Background:

Despite advances in opioid-sparing pain management, postdischarge opioid overprescribing in plastic surgery remains an issue. Procedure-specific prescribing protocols have been implemented successfully in other surgical specialties but not broadly in plastic surgery. This study examined the efficacy of procedure-specific prescribing guidelines for reducing postdischarge opioid overprescribing.

Methods:

A total of 561 plastic surgery patients were evaluated retrospectively after a prescribing guideline, which recommended postdischarge prescription amounts based on the type of operation, was introduced in July 2020. Prescription and postdischarge opioid consumption amounts before (n = 428) and after (n = 133) guideline implementation were compared. Patient satisfaction and prescription frequency of nonopioid analgesia were also compared.

Results:

The average number of opioid pills per prescription decreased by 25% from 19.3 (27.4 OME) to 15.0 (22.7 OME; P = 0.001) after guideline implementation, with no corresponding decrease in the average number of postdischarge opioid pills consumed [10.6 (15.1 OME) to 8.2 (12.4 OME); P = 0.147]. Neither patient satisfaction with pain management (9.6‐9.6; P > 0.99) nor communication (9.6‐9.5; P > 0.99) changed. The rate of opioid-only prescription regimens decreased from 17.9% to 7.6% (P = 0.01), and more patients were prescribed at least two nonopioid analgesics (27.5% to 42.9%; P = 0.003). The rate of scheduled acetaminophen prescription, in particular, increased (54.7% to 71.4%; P = 0.002).

Conclusions:

A procedure-specific prescribing model is a straight-forward intervention to promote safer opioid-prescribing practices in plastic surgery. Its usage in clinical practice may lead to more appropriate opioid prescribing.

Takeaways

Question: Does a procedure-specific opioid-prescribing model promote safer opioid-prescribing practices?

Findings: Our retrospective review of a procedure-specific opioid-prescribing model showed a decrease in the number of opioid pills prescribed without sacrificing patient satisfaction with pain control or provider communication. Prescriptions of nonopioid analgesics also increased.

Meaning: A procedure-specific opioid-prescribing model is a simple intervention to promote safer and more appropriate opioid-prescribing practices in plastic surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Excess prescription opioids are a major public health concern, and overprescribing after surgical procedures contributes to their availability. A review of patients who underwent orthopedic, thoracic, obstetric, and general surgical procedures demonstrated that 67%–92% of patients reported leftover opioid medication, resulting in 42%–71% of prescribed opioid pills remaining unused.1,2 For patients undergoing plastic surgery procedures, 50%–70% of opioid pills prescribed were not taken, and 6%–13% of patients reported new persistent use.3–9 The influx of excess opioid pills into the community through diversion of leftover medication poses great potential for harm. Larger sizes of opioid prescriptions may influence consumption of more opioid pills beyond a patient’s pain control needs, and fuels prescription diversion and misuse.10–12 These correlate to a greater risk of opioid use disorder and overdose deaths.13–15 Despite this, there remains a paucity of published strategies to reduce and standardize postdischarge opioid prescriptions for plastic surgery patients.9,16,17

Plastic surgery procedures are characterized by a diversity of procedures, multidisciplinary collaborations, and a high proportion of ambulatory cases, which present challenges to the development of standardized protocols for opioid prescribing.18,19 Existing protocols have utilized patient or surgical characteristics or inpatient opioid consumption to derive postdischarge opioid prescription amounts.17,20–23 However, these protocols can be unwieldy, requiring the practitioner to ascertain and input many different variables to determine an opioid amount, or are ill-suited for outpatient procedures. A more straight-forward approach is to utilize procedure type to inform opioid prescription quantity. This has been implemented successfully in other surgical specialties, but, thus far, this strategy has not been evaluated broadly for plastic surgery procedures.24–27

Recently, we have determined average amounts of opioids consumed after discharge for 23 different major and minor, inpatient, and outpatient plastic surgery procedures. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of procedure-specific opioid-prescribing guidelines derived from the average amount of opioids that were consumed for each procedure. We hypothesized that these guidelines would reduce the quantity of opioids prescribed without negative impact on patient satisfaction and pain control.

