Abstract

Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) offers a less invasive management option for bariatric cancer patients. As the proportion of Australians categorised overweight or obese approaches 70%, it is not well understood how this growth will impact RT departments. The aim of this study was to evaluate the current and potential future body mass index (BMI) of RT patients at one centre, with the purpose of identifying variables that may impact resource planning decisions.

Methods

De‐identified demographic data including gender, age, diagnosis code, activity code and BMI were obtained from MOSAIQ® oncology information system for 5548 courses of RT commenced between 2017 and 2020, and retrospectively analysed. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. Simple and multiple linear regression was used to analyse for statistically significant relationships between variables.

Results

Of all patient courses, 64% were overweight or obese. Average BMI increased over time by 0.3 kg/m2 per year. Courses related to the young and elderly had a lower average BMI. Breast, brain/skull, and pelvis/prostate treatment sites had a significant association with a higher average BMI. Thorax treatment sites had a lower average BMI, but this average is increasing at the fastest rate of all treatment sites. Prone breast courses had an average BMI 5.58 kg/m2 higher than IMRT/VMAT courses.

Conclusion

Results demonstrate that patient BMI is increasing. Resources related to breast courses (breast board, prone board) and thorax courses (lung board) may experience increased strain in the future. Modifications to department workflow and scheduling are likely required. Further research into staffing implications is recommended.

Keywords: BMI, body mass index, equipment, immobilisation, obesity, radiation therapy, resourcing, safe working load

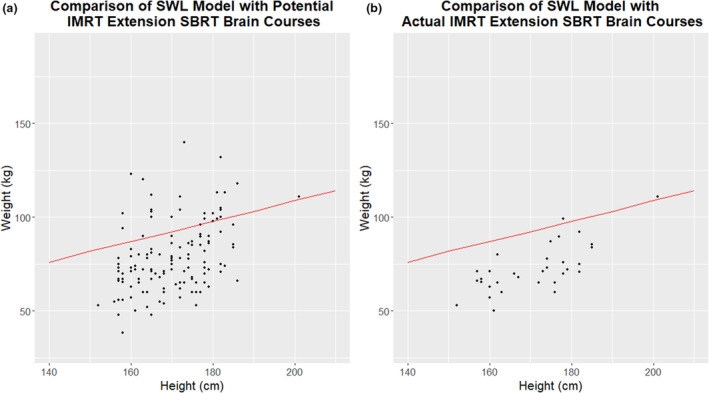

Radiation therapy offers a less invasive management option for bariatric cancer patients. As the proportion of Australians categorised overweight or obese approaches 70%, it is not well understood how this growth will impact RT department resources. Weight‐limited equipment is already impacting immobilisation equipment choices for patients and lessening their treatment options. Illustrating this point, this graph demonstrates patients who potentially required treatment on the IMRT extension but were over the safe working load (red line).

Introduction

By the age of 85, one in two Australians will be diagnosed with cancer. 1 This represents a new diagnosis every 4 min. 1 Contributing to this cancer burden is obesity, a modifiable risk factor that continues to increase. 1 Currently, the proportion of Australians who are overweight or obese has risen to two‐thirds of the population, 2 and is predicted to increase to 80% of adults by 2025. 3 , 4

The World Health Organisation defines overweight as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. 5 Bariatric is typically defined as a BMI ≥40 kg/m2. 6 Body mass is an important consideration in the clinical management of cancer. In patients with an elevated BMI, surgical management carries a substantial risk of complications. 7 In contrast, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) offers a less invasive option. 8 Existing literature highlights the challenges in delivering accurate radiation therapy to the obese population; the technical constraints including field of view limitations, degradation to image quality and the necessity for additional reconstruction algorithms to accurately reflect the density of tissues have been investigated. 9 , 10 Physical constraints such as the diameter of computed tomography (CT) scanners and the weight tolerances of machine tables have been explored. 11 , 12 , 13 Furthermore, immobilisation equipment comfort, accuracy and reproducibility have been investigated across a variety of body habitus. 14 , 15 , 16 The author's research demonstrated that consideration of patient BMI is important when selecting the most effective immobilisation equipment. In addition to this, studies have shown the obese population frequently required daily imaging with correctional shifts, 8 , 13 , 17 concluding that obese patients were at a greater risk of geographical miss compared to non‐obese patients.

