Abstract

Objectives

In ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), time delay between symptom onset and treatment is critical to improve outcome. The expected transport delay between patient location and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centre is paramount for choosing the adequate reperfusion therapy. The “Centro” region of Portugal has heterogeneity in PCI assess due to geographical reasons. We aimed to explore time delays between regions using process mining tools.

Methods

Retrospective observational analysis of patients with STEMI from the Portuguese Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes. We collected information on geographical area of symptom onset, reperfusion option, and in-hospital mortality. We built a national and a regional patient's flow models by using a process mining methodology based on parallel activity-based log inference algorithm.

Results

Totally, 8956 patients (75% male, 48% from 51 to 70 years) were included in the national model. Most patients (73%) had primary PCI, with the median time between admission and treatment <120 minutes in every region; “Centro” had the longest delay. In the regional model corresponding to the “Centro” region of Portugal divided by districts, only 61% had primary PCI, with “Guarda” (05:04) and “Castelo Branco” (06:50) showing longer delays between diagnosis and reperfusion than “Coimbra” (01:19). For both models, in-hospital mortality was higher for those without reperfusion therapy compared to PCI and fibrinolysis.

Conclusion

Process mining tools help to understand referencing networks visually, easily highlighting its inefficiencies and potential needs for improvement. A new PCI centre in the “Centro” region is critical to offer timely first-line treatment to their population.

Keywords: Big data analytics, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, clinical pathways, process mining tools

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death worldwide1 including Portugal (29.4% of mortality), with acute myocardial infarction responsible for 4.1%.2

There is a growing interest in the optimization of healthcare by establishing standardized protocols, the so-called critical pathways3 that allow the integration of detailed information about patients in the health system, highlighting inefficiencies, to decrease resource utilization and costs, reduce variation and improve quality of care.3 Pattern recognition technologies facilitate the process of design and development of those clinical pathways in real-world, by using process mining technologies,4 a question-driven approach that uses clinical databases and machine learning technologies to infer and analyse flows in a human-understandable manner.5 It has been applied in medicine, namely in cardiovascular emergencies.6

In ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the treatment of choice is primary percutaneous coronary intervention (P-PCI) provided it can be performed shortly after symptom onset. Maximum time delay from STEMI diagnosis (time of ECG) to P-PCI in patients presenting at PCI-capable centres should be <60 minutes. For patients presenting at a non-PCI-capable centre, the expected delay between diagnosis, transport, and P-PCI must be considered. If it exceeds 120 minutes, a pharmacological treatment (fibrinolysis) should be chosen instead of P-PCI; otherwise, the time target in transferred patients to P-PCI is <90 minutes.7

The Portuguese Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (ProACS) reported a reduction of in-hospital mortality in the last decade, without significant improvements in target timings,8 and another national study reported that both central region of Portugal and admission at a non-PCI centre were predictors of delay.9

We hypothesize that the worse results in the central region of Portugal are explained by geographical variations that influence access to PCI centres, increasing treatment delay and mortality. We aimed to analyse the impact of distance to PCI centres in STEMI by using process mining tools.

Materials and methods

The ProACS is a prospective observational registry started in 2002, coordinated by the Centro Nacional de Coleção de Dados em Cardiologia (CNCDC) that collects information on acute coronary syndromes, including demographics, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, timings (including symptom onset and time to P-PCI or fibrinolysis), treatment options (P-PCI, fibrinolysis or no reperfusion) and mortality outcomes. This database is approved by the Comissão Nacional de Protecção de Dados (n° 3140/2010) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it is registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 01642329).