METHODS

Study Design

After IRB approval (IRB: 2019H0263), a retrospective review of patients who underwent plastic and reconstructive surgery procedures at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center between March 2018 and January 2021 was completed. All patients were asked to complete a survey regarding post-discharge pain medication usage at their 1-month postoperative visit; patients were informed of this postoperative survey during their preoperative visit in an effort to reduce recall bias. Data regarding demographics, procedure type, post-discharge opioid and nonopioid analgesic prescription quantities and dose, and the prescribing service were collected via chart review. Information regarding post-discharge opioid and nonopioid medication use, refill requests, ongoing opioid use, prior opioid use, and satisfaction with medication communication and pain control were collected through the post-discharge survey. Additional details regarding the survey, including a copy of the survey, can be found in a previous study,9 and in figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows post-discharge opioid consumption surveys (http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C359). All work herein is reported in adherence to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Procedure-specific Opioid-prescribing Guidelines

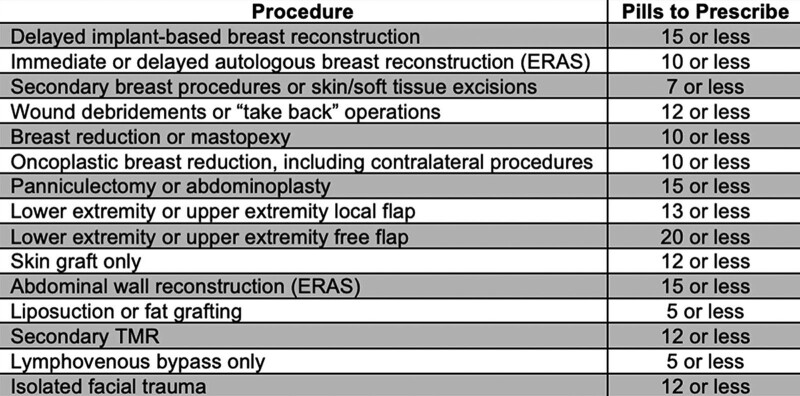

A prior retrospective review of departmental prescribing practices tracked average opioid consumption across inpatient and outpatient procedure types between March 2018 and September 2019.9 These data were used to create procedure-specific prescription guidelines, which were implemented on July 1, 2020 for the plastic and reconstructive surgery department (Fig. 1). Plastic surgery attending surgeons, residents, and physician assistants were educated and instructed to use these guidelines through a one-time email deployed department-wide, on July 1, 2020. Paper copies of the guideline were also placed in work areas so residents and physician assistants had the guidelines readily available for reference. Procedures were included in the guidelines if patients undergoing those procedures were usually placed on the plastic surgery service as the primary service, indicating that, most of the time, post-discharge opioid prescriptions were written by a plastic surgery prescriber. The upper limit for the number of pills recommended for each procedure was based on the average number of pills consumed by patients in our prior study. Surgeons were instructed to refer to the guideline and prescribe the recommended amount. Guideline adherence was not actively enforced, and they were given the discretion to modify prescriptions as necessary based on clinical scenarios. Additionally, surgeons were recommended to use a multimodal analgesia regimen, such that patients should also be prescribed scheduled acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory nonopioid analgesics unless contraindicated, with consideration given to gabapentin for patients at high risk of persistent postoperative pain.

Fig. 1.

Opioid-prescribing guidelines. A guide detailing recommended prescription amounts based on the type of operation undergone by the patient was distributed to physicians in the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at The Ohio State University.