These studies leave a gap in understanding how this growing population could potentially impact department resources in the future, including understanding patient BMI distribution and how this could affect equipment acquisition and overall wear and tear.

This retrospective quality assurance study aimed to evaluate the current and potential trends in BMI of radiation therapy patients at one centre, with the objective of identifying variables that may have an impact on resource planning decisions for a radiation oncology department.

Methods

Patient data

QUT HREC Low Risk Approval (2000001103) and institutional ethics approval were granted (HREC/2020/QRBW/71878) to retrospectively access the data of all courses of radiation therapy at the Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital (RBWH) between January 2017 and December 2020. The data were retrieved from the MOSAIQ® Oncology Information System (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) and included the following demographic data: ICD10‐AM diagnosis code, gender, activity code, start date, date of birth, height, weight, BMI and assessment date. All patient identifiers were removed. This extraction yielded a total of 5607 records. Given the nature of radiation therapy, a portion of courses may relate to the same patient, for example, a patient had radiation treatment to their breast, and then later had treatment to their spine, or a patient with skin cancer may have several courses of treatment to different sites of their body.

Data cleaning

A timeframe of 6 months was used to validate if an assessment was relevant to the respective course, as the general follow‐up period at this centre is 6 months post‐treatment. Any records with assessment dates greater than 6 months before or after the course start date were removed. Extreme values and inconsistent assessments were also reviewed by two co‐investigators and removed or corrected where verifiable. The total number of records remaining in the cleaned data set was 5458.

Data analysis

The cleaned data set was imported to R statistical software (https://www.r‐project.org/) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. Regression analysis was performed, given its versatility in handling data and comparability. BMI and age, gender, treatment site and treatment technique were analysed for statistically significant relationships using both simple linear regression and multiple linear regression. Bootstrapping was performed on all regression models to ensure the 95% confidence intervals were robust and to account for the non‐parametric tail evident in BMI data. Each coefficient had 10,000 bootstrap samples applied. The assumptions of linear regression were validated for each model. A P‐value of <0.05 was used to assess statistical significance for all data.

Results

Numerical summary

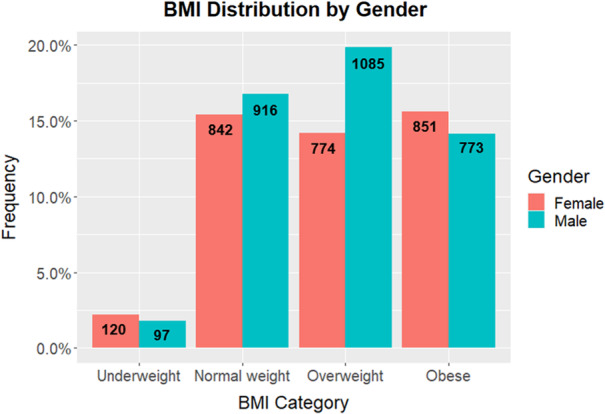

Patients were reported as overweight (34%), normal weight (32%), obese (30%) and underweight (4%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

BMI distribution by gender with raw count data.

The most common treatment sites were head and neck (22%), pelvis/prostate (19%), thorax (16%), breast (16%) and brain/skull (9%) (Table 1). Breast treatments had the highest mean BMI of 29.2 kg/m2 (SD = 6.9). The lowest mean BMI was seen in total body irradiation treatments, averaging 26.6 kg/m2 (SD = 5.9).

Table 1.

Numerical summary of data of all courses of radiation therapy between January 2017‐December 2020.

