Abstract

Gastric glomus tumours (GGTs) are rare predominantly benign, mesenchymal neoplasms that commonly arise from the muscularis or submucosa of the gastric antrum and account for <1% of gastrointestinal soft-tissue tumours. Historically, GGT has been difficult to diagnose preoperatively due to the lack of unique clinical, endoscopic and CT features. We present a case of an incidentally identified GGT in an asymptomatic man that was initially considered a neuroendocrine tumour (NET) by preoperative fine-needle aspiration biopsy with focal synaptophysin reactivity. An elective robotic distal gastrectomy and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. Postoperative review by pathology confirmed the diagnosis of GGT. GGTs should be considered by morphology as a differential diagnosis of gastric NET on cytology biopsy, especially if there is focal synaptophysin reactivity. Additional staining for SMA and BRAF, if atypical/malignant, can help with this distinction. Providers should be aware of the biological behaviour and treatment of GGTs.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Stomach and duodenum, Pathology, Surgical oncology

Background

Glomus tumours (GTs) are rare, benign neoplasms of mesenchymal origin that originate from the modified smooth muscle of the glomus body and account for <1% of gastrointestinal (GI) soft-tissue tumours. The glomus body is a specialised arteriovenous connection composed of an afferent arteriole, the Sucquet-Hoyer canals, an efferent venule and an intraglomerular capsule.1 GTs arise from the Sucquet-Hoyer canals and are classified into three subcategories (solid glomus tumour, glomangioma and glomangiomyoma) based on the morphological prevalence of glomus cells, vasculature and smooth muscle cells.2 The primary function of the glomus body is thought to be thermoregulation. In most cases, GTs are small, benign neoplasms found in peripheral subungual or deep soft-tissue extremity locations, but atypical and malignant GTs have been reported.3–6 Although rare, GT can also arise in the trachea, lungs, pancreas, liver, genitourinary and GI tracts.6

In the GI tract, the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum is the most common site for GT.6–9 Gastric glomus tumours (GGTs) typically arise from the gastric submucosa or muscularis and project either into the lumen or serosa.3–5 7 GGTs most commonly develop in the fifth decade of life and occur more frequently in women.7 8 10 11 These present asymptomatically or with a variety of symptoms, including abdominal pain/discomfort, GI bleeding, melena or outlet obstruction.7 8 11 CT and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) are the primary initial diagnostic modalities used to evaluate gastric tumours.

These modalities are rarely sufficient to make a preoperative diagnosis of GGTs. In addition, accurate diagnosis of GGTs is limited by the overlapping features shared with other gastric submucosal tumours.9 12 13 Therefore, almost all GGTs are diagnosed postoperatively from resected pathology specimens using immunohistochemistry.7 11 14 GI stromal tumours (GISTs) are the most common GGT misdiagnosis.10 15 16

Here, a case of GGT in an asymptomatic man is presented that was initially considered a gastric neuroendocrine tumour (GNET) by FNA cytology and focal synaptophysin reactivity. The GGT was resected via robotic distal gastrectomy with regional lymphadenectomy and reconstructed with a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, and later confirmed to be GGT by morphological and phenotypic evaluation.

