Introduction

Since its initial development, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test has undergone an evolution in use for prostate cancer (PCa) screening. Shortly after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of the PSA test to monitor patients already diagnosed with PCa in in 1986, incident rates of prostate cancer increased dramatically, as PSA was used for prostate cancer detection, even though it had not been tested rigorously for performance as a screening tool.1–3 In 1991, Catalona et al. demonstrated that PSA testing, using an arbitrary cut-off of 4.0 ng/ml, increased PCa detection and outperformed digital rectal exam and transrectal ultrasound, thus heralding the era of PSA screening.4 Ultimately, the FDA approved the use of the PSA test to screen asymptomatic individuals for prostate cancer in 1994, and yearly PSA screening was accepted as standard, despite a lack of studies on the optimal screening interval.1,3

Around the time PSA screening was becoming established in the U.S., the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial was initiated to test definitively whether yearly PSA testing met the standard endpoint of decreasing PCa mortality, as had been demonstrated for mammography and colonoscopy. PLCO failed to demonstrate a PCa mortality benefit; however, this was likely due to high levels of contamination of the control group such that essentially equal numbers of men in the intervention and control groups received PSA testing over the study period, albeit with lower frequency in the control arm.5 While the trial failed due to this confounding, it did provide evidence that less frequent PSAs, called opportunistic testing, was not inferior to yearly testing. This finding was validated in the European Randomized study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), in which screening intervals of 2–4 years between PSA tests demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in prostate cancer mortality for the intervention arm at 9, 11, and 13 years.6–8 Based on these findings and population-based modeling, the American Urological Association (AUA) and the US Preventive Services Task Force recommend PSA testing for prostate cancer detection for men aged 55–69 with screening intervals of once every two years and shared decision making.9,10

Despite these guidelines, there are some men who undergo PSA testing more often than annually, often driven by a concern for prostate cancer by the patient or their physician. We term this desire for frequent PSA testing as “Prosteria”, a portmanteau of prostate and hysteria. There is a paucity of data on the characteristics and outcomes of these men who undergo more frequent than annual PSA testing, as most studies investigating PSA screening are based on annual or less frequent testing intervals. Therefore, this study investigated national trends and outcomes in more frequent than guideline-recommended PSA screening through a large, claims-based database of male patients in the US.

Methods

Setting, Data Source, and Study Approval

This large, retrospective cohort study leveraged the Optum De-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart, a de-identified database derived from a large, adjudicated claims data warehouse with data on both private and Medicare patients.11 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. This study was approved by the university’s institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent.

Study Population and Cohort Inclusion Criteria

All adult men ≥ 30 years of age with ≥ 2 years of continuous insurance enrollment after their first PSA test in the dataset prior to censoring were included in this study. Claims data were available from January 2003 to June 2019. Men were censored at any of (1) the end of their insurance enrollment or the Optum data; (2) following their first recorded diagnosis of prostate cancer (PCa), prostatitis, or UTI; or (3) following the first claim for PCa treatment (ICD and CPT codes used for cohort definition are included in Supplementary Table 1). To limit the effect of multiple billings, such as separate billings for free and total PSA, and effects from reasonable repeat testing from unexpected results (i.e. confirmatory tests), all claims for PSA tests within a 90-day period were counted as one PSA test. PSAs prior to censoring were considered to be for screening purposes.

High Frequency PSA (Prosteria) Definition and Outcomes

Men with ≥ 3 between PSA testing intervals of 90–270 days prior to censoring were labeled as having prosteria or undergoing “High frequency PSA” testing (HF-PSA). Outcomes associated with prosteria including prostate biopsy, diagnosis, and PCa treatment (prostatectomy, radiotherapy with or without hormone therapy, and any treatment) were assessed.

PSA Level Sub-analysis

A sub-analysis was performed for patients with PSA test values available. PSA levels, including average value and value closest to PCa diagnosis were analyzed for their association with PSA testing frequency to investigate any effect of PSA level influencing testing frequency.

