Caller characteristics of interest included caller type (patient, caregiver), gender (male, female), time since diagnosis (less than 3 months, 3–6 months, 7–12 months, 12 months‐2 years, 2–3 years, more than 3 years), relationship status (married/de facto/living with partner, separated/divorced, widowed, single/never married), remoteness area (metropolitan, non‐metropolitan), stage at diagnosis (metastatic, localised), age and distress thermometer (DT) score at six months post recruitment.

2.4. Measures

Survey items for the CATI were co‐developed with CIS consultants to ensure they covered the variety of psychosocial support options that are commonly discussed with both patients and caregivers, regardless of tumour type or time‐point in the cancer journey (e.g., diagnosis, treatment, surveillance or palliation). This process resulted in a list of eight sources of support across two categories. The first category was HCPs: doctors, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists and counsellors. The second category was social networks: family, friends, work colleagues and pastoral care representatives. The survey items asked: “Thinking about your experience of cancer, how important was emotional support from the following groups of people?” (7 prompted groups: family, friends, work colleagues, pastoral, doctors, nurses, psychologist/psychiatrist); “Were there any groups listed in that last question that you needed emotional support from, but you did not receive it, or did not receive enough support?”; “Which ones (did you not receive support from)?” (8 prompted groups: family, friends, work colleagues, pastoral, doctors, nurses, psychologist/psychiatrist, counsellor). The group of counsellor was added to the “perceived insufficiency of support” question to capture additional avenues for emotional support likely to be accessed by participants calling the CIS service.

Characteristics such as gender, age and caller type were collected in the 3‐month CATI and included in the analysis. Level of distress was collected in the 6‐month CATI.

2.5. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted with the use of statistical software (STATA 15). 37 Proportions and 95% confidence intervals were used to present the data regarding perceived importance and sufficiency of emotional support. A logistic regression model of insufficient support was used to explore associations between perceived insufficient support and caller characteristics using separate crude logistic regressions. Insufficient support was defined as “The participant would have liked more support from one or more of the listed sources of support”. A multivariable logistic regression model was determined that included key predictors variables: age, DT score (at six months after the initial call to the CIS service), caller type, relationship status, remoteness area, and time since diagnosis. Crude odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, number of observations and p‐values were produced. A multivariable model was created using caller characteristics with p < .2 from the crude models included and model selection assessed by Akaike Information Criterion with correction (AICc) measure, as well as pseudo R‐squared values. Adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p‐values were reported. Both crude and adjusted models controlled for CIS state by including the variable as a covariate, while robust standard errors were applied to alleviate any lack of independence.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant characteristics

A sample of 386 patients (n = 234, 60.06%) and caregivers (n = 152, 39.4%) participated. The consent rate for the START trial was 66%, with 67% of eligible consenters completing the 6‐month follow‐up interview. The data presented here relate only to participants recruited during the usual‐care phase of the stepped‐wedge START trial. The demographic characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. Briefly, the mean age of participants was 56 years, with more women than men participating (72%), and most reporting they were within twelve months of an initial cancer diagnosis (72%).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and characteristics of patients and caregivers (n = 386)

| Demographic characteristics | N = 386 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Age* | |||

| Mean | 56.3 µ (SD 13.27) | ||

| Range | 19–88 | ||

| Gender* | |||

| Male | 108 | 28.0 | |

| Female | 277 | 72.0 | |

| Caller type* | |||

| Patient | 234 | 60.6 | |

| Caregiver | 152 | 39.4 | |

| Relationship status* | |||

| Married or de facto | 242 | 62.9 | |

| Widowed | 30 | 7.8 | |

| Separated or divorced | 65 | 16.9 | |

| Single (never married) | 48 | 12.5 | |

| Education | |||

| School (≤ year 12) | 125 | 32.5 | |

| Diploma/ trade certificate | 129 | 33.5 | |

| Bachelor/ post graduate degree | 131 | 34.0 | |

| Income AUD (individual gross) | |||

| < $20 999 | 123 | 31.9 | |

| $21 000 – 41 999 | 85 | 22.0 | |

| $42 000– 64 999 | 56 | 14.5 | |

| $65 000 – 77 999 | 31 | 8.0 | |

| > $78 000 | 61 | 15.8 | |

| Prefer not to say | 30 | 7.8 | |

| Geographical Location* | |||

| Metropolitan | 270 | 70.1 | |

| Non‐metropolitan | 115 | 29.9 | |

| Identify as | |||

| Aboriginal | 11 | 2.9 | |

| Torres Strait Islander | 0 | ||

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 0 | ||

| Distress thermometer score 6 months post recruitment | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.52μ (2.78) | ||

