ABSTRACT

Background

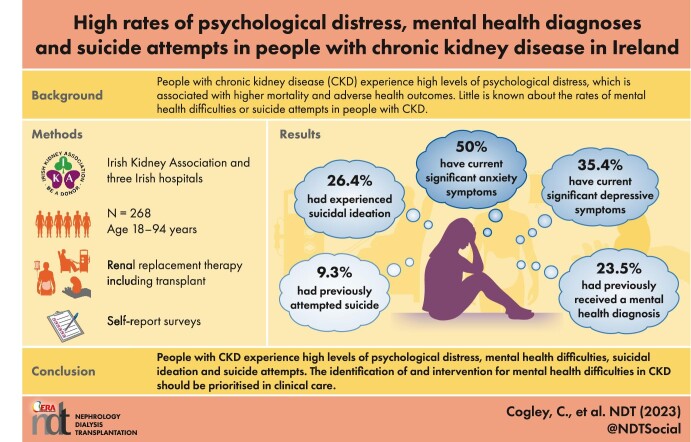

People with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience high levels of psychological distress, which is associated with higher mortality and adverse health outcomes. Little is known about the rates of a range of mental health difficulties or rates of suicide attempts in people with CKD.

Methods

Individuals with CKD (n = 268; age range 18–94 years, mean = 49.96 years) on haemodialysis (n = 79), peritoneal dialysis (n = 46), transplant recipients (n = 84) and who were not on renal replacement therapy (RRT; n = 59) were recruited through the Irish Kidney Association social media pages and three Irish hospitals. Participants completed surveys to gather demographics and mental health histories, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Results

A total of 23.5% of participants self-reported they had received a mental health diagnosis, with depression (14.5%) and anxiety (14.2%) being the most common, while 26.4% of participants had experienced suicidal ideation and 9.3% had attempted suicide. Using a clinical cut-off ≥8 on the HADS subscales, current levels of clinically significant anxiety and depression were 50.7% and 35.4%, respectively. Depression levels were slightly higher for those on haemodialysis compared with those with a transplant and those not on RRT. Depression, anxiety and having a mental health diagnosis were all associated with lower HRQoL.

Conclusions

People with CKD in Ireland experience high levels of psychological distress, mental health difficulties, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. The identification of and intervention for mental health difficulties in CKD should be prioritised in clinical care.

Keywords: kidney disease, kidney failure, mental health, psychological distress, suicide

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What is already known about this subject?

People with chronic kidney disease (CKD) often experience high levels of psychological distress due to decreased physical and cognitive functioning, the burden of treatment and the subsequent effects on relationships, lifestyle and employment.

People with mental health difficulties have an increased risk of developing CKD. Rates of hospitalisations with psychiatric diagnoses are higher for people with kidney failure than other chronic illnesses. Mental health difficulties and psychological distress in CKD populations are associated with higher mortality rates and adverse health outcomes.

However, research regarding the rates of the full range of mental health difficulties in people with CKD is largely limited to US-based inpatient hospitalisation data of people on haemodialysis. Little was known about the psychological distress of people with CKD in Ireland.

What this study adds?

This is the first study describing mental health diagnoses in people with CKD using self-report methods. A total of 23.5% of participants self-reported receiving a mental health-related diagnosis, with depression and anxiety being the most common. Furthermore, 26.4% of participants had experienced suicidal ideation and 9.3% had attempted suicide.

Rates of clinically significant psychological distress are high in people with CKD in Ireland. Levels of clinically significant anxiety and depression were 50.7% and 35.4%, respectively.

Anxiety, depression and having a mental health diagnosis were all associated with poorer mental health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Depression was also associated with poorer physical HRQOL.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

Clinical recognition of the high rates of mental health difficulties, psychological distress and suicide risk in people with CKD is needed.

Routine screening for psychological distress, mental health difficulties and suicide risk should be implemented into clinical practice.

Access to effective mental health care for people with CKD should be prioritised. Nephrology teams should be adequately resourced with mental health professionals, including psychologists, social workers and psychiatrists.