| N | Mean (kg/m2) | SD | BMI range (kg/m2) | Avg BMI category | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment site | |||||

| Head and neck | 1209 | 27.1 | 5.8 | 13.0–61.3 | Overweight |

| Pelvis/Prostate | 1028 | 28.5 | 6.4 | 14.8–60.9 | Overweight |

| Thorax | 896 | 26.7 | 6.2 | 13.4–60.6 | Overweight |

| Breast | 870 | 29.2 | 6.9 | 13.0–60.3 | Overweight |

| Brain/Skull | 512 | 27.8 | 6.3 | 14.9–70.5 | Overweight |

| Multiple areas | 323 | 27.1 | 6.2 | 14.7–50.4 | Overweight |

| Spine | 247 | 26.7 | 6.1 | 16.4–38.3 | Overweight |

| Abdomen | 150 | 27.6 | 7.4 | 15.4–53.8 | Overweight |

| Other | 114 | 27.1 | 6.1 | 15.6–48.3 | Overweight |

| Limb | 77 | 27.4 | 5.8 | 16.9–43.7 | Overweight |

| Total body irradiation | 32 | 26.6 | 5.9 | 17.4–39.2 | Overweight |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 35 | 23.9 | 6.5 | 14.7–48.3 | Normal weight |

| 25–34 | 108 | 26.3 | 6.4 | 17.3–46.2 | Overweight |

| 35–44 | 291 | 27.3 | 6.4 | 15.1–53.9 | Overweight |

| 45–54 | 769 | 28.1 | 6.4 | 15.1–58.6 | Overweight |

| 55–64 | 1354 | 28.2 | 6.9 | 13.0–70.5 | Overweight |

| 65–74 | 1727 | 28.0 | 6.4 | 13.4–61.3 | Overweight |

| 75–84 | 921 | 26.9 | 5.4 | 13.0–58.4 | Overweight |

| 85+ | 253 | 25.4 | 4.8 | 16.0–40.5 | Overweight |

| Treatment technique | |||||

| IMRT/VMAT | 2726 | 28.1 | 6.3 | 13.0–70.5 | Overweight |

| Tomotherapy | 1265 | 27.9 | 6.6 | 13.0–59.2 | Overweight |

| 3DCRT | 1191 | 26.5 | 6.1 | 13.9–61.3 | Overweight |

| Other | 259 | 26.6 | 5.9 | 15.1–50.3 | Overweight |

| Prone Breast | 17 | 33.7 | 6.7 | 22.5–47.6 | Obese |

BMI Classification: <18.5 = Underweight; 18.5–24.9 = Normal weight; 25–29.9 = Overweight; ≥30 = Obese.

The most common age group was 65–74 years (32%). The highest mean BMI was in the 55–64 years of age group with a mean BMI of 28.2 kg/m2 (SD = 6.9). The lowest mean BMI was in the 18–24 years of age group, with a mean BMI of 23.9 kg/m2 (SD = 6.5).

IMRT/VMAT on a linear accelerator was the most common treatment technique (50%). Prone breast had the highest mean BMI of 33.7 kg/m2 (SD = 6.7). 3DCRT courses had the lowest mean BMI of 26.5 kg/m2 (SD = 6.1).

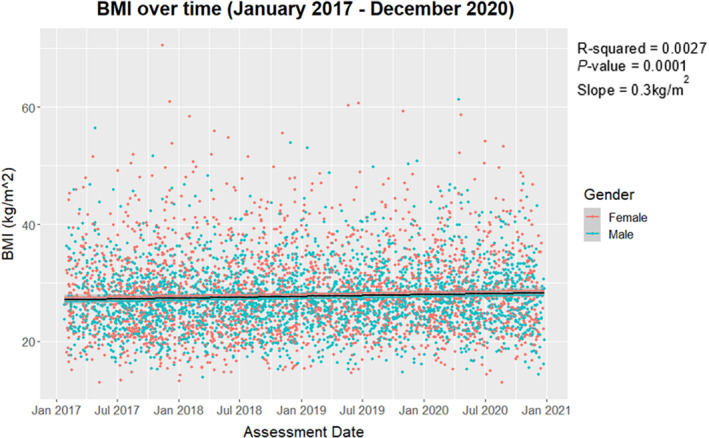

Time‐series analysis

Linear regression of BMI over time (Fig. 2) demonstrated that time had a significant effect on BMI (F 1,5456 = 14.96, P < 0.001). On average, BMI increased by 0.3021 kg/m2 per year (95%CI: 0.1499, 0.4539). The data were further subset and analysed by BMI category; however, none of the time‐series models showed a statistically significant effect.

Figure 2.

BMI (kg/m2) over time from January 2017 to December 2020 highlighted by gender, with regression line plotted.

