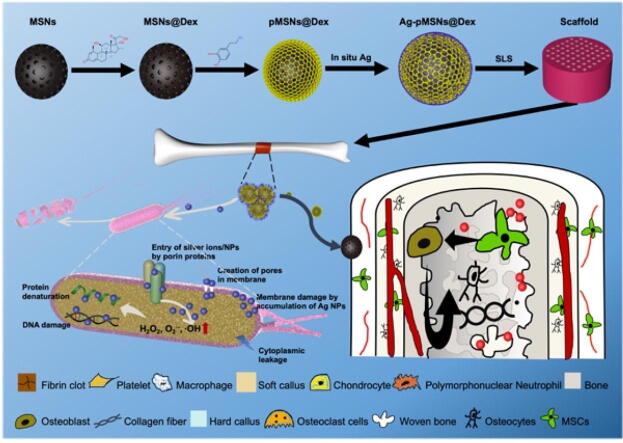

Graphical abstract

A spatiotemporal drug release system with dual function of antibiosis and bone regeneration was fabricated and introduced into personalized PLLA scaffold for osteomyelitis therapy.

Keywords: Osteomyelitis, Spatiotemporal drug release, Core/shell drug delivery system, Antibiosis, Bone regeneration, Selective laser sintering

Highlights

-

•

A core/shell drug delivery system with drugs loaded in different layers,

-

•

A spatiotemporal drug release system for osteomyelitis therapy,

-

•

Selective laser sintering for personalized bone scaffold fabrication.

Abstract

Introduction

Scaffolds loaded with antibacterial agents and osteogenic drugs are considered essential tools for repairing bone defects caused by osteomyelitis. However, the simultaneous release of two drugs leads to premature osteogenesis and subsequent sequestrum formation in the pathological situation of unthorough antibiosis.

Objectives

In this study, a spatiotemporal drug-release polydopamine-functionalized mesoporous silicon nanoparticle (MSN) core/shell drug delivery system loaded with antibacterial silver (Ag) nanoparticles and osteogenic dexamethasone (Dex) was constructed and introduced into a poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) scaffold for osteomyelitis therapy.

Methods

MSNs formed the inner core and were loaded with Dex through electrostatic adsorption (MSNs@Dex), and then polydopamine was used to seal the core through the self-assembly of dopamine as the outer shell (pMSNs@Dex). Ag nanoparticles were embedded in the polydopamine shell via an in situ growth technique. Finally, the Ag-pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles were introduced into PLLA scaffolds (Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA) constructed by selective laser sintering (SLS).

Results

The Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold released Ag+ at the 12th hour, followed by the release of Dex starting on the fifth day. The experiments verified that the scaffold had excellent antibacterial performance against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Moreover, the scaffold significantly enhanced the osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells.

Conclusion

The findings suggested that this spatiotemporal drug release scaffold had promising potential for osteomyelitis therapy.

Introduction

Osteomyelitis, a progressive inflammatory disease caused by pathogens, can develop into bone destruction and subsequent sequestrum formation [1]. The combination of antibacterial and surgical treatment is considered the “gold standard” for infectious bone defects caused by osteomyelitis [2]. Therefore, scaffolds with antibacterial and osteogenic abilities are essential in osteomyelitis therapy [3], [4]. However, osteogenic drugs directly doped into or mixed with scaffolds can be released prematurely. Generally, it takes at least 3–7 d to achieve antibiosis, as reported [5]. Before effective antibiosis, premature osteogenesis caused by the immediate release of osteogenic drugs, along with the inflammatory factors produced by the bacteria and the compression and obliteration of vessels around the infected area, leads to osteonecrosis and bone destruction [2]. The resulting avascular area subsequently turns into an ideal environment for pathogens due to its inaccessibility to inflammatory cells and antibiotic agents, aggravating bone infection and bone destruction and resulting in implantation failure. Therefore, it is desirable to introduce a programmable dual-drug delivery system into scaffolds for spatiotemporal drug release.

Among various drug carriers, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have tailorable mesoporous structures, high specific surface areas, and large pore volumes and can encapsulate various therapeutic agents through electrostatic adsorption, covalent conjugation, hydrogen bonding and ionic bonding [6]. Furthermore, silica has been widely used in cosmetics and food additives and is noted to be “generally recognized as safe” by the FDA [7], [8]. However, previous dual drug-loaded MSNs exhibited relatively low loading efficiency due to the competition of the two drugs for space in the drug delivery system, and the lack of significant difference in release between the drugs limited the effect of spatiotemporal release. One potential strategy is modifying the surface of MSNs by incorporating supramolecular self-assemblies to form a complex spatial structure after osteogenic drug loading, which can separate drugs into different layers and enable their release at different times [6].

Polydopamine, a mussel-inspired material, has attracted increasing attention due to its convenient functionalization, simple preparation process, strong adhesive property and good biocompatibility [9]. With o-benzoquinone, catechol, amine and other functional groups of dopamine, polydopamine can be formed on the surface of MSNs through the covalent oxidative polymerization and physical self-assembly of dopamine to form a tight cover [10]. Osteogenic drugs, such as Dex, can be loaded first and protected from premature release by the polydopamine cover immediately after administration. More importantly, a polydopamine layer exhibits reducing power due to the catechol quinone moieties and catechol radical species on the surface, which reduces metal ions into metal nanoparticles directly on top of the polydopamine layer [11]. The in situ growth of antibacterial metals such as Ag nanoparticles can be achieved by reaction with reductive hydroxy groups [12].

In this study, a spatiotemporal drug release system was constructed and introduced into scaffolds. Specifically, MSNs were used as the inner core and loaded with Dex through electrostatic adsorption (MSNs@Dex), and then polydopamine was formed through the self-assembly of dopamine as the outer shell (pMSNs@Dex) to seal the core. Ag nanoparticles were introduced into the polydopamine shell via an in situ growth technique (Ag-pMSNs@Dex). Finally, selective laser sintering (SLS) was used to construct Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffolds. The morphology, structure, and composition of Ag-pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles were systematically investigated. The effect of spatiotemporal drug release on composite scaffolds was also verified. The antibacterial performance against Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and the effect on the osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs were also evaluated. This main contribution of this study covers the following points: ● A core/shell drug delivery system with drugs loaded in different layers, ● A spatiotemporal drug release system for osteomyelitis therapy, ● Selective laser sintering for personalized bone scaffold fabrication.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of Ag-pMSNs@Dex

First, the MSNs were synthesized in a typical procedure as previously reported [13]. Ammonium fluoride (NH4F) (3.0 g) and cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) (1.82 g) were dissolved in 500 mL of ultrapure water at 80 °C with continuous and violent stirring. Next, 9 mL of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) was slowly and gently dripped into the solution followed by 2 h of stirring. After cooling at room temperature (RT), the solution with the synthesized nanoparticles was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 25 min and subsequently washed with deionized water and ethanol 3 times before vacuum drying. Finally, the solid materials were subjected to 6 h of calcination at 600 °C in air at a heating rate of 1 °C/min to eliminate the surfactant CTAB.