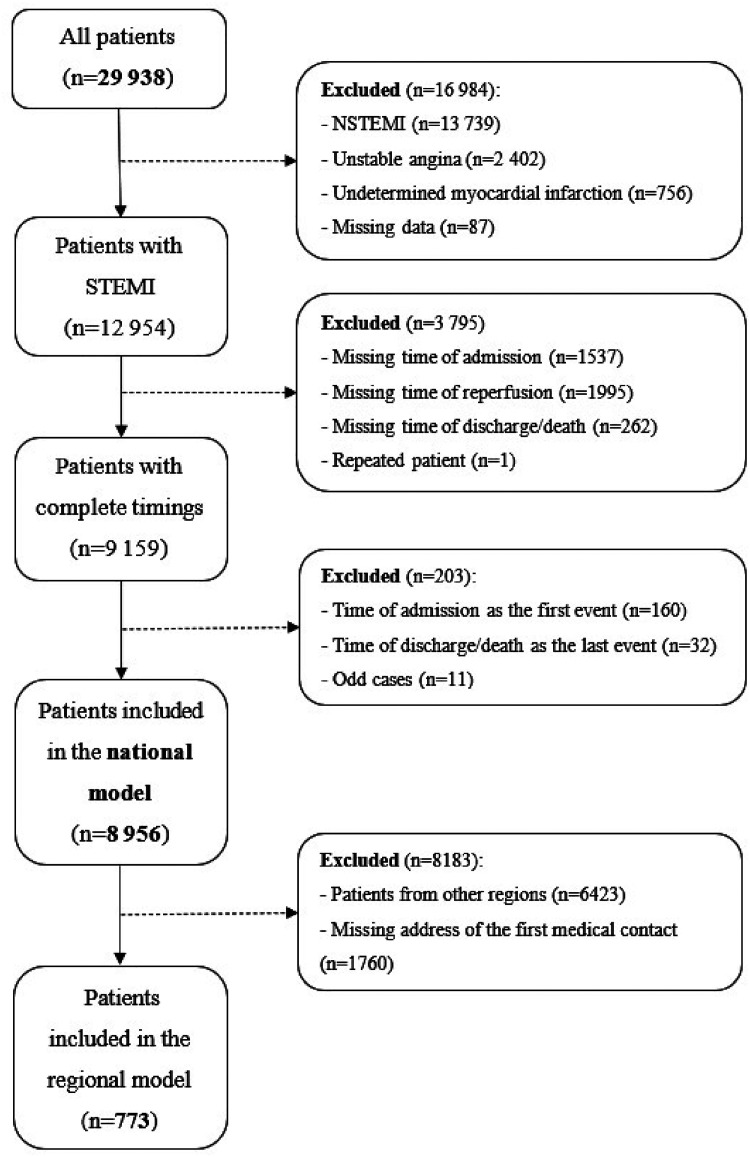

After formal permission granted by CNCDC, we retrospectively assessed 29,939 patients from October 2010 to September 2019. Mandatory inclusion criteria were STEMI diagnosis and complete timing information regarding admission, reperfusion procedure and outcome (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion flowchart.

We used the parallel activity-based log inference algorithm (PALIA) available on a Process Mining tool (PMApp)6 to build models that represent the flow of patients in a healthcare system. PALIA10 is a process mining discovery algorithm that uses grammar inference techniques for inferring timed parallel automatons,11 by considering the start and end of the events as well as their results in their inference. PMApp is an application specifically designed for process mining in healthcare.12 Models are created as graphs where activities are represented as nodes and the transitions (timing between activities) as arrows connecting two nodes. Each activity or transition contains the start and end timings so the model can compute statistics on the duration of activities and transitions. Besides being fully adjustable, it allows the application of filters and enhancement maps through colour gradients. To feed the PALIA algorithm, each patient record was converted into a set of log entries. Each activity (admission, treatment, and outcome) was registered as a log entry with start and end timings and type, as well as patient characteristics. We assumed instant duration for the activities, so the start and end timings were set as equal. This way, timings are only considered for the transitions (arrows) of the models. The total set of entries is compiled in a comma separated values (CSV) file that is then processed by the PMApp.

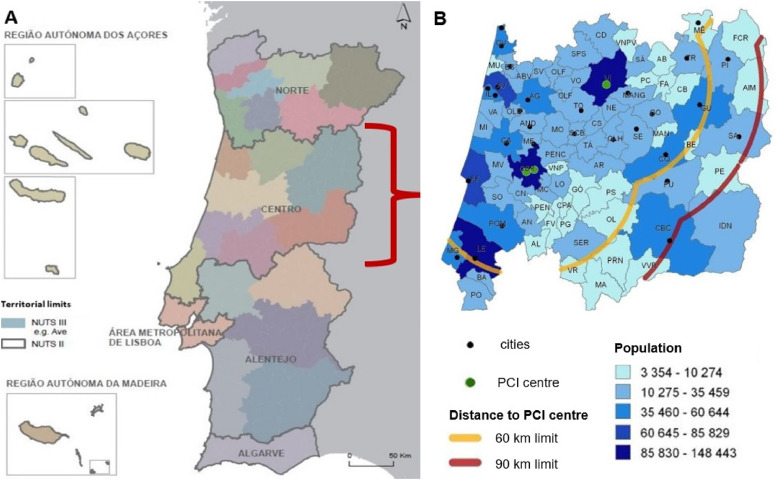

We draw a national model by grouping patients by region of origin, since every patient of the database is registered by the local of hospitalization, according to the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS II),13 as “Açores”, “Norte”, “Centro”, “Lisboa”, “Alentejo”, “Algarve” and “Madeira” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) The seven regions of Portugal, according to NUTS II (adapted with permission from: Instituto Nacional de Estatística, IP – Portugal)13; (B) the “Centro” region, with PCI centres identified by green dots (“Leiria’s” P-PCI centre not portrayed) and cities represented as black dots; locations distancing more than 60 km (yellow line) or 90 km (red line) from PCI centres (adapted with permission from “Proposta de atualização da Rede de Referenciação de Cardiologia, elaborada pelo Programa Nacional para as Doenças Cérebro-Cardiovasculares da Direção-Geral da Saúde e aprovada pelo Exmo Sr. Ministro da Saúde, Dr Fernando Leal da Costa em 02/11/2015”).14

To identify differences between “Centro” and the national scenario, we built a regional model, based on the local of the first medical contact and according to the Portuguese network of referencing in cardiology. We grouped patients by the district of origin as “Aveiro”, “Castelo Branco”, “Coimbra”, “Guarda”, “Leiria” and “Viseu”.

