Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common primary hepatic malignancies. E2F transcription factors play an important role in the tumorigenesis and progression of HCC, mainly through the RB/E2F pathway. Prognostic models for HCC based on gene signatures have been developed rapidly in recent years; however, their discriminating ability at the single-cell level remains elusive, which could reflect the underlying mechanisms driving the sample bifurcation. In this study, we constructed and validated a predictive model based on E2F expression, successfully stratifying patients with HCC into two groups with different survival risks. Then we used a single-cell dataset to test the discriminating ability of the predictive model on infiltrating T cells, demonstrating remarkable cellular heterogeneity as well as altered cell fates. We identified distinct cell subpopulations with diverse molecular characteristics. We also found that the distribution of cell subpopulations varied considerably across onset stages among patients, providing a fundamental basis for patient-oriented precision evaluation. Moreover, single-sample gene set enrichment analysis revealed that subsets of CD8+ T cells with significantly different cell adhesion levels could be associated with different patterns of tumor cell dissemination. Therefore, our findings linked the conventional prognostic gene signature to the immune microenvironment and cellular heterogeneity at the single-cell level, thus providing deeper insights into the understanding of HCC tumorigenesis.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, prognosis, overall survival, immune microenvironment, cellular heterogeneity

Abbreviations: CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MAIT, mucosal-associated invariant T cells

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most prevalent type of primary liver cancer, accounts for up to 90% of all liver cancers (1). It typically develops on a background of chronic liver inflammation or cirrhosis, with hepatitis B viral infections being the primary risk factor for its development (2). Although great efforts have been made in the early diagnosis and treatment methods of HCC, the prognosis of patients with HCC still requires much more improvement. In addition, the current TNM staging system and other traditional clinical models may be useful for prognostic assessment but are still not ideally accurate in the grading of patients for surgical treatments. Over the past decade, immunotherapeutic approaches have changed the landscape of clinical decision-making for patients with HCC, albeit with rather suboptimal response rates (3, 4). The high heterogeneity at the cellular and molecular levels may pose a considerable obstacle to improving the therapeutic efficacy of HCC. Although diverse predictive models for prognosis are capable of classifying patients into different risk groups, which corroborates interpatient heterogeneity, the factors underlying the discriminative effects of these models in single-cell level have not been studied. Moreover, exploring the tumor microenvironment and dissecting the developmental dynamics of immune cells are pivotal for understanding the heterogeneous pattern of antitumor immune responses in patients with HCC. Single-cell sequencing methods have emerged as cutting-edge techniques for analyzing the complex tumor ecosystem and characterizing immune microenvironmental patterns, and several previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of investigating the tumor immune phenotypes at a single-cell resolution for HCC (5, 6, 7).

Unlike cells in other organs or tissues that are regenerated by stem cells, hepatocytes are characterized by an impressive ability to maintain their remarkable proliferative potential, which compensates for cell loss or responds to hyperplasia (8). Members of the E2F transcription factor family are important in the regulation of hepatocyte proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis in collaboration with cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and the RB family of proteins (9, 10, 11, 12, 13). As previously demonstrated, dysfunction of the CDK-RB-E2F axis would lead to an aberrant cell cycle and the inhibition of apoptosis, and thus initiating pathological processes of HCC (10, 14, 15). Aberrant expression of E2F family members is reported to be associated with poor survival and could be used to predict the prognosis of several tumor types (16, 17, 18).

Here, we aim to develop and validate a prognostic signature with E2F genes that play essential roles in the oncogenic processes of HCC. In addition, we intended to identify distinct subpopulations of T cells by applying the E2F signature on a single-cell transcriptome profile (5). We sought to delineate the differential cell composition, nonnegligible transcriptional heterogeneity, and inconsistent cell fate decisions between different subpopulations of infiltrating T cells. In addition, we demonstrated a specific population of CD8+ T cells with prominently elevated cell adhesion, potentially resulting in a more effective inhibition of tumor dissemination than other cells. Our study provides novel insights into the underlying biology of varying clinical outcomes at the single-cell level and dissects intricate admixtures of immune cell populations, providing a new lens on the determinants of molecular and phenotypic heterogeneity in HCC biology.

Results

Essential role of the E2F regulators in HCC and the E2F predictive model of survival for patients with HCC

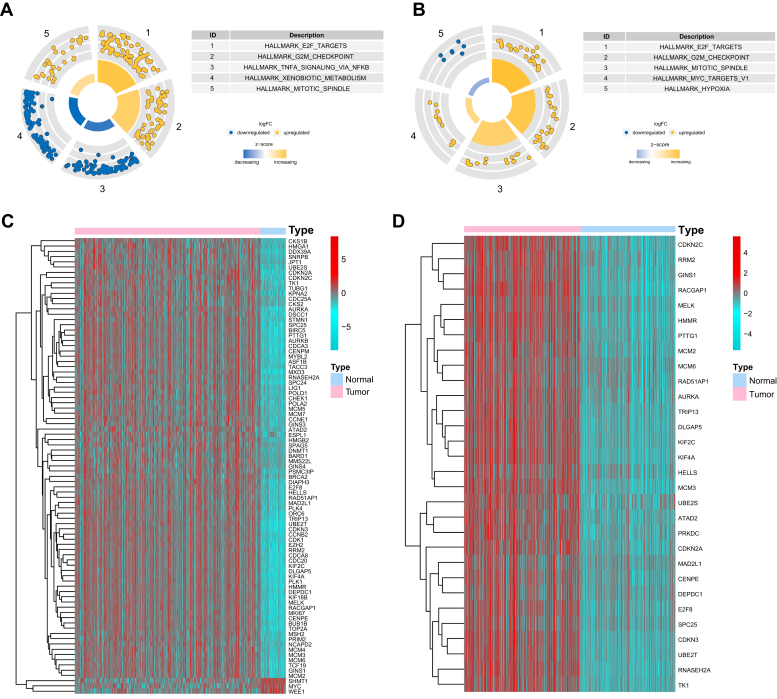

To comprehensively identify essential regulatory factors that orchestrate the transcriptional architecture of HCC, we carried out differential gene expression analyses on the Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA LIHC) data set and integrated gene data set from four GEO expression profiles (Tables S1 and S2). Gene set enrichment analysis on both data sets revealed that the most enriched pathway for transcriptional activities in HCC was ascribed to E2F-target genes (Fig. 1), indicating that the proper combination of the E2F transcription factors might be promising in constructing the prognostic model of HCC (19). To confirm our hypothesis, additional enrichment analysis was performed using databases of KEGG, Reactome, and Pathway Interaction Database, and revealed E2F pathway or cell cycle pathway was ranked among the top five enriched pathways (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

E2F transcription factors are essential regulators in HCC.A and B, gene set enrichment analysis showed the five most enriched biological processes for the differentially expressed genes in the TCGA cohort (A) and the combined GEO cohort (B). C and D, differential expression of E2F-target genes in the TCGA cohort (C) and the integrated GEO cohort (D).