While only plastic surgery prescribers were given the prescribing guidelines (plastic surgery group; preintervention cohort, n = 364 and postintervention cohort, n = 105), services other than plastic surgery also provided prescriptions for a proportion of patients included in this study if they were designated as the primary service. Therefore, a control group was formed using patients who underwent procedures included within the guidelines, but whose prescribers were affiliated with a nonplastic surgery service (other group; preintervention cohort, n = 64 and postintervention cohort, n = 28). This allowed for experimental control of any potential confounders of changing prescribing practices not due to the intervention.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

A total of 1756 patients were asked to complete the 1-month postoperative survey. Patients were excluded from evaluation if they did not return completed surveys, or if they did not include quantifiable information regarding their post-discharge opioid consumption in their 1-month survey. Patients were also split into a preintervention cohort and a postintervention cohort based on the date of their visit relative to the implementation date of the prescribing guideline (see below). Based on these criteria, 577 preintervention patients were included for study evaluation, and 180 postintervention patients were included for study evaluation. Patients were then excluded from final analysis if their procedure was not included in the prescription guideline intervention, for a total of 428 (74%; 149 excluded) patients in the preintervention cohort and 133 (74%; 47 excluded) patients in the postintervention cohort. (See figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows patient selection and demographics, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C360.) Patients whose surveys included quantitative opioid consumption data but excluded other data (eg, satisfaction rating and multimodal analgesia use) were excluded from those respective secondary analyses only. Patients were not excluded for using opioids preoperatively.

Data Analysis

The primary outcome was measured by the average number of opioid pills prescribed in a single prescription. All other results were evaluated as secondary outcomes. Patients whose procedure occurred before the intervention (preintervention group) were compared to patients whose procedure occurred after initiating the intervention (postintervention group). In addition, patients whose opioid prescriptions were written by a plastic surgery prescriber (plastic surgery group) were compared to patients whose prescriptions were written by other prescribers (other group).

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.03 software (GraphPad Software Inc). Data were compared using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test following verification of normality and similar variance. Due to the large amount of negative skew in the survey data (pain management and communication scores), these data were compared using Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests. A P level of 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

The average age of the preintervention group was 51 (range, 17–91; 95% CI, 49–52), while the average age of the postintervention group was 47 (range, 18–82; 95% CI, 45–50). Among the preintervention group, 76.4% identified as women. Among the postintervention group, 75.2% identified as women. The preintervention cohort had a greater percentage of inpatients (56.3%) than the postintervention cohort (45.1%). The average length of stay for the preintervention cohort was 2.5 ± 4.9 days with a median of 1 day (range, 0–38; 95% CI, 0–3), and the average length of stay for the postintervention cohort was 1.1 ± 1.8 days with a median of 0 days (range, 0–8; 95% CI, 0–2). Preoperative opioid use was reported by 13.7% of the preintervention group and 12.8% of the postintervention group. (See figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C360.)

Compared to survey respondents, nonrespondents were of similar characteristics but had a slightly higher female predominance. (See figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows nonresponder analysis, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C361.)

Opioid Prescribing and Consumption Patterns

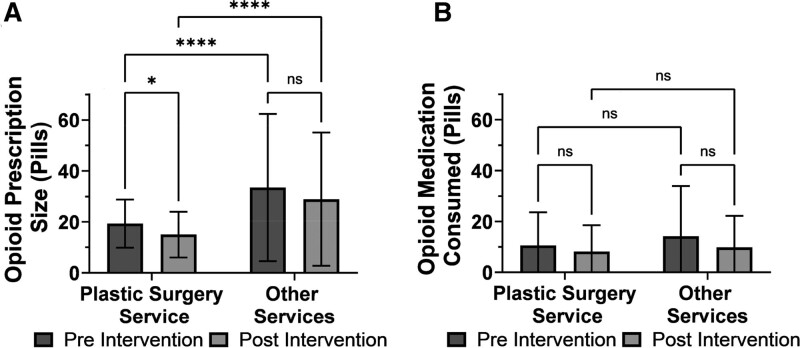

The average number of pills prescribed per patient for the plastic surgery group decreased by 25% after the intervention [19.3 ± 9.5 pills (27.4 ± 13.5 oral morphine equivalents [OMEs]) to 15.0 ± 9.0 pills (22.7 ± 13.6 OMEs), P = 0.001], while the average number of pills prescribed for the other group remained the same [33.5 ± 28.9 pills (50.6 ± 43.6 OMEs) to 28.9 ± 26.1 pills (38.4 ± 34.7 OMEs), P = 0.472]. In addition, the plastic surgery service prescribed fewer opioid pills than other surgical services both before [19.3 ± 9.5 pills (27.4 ± 13.5 OMEs) versus 33.5 ± 28.9 pills (50.6 ± 43.6 OMEs), P < 0.001] and after [15.0 ± 9.0 pills (22.7 ± 13.6 OMEs) versus 28.9 ± 26.1 pills (38.4 ± 34.7 OMEs), P = 0.01] the intervention. After the intervention, significantly more patients were prescribed an amount that was recommended by the opioid prescribing guideline (34% versus 19%, P = 0.0007).

