Abstract

We investigated the association of SARS CoV-2 vaccination with COVID-19 severity in a longitudinal study of adult cancer patients with COVID-19. A total of 1610 patients who were within 14 days of an initial positive SARS CoV-2 test and had received recent anticancer treatment or had a history of stem cell transplant or CAR-T cell therapy were enrolled between May 21, 2020, and February 1, 2022. Patients were considered fully vaccinated if they were 2 weeks past their second dose of mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) or a single dose of adenovirus vector vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S) at the time of positive SARS CoV-2 test. We defined severe COVID-19 disease as hospitalization for COVID-19 or death within 30 days. Vaccinated patients were significantly less likely to develop severe disease compared with those who were unvaccinated (odds ratio = 0.44, 95% confidence interval = 0.28 to 0.72, P < .001). These results support COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients receiving active immunosuppressive treatment.

Individuals with cancer on immunosuppressive treatment are at higher risk of severe disease associated with SARS CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 (1,2). Patients with cancer were among those initially eligible for COVID-19 vaccines when they became available by emergency use authorization in December 2020 (3). However, the immunosuppressive effects of cancer therapy (particularly B-cell–depleting therapy) may blunt immune response to vaccination, potentially leaving those at high risk still vulnerable to severe disease (4-6). We therefore sought to investigate the association of SARS CoV-2 vaccination with COVID-19 severity in adults on active cancer treatment.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) COVID-19 and Cancer Patients Study (NCCAPS; NCT04387656) is a prospective, longitudinal study that enrolled cancer patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at sites participating in 3 NCI cancer clinical trials networks: National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN), Experimental Therapeutics Clinical Trial Network (ETCTN), and NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP). All patients provided written informed consent. Eligible patients were within 14 days of their initial positive SARS CoV-2 test and had received active anticancer treatment within 6 weeks or had a history of stem cell transplant or CAR-T cell therapy. Baseline and longitudinal study data were collected by clinical research staff at enrolling sites as outlined in Supplementary Methods (available online). This analysis includes 1610 adult patients enrolled between May 21, 2020, and February 1, 2022. Patients were considered fully vaccinated if they were 2 weeks past their second dose of mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) or a single dose of adenovirus vector vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S). Because of missing data, booster doses were not considered in this analysis. For patients with otherwise complete data but unknown vaccination status, we imputed a status of “not fully vaccinated” if the positive SARS CoV-2 test date was before February 1, 2021, based on limited initial vaccine availability and time required to be fully vaccinated. Patients were classified as having severe disease if they were hospitalized for COVID-19 or died within 30 days of their first positive SARS CoV-2 test. This endpoint was chosen for comparability with other reports on vaccine efficacy (7,8) and to reduce potential confounding from malignancy-related deaths after recovery from acute COVID-19.

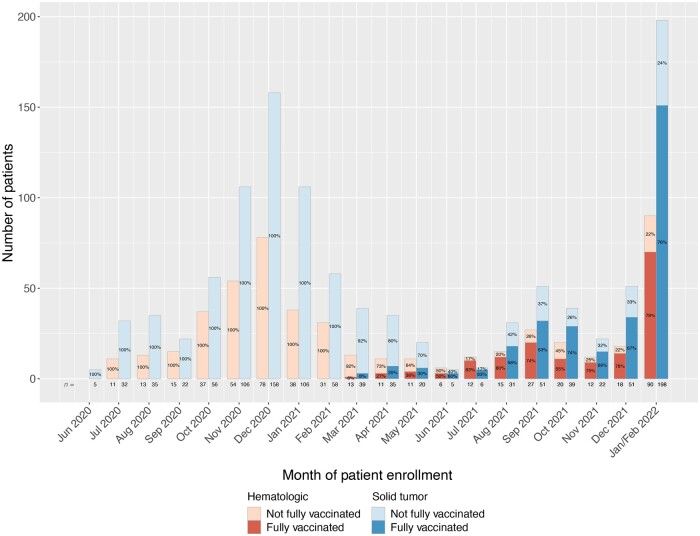

Accruals to NCCAPS are shown in Figure 1 by vaccine status and malignancy type and detailed in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). Throughout the study period, one-third of enrollments were patients with hematologic malignancies. Mirroring COVID-19 case counts, we saw a peak in study enrollments between December 2020 and January 2021, a second smaller peak in September 2021, and a third peak between December 2021 and January 2022. We observed an increase in the proportion of vaccinated patients among study enrollees starting in July 2021, corresponding approximately to the time period when the Delta variant was the dominant SARS CoV-2 strain in the United States (9). Although the number of enrollments in July 2021 was small (n = 18), 83% of these patients were fully vaccinated when they developed COVID-19, and the majority of enrollments from that point onward were among fully vaccinated patients. Although this may partially reflect high vaccination uptake among individuals with cancer, it also suggests that breakthrough infections became more frequent among cancer patients on active treatment with the Delta and Omicron variants. The low overall enrollment in May 2021-July 2021 may reflect more complete vaccine protection among cancer patients before emergence of these variants.