INTRODUCTION

It is well documented that people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) often experience high levels of psychological distress due to decreased physical and cognitive functioning, the burden of treatment and the subsequent effects on relationships, lifestyle and employment [1, 2]. The estimated prevalence of anxiety disorders and elevated anxiety symptoms for individuals with CKD are high, at 19% and 43%, respectively [1]. Anxiety symptoms have been associated with hospitalisation and all-cause mortality in people with CKD [3, 4]. The estimated prevalence of depressive symptoms is 39% for those on dialysis and 25% for transplant recipients [5]. Depression in CKD populations is a known risk factor for higher mortality rates [6], lower treatment adherence [7] and increased healthcare utilisation [8]. Despite the high levels of depression in people with CKD and its known associations with poor health outcomes, only a minority of people receive diagnoses and adequate treatment [9]. Individuals with CKD also have higher rates of suicide than the general population [10, 11]; however, little is known about the rates of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts in people with CKD in Ireland.

Furthermore, people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have higher rates of CKD [12, 13] due to risk factors such as the use of lithium treatment and higher rates of cardiovascular disease [14]. Rates of hospitalisations with psychiatric diagnoses are 1.5–3 times higher for people with kidney failure compared with people with other chronic illnesses [15]. In the USA, 27% of Medicaid-enrolled adults with kidney failure had hospitalisations with a psychiatric diagnosis [16]. Those who had been hospitalised with a psychiatric diagnosis had an increased risk of death compared with those hospitalised without a psychiatric diagnosis. Similarly, having a diagnosis of schizophrenia [17] and hospitalisation for psychosis [18] have each been associated with a higher risk of mortality in people on haemodialysis (HD). However, research regarding the rates of the full range of mental health difficulties in people with CKD is largely limited to US-based inpatient hospitalisation data of people on HD.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is defined as the subjective assessment of functioning and well-being across the physical, psychological and social domains [19]. The symptoms and treatments associated with CKD are known to impair physical and mental HRQOL [20]. Depression and anxiety have been associated with reduced HRQOL for people with CKD [21, 22]. In the general population, people with mental health difficulties have lower HRQOL [23]; however, little is known about the HRQOL of people with CKD who have mental health diagnoses.

We investigated the levels of psychological distress, mental health diagnoses, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in people with CKD in Ireland using self-report surveys. In addition, we examined the extent to which HRQOL is associated with mental health diagnoses and psychological distress. To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing rates of self-reported mental health histories in the CKD population.

Our research questions were:

What are the diagnosed mental health difficulties in people with CKD in Ireland?

What are the rates of suicidal ideation and previous suicide attempts in people with CKD in Ireland?

What are the levels of clinically significant psychological distress in people with CKD in Ireland?

Do rates of mental health diagnoses or levels of psychological distress vary based on renal replacement therapy (RRT) modality, age and gender?

Are mental health diagnoses and psychological distress associated with HRQOL for people with CKD?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional multisite survey. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee at University College Dublin (HS-21-19). An a priori power analyses was conducted using G*Power3 to test the difference between four independent group means using a two-tailed test, an alpha of 0.05 and a medium effect size (Cohen's f = 0.25). A total sample size of 180 participants with four equal-sized groups of 44 participants was required to achieve a power of 0.80.

A total of 268 participants completed the study between November 2021 and August 2022. Participants were recruited online through the Irish Kidney Association social media pages (n = 113) and in three Dublin-based hospitals (n = 155) in the low clearance clinics, HD units, peritoneal dialysis (PD) clinics and transplant clinics. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 94 years {mean 49.96 [standard deviation (SD) 14.41]}. All participants were given the option of completing the survey with the help of a researcher to facilitate those who were unable to complete the questionnaires due to disability or literacy difficulties. To be considered for inclusion, participants had to be >18 years of age, have a diagnosis of CKD and be able to provide informed consent and participate in English. The exclusion criteria were being <18 years of age, not having a diagnosis of CKD and not being able to provide informed consent or participate in English. In the hospital sites, treating clinicians advised who was not physically well enough to approach for recruitment. Of all eligible individuals invited, only four people on HD declined to participate. Individuals from 22 different hospitals and 24 counties in Ireland participated. Additional demographic information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 136 | 50.7 |

