Abstract

Background

The child nutritional status of a country is a potential indicator of socioeconomic development. Child malnutrition is still the leading cause of severe health and welfare problems across Bangladesh. The most prevalent form of child malnutrition, stunting, is a serious public health issue in many low and middle-income countries. This study aimed to investigate the heterogeneous effect of some child, maternal, household, and health-related predictors, along with the quantiles of the conditional distribution of Z-score for height-for-age (HAZ) of under five children in Bangladesh.

Methods and materials

In this study, a sample of 8,321 children under five years of age was studied from BDHS-2017-18. The chi-square test was mainly used to identify the significant predictors of the HAZ score and sequential quantile regression was used to estimate the heterogeneous effect of the significant predictors at different quantiles of the conditional HAZ distribution.

Results

The findings revealed that female children were significantly shorter than their male counterparts except at the 75th quantile. It was also discovered that children aged 7–47 months were disadvantaged, but children aged 48–59 months were advantaged in terms of height over children aged 6 months or younger. Moreover, children with a higher birth order had significantly lower HAZ scores than 1st birth order children. In addition, home delivery, the duration of breastfeeding, and the BCG vaccine and vitamin A received status were found to have varied significant negative associations with the HAZ score. As well, seven or fewer antenatal care visits was negatively associated with the HAZ score, but more than seven antenatal care visits was positively associated with the HAZ score. Additionally, children who lived in urban areas and whose mothers were over 18 years and either normal weight or overweight had a significant height advantage. Furthermore, parental secondary or higher education had a significant positive but varied effect across the conditional HAZ distribution, except for the mother’s education, at the 50th quantile. Children from wealthier families were also around 0.30 standard deviations (SD) taller than those from the poorest families. Religion also had a significant relationship with the conditional HAZ distribution in favor of non-Muslim children.

Conclusions

To enhance children’s nutritional levels, intervention measures should be designed considering the estimated heterogeneous effect of the risk factors. This would accelerate the progress towards achieving the targets of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to child and maternal health in Bangladesh by 2030.

Introduction

The child nutritional status of a country is a potential indicator of socioeconomic development. Although Bangladesh has tried hard to reduce child malnutrition, it remains the country’s leading cause of severe child health and welfare problems. Stunting (i.e., a low linear growth) is the most prevalent form of child malnutrition, repeated infection, and inadequate psychosocial stimulation [1,2], and it is considered a serious public health problem among children in many countries [3]. Therefore, stunting during childhood is the most reliable indication of children’s well-being and an accurate marker of societal inequality [1]. Globally, about 150.8 million children aged under five years were stunted in 2017 [4], and nearly 40 percent of stunted children lived in Southern Asia [5]. Bangladesh ranked among the highest rates of child malnutrition in the world, with more than 54% of preschool-aged children suffering from stunting [6]. The rate of stunting among children under five decreased dramatically worldwide, from 47% in 1985 to 21.9% in 2018 [7,8]. In Bangladesh, however, 31% of children under the age of five were stunted in 2017 [7] and 28% in 2019 [9]. The stunted rate among children under the age of five in Bangladesh is still greater than the global rate, notwithstanding a sharp decline in chronic malnutrition as measured by levels of stunting.

Stunting has both short and long-term negative impacts on children’s health directly and indirectly, such as a low birth weight, obstructing cognitive development, which affects school achievement, and restricting their life prospects in adulthood [10]. Stunting can also affect a child’s social and personal development [11]. The serious consequences of stunting have led to the establishment of worldwide nutrition targets to lessen the prevalence of stunted children under five years of age by 40% before 2025 [12]. This worldwide target has subsequently been supported by the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG-2), target 2, with a commitment to end all kinds of malnutrition by the year 2030. Hance, taking any effective different approach to the prevention of stunting could avoid at least 1.7 million childhood deaths [13]. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it more challenging to meet the global nutritional targets for stunting by 2025, especially in low and middle-income countries [14,15]. To reduce the prevalence of stunted children, an effective intervention package must be devised, focusing on the most vulnerable groups.

Many studies have been conducted to identify significant risk factors for stunting in low and middle-income countries, and some have focused on Bangladesh [4,7,10,16–50]. Moreover, several studies have been conducted on child malnourishment in Bangladesh [6,51–54]. However, most of these studies have applied binary or linear regression models to explore the unconditional estimate against the potential factors of child malnutrition. However, if the relationship between child nutritional status and the various demographic and socioeconomic factors is heterogeneous at the various quantiles of the nutritional distribution, then the adoption of these methods may lead to inappropriate policy intervention measures [55]. In addition, outliers may lead to an overestimation of the effect of the chosen covariates or a loss of information pertinent to intervention and health promotion strategies. Outliers also influenced the estimates of mean and variance of a dataset [56,57], In the presence of outliers, the quantile regression (QR) model provides robust conditional estimates without considering the behavior of the mean and median [58]. It produces estimates that are relatively more unbiased than the estimates generated by the linear regression model when the data violate the assumption of normality [59]. Borooah (2005) applied the QR model to capture the heterogeneity and the determinants of height-for-age in India [60]. Many more studies have also used the QR model for similar purposes [55,61–65]. Therefore, it was crucial to estimate the robust measure of the heterogeneous effect of the significant risk factors of child stunting for designing an effective intervention package to lessen the prevalence of stunting among children in the context of Bangladesh.

In this study, the Z-score of height-for-age (HAZ) was used to measure child growth or stunting but the coefficient of skewness of the target variable showed that the HAZ score does not hold the normality assumption. Therefore, this paper investigates the robust measure of the heterogeneous effect of child, maternal, household, and health-related factors on the stunting status of children aged less than five years in Bangladesh, using the QR model and considering the secondary data collected from the latest Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS-2017-18). The findings of this study will help develop effective intervention strategies to prevent stunting in children and hasten Bangladesh’s progress toward achieving the SDGs related to child health status by 2030.

Methods and materials

Data and variables

In this study, the secondary data was obtained from a nationally representative survey called the BDHS-2017-18, which is a complete survey that covers the enumeration areas (EAs) of the whole country. Details of the sampling procedure used to conduct the survey are available in the published reports [66]. There was a sample size of 8,334 children under five years of age; however, after cleaning the missing values, the analysis was based on the data from 8,321 children.

The child’s nutritional status in the surveyed population is based on the Child Growth Standards recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). These were constructed using an international sample of culturally, ethnically, and genetically distinct healthy children residing under optimum environments favorable to achieving a child’s full genetic growth potential [66]. Among the three main anthropometric indexes for child growth, height-for-age measures linear growth. A child was considered as likely to be stunted if they had a height more than two standard deviations below the reference median of height for that age. Stunting was considered severe if the child’s height was more than three standard deviations below the reference median of height for that age [66]. The Z-score for height-for-age (HAZ) was the target variable, and several child’s characteristics such as sex, age, duration of breastfeeding, and birth order; maternal attributes such as age, education, and BMI; father’s education as well as attributes related to household, community, and health were considered as the explanatory variables in this study. The availability in the BDHS dataset, self-efficacy, and pertinent literature served as the basis for the variable selection.

