Abstract

Green production, which reduces hazardous industrial discharges per unit output, is promoted throughout China. The Environmental Kuznets Curve suggests a negative correlation between hazardous industrial discharge and economic growth due to green innovation. This study expanded the EKC framework by including heterogeneity in evaluating the relationship between hazardous industrial discharges and economic growth to reflect green transformation. Administrative ranking disparity is identified as one of the fundamental driving forces of green production transition in a developing country. Building on an enriched EKC framework, we used a spatial estimation model to exclude spatial effects and obtained accurate estimates of the classified regions. The modified research method was used to examine whether industrial pollution has been reduced in 267 cities and towns in China from 2007 to 2021. Environmental protection performance was examined to estimate whether there is a switch to green manufacturing. As industrial hazards are of different types, the author sought to determine whether there was a decrease in industrial sulphur dioxide emissions, wastewater, solid waste, or dust, even though more industrial hazards were recycled than before. The spatial estimates indicated that (a) the national level of pollution remains positively linked with the total output, and every percentage of output growth increases sulphur dioxide emissions by 444.573 tons; (b) a positive relationship between economic growth and wastewater is altered by environmental protection in cities, while the general decoupling between economic growth and other types of industrial pollution, such as solid waste and industrial dust, was not observed; (c) growth in the southeast was decoupled from sulphur emissions, and its sulphur dioxide production per unit of output increased to 0.021 tons. Sulphur dioxide emissions per unit of economic growth along the southeast coast were 379. 048 tons, which was well below the overall average of 444.573 tons. High-income towns along the southeast coast have achieved clean production breakthroughs, realising a 15% reduction in industrial sulphur dioxide emissions by 2021. Although there were signs of a shift toward clean manufacturing in high administrative ranking cities, most regions of China are transitioning to environmentally friendly manufacturing and suffer from the hardships of green production transformation.

Keywords: green-production transition, SO2, industrial wastewater, industrial dust, industrial waste recycled, administrative ranking, and spatial regression

Introduction

Reducing industrial hazards through green production transitions is essential for the sustainability of a developing country. 1 This study aims to determine whether China has undergone a green transformation by reducing and treating sulphur dioxide emissions, industrial wastewater, industrial dust, and hazardous solids. Since the altered positive relationship between economic growth and industrial hazards reflects a green production transition, it could indicate whether the economy is undergoing a green transformation. 2 The link between economic growth and pollution continuously varies with modernisation, which is caused by disparities in green production transitions.

High levels of industrial pollution are inevitable in most developing countries owing to the lack of green technology. This can only be avoided or mitigated by green manufacturing or breakthrough innovations. 3 The characteristic of decreasing industrial hazard releases with rising productivity is known as the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC). 4 The EKC suggests that a positive correlation between hazardous industrial releases and economic growth will change as a result of ‘treating before discharging’ or ‘green innovation.’

It is also worth noting that unless there is a significant breakthrough in green technology, the desirable negative relationship between economic growth and hazardous discharge per unit output will soon reverse. According to the EKC theory, it is challenging for a developing economy to maintain moderate pollution levels without green technology breakthroughs because hazard discharges usually increase rapidly when production increases. Therefore, the EKC in developing countries usually appears as an N-shape rather than a stable inverted U-shape. 4

Most studies have tested the Kuznets Curve at the country level,5–8 thereby overlooking regional heterogeneity in natural endowments, political superiority, and administrative rankings, which are especially prevalent in low-income nations. This study addresses this research gap by considering administrative ranking to estimate whether there is a de-link between industrial hazards and economic growth in 267 selected cities and towns of China from 2007 to 2021. The aim is to assess the varying pace of green transformation across the country.

Green transformation is pivotal to a sustainable economy. China must meet the consumption needs of the world's most populous country while maintaining moderate levels of hazardous discharge. It has been growing rapidly among most developing countries since the 1990s, and its annual economic growth rate has been around 9%–12% over the past 30 years due to globalisation. However, the environment has deteriorated because of the rapid expansion of manufacturing. Counties and towns are constantly trying to impose high pollution standards on manufacturers in response to the rapid environmental deterioration and severe water pollution. China has realised the fallacy of short-term economic gains at long-term environmental expenses; therefore, it has put more effort into controlling industrial pollution. Currently, it no longer pursues rapid growth; instead, it avoids environmental costs and balances high-quality income for long-term well-being.

Given budget constraints and regional income inequalities, the application of clean production and environmental protection varies across countries. Despite the law enforcement of environmental protection being unified in the country, its implementation varies greatly. Due to disparities in the implementation of environmental protection, the level of industrial pollution differs across regions. In other words, the application of clean production and environmental preservation differs nationwide because of financial restrictions and regional income disparities. The actual execution of environmental protection in the enormous country of China has varied widely, even though the law is uniform. The degree of industrial pollution varies among regions because of the differences in the implementation of environmental protection.

This study considers regional disparities in the real world, such as political superiority, natural endowments, and economic development, to examine the relationships between economic growth and hazardous industrial discharge across the country and to compare discharge reductions in various hazard classifications to reflect the advancement of manufacturing in regions. As the EKC is inverted only when green transformation occurs, 1 this empirical study seeks an inverted U-shaped EKC to reflect the possible conversion to green transformation and clean energy use in cities and towns across China.

The author aims to demonstrate how regional disparities affect industrial hazard discharges across the country by incorporating regional heterogeneity into the EKC framework to monitor the pace of green transformation. Regional heterogeneity, categorised as ‘administrative standing’, emerges in an empirical EKC study for the first time, providing guidelines for tailored regional environmental protection.

The research questions are as follows.

RQ1. Have cities and towns applied clean production? Where has hazardous industrial discharge of unit output been reduced the most?

RQ2. Has the positive U-shaped relationship between hazardous industrial discharge of unit output and economic growth altered in cities with high administrative rankings in China?

RQ3. Which type of industrial hazard has been reduced the most through green innovation?

To identify the research gap in the EKC, this study reviews recent studies that test the Kuznets Curve hypothesis at the country level, which will indicate a need for more attention to regional disparities in developing countries.2,9 As the focus is to find an additional driving force of the EKC, the latest environmental solutions, such as the monitoring system in material flows and the waste recycling system,10,11 are not included in the scope of this research.

Sequentially, to factor in regional heterogeneity, the section on regional disparities explains how industrialization varies in China and identifies administrative ranking as a significant factor in green transformation. Hence, it is essential to consider China's income disparities and city administrative classifications when estimating EKC. Building on an enriched EKC framework, this section of the empirical study applied the spatial estimation method to exclude spatial effects and obtain accurate estimates of classified regions. Finally, discussing other factors affecting the average industrial hazardous discharge will help to identify research limitations and other investigation methods.

Literature review and theoretical background

Environmental protection has become more critical as per capita income increases, as people demand clean water, clean air, organic food, etc.12,13 The EKC hypothesis, which refers to expanding outputs while keeping industrial discharge at a minimum level through clean production, has been well tested in developed countries since the 1970s. 14 Most studies in developed countries have found a stable negative relationship between industrial pollution and income, reflecting the use of green technology to preserve the natural environment with economic growth.15,16

The aim of the EKC is to explore plausible drivers of the relationship between pollution and economic growth to create a win-win situation in which the environment could be largely protected by clean production. Many studies have found that the environment could be largely protected by green manufacturing in the post-industrial era.13,17,18 Research on atmospheric pollution in Spain was carried out using the EKC framework, which confirmed that atmospheric pollution was not only caused by production expansions but also through industrial sulphur emissions from heavy industries. 8 Castiglione et al. (2015) observed the relationships among long-term pollution levels, institutional enforcement, and local economic growth to identify appropriate policies for sustainable development. 19 They adopted a Panel Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model to identify interactions between pollution level, institutional enforcement, and economic growth by analysing data collected from 33 developed countries between 1996 and 2010. Their study not only found negative relationships between pollution and economic growth in developed countries (which supports the EKC hypothesis) but also explored the reason for less industrial pollution in developed countries compared to developing countries. Two driving factors of industrial pollution reduction have been identified in the literature: (a) transition to clean production, and (b) relocation of pollutant-intensive industries abroad. Recently, scholars aimed to classify the drivers of income-pollution relations to monitor the green economy transformation process based on the EKC framework.20–22 When moderate industrial hazardous discharge with output expansions was found in high-tech industries in developed countries, the distinctive inverted EKC could be ascribed to innovations, policy-induced green-technology shifts, and intra-sectoral restructuring. 23 In contrast, if there was a lack of green innovation, economic growth would have slowed down, putting both the economy and the environment in a degradation scenario. 24 In general, the above findings support the EKC framework by exploring the various driving forces of income-pollution relationships in developed countries.