| Male | 131 | 48.9 | |

| Non-binary | 1 | 0.03 | |

| RRT (SF-12) modality | Transplant | 84 | 31 |

| HD | 79 | 29 | |

| PD | 46 | 17 | |

| None | 59 | 22 | |

| Level of education | Left school at age 14 or less | 15 | 6 |

| Junior/Inter Cert | 33 | 12 | |

| Leaving Cert | 41 | 15 | |

| Vocational school/diploma | 78 | 29 | |

| University undergraduate | 54 | 20 | |

| University postgraduate | 47 | 18 | |

| Employment status | Working full time | 76 | 28 |

| Working part time | 41 | 15 | |

| Retired | 48 | 18 | |

| On sick leave | 41 | 15 | |

| Unemployed | 33 | 12 | |

| Keeping house | 18 | 7 | |

| Student | 8 | 3 | |

| Looking for work | 4 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | White Irish | 241 | 90 |

| White non-Irish | 14 | 5.2 | |

| Asian, Eastern | 5 | 1.8 | |

| Asian, Indian | 3 | 1.1 | |

| Romanian | 3 | 1.1 | |

| Irish Traveller | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Yearly household income (€) | <30 000 | 91 | 34 |

| 30 001–75 000 | 79 | 29 | |

| >75 000 | 90 | 36 |

Measures

Demographic details were requested regarding gender, age, renal replacement therapy (RRT) modality, level of education, employment status, ethnicity and yearly household income. Participants were asked questions regarding their mental health histories, including whether they had received a mental health diagnosis in the past, had taken psychotropic medication, had attended psychological therapy or a psychiatrist, had spent a night in hospital due to a mental health difficulty, had attempted suicide or had experienced thoughts of suicide. Participants were also asked to what extent the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic had an impact on their mental health.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [24] is a self-report measure for depression and anxiety and is widely used in hospital, outpatient and community settings. The HADS was specifically developed for individuals who are somatically ill and does not include potentially confounding somatic items relating to depression or anxiety. The scale consists of 14 items, equally divided between depression and anxiety subscales. Respondents are asked to choose the response that most accurately reflects how they have been feeling over the last week. The HADS has been validated as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in CKD populations [25].

The 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) [26] is a self-report questionnaire consisting of a physical component score (PCS) and a mental component score (MCS) of HRQOL. The SF-12 is a shortened version of the 36-item Short Form 36 [27] that was created to decrease the response burden for participants. The SF-12 has been validated in CKD populations [27]. The PCS and MCS range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better physical and mental HRQOL.

Statistical analyses

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 18; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analyses. Demographic variables and scales were analysed for missing data. Missing data were handled as follows. Adjusted scores for HADS-A and HADS-D subscales were computed using an 85% criterion, whereby only participants with a minimum of six valid responses out of the seven items were included. Prorated scale scores were then computed. Three people had missing data for two or more items on the HADS, so their data are not reported in this study. The cut-off score of ≥8 was used for the HADS anxiety and depression subscales to determine clinically significant psychological distress [24]. Regarding the SF-12, component PCSs and MCSs were computed and normalised using QualityMetric scoring software (Johnston, RI, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe participant demographics as well as the frequencies of mental health diagnoses and psychological distress. t-Tests were used to compare continuous variables between two groups and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous variables between more than two groups. Pearson chi-squared tests were used to compare frequencies of categorical variables between groups. Bivariate Pearson correlation was used to assess relationships between pairs of continuous variables. A two-sided P-value ≤.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

What are the mental health diagnoses in people with CKD in Ireland?

Of the 268 participants, 63 (23.5%) reported they had received a mental health diagnosis in the past (see Table 2 for a breakdown of mental health diagnoses). Of these, 45 (16.7%) were taking psychotropic medication at the time of data collection, 71 (26.4%) had taken psychotropics and 6 (2.2%) had taken lithium-based psychotropics in the past. A total of 142 (52.9%) had attended psychological therapy, 67 (25%) had seen a psychiatrist and 18 (6.7%) had spent a night in hospital due to a mental health difficulty. Twenty-one (7.8%) reported having addiction problems with alcohol or drugs. Thirty-nine (14.6%) reported they were not able to access professional psychological support when they needed it.