Then, 2 mg/mL Dex/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution was mixed with 5 mg/mL isopyknic MSNs followed by 12 h of stirring at RT. The resultant nanoparticles loaded with Dex (MSNs@Dex) were centrifuged for collection. After washing with TRIS buffer solution (10 mM TRIS, 0.17 M NaCl, pH = 7.4) 3 times, MSNs@Dex was dried at RT.

Next, 25 mL of 5 mg/mL dopamine solution was prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.5). The freshly prepared buffer was added to isometric MSNs@Dex (5 mg/mL, dissolved in ultrapure water) followed by slow stirring for 12 h in air at RT. The polydopamine-modified MSN@Dex powder changed from white to dark brown, indicating the formation of pMSNs@Dex.

Finally, a 0.04 mol/l silver ammonia solution was first formulated by adding ammonia solution dropwise into the silver nitrate solution with stirring until the newly formed precipitate was just dissolved. Then, pMSNs@Dex powder was added to the above solution followed by stirring for a 10 h reaction [14]. After centrifugation and washing with water 3 times, the in situ Ag-doped pMSNs@Dex nanocomposites (denoted as Ag-pMSNs@Dex) were obtained and dried at RT for further use.

Analysis and characterization of Ag-pMSNs@Dex

The morphologies of the nanoparticles were detected by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss, Germany) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI, USA). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR, Tian Jing Gan Dong SCI & TECH, China) spectroscopy was utilized to examine the chemical structure of the samples. A surface area and porosity analyzer (ASAP2460, Micromeritics, USA) was applied to record the nitrogen adsorption desorption isotherm of the nanoparticles. The Dex in the nanoparticles was analyzed using attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR–FTIR) controlled by OPUS software v7.0. The chemical constitution of the nanoparticles was measured by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo, USA) and solid state NMR (BRUKER AVANCE NEO 400WB, Germany).

Construction of composite scaffold

In our previous works, a PLLA scaffold with 4 wt% MSNs exhibited optimal overall performance as an artificial bone scaffold [15]. Therefore, a PLLA scaffold with 4 wt% Ag-pMSNs@Dex was constructed, and its biological performance was investigated [16], [17]. Specifically, 4 wt% Ag-pMSNs@Dex and 96 wt% PLLA powders were dispersed into anhydrous ethanol and stirred for 30 min under sonication. Then, the composite powders were retrieved through the process of straining, drying and grinding. Finally, three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds were built layer-by-layer by a self-developed SLS system. The laser conditions were set as follows: laser power, 7.5 W; scanning speed, 200 mm/s; spot diameter, 580 μm; scanning line space, 0.1 mm; powder bed temperature, 20 °C; and powder layer thickness, 0.2 mm. In addition, scaffolds with 4 wt% pMSNs and pure PLLA scaffolds were constructed for comparison [18]. We took photos of the composite scaffolds of Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA with a digital camera and observed their surfaces using SEM.

Drug release and degradation assay

The 3D printed scaffolds were first weighed and then palced in PBS (pH = 7.4) contained in vials. The vials were kept moving at 120 RPM and 37 °C on a shaker. At each time point (12 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, 7 d, 14 d and 21 d), a batch of samples was removed, washed with distilled water and dried for 30 min in a vacuum oven with dehydrating agent before weighing. The samples were then placed in fresh PBS until the next measurement. The samples were weighed weekly until 21 d. The percentage of weight loss, , was calculated as follows: , where and are the initial and subsequent time points for measuring dry weights, respectively. At the same time, 100 µL of the immersion solutions from each time point was saved for drug release measurement, and isometric PBS was added to keep the volume constant. The Dex concentration released by the scaffolds was quantitatively analyzed via a microplate reader (Varioskan™ LUX, Thermo, USA). The Ag+ concentration released from the scaffolds was quantified using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP–OES, Spectro Blue Sop, German).

Antibacterial activity

The scaffolds were constructed as wafers 7 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness, disinfected under ultraviolet light for 200 min and sterilized in 75 % ethanol steam overnight before cell seeding.

The antibacterial activities of the scaffolds against E. coli (representative of gram-negative bacteria; ATCC 25922) and S. aureus (representative of gram-positive bacteria; BNCC 186335) were evaluated [19]. First, the antibacterial ability of the scaffolds was examined using agar diffusion experiments. Briefly, E. coli or S. aureus (density, 1 × 106 CFU/mL) was cultured in a dish covered with agar culture medium at 37 °C, and the scaffold was placed at the center of the dish for 24 h. Images showing the area affected by the scaffold were taken using a digital camera.

We also implemented turbidimetric experiments to investigate the antibacterial properties of the scaffold. Specifically, we prepared E. coli and S. aureus suspensions (1 × 106 CFU/mL) with the scaffolds and cultured them for 24 h at 37 °C on a shaker operating at 200 rpm. After removing the scaffolds, we took photos of the suspension of bacteria to manually evaluate the degree of turbidity. We also quantified the turbidity by analyzing the optical density (OD) value of the suspension with a microplate reader (600 nm wavelength for E. coli, 450 nm wavelength for S. aureus). Simultaneously, the scaffold-bacterial compound was fixed using 2.5 % glutaraldehyde for 4 h at 4 °C followed by dehydration in a series of ethanol solutions with an increasing volume-to-volume ratio (30, 50, 70, 85, and 95 %) for 15 min. After coating with gold, the morphology of bacteria that grew on the scaffolds was observed using SEM. Furthermore, live/dead staining of the bacteria (DAPI/PI Double Stain Kit, Beyotime, China) was performed to assess the viability of bacterial populations as a function of the membrane integrity of the cell. After staining, all bacteria were blue at 364 nm and red at 535 nm under a fluorescence microscope.

Finally, crystal violet staining was performed to analyze the effect of the scaffolds on biofilm formation. Specifically, we prepared E. coli and S. aureus suspensions (1 × 106 CFU/mL) and cultured them in 24-well plates for 24 h at 37 °C, followed by the addition of scaffolds and culture for another 24 h. After the removal of the scaffolds and medium, 500 μL of absolute ethyl alcohol was added for 30 min to fix the biofilm. Then, the absolute ethanol was removed, and 1 % crystal violet was added and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The crystal violet solution was extracted and washed twice with PBS. Images of 24-well plates were taken using a digital camera. After this, 1 mL 60 % ethyl alcohol was added, and the 24-well plates were shaken for 2 h at 37 °C. Finally, the supernatant was tested at 570 nm with a microplate reader for the quantitation of biofilm.

Cell culture of mBMSCs

The mBMSCs (Procell Life Science & Technology Co., ltd., China) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin in a humidified 5 % CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The medium was replaced when necessary during culture. We only used 2–5 passages of mBMSCs in this study.