The average number of opioid pills consumed by patients during the 1-month post-discharge period did not change for either the plastic surgery group [10.6 ± 13.0 pills (15.1 ± 18.5 OMEs) to 8.2 ± 10.3 pills (12.4 ± 15.6 OMEs), P = 0.147] or the other group [14.2 ± 19.7 pills (21.4 ± 29.7 OMEs) to 9.8 ± 12.4 pills (13.0 ± 16.5 OMEs), P = 0.279] after intervention. In addition, the identity of the prescribing service had no effect on consumption amount either before (P = 0.062) or after (P = 0.268) intervention. The average number of unused pills also did not change in the other group or in the plastic surgery group after intervention (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Opioid prescription and consumption. Comparison of opioid prescription (A) and post-discharge consumption amounts (B). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. *, <0.05; **, <0.01; ***, <0.001; ****, <0.0001; ns, not significant.

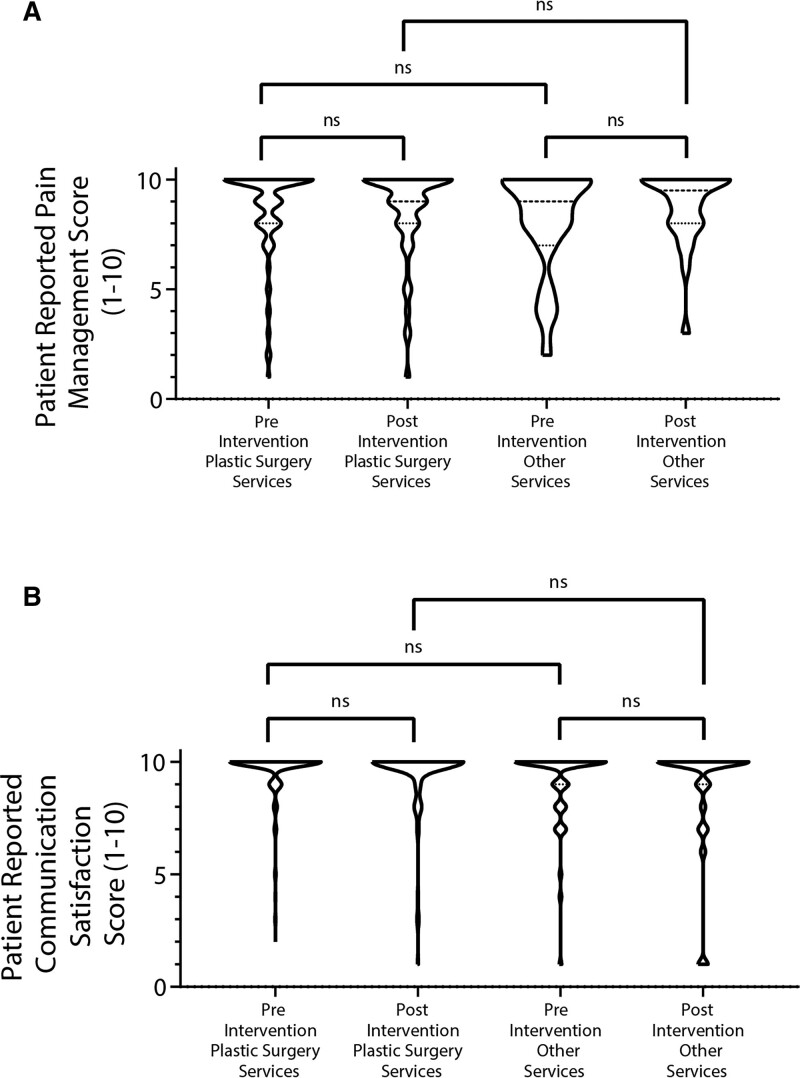

Patient Satisfaction

For the plastic surgery group, average patient satisfaction with pain control was unchanged after intervention (8.6 ± 2.1 to 8.6 ± 2.1; P > 0.99). Similarly, average patient satisfaction with pain control for the other group did not change significantly after intervention (8.1 ± 2.3 to 8.8 ± 1.7; P > 0.99). In terms of patient satisfaction with communication, neither the plastic surgery group (9.6 ± 1.2 to 9.5 ± 1.5; P > 0.99) nor the other group (9.1 ± 1.7 to 8.8 ± 2.5; P > 0.99) had a significant change after intervention (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction ratings regarding pain control (A) and communication (B) remained similar across all groups. Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests. ns, not significant.

Refill Rate

For the plastic surgery group, there was a total of 50 refills among 364 patients preintervention and 21 refills among 105 patients postintervention (14% to 20%; P = 0.33). For the other group, there were 10 refills reported by 64 patients preintervention and eight refills reported by 28 patients postintervention (16% to 29%; P = 0.15). No difference was found in the refill rate between the plastic surgery group and the other group before (P = 0.327) or after (P = 0.327) intervention. (See figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which shows refills and additional drugs, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C362.)

Multimodal Analgesia Prescribing

Postintervention, fewer patients in the plastic surgery group were prescribed only opioids for pain control compared to preintervention (17.9%–7.6%; P = 0.01), and more patients were prescribed two nonopioid analgesics (27.5%–42.9%; P = 0.003) in addition to opioids. Furthermore, a greater proportion of plastic surgery group patients received a scheduled acetaminophen prescription postintervention (54.7%–71.4%; P = 0.002). In contrast, patients in the other group saw no significant change in the rate of multimodal analgesia use or in the usage rate of any individual nonopioid pain medication. (See figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C362.)