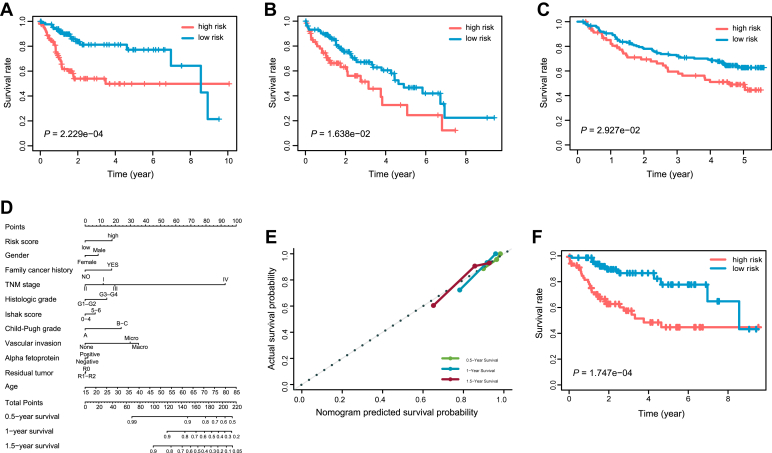

Based on the expression data and clinical information from the TCGA LIHC cohort, we applied a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis on the E2F family members. After conducting a stepwise multivariate Cox analysis on the training cohort, E2F2 and E2F5 were identified to be significantly correlated with poor survival of the patients with HCC (Table S3). Within the prognostic signature, a risk score was calculated for each patient according to the expression level and the corresponding regression coefficient of E2F2 and E2F5. Based on the median risk score for the training cohort, the patients with HCC were categorized into high- and low-risk groups. We observed that patients in the low-risk group exhibited remarkably longer overall survival (OS) compared with high-risk patients in the TCGA training (p = 2.229e-04, Fig. 2A) and validation cohorts (p = 1.638e-02, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Performance of the predictive gene signature.A–C, Kaplan–Meier survival curves for comparison of the overall survival rates between patients in the low-risk group and the high-risk group for the TCGA training cohort (A), the TCGA validation cohort (B), and the external validation cohort from an independent GEO dataset (C). D, the nomogram predicting the 0.5-, 1-, and 1.5-year overall survival probability of the patients with HCC was created by integrating the gene signature with common clinical features. E, the calibration plot showing the predicted and the actual observed survival rates for patients with HCC at the 0.5-, 1-, and 1.5-year time points. F, survival curves of the nomogram in predicting overall survival probabilities for patients with HCC.

Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves were applied to evaluate the predicting capacity of the two-E2F prognostic signature. Area under the curve (AUC) yielded by the prognostic signature at 0.5-, 1-, and 1.5-year survival prediction was 0.768, 0.749, and 0.741, respectively, for the TCGA training cohort (Fig. S2A). The prediction efficiency of the prognostic signature for the whole TCGA cohort was confirmed with the AUC values of 0.675, 0.703, and 0.702 for 0.5-, 1- and 1.5-year OS, respectively (Fig. S2B). In addition, it was reassuring to note that the E2F gene signature was able to robustly stratify patients into high- and low-risk groups for OS rates in an external validation cohort (GSE14520, n = 222, Fig. 2C). These findings demonstrated the effectiveness of the E2F signature in predicting unfavorable prognosis for patients with HCC.

The prognostic risk score showed independence of conventional clinicopathological parameters

To further evaluate the potential of the E2F prognostic signature, we investigated the relationship between the risk level and the potential clinical outcomes by using the whole set of 339 TCGA patients. We found that a significant difference exists in several clinicopathological factors, such as TNM stage, histologic grade, Ishak score, Child–Pugh grade, vascular invasion, and the serum alpha fetoprotein between the two risk groups. However, the risk score was not significantly associated with age, gender, and family history of cancer (Table 1). We next performed a Cox regression analysis on the E2F signature-derived risk score incorporating the commonly used clinicopathologic parameters. Multivariate Cox analysis included only the features that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis of patients with HCC (Table 2).

Table 1.

Association between the risk score derived from the prognostic signature and the common clinicopathological factors

| Variables | Total (N = 339) | Risk score |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (N = 147) | Low (N = 192) | |||

| Age (year) | ||||

| <65 | 208 (61.4%) | 97 (66.0%) | 111 (57.8%) | 0.156 |

| ≥65 | 131 (38.6%) | 50 (34.0%) | 81 (42.2%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 231 (68.1%) | 100 (68.0%) | 131 (68.2%) | 1 |

| Female | 108 (31.9%) | 47 (32.0%) | 61 (31.8%) | |

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| NO | 196 (57.8%) | 92 (62.6%) | 104 (54.2%) | 0.0697 |

| YES | 98 (28.9%) | 33 (22.4%) | 65 (33.9%) | |

| Unknown | 45 (13.3%) | 22 (15.0%) | 23 (12.0%) | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I | 170 (50.1%) | 63 (42.9%) | 107 (55.7%) | 0.0155 |

| II | 84 (24.8%) | 40 (27.2%) | 44 (22.9%) | |

| III | 81 (23.9%) | 44 (29.9%) | 37 (19.3%) | |

| IV | 4 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Histologic grade | ||||

| G1–G2 | 212 (62.5%) | 75 (51.0%) | 137 (71.4%) | <0.001 |

| G3–G4 | 125 (36.9%) | 70 (47.6%) | 55 (28.6%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ishak score | ||||

| 0–4 | 124 (36.6%) | 46 (31.3%) | 78 (40.6%) | <0.001 |

| 5–6 | 74 (21.8%) | 22 (15.0%) | 52 (27.1%) | |

| Unknown | 141 (41.6%) | 79 (53.7%) | 62 (32.3%) | |

| Child–Pugh grade | ||||

| A | 207 (61.1%) | 80 (54.4%) | 127 (66.1%) | 0.0193 |

| B–C | 21 (6.2%) | 7 (4.8%) | 14 (7.3%) | |

| Unknown | 111 (32.7%) | 60 (40.8%) | 51 (26.6%) | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| None | 193 (56.9%) | 73 (49.7%) | 120 (62.5%) | 0.00389 |

| Micro | 84 (24.8%) | 35 (23.8%) | 49 (25.5%) | |

| Macro | 14 (4.1%) | 7 (4.8%) | 7 (3.6%) | |

| Unknown | 48 (14.2%) | 32 (21.8%) | 16 (8.3%) | |

| Alpha fetoprotein | ||||

| Negative | 143 (42.2%) | 42 (28.6%) | 101 (52.6%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 120 (35.4%) | 66 (44.9%) | 54 (28.1%) | |

| Unknown | 76 (22.4%) | 39 (26.5%) | 37 (19.3%) | |

| Residual tumor | ||||

| R0 | 301 (88.8%) | 123 (83.7%) | 178 (92.7%) | 0.0303 |

| R1–R2 | 12 (3.5%) | 7 (4.8%) | 5 (2.6%) | |

| Unknown | 26 (7.7%) | 17 (11.6%) | 9 (4.7%) | |

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival

| Variables | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (≥65 versus <65) | 1.23 (0.85, 1.78) | 0.273 | - | - |

