Abstract

Despite the great promise for antibiotic therapy in wound infections, antibiotic resistance stemming from frequent dosing diminishes drug efficacy and contributes to recurrent infection. To identify improvements in antibiotic therapies, new antibiotic delivery systems that maximize pharmacological activity and minimize side effects are needed. In this study, we developed elastin-like peptide and collagen-like peptide (ELP-CLP) nanovesicles (ECnVs) tethered to collagen-containing matrices, to control vancomycin delivery and provide extended antibacterial effects against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). We observed that ECnVs showed enhanced entrapment efficacy of vancomycin by 3-fold as compared to liposome formulations. Additionally, ECnVs enabled the controlled release of vancomycin at a constant rate with zero-order kinetics, whereas liposomes exhibited first-order release kinetics. Moreover, ECnVs could be retained on both collagen-fibrin (co-gel) matrices and collagen-only matrices, with differential retention on the two biomaterials resulting in different local concentrations of released vancomycin. Overall, the biphasic release profiles of vancomycin from ECnVs/co-gel and ECnVs/collagen more effectively inhibited the growth of MRSA for 18 h and 24 h, respectively, even after repeated bacterial inoculation, as compared to matrices containing free vancomycin, which just delayed the growth of MRSA. Thus, this newly developed antibiotic delivery system exhibited distinct advantages for controlled vancomycin delivery and prolonged antibacterial activity relevant to the treatment of wound infections.

Keywords: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin, Collagen, Hydrogel, Wound dressing, Elastin-like peptide (ELP), Collagen-like peptide (CLP)

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Wound infection is a major impediment in the healing of chronic wounds, leading to serious life-threatening complications such as tissue necrosis, hemorrhage, and low-extremity amputations 1-3. Wound infection is usually characterized by an excessive inflammatory response involving immune cells, which are recruited by the release of toxins from bacteria colonizing the wound 4, 5. Further, colonies of pathogenic bacteria, including the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, form fibrous biofilms, which make it more challenging for host clearance mechanisms to eradicate bacterial colonies from the wound and stimulate wound repair 6-8. Thus, approaches to inhibit the growth of the bacterial populations in wound beds has been a target of drug delivery therapies for the treatment and prevention of wound infection while promoting wound healing.

Numerous topical formulations for wounds have been developed to manage and prevent wound infection 9-11. Synthetic and natural materials-based wound dressings in the form of hydrogels and films have been applied on the wound site to provide a moist environment, maintain the tissue temperature, and aid the wound healing process 12-14 Wound dressings containing antimicrobial/antibacterial agents enable control over local infections in situations where high concentrations of antibiotics are required, although the use of high antibiotic concentrations can lead to adverse effects such as renal toxicity and antibiotic resistance 15, 16. In addition, the presence of multidrug-resistant microorganisms vin the wound (e.g., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA) diminishes the efficacy of common antibiotics, leading to infection recurrence and antibiotic resistance 17. Thus, the sustained local delivery of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of antibiotics against MRSA is necessary to actively eradicate bacterial populations while minimizing adverse effects.

Nanoscale particles have been widely employed to encapsulate small-molecule therapeutics and control the release of these molecules over extended time periods. For example, liposomes have shown effectiveness in antibiotic delivery and bacterial growth inhibition for a number of decades 18-22, owing to their ability to increase the local concentration of antibiotics within bacterial cells 23-25, with improved pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. Indeed, antibiotics delivered by liposomes have exhibited efficacy against antibiotic-resistant microorganisms 26, 27; for example, liposomal delivery has been shown to increase the amount of intracellular methicillin accumulation and reduce bacterial populations by 96%, as compared to 40% for free methicillin 28. Likewise, liposomal delivery also has been shown to reduce the MIC of vancomycin against MRSA to 2- to 4-fold lower than that of free vancomycin 29, 30. Moreover, vancomycin-loaded liposomes have been shown to significantly reduced MRSA populations in a mouse surgical wound model relative to that of free vancomycin at the end of the 9th and 14th days of treatment 31.

Owing to the effectiveness of liposomes for antibiotic delivery, our group previously demonstrated the potential utility of employing collagen-like peptide (CLP; also known as collagen-mimetic peptide or CMP)-modified vancomycin-liposomes, tethered to collagen/fibrin hydrogels (co-gels), for the treatment of MRSA-infected wounds in vivo 32. CLPs, composed of (GXY)n units, can fold into triple-helix structures at temperatures below their melting temperature, Tm, but disassemble into single strands above their Tm 33, 34; this behavior enables them to hybridize with native collagen molecules through strand invasion at temperatures below the CLP Tm 35. We demonstrated that CLP modification of liposomes improved liposome retention on the co-gels, enhancing the sustained release of vancomycin and providing robust antibacterial effects against MRSA, as compared to liposome-containing co-gels without CLP modification 32. At the same time, the bioactivity of the co-gels stimulated cellular healing responses and improved wound repair in an in vivo murine wound model 36. While these results are promising, liposomal antibiotic delivery systems suffer limitations such as a short shelf-life and low encapsulation efficiency (ca. 2.7-5.7%) for hydrophilic antibiotics 19, 37, 38, which motivated our evaluation of alternative collagen-binding carriers.

In this study, we employed the thermoresponsive assembly/disassembly of extracellular-matrix (ECM)-inspired elastin-like peptide and collagen-like peptide (ELP-CLP) nanovesicles (ECnVs) to improve the encapsulation efficiency of hydrophilic drugs, and to leverage the ability of ECnVs to tether to collagen-based matrices to extend the controlled delivery of vancomycin for prolonged antibacterial effects. Our group developed ELP-CLP conjugates whose design facilitated the triple helical assembly of CLPs, as well as corresponding reductions in the inverse transition temperature (Tt) of the short ELP. This design approach resulted in assembly of stable vesicle-like nanostructures above the Tt of the ELP domain and disassembly above the Tm of the CLP domain 39-45. Our previous studies demonstrated that the ECnVs induce a minimal inflammatory response from macrophages, exhibit high cytocompatibility with murine fibroblasts, offer the ability to hybridize with collagen, and thermally control the delivery of a model drug 40. Thus, ECnVs offer significant potential owing to their high biocompatibility, tunable properties, and bioactivity of the peptide building blocks.

The overall goal of this study was to evaluate potential improvements in the efficacy of vancomycin delivery from ECnVs tethered to collagen-containing matrices (collagen and co-gel), and to evaluate the system’s antibacterial activity against MRSA. ECnVs controlled vancomycin release at a constant rate to maintain drug concentration for an extended period. Moreover, the different retention of ECnVs on collagen vs. co-gel affected the rates of ECnVs release from the matrices, leading to variations in the rate of biphasic vancomycin release depending on the matrix. The sustained release of vancomycin from the matrix-bound ECnVs extended the duration of antibacterial activity of vancomycin against MRSA, even with re-inoculation. Our finding suggests the potential for ECnVs in collagen-containing matrices as an option for preventing recurrence of infection and aid wound repair.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Low-loading (LL) Rink Amide ProTide® Resin, ethyl cyanohydroxyiminoacetate (Oxyma), and diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) were procured from CEM Corporation (Matthews, NC). Fmoc-protected amino acids including 4-azidobutyric acid and Fmoc-propargylglycine-OH, as well as O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (HBTU) were purchased from ChemPep Inc. (Wellington, FL). trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), N,N-dimethyl formamide (DMF), acetonitrile, methanol, and anhydrous ethyl ether were acquired from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ). Piperidine, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), ethanethiol, triisopropylsilane, tris-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethylamine (THPTA), (+)-sodium L-ascorbate, and copper (II) sulfate were procured from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cy3-maleimide was obtained from Click Chemistry Tools LLC (Scottsdale, AZ). 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)–2000-maleimide] (DSPE-PEG-Mal), and cholesterol were procured from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabama, USA), Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Nanocs Inc. (New York, USA), respectively. Type I bovine collagen (10 mg/mL) was obtained from Advanced BioMatrix (San Diego, CA). Fibrinogen from bovine plasma (Type I-S, 65-85% protein) and thrombin from bovine plasma (40-300 NIH units/mg protein) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis MO, USA). A luminescent strain of Staphylococcus aureus (SAP231, luminescent version of USA300 MRSA strain NRS384) was a kind gift from Dr. Roger Plaut 46. Vancomycin, tryptic soy broth, tryptic soy agar, and chloramphenicol were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis MO, USA).