Figure 1.

National Cancer Institute COVID-19 and Cancer Patients Study monthly accrual by vaccination status and malignancy type (solid tumor vs hematologic malignancy). May 2020 to January or February 2022. January and February 2022 are combined as the last day of patient enrollment before closure of the study to new enrollments was February 1, 2022.

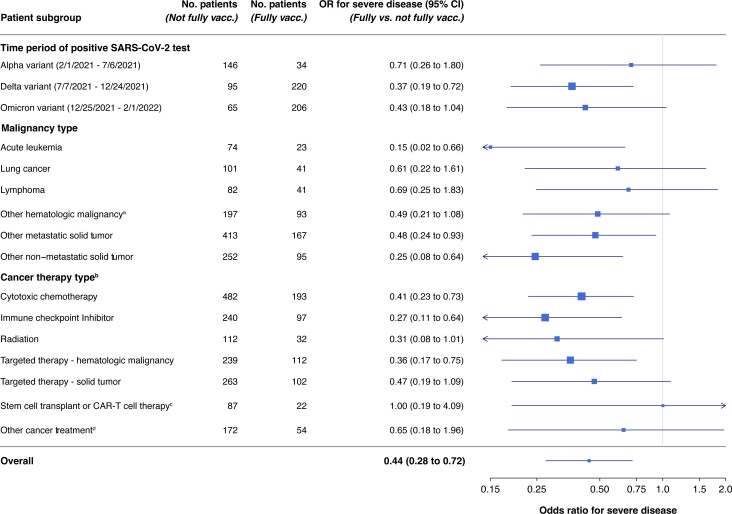

To determine whether vaccine status at the time of SARS CoV-2 infection was associated with severity of disease, we conducted logistic regression analysis in 1580 patients with complete data for all adjustment variables. Models were selected by comparing corrected Akaike Information Criterion (10) for all combinations of covariates preselected for potential clinical relevance as described in the Supplementary Methods (available online). The selected model controlled for age, sex, combined race and ethnicity, malignancy category, time period, diabetes, body mass index category, COVID-19 treatments (convalescent plasma, antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, or other), and cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, stem cell transplant). Time periods were defined based on the dominant SARS CoV-2 strain in the United States (Figure 2). Additional sensitivity analyses are described in the Supplementary Methods (available online); data missingness is described in Supplementary Table 2 (available online).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for severe disease by vaccination status in subgroups by time period, malignancy type, and cancer treatment type. Point estimate indicator size is proportional to the size of the subgroup, and confidence intervals that extend past the axis are truncated and denoted with an arrow at the axis limit. aIncludes chronic leukemias, multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes. bFor all therapy types except transplant, patients were included in the treatment group if they had received this type of treatment within 6 weeks before COVID-19 diagnosis. Patients may be in more than 1 treatment group if they were on multiple treatment types at the time of COVID diagnosis. cPatients were included in this category if they had received autologous or allogenic stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant or CAR-T cell therapy any time before diagnosis of COVID-19. dIncludes endocrine therapy, local therapies (ie, intrathecal, intrahepatic, intralesional), hydroxyurea, octreotide, BCG, and radionuclide therapies.

Vaccinated patients were significantly less likely to develop severe disease compared with those who were unvaccinated or partially vaccinated at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis (odds ratio = 0.44, 95% confidence interval = 0.28 to 0.72, P < .001). The association of vaccination with the absence of severe disease was seen in all time periods, disease categories, and treatment categories (Figure 2), except for prior stem cell transplant or CAR-T cell therapy, though the numbers were small in that group. Importantly, protection from severe disease was observed among patients receiving targeted therapies for hematologic malignancies, including B-cell–depleting therapies. There was a numerically smaller association in lymphoma patients, though this difference was not statistically significant. Vaccine protection appears less robust in cancer patients than what is reported among the general population, which has been shown to be at least 86% effective against hospitalization, even among those 65 years and older (11).