Costs of Prosteria

Costs of prosteria were estimated using the assumptions of equal likelihood for having PCa and disease being localized for men with and without prosteria. Excess treatments were estimated using the following formula: , where and are the number of treatments among men with and without prosteria, respectively, and and were the number of men with and without prosteria, respectively. Costs of treatment were based on previously reported data by Sharma et al.12

Statistical analyses

Patient clinical characteristics were compared using univariable odds ratios. Multivariable logistic regression evaluated associations between both demographic features with PSA testing frequency. Continuous variables were evaluated using Mann Whitney U tests, while categorical variables were evaluated using Chi squared tests. Survival analyses between outcomes and PSA testing frequency were performed using log-rank testing on Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox’s proportional hazards models, using age as a covariate. All analyses were performed using Python 3.6 with the scipy, statsmodels, and sklearn packages. Results are presented as mean (standard deviation), count (percent), or odds ratio [95% Confidence Interval (CI)], unless otherwise noted.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Of the 7,581,051 men in the database with at least one claim for a PSA test for any reason, 2,958,923 men (39%) met inclusion criteria for this study (Supplementary Figure 1). There were 9,734,077 screening PSA tests on these men prior to censoring due to an exclusion diagnosis, treatment, or end of enrollment or the study period. The average age of the cohort for all tests was 61.0 (11.02), with a median age at first and last PSA of 57 and 61, respectively. The age for PSA tests in the cohort ranged from 30–90 years of age. 69.8% of the cohort was White (Table 1). A majority (54%) of patients reported making <$75,000 per year and had commercial insurance (68%) vs Medicare (32%). Most patients (74.2%) reported having attained an educational level of at least a high-school diploma.

Table 1:

Cohort Overview

| Category | Variable | Full Cohort (n=2,958,923) | Non-Prosteria (n=2,823,928) | Prosteria (n=134,995) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Birth Year | 1951.78 (11.3) | 1951.96 (11.27) | 1947.92 (11.24) | <0.0001 | |

| Age at First PSA | 58.24 (11.47) | 58.06 (11.44) | 62.06 (11.33) | <0.0001 | |

|

|

|||||

| Age | Age <55 at First PSA | 1315226 (44.4%) | 1275604 (45.2%) | 39622 (29.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Age 55–69 at First PSA | 1168451 (39.5%) | 1106867 (39.2%) | 61584 (45.6%) | ||

| Age >70 at First PSA | 475246 (16.1%) | 441457 (15.6%) | 33789 (25.0%) | ||

|

| |||||

| PSA Testing | PSA Tests (N) | 3.29 (2.26) | 3.07 (1.96) | 7.95 (3.0) | <0.0001 |

| Median PSA Interval (Days) | 547.58 (356.25) | 566.98 (357.57) | 230.31 (68.97) | <0.0001 | |

| Mean PSA Interval (Days) | 565.96 (353.59) | 584.15 (355.66) | 268.57 (84.77) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | Asian | 111163 (3.8%) | 104697 (3.7%) | 6466 (4.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 243746 (8.2%) | 232565 (8.2%) | 11181 (8.3%) | ||

| Hispanic | 273999 (9.3%) | 258480 (9.2%) | 15519 (11.5%) | ||

| White | 2065924 (69.8%) | 1975300 (70.0%) | 90624 (67.1%) | ||

| Unknown | 264091 (8.9%) | 252886 (9.0%) | 11205 (8.3%) | ||

|

| |||||

| College or Higher Degree | 2052970 (69.4%) | 1957550 (69.3%) | 95420 (70.7%) | <0.0001 | |

| High School or No Degree | 717635 (24.2%) | 685775 (24.3%) | 31860 (23.6%) | ||