2.2. Synthesis of ELP-CLP conjugates

The peptides [CLP (G8): (GPO)8GG or (GPO)8GC and ELP (F6): (VPGFG)6G’ (where G’ = propargyl glycine)] were synthesized via standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis using a Liberty Blue Automated Microwave Peptide Synthesizer (CEM Corporation, Charlotte, NC) as described in our previous reports 45. Briefly, each amino acid (4 molar equivalents) was added to the peptide chain by double coupling at 90 °C for 10 min with Oxyma (4 molar equivalents) and DIC (12 molar equivalents). For azido functionalization of the CLP, 4-azidobutyric acid (6 molar equivalents) was coupled to the N-terminus of the CLP on resin via a 2 h reaction with HBTU (6 molar equivalents) and DIPEA (12 molar equivalents). The peptides were cleaved from the resin after 2 h by incubation in 95:2.5:2.5 TFA:TIS:water (v:v:v). The crude peptides were purified via reverse-phase HPLC (Waters Inc., Milford, MA) on a Waters XBridge BEH130 Prep C-18 column using a linear gradient mixture of water (0.1% TFA) and acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) with ultraviolet detection at 214 nm. The molecular weights and purities of each of the purified peptides were confirmed (Fig. S1-4) via ultra-performance liquid chromatography, in line with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (Xevo G2-S QTof mass spectrometer; Waters Inc., Milford, MA). The purified CLP (6 μmol) and ELP (3 μmol) were conjugated via the copper (I)-mediated azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction as described in our previous papers 43. Briefly, ELP, CLP, Cu (II) sulfate (6 μmol), THPTA ligand (35.1 μmol), and (+)-sodium L-ascorbate (400 μmol) in 70:30 water:DMSO (v:v) were incubated for 1 h with stirring at 70 °C. Then, the ELP-CLP conjugate (F6-G8GG) was purified via HPLC at 70 °C and its purity and mass confirmed by UPLC-MS (Fig. S5&6).

2.3. Characterization of ELP-CLP conjugates

The melting temperature (Tm) of the ELP-CLP F6-G8GG (Tm = 57.9 °C; Fig. S7A) and the transition temperature (Tt) of the same ELP-CLP (Tt = 21.2 °C) were identified in a previous study 45. The ELP-CLP conjugate was dissolved in water (1 mg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C overnight after 30 min of heating at 80 °C to completely dissociate the ELP-CLP conjugate in solution (Fig. S7B). The resulting ECnV diameters were analyzed via DLS on a ZetaSizer Nano Series (Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, UK) at 173° as a scattering angle. The cumulant method was used for data fitting. The cross-sectional morphology of the ECnVs was evaluated via imaging on a Thermo Scientific™ Talos™ -TEM (Thermo Fisher scientific, Waltham, MA) operated at 200 kV. The ECnV samples (5 μL) were drop-cast onto carbon-coated copper grids (CF300-Cu, Electron Microscopy Sciences Inc.) and blotted after 1 min. Samples were stained using 1% PTA at pH 7 (3 μL) for 10 s and blotted. Then, samples were air dried for at least 2 h prior to TEM imaging.

2.4. Vancomycin encapsulation in ECnVs

The solution of ECnVs (dissolved in water) was heated at 80 °C for 30 min to completely disassemble the ELP-CLP conjugate. Vancomycin (1 molar ratio to ELP-CLP conjugate) in PBS at pH 7 was added to the solution of ELP-CLP conjugate. Vancomycin and the ELP-CLP conjugate were then mixed with a vortex mixer and incubated at 37 °C overnight to enable loading of vancomycin into the ECnVs during nanovesicle formation. Then, 10x PBS (Corning®, Corning, NY) was added to yield a final 1x PBS solution. For determining the encapsulation efficiency (EE) and loading capacity (LC) of vancomycin (van) in the ECnVs, each nanovesicle sample was centrifuged at 15K rpm for 10 min to separate the vancomycin loaded ECnVs from any unencapsulated vancomycin in the supernatant; subsequently, the ECnVs were resuspended in PBS. We note that the ECnVs are stable against aggregation during centrifugation (see DLS and TEM data below). The concentration of unloaded vancomycin in the collected supernatant was determined using absorbance measurements on the collected supernatant. Comparison of the concentration of vancomycin in the supernatant to the initial concentration of vancomycin in solution yielded an assessment of the concentration of vancomycin encapsulated in the ECnVs. The EE of vancomycin (van) in ECnVs was calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where of vancomycin-loaded in ECnVs, and of vancomycin added to the ELP-CLP solution for encapsulation.

The LC of vancomycin (van) in ECnVs was calculated using the following formula:

| (2) |

where of vancomycin-loaded in ECnVs, and of ECnVs.

2.5. Vancomycin encapsulation in liposomes

The liposomes were prepared by a traditional thin-film dehydration-rehydration protocol, followed by sequential extrusion through membrane filters with pore sizes of 200 nm and 100 nm, respectively 47. Lipids with a molar ratio of 73:24:3 (DPPC:Cholesterol:DSPE-PEG-Mal) were mixed in 4:1 chloroform and methanol (v:v) and added into a round-bottom flask. The lipid film was formed after evaporation of the organic solvent for at least 2 h via rotary evaporation at 40 °C and 400 psi. The vancomycin in PBS at pH 7 was added to the flask at a 3-fold excess of vancomycin:total mass of lipids, and the flask was rotated for 15 min at 60 °C for rehydration. The samples were then sonicated for 2 min before extrusion. The lipid and vancomycin suspension was first extruded through a polycarbonate membrane with a pore size of 200 nm (15 times), and subsequently, through a membrane with pore size of 100 nm (10 times). The diameters of the vancomycin-loaded liposomes were evaluated via DLS with a ZetaSizer Nano Series (Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, UK) with a scattering angle of 173° (Fig. S8). In order to determine the encapsulation efficiency (EE) and loading capacity (LC) of vancomycin in the liposomes, the sample was centrifuged at 15 K rpm for 10 min for precipitation of vancomycin-loaded liposomes to remove any unencapsulated vancomycin, and the concentration of the unencapsulated vancomycin was determined via evaluation of the absorbance of the supernatant. The EE and LC of vancomycin in the liposomes was calculated using Formula 1 and 2 above. The vancomycin-loaded liposomes were re-suspended in PBS and lyophilized with 20 mM sucrose prior to incorporation into collagen-containing matrices.

2.6. Vancomycin release kinetics from nanocarriers

Vancomycin release rates from vancomycin-loaded liposomes and vancomycin-loaded ECnVs were evaluated in a Slide-A-Lyzer™ Mini dialysis device with a 10K molecular weight cutoff (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA), using the rate of free vancomycin transport across the dialysis membrane as a control. 100 μL aliquots of each formulation (free vancomycin, vancomycin-loaded liposomes, and vancomycin-loaded ECnVs) were placed in the dialysis cup and immersed in 2 mL of PBS buffer in a glass vial. The samples were incubated at 37 °C with a shaking at 225 rpm. The PBS, containing released vancomycin (400 μL), was collected and replaced with fresh PBS at 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, and 168 h. At 168 h, the samples were incubated at 80 °C for 30 min to recover the vancomycin from the disassembled ELP-CLP (Fig. S7B) (or liposome) and collected as the 169 h time point. The concentrations of released vancomycin in PBS was determined using an absorbance measurement at 280 nm on a Nanodrop spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA), and the cumulative percentage release of vancomycin per sample was calculated using the following equation 48:

| (3) |

where represents the amount of vancomycin encapsulated in the ECnVs or liposomes, is the total volume of the release media, is the volume of each sample that was collected at each time point, is the concentration of vancomycin measured by UV absorbance in the sample, and represents the concentration of vancomycin in the sample.

In order to account for diffusion across the dialysis membrane of any free vancomycin remaining in the encapsulated samples, free vancomycin controls were formulated based on the calculation of the encapsulation efficiency (EE) for the liposomes and ECnVs. Because the EE for the liposomes was 15.2% of the initial vancomycin employed during formulation, free vancomycin samples with 84.8% of the initial vancomycin were employed as controls for the liposomes. Meanwhile, free vancomycin samples with 51.8% of the initial vancomycin were employed as controls for the ECnVs since the EE for the ECnVs was 48.2% of the initial vancomycin employed during formulation. Then, the release profiles of the relevant free vancomycin control samples were subtracted from the data in Figure 2A to acquire the data presented in Figure 2B.

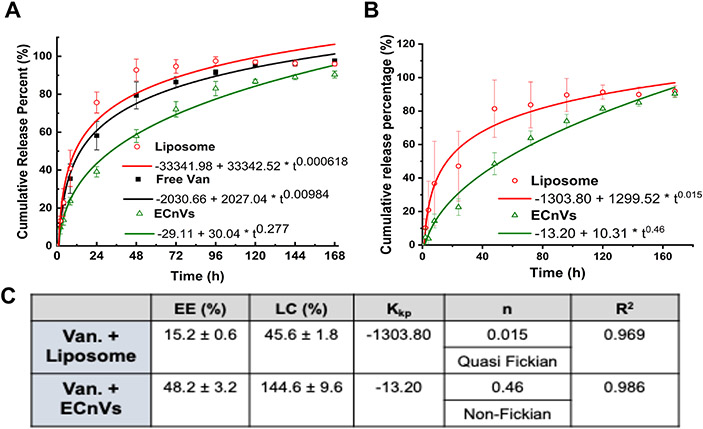

Figure 2.

Vancomycin release from nanocarriers (A) without removing or (B) with mathematically removing the unloaded Vancomycin at 37 °C. The release profiles were fitted with Korsmeyer-Peppas model. (C) Table for encapsulation efficiency (EE) and loading capacity (LC) of vancomycin in liposome and ECnVs and constants for Korsmeyer-Peppas model fitting. Kkp indicates Korsmeyer release rate constant and n indicates diffusional exponent. Each data represents mean ± standard deviation for n=6.