| Gender (Female versus Male) | 1.26 (0.87, 1.84) | 0.228 | - | - |

| Family history of cancer (YES versus NO) | 1.14 (0.76, 1.69) | 0.530 | - | - |

| TNM stage (II versus I) | 1.42 (0.87, 2.32) | 0.160 | 1.23 (0.66, 2.3) | 0.507 |

| TNM stage (III versus I) | 2.72 (1.78, 4.15) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.24, 3.59) | 0.006 |

| TNM stage (IV versus I) | 5.44 (1.68, 17.63) | 0.005 | 7.3 (2.19, 24.35) | 0.001 |

| Histologic grade (G3–G4 versus G1–G2) | 1.14 (0.78, 1.67) | 0.489 | - | - |

| Ishak score (5–6 versus 0–4) | 0.87 (0.5, 1.5) | 0.612 | - | - |

| Child–Pugh grade (B–C versus A) | 1.66 (0.82, 3.36) | 0.159 | - | - |

| Vascular invasion (micro versus none) | 1.16 (0.72, 1.88) | 0.539 | 0.97 (0.56, 1.69) | 0.914 |

| Vascular invasion (macro versus none) | 2.52 (1.14, 5.58) | 0.023 | 1.87 (0.82, 4.27) | 0.135 |

| Alpha fetoprotein (positive versus negative) | 1.45 (0.92, 2.28) | 0.108 | - | - |

| Residual tumor (R1–R2 versus R0) | 1.17 (0.43, 3.2) | 0.754 | - | - |

| Risk score (high versus low) | 2.17 (1.5, 3.15) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.19, 2.9) | 0.007 |

p < 0.05 are highlighted in bold.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

To provide a clinically adaptable approach to quantifying the risk assessment for patients with HCC, we developed a nomogram integrated with the E2F signature and the commonly used clinicopathologic risk factors in the entire TCGA samples dataset (Fig. 2D). We calculated the C-statistic discriminatory index (C-index) and the calibration plot to assess the prognostic performance of the nomogram. As shown in the calibration plot, there was excellent concordance between the predicted outcomes and the observed 0.5-, 1-, and 1.5-year OS (Fig. 2E). Moreover, the C-index for the nomogram was 0.74 (95% confidence interval: 0.70–0.79). Time-dependent C-index and AUC value of the nomogram showed stability of the discriminative power (Table S4 and Fig. S3A). Results of the internal correction with bootstrap analysis were also demonstrated (Fig. S3B and Table S5). Since covariate adjustment is of vital importance in the evaluation of the discriminative power of prognostic model, the adjusted C-index and a more direct estimator, D-index, were both calculated to provide supporting evidence for the discrimination ability of the model (Table S6) (20). Neither the adjusted C-index nor the adjusted D-index differed greatly from the original values.

In addition, a Kaplan–Meier analysis based on the median risk score derived from the nomogram integrating the two-E2F signature and the clinicopathologic features was carried out to measure the discriminatory power of this nomogram. The patients being labeled as high-risk exhibited significantly poorer prognosis than the low-risk patients (Fig. 2F). These findings demonstrated the validity of our E2F signature in combination with the commonly used clinicopathologic factors in predicting survival outcomes for patients with HCC.

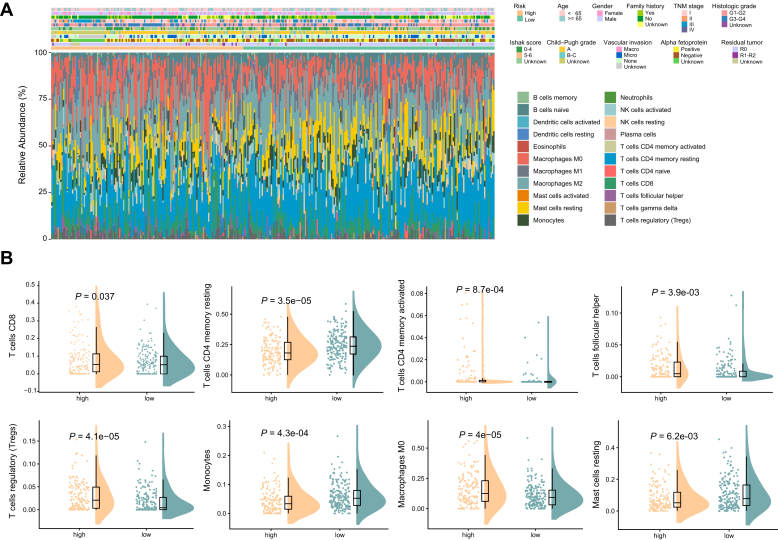

Estimation of immune infiltration levels for patients in different risk groups from bulk sequencing data

To elucidate the differences of immune microenvironments between high- and low-risk groups, we applied the CIBERSORT algorithm to infer the fraction of different types of immune cells using the TCGA cohort expression data. The immune cell distribution was calculated based on a matrix of 22 immune cell type signatures (LM22) and compared between high- and low-risk patients with HCC (Fig. 3A). The proportions of tumor-infiltrating macrophages M0 and Tregs were significantly higher in the high-risk patients with HCC than those in the low-risk group, while the low-risk patients had markedly higher proportions of resting memory CD4+ T cells than the high-risk patients with HCC (Fig. 3B). However, the expression of macrophages M2 (tumor-associated macrophages) did not show significant differences in expression level between high-risk and low-risk patients. Correlation analysis between different subsets of immune cells was performed. The expression of T cells CD8 was positively correlated with the expression of T cells CD4 memory activated (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.45, p < 2.20e-16), while expression of mast cells resting was negatively correlated with T cells regulatory (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.33, p = 2.50e-10) (Fig. S4). These results highlighted a potential mechanistic link between the heterogeneous immune infiltration status across different patients with HCC and variable clinical manifestations.

Figure 3.

Deconvolution of bulk sequencing data showed the immune cell infiltration landscape in patients with HCC from the high-risk and low-risk groups.A, distribution in fractions of diverse tumor infiltrating immune cells in high-risk and low-risk patients with HCC. B, comparisons of the proportions of different tumor infiltrating immune cells between the high-risk and low-risk patients. Only the comparisons with statistical significance were visualized.