| Unknown Education | 188318 (6.4%) | 180603 (6.4%) | 7715 (5.7%) | ||

|

|

|||||

| Socioeconomic Status | Top Income | 1360349 (46.0%) | 1295219 (45.9%) | 65130 (48.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Bottom Income | 529341 (17.9%) | 503863 (17.8%) | 25478 (18.9%) | ||

| Middle Income | 437020 (14.8%) | 414967 (14.7%) | 22053 (16.3%) | ||

| Unknown Income | 632213 (21.4%) | 609879 (21.6%) | 22334 (16.5%) | ||

|

|

|||||

| Commercial (Supplemental) Insurance | 2026063 (68.5%) | 1952745 (69.2%) | 73318 (54.3%) | <0.0001 | |

| Medicare Insurance | 932860 (31.5%) | 871183 (30.8%) | 61677 (45.7%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Region | Northeast | 274356 (9.3%) | 257907 (9.1%) | 16449 (12.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Midwest | 737454 (24.9%) | 715000 (25.3%) | 22454 (16.6%) | ||

| South | 757739 (25.6%) | 716570 (25.4%) | 41169 (30.5%) | ||

| West | 1189374 (40.2%) | 1134451 (40.2) | 54923 (40.7%) | ||

PSA Testing Statistics and Prosteria

On average, each man had 3.3 (2.26) screening PSA tests, with a 95th percentile of 8 PSA tests. Approximately 1 in 5 men had only 1 PSA test during observation. Of those with more than one test, the median time between PSA tests per individual was around 1.5 years (547 days), representing a plurality opting for an annual-or-less frequent screening rate (Supplementary Figure 2a). The distribution of time between PSA tests was notable for spikes at 180, 365, and 730 days, representing follow-up twice annual, annual, and biannual screening, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2b). Using the aforementioned definition for prosteria, 134,995 men (4.5%) had prosteria. These men had greater numbers of PSA tests with decreased time between them (Supplementary Figure 3a-b). The age distribution of men with prosteria was similar to the normal screening group; however, older age at first PSA was associated with shorter time between PSA tests (Supplementary Figure 3c-d).

Demographic Characteristics of Prosteria

Multivariable logistic regression revealed significant associations between race and prosteria, with White men having lower odds for having prosteria relative to Asian, Black, Hispanic/Latino men (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figure 4b). In addition, higher educational attainment (i.e. college graduation) was associated with increased rates of prosteria (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: [1.08–1.11], p < 0.0001). Concordantly, higher- and middle-income patients were more likely to undergo HF-PSA testing than lower-income patients. Both older and younger men had higher rates of prosteria (Supplementary Figure 3f). Conversely, relative to patients on commercial insurance, Medicare patients were more likely to have prosteria (OR 1.33, 95% CI: [1.32–1.35], p < 0.0001). In terms of geographic distribution, patients with HF-PSA were more likely to be in the Northeast, South, and West compared to the Midwest (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figure 4d).