2.7. Collagen and co-gel matrix retention and release of nanovesicles

First, ECnVs were labelled with Cy3-Maleimide using a Michael-type addition reaction (Fig. S9). Briefly, a 1:9 (VPGFG)6-(GPO)8GC:(VPGFG)6-(GPO)8GG mass ratio in PBS was heated at 80 °C to completely dissociate any CLP triple helices that anchor ECnV assembly, and the heated samples were subsequently mixed thoroughly. Then, the ECnVs were allowed to form by incubation at 37 °C overnight. Cy3-Maleimide (10 molar equivalents as compared to (VPGFG)6-(GPO)8GC) was added into the ECnV solution and the mixture was rotated at 50 rpm for 2 h at 37 °C. The unreacted Cy3-Malemide was removed by centrifugation at 15K rpm for 10 min, and the labeled ECnVs were suspended in PBS. The Cy3-labeled ECnVs were lyophilized with 20 mM sucrose. For the control experiment, fluorescently labeled liposomes were prepared (DPPC : Cholesterol : DSPE-PEG-Maleimide : NBD-PC (72.6:24:3:0.4)) as described in our previous work 49. Additionally, CLP-functionalized, fluorescently labeled liposomes were prepared through one of two methods: post-surface modification with CLP, or pre-surface modification with CLP. For post-surface modification, CLP was added to the fluorescently labeled liposome using a Michael-type addition reaction between DSPE-PEG-Maleimide of the fluorescently labeled liposome and thiol groups on the cysteine residue of the CLP ((GPO)8GC). For pre-surface modification, prior to liposome formulation, CLP ((GPO)8GC)) was conjugated with DSPE-PEG-Maleimide lipid to prepare DSPE-PEG-CLP lipid, which was confirmed by MALDI-ToF (Fig. S10), as described in the literature 50, 51. CLP-functionalized, fluorescently labeled liposomes were prepared (DPPC : Cholesterol : DSPE-PEG-CLP : NBD-PC (72.6:24:3:0.4)) following the same protocol used to prepare fluorescently labeled liposomes.

The pre-gel mixtures of collagen or co-gel were prepared separately. The pre-gel collagen was composed of 4 mg/mL neutralized bovine collagen type I (Fibricol®) with 10X PBS and 0.1N NaOH, and the pre-gel co-gel was composed of 4 mg/mL neutralized bovine collagen type I in PBS, 1.25 mg/mL fibrinogen in 20 mM HEPES pH 6, and 0.156 IU/mL thrombin in 20 mM HEPES pH 6. The lyophilized Cy3-labeled ECnVs or fluorescently labeled liposomes were suspended in the pre-gel mixtures of collagen or co-gel. Then, samples were added to a microscope slide for gelation overnight. The Cy3-labelled ECnVs (λex 532 nm and λem 568 nm) or fluorescently labeled liposomes (λex 564 nm and λem 531 nm) and autofluorescence of collagen fibers (reflected light at 405 nm) within the matrices were visualized both before and after washing (with PBS overnight at 37 °C) using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope with C-Apochromat 40x water objective. The 3D image plot and image analysis were performed using Volocity Imaging software (Quorum Tech. Inc., Canada). In addition, in vitro Cy3-labeled ECnV release from the matrices (collagen vs. co-gel) was measured for matrix samples containing Cy3-labeled ECnVs. Lyophilized Cy3-labeled ECnVs were suspended and mixed well into the pre-gel mixture, and 100 μL samples were transferred into non-coated 48-well plate wells for gelation at 37 °C overnight. Then, 500 μL of PBS was added to visually turbid hydrogel samples in each well to initiate the release experiments with the (unloaded) ECnV-loaded matrices. The release samples (100 μL) were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C. The cumulative release of ECnVs was determined via fluorescence measurements at λex 532 nm and λem 568 nm on a SpectraMax i3x multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC. San Jose, CA) and using equation (2).

2.8. Vancomycin release from matrices

Similar to the study of Cy3-labeled ECnVs release from matrices, in vitro vancomycin release from the matrices (collagen vs. co-gel) was measured for matrix samples containing either free vancomycin, vancomycin-loaded liposomes, or vancomycin-loaded ECnVs. Collagen matrices were prepared with a neutralized 4 mg/mL bovine type I collagen, and co-gels were prepared by mixing 4 mg/mL neutralized bovine type I collagen, 1.25 mg/mL fibrinogen in 20 mM HEPES at pH 6, and 0.156 IU/mL thrombin in 20 mM HEPES at pH 6. In these pre-gel mixtures of collagen or co-gel, the lyophilized free vancomycin, vancomycin-loaded liposomes, or vancomycin-loaded ECnVs were suspended and mixed well. Then, 100 μL samples were transferred into non-coated 48-well plate wells before gelation by incubation at 37 °C overnight. After overnight gelation, 500 μL of PBS at 37 °C was added to visually turbid hydrogel samples in each well, which represented t = 0 for the vancomycin release. The released samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h at 37 °C after the addition of PBS. After the last time point of release, samples were heated at 80 °C for 30 min to completely dissolve the matrices for the recovery of remaining vancomycin, and these samples were collected as the 96.5 h time point. The cumulative vancomycin release was determined using absorbance measurements at 280 nm using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA) and using equation (2).

2.9. Antibacterial activity of vancomycin-loaded in ECnVs in matrices

Similar to the re-inoculation protocols employed in our previous study 32, collagen gel or co-gel (100 μL) was loaded with free vancomycin or vancomycin-loaded ECnVs at concentrations of 4, 7, or 10 μg/mL vancomycin per gel. Gels were added to the wells of black 96-well plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight for gelation. After gelation, samples of the luminescent MRSA strain (SAP231, the luminescent version of the USA300 MRSA strain NRS384) were diluted in tryptic soy broth with chloramphenicol (10 μg/mL) to prepare solutions of 5 × 105 cfu/mL of MRSA. 200 μL of MRSA (5 × 105 cfu/mL) were added to each well of a 96-well plate; the final concentrations of vancomycin in the MRSA cultures were 1, 2, and 3 μg/mL. The plate was incubated at 37 °C, with shaking at 150 rpm, for 16 h, and the optical density (O.D.) at 600 nm and luminescence of luminescent MRSA was measured using the absorbance module and the photomultiplier tube (PMT) detector of the luminescence module of a SpectraMax i3x multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, San Jose, CA) every two hours. Sixteen hours after the first inoculation, the bacterial cultures were removed from the wells and the wells were rinsed with the culture broth. Then, a fresh aliquot of 200 μL of MRSA (5 × 105 cfu/mL) was added into each well of the 96-well plate for re-inoculation. The bacterial growth was evaluated using O.D. and luminescence measurements every 2 h for an additional 16 h.

2.10. Mathematical model fitting and statistical analysis

The vancomycin or ECnV release profiles were analyzed using the fitting functions BoxLucas1 for first-order release and Allometric2 for Korsmeyer-Peppas kinetics with the max number of iterations set to 500 and the tolerance set to 1−6 in OriginLab (Northampton, MA). Unless indicated, all experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. The statistical significance was analyzed using OriginLab software (Northampton, MA). Sample groups were compared using a Student’s t-test with a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

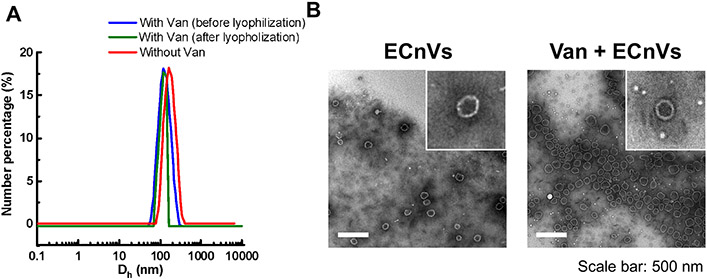

3.1. Characterization of vancomycin- loaded ECnVs

To evaluate whether the loading of vancomycin in ECnVs influenced the physical properties of the ECnVs, the diameters and morphology of ECnVs before and after vancomycin encapsulation were examined using DLS and TEM imaging, respectively. The ECnVs (Dh = 157.0 ± 5.0 nm) exhibited a decreased diameter (Dh = 122.3 ± 6.2 nm) after the loading of vancomycin (Fig. 1A), which was similar behavior to that of liposomes after vancomycin loading 32, and also similar behavior to that of ECnVs after loading of the hydrophobic dye fluorescein 40. Furthermore, the morphology of the ECnVs was similar before and after loading of vancomycin (Fig. 1B), indicating that the encapsulation of vancomycin in the nanovesicles did not disrupt ELP-CLP assembly.

Figure 1.

Characterization of vancomycin loaded ECnVs (A) Size measurement of ECnVs using DLS before and after vancomycin loading and after lyophilization. (B) Representative TEM images of ELP-CLP before and after Vancomycin loading. Scale bar is 500 nm.