Efficacy of the predictive signature in discriminating cell types using single-cell transcriptomic profiles

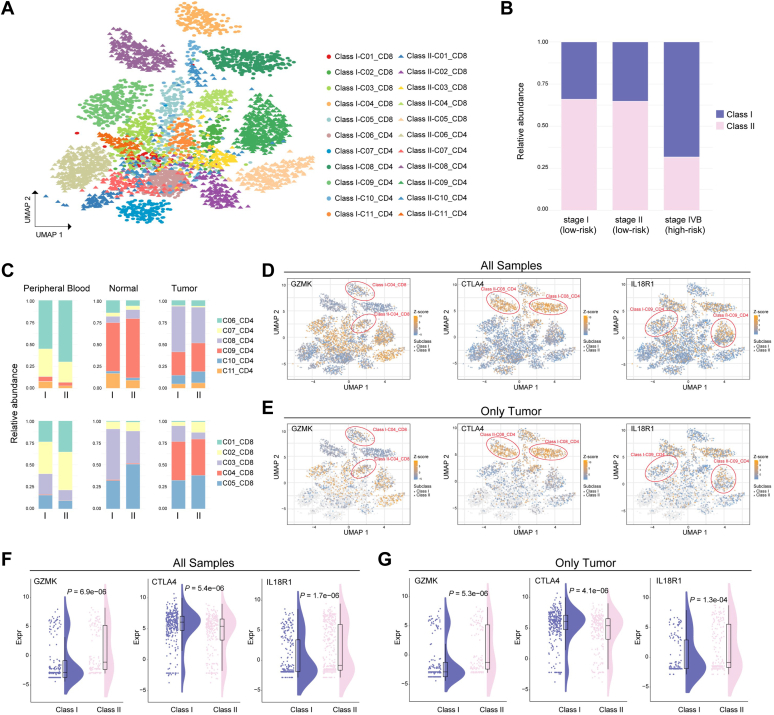

Deconvolution of bulk transcriptomes implemented with CIBERSORT showed remarkable intertumoral immune cell heterogeneity between patients from different risk groups. It is possible that the gene signature developed initially to stratify patients with HCC with different outcome risk could discriminate infiltrating T cells in the tumor microenvironment. To validate this hypothesis, we extended the gene signature on a published single-cell RNA sequencing dataset with 4070 T-cell samples of six patients with HCC (5), with the classification being applied to single-cell objects instead of traditional patient samples (Fig. 4A). We subcategorized the infiltrating T cells into two classes (classes I and II) based on the E2F signature (Fig. 4, A and B) (5). Surprisingly, we observed that patients with late-stage HCC exhibited a significantly higher abundance of class I cells than patients from other stages (Fig. 4B, p = 2.12e-100, chi-square test). We also investigated the risk groups of patients assigned by the predictive signature. We found that patients diagnosed as stages I and II were classified into the low-risk group, while patients diagnosed as stage IVB were classified into the high-risk group (Table S7), showing the concordant classification between risk groups and diagnostic stages. Considering the relatively unexplored roles of E2F6 and E2F7 in the pathogenesis of HCC, we specifically compared the expression level of E2F6 and E2F7 between class I and class II cells among patients from different disease stages (Fig. S5). Interestingly, we observed that, in patients with late-stage HCC, the E2F7 gene showed significant differential expression between class I and class II cell populations, while a modestly significant difference of expression was found in stage II patients. We did not observe any significant difference of expression levels between class I and class II cells across different disease stages for the E2F6 gene (Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

Discriminating T-cell populations based on single-cell RNA sequencing profiles.A, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot displaying 22 T-cell subpopulations identified by the predictive gene model based on the existing 11 clusters. Each dot represents one single cell. The existing 11 clusters: C01_CD8, naive CD8+ T cells; C02_CD8, effector CD8+ T cells; C03_CD8, mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT); C04_CD8, exhausted CD8+ T cells; C05_CD8, intermediate state CD8+ T cells between effector and exhausted CD8+ T cells; C06_CD4, naive CD4+ T cells; C07_CD4, peripheral T regulatory cells (Tregs); C08_CD4, tumor Tregs; C09_CD4, mixed state cells; C10_CD4, exhausted CD4+ T cells; C11_CD4, cytotoxic CD4+ T cells. B, the proportions of class I and class II subpopulations in each stage of the patients with HCC. C, the proportions of each T-cell type between the class I and class II populations across peripheral blood, tumor, and adjacent normal tissues. D, UMAP plot of all T cells from peripheral blood and normal and tumor tissues, with all cells colored according to the gene expression of GZMK, CTLA4, and IL18R1, respectively. The two cell subpopulations between which the respective gene was differentially expressed were marked with red circles. E, UMAP plot of all T cells, with only tumor cells colored according the gene expression of GZMK, CTLA4, and IL18R1, respectively. Nontumor cells were colored gray. The two cell subpopulations between which the respective gene was differentially expressed were marked with red circles. F, differential expression of GZMK, CTLA4, and IL18R1 in all cell samples of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. G, differential expression of GZMK, CTLA4, and IL18R1 in tumor cell samples of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

The composition of immune cells varied spatially between classes I and II for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4C). Cells from the first CD8+ T-cell cluster (C01_CD8) were characterized as naive CD8+ T cells. Cells from the first CD4+ T-cell cluster (C06_CD4) were characterized as naive CD4+ T cells. These were both more abundant in peripheral blood samples than samples from tumor and normal tissues. The class II cells harbored higher abundances of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells than the class I cells. In tumor tissues, the effector CD8+ T cells, C02_CD8, were more prevalent in the class II than in the class I group, while the tumor Tregs (C08_CD4) were higher in class I subpopulations. For both classes I and II, the exhausted T cells (C04_CD8 and C10_CD4) were more abundant in tumor tissues than in peripheral blood and adjacent normal tissues. In addition, the fraction of mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells (C03_CD8) was higher in class I than in class II among all peripheral blood, normal, and tumor cell samples. Within the exhausted CD8+ T cells, we observed the expression levels of cytotoxic effector GZMK was markedly lower in class I subpopulations than in class II subpopulations not only for tumor cell samples but also for T cells from all three locations (Fig. 4, D–G). As a well-established exhaustion marker and immune checkpoint molecule, CTLA4 exhibited significantly higher expression levels in class I tumor Tregs than in class II tumor Tregs (Fig. 4, D–G). Interestingly, among cells in the C09_CD4 cluster, which were cells primarily in an intermediate state between cytolytic and suppressive T cells, we observed significantly lower expression levels of IL18R1 in class I subpopulations than in the class II group (Fig. 4, D–G), which might be associated with the process of transition to exhausted T cells (21, 22).