Further time‐series analysis was performed on the most common treatment sites. Breast, head and neck and brain/skull treatment sites all showed an increase in average BMI per year, representing 0.3050 kg/m2 (95%CI: −0.0926, 0.6865), 0.2597 kg/m2 (95%CI: −0.0461, 0.5723) and 0.0987 kg/m2 (95%CI: −0.4834, 0.6590) respectively. None of these models were statistically significant and should be interpreted with caution. Thorax was the only treatment site analysed which showed a statistically significant effect on average BMI (F 1,894 = 6.416, P = 0.011). For this group, average BMI increased by 0.4743 kg/m2 per year.

Regression models

Multiple linear regression was conducted to compare the effect of gender, age group, treatment site and treatment technique on BMI. The effect of gender on BMI was not significant when considering age group, treatment site and treatment technique (P = 0.283). Therefore, gender was removed from the model. Multi‐collinearity was evident between treatment site and treatment technique, violating the assumption of regression, and therefore, technique was removed as it affected model performance metrics the least. Consequently, simple linear regression was conducted to compare the effect of treatment technique on BMI, while multiple linear regression was conducted to compare the effect of age group and treatment site on BMI.

Simple linear regression

Model 1 (Table 2) demonstrated the effect of treatment technique on BMI was significant (F 4,5453 = 19.51, P < 0.001). Prone breast demonstrated the greatest difference in BMI, with an average BMI 5.58 kg/m2 greater (95%CI: 2.81, 9.39) than courses treated with IMRT/VMAT. This technique did demonstrate a large standard error and wide confidence interval, suggesting caution in interpreting the estimate coefficient. However, the bounds of the confidence interval did support the conclusion of a higher average BMI.

Table 2.

Simple linear regression results for treatment technique.

| Model 1 – Treatment technique | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Estimate (average BMI, kg/m2) | 95% CI | SE | P‐value |

| IMRT/VMAT 1 | 28.13 | 27.90, 28.37 | 0.121 | <0.001* |

| 3DCRT | 26.53 (−1.60) | −2.02, −1.18 | 0.214 | <0.001* |

| Other | 26.61 (−1.52) | −2.24, −0.74 | 0.381 | <0.001* |

| Prone Breast | 33.71 (5.58) | 2.81, 9.39 | 1.623 | <0.001* |

| Tomotherapy | 27.93 (−0.20) | −0.64, 0.21 | 0.219 | 0.342 |

Indicates a statistically significant result.

Reference category.

Multiple linear regression

The final regression model was Course BMI = b 0 + b 1*age group + b 2*treatment site.

This model (Model 2, Table 3) showed the effect of age group and treatment site on BMI was statistically significant overall (F 17,5440 = 11.07, P < 0.001). When accounting for treatment site, the age groups 18–24 and 85+ had the greatest difference, with an average BMI 4.01 (95%CI: −5.89, −1.27) and 2.64 kg/m2 (95%CI: −3.33, −1.93) lower than the 55–64 age group. The 18–24 age group demonstrated a large standard error and wide confidence interval, suggesting caution in interpreting the estimate. This may be due to the small number of courses in this group creating uncertainty. However, the bounds of the confidence interval still supported a lower BMI on average.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression results for age group and treatment site.

| Model 2 – Age group and treatment site | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Estimate (average BMI, kg/m2) | 95% CI | SE | P‐value |