DISCUSSION

Current prescribing practices after surgery are important contributors to opioid waste, diversion, and help fuel the opioid epidemic.7,28,29 We previously demonstrated that plastic surgery patients are significantly overprescribed opioids, with 52% of opioid pills prescribed at discharge for plastic surgery procedures going unused, resulting in over 30,000 unused pills per year at one institution.9 Guidelines and protocols aimed at standardizing and reducing opioid prescribing for plastic surgery procedures are, therefore, critical. In this study, we implemented a straightforward, procedure-specific opioid-prescribing guideline based on average opioid consumption per procedure type and found that it was effective at reducing the average prescription size by 4.3 pills (4.7 OMEs) or 25% of the average opioid prescription. The plastic surgery service was the primary service for 1579 patients in the 2020 fiscal year, indicating that adherence to these prescribing guidelines potentially reduces opioid waste in 1 year from one surgical department by 6789 (7421 OMEs) pills. Crucially, our prescribing guideline was likely able to reduce opioid prescription size without sacrificing the quality of patient satisfaction or pain control.

We compared patients with plastic surgery prescribers to patients with prescribers from other services and found that prescription sizes in the other group remained unchanged after the intervention date, confirming that the reduction in opioid prescribing was a result of our intervention. Of note, patients in both the plastic surgery group and the other group underwent the same procedures; the difference being whether the prescribing prescriber had been given the guidelines (plastic surgery group) or not (other group). Additionally, even before intervention, plastic surgery prescribers prescribed significantly fewer opioids for the same procedures than other surgical services, although patient opioid consumption did not differ between groups. The consistency in opioid consumption regardless of guideline implementation and prescribing service indicates that excess opioid prescribing can be reduced without impacting the number of pills patients need to consume to achieve adequate pain control, a takeaway that is further supported by the consistency of patient satisfaction before and after guideline implementation. These findings suggest a lack of strong interdisciplinary communication and education regarding pain management, resulting in disparate outcomes even though care of patients was shared between services.30 Standardization of opioid and multimodal analgesia prescribing guidelines, therefore, needs to involve input and coordination from all disciplines in order to have the greatest impact.