Table 2:

Frequencies of reported mental health diagnoses.

| Mental health diagnosis | n | % of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | 39 | 14.5 |

| Anxiety | 38 | 14.2 |

| Bipolar disorder | 6 | 2.2 |

| PTSD | 4 | 1.5 |

| Psychosis | 2 | 0.7 |

| Schizophrenia | 2 | 0.7 |

| Alcohol addiction | 2 | 0.7 |

| Agoraphobia | 1 | 0.4 |

| ADHD | 1 | 0.4 |

| Bulimia | 1 | 0.4 |

| Anorexia | 1 | 0.4 |

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, 16% of participants reported that it had a large negative impact on their mental health, while 48.9% reported some negative impact, 26.3% reported no impact, 7.3% reported some positive impact and 1.5% reported a large positive impact.

What are the rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in people with CKD in Ireland?

Seventy-one (26.4%) participants reported having had thoughts of suicide and 25 (9.3%) reported having attempted suicide in the past.

What are the levels of psychological distress in people with CKD in Ireland?

Using the HADS, 136 (50.7%) participants had clinically significant levels of anxiety and 95 (35.4%) had clinically significant levels of depression (see Table 3), and 76 (28.4%) had clinically significant levels of both anxiety and depression. The mean levels of anxiety and depression were 7.8 (SD 4.61) and 6.26 (SD 4.31), respectively.

Table 3:

Levels of anxiety and depression in participants.

| Level | Anxiety (HADS-A), n (%) | Depression (HADS-D), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Subclinical (HADS 0–7) | 132 (49.3) | 173 (64.6) |

| Mild (HADS 8–10) | 58 (21.6) | 54 (20.1) |

| Moderate (HADS 11–15) | 56 (20.9) | 28 (10.4) |

| Severe (HADS 16–21) | 22 (8.2) | 13 (4.9) |

Do rates of mental health diagnoses and levels of psychological distress vary based on RRT modality, age and gender?

Chi-squared statistics indicated no differences in frequencies of mental health diagnoses between RRT modalities [χ2(3, N = 268) = 4.16, P = .24]. There were no significant differences in age between those with and without a previous mental health diagnosis [t(268) = −1.08, P = 0.28, d = −0.162]. There was a significantly higher frequency of mental health diagnoses reported in women (28.4%) compared with men (15.7%) [χ2(1, N = 268) = 5.8, P = .016, ϕ = −0.153 (with Yates continuity correction)].

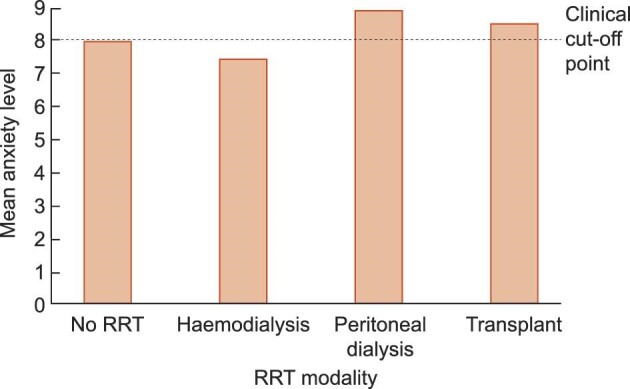

A one-way ANOVA indicated that there was no significant association between anxiety and RRT modality (no treatment, HD, PD or transplant) [F(3265) = 1.42, P = .24, η2 = 0.016]. See Figure 1 for mean anxiety level by RRT modality. Higher anxiety was significantly associated with lower age [r(267) = −0.42, P < .001]. Women had significantly higher levels of anxiety [mean 9.17 (SD 4.45)] than men [mean 6.33 (SD 4.33); t(176) = −2.55, P = .012, d = −0.65].