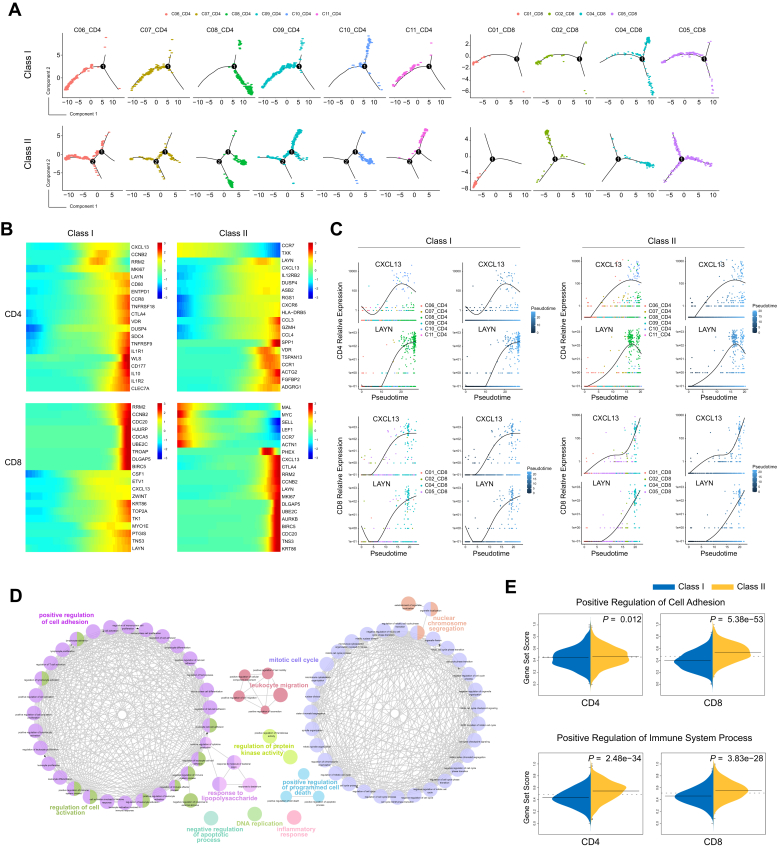

Distinct cell fates revealed between class I and class II subpopulations

To further explore the developmental fates of class I and II cells, next we performed pseudotime analyses using Monocle (23) to infer the dynamic cell states and immune cell transitions for both subclasses in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. For CD8+ T cells, we excluded the MAIT cells because of their distinct characteristics of T-cell receptors (5). Our results showed that class I and II subpopulations exhibited different developmental trajectories and cell type distributions for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figs. 5A and S6). We observed that the trajectory path of class I subpopulations in CD4+ cells contained only one branch point while the trajectory path of class II subpopulations from naive to exhausted CD4+ T cells contained two branch points. The class I subpopulations of naive and cytotoxic CD4+ T cells (class I-C06_CD4 and class I-C11_CD4) overlapped extensively and resided mostly at the beginning state of the pseudotime path (Fig. 5A, upper left), whereas the developmental fates of these two cell types differed markedly in class II CD4+ subpopulations, with the cytotoxic subpopulations (class II-C11_CD4) localized mainly at a distal branch (Fig. 5A, lower left). For CD8+ T cells, the class II subpopulations with an intermediate status between effector and exhausted phenotypes (class II-C05_CD8) distributed uniformly along pseudotime and overlapped with the exhausted CD8+ T cells (class II-C04_CD8) along the trajectory path, especially at the terminal state (Fig. 5A, lower right). Unlike the class II subpopulations, when the trajectory bifurcated into two branches in class I subpopulations, the class I-C05_CD8 cells within the intermediate state almost disappeared and the two branches generated after the developmental branch point were enriched for exhausted CD8+ T cells (class I-C04_CD8), which emerged earlier than those in class II subpopulations (Fig. 5A, upper right).

Figure 5.

Different developmental cell fates between the class I and class II cells.A, faceted pseudotime plot according to T-cell types for the class I and class II subpopulations. B, heatmap plot for the expression of the 20 most dynamic genes along pseudotime for class I and class II subpopulations. C, the dynamic expression patterns of the marker genes CXCL13 and LAYN in class I and class II subpopulations. D, Gene Ontology results showed the biological processes that associated with the significantly dynamic genes from the branch-dependent expression analysis. Each node represents an enriched Gene Ontology term. E, single sample gene set enrichment analysis results for comparing the expression of the dynamic genes during branch evolution for the “Positive Regulation of Cell Adhesion” term and the “Positive Regulation of Immune System Process” term.

We then explored the transcriptional changes along the pseudotime trajectory and identified genes that were significantly dynamic during the differentiation processes (Fig. 5B). The osteopontin protein encoded by the SPP1 gene, ranked as the most significantly associated factor with the class II CD4+ T cells and upregulated prominently at the terminal state (Tables S8–S11 and Fig. S7), has been demonstrated to be a potential driver of tumor cell biodiversity (6). Among each set of the top 20 genes that were significantly associated with the transitional states along pseudotime, the T-cell recruitment chemokine CXCL13 and layilin (LAYN) were common genes for all four subpopulations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5, B and C). CXCL13 serves as an exhaustion marker and is also a crucial factor involved in the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures. The secretion of CXCL13 has been shown to participate in the exhaustion of CD4+ T cells and the progression of CD8+ T cells toward late dysfunctionality (24). CXCL13 exhibited similar expression patterns in class I and II CD4+ T cells, whereas the Treg and exhaustion marker LAYN showed a differential trend, with a modest upregulation observed at the terminal end of the trajectory in class I CD4+ T cells compared with the noticeable reduction in the class II CD4+ subpopulation (Fig. 5C). We also observed that, within the class II subpopulations of the CD8+ T cells, the expression of CXCL13 increased dramatically at the end stage of the trajectory, corresponding to the exhausted cell state after a relatively steady phase of the intermediate cell state. Unlike CXCL13, which has a stationary point, the consistently elevated expression of LAYN was observed for the whole differentiation processes of the class II CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5C). As a suppressive marker, LAYN also showed a powerful capacity for discriminating patients with HCC with different survival outcomes (5). Interestingly, we found substantial overlap between top-ranked genes of class I and II CD8+ T cells, such as cell cycle–regulated molecules RRM2, CCNB2, UBE2C, DLGAP5, CDC20, and BIRC5, as well as the cell adhesion protein TNS3 (Fig. 5B and Tables S8–S11). The cell-cycle genes showed similar patterns of expression in class I and II CD8+ T cells, whereas TNS3, CXCL13, and LAYN exhibited inconsistent trend during the differentiation processes (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the adhesion and migration levels could differ between the class I and II CD8+ T cells (25, 26, 27).

To further delineate the processes represented by the developmental trajectory, we then carried out a branch expression analysis to identify the branch-dependent transcriptional and functional differences between the two subpopulations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. S8 and Tables S12–S16). We explored the genes that were significantly associated with each cell fate decision point for the subpopulations in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and found that the top 100 genes responsible for the cell fate decisions were overrepresented by several important biological processes, including the positive regulation of cell adhesion and mitotic cell cycle (Fig. 5D and Table S17). To investigate whether a similar profile of genes exerted different effects in developmental fate decisions among different cell subpopulations, we carried out a single sample gene set enrichment analysis to compare transcriptional activities between class I and II subpopulations. We observed that the gene set scores were remarkably higher in the class II-CD8 subpopulation than in the class I-CD8 subpopulation for the “Positive Regulation of Cell Adhesion” and “Positive Regulation of Immune System Process” categories (Fig. 5E), suggesting that the class II-CD8 cells may represent a T-cell subset with a higher cytotoxicity than the class I-CD8 cells. In addition, the cell-cycle genes showed a significantly higher enrichment score in class I subpopulations for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. S9), supporting the role of tumor microenvironmental reprogramming in cell-cycle perturbation (28).