However, some scholars argued that the EKC hypothesis has not always been robust since the top priority of society varies across time and place. 25 Roca et al.(2001) argued that an income-pollution relationship could be determined by many factors, and it seems to vary all the time. 8 The latest research in this field has focused on what drives the income-pollution relationship to vary, which would complement the standing ground of the EKC hypothesis. 26 Alonso-Carrera et al. (2019) pioneered the theory of dynamic pollution in economic growth models with non-homothetic preferences. 14 They argued that environmental protection would decline when economic growth becomes a priority. 27 In other words, the EKC hypothesis would not hold when environmental protection loses its privilege in an economy. 28

The existing literature proves that the determinants of income-pollution relationships are affected by the weighting of priority. Developed countries prioritise environmental protection and natural resource reservations with the help of technological breakthroughs that compensate for the short-term profit loss from going green. It is possible that wealth in developed countries always supports eco-friendly development, which internalises environmental quality in their endogenous growth model. 6 To testify to this logic, Cole (2000) attempted to prove that intellectualised industries would enable manufacturers to apply clean production with industrial modernisation. 29 Similarly, Nigatu (2015) found that emissions from industrial hazardous PM10 have fallen in middle-income countries but have risen in low-income countries. 5 Obviously, there would be an inverted U-shape of pollution and economic growth in modernisation, whereas countries and economic zones that have a strong intention to maintain a high output might leave environmental protection behind. The above studies concluded that income-pollution relationships could be vague in countries that prioritise production expansion; hence, the EKC hypothesis does not always hold.27,30

Referring to Asian studies, Uddin et al. (2019) evaluated the environmental conditions of 13 Asian countries over a 50-year period from 1970 to 2019. 31 Based on the EKC framework; they tested the linear, quadratic, and cubic functions of industrial pollution as independent variables in economic growth regression estimations. The estimated results were not optimistic for most Asian countries, because the increase in the economic growth rate came at the expense of natural resources and the environment. Asian countries must improve their green manufacturing capabilities to maintain sustainable development.31–35

In general, Asian environmental studies have focused on time-series analysis at the country level to provide macro guidance for a sustainable economy, whereas studies on the pollution-income debate still need to be well explored across regions and industries.7,36,37

Inspired by the existing literature, this study considers overlooked regional characteristics, such as administrative ranking, in examining the EKC, 37 which can provide practical guidance for green transformation in regions to enrich Asian EKC studies. In short, the EKC framework will be expanded by factoring heterogeneity in evaluating the relationship between hazardous industrial discharges and economic growth to reflect the area's progress in green transformation.

Regional disparities in China

Regional economic development disparity

Although China is a large economy, its habitable land area is relatively small, and terrain differences lead to disparities in economic development. Terrain differences, such as glaciers in northern China and deserts, loess plateaus, mountains, and prairies in the west, which are uninhabitable areas, generate less than one billion US dollars (6.6 billion RMB) per year (National Bureau of Statistics of China). Developed cities and towns with GDPs over 160 billion US dollars (one trillion RMB) lie on the southeast coastline and provincial centres, whereas most inland towns produce less than 45 billion US dollars (300 billion RMB), where they are struggling to achieve green transformation (National Bureau of Statistics of China).

China's industrialisation has progressed rapidly since the 1970s and has further accelerated after joining the World Trade Organization (WTO). With rapid industrialisation, pollution has deteriorated, and natural resources are rapidly depleting. In other words, natural resources such as coal, water, mines, and forests have been overexploited to support rapid industrialisation.

Economic development disparities are becoming significant in China, along with environmental deterioration. The most developed industrial zones are located along the southeast coast and in high-ranking cities. Industrialisation was rarely seen in small towns, which widened income disparities between cities and towns, north and south, and coastline and inland areas. Cities and towns along the southeast coast have benefitted more from the Global-Value-Chain (GVC) and international trade than inland since China joined the WTO in 2002. 38 Meanwhile, cities with high administrative rankings, such as national municipalities and provincial municipalities, have the privilege of accessing national funds and support, which enables them to grow faster and invest more in environmental protection than other places. Although the central administration has intended to balance wealth distribution by locating cities with high administrative rankings evenly across the vast land, the disparity in development has widened between the southeast coastline and inland China due to the unequal speed of industrialisation. It is obvious that wealth disparity causes environmental protection and green manufacturing applications to vary across countries.

High-tech industries are generally located in the southeast, whereas most low-tech manufacturers are located inland. The southeast coast has four provinces, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong, in which the main harbours of China are located and are highly open to the world. With its high openness, Southeast China has always been a pioneer among other regions in embracing modern technology and actively participating in globalisation. South-eastern cities and towns share an economic development bonus and technology spillover, making cities and towns of the four provinces enjoy a GDP above 160 billion dollars higher than that of inland cities since 2014.

However, the inland region has performed much worse in terms of economic development because it is less involved in global trade, lacks political reform, and receives fewer national subsidies. 1 Most inland cities and towns are not trading as actively as the rest of the world as the southeast, but provide sanctuaries for high energy-consuming and pollution-intensive factories, which makes the inland severely polluted. Without high-tech spillovers and abundant foreign investment, small inland towns still engage in low-tech industries such as textiles, wooden products, printing, and metal manufacturing, thereby losing the opportunity for industrial modernisation.

As southeast cities trade with the world much more activity along the coast, state-of-the-art technology applications enable the four provinces to upgrade their labour-intensive industries to high-tech industries, such as intelligent appliances, fibres, and biochemistry. The southeastern Economic Zone has contributed more than 40% of the national GDP every year since 2012. It is plausible that regional disparities between the inland and southeast regions will widen in the post-industrial era.

Regional disparity in industrial pollution

Previous studies have certified the view that industrial sulphur dioxide emissions are mainly produced by heavy industries 8 ; hence, the study showed geographical industrial sulphur dioxide emissions to reflect the distribution of heavy industries in China.

Figure 1 shows that most of the sulphur emissions were from inland towns that are striving for industrial modernisation. The study finds evidence of a clean production transition, as developed cities and towns with an annual GDP above 160 billion US dollars (one trillion RMB) on the southeast coast and provincial centres produce more but discharge fewer industrial hazards.

Figure 1.

Average annual industrial sulphur dioxide emissions (tons) in 2007–2021. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/. The map was made using ArcGIS. Note: The light-colored regions in the map represent the glaciers in northern China and deserts, plateaus, mountains, and prairies in the west, which are under-industrialized areas and produce negligible industrial hazards annually.

At the beginning of the industrialisation period (i.e. 1980–2010), heavy-polluting industries such as metallurgy, chemistry, and textile manufacturing contributed more than 70% of local GDP to sustain income growth and stabilise social development; as such, they could not be shut down, or they would be penalised heavily. However, what is behind numerous industrial start-ups, massive construction, and production are serious environmental pollutants that produce tons of sulphur dioxide emissions. Heavy pollution, contaminated water, and scarcity of natural resources threaten society's sustainability. If there was no green manufacturing to reduce hazardous industrial discharge, the modernisation of industries would not take place, and the economy would be trapped in a pollute or produce a dilemma. Therefore, reducing hazardous discharge through green manufacturing transformation has become a top priority in China.