Quantile regression

The quantile regression (QR) model was initially introduced by Koenker and Basset in 1978, and nowadays it is extensively applied in various research areas, particularly statistics, econometrics, and public health [55,60–65,67–69]. Suppose Y is a random (response) variable having cumulative distribution function (CDF) FY(y), i.e., FY(y) = P(Y≤y) and X is the p-dimensional vector of predictor variables. Then the τth conditional quantile of Y is described as

where the quantile level τ varies from 0 to 1.

The QR model portrayed by the conditional τth quantiles of the response Y for considering the values of predictors x1,x2,…,xp can be expressed as , where is the unknown vector of parameters.

For a random sample {y1,y2,…,yn} of Y, it is understood that the sample median minimizes the following sum of absolute deviations, . Likewise, the general τth sample quantile ξ(τ), which is the analog of Q(τ), is formulated as the minimizer: , where denotes the loss function with an indicator function I(.). The loss function ρτ allocates a weight of τ and 1−τ for positive residuals = yi−ξ and negative residuals, respectively. The linear conditional quantile function along with this loss function expands the τth sample quantile ξ(τ) to the regression setting in a similar way that the linear conditional mean function expands the sample mean. The OLS estimates is obtained based on the linear conditional mean function E(Y|X = x) = x′β, by solving [70].

The estimated parameter minimizes the sum of squared residuals as the sample mean minimizes the sum of squares . Quantile regression also estimates the linear conditional quantile function, (τ|X =x) = x′β(τ), by solving . For any quantile, τ∈(0,1) the quantity is known as the τth regression quantile. For example, τ = 0.5, which minimizes the sum of absolute residuals, also corresponds to L1-type or median regression. The set of regression quantiles {β(τ):τ∈(0,1)} is called the quantile process [70].

The QR model aimed at solving the term , where is the ith value of unknown errors, gives the asymmetric penalties τ|ei for over prediction and gives the asymmetric penalties (1−τ)|ei| for under prediction [70]. The τth quantile regression estimator is obtained by minimizing the following objective function over βτ

where, for over prediction, for under prediction [70].

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the survey was approved by the local Ethics Committee of Bangladesh and the Ethics Committee of the ICF Macro at Calverton, New York, USA.

Results

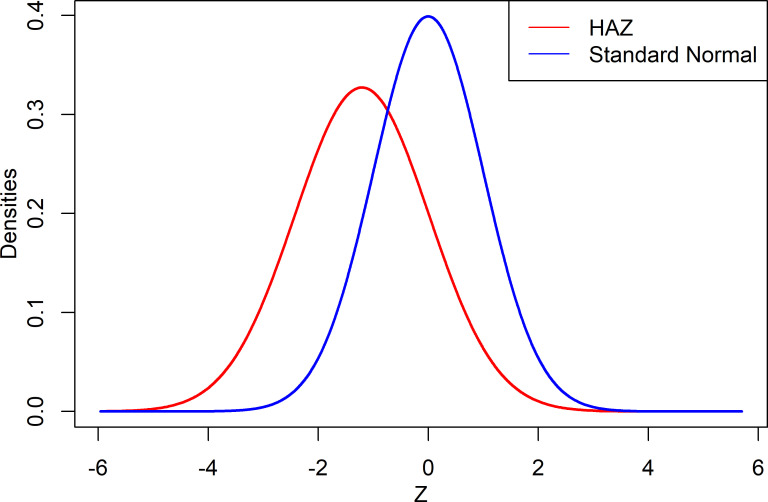

The average of the HAZ score was found to be -1.21 with a standard deviation of 1.22, while the coefficient of skewness and kurtosis were 0.25 and 1.05, respectively. The average HAZ score of less than zero indicates the distribution of the target population’s HAZ index had shifted downward, indicating that most of the children were suffering from stunting malnutrition in comparison to the reference population. Moreover, the HAZ score distribution for Bangladeshi under five children was shown to be positively skewed by the coefficient of skewness. The graphical comparison of the HAZ scores against the standard normal variate is shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Density plot of the height–for–age (HAZ) Z–scores and the standard normal variate.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of stunted children among Bangladeshi children aged under five years, along with different characteristics considered in this study. The findings show that the child’s stunting prevalence was significantly influenced by their sex, age, birth order, duration of breastfeeding, religion, place of residence and delivery, BCG vaccine and vitamin A uptake, mother’s age and BMI, number of ANC visits by mothers during pregnancy, parental education, and household’s economic status. It was observed that about 18% of the children were stunted (i.e., HAZ score < -2 SD) and approximately 6% of the children were severely stunted (i.e., HAZ score < -3 SD) in Bangladesh. Around 52% of the children were male but the prevalence rate of stunting for males was relatively less than for female children. Moreover, more than 13% of children were aged less than or equal to 6 months, and the rate of stunting typically increased with the child’s age up to two years, after which it decreased slightly. As well, the rate of stunting increased as the child’s birth order moved up. Additionally, it was discovered that Muslim children had a slightly higher stunting rate than non-Muslim children (Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of child categorized according to the anthropometric index height–for–age (stunting) by selected characteristics, Bangladesh (BDHS 2017–18, n = 8,321).

| Background Characteristics | Percent (n) | Height-for-Age (Stunting) in % (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Stunted (Z<-3 SD) | Moderately Stunted (Z<-2 SD) | P-value of Chi-square | |||

| Child Characteristics | |||||

| Sex | Male | 52.16 (4340) | 5.27 (217) | 17.94 (740) | 0.086 |

| Female | 47.84 (3981) | 6.67 (251) | 18.25 (686) | ||

| Child’s age (in months) | < = 6 | 13.14 (1093) | 0.87 (9) | 7.93 (83) | <0.001 |

| 7–12 | 8.2 (683) | 2.67 (18) | 13.24 (88) | ||

| 13–23 | 20.19 (1680) | 8.08 (132) | 23.38 (382) | ||

| 24–35 | 19.87 (1653) | 6.78 (104) | 18.79 (289) | ||

| 36–47 | 19.16 (1594) | 6.6 (98) | 19.75 (292) | ||

| 48–59 | 19.44 (1618) | 7.03 (107) | 19.18 (291) | ||

| Birth order | 1st | 38.31 (3188) | 4.92 (148) | 17.68 (532) |

<0.001 |

| 2nd-3rd | 49.22 (4096) | 5.7 (222) | 17.09 (666) | ||

| 4th or higher | 12.46 (1037) | 10 (98) | 23.3 (228) | ||

| Duration of breastfeeding | Never breastfeed | 41.28 (3435) | 7.25 (233) | 19.41 (622) |

<0.001 |

| <12 months | 2.05 (171) | 4.62 (8) | 18.84 (31) | ||

| 12 or more | 6.97 (580) | 4.84 (25) | 19.26 (101) | ||

| Still breastfeeding | 49.7 (4135) | 5.07 (202) | 16.84 (671) | ||

| Religion | Muslim | 91.96 (7652) | 5.97 (432) | 18.11 (1309) | 0.091 |

| Non-Muslim | 8.04 (669) | 5.56 (36) | 17.86 (116) | ||

| Parental Characteristics | |||||

| Mother’s age (Years) | Up to 18 | 7.23 (601) | 4.55 (26) | 18.42 (107) | <0.001 |

| 19–24 | 40.24 (3348) | 5.19 (165) | 18.7 (594) | ||

| 25–34 | 44.68 (3718) | 6.68 (235) | 17.43 (615) | ||

| 35 or more | 7.86 (654) | 6.84 (41) | 18.4 (110) | ||

| Mother’s BMI | Underweight (<18.5) | 13.6 (1132) | 8.66 (96) | 24.81 (274) | <0.001 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 59.21 (4927) | 5.97 (283) | 18.65 (885) | ||

| Overweight (> = 25) | 27.18 (2262) | 4.37 (89) | 13.11 (266) | ||

| Mother’s education level | No education | 7.15 (595) | 12.48 (71) | 23.83 (135) |