The remaining flow was common for both models: each region/district was connected with one of three treatment options (P-PCI, fibrinolysis and no reperfusion), and then linked to an outcome (discharge or death). We also applied gender, age group and Killip–Kimball (KK) classification filters. The KK classification is used in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction for the purpose of risk stratification, with increasing mortality from class 1 (no heart failure) to class 4 (presentation in cardiogenic shock).15

Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were employed to assess the normality of the data. Since normality was not observed for some variables (p < 0.05), we resort to non-parametric tests for the remaining analysis. For categorical data (demographic and clinical data, regions, treatment and outcome), we used the Chi-squared test to check independence between variables, whilst for continuous data (time to treatment) the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Post hoc analyses were conducted, correcting for multiple comparisons using the Tukey–Kramer method, which rejects the null hypothesis whenever

| (1) |

where represents the statistical threshold set at 5%, k is the number of groups, N is the number of samples and the ()th percentile of the studentized range distribution with parameter k and N − k degrees of freedom. We ran the statistical analysis on the Matlab R2020a software (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics for both models are depicted in Table 1. Patients from the regional model were older, χ2(5, N = 9727) = 15.04, p = 0.01, and more severe (higher KK classification), χ2(3, N = 9439) = 14.43, p < 0.01, but there was no gender difference between models, χ2(1, N = 9729) = 1.12, p = 0.29.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| National model | Regional model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 8958 | P-PCI (%) | Death (%) | n = 773 | P-PCI (%) | Death (%) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 6757 (75.0%) | 74.0 | 4.0 | 570 (74.0%) | 62.0 | 5.0 |

| Female | 2199 (25.0%) | 68.0 | 9.0 | 203 (26.0%) | 60.0 | 13.0 |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤50 | 1505 (17.0%) | 80.0 | 0.6 | 110 (14.0%) | 68.0 | 0.9 |

| 51–60 | 2131 (24.0%) | 78.0 | 2.0 | 167 (22.0%) | 63.0 | 1.0 |

| 61–70 | 2189 (24.0%) | 75.0 | 4.0 | 195 (25.0%) | 66.0 | 6.0 |

| 71–80 | 1922 (21.0%) | 66.0 | 7.0 | 162 (21.0%) | 56.0 | 9.0 |

| ≥81 | 1209 (14.0%) | 63.0 | 15.0 | 139 (18.0%) | 54.0 | 19.0 |

| KK classification | ||||||

| I | 7399 (83.0%) | 76.0 | 2.0 | 604 (78.0%) | 64.0 | 3.0 |

| II | 732 (8.0%) | 69.0 | 11.0 | 84 (11.0%) | 59.0 | 15.0 |

| III | 198 (2.0%) | 60.0 | 18.0 | 18 (2.0%) | 39.0 | 22.0 |

| IV | 358 (4.0%) | 64.0 | 42.0 | 46 (6.0%) | 48.0 | 30.0 |

| NA | 269 (3.0%) | NA | NA | 21 (3.0%) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: KK: Killip–Kimball; NA: not applicable; P-PCI; primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