Figure 1:

Mean anxiety level by RRT modality. HD: haemodialysis; PD: peritoneal dialysis; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

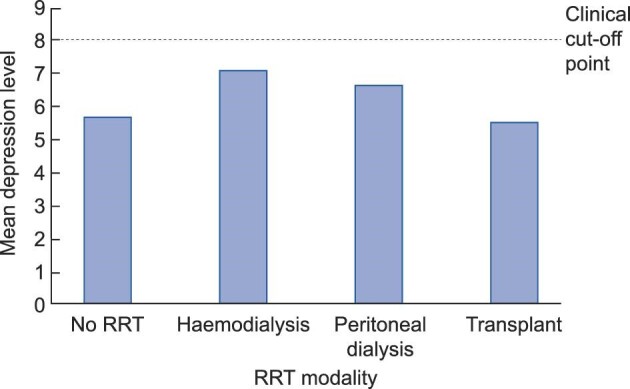

A one-way ANOVA indicated that there was a significant association between depression and RRT modality, although the effect size was small [F(3264) = 3.2, P = .048, η2 = 0.027]. See Figure 2 for mean depression level by RRT modality. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey honestly significant difference test indicated that the mean score for levels of depression were significantly higher for those on HD [mean 7.12 (SD 4.57)] compared with those with a functioning transplant [mean 5.54 (SD 4.08)] and those not on RRT [mean 5.66 (SD 4.22)], but not between any other treatment modality groups (see Table 4). Higher depression was significantly associated with lower age [r(267) = −0.16, P = .014]. There was no significant difference in the levels of depression between men [mean 5.84 (SD 4.11)] and women [mean 6.68 (SD 4.48); t(267) = −1.6, P = .11, d = −0.2].

Figure 2:

Mean depression level by RRT modality. HD: haemodialysis; PD: peritoneal dialysis; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Table 4:

Mean scores by group

| Variable | Anxiety (HADS-A), mean (SD) | Depression (HADS-D), mean (SD) | Physical HRQOL (SF-12), mean (SD) | Mental HRQOL (SF-12), mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health history | ||||

| Previous diagnosis | 10.89 (3.75) | 7.9 (4.06) | 44.9 (9.3) | 35.14 (9.7) |

| No diagnosis | 6.83 (4.45) | 5.76 (4.27) | 43.89 (8.9) | 44.91 (11.5) |

| RRT modality | ||||

| None | 8.05 (4.46) | 5.66 (4.22) | 46.41 (8.2) | 41.22 (11.1) |

| HD | 7.45 (4.67) | 7.12 (4.57) | 40.47 (8.9) | 42.23 (11.2) |

| PD | 6.89 (4.51) | 6.67 (4.13) | 42.43 (9.2) | 42.04 (12.7) |

| Transplant | 8.48 (4.68) | 5.54 (4.08) | 47.44 (7.9) | 41.36 (11.3) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 6.33 (4.34) | 5.84 (4.12) | 43.25 (9.2) | 45.27 (11.5) |

| Female | 9.18 (4.46) | 6.68 (4.48) | 44.85 (8.8) | 39.73 (11.3) |

Are previous mental health diagnoses and psychological distress associated with HRQOL for people with CKD in Ireland?

There was no significant difference in physical HRQOL between those with and without a mental health diagnosis [t(267) = 0.79, P = .43, d = 0.12]. Those with a previous mental health diagnosis had significantly lower mental HRQOL scores [mean 35.14 (SD 9.86)] than those without a previous diagnosis [mean 44.91 (SD 11.5); t(267) = −5.97, P < .001, d = −0.88].

Higher depression was significantly associated with lower physical HRQOL [r(267) = −0.15, P = .018]. Anxiety was not significantly associated with physical HRQOL [r(267) = 0.07, P = .23]. Lower mental HRQOL was significantly associated with higher levels of anxiety [r(267) = −0.66, P < .001] and depression [r(267) = −0.38, P < .001].