The different pace of economic development has led to actual environmental protection varying across countries. Both inverted U-shapes- and U-shaped relationships between economic growth and industrial pollution have been found in different regions of China. Although economic development and innovation should benefit the environment in the long run, manufacturers seem unwilling to invest more in green transformations. Owing to the lack of eco-friendly infrastructure and innovation, an inverted U-shaped curve between economic growth and industrial pollution has rarely been observed in small towns and rural areas in China. In this case, the regional disparity in either hazardous discharge per unit output or income per capita is further exacerbated if there are no significant remedies.

Other factors such as disparities in income per capita, foreign investment, and business integrity also drive the growth of pollution relationship. Although China has set only one emission standard for all cities and towns to comply with, the implementation of emission standards still differs regionally. Thus, an analysis of the relationship between economic growth and industrial pollution based on provincial data may overlook the regional disparities.

To account for these regional disparities, this study investigates the relationships between industrial pollution and economic growth in different locations to reflect regional heterogeneity in environmental protection. Specifically, the author empirically analyses whether hazardous industrial discharge, such as industrial effluents, sulphur emissions, and solid waste, was mainly caused by increases in industrial output, discusses plausible law enforcement and subsidies that enable local administration to balance the goals of both environmental protection and economic development and explores the implications of this research.

Methodology

Regional statistics

The National Bureau of Statistics of China collects data on hazardous industrial discharge, air pollution, economic growth, total number of employees, investments, industrial outputs, etc., collected from cities and towns to monitor social welfare and economic development. This study examined the existence of the EKC in 267 cities and towns in China from 2007 to 2021 using economic and environmental monitoring data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

As regional disparities are caused by both endowments and administrative rankings, cities and towns have been classified geographically into groups of southeast, midland, north, inland, and coastline; they were also classified into groups of provincial capital, small- and medium-sized cities, and towns by administrative ranking. Regional annual data on gross domestic product (GDP), population, foreign investment, total number of employees, waste recycling, hazardous industrial discharge, dust treatment, sulphur dioxide emissions, and all other economic statistics were collected to examine the progress in industrialisation and environmental protection in different regions.

Data analysis

As the goal of this study was to test the relationships between economic growth and the level of hazardous industrial discharge in different regions of China, the indicators focused on regional real GDP, industrial output, waste recycling, dust treatment, wastewater treatment, and hazardous industrial discharge, including sulphur emissions, wastewater discharge, and solid wastes. Other statistics, such as population density, non-agricultural population, foreign investment, total number of employees, fixed assets, and outputs of industries, were counted as control factors in this empirical study.

Table 1.

Summary statistics and description of variables.

| Variables | Unit | Mean | S. D | Min | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial sulphur dioxide | Tons | 58873.92 | 59504.91 | 2 | 711,537.40 | 4155 |

| Industrial dust | Tons | 33,070.15 | 115,341 | 34 | 5,168,812 | 4138 |

| Industrial wastewater | Tons | 7596.01 | 9689.58 | 7 | 91,260 | 3860 |

| Industrial waste treated | Tons | 7442.29 | 9728.92 | 7 | 91,260 | 3692 |

| Industrial waste Recycled | % | 52.99 | 27.5 | 0 | 100 | 2052 |

| Industrial solid recycled | Tons | 78.04 | 23.49 | 0.49 | 143.24 | 3503 |

| Industrial SO2 treated | Tons | 75,667.46 | 510,000 | 0 | 18,020 | 2214 |

| Eco-investment | Million RMB | 713.80 | 2100 | 0 | 37,000 | 1370 |

| Eco-infrastructure | Million RMB | 988.45 | 1900 | 0 | 23,000 | 1369 |

| Industrial output | Million RMB | 190,000 | 340,000 | 0.53 | 3,200,000 | 4273 |

| GDP | Billion RMB | 145.64 | 227.54 | 2.40 | 2817.86 | 4277 |

| GDP growth rate | % | 15.14 | 9.25 | 10 | 55 | 4289 |

| Population | Million | 427.38 | 302.67 | 0 | 3392 | 4287 |

| Non-agriculture pop | Million | 129.88 | 126.61 | 12.53 | 1216.56 | 2219 |

| Population growth | % | 5.78 | 4.6 | −8.9 | 40.78 | 4265 |

| Pop density | Million/Km2 | 423.18 | 371.69 | 4.7 | 11,564 | 3986 |

| Total employees | Million | 45.88 | 68.45 | 4.05 | 986.87 | 4279 |

| Aggregated salary | Million RMB | 15,000 | 41,000 | 1.14 | 900,000 | 4270 |

| Foreign investment | Million US$ | 584.72 | 15,000 | 0 | 31,000 | 4068 |

| Share of 1st industry | % | 15.34 | 9.5 | 0.03 | 50.38 | 4277 |

| Share of 3rd industry | % | 36.87 | 8.64 | 8.58 | 85.34 | 4276 |

| Fix asset housing | Million RMB | 10,000 | 21,000 | 0 | 250,000 | 4258 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Overall, the statistics showed significant disparities in regional development across various aspects such as environmental investments, population density, economic growth, wastewater discharge, industrial sulphur treatment, and waste recycling. Economic growth varies as much as environmental protection does across countries. Some western regions remain pristine, whereas cities along the southeast coast have undergone rapid development and invested intensively in environmental protection.

Since descriptive statistics show a large discrepancy in regional development, this empirical study expects to speculate on green production transition by examining industrial pollution reduction in cities and towns.

Industrial hazardous discharge and treated

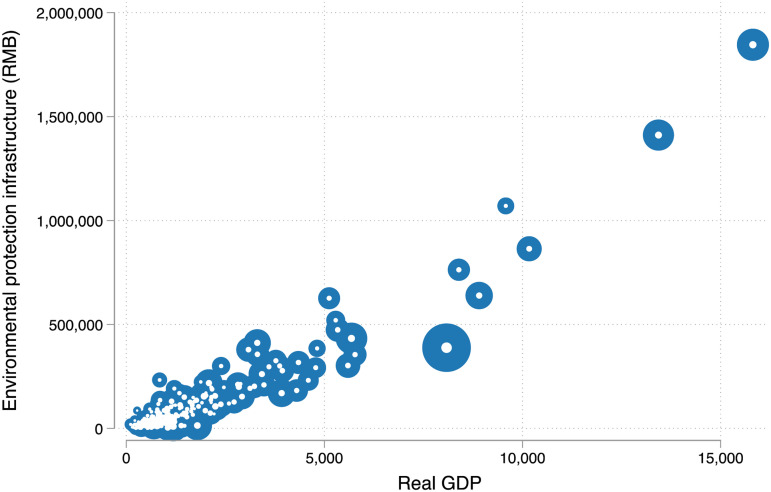

Statistics for various hazardous industrial discharges and treatments in China from 2007 to 2021 are shown in Figures 2–8. A generally positive relationship between hazardous industrial discharge and real GDP was found in less-developed towns in China, but all types of industrial hazards were treated and recycled in an increasing trend or at high levels.

Figure 2.

Industrial sulphur dioxide (tons). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Figure 8.

Industrial dust discharges (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Despite the increasing treatment of sulphur dioxide (Figure 9, Appendix), low-income towns have discharged more industrial sulphur dioxide per GDP growth since 2007 than high-income cities (see Figure 2).