National perspective

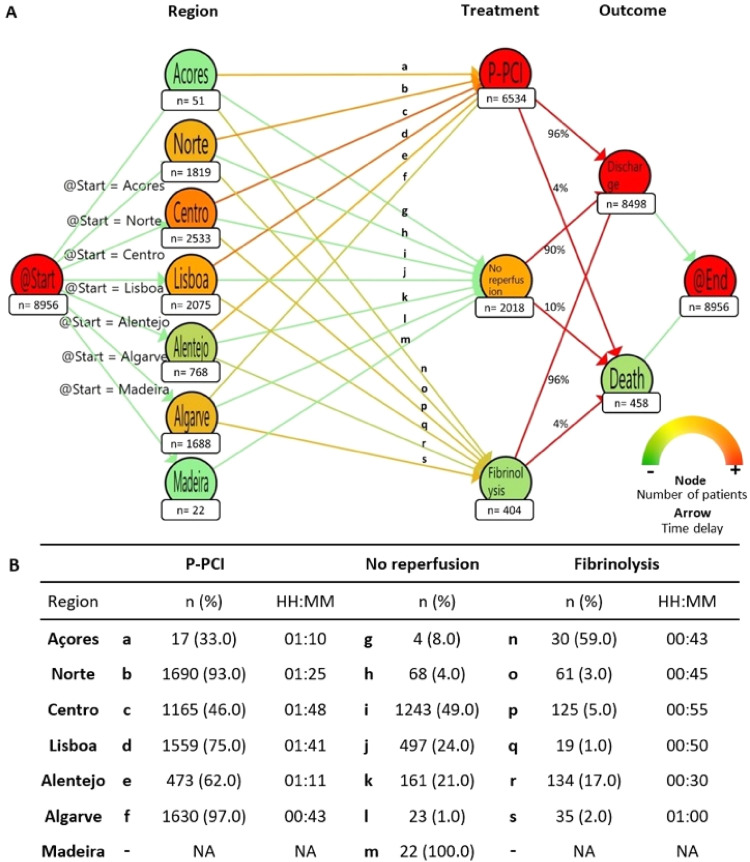

The national model (Figure 3) included 8958 patients, mostly males (75%), belonging to age groups 51–60 (24%) and 61–70 (24%) years old, with most subjects corresponding to KK I (83%), and only 4% to KK IV (Table 1). Most of patients belonged to “Centro” (28%), “Lisboa” (23%), and “Porto” (20%), while “Madeira” (0.6%) and “Açores” (0.2%) were the most underrepresented regions.

Figure 3.

(A) National model: patients’ paths according to region of origin. Colour gradient (bottom, right) in nodes changes from green to red, representing the number of patients in each node, with green demonstrating lower number of patients, while red shows the opposite. Colour gradient in arrows changes from green to red, representing median time between two nodes, with red demonstrating higher duration, while green shows shorter median time delays. (B) Absolute and relative number of each region, regarding treatment option and its time delay. Letters from “a” to “s” represent arrows depicted in the panel (A), linking each region to the treatment chosen; for each one is mentioned the absolute and relative number of patients, as the time delay between nodes. Abbreviations: HH:MM: hours:minutes; NA: not applicable; P-PCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

There were significant differences regarding the preferred treatment according to regions, χ2(12, N = 8958) = 2709, p < 0.01. Globally P-PCI was the treatment of choice (73%): “Algarve” (97%) and “Norte” (93%) had the highest rates of P-PCI, followed by “Lisboa” (75%) and “Alentejo” (62%), while “Centro” (46%) and “Açores” (33%) had the lowest rates. The median time between admission and P-PCI was <120 minutes in every region, but differed significantly between regions, H(5) = 577.5, p < 0.01. The lowest delay was in “Algarve” (00:43), followed by “Açores” (01:10), “Alentejo” (01:11) and “Norte” (01:25). The longer delay was in “Lisboa” (01:41) and “Centro” (01:48). Post hoc analysis showed significant longer delay between either “Coimbra” and “Lisboa” and the remaining regions (p < 0.01, except “Açores”).

In the national model, 23% of patients underwent conservative management (no P-PCI or fibrinolysis), including 49% from “Centro”, 24% from “Lisboa”, and 21% from “Alentejo”. In this sample, “Madeira” did not include patients submitted to P-PCI or fibrinolysis.

Fibrinolysis was performed in 4.5%, mainly in “Açores” (59%) and “Alentejo” (17%). The remaining regions had fibrinolysis in <5%. The median time delay ranged between 30 minutes (“Alentejo”) and 1 hour (“Algarve”), with statistically significant differences across regions, H(5) = 22.19, p < 0.01. Post hoc analysis showed significant differences between “Alentejo” and both “Algarve” (difference: +30 minutes, p = 0.05) and “Centro” (difference: +25 minutes, p < 0.01).

In the national model, total in-hospital mortality was 5%. Mortality was similar in those treated with P-PCI and fibrinolysis but higher for those without reperfusion therapy (4% vs. 4% vs. 10%; χ2(2, N = 8956) = 118.67, p < 0.01). Post hoc analysis showed differences between no reperfusion and both P-PCI (difference: −7.14%, p < 0.01) and Fibrinolysis (difference: −6.28%, p < 0.01).