Discussion

During the progression of the cell cycle, the regulation of cell proliferation involves a cascade of molecular interactions associated with genome stability, DNA repair, and chromatin regulation (29). Mechanistic studies have exposed a pivotal role for the CDK-RB-E2F axis in the maintenance of genomic integrity and cell homeostasis, as well as in responding to DNA damage and stress (30, 31, 32, 33). The CDK inhibitors have long been regarded as promising targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer, mediating the phosphorylation and activation of RB proteins and thereby enabling the release of E2F transcription factors that regulate a plethora of genes required for DNA synthesis and chromosome stability during cell-cycle progression (34, 35, 36, 37). An unequivocal consensus has been reached on the central role of the CDK-RB-E2F pathway in cancer (38, 39). The E2Fs represent a crucial group of transcriptional regulators that are involved in cell-cycle control and consists of nine different gene products encoded by eight chromosomal loci. Based on in vitro structural studies, the E2F family members have been artificially subdivided into three categories according to the sequence homology and protein function (40, 41), although challenged by in vivo studies as being a gross oversimplification (42, 43). While the precise mechanisms remain unclear and warrant further research, dysregulated functions of the E2F family members and/or the target genes associated with apoptosis, metabolism, or angiogenesis have been linked to poor outcomes in cancers (12, 16, 17, 18). In this study, we established a prognostic signature based on the expression profiles of the E2F transcription factors that could stratify patients with HCC into different risk groups. Patients classified into the high-risk group exhibited significantly more unfavorable prognosis than the low-risk patients. As the component genes in the signature, E2F2 and E2F5 may act in combination to coordinate a series of cellular processes involved in cancer aggressiveness.

E2F2 is traditionally classified as an activator, and it has been reported that the E2F2 gene plays a pivotal role in liver regeneration, the absence of which results in the deregulation of S-phase entry and inhibition of hepatocytes proliferation in mice (44). Previous studies have demonstrated the contributory role of E2F2 upregulation in the development of breast cancer, owing to the enrichment of its target genes related to angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling (45). Furthermore, E2F2 also possesses proapoptotic functions during DNA damage (46). In HCC, there has been evidence suggesting that the downregulation of E2F2 could result in the inhibition of hepatocyte proliferation and prevention of cell progression (47). Rather than being a traditionally acknowledged activator as E2F2, E2F5 has been grouped into the repressor group based on previous in vitro studies (42, 48). It has been demonstrated that the proliferation and migration of cells in breast cancer can be inhibited by decreasing the transcriptional output of E2F5 through a microRNA-dependent mechanism (49). In addition, E2F5 was also found to be substantially overexpressed in glioblastoma and prostate cancer (50, 51). Furthermore, several studies have sought to explore the relationship between E2F5 and HCC and showed that the dysregulation of E2F5 expression was associated with the process of tumor development (52, 53).

During the process of tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth, a disturbed immune microenvironment could be involved in promoting tumoral immune escape (54). Immune microenvironment heterogeneity can lead to unresponsiveness and treatment resistance in conventional chemotherapy and targeted immunotherapy (55). Therefore, understanding the cellular and molecular heterogeneity of tumor infiltrating cells from a different perspective may be of crucial importance for making improvements in diagnosis and treatment. Developing gene signatures have been applied widely and evolved rapidly for predicting the prognosis of patients. Our study built and validated a prognostic gene signature based on E2F transcription factors owing to their essential role in HCC as well as in the cell cycle (14, 19). We noted that Huang et al. (56) performed multivariate analysis integrating E2Fs and several clinical parameters and found E2F5 and E2F6 were independent predictive factors corroborating the role of E2Fs in HCC etiology. Notably, the results from Huang et al. (56) does not contradict ours because we built the gene signature merely based on the E2Fs without clinical parameters. Besides, the performance of the combination of E2F5 and E2F6 in predicting the clinical outcomes of patients with HCC was not shown.

Our study focused on the delineation of cellular and molecular heterogeneity from the perspective of a prognostic gene signature and attempted to unveil key determinants underlying the capability of the predictive gene signature, although perhaps not the one with the best performance, which requires further study to be identified. The single cells harbored by patients with high expression of the gene signature did not necessarily all show high gene signature expression. However, the presence of enough single cells with high signature expression caused the corresponding patient to be identified as having a high expression of the gene signature and classified as having a high risk of poor survival. The results of our study linked patient prognosis to intratumoral cellular and molecular heterogeneity, highlighted the distinct cell populations in patients across different disease stages, and revealed specific subpopulations of CD8+ T cells exhibiting differential cell adhesion level, which might result in different tumor dissemination patterns. Investigations on interpatient heterogeneity and a more comprehensive characterization of cell populations, especially those incorporating transcriptome profiles, clinical information, and single-cell data from the same group of individuals will be conducted in future studies.

Experimental procedures

Differential gene expression analysis

Differential gene expression analyses were performed on the TCGA LIHC and integrated GEO datasets. In the TCGA cohort, we included 369 patients with HCC and 50 normal control samples. Four independent microarray studies (GSE76427 [n = 167, 115 cases and 52 controls], GSE136247 [n = 69, 39 cases and 30 controls], GSE107170 [n = 278, 119 cases and 159 controls], and GSE102079 [n = 257, 152 cases and 105 controls]) were collected from the GEO database to generate two integrated profiles, including cohorts of HCC samples and normal controls. The batch effects from different studies were mitigated using the ComBat method implemented in the R sva package (57). The limma package was applied to calculate the fold changes of genes between HCC samples and normal controls, and genes with adjusted p value <0.05 and fold change >2 were identified as differentially expressed genes. Gene set enrichment analyses were performed on the differentially expressed genes using the hallmark gene set collection from the Molecular Signatures Database, KEGG, Reactome, and Pathway Interaction Database (58, 59, 60, 61).

Construction of the prognostic signature

The level III transcriptome profiles, including mRNA-seq data of 369 patients with HCC and the corresponding clinical information from the TCGA LIHC dataset were used to build and validate the prognostic signature. The clinical parameters of age, gender, family history of cancer, pathologic stage, histologic grade, Ishak fibrosis score, Child–Pugh grade, vascular invasion, alpha fetoprotein outcome, and residual tumor were evaluated in this study. After removing samples with incomplete survival information, 339 patients with HCC were retained for subsequent analysis. The patients with HCC were randomly assigned to a training set or a validation set at a ratio of 1:1 (n = 171 and n = 168 for training and validation sets).

To establish a clinically translatable prognostic gene signature, we initially performed univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis on the genes of the E2F family using expression data from the TCGA training set. Genes with an adjusted p value <0.05 were considered significant and retained for subsequent stepwise multivariate Cox analysis. Finally, the prognostic-related gene signature was built and the risk score derived from the gene signature was calculated as the sum of the expression level of each E2F gene multiplied by the corresponding regression coefficients obtained from the multivariate Cox analysis. The median risk score of the training cohort was chosen as the cutoff to stratify the patients into high- or low-risk groups for the TCGA patients with HCC. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses and the log-rank test were utilized to examine the predictive performance for this signature, with p value <0.05 considered as statistically significant.