Case presentation

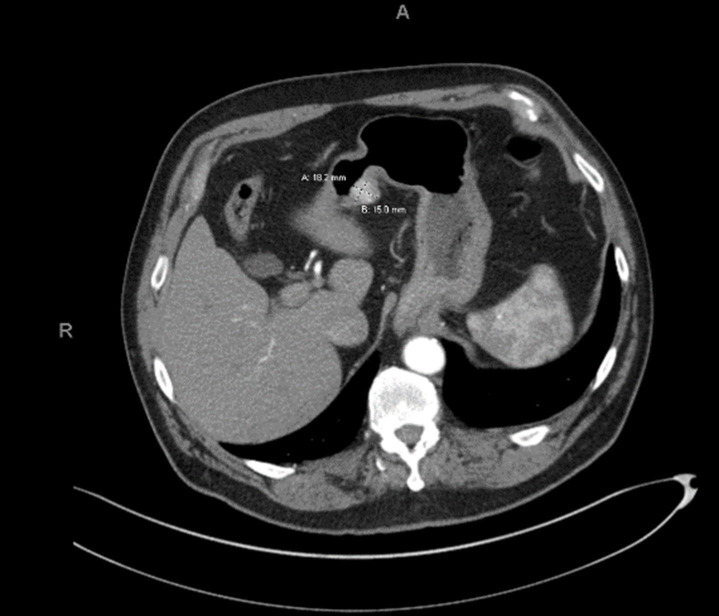

The patient was a male who presented with a possible ureteropelvic junction obstruction. A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen demonstrated a 1.8×1.5 cm enhancing hypervascular mass on the lesser curvature of the antrum of the stomach with no mesenteric, perigastric or retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (figure 1). At the time of the incidental diagnosis, the patient denied any GI symptoms. Physical examination demonstrated a soft, non-tender and non-distended abdomen without a palpable mass or concerning lymphadenopathy.

Figure 1.

CT of GGT case. GGT, gastric glomus tumour.

Investigations

The patient was referred to gastroenterology, and an upper endoscopy was performed. Endoscopic full-thickness resection was considered but decided against due to the risk of incomplete resection. EUS demonstrated a round, heterogeneous subepithelial lesion measuring 2 cm in maximal thickness with a diameter of 1.8 cm (figure 2). The lesion appeared to originate from the submucosa and extend towards the muscularis propria. The endosonographic borders were well defined.

Figure 2.

Endoscope of GGT case. GGT, gastric glomus tumour.

Endoscopic FNA was performed, which demonstrated ovoid epithelioid cells without significant atypia, mitoses or necrosis (figure 3). The aspirate smear was found to be suggestive of a low-grade lesion favouring a well-differentiated NET. The possibility of a type III GNET was considered as there was no history of atrophic gastritis and the gastrin level was normal. The patient was referred to surgical oncology for a discussion regarding an elective resection of the lesion. Blood chemistry and a complete blood count were obtained preoperatively, which revealed the patient to be mildly leukocytic, hyperglycaemic and thrombocytopenic, but non-anaemic. All other lab values were within normal ranges.

Figure 3.

FNA biopsy with cytology of dark round blue cells, round cells with dispersed chromatin on histology and synaptophysin weak, dot-like Golgi-appearing reactivity, unusual for GT. FNA, fine-needle aspirate; GT, glomus tumour.

Differential diagnosis

On initial finding of the gastric mass on CT, prior to endoscopic evaluation and FNA, the finding of a small, submucosal-muscularis mass with hyperenhancement/hypervascularity is most suggestive of glomus tumour, followed by GI stromal tumour, inflammatory fibrous polyp, carcinoid tumour, varices and less likely metastases (such as from extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma) or gastric adenocarcinoma. The final diagnosis was determined by histopathological findings, as mentioned in the discussion below.

Treatment

The patient underwent a robotic distal gastrectomy, regional lymphadenectomy and Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. The procedure progressed appropriately with no intraoperative complications. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day four. On gross examination, a well-circumscribed, submucosal, tan-white, haemorrhagic mass measuring 1.8×1.6×1.4 cm was found. The mass was confined within the gastric wall and did not extend through the mucosa or serosa. Examination of the mucosa and serosa revealed no abnormalities.

Outcome and follow-up

Histopathological findings demonstrated GGT with prominent vascularity and glomangioma; the tumour was embedded in the muscularis mucosa and composed of ovoid cells exhibiting clear cytoplasm with distinctive cytoplasmic borders (figure 4). The tumour displayed low mitotic activity and no necrosis. Immunohistochemistry revealed tumour cell positivity for SMA and focally weak dot-like Golgi positivity for synaptophysin with MIB1 less than 1%. The tumour was negative for chromogranin, CD56, keratin, CD34, CD117 and DOG1. The benign nature of the tumour was confirmed by a negative BRAF test. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 4 and is more than 1-year follow-up with no evidence of recurrent disease.

Figure 4.

Histopathology and SMA immunostain of gastric glomus tumour resection. H&E low power with submucosal (gastric mucosa to far left of picture) gastric glomus tumour (left) with prominent pericytoid vasculature (glomangioma), higher magnification of round to ovoid cells with cytoplasmic clearing, ‘fried-egg’ appearance (middle), SMA immunostain positivity (right).