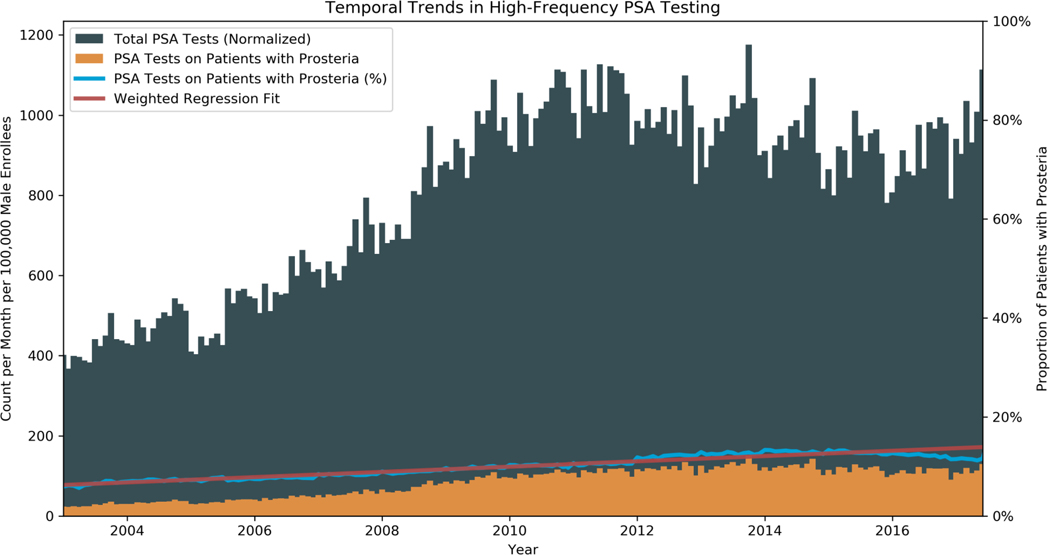

Temporal Trends

The number of PSA tests per month generally increased over the study period, from 40 per 10,000 male enrollees in January 2003 to 52 per 10,000 male enrollees in June 2019 (Figure 1). The number of PSA tests per month exhibited contemporaneous trends with changes in the USPTF guidelines, with a slowing in the rate of rise in PSA testing around 2012. Despite the plateau in testing following 2012, the proportion of men undergoing HF-PSA testing continued to increase, irrespective of the USPTF guidelines. Fitting a linear model weighted by the number of PSA tests per month, prosteria prevalence increased at a rate of 0.53% per year from 5.9% in January 2003 to 13.2% in June 2019.

Figure 1: Temporal Trends in Prosteria.

Distribution of PSA over the study period. 2003–2017 are displayed as there was a subsequent drop in cohort size due to patients needing 2 years of continuous enrollment with data terminating in 2019. Gray: Total PSA tests, normalized by 100,000 male enrollees at that time. Orange: Normalized number of PSA tests on patients with prosteria. Blue: Percent of PSAs on patients with prosteria. Red: Trend line for proportion of PSAs on patients with prosteria, weighted by number of PSA tests per month.