<0.001 |

| Primary | 28.4 (2363) | 7.92 (179) | 23.06 (521) | ||

| Secondary or above | 64.45 (5363) | 4.32 (218) | 15.22 (769) | ||

| Father’s education level | No education | 14.85 (1218) | 10.88 (126) | 24.77 (286) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 34.29 (2811) | 7.25 (194) | 21.16 (568) | ||

| Secondary or above | 50.86 (4170) | 3.62 (142) | 13.85 (544) | ||

| Household and Health Characteristics | |||||

| Place of residence | Rural | 73.04 (6078) | 6.23 (361) | 19.56 (1134) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 26.96 (2243) | 5.12 (107) | 13.99 (292) | ||

| Place of delivery | With Health Facility | 49.91 (2551) | 3.74 (91) | 14.31 (347) | <0.001 |

| Respondent’s Home | 50.09 (2561) | 7.01 (173) | 20.12 (495) | ||

| Number of antenatal visits during pregnancy | No antenatal visits | 13.13 (644) | 6.61 (40) | 17.14 (105) | 0.001 |

| 1–3 | 44.66 (2190) | 5.41 (113) | 18.83 (394) | ||

| 4–7 | 36.18 (1774) | 4.33 (74) | 15.71 (268) | ||

| 8 or more | 6.03 (296) | 2.73 (8) | 13.07 (36) | ||

| Had diarrhea recently | No | 95.26 (7927) | 5.88 (441) | 18.16 (1362) | 0.107 |

| Yes | 4.74 (394) | 6.99 (26) | 16.63 (63) | ||

| Had fever in last two weeks | No | 66.79 (5558) | 5.62 (294) | 18.16 (949) | 0.325 |

| Yes | 33.21 (2763) | 6.55 (174) | 17.95 (477) | ||

| Had cough in last two weeks | No | 64.01 (5326) | 5.9 (295) | 18.29 (916) | 0.274 |

| Yes | 35.99 (2995) | 5.99 (172) | 17.73 (510) | ||

| Received BCG | No | 6.92 (354) | 1.49 (5) | 8.01 (26) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 93.08 (4758) | 5.67 (259) | 17.9 (817) | ||

| Received vitamin A | No | 30.04 (1536) | 2.84 (42) | 13.23 (194) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 69.96 (3576) | 6.48 (222) | 18.96 (648) | ||

| Wealth index | Poorest | 21.44 (1784) | 8.49 (146) | 24.33 (418) | <0.001 |

| Poorer | 20.33 (1692) | 7.62 (123) | 21.83 (352) | ||

| Middle | 18.86 (1569) | 4.69 (71) | 18.72 (283) | ||

| Richer | 19.88 (1654) | 5.85 (92) | 15.11 (239) | ||

| Richest | 19.48 (1621) | 2.45 (36) | 9.18 (134) | ||

| Total (Overall) | 5.93 (468) | 18.09 (1425) | |||

Furthermore, a lower occurrence of childhood stunting was observed among the children whose parents were more educated and/or mothers were either normal or overweight. In addition, stunting prevalence decreased as the number of antenatal visits and/or household’s wealth index increased. On the other hand, a higher incidence of stunting was discovered among the children who were born at home and/or lived in rural areas. Additionally, the findings showed that a child’s nutritional status was related to their current state of health because stunting was more likely in children with fever or diarrhea than in children without such conditions, even though the association was not significant. Interestingly, children who had received vitamin A and/or the BCG vaccine had a higher rate of stunting (Table 1).

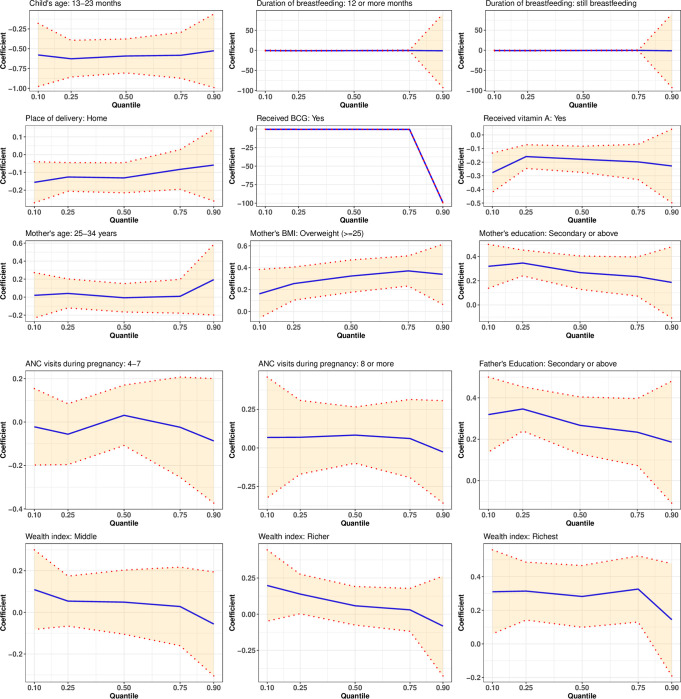

This study considered the 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 0.90 quantiles. The results of the quantile regression estimation are presented in Table 2, and Fig 2 illustrates the elasticity measured by the 95% confidence interval of the estimated coefficients, which were significant at all quantiles considered. The 95% confidence intervals of all other estimates are presented in S1 Fig. Sequential quantile regression confirmed each of the predictors identified to be significant in bivariate analysis; however, the influence of the significant predictors varied significantly across the conditional distribution of HAZ score. It was revealed that the sex of a child had a significant effect on the HAZ score, except at the 50th quantile. The female children were comparatively shorter than male children except at the 75th quantile, where an inverse scenario was observed. Furthermore, it was shown that children aged 7 to 47 months had a height disadvantage over those aged 6 months or younger, except for those aged 36 to 47 months at the 90th quantile. Those aged 48 to 59 had a height advantage except at the 90th quantile; this may indicate a non-linear relationship between the child’s age and HAZ score. Nevertheless, the association’s strength and significance were varied throughout the conditional HAZ distribution. Even though the children’s 2nd and 3rd birth order showed a significant positive association with the HAZ score at the 10th, 25th, and 75th quantiles, the strength of the association was weak. However, a statistically inverse relationship between the HAZ score and the child’s birth order was found for the 2nd and 3rd births at the 90th quantile as well as for the 4th or higher birth order at the 25th and 90th quantiles (Table 2).