| Thorax+55–64 1 | 27.28 | 26.78, 27.81 | 0.262 | <0.001* |

| 18–24 | 23.27 (−4.01) | −5.89, −1.27 | 1.133 | <0.001* |

| 25–34 | 25.33 (−1.95) | −3.14, −0.63 | 0.639 | 0.002* |

| 35–44 | 26.05 (−1.23) | −2.07, −0.39 | 0.427 | 0.002* |

| 45–54 | 26.99 (−0.29) | −0.89, 0.30 | 0.301 | 0.295 |

| 65–74 | 27.17 (−0.11) | −0.59, 0.36 | 0.242 | 0.616 |

| 75–84 | 26.09 (−1.19) | −1.70, −0.69 | 0.257 | <0.001* |

| 85+ | 24.64 (−2.64) | −3.33, −1.93 | 0.357 | <0.001* |

| Abdomen | 28.16 (0.88) | −0.27, 2.18 | 0.630 | 0.113 |

| Brain/Skull | 28.22 (0.94) | 0.28, 1.64 | 0.344 | 0.007* |

| Breast | 29.59 (2.31) | 1.71, 2.96 | 0.318 | <0.001* |

| Head and neck | 27.65 (0.37) | −0.15, 0.89 | 0.265 | 0.178 |

| Limb | 28.06 (0.78) | −0.57, 2.20 | 0.703 | 0.293 |

| Multiple areas | 27.43 (0.15) | −0.63, 0.94 | 0.398 | 0.722 |

| Other | 27.85 (0.57) | −0.58, 1.79 | 0.600 | 0.365 |

| Pelvis/Prostate | 29.07 (1.79) | 1.24, 2.35 | 0.284 | <0.001* |

| Spine | 27.18 (−0.10) | −0.91, 0.80 | 0.437 | 0.822 |

| Total body irradiation | 28.03 (0.75) | −1.18, 3.13 | 1.082 | 0.489 |

Indicates a statistically significant result.

Reference category. Age is described in years.

When considering differences in BMI due to age group, brain/skull, breast and pelvis/prostate treatment sites showed a statistically significant association with BMI. Breast demonstrated the largest difference, with an average BMI of 29.59 kg/m2 (95%CI: 1.71, 2.96).

Discussion

This retrospective quality assurance study evaluated the current trends in patient BMI and the potential impact on radiation therapy department resourcing. The results of this study suggest the current radiation therapy patient base is trending similar to the general population, with 66% of courses in the study overweight or obese, which is the same proportion observed by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in the latest available year of data (2017–2018). 2 The number of courses relating to overweight or obese patients increased by 9.8% between 2017 and 2020. This is in agreement with predictive models in literature which estimate up to 83% of males and 75% of females will be overweight or obese by 2025. 4 The time‐series analysis also demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between time and average BMI (0.3 kg/m2 per year).

Growth in obesity across the general population has the potential to significantly impact radiation therapy services. It has been documented that obese patients are at a greater risk of surgical complications, namely due to anaesthetic risks and a high likelihood of associated comorbid conditions. 18 , 19 Deneuve and colleagues reported that 20 of their 111 obese patients had their treatment modified as a direct consequence of their obesity. 20 Thirteen of these were treated with radiation therapy instead of surgery due to anaesthetic risks. Davies and colleagues discussed similar findings; a trend towards non‐surgical treatment modalities with increasing BMI in prostate cancer patients. 21 While surgical practices may have improved since publication of these articles, the point remains that departments need to future proof services as radiation therapy may be the only viable option for many in this population.

Several variables were analysed for an association with BMI as a part of this study. Discrepancies in BMI between genders were likely due to differences in treatment site and age. Furthermore, patients who are 18–44 or 75+ years of age were likely to have a lower BMI than middle‐aged groups, when adjusted for differences in treatment site. Population data and predictive models are in agreement with this middle‐late age BMI peak. 2 , 3 , 4

Analysis of treatment technique demonstrated prone breast courses had the greatest average BMI (33.71 kg/m2, 95%CI: 25.32, 37.52). This association is supported in literature, as it is reported that bariatric women have larger breast size due to the distribution of adipose tissue. 22 Prone position on a commercially designed board with an aperture for the breast has been shown to be the most common and highly ranked treatment position for these women. 14 Moreover, Krengli and colleagues reported in their study of pendulous breast patients that 70% were treated in the prone position due to superior treatment plans. 23 Departments should consider reviewing their standard operating procedures to include the use of prone positioning for this category of patients. At this centre, 3DCRT is typically used for palliative cases, while IMRT/VMAT is the most common planning approach. Broadly speaking, patient size is not a consideration when selecting the planning technique, and therefore, any relationship with BMI is more likely due to multicollinearity between treatment site and technique.