Regional perspective

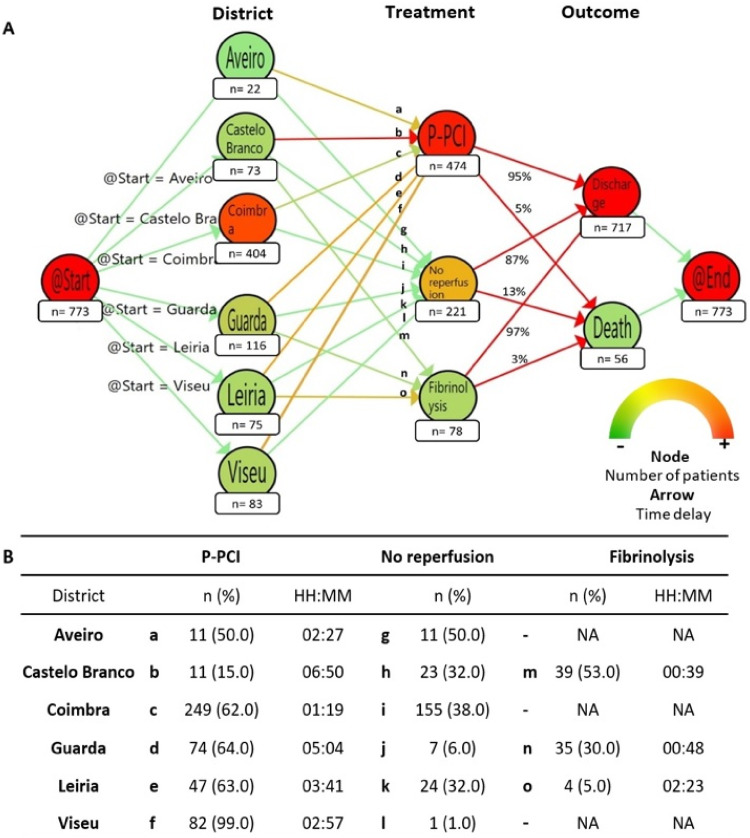

The regional model (Figure 4) included 773 patients, mostly males (74%) between the ages of 61 and 70 (25%) years. The majority of subjects was in KK I (78%), and only 6% in KK IV (Table 1). Most belonged to the “Coimbra” district (52%), followed by “Guarda” (15%), “Viseu” (11%), “Leiria” (10%), “Castelo Branco” (9%), and “Aveiro” (3%).

Figure 4.

(A) Regional model: patients’ paths according to region of origin. Colour gradient (bottom, right) in nodes changes from green to red, representing the number of patients in each node, with green demonstrating lower number of patients, while red shows the opposite. Colour gradient in arrows changes from green to red, representing median time between two nodes, with red demonstrating higher duration, while green shows shorter median time delays. (B) Absolute and relative number of each region, regarding treatment option and its time delay. Letters from “a” to “o” represent arrows depicted in the panel (A), linking each region to the treatment chosen; for each one is mentioned the absolute and relative number of patients, as the time delay between nodes. Abbreviations: HH:MM: hours:minutes; NA: not applicable; P-PCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

There were significant differences regarding the preferred treatment, χ2(10, N = 773) = 340.31, p < 0.01. P-PCI was the treatment of choice in 61% of patients, including almost all patients from “Viseu” (99%). “Guarda” (64%), “Leiria” (63%) and “Coimbra” (62%), had similar rates of P-PCI, while “Castelo Branco” 15%. The median time between admission and P-PCI differed significantly between districts, H(5) = 150.61, p < 0.01. It was the lowest in “Coimbra” (01:19), followed by “Aveiro” (02:27). Patients from “Viseu” (02:57), “Leiria” (03:41), “Guarda” (05:04) and, “Castelo Branco” (06:50) had longer time delays. Post hoc analysis showed significant delay (p < 0.001) between “Coimbra” and the remaining districts, but also between “Viseu” and “Castelo Branco” (p = 0.04).

In the regional model, 29% of patients underwent conservative management, including half of the subjects from “Aveiro” and almost a third from “Coimbra”, “Castelo Branco” and “Leiria”.

Fibrinolysis was chosen in 10% of patients, mostly in “Castelo Branco” (53%), followed by “Guarda” (30%), and “Leiria” (5%), but none in the remaining districts. The median time between admission and fibrinolytic injection differed significantly between regions, H(2) = 6.35, p = 0.04. It was of 39 minutes in “Castelo-Branco”, and 48 minutes in “Guarda”, but it took more than 2 hours in “Leiria”. Post hoc analysis showed significant difference between “Castelo Branco” and “Leiria” (p = 0.03).

In the regional model, there was a total of 56 deaths (7%). Patients that had PCI or fibrinolysis had similar death rates while those patients without reperfusion had higher mortality (5% vs. 3% vs. 13%; χ2(2, N = 773) = 14.41, p < 0.01). Post hoc analysis showed differences between no reperfusion and both P-PCI (p < 0.01) and fibrinolysis (p = 0.01).

Discussion

In the first literature report on the application of process mining tools in STEMI management, we found significant disparities in the treatment of this life-threatening disease according to geographical regions and we identified a potential location for a new primary P-PCI centre to overcome those inequities in healthcare access.

The incidence of STEMI increases with age, occurring more frequently in men.16 Accordingly, the national model was mostly composed by males and older patients from the age group between 51 and 80 years, in line with previous studies.17 We found an increased in-hospital mortality across KK levels, similarly to reports in the P-PCI era.18 Regarding the regional model, most patients were male, from the age group 61 to 70 years, with higher rate in KK IV and less in the KK I, suggesting increased severity for patients from “Centro”.