Proliferation of mBMSCs on the scaffold

The cell counting kit-8 assay (CCK-8, Beyotime, China) and Calcein-AM/PI Double Stain Kit (Beyotime, China) were used to assay the proliferation of BMSCs cultured on the scaffold as previously described [20]. The experiments were performed according to the explanatory memorandum. Furthermore, we observed the mBMSC morphologies on the surface of scaffolds with SEM. After rinsing with PBS 3 times, the samples were fixed with 2.5 % glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight and then subjected to gradient alcohol dehydration (85 % for 2 min; 95 % for 2 min; 99.99 % for 2 min; and 99.99 % for 2 min). After coating with gold, the morphologies of bacteria on the scaffolds were observed.

Osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs on the scaffold

On the 7th and 14th days, the ALP activity of cells cultured with different scaffolds was measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Jiancheng Co., China). Finally, the OD values were measured by a microplate reader at 520 nm, and the ALP activity was calculated as follows:

The degree of mineralization of mBMSCs was measured by alizarin red staining on the 7th and 21st days using 0.1 % alizarin red (pH 4.2, Soledad Bao Tech., China) and 10 % hexadecyl pyridinium chloride monohydrate (Sigma–Aldrich, USA). Finally, the staining effect was examined through optical microscopy, and the OD values of calcium were measured at 550 nm using an enzyme-labeling instrument.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n ≥ 3). All statistical analyses (one-way ANOVA) were performed in Prism (version 9.0.0). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Preparation and characterization of Ag-pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles

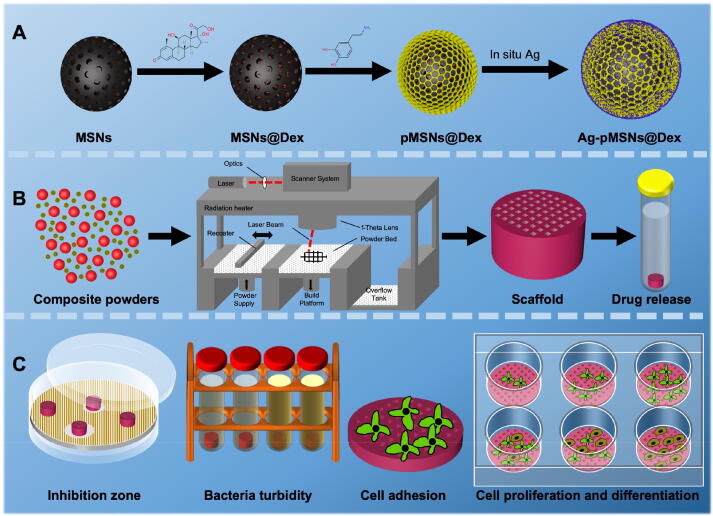

The preparation process was presented briefly in Fig. 1. We synthesized MSN nanoparticles as previously reported, and then loaded them with Dex [16]. After that, polydopamine was used to seal Dex through the self-assembly of dopamine, similar to the process described in other reports [21]. Finally, the outer surface of pMSNs@Dex was modified with Ag via in situ growth (Fig. 1A). The mixed powders of Ag-pMSNs@Dex and PLLA (quality ratio = 3 %:97 %) were printed into 3D scaffolds for the analysis of drug release and biological experiments of antibiosis and osteogenesis (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the overall study design. A. The synthesis of Ag-pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles. B. The construction of the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold. C. Experiments on antibacterial and osteogenic properties.

The morphology and structure of MSNs were shown in Fig. 2A. According to SEM, MSNs showed a relatively smooth surface. In addition, the isotherms of MSNs were between type Ⅳ and type Ⅴ according to the IUPAC classification, which are typical mesoporous structures [22]. Fig. 2B shows the FTIR spectra of MSNs, pMSNs, pMSNs@Dex and Ag-pMSNs@Dex. In the spectra, absorption of the Si-O-Si bond near 1130 cm−1 and silanol bending vibration at approximately 830 cm−1, were observed in all samples, as in other reports [23]. In addition, peaks of the hydroxide radical could be detected at approximately 1643 cm−1 due to incomplete TEOS hydrolyzation and adsorption of moisture in the air[24], [25]. For pMSNs@Dex and Ag-pMSNs@Dex, the typical absorption peaks at approximately 2937 cm−1 and 2854 cm−1 demonstrated the successful loading of Dex [26]. To further confirm the successful decoration of polydopamine and Ag particles on pMSNs@Dex, the chemical bonding states of Ag-pMSNs@Dex particles were measured by XPS. The peaks at approximately 400 eV and 371 eV contributed to the N1s peak of polydopamine and the Ag3d peak of metallic Ag (Fig. 2C)[27]. In detail, the Ag3d spectrum showed two peaks related to the Ag3d5/2 and Ag3d3/2 core energy levels (due to spin–orbit coupling) at 367.9 ± 0.1 eV and 374.1 ± 0.1 eV, respectively (Fig. 2D), as reported [28]. In addition, the shoulders observed on the lower energy side suggested the existence of a Ag + oxidic state (AgO, Ag2O), which was in good agreement with other studies [29].

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of Ag-pMSNs@Dex. A. N2 adsorption–desorption curve of MSNs. B. FTIR of nanoparticles, C. XPS spectra of Ag-pMSNs@Dex. D. High-resolution XPS spectra of Ag3d.