Discussion

GIST and GNET are two differential considerations that have been reported in the literature for GGT; however, misdiagnosis as NET is far less common.10 15 16 Although the greatest incidence of NETs is the GI tract, involvement of the stomach is relatively uncommon and only accounts for 8.7% of all NETs.17 The annual occurrence of GNETs is 1–2 cases/1 000 000 persons.17 Together, the rarity of both GGTs and GNETs creates a uniquely difficult diagnosis when their overlapping morphological and phenotypic findings on FNA biopsy are considered.

Preoperative diagnosis of GGT is challenging due to the lack of distinct clinical features and non-specific endoscopic and CT findings. Symptoms of GGT include fatigue, epigastric pain, GI bleeding, gastric ulceration with melena, outlet obstruction and nausea/vomiting, which are all common to several other gastric pathologies.7 8 11 CT scans depict GGT as a round, endophytic, well-circumscribed mass with homogeneous density, similar to several other gastric tumours, including GIST, schwannomas, haemangiomas and GNET.13 18 19 Endoscopic findings commonly demonstrate slightly hypoechoic, circumscribed masses with an internal heterogeneous echo.12 EUS is useful in determining the layer of tumour origin but fails to be able to robustly differentiate GGT from other gastric lesions. The radiologic prominence of feeder vasculature can be a helpful identifier of perivascular tumours on pathology.20

GGTs are most reliably diagnosed postoperatively using cytopathology and immunohistochemistry. Endoscopic-guided FNA has been successfully used to diagnose GGTs preoperatively, yet this diagnostic modality is not reliable due to the deep location of most GGTs.5 10 Histologically, GGTs are composed of nests of well-defined glomus cells with centrally located oval nuclei and delicate chromatin surrounded by bundles of gastric smooth muscle and fibrous tissue.7 11 21 The morphology of ovoid round cells with crisp distinctive cell borders and perinuclear clear cytoplasm (‘fried egg appearance’) and prominent vasculature may be observed in glomangioma or smooth muscle in glomangiomyoma. Immunostains can be used to differentiate other ovoid or epithelioid tumours, including GIST and GNET. GNETs share several histological features with GGTs but demonstrate less prominent cell borders and secondary neuroendocrine markers for confirmation, including chromatin and CD56.14 GGTs and GNETs are best differentiated using morphology and immunohistochemistry.

The results of four studies on GTs/GGTs and the present case’s immunohistochemical results are demonstrated in table 1.6 7 11 21 GGT is characterised by the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin, collagen IV, laminin and calponin, as well as BRAF for atypical or malignant variants.22 Most GGTs/GTs reveal positivity for alpha-smooth muscle actin and uniform negativity for CD117.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical results of selected GT/GGT studies

| Antigen | Folpe et al6 | Miettinen et al11 | Wang et al21 | Lin et al7 | Total | Present case |

| a-SMA | 40/40 (100) | 23/23 (100) | 11/11 (100) | 21/21 (100) | 95/95 (100) | Positive |

| Collagen IV | 8/8 (100) | 15/16 (94) | 11/11 (100) | -- | 34/35 (97) | -- |

| Laminin | -- | 18/20 (90) | 11/11 (100) | 29/31 (93) | -- | |

| Calponin | 5/11 (45) | 11/11 (100) | -- | 21/21 (100) | 37/43 (86) | -- |

| Caldesmon | 7/12 (58) | 7/11 (64) | -- | -- | 14/23 (60) | -- |

| Synaptophysin | -- | 3/17 (18) | 2/11 (18) | 3/21 (14) | 8/49 (16) | Focally positive |

| S100-protein | 0/34 (0) | 0/20 (0) | -- | 0/21 (0) | 0/75 (0) | -- |

| Chromogranin | -- | 0/13 (0) | 0/11 (0) | 0/21 (0) | 0/45 (0) | Negative |

| Cytokeratin | 0/34 (0) | 0/14 (0) | 0/11 (0) | -- | 0/59 (0) | Negative |

| CD117 (c-KIT) | -- | 0/18 (0) | 0/11 (0) | 0/21 (0) | 0/50 (0) | Negative |

| CD56 | -- | -- | 0/11 (0) | -- | 0/11 (0) | Negative |

| AE1/AE3 | -- | -- | -- | 0/21 (0) | 0/21 (0) | -- |

GGT, gastric glomus tumour; GT, glomus tumour.