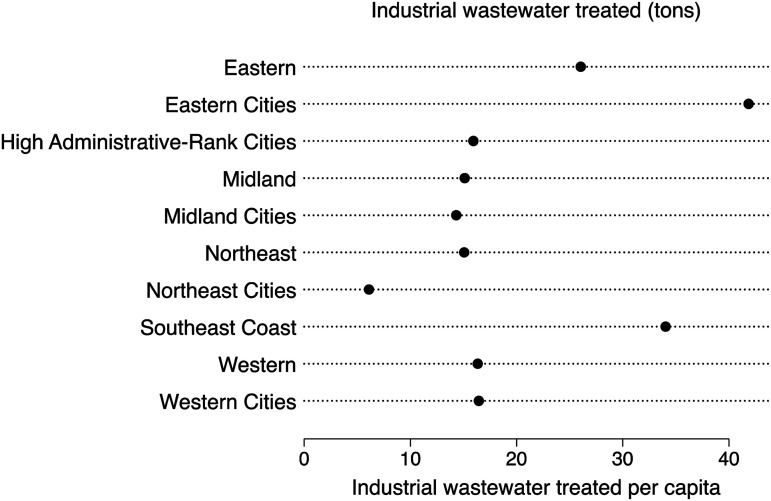

Another promising piece of evidence is shown in Figure 3, where industrial wastewater showed an inverted U-shape with real GDP in large cities with high GDP. Figure 10 in the Appendix shows that recycled industrial wastewater is stabilised at 80 tons in most cities and towns (source: National Bureau of Statistics of China).

Figure 3.

Industrial wastewater discharged. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Most cities and towns produce less than 250,000 tons of industrial dust annually. Figure 12 in the Appendix shows that major cities treat up to 8 million tons of industrial dust annually, with increasing GDP. Meanwhile, the volume of recycled and treated industrial solid waste increased sharply with GPD since 2007, reaching 100 tons per year in cities (see Appendix, Figure 13).

The increase in recycling and treatment can be attributed to the growing environmental investment. Figure 4 shows that the country's environmental infrastructure and economic growth have rapidly developed. Increasing environmental protection through infrastructure has led to an inverted Kuznets curve (KC). According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the average regional environmental infrastructure capital exceeded 1.2 million US dollars (8.4 million RMB) in 2021.

Figure 4.

Environmental infrastructure investment in RMB from 2007 to 2021. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

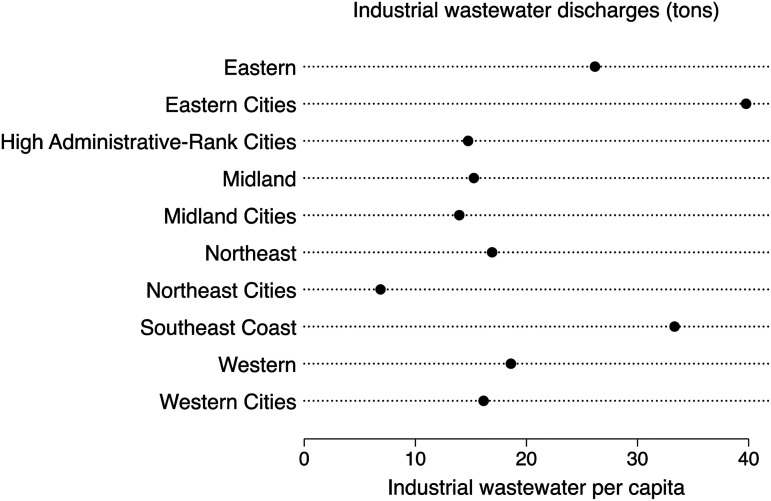

Industrial hazards discharge in classified regions

Cities and towns were classified into groups based on wealth disparity and administrative rankings to reflect the privileges of the green production transition. After classification, each group shows a relatively clear correlation between industrial hazard discharge and economic growth. By contrast, the diversified relationships between industrial hazard discharge and economic growth shown in Figure 5 reflect disparities in development and wealth across regions caused by administrative rankings.

Figure 5.

Diversified relationships between industrial SO2 emissions and economic growth in classified groups. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

The group of high administrative rank cities (symbolised by ◊) showed an inverse relationship between sulphur dioxide and GDP (Figure 5), indicating good implementation of industrial hazard control. Especially in Eastern and Midland cities (symbolised by ▪ and ▴, respectively), economic growth is accompanied by decreasing sulphur dioxide emissions. In contrast, the Northeast, Western, and Midland groups (symbolised by •) in Figure 5 show a positive relationship between sulphur dioxide and GDP, indicating a failure to convert to clean production.

While the southeast is the most polluted area in China due to industrialisation and the relocation of many high-energy-consuming factories from developed countries, the four provinces have implemented environmental protection measures to turn them into green spaces. Since southeastern manufacturers utilise clean manufacturing techniques today, they have dissociated industrial hazards from economic growth in the region.

Western towns engaged in low-tech manufacturing have not yet met environmental protection standards, making them discharge the highest volume of industrial sulphur dioxide and dust in China (Figures 7 and 8). In contrast, cities with high administrative rankings discharged less industrial sulphur dioxide (Figure 6), wastewater (Figure 7), and dust (Figure 8) than towns. Fast-rising land prices in major cities of China mean that only manufacturers and industries that produce high-profit margins have the privilege of being located in cities. High-tech industries earning profit premiums from intelligent manufacturing can afford high land prices on the coast, facilitating their participation in world trade and embracing cutting-edge technologies. However, low-tech industries, which demand intensive resources and generate significant pollution, are prohibited from being located in major cities or developed zones, preventing them from modernising. Thus, income disparity exacerbates environmental protection inequality in major and less-developed towns.

Figure 7.

Industrial wastewater (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Figure 6.

Industrial SO2 emissions (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Overall, cities with a higher administrative rank discharge less industrial sulfur dioxide and wastewater and treat more industrial hazards with environmental protection infrastructure than towns do. Statistics on industrial hazards discharged, treated, and recycled by regional groups are presented in Figures 2–8 and 9–16 in the Appendix.

Estimations of industrial-pollution per unit GPD

To examine the relationship between industrial hazards and economic growth, spatial econometric tests were conducted using panel data from 267 Chinese cities and towns. The bureaucratic factor has been included in an analytical framework to examine the relationship between industrial hazard discharge, economic growth, and environmental protection since administrative privilege grants access to the Green Transformation Fund (National Carbon Neutrality, National Development and Reform Commission). Therefore, this study used an EKC-based spatial estimation model to estimate the bureaucratic factor which influences hazardous industrial discharge per unit output.

Second, the expanded EKC framework with regional heterogeneity can be accurately examined using a spatial estimation model. Most related research used the panel data regression method without spatial factors, while this study accurately estimated industrial hazards with per-unit economic growth in classified groups by excluding the spatial effects of neighbours.6,31,39 Since regional spillover effects of economic growth could be exhibited by the spatial-effect estimations, spatial factors that affected individual towns were identified; in other words, speculation was made on how seriously a town could be polluted by its neighbours.40–43 In other words, based on EKC hypothesis, 4 economic growth was set as the independent variable that drove the level of hazardous industrial discharge to vary over time. In the post-industrial era, hazardous industrial discharge per unit output should be decreased by industrial modernisation and clean production. 2 This phenomenon can be inferred using a spatial model to reflect the existence of the EKC.

| (1) |

| (2) |

It is worth noting that GDP per capita cannot be a general indicator of economic development because of regional disparities. GDP per capita can be seen as an indicator of economic growth only when there is equality in wealth distribution. Because the Gini Index is extremely high in China, this study considered wealth distribution inequality, where regional economic growth was seen as an indicator of economic development instead of GDP per capita. In Equation (1), and reflect nonlinear correlations between economic growth and hazardous industrial discharge.

In Equation (1), represents hazardous industrial discharges of unit output, the quantity of is supposed to be at a moderate level when there is effective environmental protection or clean production, i and t represent individual regions and years, respectively.

Equation (2) was built on Equation (1) to exclude the spatial effects of neighbour industrial pollution and economic growth for an accurate estimate. The burden caused by neighbours rather than local production could be estimated by weighting the influence based on the geographic proximity of individual cities and towns. 44 The spatial effects of industrial pollution and economic growth were excluded from Equation (2) for a more accurate estimate. Weighting the influence based on the geographical proximity of individual cities and towns could estimate the burden caused by neighbours rather than local production.