Table 2. Quantile regression modeling results of selected risk predictors for stunting (HAZ score) for under five children in Bangladesh, 2017–18.

| Background Characteristics | Q10 | Q25 | Q50 | Q75 | Q90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of child (ref = Male) | |||||

| Female | -0.041** | -0.059* | -0.02 | 0.021** | -0.06** |

| Child’s age (months) (ref< = 6) | |||||

| 7–12 | -0.05 | -0.167* | -0.124* | -0.202 | -0.034 |

| 13–23 | -0.579*** | -0.627*** | -0.592*** | -0.583*** | -0.526** |

| 24–35 | -0.423** | -0.419*** | -0.312*** | -0.24* | -0.184 |

| 36–47 | -0.188** | -0.263** | -0.166** | -0.067 | 0.062 |

| 48–59 | 0.188 | 0.263* | 0.166 | 0.067 | -0.062 |

| Birth order (ref = 1st order) | |||||

| 2nd-3rd | 0.008** | 0.011** | 0.05 | 0.032** | -0.046*** |

| 4th or higher | 0.005 | -0.09* | -0.028 | 0.069 | -0.168** |

| Duration of breastfeeding (ref = Never) | |||||

| <12 months | -0.728** | -0.873 | -0.576* | -0.118* | -0.481 |

| 12 or more | -0.633** | -0.932* | -0.7** | -0.423*** | -1.069* |

| Still breastfeeding | -0.699** | -0.792* | -0.539* | -0.292** | -1.253* |

| Religion (ref = Muslim) | |||||

| Non-Muslim | 0.131* | -0.004 | -0.039 | 0.061** | 0.3** |

| Mother’s age (ref = Up to 18 years) | |||||

| 19–24 | 0.004 | 0.007** | -0.032*** | -0.005** | 0.189* |

| 25–34 | 0.02** | 0.041* | -0.007* | 0.009** | 0.194** |

| 35 or more | 0.106*** | 0.056 | -0.043*** | 0.038** | 0.454* |

| Mother’s education level (ref = No education) | |||||

| Primary | 0.155 | 0.052 | -0.057 | -0.079 | -0.063** |

| Secondary or above | 0.294* | 0.171** | -0.016** | 0.047*** | 0.012* |

| Mother’s BMI (ref = Underweight (<18.5)) | |||||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 0.158** | 0.181** | 0.185** | 0.276*** | 0.202 |

| Overweight (> = 25) | 0.162** | 0.255*** | 0.324*** | 0.371*** | 0.34** |

| Father’s education level (ref = No education) | |||||

| Primary | 0.129 | 0.110* | 0.066 | 0.161** | 0.113 |

| Secondary or above | 0.319*** | 0.346*** | 0.267*** | 0.234** | 0.186* |

| Place of residence (ref = Rural) | |||||

| Urban | -0.045 | 0.014* | 0.093** | 0.039* | 0.103 |

| Place of delivery (ref = With health facility) | |||||

| Respondent’s home | -0.156** | -0.126** | -0.131** | -0.083** | -0.059*** |

| Number of antenatal care visits (ref = None) | |||||

| 1–3 | -0.025 | -0.06 | -0.019* | -0.063 | -0.194** |

| 4–7 | -0.022** | -0.056** | 0.031** | -0.024** | -0.087*** |

| 8 or more | 0.068* | 0.069*** | 0.083** | 0.061*** | -0.026* |

| Received BCG (ref = No) | |||||

| Yes | -0.384*** | -0.436*** | -0.427*** | -0.535*** | -99.177*** |

| Received vitamin A (ref = No) | |||||

| Yes | -0.277*** | -0.159*** | -0.179*** | -0.198** | -0.228* |

| Wealth index (ref = Poorest) | |||||

| Poorer | 0.027 | -0.012 | -0.036* | -0.036* | -0.234** |

| Middle | 0.109* | 0.054*** | 0.049* | 0.028** | -0.056*** |

| Richer | 0.198** | 0.139** | 0.058*** | 0.03*** | -0.082*** |

| Richest | 0.31** | 0.314*** | 0.282** | 0.326*** | 0.144** |

| Intercept | -1.519** | -0.61 | -0.078 | 0.423 | 100.867** |

Notes: p–value<0.01***, 0.01<p–value<0.05**, 0.05<p–value<0.1*.

Fig 2. Elasticity (95% confidence interval) of the significant estimates at all considered quantiles.

Breastfeeding duration was found to have a varied negative association with the HAZ score; however, the association was not significant for a duration of less than 12 months at the 25th and 90th quantiles. BCG vaccine and vitamin A receiving status and the HAZ score were also significantly inversely correlated; however, the strength of the association varied across the conditional HAZ distribution. Although the magnitude of the effect of antenatal care visits increased with the number of visits, the association was not significant at some quantiles. More than seven antenatal care visits were positively associated with the HAZ score, except at the 90th quantile; however, the association was reversed for less than or equal to seven antenatal care visits. In addition, the HAZ score and place of delivery were significantly correlated across all quantiles. The coefficient against home delivery had a negative sign at all quantiles, and its absolute value declined from the lower to the upper quantile. The children who were born at home were comparatively shorter than those born at health facilities, particularly, 0.16 SD and 0.13 SD shorter at 10th and 25th quantiles, respectively. Additionally, except at the 50th quantile, children of mothers older than 18 years exhibited a significant height advantage over those whose mothers were 18 years or younger. Specifically, mothers 35 years or older had children who were 0.45 SD taller than those whose mothers were 18 years or younger at the 90th quantile. At the 90th quantile compared to the 10th quantile, the age groups 19–24, 25–34, and 35+ had 47, 8, and 4 times higher effects on HAZ scores, respectively. There was also a significant positive association between the HAZ score and the mother’s BMI, and the extent of the association increased as the mother’s BMI increased. The conditional HAZ distribution was largely affected by the mother’s BMI at the upper quantiles. Compared to children with underweight mothers, the children whose mothers were normal or overweight were taller. Notably, overweight mothers had children who were 0.32 SD, 0.37 SD, and 0.34 SD taller than those whose mothers were underweight at the 50th, 75th, and 90th quantiles, respectively (Table 2).

Furthermore, parental secondary or above education had a significant but varied effect throughout the conditional HAZ distribution. Compared to children of illiterate parents, children of highly educated parents had higher HAZ scores; however, when the mother’s higher education was measured at the 50th quantile, the situation was reversed. Surprisingly, compared to parents who were illiterate, both higher educated fathers and mothers had a positive contribution of around 0.3 SD on their child’s HAZ at the 10th quantile; however, the mother’s higher education was found to be less important (0.17 SD) than the father’s higher education (0.35 SD) for determining the HAZ score at the 25th quantile. The wealth index was also significantly associated with the HAZ score; however, the coefficient for poorer family was insignificant at 10th and 25th quantiles. As household economic status improved, the wealth index’s effect increased, becoming more evident at the lower tail of the conditional HAZ distribution. At the 10th, 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles, children from the richest families were around 0.30 SD taller than those from the poorest families, but the rate decreased to half at the 90th quantile. As well, except at the 10th quantile, the coefficient of urban children was found to have a positive effect on the HAZ score; however, the coefficient was only statistically significant at the 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles. At the higher quantiles, urban living areas had a greater impact on the HAZ score. The urban children were 0.09 SD taller than their rural counterparts at the 50th quantile. Religion also showed a significant relationship with the conditional HAZ distribution, with the positive sign of the coefficients against non-Muslim children at the 10th, 75th, and 90th quantiles (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of stunting and heterogeneous effect of the related risk factors among Bangladeshi children under the age of five were described using a sequential quantile regression model, which is useful to obtain robust estimates of the heterogeneous effect in the presence of outliers or abnormalities in the data [58,59]. There were significant discrepancies in child stunting status by their characteristics like gender, age, birth order, duration of breastfeeding, BCG vaccine and vitamin A receiving status, and place of delivery; maternal characteristics such as age, BMI, education, number of ANC visits during the pregnancy; father’s education; household’s economic status; and social factors including the type of residence and religion. The child’s HAZ score and the predictors had varying degrees of relationship throughout the conditional HAZ distribution. There are several explanations in the literature for this variation [55,62,63,71,72].