Several GGT/GT case reports, as well as the current case, reveal focal reactivity for synaptophysin, an important immunohistochemical neuroendocrine marker used to diagnose NET.23 Sixteen per cent of the GGTs analysed in the four reviewed immunohistochemical studies show focal positivity for synaptophysin. Importantly, none of the GGT/GT cases demonstrate the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin, INSM1 or CD56. According to the literature, there has not been a reported GGT case with chromogranin reactivity, suggesting a means to differentiate GGT from GNET. Moreover, the expression of c-Kit and CD56 holds diagnostic specificity for GNET as well.24 All tumours reviewed in the four GT/GGT studies demonstrated negativity for c-Kit and CD56, indicating another method to differentiate GGT and GNET. Furthermore, all GGT/GT are negative for CD117, separating them from GIST.

Ga-DOTATOC positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) may be another way to exclude GNET due to its common somatostatin receptor overexpression.25 GGTs rarely express this receptor. There has only been a single case report of a GGT with somatostatin overexpression.15 Therefore, negative Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT may help refute GNET and should be considered when there is suspicion of GGT.

Although malignant GGTs are exceedingly rare, several have been reported in the literature.26 Folpe et al propose GTT malignant criteria to be revealed with a peripheral rim of pre-existing benign GT and central atypia/mitoses. In soft-tissue, the diagnosis of malignant glomus tumour is reserved for tumours with marked cytologic atypia, atypical mitoses or increased mitoses (>5 mitoses per 50 hpf), spindling, an infiltrative growth pattern and/or necrosis. GT not fulfilling criteria for malignancy with at least one atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism are designated as having uncertain biological potential. GGTs, even with deep location and larger size, are mostly benign or of uncertain biologic potential.11 While GGT is currently included in its own category in the WHO classification for Digestive System Tumours 2020, suggestion for >5 cm, similar to other intra-abdominal mesenchymal tumours, would be better for GGT in comparison with its peripheral skin/soft-tissue counterpart. Features of myxoid or sclerotic change to denote favourable subungual GT have not been studied in GGT. BRAF immunohistochemistry has been presented by Folpe et al to indicate atypical growth if focal and malignant growth if diffuse in GT.6 Wide local excision with negative margins is considered the treatment of choice for GGT. In cases of malignant GGTs, chemotherapy has been used following resection with varying degrees of success in several reports.27 28

In conclusion, physicians may consider GGT when a synaptophysin-focally positive diagnosis of GNET is rendered. Immunohistochemistry for SMA, BRAF and other neuroendocrine markers, as well as negative Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT, may be helpful to separate these tumours. The treatment of choice for GGT is wide local resection with negative margins. In this case, due to the size and location of the tumour, the surgical approach of distal gastrectomy with Rou-en-Y gastrojejunostomy would remain the same. Additional prospective studies are needed to further characterise GGTs and generate standardised guidelines for treatment, follow-up and management. While the prognosis for most resected GGT is usually favourable, close patient follow-up for large, atypical or uncertain biological potential cases is advised.

Learning points.

Gastric glomus tumours may be considered as a differential for submucosal gastric tumour with ovoid cells and prominent vasculature, especially when the diagnosis is predicated on synaptophysin positivity.

If synaptophysin is focally positive on fine-needle aspiration biopsy, additional diagnostic studies such as Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT or identification of certain neuroendocrine markers (ie, SMA and BRAF) may be considered to verify gastric neuroendocrine tumour.

Glomus tumours can be benign, atypical or malignant using specific criteria, but they are mostly benign in gastric locations.