The independent variables and represent the spatial spillover effects of industrial pollution and economic growth from surrounding neighbours; hence, the unobservable influential factors on industrial discharge would be segregated from the black box of estimation error.41,42,45,46

The spatial weight matrix was built by letting , where is the element of , and represents the geographical distance between the two cities i and j in kilometres.47,48 To improve the accuracy and consistency of the results, this study used spatial estimation methods of SLM, SAR, and SDM estimation postulated by Anseline (1996). 49 The SDM50,51 was adopted due to the maximum likelihood of gauging the spatial effect in EKC. Equations (3), (4), (5), and (6) are expansions of Equations (1) and (2) to test the correlation between sulphur dioxide emissions, wastewater, dust, solid waste, and economic growth.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

According to Equation (3), both local and nearby economic growth and industrial sulphur dioxide emissions contribute to the indigenous total sulphur dioxide emissions. Likewise, to accurately estimate industrial wastewater, dust, and solid waste generated per unit output, Equations (4), (5), and (6) capture the spatial effect of economic growth and pollutants for accurate estimates.

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Finally, panel regressions tested whether all types of industrial hazards are treated and recycled incrementally with an increasing output , and represents control variables such as fixed assets, population density, and foreign investment, absorbs the heterogeneity of individual regions. Using Equations (7), (8), (9), and (10), we can test the amount of sulphur dioxide treated before discharge in cities with high GDP, the amount of industrial dust treated per unit output, if industrial wastewater is increasingly treated with industrialisation, and the amount of solid waste recycled. The empirical estimates of Equations (3), (7), and (8) can be found in Tables 2, 3, and 4 in the Results section. The estimates of Equations (8), (9), and (10) are presented in Tables 5, 6, and 7, respectively.

Table 2.

Estimated industrial sulphur dioxide emission with per unit economic growth in administrative groups.

| Sulphur dioxide | All | Inland Cities | Inland Towns | South-east | South-east Cities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth | 444.573*** | 430.709*** | 537.746*** | 379.048*** | 281.912 |

| (8.95) | (9.23) | (5.86) | (3.31) | (1.21) | |

| Foreign Investment | −0.035*** | −0.023 | −0.025 | −0.006 | −0.005 |

| (−5.44) | (−1.54) | (−1.61) | (−0.28) | (−0.35) | |

| Population Growth | 152.912 | 195.045 | 189.77 | 518.975* | 524.510* |

| (1.15) | (1.56) | (1.52) | (1.93) | (1.95) | |

| Industrial output | −0.000** | −0.000* | −0.000** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (−2.53) | (−1.96) | (−1.98) | (−0.70) | (−0.69) | |

| Fix asset housing | −0.004*** | −0.004*** | −0.004*** | −0.006*** | −0.006*** |

| (−8.65) | (−4.46) | (−4.42) | (−7.47) | (−7.47) | |

| GDP growth2 | −3.535 | 2.982 | |||

| (−1.35) | (0.48) | ||||

| Cons | 6.1 × 104 *** | 5.1 × 104 *** | 5.1 × 104 *** | 5.6 × 104 *** | 5.7 × 104 *** |

| (49.26) | (42.58) | (40.64) | (18.84) | (17.87) | |

| N | 3467 | 3081 | 3081 | 684 | 684 |

| r2_adj | 0.113 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.211 | 0.21 |

| F | 146.974 | 53.82 | 45.169 | 48.066 | 40.044 |

***, **, *indicate significance at 0.01,0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Table 3.

Spatial estimations of industrial sulphur dioxide emission per unit economic growth.

| Sulphur dioxide | SDM | SAR | SDM | SAR | SDM | SAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial-effect | Direct | Direct | Indirect | Indirect | Total | Total |

| GDP growth | 120.452* | 284.908*** | 940.853*** | 151.280*** | 1061.305*** | 436.188*** |

| (2.36) | (6.31) | (7.11) | (5.71) | −8.56 | −6.57 | |

| Foreign investment | −0.037*** | −0.038*** | 0.006 | −0.020*** | −0.032 | −0.059*** |

| (−7.73) | (−7.80) | (0.2) | (−5.38) | (−1.12) | (−7.27) | |

| Pop growth | 284.439* | 271.365* | −1.6 × 103*** | 145.310* | −1.3 × 103** | 416.674* |

| (2.29) | (2.16) | (−3.34) | (2.06) | (−2.71) | −2.14 | |

| Fix asset housing | −0.004*** | −0.004*** | 0.001 | −0.002*** | −0.003 | −0.006*** |

| (−10.39) | (−10.54) | (1.04) | (−6.43) | (−1.89) | (−9.90) | |

| Spatial | ||||||

| 0.305*** | 0.359*** | Likelihood-ratio test: LR = 73.41 | ||||

| (9.67) | (13.32) | (Assumption: SAR nested in SDM) Prob > chi2 = 0.000 | ||||

| σ2 | 5.2 × 108*** | 5.3 × 108*** | ||||

| (43.9) | (43.88) | |||||

| N | 3878 | 3878 | 3878 | 3878 | 3878 | 3878 |

***, **, *indicate significance at 0.01,0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Table 4.

Estimations of sulphur dioxide treated for unit output.

| Sulphur dioxide Treated | All | Inland Cities | Inland Towns | South-east |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total output | 0.005*** | 0.002*** | 0.007 | 0.021*** |

| (3.12) | (7.27) | (0.93) | (3.50) | |

| Fix asset housing | −0.038 | 0.021*** | −0.043 | −0.513*** |

| (−1.26) | (2.88) | (−0.41) | (−2.74) | |

| GDP growth | 194.474 | −161.126 | 3434.233 | 7846.040 |

| (0.06) | (−0.51) | (0.07) | (0.49) | |

| GDP Growth2 | −20.453 | −10.03 | −138.102 | −230.797 |

| (−0.26) | (−1.23) | (−0.13) | (−0.56) | |

| Foreign investment | −0.602* | 0.102 | −0.861 | −4.289** |

| (−1.69) | (1.35) | (−0.64) | (−2.29) | |

| Population growth | −1.60 × 103 | 740.463* | −4.90 × 104 | −2.5 × 104 |

| (−0.39) | (1.73) | (−0.86) | (−0.99) | |

| Cons | 7.5 × 104 * | 2.6 × 104 *** | 4.9 × 105 | 5.4 × 105 ** |

| (1.82) | (5.92) | (0.86) | (2.23) | |

| N | 2108 | 1882 | 226 | 483 |

| r2_adj | 0.153 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.108 |

| F | 1.842 | 74.207 | 0.277 | 2.99 |

***, **, *indicate significance at 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Table 5.

Industrial dust treated per unit economic growth.

| Treated Dust | All | Inland Cities | Inland Towns | South-east |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth | 0.006** | 0.015* | 0.005* | 0.011 |

| (2.02) | (1.72) | (1.68) | (1.31) | |

| Foreign investment | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (−0.05) | −0.45 | (−0.45) | (−0.82) | |

| Population growth | −0.006 | 0.002 | −0.006 | −0.036* |

| (−0.90) | (0.1) | (−0.92) | (−1.84) | |

| Total output | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.66) | (1.04) | (−0.04) | (0.31) | |

| Fix asset housing | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| −0.07 | (−0.98) | −0.81 | (0.72) | |

| Cons | 0.113* | −0.245 | 0.148** | 0.274 |

| (1.65) | (−1.16) | (2.01) | (1.29) | |

| N | 2600 | 278 | 2322 | 517 |

| r2_adj | 0.122 | 0.125 | 0.122 | 0.103 |

| F | 1.06 | 0.855 | 0.911 | 1.102 |

***, **, * indicate significance at 0.01,0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Table 6.

Industrial wastewater treated per unit output.

| Wastewater treated | All | Cities | Towns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output | 0.000*** | 0.00 | 0.000*** |

| (7.26) | (0.72) | (4.77) | |

| GDP growth2 | −1.22 | −31.57 | 0.568 |

| (−0.13) | (−0.69) | (0.06) | |

| Foreign investment | −0.021*** | −0.013*** | −0.024*** |

| (−9.34) | (−3.88) | (−5.26) | |

| Pop growth | 50.994* | −20.814 | 54.557** |

| (1.96) | (−0.15) | (2.13) | |

| Fix asset housing | −0.000** | −0.001** | 0.001 |

| (−2.54) | (−2.12) | (1.21) | |

| Cons | 7556.651*** | 2.1e + 04*** | 5766.299*** |

| (31.71) | (18.04) | (23.92) | |

| N | 2160 | 239 | 1921 |

| r2_adj | 0.081 | 0.093 | 0.095 |

| F | 25.824 | 11.879 | 18.53 |

t statistics in parentheses,*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 7.