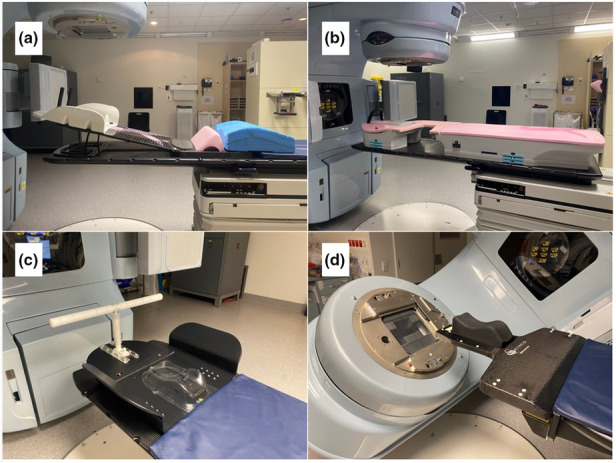

Pertinent to adequate department resourcing is the acquisition and maintenance of immobilisation equipment. The most frequent treatment sites: breast, thorax and brain/skull, all utilise immobilisation equipment (Fig. 3) with specified safe working loads (SWL), set with the assumption that weight is evenly distributed on the equipment. As the most heavily used, they are also at the greatest risk of malfunction.

Figure 3.

(A) QFix supine breast board. (B) QFix prone breast board (with aperture set to the left breast). (C) Civco lung board. (D) Civco IMRT Extension with a floor rotation allowing non‐coplanar treatments.

The results indicate possible increased wear and tear on both supine breast boards (limit = 249 kg) and prone breast boards (limit = 225 kg). Although time‐series analysis of future growth was inconclusive, breast courses already demonstrated the largest average BMI (29.59 kg/m2). Anecdotally, the study department experienced malfunction of the supine breast board during the treatment of a patient with a BMI of 44.8 kg/m2. This highlights that, while no course has exceeded the SWL, the uniformity of a patient's weight is important to consider. Additionally, the weight load on different components of the breast board while the patient is positioning themselves could be a safety consideration.

Analysis of brain/skull treatment courses demonstrated that this site is not rapidly increasing in BMI; however, the IMRT extension board SWL is already exceeded by many patients. The average BMI for brain/skull treatment courses is moderate (28.22 kg/m2), while the IMRT extension board has a comparatively low weight tolerance (couch attachment limit = 45 kg, extension limit = 25 kg). Depending on a patient's height, weight and body habitus, a large portion of their body weight may be in their upper body and therefore supported by the equipment. The study site developed a model to evaluate patient suitability. Stereotactic brain treatments (SBRT) were specifically analysed, as these most commonly require a floor rotation and therefore use of the IMRT extension. Figure 4 demonstrates the portion of SBRT courses who have been potentially excluded from treatment on this equipment due exceeding the SWL.

Figure 4.

(A) Potential courses requiring the IMRT extension. (B) Actual courses treated on the IMRT extension post‐implementation of the study site IMRT extension model. The red line indicates safe working load limit as validated by the study site model.

Thorax sites demonstrated a statistically significant increase in average BMI (0.47 kg/m2 per year) and as a result the lung board (limit = 91 kg on wings) is likely to be subject to greater strain in the future. However, as this site currently has one of the lowest average BMIs (27.28 kg/m2), and each arm approximates 5% of total body weight, 24 wear and tear does not present an imminent problem and resourcing for this future demand can be prioritised accordingly.

It should be noted that alternatives do exist. As summarised by Colciago and colleagues, 3DCRT can increase dose inhomogeneity in patients with large breast size. IMRT and VMAT techniques can improve homogeneity, which is a factor believed to influence long‐term toxicity and cosmetic outcomes. 25 Furthermore, the dosimetric manipulation and organ‐sparing that is achievable with VMAT breast planning has furthered advancements such as altered fractionation schedules, partial breast irradiation and hybrid techniques. 26 For the study site, the advent of VMAT planning has increased the use of the lung board, as the breast board creates a collision risk during arc delivery. Nevertheless, this technique is not suitable for all patients. Similarly, stereotactic radiosurgery boards have higher safe working loads (249 kg); 27 however, this equipment and associated technology is not available to all departments and is a high‐cost alternative. For these reasons, it is essential departments ensure not only an adequate repair and replacement policy but also correct usage of the devices given the variable load bearing capabilities and potential for an incident to occur.