3.2. Vancomycin release kinetics from nanocarriers

To determine the release kinetics of vancomycin from ECnVs, in vitro vancomycin release studies were conducted using a dialysis method under physiologically relevant conditions. The release kinetics of vancomycin from ECnVs were calculated as the cumulative release percentage over a period of 7 days. As a control, vancomycin-loaded liposomes (Dh = 136.6 ± 1.0 nm) of similar diameter as the vancomycin-loaded ECnVs (Fig. S8) were used. The vancomycin release data from the liposomes and ECnVs is presented in Figure 2A; it is clear from the data that the release of vancomycin from ECnVs was much slower than the release of vancomycin from the liposomes. The data were fit to a Korsmeyer-Peppas model, and the numeric coefficient (n) from this model (which describes the mechanism of release), was less than 0.45 for both nanocarriers, indicating a similar mechanism of release of vancomycin from the ECnVs and liposomes (Fig. 2A). The release kinetics of free vancomycin were also determined and mathematically subtracted from the overall release profiles to account for contributions of the diffusion of unencapsulated vancomycin across the dialysis membrane and to allow a more direct comparison of the rates and mechanisms of release of vancomycin from the carriers (Fig. 2B and 2C); the Korsmeyer-Peppas model was utilized to characterize the release kinetics of these corrected release profiles (Fig. 2B). Based on the data in Fig. 2B, the vancomycin was released from liposomes largely via diffusion (n < 0.45), whereas the release of vancomycin from ECnVs occurred mainly via both diffusion and dissolution mechanisms (0.45 < n < 0.8) (Fig. 2C), indicating that the vancomycin release kinetics and mechanism are influenced by the type of nanocarrier.

3.3. ECnVs retention and release on/from matrices

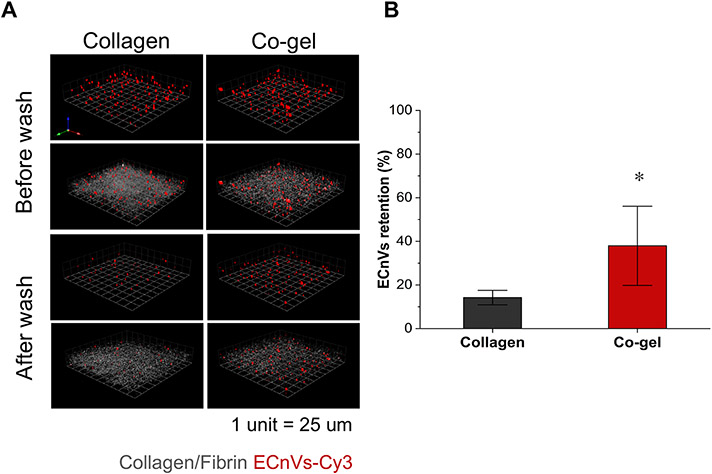

In order to characterize the retention of ECnVs on collagen-containing matrices, fluorescently labeled ECnVs in collagen vs. co-gel matrices were detected using confocal microscopy via comparison of the fluorescence before and after rinsing the ECnV-loaded matrices with PBS at 37 °C. Prior to conducting these experiments, we confirmed via TEM imaging that the addition of the fluorescent label, Cy3, did not disturb the assembly of the ECnVs (Fig. S11). Additionally, we prepared liposomes and CLP-liposomes to evaluate the effect of the CLP on hybridization/matrix retention; these experiments were conducted with liposomes instead of ECnVs as ECnVs cannot be prepared in the absence of CLP. The diameters of the lyophilized liposomes and CLP-liposomes were assessed after resuspension in PBS using dynamic light scattering, which confirmed that the liposomes and CLP-liposomes were not aggregated before incorporation in the matrices (Fig. S12). The fluorescence retained after washing the ECnV in co-gel samples (36.0 ± 4.0 %) was significantly greater than the fluorescence observed for collagen hydrogels (14.2 ± 3.3 %) (Fig. 3), which agrees with the observation that CLP-liposome show greater retention in co-gels than in collagen gels (Fig. S13). Since the shear storage moduli of the two hydrogel matrices were similar (G’Collagen+ECnVs = 40.5 ± 5.8 Pa and G’Co-gel+ECnVs = 47.3 ± 2.4 Pa) as determined via oscillatory rheology (Fig. S14), the difference in retention of ECnVs in collagen vs co-gel most likely resulted from differences in the interactions of the ECnVs with the collagen in these substrates. Additionally, the lower retention of liposomes within and on the of surfaces of the matrices, as compared with CLP-liposomes (Fig. S13 and S15), confirmed that the retention of both ECnVs and CLP-liposomes likely occurred via triple helix formation of CLPs with collagen molecules of the matrices. Thus, these results suggest that triple helix formation of the CLPs with collagen is more facile in the co-gel than the collagen.

Figure 3.

ECnVs retention on matrices at 37 °C. (A) Representative 3D plotted confocal images of ECnVs-Cy3 (Red) and collagen (Grey) in Collagen matrix or Co-gel matrix before and after wash. 1 unit is 25 μm. (B) Image quantification for fluorescent intensity of ECnVs after wash normalized to the intensity before wash. Each data represents mean ± standard deviation for n=6. An unpaired student’s t-test with equal variance was used to detect statistical significance. *p<0.0001 for co-gel relative to collagen.

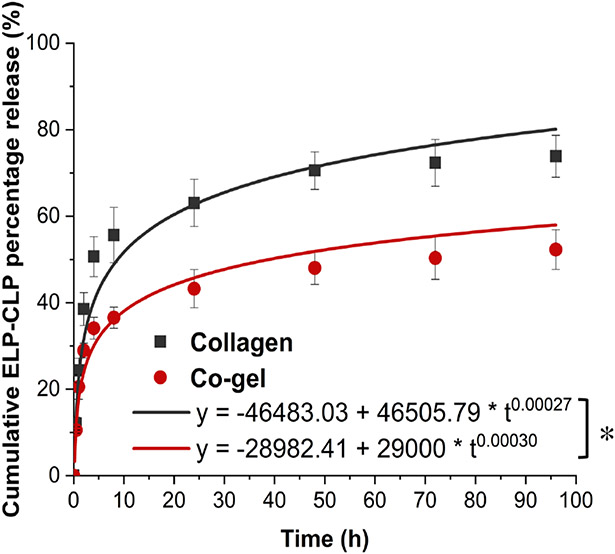

Moreover, to understand how ECnV release from the matrices influenced vancomycin release from the ECnV-containing matrices, the cumulative release profiles of Cy3-labeled ECnVs from collagen vs. co-gel were determined via fluorescence measurements (Fig. 4). Mathematical fitting of the cumulative release over 96 h with the Korsmeyer-Peppas model suggested that the overall rate of release of ECnVs from the co-gel (Kkp = 29000) was 1.6-fold slower than the rate of release from collagen (Kkp = 46500), indicating that ECnV sequestration in the co-gel was significantly greater than in collagen gels. Given the similarities in the physical properties of these hydrogels, and the 10-fold greater pore size of the hydrogels versus the ECnV diameter, these observed differences in sequestration and release are likely due to a different extent of CLP hybridization based on the different micro-morphological structure of collagen fibers, such as fiber diameters differences in the co-gels vs. collagen gels 52, 53.

Figure 4.

ECnVs release from matrices at 37 °C for 96 h. Release profile were fitted Kormeyer-Peppas model. Each data represents mean ± standard deviation for n=3. The statistical difference of Kkp states *p<0.05.