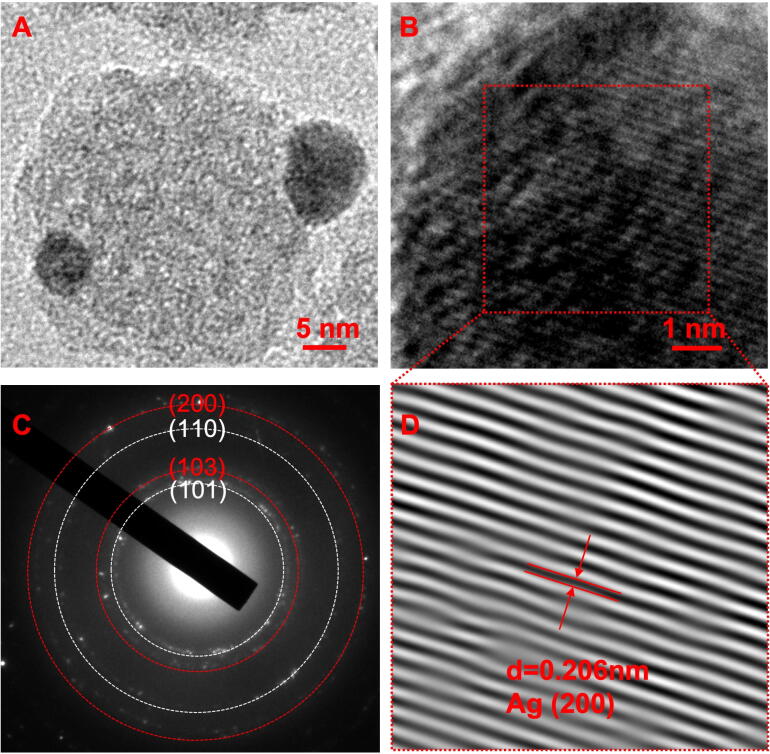

TEM was used for further verification of Ag nanoparticles on the surface of Ag-pMSNs@Dex. As shown in Fig. 3A, spherical particles decorated the surface of pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles. Furthermore, the crystalline interplanar spacing of the decorated nanoparticles was 0.206 nm, as displayed under high-resolution TEM, which was assigned to the (2 0 0) crystal plane of metallic Ag (Fig. 3B and D)[30]. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern recorded from the Ag nanoparticles is shown in the inset of Fig. 3C. The ring-like diffraction pattern indicated the crystalline nature of the Ag nanoparticles. Four rings arose due to reflections from the (1 0 1), (1 0 3), (1 1 0) and (2 0 0) lattice planes of silver [31]. In addition, solid-state NMR was used to further analyze the chemical structure of the nanoparticles. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the 1H peak of Dex was detected at ∼ 5 ppm in D2O and H2O solvent, which was consistent to others [32]. However, there were two peaks of MSNs at 1 and 5 ppm, which covered the 1H peak of Dex [33]. In addition, the solid-state NMR test was not suitable for the Ag-pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles due to the high electroconductibility of Ag.

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of Ag-pMSNs@Dex. TEM (A), high-resolution TEM (B), SEAD (C) and inverse fast Fourier transform (D) of Ag-pMSNs@Dex.

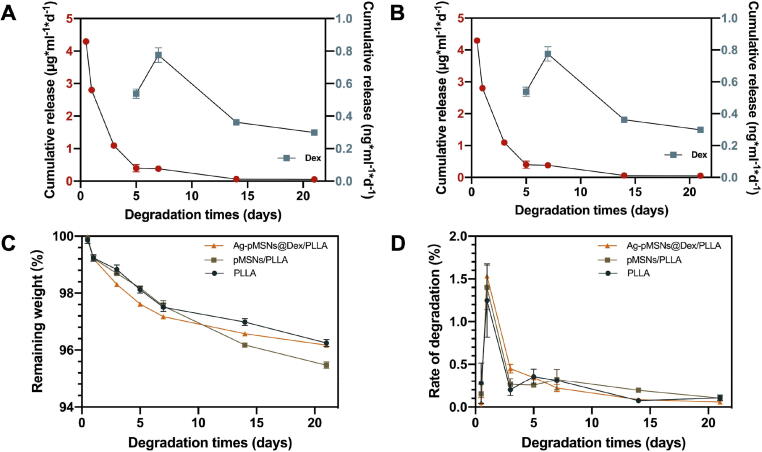

The spatiotemporal behavior of drug release

The concentrations of Ag+ and Dex released from the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold after immersion in deionized water for different periods were measured, and the results were presented in Fig. 4. The scaffolds exhibited a relatively high degeneration rate at the start, and then the degradation rate gradually stabilized at 0.05 ∼ 0.15 %/day, as shown in Fig. 4C. Finally, there was approximately 4 % weight loss with no significant difference among the different scaffolds (Fig. 4D). The release of Ag+ from the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold exhibited an initial burst release followed by a slow release during the subsequent 3 weeks (Fig. 4A and B). As previously reported, the release of Ag+ was a concerted oxidation process involving both dissolved oxygen and protons with oxygen reduction to superoxide anions through electronic effects, which further reacted with Ag to release Ag+ using the following formula: [34]. The electrons generated by the scaffolds might expedite the release of Ag+. With the core–shell structure of Ag-pMSNs@Dex, Ag+ could be released from the outer Ag nanoparticles during the initial periods of immersion, while the inner Dex adsorbed within MSNs could be protected by polydopamine for delayed release. Specifically, Dex release was not detected in the beginning, as expected, while approximately 11 % of the Dex was released from the composite scaffold on the 5th day followed by a constant release up to 72 % during the next 3 weeks. In short, the spatial position disparity of the outer Ag and inner Dex led to a temporal difference in release and consequently sequential antibiosis and osteogenesis, which could be beneficial to heal osteomyelitis.

Fig. 4.

Spatiotemporal drug release of the PLLA/Ag-pMSNs@Dex scaffold. Drug release (A) and degradation (C) of the PLLA/Ag-pMSNs@Dex scaffold and the corresponding drug release rate (B) and degradation rate (D).

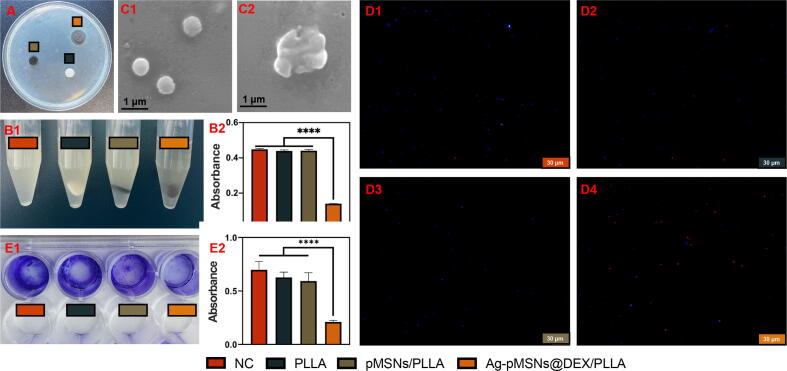

Antibacterial activity of the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold

Ag+ has been used as an antibacterial agent against E. coli and S. aureus because of its bacteriolytic effect and destruction of bacterial cell walls [35]. In this study, the antibacterial ability of the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold against S. aureus and E. coli. was evaluated. Samples with the same size PLLA scaffold, pMSNs/PLLA scaffold, Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold and a normal control with no scaffold were used for antibacterial experiments. The inhibition zones and turbidimetric test of these scaffolds against S. aureus were shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively. The Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold had a remarkable antibacterial annulus compared with the pMSNs@Dex/PLLA and pure PLLA scaffolds. Furthermore, the nutrient solution with the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold was almost totally clear and transparent, while the pMSNs@Dex/PLLA and pure PLLA scaffolds had turbidity similar to that of the normal control group (Fig. 5B2). As shown in Fig. 5C1, live S. aureus had a regular round shape and a smooth surface morphology, indicating its intact natural structure. In contrast, the dead bacteria were killed by the Ag + released from the Ag nanoparticles of the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold, so ruptured bacteria could be observed by SEM (Fig. 5C2). Furthermore, live/dead bacterial staining of S. aureus showed that there were many dead bacteria after soaking in the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold, while there were barely any dead bacteria in the other groups (Fig. 5D1-5D4). Peptidoglycan (PGN) is a major component of the bacterial cell wall, which helps provide overall strength to the bacteria, maintain the bacterial shape and protect the bacteria from osmotic lysis [36]. It is mainly single-layered in gram-negative bacteria and multilayered in gram-positive bacteria. Ag+ can inhibit the PGN cell wall of S. aureus by regulating PGN synthetic trans glycosylase and transpeptidase and enhancing the activity of PGN autolysins of amidases, as previously reported [37]. In addition, Ag+ can induce reactive oxygen species generation, such as O2–, H2O2, •OH, and OH–, and lead to oxidative stress in both E. coli and S. aureus [38]. Furthermore, Ag+ can bond with double and triple hydrogen bonds in DNA base pairs to form Ag+-coordinated complex formations, which will lead to DNA damage [39]. In summary, the Ag+ released from the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold demonstrated a distinguished broad-spectrum antibacterial effect. Finally, the formation of bacterial biofilms on scaffolds was tested through crystal violet staining (Fig. 5E1&E2). The group with the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold showed obviously reduced biofilm formation compared with the other groups. Biofilm formation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of chronic osteomyelitis [40]. The reduced biofilm formation revealed the possibility of treating severe infection.

Fig. 5.

The antibacterial properties of the scaffolds against S. aureus. A. Inhibition zone. B1&2. Bacterial turbidity and corresponding absorbance values. C1&2. SEM of normal S. aureus and debris of S. aureus. D1&2. Live/dead bacteria staining of different scaffolds. E1-4. Crystal violet staining of bacterial biofilm and corresponding absorbance values. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Analogously, the antibacterial activity against E. coli was also evaluated (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold also showed excellent antibacterial effects against gram-positive E. coli. Ag+ inactivates the PGN transpeptidase synthetic enzyme endopeptidase and enhances the activities of PGN hydrolases and autolysins of amidase, peptidase, and carboxypeptidase, thus inhibiting PGN elongation and ultimately causing bacteriolysis and destruction of the E. coli cell wall [41].

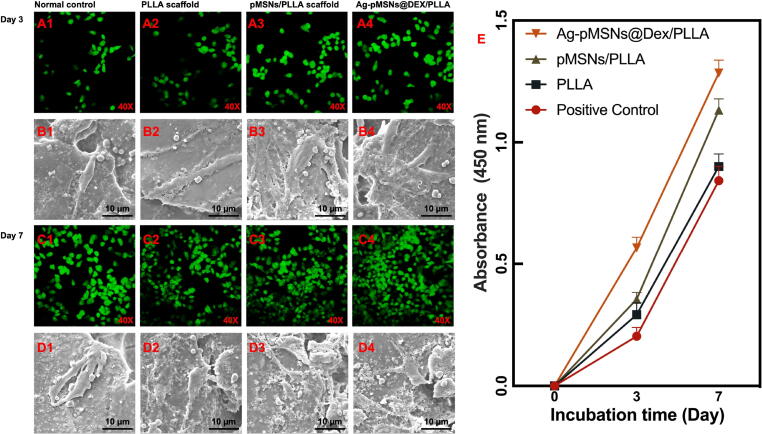

Osteogenesis of the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold

To investigate the cell viability of PLLA, pMSNs/PLLA and Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffolds, mBMSCs were cultured on the scaffolds, and the cell viability was evaluated through live/dead cell staining and standard CCK-8 assay on the 3rd and 7th days. In addition, medium with no scaffold was used as a normal control. As shown in Fig. 6, green and red indicated live and dead cells, respectively. There were no obvious dead cells on any of the scaffolds, indicating no apparent cytotoxicity of the scaffolds. Furthermore, the amount of mBMSCs on the 7th day was significantly increased compared with that on the 3rd day, meaning that the scaffolds were beneficial to cell proliferation with outstanding cytocompatibility. More importantly, more cells on the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold were observed than on the other scaffolds on the same day, while the pMSNs/PLLA scaffold also exhibited higher viability than the normal control and PLLA scaffold. Thus, pMSNs and the drug Dex may have the potential to promote the proliferation of mBMSCs. In addition, the morphologies of mBMSCs on scaffolds are shown in Fig. 6. The cells showed a spindle-shaped morphology with a few thin pseudopodia on the surface of the scaffolds on the 3rd day. With prolonged incubation, mBMSCs grown on the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold had more filopodia-like extensions on the 7th day than those grown on other scaffolds [42].

Fig. 6.

Cell proliferation and adhesion properties of mBMSCs on different scaffolds. Live/dead cell staining (A1 - A4, C1 - C4) and cell morphologies (B1 - B4, D1 - D4) of mBMSCs on different scaffolds and the corresponding standard CCK-8 assay (E) on day 3 and day 7.

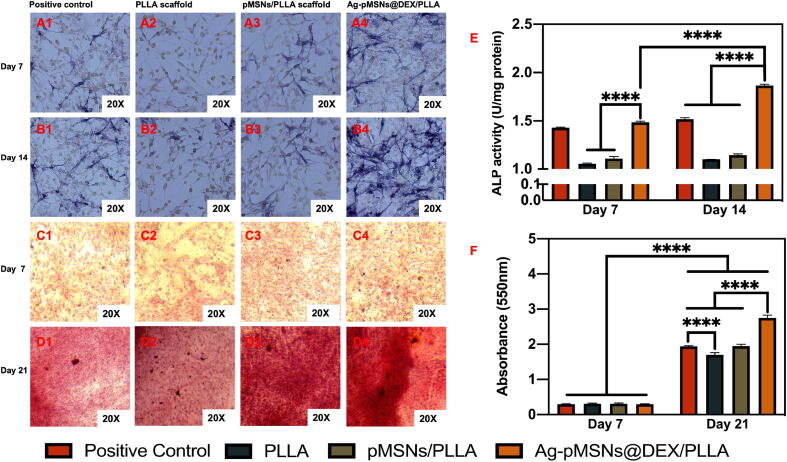

ALP activity is an early marker of the osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs [43]. In addition, many studies have shown that Dex can induce osteogenic differentiation and bone formation of mBMSCs as the earliest and most readily available osteogenic inducer [44], [45], [46]. Herein, the effect of Dex released from the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold on mBMSCs was investigated, and pure PLLA and pMSNs/PLLA scaffolds were used as controls (Fig. 7). Moreover, the medium with 10 nM Dex solution was studied as a positive control. The ALP activity of mBMSCs on the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold and positive control was significantly stronger than that on the PLLA scaffold and pMSNs/PLLA scaffold on the 7th day, suggesting that the introduction of the nanoparticles could upregulate ALP in the early stage (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the ALP activity of mBMSCs grown on the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold was significantly stronger than that of mBMSCs cocultured with Dex solution on the 14th day, meaning that the controlled-released nanoparticles were more effective in the osteogenesis of mBMSCs than the Dex solution.