Industrial solid waste recycled per unit economic growth.

| Solid waste recycled | All | Cities | Towns |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth | −0.068** | 0.09 | −0.072** |

| (−2.28) | (1.14) | (−2.24) | |

| Foreign investment | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (−0.51) | (0.04) | (1.29) | |

| Population growth | −0.049 | −0.285 | −0.048 |

| (−0.60) | (−1.30) | (−0.56) | |

| Total output | 0.000** | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (2.45) | (0.97) | (0.6) | |

| Fix asset housing | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000** |

| (0.85) | (1.09) | (2.02) | |

| Cons | 78.706*** | 82.455*** | 77.584*** |

| (104.84) | (41.35) | (93.83) | |

| N | 3435 | 379 | 3056 |

| r2_adj | 0.082 | 0.061 | 0.08 |

| F | 6.735 | 2.625 | 7.377 |

***, **, * indicate significance at 0.01,0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Results

Since the statistics showed that the pollution-income relationship is quite dynamic along a country's development process, this study estimated discharge reductions in various hazardous classifications to reflect the green transformation in different regions of China.

Table 2 summarises the results of clean production progress from the perspective of industrial sulphur dioxide emission. The geographical distribution of sulphur dioxide pollution shows that Hebei, Shandong, Neimenggu, and Liaoning have been severely contaminated over the past 20 years. There were more emissions in the north than in the southeast; hence, the pollution became more severe in the north. Northern inland towns that are far away from harbours and developed areas lose the opportunity to receive high-tech spillovers, thereby continuing to engage in agriculture, crafting, and metallurgy. Although heavy pollution has been stabilised by replacing fossil fuels with natural gas, it is unavoidable for northern inland towns to discharge large quantities of sulphur dioxide every year.

As economic growth does not have a significant impact on industrial sulphur dioxide emissions in developed cities, there is a disassociation between income and pollution, which could be seen as a sign of green manufacturing transformation (Column 6, Table 2). Comparing GDP and sulphur emissions geographically, it is evident that southeast China produced more output in value but discharged less industrial hazard than northern towns. The industrial hazard of unit output has been maintained at moderate levels in the southeast since 2016, implying the use of green technology and a transition to clean production.

Comparing the results in Columns 3 and 5 in Table 2, the estimations show that there were more sulphur dioxide emissions per unit of economic growth inland than in the southeast, while the southeast showed better environmental protection than the inland. This assertion could be proven using another grouping: the average sulphur dioxide emissions per unit output would decrease to 379.048 tons when inland cities and towns were excluded from the sample group. In general, estimations of the regression in Table 2 and Table 3 could be interpreted as inland cities and towns facing more difficulties in clean production transformation than in the southeast In particular, a scale effect of the pollution–income relationship was detected in inland towns as hazardous industrial discharge increased with an increase in total output. The above estimation results align with the rationale of the EKC: primitive manufacturing caused a positive relationship between hazardous industrial discharge and economic growth in inland towns and villages, whereas the technical effect only appears when innovations lead to green transformation.

To evaluate the progress of environmental protection and green technology used across the country, further study on sulphur dioxide treatment was carried out. The estimation results in Table 4 show that more sulphur emissions have been treated in Chinese cities than in towns and that cities have better environmental protection than towns. The treated sulphur dioxide increased significantly at the 1% statistical level by a growing total output during 2012–2021, which predicted that 0.005 tons of sulphur dioxide would be treated for every unit output in most cities and towns of China. Better environmental infrastructure, protection, and sufficient subsidies for green transformation enable cities to treat more sulphur dioxide than towns do.

The estimated results in Tables 2, 3, and 4 reveal that environmental protection has progressed in most cities in China. With a fast-growing economy, an increasing amount of sulphur dioxide has been treated before discharge. In the southeast and major cities, the positive relationship between marginal output and treated sulphur dioxide supports the presumption that well-developed cities and towns along the southeast coast have been transforming into green economies.

Table 5 presents similar cases. More industrial dust is treated before discharge in most places in China, particularly in well-developed cities. The results in Table 5 show that the volume of industrial dust to be treated has significantly increased at the 5% statistical level due to industrial expansion in China. This study predicts that 0.006 tons of industrial dust would be treated per unit GDP growth in most Chinese cities and towns. It is also worth noting that there were large disparities between cities and towns in the volume of treatment, and inland cities treated three times more industrial dust than did small towns at the 10% statistical level (Columns 2, 3, and 4, Table 5). Because the estimated results are unsatisfactory in towns, there is an urgent need for towns and villages to adopt eco-friendly production to protect the environment. According to the estimates for the southeast (Column 5, Table 5), the industrial dust treatment did not increase significantly. Despite the lack of significant reductions and increasing treatment of industrial dust discharges in the southeast, this cannot be equated with a lack of environmental protection because green manufacturing may still produce some dust

Column 2 in Table 6 shows that the estimated coefficient of is significant at the 1% statistical level, which implies that industrial wastewater treatment has increased with industrialisation in most places across China. Towns with chemical and paper industries have taken positive actions to protect their environment by treating industrial wastewater before discharge. It is also worth noting that foreign investment in high-energy-consuming and high-polluting industries have significantly worsened the local environment (Line 3, Table 6). These highly energy-consuming and polluting foreign factories are usually located in less-developed towns with no environmental protection infrastructure, which has created wastewater treatment challenges in China.

Table 7 shows that the treatment of solid hazards is not optimistic. According to the data on solid hazardous recycling, estimates suggest that the outlook of solid waste recycling is unsatisfactory in most places in China (Columns 2, 3, and 4, Table 7). The estimated results in Table 7 illustrate the negative relationships between solid hazardous recycling and economic growth in most cities and towns of China. In other words, the recycling volume of solid hazards has not kept pace with output growth. This unsatisfactory U-shaped EKC can be ascribed to the unaffordable, fast-rising recycling costs in towns.

After classifying cities and towns, it was found that less-developed towns, which could not afford high treatment costs, recycled fewer solid hazards than major cities (Columns 3 and 4, Table 7). Meanwhile, the southeast region did not show a significant increase in solid hazard recycling, which could be interpreted as a green transformation still in progress. Recently, clean production applications have become inelastic to income because of the high standards of environmental protection, which means that towns that accommodate pollution-intensive industries must bear a low-profit margin to treat industrial hazards before discharge. Therefore, there is an urgent need for low-tech and pollution-intensive industries to modernise towards higher productivity and more eco-friendly production.

Discussion

A crucial challenge for sustainable development is the reduction of industrial hazards through green transformation. This study aimed to determine whether there has been a shift towards green manufacturing by looking for an inverted U-shaped relationship between industrial hazardous waste and economic growth.

The study found that developed towns and cities with high administrative rankings in China have a greater likelihood of reducing industrial hazards. Sulphur dioxide emissions, wastewater, industrial dust, and hazardous solids have all been reduced and treated in advanced cities and towns, indicating that manufacturing has undergone green transformation.