Most patients of the national model belonged to “Centro” (28.3%), “Lisboa” (23.2%) and “Norte” (20.3%). Patients from “Algarve” represented 18.9%, while the remaining regions had lower representation (“Alentejo” 8.6%, “Açores” 0.6% and “Madeira” 0.2%). This distribution differs from the 2011's Portuguese census, which found “Norte” as the most populated region (34.9%), followed by “Lisboa” (26.7%), “Centro” (22.0%) and “Alentejo” (7.8%), while “Algarve” only represented 4.3%. Also, “Madeira” and “Açores” showed higher representativeness, 2.5% and 2.3%, respectively.19 Moreover, in a previous study with data from ProACS, the majority of STEMI patients belonged to “Lisboa” (43.6%) and “Norte” (37.7%), followed by “Coimbra” (9.1%), “Algarve” (5.8%) and “Alentejo” (3.7%).20 Thus, our model might underestimate “Lisboa”, “Norte”, “Madeira” and “Açores”, while overestimating “Centro” and “Algarve.

P-PCI is the cornerstone of therapy for the management of STEMI. In the National Model, we found that P-PCI was the preferred treatment. This corroborates a study from the ProACS that reported an increase in the rate of reperfusion in STEMI over the last 15 years, mainly by primary P-PCI, associated with a reduction of in-hospital mortality from 6.7% to 2.5%. However, we found no significant improvements in target timings, possibly related to a transport delay between local of admission and PCI centres.8 In our national model, there were important differences between regions regarding P-PCI: it was performed in 97% of patients from “Algarve” and 93% from “Norte”, while it was only applied in 46% patients from “Centro” and 33% from “Açores”.

Concerning the “Centro” region, it is a wide geographical area with P-PCI centres in “Coimbra”, “Viseu” and “Leiria”. While a patient from “Aveiro” is rapidly transported to “Coimbra” (30–40 minutes), the same does not happen for the remaining districts. A patient from “Castelo Branco” with STEMI is usually transferred for “Coimbra” P-PCI centre whenever the procedure is feasible in <120 minutes, otherwise fibrinolysis is chosen. “Castelo Branco” has nearly 180,000 patients and its hospital is 139 km apart from “Coimbra’s” P-PCI centre (a hour and half by car) (distance and time estimated by Google Maps). Patients from “Guarda” are transferred for P-PCI when feasible. This district has almost 145,000 patients, and considering its hospital as a geographical reference, it is 179 km (2 h by car) and 79 km (1 h by car) apart from “Coimbra” and “Viseu” P-PCI centres, respectively. Thus, we hypothesized that part of this population does not have access to first-line therapy in STEMI. In the national model, only 5% of patients from “Centro” had fibrinolysis; however, in the regional model, “Castelo Branco” and “Guarda” had higher rates (53% and 30%, respectively), reflecting the complexity of performing timely P-PCI.

Of notice, “Leiria” demonstrated longer delay to P-PCI. This hospital has PCI centre since 2010, therefore the early performance might not be representative of the current results in P-PCI proportion and timings. Concerning “Açores”, it is an archipelago; the biggest island has half the population has a P-PCI centre and patients from the remaining islands usually have fibrinolysis, which explains the lower rate of P-PCI.

Regarding median time delay between admission and P-PCI, “Algarve” had the shortest (00:43) while “Centro” had the longest (01:48), still <120 minutes. Since we considered the time of admission and not the time of diagnosis (time of ECG), we assume that the delay is even shorter. However, another report from 2011 to 2015 found that only 27% of STEMI patients had a system delay <90 minutes. It was also reported that both central region of Portugal and admission at a non-PCI centre were predictors of delay.9 However, in the regional model, “Coimbra” presented the shortest delay until reperfusion (01:19), while “Guarda” (05:04) and “Castelo Branco” (06:50) exceeded the target time of 120 minutes. Thus, we corroborate the aforementioned study, and we hypothesize that this delay is explained by the districts far from P-PCI centres.

The adoption of the no reperfusion strategy was higher in “Centro” (49%), which beyond the geographical causes might be explained by a delay in symptom recognition that should activate medical contact. In the regional model, half of patients from “Aveiro” and a third from “Castelo Branco”, “Coimbra” and “Leiria” had this option. These regional disparities in P-PCI utilization were previously reported in ten European countries and could be explained by demand and supply factors, such as the number of physicians per population and age distribution, respectively.21

In the National Model, mortality was similar between those patients who underwent P-PCI or fibrinolysis (4%) and higher in those without reperfusion (10%). This finding differs from a review of randomized trials in which PCI reduced short-term mortality compared to fibrinolysis.22 However, since the majority of our patients who had fibrinolysis were distant from a PCI centre, our findings are in line with the Strategic Reperfusion Early after Myocardial Infarction (STREAM) trial, which found no differences in 30-days mortality between both treatment strategies.23

Regarding the Regional Model, mortality was higher compared to the national data (7% vs. 5%). Although we cannot claim whether this is statistically significant, we may theorize that the difference is related to the lower number of P-PCI procedures and the higher rates of patients without reperfusion strategy.