Fig. 7.

Osteogenesis experiments of mBMSCs on different scaffolds. ALP staining (A1 - A4, B1 - B4) on Day 7 and Day 14 and Alizarin red staining (C1 - C4, D1 - D4) on Day 7 and Day 21 of mBMSCs on different scaffolds and the corresponding quantitative analysis (E, F). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The formation of calcium nodules is a crucial target of mineralized matrix formation. In this study, we used Alizarin red S staining to examine calcium deposition, and the extent of calcium nodules was quantified by dissolving and measuring the OD value at 550 nm, as shown in Fig. 7B. When mBMSCs were cultured for 7 d, almost no calcium deposition was stained with red spots on any of the scaffolds, which was consistent with other reports, as osteogenic differentiation had proceeded halfway or the differential osteoblast was immature and not in the matrix mineralization period [47], [48], [49]. After culturing for 21 d, the red color intensity of all scaffolds was significantly stronger than that 2 weeks prior, indicating that mBMSCs differentiated from a rapid proliferation period to a matrix mineralization period. Moreover, the concentration of Ca2+ for the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold was significantly higher than that for the other three groups, meaning that the drug-release system was effective in osteogenesis. In addition, the concentration of Ca2+ on the pure PLLA and pMSN/PLLA scaffolds on the 21st day was higher than that on the 7th day. This was probably because PLLA and MSNs could promote mineral deposits and bone formation, as reported in other studies [50], [51]. These results indicated that Dex released from the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold could induce matrix mineralization, indicating the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

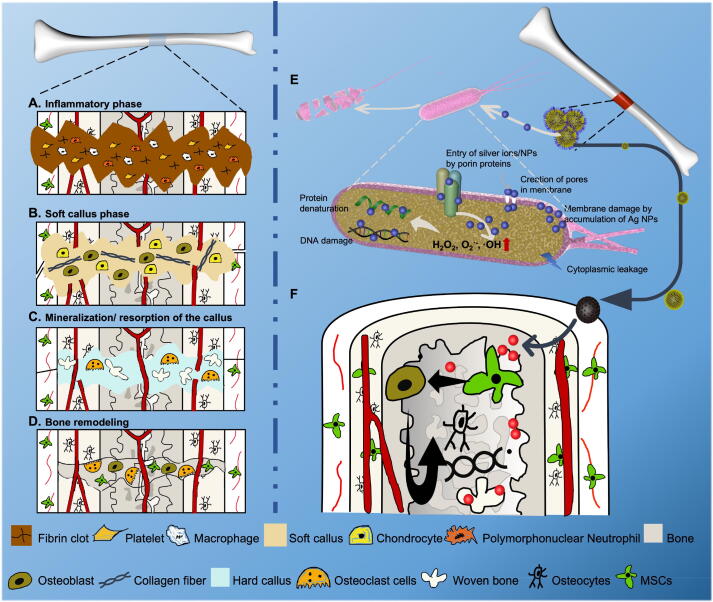

Discussion

Osteomyelitis substantially affects patients’ quality of life and is frustrating for both patients and their doctors [52]. Generally, the treatment of osteomyelitis can be divided into four or five steps, involving antibiotic therapy, debridement, bone grafting and even bone transplantation [2]. The long course of disease causes great pain and financial burden. However, it is difficult to achieve high success rates of antimicrobial therapy in osteomyelitis due to the physiological and anatomical characteristics of bone, resulting in repeated infection and progressive bone destruction. The four sequential stages of bone regeneration in physiological conditions are well-known, including the inflammatory phase, soft callus formation, mineralization/resorption of the callus and bone remodeling (Fig. 8A-8D) [53]. It is crucial to create a sterile microenvironment in the inflammatory phase and to provide a rich blood supply in the soft callus formation phase for osteogenic factors. However, in the case of stubborn infection in osteomyelitis patients, the inflammatory phase is not fully effective and overlaps with other phases, which eventually leads to sequestrum formation and bone destruction. Therefore, it is desirable to design a novel product that can clear infections efficaciously before bone regeneration, reduce the number of operations, and shorten the course of treatment.

Fig. 8.

Schematic illustration of the spatiotemporal effects of antibiosis and bone regeneration scaffolds in infected bone defects. A-D. The four phases of bone regeneration. E-F. The spatiotemporal effects of antibiosis and bone regeneration.

In this study, a spatiotemporal drug-release polydopamine-functionalized mesoporous silicon nanoparticle core/shell drug delivery system loaded with antibacterial silver nanoparticles and osteogenic dexamethasone was constructed and then introduced into a poly-l-lactic acid scaffold for osteomyelitis therapy. Initially, Ag+ and Ag nanoparticles could enter the cell through porin proteins or form membrane pores, which could result in membrane damage and cytoplasmic leakage. Furthermore, Ag+ and Ag nanoparticles could promote the production of ROS, such as H2O2, O2–, and OH, and cause protein denaturation and DNA damage (Fig. 8E). In addition, the subsequently released Dex may stimulate BMSC osteoblastogenesis and osteoblast differentiation, promoting bone regeneration after infection management (Fig. 8F). Therefore, this spatiotemporal drug release scaffold could achieve early antibiosis and subsequent bone regeneration, which has potential in one-stage operation for osteomyelitis treatment.

Various scaffolds were fabricated by different methods, such as implant coating and doping, as reported in other studies that focused on different aspects of osteomyelitis (Supplementary Table. 1). Some scaffolds possessed only the antibacterial capacity, which neglected the osteogenesis of scaffolds and limited the treatment of severe osteomyelitis and bone defects. Ji-Hyun Lee and his team developed a rifampicin-loaded polycaprolactone scaffold that showed growth inhibitory activity against E. coli and S. aureus [54]. However, the osteogenic property of this scaffold was not further studied. Moreover, the combination of a surface modified metallic implant with a polymer nanocomposite scaffold was explored in several studies. Through anchoring by treatment with dopamine, Nancy David and Rajendran Nallaiyan coated titanium implants with antimicrobial vancomycin [55]. Although this scaffold had a substantial antibacterial effect against S. aureus because of the quick release of vancomycin, it required a second surgery to be removed. Some of the scaffolds achieved the release of antibacterial and osteogenic agents at the same time. However, in the case of complex infections, scaffolds with such simultaneous release could not lower sequestrum production. In contract, our Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffolds are loaded with different drugs in the inner and outer layers of the core/shell construction. Based on these results, antimicrobial Ag could be released at first as drug-loaded nanoparticles degrade, followed by the release of Dex. With this 5-day time window, Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffolds may sequentially promote antibiosis in the inflammatory phase and osteogenesis at other phases.