External validation of the prognostic signature and construction of the quantitative nomogram

The GSE14520 dataset contained 247 tumor samples, 222 HCC samples processed with platform GPL3921, and complete clinical information were retrieved from the GEO database; another 25 tumor samples profiled in platform GPL571 within the same data series were not included in the analysis. The risk score for each patient in the GSE14520 validation dataset was calculated based on the prognostic signature and stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk score derived from the TCGA training cohort. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was carried out to assess the predictive ability; log-rank test with p value less than 0.05 was used to evaluate the statistical significance.

To individualize the predicted results on the 0.5-, 1-, and 1.5-year survival probability for patients with HCC and further improve the predictive accuracy of our prognostic signature, we established a nomogram as a quantitative tool based on the risk score derived from the prognostic signature combined with common clinical characteristics. A Kaplan Meier survival analysis was performed and the C-index was taken as a measure of discrimination calculated to evaluate the capacity for the nomogram. Calibration plots were used to compare and display the agreement between the predicted results and observed outcomes with regard to the 0.5-, 1-, and 1.5-year OS for the patients with HCC from the TCGA cohort.

To examine and overcome the effects of covariates such as age and gender in the discrimination power of the nomogram model, the adjusted C-index, adjusted D-index, and unadjusted D-index were calculated based on the method proposed by White et al. (20) for the nomogram. Bootstrap analysis for the C-index was utilized to mitigate the overfitting issue.

Estimation of the tumor-infiltrating immune cells in bulk-sequencing data

CIBERSORT is a computational approach developed based on linear support vector regression to predict and characterize infiltrating immune cell distributions from gene expression profiles (62). To demonstrate the differences in the proportions of diverse tumor-infiltrating immune cells between the high- and low-risk samples, we applied the CIBERSORT algorithm and LM22 signature matrix consisting of 547 genes to derive the immune infiltration status for 22 mature human hematopoietic populations in the patients with HCC. The permutation test of 1000 iterations was adopted to obtain the result of statistical significance followed by quantile normalization. Pearson correlation analysis was used for evaluating the interactions between the 22 different subsets of immune cells.

Description of the single-cell RNA sequencing data

The single-cell transcriptome data of human infiltrating T cells in a gene expression matrix format were downloaded from the GEO database with the accession number GSE98638. T cells within this dataset were collected from peripheral blood, tumor tissues, and adjacent normal liver tissues and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform. A total of 11 main clusters were described. C01_CD8 cluster: naive CD8+ T cells; C02_CD8 cluster: effector CD8+ T cells; C03_CD8 cluster: mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT); C04_CD8 cluster: exhausted CD8+ T cells; C05_CD8 cluster: intermediate state CD8+ T cells between effector and exhausted CD8+ T cells; C06_CD4: naive CD4+ T cells; C07_CD4: peripheral T regulatory cells (Tregs); C08_CD4: tumor Tregs; C09_CD4: mixed state cells; C10_CD4: exhausted CD4+ T cells; C11_CD4: cytotoxic CD4+ T cells.

Definition of class I and class II subpopulations

The coefficients from the previously constructed prognostic gene signature were applied on the centered single-cell expression data to categorize the single cells. Unlike in bulk sequencing data, we did not consider the survival time and status of specific patients, instead we treated each single cell as a separate predicted instance. The median score of all single cells derived from the gene signature was used as the cutoff value. The cells with predicted scores above the cutoff were categorized as the class I cells while the rest were classified as class II cells.

Pseudotime trajectory inference and branch-dependent gene expression analysis

The pseudotime developmental cell trajectory for the single-cell data was inferred by the Monocle 2 method (23). From the pseudotime analysis, MAIT cells were excluded owing to the distinct characteristics of the T-cell receptor (5). The DifferentialGeneTest function was used to identify the differentially expressed genes along pseudotime, and only genes with an adjusted p value <0.01 were retained to build the trajectory path. The identification of the cell fate decision points and branch-dependent gene expression analysis were carried out using the BEAM function implemented in Monocle 2.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data can be found here: TCGA https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga and GEO https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/repositories (GSE76427, GSE136247, GSE107170, GSE102079, and GSE14520 for bulk-seq data; GSE98638 for single-cell sequencing data).

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870397); Beijing Nova Program (Z211100002121039); Clinical Medicine Plus X - Young Scholars Project, Peking University; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (PKU2022LCXQ043); Research start-up funding, Peking University Third Hospital (BYSYYZD2021001).

Author contributions

X. L., Z. S., F. M., and L. W. conceptualization; X. L., Z. S., F. M., and L. W. methodology; L. W. and Y. C. formal analysis; L. W., F. M., X. L., and Y. C. writing – original draft; Y. C., R. C., L. W., X. L., and Z. S. writing – review & editing; F. M., X. L., and Z. S. supervision.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Eric Fearon

Contributor Information

Fengbiao Mao, Email: fengbiaomao@bjmu.edu.cn.

Zhongsheng Sun, Email: sunzs@biols.ac.cn.

Xiangdong Liu, Email: xiangdongliu@seu.edu.cn.