The results revealed that female children in Bangladesh had a height disadvantage compared to male children, which is in line with findings from a prior study carried out in Sri Lanka [62] but contrasts with those from many other studies [63,73–77]. This can result from intra-household gender discrimination, especially in food allocation [62]. Therefore, it is important to consider this scenario when developing child nutritional policy initiatives. Moreover, it was discovered that a child’s age was negatively associated with their HAZ score up to the age of 47 months, thereafter, an inverse pattern was observed for 48 to 59 months, except at the 90th quantile. Research carried out in Egypt [55], India [63], and Sri Lanka [62] similarly discovered a negative relationship between a child’s age and their HAZ score. It was also found that children with higher birth orders were shorter than those who were their parents’ firstborn children; however, at some quantiles the opposite was observed. A non-linear relationship between a child’s birth order and HAZ score was discovered in India [63], but it was found to be negative in Sri Lanka [62] and many other low and middle-income countries [78]. This conclusion may be supported by the fact that children with higher birth orders may have received less preference in care [79]. Additionally, our results showed a significant inverse relationship between the child’s HAZ score and the duration of breastfeeding, BCG vaccination, and vitamin A intake; this result contradicts the findings of earlier studies [63,80–85]. In a previous study, breastfeeding was found to have a non-linear negative correlation by age with the HAZ score [63]. The authors recommend more research concentrating on this issue because this study did not fully explain the reason for this conclusion.

In addition, children whose mothers had received antenatal care more than seven times during their pregnancy had higher HAZ scores, whereas children who were born at home had lower HAZ scores. Therefore, antenatal care and place of delivery were identified as protective factors for child stunting. Earlier studies also identified that antenatal care and place of delivery were related to declines in child stunting [7,55,78,86,87]. By receiving antenatal care throughout pregnancy and giving birth in a health facility, both mother and child can be protected from various health complications such as infections, anemia, iron deficiency, and more [55]. As well, the risk of the child’s stunting declines due to the enhanced knowledge and awareness regarding proper diet and health care, and the timely identification of any prevalent health issues learnt by the pregnant women from the health care providers during their antenatal visits and child birth at a health facility [87,88]. A study carried out in India, however, found a non-linear U-shaped association between the number of antenatal visits and HAZ score [63].

Moreover, it was discovered that the mother’s age and BMI had a significant positive association with the child’s HAZ score, which is in line with the findings of earlier studies [55,86]. However, a different study found that the mother’s BMI and the child’s HAZ score have a non-linear positive relationship, while the mother’s age and the child’s HAZ score have an inverse U-shaped relationship [63]. Researchers also found that delaying the age at which mothers have their first child by one year will reduce the rate of stunting by 9% in Ethiopia [86] and 7% in Kenya [89]. Similarly, the rate of stunting will decrease by 4% in Ethiopia [86] and 3% in India [90] for every unit increase in the mother’s BMI. The urgency of limiting teenage births is emphasized by the relationship between the mother’s BMI and the child’s HAZ score [55].

Furthermore, a child’s HAZ score was significantly influenced by parental education; children with secondary or higher educated parents had a significant height advantage over those whose parents were illiterate. Many previous studies reported similar findings regarding the relationship between parental education and HAZ score [10,55,62,63,91–96]. It is well documented that parental education is required to improve a child’s health, nutrition, and survival since educated parents are more likely to be conscious of health, hygiene, and nutrition issues [55]. Previously, it was reported that a mother’s education had a causal nurturing influence on the health of adopted children, as measured by HAZ [55,72]. However, evidence from many countries suggests that knowledge and practices are important pathways, even though the precise mechanism by which parental education influences child outcomes is not well understood [93]. Alongside this, it is widely accepted that better education leads to higher earnings. As a result, higher family earnings allow parents to spend more on health care and good nutrition for their children, which may explain why children of educated parents have a lower risk of stunting [97]. Other related factors like antenatal care visits and a facility based delivery are also influenced by parental education [98,99]. Access to the mass media helps mothers become more knowledgeable about a wide range of subjects [100]. Therefore, it is recommended to incorporate health and nutrition-related education in mass media programs and the academic educational process in Bangladesh.

Moreover, children of middle-income, more affluent, and the wealthiest families had better HAZ scores than children from the poorest families, which is consistent with the findings of earlier studies [55,63]. This finding is also corroborated by the outcomes from many other studies, indicating that the household economic condition is an important factor in the child’s nutritional status in developing countries [10,101–103]. Due to inadequate food consumption, a lack of accessibility to basic health care, and a higher risk of infection, children from lower-income families were more likely to be stunted than children from higher-income families [104–109]. Wealthier families are typically capable of providing better medical treatment, more nutrient-dense food, and an improved and healthier living environment [55,92]. Further, antenatal care and institutional delivery are highly linked to one’s wealth [110–112]. Furthermore, disparities in the child’s HAZ score by the type of their residence were observed in favor of urban children at upper quantiles of the conditional HAZ distribution. This result aligns with research conducted in Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen [55,113]. The income disparity between urban and rural households could be the reason of this finding [55]. Non-Muslim children were also found to have significantly higher HAZ scores than their Muslim counterparts. A similar finding has been reported in earlier studies [63,80,114]. This finding may be because non-Muslim mothers were more likely to visit a health facility for antenatal care during their pregnancy and give birth in a health facility [114].

Conclusions

In this study, the authors estimated the robust measure of the heterogeneous influence of some selected child, maternal, household, and health-related characteristics using a QR model along different quantiles of the conditional HAZ distribution of under five children. This study discovered lower HAZ scores in children who were female, under 48 months old, had higher birth orders, were born at home, had mothers who were 18 years old or younger, were underweight, received seven or fewer antenatal care visits, had parents who were illiterate or had less education, were from households with a lower economic background, resided in rural areas, and were Muslims. Therefore, to lessen the burden of stunting in child malnutrition, the authors recommend that the government, NGOs, and community organizations work collaboratively in designing and implementing effective and appropriate nutritional interventions focusing on vulnerable groups, according to the robust findings of this study. The outcomes of this study will help practitioners and policymakers develop and implement robust and cohesive programs to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals associated with child health outcomes in Bangladesh by 2030.

Supporting information

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA, for providing the Bangladesh DHS datasets for this analysis, and to Charles Sturt University for their research facilities in completing this study. They also thank the academic editor and two reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that helped enhance the manuscript’s quality.