Although a range of in vitro experiments have been used to verify the antibacterial and osteogenic properties, and more importantly, the spatiotemporal effect of drug release, there are still some details that need to be improved, such as the dynamics of drug release and in vivo verification of the curative effect. In future studies, we may be able to modulate the time window of Dex release by adjusting the thickness of polydopamine to achieve better spatiotemporal release effect. And the controlled release of both medications may also be an option. Furthermore, we would like to perform in vivo experiments to work toward clinical practicability.

Conclusion

In this study, Ag-pMSNs@Dex nanoparticles were introduced into PLLA scaffolds via SLS for osteomyelitis therapy. The drug release test of this scaffold showed the spatiotemporally separated release of Ag and Dex, which was of prime importance for the one-step treatment of osteomyelitis. A series of in vitro antibacterial experiments indicated that the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold had a remarkable sterilizing effect against both gram-positive S. aureus and gram-negative E. coli. In addition, the cell viability study showed that the composite scaffolds possessed good cytocompatibility to support the proliferation of mBMSCs. Furthermore, the Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA scaffold presented significantly enhanced osteogenic differentiation compared with the free Dex solution and the PLLA and pMSNs/PLLA scaffolds. In brief, this study provided a novel and convenient method for the treatment of osteomyelitis, and the prepared 3D Ag-pMSNs@Dex/PLLA composite scaffold has great potential for the spatiotemporal effect of antibiosis and osteogenesis.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

All the authors listed in the paper have read the paper and agreed to submit it for publication. This paper is new. Neither the entire paper nor any part of its content has been published or has been accepted elsewhere. It is not being submitted to any other journal. The study of animals, patients or volunteers is not involved in this study. The cells and bacterial were purchased from qualified companies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (51935014, 52165043, 52105352, 82072084, 81871498); Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2020ACB214004, 20202BAB214011); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A030413428); Shenzhen Fundamental Research Program (JCYJ20190808122003692); the Provincial Key R & D Projects of Jiangxi (20201BBE51012); and the Project of State Key Laboratory of High Performance Complex Manufacturing.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.01.019.

Contributor Information

Cijun Shuai, Email: shuai@csu.edu.cn.

Sheng Yang, Email: tobyys2000@aliyun.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Panteli M., Giannoudis P.V. Chronic osteomyelitis: what the surgeon needs to know. EFORT Open Rev. 2016;1:128–135. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lew D.P., Waldvogel F.A. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369–379. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng P., Kong Y., Liu M., Peng S., Shuai C. Dispersion strategies for low-dimensional nanomaterials and their application in biopolymer implants. Materials Today. Nano. 2021;15 doi: 10.1016/j.mtnano.2021.100127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qi F., Zeng Z., Yao J., Cai W., Zhao Z., Peng S., et al. Constructing core-shell structured BaTiO3@carbon boosts piezoelectric activity and cell response of polymer scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;126 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.R, Schnettler, K, Emara, D, Rimashevskij, R, Diap, A, Emara, J, Franke, et al. in Basic Techniques for Extremity Reconstruction: External Fixator Applications According to Ilizarov Principles (eds Mehmet Çakmak et al.) 605-628 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

- 6.Kankala R.K., Han Y.H., Na J., Lee C.H., Sun Z., Wang S.B., et al. Nanoarchitectured structure and surface biofunctionality of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2020;32:e1907035. doi: 10.1002/adma.201907035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang F., Li L., Chen D. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, biocompatibility and drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1504–1534. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Bennett A.E. Synthesis, toxicology and potential of ordered mesoporous materials in nanomedicine. Nanomed (Lond) 2011;6:867–877. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng W., Zeng X., Chen H., Li Z., Zeng W., Mei L., et al. Versatile polydopamine platforms: synthesis and promising applications for surface modification and advanced nanomedicine. ACS Nano. 2019;13:8537–8565. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b04436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song H., Wang Z., Yang J., Jia X., Zhang Z. Facile synthesis of copper/polydopamine functionalized graphene oxide nanocomposites with enhanced tribological performance. Chem Eng J. 2017;324:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H.A., Park E., Lee H. Polydopamine and its derivative surface chemistry in material science: a focused review for studies at KAIST. Adv Mater. 2020;32:e1907505. doi: 10.1002/adma.201907505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Q., Chen J., Liu M., Huang H., Zhang X., Wei Y. Polydopamine-based functional materials and their applications in energy, environmental, and catalytic fields: State-of-the-art review. Chem Eng J. 2020;387 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z., Han S., Shi M., Liu G., Chen Z., Chang J., et al. Immunomodulatory effects of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on osteogenesis: from nanoimmunotoxicity to nanoimmunotherapy. Appl Mater Today. 2018;10:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2017.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao C., Yao M., Peng S., Tan W., Shuai C. Pre-oxidation induced in situ interface strengthening in biodegradable Zn/nano-SiC composites prepared by selective laser melting. J Adv Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian G., Zhang L., Liu X., Wu S., Peng S., Shuai C. Silver-doped bioglass modified scaffolds: a sustained antibacterial efficacy. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;129 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian G., Zhang L., Wang G., Zhao Z., Peng S., Shuai C. 3D Printed Zn-doped Mesoporous Silica-incorporated Poly-L-lactic Acid Scaffolds for Bone Repair. Int J Bioprint. 2021;7:346. doi: 10.18063/ijb.v7i2.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y., Cheng Y., Yang M., Qian G., Peng S., Qi F., et al. Semi-coherent interface strengthens graphene/zinc scaffolds. Materials Today Nano. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.mtnano.2021.100163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y., Cai G., Yang M., Wang D., Peng S., Liu Z., et al. Laser Additively Manufactured Iron-Based Biocomposite: Microstructure, Degradation, and In Vitro Cell Behavior. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.783821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.L, Yu, T, He, j, yao, W, Xu, S, Peng, P, Feng, et al. Cu ions and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide loaded into montmorillonite: a synergistic antibacterial system for bone scaffold. Materials Chemistry Frontiers 2021 10.1039/D1QM01278A.