| Median | 5 | ||

| Interquartile range | 5 | ||

| Tumour type † | |||

| Breast | 98 | 25.3 | |

| Colorectal | 52 | 13.5 | |

| Genitourinary | 41 | 10.6 | |

| Head and neck | 40 | 10.4 | |

| Blood | 39 | 10.1 | |

| Lung | 31 | 8.0 | |

| Prostate | 31 | 8.0 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 26 | 6.7 | |

| Melanoma | 10 | 2.6 | |

| Kidney | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Bone | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Other** | 26 | 6.7 | |

| Time since diagnosis* | |||

| <6 months | 178 | 46.7 | |

| 7‐12 months | 96 | 25.2 | |

| 13–24 months | 48 | 12.6 | |

| >24 months | 37 | 9.7 | |

| Not reported | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Stage at diagnosis* | |||

| Localised | 192 | 53.6 | |

| Metastasised | 166 | 46.4 | |

| Not reported or unknown | 28 | 7.3 | |

Some participants reported more than one tumour type.

variables of interest for association.

Other cancer types included Ewings sarcoma, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, adenosarcoma neuroendocrine carcinoma, endocrine, mucinous carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, gallbladder, anal, Mesothelioma, plasmacytoma, peritoneal, polycythemia rubra vera, ductal carcinoma in situ and spine.

3.2. Patients’ and caregivers’ perceived importance of support by source of support

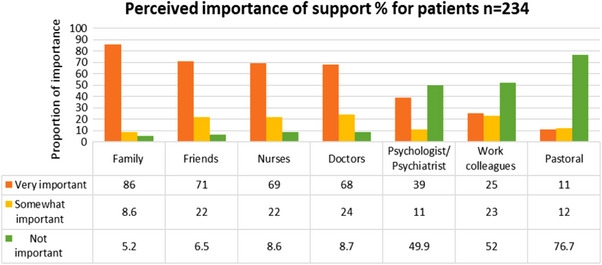

Figure 1 reports the proportion of patients who perceived each type of support as important. Patients commonly reported family support as being very important (86%), followed by friends (71%), nurses (69%) and doctors (68%). Psychology or psychiatry support was perceived to be very important by 39% of patients.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of patients and perceived importance given to each type of support

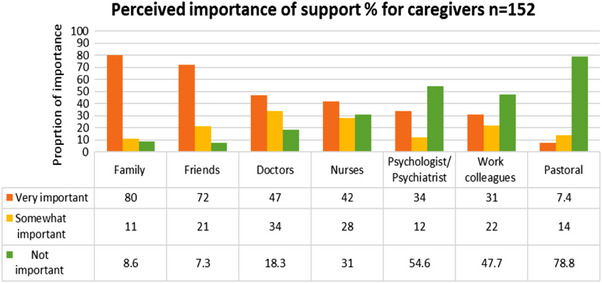

Figure 2 reports the proportion of caregivers who perceived each type of support to be important. Similar to patients’ perceptions, family and friends were perceived to be very important sources of support (80% and 72%, respectively). However, compared to patients, a smaller proportion of caregivers perceived doctors (47%) and nurses (42%) to be very important sources of support.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of caregivers and perceived importance given to each type of support

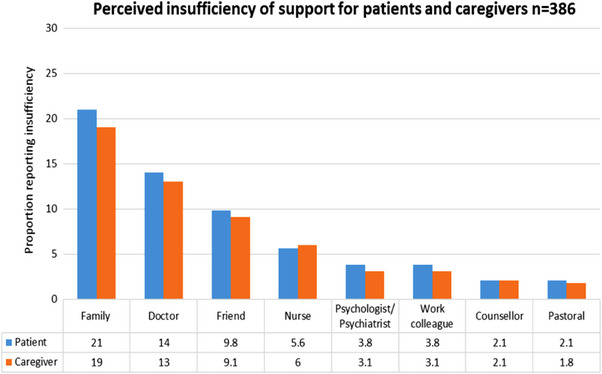

3.3. Patients and caregivers who reported they received insufficient support

Just over one‐third (137/386, 35.8 %) of participants reported that they did not receive sufficient support from at least one of the identified support sources; this was approximately 39% (n = 91) of patients and 30% (n = 46) of caregivers. Figure 3 shows the proportions of patients and caregivers who reported receiving insufficient support from each of eight types of support. The most common source of insufficient support reported by both caregivers and patients was their family (19% and 21%), followed by doctor or friend.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of patients’ and caregivers’ perceived levels of insufficient support by source