Patient Outcomes

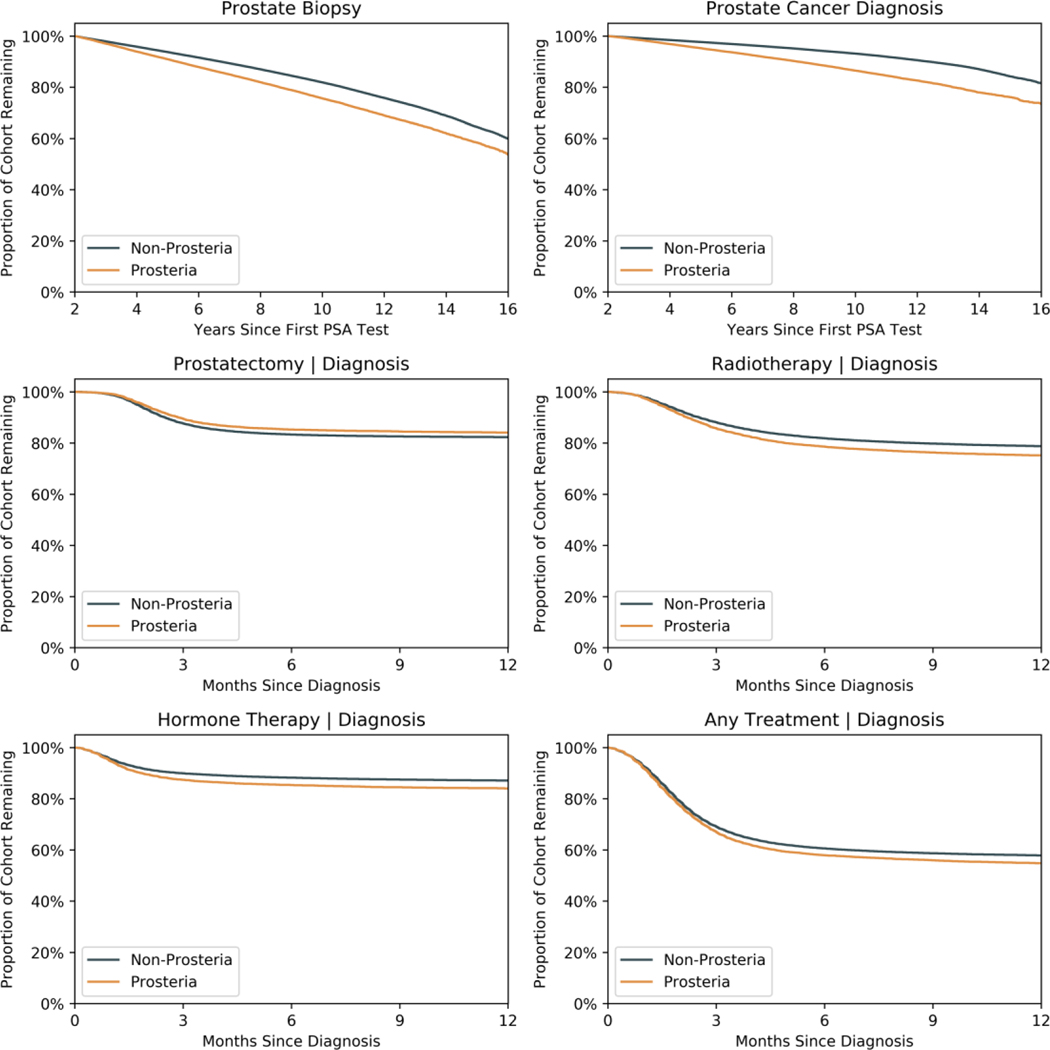

There were 210,157 men who had prostate biopsies, resulting in 82,056 incident diagnoses of PCa (2.8% of the cohort) during the study period. Men with prosteria were significantly more likely to undergo at least one prostate biopsy (OR: 2.20, 95% CI: [2.16–2.22], p < 0.0001) and subsequently be diagnosed with PCa (7.4% vs 2.6%, OR: 2.05, 95% CI: [1.99–2.12], p < 0.0001) (Table 2). Log-rank testing on Kaplan-Meier survival curves were significant for differences in the biopsy and diagnosis rate from the start of screening between the groups (Figure 2a-b). Additionally, men with prosteria underwent more prostate biopsies, with 16.5 biopsies per 100 men with prosteria vs 8 biopsies per 100 men without prosteria (p < 0.0001). Assuming a biopsy was negative if there were no subsequent PCa diagnosis, negative biopsy rates were 69% for men with prosteria and 80% for men without (p < 0.0001).

Table 2:

Patient Outcomes

| Variable | Full Cohort (n=2,958,923) | Non-Prosteria (n=2,823,928) | Prosteria (n=134,995) | OR / HR [95% CI] | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy* | 210157 (7.1%) | 191539 (6.8%) | 18618 (13.8%) | 2.20 [2.16–2.22] | < 0.0001 |

| Biopsy (N, Mean)* | 251746 (0.085) | 233796 (0.081) | 23635 (0.165) | - | < 0.0001 |

| Diagnosis* | 82056 (2.8%) | 72102 (2.6%) | 9954 (7.4%) | 2.05 [1.99–2.12] | <0.0001 |

| Surgery** | 15724 (19.2%) | 13976 (19.4%) | 1748 (17.6%) | 0.89 [0.84–0.93] | <0.0001 |

| Radiotherapy** | 21683 (26.4%) | 18768 (26.0%) | 2915 (29.3%) | 0.98 [0.94–1.02] | 0.32 |

| Hormone Therapy** | 13168 (16.0%) | 11237 (15.6%) | 1931 (19.4%) | 0.97 [0.92–1.02] | 0.30 |

| Any Treatment** | 36228 (44.2%) | 31601 (43.8%) | 4627 (46.5%) | 0.94 [0.91–0.97] | <0.0001 |

OR, Odds Ratio

HR, Hazards Ratio (Within 1 year of Diagnosis)

Figure 2: Survival Analyses.