The present prescribing guidelines are not the first to explore the concept of standardizing opioid prescribing. Indeed, multiple studies and initiatives have examined the impact of different strategies for reducing opioid prescribing or consumption. For example, the Plastic Surgery Initiative to provide Controlled Analgesia and Safe Surgical Outcomes suggests an analgesic regimen based on qualitative factors, such as tissue type, multisite surgery, complex dissection, and opioid naivete.17 Although this protocol successfully reduced both prescription amount and size, it may require a significant time and resource investment for prescribers to replicate and implement a similar formula. The strength of our intervention is that it is simple, yet specific, involving only one variable—procedure type.

In addition, the guidelines presented also recommended the incorporation of multimodal analgesia into post-discharge pain medication regimens, and this successfully resulted in increased nonopioid analgesic prescribing and utilization. These findings illustrate that minimal, simple interventions can have a significant impact on prescribing practices.

The authors acknowledge several limitations. This study was performed with the patient population of a single academic center’s plastic surgery department, which may limit the study cohort’s diversity and sample size. While a larger sample size may have identified additional conclusions, we were, nonetheless, able to identify meaningful differences from the population studied. Our control group of nonplastic surgery prescribers is imperfect because it does not take into account potential differences among departmental prescribing patterns, which could confound this study. While an intradepartmental control group would have addressed this shortcoming, that, too, is imperfect due to potential differences in prescribing among individuals. We also did not exclude patients who were taking opioids preoperatively or who received perioperative nerve blocks and pain pumps, which could have impacted their postoperative prescription opioid consumption. We attempted to reduce recall bias by informing patients preoperatively that they would be asked about postoperative opioid use, but note that this may have, conversely, influenced patient behavior in terms of opioid consumption and reporting. Notably, the patient-reported outcome measure domains of our survey (ie, satisfaction with pain control and provider communication) were not tested by a standardized validation protocol or pilot study, thus limiting the meaningfulness of the conclusion drawn from those results. Although plastic surgery prescribers were encouraged to follow the guideline via a one-time communication which resulted in a 34% adherence rate, a significant reduction in overprescribing was still observed, demonstrating the potential promising impact with an even higher adoption rate. Additionally, the median length of stay is significantly different for the preintervention and postintervention cohorts, which may have influenced the number of opioids that patients consume post-discharge. This was likely a result of the university ordinance limiting elective operations that would require an inpatient stay during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the limited sample size, we were unable to perform a meaningful subgroup analysis based on procedure type or length of stay. This could have addressed this shortcoming by providing a more specific view of how guideline implementation affected opioid prescription and consumption patterns of patients within each individual procedure. However, we observed no statistical differences in post-discharge opioid consumption between the two groups. Furthermore, the opioid prescription refill rates before and after the intervention showed no statistical significance despite an increase for patients of both plastic surgery and other surgical services. It is possible that this negative result may be due to a lack of statistical power, and we, therefore, recommend that the refill rate data be interpreted cautiously. Although our guideline was created using data collected from a retrospective chart review, it does not include a comprehensive list of procedures performed by our plastic and reconstructive surgery department. We included only those procedures with enough preexisting data to inform evidence-based guideline creation. Furthermore, the presented work inherently siloes patients into a prescription amount based on the singular characteristic that is considered: procedure type. It can be expected that a model that inputs more of a patient’s unique characteristics might be more sensitive to each patient’s individual pain control needs. However, because of its simplicity, this type of single-input strategy can be readily adapted to other plastic surgery services and other surgical specialties for immediate impact.

CONCLUSIONS

A surgeon-led movement to improve opioid stewardship represents a crucial strategy in addressing the ongoing opioid crisis. The prescribing guidelines introduced in this study are one method of promoting opioid stewardship by providing easy-to-follow recommendations that restrict the outflow of excess opioid pills into the community. Potential benefits of this model include decreased overprescribing, opioid waste, and risk of opioid diversion without sacrificing performance in patient pain management and satisfaction. The simplicity in the formulation of this protocol could also allow other surgical departments to use it as a template for rapid intervention in their prescribing practices while further research is performed on a more comprehensive prescribing protocol. Given the correlation between opioid overprescription, diversion, and overdose deaths, such swift action may lessen the health burden on our patients and community.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Ohio Valley Society of Plastic Surgeons Annual Conference, Louisville, Kent., June 3, 2022.