- 20.Qiu K., Chen B., Nie W., Zhou X., Feng W., Wang W., et al. Electrophoretic Deposition of Dexamethasone-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles onto Poly(L-Lactic Acid)/Poly(ε-Caprolactone) composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:4137–4148. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b11879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J.C., Chen Y., Li Y.H., Yin X.B. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided multi-drug chemotherapy and photothermal synergistic therapy with pH and NIR-stimulation release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:22278–22288. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b06105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thommes M., Kaneko K., Neimark A.V., Olivier J.P., Rodriguez-Reinoso F., Rouquerol J., et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl Chem. 2015;87:1051–1069. doi: 10.1515/pac-2014-1117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H., Zheng D., Liu J., Kuang Y., Li Q., Zhang M., et al. pH-Sensitive drug delivery system based on modified dextrin coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;85:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nairi V., Medda S., Piludu M., Casula M.F., Vallet-Regì M., Monduzzi M., et al. Interactions between bovine serum albumin and mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized with biopolymers. Chem Eng J. 2018;340:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croissant J.G., Zhang D., Alsaiari S., Lu J., Deng L., Tamanoi F., et al. Protein-gold clusters-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for high drug loading, autonomous gemcitabine/doxorubicin co-delivery, and in-vivo tumor imaging. J Control Release. 2016;229:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aljarah A.K., Hameed I.H., Hadi M.Y. Evaluation and Study of Recrystellization on Polymorph of Dexamethasone by Using GC-MS and FT-IR Spectroscopy. Indian. J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2019:13. doi: 10.5958/0973-9130.2019.00072.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rella S., Mazzotta E., Caroli A., De Luca M., Bucci C., Malitesta C. Investigation of polydopamine coatings by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy as an effective tool for improving biomolecule conjugation. Appl Surf Sci. 2018;447:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.03.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parashar P.K., Komarala V.K. Engineered optical properties of silver-aluminum alloy nanoparticles embedded in SiON matrix for maximizing light confinement in plasmonic silicon solar cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12520. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12826-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuai C., Liu G., Yang Y., Qi F., Peng S., Yang W., et al. A strawberry-like Ag-decorated barium titanate enhances piezoelectric and antibacterial activities of polymer scaffold. Nano Energy. 2020;74 doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan N.P.B., Lee C.H., Li P. Green synthesis of smart metal/polymer nanocomposite particles and their tuneable catalytic activities. Polymers (Basel) 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/polym8040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A, Fernández, Zimbone, Boutinguiza, Val, Riveiro, Privitera et al. Synthesis and Deposition of Ag Nanoparticles by Combining Laser Ablation and Electrophoretic Deposition Techniques. Coatings (2019) 9, doi:10.3390/coatings9090571.

- 32.A, Midelfart, A, Dybdahl, N, MÜLler, B, Sitter, I. S, Gribbestad, J, Krane, Dexamethasone and Dexamethasone Phosphate Detected by1H and19F NMR Spectroscopy in the Aqueous Humour. Experimental Eye Research 1998 66, 327-337, 10.1006/exer.1997.0429. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Rapp J.L., Huang Y., Natella M., Cai Y., Lin V.S., Pruski M. A solid-state NMR investigation of the structure of mesoporous silica nanoparticle supported rhodium catalysts. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2009;35:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Q., Tan L., Lang Q., Ke X., Bai L., Guo K., et al. Plasmonic molybdenum oxide nanosheets supported silver nanocubes for enhanced near-infrared antibacterial activity: synergism of photothermal effect, silver release and photocatalytic reactions. Appl Catal B. 2018;224:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishida T. Antibacterial mechanism of Ag+ ions for bacteriolyses of bacterial cell walls via peptidoglycan autolysins, and DNA damages. MOJ. Toxicology. 2018;4 doi: 10.15406/mojt.2018.04.00125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf A.J., Underhill D.M. Peptidoglycan recognition by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:243–254. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behra R., Sigg L., Clift M.J., Herzog F., Minghetti M., Johnston B., et al. Bioavailability of silver nanoparticles and ions: from a chemical and biochemical perspective. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10:20130396. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashyap D.R., Rompca A., Gaballa A., Helmann J.D., Chan J., Chang C.J., et al. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins kill bacteria by inducing oxidative, thiol, and metal stress. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004280. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang A.H., Hakoshima T., van der Marel G., van Boom J.H., Rich A. AT base pairs are less stable than GC base pairs in Z-DNA: the crystal structure of d(m5CGTAm 5CG) Cell. 1984;37:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.E. A, Masters, R. P, Trombetta, K. L, de Mesy Bentley, B. F, Boyce, A. L, Gill, S. R, Gill, et al. Evolving concepts in bone infection: redefining “biofilm”, “acute vs. chronic osteomyelitis”, “the immune proteome” and “local antibiotic therapy”. Bone Res (2019) 7, 20, doi:10.1038/s41413-019-0061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Li X.Z., Nikaido H., Williams K.E. Silver-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli display active efflux of Ag+ and are deficient in porins. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6127–6132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6127-6132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahboudi H., Kazemi B., Soleimani M., Hanaee-Ahvaz H., Ghanbarian H., Bandehpour M., et al. Enhanced chondrogenesis of human bone marrow mesenchymal Stem Cell (BMSC) on nanofiber-based polyethersulfone (PES) scaffold. Gene. 2018;643:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birmingham E., Niebur G.L., McHugh P.E., Shaw G., Barry F.P., McNamara L.M. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells is regulated by osteocyte and osteoblast cells in a simplified bone niche. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;23:13–27. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v023a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Q., Shou P., Zheng C., Jiang M., Cao G., Yang Q., et al. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1128–1139. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou X., Feng W., Qiu K., Chen L., Wang W., Nie W., et al. BMP-2 derived peptide and dexamethasone incorporated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for enhanced osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:15777–15789. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b02636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun Z., Wu F., Gao H., Cui K., Xian M., Zhong J., et al. A dexamethasone-eluting porous scaffold for bone regeneration fabricated by selective laser sintering. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020;3:8739–8747. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c01126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon J.A., Tye C.E., Sampaio A.V., Underhill T.M., Hunter G.K., Goldberg H.A. Bone sialoprotein expression enhances osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization in vitro. Bone. 2007;41:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wischmann J., Lenze F., Thiel A., Bookbinder S., Querido W., Schmidt O., et al. Matrix mineralization controls gene expression in osteoblastic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2018;372:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Y., Jiang Y., Liu Q., Liu C.Z. lncRNA H19 promotes matrix mineralization through up-regulating IGF1 by sponging miR-185-5p in osteoblasts. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:48. doi: 10.1186/s12860-019-0230-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J., Chu B., Hsiao B.S. Mineralization of hydroxyapatite in electrospun nanofibrous poly(L-lactic acid) scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:307–317. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mora-Raimundo P., Lozano D., Benito M., Mulero F., Manzano M., Vallet-Regi M. Osteoporosis remission and new bone formation with mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2021:e2101107. doi: 10.1002/advs.202101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kavanagh N., Ryan E.J., Widaa A., Sexton G., Fennell J., O'Rourke S., et al. Staphylococcal osteomyelitis: disease progression, treatment challenges, and future directions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31 doi: 10.1128/CMR.00084-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martino M.M., Briquez P.S., Maruyama K., Hubbell J.A. Extracellular matrix-inspired growth factor delivery systems for bone regeneration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;94:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J.H., Baik J.M., Yu Y.S., Kim J.H., Ahn C.B., Son K.H., et al. Development of a heat labile antibiotic eluting 3D printed scaffold for the treatment of osteomyelitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7554. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64573-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.David N., Nallaiyan R. Biologically anchored chitosan/gelatin-SrHAP scaffold fabricated on Titanium against chronic osteomyelitis infection. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;110:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.