There are no comparable studies addressing BMI trends in radiation therapy. In radiography, it has been documented that some patients are unable to obtain imaging studies due to weight or girth exceeding equipment limits. 12 In radiation therapy, Mohiuddin and colleagues 28 described a breast cancer patient treated using an upright, standing technique due to exceeding the weight limitation of their CT/treatment couch. Batumalai et al. 29 mention that several large body habitus breast cancer patients had to be excluded from their study of set‐up errors due to collision risk between the gantry head and the patient during imaging. These papers hint that departments are experiencing equipment limitations when it comes to bariatric patients, despite it not being widely reported.

Anecdotally, smaller departments have had to refer bariatric patients to the study site due to insufficient staffing and equipment necessary to provide safe care. This is also reported in literature, with Cowley and Leggett 30 suggesting these referrals increase the demand on bariatric‐capable departments. This paper also acknowledges that hospital equipment is typically designed for a different body shape to bariatric patients, which can lead to issues with centre of gravity and overbalancing despite being appropriately weight‐rated. 30

Workflow issues associated with bariatric patients are discussed in the literature, establishing that this demographic takes longer to set up due to the mobility of skin tattoos relative to bony structures. 13 , 17 Additionally, they are more prone to set up errors and require daily imaging to ensure target accuracy. 8 , 13 , 17 Winters and Poole 13 observed in their focus group interviews of radiation therapists that obese patients took longer to mount and dismount the bed, which, in addition to longer set up time and increased imaging requirements, further increased time delays on the treatment unit.

Limitations

BMI does not account for girth or body composition such as central adiposity, which vary with age, gender and ethnicity. 31 Two individuals with the same BMI may carry their body weight in different ways and therefore present different issues in the treatment process. Additionally, a longer time period of data may be needed to obtain results with a higher degree of accuracy and lower error rate in order to produce reliable predictive modelling. Moreover, the volume of data available in this study increases the risk of incorrectly determining a statistically significant association. 32 This risk has been reduced as much as possible by evaluating the effect size and applying bootstrapping to increase confidence in the results. Lastly, this study focused primarily on equipment resourcing. There are many other important aspects of department resourcing that are impacted by the increase in bariatric patients which have not been addressed in this study. This includes safe staffing, manual handling and patient management.

Conclusion

This study highlights the current BMI distribution of radiation therapy patients and evaluates the trends for future growth. Of particular interest was the impact of overweight and obese patients on department resources. BMI is increasing in the RT patient population, with the highest BMI observed in the most common treatment sites. Departments need to future proof services, as radiation therapy may be the only viable option for many patients in the future. Repeated excessive load placed on immobilisation equipment increases the likelihood of equipment malfunction or failure. The results suggest breast and brain/skull treatment sites are at greatest risk of exceeding the weight tolerances of equipment. It is recommended that the breast boards and IMRT extension board are frequently monitored and serviced to prevent wear and tear. A clear replacement policy should also be instituted to avoid equipment failure and facilitate upgrading. Beyond equipment resourcing, further research is required to understand the impact of this population on staffing and scheduling resources.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Information

This research did not receive internal or external funding.

Ethics Statement

Granted by QUT human Research Ethics Committee and Metro North Human Research Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of staff across both QUT and Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital Radiation Oncology in the completion of this study.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Cancer. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, 2020. [cited 2021 Sept 28]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports‐data/health‐conditions‐disability‐deaths/cancer/overview. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Overweight and Obesity: An Interactive Insight. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, 2020. June [cited 2021 Sept 22]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight‐obesity/overweight‐and‐obesity‐an‐interactive‐insight/data. Table S4: Age‐standardised and crude proportions of overweight and obese persons aged 18 and over, 1995 to 2017–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hayes A, Lung T, Bauman A, Howard K. Modelling obesity trends in Australia: Unravelling the past and predicting the future. Int J Obesity 2017; 41: 178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haby M, Markwick A, Peeters A, et al. Future predictions of body mass index and overweight prevalence in Australia, 2005–2025. Health Promot Int 2011; 27: 250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organisation . Obesity and Overweight, 2020. [cited 2020 Sept 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/obesity‐and‐overweight