Additionally, this study incorporated regional disparities in the EKC, which is more appropriate for developing countries. Compared with prior research by Uddin et al. (2019), this study examined whether there is still a general positive association between industrial pollution and economic growth, which, if regional variability is disregarded, could provide unrealistic suggestions for developing countries’ green transformation.

The administrative ranking disparity has been identified as one of the fundamental driving forces of green transformation in developing countries. Cities with high administrative rankings generally have the privilege of becoming green. The estimates of the classified groups show that administrative ranking, geographical endowments, and environmental protection have significant impacts on regional industrial pollution and the transition to eco-friendly manufacturing.

Based on the extensive EKC literature, which has estimated CO2, SO2, and other industrial hazards discharge per unit output at the national level,5,31,52,53 this study has focused on finding additional driving forces of the EKC, such as administrative ranking, and certifying whether the income level alters the relationship between hazardous discharge and economic growth. Although environmental disadvantages were found in developing countries, most studies omitted regional differences in identifying the sources of industrial pollution.37,39,54,55 In other words, this study addressed the omission of identifying the sources of industrial discharge by incorporating regional heterogeneity in terms of administrative standing in the EKC framework.

The primary contribution of this research is to identify the differences in administrative rank and geographic endowment that have a significant impact on regional industrial hazard discharge. The contributions made by the expanded EKC framework, regional estimates, and findings are as follows when compared to the body of literature:

First, as the regional heterogeneity categorised as administrative standing is the first time that it has emerged in an empirical EKC study, this study will provide guidelines for tailored regional environmental protection. In contrast, studies in the literature used fixed-effects regressions of panel data to estimate pollution sources, ignoring potential spatial impacts from neighbouring regions or, when spatial impacts were considered, focusing on the relationship between aggregate industrial hazardous discharges and outputs across countries without considering regional development differences between countries. This resulted in inconsistent and unreliable findings that lacked adequate explanation. 56

Second, this study accurately estimated the regional EKC using a spatial effect model. By excluding the spatial effects of neighbours, it accurately estimated the industrial hazards per unit of economic growth in the classified groups. Since spatial factors that affected individual towns were identified, speculation was made on how seriously a town could be polluted by its neighbours. 57 In short, the spatial estimation model has accurately examined the EKC in regions.

Third, this study suggests that administrative standing should be considered in the green transformation guidance of developing countries. Although research has found that energy-intensive industries are the primary cause of pollution, and only green innovation can reverse it, few have considered some cities green, and some are in inferior positions. This study integrates regional heterogeneity into the EKC framework to provide theoretical guidance for regional green transformation and environmental protection.

Conclusions

This study investigated the connections between hazardous industrial emissions and economic growth at the regional level in China based on the EKC concept to determine whether there is a green transformation. In other words, it reflects clean production progress in terms of industrial hazard reduction in these regions.

The study found a disassociation between industrial pollution and economic growth in southeastern cities. An inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and industrial sulphur dioxide emissions appeared in cities with high administrative rankings and in the southeast Environmental protection is more common in major cities than in urban areas.

This study found no evidence of disassociation between economic growth and solid waste or industrial dust Chinese cities have only made great progress in treating industrial sulphur dioxide; other areas, such as industrial solid waste recycling, dust treatment, and wastewater treatment, still require major improvements.

The EKC effect remains unclear and China's rural towns and villages are still in the process of going green. Industries with high energy requirements and pollution levels, such as those in metallurgy, chemicals, textiles, fertiliser, and printing, are typically found in outlying rural areas where they face a ‘pollute or produce’ choice. The demand for clean production and conservation is most significant in low-income towns, where environmental protection must be adequately implemented.

Generally, a developing country has three options for reducing hazardous discharge: (1) using green manufacturing, (2) treating before discharge, and (3) moving to pollution-intensive sectors. Using the aforementioned three methods, major cities can reduce their hazardous discharge per unit of output. However, small towns that are denied access to the Green City Fund have to continue polluting for survival.

This regional empirical study concluded that although China has pursued green transformation and industrial modernisation as a means of resolving the pollute-or-produce dilemma, only developed cities and towns with high administrative rankings are privileged to become green.

Potential applications and future case prospects

In developing nations, this field of study is active and expanding because there is an endless need to monitor hazardous industrial wastes, particularly in the post-industrial age. In-depth research is being conducted on the regional EKC to reflect the rate of green transformation in a developing nation; however, this study does not include measuring hazardous discharge in individual industries.

Forecasting the rate of green manufacturing transformation in every industry across the nation in the absence of classified industry information is challenging. Future statistical classifications will produce a thorough and precise income-pollution analysis for direct environmental protection.

Limitations

This study is limited in that the statistics of regional industrial hazardous discharge and total outputs are aggregated, but data on industrial pollution are not categorised by industry. To fill this gap, industry statistics on hazardous discharge should be collected for further evaluation of regional green manufacturing transformation. In other words, the study should be enriched with comprehensive and classified statistics to reflect the green transformation in each industry. Meanwhile, Kung et al. (2022)introduced an input monitoring system for material flows, which can be used to monitor hazardous discharge in extended environmental studies. 11 For the final stage of green transformation, the studies need to discuss how waste may be reutilised for sustainable development. 10

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to colleagues who provided very useful comments on the first draft of this paper, as well as anonymous reviewers and scholars who provided insightful and profound suggestions on how to improve the study. The author is responsible for all omissions and errors in this study.

Author biography

Jianing Hou was born in 1982. She received BSc and MSc degrees from the University of Birmingham in 2006 and 2008, respectively. After years of practical experience in public service, she returned to academics and received her Ph.D. from Hubei University in 2019. As a lecturer and postdoc, her current research interests include green manufacturing and regional development.

Appendix

Figure 9.

Industrial Sulphur Dioxide treated (tons). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Figure 10.

Industrial wastewater recycled (tons). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Figure 11.

Industrial wastewater treated (tons). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Figure 12.

Industrial dust treated (tons). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Figure 13.

Industrial solid waste recycled (tons). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/; Statistics of regional GDP in 100 million RMB.

Figure 14.

Industrial SO2 treated (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Figure 15.

Industrial wastewater treated (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Figure 16.

Industrial dust treated (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Figure 17.

Industrial solid waste recycled (tons) per capita 2007–2021. Source: The National Bureau of Statistics of China, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

Inland China consists of the north, the midland, and the west, Northern China includes, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Hebei, Shandong, Shānxi. Provinces of midland and west are Hubei, Hunan, Shǎnxi, Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai, Guangxi and Xinjiang.

Footnotes

The research findings presented in this study are included in the article and supplementary materials, and further enquiries can be directed to the author.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Wuhan Research Foundation, local manufacturing upgradation and civil epidemic, (grant number Project Number: IWHS20202042).