Exploratory analyses of mode of recruitment

Statistical comparisons were made between participants recruited online and in hospitals. Participants who responded online were significantly younger [mean age 46.83 years (SD 13.62)] compared with those who were recruited through hospitals [mean age 55.78 years (SD 14.1); t(268) = −5.022, P < .001, d = 13.78]. There was also a higher proportion of women who completed the survey online (59.3%) compared with in hospitals (34%) [χ2(1, N = 268) = 16.5, P < .001]. These differences are likely a reflection of the fact that younger people and women more frequently engage with the Irish Kidney Association social media pages. There was no significant difference in frequencies of RRT modalities between hospital and online participants [χ2(3, N = 268) = 0.51, P = .38].

There was no significant difference in the levels of depression between those who participated online and in hospitals [t(268) = −1.85, P = .07]. Those who participated online had higher levels of anxiety [mean 6.04 (SD 3.96)] than hospital participants [mean 8.2 (SD 4.66); t(268) = −3.36, P < .001]. This may be due to the fact that online participants were younger and had a higher proportion of female respondents, which were both associated with higher levels of anxiety. There was no significant difference in the frequency of mental health diagnoses between online and hospital participants [χ2(1, N = 268) = 0.45, P = .48].

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the international literature, rates of psychological distress, mental health diagnoses and suicide attempts in people with CKD in Ireland were high. Levels of anxiety were higher in women and young people, and depression was slightly higher in people on HD. Having a mental health diagnosis and levels of anxiety and depression were all associated with HRQOL. To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing mental health diagnoses in people with CKD using self-report measures. Our findings indicate that the identification of and intervention for mental health difficulties in CKD should be prioritised in clinical care.

Clinically significant levels of anxiety (50.7%) and depression (35.4%) were similar to those observed in international meta-analyses, which have shown a prevalence of 43% for anxiety [1] and 39% for depression [5] when using self-report scale measures. The higher levels of anxiety reported may be partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which 64.9% of participants described as having a negative impact on their mental health.

Almost one in four participants had received a mental health diagnosis in the past, the most common diagnoses being anxiety and depression. As measured by the HADS, levels of moderate to severe anxiety and depression were 29% and 15%, respectively. However, only 14.5% of participants had ever received an anxiety-related diagnosis and 14.9% had ever received a depression diagnosis. This discrepancy suggests that rates of anxiety in the CKD population in Ireland are underestimated. This is a cause for concern, as the presence of anxiety and depression symptoms is associated with a higher risk of premature death in people with CKD [3, 5].

Furthermore, reported rates of suicidal ideation (26.4%) and suicide attempts (9.3%) far exceeded those documented in the general population [28]. Results indicate that regular and consistent screening for psychological distress should be implemented into routine clinical care for people with CKD in Ireland so that evidence-based mental health treatment can be routinely offered to those who need it. Current evidence for the effectiveness of pharmacologic treatment of depression for those with CKD is mixed, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to increase the risk for adverse events [29]. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to be a low-risk and effective intervention for reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as improving QOL in people on HD [30]. It is now considered best practice that renal multidisciplinary teams integrate psychology, social work and psychiatry to ensure people with CKD have the support they need [31].

Those on HD had higher levels of depression than those with a functioning transplant and those not on RRT, although the effect size was small. This replicates previous findings [32] and is likely a reflection of the restrictions associated with HD as well as the negative impact the treatment has on people's physical, cognitive and emotional well-being [33]. Results indicate no significant difference between RRT modality groups in terms of rates of mental health diagnoses and anxiety. With regards to age and gender, findings are similar to those found in the general population [34, 35], where women had higher rates of mental health diagnoses and anxiety and lower age was associated with higher anxiety and depression.

Anxiety, depression and having a previous mental health diagnosis were each associated with lower mental HRQOL. Depression was also associated with lower physical HRQOL, adding to existing evidence demonstrating the link between depression and physical health in people with CKD [5, 21]. Physical HRQOL was not associated with anxiety or having a mental health diagnosis. Previous research suggests that people with mental health difficulties have poorer physical HRQOL [23, 36]. The lack of observed differences in this study may reflect the wide range of mental health diagnoses reported. Further research assessing the impact of a range of mental health diagnoses on physical HRQOL in people with CKD is required.