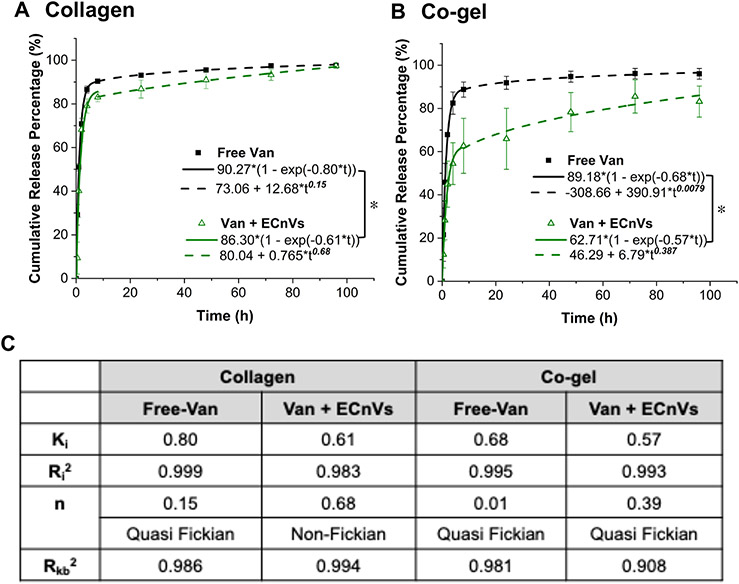

3.4. Vancomycin release from ECnVs tethered in collagen-containing matrices

The cumulative release of vancomycin from vancomycin-loaded ECnVs tethered in the matrices was determined. Mathematical fitting of the cumulative release with either the Korsmeyer-Peppas (fitting failed) or 1st order release models (Fig. S16) alone yielded poor fits to the data, suggesting that there could be multiple behaviors mediating vancomycin release. The initial burst release of vancomycin from ECnVs in the matrices was fit with high fidelity to the 1st order release model up to 8 h (Fig. 5); subsequently, data were fit to the Korsmeyer-Peppas model from 8 h to day 4, with the expectation that release in this window would be dominated by the vancomycin release from the ECnVs tethered in the matrices. The cumulative release of free vancomycin from the matrices was close to 70-80% at the initial 8 h time point, similar to previous reports of vancomycin release from collagen-based scaffolds 32, 54, 55. In contrast, the vancomycin release from ECnVs, over the initial 8 hours, from both collagen (Ki = 0.61) and co-gel (Ki = 0.57) matrices, was significantly slower (p<0.05) than free vancomycin release from the matrices (collagen (Ki = 0.80) and co-gel (Ki = 0.68)). These data suggest that the early release of the vancomycin from the loaded ECnVs likely resulted from non-tethered vancomycin-loaded carriers on matrices rather than from the presence of free vancomycin. In addition, after the initial burst release of vancomycin from the released ECnVs from the matrices, the cumulative release of vancomycin from the vancomycin-loaded ECnVs in the co-gel (63%) at the 8 h time point was significantly less (p<0.05) than that observed from the collagen gel (83%). However, we have observed that the release rates of vancomycin at the 8 h time point from non-tethered liposomes loaded in the collagen gel (67%) and co-gel (69%) were nearly identical (Fig. S17). Thus, the results indicate slower vancomycin release from the vancomycin-loaded ECnVs in the co-gel matrices relative to that from collagen gels, likely due to a greater retention and slower release of ECnVs in the co-gel (Fig. 3 and 4).

Figure 5.

Vancomycin release from ECnVs tethered in (A) collagen or (B) co-gel matrix. (C) Release profile were fitted by first-order kinetics from 0 to 8 h (solid line) and Kormeyer-Peppas model from 8 h to 96 h (dotted line). Ki = first order constant, Kkp = Korsmeyer release rate constant, and n = diffusional exponent. Each data represents mean ± standard deviation for n=4. The statistical difference of Ki states *p<0.05.

After the initial 8 h release, the data from 8 h to day 4 were fit to the Korsmeyer-Peppas model with the expectation that release in this time period was mainly from the vancomycin release from the ECnVs tethered in the matrices. The diffusional exponent (n) of the Korsmeyer-Peppas model fitting revealed differences in the release mechanism, with n < 0.45 indicating diffusion-controlled release, 0.45 < n < 0.8 indicating both diffusion- and dissolution-controlled release, and 0.8 < n, indicating dissolution-controlled release. Vancomycin release from ECnVs in collagen gels (n = 0.679) was classified as both diffusion- and dissolution-controlled, and vancomycin release from co-gels (n = 0.387) was classified as diffusion-controlled. Altogether, the data indicate that ECnVs enable the delay of vancomycin release, while the different retention of ECnVs on different collagen-containing matrices can also be leveraged to tune release profiles.

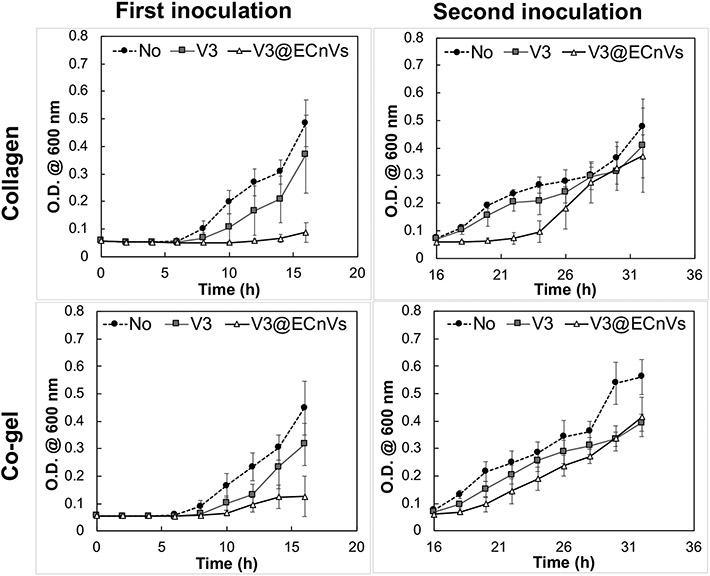

3.5. Antibacterial effects of vancomycin-loaded ECnV-tethered matrices against MRSA

To evaluate possible improvements in the antibacterial activity of vancomycin when delivered from ECnVs tethered to collagen or co-gel matrices, the growth of luminescent MRSA cultured on vancomycin-loaded ECnV-tethered matrices was monitored for 16 hours post-inoculation. To simulate a recurrent bacterial infection 1, 56, an additional inoculation of MRSA was made at the 16 h timepoint, and bacterial growth was monitored after an additional 16 h of culture. Vancomycin-loaded ECnVs were tethered in the collagen or co-gel matrices at a final vancomycin concentration of 2 μg/mL, which is the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for MRSA (5 × 105 cfu/mL) 32. The vancomycin-loaded ECnV-containing matrices inhibited the growth of MRSA for 14 h (collagen) and 10 h (co-gel) after the first inoculation, while free vancomycin in either matrix failed to inhibit MRSA (Fig. S18 & 19). Increasing the concentration of tethered, vancomycin-loaded ECnVs (in collagen and in the co-gel) to 3 μg/mL extended the inhibition of the growth of MRSA (Fig. 6), although free vancomycin at this concentration also delayed (but did not halt) MRSA growth. The vancomycin-loaded ECnVs in the collagen matrix completely inhibited the growth of MRSA for 16 h with the first inoculation and an additional 8 h after the second inoculation (for a total time of 24 h). Vancomycin-loaded ECnVs in the co-gel matrix also completely inhibited the growth of MRSA for 16 h with the first inoculation and delayed the growth of MRSA an additional 2 h after the second inoculation (for a total 18 h). This study indicated that the ECnVs, both released and tethered in matrices, maintained a sufficiently high local concentration of vancomycin to inhibit the growth of MRSA, as compared to release of free vancomycin from matrices. In addition, the different release kinetics of vancomycin from ECnVs in collagen vs. co-gel controlled the duration of the antibacterial effect.

Figure 6.

Anti-bacterial activity of vancomycin loaded ECnVs tethered collagen/co-gel matrices against MRS A . Optical density measurement of MRS A cultures grown in blank collagen/co-gel (black circle), vancomycin (3 μg/mL) loaded collagen/co-gel (grey square), and vancomycin (3 μg/mL) loaded ECnVs tethered collagen/c-gel (white triangle) with a total of two bacterial inoculations (16 h per inoculation). Each data represents mean ± standard deviation for n = 3.

4. Discussion

The difficulty in eradicating MRSA populations from wounds using commercially available antibiotics is a persistent challenge, leading to incomplete wound healing and potential risks of further antibiotic resistance. As a potential approach to improve antibiotic efficacy, we developed a peptide-based nanocarrier, ECnVs, and demonstrated for the first time that the stability and specific interactions of these nanoparticles with native collagen offered a means to control the delivery of vancomycin for inhibition of MRSA growth.

The peptide-based nanocarrier enabled improved encapsulation efficiency and controlled delivery of vancomycin in solution when compared with liposome nanocarriers, consistent with the expectation that the physical chemistry between drugs and nanocarriers is a key factor in determining encapsulation efficiency and release kinetics. ECnVs encapsulated a greater amount of vancomycin (EE = 48.2% and LC = 144.6%) and facilitated both dissolution and diffusion mediated sustained delivery of vancomycin; in contrast, the liposome nanocarrier encapsulated significantly less cargo (EE = 15.2% and LC = 45.6%) and delivered vancomycin with more rapid, diffusion-controlled first-order kinetics. Generally speaking, encapsulation of drugs in nanocarriers protects the drug against degradation and enhances sustained drug release, resulting in improved pharmacokinetics 57, 58. However, the high water solubility of hydrophilic drugs makes it difficult to encapsulate/sequester hydrophilic drugs in liposomes, hydrogels, nanoparticles, and/or fiber-based carriers, thus resulting in undesired and rapid burst release 59-62. In addition, the steric hindrance from the inclusion of cholesterol in liposomal carriers (which is necessary to improve liposome stability for use in vivo), can result in low encapsulation efficiency of hydrophilic cargo. These general difficulties are reproduced in our control studies, in which a low EE of vancomycin in the liposome is observed (EE = 15.2% and LC = 45.6%) along with rapid first-order diffusive release of the vancomycin cargo (n = 0.015 in the Korsmeyer-Peppas model) (Fig. 2) 19, 37, 38, 63.