Panel A and B: Kaplan-Meier survival curves for prostate biopsy and PCa diagnosis since first PSA test, stratified by prosteria.

Panel D-F: Survival curves for prostatectomy, radiation, hormone therapy, and any treatment from time of PCa diagnosis, stratified by prosteria.

Of the men with prostate cancer, 50% elected to undergo treatment within two years of diagnosis. Men with prosteria had slightly higher odds for undergoing treatment (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: [1.07–1.16], p < 0.0001) (Table 2). However, men with prosteria were not significantly faster to pursue various treatments within the two years of diagnosis. Log-rank testing on Kaplan-Meier curves showed only a significant difference for prostatectomy between the two groups, with decreased rates among prosteria patients, and no difference in rates of radiation and/or hormone therapy within the first year. Concordantly, hazard ratios for surgery (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: [0.84–0.93], p < 0.0001), radiotherapy (HR: 0.98, 95% CI: [0.94–1.02], p = 0.32), hormone therapy (HR: 0.97, 95% CI: [0.92–1.02], p = 0.30), and any treatment (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: [0.91–0.97], p < 0.001) showed generally comparable rates to therapy within the first year of diagnosis for men with prosteria (Figure 2c-f). Repeating analyses on patients grouped by median inter-PSA interval instead of the prosteria definition showed similar results (Supplementary Figure 5).

PSA level and Patient Follow-up Sub-analysis

The data set also included 3,017,336 PSA tests linked to laboratory values (31% of PSA tests included) on 1,287,861 men. Men who underwent HF-PSA testing had slightly higher average PSA values with a cohort-wide average PSA of 2.51 ng/ml vs 1.41 ng/ml for those undergoing guideline frequency screening (p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Figure 6a). 96% non-prosteria group and 80% of the prosteria group never had a recorded PSA >4 ng/ml prior to censoring. Despite this, men with prosteria had lower PSA values closest to the time of diagnosis: 6.79 ng/ml vs 7.32 ng/ml (p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Figure 6b).

Costs of Prosteria

Estimates for excess costs of prosteria were calculated. Using the crude assumption of equal risk for prostate cancer between men with and without prosteria, there were an excess of approximately 7.0 biopsies, 4.8 diagnoses, 0.9 prostatectomies, and 1.5 radiotherapy treatments per 100 men with prosteria. If all men not pursuing local treatment opted for active surveillance (AS), this would add an additional 2.4 AS cases per 100 men with prosteria. Further assuming that all diagnoses were localized disease, using previously reported data, this would incur excess 10-year costs of $19,026 for prostatectomies, $48,502 for radiotherapy, and $48,741 for AS, totaling $116,450 per 100 men with prosteria.12 Prosteria was present in 4.5% of the men in the cohort, representing $5,240 in excess costs to the US healthcare system per 100 men who pursue at least one PSA test. Expanding this to the approximately 40% of the US male population aged 55–69 would cost the US healthcare system over $70M annually.13,14

Discussion

In the present claims-based, multi-million-man retrospective cohort study, we examined national trends in and outcomes from more frequent than guideline recommend PSA screening. We find that prosteria is prevalent at a non-negligible level, with about 1 in 20 men in the cohort undergoing HF-PSA testing. Additionally, this phenomenon has been increasing over time in the US at a rate of 0.53% per year, independent of USPSTF recommendations. Furthermore, we identified factors associated with prosteria, including demographic and provider characteristics. Specifically, men were more likely to go HF-PSA testing if they were non-White, less educated, and older, while ordering providers were more likely to be from the South and least likely to be from the Midwest.