3.4. Associations between insufficient support and participant characteristics

Supplementary Table 1 presents corresponding crude odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each logistic regression model of reporting receipt of insufficient emotional support. Insufficient support was defined by the participants’ indicating they would have liked more support from one or more of the listed sources of support.

Overall, the association between DT score and insufficient support was significant (p < .0001) There was a 20.5% increase in the odds of participants reporting they received insufficient support (OR: 1.205; 95% CI: 1.111, 1.308) for each 1 unit increase in the six‐month DT score. This can be interpreted as individuals with increased distress being more likely to report insufficient support than those with a lower DT score. Compared to single (never married) people, participants who were married, de facto or living with partner participants (OR: 0.663; 95% CI: 0.349, 1.260) and participants who were widows (OR: 0.336; 95% CI: 0.115, 0.981) exhibited decreased odds of reporting insufficient support. Previously, assumptions may have been made that participants who were widows would be more akin to un‐partnered people. Conversely, separated or divorced individuals displayed an increase in the odds of insufficient support compared to never married (OR: 1.422; 95% CI: 0.664, 3.047). This association between relationship status and insufficient support was significant (p = .0115). No other associations from individual models were found to be significant (p > .05).

A multivariable logistic regression model was determined that included age, DT score (at six months), caller type, relationship status, remoteness area, and time since diagnosis predictors, while controlling for CIS service state; stage at diagnosis was excluded from the crude analyses since p > 0.2. Gender and stage at diagnosis were removed on the basis of model selection measures. Associations between insufficient support and these identified caller characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Similar to the results of the univariate model, DT score (p < .0001) and relationship status (p = .0093) were significantly associated with overall insufficient support in the multivariable model (Supplementary Table 2). A significant 23.7% increase (OR: 1.237; 95% CI: 1.134, 1.349) in insufficient support odds was exhibited for every unit increase from the mean DT score, when all other variables were held constant. Controlling for all other characteristics, widows (OR: 0.358; 95% CI: 0.110, 1.163) and individuals who were married, de facto or living with their partners had lower odds (OR: 0.679; 95% CI: 0.344, 1.342) of having had insufficient support. Comparatively, single (never married) participants and separated or divorced people exhibited higher odds (OR: 1.631; 95% CI: 0.730, 3.641). No significant associations were evident for age, caller type, remoteness area, or time since diagnosis at p > .05.

4. DISCUSSION

This study provides new data regarding the variety of sources of emotional support and gaps in the receipt of emotional support, as experienced by a broad group of distressed patients and caregivers. Eighty percent or more of patients and caregivers reported that family and friends were very important sources of emotional support. More than 70% of both patients and caregivers reported that friends were very important sources of emotional support. More than two‐thirds of patients reported that nurses and doctors were very important sources of emotional support, while a little less than half of caregivers reported these sources as very important. Psychologists and psychiatrists were perceived as important sources of support by a minority of both patients (39%) and caregivers (34%), supporting the view that professional emotional support is not front of mind for most patients and caregivers, even those deemed to have moderate or high levels of distress.

It appears that social networks are critical sources of emotional support, specifically, family and friends. Interactions with social networks, by nature, are less formal and often result in spontaneous exchanges which differ from more structured support received from mental health professionals such as psychologists. This study indicates that HCPs who are not psychologists or psychiatrists have an important role to play in providing emotional support for many patients. Arora et al. 5 found that while breast cancer patients reported receiving helpful emotional support from family (85%), friends (80%), and HCPs (67%) close to their time of diagnosis, the receipt of helpful support reduced significantly within the first year. 5 Although our study did not find an association between time since diagnosis and participants’ reporting insufficient support, taken together these studies strongly suggest that both HCPs and social networks are valuable and necessary in providing emotional support. The data from this study also raise the question of whether the research focus on formal support programs delivered by mental health professionals 17 , 38 and trained peers 39 , 40 is somewhat narrow in its scope. It may be beneficial to direct greater attention toward enabling family, friends, doctors and nurses to increase their existing levels of emotional support.