Limitations

Most of the study participants were White and Irish, and all were fluent in English. As recruitment was conducted in hospitals and through the Irish Kidney Association, people not engaged in these services were not recruited. There is evidence that people with schizophrenia are less likely to access specialist kidney care [37]. Thus it is likely that participants in the present study were not representative of the population as a whole and that people with significant mental health difficulties were underrepresented. It should also be noted that while the HADS is efficient and requires fewer clinical resources for administration, self-report questionnaires may overestimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms in kidney failure populations [32]. Interviews based on specific diagnostic criteria would provide a more accurate estimate of prevalence. We asked participants if they had ever received a diagnosis for a mental health difficulty, so it is likely that a number of people with a diagnosis were not experiencing a mental health difficulty at the time of data collection. Furthermore, as we relied on self-report measures, we were unable to ascertain the rates of deaths by suicide. We also could not accurately determine the stage of CKD of participants who were not on RRT. We requested information regarding CKD stage, but decided to exclude this information, as 35% of participants answered that they did not know and a high proportion of those on dialysis inaccurately reported the stage of their CKD. Further research should examine mental health difficulties in a prospective study to learn more about their trajectory during CKD stages.

CONCLUSION

Rates of psychological distress, mental health difficulties, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in people with CKD in Ireland are high. Levels of depression were slightly higher in those on HD and lower for those not on RRT or with a functioning transplant. Levels of anxiety were highest in women and younger people, and mental health diagnoses were more common in younger people. Levels of anxiety and depression and having a mental health diagnosis were all associated with poorer mental HRQOL, and depression was also associated with poorer physical HRQOL. Our findings highlight the importance of improving clinical recognition of mental health difficulties, implementing routine screening for psychological distress and suicide risk and improving access to effective mental health care for people with CKD. Nephrology teams should be adequately resourced with mental health professionals, including psychologists, social workers and psychiatrists.

Contributor Information

Clodagh Cogley, School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Jessica Bramham, School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Kate Bramham, King's College Hospital NHS Trust, London, UK.

Aoife Smith, Irish Kidney Association, Dublin, Ireland.

John Holian, Nephrology Department, St Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

Aisling O'Riordan, Nephrology Department, St Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

Jia Wei Teh, Nephrology Department, St Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

Peter Conlon, Nephrology Department, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

Siobhan Mac Hale, Nephrology Department, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

Paul D'Alton, School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland; King's College Hospital NHS Trust, London, UK.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the participants who gave their time to participate in this study. We would also like to thank the nursing staff who kindly helped with recruitment.

FUNDING

This research was funded by the Irish Research Council (to C.C.) and the Central Remedial Clinic (to C.C.).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