Since initial adoption for PCa screening, the PSA test has been controversial, as underscored by shifting USPTF recommendations. Despite this, given the overall high incidence of prostate cancer diagnosis and mortality, many men elect to undergo PSA-based PCa screening, with some testing more frequently than recommended by USPTF and AUA. Prior to this study, the prevalence of prosteria, as well as its downstream ramifications on diagnosis and treatment, were poorly characterized, which could make appropriately counseling these men challenging. To this end, our study is an important first step in quantifying the prevalence of prosteria, as well as the populations that are disproportionately involved and their ultimate outcomes.

Our finding that prosteria is more common among non-White patients may be initially surprising in the context of prior literature that demonstrates White patients are more likely to undergo annual PSA screening than non-White patients.15–17 However, the key difference is that the endpoint of these prior reports is the performance of yearly screening, whereas the endpoint of the present report was HF-PSA testing. A variety of factors may underlie why HF-PSA testing is more common in non-White patients. Age-adjusted prostate cancer-specific mortality rates are higher in Black men than in White men, and some authors have accordingly recommended screening guidelines tailored specifically for Black men.17,18 This ongoing dialogue may have inspired some physicians to recommend or patients to request more than annual PSA tests for Black men. Furthermore, anxiety surrounding PSA screening and prostate cancer has been suggested to disproportionately affect racial minorities, which could lead to requests for more than annual PSA tests from non-White men to their providers.19–21

Importantly, consistent with prior evidence that PSA testing results in increased PCa diagnoses, men with prosteria were significantly more likely to undergo prostate biopsy and be diagnosed with PCa. Despite this, men in this study had clinically similar PSA test values, regardless of PSA testing frequency, with most men in the study never having PSA values >4 ng/dL, regardless of testing frequency. This implies that the motivation for HF PSA testing is not exclusively driven by PSA results. In addition, of men diagnosed with PCa, prosteria itself was not associated with faster treatment. Taken together, these results strongly suggest over diagnosis, likely of clinically insignificant or low-grade PCa in this population. These men may be subjected to increased rates of active surveillance or treatment leading to increased risks for overtreatment/side effects and may experience adverse mental health effects of living with a cancer diagnosis.6,22 Moreover, additional prostate cancer diagnoses (whether undergoing surveillance or treatment) likely lead to tens of millions of dollars in excess spending, without considering the costs of additional PSA tests and prostate biopsies on these men. Overall, the current results do not support PSA screening at an interval < 1 year, consistent with current AUA guidelines of PSA testing at approximately 2-year intervals.

Further work is needed to validate the present study’s findings, paying attention to disease characteristics, such as Gleason score, which were not available in the data set. Other work could investigate overuse of confirmatory testing, such as MRI and biomarker testing, in men with prosteria. Additionally, researchers could examine mental health comorbidities and family histories of PCa in men with prosteria to better understand patient and provider motivations. Clinically, providers can integrate these findings in their discussions when counseling patients who are seeking more frequent than guideline recommended PSA screening. Additionally, as treatment rates within one year were comparable between men with and without prosteria, prosteria represents a prime target for quality improvement efforts to reduce PCa overdiagnosis and related costs.

Limitations

As with any retrospective, claims-based analysis, this study has certain limitations. First, there is the potential for missing or inaccurate PSA tests, diagnoses, and treatments, as well as limited granular data on individual men. However, given the large size of the cohort in this study, the impact of missing or inaccurate values in the claims data is likely mitigated, and the overall trends identified likely still hold. As mentioned, not all PSA test values were available and important testing information, such as biopsy type (e.g. MRI fusion, number of cores sampled), and disease-specific data, such as Gleason score and clinical stage, were not available in these data. In addition, the lack of detailed clinical data likely leads to an underestimation of prosteria, since we fail to capture men with slightly elevated but stable PSA levels, such as those who have had previous negative biopsies or MRI studies, who were excluded. Additionally, this study was not designed to explicitly study the costs of prosteria, and many broad assumptions were made to arrive at cost estimates. Despite these limitations, this study addresses a prevalent phenomenon that has been previously underreported and understudied.