We found lower rates of P-PCI in females which might explain their higher in-hospital mortality in both models. These gender differences were previously reported,24 and they are partially explained by a higher rate of atypical presentations (non-chest pain symptoms) and a lower prevalence of traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis which affects the appropriate triage while delaying the diagnosis and treatment.25 Moreover, women commonly have smaller vessel sizes compared with men, which could influence the decision of revascularization and its success. Additionally, women demonstrate higher rates of complications after P-PCI, including haemorrhagic events.7,26,27 Socio-cultural variables such as poverty, education level, and low-level jobs might also play a role in the outcomes since lower socioeconomic status is a significant predictor of cardiovascular death in women regardless of chest pain or angiographic results.28,29 It is hypothesized that the older age and higher rate of concomitant diseases also explain this finding.30,31 Analysing by age group, there was a trend for performing less P-PCI and higher mortality rate, with increasing age, in both models, that might reflect multiple comorbidities in elderly patients.

Timely reperfusion therapy is essential for STEMI to reduce short-term mortality but also to decrease the risk of future complications such as heart failure and life-threatening arrhythmias. The first step to improve delays in the management of STEMI was the organization of P-PCI networks between hospitals and the availability of ECG recorders in the pre-hospital setting. Therefore, when the pre-hospital team manages a patient with a STEMI, it is established which is the nearest P-PCI centre where the patient must be guided. However, in some cases where de ECG is doubtful, technological advances might play an important role in the efficiency of those networks. The incorporation of telemedicine systems permits case-to-case instantaneous feedback between the pre-hospital and the Cardiologist at the P-PCI centre, allowing appropriate management of uncertain situations. For example, two studies demonstrated that the utilization of a telemedicine network based on WhatsApp® increased the rate of patients with STEMI who received timely reperfusion treatment with a consequent decrease in mortality.32,33 Additionally, the use of a free-of-charge smartphone interactive application in China allowed direct communication between patients and doctors, demonstrating a reduction in system delay and better outcomes in those patients who used the application, during the coronavirus pandemic, when there was a reduction in STEMI admissions eventually due to the fear of infection.34

To further improve referencing networks, the use of process mining techniques provides an easy and rapid way to acknowledge patients’ flow, which is useful in healthcare systems to improve efficiency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to use these tools to address STEMI. The advantages of process mining have been demonstrated in other situations particularly in stroke, a medical emergency like STEMI, describing where the delays occur in the pre-hospital setting, suggesting areas of improvement.35 This information can be used to redesign patients’ flow to reduce delays. We analysed regional time differences between time of admission and time to reperfusion, concluding that the “Centro” region of Portugal has longer delay to P-PCI possibly due the geographical reasons. Therefore, we hypothesize that it might be critical to build a new primary P-PCI centre to overcome health inequities between patients from different regions with a possible benefit concerning quality of life and mortality, since not all have access to state-of-the-art treatment. Process mining tools not only provide the time differences between prespecified events but also represent them graphically automatically, facilitating its comprehension. Because STEMI care is usually organized in referencing networks, process mining tools might be used to analyse network inefficiencies worldwide.

This study had important limitations. In the national model most regions are under/overrepresented, which limits real-world extrapolation. Regarding the regional model, we only included 31% patients from “Centro”, since the local where the patient first presented was unknown for the remaining patients. Finally, since we built the models according to the Portuguese network of referencing in cardiology from 2015, some patients may be inaccurately distributed, due to changes to this network.

In conclusion, process mining tools graphically depict clinical pathways, easily highlighting their inefficiencies and areas of improvement, with potential applications in several fields of medicine. As STEMI remains a major cause of morbimortality, it is critical to establish efficient P-PCI networks to provide timely reperfusion treatment. Therefore, a new P-PCI centre in the “Centro” region of Portugal is essential to offer timely first-line treatment to the population from “Castelo Branco” and “Guarda”, overcoming healthcare access inequalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all centres that participated in the ProACS and Adriana Belo, biostatistician of the CNCDC.

Footnotes

Contributorship: J.B.-R and M.O.-S participated in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing the original draft, revision and editing, data curation, visualization, supervision, and project administration. M.S. and P.C. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, software, writing – review and editing, and project administration. G.I.-S. and C.F.-L. contributed in conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition. M.C. and S.M. contributed in conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing – review and editing, resources, data curation and project administration. L.G. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing – review and editing, resources, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Approved by the Comissão Nacional de Protecção de Dados (n° 3140/2010).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: J.B.-R.

ORCID iD: João Borges-Rosa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6973-2598

References

- 1.Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar Pet al. et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 3232–3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Causas de Morte: 2017. Lisboa: INE. ISSN 2183-5489. ISBN 978-989-25-0481-0, https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/358633033 (2019).