Data Availability

This study is based on the secondary dataset. One can access the data set via the following link http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.de Onis M, Branca F. Childhood stunting: a global perspective. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12: 12–26. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Stunting in a nutshell. In: Geneva: World Health Organization; [Internet]. 2015. [cited 12 Mar 2022]. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/19-11-2015-stunting-in-a-nutshell. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382: 427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eshete T, Kumera G, Bazezew Y, Marie T, Alemu S, Shiferaw K. The coexistence of maternal overweight or obesity and child stunting in low-income country: Further data analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia demographic health survey (EDHS). Sci African. 2020;9: e00524. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF, WHO, World Bank. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2020 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Geneva: WHO. 2020. Available: https://www.unicef.org/media/69816/file/Joint-malnutrition-estimates-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sultana P, Rahman MM, Akter J. Correlates of stunting among under-five children in Bangladesh: A multilevel approach. BMC Nutr. 2019;5. doi: 10.1186/s40795-019-0304-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Islam MS, Zafar Ullah AN, Mainali S, Imam MA, Hasan MI. Determinants of stunting during the first 1,000 days of life in Bangladesh: A review. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8: 4685–4695. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, White RA, Donner AJ, et al. Trends in mild, moderate, and severe stunting and underweight, and progress towards MDG 1 in 141 developing countries: a systematic analysis of population representative data. Lancet. 2012;380: 824–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60647-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNICEF. Bangladesh sees sharp decline in child malnutrition, while violent disciplining of children rises, new survey reveals. In: UNICEF [Internet]. 2020 [cited 15 Apr 2022]. Available: https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/press-releases/bangladesh-sees-sharp-decline-child-malnutrition-while-violent-disciplining-children.

- 10.Chowdhury TR, Chakrabarty S, Rakib M, Afrin S, Saltmarsh S, Winn S. Factors associated with stunting and wasting in children under 2 years in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2020;6: e04849. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setianingsih, Permatasari D, Sawitri E, Ratnadilah D Impact of Stunting on Development of Children Aged 12–60 Months. Adv Heal Sci Res. 2020;27: 186–189. doi: 10.2991/ahsr.k.200723.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Policy Brief Series. World Heal Organ. 2014. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/665585/retrieve. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNICEF. Stop Stunting in South Asia: A Common Narrative on Maternal and Child Nutrition | UNICEF South Asia. 2015. Available: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/reports/stop-stunting-south-asia-common-narrative-maternal-and-child-nutrition.

- 14.Development Initiatives. 2020 Global Nutrition Report: Action on equity to end malnutrition. Glob Nutr Report’s Indep Expert Gr. Bristol, UK; 2020. Available: https://globalnutritionreport.org/documents/566/2020_Global_Nutrition_Report_2hrssKo.pdf.