The use of our peptide-based ECnV carriers, in contrast, enabled more efficient encapsulation of vancomycin by exploiting the thermal responsiveness of these carriers as a mechanism for loading. Vancomycin can be solubilized at elevated concentrations along with the monomeric ELP-CLP, at temperatures above its Tm; thermally-induced assembly of ELP-CLP into vesicles upon cooling leads to high efficiency of drug loading, which is one of advantages of peptide self-assembled nanocarriers 64, 65. For example, elastin-based protein diblock copolymer nanoparticles achieved approximately 50% encapsulation efficiency for the anti-proliferative hydrophobic drug rapamycin, for cancer treatment 66. In addition, nanoparticles formed by the conjugation of low molecular weight polylactide and self-assembled lipid-like V6K2 peptides enabled efficient encapsulation of both hydrophilic doxorubicin (44 ± 9%) and hydrophobic paclitaxel (>90%) in the nanoparticles 67. The additional barrier from the attractive interactions between V6K2 peptide and drugs delayed the release of doxorubicin and paclitaxel from V6K2 peptide assembled polylactide nanoparticles as compared with the release from ethylene glycol polylactide nanoparticles. Similarly, the hydrophobic coacervation of ELP block in the ECnVs could behave as an additional barrier for vancomycin release. Due to hydrophobic interactions with the addition of pi-pi stacking, hydrogen bonding, and charge-charge interaction from the side chains of the ELP sequence, the ELP block has been shown to collapse tightly, resulting in small pore sizes when these polypeptides coacervate 68-70. On the other hand, only hydrophobic interactions of alkyl chains and cholesterol form the hydrophobic barriers in liposome bilayers to reduce water penetration 71, 72. Thus, the coacervation of the ELP in the vesicle bilayer likely provides a more stable barrier to diffusion relative to the liposome bilayer, supporting sustained vancomycin release with both diffusion and dissolution mechanisms as compared to the mainly diffusion-based mechanism for vancomycin release from the liposome. Such sustained release behavior of drug from ECnVs could expand the performance of therapeutics by minimizing adverse off-target effects and the toxicity with burst release of high concentrations of cargo 73.

Next, we observed different levels of ECnV retention on the collagen and co-gel matrices, which would additionally influence the release of vancomycin from ECnV-loaded matrices. The pore sizes of highly similar collagen and co-gel hydrogels reported in previous literature are typically > 1 μm, which is at least 10 times larger than the measured diameters of ECnVs (~Dh = 130 nm)74-76. This large difference in pore size versus ECnV diameter suggests that the retention of ECnVs in the collagen and co-gel hydrogels in this work is almost certainly a result of the interaction of the CLPs on the ECnVs with the collagen molecules of the hydrogels through a strand invasion process, rather than physical entrapment of ECnVs within the collagen and co-gel networks. Thus, we believe that the levels of ECnVs retention in collagen and co-gel matrices are minimally influenced by the physical features of matrices but maximally influenced by molecular interactions between CLPs on ECnVs and collagen molecules within the collagen and co-gel matrices. ECnVs tended to be retained to a greater extent on the co-gel compared to the collagen matrix (Fig. 3 and 4), suggesting that the collagen in the co-gel may be more accessible for triple helix formation with the CLPs that are on the exterior of the ECnVs. Both collagen and fibrin contribute to hydrogel formation via fibrillogenesis driven by physico-chemical interactions between peptide chains that can be triggered with stimuli such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength 77. The Barocas group reported a related collagen-fibrin co-gel with high concentrations of collagen (68-83%) that comprised two interpenetrating but non-interacting networks (e.g., ‘parallel networks’); the reported conditions in those studies are similar to those of our co-gels in this report (76% collagen in our co-gel) 53. The mechanical properties of the parallel co-gel networks were driven by the competition between the extensibility of fibrin and stiffness of collagen. For example, although the tangent modulus of fibrin gel alone was much smaller than that of the co-gel, the tangent moduli of co-gel and collagen with the same collagen concentration were similar, consistent with our observation of similar shear storage moduli for the co-gel and collagen matrices (Fig. S14) 52. SEM and confocal imaging analysis revealed that the morphological structure of collagen fibrin networks were altered to have the average collagen fiber diameters smaller in the co-gel than pure collagen gels, and this physical feature alone would be expected to provide more sites for interaction, on a surface area-per-volume basis, with the collagen in the co-gel formulations (Fig. S13 and S15) 32, 36, consistent with our observations of significantly greater ECnV retention on the co-gel than collagen gel (Fig. 3 and 4).

In addition, the retention of ECnVs in matrices would be necessary to support controlled release of vancomycin from either matrix, and enhanced retention on the co-gel would be expected to reduce vancomycin release from the co-gel versus that from the collagen matrix (Fig. 5). The pore sizes of both collagen and fibrin gels have been reported to be on the micron length scale, which is much larger than the nanometer-scale of ECnVs 75, 78. Thus, the initial burst release of vancomycin likely results from the rapid release of non-tethered ECnVs from the matrices (Fig. 4). Moreover, our previous studies showed that the CLP modification of liposomes, and their incorporation into co-gel matrices, enhanced the sustained release of vancomycin, as compared to non-CLP liposomes in the same matrices 32. After the initial burst release of vancomycin, the release of vancomycin from ECnVs in collagen and co-gel matrices was sustained, although via different release mechanisms (Fig. 5). These different mechanisms could result from differences in release kinetics between the tethered and untethered (but encapsulated) van-loaded ECnVs in collagen and in the co-gel over the incubation time.

The release kinetics of vancomycin from ECnVs in the matrices regulated the duration of antibacterial effects against MRSA. Vancomycin is one of the most effective options for treatment of MRSA infections, which is one of the major Gram-positive microorganisms found in chronic wounds 79. However, wound infections by MRSA are often recurring, leading to the critical need for the better antibiotic delivery systems to enhance the prolonged duration of its antibacterial effect against MRSA 80, 81. A biphasic drug-release profile has been reported to have significant practical advantages in managing MRSA infections, including implant-associated infections 82, 83, bone infection 84, and wound infection 85. The previously reported biphasic drug-release profiles exhibit an initial 10 h burst release of vancomycin at least above its MIC to completely eradicate bacterial colonies, followed by a sustained release of 0.36% per h for 24 h, a prolonged period to eliminate any remaining bacteria 86, 87. In agreement with this observation, we demonstrated that vancomycin release from ECnV-tethered onto both collagen and co-gel followed biphasic drug-release; an initial 8 h burst release phase was followed by sustained release. The vancomycin-loaded ECnVs released during the initial burst release would result in a localized high concentration of vancomycin, entrapped in the released ECnV, potentially leading to more efficient inhibition of MRSA than vancomycin that freely diffuses from matrices.

We observed that the duration of MRSA inhibition was different depending on the vancomycin release from ECnV-tethered collagen vs. co-gel. In fact, the maintenance at the infection site of antibiotic above its MIC (2 μg/mL for MRSA (5 × 105 cfu/mL)) is a key factor in mediating antibacterial effects. Due to the slower release of ECnVs from the co-gel than collagen, the local concentration of vancomycin was not maintained above the MIC (~60% cumulative release at 8 h = 3 μg/mL × 0.6 = ~1.8 μg/mL, which is less than the reported MIC), resulting in the incomplete eradication of MRSA at the initial time and a shorter duration of MRSA growth inhibition than for the vancomycin-loaded ECnVs released from the collagen matrix (~81% cumulative release at 8 h = 3 μg/mL × 0.83 = ~2.43 μg/mL, which is greater than the reported MIC) (Fig. 5 and 6). In addition, the sustained release of vancomycin (0.0024 μg/mL release per h for collagen and 0.006 μg/mL release per h for co-gel from 8 h to 32 h) further extended the duration of antibacterial effects even after a MRSA re-inoculation.

Moreover, we have demonstrated that antibiotic delivery using ECnVs offered prolonged antibacterial effects that were as effective as the liposomal delivery system. As compared to freely applied antibiotic, antibiotic delivery using liposomes has been reported to better inhibit MRSA growth 28-31; moreover, the effectiveness of the liposomes was further enhanced by CMP (=CLP)-collagen tethering. For example, our prior work showed that vancomycin-loaded CMP-modified liposomes tethered into co-gels facilitated the inhibition of MRSA growth for at least 36 h, even after three inoculations, whereas vancomycin-loaded liposome/co-gels lacking CMP only inhibited the MRSA growth for ~26 h 32. Similarly, we have observed a prolonged duration of antibacterial activities against MRSA for at least 18 h using vancomycin-loaded ECnVs tethered into co-gels, as compared to the antibacterial duration of ~ 8 h using a free vancomycin loaded co-gel. However, the duration of antibacterial activities from vancomycin-loaded ECnV-tethered co-gels (at least 18h) was shorter than the duration of effects from vancomycin-loaded, CMP-modified liposome (tethered) co-gels (at least 36 h) 32. This may be due to the different levels of retention of CMP-liposomes (95% after 24 h) vs. ECnVs (60% after 24 h) on co-gels because of differences in the accessibility of the CMP sequences in the CMP-liposome vs. the ECnV. Nevertheless, similar to the liposomal delivery systems, ECnVs improved antibacterial activity, and the duration of effects could be tuned by the level of CLP-collagen tethers.

Altogether, our results demonstrate as a proof-of concept that the combination of peptide-based nanocarriers and their interaction with collagen-containing matrices can be used to manipulate the delivery of vancomycin for its extended efficacy in inhibiting MRSA growth. Non-cytotoxic ECnVs (Fig. S20) improved not only entrapment efficiency of vancomycin but also resulted in release kinetics with via both diffusion and dissolution mechanisms. The ability of ECnVs to be retained on collagen-containing matrices facilitates sustained release of vancomycin and its antibacterial effects against MRSA for a prolonged period. Thus, the delivery of vancomycin with an optimal concentration using ECnV-modified, collagen-based matrices may have potential for the effective treatment of wound infections.