- 3.Every NR, Hochman J, Becker Ret al. et al. Critical pathways: a review. Committee on Acute Cardiac Care, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation 2000; 101: 461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez-Llatas C, Valdivieso B, Traver Vet al. et al. Using process mining for automatic support of clinical pathways design. Methods Mol Biol 2015; 1246: 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Aalst W. Process mining: data science in action. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibanez-Sanchez G, Fernandez-Llatas C, Martinez-Millana A, et al. Toward value-based healthcare through interactive process mining in emergency rooms: the stroke case. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timoteo AT, Mimoso J. and em nome dos investigadores do Registo Nacional de Sindromes Coronarias A. Portuguese registry of acute coronary syndromes (ProACS): 15 years of a continuous and prospective registry. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2018;37:563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira H, Pinto FJ, Cale R, et al. The stent for life initiative: factors predicting system delay in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2018; 37: 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Llatas C, Meneu T, Benedi JMet al. et al. Activity-based process mining for clinical pathways computer aided design. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010; 2010: 6178–6181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández-Llatas C, Pileggi SF, Traver Vet al. et al. Timed parallel automaton: a mathematical tool for defining highly expressive formal workflows. In: Proceedings of the 2011 fifth Asia modelling symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 2011, pp.56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Llatas C. Interactive process mining in healthcare. 1st ed. Springer eBook Collection. Springer International Publishing and Imprint Springer, 2021. 10.1007/978-3-030-53993-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Instituto Nacional de Estatística - NUTS 2013: as novas unidades territoriais para fins estatísticos. Lisboa: INE. ISBN 978-989-25-0341-7, https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/230205992 (2015, accessed 15 September 2020).

- 14.Proposta de atualização da Rede de Referenciação de Cardiologia, elaborada pelo Programa Nacional para as Doenças Cérebro-Cardiovasculares da Direção-Geral da Saúde e aprovada pelo Exmo Sr. Ministro da Saúde, Dr Fernando Leal da Costa em, https://www.sns.gov.pt/sns/redes-de-referenciacao-hospitalar/ (2015, accessed 15 September 2020).

- 15.Killip T, III, Kimball JT. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1967;20:457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby Pet al. et al. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khera S, Kolte D, Gupta T, et al. Temporal trends and sex differences in revascularization and outcomes of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in younger adults in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66: 1961–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itzahki Ben Zadok O, Ben-Gal T, Abelow A, et al. Temporal trends in the characteristics, management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome according to their Killip class. Am J Cardiol 2019; 124: 1862–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Censos 2011 Resultados Definitivos - Portugal. Lisboa: INE. ISSN 0872-6493. ISBN 978-989-25-018. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=73212469&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (2012, accessed 15 September 2020).

- 20.Pereira H, Cale R, Pinto FJ, et al. Factors influencing patient delay before primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the stent for life initiative in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2018; 37: 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laut KG, Gale CP, Pedersen ABet al. et al. Persistent geographical disparities in the use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in 120 European regions: exploring the variation. EuroIntervention 2013; 9: 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003; 361: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, et al. Fibrinolysis or primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1379–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawesson SS, Alfredsson J, Fredrikson Met al. et al. A gender perspective on short- and long term mortality in ST-elevation myocardial infarction—a report from the SWEDEHEART register. Int J Cardiol 2013; 168: 1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lichtman JH, Leifheit EC, Safdar B, et al. Sex differences in the presentation and perception of symptoms among young patients with myocardial infarction: evidence from the VIRGO study (variation in recovery: role of gender on outcomes of young AMI patients). Circulation 2018; 137: 781–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hvelplund A, Galatius S, Madsen M, et al. Women with acute coronary syndrome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen JT, Berger AK, Duval Set al. et al. Gender disparity in cardiac procedures and medication use for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 155: 862–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connelly PJ, Azizi Z, Alipour Pet al. et al. The importance of gender to understand sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2021; 37: 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Bittner V, et al. Importance of socioeconomic status as a predictor of cardiovascular outcome and costs of care in women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Results from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008; 17: 1081–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang SH, Suh JW, Yoon CH, et al. Sex differences in management and mortality of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction National Registry). Am J Cardiol 2012; 109: 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyto V, Sipila J, Rautava P. Gender and in-hospital mortality of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from a multihospital nationwide registry study of 31,689 patients). Am J Cardiol 2015; 115: 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teixeira AB, Zancaner LF, Ribeiro FFF, et al. Reperfusion therapy optimization in acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation using WhatsApp(R)-based telemedicine. Arq Bras Cardiol 2022; 118: 556–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alhejily WA. Implementing “chest pain pathway” using smartphone messaging application “WhatsApp” as a corrective action plan to improve ischemia time in “ST-elevation myocardial infarction” in primary PCI capable center “WhatsApp-STEMI Trial”. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2021; 20: 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nan J, Jia R, Meng Set al. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the importance of telemedicine in managing acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: preliminary experience and literature review. J Med Syst 2021; 45: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mans R, Schonenberg H, Leonardi G, et al. Process mining techniques: an application to stroke care. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008; 136: 573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]