Despite initial Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for COVID vaccines in December 2020, almost all patients enrolled to NCCAPS before March 2021 were unvaccinated, and only a small proportion of those enrolled from March 2021 to May 2021 were fully vaccinated. This likely reflects both limited initial availability of vaccines during that time period and the protective effect of vaccines against infection with the alpha variant of SARS CoV-2. Starting in July 2021, most patients enrolled to NCCAPS were fully vaccinated. These data suggest that breakthrough infections in cancer patients became more common as new SARS CoV-2 variants emerged. Because our study was not population based, these results may be subject to enrollment biases; for example, patients who were highly symptomatic may have been more likely to seek medical attention, sites may have prioritized enrolling more severe cases, or, conversely, the most severely ill patients may have been uninterested or unwilling to participate. Additionally, our conclusions regarding variants are based on national prevalence data rather than individual-level testing. Finally, total enrollment in some disease subsets was small. Despite these limitations, we found a robust association of SARS CoV-2 vaccination with the absence of severe COVID-19 disease. These results support COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients receiving active immunosuppressive treatment.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Ana F Best, Biometric Research Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Melissa Bowman, Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD, USA.

Jessica Li, Biometric Research Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Grace E Mishkin, Clinical Investigations Branch, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Andrea Denicoff, Clinical Investigations Branch, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Marwa Shekfeh, Biometric Research Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Larry Rubinstein, Biometric Research Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Jeremy L Warner, Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Brian Rini, Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Larissa A Korde, Clinical Investigations Branch, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Funding

No funding was used for this study.

Notes

Role of the funder: Not applicable.

Disclosures: JW: Consulting: Westat, Roche, Melax Tech, Flatiron Health. Ownership (no monetary value): HemOnc.org LLC. BR:Research Funding to Institution: Pfizer, Hoffman-LaRoche, Incyte, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Immunomedics, BMS, Mirati Therapeutics, Merck, Surface Oncology, Aravive, Exelixis, Jannsen, Pionyr, AVEO. Consulting: BMS, Pfizer, GNE/Roche, Aveo, Synthorx, Merck, Corvus, Surface Oncology, Aravive, Alkermes, Arrowhead, Shionogi, Eisai, Nikang Therapeutics, EUSA, Athenex, Allogene Therapeutics, Debiopharm. Stock: PTC therapeutics. Other authors: nothing to disclose.

Author contributions: Larry Rubinstein, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing – review & editing), Marwa Shekfeh, PhD (Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing), Jeremy L Warner, MD, MS (Data curation; Writing – review & editing), Larissa Korde, MD, MPH (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft), Brian Rini, MD (Conceptualization; Writing – review & editing), Melissa Bowman, MS (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Project administration; Validation; Writing – review & editing), Ana F Best, PhD (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Visualization), Jessica Li, MPH (Data curation; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing), Andrea Denicoff, RN, MS (Conceptualization; Investigation; Project administration; Writing – original draft), Grace E Mishkin, PhD, MPH (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – review & editing).

Acknowledgements: The study team would like to acknowledge the participating patients and enrolling sites, the members of the NCCAPS Working Group, Megan Stine and Patty Griffin for database support, and Sanjay Mishra for expertise in SARS CoV-2 viral dynamics.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be available the NCTN/NCORP Data archive at https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/ and can be accessed with unique identifier: NCT04387656-D1.

References

- 1. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335-337. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):894-901. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The advisory committee on immunization practices' interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(49):1857-1859. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shroff RT, Chalasani P, Wei R, et al. Immune responses to COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in patients with solid tumors on active, immunosuppressive cancer therapy. medRxiv. 2021.05.13.21257129. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.13.21257129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deepak P, Kim W, Paley MA, et al. Glucocorticoids and B cell depleting agents substantially impair immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines to SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. 2021.04.05.21254656. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.05.21254656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simon D, Tascilar K, Schmidt K, et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination in autoimmune disease patients with B cell depletion. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(1):33-37. doi: 10.1002/art.41914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin DY, Gu Y, Xu Y, et al. Association of primary and booster vaccination and prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 outcomes. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1415-1426. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.17876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Semenzato L, Botton J, Baricault B, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against severe COVID-19 outcomes within the French overseas territories: a cohort study of 2-doses vaccinated individuals matched to unvaccinated ones followed up until September 2021 and based on the National Health Data System. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0274309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lambrou AS, Shirk P, Steele MK, et al. ; Strain Surveillance and Emerging Variants NS3 Working Group. Genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants: predominance of the delta (B.1.617.2) and omicron (B.1.1.529) variants - United States, June 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(6):206-211. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7106a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hurvich CM, Tsai C-L.. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika. 1989;76(2):297-307. doi: 10.1093/biomet/76.2.297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosenberg ES, Dorabawila V, Easton D, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(2):116-127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be available the NCTN/NCORP Data archive at https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/ and can be accessed with unique identifier: NCT04387656-D1.