- 15.Headey D, Heidkamp R, Osendarp S, Ruel M, Scott N, Black R, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. Lancet. 2020;396: 519–521. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31647-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etzel RA. Reducing malnutrition: Time to consider potential links between stunting and mycotoxin exposure? Pediatrics. 2014. pp. 4–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adhikari RP, Shrestha ML, Acharya A, Upadhaya N. Determinants of stunting among children aged 0–59 months in Nepal: Findings from Nepal Demographic and health Survey, 2006, 2011, and 2016. BMC Nutr. 2019;5: 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40795-019-0300-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tydeman-Edwards R, Van Rooyen FC, Walsh CM. Obesity, undernutrition and the double burden of malnutrition in the urban and rural southern Free State, South Africa. Heliyon. 2018;4: e00983. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modern G, Sauli E, Mpolya E. Correlates of diarrhea and stunting among under-five children in Ruvuma, Tanzania; a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Sci African. 2020;8: e00430. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akram R, Sultana M, Ali N, Sheikh N, Sarker AR. Prevalence and Determinants of Stunting Among Preschool Children and Its Urban–Rural Disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39: 521–535. doi: 10.1177/0379572118794770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manggala AK, Kenwa KWM, Kenwa MML, Sakti AAGDPJ, Sawitri AAS. Risk factors of stunting in children aged 24–59 months. Paediatr Indones. 2018;58: 205–212. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hailu BA, Bogale GG, Beyene J. Spatial heterogeneity and factors influencing stunting and severe stunting among under-5 children in Ethiopia: spatial and multilevel analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10: 16427. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73572-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budhathoki SS, Bhandari A, Gurung R, Gurung A, Kc A. Stunting Among Under 5-Year-Olds in Nepal: Trends and Risk Factors. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24: 39–47. doi: 10.1007/s10995-019-02817-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Kim R, Vollmer S, Subramanian S V. Factors Associated With Child Stunting, Wasting, and Underweight in 35 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3: e203386. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wali N, Agho KE, Renzaho AMN. Factors Associated with Stunting among Children under 5 Years in Five South Asian Countries (2014–2018): Analysis of Demographic Health Surveys. Nutrients. 2020;12: 3875. doi: 10.3390/nu12123875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinha B, Taneja S, Chowdhury R, Mazumder S, Rongsen-Chandola T, Upadhyay RP, et al. Low-birthweight infants born to short-stature mothers are at additional risk of stunting and poor growth velocity: Evidence from secondary data analyses. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14: e12504. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indriani D, Lanti Y, Dewi R, Murti B, Qadrijati I. Prenatal Factors Associated with the Risk of Stunting: A Multilevel Analysis Evidence from Nganjuk, East Java. J Matern Child Heal. 2018;3: 294–300. doi: 10.26911/thejmch.2018.03.04.07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan S, Zaheer S, Safdar NF. Determinants of stunting, underweight and wasting among children < 5 years of age: Evidence from 2012–2013 Pakistan demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2019. p. 358. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6688-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wicaksono F, Harsanti T. Determinants of stunted children in Indonesia: A multilevelanalysis at the individual, household, and community levels. Kesmas. 2020;15: 48–53. doi: 10.21109/kesmas.v15i1.2771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekholuenetale M, Barrow A, Ekholuenetale CE, Tudeme G. Impact of stunting on early childhood cognitive development in Benin: evidence from Demographic and Health Survey. Egypt Pediatr Assoc Gaz. 2020;68: 31. doi: 10.1186/s43054-020-00043-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das S, Chanani S, Shah More N, Osrin D, Pantvaidya S, Jayaraman A. Determinants of stunting among children under 2 years in urban informal settlements in Mumbai, India: evidence from a household census. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2020;39: 10. doi: 10.1186/s41043-020-00222-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astatkie A. Dynamics of stunting from childhood to youthhood in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Young Lives panel data. Assefa Woreta S, editor. PLoS One. 2020;15: e0229011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fawzi MCS, Andrews KG, Fink G, Danaei G, McCoy DC, Sudfeld CR, et al. Lifetime economic impact of the burden of childhood stunting attributable to maternal psychosocial risk factors in 137 low/middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4: e001144. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agedew E, Chane T. Prevalence of Stunting among Children Aged 6–23 Months in Kemba Woreda, Southern Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. Adv Public Heal. 2015;2015: 1–6. doi: 10.1155/2015/164670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazengia AL, Biks GA. Predictors of stunting among school-age children in Northwestern Ethiopia. J Nutr Metab. 2018;2018: 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2018/7521751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta AK, Santhya KG. Proximal and contextual correlates of childhood stunting in India: A geo-spatial analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15: e0237661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rachmi CN, Agho KE, Li M, Baur LA. Stunting, Underweight and Overweight in Children Aged 2.0–4.9 Years in Indonesia: Prevalence Trends and Associated Risk Factors. Zhang Y, editor. PLoS One. 2016;11: e015476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mediani HS. Predictors of Stunting Among Children Under Five Year of Age in Indonesia: A Scoping Review. Glob J Health Sci. 2020;12: 83–95. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v12n8p83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nshimyiryo A, Hedt-Gauthier B, Mutaganzwa C, Kirk CM, Beck K, Ndayisaba A, et al. Risk factors for stunting among children under five years: A cross-sectional population-based study in Rwanda using the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19: 175. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6504-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabaoarisoa CR, Rakotoarison R, Rakotonirainy NH, Mangahasimbola RT, Randrianarisoa AB, Jambou R, et al. The importance of public health, poverty reduction programs and women’s empowerment in the reduction of child stunting in rural areas of Moramanga and Morondava, Madagascar. Simeoni U, editor. PLoS One. 2017;12: e0186493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boah M, Azupogo F, Amporfro DA, Abada LA. The epidemiology of undernutrition and its determinants in children under five years in Ghana. Zereyesus Y, editor. PLoS One. 2019;14: e0219665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berhe K, Seid O, Gebremariam Y, Berhe A, Etsay N. Risk factors of stunting (chronic undernutrition) of children aged 6 to 24 months in Mekelle City, Tigray Region, North Ethiopia: An unmatched case-control study. Puebla I, editor. PLoS One. 2019;14: e0217736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaya S, Uthman OA, Kunnuji M, Navaneetham K, Akinyemi JO, Kananura RM, et al. Does economic growth reduce childhood stunting? A multicountry analysis of 89 Demographic and Health Surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5: e002042. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Habimana S, Biracyaza E. Risk Factors Of Stunting Among Children Under 5 Years Of Age In The Eastern And Western Provinces Of Rwanda: Analysis Of Rwanda Demographic And Health Survey 2014/2015. Pediatr Heal Med Ther. 2019;10: 115–130. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S222198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farah AM, Nour TY, Endris BS, Gebreyesus SH. Concurrence of stunting and overweight/obesity among children: Evidence from Ethiopia. Steinberg N, editor. PLoS One. 2021;16: e0245456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall J, Walton M, Ogtrop F Van, Guest D, Black K, Beardsley J. Factors influencing undernutrition among children under 5 years from cocoa-growing communities in Bougainville Handling editor Sanni Yaya. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5: e002478. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prüss A, Kay D, Fewtrell L, Bartram J. Estimating the burden of disease from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110: 537–542. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1240845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown J, Cairncross S, Ensink JHJ. Water, sanitation, hygiene and enteric infections in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98: 629–634. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cumming O, Cairncross S. Can water, sanitation and hygiene help eliminate stunting? Current evidence and policy implications. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12: 91–105. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaivada T, Akseer N, Akseer S, Somaskandan A, Stefopulos M, Bhutta ZA. Stunting in childhood: An overview of global burden, trends, determinants, and drivers of decline. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112: 777S–791S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Das S, Gulshan J. Different forms of malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh: A cross sectional study on prevalence and determinants. BMC Nutr. 2017;3: 1. doi: 10.1186/s40795-016-0122-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hasan MT, Soares Magalhaes RJ, Williams GM, Mamun AA. The role of maternal education in the 15-year trajectory of malnutrition in children under 5 years of age in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12: 929–939. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Talukder A. Factors Associated with Malnutrition among Under-Five Children: Illustration using Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2014 Data. Children. 2017;4: 88. doi: 10.3390/children4100088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman A. Significant Risk Factors for Childhood Malnutrition: Evidence from an Asian Developing Country. Sci J Public Heal Spec Issue Child Malnutrition Dev Ctries. 2016;4: 16–27. doi: 10.11648/j.sjph.s.2016040101.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharaf MF, Mansour EI, Rashad AS. Child nutritional status in Egypt: a comprehensive analysis of socio-economic determinants using a quantile regression approach. J Biosoc Sci. 2019;51: 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0021932017000633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hossain MM. Proposed Mean (Robust) in the Presence of Outlier. J Stat Appl Probab Lett. 2016;3: 103–107. doi: 10.18576/jsapl/030301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hossain MM. Variance in the Presence of Outlier: Weighted Variance. J Stat Appl Probab Lett. 2017;4: 57–59. doi: 10.18576/jsapl/040203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeh CC, Wang KM, Suen YB. Quantile analyzing the dynamic linkage between inflation uncertainty and inflation. Probl Perspect Manag. 2009;7: 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olsen CS, Clark AE, Thomas AM, Cook LJ. Comparing least-squares and quantile regression approaches to analyzing median hospital charges. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19: 866–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Borooah VK. The height-for-age of Indian children. Econ Hum Biol. 2005;3: 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hossain MM, Majumder AK. Determinants of the age of mother at first birth in Bangladesh: quantile regression approach. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2019;27: 419–424. doi: 10.1007/s10389-018-0977-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aturupane H, Deolalikar AB, Gunewardena D. Determinants of Child Weight and Height in Sri Lanka: A Quantile Regression Approach. In: McGillivray M, Dutta I, Lawson D, editors. Health Inequality and Development. Studies in Development Economics and Policy, Palgrave Macmillan, London; 2011. doi: 10.1057/9780230304673_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fenske N, Burns J, Hothorn T, Rehfuess EA. Understanding child stunting in India: A comprehensive analysis of socio-economic, nutritional and environmental determinants using additive quantile regression. PLoS One. 2013;8: e78692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abdulla F, El-Raouf MMA, Rahman A, Aldallal R, Mohamed MS, Hossain MM. Prevalence and determinants of wasting among under-5 Egyptian children: Application of quantile regression. Food Sci Nutr. 2022; 1–11. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hossain MM, Abdulla F, Rahman A. Prevalence and determinants of wasting of under-5 children in Bangladesh: Quantile regression approach. PLoS One. 2022;17: e0278097. Available: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), ICF. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA; 2020.