C.C., P.D., J.B. and K.B. conceived and planned the study. A.S., J.H., A.O., J.W.T., P.C. and S.M.H. facilitated recruitment. C.C. collected the data, performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy of individuals who participated in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang CW, Wee PH, Low LLet al. Prevalence and risk factors for elevated anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2021;69:27–40. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seery C, Buchanan S. The psychosocial needs of patients who have chronic kidney disease without kidney replacement therapy: a thematic synthesis of seven qualitative studies. J Nephrol 2022;35:2251–67. 10.1007/s40620-022-01437-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schouten RW, Haverkamp GL, Loosman WLet al. Anxiety symptoms, mortality, and hospitalization in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;74:158–66. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Loosman WL, Rottier MA, Honig Aet al. Association of depressive and anxiety symptoms with adverse events in Dutch chronic kidney disease patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2015;16:155. 10.1186/s12882-015-0149-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palmer SC, Vecchio M, Craig JCet al. Association between depression and death in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;62:493–505. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Afshar Met al. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA 2010;303:1946–53. 10.1001/jama.2010.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2101–7. 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tavallaii SA, Ebrahimnia M, Shamspour Net al. Effect of depression on health care utilization in patients with end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:411–4. 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith Ret al. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;41:105–10. 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu C-H, Yeh M-K, Weng S-Cet al. Suicide and chronic kidney disease: a case-control study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017;32:1524–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ojo AO, Hanson JA, Wolfe RAet al. Long-term survival in renal transplant recipients with graft function. Kidney Int 2000;57:307–13. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00816.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iwagami M, Mansfield KE, Hayes JFet al. Severe mental illness and chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study in the United Kingdom. Clin Epidemiol 2018;10:421. 10.2147/CLEP.S154841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith DJ, Martin D, McLean Get al. Multimorbidity in bipolar disorder and undertreatment of cardiovascular disease: a cross sectional study. BMC Med 2013;11:263. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garriga C, Robson J, Coupland Cet al. NHS health checks for people with mental ill-health 2013–2017: an observational study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2020;29:e188. 10.1017/S2045796020001006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kimmel PL, Thamer M, Richard CMet al. Psychiatric illness in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Med 1998;105:214–21. 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00245-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimmel PL, Fwu C-W, Abbott KCet al. Psychiatric illness and mortality in hospitalized ESKD dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:1363–71. 10.2215/CJN.14191218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson A, Colombo R, Baer Set al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with schizophrenia and end-stage renal disease. Abstract 66. J Investig Med 2018;2:599. 10.1136/jim-2017-000697.606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abbott KC, Agodoa LY, O'Malley PG. Hospitalized psychoses after renal transplantation in the United States: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:1628–35. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000069268.63375.4A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Revicki DA, Osoba D, Fairclough Det al. Recommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labeling and promotional claims in the United States. Qual Life Res 2000;9:887–900. 10.1023/A:1008996223999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mujais SK, Story K, Brouillette Jet al. Health-related quality of life in CKD patients: correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1293–301. 10.2215/CJN.05541008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soni RK, Weisbord SD, Unruh ML.. Health-related quality of life outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2010;19:153. 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328335f939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. García-Llana H, Remor E, Del Peso Get al. The role of depression, anxiety, stress and adherence to treatment in dialysis patients’ health-related quality of life: a systematic review of the literature. Nefrología 2014;34:637–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prigent A, Auraaen A, Kamendje-Tchokobou Bet al. Health-related quality of life and utility scores in people with mental disorders: a comparison with the non-mentally ill general population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:2804–17. 10.3390/ijerph110302804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snaith R, Zigmond A.. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). In: Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000:547–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loosman W, Siegert C, Korzec Aet al. Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory for use in end-stage renal disease patients. Br J Clin Psychol 2010;49:507–16. 10.1348/014466509X477827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lacson E, Xu J, Lin S-Fet al. A comparison of SF-36 and SF-12 composite scores and subsequent hospitalization and mortality risks in long-term dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:252–60. 10.2215/CJN.07231009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castillejos MC, Huertas P, Martin Pet al. Prevalence of suicidality in the European general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Suicide Res 2021;25:810–28. 10.1080/13811118.2020.1765928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gregg LP, Hedayati SS.. Pharmacologic and psychological interventions for depression treatment in patients with kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2020;29:457. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ng CZ, Tang SC, Chan Met al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavioral therapy for hemodialysis patients with depression. J Psychosom Res 2019;126:109834. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dobson J-A. Psychosocial manifesto: a patient perspective. J Kidney Care 2022;7:198–9. 10.12968/jokc.2022.7.4.198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JCet al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int 2013;84:179–91. 10.1038/ki.2013.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones DJ, Harvey K, Harris JPet al. Understanding the impact of haemodialysis on UK National Health Service patients’ well-being: a qualitative investigation. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:193–204. 10.1111/jocn.13871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jorm AF, Windsor TD, Dear Ket al. Age group differences in psychological distress: the role of psychosocial risk factors that vary with age. Psychol Med 2005;35:1253–63. 10.1017/S0033291705004976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Otten D, Tibubos AN, Schomerus Get al. Similarities and differences of mental health in women and men: a systematic review of findings in three large German cohorts. Front Public Health 2021;9:553071. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.553071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Comer JS, Blanco C, Hasin DSet al. Health-related quality of life across the anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bitan DT, Krieger I, Berkovitch Aet al. Chronic kidney disease in adults with schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2019;58:1–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy of individuals who participated in the study.