ORCID iD: Jianing Hou https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5174-2344

References

- 1.Sun J, Wang J, Wang T, et al. Urbanization, economic growth, and environmental pollution. Manag Environ Qual.: An International Journal 2019; 30: 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie Q, Xu X, Liu X. Is there an EKC between economic growth and smog pollution in China? New evidence from semiparametric spatial autoregressive models. J Clean Prod 2019; 220: 873–883. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soltmann C, Stucki T, Woerter M. The impact of environmentally friendly innovations on value added. E R E 2015; 62: 457–479. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaika D, Zervas E. The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory-part A: concept, causes and the CO2 emissions case. Energy Policy 2013; 62: 1392–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigatu G. The level of pollution and the economic growth factor: a nonparametric approach to environmental Kuznets curve. Quant Econ 2015; 13: 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott I, Soretz S. Green attitude and economic growth. E R E 2018; 70: 757–779. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang J, Zhang S, Zou Y, et al. The heterogeneous time and income effects in Kuznets curves of municipal solid waste generation: comparing developed and developing economies. Sci Total Environ 2021; 799: 149157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roca J, Padilla E, Farré M, et al. Economic growth and atmospheric pollution in Spain: discussing the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis. Ecol Econ 2001; 39: 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasperowicz R, Bilan Y, Štreimikienė D. The renewable energy and economic growth nexus in European countries. Sustain Dev 2020; 28: 1086–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kung C-C, Zheng B, Li H, et al. The development of input-monitoring system on biofuel economics and social welfare analysis. Sci Prog 2022; 105: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kung C-C, Fei CJ, McCarl BA, et al. A review of biopower and mitigation potential of competing pyrolysis methods. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2022; 162: 112443. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed Z, Asghar MM, Malik MN, et al. Moving towards a sustainable environment: the dynamic linkage between natural resources, human capital, urbanization, economic growth, and ecological footprint in China. Resour Policy 2020; 67: 101677. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahjabeen, Shah SZA, Chughtai S, et al. Renewable energy, institutional stability, environment and economic growth nexus of D-8 countries. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020; 29: 84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso-Carrera J, Miguel CD, Manzano B. Economic Growth and Environmental Degradation When Preferences are Non-homothetic. E R E 2019; 74: 1011–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng J-C, Tang S, Yu Z. Integrated development of economic growth, energy consumption, and environment protection from different regions: based on city level. Energy Procedia 2019; 158: 4268–4273. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mania E. Export diversification and CO2 emissions: an augmented environmental Kuznets curve. J Int Dev 2020; 32: 168–185. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pata UK, Caglar AE. Investigating the EKC hypothesis with renewable energy consumption, human capital, globalization and trade openness for China: Evidence from augmented ARDL approach with a structural break. Energy 2021; 216: 119220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahbaz M, Mahalik MK, Shahzad SJH, et al. Does the environmental Kuznets curve exist between globalization and energy consumption? Global evidence from the cross-correlation method. Int J Fin Econ 2019; 24: 540–557. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castiglione C, Infante D, Smirnova J. Environment and economic growth: is the rule of law the go-between? The case of high-income countries. Energy Sustain Soc 2015; 5: 26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li B, Wu X. Economic structure and intensity influence air pollution model. Energy Procedia 2011; 5: 803–807. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han X, Zhang M, Su L. Research on the relationship of economic growth and environmental pollution in shandong province based on environmental Kuznets curve. Energy Procedia 2011; 5: 508–512. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson C, Persson J. Economic growth, inequality, democratization, and the environment. E R E 2003; 25: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smulders S. Economic growth and the diffusion of clean technologies: explaining environmental kuznets curves. E R E. 2011; 49: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehman Khan SA, Zhang Y, Anees M, et al. Green supply chain management, economic growth and environment: a GMM based evidence. J Clean Prod 2018; 185: 588–599. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barua A, Hubacek K. Water pollution and economic growth: an Environmental Kuznets Curve analysis at the watershed and state level. Sov Phys Doklady 2008; 29: 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong KK. Energy consumption, economic growth, and environmental degradation in OECD countries. A J E E R 2020; 7: 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borhan HB, Ahmed EM. Pollution as one of the determinants of income in Malaysia: comparison between single and simultaneous equation estimators of an EKC. W J S T S D 2010; 7: 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dasgupta S, Hamilton K, Pandey KD, et al. Air pollution during growth: accounting for governance and vulnerability. P R W P 2004; 3383: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole MA. Air pollution and ‘dirty industries: how and why does the composition of manufacturing output change with economic development? E R E 2000; 17: 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borhan H, Ahmed EM. Green environment: assessment of income and water pollution in Malaysia. Procedia Soc 2012; 42: 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uddin GA, Alam K, Gow J. Ecological and economic growth interdependency in the Asian economies: an empirical analysis. E S P R 2019; 26: 13159–13172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek J, Kim HS. Is economic growth good or bad for the environment? Empirical evidence from Korea. Energy Econ 2013; 36: 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan R. Influence of environmental degradation and economic growth on CO2 emissions: evidence from developing countries. A J E E R 2020; 7: 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilinc-Ata N, Dolmatov IA. Which factors influence the decisions of renewable energy investors? Empirical evidence from OECD and BRICS countries. E S P R 2022; 22: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naseem S, Mohsin M, Zia-Ur-Rehman M. The influence of energy consumption and economic growth on environmental degradation in BRICS countries: an application of the ARDL model and decoupling index. E S P R 2022; 29: 13042–13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aytun C, Akin CS. Can education lower the environmental degradation? Bootstrap panel Granger causality analysis for emerging countries. Environ Dev Sustain.: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development 2022; 24: 10666–10694. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia W, Apergis N, Bashir MF, et al. Investigating the role of globalization, and energy consumption for environmental externalities: empirical evidence from developed and developing economies. Renew Energy 2022; 183: 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou J, Chen S-C, Xiao D. Measuring the benefits of the “one belt, one road” initiative for manufacturing industries in China. Sustainability 2018; 10: 4717. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Lai X. EKC And carbon footprint of cross-border waste transfer: evidence from 134 countries. Ecol Indic 2021; 129: 107961. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett RJ, Haining RP. Spatial structure and spatial interaction: modelling approaches to the statistical analysis of geographical data. J R Stat Soc. Series A (General) 1985; 148: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luc A, Daniel AB. Spatial fixed effects and spatial dependence in a single cross-section. Pap Reg Sci 2013; 92: 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anselin L, Syabri I, Kho Y. Geoda: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr Anal 2006; 38: 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Özyurt S, Daumal M. Trade openness and regional income spillovers in Brazil: a spatial econometric approach. Pap Reg Sci 2013; 92: 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aquaro M, Bailey N, Pesaran MH. Estimation and inference for spatial models with heterogeneous coefficients: an application to US house prices. J Appl Econ 2021; 36: 18–44. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng L, Feng L, Li Z. Model abstraction for discrete-event systems by binary linear programming with applications to manufacturing systems. Sci Prog 2021; 104: 00368504211030833. doi: 10.1177/00368504211030833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma S, Weng J, Wang C, et al. Bus passenger flow congestion risk evaluation model based on the pressure-state-response framework: a case study in Beijing. Sci Prog 2019; 103: 0036850419883567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anselin L, Hudak S. Spatial econometrics in practice: a review of software options. Reg Sci Urban Econ 1992; 22: 509–536. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anselin L, Gallo JL, Jayet H. Spatial Panel Econometrics . The econometrics of panel data. Berlin: Springer, 2008, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anselin L. Interactive Techniques And Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis. Regional Research Institute Working Papers. 1996. http://researchrepository.wvu.edu

- 50.Elhorst JP. Spatial Econometrics From Cross-Sectional Data To Spatial Panels. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elhorst JP, Gross M, Tereanu E. Cross-sectional dependence and spillovers in space and time: where spatial econometrics and global VAR models meet. J Econ Surv 2021; 35: 192–226. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stokey NL. Are there limits to growth? I E R 1998; 39: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang C, Zhao Z, Zhang Z. Empirical Study of Regional Innovation Capability and Economic Convergence in China. In: China’s New Sources of Economic Growth. Canberra: ANU Press, 2017, pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang W, Liang B, Xia K, et al. Decoupling of carbon emissions from economic growth: an empirical analysis based on 264 prefecture-level cities in China. C J U E S 2021; 9: 2150017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doan B, Driha OM, Lorente DB, et al. The mitigating effects of economic complexity and renewable energy on carbon emissions in developed countries. Sustain Dev 2021; 29: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharif A, Mishra S, Sinha A, et al. The renewable energy consumption-environmental degradation nexus in top-10 polluted countries: fresh insights from quantile-on-quantile regression approach. Renew Energy 2020; 150: 670–690. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dastidar AG. Income distribution and structural transformation: empirical evidence from developed and developing countries. Soc Sci Electro Publish 2012; 25: 25–56. [Google Scholar]