One‐third of participants reported receiving insufficient support from at least one of the identified potential support sources. Family members, doctors and friends were the sources of support most frequently reported as providing insufficient emotional support to meet the participants’ needs. Patients and caregivers very often do not action supportive care referrals. 35 , 41 {Wilson, 2021 #50} Dilworth et al. 42 systematically reviewed 25 papers (22 with patients) and reported that 38.77% of patients indicated they did not perceive they had a need for psychosocial support. The review did not report the reason for such perception, nor did it address whether sufficient support was already being received. In comparison, an Australian single‐site study of 311 distressed outpatients found that 71% declined support due to a desire to manage things independently (46%), “already receiving help” (24%) or a perception that their distress was not “bad enough” (23%). 35 The data presented here do not directly support the view that a desire for support from family or friends necessarily means that it will be received. The results suggest that improving the capacity of friends, family and doctors to provide emotional support is warranted. The study data also suggest that doctors and nurses have an important role in providing emotional support in oncology settings—particularly for patients—and therefore, may potentially benefit from review of their supportive communication skills. Hack et al. 43 reports that 5% of the consultation time in radiation oncology with prostate cancer patients was spent on psychosocial content, and this was found to be insufficient. Moore et al. suggest that training to mitigate this warrants targeted communication skills training for HCPs. 44

The finding that a higher level of distress and being non‐partnered was associated with a greater likelihood of reporting insufficient emotional support accords with the wider research on vulnerable groups. For example, non‐partnered people are reported to be more vulnerable both physically and emotionally, particularly if living alone. 45 Targeted interventions and development of community programs are recommended to reduce this burden. 46 This study aligns with these findings, suggesting that HCPs’ role in emotional support may be especially heightened for these individuals. The association between distress and reporting of insufficient support indicates that distress screening remains important for delivering patient‐centered care, and endorses the need to continue to study the effectiveness of strategies for meeting this need.

The study data further raise the question of whether patients’ and caregivers’ interactions with HCPs and social networks may be different. Patients’ needs may be more evident than those of caregivers, who are not directly assessed for their needs at a system level. Lambert et al. report the need for including caregivers in supportive care, assessing the impact of caregiving and prioritising the future steps needed to mitigate this burden. 47 Caregivers may indeed rely less on HCPs for emotional support than patients. Therefore, understanding whether social networks are an underutilised avenue of emotional support for caregivers should be explored. Targeted information provision to these networks may increase the likelihood of social networks’ ability to offer higher levels of emotional support to those in need. Patients and caregivers may benefit from assistance in articulating their needs and navigating access to the support they desire from friends and family. Conversely, members of these social networks may be influenced by campaigns or tools which assist them to understand the need for and provide the kinds of support that are desired from them. Greater understanding of the impact social networks may play in lightening the burden of cancer care is warranted.

4.1. Limitations

Participants recruited for this study were people affected by cancer who actively sought help from a helpline and may not be representative of the broader cancer population. The study is reliant upon self‐reported recall over some months, which may have introduced recall bias. Self‐report data may reflect under‐reporting of support provision or distress levels due to the time lapse between the events being recalled and the telephone interview. Half of the sample were within 6 months of diagnosis and three quarters of the sample were within 1 year of diagnosis. It is possible that participants may still have been undergoing and or suffering from the late effects of treatment. The survey differed in response options, and this inconsistency was a limitation in analysis. Further study regarding Indigenous Australians, culturally and linguistically diverse people and non‐trial participants is necessary, as this sample contained very few of these participants. Therefore, the results from this study should be interpreted with the acknowledgement of these potential limitations.

5. CONCLUSION

Family is a vitally important source of emotional support for patients and caregivers. The weight of importance of emotional support from HCPs and social networks differs a little between patients and caregivers but is important for both. This knowledge may assist targeted promotions focusing on the importance of additional and supplementary forms of emotional support provided by social networks; specifically, it should be targeted towards patients and caregivers with higher levels of distress, and non‐partnered individuals. Understanding the importance of social networks and the role they play in emotional support may lead to broader inclusion of a larger social community to jointly offer supportive care to those affected by cancer.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jo Taylor, Elizabeth A. Fradgley, Tara Clinton‐McHarg, and Christine L. Paul contributed to the study conception and research question. Jo Taylor conducted the data collection, extraction, and coding. Analysis was conducted by Jo Taylor and an independent statistical service. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jo Taylor and Elizabeth A. Fradgley, Tara Clinton‐McHarg, Alix Hall, and Christine L. Paul commented on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest or funding disclosure associated with this work.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Ethical approval for use of this data was granted by the University of Newcastle (HREC H‐2016‐0180), Cancer Council New South Wales (HREC‐304), and Victoria (HREC‐1605) human research ethics committees. The study has been approved by the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (NHMRC Committee Code: EC00144; Reference No. H‐2016‐0180).