- 67.Koenker R, Bassett G. Regression Quantiles. Econometrica. 1978;46: 33–50. doi: 10.2307/1913643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahman A, Hossain MM. Quantile regression approach to estimating prevalence and determinants of child malnutrition. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2022;30: 323–339. doi: 10.1007/S10389-020-01277-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hossain S, Hossain MM, Yeasmin S, Bhuiyea MSH, Chowdhury PB, Khan MTF. Assessing the Determinants of Women’s Age at First Marriage in Rural and Urban Areas of Bangladesh: Insights From Quantile Regression (QR) Approaches. J Popul Soc Stud. 2022;30: 602–624. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yirga AA, Ayele DG, Melesse SF. Application of Quantile Regression: Modeling Body Mass Index in Ethiopia. Open Public Health J. 2018;11: 221–233. doi: 10.2174/1874944501811010221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kabubo-Mariara J, Ndenge GK, Mwabu DK. Determinants of Children’s Nutritional Status in Kenya: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. J Afr Econ. 2009;18: 363–387. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejn024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen Y, Li H. Mother’s education and child health: Is there a nurturing effect? J Health Econ. 2009;28: 413–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thurstans S, Opondo C, Seal A, Wells J, Khara T, Dolan C, et al. Boys are more likely to be undernourished than girls: a systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5: e004030. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aguayo VM, Badgaiyan N, Paintal K. Determinants of child stunting in the Royal Kingdom of Bhutan: an in-depth analysis of nationally representative data. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11: 333–345. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hong R. Effect of economic inequality on chronic childhood undernutrition in Ghana. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10: 371–378. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007226035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K, Sari M, Akhter N, Bloem MW. Effect of parental formal education on risk of child stunting in Indonesia and Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371: 322–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60169-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Boys are more stunted than girls in Sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7: 17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kuhnt J, Vollmer S. Antenatal care services and its implications for vital and health outcomes of children: evidence from 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e017122. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biswas S, Bose K. Sex differences in the effect of birth order and parents’ educational status on stunting: a study on Bengalee preschool children from eastern India. Homo. 2010;61: 271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sk R, Banerjee A, Rana MJ. Nutritional status and concomitant factors of stunting among pre-school children in Malda, India: A micro-level study using a multilevel approach. BMC Public Health. 2021;21: 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11704-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Onyango AW, Esrey SA, Kramer MS. Continued breastfeeding and child growth in the second year of life: a prospective cohort study in western Kenya. Lancet. 1999;354: 2041–2045. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ssentongo P, Ba DM, Ssentongo AE, Fronterre C, Whalen A, Yang Y, et al. Association of vitamin A deficiency with early childhood stunting in Uganda: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15: e0233615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim R, Mejía-Guevara I, Corsi DJ, Aguayo VM, Subramanian S V. Relative importance of 13 correlates of child stunting in South Asia: Insights from nationally representative data from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. Soc Sci Med. 2017;187: 144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sato R. Association between uptake of selected vaccines and undernutrition among Nigerian children. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17: 2630–2638. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1880860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berendsen MLT, Smits J, Netea MG, van der Ven A. Non-specific Effects of Vaccines and Stunting: Timing May Be Essential. EBioMedicine. 2016;8: 341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Amaha ND, Woldeamanuel BT. Maternal factors associated with moderate and severe stunting in Ethiopian children: analysis of some environmental factors based on 2016 demographic health survey. Nutr J. 2021;20: 18. doi: 10.1186/s12937-021-00677-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haq W, Abbas F. A Multilevel Analysis of Factors Associated With Stunting in Children Less Than 2 years Using Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2017–18 of Punjab, Pakistan. SAGE Open. 2022;12: 21582440221096130. doi: 10.1177/21582440221096127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hamel C, Enne J, Omer K, Ayara N, Yarima Y, Cockcroft A, et al. Childhood malnutrition is associated with maternal care during pregnancy and childbirth: A cross-sectional study in Bauchi and cross river states, Nigeria. J Public health Res. 2015;4: 58–64. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2015.408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gewa CA, Yandell N. Undernutrition among Kenyan children: contribution of child, maternal and household factors. Public Health Nutr. 2011/11/23. 2012;15: 1029–1038. doi: 10.1017/S136898001100245X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Subramanian S V, Ackerson LK, Smith GD. Parental BMI and Childhood Undernutrition in India: An Assessment of Intrauterine Influence. Pediatrics. 2010;126: e663–e671. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rahman A, Hossain MM. Quantile regression approach to estimating prevalence and determinants of child malnutrition. J Public Heal. 2022;30: 323–339. doi: 10.1007/S10389-020-01277-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rahman A, Chowdhury S. Determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children in Bangladesh. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39: 161–173. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baig-Ansari N, Rahbar MH, Bhutta ZA, Badruddin SH. Child’s Gender and Household Food Insecurity are Associated with Stunting among Young Pakistani Children Residing in Urban Squatter Settlements. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27: 114–127. doi: 10.1177/156482650602700203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tiwari R, Ausman LM, Agho KE. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives: evidence from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14: 239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ikeda N, Irie Y, Shibuya K. Determinants of reduced child stunting in Cambodia: analysis of pooled data from three Demographic and Health Surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91: 341–349. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Akombi BJ, Agho KE, Hall JJ, Merom D, Astell-Burt T, Renzaho AMN. Stunting and severe stunting among children under-5 years in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17: 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0770-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chowdhury TR, Chakrabarty S, Rakib M, Saltmarsh S, Davis KA. Socio-economic risk factors for early childhood underweight in Bangladesh. Global Health. 2018;14: 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0372-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K, Campbell AA, Bloem MW, Raju VK. Low intake of vitamin A-rich foods among children, aged 12–35 months, in India: Association with malnutrition, anemia, and missed child survival interventions. Nutrition. 2010;26: 958‑962. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tadesse E. Antenatal Care Service Utilization of Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care in Public Hospitals During the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12: 1181–1188. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S287534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hossain MM, Saleh A Bin, Kabir MA. Determinants of mass media exposure and involvement in information and communication technology skills among Bangladeshi women. Jahangirnagar Univ J Stat Stud. 2022;36: 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meshram II, Arlappa N, Balakrishna N, Laxmaiah A, Rao KM, Gal Reddy C, et al. Prevalence and determinants of undernutrition and its trends among pre-school tribal children of maharashtra state, India. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58: 125–132. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hong R, Mishra V. Effect of wealth inequality on chronic under-nutrition in Cambodian children. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2006;24: 89–99. doi: 10.3329/JHPN.V24I1.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kien VD, Lee H-Y, Nam Y-S, Oh J, Giang KB, Minh H Van. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in child malnutrition in Vietnam: findings from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, 2000–2011. Glob Health Action. 2016;9: 29263. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.29263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, Walker DG, Brieger WR, Hafizur Rahman M. Poverty and Access to Health Care in Developing Countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136: 161–171. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hansen C, Paintsil E. Infectious Diseases of Poverty in Children: A Tale of Two Worlds. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63: 37–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tazinya AA, Halle-Ekane GE, Mbuagbaw LT, Abanda M, Atashili J, Obama MT. Risk factors for acute respiratory infections in children under five years attending the Bamenda Regional Hospital in Cameroon. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18: 7. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0579-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thörn LKAM, Minamisava R, Nouer SS, Ribeiro LH, Andrade AL. Pneumonia and poverty: a prospective population-based study among children in Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11: 180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.French SA, Tangney CC, Crane MM, Wang Y, Appelhans BM. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: the SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19: 231. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6546-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shuvo S Das, Hossain MS, Riazuddin M, Mazumdar S, Roy D. Factors influencing low-income households’ food insecurity in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS One. 2022;17: e0267488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Agha S, Williams E. Quality of antenatal care and household wealth as determinants of institutional delivery in Pakistan: Results of a cross-sectional household survey. Reprod Health. 2016;13: 84. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0201-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Arthur E. Wealth and antenatal care use: implications for maternal health care utilisation in Ghana. Health Econ Rev. 2012;2: 14. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-2-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mustafa MH, Mukhtar AM. Factors associated with antenatal and delivery care in Sudan: Analysis of the 2010 Sudan household survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15: 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1128-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sharaf MF, Rashad AS. Regional inequalities in child malnutrition in Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen: a Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6: 23. doi: 10.1186/s13561-016-0097-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kachoria AG, Mubarak MY, Singh AK, Somers R, Shah S, Wagner AL. The association of religion with maternal and child health outcomes in South Asian countries. PLoS One. 2022;17: e0271165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]