Supporting information

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu. European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganne-Carrie N., Nahon P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of alcohol-related liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finn R.S., Ryoo B.Y., Merle P., Kudo M., Bouattour M., Lim H.Y., et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangro B., Gomez-Martin C., de la Mata M., Inarrairaegui M., Garralda E., Barrera P., et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 2013;59:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng C., Zheng L., Yoo J.K., Guo H., Zhang Y., Guo X., et al. Landscape of infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell. 2017;169:1342–1356.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma L., Wang L., Khatib S.A., Chang C.W., Heinrich S., Dominguez D.A., et al. Single-cell atlas of tumor cell evolution in response to therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2021;75:1397–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q., He Y., Luo N., Patel S.J., Han Y., Gao R., et al. Landscape and dynamics of single immune cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2019;179:829–845.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malato Y., Naqvi S., Schurmann N., Ng R., Wang B., Zape J., et al. Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4850–4860. doi: 10.1172/JCI59261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan M., Ghozlan H., Abdel-Kader O. Activation of RB/E2F signaling pathway is required for the modulation of hepatitis C virus core protein-induced cell growth in liver and non-liver cells. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1375–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayhew C.N., Carter S.L., Fox S.R., Sexton C.R., Reed C.A., Srinivasan S.V., et al. RB loss abrogates cell cycle control and genome integrity to promote liver tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:976–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent L.N., Leone G. The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:326–338. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H.Z., Tsai S.Y., Leone G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:785–797. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attwooll C., Lazzerini Denchi E., Helin K. The E2F family: specific functions and overlapping interests. EMBO J. 2004;23:4709–4716. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowland B.D., Bernards R. Re-evaluating cell-cycle regulation by E2Fs. Cell. 2006;127:871–874. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernando E., Nahle Z., Juan G., Diaz-Rodriguez E., Alaminos M., Hemann M., et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lan W., Bian B., Xia Y., Dou S., Gayet O., Bigonnet M., et al. E2F signature is predictive for the pancreatic adenocarcinoma clinical outcome and sensitivity to E2F inhibitors, but not for the response to cytotoxic-based treatments. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8330. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26613-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kent L.N., Rakijas J.B., Pandit S.K., Westendorp B., Chen H.Z., Huntington J.T., et al. E2f8 mediates tumor suppression in postnatal liver development. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:2955–2969. doi: 10.1172/JCI85506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent L.N., Bae S., Tsai S.Y., Tang X., Srivastava A., Koivisto C., et al. Dosage-dependent copy number gains in E2f1 and E2f3 drive hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:830–842. doi: 10.1172/JCI87583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhan L., Huang C., Meng X.M., Song Y., Wu X.Q., Miu C.G., et al. Promising roles of mammalian E2Fs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White I.R., Rapsomaniki E., Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Covariate-adjusted measures of discrimination for survival data. Biom. J. 2015;57:592–613. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201400061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingram J.T., Yi J.S., Zajac A.J. Exhausted CD8 T cells downregulate the IL-18 receptor and become unresponsive to inflammatory cytokines and bacterial co-infections. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura H., Tsutsi H., Komatsu T., Yutsudo M., Hakura A., Tanimoto T., et al. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu X., Mao Q., Tang Y., Wang L., Chawla R., Pliner H.A., et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:979–982. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Leun A.M., Thommen D.S., Schumacher T.N. CD8(+) T cell states in human cancer: insights from single-cell analysis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2020;20:218–232. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahuron K.M., Moreau J.M., Glasgow J.E., Boda D.P., Pauli M.L., Gouirand V., et al. Layilin augments integrin activation to promote antitumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217 doi: 10.1084/jem.20192080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vos J.M., Tsakmaklis N., Patterson C.J., Meid K., Castillo J.J., Brodsky P., et al. CXCL13 levels are elevated in patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, and are predictive of major response to ibrutinib. Haematologica. 2017;102:e452–e455. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.172627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bono P., Rubin K., Higgins J.M., Hynes R.O. Layilin, a novel integral membrane protein, is a hyaluronan receptor. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:891–900. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powathil G.G., Gordon K.E., Hill L.A., Chaplain M.A. Modelling the effects of cell-cycle heterogeneity on the response of a solid tumour to chemotherapy: biological insights from a hybrid multiscale cellular automaton model. J. Theor. Biol. 2012;308:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otto T., Sicinski P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:93–115. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtani N., Brennan P., Gaubatz S., Sanij E., Hertzog P., Wolvetang E., et al. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 blocks p16INK4a-RB pathway by promoting nuclear export of E2F4/5. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:173–183. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wetmore C., Boyett J., Li S., Lin T., Bendel A., Gajjar A., et al. Alisertib is active as single agent in recurrent atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors in 4 children. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:882–888. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kastan M.B., Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartek J., Lukas C., Lukas J. Checking on DNA damage in S phase. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:792–804. doi: 10.1038/nrm1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutcheson J., Witkiewicz A.K., Knudsen E.S. The RB tumor suppressor at the intersection of proliferation and immunity: relevance to disease immune evasion and immunotherapy. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:3812–3819. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1010922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malumbres M., Barbacid M. Mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherr C.J., Roberts J.M. Living with or without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2699–2711. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hydbring P., Malumbres M., Sicinski P. Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:280–292. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherr C.J. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherr C.J., McCormick F. The RB and p53 pathways in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lammens T., Li J., Leone G., De Veylder L. Atypical E2Fs: new players in the E2F transcription factor family. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iaquinta P.J., Lees J.A. Life and death decisions by the E2F transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007;19:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H.Z., Ouseph M.M., Li J., Pecot T., Chokshi V., Kent L., et al. Canonical and atypical E2Fs regulate the mammalian endocycle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:1192–1202. doi: 10.1038/ncb2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y.L., Uen Y.H., Li C.F., Horng K.C., Chen L.R., Wu W.R., et al. The E2F transcription factor 1 transactives stathmin 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20:4041–4054. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delgado I., Fresnedo O., Iglesias A., Rueda Y., Syn W.K., Zubiaga A.M., et al. A role for transcription factor E2F2 in hepatocyte proliferation and timely liver regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G20–G31. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00481.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollern D.P., Honeysett J., Cardiff R.D., Andrechek E.R. The E2F transcription factors regulate tumor development and metastasis in a mouse model of metastatic breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:3229–3243. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00737-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen D., Chen Y., Forrest D., Bremner R. E2f2 induces cone photoreceptor apoptosis independent of E2f1 and E2f3. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:931–940. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong Y., Zou J., Su S., Huang H., Deng Y., Wang B., et al. MicroRNA-218 and microRNA-520a inhibit cell proliferation by downregulating E2F2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;12:1016–1022. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai S.Y., Opavsky R., Sharma N., Wu L., Naidu S., Nolan E., et al. Mouse development with a single E2F activator. Nature. 2008;454:1137–1141. doi: 10.1038/nature07066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu H., Fei D., Zong S., Fan Z. MicroRNA-154 inhibits growth and invasion of breast cancer cells through targeting E2F5. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016;8:2620–2630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fang D.Z., Wang Y.P., Liu J., Hui X.B., Wang X.D., Chen X., et al. MicroRNA-129-3p suppresses tumor growth by targeting E2F5 in glioblastoma. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;22:1044–1050. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201802_14387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li S.L., Sui Y., Sun J., Jiang T.Q., Dong G. Identification of tumor suppressive role of microRNA-132 and its target gene in tumorigenesis of prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018;41:2429–2433. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang Y., Yim S.H., Xu H.D., Jung S.H., Yang S.Y., Hu H.J., et al. A potential oncogenic role of the commonly observed E2F5 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:470–477. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zou C., Li Y., Cao Y., Zhang J., Jiang J., Sheng Y., et al. Up-regulated microRNA-181a induces carcinogenesis in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting E2F5. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim R., Emi M., Tanabe K. Cancer immunoediting from immune surveillance to immune escape. Immunology. 2007;121:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khatib S., Pomyen Y., Dang H., Wang X.W. Understanding the cause and consequence of tumor heterogeneity. Trends Cancer. 2020;6:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Y.L., Ning G., Chen L.B., Lian Y.F., Gu Y.R., Wang J.L., et al. Promising diagnostic and prognostic value of E2Fs in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019;11:1725–1740. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S182001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leek J.T., Johnson W.E., Parker H.S., Jaffe A.E., Storey J.D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:882–883. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liberzon A., Birger C., Thorvaldsdottir H., Ghandi M., Mesirov J.P., Tamayo P. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fabregat A., Jupe S., Matthews L., Sidiropoulos K., Gillespie M., Garapati P., et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D649–D655. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schaefer C.F., Anthony K., Krupa S., Buchoff J., Day M., Hannay T., et al. PID: the pathway interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D674–D679. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newman A.M., Liu C.L., Green M.R., Gentles A.J., Feng W., Xu Y., et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data can be found here: TCGA https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga and GEO https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/repositories (GSE76427, GSE136247, GSE107170, GSE102079, and GSE14520 for bulk-seq data; GSE98638 for single-cell sequencing data).