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been funded by two competitive grants from the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour and the Hunter Cancer Research Alliance, and statistical support funding from the Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour. These data are drawn from a National Health and Medical Research funded partnership project with the University of Newcastle, Cancer Council New South Wales and Cancer Council Victoria. This research was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Partnership Project Grant, Cancer Council NSW and Cancer Council Victoria. E. Fradgley is supported by a Cancer Institute New South Wales Early Career Research Fellowship. The research team receives infrastructure support from the Hunter Medical Research Institute and support from the Hunter Cancer Research Alliance (HCRA). HCRA receives funding from the Cancer Institute NSW to operate as a Translational Cancer Research Centre in partnership with the University of Newcastle, Hunter Medical Research Institute, Hunter New England Local Health District and Calvary Mater Newcastle. The generous contributions of the study participants and Cancer Council 13 11 20 staff are gratefully acknowledged. The assistance of Jack Faulkner with statistical analysis is also gratefully acknowledged.

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Newcastle, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Newcastle agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Taylor J, Fradgley EA, Clinton‐McHarg T, Hall A, Paul CL. Perceived importance of emotional support provided by health care professionals and social networks: Should we broaden our focus for the delivery of supportive care?. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2023;19:681–689. 10.1111/ajco.13922

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to ethical approvals, these data are not publicly available.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fitch M. Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2008;18(1):6‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26(4):372‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zabora JR, Blanchard CG, Smith ED, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress among cancer patients across the disease continuum. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1997;15(2):73‐87. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Regan T, Levesque JV, Lambert SD, Kelly B. A qualitative investigation of health care professionals’, patients’ and partners’ views on psychosocial issues and related interventions for couples coping with cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R, Hawkins RP. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):474‐486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barry MJ, Edgman‐Levitan S. Shared decision making ‐ the pinnacle of patient‐centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780‐781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Bultz BD. Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, in lung cancer patients: effects on pain, fatigue, and common problems—secondary outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1880‐1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holland JC, Bultz BD. The NCCN guideline for distress management: a case for making distress the sixth vital sign. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2007;5(1):3‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howell D, Mayo S, Currie S, et al. Psychosocial health care needs assessment of adult cancer patients: a consensus‐based guideline. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(12):3343‐3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLachlan KJJ, Gale CR. The effects of psychological distress and its interaction with socioeconomic position on risk of developing four chronic diseases. J Psychosom Res. 2018;109:79‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stewart‐Brown S, Emotional wellbeing and its relation to health: physical disease may well result from emotional distress British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7173):1608‐1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uchino BN. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a life‐span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4(3):236‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Given BA, Sherwood P, Given CW. Support for caregivers of cancer patients: transition after active treatment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):2015‐2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Livingston PM, Craike MJ, White VM, et al. A nurse‐assisted screening and referral program for depression among survivors of colorectal cancer: feasibility study. Med J Aust. 2010;193:S83‐7. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marcus AC, Garrett KM, Kulchak‐Rahm A, Barnes D, Dortch W, Juno S. Telephone counseling in psychosocial oncology: a report from the cancer information and counseling line. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(4):267‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zwahlen D, Tondorf T, Rothschild S, Koller MT, Rochlitz C, Kiss A. Understanding why cancer patients accept or turn down psycho‐oncological support: a prospective observational study including patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on communication about distress. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chambers SK, Girgis A, Occhipinti S, et al. A randomized trial comparing two low‐intensity psychological interventions for distressed patients with cancer and their caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(4):E256‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J, Hobbs K, Kirsten L. Positive and negative interactions with health professionals: a qualitative investigation of the experiences of informal cancer carers. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(6):E1‐E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bureau of Health Information . Patient Perspectives ‐ How do outpatient cancer clinics perform? Bureau of Health Information; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kristiansen M, Tjørnhøj‐Thomsen T, Krasnik A. The benefit of meeting a stranger: experiences with emotional support provided by nurses among Danish‐born and migrant cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(3):244‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mor V, Guadagnoli E, Rosenstein R. Cancer patients' unmet support needs as a quality of life indicator. Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life. Osoba D. CRC Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Griffiths J, Ewing G, Rogers M. “Moving Swiftly On.” Psychological support provided by district nurses to patients with palliative care needs. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(5):390‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balfe M, Keohane K, O'brien K, Sharp L. Social networks, social support and social negativity: a qualitative study of head and neck cancer caregivers' experiences. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26(6):e12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E, et al. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2012:000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C. The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychooncology. 2011;20(4):387‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livingston PM, Osborne RH, Botti M, et al. Efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of an outcall program to reduce carer burden and depression among carers of cancer patients [PROTECT]: rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Skarstein J, Aass N, Fosså SD, Skovlund E, Dahl AA. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: relation between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(1):27‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Starr JM, Kivimäki M, Batty GD. Association between psychological distress and mortality: individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 2012;345:e4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Groot JM, Mah K, Fyles A, et al. Do single and partnered women with gynecologic cancer differ in types and intensities of illness‐ and treatment‐related psychosocial concerns? A pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(3):241‐245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frambes D, Given B, Lehto R, Sikorskii A, Wyatt G. Informal caregivers of cancer patients: review of interventions, care activities, and outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2017;40(7):1069‐1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Funk R, Cisneros C, Williams RC, Kendall J, Hamann HA. What happens after distress screening? Patterns of supportive care service utilization among oncology patients identified through a systematic screening protocol. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):2861‐2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heckel L, Fennell KM, Reynolds J, et al. Efficacy of a telephone outcall program to reduce caregiver burden among caregivers of cancer patients [PROTECT]: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Howell D, Sussman J, Wiernikowski J, et al. A mixed‐method evaluation of nurse‐led community‐based supportive cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(12):1343‐1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Livingston PM, White VM, Hayman J, Maunsell E, Dunn SM, Hill D. The psychological impact of a specialist referral and telephone intervention on male cancer patients: a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2010;19(6):617‐625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clover KA, Mitchell AJ, Britton B, Carter G. Why do oncology outpatients who report emotional distress decline help. Psychooncology. 2015;24(7):812‐818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fradgley EA, Boltong A, O'Brien L, et al. Implementing systematic screening and structured care for distressed callers using Cancer Council's telephone services: protocol for a randomized stepped‐wedge trial. JMIR Research Protocols. 2019;8(5):e12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stata Corporation . Stata Statistical Software: release 15 College Station. StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Semple C, Parahoo K, Norman A, McCaughan E, Humphris G, Mills M. Psychosocial interventions for patients with head and neck cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu J, Wang X, Guo S, et al. Peer support interventions for breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;174(2):325‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gotay CC, Moinpour CM, Unger JM, et al. Impact of a peer‐delivered telephone intervention for women experiencing a breast cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):2093‐2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ernst J, Faller H, Koch U, et al. Doctor's recommendations for psychosocial care: frequency and predictors of recommendations and referrals. PLoS One. 2018;13(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dilworth S, Higgins I, Parker V, Kelly B, Turner J. Patient and health professional's perceived barriers to the delivery of psychosocial care to adults with cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23(6):601‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hack TF, Ruether JD, Pickles T, Bultz BD, Chateau D, Degner LF. Behind closed doors II: systematic analysis of prostate cancer patients' primary treatment consultations with radiation oncologists and predictors of satisfaction with communication. Psychooncology. 2012;21(8):809‐817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moore PM, Rivera S, Bravo‐Soto GA, Olivares C, Lawrie TA. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Müller F, Hagedoorn M, Tuinman MA. Chronic multimorbidity impairs role functioning in middle‐aged and older individuals mostly when non‐partnered or living alone. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Srugo SA, Jiang Y, de Groh M, At‐a‐glance‐Living arrangements and health status of seniors in the 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: research, Policy and Practice. 2020;40(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lambert SD, Brahim LO, Morrison M, et al. Priorities for caregiver research in cancer care: an international Delphi survey of caregivers, clinicians, managers, and researchers. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):805‐817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical approvals, these data are not publicly available.