- 6. Swann J. Understanding the difference between overweight, obese and bariatric. J Paramed Pract 2013; 5: 436–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Renehan AG, Harvie M, Cutress RI, et al. How to manage the obese patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 4284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bray TS, Kaczynski A, Albuquerque K, et al. Role of image guided radiation therapy in obese patients with gynecologic malignancies. Pract Radiat Oncol 2012; 3: 249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Modica MJ, Kanal KM, Gunn ML. The obese emergency patient: Imaging challenges and solutions. RadioGraphics 2011; 31: 811–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheung JP, Shugard E, Mistry N, et al. Evaluating the impact of extended field‐of‐view CT reconstructions on CT values and dosimetric accuracy for radiation therapy. Med Phys 2018; 46: 892–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uppot RN. Impact of obesity on radiology. Radiol Clin North Am 2007; 45: 231–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carucci LR. Imaging obese patients: Problems and solutions. Abdom Imaging 2012; 38: 630–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winters E, Poole C. Challenges and impact of patient obesity in radiation therapy practice. Radiography 2020; 26: e158–e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barrett‐Lennard M, Thurstan S. Comparing immobilisation methods for the tangential treatment of large pendulous breasts. Radiographer 2008; 55: 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen G, Dong B, Shan G, et al. Choice of immobilization of stereotactic body radiotherapy in lung tumor patient by BMI. BMC Cancer 2019; 19: 583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sio TT, Jensen AR, Miller RC, et al. Influence of patient's physiologic factors and immobilization choice with stereotactic body radiotherapy for upper lung tumors. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2014; 15: 235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wong JR, Gao Z, Merrick S, et al. Potential for higher treatment failure in obese patients: Correlation of elevated body mass index and increased daily prostate deviations from the radiation beam isocenters in an analysis of 1,465 computed tomographic images. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009; 75: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pandit JJ, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Project (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia: Summary of main findings and risk factors. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113: 549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shearer ES. Obesity anaesthesia: The dangers of being an apple. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110: 172–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deneuve S, Tan HK, Eghiaian A, Temam S. Management and outcome of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas in obese patients. Oral Oncol 2011; 47: 631–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davies BJ, Walsh TJ, Ross PL, et al. Effect of BMI on primary treatment of prostate cancer. Urology 2008; 72: 406–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ooi BN, Loh H, Ho PJ, et al. The genetic interplay between body mass index, breast size and breast cancer risk: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2019; 48: 781–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krengli M, Masini L, Caltavuturo T, et al. Prone versus supine position for adjuvant breast radiotherapy: A prospective study in patients with pendulous breasts. Radiat Oncol 2013; 8: 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tözeren A. Human Body Dynamics Classical Mechanics and Human Movement, 1st edn. Springer, New York, NY, 2000. 302 p. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Colciago RR, Cavallo A, Magri M, et al. Hypofractionated whole‐breast radiotherapy in large breast size patients: Is it really a resolved issue? Med. Oncologia 2021; 38: 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cozzi L, Lohr F, Fogliata A, et al. Critical appraisal of the role of volumetric modulated arc therapy in the radiation therapy management of breast cancer. Radiat Oncol 2017; 12: 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qfix . Encompass SRS Immobilization System. Submillimeter Immobilization. Qfix, Avondale, PA: [cited 2022 Oct 13]. Available from: https://qfix.com/sites/default/files/2005477_Brochure,%20Encompass_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohiuddin MM, Zhang B, Tkaczuk K, Khakpour N. Upright, standing technique for breast radiation treatment in the morbidly‐obese patient. Breast J 2010; 16: 448–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Batumalai V, Phan P, Choong C, Holloway L, Delaney GP. Comparison of setup accuracy of three different image assessment methods for tangential breast radiotherapy. J Med Radiat Sci 2016; 63: 224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cowley SP, Leggett S. Manual handling risks associated with the care, treatment and transportation of bariatric patients and clients in Australia. Int J Nurs Pract 2010; 16: 262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sung H, Siegel RL, Torre LA, et al. Global patterns in excess body weight and the associated cancer burden. CA Cancer J Clin 2019; 69: 88–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dodson T. The problem with P‐Hacking. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019; 77: 459–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]