5. Conclusion

To evaluate possible new carriers that could inhibit MRSA-based infections in wounds, we developed a novel antibiotic delivery system using the combination of ECnVs and collagen-containing matrices for the topical delivery of antibiotics with controlled release. This ECM-based material system exploited synergies in peptide nanocarriers and their interactions with collagen-based scaffolds to improve the efficacy of the commercially available antibiotic, vancomycin, and to extend the duration of its antibacterial effects against MRSA after repeated bacterial inoculations. Our system may offer benefits to manage chronic wound infections while stimulating wound-healing potency.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AR067247, R01DK130663, P30GM110758) and the National Science Foundation (IIP1700980, CBET1159466, and CBET1605130) awarded to MOS and KLK. The views expressed here are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leaper D; Assadian O; Edmiston CE, Approach to chronic wound infections. Br J Dermatol 2015, 173 (2), 351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarbrink K; Ni G; Sonnergren H; Schmidtchen A; Pang C; Bajpai R; Car J, Prevalence and incidence of chronic wounds and related complications: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2016, 5 (1), 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan TW; Shih CD; Concha-Moore KC; Diri MM; Hu B; Marrero D; Zhou W; Armstrong DG, Disparities in outcomes of patients admitted with diabetic foot infections. PLoS One 2019, 14 (2), e0211481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leaper D; Assadian O; Edmiston CE, Approach to chronic wound infections. British Journal of Dermatology 2015, 173 (2), 351–358 %@ 0007–0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falcone M; De Angelis B; Pea F; Scalise A; Stefani S; Tasinato R; Zanetti O; Dalla Paola L, Challenges in the management of chronic wound infections. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021, 26, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robson MC, Wound infection. A failure of wound healing caused by an imbalance of bacteria. Surg Clin North Am 1997, 77 (3), 637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eming SA; Martin P; Tomic-Canic M, Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6 (265), 265sr6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastar I; Nusbaum AG; Gil J; Patel SB; Chen J; Valdes J; Stojadinovic O; Plano LR; Tomic-Canic M; Davis SC, Interactions of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in polymicrobial wound infection. PLoS One 2013, 8 (2), e56846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stotts NA, Wound infection: diagnosis and management. Acute and Chronic Wounds-E-Book 2015, 283 %@ 0323316220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipsky BA; Hoey C, Topical antimicrobial therapy for treating chronic wounds. Clin Infect Dis 2009, 49 (10), 1541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White RJ; Cooper R; Kingsley A, Wound colonization and infection: the role of topical antimicrobials. Br J Nurs 2001, 10 (9), 563–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negut I; Grumezescu V; Grumezescu AM, Treatment Strategies for Infected Wounds. Molecules 2018, 23 (9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tavakoli S; Klar AS, Advanced Hydrogels as Wound Dressings. Biomolecules 2020, 10 (8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang Y; He J; Guo B, Functional Hydrogels as Wound Dressing to Enhance Wound Healing. ACS Nano 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Punjataewakupt A; Napavichayanun S; Aramwit P, The downside of antimicrobial agents for wound healing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 38 (1), 39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovering AM; Reeves DS, Antibiotic and Chemotherapy (Ninth Edition). W.B. Saunders: 2011; p Pages 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pray L, Antibiotic resistance, mutation rates and MRSA. Nature Education 2008, 1 (1), 30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HG, E. L. M.; Jones MN;, The adsorption of cationic liposomes to Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 1999, 149 (1–3), 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drulis-Kawa Z; Dorotkiewicz-Jach A, Liposomes as delivery systems for antibiotics. Int J Pharm 2010, 387 (1-2), 187–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez Gomez A; Hosseinidoust Z, Liposomes for Antibiotic Encapsulation and Delivery. ACS Infect Dis 2020, 6 (5), 896–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira M; Pinto SN; Aires-da-Silva F; Bettencourt A; Aguiar SI; Gaspar MM, Liposomes as a Nanoplatform to Improve the Delivery of Antibiotics into Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lankalapalli S; Tenneti V; Nimmali SK, Design and development of vancomycin liposomes. Indian Journal of Pharm Education Research 2015, 49, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z; Ma Y; Khalil H; Wang R; Lu T; Zhao W; Zhang Y; Chen J; Chen T, Fusion between fluid liposomes and intact bacteria: study of driving parameters and in vitro bactericidal efficacy. Int J Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 4025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones MN; Song YH; Kaszuba M; Reboiras MD, The interaction of phospholipid liposomes with bacteria and their use in the delivery of bactericides. J Drug Target 1997, 5 (1), 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scriboni AB; Couto VM; Ribeiro LNM; Freires IA; Groppo FC; de Paula E; Franz-Montan M; Cogo-Muller K, Fusogenic Liposomes Increase the Antimicrobial Activity of Vancomycin Against Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mat Rani NNI; Mustafa Hussein Z; Mustapa F; Azhari H; Sekar M; Chen XY; Mohd Amin MCI, Exploring the possible targeting strategies of liposomes against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2021, 165, 84–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pumerantz AS, PEGylated liposomal vancomycin: a glimmer of hope for improving treatment outcomes in MRSA pneumonia. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov 2012, 7 (3), 205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartomeu Garcia C; Shi D; Webster TJ, Tat-functionalized liposomes for the treatment of meningitis: an in vitro study. Int J Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 3009–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sande L; Sanchez M; Montes J; Wolf AJ; Morgan MA; Omri A; Liu GY, Liposomal encapsulation of vancomycin improves killing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a murine infection model. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012, 67 (9), 2191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang CM; Chen CH; Pornpattananangkul D; Zhang L; Chan M; Hsieh MF; Zhang L, Eradication of drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus by liposomal oleic acids. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (1), 214–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajiahmadi F; Alikhani MY; Shariatifar H; Arabestani MR; Ahmadvand D, The bactericidal effect of lysostaphin coupled with liposomal vancomycin as a dual combating system applied directly on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infected skin wounds in mice. Int J Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 5943–5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thapa RK; Kiick KL; Sullivan MO, Encapsulation of collagen mimetic peptide-tethered vancomycin liposomes in collagen-based scaffolds for infection control in wounds. Acta Biomater 2020, 103, 115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y; Yu SM, Targeting and mimicking collagens via triple helical peptide assembly. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2013, 17 (6), 968–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo T; Kiick KL, Collagen-like peptides and peptide-polymer conjugates in the design of assembled materials. Eur Polym J 2013, 49 (10), 2998–3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urello M; Kiick K; Sullivan M, A CMP-based method for tunable, cell-mediated gene delivery from collagen scaffolds. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2014, 2 (46), 8174–8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thapa RK; Margolis DJ; Kiick KL; Sullivan MO, Enhanced wound healing via collagen-turnover-driven transfer of PDGF-BB gene in a murine wound model. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2020, 3 (6), 3500–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gubernator J; Drulis-Kawa Z; Dorotkiewicz-Jach A; Doroszkiewicz W; Kozubek A, In vitro antimicrobial activity of liposomes containing ciprofloxacin, meropenem and gentamicin against gram-negative clinical bacterial strains. Letters in Drug Design & Discovery 2007, 4 (4), 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kshirsagar NA; Pandya SK; Kirodian GB; Sanath S, Liposomal drug delivery system from laboratory to clinic. J Postgrad Med 2005, 51 Suppl 1, S5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo T; Kiick KL, Noncovalent Modulation of the Inverse Temperature Transition and Self-Assembly of Elastin-b-Collagen-like Peptide Bioconjugates. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137 (49), 15362–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo T; David MA; Dunshee LC; Scott RA; Urello MA; Price C; Kiick KL, Thermoresponsive Elastin-b-Collagen-Like Peptide Bioconjugate Nanovesicles for Targeted Drug Delivery to Collagen-Containing Matrices. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18 (8), 2539–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin J; Luo T; Kiick KL, Self-Assembly of Stable Nanoscale Platelets from Designed Elastin-like Peptide-Collagen-like Peptide Bioconjugates. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20 (4), 1514–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prhashanna A; Taylor PA; Qin J; Kiick KL; Jayaraman A, Effect of Peptide Sequence on the LCST-Like Transition of Elastin-Like Peptides and Elastin-Like Peptide-Collagen-Like Peptide Conjugates: Simulations and Experiments. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20 (3), 1178–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunshee LC; Sullivan MO; Kiick KL, Manipulation of the dually thermoresponsive behavior of peptide-based vesicles through modification of collagen-like peptide domains. Bioeng Transl Med 2020, 5 (1), e10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin J; Sloppy JD; Kiick KL, Fine structural tuning of the assembly of ECM peptide conjugates via slight sequence modifications. Sci Adv 2020, 6 (41). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor PA; Huang H; Kiick KL; Jayaraman A, Placement of Tyrosine Residues as a Design Element for Tuning the Phase Transition of Elastin-peptide-containing Conjugates: Experiments and Simulations. Mol Syst Des Eng 2020, 5 (7), 1239–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plaut RD; Mocca CP; Prabhakara R; Merkel TJ; Stibitz S, Stably luminescent Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains for use in bioluminescent imaging. PLoS One 2013, 8 (3), e59232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmese LL; Fan M; Scott RA; Tan H; Kiick KL, Multi-stimuli-responsive, liposome-crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for drug delivery. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2021, 32 (5), 635–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang Y; Coffin MV; Manceva SD; Chichester JA; Jones RM; Kiick KL, Controlled release of an anthrax toxin-neutralizing antibody from hydrolytically degradable polyethylene glycol hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A 2016, 104 (1), 113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang YX, Engineering polymeric matrices for controlled drug delivery applications: From bulk gels to nanogels. University of Delaware: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen CW; Lu DW; Yeh MK; Shiau CY; Chiang CH, Novel RGD-lipid conjugate-modified liposomes for enhancing siRNA delivery in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 2567–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sekhon UDS; Swingle K; Girish A; Luc N; de la Fuente M; Alvikas J; Haldeman S; Hassoune A; Shah K; Kim Y; Eppell S; Capadona J; Shoffstall A; Neal MD; Li W; Nieman M; Sen Gupta A, Platelet-mimicking procoagulant nanoparticles augment hemostasis in animal models of bleeding. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14 (629), eabb8975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lai VK; Frey CR; Kerandi AM; Lake SP; Tranquillo RT; Barocas VH, Microstructural and mechanical differences between digested collagen-fibrin co-gels and pure collagen and fibrin gels. Acta Biomater 2012, 8 (11), 4031–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai VK; Lake SP; Frey CR; Tranquillo RT; Barocas VH, Mechanical behavior of collagen-fibrin co-gels reflects transition from series to parallel interactions with increasing collagen content. J Biomech Eng 2012, 134 (1), 011004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riau AK; Mondal D; Aung TT; Murugan E; Chen L; Lwin NC; Zhou L; Beuerman RW; Liedberg B; Venkatraman SS; Mehta JS, Collagen-Based Artificial Corneal Scaffold with Anti-Infective Capability for Prevention of Perioperative Bacterial Infections. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2015, 1 (12), 1324–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartinger JM; Lukac P; Mitas P; Mlcek M; Popkova M; Suchy T; Supova M; Zavora J; Adamkova V; Benakova H; Slanar O; Sima M; Bartos M; Chlup H; Grus T, Vancomycin-releasing cross-linked collagen sponges as wound dressings. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2021, 21 (1), 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siddiqui AR; Bernstein JM, Chronic wound infection: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2010, 28 (5), 519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vrignaud S; Benoit JP; Saulnier P, Strategies for the nanoencapsulation of hydrophilic molecules in polymer-based nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (33), 8593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eloy JO; Claro de Souza M; Petrilli R; Barcellos JP; Lee RJ; Marchetti JM, Liposomes as carriers of hydrophilic small molecule drugs: strategies to enhance encapsulation and delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2014, 123, 345–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Q; Li X; Zhao C, Strategies to Obtain Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Small Hydrophilic Molecules. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu L; Ci T; Zhou S; Zeng W; Ding J, The thermogelling PLGA-PEG-PLGA block copolymer as a sustained release matrix of doxorubicin. Biomater Sci 2013, 1 (4), 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramazani F; Chen W; van Nostrum CF; Storm G; Kiessling F; Lammers T; Hennink WE; Kok RJ, Strategies for encapsulation of small hydrophilic and amphiphilic drugs in PLGA microspheres: State-of-the-art and challenges. Int J Pharm 2016, 499 (1-2), 358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sultanova Z; Kaleli G; Kabay G; Mutlu M, Controlled release of a hydrophilic drug from coaxially electrospun polycaprolactone nanofibers. Int J Pharm 2016, 505 (1-2), 133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briuglia ML; Rotella C; McFarlane A; Lamprou DA, Influence of cholesterol on liposome stability and on in vitro drug release. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2015, 5 (3), 231–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fan T; Yu X; Shen B; Sun L, Peptide Self-Assembled Nanostructures for Drug Delivery Applications. Journal of Nanomaterials 2017, 2017, 4562474. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee S; Trinh THT; Yoo M; Shin J; Lee H; Kim J; Hwang E; Lim YB; Ryou C, Self-Assembling Peptides and Their Application in the Treatment of Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20 (23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi P; Aluri S; Lin YA; Shah M; Edman M; Dhandhukia J; Cui H; MacKay JA, Elastin-based protein polymer nanoparticles carrying drug at both corona and core suppress tumor growth in vivo. J Control Release 2013, 171 (3), 330–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jabbari E; Yang X; Moeinzadeh S; He X, Drug release kinetics, cell uptake, and tumor toxicity of hybrid VVVVVVKK peptide-assembled polylactide nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2013, 84 (1), 49–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodriguez-Cabello JC; Arias FJ; Rodrigo MA; Girotti A, Elastin-like polypeptides in drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 97, 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Betre H; Setton LA; Meyer DE; Chilkoti A, Characterization of a genetically engineered elastin-like polypeptide for cartilaginous tissue repair. Biomacromolecules 2002, 3 (5), 910–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adams SB Jr.; Shamji MF; Nettles DL; Hwang P; Setton LA, Sustained release of antibiotics from injectable and thermally responsive polypeptide depots. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2009, 90B (1), 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Subczynski WK; Wisniewska A; Yin JJ; Hyde JS; Kusumi A, Hydrophobic barriers of lipid bilayer membranes formed by reduction of water penetration by alkyl chain unsaturation and cholesterol. Biochemistry 1994, 33 (24), 7670–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nasr G; Greige-Gerges H; Elaissari A; Khreich N, Liposomal membrane permeability assessment by fluorescence techniques: Main permeabilizing agents, applications and challenges. Int J Pharm 2020, 580, 119198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laracuente ML; Yu MH; McHugh KJ, Zero-order drug delivery: State of the art and future prospects. J Control Release 2020, 327, 834–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang YL; Motte S; Kaufman LJ, Pore size variable type I collagen gels and their interaction with glioma cells. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (21), 5678–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moreno-Arotzena O; Meier JG; Del Amo C; Garcia-Aznar JM, Characterization of Fibrin and Collagen Gels for Engineering Wound Healing Models. Materials (Basel) 2015, 8 (4), 1636–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sisakht MM; Nilforoushzadeh MA; Verdi J; Banafshe HR; Naraghi ZS; Mortazavi-Tabatabaei SA, Fibrin-collagen hydrogel as a scaffold for dermoepidermal skin substitute, preparation and characterization. J Contemp Med Sci 2019, 5 (1), 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coradin T; Wang K; Law T; Trichet L, Type I Collagen-Fibrin Mixed Hydrogels: Preparation, Properties and Biomedical Applications. Gels 2020, 6 (4), 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lang NR; Munster S; Metzner C; Krauss P; Schurmann S; Lange J; Aifantis KE; Friedrich O; Fabry B, Estimating the 3D pore size distribution of biopolymer networks from directionally biased data. Biophys J 2013, 105 (9), 1967–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang F; Zhou H; Olademehin OP; Kim SJ; Tao P, Insights into Key Interactions between Vancomycin and Bacterial Cell Wall Structures. ACS Omega 2018, 3 (1), 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Creech CB; Al-Zubeidi DN; Fritz SA, Prevention of Recurrent Staphylococcal Skin Infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015, 29 (3), 429–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frykberg RG; Banks J, Challenges in the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015, 4 (9), 560–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bertazzoni Minelli E; Benini A; Magnan B; Bartolozzi P, Release of gentamicin and vancomycin from temporary human hip spacers in two-stage revision of infected arthroplasty. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004, 53 (2), 329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang L; Yan J; Yin Z; Tang C; Guo Y; Li D; Wei B; Xu Y; Gu Q; Wang L, Electrospun vancomycin-loaded coating on titanium implants for the prevention of implant-associated infections. Int J Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 3027–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stravinskas M; Nilsson M; Vitkauskiene A; Tarasevicius S; Lidgren L, Vancomycin elution from a biphasic ceramic bone substitute. Bone Joint Res 2019, 8 (2), 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Abdel-Rahman LM; Eltaher HM; Abdelraouf K; Bahey-El-Din M; Ismail C; Kenawy E-RS; El-Khordagui LK, Vancomycin-functionalized Eudragit-based nanofibers: Tunable drug release and wound healing efficacy. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2020, 58, 101812. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krishnan AG; Biswas R; Menon D; Nair MB, Biodegradable nanocomposite fibrous scaffold mediated local delivery of vancomycin for the treatment of MRSA infected experimental osteomyelitis. Biomater Sci 2020, 8 (9), 2653–2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Singh S; Alrobaian MM; Molugulu N; Agrawal N; Numan A; Kesharwani P, Pyramid-Shaped PEG-PCL-PEG Polymeric-Based Model Systems for Site-Specific Drug Delivery of Vancomycin with Enhance Antibacterial Efficacy. ACS Omega 2020, 5 (21), 11935–11945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.