Footnotes

Contributors: CS, WGW, JCF-S and CCV developed the original idea, reviewed literature data, prepared the manuscript and provided additional review. CS contributed to major areas of the manuscript and provided a revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Sethu C, Sethu AU. Glomus tumour. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2016;98:e1–2. 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CDM, ed. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadelis A, Brooks CJ, Albaran RG. Gastric glomus tumor. J Surg Case Rep 2016;2016:rjw183. 10.1093/jscr/rjw183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S, Kumar A, Singh V. Gastric glomus tumor. Niger J Surg 2020;26:162–5. 10.4103/njs.NJS_8_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsagkataki ES, Flamourakis ME, Gkionis IG, et al. Gastric glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2021;15:415. 10.1186/s13256-021-03011-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1–12. 10.1097/00000478-200101000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin J, Shen J, Yue H, et al. Gastric glomus tumor: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 21 cases. Biomed Res Int 2020;2020:5637893. 10.1155/2020/5637893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H-W, Lee JJ, Yang DH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of glomus tumor of the stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006;40:717–20. 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai B, Mao C-S, Li Z, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography diagnosis of gastric glomus tumors. World J Clin Cases 2021;9:10126–33. 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namikawa T, Tsuda S, Fujisawa K, et al. Glomus tumor of the stomach treated by laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: a case report. Oncol Lett 2019;17:514–7. 10.3892/ol.2018.9621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miettinen M, Paal E, Lasota J, et al. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 32 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:301–11. 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato S, Kikuchi K, Chinen K, et al. Diagnostic utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy for glomus tumor of the stomach. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:7052–8. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.7052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Liu C, Ao W, et al. Differentiation of gastric glomus tumor from small gastric stromal tumor by computed tomography. J Int Med Res 2020;48:300060520936194. 10.1177/0300060520936194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mravic M, LaChaud G, Nguyen A, et al. Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of glomus tumor: an institutional experience of 138 cases. Int J Surg Pathol 2015;23:181–8. 10.1177/1066896914567330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K, Ahn B, Hong S-M, et al. A case of glomus tumor mimicking neuroendocrine tumor on 68 ga-DOTATOC PET/CT. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021;55:315–9. 10.1007/s13139-021-00717-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan K, Chetty R. Gastric glomus tumor: clinical conundrums and potential mimic of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10:7905–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003;97:934–59. 10.1002/cncr.11105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JP, Park SC, Park CK. A case of gastric glomus tumor. Korean J Gastroenterol Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe Chi 2008;52:310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Zhang G-B, Yan L, et al. Ct and enhanced CT in diagnosis of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas. Abdom Imaging 2012;37:738–45. 10.1007/s00261-011-9836-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang G, Park HJ, Kim JY, et al. Glomus tumor of the stomach: a clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases and review of the literature. Gut Liver 2012;6:52–7. 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.1.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z-B, Yuan J, Shi H-Y. Features of gastric glomus tumor: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular retrospective study. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:1438–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karamzadeh Dashti N, Bahrami A, Lee SJ, et al. Braf V600E mutations occur in a subset of glomus tumors, and are associated with malignant histologic characteristics. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:1532–41. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang JC, Jin XF, Weng SX, et al. Gastric glomus tumors expressing synaptophysin: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2017;46:756–9. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li T-T, Qiu F, Qian ZR, et al. Classification, clinicopathologic features and treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:118–25. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnbeck CB, Knigge U, Loft A, et al. Head-to-head comparison of 64cu-DOTATATE and 68ga-DOTATOC PET/CT: A prospective study of 59 patients with neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med 2017;58:451–7. 10.2967/jnumed.116.180430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaidi S, Arafah M. Malignant gastric glomus tumor: a case report and literature review of a rare entity. Oman Med J 2016;31:60–4. 10.5001/omj.2016.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negahi A, Jahanshahi F, Shahriari-Ahmadi A, et al. Lesser sac glomangiosarcoma with simultaneous liver and lymph nodes metastases mimicking small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumor; immunohistochemistry and empirical chemotherapy. Int Med Case Rep J 2019;12:339–44. 10.2147/IMCRJ.S220455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seban R-D, Bozec L, Champion L. Clinical implications of 18F-FDG PET/CT in malignant glomus tumors of the esophagus. Clin Nucl Med 2020;45:e301–2. 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]