Conclusion

This study, which is to our knowledge the first to investigate PSA screening at more frequent than guideline recommended intervals, which we term prosteria, found this phenomenon to be relatively common in the US. Prosteria more common among wealthy, educated, and non-White patients. Patients with prosteria were more likely to undergo prostate biopsy and subsequent diagnosis, but experienced similar rates in treatment after diagnosis, suggesting overdiagnosis and overtreatment. PSA testing more frequently than guideline recommended intervals likely generates unnecessary mental and physical health consequences and costs to the US healthcare system. Together, these results support the current PSA screening guidelines and can be used to counsel patients seeking PSA testing more often than is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Data for this project were accessed using the Stanford Center for Population Health Sciences Data Core. The PHS Data Core is supported by a National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Science Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 TR001085) and from Internal Stanford funding. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None

References

- 1.Charatan FB FDA approves test for prostatic cancer. BMJ 309, 628–629 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch HG & Albertsen PC Reconsidering Prostate Cancer Mortality — The Future of PSA Screening. N Engl J Med 382, 1557–1563 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catalona WJ Prostate Cancer Screening. Med Clin North Am 102, 199–214 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalona WJ et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 324, 1156–1161 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoag JE, Mittal S. & Hu JC Reevaluating PSA Testing Rates in the PLCO Trial. N Engl J Med 374, 1795–1796 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schröder FH et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med 360, 1320–1328 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schröder F. et al. Prostate Cancer Mortality at 11 years of Follow-up in the ERSPC. N Engl J Med 366, 981–990 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schröder FH et al. The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer – Prostate Cancer Mortality at 13 Years of Follow-up. Lancet 384, 2027–2035 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prostate Cancer: Early Detection Guideline - American Urological Association. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Preventive Services Task Force et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 319, 1901 (2018).29801017 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanford Center for Population Health Sciences (2021). Optum SES (v5.0). Redivis. (Dataset) 10.57761/phra-vp46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma V. et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Active Surveillance, Radical Prostatectomy and External Beam Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: An Analysis of the ProtecT Trial. Journal of Urology 202, 964–972 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HEALTH, NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE. Prostate Cancer Screening | Cancer Trends Progress Report. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/prostate_cancer#field_data_source. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Census Bureau. Age and Sex Composition in the United States: 2018. Census.gov https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/age-and-sex/2018-age-sex-composition.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter WR et al. Racial differences in PSA screening interval and stage at diagnosis. Cancer Causes Control 21, 1071–1080 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosain GMM, Sanderson M, Du XL, Chan W. & Strom SS Racial/ethnic differences in predictors of PSA screening in a tri-ethnic population. Cent Eur J Public Health 19, 30–34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kensler KH et al. Racial and Ethnic Variation in PSA Testing and Prostate Cancer Incidence Following the 2012 USPSTF Recommendation. J Natl Cancer Inst 113, 719–726 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etzioni R. & Nyame YA Prostate Cancer Screening Guidelines for Black Men: Spotlight on an Empty Stage. J Natl Cancer Inst 113, 650–651 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupski TL et al. Ethnic variation in health-related quality of life among low-income men with prostate cancer. Ethn Dis 15, 461–468 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson CJ et al. Assessing anxiety in Black men with prostate cancer: further data on the reliability and validity of the Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer (MAX-PC). Support Care Cancer 24, 2905–2911 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivers BM et al. Understanding the psychosocial issues of African American couples surviving prostate cancer. J Cancer Educ 27, 546–558 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korfage IJ, de Koning HJ, Roobol M, Schröder FH & Essink-Bot M-L Prostate cancer diagnosis: the impact on patients’ mental health. Eur J Cancer 42, 165–170 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.