Disclosure: J. E. Janis receives royalties from Thieme and Springer Publishing. K. Blum was supported by the Tau Beta Pi 35th Centennial Fellowship. J. C. Barker was supported by NIH F32HL144120, NIH T32AI106704, and the Ohio State University President’s Postdoctoral Scholar Program. The other authors have no financial interest to declare.

Related Digital Media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSGlobalOpen.com.

Mr. Zhang and Dr. Blum are co-first authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartels K, Mayes LM, Dingmann C, et al. Opioid use and storage patterns by patients after hospital discharge following surgery. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, et al. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson SP, Chung KC, Zhong L, et al. Risk of prolonged opioid use among opioid-naive patients following common hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:947–957.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olds C, Spataro E, Li K, et al. Assessment of persistent and prolonged postoperative opioid use among patients undergoing plastic and reconstructive surgery. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21:286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcusa DP, Mann RA, Cron DC, et al. Prescription opioid use among opioid-naive women undergoing immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett KG, Kelley BP, Vick AD, et al. Persistent opioid use and high-risk prescribing in body contouring patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose KR, Christie BM, Block LM, et al. Opioid prescribing and consumption patterns following outpatient plastic surgery procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, et al. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu JJ, Janis JE, Skoracki R, et al. Opioid overprescribing and procedure-specific opioid consumption patterns for plastic and reconstructive surgery patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:669e–679e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of opioid prescribing with opioid consumption after surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e184234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, et al. The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:557–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modarai F, Mack K, Hicks P, et al. Relationship of opioid prescription sales and overdoses, North Carolina. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamieson MD, Everhart JS, Lin JS, et al. Reduction of opioid use after upper-extremity surgery through a predictive pain calculator and comprehensive pain plan. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44:1050–1059.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson SP, Wormer BA, Silvestrini R, et al. Reducing opioid prescribing after ambulatory plastic surgery with an opioid-restrictive pain protocol. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;84:S431–S436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang AMQ, Retrouvey H, Wanzel KR. Addressing the opioid epidemic: a review of the role of plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:1295–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph WJ, Cuccolo NG, Chow I, et al. Opioid-prescribing practices in plastic surgery: a juxtaposition of attendings and trainees. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiels CA, Ubl DS, Yost KJ, et al. Results of a prospective, multicenter initiative aimed at developing opioid-prescribing guidelines after surgery. Ann Surg. 2018;268:457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boitano TKL, Sanders LJ, Gentry ZL, et al. Decreasing opioid use in postoperative gynecologic oncology patients through a restrictive opioid prescribing algorithm. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159:773–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barker JC, Joshi GP, Janis JE. Basics and best practices of multimodal pain management for the plastic surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoenbrunner AR, Janis JE. Pain management in plastic surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2020;47:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS, Howard RA, Klueh MP, et al. The impact of education and prescribing guidelines on opioid prescribing for breast and melanoma procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wyles CC, Hevesi M, Ubl DS, et al. Implementation of procedure-specific opioid guidelines: a readily employable strategy to improve consistency and decrease excessive prescribing following orthopaedic surgery. JB JS Open Access. 2020;5:e0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stepan JG, Lovecchio FC, Premkumar A, et al. Development of an institutional opioid prescriber education program and opioid-prescribing guidelines: impact on prescribing practices. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, et al. ; Opioids After Surgery Workgroup. Opioid-prescribing guidelines for common surgical procedures: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2019. HHS Publication No PEP19-5068. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed June 9, 2021.

- 29.Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;329:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiu AS, Healy JM, DeWane MP, et al. Trainees as agents of change in the opioid epidemic: optimizing the opioid prescription practices of surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]